Abstract

Objectives:

To determine the gender differences in cardiovascular risk profile and outcomes among patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Methods:

In a prospective multicenter study of consecutive Middle Eastern patients managed with PCI from January 2013 to February 2014 in 12 tertiary care centers in Amman and Irbid, Jordan. Clinical and coronary angiographic features, and major cardiovascular events were assessed for both genders from hospital stay to 1 year.

Results:

Women comprised 20.6% of 2426 enrolled patients, were older (mean age 62.9 years versus 57.2 years), had higher prevalence of hypertension (81% versus 57%), diabetes (66% versus 44%), dyslipidemia (58% versus 46%), and obesity (44% versus 25%) compared with men, p<0.001. The PCI for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction was indicated for fewer women than men (23% versus 33%; p=0.001). Prevalence of single or multi-vessel coronary artery disease was similar in women and men. More women than men had major bleeding during hospitalization (2.2% versus 0.6%; p=0.003) and at one year (2.5% versus 0.9%; p=0.007). There were no significant differences between women and men in mortality (3.1% versus 1.7%) or stent thrombosis (2.1% versus 1.8%) at 1 year.

Conclusion:

Middle Eastern women undergoing PCI had worse baseline risk profile compared with men. Except for major bleeding, no gender differences in the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events were demonstrated.

Cardiovascular disease is the a leading cause of death among men and women worldwide, including the Middle East.1,2 Several studies had suggested that women presenting with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and/or undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) have worse baseline cardiovascular risk profile, more comorbidities, and higher incidence of short- and long-term adverse cardiovascular events compared with men.3,4 Other studies had suggested that women are less prescribed evidence-based medications and undergo coronary revascularization procedures at lower rates than men.5 However, several other studies did not demonstrate the presence of such gender related differences in the rate of adverse events in women compared with men.6,7 It is largely unknown if there are gender differences among Middle Eastern patients who undergo PCI. The First Jordanian PCI Registry (JoPCR1) was designed to evaluate in hospital and one year outcomes among Middle Eastern patients undergoing PCI patients. The objectives of this study were to determine the gender-differences in baseline cardiovascular risk profile, comorbidities, and the incidence rates of adverse cardiovascular events during admission and 12 months after the procedure.

Methods

Consecutive patients who underwent PCI for ACS or stable coronary disease (SC) at 12 tertiary care hospitals in Amman and Irbid, Jordan (2 university hospitals, one public teaching hospital, 3 private teaching hospitals, and 6 private non-teaching hospitals) between January 2013 and February 2014 were enrolled in this prospective, observational registry. A case report form was used to record patients’ data prospectively during index hospitalization, and at 1, 6, and 12 months after discharge. Data were collected during follow-up out-patient visits or through phone calls to the patients, household relatives or primary care physicians. We compared women with men in terms of baseline characteristics including clinical, laboratory, electrocardiographic (EKG), echocardiographic, and coronary angiographic features. Percutaneous coronary intervention procedures and short- and long-term outcomes were assessed in women compared with men.

All PCI procedures were performed according to current standard guidelines. Patients were pre-treated with aspirin and a second oral antiplatelet agent (clopidogrel or ticagrelor). The arterial access site, antithrombotic therapy, and type of stent were all left to operator’s discretion. Acute coronary syndrome was classified as acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI); or non-ST-segment elevation ACS (NSTEACS). The latter includes non-ST-segment elevation MI (NSTEMI) and unstable angina (UA).

Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) was continued for at least one year in patients who had PCI for ACS. In those who had PCI for SC; DAPT was continued for at least one month when bare metal stents (BMS) were used and for at least one year if drug-eluting stents (DES) were used. The adverse clinical events that were evaluated in women and men during admission, and after 1, 6, and 12 months; included cardiac mortality (all deaths were considered cardiac unless a definite noncardiac cause could be established), definite and probable stent thrombosis, as defined by the Academic Research Consortium,8 major bleeding events, as defined according to the Can Rapid risk stratification of Unstable angina patients Suppress Adverse outcomes with Early implementation of the ACC/AHA guidelines (CRUSADE) study classification,9 and readmission for ACS, heart failure or target coronary artery revascularization. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of each participating hospital and the study was conducted according to principles of Helsinki Declaration.

