Abstract

AIM

To evaluate the clinicopathological features and the surgical outcomes of patients with fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma (FL-HCC) over a 15-year period.

METHODS

This is a retrospective study including 22 patients with a pathologic diagnosis of FL-HCC who underwent hepatectomy over a 15-year period. Tumor characteristics, survival and recurrence were evaluated.

RESULTS

There were 11 male and 11 female with a median age of 29 years (range from 21 to 58 years). Two (9%) patients had hepatitis C viral infection and only 2 (9%) patients had alpha-fetoprotein level > 200 ng/mL. The median size of the tumors was 12 cm (range from 5-20 cm). Vascular invasion was detected in 5 (23%) patients. Four (18%) patients had lymph node metastases. The median follow up period was 42 mo and the 5-year survival was 65%. Five (23%) patients had a recurrent disease, 4 of them had a second surgery with 36 mo median time interval. Vascular invasion is the only significant negative prognostic factor

CONCLUSION

FL-HCC has a favorable prognosis than common HCC and should be suspected in young patients with non cirrhotic liver. Aggressive surgical resection should be done for all patients. Repeated hepatectomy should be considered for these patients as it has a relatively indolent course.

Keywords: Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma, Common hepatocellular carcinoma, Recurrence after resection fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma, Pathology of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma, Survivalefter resection fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma

Core tip: Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma (FL-HCC) has conventionally been considered to be a histologic variant of HCC, with distinct clinicopathologic features. Many series have mentioned that FL-HCC is less aggressive than conventional HCC. However, other studies have failed to confirm the observation of a better outcome in FL-HCC. Our study shows that FL-HCC has a favorable prognosis than common HCC and should be suspected in young patients with non cirrhotic liver. Aggressive surgical resection should be done for all patients. Repeated hepatectomy or excision of recurrent disease should be considered for these patients as it has a relatively indolent course.

INTRODUCTION

Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma (FL-HCC) has conventionally been considered to be a histologic variant of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), with distinct clinicopathologic features. It is a rare primary hepatic malignancy that was first described as a pathological variant of HCC by Edmondson[1] in 1956.

FL-HCC is usually well circumscribed masses characterized by polygonal hepatic cells with deeply eosinophilic cytoplasm and abundant fibrous stroma arranged in thin parallel bands. On gross examination, there is a central scar which resulted from coalesced lamellar bands of fibrosis[2].

The etiology of FL-HCC remains unclear. It typically occurs in normal livers without underlying liver fibrosis or cirrhosis[3]. In contrast to HCC which usually found in the presence of cirrhosis or chronic hepatitis[4]. FL-HCC has been reported to occur in association with focal nodular hyperplasia a type of benign liver lesion[5,6]. Some suggest that FHN may be a benign precursor lesion to FL-HCC as both diseases share several features: They tend to present in younger patients, and in the setting of normal liver parenchyma. Pathologically both have as a stellate central scar on imaging studies and copper accumulation on histological examination[6,7].

Many series have mentioned that FL-HCC is less aggressive than conventional HCC[8-10]. However, other studies have failed to confirm the observation of a better outcome in FL-HCC[11-13]. Other studies reported that the survival was similar between common HCC and FL-HCC, and that may be related to the higher resectability rate which improve the survival of patients with FL-HCC[12,14].

The aim of this study was to evaluate the clinicopathological features and the surgical outcomes of patients with FL-HCC who were referred to our tertiary referral center over a 15-year period.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a retrospective study of patients underwent hepatectomy for a pathologic diagnosis of FL-HCC over an 15-year period between February 1999 to February 2014, in gastroenterology surgical center, Mansoura University, Egypt. A total of 22 patients was diagnosed and underwent hepatectomy during this period. The diagnosis of FL-HCC was made depending on its histological and pathological characteristics by an independent pathologic team.

All patients were subjected to clinical assessment; laboratory investigation and imaging work up including: Ultrasonography, Enhanced computed tomography and MRI imaging study to evaluate the extent of the tumor, vascular involvement and lymph node affection. Clinicopathological parameters, including gender and age of patients; location, size and number of the tumor; safety margins; vascular invasion; lymph node metastasis status; operative details; morbidity and mortality; and survival and recurrence were collected. The parenchymal disease of the liver is defined as hepatitis C antibody and/or hepatitis B surface antigen was present. Safety margin is defined as complete tumor excision after surgical treatment proved by pathologic examination of the resected margins. Patients with synchronous malignancies were excluded from the study. Non of our patients underwent preoperative portal vein embolization or chemoembolization and they did not received adjuvant treatment.

