Abstract

Mindfulness meditation programs, which train individuals to monitor their present moment experience in an open or accepting way, have been shown to reduce mind-wandering on standardized tasks in several studies. Here we test two competing accounts for how mindfulness training reduces mind-wandering, evaluating whether the attention monitoring component of mindfulness training alone reduces mind-wandering or whether the acceptance training component is necessary for reducing mind-wandering. Healthy young adults (N=147) were randomized to either a 3-day brief mindfulness training condition incorporating instruction in both attention monitoring and acceptance, a mindfulness training condition incorporating attention monitoring instruction only, a relaxation training condition, or a reading control condition. Participants completed measures of dispositional mindfulness and treatment expectancies before the training session on Day 1 and then completed a 6-minute Sustained Attention Response Task (SART) measuring mind-wandering after the training session on Day 3. Acceptance training was important for reducing mind-wandering, such that the monitoring + acceptance mindfulness training condition had the lowest mind-wandering relative to the other conditions, including significantly lower mind-wandering relative to the monitor-only mindfulness training condition. In one of the first experimental mindfulness training dismantling studies to-date, we show that training in acceptance is a critical driver of mindfulness training reductions in mind-wandering. This effect suggests that acceptance skills may facilitate emotion regulation on boring and frustrating sustained attention tasks that foster mind-wandering, such as the SART.

Keywords: mindfulness, acceptance, mind-wandering

Mindfulness meditation training has been linked to a broad range of cognitive, affective, and health outcomes (Brown, Creswell, & Ryan, 2015; Creswell & Lindsay, 2014; Sedlmeier et al., 2012). Some of the most robust findings in the cognitive domain pertain to how mindfulness meditation training can foster on-task, sustained attention and reduce mind-wandering (Jha et al., 2015; Morrison et al., 2013; Mrazek, Smallwood, & Schooler, 2012; Mrazek, Franklin, Phillips, Baird, & Schooler, 2013; Slagter et al., 2007; Tang et al., 2007). For example, Mrazek and colleagues (2012) found that a brief mindfulness meditation training decreased mind-wandering during the SART (Mrazek et al., 2012) compared to passive relaxation and reading control conditions. The SART is a commonly used sustained attention task known to be associated with mind-wandering reported in daily life and mind-wandering measured during mindful breathing tasks, including self-caught task-unrelated thought (Mrazek et al., 2012). During the SART, participants attend for an extended period of time to frequent non-targets and infrequent targets. Participants are instructed to press the spacebar when presented with all numbers excluding the number “3” and to respond to the number “3” by refraining from pressing the spacebar. In order to successfully complete the task, participants must maintain their attention to these non-targets for a prolonged period of time and must avoid mind-wandering. Failures to correctly respond or refrain from responding index greater mind-wandering.

While there are now several studies showing that brief mindfulness meditation training reduces mind-wandering during the SART (Morrison et al., 2013; Mrazek et al., 2012), the underlying mechanisms driving these effects are not yet known. It is possible that mindfulness decreases mind-wandering and facilitates sustained attention during the SART by equipping participants with the emotion regulation skills necessary to regulate frustration or boredom experienced during the task. Previous research has shown that mindfulness training improves emotion regulation (Arch & Craske, 2006), an important skill for successful performance on boring or challenging tasks that require regulation of unpleasant emotions (Philippot, Nef, Clauw, de Romree, & Segal, 2012). Indeed, the SART has been linked in multiple studies to affective outcomes, including negative affect (Mrazek et al., 2012; Smallwood et al., 2009).

Mindfulness meditation can take a variety of forms, but core to each form is an experiential, comparatively non-discursive observation of internal and/or external perceptual stimuli as they unfold in real time. For example, in the attention monitoring form of mindfulness commonly taught in mindfulness training programs, attention is concentrated upon a stimulus object (e.g., bodily sensations associated with breathing) while meta-awareness, an apprehension of the current state of the mind, serves to monitor or regulate attention in order to sustain it (Dreyfus, 2011). Some have argued that implicit to such mindful attention is an acceptance or openness to ongoing perceptual occurrences (Anālayo, 2003; Brown & Ryan, 2004). Yet many people who undertake mindfulness training can attest to the challenge of sustaining mindful attention without a regular (or even incessant) wandering of attention, and many forms of mindfulness instruction have explicitly incorporated skill training in fostering an attitude of acceptance and non-judgment in order to enable a disengagement from habitual mental discursivity and reactivity, which can disrupt sustained attention (Bishop et al., 2004). Accordingly, one interesting potential consequence is that learning how to be more accepting toward present moment experience in mindfulness interventions can foster a greater capacity to sustain attention and reduce mind-wandering.

