Abstract

In the past decade, remarkable advances in the production and use of antibodies as therapeutic drugs and in research/diagnostic fields have led to their recognition as value-added proteins. These biopharmaceuticals have become increasingly important, reinforcing the current demand for the development of more benign, scalable and cost-effective techniques for their purification. Typical polymer–polymer and polymer–salt aqueous biphasic systems (ABS) have been studied for such a goal; yet, the limited polarity range of the coexisting phases and their low selective nature still are their major drawbacks. To overcome this limitation, in this work, ABS formed by bio-based ionic liquids (ILs) and biocompatible polymers were investigated. Bio-based ILs composed of ions derived from natural sources, namely composed of the cholinium cation and anions derived from plants natural acids, have been designed, synthesized, characterized and used for the creation of ABS with polypropyleneglycol (PPG 400). The respective ternary phase diagrams were initially determined at 25 °C to infer on mixture compositions required to form aqueous systems of two phases, further applied in the extraction of pure immunoglobulin G (IgG) to identify the most promising bio-based ILs, and finally employed in the purification of IgG from complex and real matrices of rabbit serum. Remarkably, the complete extraction of IgG to the IL-rich phase was achieved in a single-step. With pure IgG a recovery yield of 100% was obtained, while with rabbit serum this value slightly decreased to ca. 85%. Nevertheless, a 58% enhancement in the IgG purity was achieved when compared with its purity in serum samples. The stability of IgG before and after extraction was also evaluated by size exclusion high-performance liquid chromatography (SE-HPLC), sodium dodecyl sulphate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). In most ABS formed by bio-based ILs, IgG retained its native structure, without degradation or denaturation effects, supporting thus their potential as remarkable platforms for the purification of high-cost biopharmaceuticals.

1. Introduction

Amongst several therapeutic agents in current clinical use, major technological advances in biopharmaceuticals demonstrated the high relevance of antibodies.1 Immunoglobulin G (IgG), a glycoprotein, is the most widely used type of antibody in a variety of biomedical applications.2 Antibodies have been used in the treatment of cancer, as transporters of toxins or radio labelled isotopes to cancerous cells, and in the treatment of autoimmune diseases and neural disorders.3–6 Due to the continuous increase in the use of IgG in various high-end applications, there is thus a boost in demand for high quality/high purity IgG, not only for therapeutic applications but also for applications in cutting-edge diagnosis and research. However, these commercially available antibodies are highly expensive, which has been preventing their widespread applications, mainly due to the lack of cost-effective purification techniques.7 Processes for the purification of IgG typically require various steps, viz. clarification, concentration and polishing by chromatographic techniques (such as ion exchange, gel permeation and affinity chromatography).8–11 On the other hand, solvent use represents ca. 60% of the overall energy in pharmaceuticals production and can lead to 50% of post-treatment greenhouse gas emissions.12,13 Therefore, there is high demand for developing cost-effective and sustainable techniques to obtain high quality IgG. In order to overcome these and other inadequacies associated with conventional methods, extraction and purification of valued-added biopharmaceuticals using aqueous biphasic systems (ABS) might have been seen as a viable alternative.14–16

ABS were proposed in the late 50s by Albertsson,17 and since then they have been recognized as a biocompatible extraction technique mostly due to their high water content. Two aqueous-rich phases are spontaneously formed after mixing two structurally different and appropriate components in aqueous media, such as polymer–polymer, polymer–salt or salt–salt combinations.18 Although these systems have been studied for at least the last five decades, the introduction of ionic liquids (ILs) in ABS formation (IL-based ABS),19 combined with salts or polymers, allows overcoming the major drawback of more traditional polymer-based systems – the restricted polarity difference in their coexisting phases which hampers their selective nature.20 IL-based ABS appear as outstanding alternatives supported by improved and tailored extraction selectivities of a wide range of value-added biomolecules, including highly susceptible biomolecules such as proteins.18,21 Consisting entirely of ions, ILs represent a group of solvents that embrace a wide range of unique properties, such as non-volatility, stability in a wide electrochemical window, and tailored polarity and miscibility with other solvents.22–24

ABS formed by ILs and inorganic salts are the most widely investigated, since they are also the easiest to form due to the high salting-out capacity of inorganic salts.18,25,26 On the other hand, imidazolium-based ILs combined with halogens and fluorinated anions have been the preferred choice for ABS formulations.18 These combinations raise however some environmental and biocompatibility concerns. To minimize these apprehensions, ABS formed by bio-based ILs, preferably derived from natural sources, and biodegradable and biocompatible polymers, such as polypropylene glycol, polyethylene glycol, natural polysaccharides, among others, represent the most relevant type of IL-based ABS. Apart from the commonly studied imidazolium-based fluids, many of them toxic to organisms and poorly biodegradable, in the past few years, advances in the field of ILs allowed the synthesis of ILs derived from natural sources, such as from amino acids, carbohydrates and phenolic acids.27–31 Cholinium-based ILs with low-toxicity, and high biodegradability and biocompatibility features have been reported.32–38 These findings foster thus the investigation on the potential of bio-based ILs for the extraction of sensitive biomacromolecules, such as proteins and antibodies. It is known that the function and activity of proteins are directly dependent on their three-dimensional structure.39 In this context, when developing techniques to purify value-added proteins, it is required to guarantee that they maintain their biological activity and native structure, and as demonstrated herein, bio-based ILs appear as promising candidates for such applications.

