Abstract

Background:

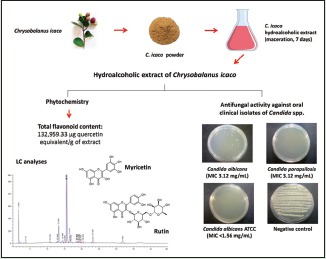

Chrysobalanus icaco is a medicinal plant commonly used to treat fungal infections in Brazilian Amazonian region.

Objective:

This work aimed to evaluate the antifungal activity of the hydroalcoholic extract of C. icaco (HECi) against oral clinical isolates of Candida spp. and to determine the pharmacognostic parameters of the herbal drug and the phytochemical characteristics of HECi.

Materials and Methods:

The pharmacognostic characterization was performed using pharmacopoeial techniques. Phytochemical screening, total flavonoid content, and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis were used to investigate the chemical composition of the HECi. A broth microdilution method was used to determine the antifungal activity of the extract against 11 oral clinical isolates of Candida spp.

Results:

Herbal drug presented parameters which were within the limits set forth in current Brazilian legislation. A high amount of flavonoid content (132,959.33 ± 12,598.23 μg quercetin equivalent/g of extract) was found in HECi. Flavonoids such as myricetin and rutin were detected in the extract by HPLC analyses. HECi showed antifungal activity against oral isolates of Candida albicans and Candida parapsilosis (minimum inhibitory concentrations [MIC] 3.12 and 6.25 mg/mL, respectively), and C. albicans American American Type Culture Collection (MIC <1.56 mg/mL).

Conclusion:

HECi was shown to possess antifungal activity against Candida species with clinical importance in the development of oral candidiasis, and these activities may be related to its chemical composition. The antifungal activity detected for C. icaco against Candida species with clinical importance in the development of oral candidiasis can be attributed to the presence of flavonoids in HECi, characterized by chromatographic and spectroscopic techniques.

SUMMARY

Chrysobalanus icaco presents a high amount of flavonoids in its constitution

LC analysis was able to identify the flavonoids myricetin and rutin in C. icaco hydroalcoholic extract

The C. icaco hydroalcoholic extract inhibits the growth of oral clinical isolates of Candida spp. and Candida albicans American Type Culture Collection.

Abbreviations Used: HECi: Hydroalcoholic extract of C. icaco; HPLC: High performance liquid chromatography; AlCl3: Aluminum chloride; DMSO: Dimethyl sulfoxide; CH3NOONa: Sodium acetate; MTT: 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide; ATCC: American Type Culture Collection; EMBRAPA: Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation – Eastern Amazon; v/v: Volume per volume; SD: Standard deviation; TFC: Total flavonoid content; w/v: Weight per volume; ELSD: Evaporative light scattering detector; DAD: Diode-arrange detector; UFPA: Federal University of Pará; IEC: Evandro Chagas Institute; INCQS-FIOCRUZ: National Institute of Quality Control in Health – Fundação Oswaldo Cruz; SDA: Sabouraud Dextrose Agar; CFU: Colony-forming units; MIC: Minimum inhibitory concentrations; MFC: Minimum fungicidal concentrations

Key words: Antifungal activity, Candida spp., Chrysobalanus icaco, flavonoids, myricetin, rutin

INTRODUCTION

Candidiasis is currently considered one of the most common fungal infections that affect humans. This disease is caused by saprophytic Candida spp. yeasts that inhabit the oral mucosa of healthy individuals.[1] However, factors such as immunosuppression, long-term use of broad-spectrum antibiotics and xerostomia may trigger to a alteration in host homeostasis, and consequently the development of pathogenic forms of the fungus.[2]

Topical and systemic antifungal agents of the polyene or azole family are commonly used to the management of oral candidiasis.[3,4] Although the treatment with these antifungal drugs presents relative effectiveness, most of them can cause undesirable side effects such as gastrointestinal disorders, hepatotoxicity, hair loss, visual disturbances, among others, and also the emergence of drug-resistant strains of Candida spp.[5]