Here we test two accounts to explain how mindfulness training may affect mind-wandering. The first account is that training in attention monitoring could be sufficient to reduce mind-wandering, as the capacity to sustain attention might foster on-task attention (Chiesa & Malinowski, 2011; Malinowski, 2012). The second account, the Monitor + Acceptance account, posits that acceptance training is a critical mechanism in mindfulness training effects on reducing mind-wandering. Specifically, attentionally demanding tasks can induce boredom, frustration and other unpleasant emotions that may interfere with task performance, while acceptance may facilitate greater emotion regulation that buffers the distracting effects of these negative emotions and facilitates on-task attention and performance (Lindsay & Creswell, 2015; Teper & Inzlicht, 2013). Indeed, several studies suggest that greater acceptance is associated with improved cognitive performance on tasks involving simultaneous attention and affect regulation, such as the Stroop task (Anicha, Ode, Moeller, & Robinson, 2012; Moore & Malinowski, 2009; Teper & Inzlicht, 2013). Furthermore, this Monitor + Acceptance account builds from previous research showing that negative emotions prospectively drive greater mind-wandering (Franklin et al., 2013; Killingsworth & Gilbert, 2010).

In this study, we dismantled mindfulness training into two primary instructional components of attention monitoring and acceptance to better understand whether attention monitoring alone drives improvements on an attention task (the SART), or whether the attitude of acceptance toward monitored experiences further enhances performance on the SART. Participants were randomly assigned to mindfulness training in attention monitoring, mindfulness training in attention monitoring and acceptance, relaxation training, or an active control condition. Attention monitoring training instructed participants to monitor the ongoing sensations of breathing and to note thoughts, emotions, and sensations that spontaneously arise in the mind and body before bringing attention back to the breath. After receiving training on attending to their breath, participants then learned to monitor their body sensations, thoughts, and emotions. The attention monitoring + acceptance mindfulness training condition incorporated these instructions as well as instructions for adopting an accepting, non-judgmental attitude toward ongoing experience. Specifically, participants were taught to monitor their experiences in a non-judgmental and accepting manner, remaining detached and non-reactive when noticing that their mind has wandered, or when observing difficult emotions or uncomfortable body sensations. After receiving three days of 20-minute trainings in each condition, participants completed the SART, performance on which served as the behavioral index of mind-wandering.

Methods

Participants

Eligible participants were those who were between the ages of 18 and 30 years, in good mental and physical health, meditation novices (no prior meditation experience), and not taking any form of oral contraceptive for purposes of controlling for factors that may impact measurement of biological stress reactivity on Day 4 (to be reported on in future papers). We enrolled 147 (74 male) participants from the Carnegie Mellon University and University of Pittsburgh campus communities and randomly assigned them to one of four conditions, using a 2:2:2:1 allocation sequence: a 4-session attention monitoring-only mindfulness training program (n=41), a 4-session attention monitoring + acceptance mindfulness training program (n=41), a 4-session relaxation training program (n=38), or 4 sessions of listening to neutral reading material in a reading control condition (n=22) (see Training Conditions). We excluded five participants from study analyses, two for reporting being outside of the required age range after enrollment in the study, one for prior meditation experience, and two for equipment failure resulting in missing SART data. Analyses were thus conducted on N=142 participants. The average age of our final sample was 21 years old (SD=3.25). The ethnic breakdown was 27% Caucasian, 31% Asian, 22% Asian American, 9% African American, 4% Latino/Hispanic, 6% Mixed, and 1% Other. All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Carnegie Mellon University and data was collected between August 2013 and July 2014.

