This special article describes the Sudden Death in the Young Case Registry, which provides valuable incidence data and enhances understanding of the characteristics of pediatric deaths to inform prevention efforts.

Abstract

Knowledge gaps persist about the incidence of and risk factors for sudden death in the young (SDY). The SDY Case Registry is a collaborative effort between the National Institutes of Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Michigan Public Health Institute. Its goals are to: (1) describe the incidence of SDY in the United States by using population-based surveillance; (2) compile data from SDY cases to create a resource of information and DNA samples for research; (3) encourage standardized approaches to investigation, autopsy, and categorization of SDY cases; (4) develop partnerships between local, state, and federal stakeholders toward a common goal of understanding and preventing SDY; and (5) support families who have lost loved ones to SDY by providing resources on bereavement and medical evaluation of surviving family members. Built on existing Child Death Review programs and as an expansion of the Sudden Unexpected Infant Death Case Registry, the SDY Case Registry achieves its goals by identifying SDY cases, providing guidance to medical examiners/coroners in conducting comprehensive autopsies, evaluating cases through child death review and an advanced review by clinical specialists, and classifying cases according to a standardized algorithm. The SDY Case Registry also includes a process to obtain informed consent from next-of-kin to save DNA for research, banking, and, in some cases, diagnostic genetic testing. The SDY Case Registry will provide valuable incidence data and will enhance understanding of the characteristics of SDY cases to inform the development of targeted prevention efforts.

Sudden death in the young (SDY) is a tragic event with longstanding impact on families and communities. Although the causes of SDY are myriad, sudden unexpected infant death (SUID), sudden cardiac death, and sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) are 3 examples that have inspired public health efforts at prevention. Healthy People 2020, a national health promotion agenda for the United States, includes in its objectives the need to reduce the rate of deaths of infants, children, and adolescents.1 Unfortunately, fundamental gaps in knowledge about the incidence, mechanisms, and risk factors of SDY may limit the identification of effective prevention efforts.

The majority of SDY occurs during infancy and has been termed SUID, a group of deaths that encompass sudden infant death syndrome, sleep-related accidental suffocation, and infant deaths of unknown cause. In the United States in 2013, SUID accounted for ∼1 in 7 infant deaths.2 Some researchers suggest that up to 20% of sudden infant death syndrome cases may be due to ion channelopathies.3 Sudden cardiac death is another cause of SDY that attracts significant attention. Sudden cardiac death may occur at any age across the life span and may be associated with competitive athletics. Estimates of the incidence of sudden cardiac death in infants, children, and young adults vary from 0.5 to 2.3 per 100 000, depending on the population examined.4–10 Cardiac causes of SDY include hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, coronary artery anomalies, arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, and ion channelopathies, among others.11 SUDEP is another cause of SDY that has been documented at all ages. It is seen in both idiopathic epilepsy (ie, cause is unknown) and genetic forms of epilepsy (eg, Dravet syndrome), and in association with ion channelopathies. Known risk factors for SUDEP include the presence of continued seizures, especially generalized tonic–clonic seizures, nonadherence with antiseizure medications, and polytherapy in individuals with refractory epilepsy. According to 1 review, the incidence of SUDEP in those <20 years old in the United States in 2014 was 0.11 per 100 000,12 but this figure is likely underestimated.13

Some causes of SDY are inherited, and surviving family members may unknowingly harbor conditions that place them at risk for SDY as well. Identifying heritable causes of death after a case of SDY is a critical step in enabling cascade screening of surviving family members and access to potentially life-saving therapies (such as β-blockers for Long QT syndrome and implantable cardioverter defibrillators for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy). Cascade screening may also decrease later complications and potential life-years lost due to a delayed or missed diagnosis.

Although SDY is acknowledged to be an important public health and scientific issue, there is significant scientific disagreement, fueled by lack of evidence, about the best approach to prevent it. Many promising efforts have focused on promoting safe sleeping environments and effective seizure control, as well as training the community on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and automated external defibrillators. But without a true understanding of the incidence, risk factors, and mechanisms of disease, it is difficult to know if such efforts are focusing on the right targets. Improved understanding of disease may allow for the design of more targeted and potentially more impactful interventions.

