Using surveys, this study captures rates and reasons for ever use of e-cigarettes for “dripping” among high school youth.

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) electrically heat and vaporize e-liquids to produce inhalable vapors. These devices are being used to inhale vapors produced by dripping e-liquids directly onto heated atomizers. The current study conducts the first evaluation of the prevalence rates and reasons for using e-cigarettes for dripping among high school students.

METHODS:

In the spring of 2015, students from 8 Connecticut high schools (n = 7045) completed anonymous surveys that examined tobacco use behaviors and perceptions. We assessed prevalence rates of ever using e-cigarettes for dripping, reasons for dripping, and predictors of dripping behaviors among those who reported ever use of e-cigarettes.

RESULTS:

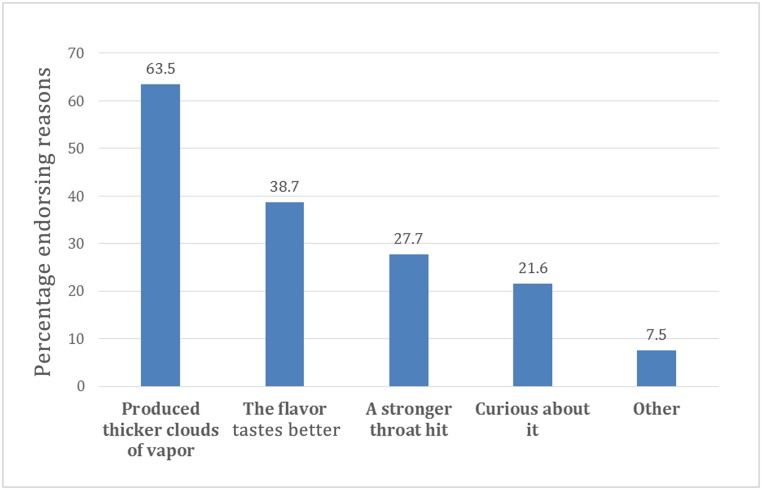

Among 1080 ever e-cigarette users, 26.1% of students reported ever using e-cigarettes for dripping. Reasons for dripping included produced thicker clouds of vapor (63.5%), made flavors taste better (38.7%), produced a stronger throat hit (27.7%), curiosity (21.6%), and other (7.5%). Logistic regression analyses indicated that male adolescents (odds ratio [OR] = 1.64), whites (OR = 1.46), and those who had tried multiple tobacco products (OR = 1.34) and had greater past-month e-cigarette use frequency (OR = 1.07) were more likely to use dripping (Ps < .05).

CONCLUSIONS:

These findings indicate that a substantial portion (∼1 in 4) of high school adolescents who had ever used e-cigarettes also report using the device for dripping. Future efforts must examine the progression and toxicity of the use of e-cigarettes for dripping among youth and educate them about the potential dangers of these behaviors.

What’s Known on This Subject:

Electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) use is growing among youth. E-cigarettes are also being used to inhale vapors produced by directly dripping e-liquids onto heated coils. There is no information on whether high school youth are participating in this behavior.

What This Study Adds:

1 in 4 high school ever e-cigarette users report having used these devices for dripping. E-cigarette users use dripping to produce thicker clouds of vapor, get a stronger throat hit, and make flavors taste better.

Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) are battery-powered devices that vaporize solutions or e-liquids to produce inhalable vapors. Of particular concern, high school students are using e-cigarettes at increasing rates; evidence from the National Youth Tobacco Survey indicates that ever e-cigarette use among high school students increased from 1.5% in 2011 to 16% in 2015.1 Our evidence obtained in 2013 in Connecticut observed that that 25.2% of high school students reported ever e-cigarette use.2

Traditional e-cigarette devices electrically heat (via inhalation-activated heating elements) and vaporize e-liquids that may contain nicotine, which are contained in tanks or cartomizers. Certain e-cigarettes, such as mods or vape pens (http://www.cigbuyer.com/types-of-e-cigarettes/) allow users to change voltage, nicotine concentrations, and other constituents of e-liquids including flavors. Emerging evidence suggests that e-cigarettes are being used for a number of alternative behaviors that may or may not involve nicotine use, such as smoke tricks,3,4 use of flavors,2,3 and use of other substances such as marijuana.5