Data were described and analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Science (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) version 20. Data were described using means, standard deviations, or percentages wherever appropriate. The gender differences in the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patients and the differences in the coronary angiography and PCI procedures and the cardiovascular events during admission, at 1 and 12 months were tested using chi-square test. The differences in the cardiovascular events at 12 months between men and women were tested using binary logistic regression after adjusting for important demographic and clinical characteristics. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

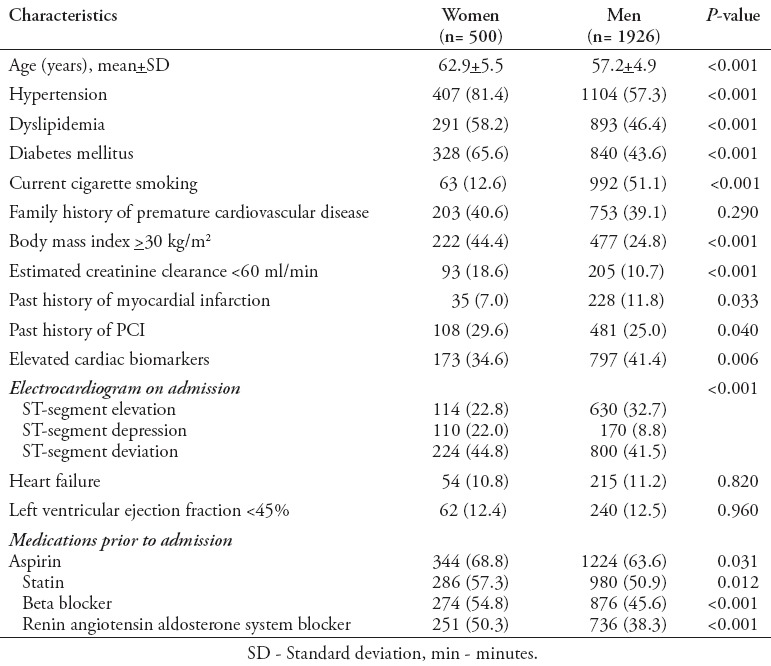

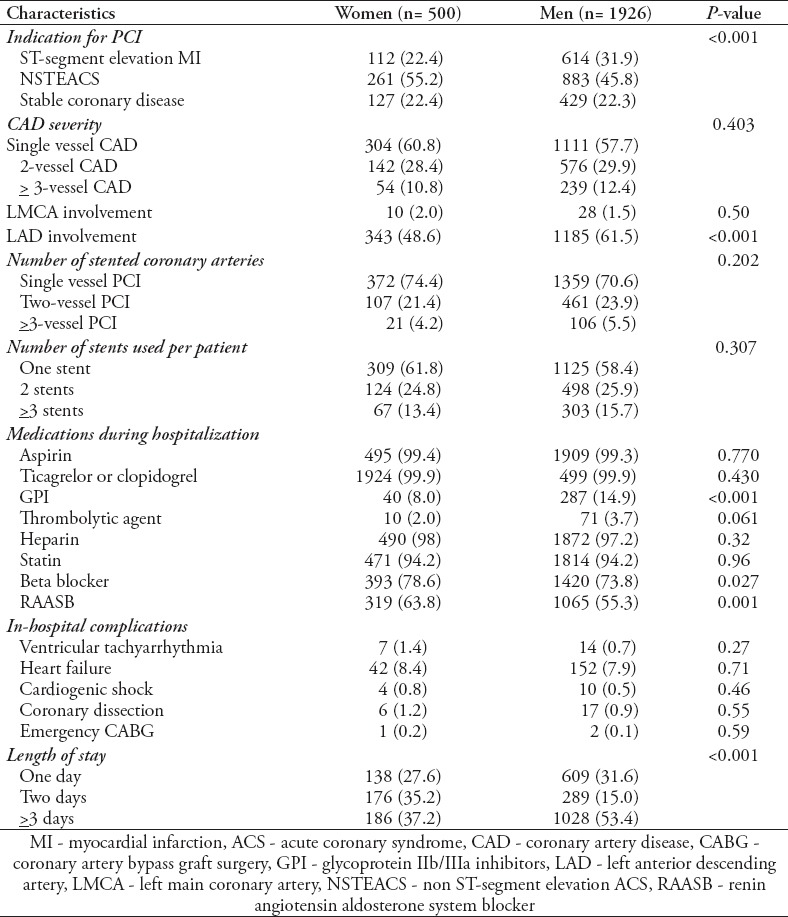

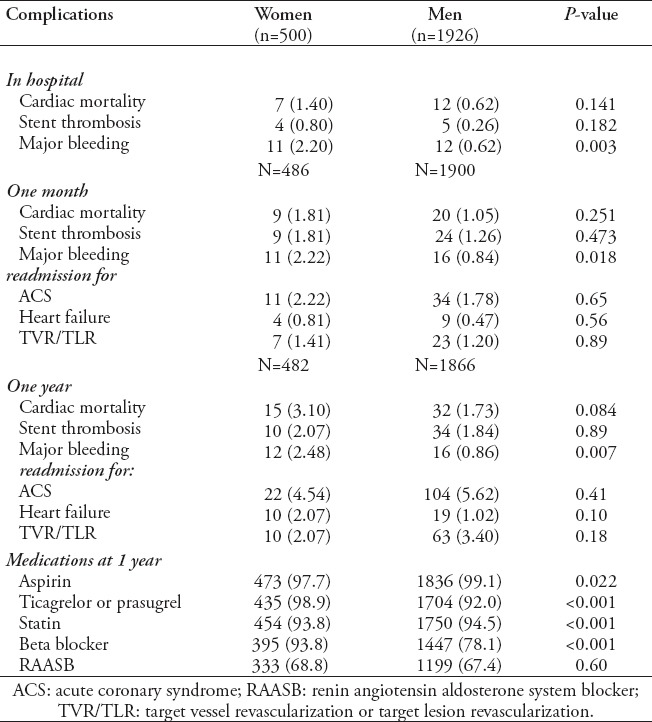

A total of 2,426 patients enrolled in the study, 500 (20.6%) were women and 1,926 (79.4%) were men. The baseline characteristics in women and men are depicted in Table 1. Women were, on average, 6 years older than men. They had higher prevalence of 4 major cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and obesity) than men. Women were less likely to have ST-segment deviation or elevated serum cardiac biomarkers than men. Acute coronary syndrome was the indication for PCI in similar percentages of women and men (77.6% and 77.7%), but women were less likely to have STEMI, and more likely to have NSTEACS compared with men (Table 2). The severity of coronary artery disease (CAD) and the number of the stented coronary arteries in women were not different from those in men, and women had less involvement of the left anterior descending coronary artery. In-hospital procedure-related complications were not different in both groups, and fewer women received glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors than men. The 3 major adverse cardiac events (cardiac mortality, stent thrombosis, and major bleeding) were numerically higher in women than in men, but the differences were statistically significant only for major bleeding events (Table 3). The one year incidence of major bleeding was also higher in women than that in men (2.48% versus 0.86%, p=0.007).

