Abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES:

Psychological symptoms can be associated with celiac disease; however, this association has not been studied prospectively in a pediatric cohort. We examined mother report of psychological functioning in children persistently positive for tissue transglutaminase autoantibodies (tTGA), defined as celiac disease autoimmunity (CDA), compared with children without CDA in a screening population of genetically at-risk children. We also investigated differences in psychological symptoms based on mothers’ awareness of their child’s CDA status.

METHODS:

The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young study followed 8676 children to identify triggers of type 1 diabetes and celiac disease. Children were tested for tTGA beginning at 2 years of age. The Achenbach Child Behavior Checklist assessed child psychological functioning at 3.5 and 4.5 years of age.

RESULTS:

At 3.5 years, 66 mothers unaware their child had CDA reported more child anxiety and depression, aggressive behavior, and sleep problems than 3651 mothers of children without CDA (all Ps ≤ .03). Unaware-CDA mothers also reported more child anxiety and depression, withdrawn behavior, aggressive behavior, and sleep problems than 440 mothers aware of their child’s CDA status (all Ps ≤.04). At 4.5 years, there were no differences.

CONCLUSIONS:

In 3.5-year-old children, CDA is associated with increased reports of child depression and anxiety, aggressive behavior, and sleep problems when mothers are unaware of their child’s CDA status. Mothers’ knowledge of their child’s CDA status is associated with fewer reports of psychological symptoms, suggesting that awareness of the child’s tTGA test results affects reporting of symptoms.

This study highlights that children with celiac disease autoimmunity may exhibit subtle psychological symptoms before parents are aware of their child’s celiac autoimmunity.

What’s Known on This Subject:

Celiac disease may be associated with a variety of psychological symptoms in children, such as depression and attentional problems. Prospective studies in young children examining this relationship do not exist.

What This Study Adds:

Celiac disease autoimmunity (CDA) is associated with increased parent report of child depression and anxiety, aggression, and sleep problems when mothers are unaware of their child’s CDA status. Knowledge of CDA status is associated with fewer reports of psychological symptoms.

Celiac disease may present with a wide range of clinical symptoms, including gastrointestinal difficulties (eg, loose stools, abdominal discomfort) and extraintestinal symptoms (eg, poor growth, anemia).1,2 The condition may also cause psychological manifestations such as depression, cognitive impairment, sleep problems, and attention deficits.3–5 Although the etiology remains to be confirmed, psychological symptoms may be the result of nutrient malabsorption or increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines affecting mental and emotional functioning.6

For children with celiac disease autoimmunity (CDA), defined as being persistently positive for tissue transglutaminase autoantibodies (tTGA), parent report of physical symptoms of celiac disease is age dependent.7 We previously reported that when unaware of their child’s CDA status, parents of 2- and 3-year-old children were more likely to report physical symptoms related to celiac disease at the time of CDA seroconversion than parents of same age children without CDA. However, there was no difference in parent report of physical symptoms in CDA versus no CDA 4-year-old children. We also found that parents reported more physical symptoms associated with celiac disease after they were informed the child had tested positive for tTGA, suggesting that awareness of the child’s tTGA test results affects the reporting of symptoms.7 To our knowledge, no studies have examined the psychological symptoms associated with celiac disease in children screened for tTGA positivity in a similar manner.

The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) is an international study investigating environmental factors associated with type 1 diabetes (T1D) and celiac disease.7,8 TEDDY children are at elevated genetic risk for T1D and celiac disease and are prospectively followed from birth up to 15 years of age with an extensive array of biologic, psychological, and environmental measures. This longitudinal study offered the opportunity to prospectively examine maternal reports of psychological functioning in preschool-aged children with CDA, when mothers were unaware or aware of the child’s CDA status.

Methods

The TEDDY Study

TEDDY is a natural history study designed to identify environmental triggers of T1D autoimmunity or onset and celiac disease in genetically at-risk children. TEDDY children were identified at 6 centers (United States: Colorado, Georgia/Florida, and Washington; Finland, Germany, and Sweden).9 Infants were screened at birth via HLA antigen genotyping, and families of HLA antigen-eligible children were enrolled before 4.5 months of age. Families were recruited from the general population and from a subset of those with a first-degree relative (FDR) with T1D. After enrollment, families participate in clinic visits every 3 months during the first 4 years of the child’s life and every 6 months thereafter, for those without islet autoantibodies, up to the age of 15 years or until the development of T1D. Children with islet autoantibodies continued to attend quarterly visits. A variety of data are collected at study visits, including biological samples (eg, blood, saliva), records of the child’s diet, illnesses, and life stressors and parent report of child psychosocial functioning. The study was approved by each center’s institutional review board and is regularly monitored by an expert external evaluation committee.

