Abstract

Background

While breast milk is considered the gold standard of infant feeding, a majority of African American mothers are not exclusively breastfeeding their newborn infants.

Purpose

The overall goal of this critical ethnographic research study was to describe infant feeding perceptions and experiences of African American mothers and their support persons.

Methods

Twenty-two participants (14 pregnant women and eight support persons) were recruited from public health programs and community based organizations in northern California. Data were collected through field observations, demographic questionnaires, and multiple in-person interviews. Thematic analysis was used to identify key themes.

Results

Half of the mothers noted an intention to exclusively breastfeed during the antepartum period. However, few mothers exclusively breastfed during the postpartum period. Many participants expressed guilt and shame for not being able to accomplish their antepartum goals. Life experiences and stressors, lack of breastfeeding role models, limited experiences with breastfeeding and lactation, and changes to the family dynamic played a major role in the infant feeding decision making process and breastfeeding duration.

Conclusion

Our observations suggest that while exclusivity goals were not being met, a considerable proportion of African American women were breastfeeding. Future interventions geared towards this population should include social media interventions, messaging around combination feeding, and increased education for identified social support persons. Public health measures aimed at reducing the current infant feeding inequities would benefit by also incorporating more culturally inclusive messaging around breastfeeding and lactation.

Keywords: African American mothers, social support, breastfeeding, combination feeding, ethnography, infant feeding, messaging, qualitative research

Breastfeeding provides physiological, psychological, and immunological benefits for mothers and infants and economic benefits for society (American Academy of Pediatrics, [AAP] 2012). While breast milk is considered the gold standard of infant feeding in the United States (US), racial disparities in breastfeeding persist. In the most recent Breastfeeding Report Card, 59% of African American women ever breastfed, whereas 75% of White and 80% of Hispanic women ever breastfed (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2013). Breastfeeding is an especially important public health issue in the African American community which is disproportionately impacted by poor birth outcomes such as prematurity, low birthweight, and infant mortality. While breastfeeding cannot prevent prematurity or low birth weight, it has strong potential to mitigate poor birth outcomes and prevent infant mortality by supporting infant health, neurodevelopment and immune system development in vulnerable infants (AAP, 2012; Kramer & Kakuma, 2012). Being born too early and too small are the strongest indicators of infant mortality, poor child development, chronic disease and premature death in adulthood (Eichenwald & Stark 2008).

Research has shown African American women have intentions of breastfeeding, however their intentions are not being converted into sustained breastfeeding behaviors (Corbett, 2000; Meyerink & Marquis, 2002; Persad & Mensinger; 2008; Spencer & Grassley, 2013). Persad and Mensinger (2008) noted 70% of African American participants wanted to breastfeed, but did not sustain breastfeeding. During the antepartum period, African American women are more likely to select an infant feeding method based on their current lifestyles, social support networks, and comfort level (Cricco-Lizza, 2004). The persistent disparity in African American breastfeeding and mismatch between maternal intentions and breastfeeding outcomes suggest new approaches to understanding the context in which African American women’s breastfeeding decisions and experiences are needed. The purpose of this study was to describe the infant feeding decision-making processes of African American mothers and examine the influences of support persons on the infant feeding decision making processes.

Theoretical Perspectives

The theoretical perspectives of Black Feminist Theory (Collins, 2008) and Family Life Course Development Theory (Bengston & Allen, 1993) informed this study. The Family Life Course Development Theory focuses on changes to the familial unit during the perinatal period. Black Feminist Theory takes into consideration the complexity of historical, racial and gender influences that are experienced by African American women (Collins, 2008).

Methods

Design

A longitudinal critical ethnographic approach was used to describe infant feeding decision-making processes of African American mothers from pregnancy to postpartum and influences of their support persons. Critical ethnography focuses on uncovering themes with the purpose of understanding intersections or factors which contribute to disparities and identifying complex theoretical orientation towards culture (Madison, 2005; Thomas, 1992). Moreover, critical ethnography allows access to examine cultural practices, social and economic concerns, power, political, and oppressive dynamics at play in regard to breastfeeding in the African American community (Thomas, 1992).