E-cigarettes are also being used for “dripping,” which involves vaporizing the e-liquid at high temperatures by dripping a couple of drops of e-liquid directly onto an atomizer’s coil and then immediately inhaling the vapor that is produced. Guides and videos on how to use e-cigarettes for dripping can be found freely on the Internet (eg, http://vaporcloudreviews.com/beginners-guide-to-dripping/). Users can modify their existing e-devices for dripping or can purchase commercially available atomizers that are optimized for dripping (eg, http://spinfuel.com/art-drip-guide-vaping/). Although there is no evidence on the prevalence rates or toxicity of this behavior among adults or youth, Talih et al6 have shown that dripping e-liquids directly onto the e-cigarette atomizers could expose users to high temperatures and toxic chemicals such as aldehydes. Moreover, Kosmider et al7 have shown that exposure of e-liquids to high temperatures results in significant increases in the levels of formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, and acetone in the vapors. To better appreciate the potential risks associated with dripping, there is a critical need to understand prevalence rates of this alternative e-cigarette use behavior among youth.

We used school surveys conducted in the spring of 2015 to examine prevalence rates of ever using e-cigarettes for dripping among high school students who reported use of e-cigarettes. We also examined reasons why youth use dripping. Because dripping is a novel e-cigarette use behavior, we did not have a specific hypothesis about prevalence rates or reasons for this behavior. To better understand who was dripping, we evaluated whether this behavior was associated with demographic variables that have been shown to be related to e-cigarette use, including sex, age, and race.2,8–14 Furthermore, we examined associations with the number of tobacco products that youth had tried and frequency of e-cigarette use in the past month. We hypothesized that youth who had tried more tobacco products and were using e-cigarettes more would be more likely to use e-cigarettes for dripping.

Method

Survey Procedures

Youth from 8 southeastern Connecticut high schools were surveyed in the spring of 2015. To obtain a sociodemographically diverse sample, these schools were drawn from 7 of 9 district reference groups, which are groupings of schools in Connecticut with similar characteristics (family income levels, parental education levels, parental occupation status, and use of non-English home language; http://www.sde.ct.gov/sde/LIB/sde/PDF/dgm/report1/cpse2006/appndxa.pdf).

The survey was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yale University and the local school administrators. Information sheets were mailed to parents along with the option of disallowing their child’s participation. Two parents refused their child’s participation in the surveys; these children did not participate in the survey and were allowed to complete other work during survey administration. Before completing the survey, students were informed that participation was voluntary and anonymous and that their data were confidential. Students completed the brief survey during their homeroom periods.

Measures

Participant Demographics

Students reported demographic information on sex, race, and age.

E-Cigarette Use Status

Students were shown pictures of various kinds of e-cigarettes accompanied by the following text: “E-cigarettes are battery powered and produce vapor instead of smoke. There are many types of e-cigarettes. E-cigarettes can be bought as one-time, disposable products, or can be bought as re-usable kits with cartridges. The cartridges come in many different flavors and nicotine concentrations. Some people refill their own cartridges with ‘juice,’ sometimes called e-juice.”

We determined e-cigarette use status via the following question: “Have you tried an e-cigarette?”; students who provided positive responses were classified as ever e-cigarette users. We then asked, “How many days out of the past 30 days did you use e-cigarettes?” This variable was used to calculate e-cigarette frequency (number of days used) in the past month.

E-Cigarettes for “Dripping”

We asked students about dripping by asking, “Have you ever used the dripping method to add e-liquid to your e-cigarette?” (response options included “I do not use e-cigarettes,” “yes,” “no,” or “I don’t know”). We also explored reasons for dripping by asking, “Why do you use the dripping method?” (students were asked to select all that apply from these response options: “I do not use dripping,” “It makes the flavor taste better,” “It makes a stronger throat hit,” “It makes a thicker cloud of vapor,” “I was curious,” and “Other”). Given the limited information on reasons for dripping, we derived these response options from the manufacturer claims (http://spinfuel.com/art-drip-guide-vaping) and anecdotal responses from e-cigarette using adolescents.