Screening for tTGA

TEDDY children are screened annually for tTGA levels beginning at 2 years of age. Samples are analyzed at 2 laboratories and classified as positive or negative as previously described.7,10 Children testing positive for tTGA at the annual screen had their previous serum samples analyzed to determine time of first positive sample. If the annual tTGA sample was positive, participants were retested at the next TEDDY study visit. Children who were tTGA positive for 2 consecutive samples were defined as having CDA. Parents were notified of positive tTGA results after the first positive result. At Colorado, Washington, and Germany sites, parents received a phone call and a follow-up letter. At the Georgia/Florida site, parents received a letter. In Finland, parents received a phone call and a follow-up discussion at the next study visit. In Sweden, parents were notified at their next study visit.

At all sites, parents of CDA children were given a celiac disease information sheet describing the disease, symptoms, and treatment. Families were told to consult with a local pediatric gastroenterologist for additional evaluation and were given information about family risk for celiac disease. The decision whether and when to undergo an intestinal biopsy to confirm a diagnosis of celiac disease was made by the family and their health care provider; intestinal biopsy was not provided as part of the TEDDY protocol. Consequently, not all TEDDY CDA children had confirmed celiac disease. Our previous work with the TEDDY cohort indicated that of CDA children whose families chose to pursue endoscopy, 84% of children are confirmed to have celiac disease.7

Study Population

Of 8676 participants who initially joined the TEDDY study, 4985 completed the psychosocial questionnaire when the child was aged between 3 and 4 years (3.5-year questionnaire) and 4562 when child was aged between 4 and 5 years (4.5-year questionnaire). Of these participating children, 677 (3.5-year questionnaire) and 687 (4.5-year questionnaire) were excluded because they tested positive for islet autoantibodies, possibly influencing parent report of their child’s psychological functioning, leaving 4308 and 3875 subjects, respectively.

At the time of the 3.5-year questionnaire, 3651 out of 4308 were children without CDA (no-CDA group), 440 out of 4308 were mothers who were already aware their child had CDA (aware-CDA group), and 66 out of 4308 were mothers who were unaware their child was developing CDA (unaware-CDA group). Those excluded from the analyses included 89 out of 4308 children who developed CDA between 3 and 4 years of age but after the questionnaire was completed, 3 out of 4308 children for whom it was unclear whether mother was aware of the child’s CDA status, and 59 out of 4308 who had unconfirmed tTGA results. For the aware-CDA group, the child tested positive for tTGA at or before their annual screen at 3.0 years of age, and notification occurred before the 3.5-year questionnaire was completed. Of the children developing CDA between 3 and 4 years of age (n = 158), 66 out of 158 mothers were in the unaware-CDA group. This occurred because of either a first positive tTGA test at the same study visit as the psychological questionnaire was completed or a positive test result at the next annual screen (4 years of age) that led to retrospective sampling and determination that the first positive tTGA test occurred before completion of the 3.5-year questionnaire.

At the time of the 4.5-year questionnaire, 3139 out of 3875 were in the no-CDA group and 561 out of 3875 were in the aware-CDA group. Only 40 out of 3875 children were classified in the unaware-CDA group. Of the children who were excluded, 83 out of 3875 had unconfirmed tTGA results and 52 out of 3875 developed CDA after the completion of the psychological questionnaire. Data used were current as of June 30, 2015, at which time the entire TEDDY cohort had completed the 4.5-year visit and were at least 5 years of age.

Child Psychological Functioning

Caregivers completed the Achenbach Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL),11 a well-validated questionnaire designed to measure behavioral and emotional functioning in preschoolers (1.5 to 5 years old) in research and clinical settings. CBCL data were collected at 3.5- and 4.5-year-old visits. The CBCL includes 99 statements describing a variety of child behaviors (eg, “Cries a lot,” “Gets into everything”). Parents choose a response (ie, “Not true” = 0, “Somewhat or sometimes true” = 1, “Very true or often true” = 2) to indicate how accurate each statement is for their child in the past 2 months. Seven empirically derived subscale scores (Emotionally Reactive, Anxious/Depressed, Somatic Complaints, Withdrawn, Sleep Problems, Attention Problems, Aggressive Behavior) and 2 composite scores (Internalizing, Externalizing) are then calculated. Higher scores suggest more difficulties. The CBCL has demonstrated good reliability in past studies.11 It has been adapted for use in numerous countries, including TEDDY study sites.12,13 The CBCL can be used in clinical settings as a screen to identify children with possible adjustment problems,11 although that was not its purpose in the current investigation. As recommended for research purposes, raw scores were used in analyses to reduce floor effects.11 In the current sample, >90% of parents who completed the CBCL were mothers.