Clinical staging of the tumor was performed using the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging criteria[15]. The extent of hepatic resection was defined according to the Brisbane 2000 Terminology of Liver Anatomy and Resections[16]: Right hepatectomy involves resection of segments V-VIII, whereas left hepatectomy involves resection of segments (II-IV). Extended right hepatectomy involves resection of segments IV-VIII, whereas extended left hepatectomy involves resection of segments (II-IV, V, VIII). All these resection may or may not involve segment I. Most of liver resections were performed with selective vascular inflow occlusion. However, intermittent clamping was used in selected patients to avoid ischemia of the remnant liver. Liver transsection was performed using harmonic scalpel, ultrasonic dissector. Follow-up was obtained in the out-patient clinic by personal contact with the patients.

Survival analysis

Log-rank test and Kaplan-Meier curves were used for survival analysis. For continuous variables, descriptive statistics were calculated and were reported as median. Categorical variables were described using frequency distributions. Mortality was defined as death occurring in the hospital or within 30 d. Significance was defined as P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Twenty two patients with FL-HCC were diagnosed in our retrospective data base. All our patients underwent partial hepatectomy over a 15-year period. There were 11 male and 11 female with a median age of 29 years (range from 21 to 58 years). Two patients (9%) had liver cirrhosis due to hepatitis C viral infection while the remaining patients had a normal liver, and only 2(9%) patients had high AFP levels (> 200 ng/mL) (Table 1). In comparison to HCC, patients with common HCC were evaluated at our center[17], it was predominantly in male, the mean age was 54.8 ± 9.2 years, 100% had cirrhotic liver and AFP levels were elevated in all patients. FL-HCC represents about 3% of patients with hepatic malignancies (1260 patients) during the study period.

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| FL-HCC (n = 22) | |

| Median age, years (range) | 29 yr (21 to 58) |

| Male/female | 11/11 (50%:50%) |

| Hepatitis or cirrhosis | 2 (9%) |

| Elevated AFP (> 200 ng/mL) | 2 (9%) |

FL-HCC: Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma; AFP: Alpha-fetaprotein.

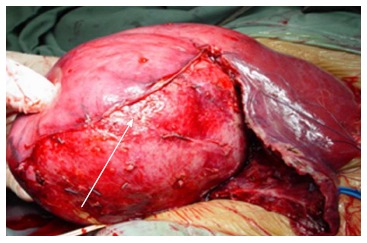

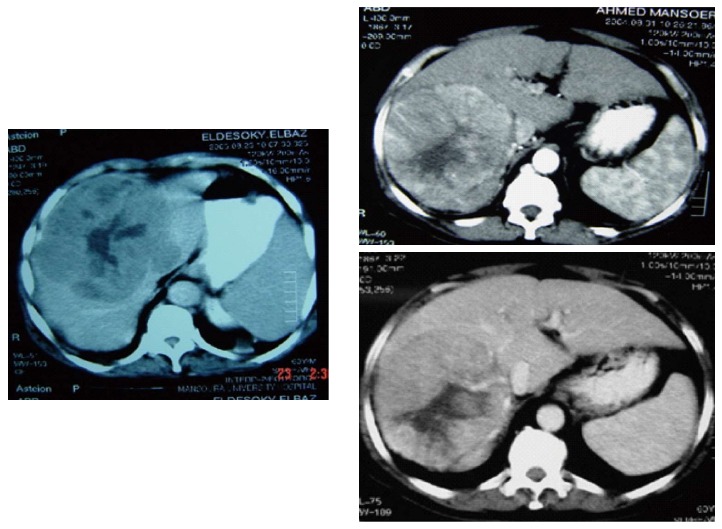

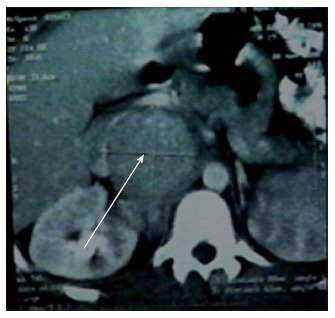

Vague abdominal pain was the most common presentation, other were asymptomatic and discovered incidentally during physical examination or routine imaging work up. These tumors are well circumscribed, large and often have areas of hypervascularitywith a central scar Figure 1. Figure 2 shows FL-HCC at left liver lobe while Figure 3 demonstrates a different CT scans for FL-HCC in the right liver lobe.

Figure 1.

Large right lobe fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma.

