Abstract

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) recently implemented the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement (CJR) model. While many stakeholders are enthusiastic that the program will reduce spending for joint replacement, others are concerned that the program will unintentionally penalize hospitals that treat medically complex patients. This concern stems from the fact that the program may not include a mechanism to sufficiently account for patient complexity (i.e., risk adjustment). Using Medicare claims, we examined this concern and found an inverse association between patient complexity and year-end bonuses (i.e., reconciliation payments). Specifically, reconciliation payments were reduced by $827 per episode for each standard deviation increase in a hospital’s patient complexity (p<0.01). Moreover, we found that risk adjustment could increase reconciliation payments to some hospitals by as much as $114,184 annually. Our findings suggest that CMS should include risk adjustment in the CJR model and future bundled payment programs.

INTRODUCTION

On April 1st 2016, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) implemented the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement (CJR) model.1 This program introduced mandatory episode-based bundled payments to 800 hospitals across 67 metropolitan statistical areas.2 To the extent that lower extremity joint replacement is one of the most common procedures performed among Medicare beneficiaries, the CJR model represents perhaps the most aggressive move yet by CMS toward alternative payment models. Under the CJR model, all providers (e.g., hospitals, physicians, post-acute care providers) will continue to receive standard fee-for-service payments from Medicare for all claims from admission through 90 days after discharge. However, at the end of each performance year, CMS will compare participating hospitals’ 90-day episode payments against a “target episode price” based on historical spending for this procedure. Hospitals will receive additional payments if their actual 90-day episode spending (and that of their affiliated physicians and post-acute care providers) is less than the target, but will be required to pay CMS back if their episode spending exceeds this metric. In the CJR model, such bonuses and penalties are referred to as “reconciliation payments”.

In contrast to prior bundled payment demonstrations from CMS (e.g., Bundled Payments for Care Improvement initiative), CJR is unique in that each hospital’s target episode price is calculated by blending its own historical episode spending with the average spending of other hospitals in the same region. Over time, the blended price is increasingly weighted towards the regional benchmark such that, by the fourth year of the program, the target price is based entirely on regional episode spending. By implementing region-based target pricing, CMS is aiming to reduce episode payment variation resulting from disparate practice patterns (e.g., post-acute care utilization) across geographic regions.

While differences in hospital episode spending can certainly be driven by variation in service utilization, it is also true that payment differences can reflect the disparities in patient complexity (i.e., hospital case-mix).3 While this issue may be less relevant for a program like BPCI, where an individual hospital’s spending is benchmarked against its own historical episode payments, the CJR model is different because it determines reconciliation payments by benchmarking a hospital performance against other hospitals in a given region without accounting for patient-specific factors (e.g., age, medical comorbidities, functional status) that are known to impact episode spending. During the rulemaking period, many commenters identified this issue as an important limitation of the CJR model and expressed reservations that, by not adjusting for hospital case-mix, CMS may unfairly penalize hospitals that treat more medically complex patients.

Despite these concerns, CMS did not include a mechanism to account for important patient characteristics such as age and comorbidity in the calculation of target prices, offering several reasons for this decision. First, CMS stated that there is no need for additional risk adjustment because there is sufficient stratification of patients through the use of different target prices for episodes associated with complicated inpatient stays (i.e., MS-DRG 469) or hip fractures. Second, they argued that there is no gold standard risk adjustment model for patients undergoing joint replacement. Third, commercially available risk adjustment tools were built using different patient populations than those in the CJR model and may therefore not be applicable to Medicare beneficiaries. Finally, although CMS uses Hierarchical Condition Category (CMS-HCC) risk scores to predict future expenditures of patients in Medicare Advantage plans4, these scores have not been sufficiently validated for joint replacement episodes. Nonetheless, CMS is currently utilizing a CMS-HCC framework for other programs including Medicare Spending Per Beneficiary Hospital Compare.5 Given the multiple stakeholder concerns around this topic, it seems reasonable for CMS to further evaluate the merits of risk adjustment for CJR and future bundled payment programs.

In this context, we examined the association between patient complexity and hospital reconciliation payments for lower extremity joint replacement episodes, and we estimated the financial impact for hospitals of excluding more granular patient characteristics in the calculation of target prices.