Table 1.

The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) according to gender.

Table 2.

Coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) procedures among patients who underwent PCI according to gender.

Table 3.

Cardiovascular events during admission, at one month and one year

In the multivariate analysis, women had higher odds of major bleeding compared with men (Odds ratio [OR]: =3.7; 95% Confidence interval [CI]: 1.6, 8.5; p=0.002) after adjusting for demographic and clinical characteristics. Although the one year death rate was numerically higher among women compared with men (3.10% versus 1.73%, p=0.084), this difference was not statistically significant in the multivariate analysis (OR: =2.01; 95% CI: 0.85, 4.75; p = 0.111) after adjusting for age, diabetes, hypertension, multivessel, and ejection fraction. Readmission rates at 1 and 12 months for ACS, coronary revascularization, or heart failure in women were not different from that in men.

Discussion

This study showed that women were older and had worse baseline cardiovascular risk profile compared with men. Except for the incidence of major bleeding events, women did not have higher incidence of PCI complications or major cardiovascular events during hospitalization or at one year compared with men. These findings are consistent with several recent studies from different geographical regions in the world.3,6,7,10,11

Gender-related disparities, for example, higher rates of readmission, reinfarction, and deaths in the first year after MI in women, demonstrated by some studies were most likely related to the undertreatment of women with guidelines-based medications and invasive procedures.3-5

Unlike the inconsistencies in the gender-related differences in outcome observed in many studies, less inconsistencies were observed in the presence of worse baseline risk profile of women presenting with ACS, including higher incidence of hypertension, DM, dyslipidemia, obesity, heart failure, chronic lung disease, and peripheral arterial disease.3,12-15 However, the prevalence rates of hypertension, DM, and obesity that were observed in women in our study were higher than those reported by Western studies.3,14,16-18