Procedure

Participants were recruited for a study investigating attention training and performance ability. At the baseline session, participants completed a measure of dispositional mindfulness, were randomly assigned to a study condition, completed the first of four 20-minute training sessions, and then completed a measure of training expectancy (see Measures). Training sessions were delivered on consecutive days by pre-recorded audio files via computer and headphones. To ensure experimenter blinding to training condition, an independent research staff member created a pre-randomized set of labeled audio files for each participant. Experimenters monitored participants during each training session and reminded them to actively engage in the training if they appeared to be sleeping or distracted. After completing the third training session, participants completed the SART (see Measures). Finally, participants returned on the fourth consecutive day to complete a final training session, questionnaires, and the Trier Social Stress Test (TSST), and then were debriefed on the primary study aims. Participants were compensated a total of $60 for full participation in the four days of study activities. This report describes the SART results; other reports to follow will describe other results.

Training Conditions

Each training condition consisted of four 20-minute sessions audio recorded by the same female voice. In all active treatment conditions, instructions were matched for word count, length of silent periods, and training expectancies for performance on upcoming tasks. All participants were told that the attention training was designed to prepare them for upcoming tasks. Participants randomly assigned to the reading control condition received minimal training expectancies pertaining to upcoming tasks.

In the mindfulness conditions, participants were asked to maintain an upright seated posture. Participants in the relaxation condition were instructed to find a comfortable position and do whatever they needed to relax. Participants in the control condition were given no posture instruction and instead were told to let their mind and body be at ease. Mindfulness instructions in this study map onto other mindfulness trainings with similar attention monitoring, thought labeling, and body scanning practices. The scripts for all study conditions are available upon request.

The attention monitoring only training condition

The attention monitoring only training condition consisted of meditation training that included training sustained attention to breathing sensations, body sensations, thoughts and emotions, as well as a meta-awareness of cognitive, emotional, and physical events (e.g. “You can notice when your mind wanders off using the label “distracted”, and then return to monitoring your breathing”). Unspoken labeling of such events (e.g., “thinking,” “feeling”) helped to foster concentration upon the attentional object (e.g., breath sensations). No instructions designed to foster acceptance of ongoing experience were included.

The attention monitoring + acceptance training condition

The attention monitoring + acceptance training condition consisted of similar instructions to those for the attention monitoring-only training condition, plus instructions to attend to breathing sensations, other bodily sensations, emotions, and thoughts with an accepting and non-judgmental attitude toward those experiences (e.g. “Most importantly, there is no need in this practice to judge yourself negatively, because becoming distracted is just part of the practice of training your attention”).

The relaxation training condition

The guided ‘relaxation training’ condition consisted of different forms of guided relaxation imagery exercises, including walking along a beach, through a forest, and through an imagined space (e.g. “You are entering into your imagination as if entering into a pleasant, inviting world”).

The reading control condition

The reading control condition contained excerpts from neutral articles on geography, culture, and the environment (e.g. “The trigger for this ecological shift—found nowhere else—is the onset of the khareef, the southwesterly monsoon”). Participants were instructed to allow themselves to be “absorbed by the narratives” of the articles. The purpose of this control condition was to match the demands experienced in the active treatment condition 20-minute training periods, and it provided a relative baseline comparison group for assessments of mind-wandering.

Measures

Dispositional mindfulness

On Day 1, prior to completing the first training session, participants completed the 15-item Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (Brown & Ryan, 2003). The MAAS asks participants to report their attentiveness to and awareness of present moment experience using items including “I find it difficult to stay focused on what’s happening in the present”. Participants make ratings on a scale from 1 (Almost Never) to 6 (Almost Always). Individual items were reverse-scored, then averaged to create a composite dispositional mindfulness score, with higher scores reflecting higher dispositional mindfulness (Cronbach’s α=.81).

Training expectancy

Immediately after the training session on Day 1, participants were asked to indicate how much they believe, in that moment, the training they received is beneficial to them. Four items from the Credibility/Expectancy Questionnaire (Devilly & Borkovec, 2000; study alpha=.91) measured belief in the relevance and effectiveness of the training on a scale of 1 (not at all) to 9 (very much) (e.g. “at this point how much do you feel that attention training will help your cognitive performance at the end of the study?”). Responses to the four items were averaged to produce composite training expectancy scores for Day 1. Higher scores indicate greater belief in the efficacy and relevance of the training for upcoming task performance.