Figure 2.

Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma left lobe.

Figure 3.

Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma right lobe.

Surgery and pathology

The type of hepatic resection for our 22 patients is shown in Table 2. Seventy three percent of cases required hepatectomy and 18% needed extended hepatectomy to excise their tumors. Multiple primary tumors were present in 3 patients. The median size of the tumors was 12 cm (range from 5-20 cm). Vascular invasion was detected in 5 (23%) patients. Four of those patients had microscopic vascular invasion, and one had microscopic invasion of the right hepatic vein. The safety margin was invaded in 2 (9%) patients who might be due to presence of the tumor closer tovascular structures which couldn’t be resectable. Four (18%) patients had lymph node metastases.

Table 2.

Tumor characteristics’ and treatment features n (%)

| FL-HCC (n = 22 ) | |

| Number | |

| Single | 19 (86) |

| Multiple | 3 (14) |

| Size (cm) | Median 12 cm (range, 5-20 ) |

| Location | 9 right, 10 left, 3 bilateral |

| Hepatic resection | |

| Hepatectomy | 16 (73) |

| Extended hepatectomy | 4 (18) |

| Localized resection | 2 (9) |

| Stage | |

| I | 10 (45) |

| II | 5 (23) |

| III | 7 (32) |

| IV | 0 |

| Nodal metastases | 4 (18) |

| Vascular invasion | 5 (23) |

| Positive safety margin | 2 (9) |

| Repeated hepatectomy | 4 (18) |

FL-HCC: Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma.

In this study, 5 patients had a recurrent disease.Four patients had a second surgery with 36 mo median time interval. Three patients had a repeated liver resection (including both patients with microscopic invasion of resection margins and 1 patient with vascular invasion) and one patient underwent resection of large retro-caval lymph node (Figure 4). The last patient had peritoneum dissemination and nothing was done for him. The median survival was 28 mo after the second operation in these patients. There was no hospital mortality.

Figure 4.

Large retro-caval lynph node 2-year after resection fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma.

Overall survival

The median overall survival in our 22 patients was 88 mo and the 5-year survival was 65%. The median follow up period was 42 mo. In our experience of hepatic resection for HCC in cirrhotic liver (n = 175), the median survival after surgical resection was 24 mo while 5-year survival was 10.7%[17].

The univariate analysis for overall survival was performed and includes the following variables: Age, gender, size and number of tumors, type of hepatic resection, vascular invasion, nodal metastases, and resection margins (Table 3). The two patients with positive microscopic margins developed a recurrent disease. Although radically resected patients have a prolonged survival (87 mo vs 72 mo) it is not reach a statistical significance. Only vascular invasion was significant.

Table 3.

Clinicopathologic features and survival in fibrolamellar carcinoma (figures in parenthesis reflect percentages)

| Factor | n (%) | Overall survival (mo) | P value |

| Age (yr) | |||

| < 40 | 16 (73) | 86 | |

| ≥ 40 | 6 (27) | 72 | 0.4 |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 11 (50) | 84 | |

| Male | 11 (50) | 79 | 0.6 |

| Tumor size (cm) | |||

| < 10 | 8 (36) | 82 | |

| ≥ 10 | 14 (64) | 76 | 0.3 |

| Number | |||

| 1 | 19 (86) | 89 | |

| > 1 | 3 (14) | 77 | 0.2 |

| Hepatic resection | |||

| Hepatectomy | 16 (73) | 86 | |

| Extended hepatectomy | 4 (18) | 77 | |

| Localized resection | 2 (9) | 79 | 0.62 |

| Nodal metastases | |||

| Negative | 18 (82) | 88 | |

| Positive | 4 (18) | 78 | 0.09 |

| Vascular invasion | |||

| Absent | 17 (77) | 92 | |

| Present | 5 (23) | 58 | 0.03 |

| Safety margin | |||

| Negative | 20 (91) | 87 | |

| Positive | 2 (9) | 72 | 0.08 |

In our study, we have 8 patients with greater than 5-years follow up. Of these patients, 4 died of disease at 63, 67, 74 and 88 mo. Four patients were alive at 65-92 mo after surgery with no evidence of a recurrent disease.

DISCUSSION

FL-HCC has been considered to be a histologic variant of HCC, with distinctive morphological and clinical setting. This study confirms the distinctive clinicopathological finding of other studies that FL-HCC were larger in size than conventional HCC, affects young patients with no sex predilection and occurs in the healthy liver in absence of parenchymal disease or cirrhosis and without elevation of AFP level (Table 4)[18-21]. Elevations in AFP levels are uncommon with less than 10% of patients have AFP levels greater than 200 ng/mL[21]. In this study, only 2 patients (9%) had high AFP level (> 200 ng/mL).