In this work, a series of new bio-based ILs have been synthesized and characterized. The novel ILs are composed of the cholinium cation combined with anions derived from plants natural acids. Amongst the nine bio-based ILs studied herein, six are reported for the first time. The suitability of these bio-based ILs towards the formation of polymer–IL-based ABS was explored thereafter. Polypropylene glycol with a molecular weight of 400 g mol−1 (PPG 400) was used as the second phase-forming component due to its biocompatible nature and high biodegradability.40 After addressing the possibility of forming ABS, these were then investigated for the extraction of pure IgG and finally for its purification from rabbit serum. The structural stability of IgG before and after extraction was also studied to ascertain the protein-friendly features of the proposed purification platforms, allowing them to be further explored in terms of scale-up viability as well as for the purification of other value-added biopharmaceuticals.

2. Experimental section

2.1. Materials

For the synthesis of bio-based ILs, cholinium bicarbonate (80 wt% aqueous solution), d-(+)-galacturonic acid, cholinium chloride (>98% pure), cholinium acetate (>99% pure) and poly (propylene glycol) 400 were purchased from Sigma Aldrich, USA. Glycolic, pyruvic, abietic, l-ascorbic, 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic (gentisic acid) and d-(−)quinic acids were purchased from TCI Chemicals, Tokyo, Japan. Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) was purchased from SRL Chemicals, India. Lactic acid was acquired from Riedel-de-Haën, Germany. All chemicals used were of analytical grade and used as received. Phosphate buffered saline (PBS) pellets (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) were used to prepare the solutions of IgG. Purified IgG was obtained from rabbit serum (reagent grade, ≥95%) that was obtained as a lyophilized powder from Sigma-Aldrich, USA, and was stored at −20 °C. The rabbit serum used was obtained from Sigma Aldrich (R9133 Sigma), USA, having a total protein concentration between 40–70 mg mL−1 (determined by the biuret method). This product was provided as a liquid containing 0.01% thimerosal as a preservative and was stored at −20 °C. The water used was double distilled, passed through a reverse osmosis system and further treated with a Milli-Q plus 185 water purification apparatus.

2.2. Synthesis and characterization of bio-based ionic liquids

Bio-based ILs were synthesized using a metathesis reaction reported earlier.36b In a typical reaction, the corresponding acid was added into a round bottom flask containing aqueous cholinium bicarbonate (80 wt% in water), in an equimolar ratio (1 : 1), under continuous stirring and an inert atmosphere. After the complete addition of each acid, the reaction mixture was refluxed at 60 °C for 12 h under a N2 atmosphere. Finally, the synthesized ILs were washed with ethyl acetate to remove unreacted starting materials. The ILs thus obtained were dried under reduced pressure and stored in closed glass vials, in a dry place and protected from light. The structure of the synthesized ILs was confirmed by 1H NMR and electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry (ESI-MS). 1H NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance II (500 MHz), in which ca. 15 mg of each IL were dissolved in D2O/d6-DMSO. ESI-MS of all ILs were recorded on a Q-TOF Micro Mass Spectrometer (USA). Mass fragmentation patterns of all bio-based ILs (10 ppm of each IL in Milli-Q water) were recorded in both ESI positive mode (ESI+) and negative mode (ESI−) in the range of m/z 50–500 and data were processed using the Masslynx 4.0 software (Waters Corp., USA). Thermo-gravimetric analysis (TGA) was carried out on a NETZSCH TG 209F1 Libra TGA209F1D-0105-L machine using a temperature programmer between 30 and 450 °C, at a heating rate of 5 °C min−1, under a nitrogen gas atmosphere. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) was measured on NETZSCH DC 209F1 Libra DCA209F1D-0105-L equipment in the range of temperatures from −100 to 100 °C, at a heating rate of 2 °C min−1, under a nitrogen gas atmosphere. The zero shear viscosity (ZSV) of all ILs was recorded on an Anton Paar, Physica MCR 301 Rheometer USA, using parallel plate PP50/P-PTD200 geometry (49.971 mm diameter, 0.1 mm gap). ZSV was measured by employing the shear rates 0.01, 1 and 10 s−1 at 25 °C. The optical rotation of the studied bio-based ILs was measured on a Rudolph Instrument DigiPol DP781 Polarimeter, using a Polarimeter tube with 100 mm path length. Optical rotation was measured at 589 nm at 25 °C. Before their use in the formation of ABS, all ILs samples were subjected to a further drying step under high vacuum to remove traces of water, and their purity was checked by 1H NMR. The various peaks (D2O, 500 MHz, δ/ppm relative to TMS) for the different ILs are assigned. For Cho-IA the peaks are assigned as 2.62 (s, 9H, −CH3), 2.88 (t, 2H, −CH2−N−), 3.47 (s, 2H, −CH2−CO−), 3.60 (t, 2H, −O−CH2−), 7.08 (d, 1H, ═CH−N−), 6.96–7.51 (m, 4H, aromatic protons), 10.04 (s, 1H, −HN−); for Cho-Gly as 3.20 (s, 9H, −N−CH3), 3.51 (t, 2H, −CH2−N−), 3.94 (t, 2H, −O−CH2−), 4.05 (t, 1H, −CH2-O−); for Cho-Pyr as 2.33 (s, 3H, −CH3), 3.17 (s, 9H, −N−CH3), 3.48 (t, 2H, −CH2−N−), 4.01 (t, 2H, −O−CH2−); for Chol-Asc as 3.16 (s, 9H, −N−CH3), 3.48 (t, 2H, −N−CH2−), 3.71 (dt, 2H, −CH2−OH), 3.97 (m, 1H, −CH−OH), 4.02 (t, 2H, −H2C−OH), 4.49 (s, 1H, −O−CH−), for Cho-C3C as 3.17 (s, 9H, −N− CH3), 3.498(t, 2H, −CH2−N−), 4.00 (t, 2H, −CH2−OH), 7.20–7.59 (m, 4H, aromatic protons), 8.12 (t, 1H, =CH−Ar); for Cho-Gen as 3.00 (s, 9H, −N−CH3), 3.30 (t, 2H, −CH2−N−), 3.87 (t, 2H, −O−CH2−), 6.67 (d, 1H, ═CH− aromatic), 6.84 (dd, 1H, ═CH− aromatic), 7.13 (d, 1H, ═CH− aromatic); for Cho-d-Gal as 3.06 (s, 9H, −N−CH3), 3.36 (t, 2H, −CH2−N−), 3.45 (d, 1H, −CH−OH), 3.59 (t, 1H, −CH−OH), 3.91 (m, 2H, −O−CH2−), 3.99 (m, 1H, −CH−OH), 4.49 (d, 1H, −CH−COO−), 5.10 (d, 1H, −CH−OH); for Cho-Qui as 1.79 (m, 1H, −CH2−), 1.86 (m, 1H, −CH2), 1.89 (m, 1H, −CH2−), 1.96 (m, 2H, −CH2−), 3.11 (s, 9H, −N−CH3), 3.43 (t, 2H, −CH2−N−), 3.45 (m, 1H, −CH−OH), 3.93 (m, 1H, −CH−OH), 3.96 (t, 2H, −O−CH2−), 4.05 (m, 1H, −HC−OH) and for Cho-Abt (d6-DMSO, 500 MHz, δ/ppm relative to TMS) as 0.71 (s, 3H, −CH3), 0.94 (d, 3H, −CH3), 0.98 (d, 3H, −CH3), 1.03 (m, 3H, −CH3), 1.37 (m, 6H, −CH2−), 1.79 (m, 6H, −CH2−), 2.03 (m, 2H, −CH2−), 2.18 (m, 2H, −CH−), 3.16 (s, 9H, −N−CH3), 3.42 (t, 2H, −CH2−N−), 3.83 (t, 2H, −O-CH2−), 5.31 (s, 1H, −HC═C−), 5.69 (s, 1H, −HC═C−) (ESI, Fig. S1–S9†).