Other Tobacco Use

Students were shown pictures and provided descriptions of each tobacco product and were asked, “Have you tried cigarettes, cigars, cigarillos, hookah, smokeless tobacco?” (each product was examined individually, and response options included “yes” and “no”). “Yes” responses to these products were summed to create a composite variable of number of tobacco products used.

Data Analytic Plan

All our analyses were based on available data. We calculated prevalence rates of ever using dripping among all students reporting ever using e-cigarettes (12 participants who reported dripping but did not report ever e-cigarette use were excluded). We first explored associations between ever dripping and demographic characteristics as well as other tobacco use. χ2 and ANOVA tests were used to compare “dripping” and “non-dripping” e-cigarette users on age, gender, race (white versus nonwhite), number of tobacco products tried, and number of days using e-cigarettes in the past month. We then conducted a logistic regression to investigate the association between ever dripping and age, gender, race, number of tobacco products tried, and past month e-cigarette frequency while controlling for school in the model. The α level was set to .05.

Results

Participants

A sample of 1874 high school students responded “Yes” to the question “Have you tried an e-cigarette?” Among these 1874 ever e-cigarette users, 198 students did not provide responses on the dripping question and were excluded; this left us with a sample of 1676 ever e-cigarette users. We also excluded 596 students based on incongruent responses; specifically, 568 students who in response to the question on dripping indicated that they did not use e-cigarettes, and an additional 28 participants who in response to the second question on reasons for dripping indicated that they did not use dripping. Our final sample consisted of 1080 ever e-cigarette users who had responses on the dripping question (“yes,” “no,” “I don’t know”).

The final sample was 47.6% female and 72.6% white, with an average age of 16.2 ± 1.22 years. Overall, 81.9% of the sample had tried another tobacco product, such as cigarettes, hookah, cigars, smokeless tobacco, and cigarillos; on average adolescents had tried 2.1 ± 1.6 types of tobacco products. 61% reported past-month use of e-cigarettes and provided data on e-cigarette frequency.

Among ever e-cigarette users (n = 1080), 26.1% (n = 282) reported they had used dripping, 48.7% (n = 526) reported that they had never used dripping, and 25.2% (n = 272) reported that they did not know whether they had ever used dripping. When comparing youth who said they had ever used versus never used dripping, we observed significant differences by gender, race, age, number of other types of tobacco products tried, and number of days they used e-cigarettes (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Demographic Information on Ever E-Cigarette Users (n = 1080)

| Dripping | No Dripping | Statistics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | N | % | N | % | χ2 |

| Sex | 62.24*** | ||||

| Male | 206 | 74.37 | 233 | 45.16 | |

| Female | 71 | 25.63 | 283 | 54.84 | |

| Race | 9.70** | ||||

| White | 224 | 79.43 | 364 | 69.20 | |

| Nonwhite | 58 | 20.57 | 162 | 30.80 | |

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ANOVA (F) | |

| Age | 16.4 | 1.15 | 16.2 | 1.25 | 6.56* |

| Number of tobacco products tried | 2.9 | 1.66 | 1.8 | 1.49 | 100.99*** |

| Days e-cigarettes used in the past 30 d | 13.2 | 12.56 | 3.8 | 7.67 | 144.65** |

P < .001.

P < .01.

P < .05.

In the logistic regression model, we observed that having ever used dripping was positively associated with being male, being white, having tried more tobacco products, and using e-cigarettes on a greater number of days in the past month (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Factors Associated With “Dripping” Among Ever E-Cigarette Users

| Independent Variable | Adjusted OR | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male (reference: female) | 2.74* | 1.83 | 4.11 |

| White (reference: nonwhite) | 1.84* | 1.13 | 2.99 |

| Age | 1.00 | 0.85 | 1.19 |

| Number of other tobacco products tried | 1.34* | 1.18 | 1.53 |

| Days e-cigarettes used in the past 30 d | 1.07* | 1.05 | 1.09 |

P < .05.