Statistical Analysis

Multiple regression was used to identify factors associated with CDA (country of residence, sex, HLA antigen-DQ status [DQ8, DQ 2/8, or DQ 2/2], and whether the child had an FDR with celiac disease) (Table 1) and CBCL scores (country, maternal age at the child’s birth, sex, and whether the child had an FDR with celiac disease) that needed to be controlled in subsequent analyses.

TABLE 1.

Demographic Characteristics Within Status Groups Defined by Child’s Seroconversion to CDA, Mother’s Awareness of CDA Status, and Age of Seroconversion

| Age of Child and Mother Aware of CDA Status | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No CDA ≤5 y (N = 3139) | Aware of CDA ≤3 y (N = 440) | Unaware of CDA >3 to ≤4 y (N = 66) | Unaware of CDA >4 to ≤5 y (N = 40) | |||||

| CD Risk Factor | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % |

| Country | ||||||||

| US | 1163 | 37.1 | 127 | 28.9 | 23 | 34.9 | 17 | 42.5 |

| Finland | 734 | 23.4 | 86 | 19.6 | 15 | 22.7 | 12 | 30.0 |

| Germany | 160 | 5.1 | 18 | 4.1 | 5 | 7.6 | 1 | 2.5 |

| Sweden | 1082 | 34.5 | 209 | 47.5 | 23 | 34.9 | 10 | 25.0 |

| HLA-DQ | ||||||||

| DQ8 | 1422 | 45.5 | 55 | 12.6 | 21 | 31.8 | 8 | 20.0 |

| DQ2/8 | 1215 | 38.9 | 143 | 32.7 | 26 | 39.4 | 19 | 47.5 |

| DQ2/2 | 486 | 15.6 | 240 | 54.8 | 19 | 28.8 | 13 | 32.5 |

| FDR with CD | ||||||||

| No | 3034 | 97.1 | 397 | 90.6 | 60 | 90.9 | 40 | 100 |

| Yes | 91 | 2.9 | 41 | 9.4 | 6 | 9.1 | 0 | 0 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 1660 | 52.9 | 183 | 41.6 | 33 | 50.0 | 13 | 32.5 |

| Female | 1479 | 47.1 | 257 | 58.4 | 33 | 50.0 | 27 | 67.5 |

| Maternal age at birth | ||||||||

| <25 y | 282 | 9.0 | 39 | 8.9 | 7 | 10.6 | 2 | 5.0 |

| 25–35 y | 2265 | 72.2 | 329 | 74.8 | 46 | 69.7 | 31 | 77.5 |

| >35 y | 592 | 18.9 | 72 | 16.4 | 13 | 19.7 | 7 | 17.5 |

CD, celiac disease. DQ2 denotes DQA1*0501-DQB1*02; DQ8 denotes DQA1*0301-DQB1*0302.

Multiple linear regression was used to determine whether CBCL scores in the unaware-CDA group differed from CBCL scores in the no-CDA group and the aware-CDA group. These analyses were repeated for the 4.5-year time point. In all analyses, other factors associated with CDA and CBCL scores (country, sex, HLA antigen-DQ status, maternal age at the child’s birth, and whether the child had an FDR with celiac disease) were controlled. P values ≤.05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

Table 2 provides CBCL scores for 3.5-year-old children in the no-CDA, unaware-CDA, and aware-CDA groups. Within the aware-CDA group, there were children with biopsy-confirmed celiac disease (n = 109 at 3.5 years and n = 154 at 4.5 years), children with a biopsy that did not confirm celiac disease (n = 24 at 3.5 years and n = 30 at 4.5 years), and children who had not yet undergone a biopsy (n = 307 at 3.5 years and n = 377 at 4.5 years). There were no significant differences in CBCL scores between these groups; therefore, they were combined into 1 aware-CDA group in all analyses.

TABLE 2.