Sample

A sample of socioeconomically diverse African American women living in the San Francisco Bay Area was recruited through home visiting and public health programs, social media platforms, breastfeeding and parenting support groups, hospital bulletin boards, sororities, and professional and community-based organizations. Inclusion criteria were first pregnancy, self-identified as African American, 18 years of age or older, and English speaking. Pregnant women identified support persons for inclusion in the study.

Data Collection

The University of California, San Francisco Committee on Human Research approved the study. Data were collected over a 15-month period (March 2013 to June 2014). Participants provided signed consent prior to data collection. In-person semi-structured, open-ended interviews occurred in participants’ homes, community based organizations, or coffee shops. Representative questions from the interview guide are listed in Table 1. The interview guide was modified to follow emergent themes. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim by a professional service. Pregnant women and support persons were interviewed separately to obtain their unique perspectives. Participants received a $20.00 gift card upon completion of each interview and field observation.

Table 1.

Sample Interview Guide Questions

| Antepartum |

| Tell me about yourself, where you grew up, your friends and family or those that are most important to you. |

| Tell me about your prenatal care experiences. |

| What does infant feeding mean to you? |

| Have you decided on an infant feeding method? If so, please share your decision with me. |

| How did you come to the decision to (breastfeed or formula feed) your new baby? |

| What experiences have you had with infant feeding in the past? |

| How do you feel about the infant feeding information you have received so far during your pregnancy? Follow-up: More specifically, what information or resources has been the most helpful and what information or resources has not been very helpful? |

| Postpartum |

| Tell me about your birthing experiences. |

| What type of infant feeding support did you receive in the hospital after giving birth? |

| Tell me about your infant feeding experiences since you have been home. |

| How did your social support person(s) view the decision you had made regarding infant feeding? |

| How did your prenatal care provider (or pediatric provider) view the decision you had made regarding infant feeding? Follow-up: Were they supportive or non-supportive of your decision? How was the topic brought up? Did you feel comfortable bringing up the topic with them? Or did they approach you with the topic? |

| What, if anything, would you change about your infant feeding experiences if you could? |

Twenty-five hours of field observations occurred during the perinatal period at participants’ baby showers and breastfeeding and other support groups. Observations occurred at community-based organizations or in participants’ homes. Verbal consent was obtained for the observations, which focused on the physical, social and emotional environments surrounding African American women and their families.

