Abstract

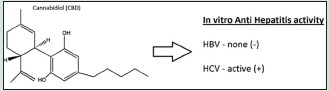

Viral hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C (HCV) pose a major health problem globally and if untreated, both viruses lead to severe liver damage resulting in liver cirrhosis and cancer. While HBV has a vaccine, HCV has none at the moment. The risk of drug resistance, combined with the high cost of current therapies, makes it a necessity for cost-effective therapeutics to be discovered and developed. The recent surge in interest in Medical Cannabis has led to interest in evaluating and validating the therapeutic potentials of Cannabis and its metabolites against various diseases including viruses. Preliminary screening of cannabidiol (CBD) revealed that CBD is active against HCV but not against HBV in vitro. CBD inhibited HCV replication by 86.4% at a single concentration of 10 μM with EC50 of 3.163 μM in a dose-response assay. These findings suggest that CBD could be further developed and used therapeutically against HCV.

SUMMARY

Cannabidiol exhibited in vitro activity against viral hepatitis C.

Abbreviations Used: CB2: Cannabis receptor 2, CBD: Cannabidiol, DNA: Deoxyribonucleic acid, HBV: Hepatitis B virus, HCV: Hepatitis C virus, HIV/AIDS: Human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome, HSC: Hepatic stellate cells, MTS: 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2Htetrazolium, PCR: Polymerase chain reaction

Key words: Cannabis, hemp, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, cannabidiol

INTRODUCTION

Viral hepatitis is caused by a group of viruses divided into five types (A, B, C, D, and E), and they are primarily known to attach to the liver.[1] Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) are the most dangerous and prevalent of the five virus types.[2,3] Chronic cases of HBV as well as HCV are among the leading causes of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in the world.[4] HBV and HCV infections are also implicated in the development of other diseases including lymphoma, diabetes, and atherosclerosis.[5,6] HBV is the most prevalent type worldwide and the leading cause of HCC in some countries, especially in Asia.[7] Despite the fact that great strides have been made in the treatment and prevention of HBV and HCV, the global burden remains a major health problem. There is as such a great need to continue to search for new molecules with activity against hepatitis viruses.

Cannabidiol (CBD) is a nonpsychoactive cannabinoid found in the Cannabis plants and is credited for several pharmacological properties. It is also known to have beneficial effects against inflammation/pain, neurological conditions, cancer, and other ailments.[8,9,10,11] The current surge in the interest in medical Cannabis has rekindled research to validate the medicinal properties of this molecule, especially given that it is nonpsychoactive compared to its close derivative tetrahydrocannabinol. While most of the studies on CBD and Cannabis, in general, have focused on the neuroprotective as well as anti-inflammatory properties, little is known about the antiviral activity of Cannabis and its CBDs. A search of the current literature did not reveal any report on the antiviral activity of Cannabis molecules against the hepatitis virus. In general, with regard to antiviral activity, medical Cannabis was reported to be used as an accompanying remedy by HIV/AIDS patients to alleviate neuropathic pain, wasting, nausea, and vomiting.[12,13,14] Other studies have focused on the effects of Cannabis use on patients undergoing treatment for HCV with mixed results.[15,16] Given the increasing use and application of medical Cannabis along with its nonpsychoactive metabolite (CBD), and in line with our continuous effort to evaluate and validate the potential therapeutic properties of CBD, the major aim of this study was as such to evaluate the anti-HBV and anti-HCV activities of CBD in vitro.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cannabidiol

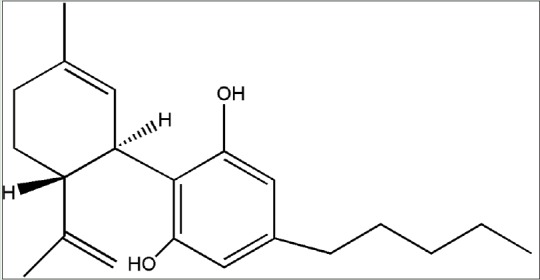

Research grade CBD (Item No.: C-045) [Figure 1] was purchased from Cerilliant Reference Standards (www.cerilliant.com).