Some have called for the implementation of widespread enhanced cardiovascular screening programs (ie, with an electrocardiogram) to identify individuals with conditions associated with sudden cardiac death, an undertaking that would require significant financial and personnel resources. The success of such a screening program to identify conditions associated with a rare event like sudden cardiac death depends on the likelihood of disease in the population. Yet we lack fundamental data on incidence to inform discussions about the potential costs and value of such an effort. This knowledge gap on incidence persists in part due to a lack of standardized procedures for investigating, classifying, and reporting SDY in the United States.

In 2010, a working group of experts convened by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) highlighted this knowledge gap on incidence and recommended the development of a registry to gather evidence about the epidemiology and etiology of sudden cardiac death in the young in the United States as a fundamental first step in advancing our understanding.14 The Institute of Medicine’s 2015 report, “Strategies to Improve Cardiac Arrest Survival,” also recommended the establishment of a national cardiac arrest registry that includes standard definitions and data elements.15 A 2012 Institute of Medicine report on the public health dimensions of epilepsy highlighted similar gaps in public health surveillance of SUDEP and corresponding gaps in the overall burden.16

Leveraging Existing Infrastructure

Before proceeding with developing a new registry, NHLBI explored the landscape of existing programs and identified 2 promising potential partners: the National Center for Fatality Review and Prevention’s (NCFRP) Child Death Review (CDR) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) SUID Case Registry.

CDR

CDR programs in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Guam, and the Navajo Nation conduct comprehensive, multidisciplinary reviews of infant and child deaths. The purpose is to better understand how and why children die and to use the findings to take action to prevent future deaths, thereby improving the health and safety of all children.17 NCFRP,18 funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), Maternal and Child Health Bureau, is the resource center for state and local CDR Programs. Often mandated through state legislation, CDR programs use a common set of policies and protocols to identify and review cases at the state and/or local level through collaborations with medical examiners and coroners, law enforcement, medical professionals, social services, and public health representatives, among others. Forty-five states, including 1200 state and local teams, enter review findings into the Web-based data collection tool,19 the National CDR-Case Reporting System (CDR-CRS).20

SUID Case Registry

In 2009, the CDC developed a multistate surveillance system to improve knowledge about the circumstances and events surrounding SUID in the United States.21 This surveillance system, known as the SUID Case Registry, builds on existing CDR programs and infrastructure and enhances the ability of CDR programs to compile comprehensive, timely, and population-based data through the CDR-CRS. The CDC offers the participating states resources for increased staffing and capacity-building to improve data quality and timeliness. Both the SUID Case Registry and CDR rely on information from the death scene, medical examiner/coroner records, birth certificates, death certificates, and records from law enforcement, social services, and pediatric and obstetric medical encounters to understand circumstances surrounding these deaths. After the reviews, SUID information is integrated into the CDR-CRS. To differentiate unexplained deaths from accidental suffocations and allow states to reliably monitor category-specific SUID incidence and trends, the SUID Case Registry developed a classification system with a decision-making algorithm and standardized definitions.22

The Sudden Death in the Young Case Registry

After learning more about these successful platforms, the NHLBI initiated a collaboration with the CDC to develop the Sudden Death in the Young Case Registry, a prospective, population-based registry that builds on the NCFRP’s CDR-CRS Program and the CDC’s SUID Case Registry. The National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke at the NIH and the CDC’s Epilepsy Program became active partners as well, given their interest in understanding and preventing SUDEP. The SDY Case Registry benefits from the strengths of each collaborating agency: the CDC’s expertise in public health surveillance and the NIH’s expertise in research. The Michigan Public Health Institute (MPHI), which has been overseeing the NCFRP and CDR-CRS since 2002, was chosen as the data coordinating center, and the University of Michigan was selected as the Biorepository for the SDY Case Registry. By building on the platforms of the existing CDR-CRS and SUID surveillance systems, the SDY Case Registry eliminates the need for creating a new system, increases sustainability, and decreases implementation costs.