Data Analysis

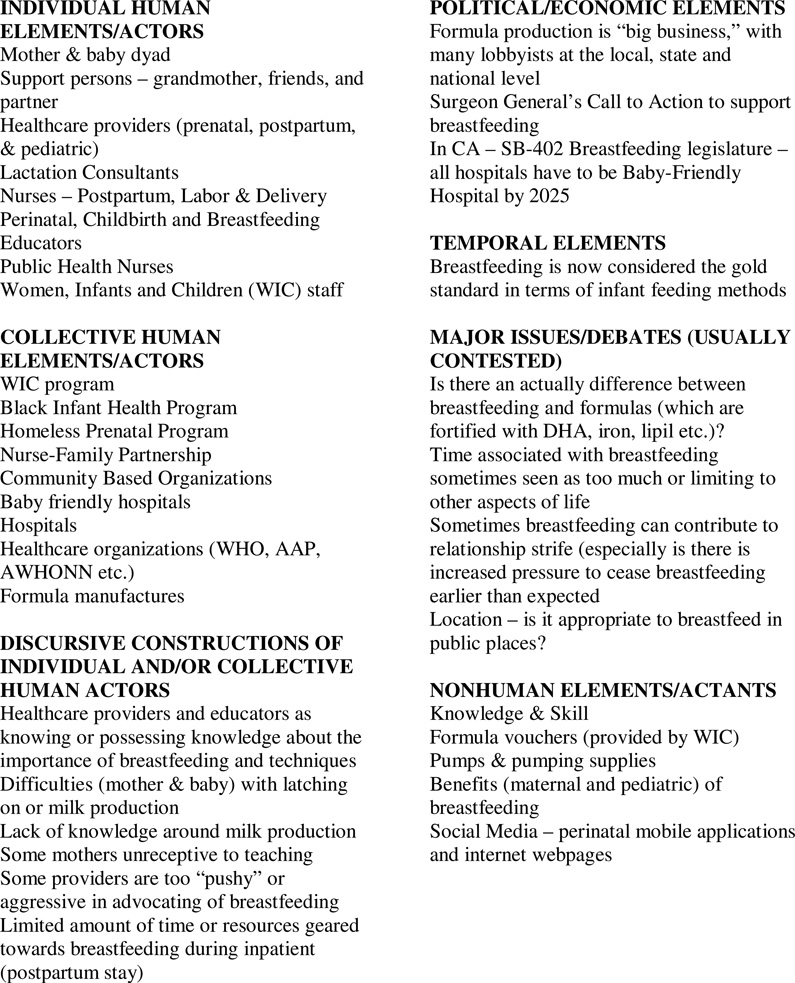

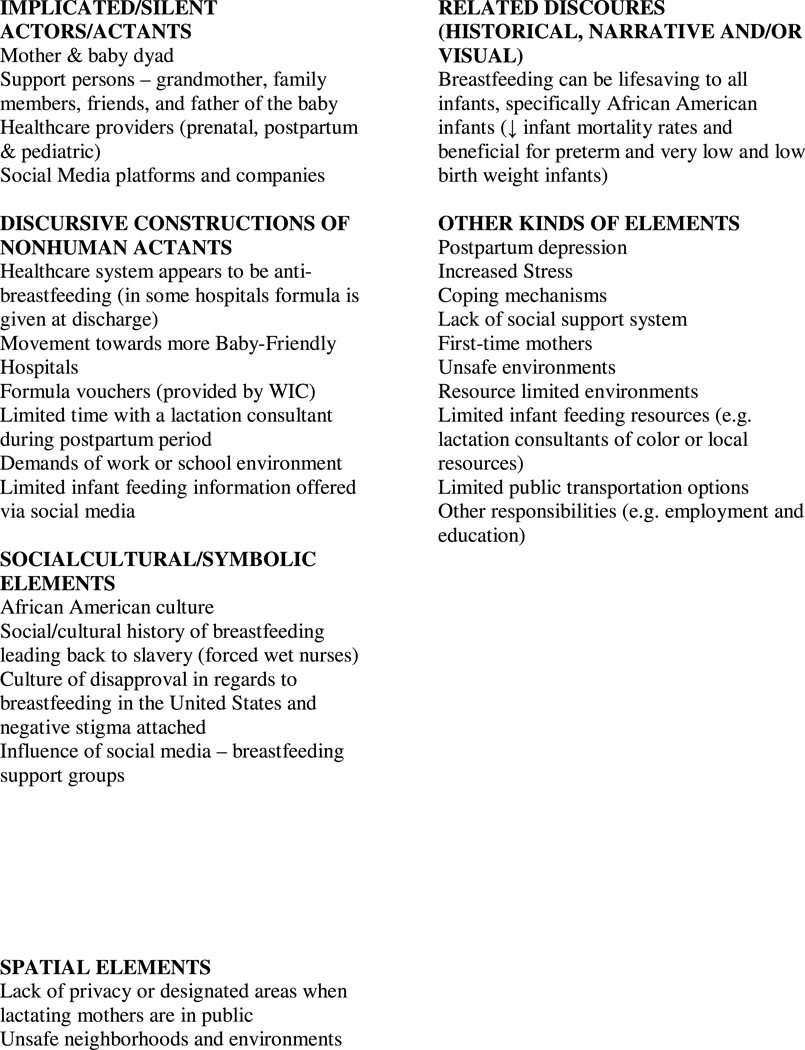

Data collection and analysis occurred simultaneously. For the purposes of this study, we operationalized exclusive breastfeeding to mean infants who only received breast milk and no other type of supplementation. A theoretical and latent data analytical approach was used to identify themes (Aronson 1994; Braun & Clark 2006). Thematic analysis is a widely used qualitative method for examining, describing, and analyzing cluster patterns found within data (Aronson 1994; Braun & Clark 2006). Transcripts were reviewed for accuracy and coded line by line by the first author. Initial codes were clustered into categories, which were used to form themes. As themes were identified, member validation was used to confirm the findings and inform subsequent interviews and field observations. Reflective memos, thematic maps, and field notes were also used to organize and describe participants’ infant feeding decision-making processes. Situational maps were used to illustrate human and non-human elements influencing the infant feeding decision-making processes of African American mothers. Moreover, situational maps were used to examine the significant factors and environments which impacted the breastfeeding climate for African American mothers and their support persons, see Figure 1 (Clarke, 2003).

