Abstract

Background

Uterine leiomyomata, benign tumors of uterine smooth muscle that are characterized by overproduction of extracellular matrix (fibroids), are the leading indication for hysterectomy in the United States. The active metabolite of Vitamin D has been shown to inhibit cell proliferation and extracellular matrix production in fibroid tissue culture and to reduce fibroid volume in the Eker rat. No previous epidemiologic study has examined whether vitamin D is related to fibroid status in women.

Methods

The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Uterine Fibroid Study enrolled randomly selected 35–49 year-old members of an urban health plan during 1996–1999. Fibroid status was determined by ultrasound screening of premenopausal women (620 blacks, 416 whites). Vitamin D status was assessed in stored plasma by radioimmunoassay of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) and questionnaire data on sun exposure. Associations were evaluated with logistic regression, controlling for potential confounders.

Results

Only 10% of blacks and 50% of whites had sufficient 25(OH)D levels [>20 ng/ml]. Women with sufficient vitamin D had an estimated 32% reduced odds of fibroids compared with those with vitamin D insufficiency (adjusted odds ration, aOR=0.68, 95% confidence interval, CI=0.48, 0.96). The association was similar for blacks and whites. Self-reported sun exposure ≥1 hr/day (weather permitting) was also associated with reduced odds of fibroids (aOR=0.6, 95% CI=0.4, 0.9) with no evidence of heterogeneity by ethnicity.

Conclusions

The consistency of findings for questionnaire and biomarker data, the similar patterns seen in blacks and whites, and the biological plausibility provide evidence that sufficient vitamin D is associated with a reduced risk of fibroids.

Keywords: Leiomyoma, vitamin D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, sun exposure, ethnic disparity, ultrasound

Introduction

Leiomyomata (fibroids) are benign tumors that develop in the uterine muscle of premenopausal women. The most common symptoms are pain and bleeding with associated anemia.1 Though fibroids are hormonally dependent, factors that stimulate development are largely unknown.2,3 Fibroids are the leading indication for hysterectomy in the United States,4 and costs exceed six billion dollars annually.5 There is marked racial/ethnic disparity; blacks have earlier onset,6 higher incidence,7 experience more severe symptoms,8 present with larger tumors,8 and have a 3-fold higher risk of hysterectomy compared to whites.9

Maintenance of sufficient vitamin D levels has been associated with reduced risk of all cause mortality and chronic diseases including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, colon cancer and possibly other cancers, as well as specific autoimmune conditions including multiple sclerosis.10 Functional effects of vitamin D include reduced cell proliferation, increased apoptosis, enhanced differentiation, and regulation of biological processes including angiogenesis, extracellular matrix production, and immune response.11,12 The pathogenesis of fibroids has been hypothesized to involve a positive feedback loop between extracellular matrix production and cell proliferation,13 and vitamin D might act to block the positive feedback. Laboratory studies of fibroid tissue in culture that has been treated with calcitriol, the active form of vitamin D (1,25(OH)2D), demonstrate reduction in cell proliferation and extracellular matrix production. Studies in the Eker rat, an animal model for fibroids, show that treatment with calcitriol limits fibroid growth in vivo.14 However, there has been no previous epidemiologic investigation of vitamin D and fibroids.

National data show that vitamin D deficiency is common for premenopausal women in the United States especially for blacks.15 Most vitamin D is formed in the skin in response to sun exposure, and skin pigment reduces production. It is possible that low vitamin D status could increase susceptibility to fibroids. We investigated the relationship between vitamin D status and prevalence of fibroids in a randomly selected sample of premenopausal black and white women who were systematically screened for fibroids with ultrasound.