Sustained Attention Response Task

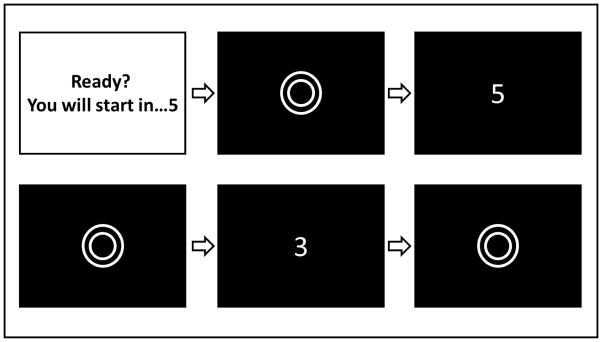

The SART is a 6-minute, computerized mind-wandering task (Mrazek et al., 2012) wherein participants are instructed to press the spacebar in response to frequent non-targets (GO trials; all numbers except the number 3) and to refrain from pressing the spacebar in response to infrequent targets (NOGO trials; the number 3). Participants were presented with 34 NOGO trials and 281 GO trials, for a total of 315 trials. Participants were provided with a limited response time of 250 milliseconds with an interstimulus interval of 900 milliseconds (see Figure 1). Participants were not provided with any feedback after the training or task trials. Mind-wandering is measured during the SART when lapses of attention occur and participants fail to respond correctly on task trials (either pressing the spacebar in response to seeing a number other than 3 on the screen, or refraining from pressing the spacebar in response to seeing the number 3 on the screen). Sustained attention discrimination rate (discrimination) was our measure of mind-wandering and is calculated as the hit rate (number of correct presses in response to frequent non-targets) minus the SART error rate (number of incorrect presses in response to infrequent targets). We report training condition differences in discrimination (overall attention calculated from hit rate minus false alarm rate) during the SART.

Figure 1.

An example of a frequent go trial followed by an infrequent NOGO trial in the Sustained Attention Response Task.

Statistical Data Analysis

All analyses were conducted with SPSS 21 software (IBM, Armonk, New York). Preliminary analyses included one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) or chi-square tests evaluating success of randomization of age, gender, ethnicity, and trait mindfulness. One-way analyses of covariance (ANCOVA), controlling for age, were implemented to test for condition differences in treatment expectancies and SART performance, gender effects on SART performance, as well as effects of the interaction between gender and condition on SART performance. Secondary analyses tested for dispositional mindfulness relationships with SART performance using linear regression, as well as multiple regression analyses testing for condition and dispositional mindfulness interactions on SART performance. In analyses that included dispositional mindfulness, mean-centered MAAS scores were used. Three dummy coded variables were created for multiple regression analyses, one for each active training condition, using the reading control condition as the reference group.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

There were no baseline condition differences in gender (χ2(3) = 1.74, p = .63), race/ethnic composition (χ2(18) = 10.30, p = .92), or dispositional MAAS mindfulness (F(3) = .74, p = .53), indicating successful randomization. There was a significant condition difference in age (F(3) = 2.69, p = .049), so age was included as a covariate in all study analyses. As expected, there was a marginally significant (bordering on statistical significance) condition difference for Day 1 treatment expectancy controlling for age (F(3) = 2.66, p = .05), such that all three active treatment conditions had higher treatment expectancies (attention monitoring only: M = 6.32, SE = .26; attention monitoring + acceptance: M = 5.75, SE = .26; relaxation: M = 5.91, SE = .28) relative to the active reading control condition (M = 5.05, SE = .36). Collapsing across study conditions, one-way ANCOVAs revealed no gender differences on the SART when controlling for age (discrimination: F(1) = .05, p = .82), and no gender by condition interactions on the SART when controlling for age (discrimination: F(3) = .62, p = .61).