Chrysobalanus icaco L. (Chrysobalanaceae) is a shrub largely used in folk traditional phytotherapy to treat fungal infections in the Amazonian region.[6] This medicinal plant occurs naturally in South Florida, Caribbean, Central America, Northwestern of South America, and tropical West Africa.[7] Phytochemical studies have revealed the presence of flavonoids, including quercetin, myricetin, and its derivatives in a hydroalcoholic extract of leaves.[8] Stigmasterol, sitosterol, campesterol, pomolic acid, and a kaempferol derivative were identified in a hexane extract of leaves and their fractions.[9] Anthocyanins and terpenes were also found in C. icaco extracts.[10,11]

Regarding their biological properties, C. icaco possess anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, analgesic, antidiabetic, and anticancer activities;[11,12] beyond prevent fat gain in obese high-fat fed mice.[13] Although the antimicrobial activity of this plant has been previously reported, there are no data about the effect of C. icaco against oral clinical isolates of Candida spp., often related to the emergence of fungal infections in the oral cavity. Thus, the aim of this work was to evaluate the in vitro antifungal activity of C. icaco against clinical isolates of Candida spp. and to determine the phytochemical profile of hydroalcoholic extract of C. icaco (HECi) by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and the pharmacognostic parameters of the herbal drug.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and reagents

Acetonitrile (Fluka, USA), methanol (Tedia Company Inc., USA), formic acid (Vetec, Duque de Caxias, Brazil), aluminum chloride (AlCl3), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), ethanol (Synth, Brazil), sodium acetate (J.T. Baker, Mexico), nystatin, chloramphenicol, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), quercetin, myricetin, and rutin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The mediums Sabouraud Dextrose Agar (SDA), Mueller-Hinton agar, and Mueller-Hinton broth were purchased from Himedia Laboratories (Mumbai, India).

Plant material and herbal drug preparation

C. icaco leaves (2.3 kg) were collected in Salinópolis, Northeast Pará, Brazil (0°36'1,76” S/47°18'11,70” W) in October 2010. A voucher specimen was prepared and identified by a specialist of the Herbarium of the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation – Eastern Amazon (EMBRAPA) and registered under the number: NID 40/2011. After collection, the leaves were washed with tap water, cleaned with a hydroalcoholic solution (70%, v/v), air-dried for 5 days and subsequently in an air-forced oven (~40°C) for 2 days. C. icaco dried leaves (1.16 kg) were then ground in a knife mill.

Pharmacognostic characterization of Chrysobalanus icaco herbal drug

To characterize the herbal drug obtained from C. icaco leaves, the following determinations were performed: Granulometric analysis, foaming index, loss on drying, total ash and acid-insoluble ash contents, bulk density, apparent relative density, and content of extractable matter.[14,15] All the experiments were carried out in triplicate, and the results are expressed as a mean ± standard deviation.

Extraction procedure

The herbal drug of C. icaco (200 g) was successively extracted by maceration with a hydroethanolic mixture (70%, v/v) for 7 days. Then, both the extracts were filtered, combined, and evaporated under reduced pressure (40°C, 167 mbar, and 120 rpm) to provide 32.49 g of crude HECi, whose yield was 16.24% and 8.19% in relation to the herbal drug and fresh plant, respectively.