Figure 1.

Ordered Situational Map

Results

A total of 22 research participants (14 pregnant women and eight support persons) participated in this study. Pregnant women’s ages ranged from 21 to 36 years, with a median age of 23.5 years. At the time of the first interview, about half of the pregnant participants were married or partnered. Most of the participants were high school graduates and half were employed. A majority of pregnant participants were Medi-Cal recipients. All but one participant received prenatal care in the first trimester. Seven pregnant participants noted an intention to exclusively breastfeed, six participants intended to practice combination feeding (e.g., using both breastmilk and formula), thus 13 participants intended to breastfeed in some capacity.

Support persons included three partners, three friends, one mother, and one grandmother. A majority of the support persons self-identified as African American and were women; their ages ranged from 24 to 77 years, with a median age of 35.5 years. Six support persons wanted their pregnant participant to exclusively breastfeed. Forty-three interviews lasting 60 to 90 minutes were conducted. Thirty interviews were conducted with the pregnant participants (14 antepartum interviews and 16 postpartum interviews) and 13 interviews with their support persons (five antepartum interviews and eight postpartum interviews). Data saturation was reached with the 22 participants. See Table 2 for demographics.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic Profile of Pregnant Participants and Support Persons

| Pregnant Participants (n = 14) |

Social Support Persons (n = 8) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age | 23.5 years of age (median) 20 to 36 years (range) |

35.5 years of age (median) 20 to 77 years (range) |

| Gestation Age | 32.5 weeks (median) 10 to 40 weeks (range) |

______ |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| African American | 14 | 7 |

| White | 0 | 1 |

| Highest Education | ||

| Some High School | 2 | 1 |

| High school Graduate | 6 | 2 |

| Some College | 4 | 2 |

| College Graduate | 0 | 2 |

| Graduate School | 2 | 1 |

| Employment | ||

| Employed | 7 | 2 |

| Retired | 0 | 1 |

| Self-Employed | 0 | 1 |

| Stay at Home Mother | 0 | 1 |

| Student | 1 | 2 |

| Unable to Work | 5 | 1 |

| Unemployed/looking for work |

2 | 0 |

| Insurance | ||

| Healthy San Francisco | 1 | 0 |

| Medi-Cal | 11 | 2 |

| Medicare | 0 | 1 |

| Parent s Insurance | 0 | 1 |

| Private Insurance | 2 | 4 |

| Yearly Income | ||

| $0.00 – $25,000 | 12 | 5 |

| $25,000 – $50,000 | 0 | 1 |

| $50.00 – $75,000 | 0 | 1 |

| $75,000 – $100,00 | 0 | 0 |

| $100,000 or more | 2 | 0 |

| Unknown | 0 | 1 |

| Housing | ||

| Apartment | 3 | 1 |

| Apartment w/Family | 1 | 2 |

| Homeless | 1 | 0 |

| House | 4 | 3 |

| House w/Family | 1 | 2 |

| With Family | 1 | 0 |

| With Friends | 1 | 0 |

| With Partner | 2 | 0 |

| Chronic Diseases | ||

| Asthma | 3 | 3 |

| Depression | 3 | 0 |

| Diabetes | 1 | 1 |

| Glaucoma | 0 | 1 |

| Hypertension | 0 | 2 |

| Obesity | 1 | 0 |

| Prenatal Care Accessed | ________ | |

| 1st Trimester | 13 | |

| 2nd Trimester | 1 | |

| 3rd Trimester | 0 | |

|

Preferred Infant Feeding Method |

||

| Breastfeeding | 7 | 6 |

| Combination Feeding | 6 | 0 |

| Formula | 1 | 2 |

Themes

Pregnant participants and support persons described the perinatal period as an exciting yet challenging period of their lives. Key themes presented in this paper include: Best for Baby; Normalization and Role Models; Social Support; Fluid Social Dynamics and Resiliency; Seeking Support and Empowerment; Combination Feeding; and Stress, Shame, and Guilt.