The SDY Case Registry has the following goals:

Describe the incidence of SDY in the United States through population-based surveillance.

Compile data from cases of SDY to create a resource of information and DNA samples for research into SDY.

Encourage standardized approaches to investigation, autopsy, and classification of SDY cases.

Develop partnerships between local, state, and federal stakeholders toward a common goal of understanding and preventing SDY.

Support families who have lost loved ones to SDY by providing resources on bereavement, DNA banking, and medical evaluation of surviving family members.

In creating the SDY Case Registry, a Steering Committee of NIH, CDC, and MPHI staff members sought guidance from an external committee of experts in adult and pediatric cardiology, neurology, epileptology, pathology, and advocacy. In addition, the Steering Committee convened an Autopsy Protocol Task Force of nationally recognized medical examiners, coroners, death investigators, and pathologists to develop standardized, comprehensive procedures for SDY Case Registry autopsies.

The SDY Case Registry was designed to expand the age range, scope, and geographic representation of the SUID Case Registry. The age range has been expanded to include all deaths in children from birth to <20 years of age. Although sudden cardiac death in the young often refers to deaths in individuals up to age 35 years, the statutes that govern the CDR system vary in age inclusion. As a result, the age range for the SDY Case Registry varies by jurisdiction, but is restricted to cases that are <20 years of age. The CDR-CRS has been expanded, with input from the external committee of experts, to include a module for SDY that includes additional questions related to cardiac and neurologic symptoms, activity/exercise, previous diagnoses, medications, treatments, seizures, family history, circumstances of the event, and resuscitation. The geographic reach of the SDY Case Registry has been expanded as well to fund 4 additional states and 2 jurisdictions that were not previously participating in the SUID Case Registry.

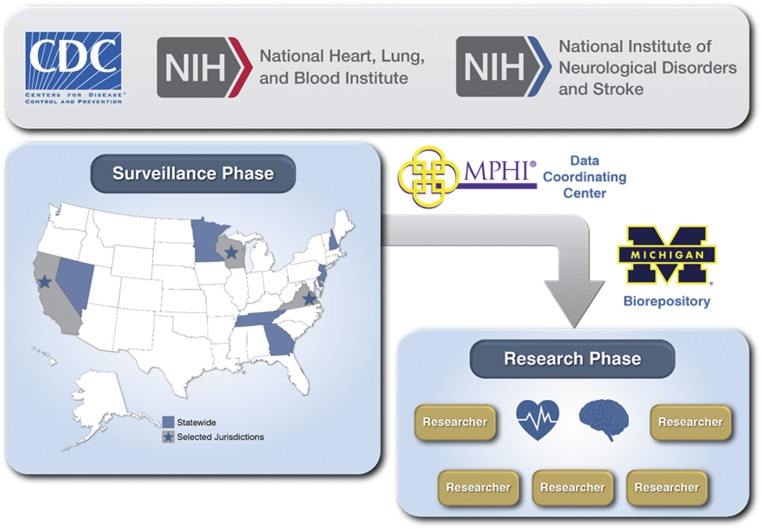

The organizational structure of the SDY Case Registry is displayed in Fig 1. The SDY Case Registry currently includes 10 states/jurisdictions whose surveillance activities are monitored by the CDC. MPHI houses the SDY Data Coordinating Center, which provides assistance to states/jurisdictions in compiling information into the CDR-CRS as well as improving case ascertainment, data completeness, timeliness of reporting, and recruitment for research. MPHI manages the SDY Case Registry’s Biorepository at the University of Michigan, where blood and/or tissue samples are processed to extract and store DNA. MPHI also provides technical assistance to states/jurisdictions in improving CDR through a separate HRSA grant. Investigators funded by the NIH to conduct approved studies are able to access deidentified information and DNA samples in cases that have consented to research.

FIGURE 1.