Preliminary phytochemical screening

Qualitative tests were performed in HECi to detect the following metabolic classes: Reducer sugars, alkaloids, carotenoids, coumarin, depside and depsidone, steroids and triterpenoids, tannins, flavonoids, cardiac glycosides, proteins and amino acids, saponin, and sesquiterpene lactones.[16]

Total flavonoid content

Total flavonoid content (TFC) was determined using aluminum complexation reaction as described by Pękal and Pyrzynska.[17] In brief, 0.5 mL of an AlCl3 solution (2%, w/v) was added to 1 mL of HECi dissolved in methanol (2.5 mg/mL) and subsequently 0.5 mL of CH3 COONa solution (1M) was added. The resulting mixture was vigorously shaken and was allowed to react for 10 min at room temperature. After incubation, the absorbance was measured at 425 nm. A blank solution consisted in the above-mentioned mixture where distilled water replaces the same volume of AlCl3. The TFC was calculated using a calibration curve of quercetin (the linearity range: 0.07–1.17 µg/mL, equation: y = 0.4944x − 0.002, R2 = 0.9958) and expressed as µg quercetin equivalents/g of HECi. All determinations were carried out in triplicate.

High-performance liquid chromatography analysis of hydroalcoholic extract of Chrysobalanus icaco

Chromatographic analyses were performed in the Laboratory of Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry Faculty of Pharmacy, UFPA (Belém, Pará, Brazil) using an Agilent Technologies 1260 HPLC chromatograph (Agilent, USA) coupled to an evaporative light scattering detector (Agilent, USA) and a diode-arrange detector (Agilent, USA) working between 190 and 400 nm with monitoring at 260 nm. The ELSD detector was warmed up for 30 min before each run, using as evaporation and nebulization temperatures, 85°C and 40°C, respectively, and an optimum flow rate of 1.6 L/min nitrogen, 99.99%, as nebulizing gas. A Zorbax Eclipse XDB C18 (150 mm × 4.6 mm × 5 μm) column used was maintained at 26°C. Acetonitrile (a) and aqueous formic acid, pH 3 (b) composed the mobile phase in the following gradient: 5%–15% A (0–5 min), 15%–25% A (5–25 min), isocratic at 25% A (25–40 min), and 25%–5% A (40–45 min), which was pumped at a flow of 1.0 mL/min. The injection volume was 20 μL. Data were produced and processed using Open Lab software on a HP Z220 computer.

In vitro antifungal activity

Obtaining clinical isolates of oral cavity

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of UFPA (CAAE 0051.0.073.000-11, Registry 060/11 CEP-ICS/UFPA). Clinical isolates were collected from oral cavity of healthy patients (both sexes between 18 and 59 years old, nondiabetics, nonimmunosuppressed, nonusers of antibiotics and/or immunosuppressive drugs, and nondrug-abusing) undergoing dental clinical treatment at the Faculty of Dentistry, UFPA (Belém, Pará, Brazil), with the help of a sterile swab as described previously.[18] A total of 11 Candida spp. clinical isolates were obtained and subsequently identified in the Evandro Chagas Institute (IEC/Brazil), as Candida albicans (n = 4), Candida parapsilosis (n = 5), Candida dubliniensis (n = 1), and Candida tropicalis (n = 1). A C. albicans American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) 40175 strain obtained from the National Institute of Quality Control in Health – Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (INCQS–FIOCRUZ) was used as a control. Both clinical isolates and ATCC strain were maintained on SDA medium supplemented with 0.02% chloramphenicol at room temperature (25°C). These fungi were subcultured again on SDA every month in the Laboratory of Microbiology, Faculty of Pharmacy, UFPA (Belém, Pará, Brazil) for 24 h at 35°–37°C before preparation of the inoculums.

Antifungal activity of hydroalcoholic extract of Chrysobalanus icaco

Antifungal activity of the HECi against oral clinical isolates of Candida spp. was determined by broth microdilution method according to protocol M27-A3 of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, with minor modifications by de Quadros et al.[19,20] To obtain the inoculums, 3–4 colonies of each species of Candida spp. measuring ~1 mm, previously subcultured in ASD medium and incubated for 24 h at 25°C, were suspended in sterile saline (2 mL). The suspension was vigorously homogenized by vortex, and then cell turbidity was adjusted to 0.5 McFarland scale, which corresponds to 1.5 × 106 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL. The resulting suspension obtained was then diluted in Mueller-Hinton broth to achieve the final concentration of 1 × 103 CFU/mL.