2.3. Determination of liquid–liquid phase diagrams

To ascertain on the mixture compositions required to form two phases and to be able to use ABS as extraction/purification platforms, the respective ternary phase diagrams were initially determined. The binodal curve of each ABS was determined through the cloud point titration method at (25 ± 1) °C and atmospheric pressure. The experimental procedure adopted has been validated in previous work.41 Briefly, pure PPG 400 and aqueous solutions of different ILs (ca. 90 wt%) were prepared gravimetrically and used for the consecutive identification of a cloudy solution (biphasic region) and a clear solution (monophasic region) by drop-wise addition of the IL solution and water to PPG, respectively. In some situations, addition of PPG 400 to the IL aqueous solution was also carried out to complete the phase diagrams. Each mixture composition was determined by the weight quantification of all components added within ±10−4 g (Mettler Toledo Excellence XS205 Dual Range). The tie-lines (TLs), which give the composition of each phase for a given mixture composition, were determined gravimetrically at 25 °C according to the original method reported by Merchuk et al.42 The experimental binodal curves were fitted by using eqn (1):42

| (1) |

where [PPG] and [IL] are the PPG 400 and IL weight fraction percentages, respectively, and the coefficients A, B, and C are the fitting parameters. The parameters were determined using the Sigma Plot 11.0 software. TLs and tie-line lengths (TLLs) were determined by the lever-arm rule through the relationship between the top phase weight and the overall system weight and composition, and as originally proposed by Merchuk et al.42 Further details can be found in the ESI.†

2.4. Extraction and purification of IgG using ABS formed by bio-based ILs

ABS consisting of 25 wt% of different ILs, 30 wt% of PPG 400 and 45 wt% of an aqueous solution containing IgG at 1 mg mL−1 were prepared gravimetrically (±10−4 g). Only for the system composed of choline-indole-3-acetate (Cho-IA) a different mixture composition was used, namely 40 wt% IL, 40 wt% of PPG 400 and 20 wt% of an aqueous solution containing IgG at 1 mg mL−1, due to the more restricted biphasic regime of (Cho-IA) as discussed below. Each ABS was mixed in a vortex, centrifuged (10 min at 1000 rpm), and then left at (25 ± 1) °C for 4 h. The upper and lower phases were then carefully separated and used for the determination of the IgG concentration in each phase. The IgG contents in both top and bottom phases were determined by size exclusion high-performance liquid chromatography (SE-HPLC). Before injection in the SE-HPLC, each phase was diluted at a 1 : 10 (v : v) ratio in PBS buffer (10 mM, pH = 7.4). A Chromaster HPLC system (VWR Hitachi) equipped with a binary pump, column oven, temperature controlled auto-sampler and DAD detector was used. SE-HPLC was performed using an analytical column Shodex Protein KW-802.5 (8 mm × 300 mm). A 100 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.0 with 0.3 M NaCl was run isocratically with a flow rate of 0.5 mL min−1 with an injection volume of 25 μL. The wavelength was set at 280 nm. Pure IgG from a rabbit source was used for the calibration curve, where a detection limit of 0.01 g L−1 was found. The percentage extraction efficiency of IgG (EEIgG%) and IgG recovery yield (YIgG%), which represent the extraction selectivity of IgG to a given phase, the IL-rich phase, were determined by the following equations:

| (2) |

| (3) |

where are the total weight of IgG in the PPG-rich phase, in the IL-rich phase, and in the initial mixture, respectively.