Youth who reported ever dripping (n = 282) endorsed various reasons for engaging in these behaviors (Fig 1), with the top reasons being “produces thicker clouds of vapor” (63.5%), “flavor tastes better” (38.7%), “a stronger throat hit” (27.7%), and “curiosity” (21.6%); 7.5% of students provided “other” open-ended responses such as “friends use it,” “tried it once,” and “don’t know”.

FIGURE 1.

Reasons for “dripping” among ever e-cigarette users (N = 282). More than 1 response could be selected, so the percentages do not add to 100%.

Discussion

The current study is the first to demonstrate that high school students are using e-cigarettes for dripping. We observed that 26.1% of students who reported ever using an e-cigarette also reported dripping. Of concern, existing evidence, though limited, suggests that dripping e-liquids may lead to higher levels of nonnicotine toxicant emissions.6 Our evidence suggests that male students, white students, those who had tried multiple tobacco products, and those who used e-cigarettes on more days in the past month were more likely to report using e-cigarettes for dripping behaviors. These results suggest that youth who use dripping may be those who are more familiar with and have experience with using multiple tobacco products, including e-cigarettes.

Interestingly, many youth report that they use dripping to produce thicker clouds of vapor, which suggests that youth who participate in these alternative behaviors may be those who use e-cigarettes for smoke tricks and vape competitions.3,4 Youth also endorsed that dripping enhances the flavors used in e-cigarettes and produces a better throat hit. We did not specifically assess what flavors are being used by youth for dripping. However, emerging evidence suggests that many flavors contain reactive chemical species that, when vaporized at high temperatures, can form toxic levels of compounds such as carbonyls (eg, formaldehyde).15–18 We also did not assess whether nicotine was present in the e-liquids used for dripping. However, e-cigarette users are known to manipulate nicotine levels to change the strength of the “throat hit,”19 and the youth in our study reported using dripping for improved “throat hit.” This finding leads us to speculate that they may be using e-liquids with nicotine; in fact, many of the online guides on dripping discuss the use of appropriate nicotine levels (http://spinfuel.com/art-drip-guide-vaping/). Existing evidence suggests that the use of higher voltages (hence higher temperatures) in e-cigarettes results in higher blood levels of nicotine.20 Hence, if youth are dripping e-liquids with nicotine directly onto the heated atomizers, they could be exposed to higher levels of nicotine than what they might be exposed to from a standard puff of an e-cigarette, raising concerns about nicotine addiction among these young users. Future studies should examine these critical issues to elucidate the health risks of dripping. Future research also should examine how youth are modifying their e-cigarette devices and e-liquids to engage in these behaviors.

These novel findings should be considered in light of several limitations. First, our survey results were based on self-report. However, students were informed that the survey was anonymous and that their responses were confidential, which was intended to encourage honest reporting. Second, this evidence was collected from high schools in Connecticut, and we cannot speak to the generalizability of these findings to youth from other states in the United States. Larger national surveys are needed to collect information on alternative e-cigarette use behaviors such as dripping. Moreover, our question for assessing dripping may not have been clear to some youth because 25.2% reported that they did not know whether they had participated in this behavior; in fact, it is possible that this limitation may have led to lower estimates of the behavior. More qualitative research is needed to determine how to best assess dripping and other alternative e-cigarette use behaviors among youth. Finally, we did not assess how often youth had used e-cigarettes for dripping; it is possible that some of the youth may have only occasionally engaged in this behavior. Future research should focus on the frequency and longitudinal progression of these behaviors.

Conclusions

Despite the stated limitations, the results of this study provide important initial evidence that high school students are using e-cigarettes for dripping behaviors. Given that ∼1 in 4 high school e-cigarette users report dripping, future safety studies of e-cigarettes should focus on the toxicities of hot vapors produced by exposure of e-liquids to high temperatures, as with dripping. Importantly, risk assessment models for e-cigarettes must take into consideration the prevalence rates and toxicities of these alternative e-cigarette use behaviors, especially among vulnerable youth. There is also a critical need for regulatory efforts that consider restrictions on the e-cigarette device so it cannot be easily manipulated for behaviors such as dripping. Finally, there is an urgent need for prevention programs that educate youth about the potential dangers of these alternative e-cigarette use behaviors.