Table 4.

Published series on fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma

| Ref. | n | Age | Male:female | Cirrhosis/ hepatitis | AFP elevated | Median size (cm) | > 1 tumor | Positive node | Vascular invasion | Initial operation | Repeat operation | Median f/u | 5 yr survival | Prognostic factor |

| Hemming et al[18], 1997 | 10 | 31 | 50:50 | NR | 10% | 8 | 20% | 20% | NR | Phx 100% | 50% | 101 | 70% | NR |

| El-Gazzaz et al[19], 2000 | 20 | 27 | 65:35 | 0% hep B | 0% | 14 | 20% | 30% | 55% | Phx 55% OLT 45% | NR | 25 | 50% | NONE |

| Kakar et al[20], 2005 | 20 | 27 | 53:27 | 0% | 3/13 (23%) | < 10 31% ≥ 10 69% | 10% | 35% | NR | Phx 100% | NR | NR | 62% | Metastasis at presentation |

| Stipa et al[21], 2006 | 28 | 28 | 43:57 | 0% | 7% | 9 | 11% | 50% | 36% | Phx 100% | 61% | 34 | 76% | Positive LN |

| Present study | 22 | 29 | 50:50 | 9%/hepc | 9% | 12 | 13% | 18% | 23% | Phx 100% | 18% | 42 | 65% | Vascular invasiom |

Hep: Hepatitis; AFP: Alpha-fetoprotein elevated (> 200 ng/mL); Phx: Partial hepatectomy; NR: Not reported; f/u: Follow up.

FL-HCC occurs in normal livers without underlying liver fibrosis or cirrhosis[3]. Pinna 1997, reported that 6% of his patients were hepatitis C positive and 7% had cirrhotic liver[10]. In our study, 2 patients (9%) were hepatitis C antibody positive, this may be attributed to high prevalence of hepatitis C virus in our community.

Preoperatively, FL-HCC can be diagnosed by CT scan and MRI imagingcharacteristicas these tumors are usually heterogenous with areas of hypervascularity. Preoperative biopsy was avoided and our patients underwent surgery without biopsy which was reserved for patients who are unresectable. Ichikawa et al[22] 1999 reported that FL-HCC had 68% calcification, 65% abdominal lymphadenopathy and 71% central scar.

Surgical resection is the only hope for these patients which should be done whenever possible. Our patients had 73% hepatectomy, 18% extended hepatectomy, while only 9% needed localized resection. The 5-year survival was 65% after resection, which was comparable to the 50%-70% 5-year survival rates in other reported studies (Table 4)[18-21].

Several factors have been identified in the surgical studies of FL-HCC that can predict worse prognosis. More than one tumor, metastasis at presentation, vascular invasion and positive lymph nodes[10,12,20,21] have been identified to be a negative prognostic factors. In this study, vascular invasion is the only significant negative prognostic factor after resection.

Our patients have a low rate of lymph node metastasis (18%) compared to other series which range from 20%-50% (Table 4). This may be related to different tumor biology and the presence of liver cirrhosis in 9% of patients which may delay lymphatic metastases due to inhibition lymphatic outflow from the liver. On our published study on common HCC[17], lymph node metastases were found on only 8 from 175 patients (8%) this may confirm the previous data.

Despite the relatively indolent tumor biology of FL-HCC, it recurs after surgical resection. The site of recurrences includes the liver, regional lymph nodes, peritoneum, and lung[23]. Some authors recommend resection of a recurrent disease due to its indolent course and absence of alternative treatment option[2]. Four patients (18%) underwent a second surgery for a recurrent disease. Three patients underwent hepatic resection while one patient underwent resection of large retro-caval lymph node. This rate is lower than the reports 50%-61% in the other series[18,21]. However, the median survival was 28 mo after the second operation.

The aggressiveness and outcomes of FL-HCC vary significantly between previously published series. Some studies reported that FL-HCC is less aggressive than conventional HCC[8-10,24,25]. Other series reported that survival of FL-HCC was similar with common HCC[12,14] while other pathology and hepatology texts mention that it is associated with favorable prognosis[26-29]. Kakar et al[20], 2005 reported that FL-HCC is an aggressive tumor and nearly that half of patients develops lymph node or distant metastasis. In our study, the FL-HCC has an indolent course than common HCC, better 5-year survival can be reached in absence of vascular invasion and positive safety margins.