Methods

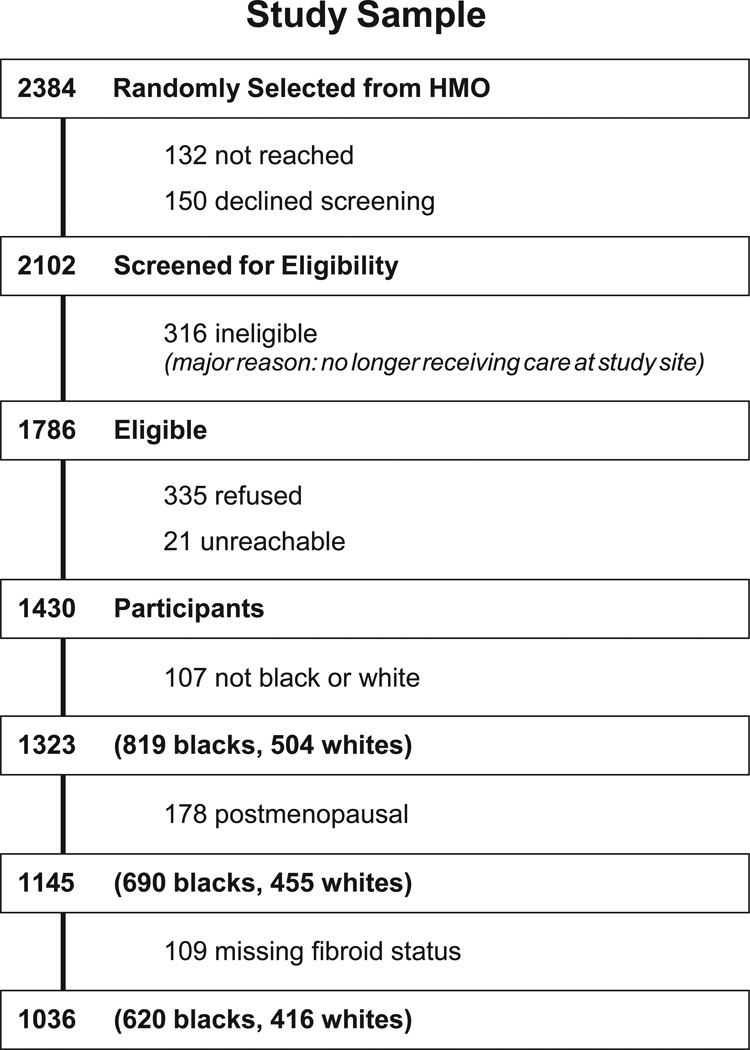

The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) Uterine Fibroid Study was conducted within a large health plan in Washington, DC. Enrollment occurred from 1996–1999, and methods have been described.7,16 Briefly, randomly selected health plan members, aged 35–49, were contacted, and 80% of those found to be eligible participated. The research was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at NIEHS and George Washington University, and participants gave informed consent. Premenopausal women were screened for fibroids with ultrasound and blood was drawn, processed and stored at −80°. The current analysis is limited to 1036 premenopausal women who self-identified as black or white (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Participation and sample selection, NIEHS Uterine Fibroid Study.

Fibroid status determination with transvaginal and transabdominal ultrasound screening (transabdominal allows for visualization of pedunculated fibroids that are not likely to be seen transvaginally) identified fibroids of ≥0.5 centimeter (cm) diameter. Experienced sonographers were trained for the protocol and worked under the direct supervision of one of the authors (MCH), a radiologist with expertise in ultrasound. Participants who had recently undergone an ultrasound examination at the clinic for clinical purposes (16%) were not asked to repeat an examination for the study. For these women, data on presence of fibroids and size of largest were abstracted from the clinic radiology reports. In addition, 14 women had had a prior uterine surgery, and we abstracted fibroid status data from pathology records for these women. For 50 participants who did not complete ultrasound screening examinations and for one woman whose examination was indeterminate, we accepted their self-report of a prior diagnosis. Statistical analyses were repeated without these 51 women, and results were essentially unchanged. Women who had not been previously diagnosed with fibroids and who did not complete the ultrasound examination were excluded from analyses (Fig. 1).

Vitamin D status was examined in two ways. First, we used stored plasma samples to measure the circulating metabolite, 25(OH)D, the accepted biomarker for vitamin D.17 Radioimmunoassay for 25(OH)D18 was conducted by one of the authors (BWH). Measurement of 25(OH)D was based on an antibody cospecific for 25(OH)D2 and 25(OH)D3. The laboratory has participated in and been certified by the international Vitamin D External Quality Assessment Scheme (DEQAS) survey for the past 12 years. Thirty blinded controls were distributed among the eight assay batches. Intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation based on the blind replicates were 7.6% and 10.6%, respectively. Second, we examined a measure of sun exposure. Women were asked at study enrollment, “On average, weather permitting, how many hours each day do you spend out of doors?” Categories were <1 hour/day, 1 hour per day, and >1 hour/day.