Evolving gender-specific research has demonstrated that although men and women share similar risk factors for coronary artery disease, women often have more clustering of risk factors19 and worse vascular impact of certain risk factors, such as cigarette smoking, DM, depression, and other psychosocial stresses, compared with men.3,20

Despite the greater risk factor burden, women paradoxically have less severe obstructive epicardial CAD at elective angiography than men,3 and have more incidence of microvascular disease, coronary spasm and spontaneous coronary artery dissection.17-19,21,22 Similar to our findings, women are less likely to present with STEMI than NSTEACS compared with men.9 The treatment received by women in our study was not inferior to that received by men. In fact, beta blockers and renin angiotensin aldosterone blocker were more likely prescribed to women than men. glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors was underused in women than in men due to less prevalence of 2 indications of this medication in women; namely, ST-segment deviation and elevated serum cardiac biomarkers. Contemporary ACS management has demonstrated that women derive a significant long-term benefit from invasive strategy as men do despite procedure-related complications mostly related to smaller coronary arteries and more extensive and complex CAD.16,23-25

In concordance with other studies, major bleeding events in the hospital were significantly higher among females in our study.26-28 Reasons for this include more vascular access bleeding due to smaller artery size, peripheral artery disease, and inappropriate doses of antithrombotic medications in women.9,28,29 Bleeding, the most significant non ischemic complication associated with PCI, is an independent predictor of in-hospital and 1 year mortality.30,31

Few limitations in our study warrant discussion. Inherent to similar observational registries, the study is subject to selection bias, collection of non-randomized data, and missing or incomplete information.32 Participation was voluntary and the enrolment of consecutive patients was encouraged. Acute coronary syndrome patients who died before or shortly after admission were not included. Moreover, those who did not undergo coronary angiography or had coronary angiography but were give medical treatment of referred to coronary artery bypass graft surgery were not represented in this study. The participating hospitals are high volume tertiary care centers; thus the, results may not represent the PCI practice and outcome in all areas in the country or region.33 Despite the fact that this study was not designed to test the specific differences between men and women, this study is unique in that it evaluated short- and long-term outcomes of ACS patients who underwent PCI in the Middle East, a region that is not well presented in cardiovascular interventional studies and registries.

In conclusion, no gender-related differences in the incidence of major were observed following PCI in this contemporary Middle Eastern population, except for more major bleeding events in women. The low rate of PCI-related complications observed in our study during hospitalization up to 1 year of follow up is encouraging and gives a strong impetus for practicing cardiologists to adopt invasive strategy in women presenting with ACS. Vigilance for bleeding, adopting bleeding risk scores and appropriate use of antithrombotic and antiplatelet therapy can minimize the bleeding risk observed in women. Given the increasing awareness by patients, the public, and healthcare providers of the prevalence and impact of coronary heart disease in women, it is timely to review the current status and issues concerning coronary intervention in women.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank the members of the The First Jordanian percutaneous coronary intervention Registry Investigators Group: Abdelbasit Khatib, MD; Abdelfattah Al-Nadi, RN; Abeer Al Bashaireh, PharmD; Ahmad Abdulsattar, MD; Ahmad Harassis, MD, FACC; Akram Saleh, MD; Aktham Hiari, MD, FACC; Ali Shakhatreh, MD; Amr Rasheed, MD; Assem Nammas, MD, FACC; Ayed Al-Hindi, MD; Azzam Jamil, MD; Bashar Al A’Amar, MD; Batool Haddad, PharmD; Dalal Al-Natour, PharmD; Hadi Abu-Hantash, MD, FACC; Hanan Abunimeh, PharmD; Haneen Kharabsheh, PharmD; Hasan Tayyim, PharmD; Hatem Tarawneh, MD, FACC; Hisham Janabi, MD; Husam Khader, RN; Hussein Al-Amrat, MD; Ghaida Melhem, PharmD; Ibrahim Abu Ata, MD, FACC; Ibrahim Jarrad, MD, FESC; Jamal Dabbas, MD; Kamel Touqan, MD; Laith Nassar, MD; Lewa Al- Hazaimeh, MD; Mahmoud Eswed, MD; Mazen Sudqi, MD; Medhat Bakri, MD; Mohammad Bakri, MD; Mohammed Mohialdeen, MD; Mohannad Momani, RN; Monther Hassan, MD; Nadeen Kufoof, PharmD; Najat Afaneh, PharmD; Nael Shobaki, MD; Nidal Hamad, MD, FACC; Nuha Abu-Diak, PharmD; Osama Okkeh, MD; Qasem Al-Shamayleh, MD, FACC; Raed Awaysheh, MD; Ryad Jumaa, MD; Sahm Gharaibeh, MD; Saleh Eliamat, RN; Yousef Qussous, MD, FACC; Zakaria Qaqa, MD, FACC; Ziad Abu Taleb, MD.