Best for Baby

Participants appeared to be actively engaged with the infant feeding decision-making process early in the pregnancy. Infant feeding decision-making choices were influenced by anecdotal stories; participation in prenatal groups and breastfeeding classes; written materials such as pamphlets, booklets and information sheets; breastfeeding instructional videos; and, social media. During the initial interview, many participants equated infant feeding to breastfeeding. Formula was a noted option, however breastfeeding was viewed as the healthier selection. The quotes below illustrate participants’ infant feeding decisions were based primarily on what was best for the baby.

It's healthier for the baby. I would want to have a healthy child as I don’t want anything to go wrong. [Pregnant participant]

Breastfeeding. It’s definitely healthier. I know that…from what I’ve heard from other parents. Most of my co-workers are parents, there’s a lot of value to a mother being able to breastfeed at least for the first couple of months because nutrients, in addition to the immune system, is strengthened by that process. [Support person]

Normalization and Role Models

Exclusive breastfeeding appeared not to be a social norm or modeled behavior. A majority of participants reported limited exposure to women who breastfed. If breastfeeding was practiced, it was portrayed as a private activity. Many participants reported formula as the preferred infant feeding method in their households. As demonstrated by the quotes below, most participants recalled observing few, if any, breastfeeding women in their surroundings.

Yeah. ‘Cause breastfeeding was really private in my family. So when we breastfed a child, we weren’t in a room with everyone else. It’s not like we saw breastfeeding….I didn’t know how to breastfeed. I just saw bottles because they had milk bottles. [Pregnant participant]

No. Uh, just bottle feeding…I would imagine if [breastfeeding] was happening, it was happening in private. So I haven’t been too privy to that. [Support person]

Though formula feeding appeared to be the prevailing feeding method, a few participants witnessed or recalled hearing about successful breastfeeding. Those participants believed their early breastfeeding experiences played an important role in their current infant feeding beliefs and preferences. As indicated in the quotes below, participants with positive visual experiences and memories of breastfeeding were likely to be supportive of breastfeeding for themselves or their partner, family member or friend.

I grew up in a household where my mother nursed me for 18 months and my grandmother breastfed my mother and my uncle. You know my great-grandmother breastfed just because formula wasn't really [available]. [Support person]

All my sisters did it [breastfeed]…Well, you know, I was with my twin when she gave birth to both of my nieces…when she started breastfeeding, my nieces just latched right on, and that’s like when I see we’re very blessed. [Pregnant participant]

Social Support

Social support played a major role in the continuation or early cessation of breastfeeding. Participants’ decision to breastfeed or formula feed was often influenced by the perspectives of persons in their social networks (e.g., family members, friends, co-workers, public health nurses, and church members). A majority of participants reported having both positive and negative infant feeding conversations about breastfeeding with family members and friends. These conversations lead to questions, doubts, and concerns over their desire and ability to breastfeed. One pregnant participant said,

Some of my family members like my sister said her milk was drying up. I think my grandmother told me one of my aunts didn’t make any milk at all and I had a friend who was like, ‘Oh. I’m not making enough milk’ and at the point in time when I was hearing that information, I didn’t know enough myself to be like, ‘Maybe you need to talk to a lactation consultant’ but most of those conversations just highlighted the lack of information and support for breastfeeding women. [Pregnant participant]

Fluid Social Relationships and Resiliency

Changes in the social dynamics and structures of pregnant participants’ lives occurred during the study. Two pregnant participants reported feeling uncomfortable asking family members or other persons in their social network to participate in the study since previous requests for support had not been received. Another pregnant participant expressed not feeling supported by anyone in her family. In total, six women chose to participate in the study without a support person.

Participants reported having positive, mixed, and negative social support experiences. The quote below illustrates positive support received by a pregnant participant from her husband.

Yeah well luckily I have a pretty good husband that knows when I’m creating enough [stress] to just calm me down so he’s good. Otherwise…here I don’t have a super huge amount of like support. [Pregnant participant]

Other pregnant participants often did not receive the needed and expressed support for childcare, financial and housing assistance, emotional encouragement, and social interactions. These pregnant participants reported strained relationships with partners or family members and tentative living arrangements, resulting in feelings of loneliness, isolation, and sadness. One participant shared.