Primary Analyses

Evidence from SART outcomes supports the Monitor + Acceptance account; participants in this condition showed the lowest mind-wandering relative to the other three conditions (attention monitoring only, relaxation, control). Specifically, a one-way ANCOVA (controlling for age) revealed a significant condition difference in mind-wandering as measured by discrimination, or the number of correct presses in response to frequent non-targets minus the number of incorrect presses in response to infrequent targets (F(3) = 3.41, p = .02; Table 1; Figure 2). In follow-up pairwise comparisons, there were significant differences between attention monitoring + acceptance and monitor only (Mdiff = 6.21, SE = 2.78, p = .03) as well as between attention monitoring + acceptance and reading control (Mdiff = 9.84, SE = 3.31, p = .003). The difference between attention monitoring + acceptance mindfulness training and relaxation training was in the expected direction but nonsignificant (Mdiff = 3.74, SE = 2.85, p = .19).

Table 1.

Study condition effects on discrimination during the SART task, controlling for age.

| Study Condition | Mean | Standard Error |

|---|---|---|

| Monitor and Accept | 267.264 | 1.959 |

| Monitor Only | 261.050 | 1.959 |

| Relaxation | 263.520 | 2.040 |

| Reading control | 257.425 | 2.695 |

Figure 2.

A one-way ANCOVA (controlling for age) revealed a significant condition difference in mind-wandering as measured by discrimination.

Secondary Analyses

There is some question in the literature whether baseline dispositional mindfulness (as measured by the MAAS) is associated with mind-wandering during the SART (Cheyne, Carriere, & Smilek, 2006). We found no significant association in regression analyses controlling for age relating baseline dispositional mindfulness with discrimination (β = .10, t(2) = 1.22, p = .23). It is also possible that baseline dispositional mindfulness moderated subsequent mindfulness training condition effects on discrimination (Creswell, Pacilio, Lindsay, & Brown, 2014), but no dispositional mindfulness main effect was found (β = .07, t(8) = .36, p = .72) and no significant dispositional mindfulness by training condition interactions were observed (all ps > .42) in multiple regression analyses (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Condition by dispositional mindfulness interaction effects on discrimination controlling for age.

| B | SE | Std. β | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 230.391 | 7.424 | 31.035 | .00 | |

| age | 1.234 | .337 | .299 | 3.658 | .00 |

| Mean centered MAAS | 1.532 | 4.234 | .073 | .362 | .718 |

| Monitor + Accept by MAAS | 4.158 | 5.257 | .106 | .791 | .43 |

| Monitor Only by MAAS | .181 | 5.172 | .005 | .035 | .972 |

| Relaxation by MAAS | −.108 | 5.262 | −.003 | −.02 | .984 |

Discussion

The findings of this study are consistent with existing evidence showing that mindfulness training reduces mind-wandering on the SART and also extends previous work by showing that an acceptance training component in mindfulness training is an important component for these effects. Using a randomized controlled design, we showed that brief attention monitoring + acceptance mindfulness training significantly reduced mind-wandering compared to a structurally equivalent attention monitoring only mindfulness training program. Our experimental approach provided support for the Monitor + Acceptance account that posits that the acceptance component of mindfulness training is critical for improving mind-wandering (Lindsay & Creswell, 2015), and contributes new evidence to the body of literature exploring active ingredients in mindfulness training (Anicha et al., 2012; Chiesa & Malinowski, 2011; Franklin et al., 2013; Lindsay & Creswell, 2015; Malinowski, 2012; Moore & Malinowski, 2009; Teper & Inzlicht, 2013). Evidence from this study suggests that learning how to be more accepting toward present moment experience in mindfulness interventions fosters a greater capacity to reduce mind-wandering and that the acceptance component of mindfulness may be important in mindfulness training programs geared toward improving attention outcomes.