Glossary

- e-cigarette

electronic cigarette

- OR

odds ratio

Footnotes

Dr Krishnan-Sarin conceptualized and designed the study and drafted the initial manuscript; Drs Morean, Kong, Bold, Camenga, Cavallo, and Simon assisted with the design and conduct of the study and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Ms Wu carried out the initial analyses and reviewed and revised the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Supported by NIH grants P50DA009241 and P50DA036151 (Yale TCORS) and the US Food and Drug Administration Center for Tobacco Products. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the Food and Drug Administration. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Singh T, Arrazola RA, Corey CG, et al. Tobacco use among middle and high school students—United States, 2011–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(14):361–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krishnan-Sarin S, Morean ME, Camenga DR, Cavallo DA, Kong G. E-cigarette use among high school and middle school adolescents in Connecticut. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(7):810–818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kong G, Morean ME, Cavallo DA, Camenga DR, Krishnan-Sarin S. Reasons for electronic cigarette experimentation and discontinuation among adolescents and young adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(7):847–854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wagoner KG, Cornacchione J, Wiseman KD, Teal R, Moracco KE, Sutfin EL. E-cigarettes, hookah pens and vapes: adolescent and young adult perceptions of electronic nicotine delivery systems. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(10):2006–2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morean ME, Kong G, Camenga DR, Cavallo DA, Krishnan-Sarin S. High school students’ use of electronic cigarettes to vaporize cannabis. Pediatrics. 2015;136(4):611–616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Talih S, Balhas Z, Salman R, Karaoghlanian N, Shihadeh A. “Direct dripping”: a high-temperature, high-formaldehyde emission electronic cigarette use method. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(4):453–459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kosmider L, Sobczak A, Fik M, et al. Carbonyl compounds in electronic cigarette vapors: effects of nicotine solvent and battery output voltage. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(10):1319–1326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arrazola RA, Neff LJ, Kennedy SM, Holder-Hayes E, Jones CD; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Tobacco use among middle and high school students: United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(45):1021–1026 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barrington-Trimis JL, Berhane K, Unger JB, et al. Psychosocial factors associated with adolescent electronic cigarette and cigarette use. Pediatrics. 2015;136(2):308–317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dutra LM, Glantz SA. Electronic cigarettes and conventional cigarette use among U.S. adolescents: a cross-sectional study. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(7):610–617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neff LJ, Arrazola RA, Caraballo RS, et al. Frequency of tobacco use among middle and high school students: United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(38):1061–1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wills TA, Knight R, Williams RJ, Pagano I, Sargent JD. Risk factors for exclusive e-cigarette use and dual e-cigarette use and tobacco use in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2015;135(1). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/135/1/e43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.King BA, Patel R, Nguyen KH, Dube SR. Trends in awareness and use of electronic cigarettes among US adults, 2010–2013. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(2):219–227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schoenborn CA, Gindi RM. Electronic cigarette use among adults: United States, 2014. NCHS Data Brief. 2015;217(217):1–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Behar RZ, Davis B, Wang Y, Bahl V, Lin S, Talbot P. Identification of toxicants in cinnamon-flavored electronic cigarette refill fluids. Toxicol In Vitro. 2014;28(2):198–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lerner CA, Sundar IK, Yao H, et al. Vapors produced by electronic cigarettes and e-juices with flavorings induce toxicity, oxidative stress, and inflammatory response in lung epithelial cells and in mouse lung. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0116732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sherwood CL, Boitano S. Airway epithelial cell exposure to distinct e-cigarette liquid flavorings reveals toxicity thresholds and activation of CFTR by the chocolate flavoring 2,5-dimethypyrazine. Respir Res. 2016;17(1):57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geiss O, Bianchi I, Barrero-Moreno J. Correlation of volatile carbonyl yields emitted by e-cigarettes with the temperature of the heating coil and the perceived sensorial quality of the generated vapours. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2016;219(3):268–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Etter JF. Throat hit in users of the electronic cigarette: an exploratory study. Psychol Addict Behav. 2016;30(1):93–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Talih S, Balhas Z, Eissenherg T, et al. Effects of user puff topography, device voltage, and liquid nicotine concentration on electronic cigarette nicotine yield: measurements and model predictions. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(2):150–157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]