I mean, [my boyfriend] is supportive but I'm getting more support from my mom and dad … My mom is helping me emotionally because I had the baby blues for like the first two weeks when I came home. I was crying and stuff because [my boyfriend] was acting different… [Postpartum participant]

Despite difficult transitions throughout the perinatal period, a majority of mothers demonstrated resilience. One postpartum participant said,

Yeah. But [newborn] making me a lot stronger being a mom. Because me and my mom are very close but we got in an argument…. And it’s hard because I'm an only child and we’re very close. But there were days like, You know what? I'm not even worried about it anymore. It’s like I'm focusing on my son. And focusing on being a better parent, going to school, getting a job. [Postpartum participant]

Some pregnant participants felt ignored and unsupported by family members and friends for their decision to become a mother. As first time mothers, many participants described the need to defend their parenting skills. Participants often felt as if they were not as important as the baby. In the quote below, a postpartum mother described how she felt about her family’s attention being only on the newborn.

Don’t always be asking about the baby. It isn’t just about the baby…it has been the whole nine months everybody have been asking baby, baby, baby….Now, the baby’s here, it’s still baby, baby, baby, but you want to still feel important. You want to still feel like people care about what’s going on with you as well. [Postpartum participant]

Seeking Support and Empowerment

In an effort to create a supportive environment, participants sought assistance from community resources. All participants attended an antepartum, postpartum class, or support group related to childbirth, parenting, breastfeeding, etc. They noted the importance of having fellowship, interacting socially, and receiving encouragement from other women in their situation; and, they provided and received advice about feeding, sleeping, clothing, bottles, and skincare for their infants. Below are quotes from two postpartum participants describing experiences in community and public health programs.

It’s [public health program] cool. It’s a lot of black girls…I first started when I was pregnant…I’m lucky because all the girls, are cool….They all got babies, they’re all young like me and everything. [Postpartum participant]

I go to [a community-based organization] and now there’s a class called Knowing Your Baby and there’s…about five other women in the class and we all breastfeed and it’s like really empowering to be in a room full of women that are breastfeeding, it makes me feel really good. [Postpartum participant]

The support received from members and leaders of the different support groups was critical, especially if the participant was trying to exclusively breastfeed or had a strained social relationship with family or friends.

Combination Feeding

While breastfeeding was portrayed as the best method of infant feeding, combination feeding emerged as an important theme during the postpartum period. Many participants attempted to exclusively breastfeed; however, combination feeding was the most commonly practiced infant feeding method. Only four mothers were exclusively breastfeeding at the time of the second interview, between two and three months postpartum. For participants who were combination feeding, breastfeeding was typically a night activity or a practice done only at home. Formula was primarily used while mothers were out in public or when the baby was left in the care of others. Two participants explained,

When I come home from work, I pump him one bottle but I’m not getting that much anymore now because during the day he drinks formula. [Postpartum participant]

I do breastfeed him when I’m at home but if I leave him with somebody else then they bottle [formula] feed him… [Postpartum participant]

Combination feeding was prevalent among participants pursuing educational or employment goals. Defensiveness around the term, combination feeding, was noted as participants believed they were still breastfeeding mothers, even if they were supplementing with formula as illustrated in the quotes below.

So when you say exclusive, I mean giving him one formula bottle like every couple of nights is that still exclusively breastfeeding?…I don’t like that because it makes me feel like, oh it’s not enough. But I know it’s enough because 99.99.99% of his meals are from my boob. [Postpartum participant]

And then you know, if he’s still hungry you still have to supplement with formula and be okay with that, but you know we understood ultimately always to breastfeed first. [Support person]

Stress, Shame, and Guilt

Every participant reported feelings of stress and guilt associated with motherhood and unsuccessful breastfeeding experiences. Mothers expressed shame related to early cessation of breastfeeding, supplementation with formula, lack of milk production, and relationship issues with a significant other or family members. One postpartum participant shared.