CBCL Scores Reported by Mothers of No-CDA Children, Unaware-CDA Mothers, and Aware-CDA Mothers at 3.5 y of Age

| CBCL Score | No-CDA (N = 3651) | Unaware-CDA (N = 66) | Aware-CDA (N = 440) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Internalizing Composite | 5.72 (5.09) | 6.80 (6.75) | 5.42 (4.86) |

| Anxious/Depressed | 1.26 (1.57)a | 1.82 (2.58)a | 1.01 (1.34)a |

| Emotionally Reactive | 1.86 (1.94) | 2.05 (2.41) | 1.87 (2.06) |

| Somatic Complaints | 1.63 (1.78) | 1.77 (1.81) | 1.71 (1.77) |

| Withdrawn | 0.96 (1.32) | 1.17 (1.40)a | 0.83 (1.22)a |

| Externalizing Composite | 9.54 (6.91)a | 11.21 (8.04)a | 8.89 (6.64)a |

| Attention Problems | 1.55 (1.59) | 1.65 (1.70) | 1.38 (1.44) |

| Aggressive Behavior | 7.99 (5.80)a | 9.56 (6.67)a | 7.51 (5.62)a |

| Sleep Problems | 2.59 (2.33)a | 3.32 (2.64)a | 2.42 (2.21)a |

Unaware-CDA group differed from the no-CDA group, the aware-CDA group, or both.

Maternal Reports of Child Psychological Functioning in Unaware-CDA Group and No-CDA Group

At 3.5 years of age and after adjustment for other factors associated with CDA and CBCL scores, mothers in the unaware-CDA group (n = 66) reported more symptoms on the CBCL Anxious/Depressed (P = .003), Aggressive Behavior (P = .03), and Sleep Problems (P = .02) subscales and the Externalizing Composite score (P = .04) compared with mothers in the no-CDA group (n = 3651) (Table 2). At 4.5 years of age, there were no significant differences between these groups (data not shown).

Maternal Reports of Child Psychological Functioning in Unaware-CDA Group and Aware-CDA Group

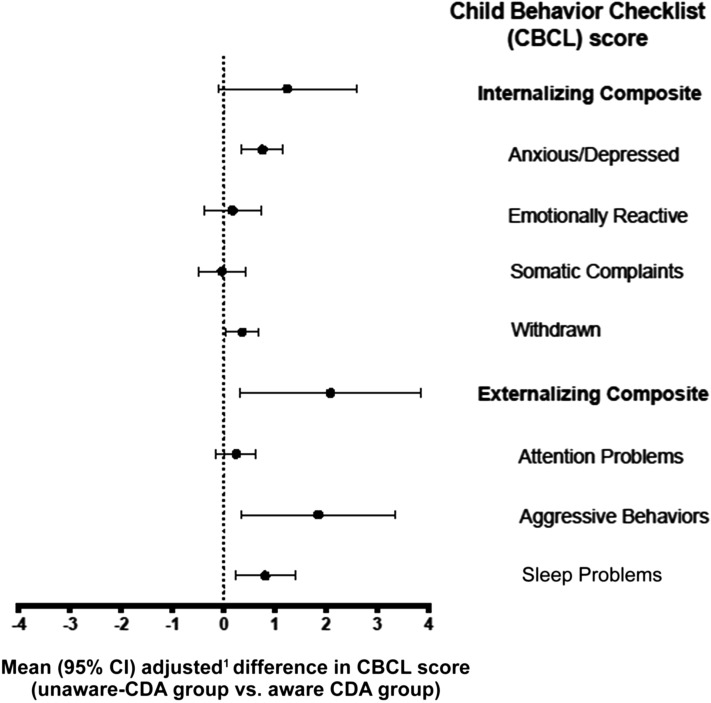

At 3.5 years, the unaware-CDA group mothers reported more symptoms on the CBCL Anxious/Depressed (P < .001), Withdrawn (P = .04), Aggressive Behavior (P = .02), and Sleep Problems (P = .007) and the Externalizing Composite score (P = .02) subscales compared with mothers in the aware-CDA group (n = 440) (Table 2 and Fig 1). At 4.5 years of age, there were no significant differences (data not shown).

FIGURE 1.

Difference in CBCL scores between the unaware-CDA group and aware-CDA group. Positive values indicate that the unaware-CDA group had higher CBCL scores. 1Difference in CBCL score was adjusted for country of birth, HLA antigen risk group, sex, FDR with celiac disease, and maternal age at birth.

Maternal Reports of Child Psychological Functioning in Aware-CDA Group and No-CDA Group

The CBCL responses of mothers in the aware-CDA group were not significantly different from those of mothers in the no-CDA group (n = 3651) with 1 exception: Aware-CDA mothers reported significantly fewer problems on the Anxious/Depressed subscale (P = .03). At 4.5 years of age there were no significant differences (data not shown).