The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) were determined using MTT colorimetric assay. The MIC is defined as the lowest concentration of an extract to which the microorganism does not demonstrate visible growth by the MTT dye. For the microdilution test, the inoculums (100 μL) containing 1 × 103 CFU/mL were added to each well of a 96-well polystyrene plate, and 100 μL of HECi diluted at final concentrations of 6.25, 3.12, 1.56, 0.79, 0.38, and 0.19 mg/mL in DMSO 10% were added into consecutive wells. After 24 h incubation at 37°C, 20 μL of MTT (5 mg/mL), a tetrazolium salt that is reduced by metabolically active cells to a colored water-soluble formazan derivative, was added to the wells to allow visual identification of metabolic activity.[21] The final concentration of MTT after inoculation was 0.005% (w/v). After incubation, growth was indicated by the development of a blue color. The MIC was read as the lowest concentration of the extract at which a change in color occurred.

To determine the minimum fungicidal concentrations (MFC), 10 μL of broth was taken from each well and incubated in Mueller-Hinton agar at 37°C for 24 h. The MFC was defined as the lowest concentration of extract that resulted in either no growth or fewer than three colonies (99.9% killing).[20] Each test was performed in three replicates and repeated twice. The negative control consisted of 100 μL of the fungus inoculums in 100 μL of DMSO 2.5%, and nystatin (100.000 IU/mL) was used as positive control.

RESULTS

Pharmacognostical characterization

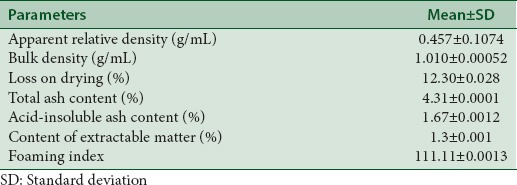

The results of pharmacognostical characterization of C. icaco herbal drug are shown in Table 1. The granulometric analysis indicates that the C. icaco herbal drug is a moderately coarse powder. The values for moisture content, total ash content, and acid-insoluble ash content were within the established limits for herbal drug, according to the Brazilian Pharmacopoeia.[14] The parameters foaming index, content of extractable matter, bulk density, and apparent relative density corresponded to the values for qualitative assays and characterize the herbal drug used in the present work.

Table 1.

Pharmacognostical characterization of dry powder of Chrysobalanus icaco leaves

Preliminary phytochemical screening

The phytochemical screening of the HECi indicates the presence of the following metabolic classes: Saponin, reducer sugars, protein and amino acids, tannins, flavonoids, sesquiterpene lactones, triterpenoids and steroids, carotenoids, and depside and depsidone.

Total flavonoid content analysis of hydroalcoholic extract of Chrysobalanus icaco

Using the aluminum complexation reaction, the amount of total flavonoids in HECi was determined as 132,959.33 ± 12,598.23 µg quercetin equivalent/g of extract. Talvez fosse melhor: expressed in quercetin.