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of cannabidiol

Anti-hepatitis B assay

The anti-HBV assay was performed as previously described[17,18] with modifications to use in real time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (TaqMan) to measure extracellular HBV DNA copy number associated with virions released from HepG2 2.2.15 cells. The HepG2 2.2.15 cell line is a stable cell line producing high levels of the wild-type ayw1 strain of HBV. Antiviral compounds blocking any later step of viral replication such as transcription, translation, pregenome encapsidation, reverse transcription, particle assembly, and release can be identified and characterized using this cell line.

In brief, HepG2 2.2.15 cells are plated in 96-well microtiter plates. Only the interior wells were utilized to reduce “edge effects” observed during cell culture; the exterior wells were filled with complete medium to help minimize sample evaporation. After incubation with 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C for 16–24 h, the confluent monolayer of HepG2 2.2.15 cells was washed and the medium was replaced with complete medium containing test compounds at a single concentration of 10 µM. Three days later, the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium and test compounds at a single concentration of 10 µM. Six days following the initial administration of the test compounds, the cell culture supernatant was collected, treated with pronase and DNAse, and then used in a real-time quantitative TaqMan PCR assay. Antiviral activity was determined by calculating the reduction in HBV DNA levels compared to untreated virus control samples. Compound cytotoxicity was determined using MTS (CellTiter 96 Reagent, Promega) to measure cell viability as described above.

Anti-hepatitis C assay

The anti-HCV activity was carried out according to previously reported procedures.[19,20] Huh7.5 cells (HD Biosciences) were grown in Dulbecco's modified eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin-streptomycin (pen-strep), and 1% nonessential amino acids. Cells were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Huh7.5 cells were seeded at 1 × 104 cells/well into 96-well plates. Test compounds were serially diluted with DMEM plus 5% FBS. The diluted compound in the amount of 50 μl was mixed with an equal volume of cell culture-derived HCV (HCVcc), and then applied to appropriate wells in the plate. Human recombinant interferon alpha-2b was included as a positive control compound. After incubation at 37°C for 72 h, the cells were lysed, and luciferase activity was measured using Renilla Luciferase Assay System (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instruction. The number of cells in each well was determined by CytoTox-1 reagent (Promega). CBD was first tested at a single concentration of 10 µM in triplicate to derive percentage inhibition of HCVcc. Based on the activity of the single dose, a dose-response assay was carried out to determine the IC50. Sofosbuvir was used as a positive control.

Statistical analysis

Experiments were carried out in duplicate, and results were given as the mean of the two experiments. The data in all the experiments were analyzed using Microsoft Excel.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

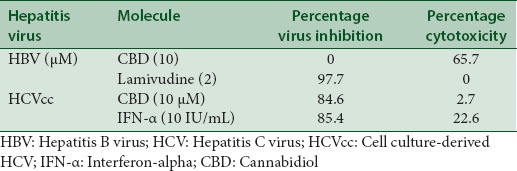

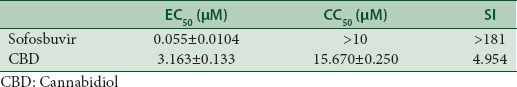

The bioactivity of CBD against HBV and HCV is shown in Tables 1 and 2. CBD inhibited HCV replication by 86.4% at a single concentration of 10 µM. The compound was not active against the HBV virus in vitro but exhibited a significant cytotoxicity against HepG2 2.2.15 cells which were used to culture the virus. In the HCV assay, CBD inhibited the virus with minimal toxicity against the Huh7.5 cells that were used to culture the virus. Lamivudine and interferon alpha were used as positive controls against HBV and HCV, respectively, and they significantly inhibited viral replication at the single-dose assay. CBD was found to exhibit a dose-dependent inhibition of the HCV virus in the dose-response assay [Table 2].

Table 1.

Inhibitory effect of cannabidiol against viral hepatitis B and C at a single dose of 10 (μM)

Table 2.