Impact of Gluten-Free Diet and tTGA Titer Levels

We conducted additional analyses to examine the role of gluten-free diet and tTGA titer levels on differences in CDA groups at 3.5 years. In the no-CDA group, 1.1% (n = 41) had initiated a gluten-free diet. In the 66 mothers in the unaware-CDA group, none had initiated a gluten-free diet. Among the 3 subgroups of aware-CDA mothers, almost all (n = 103, 94.5%) of aware-CDA children with biopsy-confirmed celiac disease were on a gluten-free diet, whereas the 2 other aware-CDA subgroups had much lower rates of following a gluten-free diet (aware-CDA with biopsy that failed to confirm celiac disease: n = 3, 12.5%; aware-CDA with no biopsy: n = 20, 6.5%). No differences were found in CBCL scores for aware-CDA mothers based on whether the child was on a gluten-free diet. Similarly, no association was found between CBCL scores and tTGA levels at 3.5 years.

Discussion

The current study prospectively examined psychological manifestations of CDA in young children as a function of mothers’ awareness of their child’s CDA status. At 3.5 years, mothers who were unaware of their child’s CDA reported more child anxious and depressed symptoms, aggressive behaviors, and sleep problems than mothers of children without CDA. These results support previous studies documenting depression, anxiety, and sleep problems as possible manifestations of celiac disease.1,3,5 The current study provides even greater support for this association because mothers were unaware of their child’s CDA status at the time of symptom reporting. Interestingly, when mothers are aware of their child’s CDA, they report levels of psychological symptoms that are similar to, or lower than, mothers of children with no CDA. However, it is important to note that group means were in all cases below clinical cutoffs on the CBCL, suggesting that these are subclinical differences. Furthermore, our findings did not support these relationships between CDA and psychological symptoms in children at 4.5 years of age.

Parent awareness of the child’s CDA had a strong influence on parent reports of psychological symptoms at 3.5 years of age, which mirrors our previous study focusing on physical symptom reporting. In our previous work, awareness that a child has CDA is associated with more parent-reported child physical symptoms.7 We have now shown that awareness of a child’s CDA is associated with decreased mother reports of child psychological symptoms. Perhaps the knowledge of the child’s CDA increases a parent’s sensitivity to physical discomforts of their child while providing an alternative explanation for any psychological symptoms the child exhibits. Given that the initiation of a gluten-free diet and the level of tTGA titers may affect a child’s symptoms related to CDA, we also examined these variables. Neither gluten-free diet (present almost exclusively in children with biopsy-confirmed celiac disease) nor tTGA levels were associated with psychological functioning. This finding was unexpected, because both factors can be related to celiac disease symptoms (eg, gluten-free diet can ameliorate symptoms). Imprecise data related to duration of gluten-free diet in the children with celiac disease may have contributed to this lack of an association.

In terms of the relationship between CDA and psychological functioning, our findings suggest that the age of the child is very important. Parents who were unaware of their child’s CDA reported more child psychological symptoms than parents of children without CDA when children were 3.5 years of age; this finding was not observed among parents of children 4.5 years of age. This pattern of results is remarkably similar to that reported previously for physical symptoms.7 In this previous study, parents of 2- and 3-year-old children, but not 4-year-old children, were more likely to report child physical symptoms in children with CDA than in children without CDA. These differences suggest that the presentation of CDA depends on the age of the child, and we postulate several explanations for this finding. First, perhaps children developing CDA at a younger age have more significant disease pathology, yielding more noticeable symptoms, both psychological and physical. Second, younger children, who have less developed verbal skills, may be more likely to express physical discomfort (eg, gastrointestinal symptoms) through emotional symptoms, such as crying or appearing depressed, than older children. In fact, child development research supports the assertion that children respond differently to internal states as they develop, with younger children more often expressing internal states such as pain with behaviors rather than using verbal explanations.14 By 4 to 5 years of age, children are able to more effectively verbalize physical discomfort to their parents and are less likely to manifest their discomfort through psychological symptoms.15 Third, older children may be better able to acclimate to mild physical distress associated with celiac disease than younger children, accepting celiac symptoms as “normal” given their chronicity and, as a consequence, report fewer psychological and physical symptoms.16

The current study has several strengths, including the prospective design and the inclusion of a large, international cohort of children. There were also limitations. Among our 4.5-year-old children, very few mothers were unaware of their child’s CDA status, limiting our power to detect differences between groups. Given our cohort of children genetically at risk for T1D and celiac disease, findings may not be applicable to a more general population. We focused on CDA, and not celiac disease per se, because many of the children with CDA had not undergone endoscopic testing at the time of analysis. Study results may vary if only biopsy-confirmed cases of celiac disease are included, although we did not find differences in psychological functioning between children with biopsy-confirmed celiac and those without endoscopic testing. CDA may represent an earlier stage of the disease with less impact on the small intestine and fewer clinical manifestations.16 However, it is important to reiterate that within TEDDY, the majority (>80%) of children with CDA who underwent an intestinal biopsy have confirmed celiac disease.7 In fact, CDA may be a more objective measure of disease process because serological testing is not dependent on inherent differences in endoscopic methods (eg, endoscopic sample cutoff differences, human variation in biopsy interpretation).