After identifying the best ABS constituted by bio-based ILs for the extraction of IgG, carried out with pure IgG as described before, they were then applied in the extraction and purification of IgG from real rabbit serum samples. ABS formed by 25 wt% of ILs + 30 wt% of PPG 400 + 45 wt% of rabbit serum (diluted at 1 : 10 (v/v); pH ≈ 7) were used. Each mixture was mixed using a Vortex mixer, centrifuged (10 min at 1000 rpm), and left for 4 h at (25 ± 1) °C in order to attain the complete partitioning of IgG and remaining proteins between the two phases. After the separation of the two phases, the IgG and remaining proteins were quantified by SE-HPLC, as described above. The percentage extraction efficiency and recovery yield of IgG to the IL-rich phase were determined according to eqn (2) and (3), respectively, whereas the percentage purity of IgG was calculated dividing the HPLC peak area of IgG by the total area of all peaks corresponding to all proteins present at the IL-rich phase. All extractions were carried out in triplicate.

2.5. Stability of IgG

The stability of IgG before and after extraction with the studied ABS was investigated by SE-HPLC, sodium dodecyl sulphate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). Although SE-HPLC was used to quantify IgG as mentioned before, at the same time, the structural integrity of the protein was monitored. The aggregation/degradation of IgG can be studied by SE-HPLC since it affects its retention time. SDS-PAGE analysis of IgG after extraction was carried out using ABS and pure IgG (1 mg mL−1) in PBS buffer (10 mM, pH 7.4) for comparative analysis. The detailed process for SDS-PAGE analysis is reported elsewhere.43 All the samples were diluted in Laemmli sample buffer in order to load ca. 200 μg of IgG per mL per lane prior to loading in the gel wells. These solutions were heated at 95 °C for 5 min for denaturation followed by loading into the wells of the SDS-PAGE gel containing 20% polyacrylamide. SDS-PAGE molecular weight markers from VWR were used. Gels were electrophoresed for 1.5 h at 135 V on polyacrylamide gels (stacking 4%; resolving 20%) with a running buffer constituted by 250 mM Tris-HCl, 1.92 M glycine and 1% SDS. After the run, the gels were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 0.1% (w/v), methanol 50% (v/v), acetic acid 7% (v/v) and water 42.9% (v/v) for 3–4 h at room temperature in an orbital shaker. The gels were then de-stained in a solution of acetic acid at 7% (v/v), methanol at 20% (v/v) and water at 73% (v/v) in an orbital shaker at 50 rpm for 3–4 h at 40 °C. Mixtures composed of 45 wt% of aqueous solutions containing IgG (1 mg mL−1), 30 wt% of PPG 400 and 25 wt% of different bio-based ILs were prepared and used to perform the stability studies by FTIR. Pure IgG (1 mg mL−1) in an aqueous solution of PBS buffer (10 mM, pH 7.4) was taken as the control sample for comparison purposes. IL aqueous solutions were used as backgrounds, and only after background correction, the spectra of IgG were recorded. FTIR spectra were obtained in the wavelength range from 1800 to 1200 cm−1, and recorded using a Perkin Elmer Spectrum Bx spectrometer with a resolution of 4 cm−1 and 64 scans. All spectra were fitted at the amide I region (1600–1700 cm−1) and deconvoluted using the Origin 8.5 software.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Synthesis and characterization of bio-based ILs