METHODS

Data and study population

We identified all Medicare claims for individuals in the state of Michigan who underwent lower extremity joint replacement (MS-DRG 469 and 470) from 2011 through 2013. We only included patients who underwent one of these procedures in a hospital that was geographically located in a metropolitan statistical area (a requirement for inclusion in the CJR program), and performed more than 20 cases during the study period. We also excluded patients who did not have complete 90-day claims, were not continuously enrolled in Medicare Part A and B, those who died during the episode of care, and those who had HMO coverage or were eligible for Medicare because of end-stage renal disease or disability. In addition, in order to reduce some of the heterogeneity associated with infrequent and expensive procedures, we excluded patients who had a primary diagnosis of fracture (12.3% of episodes). On average fracture cases accounted for 1.5% of an individual hospital’s episodes (range 0.03–5.42%). This study was deemed exempt from review by the Institutional Research Board at our health system.

Defining episodes of care and calculating 90-day episode payments

We defined 90-day episodes of care according to specifications from the CJR program.1 Specifically, we first identified all hospitalization, professional, and post-acute care claims from the index admission through 90 days after discharge and then excluded claims based on DRGs and ICD-9 primary diagnosis codes that matched the exclusion list published by CMS.1 Next, we calculated the total 90-day payment for each joint replacement episode by aggregating the payments received for each claim attributed to the joint replacement episode of care. Then, following the methods used by CMS in the CJR Final Rule, we removed payments for disproportionate share hospitals, indirect medical education, and new technologies. Finally, we truncated extremely high-cost and low-cost episodes to limit the influence of outliers. Specifically, we excluded 362 (1.53%) episodes with 90-day payments lower than $4,000. In addition, we assigned the value of the 95th percentile to episodes with costs above the 95th percentile. CMS uses a similar approach to reduce the impact of outliers in many of their hospital performance programs, including the CJR model. To account for changes in Medicare payments during the years of the study, we adjusted all payments to 2013 dollars.

Defining hospital case-mix and calculating reconciliation payments

We used Medicare claims to calculate a hierarchical condition category (CMS-HCC) risk score for each beneficiary in our study. Specifically, we used HCC software (V1212.70.F1) and collected information (i.e., age, gender, comorbidity, and dual eligible status and original reason for Medicare entitlement) from Medicare claims to calculate each patient’s risk score. Using established methods, we reviewed each patient’s prior 12-months of inpatient, outpatient and select professional claims to collect this information.4 For example, if patient had a joint replacement surgery on October 14, 2011, we searched claims from October 14, 2010 through October 14, 2011 for their comorbidities. We then aggregated these patient risk scores to calculate an average for each hospital. We used average hospital risk-score as a proxy for hospital case-mix.

We calculated each hospital’s reconciliation payment using methods similar to those outlined in the CJR rule. Specifically, we first calculated target prices for each hospital using 2011–2012 spending for MS-DRG 469 and 470 separately. Next, we aggregated 2013 spending for MS-DRG 469 and 470 and subtracted the target amount (i.e., target price multiplied by number of cases for each MS-DRG). Finally, we calculated per capita reconciliation payments by dividing the total reconciliation payment by case volume for each MS-DRG.

Assessing the relationship between hospital case-mix and reconciliation payments under two specific Scenarios

We examined the association between average CMS-HCC risk scores and the estimated reconciliation payments that hospitals would receive under two different Scenarios. In the first Scenario, we calculated reconciliation payments using the hospital’s own 2011–2012 spending to define target episode spending. This Scenario is closely aligned with the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) initiative. In the second Scenario, we used the 2011–2012 average regional spending (average state spending in this case) to set the target episode price. The use of a regional target is consistent with the CJR model. For both Scenarios, we fit linear regression models with heteroscedastic robust standard errors to test the association between CMS-HCC risk scores and reconciliation payments per joint episode. For these models, reconciliation payment per joint episode was used as our dependent variable and CMS-HCC risk score was our primary exposure variable. We also performed a multivariable analysis to examine the independent association of CMS-HCC risk score on reconciliation payments. Based on prior literature, we expected that teaching hospitals, hospitals with a larger number of beds, and those with a higher proportion of Medicaid patients would have higher expenditures, which may in turn impact reconciliation payments. Therefore, these variables were included in our multivariable analysis.