Conclusions

This is the first prospective study to demonstrate an association between CDA and mother-reported subclinical psychological symptoms in very young children before mothers are aware of their child’s CDA status. These findings are particularly noteworthy because mothers were unaware of their child’s CDA status, eliminating the potential bias of retrospective reporting. Although pediatricians are probably cognizant of the importance tTGA screening when children present with more typical physical symptoms of celiac disease, such as gastrointestinal upset, this study suggests that providers should also attend to psychological symptoms such as anxiety and depression, aggressive behavior, and sleep problems. In fact, pediatricians may want to recommend tTGA testing in children <4 years of age with a family history of celiac disease if parents report child psychological symptoms.

Acknowledgment

We gratefully acknowledge the TEDDY Study Group (see Appendix).

Glossary

- CBCL

Achenbach Child Behavior Checklist

- CDA

celiac disease autoimmunity

- FDR

first-degree relative

- T1D

type 1 diabetes

- TEDDY

The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young

- tTGA

tissue transglutaminase autoantibodies

Appendix: The Teddy Study Group

Colorado Clinical Center

Marian Rewers, MD, PhD, PI,1,4–6,10,11 Kimberly Bautista,12 Judith Baxter,9,10,12,15 Ruth Bedoy,2 Daniel Felipe-Morales, Brigitte I. Frohnert, MD,2,14 Patricia Gesualdo,2,6,12,14,15 Michelle Hoffman,12–14 Rachel Karban,12 Edwin Liu, MD,13 Jill Norris, PhD,2,3,12 Adela Samper-Imaz, Andrea Steck, MD,3,14 Kathleen Waugh,6,7,12,15 and Hali Wright.12 University of Colorado, Anschutz Medical Campus, Barbara Davis Center for Childhood Diabetes.

Georgia/Florida Clinical Center

Jin-Xiong She, PhD, PI,1,3,4,11 Desmond Schatz, MD,*4,5,7,8 Diane Hopkins,12 Leigh Steed,12–15 Jamie Thomas,*6,12 Janey Adams,*12 Katherine Silvis,2 Michael Haller, MD,*14 Melissa Gardiner, Richard McIndoe, PhD, Ashok Sharma, Joshua Williams, Gabriela Young, Stephen W. Anderson, MD,† and Laura Jacobsen, MD.*14 Center for Biotechnology and Genomic Medicine, Augusta University. *University of Florida; †Pediatric Endocrine Associates, Atlanta.

Germany Clinical Center

Anette G. Ziegler, MD, PI,1,3,4,11 Andreas Beyerlein, PhD,2 Ezio Bonifacio PhD,*5 Michael Hummel, MD,13 Sandra Hummel, PhD,2 Kristina Foterek,†2 Nicole Janz, Mathilde Kersting, PhD,†2 Annette Knopff,7 Sibylle Koletzko, MD,‡13 Claudia Peplow,12 Roswith Roth, PhD,9 Marlon Scholz, Joanna Stock,9,12 Elisabeth Strauss,12,14 Katharina Warncke, MD,14 Lorena Wendel, and Christiane Winkler, PhD.2,12,15 Forschergruppe Diabetes e.V. and Institute of Diabetes Research, Helmholtz Zentrum München, and Klinikum rechts der Isar, Technische Universität München. *Center for Regenerative Therapies, TU Dresden; †Research Institute for Child Nutrition, Dortmund; ‡Dr. von Hauner Children’s Hospital, Department of Gastroenterology, Ludwig Maximillians University Munich.