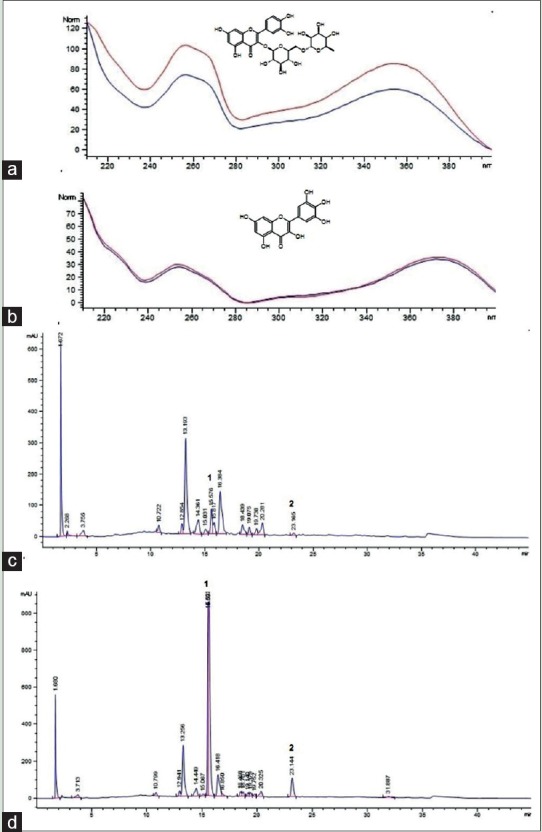

High-performance liquid chromatography analysis of hydroalcoholic extract of Chrysobalanus icaco

The HPLC analyses were able to characterize the presence of rutin and myricetin in HECi by comparison of their ultraviolet (UV) spectra [Figure 1a and b] with those obtained from the standard substances. The co-injection of these authentic substances with HECi produces an area increase of the peaks at retention time (Rt) of 15.59 and 23.14 min, which confirms the presence of the flavonoids such as rutin and myricetin, respectively, in the extract [Figure 1c and d].

Figure 1.

High-performance liquid chromatography analysis of hydroalcoholic extract of Chrysobalanus icaco. (a) Ultraviolet spectra (190–400 nm) of rutin peak (red line) overlayed with hydroalcoholic extract of Chrysobalanus icaco peak (blue line; Rt = 15.59 min). (b) Ultraviolet spectra of (190–400 nm) myricetin peak overlayed with hydroalcoholic extract of Chrysobalanus icaco peak (Rt = 23.14 min). Identification of peaks: 1, rutin; 2, myricetin. (c) High-performance liquid chromatography chromatogram of hydroalcoholic extract of Chrysobalanus icaco (260 nm). (d) High-performance liquid chromatography chromatogram of hydroalcoholic extract of Chrysobalanus icaco with co-injection of rutin and myricetin (260 nm)

Antifungal activity of the hydroalcoholic extract of Chrysobalanus icaco

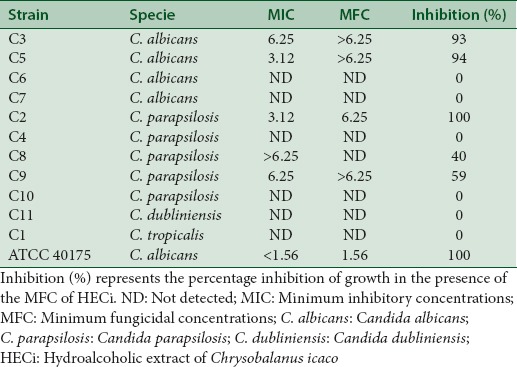

Table 2 shows MIC and MFC values of the HECi against different isolates of Candida spp. The HECi was active against clinical isolates of C. albicans and C. parapsilosis with MICs values ranging from of 3.12 to 6.25 mg/mL and MFC above 6.25 mg/mL. On the other hand, the HECi was not active against clinical isolates of C. dubliniensis and C. tropicalis in all concentrations tested. As expected, the HECi exhibited activity against the strain of C. albicans ATCC with MFC of 1.56 mg/mL.

Table 2.

Antifungal activity of hydroalcoholic extract of Chrysobalanus icaco against oral clinical isolates of Candida spp. minimum inhibitory concentrations and minimum fungicidal concentrations values are expressed as (mg/mL)

DISCUSSION

Qualitative pharmacognostical parameters encompass a set of physical and phytochemical tests outlined from pharmacopoeias and international guidelines. To characterize the herbal drug obtained from leaves of C. icaco, these parameters were evaluated following the normative requirements for the registration of herbal medicines and are able to predict the purity of raw material and phytochemical constitution of the HECi.[14] The values of pharmacognostical characterization demonstrated that the raw material was correctly processed and stored, and these values were similar to previously determined for total ash content.[22] Concerning to the other pharmacognostical parameters, the powdered leaves of C. icaco showed values which are within the limits set forth in Brazilian Pharmacopoeia.[14]