Estimating the impact of risk adjustment on reconciliation payments

We estimated the impact of CMS’ policy decision by calculating the net difference in reconciliation payments that hospitals would receive with and without risk adjustment. Our risk adjustment model included log-transformed 90-day episode payment as our dependent variable and average CMS-HCC risk score as our independent variable. We used the model to estimate an expected 90-day episode payment for each patient and then utilized a standard observed to expected framework to arrive at the risk-adjusted 90-day episode payment.6 Next, we aggregated these risk-adjusted payments to the hospital level and calculated reconciliation payments as described above. Finally, we calculated the difference between the risk-adjusted and unadjusted reconciliation payments for each hospital. All analyses were performed using statistical software (STATA 13/SE, College Station, TX), and at the 5% significance level.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed several sensitivity analyses to confirm our findings. First, we examined variation in average hospital CMS-HCC scores by MS-DRG categories (469 and 470) and fracture status. The purpose of this analysis was to understand how hospitals differed for these specific subpopulations. Second, we examined the association between average CMS-HCC risk score and reconciliation payments after including patients with fractures. Third, we examined the association between average CMS-HCC risk score and reconciliation payments with our truncated cases included. The purpose of the latter two sensitivity analyses was to ensure that our exclusion of fractures and low payment cases would not substantially alter the estimates from our primary analyses. Finally, because we used average state spending to set the regional target price in our analysis and the actual CJR model utilizes average U.S. census division spending, we performed a sensitivity analysis using the target price published by CMS for the East North Central census division (MS-DRG 469: $50,954, MS-DRG 470: $25,480).

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, our analysis of Michigan hospitals may limit the generalizability of this study for national joint replacement bundled payment programs such as CJR. However, this concern is tempered by the fact that Michigan hospitals do not differ in important ways from the hospitals selected for inclusion in the CJR program (e.g., utilization rates for knee replacement and hip replacement, teaching status, proportion of Medicaid patients served, bed size). Second, in this analysis, we did not include several provisions that are included in the CJR program (e.g., stop-loss mechanism, quality floor). While such specifications may impact the absolute dollars that are transferred between CMS and the CJR hospitals, we do not believe that the inclusion of these provisions would substantially change our primary findings related to risk adjustment. Finally, our risk adjustment model did not include other important variables for joint replacement (e.g., body mass index, procedure type, functional status). However, we deliberately used a risk-adjustment model that has a low administrative burden and is already being used by CMS for several existing programs.

RESULTS

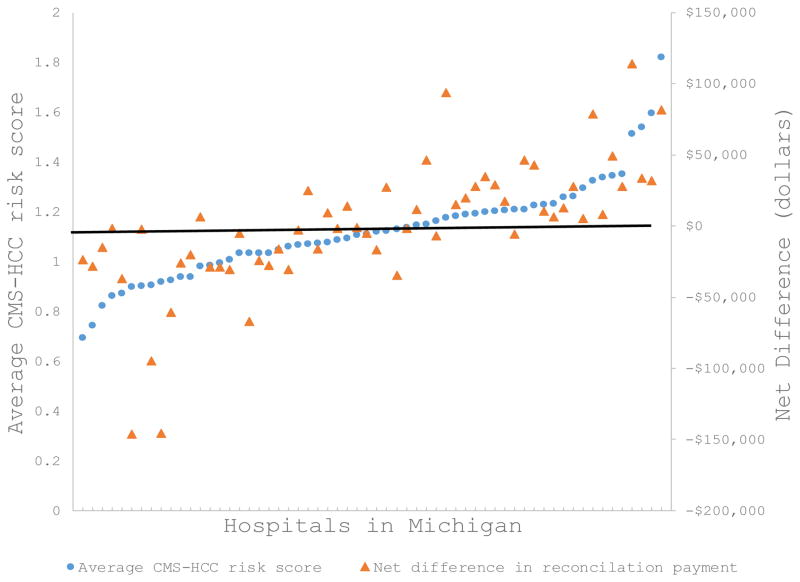

We identified 23,251 Medicare beneficiaries who underwent lower extremity joint replacement procedures (i.e., DRG 469 and 470) in 60 Michigan hospitals from 2011 through 2013. The average CMS-HCC risk score for individual hospitals varied from 0.7 to 1.8 (mean: 1.12, standard deviation: 0.19) (Exhibit 1). This variation was greater for patients within MS-DRG 469 (Supplemental Exhibit 1).