One interesting question for future research is to investigate how acceptance training impacts sustained attention and mind-wandering outcomes. One possibility is that acceptance acts as an emotion regulatory strategy (Dan-Glauser & Gross, 2015), and improve the regulation of negative affect experienced during boring and frustrating tasks like the SART (Teper, Segal, & Inzlicht, 2013). Acceptance may also lead to the use of other emotion regulatory strategies, including decentering (Bernstein et al., 2015; Bieling et al., 2012; Hoge et al., 2015). Indeed, a number of studies show that mindfulness training is effective at improving emotion regulation and research has also shown that the SART is linked to affective outcomes, including negative affect (Mrazek et al., 2012; Smallwood et al., 2009), so we posit that acceptance may be a critical skill for these effects of mindfulness on emotion related outcomes (Lindsay & Creswell, 2015). Acceptance, the embracing of present experience without judgment or attempts to change the experience (Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda, & Lillis, 2006), has been linked to positive outcomes in previous studies of Acceptance Commitment Therapy (ACT) and Emotion Regulation Therapy (ERT), including effects on emotion outcomes (Arch et al., 2012; Bond & Bunce, 2003; Forman et al., 2007; Fresco et al., 2013). The orientation of acceptance is theorized to allow one to attend to negative affective states from a nonreactive perspective (Bieling et al., 2012), which may foster better task performance than an emotionally reactive or judgmental state; and indeed, previous findings suggest that greater negative affect is associated with greater SART errors (Mrazek et al., 2012). A capacity to accept emotional responses as natural and to allow them to arise and pass in the background (rather than getting caught up or engaged in them) while directing attention to a task, may minimize attentional lapses and enhance task performance.

We did not observe a significant effect of baseline dispositional mindfulness (or an interaction between trained mindfulness and dispositional mindfulness) on SART performance. Higher basic dispositional mindfulness has been found to enhance mindfulness training effects in some previous research (Creswell et al., 2014; Shapiro et al., 2011) but studies are still few and the boundary conditions for such moderated effects are unknown. Interestingly, one unexpected finding was that relaxation training was effective (above and beyond the attention control condition) at reducing mind-wandering, showing comparable effects to attention monitoring + acceptance mindfulness training. Results from recent studies comparing mindfulness and relaxation training interventions are mixed, with some evidence that mindfulness meditation training and relaxation training show comparable beneficial effects on inattention, distress, and positive mood states (Jain et al., 2007; Schooler et al., 2014), and other findings showing that mindfulness training may differentially improve attention and self-regulation, as well as reduce distraction and rumination in comparison to relaxation training (Droit-Volet, Fanget, & Dambrun, 2015; Jain et al., 2007; Tang et al., 2007). Our study findings, along with findings from previous studies, support the potentially important role of the relaxation response on attention-related outcomes (Droit-Volet et al., 2015; Lazar et al., 2000). The mechanisms facilitating similar effects of the attention monitoring + acceptance mindfulness training program and a relaxation training program are unknown, although embodied cognition theories suggest the possibility that inducing relaxed bodily states might affect emotional responses (Niedenthal, 2007). If both forms of training foster emotion regulation, both may promote equanimity and acceptance toward emotions that arise during the SART (Hayes-Skelton, Usmani, Lee, Roemer, & Orsillo, 2012; Hayes-Skelton, Roemer, Orsillo, & Borkovec, 2013), with consequent benefits for task performance.

There are some limitations to this study. First, we did not incorporate an acceptance only condition and are therefore not able to make inferences that acceptance without training in attention monitoring improves mind-wandering (Lindsay & Creswell, 2015). Second, we did not measure negative affect during the SART, so although we posit that attention monitoring + acceptance mindfulness training buffered negative affective responses to the SART (Creswell & Lindsay, 2014), this prediction needs to be empirically tested in future studies, for example through the inclusion of affect measures during and after the SART.

Conclusion

This study provides one of the first dismantling tests of mindfulness training components (attention and acceptance) for attention-related outcomes. Our study tested two basic mechanisms of mindfulness training and found that there are beneficial effects of acceptance training on behavioral measures of mind-wandering performance outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Pittsburgh Life Sciences Greenhouse Opportunity Fund, the Berkman Faculty Development Fund, and two grants from the National Center for Complementary & Integrative Health (NCCIH) (R21AT008493, R01AT008685).