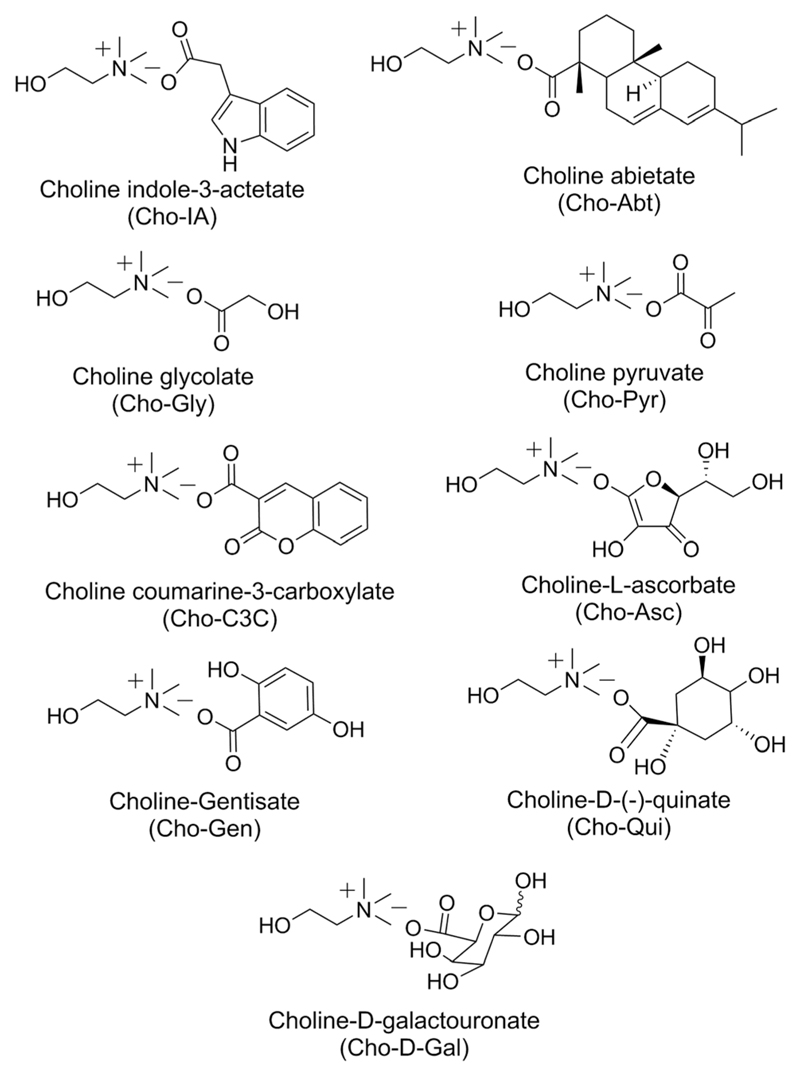

All bio-based ILs studied herein were synthesized by a metathesis reaction as reported earlier.35,36 In all cases, cholinium acts as the cation and different bioactive natural acids act as sources of anions (Table S1 in the ESI†). Fig. 1 shows the chemical structure of the bio-based ILs synthesized and used in this study.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of the synthesized bio-based ILs.

The IL having cholinium (Cho) as the cation and the plant growth regulator based anion, indole-3-acetic acid (IA) is liquid at room temperature. A similar liquid appearance at room temperature was observed for ILs prepared with anions derived from glycolic acid (Gly), pyruvic acid (Pyr), abietic acid (Abt), l-ascorbic acid (Asc), galacturonic acid (Gal) and quinic acid (Qui). However, ILs prepared with anions derived from coumarin-3-carboxylic acid (C3C) and 2,5-dihydroxy benzoic or genstic acid (Gen) are highly viscous and semi-solid in appearance. Amongst the nine synthesised bio-based ILs, three of them, namely (Cho-IA), (Cho-Gly) and (Cho-Pyr) had been reported earlier for the dissolution and stabilisation of salmon DNA36 and for the extraction of the protein bovine serum albumin (BSA).44

1H NMR and ESI-MS recorded for all ILs as described in the Experimental section confirm the formation of the ILs of proposed structures (Fig. S1–S9 in the ESI†). The ESI-MS of all the ILs were also recorded, for instance for (Cho-IA) m/z was found to be 104.14 and 174.29, suggesting the formation of the respective ions. Moreover, the m/z values obtained support that no side reaction took place (e.g. oxidation, reduction and elimination) during their synthesis.

Some physicochemical properties of the synthesized ILs are shown in Table 1. Glass transition temperatures were observed between −63.3 °C [for (Cho-d-Gal)] and −98.8 °C [for (Cho-Pyr)]. (Cho-Abt) displays the lowest melting temperature (−20.5 °C) while (Cho-Gen) presents the highest one (52.4 °C). In general, all synthesized ILs display melting temperatures lower than 100 °C and thus fit within the IL melting temperature based definition.45 (Cho-Qui) displays the highest temperature of decomposition (330 °C), while the IL with the indole-3-butyrate derived anion decomposes at 220 °C. Based on these results it is safe to admit that all ILs are relatively stable up to high temperatures and can be used in a wide variety of applications. The apparent viscosities are widely different depending on the nature of IL anions, with apparent viscosities ranging from 0.18 Pa s for (Cho-Gly) up to 6290 Pa s for (Cho-C3C). The observation of the optical rotation values for four of the ILs i.e., Cho-Abt, Cho-Asc, Cho-d-Gal and Cho-Qui indicated the chiral nature of these four ILs.

Table 1.

Physicochemical properties of the synthesized bio-based ionic liquids

| IL | Tg/°C | Tm/°C | Tdec/°C | [α]d | η/(Pa s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Cho-IA) | — | — | 300 | NS | 3.34 |

| (Cho-Gly) | −98.4 | 16.0 | 256 | NS | 0.18 |

| (Cho-Pyr) | −98.8 | 16.6 | 230 | NS | 0.21 |

| (Cho-Abt) | −46.3 | −20.5 | 314 | −39.4 | 107 |

| (Cho-Asc) | −70.1 | 15.3 | 251 | 35.6 | 1.18 |

| (Cho-C3C) | −88.3 | 17.3 | 261 | NS | 6290 |

| (Cho-Gen) | −66.5 | 52.4 | 279 | NS | — |

| (Cho-d-Gal) | −63.3 | 50.1 | 245 | 40.15 | 3.02 |

| (Cho-Qui) | −76.3 | 18.8 | 330 | −5.83 | 0.23 |

Note: Tg = glass transition temperature; Tm = melting temperature; Tdec = decomposition temperature; [α]d = optical rotation; NS = not studied; η = zero shear viscosity measured at 0.01 s−1 and 25 °C.