SDY Case Registry organizational structure. The CDC oversees the surveillance activities of the states/jurisdictions. Information is managed by the Data Coordinating Center at MPHI, and DNA samples are processed and stored at the University of Michigan Biorepository. After consent is obtained, data and DNA samples are available for NIH-approved research studies.

Definitions

For the purposes of the SDY Case Registry, “sudden” is defined as a death within 24 hours of the first symptom or death in the hospital after resuscitation from an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. “Unexpected” is defined as the death of someone who was believed to be in good health or had a stable, chronic condition, or had an acute illness that would not be expected to cause death.

Cases are included in the SDY Case Registry if the death presented as sudden and unexpected and the child was <20 years of age. Because the SDY Case Registry is population-based, the decedent must have been a resident of the jurisdiction or state to be eligible for inclusion. The SDY Case Registry contains not only deaths due to SUID, sudden cardiac death, and SUDEP, but also many other causes of SDY. However, cases are excluded if, during the autopsy and initial investigation, the death was attributed to (1) an accident in which the external cause was the obvious and only reason for the death; (2) homicide; (3) suicide; (4) accidental or intentional overdose of drugs, even if this caused cardiac or respiratory arrest, with no previous history of other possible chronic disease or autopsy findings suggestive of another cause; or (5) terminal illness in which the death was reasonably expected to occur within 6 months. The SDY Case Registry is a public health surveillance system and is therefore designed to be inclusive of as many community-based cases as possible. Specific populations of interest (eg, SUID, sudden cardiac death, and SUDEP, among others) will be examined through stratification during subsequent analyses.

Although some studies in sudden cardiac death use a window of 1 hour from symptom onset in the definition of “sudden”, the SDY Case Registry uses a window of 24 hours due to the high number of SDY cases that occur during sleep. Because deaths in children are rare events, the likelihood of comorbid conditions confounding the initial identification of symptoms related to SDY should be low, and a longer window could be used appropriately. In addition, the SDY Case Registry does not distinguish between witnessed and unwitnessed deaths.

One limitation of the SDY Case Registry is that it does not include information on survivors of cardiac arrest. The SDY Case Registry Steering Committee recognizes that survivors of cardiac arrest can provide important clues to understanding risk and protective factors that enhance individual survival. Excluding survivors is an operational limitation, because the platform on which the SDY Case Registry is built is the CDR-CRS system. Future efforts should explore ways to develop complementary systems to include this important population.

Guidance Documents/Tools

Several tools were created to facilitate data compilation from primary sources for the SDY Case Registry. The goal of these tools is to reduce variation across states/jurisdictions with different mandates, statutes, and practices. The SDY Autopsy Guidance and the Autopsy Summary Tool were created with input from the Autopsy Protocol Task Force. These documents provide a standardized, comprehensive approach to autopsy that focuses on medical conditions and other anatomic findings associated with SDY. The Field Investigation Guide and Family Interview Summary Tool is a series of questions that can be used by investigative teams to collect information that is relevant to determining cause of death as well as understanding SDY. The hard copy of the case report form and Web version CDR-CRS are used to compile all the information discussed at local CDR and advanced review meetings. Funded states/jurisdictions provide ongoing feedback to help optimize these tools in practice. In addition, these tools are available online,23 and external stakeholders are encouraged to adopt their use and provide feedback to the SDY Case Registry Steering Committee on their utility.

Consent

Although federal regulations do not require consent for research involving the deceased, state-level regulations vary. Given the sensitive and tragic nature of the sudden death of a young person, the SDY Case Registry Steering Committee consulted with the ethics team at the NIH Clinical Center as well as 2 external ethicists and decided to develop a process to obtain consent from the family/next of kin for several items separately: (1) using blood and/or tissue samples collected at autopsy for DNA extraction and subsequent SDY-related research; (2) allowing the information collected at CDR to be linked to the DNA sample; (3) allowing recontact by researchers for subsequent data gathering or research studies; (4) allowing recontact to return clinically actionable results; (5) allowing the deidentified DNA sample to be included in NIH biorepositories for future research outside of the SDY Case Registry; (6) performing diagnostic genetic testing; and (7) saving a DNA sample for the family to access for future genetic testing. At the time of consent, teams also provide resources to families for bereavement and medical evaluation for surviving family members.