EXHIBIT 1.

Figure shows statewide variation in patient complexity. If risk-adjustment is implemented in the CJR model, hospitals that treat medically complex patients will receive additional reimbursement from CMS

SOURCE: Authors’ analysis of data from the Medicare Research Identifiable Files, 2011–2013

NOTES: Each marker represents a hospital in Michigan. CMS-HCC risk scores reflect the medical complexity of the hospital’s patient population and incorporate age, gender, comorbidity, and dual eligible status and original reason for Medicare entitlement. Net difference is calculated by subtracting risk-adjusted reconciliation payments from unadjusted reconciliation payments. A negative net difference means that the hospital would expect a reduction in reconciliation payments with risk adjustment. Regional target prices were used to calculate reconciliation payments.

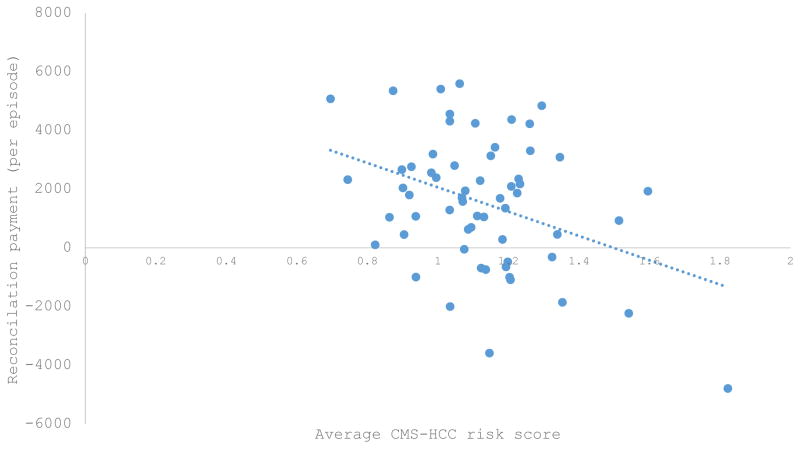

In Scenario 1, we identified no significant association between reconciliation payments and CMS-HCC risk scores when target episode prices were set using hospital historical spending (r=−0.15, p=0.24). This finding reflects the relative year-over-year consistency of patient complexity within hospitals. In contrast, for Scenario 2, there was a statistically significant, inverse association between reconciliation payments and CMS-HCC risk scores when target prices were set to a regional benchmark (r= −0.37, p=0.003) (Exhibit 2). Specifically, for each standard deviation increase in CMS-HCC risk score, reconciliation payments per joint episode were reduced by $827 (95% CI, −$1,368 to −$285). This estimate remained stable and significant after adjusting for teaching status, number of beds, and proportion of Medicaid patients served by the hospital.

EXHIBIT 2.

Reconciliations payments are significantly associated with average CMS-HCC risk scores when a regional benchmark is used

SOURCE: Authors’ analysis of data from the Medicare Research Identifiable Files, 2011–2013

NOTES: Each marker represents a hospital in Michigan. Each hospital’s reconciliation payment represents the difference between target episode spending and actual episode spending divided by the total number of joint replacements performed. A negative reconciliation payment means the hospital must repay Medicare.

We found that risk adjustment consistently reduced reconciliation payments to hospitals with the lowest CMS-HCC risk scores, and consistently increased reconciliation payments to hospitals with the highest risk scores (Exhibit 1). In aggregate, the inclusion of CMS-HCC risk scores in the calculation of reconciliation payments would lead to reductions in annual reconciliation payments by as much as $146,360 for hospitals with the least medically complex patients, and gains as large as $114,184 for hospitals with the most medically complex patients. Our sensitivity analyses identified no substantive changes in our primary findings.

DISCUSSION

Using methods analogous to those utilized by the CJR program, we found that region-based target pricing led to reduced reconciliation payments to hospitals that treat medically complex patients. In addition, we found that, after risk adjustment with CMS-HCC risk scores, estimated reconciliation payments were substantially increased for hospitals that treat high complexity patients and reduced for hospitals that treat low complexity patients. The magnitude of these gains was similar to the incentive payments received by hospitals through CMS’ Hospital Value-Based Purchasing program.7 Collectively, these findings suggest that risk adjustment is important for bundled payment programs that utilize regional spending benchmarks, including the CJR model.