The association between vitamin D status and fibroids was evaluated using multiple logistic regression, with a priori control for other risk factors identified in prior analyses of this study population (ethnicity, age (linear), age of menarche (6-level ordinal variable with categories <11, 11, 12, 13, 14, ≥15), pregnancy history (3-level ordinal variable with categories 0,1,>1 pregnancies after age 24 – pregnancies at younger ages were not associated with fibroids19), body mass index (ordinal BMI <25, 25–29.9, 30–34.9, ≥35), and physical activity (4-level ordinal variable based on self-reported activity data used to estimate metabolic equivalents).16 The analyses were conducted with the total sample and for blacks and whites separately. We also examined associations by size of fibroid using polytomous logistic regression with a three category outcome (no fibroids, small – <4 cm diameter, large – ≥4 cm diameter). Given limited numbers, size of fibroid was only examined in the total data set. 25(OH)D was examined as a linear term and in 5-ng/ml categories to visually assess linearity. The assumption of linearity was evaluated by Akaike’s information criterion. 25(OH)D was also dichotomized based on a 2007 consensus workshop report that defined minimally sufficient levels as greater than 20 ng/ml.20 Linear regression was used to test for differences between blacks and whites in 25(OH)D concentrations after log transforming the data to improve normality, and possible differences by ethnic group in the association of the vitamin D variables with fibroids were evaluated by examining the importance of added interaction terms (vitamin D variable by ethnicity) to multivariate models.

Sensitivity analyses to assess affects of variations in fibroid determinations that affected a small proportion of participants (e.g., fibroids determined only on the bases of self report) did not affect results in any substantial way. Sensitivity analysis were also conducted to evaluate 1) the effect of dropping physical activity from the multivariate models (because including it may over-control for confounding), and 2) controlling for season (though it would not be expected to affect associations because it would be unrelated to fibroid status). The final sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess possible reverse causation that might arise if women with major fibroid symptoms of pain and bleeding curtailed their activities in ways that limited time outside or supplement use and thus resulted in reductions in 25(OH)D. Associations between vitamin D variables and fibroids were assessed after excluding women reporting frequent gushing type bleeding and/or pelvic pain of >4 days/mo that interfered “a lot” with normal activities. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Characteristics of the 1036 black and white study participants are shown in Table 1. Eighty percent reported spending at least an hour per day outside in good weather, our measure of medium to high sun exposure. Only 26% had sufficient circulating 25(OH)D (>20 ng/ml), the biomarker for vitamin D status. The mean 25(OH)D was 14.6 ng/ml ± (standard error of the mean (SE), 0.3), and levels were significantly lower in blacks than whites (10.4 ng/ml ± 0.3± and 20.7 ng/ml ± 0.4, respectively, P<0.001). The two methods of assessing vitamin D status, plasma 25(OH)D concentration and sun exposure were weakly correlated within each ethnic group (Spearman correlation for blacks = 0.10, 95%CI = 0.02 to 0.18 and for whites = 0.19, 95% CI =0.09 to 0.28).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Sample, NIEHS Uterine Fibroid Study, Enrollment 1996–1999.

| Characteristic | Total | Blacks | Whites |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 1036 | n = 620 | n = 416 | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Age | |||

| 35–39 | 362 (35) | 222 (36) | 140 (34) |

| 40–44 | 365 (35) | 225 (36) | 140 (34) |

| 45–49 | 309 (30) | 173 (28) | 136 (33) |

| Education | |||

| High school or less | 139 (14) | 127 (21) | 12 (3) |

| Some college or technical school | 316 (31) | 283 (47) | 33 (8) |

| College degree | 261 (26) | 126 (21) | 135 (34) |

| Post graduate degree | 289 (29) | 68 (11) | 221 (55) |

| Missing | 31 | 16 | 15 |

| Parity | |||

| 0 | 372 (36) | 132 (21) | 240 (58) |

| ≥1 | 664 (64) | 488 (79) | 176 (42) |

| Age of menarche | |||

| ≤10 | 86 (8) | 68 (11) | 18 (4) |

| 11 | 162 (16) | 101 (16) | 61 (15) |

| 12 | 285 (28) | 171 (28) | 114 (28) |

| 13 | 287 (28) | 147 (24) | 140 (34) |

| 14 | 106 (10) | 60 (10) | 46 (11) |

| ≥15 | 105 (10) | 70 (11) | 35 (8) |

| Missing | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | |||

| <25 | 400 (39) | 159 (26 | 241 (58) |

| 25–29.9 | 287 (28) | 187 (30) | 100 (24) |

| 30–34.9 | 161 (16) | 123 (20) | 38 (9) |

| ≥35 | 187 (18) | 150 (24) | 37 (9) |

| Missing | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Physical Activity | |||