Case Flow

The flow of cases through the SDY Case Registry is demonstrated in Fig 2. After a sudden death occurs, cases are identified primarily through medical examiners’ offices, and the inclusion and exclusion criteria are applied by the medical examiner (Supplemental Fig 4). Ideally, autopsies are performed in accordance with the standardized SDY Autopsy Guidance,24 and during the autopsy, pathologists collect and store a sample of blood for DNA extraction. They are also asked to save a liver and/or spleen sample, in the event that the blood sample does not yield sufficient DNA. If informed consent is obtained from the next-of-kin, the blood sample is shipped to the SDY Case Registry Biorepository at the University of Michigan for DNA extraction and storage.

FIGURE 2.

Case flow. This figure demonstrates the steps involved in identifying and describing a case for inclusion in the SDY Case Registry.

All cases are reviewed by CDR teams per their usual protocol. They use the CDR-CRS, which has been expanded with input from the external committee of experts to include a module of questions related to SDY. Eligible cases then undergo an adjudication process by a separate advanced review team comprised of local cardiologists, neurologists, and pathologists, among other subject matter experts. This adjudication process uses the SDY Case Registry categorization algorithm (Supplemental Fig 4) to classify cases. After cases have undergone final state-/jurisdiction-level review, the CDR-CRS information and DNA samples for which consent has been obtained for research are linked in a deidentified manner and are made available for use in research studies. Although cases are identified quickly through the medical examiner’s offices, the CDR and advanced review occur over several months; therefore, the time from identification of a case to final categorization varies and may take up to 1 year.

Invitae, a genetic testing company, partnered with MPHI and the Biorepository at the University of Michigan to offer in-kind diagnostic genetic testing to 900 autopsy-negative cases in the SDY Case Registry over a 3-year period using a panel of arrhythmia and cardiomyopathy genes. Results may help medical examiners and coroners determine the cause of death and may inform risks and approaches to cascade screening for surviving family members.

Technical Assistance and Evaluation

Funded teams have committed to performing population-based surveillance in their states/jurisdictions. Each team uses multiple methods to identify any possible SDY cases and works closely with their pathologists as well as vital records to ensure all cases have been identified. In addition, teams partner with their medical examiners and coroners to ensure understanding of the case definition and appropriate application of the inclusion/exclusion criteria at the time of death to identify cases promptly and conduct thorough autopsies. States that previously participated in the SUID Case Registry have been performing autopsies in 100% of SUID cases and are able to translate that experience to the SDY Case Registry.25 States/jurisdictions funded for the SDY Case Registry are expected to review all SDY cases through CDR in a timely manner and, as a requirement for funding, have demonstrated an ability to assemble advanced review teams with the appropriate expertise for adjudication and categorization of cases. To ensure timeliness, funded states/jurisdictions are also expected to enter and apply quality assurance protocols to the data within prespecified timelines after CDR and advanced review. Although the teams in each state/jurisdiction have a wealth of experience and familiarity with public health surveillance, consenting to save DNA for research, family banking, and diagnostic genetic testing are less familiar. Therefore, extensive efforts have been implemented by the SDY Case Registry staff, with guidance from the NIH, to build capacity and support teams in the funded states/jurisdictions in seeking consent from families.

To support these efforts, the SDY Case Registry staff perform technical assistance and evaluation to funded states/jurisdictions. Using the CDC’s established guidelines for evaluating surveillance systems,26 the SDY Case Registry is evaluated using 3 surveillance characteristics: case ascertainment, data completeness, and timeliness of reporting, which are integrated into the program’s logic model. The MPHI and the CDC use the logic model activities to guide technical assistance to the funded states/jurisdictions. These activities are detailed in work plans that are updated twice a year and discussed on bimonthly calls and during an annual reverse site visit, which brings all team members from funded states/jurisdictions together for in-depth training. Technical assistance helps to improve data quality and decrease variation among states/jurisdictions due to diversity of program structures.