Our primary finding that patient complexity is associated with the magnitude and direction (i.e., bonus versus penalty) of hospital reconciliation payments is consistent with numerous studies showing that underlying clinical factors influence episode payments for multiple conditions.8–11 In fact, many published risk-adjustment models for joint replacement include even more risk-adjustment variables such as anesthesia class and functional status.12,13 While the current study used only age, gender, comorbidity, and dual eligible status and original reason for Medicare entitlement to assess risk, our results imply that even a modest risk-adjustment model would have important implications for reconciliation payments received by hospitals when target prices are based on regional benchmarks.

Our results have several immediate implications for policymakers. Our finding that risk-adjustment of the target price will have a significant impact on reconciliation payments suggests that CMS should strongly consider amending the current CJR target pricing strategy to account for participating hospital’s patient population during the second performance year of CJR (i.e., the year when hospitals begin to face penalties). At present, CMS sets a different target price for each of the following cohorts: 1) MS-DRG 469 with hip fracture; 2) MS-DRG 469 without hip fracture; 3) MS-DRG 470 with hip fracture; 4) MS-DRG 470 without hip fracture. Our results suggest that CMS should further refine cohort-specific target prices at each hospital by accounting for key patient characteristics that impact determinants of episode payments, including complications, readmissions, and utilization of post-acute care services. Such additional risk-adjustment will raise the target price for hospitals that serve older, sicker and more medically complex patients and lower the target price for hospitals that treat predominantly younger and/or healthier populations. This methodological refinement is essential because target prices–and the corresponding reconciliation payments–are increasingly anchored to regional payment data during the latter years of the program.

In this study, we used CMS-HCC risk scores to refine target prices. We selected this particular measure for three reasons. First, HCCs are used by CMS for risk adjustment in a number of other performance programs, including programs that are focused on joint replacement and episode payments (e.g., Medicare Spending Per Beneficiary, Hospital Compare measures, Hospital Readmission Reduction Program). Second, HCCs can be obtained from administrative claims with minimal burden. Third, many of the factors that make up the CMS-HCC risk score (i.e., age, gender, comorbidity, and dual eligible status and original reason for Medicare entitlement) have been independently shown to impact expenditures. In addition to HCCs, CMS should consider other important risk adjustment variables such as socioeconomic status, marital status, body mass index and functional status. While CMS may need to devote resources to identifying and validating specific variables that adequately account for patient characteristics, our findings suggest that without sufficient risk adjustment, hospitals will be financially penalized for treating medically complex patient populations.

There are several reasons why our findings support this position. First, the difference between risk-adjusted and unadjusted payments can be significant for some hospitals. In fact, the magnitude of the annual additional payment or penalty is similar to the amount currently received by hospitals through Hospital Value-Based Purchasing. Second, if CMS continues to use regional targets as it expands bundled payment programs to include other conditions,14 the effect of not adjusting for medical comorbidities will likely be compounded for some hospitals. Because a hospital’s patient population is often determined by its fixed geographic and structural characteristics, hospitals that are disadvantaged by the CJR model will likely be disadvantaged by future bundled payment programs that do not incorporate risk-adjustment. Third, CMS is already using HCC based risk-adjustment for several of its episode-based payment metrics (e.g., Medicare Spending Per Beneficiary, Hospital Compare 30-day Payment Measure for Joint Replacement). It is not clear why this should be different for CJR, especially with the findings reported herein. Fourth, as evidenced by comments from key stakeholders during the rulemaking process, patient level risk adjustment is strongly supported by clinicians, hospital administrators and many other organizations (e.g., Medicare Payment Advisory Commission). Finally, the absence of risk adjustment in the CJR program may lead to unintended consequences such as reduced access to necessary surgical and/or post-acute care for beneficiaries with chronic disease. For example, providers that have established gainsharing agreements or contracts with CJR participant hospitals may decline to care for patients that have predicted expenditures that exceed the hospital’s unadjusted target price. By closely aligning reimbursement and predicted expenditures, CMS may partially mitigate patient selection concerns in the CJR program.