| Low | 332 (32) | 221 (36) | 111 (27) |

| Moderate | 337 (33) | 196 (32) | 141 (34) |

| High | 191 (19) | 104 (17) | 87 (21) |

| Very high | 171 (17) | 95 (15) | 76 (18) |

| Missing | 5 | 4 | 1 |

| Plasma 25(OH) D | |||

| Insufficient (≤20 ng/ml) | 718 (74) | 521 (90) | 197 (50) |

| Sufficient (>20 ng/ml) | 258 (26) | 57 (10) | 201 (50) |

| Missing | 60 | 42 | 18 |

| Sun Exposure | |||

| Low (<1 hour/day outside) | 201 (19) | 105 (17) | 96 (23) |

| Medium (1 hour/day outside) | 333 (32) | 155 (25) | 178 (43) |

| High (>1 hour/day outside) | 499 (48) | 358 (58) | 141 (34) |

| Missing | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Fibroid status | |||

| No fibroids | 362 (35) | 161 (26) | 201 (48) |

| Small (<4 cm diameter) | 471 (45) | 307 (50) | 164 (39) |

| Large (≥4 cm diameter) | 203 (20) | 152 (25) | 51 (12) |

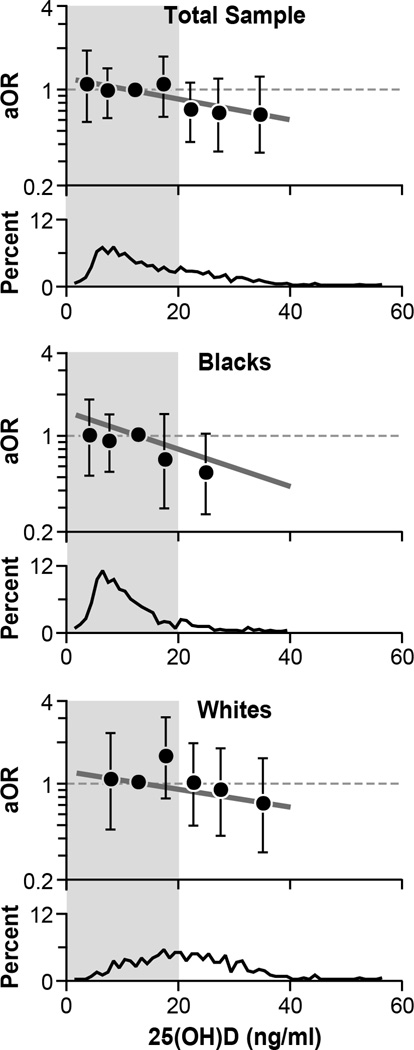

Fig. 2 shows the association between 25(OH)D and fibroid prevalence. When 25(OH)D was analyzed as a continuous variable, each 10 ng/ml increase in 25(OH)D was associated with an estimated 20% lower adjusted odds of having fibroids (aOR = 0.80, 95% CI = 0.65, 0.97). This was not substantially different from a simple age-ethnicity adjusted OR (0.73, 95% CI = 0.60, 0.87). Nor did the ORs differ by size of largest fibroid (aOR = 0.79 with 95% CI 0.64, 0.98 for fibroids < 4 cm and aOR = 0.81 with 95% CI 0.62, 0.98 for fibroids ≥4 cm). Essentially the same inverse linear trend was seen in both blacks and whites (aOR = 0.77 for blacks and aOR = 0.80 for whites) (Fig. 2). There was no statistical evidence of nonlinearity. Heterogeneity by ethnic group was not apparent (P=0.76). When 25(OH)D was dichotomized, women with sufficient vitamin D (25(OH)D >20 ng/ml) had an estimated 32% reduced odds of fibroids compared with those with vitamin D insufficiency (aOR=0.68 with 95% CI of 0.48, 0.96) (Fig. 2), and there was no evidence that the association differed between the two ethnic groups (P = 0.53).

Figure 2.

Association between 25(OH)D concentration and fibroid prevalence in total sample (top panel), blacks (middle panel), and whites (lower panel). The distribution of 25(OH)D is shown in the bottom section of each panel. The solid. heavy straight line on each panel shows the estimated decline in fibroid prevalence associated with linearly increasing 25(OH)D. The adjusted odds ratios associated with each 10 ng/ml increase in 25(OH)D concentration are shown to the right of these lines. The estimated adjusted odds ratios for fibroids associated with each 5-unit category of the 25(OH)D concentration are plotted with their 95% confidence intervals to allow for visual assessment of linearity. When sample size for a single 5-unit category was small, adjacent categories were combined and plotted at the mean value for the combined category, e.g., the last aOR plotted for the total sample is for the combined group of women with 25(OH)D >30 ng/ml, plotted at the mean for the category, 34.8 ng/ml. The left shaded area represents vitamin D insufficiency (≤20 ng/ml), and the adjusted odds ratio for fibroid prevalence associated with sufficient vitamin D is shown at the top right of each panel. All analyses adjusted for age, age of menarche, full-term pregnancies after age 24, body mass index, and physical activity. Analyses shown in the top panel (total sample) also adjust for ethnicity.

