Newspapers have long known the value of burying comics within their pages to ensure that readers purchase the paper and ultimately view more stories—and advertisements. According to Wikipedia, the expression “Use a picture. It's worth a thousand words.” originates from Syracuse Post-Standard newspaper editor Tess Flanders in 1911.1 Studies demonstrate the emotional power of a single picture and that emotion enhances memory,2 and many times, teachers use graphics, cartoons, and humor to capture trainees' interest, engage memory, and stimulate reflection.3–5

As the audience of the Journal of Graduate Medical Education (JGME) includes many educators, we are expanding the scope of the existing personal essay category, “On Teaching,” to include graphic materials, such as cartoons, graphic novels, art, and photographs, as well as humorous essays or comments (boxes 1 and 2, figure). Creative writing or graphics should address common or difficult issues in teaching and learning in graduate medical education, as well as engage and enlighten readers. The submissions should resonate with readers through their emotions, senses, and intellect. The material must be tasteful, but need not eschew controversial subjects. In fact, research demonstrates that humor can be a useful strategy to introduce reflection into conversations about personal biases, assumptions, and mechanisms for coping under stress.6

box 1 Being a Real Doctor.

As a medical student, I was accustomed to helping patients dress, undress, or fetch a wheelchair. It felt good to be helpful. But as a “real doc” resident, it was much more gratifying to receive thanks from patients for helping them understand their meds or recover quickly from an illness. One day on rounds, our patient, always reluctant to discuss medical problems with the team, point-blank refused any conversation. He pointed to me and said, “I'll talk to her.” My ego swelled: he clearly discerned my meticulous approach and caring demeanor! The senior resident and others left grudgingly while I tried to smother a superior smile. The patient waited until all had left and ordered, “I need the bedpan.”

box 2 Keeping Up With the Literaturea.

Medical student Reads entire article but does not understand what any of it means.

Resident Would like to read entire article but eats dinner instead.

Chief resident Skips articles entirely and reads classifieds.

Senior attending Reads abstracts and quotes the literature liberally.

Chief of service Reads references to see if he or she was cited anywhere.

Emeritus attending Reads entire article but does not understand what any of it means.

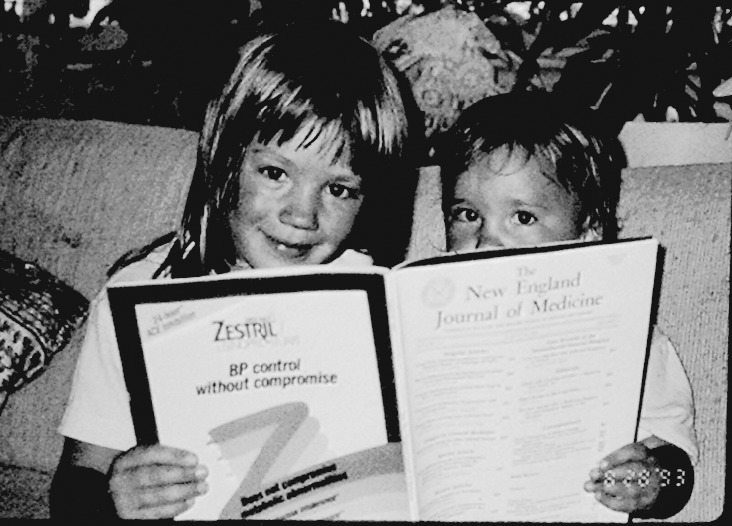

Figure.

What Attendings See When They Look at Residents

Art, cartoons, humorous anecdotes, and photographs may not work for every educator or every teaching portfolio. Yet we hope that these additions can be used by some educators to facilitate exploration of difficult topics, and can be enjoyed by all. The editors of JGME welcome your submissions and your feedback (e-mail jgme@acgme.org).

References

- 1. Wikipedia. A picture is worth a thousand words. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_picture_is_worth_a_thousand_words. Accessed November 4, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2. McConnell MM, Eva KW. . The role of emotion in the learning and transfer of clinical skills and knowledge. Acad Med. 2012; 87 10: 1316– 1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Plauche WC, Edwards JC. . Images and emotion in patient-centered clinical teaching. Perspect Biol Med. 1988; 31 4: 602– 609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ziegler JB. . Use of humour in medical teaching. Med Teach. 1998; 20 4: 341– 348. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bennett HJ. . Humor in medicine. South Med J. 2003; 96 12: 1257– 1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Piemonte NM. . Last laughs: gallows humor and medical education. J Med Humanit. 2015; 36 4: 375– 390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bennett HJ. . A piece of my mind. Keeping up with the literature. JAMA. 1992; 267 7: 920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]