Preliminary phytochemical screening was performed by colorimetric and precipitation reactions aiming to identify some metabolic classes in HECi. Through preliminary phytochemical screening, the presence of classes of compounds already reported in the literature for the species could be identified in the HECi. Barbosa et al.[12] as well as in our study identified the presence of saponin, flavonoids, tannins, catechins, triterpenoids, and steroids. Several compounds have been identified and isolated in preparations obtained from different parts of C. icaco including kaurane-type diterpenes, phytosterols (stigmasterol, sitosterol, and campesterol), terpene (Pomolic acid), flavonoid 7-O-methyl kaempferol, catechin, and anthocyanins.[9,10,23]

Flavonoids and terpenes are the major compounds present in Chrysobalanaceae species.[24] Using aluminum complexation reaction, the determination of TFC in HECi showed high level, which highlights the majority of these compounds present in C. icaco. Among the flavonoids previously reported for C. icaco, myricetin[8] figure as its possible phytochemical marker. To verify the presence of this flavonoid as well as the presence of rutin in HECi, HPLC analysis was performed. The chromatographic profile of HECi [Figure 1c] compared to that obtained by co-injection of HECi with myricetin and rutin [Figure 1d], and the similarity of the UV spectra of HECi corresponding peaks and standards, allowed to conclude that these flavonoids are present in the extract [Figure 1a and b, respectively]. Several authors have previously reported the identification of both flavonoids in C. icaco crude extracts.[8,25,26]

This study also reports the antifungal activity of C. icaco against oral clinical isolates of Candida spp. obtained from healthy volunteers. HECi exhibited good antifungal activity against some clinical isolates of C. albicans and C. parapsilosis, but not against C. dubliniensis and C. tropicalis [Table 2]. On the other hand, other study showed that the methanol and hexane extracts, fractions. and compounds isolated from C. icaco did not inhibited different strains of C. albicans.[9]

This antifungal action of HECi can be explained by the chemical composition of the extract evaluated. In this regards, myricetin-3-O-β-allopyranoside isolated from hydroalcoholic extract of Plinia cauliflora leaves showed antifungal activity against C. albicans with MIC and MFC values of 250 and 500 µg/mL, respectively.[27] Shahid also reported the antimicrobial potential of a myricetin derivative against different microorganisms such as seven clinical isolates of C. albicans with MIC ranging from 3.9 to 31 µg/mL.[28] Rutin also has been reported showing antifungal activity against Candida spp. strains. Araruna et al. reported the antifungal activity of the flavonoid, i.e., rutin against C. albicans, Candida krusei, and C. tropicalis ATCCs with MICs of 32 μg/mL for each strain.[29] Rutin was also able to inhibit the growth of C. albicans in a dose-dependent manner (P < 0.01); the concentrations of rutin ranged between 250 and 1000 μg/Ml.[30]

Other compounds present in HECi may also be responsible for the antifungal activity such as terpenoids, tannins, and steroids.[31,32,33] The resistance of C. dubliniensis and C. tropicalis isolates and some isolates of C. albicans and C. parapsilosis to the HECi could be explained by the intra- and inter-species genomic variation, which includes differences in virulence factors, for example. According to Cantón et al., there is a variation in the antifungal activity of amphotericin B against different isolates of Candida spp. and this is due to the gene variation within the specie.[34] As expected from the reported experiments, C. albicans ATCC was more sensitive compared to clinical isolates because clinical isolates strains exhibit more genetic variation; consequently, they present major virulence factors.[35]

CONCLUSION

HECi presented antifungal activity against C. albicans and C. parapsilosis clinical isolates, both species with clinical importance in the development of oral candidiasis. The antifungal activity of the HECi may be due to the presence of the flavonoids such as rutin and myricetin in the extract. Furthermore, more investigations are required to assess the possible toxicity and the action mechanism of C. icaco for the development of herbal drugs derived from this species.