Our measure of sun exposure, time spent outside, was also inversely associated with fibroid prevalence. Both medium and high sun exposure showed the same reduction in adjusted odds of fibroids relative to low sun exposure (40% reduction in adjusted odds of fibroids relative to low sun exposure (aOR=0.6, 95% CI = 0.4, 0.9) (Table 2). This differed little from the simple age-ethnicity adjusted ORs (0.6 and 0.5 for medium and high exposure, respectively. The inverse association was seen for both blacks and whites (Table 2). Though the estimate was stronger for blacks than whites, there was no statistical evidence for heterogeneity by ethnicity (P = 0.34). Using data for the total sample, we also examined sun exposure in relation to fibroid size and found that the effect was similar, though slightly stronger for large fibroids than for small fibroids (aOR = 0.5, 95% CI = 0.3, 0.8 for large fibroids and aOR = 0.7, CI = 0.4, 1.0 for small fibroids).

Table 2.

Association of Sun Exposure with Prevalence of Fibroids, NIEHS Uterine Fibroid Study, Enrollment 1996–1999.

| Sun Exposure | Total Sample | Blacks | Whites | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na | aORb | 95% CI | Na | aORc | 95% CI | Na | aORc | 95% CI | |

| low | 145:197 | 1.0 | 88:103 | 1.0 | 57:94 | 1.0 | |||

| medium | 203:332 | 0.6 | 0.4,0.9 | 111:154 | 0.5 | 0.2,1.0 | 92:178 | 0.7 | 0.4,1.3 |

| high | 327:496 | 0.6 | 0.4,0.9 | 253:355 | 0.5 | 0.3,0.9 | 64:141 | 0.7 | 0.4,1.3 |

Number of cases:total; totals are slightly lower than those listed in Table 1 because of missing covariate data.

Adjusted for race/ethnicity, age, age of menarche, full-term pregnancies after age 24, body mass index, and physical activity.

Adjusted for age, age of menarche, full-term pregnancies after age 24, body mass index, and physical activity.

Sensitivity analyses to include adjustment for season showed nearly identical associations as the analysis without season. The effect of dropping physical activity as a confounder was evaluated because physical activity often takes place outside, so adjusting for it may over-control when analyzing vitamin-D status. The associations for 25(OH)D and sun exposure with fibroids were slightly stronger when not adjusting for physical activity. Each of the reductions in odds of fibroids was approximately 3% greater with no adjustment for physical activity. Sensitivity analyses to examine possible reverse causation that might arise from women curtailing their activities due to symptoms were conducted after excluding the 93 women who reported major symptoms of bleeding and/or pain. The aORs changed very little (aOR for sufficient 25(OH)D changed from 0.68 to 0.72, and the aORs for the medium and high sun exposure categories remained at 0.6).

Discussion

During the last decade, vitamin D has been found to have numerous functions other than calcium homeostasis and bone health.11,21,22 It may have a protective role for many health outcomes including all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, colorectal and breast cancer (and possibly other cancers), auto immune disease, infections, and adverse pregnancy outcomes.23,24 The data from the NIEHS Uterine Fibroid Study suggest that vitamin D might also be inversely associated with uterine fibroid development. Both our measures of vitamin D status (circulating 25(OH)D and time outside) showed an inverse association with fibroid prevalence, and the associations in blacks and whites were similar. Reductions in odds were similar for small fibroids and large fibroids. If the associations of our vitamin D variables had been only with large fibroids, this would have suggested the possibility of stronger effects on tumor growth than on tumor initiation, but inverse associations for both large and small fibroids were seen, suggesting that both initiation and growth might be inhibited.