In conclusion, FL-HCC has a favorable prognosis than common HCC and should be suspected in young patients with non cirrhotic liver. Aggressive surgical resection should be done for all patients. Repeated hepatectomy or excision of recurrent disease should be considered for these patients as it has a relatively indolent course.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all staff members of gastroenterology center.

COMMENTS

Background

Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma (FL-HCC) has conventionally been considered to be a histologic variant of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), with distinct clinicopathologic features. It is a rare primary hepatic malignancy. The etiology of FL-HCC remains unclear. It typically occurs in normal livers without underlying liver fibrosis or cirrhosis. In contrast to HCC which usually found in the presence of cirrhosis or chronic hepatitis. Some suggest that FHN may be a benign precursor lesion to FL-HCC as both diseases share several features: they tend to present in younger patients, and in the setting of normal liver parenchyma. The prognosis of FL-HCC is differ from common HCC.

Research frontiers

Many series have mentioned that FL-HCC is less aggressive than conventional HCC. However, other studies have failed to confirm the observation of a better outcome in FL-HCC. Other studies reported that the survival was similar between common HCC and FL-HCC, and that may be related to the higher resectability rate which improve the survival of patients with FL-HCC. The aim of this study was to evaluate the clinicopathological features and the surgical outcomes of patients with FL-HCC who were referred to their tertiary referral center over a 15-year period.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The epidemiology, surgical management and outcomes for patients with FL-HCC differs from one area of the world to another. The authors have a published data and experience from Western, Eastern and European countries. However, The authors have a little data from Middle East countries, and here they represent their work from a large gastroenterology and transplantation center in Egypt in dealing with patients with FL- HCC over a 15 years period.

Applications

The surgery of FL-HCC is differs from HCC as it occurs in non-cirrhotic liver, so aggressive surgery was adopted for more radical surgery even for a recurrent disease.

Terminology

Clinical staging of the tumor was performed using the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging criteria. The extent of hepatic resection was defined according to the Brisbane 2000 Terminology of Liver Anatomy and Resections: Right hepatectomy involves resection of segments V-VIII, whereas left hepatectomy involves resection of segments (II-IV). Extended right hepatectomy involves resection of segments IV-VIII, whereas extended left hepatectomy involves resection of segments (II-IV, V, VIII).

Peer-review

This manuscript seems worth to be reported, because clinicopathological features of FL-HCC are clearly written.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: This study was approved by institutional review board Faculty of medicine Mansoura University, Code number: R/16.01.03.

Informed consent statement: Informed consent was obtained from all patients to undergo surgery after a careful explanation of the nature of the disease and possible treatment with its complications.

Conflict-of-interest statement: No conflict of interest; No financial support.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Egypt

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

Peer-review started: September 19, 2016

First decision: October 21, 2016

Article in press: December 14, 2016

P- Reviewer: Ooi LLPJ, Otsuka M, Pirisi M S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

References

- 1.Edmondson HA. Differential diagnosis of tumors and tumor-like lesions of liver in infancy and childhood. AMA J Dis Child. 1956;91:168–186. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1956.02060020170015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Craig JR, Peters RL, Edmondson HA, Omata M. Fibrolamellar carcinoma of the liver: a tumor of adolescents and young adults with distinctive clinico-pathologic features. Cancer. 1980;46:372–379. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800715)46:2<372::aid-cncr2820460227>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collier NA, Weinbren K, Bloom SR, Lee YC, Hodgson HJ, Blumgart LH. Neurotensin secretion by fibrolamellar carcinoma of the liver. Lancet. 1984;1:538–540. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)90934-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McLarney JK, Rucker PT, Bender GN, Goodman ZD, Kashitani N, Ros PR. Fibrolamellar carcinoma of the liver: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 1999;19:453–471. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.19.2.g99mr09453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imkie M, Myers SA, Li Y, Fan F, Bennett TL, Forster J, Tawfik O. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma arising in a background of focal nodular hyperplasia: a report of 2 cases. J Reprod Med. 2005;50:633–637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vecchio FM, Fabiano A, Ghirlanda G, Manna R, Massi G. Fibrolamellar carcinoma of the liver: the malignant counterpart of focal nodular hyperplasia with oncocytic change. Am J Clin Pathol. 1984;81:521–526. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/81.4.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vecchio FM. Fibrolamellar carcinoma of the liver: a distinct entity within the hepatocellular tumors. A review. Appl Pathol. 1988;6:139–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Serag HB, Davila JA. Is fibrolamellar carcinoma different from hepatocellular carcinoma? A US population-based study. Hepatology. 2004;39:798–803. doi: 10.1002/hep.20096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okuda K. Natural history of hepatocellular carcinoma including fibrolamellar and hepato-cholangiocarcinoma variants. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:401–405. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pinna AD, Iwatsuki S, Lee RG, Todo S, Madariaga JR, Marsh JW, Casavilla A, Dvorchik I, Fung JJ, Starzl TE. Treatment of fibrolamellar hepatoma with subtotal hepatectomy or transplantation. Hepatology. 1997;26:877–883. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruffin MT. Fibrolamellar hepatoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:577–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ringe B, Wittekind C, Weimann A, Tusch G, Pichlmayr R. Results of hepatic resection and transplantation for fibrolamellar carcinoma. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1992;175:299–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katzenstein HM, Krailo MD, Malogolowkin MH, Ortega JA, Qu W, Douglass EC, Feusner JH, Reynolds M, Quinn JJ, Newman K, et al. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma in children and adolescents. Cancer. 2003;97:2006–2012. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagorney DM, Adson MA, Weiland LH, Knight CD, Smalley SR, Zinsmeister AR. Fibrolamellar hepatoma. Am J Surg. 1985;149:113–119. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(85)80019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Joint Committee on Cancer. American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual, 7th. In: Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al (Eds). Springer, New York; 2010. p. 175. [Google Scholar]