Financial support and sponsorship

The study was financially supported by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), for scientific fellowships.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

ABOUT AUTHOR

Marcieni Ataíde de Andrade

Marcieni Ataíde de Andrade, is an Adjunct Professor at the Pharmacy College (Federal Universty of Pará – Brazil) and at the Postgraduate Program in Pharmaceutical Sciences (Federal Universty of Pará – Brazil). She is Head of Laboratory of Pharmacognosy since 2010 and has projects in collaboration with national institutions. She is expert in Pharmacognosy and Chemistry of Natural Products, with projects in the following fields: Medicinal plants, Phytochemical analysis, Aging, and Public Health.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Professor Maurimélia Mesquita (in memoriam) for Candida species identification and all support in this work. The authors are also grateful to the Herbarium of the Brazilian Agricultural

Research Corporation – Eastern Amazon (EMBRAPA) for plant species identification and to the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), for scientific fellowships. We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of Pró-Reitoria de Pesquisa e Pós-Graduação from UFPA (PROPESP/UFPA).

REFERENCES

- 1.Mayer FL, Wilson D, Hube B. Candida albicans pathogenicity mechanisms. Virulence. 2013;4:119–28. doi: 10.4161/viru.22913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh A, Verma R, Murari A, Agrawal A. Oral candidiasis: An overview. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014;18(Suppl 1):S81–5. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.141325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang LW, Fu JY, Hua H, Yan ZM. Efficacy and safety of miconazole for oral candidiasis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Dis. 2016;22:185–95. doi: 10.1111/odi.12380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akpan A, Morgan R. Oral candidiasis. Postgrad Med J. 2002;78:455–9. doi: 10.1136/pmj.78.922.455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen SC, Sorrell TC. Antifungal agents. Med J Aust. 2007;187:404–9. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fenner R, Betti AH, Mentz LA, Rates SM. Plantas utilizadas na medicina popular brasileira com potencial atividade antifúngica. Rev Bras Ciênc Farm. 2006;42:369–94. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee County Extension. Brown SH. Chrysobalanus icaco. [Last cited on 2015 Dec 12]. Available from: http://www.lee.ifas.ufl.edu/Hort/GardenPubsAZ/Cocoplum_Chrysobalanus_icaco.pdf .