Finland Clinical Center

Jorma Toppari, MD, PhD, PI,*†1,4,11,14 Olli G. Simell, MD, PhD,*†1,4,11,13 Annika Adamsson, PhD,†12 Suvi Ahonen,‡§‖ Heikki Hyöty, MD, PhD,‡§6 Jorma Ilonen, MD, PhD,*¶3 Sanna Jokipuu,† Tiina Kallio,† Leena Karlsson,† Miia Kähönen,‖# Mikael Knip, MD, PhD,‡§5 Lea Kovanen,‡§‖ Mirva Koreasalo,‡§¶2 Kalle Kurppa, MD, PhD,‡§13 Tiina Latva-aho,** Maria Lönnrot, MD, PhD,‡§6 Elina Mäntymäki,† Katja Multasuo,** Juha Mykkänen, PhD,*3 Tiina Niininen,‡§12 Sari Niinistö,§¶ Mia Nyblom,‡§ Petra Rajala,† Jenna Rautanen,§¶ Anne Riikonen,‡§¶ Mika Riikonen,† Jenni Rouhiainen,† Minna Romo,† Tuula Simell, PhD, Ville Simell,*†13 Maija Sjöberg,*†12,14 Aino Stenius,**12 Maria Leppänen,† Sini Vainionpää,† Eeva Varjonen,*†12 Riitta Veijola, MD, PhD,14 Suvi M. Virtanen, MD, PhD,‡§¶2 Mari Vähä-Mäkilä,† Mari Åkerlund,‡§¶ and Katri Lindfors, PhD.‡13 *University of Turku; †Turku University Hospital, Hospital District of Southwest Finland; ‡University of Tampere; §Tampere University Hospital, ‖Oulu University Hospital; ¶National Institute for Health and Welfare, Finland; #University of Kuopio; **University of Oulu.

Sweden Clinical Center

Åke Lernmark, PhD, PI,1,3–6,8,10,11,15 Daniel Agardh, MD, PhD,13 Carin Andrén Aronsson,2,13 Maria Ask, Jenny Bremer, Ulla-Marie Carlsson, Corrado Cilio, PhD, MD,5 Emelie Ericson-Hallström, Lina Fransson, Thomas Gard, Joanna Gerardsson, Rasmus Bennet, Monica Hansen, Gertie Hansson,12 Cecilia Harmby, Susanne Hyberg, Fredrik Johansen, Berglind Jonsdottir, MD, Helena Elding Larsson, MD, PhD,6,14 Sigrid Lenrick Forss, Markus Lundgren,14 Maria Månsson-Martinez, Maria Markan, Jessica Melin,12 Zeliha Mestan, Kobra Rahmati, Anita Ramelius, Anna Rosenquist, Falastin Salami, Sara Sibthorpe, Birgitta Sjöberg, Ulrica Swartling, PhD,9,12 Evelyn Tekum Amboh, Carina Törn, PhD,3,15 Anne Wallin, Åsa Wimar,12,14 and Sofie Åberg. Lund University.

Washington Clinical Center

William A. Hagopian, MD, PhD, PI,1,3–7,11,13,14 Michael Killian,6,7,12,13 Claire Cowen Crouch,12,14,15 Jennifer Skidmore,2 Josephine Carson, Kayleen Dunson, Rachel Hervey, Corbin Johnson, Rachel Lyons, Arlene Meyer, Denise Mulenga, Allison Schwartz, Joshua Stabbert, Alexander Tarr, Morgan Uland, and John Willis. Pacific Northwest Diabetes Research Institute.

Pennsylvania Satellite Center

Dorothy Becker, MD, Margaret Franciscus, MaryEllen Dalmagro-Elias Smith,2 Ashi Daftary, MD, Mary Beth Klein, and Chrystal Yates. Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC.

Data Coordinating Center

Jeffrey P. Krischer, PhD, PI,1,4,5,10,11 Michael Abbondondolo, Sarah Austin-Gonzalez, Maryouri Avendano, Sandra Baethke, Rasheedah Brown,12,15 Brant Burkhardt, PhD,5,6 Martha Butterworth,2 Joanna Clasen, David Cuthbertson, Christopher Eberhard, Steven Fiske,9 Dena Garcia, Jennifer Garmeson, Veena Gowda, Kathleen Heyman, Francisco Perez Laras, Hye-Seung Lee, PhD,1,2,13,15 Shu Liu, Xiang Liu, PhD,2,3,9,14 Kristian Lynch, PhD,5,6,9,15 Jamie Malloy, Cristina McCarthy,12,15 Steven Meulemans, Hemang Parikh, PhD,3 Chris Shaffer, Laura Smith, PhD,9,12 Susan Smith,12,15 Noah Sulman, PhD, Roy Tamura, PhD,1,2,13 Ulla Uusitalo, PhD,2,15 Kendra Vehik, PhD,4–6,14,15 Ponni Vijayakandipan, Keith Wood, and Jimin Yang, PhD, RD2,15 Past staff: Lori Ballard, David Hadley, PhD, and Wendy McLeod. University of South Florida.

Project Scientist

Beena Akolkar, PhD.1,3–7,10,11 National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

HLA Reference Laboratory

Henry Erlich, PhD, Steven J. Mack, PhD, and Anna Lisa Fear. Center for Genetics, Children’s Hospital Oakland Research Institute.