Footnotes

Ethical Consent.

All manuscripts reporting the results of experimental investigations involving human subjects should include a statement confirming that informed consent was obtained from each subject or subject’s guardian, after receiving approval of the experimental protocol by a local human ethics committee, or institutional review board. When reporting experiments on animals, authors should indicate whether the institutional and national guide for the care and use of laboratory animals was followed.

References

- 1.Gehani AA, Al-Hinai AT, Zubaid M, Almahmeed W, Hasani MR, Yusufali AH, et al. Association of risk factors with acute myocardial infarction in Middle Eastern countries: the INTERHEART Middle East study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2014;21:400–410. doi: 10.1177/2047487312465525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Regitz-Zagrosek V, Oertelt-Prigione S, Prescott E, Franconi F, Gerdts E, Foryst-Ludwig A, et al. Gender in cardiovascular diseases: impact on clinical manifestations, management, and outcomes. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:24–34. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehta LS, Beckie TM, DeVon HA, Grines CL, Krumholz HM, Johnson MN, et al. Acute Myocardial Infarction in Women: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133:916–947. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sjauw KD, Stegenga NK, Engstrom AE, van der Schaaf RJ, Vis MM, Macleod M, et al. The influence of gender on short- and long-term outcome after primary PCI and delivered medical care for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. EuroIntervention. 2010;5:780–787. doi: 10.4244/eijv5i7a131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnston N, Schenck-Gustafsson K, Lagerqvist B. Are we using cardiovascular medications and coronary angiography appropriately in men and women with chest pain? Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1331–1336. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chieffo A, Hoye A, Mauri F, Mikhail GW, Ammerer M, Grines C, et al. Gender-based issues in interventional cardiology: a consensus statement from the Women in Innovations (WIN) initiative. EuroIntervention. 2010;5:773–779. doi: 10.4244/eijv5i7a130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Carlo M, Morici N, Savonitto S, Grassia V, Sbarzaglia P, Tamburrini P, et al. Sex-related outcomes in elderly patients presenting with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome. Insights from the Italian Elderly ACS Study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:791–796. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2014.12.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cutlip DE, Windecker S, Mehran R, Boam A, Cohen DJ, van Es GE, et al. Clinical end points in coronary stent trials: a case for standardized definitions. Circulation. 2007;115:2344–2351. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.685313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Subherwal S, Bach RG, Chen AY, Gage BF, Rao SV, Newby LK, et al. Baseline risk of major bleeding in non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: the CRUSADE (Can Rapid risk stratification of Unstable angina patients Suppress ADverse outcomes with Early implementation of the ACC/AHA guidelines) Bleeding Score. Circulation. 2009;119:1873–1882. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.828541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vaccarino V, Badimon L, Corti R, de Wit C, Dorobantu M, Hall A, et al. Ischaemic heart disease in women: are there sex differences in pathophysiology and risk factors? Position paper from the working group on coronary pathophysiology and microcirculation of the European Society of Cardiology. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;90:9–17. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghali WA, Faris PD, Gallbraith PD, Norris CM, Curtis MJ, Suanders LD, et al. Sex differences in access to coronary revascularization after cardiac catheterization: importance of detailed clinical data. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:723–732. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-10-200205210-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reynolds HR, Farkouh ME, Lincoff AM, Hsu A, Swahn E, Sadowski ZP, et al. Impact of female sex on death and bleeding after fibrinolytic treatment of MI in GUSTO V. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:2054–2060. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.19.2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pancholy SB, Shantha GP, Patel T, Cheskin LJ. Sex differences in short-term and long-term all-cause mortality among patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated by primary percutaneous intervention: a meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1822–1830. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hvelplund A, Galatius S, Madsen M, Rasmussen JN, Rasmussen S, Madsen JK, et al. Women with acute coronary syndrome are less invasively examined and subsequently less treated than men. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:684–690. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mikhail GW, Gerber RT, Cox DA, Ellis SG, Lasala JM, Orminston JA, et al. Influence of sex on long-term outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention with the paclitaxel-eluting coronary stent. Results of the “TAXUS Woman” analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3:1250–1259. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2010.