Quarterly, the MPHI and CDC provide each state/jurisdiction with a data quality summary that summarizes (1) case ascertainment; (2) completeness of key variables; (3) timeliness of case identification, data entry, case review, and data quality assurance protocols; and (4) consent and biospecimen totals. In addition, states/jurisdictions report quarterly the number of cases identified, entered, reviewed, and consented. The self-report numbers are compared with those in the CDC/MPHI-generated reports and examined to determine areas and strategies for improvement. These work plans, data quality summaries, and self-reports guide discussion and problem solving on bimonthly, one-on-one calls. Additional technical assistance is provided to states/jurisdictions via bimonthly office hour calls, during which the CDC and MPHI staff are available to answer questions and facilitate discussion regarding any areas of concern. The CDC and the MPHI also host periodic, topic-driven group training calls.

Another element of technical assistance is site visits. During site visits, SDY Case Registry staff attend a CDR meeting and an advanced review meeting to observe implementation of the SDY Case Registry categorization algorithm and meet with local staff to discuss the program and brainstorm solutions to barriers.

Progress is shared internally via a monthly newsletter that highlights questions, successes, and prevention activities. An annual report on the progress of the SDY Case Registry is also provided to the federal sponsors and external partners.

Progress to Date

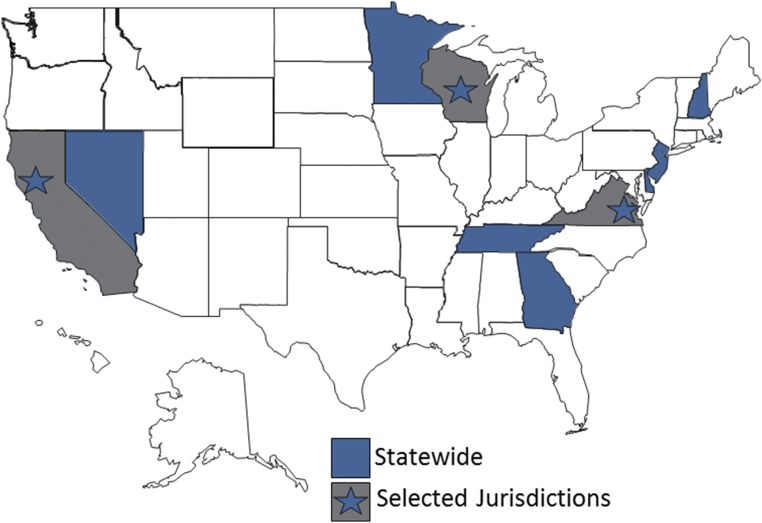

In January 2015, the SDY Case Registry launched surveillance with 9 states/jurisdictions. In September 2015, an additional state was funded. Current participants include the states of Georgia, Tennessee, New Jersey, Minnesota, Nevada, Delaware, and New Hampshire as well as the Tidewater region of Virginia, the city of San Francisco, and select counties in Wisconsin (Fig 3). Five of these states/jurisdictions have previous experience with case ascertainment, data compiling, and CDR as participants in the CDC’s SUID Case Registry.

FIGURE 3.

This map depicts the states/jurisdictions participating in surveillance for the SDY Case Registry: Delaware, Georgia, Minnesota, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, and Tennessee, as well as the city of San Francisco, the Tidewater region of Virginia, and 10 counties in Wisconsin.

From January 1, 2015 until October 15, 2016, 755 SDY cases were identified, and 562 cases have completed reviews and data cleaning. Of the completed cases, 90% have included an autopsy. DNA samples from 64 SDY cases in which consent was obtained for research, family DNA banking, or diagnostic genetic testing have been stored in the Biorepository.