Determination of EC50 and CC50 of cannabidiol against hepatitis C virus

The direct antiviral activity of CBD against the HCV indicates that the molecule has an effect against both the viral and nonviral hepatitis, otherwise known as autoimmune hepatitis. Autoimmune hepatitis is an inflammatory liver condition elicited by activated T-cells and macrophages. Studies have shown that CBD by interacting with the CB2 receptor induces apoptosis in thymocytes and splenocytes inhibiting the proliferation of T-cells and macrophages which are responsible for either attacking liver cells or inducing the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines that cause autoimmune hepatitis in the liver.[21,22,23] CB2 receptors are expressed in immune and immune-derived cells and their activation is known to influence viral infections by altering host immune response, particularly inflammation.[21] CB2 receptor activation is as such known to suppress inflammation and modulate immune responses to viral infection.[24,25] Host inflammation is also said to be able to drive the progression of HBV and other viral infections where host inflammation is pathogenic and activation of the CB2 would as such be useful in the control of the HBV virus infection since it results in an anti-inflammatory effect.[26] The benefit of CBD in alleviating liver fibrosis, which is one of the outcomes of untreated viral hepatitis, was also demonstrated in previous studies.[27] The studies revealed that one of the most critical cellular events in the development and progression of liver fibrosis is the activation of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), and CBD was shown to induce apoptosis in activated HSCs by interaction with the endoplasmic reticulum.[27]

CONCLUSION

We report here for the first time in vitro studies to demonstrate the antiviral activity of CBD against HCV. CBD was shown to have activity against HCV in vitro but not against HBV. A review of the literature seems to suggest that CBD may also have activity in vivo based on its interaction with the CB2 receptor and as such using a host mechanism to indirectly slow the pathogenic process of the HBV virus. Based on these findings, CBD as such has potential to be further developed as a treatment for viral hepatitis, especially as a combination therapy with the currently existing therapies. Further studies are in progress to further validate and assess the activity in vivo.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was supported in part financially by Medicanja Jamaica Ltd., and Flavocure Biotech LLC.

Conflicts of interest

Authors Henry Lowe and Ngeh Toyang are on the management of Medicanja Jamaica Ltd., and Flavocure Biotech LLC.