3.2. Liquid–liquid phase diagrams

After confirming the chemical structures and physicochemical properties of all bio-based ILs, they were further tested for their water miscibility at 25 °C. All synthesized ILs are completely water-soluble at 25 °C, and were used thereafter to explore their suitability towards the formation of biocompatible ABS with PPG 400. Ternary phase diagrams were determined for each bio-based IL + PPG 400 + H2O at 25 °C under atmospheric pressure (Fig. 2). The solubility curves are presented both in the weight fraction and molality units [moles of PPG per kg of (IL + water) vs. moles of IL per kg of (PPG + water)]. Ternary mixtures with compositions above each binodal curve result in the formation of a two-phase system, while initial mixtures with compositions below this curve result in the formation of a homogeneous and completely miscible solution. The experimental weight fraction data corresponding to each phase diagram are provided in ESI, Tables S2 and S3.† The experimental binodal data were further fitted by the empirical relationship described by eqn (1), and are shown in Fig. 2a. The regression parameters A, B and C were estimated by the least squares regression method, and their values and corresponding standard deviations (σ) are provided in Table S4 in the ESI.† In general, good correlation coefficients were obtained for all systems, which mean that these fittings can be used to predict the phase diagram in a region where no experimental results are available. The experimental TLs, useful to ascertain the coexisting phase compositions for a given initial mixture in which the extractions were carried out, and their respective tie-line lengths (TLLs) were also determined and are provided in Table S5 in the ESI.†

Fig. 2.

Phase diagrams for ABS composed of PPG 400 + bio-based ILs + H2O in wt% (a) and in molality units (b) at 25 °C and under atmospheric pressure. (Cho-Gly) (×); (Cho-Qui) ( ); (Cho-Gal) (

); (Cho-Gal) ( ); (Cho-Pyr) (

); (Cho-Pyr) ( ), (Cho-Asc) (

), (Cho-Asc) ( ); (Cho-IA) (

); (Cho-IA) ( ). Lines correspond to the fitting of the experimental data using eqn (1).

). Lines correspond to the fitting of the experimental data using eqn (1).

The first set of solubility curves (Fig. 2a) is useful for defining their applicability and mixture compositions for a given extraction/purification step while the use of molality units allows a better understanding of the impact of each species through the phase diagram behaviour (Fig. 2b). Amongst all studied ILs, (Cho-Gly), (Cho-Qui), (Cho-Gal), (Cho-Pyr), (Cho-Asc) and (Cho-IA) are able to form two-phase systems with PPG 400. All bio-based ILs investigated in this work share the same cation; therefore, the ability to form ABS with PPG 400 depends on the anion counterpart.

(Cho-Abt), (Cho-C3C) and (Cho-Gen) are not able to form ABS with PPG 400, these being the ones that present higher octanol–water partition coefficients (Table 2).46 Octanol–water partition coefficients correspond to the partition of a particular solute between octanol and water (hydrophobic and hydrophilic layer). An exception to this pattern was observed with (Cho-IA), which may indicate that other types of interactions may govern the phase behaviour, as discussed below. In general, the ability of each bio-based IL to form two phases in the presence of ~90 wt% of PPG 400 is as follows: (Cho-Qui) ≃ (Cho-d-Gal) > (Cho-Gly) > (Cho-Pyr) > (Cho-Asc) > (Cho-IA). This trend closely correlates with the octanol–water partition values of each acid (Table 2) and thus the IL hydration aptitude and/or its affinity for water seems to rule the phase separation ability. This behaviour is in accordance with what has been observed with ABS formed by polymers and inorganic salts,20,47 in which salts with a higher charge density more easily promote the formation of two phase systems. Hence, the investigated cholinium-based ILs which form ABS seem to act as salting-out species over PPG 400 in aqueous media, however an exception was observed with (Cho-Asc). Based on its octanol–water partition coefficient, this IL should better induce the two phase formation or at least in a similar way to that displayed by (Cho-Gly). Nevertheless, it should be stressed that in polymer–IL-based ABS, the phase separation phenomenon can be more complex and polymer–IL interactions cannot be discarded.47,48

Table 2.

Logarithm of octanol–water partition coefficients (log Kow) of the acids used to synthesize bio-based ILs46