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Anālayo . Satipaṭṭhāna: The Direct Path to Realization. Windhorse Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Anicha CL, Ode S, Moeller SK, Robinson M. Toward a Cognitive View of Trait Mindfulness: Distinct Cognitive Skills Predict Its Observing and Nonreactivity Facets. Journal of Personality. 2012;80(2):255–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2011.00722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arch JJ, Eifert GH, Davies C, Plumb C, Rose RD, Craske MG. Randomized clinical trial of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) versus acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for mixed anxiety disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80(5):750–765. doi: 10.1037/a0028310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arch JJ, Craske MG. Mechanisms of mindfulness: Emotion regulation following a focused breathing induction. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:1849–1858. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein A, Hadash Y, Lichtash Y, Tanay G, Shepherd K, Fresco DM. Decentering and Related Constructs: A Critical Review and Metacognitive Processes Model. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2015;10(5):599–617. doi: 10.1177/1745691615594577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieling PJ, Hawley LL, Bloch RT, Corcoran KM, Levitan RD, Young LT, MacQueen GM, Segal ZV. Treatment Specific Changes in Decentering Following Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy Versus Antidepressant Medication or Placebo for Prevention of Depressive Relapse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80(3):365–372. doi: 10.1037/a0027483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop SR, Lau M, Shapiro S, Carlson L, Anderson ND, Carmody J, Segal ZV, Abbey S, Speca M, Velting D, Devins G. Mindfulness: A Proposed Operational Definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2004;11(3):230–241. doi: 10.1093/clipsy/bph077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bond FW, Bunce D. The role of acceptance and job control in mental health, job satisfaction, and work performance. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2003;88(6):1057–1067. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.6.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KW, Ryan RM. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84(4):822–848. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KW, Ryan RM. Perils and promise in defining and measuring mindfulness: Observations from experience. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2004;11(3):242–248. doi: 10.1093/clipsy/bph078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KW, Creswell JD, Ryan RM. The evolution of mindfulness research. In: Brown KW, Creswell JD, Ryan RM, editors. Handbook of mindfulness: Theory, research, and practice. New York: Guilford; 2015. pp. 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Cheyne JA, Carriere JSA, Smilek D. Absent-mindedness: Lapses of conscious awareness and everyday cognitive failures. Consciousness and Cognition. 2006;15(2006):578–592. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiesa A, Malinowski P. Mindfulness-Based Approaches: Are They All the Same? Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2011;67(4):404–424. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JD, Lindsay EK. How does mindfulness training affect health? A mindfulness stress buffering account. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2014;23(6):401–407. doi: 10.1177/0963721414547415. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JD, Pacilio LE, Lindsay EK, Brown KW. Brief mindfulness meditation training alters psychological and neuroendocrine responses to social evaluative stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;44:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.02.007. doi:10.1016.j.psyneuen.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dan-Glauser ES, Gross JJ. The temporal dynamics of emotional acceptance: Experience, expression, and physiology. Biological Psychology. 2015;108:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devilly GJ, Borkovec TD. Psychometric properties of the credibility/expectancy questionnaire. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2000;31(2):73–86. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7916(00)00012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyfus G. Is mindfulness present-centered and non-judgmental? A discussion of the cognitive dimensions of mindfulness. Contemporary Buddhism. 2011;12(1):41–54. doi: 10.1080/14639947.2011.564815. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Droit-Volet S, Fanget M, Dambrun M. Mindfulness meditation and relaxation training increases time sensitivity. Consciousness and Cognition. 2015;31:86–97. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman EM, Herbert JD, Moitra E, Yeomans PD, Geller PA. A Randomized Controlled Effectiveness Trial of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and Cognitive Therapy for Anxiety and Depression. Behavior Modification. 2007;31(6):772–799. doi: 10.1177/0145445507302202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin MS, Mrazek MD, Anderson CL, Smallwood J, Kingstone A, Schooler JW. The silver lining of a mind in the clouds: interesting musings are associated with positive mood while mind-wandering. Frontiers in Psychology. 2013;4(583):1–5. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fresco DM, Mennin DS, Heimberg RG, Ritter MR. Emotion Regulation Therapy for Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2013;20(3):282–300. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Luoma JB, Bond FW, Masuda A, Lillis J. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Psychology Faculty Publications. 2006;101:1–30. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes-Skelton SA, Usmani A, Lee JK, Roemer L, Orsillo SM. A fresh look at potential mechanisms of change in applied relaxation for generalized anxiety disorder: a case series. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2012;19(3):451–462. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes-Skelton SA, Roemer L, Orsillo SM, Borkovec TD. A contemporary view of applied relaxation for generalized anxiety disorder. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2013;42(4):292–302. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2013.777106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge EA, Bui E, Goetter E, Robinaugh DJ, Ojserkis RA, Fresco DM, Simon NM. Change in Decentering Mediates Improvement in Anxiety in Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction for Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2015;39:228–235. doi: 10.1007/s10608-014-9646-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain S, Shapiro SL, Swanick S, Roesch SC, Mills PJ, Bell I, Schwartz GER. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Mindfulness Meditation Versus Relaxation Training: Effects on Distress, Positive States of Mind, Rumination, and Distraction. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2007;33(1):11–21. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3301_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha AP, Morrison AB, Dainer-Best J, Parker S, Rostrup N, Stanley EA. Minds “At Attention”: Mindfulness Training Curbs Attentional Lapses in Military Cohorts. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(2):e0116889. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killingsworth MA, Gilbert DT. A Wandering Mind Is an Unhappy Mind. Science. 2010;330(6006):932–932. doi: 10.1126/science.1192439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazar SW, Bush G, Gollub RL, Fricchione GL, Khalsa G, Benson H. Functional brain mapping of the relaxation response and meditation. NeuroReport. 2000;11(7):1581–1585. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200005150-00041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay EK, Creswell JD. Back to the Basics: How Attention Monitoring and Acceptance Stimulate Positive Growth. Psychological Inquiry. 2015;26(4):343–348. doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2015.1085265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malinowski P. Neural mechanisms of attentional control in mindfulness meditation. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2012;7(8):1–11. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore A, Malinowski P. Meditation, mindfulness and cognitive flexibility. Consciousness and Cognition. 2009;18:176–186. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison AB, Goolsarran M, Rogers SL, Jha AP. Taming a Wandering Attention: Short-Form Mindfulness Training in Student Cohorts. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2013;7(897):1662–5161. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrazek MD, Smallwood J, Schooler JW. Mindfulness and Mind-Wandering: Finding Convergence Through Opposing Constructs. Emotion. 2012 doi: 10.1037/a0026678. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrazek MD, Franklin MS, Phillips DT, Baird B, Schooler JW. Mindfulness Training Improves Working Memory Capacity and GRE Performance While Reducing Mind-wandering. Psychological Science. 2013;24(5):776–781. doi: 10.1177/0956797612459659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedenthal PM. Embodying Emotion. Science. 2007;316:1002–1005. doi: 10.1126/science.1136930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippot P, Nef F, Clauw L, de Romree M, Segal Z. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy Treating Tinnitus. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy. 2012;19:411–419. doi: 10.1002/cpp.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schooler JW, Mrazek MD, Franklin MS, Baird B, Mooneyham BW, Zedelius C, Broadway JM. The Middle Way: Finding the Balance between Mindfulness and Mind-Wandering. In: Ross BH, editor. The Psychology of Learning and Motivation. Vol. 60. Burlington: Academic Press; 2014. pp. 1–33. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sedlmeier P, Eberth J, Schwarz M, Zimmermann D, Haarig F, Jaeger S, Kunze S. The psychological effects of meditation: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2012;138(6):1139–1171. doi: 10.1037/a0028168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro SL, Brown KW, Thoresen C, Plante TG. The moderation of Mindfulness-based stress reduction effects by trait mindfulness: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Journal of clinical psychology. 2011;67(3):267–277. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slagter HA, Lutz A, Greischar LL, Francis AD, Nieuwenhuis S, Davis JM, Davidson RJ. Mental Training Affects Distribution of Limited Brain Resources. PLoS Biol. 2007;5(6):e138. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smallwood J, Fitzgerald A, Miles LK, Phillips LH. Shifting Moods, Wandering Minds: Negative Moods Lead the Mind to Wander. Emotion. 2009;9(2):271–276. doi: 10.1037/a0014855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang YY, Ma Y, Wang J, Fan Y, Feng S, Lu Q, Posner MI. Short-term meditation training improves attention and self-regulation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104(43):17152–17156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707678104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teper R, Inzlicht M. Meditation, mindfulness and executive control: the importance of emotional acceptance and brain-based performance monitoring. SCAN (2013) 2013;8:85–92. doi: 10.1093/scan/nss045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teper R, Segal ZV, Inzlicht M. Inside the Mindful Mind: How Mindfulness Enhances Emotion Regulation Through Improvements in Executive Control. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2013;22(6):449–454. doi: 10.1177/0963721413495869. [DOI] [Google Scholar]