ABOUT AUTHOR

Dr. Henry I.C. Lowe

Dr. Henry Lowe is a specialist in medicinal chemistry with over 50 years of experience in the field. Dr. Lowe holds a PhD from Manchester University, UK, a M.Sc. from the University of Sydney, Australia and B.Sc. (Hons) from UCWI, London University. He holds several postdoctoral studies including but not limited from; Harvard University and M.I.T, USA. Dr. Lowe is currently an adjunct Professor at the University of Maryland School of Medicine as well as the founder of three biotech companies and the Bio-Tech R&D Institute, Kingston Jamaica, all focusing on drug discovery and development.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the support of the staff of Bio-Tech R & D, Medicanja Jamaica Ltd., and Flavocure Biotech LLC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alter MJ, Mast EE. The epidemiology of viral hepatitis in the United States. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1994;23:437–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lemoine M, Eholié S, Lacombe K. Reducing the neglected burden of viral hepatitis in Africa: Strategies for a global approach. J Hepatol. 2015;62:469–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ott JJ, Stevens GA, Groeger J, Wiersma ST. Global epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection: New estimates of age-specific HBsAg seroprevalence and endemicity. Vaccine. 2012;30:2212–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tornesello ML, Buonaguro L, Izzo F, Buonaguro FM. Molecular alterations in hepatocellular carcinoma associated with hepatitis B and hepatitis C infections. Oncotarget. 2016;7:25087–102. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang YW, Yang SS, Fu SC, Wang TC, Hsu CK, Chen DS, et al. Increased risk of cirrhosis and its decompensation in chronic hepatitis C patients with new-onset diabetes: A nationwide cohort study. Hepatology. 2014;60:807–14. doi: 10.1002/hep.27212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Younossi ZM, Park H, Saab S, Ahmed A, Dieterich D, Gordon SC. Cost-effectiveness of all-oral ledipasvir/sofosbuvir regimens in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:544–63. doi: 10.1111/apt.13081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lavanchy D. Worldwide epidemiology of HBV infection, disease burden, and vaccine prevention. J Clin Virol. 2005;34(Suppl 1):S1–3. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(05)00384-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campos AC, Fogaça MV, Sonego AB, Guimarães FS. Cannabidiol, neuroprotection and neuropsychiatric disorders. Pharmacol Res. 2016;112:119–27. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernández-Ruiz J, Sagredo O, Pazos MR, García C, Pertwee R, Mechoulam R, et al. Cannabidiol for neurodegenerative disorders: Important new clinical applications for this phytocannabinoid? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;75:323–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04341.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mechoulam R, Peters M, Murillo-Rodriguez E, Hanus LO. Cannabidiol – recent advances. Chem Biodivers. 2007;4:1678–92. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200790147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McPartland JM, Russo EB. Cannabis and Cannabis extracts: Greater than the sum of their parts? J Cannabis Ther. 2001;1:103–32. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sidney S. Marijuana use in HIV-positive and AIDS patients: Results of an anonymous mail survey. J Cannabis Ther. 2001;1:35–41. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prentiss D, Power R, Balmas G, Tzuang G, Israelski DM. Patterns of marijuana use among patients with HIV/AIDS followed in a public health care setting. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;35:38–45. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200401010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mukhtar M, Arshad M, Ahmad M, Pomerantz RJ, Wigdahl B, Parveen Z. Antiviral potentials of medicinal plants. Virus Res. 2008;131:111–20. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sylvestre DL, Clements BJ, Malibu Y. Cannabis use improves retention and virological outcomes in patients treated for hepatitis C. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:1057–63. doi: 10.1097/01.meg.0000216934.22114.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishida JH, Peters MG, Jin C, Louie K, Tan V, Bacchetti P, et al. Influence of Cannabis use on severity of hepatitis C disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Korba BE, Gerin JL. Use of a standardized cell culture assay to assess activities of nucleoside analogs against hepatitis B virus replication. Antiviral Res. 1992;19:55–70. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(92)90056-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Korba BE, Milman G. A cell culture assay for compounds which inhibit hepatitis B virus replication. Antiviral Res. 1991;15:217–28. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(91)90068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buckwold VE, Wei J, Huang Z, Huang C, Nalca A, Wells J, et al. Antiviral activity of CHO-SS cell-derived human omega interferon and other human interferons against HCV RNA replicons and related viruses. Antiviral Res. 2007;73:118–25. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lowe HI, Toyang NJ, Roy S, Watson CT, Bryant JL. Inhibition of the human hepatitis C virus by dibenzyl trisulfide from Petiveria alliacea L (Guinea Hen Weed) Br Microbiol Res J. 2015;12:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tahamtan A, Tavakoli-Yaraki M, Rygiel TP, Mokhtari-Azad T, Salimi V. Effects of cannabinoids and their receptors on viral infections. J Med Virol. 2016;88:1–12. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rieder SA, Chauhan A, Singh U, Nagarkatti M, Nagarkatti P. Cannabinoid-induced apoptosis in immune cells as a pathway to immunosuppression. Immunobiology. 2010;215:598–605. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagarkatti PS, Nagarkatti M. Use of Cannabidiol in the Treatment of Autoimmune Hepatitis. 2012. [Last cited 2013 Sep 07]. Available from: http://www.google.com/patents/US8242178 .

- 24.Correa F, Mestre L, Docagne F, Guaza C. Activation of cannabinoid CB2 receptor negatively regulates IL-12p40 production in murine macrophages: role of IL-10 and ERK1/2 kinase signaling. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;145:441–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rom S, Persidsky Y. Cannabinoid receptor 2: Potential role in immunomodulation and neuroinflammation. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2013;8:608–20. doi: 10.1007/s11481-013-9445-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reiss CS. Cannabinoids and viral infections. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2010;3:1873–86. doi: 10.3390/ph3061873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lim MP, Devi LA, Rozenfeld R. Cannabidiol causes activated hepatic stellate cell death through a mechanism of endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2011;2:e170. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2011.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]