Our findings are consistent with data showing a protective effect of treatment with calcitriol on fibroids in the Eker rat,25 an animal model of fibroids. In addition, calcitriol treatment of human uterine fibroid tissue in laboratory culture reduces cell proliferation26,27 and inhibit molecular pathways for fibrosis.28 Laboratory studies of vascular and airway smooth muscle show similar anti-proliferative responses to calcitriol,29,30 and the anti-fibrotic effects have also been observed in the kidney.31

For most people the major source of vitamin D is skin production by exposure to sunlight.11 The conversion of 7-dehydrocholesterol by ultraviolet radiation with subsequent isomerization to vitamin D is slowed by skin pigment. Thus, greater skin pigmentation tends to be associated with lower vitamin D status. The liver enzyme, vitamin D-25-hydroxylase, converts vitamin D to the major circulating metabolite, 25(OH)D, which is then metabolized in the kidney to the active metabolite, calcitriol. Extra-renal production of calcitriol likely occurs in many tissues as evidenced by wide spread expression of the enzyme producing calcitriol (CYP27B1) (e.g., colon, breast, monocytes and macrophages, cervical tissue, uterine endometrum, and placenta16,32–35). To our knowledge, myometrial tissue and fibroid tissue have not been evaluated for CYP27B1 activity, but both myometrium and fibroid tissue express the vitamin D receptor.26

The accepted biomarker of vitamin D status is circulating levels of 25(OH)D.11 We measured 25(OH)D with an FDA-approved radioimmunoassay (RIA) conducted by an experienced investigator (coauthor BAH). There is no agreed-upon standard for sufficient levels of 25(OH)D, but we used >20 ng/ml, the value considered to be a minimum adequate concentration in a 2007 workshop consensus report.20 By this standard the majority of our participants had insufficient vitamin D. The average 25(OH)D levels in a 2003–2006 national sample of reproductive age women was higher than in our study population (24.1 ng/ml versus 14.6 ng/ml), based on a similar RIA assay,15 Our samples were collected in 1996–1999 when there was not as much interest in vitamin D supplementation. However, levels similar to ours were recently reported for a sample of black and white women, aged 18–45.36 As in our study, 25(OH)D levels for black women were low in both the national sample and the more recent study (78% and 98% with insufficient levels, respectively).

Circulating 25(OH)D has both strengths and limitations as a biomarker. It integrates vitamin D from sun, food, and supplements, but its half-life in blood is only about 15 days.37 Thus, as in the cancer studies that have used this biomarker to assess vitamin D status, there is the assumption that each individual’s level tends to remain stable over time relative to the other members of the study population. Large studies that have measured 25(OH)D in the same person over time suggest that those who are low (or high) at baseline tend to remain low (or high) during multi-year follow-up.38–42 However, some within-person variation is seen even when measurements are only 2–3 weeks apart,43 and variation tends to increase with time between measurements. Furthermore, only one study reported on variation in black women and most women in that sample were postmenopausal.42

The questionnaire data on sun exposure provided a separate estimate of vitamin D status. This measure of vitamin D status will reflect long-term estimates if women’s behavior remains relatively stable over time. To our knowledge, the within-person stability from year to year has not been evaluated. However, reliability and validity of self-report are suggested by a study that reported moderate to high Kappa statistics for repeat measures of self-reported lifetime sun exposure (reliability) and significant association between the self-report and skin damage (validity).44 Our data on sun exposure were based on a single, simple question. There appeared to be a threshold with a similar inverse effect for one or more hours per day spent outside. More information on time of day outside, usual clothing, sun versus shade activities, sunscreen use, skin color, and winter sun vacations would provide improved exposure estimates.45 Dietary sources of vitamin D are limited,11 but detailed information on supplement use would be informative. These more detailed assessments should be used in future studies.

A major strength of our study was that we screened women for fibroids with ultrasound to limit disease misclassification in the non-cases, a methodologic improvement over other fibroid studies. However, as in other studies, time of disease onset was unknown. Ideally, vitamin D status would be assessed before disease onset, but this requires periodic ultrasound screening to document the time of disease onset. Such intensive disease surveillance has not been done for fibroids. Though reverse causation is always an issue with cross-sectional data, we are unaware of fibroid-related physiological changes that would reduce 25(OH)D levels. In addition, the sensitivity analyses we conducted to examine reverse causation possibly resulting from behavior changes in women with major symptoms, indicated that our results cannot be explained by this bias.

In summary, we found an inverse association between vitamin D exposure and fibroid prevalence. The consistency of findings for questionnaire and biomarker data, the similar patterns seen in blacks and whites, and the biological plausibility provide evidence for a possible causal relationship between sufficient vitamin D and reduced risk of fibroids that needs further investigation.