- 8.Barbosa WL, Peres A, Gallori S, Vincieri FF. Determination of myricetin derivatives in Chrysobalanus icaco L. (Chrysobalanaceae) Braz J Pharmacogn. 2006;16:333–7. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castilho RO, Kaplan MA. Phytochemical study and antimicrobial activity of Chrysobalanus icaco. Chem Nat Comp. 2011;47:436–7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Brito ES, de Araújo MC, Alves RE, Carkeet C, Clevidence BA, Novotny JA. Anthocyanins present in selected tropical fruits: Acerola, jambolão, jussara, and guajiru. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:9389–94. doi: 10.1021/jf0715020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernandes J, Castilho RO, da Costa MR, Wagner-Souza K, Coelho Kaplan MA, Gattass CR. Pentacyclic triterpenes from Chrysobalanaceae species: Cytotoxicity on multidrug resistant and sensitive leukemia cell lines. Cancer Lett. 2003;190:165–9. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00593-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barbosa AP, Silveira Gde O, de Menezes IA, Rezende Neto JM, Bitencurt JL, Estavam Cdos S, et al. Antidiabetic effect of the Chrysobalanus icaco L. aqueous extract in rats. J Med Food. 2013;16:538–43. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2012.0084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.White PA, Cercato LM, Batista VS, Camargo EA, De Lucca W, Jr, Oliveira AS, et al. Aqueous extract of Chrysobalanus icaco leaves, in lower doses, prevent fat gain in obese high-fat fed mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 2016;179:92–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brazilian Pharmacopoeia. 5th ed. Brasília: Fascicule 1; 2010. Brazil – Brazilian Health Surveillance Agency [ANVISA] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. Quality Control Methods for Medicinal Plant Materials. Update Edition. Geneva: WHO; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Costa A, Proença F, Cunha A. Farmacognosia. 3th ed. Lisboa: Calouste Gulbenkian; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pękal A, Pyrzynska K. Evaluation of aluminium complexation reaction for flavonoid content assay. Food Anal Methods. 2014;7:1776–82. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Byadarahally Raju S, Rajappa S. Isolation and identification of Candida from the oral cavity. ISRN Dent. 2011;2011:487921. doi: 10.5402/2011/487921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Approved Standard M27-A3. 3rd ed. Wayne: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2008. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts. [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Quadros AU, Bini D, Pereira PA, Moroni EG, Monteiro MC. Antifungal activity of some cyclooxygenase inhibitors on Candida albicans: PGE2-dependent mechanism. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 2011;56:349–52. doi: 10.1007/s12223-011-0049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aguiar TM. Physical and chemical characteristics of leaves, fruits and seeds of bajuru (Chrysobanalus icaco, L.) and evaluation of these tea leaves in mice (swiss) normal and diabetic [Dissertation] Seropédica Federal Rural University of Rio de Janeiro. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gustafson KR, Munro MH, Blunt JW, Cardellina JH, 2nd, McMahon JB, Gulakowski RJ, et al. HIV inhibitory natural products: 3. Diterpenes from Homalanthus acuminatus and Chrysobalanus icaco. Tetrahedron. 1991;47:4547–54. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feitosa EA, Xavier HS, Randau KP. Chrysobalanaceae: Traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology. Braz J Pharmacogn. 2012;22:1181–6. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chaffaud M, Emberger L. Traité de Botanique Systematique. Vol. 2. Paris, France: Masson; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Connolly JD, Hill RA. Methods in Plant Biochemistry. Vol. 7. London: Academic Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Souza TM, Severi JA, Vilegas W, Pietro RC. Myricetin from Plinia cauliflora (Mart.) Kausel and activity against Candida albicans. Planta Med. 2009;75:PA84. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shahid AA. Biological activities of extracts and isolated compounds from Bauhinia galpinii (Fabaceae) and Combretum vendee (Combretaceae) as potential antidiarrhoeal agents [thesis] Pretoria: University of Pretoria; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Araruna MK, Brito SA, Morais-Braga MF, Santos KK, Souza TM, Leite TR, et al. Evaluation of antibiotic and antibiotic modifying activity of pilocarpine and rutin. Indian J Med Res. 2012;135:252–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Han Y. Rutin has therapeutic effect on septic arthritis caused by Candida albicans. Int Immunopharmacol. 2009;9:207–11. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gupta N, Saxena G, Kalra SS. Antimicrobial activity pattern of certain terpenoids. Int J Pharma Bio Sci. 2011;2:87–91. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh B, Sharma RA, Vyas GK, Sharma P. Estimation of phytoconstituents from Cryptostegia grandiflora (Roxb.) R. Br. in vivo and in vitro. II. Antimicrobial screening. J Med Plants Res. 2011;5:1598–605. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reddy MK, Gupta SK, Jacob MR, Khan SI, Ferreira D. Antioxidant, antimalarial and antimicrobial activities of tannin-rich fractions, ellagitannins and phenolic acids from Punica granatum L. Planta Med. 2007;73:461–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-967167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cantón E, Pemán J, Gobernado M, Viudes A, Espinel-Ingroff A. Patterns of amphotericin B killing kinetics against seven Candida species. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:2477–82. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.7.2477-2482.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Calderone RA, Fonzi WA. Virulence factors of Candida albicans. Trends Microbiol. 2001;9:327–35. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(01)02094-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]