I feel guilty about giving him formula because the bond that we have and sometimes I know when he’s sleepy or when he’s restless, he wants to breastfeed and I’m not there… [Postpartum participant]

Tearing of the eyes, softening of the voice, increased fidgeting and avoidance of eye contact were observed when mothers were discussing barriers to successful breastfeeding. They had high expectations and felt inadequate if they were unable to meet feeding goals set during the antepartum period. One participant explained,

I had a total like…I broke down. It’s like oh I can’t make enough to feed my baby like that’s what I’m supposed to do and like I said nobody even mentioned that might happen, so yeah it was just like, you know, shocking and upsetting…but then also there’s like disappointment and feeling inadequate. [Postpartum participant]

Discussion

First-time African American mothers in this study acknowledged an intent to breastfeed during the antepartum period. This finding is important as it contradicts the current depiction of African American women as non-breastfeeding mothers (CDC, 2013). Their intention to breastfeed was consistent with their social support person’s desire for them to breastfeed. Participants discussed the benefits and importance of breastfeeding for the wellbeing and development of infants. Consistent with the public health literature (US DHHS, 2011) and historical accounts of breastfeeding patterns among African American women (Barber 2005; Dunaway 2003), few participants recalled observing breastfeeding during their childhood.

Exclusive breastfeeding as the prevailing social norm was not observed in this sample of African American women. Cultural narratives around infant feeding and breastfeeding specific resource allocations have created a challenging climate for breastfeeding women, particularly among African American women. Beal, Kuhlthau, & Perrin (2003) reported African American women were less likely to receive breastfeeding information or support from WIC professionals, while Sable and Patton (1998) noted prenatal providers were more likely to provide breastfeeding advice to White, married, first-time mothers, who were not participating in the WIC program. Kulka et al. (2011) described the lack of breastfeeding support provided to African American women by their support persons, employers, and healthcare providers during the perinatal period. Recent studies have noted in-hospital healthcare providers are less likely to discuss breastfeeding options or services with African American women and maternity care practices supportive of breastfeeding are limited in communities with higher African American populations (Cricco-Lizza 2006; Lind et al. 2014; McKinney et al. 2016).

Attempts and expectations to initiate and continue exclusive breastfeeding were unsuccessful for a majority of the sample, resulting in feelings of guilt, inadequacy, and embarrassment. Unsuccessful breastfeeding initiation has been associated with maternal shame, guilt, and loss (Hauck & Irurita, 2003; Hauck, Langton, & Coyle, 2002; Taylor & Wallace, 2012). The importance of social support systems was a salient theme in this study. This central study finding reaffirmed the importance of positive social interactions throughout one’s life course for physical, psychological, emotional, and overall wellbeing (Mickens, Modeste, Montgomery, & Taylor 2009). Social networks can play an integral role in the way one experiences and sees the world, especially in the African American community (Wills, Eder, Lindsay, Chavez, & Shelton 2004). Findings indicate systematic social and professional supports need to be available throughout the perinatal period for successful breastfeeding among first-time African American mothers.

Limitations

The perspectives presented in this article were from a small sample of first-time African American mothers and their support persons from similar socioeconomic backgrounds and geographic locations. Thus, study findings are not intended to be generalizable to all first-time African American mothers and their support persons. Every effort was made to enroll social support persons of each participant into the study, specifically partners and grandmothers. However, some participants were without a partner or social support system or preferred not to include persons from their social network. Further research specifically focused on breastfeeding perceptions and experiences of partners and social support persons is recommended.

Conclusions

The positive benefits of breastfeeding for mothers and infants are well established. It is important to understand barriers associated with low breastfeeding rates in the African American community. African American women and their infants would benefit greatly from interventions which emphasize social support systems as an integral part of breastfeeding. Much of the education and messaging around breastfeeding promotes exclusive breastfeeding. Minimal time is spent discussing the effects of combination feeding or preparing mothers for the possibility of supplementation with formula. This type of anticipatory guidance may help mothers overcome feelings of guilt and inadequacy when attempts to exclusively breastfeed are unsuccessful. Adequate access to breastfeeding resources and support is vital. Interventions must take into consideration the intersectional experiences of African American women.

Significance.