| Acids | log Kow |

|---|---|

| Indole-3-acetic | 1.71 |

| Glycolic | −1.07 |

| Pyruvic | 0.07 |

| Abietic | 4.95 |

| l-Ascorbic | −1.26 |

| Coumarin-3-carboxylic | 1.37 |

| Gentisic | 1.67 |

| d-(+)-Galacturonic | −2.61 |

| Quinic | −2.70 |

3.3. Extraction and purification of IgG

After identifying the bio-based ILs able to act as phase-forming components of ABS, the potential of these systems for the extraction and purification of IgG was studied. As a first attempt, extractions with pure IgG were carried out in order to ascertain the most promising systems which are able to efficiently extract and recover antibodies. In order to compare the performance of the novel bio-based ILs with more conventional cholinium-based counterparts, the partitioning of pure IgG was also addressed in ABS formed by PPG 400 and cholinium acetate (Cho-Ac), cholinium lactate (Cho-Lac) and cholinium chloride (Cho-Cl).44 IgG was quantified by SE-HPLC and some examples of the obtained chromatograms are depicted in Fig. 3. The percentage extraction efficiency (EEIgG%) and recovery yield (YIgG%) of IgG to the IL-rich phase are presented in Table 3. For (Cho-Ac) and (Cho-Lac) systems the preferential partitioning of IgG into the bottom phase (IL-rich phase) was observed, whereas for (Cho-Cl) no IgG was detected in both phases. These results are in good agreement with previous work wherein the same systems were studied for the extraction of BSA, and where a higher loss of the protein was observed with the system formed by (Cho-Cl).44 In the ABS constituted by (Cho-Cl) the antibody completely precipitated at the interface, meaning a recovery yield of 0%, while with (Cho-Ac)- and (Cho-Lac)-based ABS, the protein partially precipitated with a consequent negative impact on the recovery yield of IgG (YIgG% of 82 and 65%, respectively). Remarkably, and contrarily to the more conventional cholinium-based ABS, the systems formed by most of the bio-based ILs synthesized in this work, namely (Cho-Gly), (Cho-Pyr), (Cho-Asc), (Cho-d-Gal) and (Cho-Qui) allow the complete extraction and complete recovery of IgG in a single-step, i.e., EEIgG% of 100% and YIgG% of 100%. In fact, no IgG was detected at the PPG-400-rich phase (top phase) and no losses of IgG, either by visible precipitation or quantification were perceived. In these ABS, IgG completely migrated to the more hydrophilic phase (IL-rich phase). However, no IgG peak was detected in both phases of the (Cho-IA)-based ABS, suggesting that IgG was completely degraded or denatured during extraction. In fact, and contrarily to the remaining systems, in this particular case, the existence of precipitated protein at the interface was witnessed. According to the phase diagrams shown in Fig. 2, (Cho-IA) is the IL with a smaller two-phase regime meaning that it is the most hydrophobic IL investigated so far. For this particular IL, a different mixture composition was used (40 wt% of IL + 40 wt% of PPG 400 + 20 wt% of an aqueous solution containing IgG at 1 mg mL−1, due to the more restricted biphasic regime of (Cho-IA), instead of 25 wt% of IL + 30 wt% of PPG 400 + 45 wt% of an aqueous solution containing IgG at 1 mg mL−1). As a consequence, this later IL-based ABS displays a lower amount of water in the respective coexisting phases– cf. TL data in ESI, Table S5.† This lower content of water seems thus responsible for the loss of stability of the antibody. Although this IL is not adequate for the extraction of antibodies, it is interesting to note that the structural stability of DNA is maintained in the presence of (Cho-IA) as reported previously.36b

Fig. 3.

Size-exclusion chromatograms of commercial IgG of high purity in phosphate buffer aqueous solution and of the bottom phase (IL-rich phase) after the extraction of pure IgG by ABS. The IgG peak is characterized by a retention time around 15.6 min.

Table 3.

Extraction selectivities of IgG (EEIgG%) and IgG recovery yield (YIgG%) in ABS formed by an aqueous solution containing IgG at 1 mg mL−1

| Ionic liquid | YIgG% | EEIgG% | Observation |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Cho-Cl) | 0 | 0 | Precipitation |

| (Cho-Ac) | 82 ± 9 | 100 | Partial precipitation |

| (Cho-Lac) | 65 ± 5 | 100 | Partial precipitation |

| (Cho-IA) | 0 | 0 | Precipitation |

| (Cho-Qui) | 100 | 100 | No precipitation |

| (Cho-Asc) | 100 | 100 | No precipitation |

| (Cho-Gly) | 100 | 100 | No precipitation |

| (Cho-Pyr) | 100 | 100 | No precipitation |

| (Cho-d-Gal) | 100 | 100 | No precipitation |

Although no special attention was given to the presence of different IL enantiomers, since anions with chiral centres were used, and our aim was to extract and purify proteins, this is a relevant factor to be considered when considering the use of aqueous biphasic systems for the separation of racemic mixtures.49

With the exception of (Cho-IA), the newly developed bio-IL-based ABS are outstanding platforms for the complete extraction of IgG in a single-step with no losses of the protein. Previous studies9,50 with ABS composed of polyethylene glycol (PEG) with molecular weights of 6000 and 3350 g mol−1 and a phosphate-based salt have led to an extraction efficiency of IgG of 90% from both Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) and hybridoma cell culture supernatants, whereas the recovery yields were 90% and 88%, respectively. Since these ABS are formed by polymers with high molecular weights, they also display high viscosities at the coexisting phases which can be seen as a major drawback when considering the scale-up of the technology. Wu et al.51 also investigated different ABS formed by PEG and hydroxypropyl starch for IgG extraction. Despite the high extraction yields (99.2%), the authors have reported the co-precipitation of the protein in all tested systems. More recently, an integrated method for polymer–polymer based ABS and a hybrid combination of ABS with magnetic particles resulted in 84% and 92% recovery yields of IgG, respectively.52,53 Most of the studies regarding the IgG extraction addressed the use of PEG, mostly due to its more hydrophilic character, high biodegradability, low toxicity and low cost. The use of PPG 400 in the present study, having a more hydrophobic character (due to the additional methyl group at the side chain) enhances the ABS separation and the water content at the IL-rich phase, which can be beneficial for the extraction of products with biological activity. It should be taken into consideration that in our work IgG preferentially migrates to the IL-rich phase and not to the polymer-rich phase, as typically observed with more conventional polymer-based ABS.9,52