In April 2016, the NHLBI funded 3 research teams representing Northwestern University at Chicago, Vanderbilt University, and the University of Utah to work collaboratively with each other, NHLBI staff, SDY Case Registry states/jurisdictions, and the Steering Committee to use the data and DNA samples in the SDY Case Registry to explore the causes and characteristics of cases of sudden cardiac death in the young. A multidisciplinary team of researchers has also been funded by the National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke to study SUDEP through the Center for SUDEP Research.27 In the future, data and DNA samples will be made available to other members of the scientific community for additional analysis through investigator-initiated grant applications to the NIH.

Conclusions

The SDY Case Registry was built on the existing successful platforms of the CDR-CRS system and the SUID Case Registry. It supports population-based surveillance of SDY to inform our understanding of incidence. It also creates a research resource whereby information about cases can be linked to DNA samples and used to explore the characteristics of SDY cases. The SDY Case Registry will facilitate a better understanding of the incidence and causes of SDY through collaborative efforts at the local, state, and federal levels to enable the development of evidence-based strategies for prevention.

Acknowledgments

We thank the many contributors to the development and ongoing optimization of the SDY Case Registry. We thank the HRSA Maternal and Child Health Bureau for their longstanding support of the CDR programs. We thank the external committee of experts and the Autopsy Protocol Task Force for their guidance and input. We thank the ethicists at the NIH Clinical Center as well as Amy McGuire and Sonia Suter, who helped us explore and refine our strategy for consent. We thank the SDY Case Registry teams in each state/jurisdiction for their tireless efforts at gathering high-quality information and the researchers who will analyze that information. Most of all, we thank the decedents and their families for their willingness to share their stories with us so that we may learn from them.

External Committee of Experts: Dr Lisa Bateman, Dr Robert Campbell, Dr Sumeet Chugh, Laura Crandall, Dr Sam Gulino, Gardiner Lapham, Martha Lopez-Anderson, Dr Kurt Nolte, Dr David Thurman, and Dr Victoria Vetter. Autopsy Protocol Task Force: Dr Karen Chancellor, Dr Beau Clark, Dr Tim Corden, Kim Fallon, Dr Corinne Fligner, Dr Sam Gulino, Dr Wendy Gunther, Dr Jennifer Hammers, Dr Owen Middleton, and Dr Michael Murphy.

Glossary

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CDR

Child Death Review

- CDR-CRS

Child Death Review Case Reporting System

- HRSA

Health Resources and Services Administration

- MPHI

Michigan Public Health Institute

- NCFRP

National Center for Fatality Review and Prevention

- NHLBI

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

- NIH

National Institutes of Health

- SDY

sudden death in the young

- SUDEP

sudden unexpected death in epilepsy

- SUID

sudden unexpected infant death

Footnotes

Dr Burns conceptualized the paper, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Drs Camperlengo, Shapiro-Mendoza, and Kaltman, Ms Covington, Ms Kobau, Ms Lambert, and Ms MacLeod contributed to the conception and design and made critical suggestions and revisions to the manuscript; Ms Bienemann, Ms Cottengim, Ms Dykstra, Ms Faulkner, Drs Parks, Russel, Tian, and Whittemore, Ms Rosenberg, and Ms Shaw contributed to the design of the manuscript, critically reviewed the manuscript, and provided important intellectual content; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: The Sudden Death in the Young Case Registry is supported by funds from the National Institutes of Health (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke) as well as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose. The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not reflect official positions of the National Institutes of Health or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Healthy People 2020. Available at: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/maternal-infant-and-child-health/objectives. Accessed November 4, 2016