Breastfeeding is protective of maternal and infant health. African American infants have the highest rates of infant mortality, premature birth, low birth weight and very low birth weight. Increasing breastfeeding rates in the African American community can play a vital role towards reducing poor infant outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to acknowledge and thank all of the study participants and recruitment sites. We also want to thank Kathryn Lee for her critical critique of the manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) (Grant 5F31NR013120), UCSF Graduate Student Research Award and Sigma Theta Tau International, Alpha Eta Research Award and also supported in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through UCSF-CTSI Grant Number KL2TR000143. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the views of NIH, NINR, UCSF or Sigma Theta Tau International.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Policy Statement Paper. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):827–841. [Google Scholar]

- Aronson J. A Pragmatic View of Thematic Analysis. The Qualitative Report. 1994;2(1) [Google Scholar]

- Barber K. The Black Woman's Guide to Breastfeeding: The Definitive Guide to Nursing for African American Mothers. Naperville, Illinois, Sourcebooks, Inc.; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Beal AC, Kuhlthau K, Perrin JM. Breastfeeding advice given to African American and white women by physician and WIC counselors. Public Health Reports. 2003;118(4):368–376. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50264-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Progress in Increasing Breastfeeding and Reducing Racial/Ethnic Differences — United States, 2000–2008 Births. 2013 Feb 8; Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6205a1.htm.

- Clarke A. Situational Analyses: Grounded Theory Mapping After the Postmodern Turn. Symbolic Interaction. 2003;26:553–576. [Google Scholar]

- Collins PH. Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. New York: Routledge; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Corbett KS. Exploring Infant Feeding Style of Low-Income Black Women. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2000;15(2):73–81. doi: 10.1053/jn.2000.5445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cricco-Lizza R. Infant feeding beliefs and experiences of Black women enrolled in WIC in the New York metropolitan area. Qualitative Health Research. 2004;14:1197–1210. doi: 10.1177/1049732304268819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K. Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory, and Antiracist Politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum. 1989:139–167. [Google Scholar]

- Davis A. Women, Race, and Class. New York: Random House; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Dunaway WA. The African-American Family in Slavery and Emancipation (Studies in Modern Capitalism) Cambridge, England; New York: Cambridge University Press; 2003. pp. 127–157. [Google Scholar]

- Eichenwald EC, Stark AR. Management and outcomes of very low birth weight. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;358(16):1700–1711. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0707601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauck Y, Irurita V. Incompatible expectations: The dilemma of breastfeeding mothers. Health Care For Women International. 2003;24(1):62–78. doi: 10.1080/07399330390170024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauck YL, Langton D, Coyle K. The path of determination: exploring the lived experience of breastfeeding difficulties. Breastfeeding Review. 2002;10(2):5–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer MS, Kakuma R. The optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012;2012(8) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003517.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulka TR, Jensen E, McLaurin S, Woods E, Kotch J, Labbok M, Bowling M, Dardess P, Baker S. Community based participatory research of breastfeeding disparities in African American women. Infant Child Adolescent Nutrition. 2011;3(4):233–239. doi: 10.1177/1941406411413918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madison DS. Critical Ethnography: methods, ethics, and performance. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mickens AD, Modeste N, Montgomery S, Taylor M. Peer support and breastfeeding intentions among Black WIC participants. Journal of Human Lactation. 2009;25:157–162. doi: 10.1177/0890334409332438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyerink RO, Marquis GS. Breastfeeding initiation and duration among low-income women in Alabama: The importance of personal and familial experiences in making infant-feeding choices. Journal of Human Lactation. 2002;18(1):38–45. doi: 10.1177/089033440201800106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persad M, Mensinger JL. Maternal breastfeeding attitudes: Association with breastfeeding intent and socio-demographics among urban primiparas. Journal of Community Health. 2007;33:53–60. doi: 10.1007/s10900-007-9068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sable MR, Patton CB. Prenatal Lactation Advice and Intention to Breastfeed: Selected Maternal Characteristics. Journal of Human Lactation. 1998;14(1):35–40. doi: 10.1177/089033449801400113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer BS, Grassley JS. African American women and breastfeeding: An integrative literature review. Health Care For Women International. 2013;34(7):607–625. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2012.684813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spradley JP. The Ethnographic Interview. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor EN, Wallace LE. For Shame: Feminism, Breastfeeding Advocacy, and Maternal Guilt. Hypatia. 2012;27(1):76–98. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J. Doing Critical Ethnography (Qualitative Research Methods) London: Sage Publications; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Support Breastfeeding. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Willis W, Eder C, Lindsay S, Chavez G, Shelton S. Lower Rates of Low Birthweight and Preterm Births in the California Black Infant Health Program. The Journal of the National Medical Association. 2004;96(3):315–324. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. Infant and young child feeding: Model Chapter for textbooks for medical students and allied health professionals. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]