This analysis suggests that CMS-HCC based risk-adjustment impacts reconciliation payments when target prices are regionalized. Moving forward, research in this area should focus on defining risk-adjustment variables beyond the CMS-HCC model that are predictive of episode cost, reflect underlying severity of illness of the patient, and can be relatively easily obtained from administrative claims. For this purpose, clinical registry data may be an option if it can be linked to Medicare claims.15–17 Clinical registry data often have robust risk adjustment variables that are not available from administrative claims. The trade-off is, however, that these data are labor-intensive and expensive to obtain. For example, in 2011 Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan funded and established the Michigan Arthroplasty Registry Collaborative Quality Initiative (MARCQI). MARCQI is a statewide quality collaborative established to improve care of patients undergoing joint replacement.15 The MARCQI data registry includes information on clinical indications for surgery, procedure details, surgical approach, and specific complications that may not be identifiable from billing data.

In the end, the goal of any alternative payment model should be to provide hospitals with realistic incentives to promote high-quality care and reduce costs. While we believe that the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement model could serve as an important step in that direction, the inclusion of CMS-HCC based risk adjustment would make the program more equitable and acceptable for all participants and limit potential unintended consequences for Medicare beneficiaries with multiple comorbid conditions.

References

- 1.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Program: Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement payment model for acute care hospitals furnishing lower extremity joint replacement services. Federal Register. 2015 Nov 24; Available at: https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2015/11/24/2015-29438/medicare-program-comprehensive-care-for-joint-replacement-payment-model-for-acute-care-hospitals. [PubMed]

- 2.Mechanic RE. Mandatory Medicare Bundled Payment — Is It Ready for Prime Time? N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1291–1293. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1509155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller DC, Gust C, Dimick JB, et al. Large variations in Medicare payments for surgery highlight savings potential from bundled payment programs. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:2107–15. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pope GC, Kautter J, Ellis RP, et al. Risk adjustment of Medicare capitation payments using the CMS-HCC model. [accessed September 1, 2014];Health Care Financ Rev. 2004 25:119–41. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15493448. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.QualityNet. [accessed January 15, 2016]; Available at: http://www.qualitynet.org/dcs/ContentServer?c=Page&pagename=QnetPublic%2FPage%2FQnetTier4&cid=1228774267858.

- 6.Shahian DM, Normand S-LT. Comparison of “risk-adjusted” hospital outcomes. Circulation. 2008;117:1955–63. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.747873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Werner RM, Dudley A. Medicare’s new hospital value-based purchasing program is likely to have only a small impact on hospital payments. Health Aff. 2012;31:1932–1940. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abdelsattar ZM, Birkmeyer JD, Wong SL. Variation in Medicare Payments for Colorectal Cancer Surgery. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:391–5. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.004036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schoenfeld AJ, Harris MB, Liu H, et al. Variations in Medicare payments for episodes of spine surgery. Spine J. 2014;14:2793–8. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cram P, Ravi B, Vaughan-Sarrazin MS, et al. What Drives Variation in Episode-of-care Payments for Primary TKA? An Analysis of Medicare Administrative Data. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:3337–47. doi: 10.1007/s11999-015-4445-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Y, Lu X, Wolf BR, et al. Variation of Medicare payments for total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28:1513–20. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schilling PL, Bozic KJ. Development and Validation of Perioperative Risk-Adjustment Models for Hip Fracture Repair, Total Hip Arthroplasty, and Total Knee Arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98:e2. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.01330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.SooHoo NF, Li Z, Chan V, et al. The Importance of Risk Adjustment in Reporting Total Joint Arthroplasty Outcomes. J Arthroplasty. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burwell SM. Setting value-based payment goals--HHS efforts to improve U.S. health care. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:897–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1500445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Markel DC, Allen MW, Zappa NM. Can an Arthroplasty Registry Help Decrease Transfusions in Primary Total Joint Replacement? A Quality Initiative. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474:126–31. doi: 10.1007/s11999-015-4470-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Franklin PD, Lewallen D, Bozic K, et al. Implementation of patient-reported outcome measures in U.S. Total joint replacement registries: rationale, status, and plans. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(Suppl 1):104–9. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.00328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maradit Kremers H, Lewallen LW, Lahr BD, et al. Do claims-based comorbidities adequately capture case mix for surgical site infections? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:1777–86. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-4083-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]