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seth A, Serruys PW, Lansky A, Hermiller J, Onuma Y, Miquel-Herbert K, et al. A pooled gender based analysis comparing the Xience V everolimus-eluting stent and the Taxus paclitaxel-eluting stent in male and female patients with coronary artery disease, results of the SPIRIT II and SPIRIT III studies: two-year analysis. EuroIntervention. 2010;5:788–794. doi: 10.4244/eijv5i7a132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Onuma Y, Kukreja N, Daemen J, Garcia-Garcia HM, Gonzalo N, Cheng JM, et al. Impact of sex on 3-year outcome after percutaneous coronary intervention using bare-metal and drug-eluting stents in previously untreated coronary artery disease: insights from the RESEARCH (Rapamycin-Eluting Stent Evaluated at Rotterdam Cardiology Hospital) and T-SEARCH (Taxus-Stent Evaluated at Rotterdam Cardiology Hospital) Registries. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:603–610. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamm CW, Bassand JP, Agewall S, Bax J, Boersma E, Bueno H, et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. The Task Force for the management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2999–3054. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gabizon I, Lonn E. Young women with acute myocardial infarction and the post-hospital syndrome. Circulation. 2015;132:149–151. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalyani RR, Lazo M, Ouyang P, Turkbey E, Chevalier K, Brancati F, et al. Sex differences in diabetes and risk of incident coronary artery disease in healthy young and middle-aged adults. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:830–838. doi: 10.2337/dc13-1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shaw LJ, Bugiardini R, Merz CN. Women and ischemic heart disease: evolving knowledge. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1561–1575. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vaccarino V, Parsons L, Every NR, Barron HV, Krumholz HM. Sex-based differences in early mortality after myocardial infarction. National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 2 Participants. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:217–225. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907223410401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wenger NK, Brindis RG, Casey DE, Jr, Ganiats TG, Holmes DR, Jr, Jaffe AS, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;130:e344–e426. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mehran R, Kini AS. Sex-related outcomes after drug-eluting stent. Should we “never mind” or “mind” the gap? JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3:1260–1261. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krumholz HM, Douglas PS, Lauer MS, Pasternak RC. Selection of patients for coronary angiography and coronary revascularization early after myocardial infarction: is there evidence for a gender bias? Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:785–790. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-116-10-785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahmed B, Dauerman HL. Women, bleeding, and coronary intervention. Circulation. 2013;127:641–649. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.108290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alexander KP, Chen AY, Newby LK, Schwartz JB, Redberg RF, Hochman JS, et al. CRUSADE (Can Rapid risk stratification of Unstable angina patients Suppress Adverse outcomes with Early implementation of the ACC/AHA guidelines) Investigators. Sex differences in major bleeding with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors: results from the CRUSADE (Can Rapid risk stratification of Unstable angina patients Suppress ADverse outcomes with Early implementation of the ACC/AHA guidelines) initiative. Circulation. 2006;114:1380–1387. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.620815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ndrepepa G, Berger PB, Mehilli J, Seyfarth M, Neumann FJ, Schömig A, et al. Periprocedural bleeding and 1-year outcome after percutaneous coronary interventions: appropriateness of including bleeding as a component of a quadruple end point. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:690–697. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lindsey JB, Marso SP, Pencina M, Stolker JM, Kennedy KF, Rihal C, et al. Prognostic impact of periprocedural bleeding and myocardial infarction after percutaneous coronary intervention in unselected patients: results from the EVENT (Evaluation of Drug-Eluting Stents and Ischemic Events) registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:1074–1082. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eikelboom JW, Mehta SR, Anand SS, Xie C, Fox KA, Yusuf S. Adverse impact of bleeding on prognosis in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2006;114:774–782. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.612812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nikolsky E, Mehran R, Dangas G, Fahy M, Na Y, Pocock SJ, et al. Development and validation of a prognostic risk score for major bleeding in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention via the femoral approach. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1936–1945. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lenzen MJ, Boersma E, Bertrand ME, Maier W, Moris C, Piscione F, et al. Management and outcome of patients with established coronary artery disease: Euro Heart Survey on coronary revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:1169–1179. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wijns W, Kolh PH. Experience with revascularization procedures does matter: low volume means worse outcome. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1954–1957. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]