Acknowledgements

We thank Glenn Heartwell who managed the study, Deborah Cousins and Tina Saldana who managed the data, the research staff who developed study materials, met with participants, conducted ultrasound examinations, conducted interviews, collected, processed, and inventoried blood samples, and conducted data quality control. Drs. Clarice Weinberg and Shannon Laughlin provided comments on an earlier draft of the manuscript. Dr. Sue Edelstein prepared the figures.

Sources of Funding

This research was funded by the intramural program at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, NIH, with support from the Office of Research on Minority Health, National Institutes of Health, HHS

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

None

References

- 1.Stewart EA. Uterine fibroids. Lancet. 2001;357(9252):293–298. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03622-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwartz SM, Marshall LM. Uterine Leiomyomata. In: Goldman MB, Hatch MC, editors. Women and Health. San Diego, California: Acadmic Press; 2000. pp. 240–252. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwartz SM, Marshall LM, Baird DD. Epidemiologic contributions to understanding the etiology of uterine leiomyomata. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108(Suppl 5):821–827. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108s5821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farquhar CM, Steiner CA. Hysterectomy rates in the United States 1990-1997. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99(2):229–234. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01723-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cardozo ER, Clark AD, Banks NK, Henne MB, Stegmann BJ, Segars JH. The estimated annual cost of uterine leiomyomata in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(3):211, e1–e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laughlin SK, Baird DD, Savitz DA, Herring AH, Hartmann KE. Prevalence of uterine leiomyomas in the first trimester of pregnancy: an ultrasound-screening study. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(3):630–635. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318197bbaf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baird DD, Dunson DB, Hill MC, Cousins D, Schectman JM. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(1):100–107. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kjerulff KH, Langenberg P, Seidman JD, Stolley PD, Guzinski GM. Uterine leiomyomas. Racial differences in severity, symptoms and age at diagnosis. J Reprod Med. 1996;41(7):483–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Myers ER, Barber MW, Couchman GM, Datta S, Gray RN, Gustilo-Ashby T, Kolimaga JT, McCrory DC. Management of uterine fibroids (Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 34, contract 290-97-0014 to the Duke Evidence-based Practice Center) AHRQ Publication No. 01-E052. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2001. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Makariou S, Liberopoulos EN, Elisaf M, Challa A. Novel roles of vitamin D in disease: what is new in 2011? Eur J Intern Med. 2011;22(4):355–362. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(3):266–281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fleet JC, DeSmet M, Johnson R, Li Y. Vitamin D and cancer: a review of molecular mechanisms. Biochem J. 2012;441(1):61–76. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leppert PC, Catherino WH, Segars JH. A new hypothesis about the origin of uterine fibroids based on gene expression profiling with microarrays. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(2):415–420. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.12.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sabry M, Al-Hendy A. Innovative oral treatments of uterine leiomyoma. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2012;2012:943635. doi: 10.1155/2012/943635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao G, Ford ES, Tsai J, Li C, Croft JB. Factors Associated with Vitamin D Deficiency and Inadequacy among Women of Childbearing Age in the United States. ISRN Obstet Gynecol. 2012;2012:691486. doi: 10.5402/2012/691486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baird DD, Dunson DB, Hill MC, Cousins D, Schectman JM. Association of physical activity with development of uterine leiomyoma. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(2):157–163. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hollis BW. Editorial: The determination of circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D: no easy task. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(7):3149–3151. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hollis BW, Kamerud JQ, Selvaag SR, Lorenz JD, Napoli JL. Determination of vitamin D status by radioimmunoassay with an 125I-labeled tracer. Clin Chem. 1993;39(3):529–533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baird DD, Dunson DB. Why is parity protective for uterine fibroids? Epidemiology. 2003;14(2):247–250. doi: 10.1097/01.EDE.0000054360.61254.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norman AW, Bouillon R, Whiting SJ, Vieth R, Lips P. 13th Workshop consensus for vitamin D nutritional guidelines. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;103(3–5):204–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.12.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haussler MR, Jurutka PW, Mizwicki M, Norman AW. Vitamin D receptor (VDR)-mediated actions of 1alpha,25(OH)(2)vitamin D(3): genomic and non-genomic mechanisms. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 25(4):543–559. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pilz S, Tomaschitz A, Marz W, Drechsler C, Ritz E, Zittermann A, Cavalier E, Pieber TR, Lappe JM, Grant WB, Holick MF, Dekker JM. Vitamin D, cardiovascular disease and mortality. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 75(5):575–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.04147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giovannucci E. Vitamin D and cancer incidence in the Harvard cohorts. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19(2):84–88. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holick MF. Vitamin D: extraskeletal health. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 39(2):381–400. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2010.02.016. table of contents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Halder SK, Sharan C, Al-Hendy A. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 treatment shrinks uterine leiomyoma tumors in the Eker rat model. Biol Reprod. 2012;86(4):116. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.111.098145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blauer M, Rovio PH, Ylikomi T, Heinonen PK. Vitamin D inhibits myometrial and leiomyoma cell proliferation in vitro. Fertil Steril. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.02.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharan C, Halder SK, Thota C, Jaleel T, Nair S, Al-Hendy A. Vitamin D inhibits proliferation of human uterine leiomyoma cells via catechol-O-methyltransferase. Fertil Steril. 2010;95(1):247–253. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.07.1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Halder SK, Goodwin JS, Al-Hendy A. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 reduces TGF-beta3-induced fibrosis-related gene expression in human uterine leiomyoma cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(4):E754–E762. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zittermann A, Schleithoff SS, Koerfer R. Putting cardiovascular disease and vitamin D insufficiency into perspective. Br J Nutr. 2005;94(4):483–492. doi: 10.1079/bjn20051544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Song Y, Qi H, Wu C. Effect of 1,25-(OH)2D3 (a vitamin D analogue) on passively sensitized human airway smooth muscle cells. Respirology. 2007;12(4):486–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2007.01099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tan X, Li Y, Liu Y. Therapeutic role and potential mechanisms of active Vitamin D in renal interstitial fibrosis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;103(3–5):491–496. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cross HS, Kallay E. Regulation of the colonic vitamin D system for prevention of tumor progression: an update. Future Oncol. 2009;5(4):493–507. doi: 10.2217/fon.09.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Friedrich M, Rafi L, Mitschele T, Tilgen W, Schmidt W, Reichrath J. Analysis of the vitamin D system in cervical carcinomas, breast cancer and ovarian cancer. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2003;164:239–246. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-55580-0_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Becker S, Cordes T, Diesing D, Diedrich K, Friedrich M. Expression of 25 hydroxyvitamin D3-1alpha-hydroxylase in human endometrial tissue. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;103(3–5):771–775. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.12.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zehnder D, Evans KN, Kilby MD, Bulmer JN, Innes BA, Stewart PM, Hewison M. The ontogeny of 25-hydroxyvitamin D(3) 1alpha-hydroxylase expression in human placenta and decidua. Am J Pathol. 2002;161(1):105–114. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64162-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coney P, Demers LM, Dodson WC, Kunselman AR, Ladson G, Legro RS. Determination of vitamin D in relation to body mass index and race in a defined population of black and white women. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012;119(1):21–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jones G. Pharmacokinetics of vitamin D toxicity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(2):582S–586S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.2.582S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jorde R, Sneve M, Hutchinson M, Emaus N, Figenschau Y, Grimnes G. Tracking of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels during 14 years in a population-based study and during 12 months in an intervention study. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171(8):903–908. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kluczynski MA, Wactawski-Wende J, Platek ME, DeNysschen CA, Hovey KM, Millen AE. Changes in vitamin D supplement use and baseline plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration predict 5-y change in concentration in postmenopausal women. J Nutr. 2012;142(9):1705–1712. doi: 10.3945/jn.112.159988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meng JE, Hovey KM, Wactawski-Wende J, Andrews CA, Lamonte MJ, Horst RL, Genco RJ, Millen AE. Intraindividual variation in plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D measures 5 years apart among postmenopausal women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(6):916–924. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saliba W, Barnett O, Stein N, Kershenbaum A, Rennert G. The longitudinal variability of serum 25(OH)D levels. Eur J Intern Med. 2012;23(4):e106–e111. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sonderman JS, Munro HM, Blot WJ, Signorello LB. Reproducibility of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin d and vitamin D-binding protein levels over time in a prospective cohort study of black and white adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176(7):615–621. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kant AK, Graubard BI. Ethnic and socioeconomic differences in variability in nutritional biomarkers. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(5):1464–1471. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.5.1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van der Mei IA, Blizzard L, Ponsonby AL, Dwyer T. Validity and reliability of adult recall of past sun exposure in a case-control study of multiple sclerosis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(8):1538–1544. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCarty CA. Sunlight exposure assessment: can we accurately assess vitamin D exposure from sunlight questionnaires? Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(4):1097S–1101S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.4.1097S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]