- 16.The Brisbane 2000 Terminology of Liver Anatomy and Resections. HPB. 2000;2:333–339. doi: 10.1080/136518202760378489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abdel-Wahab M, El-Husseiny TS, El Hanafy E, El Shobary M, Hamdy E. Prognostic factors affecting survival and recurrence after hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic liver. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2010;395:625–632. doi: 10.1007/s00423-010-0643-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hemming AW, Langer B, Sheiner P, Greig PD, Taylor BR. Aggressive surgical management of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 1997;1:342–346. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(97)80055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El-Gazzaz G, Wong W, El-Hadary MK, Gunson BK, Mirza DF, Mayer AD, Buckels JA, McMaster P. Outcome of liver resection and transplantation for fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Transpl Int. 2000;13 Suppl 1:S406–S409. doi: 10.1007/s001470050372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kakar S, Burgart LJ, Batts KP, Garcia J, Jain D, Ferrell LD. Clinicopathologic features and survival in fibrolamellar carcinoma: comparison with conventional hepatocellular carcinoma with and without cirrhosis. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:1417–1423. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stipa F, Yoon SS, Liau KH, Fong Y, Jarnagin WR, D’Angelica M, Abou-Alfa G, Blumgart LH, DeMatteo RP. Outcome of patients with fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2006;106:1331–1338. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ichikawa T, Federle MP, Grazioli L, Madariaga J, Nalesnik M, Marsh W. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma: imaging and pathologic findings in 31 recent cases. Radiology. 1999;213:352–361. doi: 10.1148/radiology.213.2.r99nv31352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Epstein BE, Pajak TF, Haulk TL, Herpst JM, Order SE, Abrams RA. Metastatic nonresectable fibrolamellar hepatoma: prognostic features and natural history. Am J Clin Oncol. 1999;22:22–28. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199902000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hodgson HJ. Fibrolamellar cancer of the liver. J Hepatol. 1987;5:241–247. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(87)80580-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wood WJ, Rawlings M, Evans H, Lim CN. Hepatocellular carcinoma: importance of histologic classification as a prognostic factor. Am J Surg. 1988;155:663–666. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(88)80139-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Everson GT, Trotter JF. Transplantation of the liver. In: Schiff ER, Sorrell MF, Maddrey WC (eds), editors. Diseases of the Liver. 9th ed. Vol. 2. Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins: Philadelphia; 2003. pp. 1585–1614. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sherlock S, Dooley J (eds) Diseases of the Liver and Biliary System, 11th edn. Blackwell Science: Malden, MA; 2003. Malignant liver tumors; pp. 537–562. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosai J. Rosai and Ackerman’s Surgical Pathology. 9th ed. Mosby: Philadelphia; 2004. pp. 1001–1002. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferrell LD. Benign and malignant tumors of the liver. In: Odze RD, Goldblum JR, Crawford JM (eds), editors. Surgical Pathology of the GI Tract, Liver, Biliary Tract and Pancreas. Saunders: Philadelphia; 2004. p. 1012. [Google Scholar]