- 2.Matthews TJ, MacDorman MF, Thoma ME. Infant mortality statistics from the 2013 period linked birth/infant death data set. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64(9):1–30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilders R. Cardiac ion channelopathies and the sudden infant death syndrome. ISRN Cardiol. 2012;2012:846171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Driscoll DJ, Edwards WD. Sudden unexpected death in children and adolescents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1985;5(6 suppl):118B–121B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maron BJ, Gohman TE, Aeppli D. Prevalence of sudden cardiac death during competitive sports activities in Minnesota high school athletes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32(7):1881–1884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chugh SS, Reinier K, Balaji S, et al. Population-based analysis of sudden death in children: The Oregon Sudden Unexpected Death Study. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6(11):1618–1622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maron BJ, Doerer JJ, Haas TS, Tierney DM, Mueller FO. Sudden deaths in young competitive athletes: analysis of 1866 deaths in the United States, 1980-2006. Circulation. 2009;119(8):1085–1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maron BJ, Haas TS, Ahluwalia A, Rutten-Ramos SC. Incidence of cardiovascular sudden deaths in Minnesota high school athletes. Heart Rhythm. 2013;10(3):374–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pilmer CM, Kirsh JA, Hildebrandt D, Krahn AD, Gow RM. Sudden cardiac death in children and adolescents between 1 and 19 years of age. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11(2):239–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harmon KG, Asif IM, Klossner D, Drezner JA. Incidence of sudden cardiac death in National Collegiate Athletic Association athletes. Circulation. 2011;123(15):1594–1600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maron BJ, Friedman RA, Kligfield P, et al. ; American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology, Advocacy Coordinating Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology, Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research, and American College of Cardiology . Assessment of the 12-lead ECG as a screening test for detection of cardiovascular disease in healthy general populations of young people (12-25 Years of Age): a scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology. Circulation. 2014;130(15):1303–1334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thurman DJ, Hesdorffer DC, French JA. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy: assessing the public health burden. Epilepsia. 2014;55(10):1479–1485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Devinsky O. Sudden, unexpected death in epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(19):1801–1811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaltman JR, Thompson PD, Lantos J, et al. Screening for sudden cardiac death in the young: report from a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute working group. Circulation. 2011;123(17):1911–1918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Institute of Medicine, Committee on the Treatment of Cardiac Arrest Strategies to Improve Cardiac Arrest Survival: A Time to Act. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2015 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Institute of Medicine, Committee on the Public Health Dimensions of the Epilepsies Epilepsy Across the Spectrum: Promoting Health and Understanding. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2012 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Center for the Review and Prevention of Child Deaths CDR principles. Available at: www.childdeathreview.org/cdr-process/cdr-principles/. Accessed May 23, 2016

- 18.National Center for the Review and Prevention of Child Deaths Child Death Review. Available at: www.childdeathreview.org/. Accessed May 23, 2016

- 19.Covington TM. The US National Child Death Review Case Reporting System. Inj Prev. 2011;17(suppl 1):i34–i37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The National Center for the Review and Prevention of Child Deaths State Profile Database U.S. CDR Programs. Status of CDR in the United States reports. Available at: www.childdeathreview.org/cdr-programs/u-s-cdr-programs/. Accessed May 23, 2016

- 21.Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Camperlengo LT, Kim SY, Covington T. The sudden unexpected infant death case registry: a method to improve surveillance. Pediatrics. 2012;129(2). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/129/2/e486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Camperlengo L, Ludvigsen R, et al. Classification system for the Sudden Unexpected Infant Death Case Registry and its application. Pediatrics. 2014;134(1). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/134/1/e210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Michigan Public Health Institute: The Sudden Death in the Young Case Registry 2017. www.sdyregistry.org

- 24.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Frequently asked questions about the Sudden Death in the Young Case Registry. Available at: www.nhlbi.nih.gov/news/spotlight/fact-sheet/frequently-asked-questions-about-sudden-death-young-case-registry. Accessed June 13, 2016

- 25.Erck Lambert AB, Parks SE, Camperlengo L, et al. Death scene investigation and autopsy practices in sudden unexpected infant deaths. J Pediatr. 2016;174:84–90.e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guidelines Working Group Updated guidelines for evaluating public health surveillance systems. Recommendations from the Guidelines Working Group. Available at: www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5013a1.htm. Accessed June 14, 2016 [PubMed]

- 27.The Center for SUDEP Research. Available at: http://csr.case.edu/index.php/Main_Page. Accessed June 13, 2016