Repository

Sandra Ke and Niveen Mulholland, PhD. NIDDK Biosample Repository at Fisher BioServices.

Other Contributors

Kasia Bourcier, PhD,5 National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Thomas Briese, PhD,6,15 Columbia University. Suzanne Bennett Johnson, PhD,9,12 Florida State University. Eric Triplett, PhD,6 University of Florida.

Committees

1Ancillary Studies, 2Diet, 3Genetics, 4Human Subjects/Publicity/Publications, 5Immune Markers, 6Infectious Agents, 7Laboratory Implementation, 8Maternal Studies, 9Psychosocial, 10Quality Assurance, 11Steering, 12Study Coordinators, 13Celiac Disease, 14Clinical Implementation, and 15Quality Assurance Subcommittee on Data Quality.

Footnotes

Dr Smith conceptualized and designed the study, drafted the manuscript, interpreted the data, and completed all subsequent revisions until submission; Dr Lynch carried out the statistical analysis and critically reviewed the manuscript; Dr Kurppa drafted the manuscript, advised in presentation of analysis results, and revised the drafts critically for important intellectual content; Drs Koletzko and Liu advised in presentation of analysis results and revised the drafts critically for important intellectual content; Dr Krischer conceptualized and designed the TEDDY study, advised in presentation of analysis results, and revised the drafts critically for important intellectual content; Drs Johnson and Agardh conceptualized and designed the study, interpreted the data, advised in presentation of analysis results, and revised the drafts critically for important intellectual content; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Funded by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grants U01 DK63829, U01 DK63861, U01 DK63821, U01 DK63865, U01 DK63863, U01 DK63836, U01 DK63790, UC4 DK63829, UC4 DK63861, UC4 DK63821, UC4 DK63865, UC4 DK63863, UC4 DK63836, UC4 DK95300, UC4 DK100238, and UC4 DK106955, and contract no. HHSN267200700014C and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (NIH). Supported in part by the NIH/NCATS Clinical and Translational Science Awards to the University of Florida (UL1 TR000064) and the University of Colorado (UL1 TR001082). Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

COMPANION PAPER: A companion to this article can be found online at www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2016-4323.

References

- 1.D’Amico MA, Holmes J, Stavropoulos SN, et al. Presentation of pediatric celiac disease in the United States: prominent effect of breastfeeding. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2005;44(3):249–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green PH, Cellier C. Celiac disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(17):1731–1743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niederhofer H, Pittschieler K. A preliminary investigation of ADHD symptoms in persons with celiac disease. J Atten Disord. 2006;10(2):200–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sander HW, Magda P, Chin RL, et al. Cerebellar ataxia and coeliac disease. Lancet. 2003;362(9395):1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pynnönen PA, Isometsä ET, Aronen ET, Verkasalo MA, Savilahti E, Aalberg VA. Mental disorders in adolescents with celiac disease. Psychosomatics. 2004;45(4):325–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lichtwark IT, Newnham ED, Robinson SR, et al. Cognitive impairment in coeliac disease improves on a gluten-free diet and correlates with histological and serological indices of disease severity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40(2):160–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agardh D, Lee HS, Kurppa K, et al. ; TEDDY Study Group . Clinical features of celiac disease: a prospective birth cohort. Pediatrics. 2015;135(4):627–634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu E, Lee HS, Aronsson CA, et al. ; TEDDY Study Group . Risk of pediatric celiac disease according to HLA haplotype and country. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(1):42–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.TEDDY Study Group . The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) study: study design. Pediatr Diabetes. 2007;8(5):286–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vehik K, Fiske SW, Logan CA, et al. ; TEDDY Study Group . Methods, quality control and specimen management in an international multicentre investigation of type 1 diabetes: TEDDY. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2013;29(7):557–567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA Preschool Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ivanova MY, Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA, et al. Preschool psychopathology reported by parents in 23 societies: testing the seven-syndrome model of the child behavior checklist for ages 1.5-5. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(12):1215–1224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Månsson J, Stjernqvist K, Bäckström M. Behavioral outcomes at corrected age 2.5 years in children born extremely preterm. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2014;35(7):435–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wellman HM, Harris PL, Banerjee M, et al. . Early understanding of emotion: evidence from natural language. Cogn Emotion. 1995;9(2/3):117–149 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rebok G, Riley A, Forrest C, et al. Elementary school-aged children’s reports of their health: a cognitive interviewing study. Qual Life Res. 2001;10(1):59–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kurppa K, Ashorn M, Iltanen S, et al. Celiac disease without villous atrophy in children: a prospective study. J Pediatr. 2010;157(3):373–380, 380.e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]