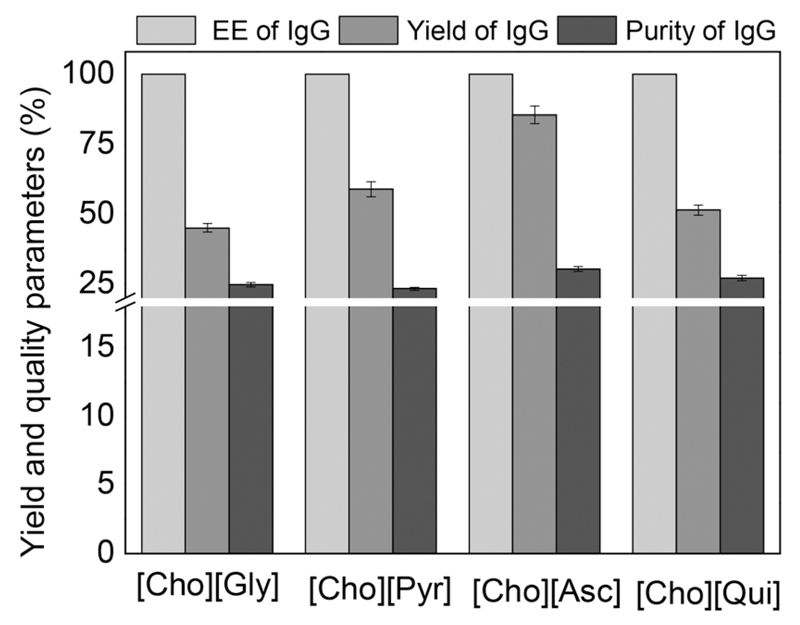

After identifying the most promising ILs for the extraction of IgG, they were employed for the extraction/purification of IgG directly from rabbit serum. ABS formed by (Cho-Gly), (Cho-Pyr), (Cho-Asc) and (Cho-Qui) at the mixture compositions described before and used for the extraction of pure IgG were investigated. In this approach it was possible to evaluate whether the presence of other contaminant proteins in serum influence the extraction of IgG and how these systems perform in terms of purification platforms. Fig. 4 depicts the results of the purification, recovery yield and extraction efficiency of IgG from rabbit serum, at the IL-rich phase (Table S6 in the ESI† presents detailed data). The quantification was carried out by SE-HPLC (examples of chromatograms are shown in Fig. S10 and S11 in the ESI†). For all studied systems, IgG completely migrates to the IL-rich phase in a single-step – extraction efficiency of 100% – following the behaviour found with the pure antibody (Table 3). However, a lower recovery yield of IgG was obtained when carrying out extractions from real serum samples. It was found that contaminant proteins are also preferentially partitioned into the IL-rich phase, although not completely, and thus allow an enhancement in the purification factor of IgG as discussed below. The migration of other proteins to the IL-rich phase is thus the major cause of this decrease in the recovery yield of IgG, either because there is a competition between all proteins to migrate to the IL-rich phase or because the phase saturation can be reached. From the bio-IL-based ABS evaluated, the system composed of (Cho-Asc) appears as the most promising with an IgG extraction efficiency of 100% and a recovery yield of 85% in the IL-rich phase. A previous study reported a pilot-scale purification of IgG from goat serum with a 58% recovery yield by modified ion-exchange chromatography,54 supporting therefore the remarkable results obtained with bio-based ILs. IgG with the highest purity level, defined as the ratio between the IgG content and the total proteins content in the IL-rich phase, was also obtained with the ABS constituted by (Cho-Asc).

Fig. 4.

Extraction efficiency of IgG (EEIgG%), IgG recovery yield (YIgG%) and IgG purity (%) from rabbit serum in ABS composed of PPG 400 (30 wt%) + bio-based IL (25 wt%) + 45 wt% of rabbit serum (diluted at 1 : 10 (v/v); pH ≈ 7; results obtained from 3 replicates).

Increases in the IgG purity of 22.5%, 30.4% and 12.2% from serum samples were achieved with ABS formed by (Cho-Asc), compared to (Cho-Gly), (Cho-Pyr) and (Cho-Qui) respectively. This best system allowed an enrichment of 58% on the IgG purity when compared against IgG present in the rabbit serum. The enhanced purity of IgG in the bio-IL-rich phase is a result of the migration of the major contaminant protein (albumin) and protein aggregates to the polymer-rich phase. Thus, and although further optimization studies are still required, the introduction of bio-based ILs in ABS can be foreseen as a promising alternative for the purification and recovery of high-cost IgG from real matrices.

As evident from the previous results, bio-IL-based ABS not only allow the complete extraction of IgG in a single-step, but also increase the purity level of IgG extracted from a real and complex matrix. However, and taking into consideration the therapeutic, diagnostic and research applications of IgG,2–6 it is important to guarantee the chemical and biological stability of the antibody after extraction and purification steps. Some aqueous solutions of ILs have been reported as adequate media for the dissolution and stabilization of proteins, such as cytochrome-c.55 It was also demonstrated that the native conformation of cytochrome-c is preserved in 50–70 wt% IL aqueous solutions.56 Jha et al.57 have proved that the structure of globular proteins remains intact in the presence of ammonium-based ILs. Dreyer and Kragl58 have demonstrated that IL-based ABS can be used to extract and stabilize enzymes. (Cho-Gly)-based ABS have been reported as an efficient extraction platform and able to maintain the structural stability of BSA.43 Based on these reports, it seems suitable that the bio-based ILs investigated herein can be used to purify and to maintain the structural integrity of proteins. Even so, no studies have been found in the literature in what concerns the effect of the investigated bio-based ILs on the stability of proteins or antibodies.

Although SE-HPLC was used as the quantification technique, simultaneously, it can be used to address the conformational and structural stability of IgG, as typically carried out with other proteins.59 SE-HPLC chromatograms of the pure IgG in PBS buffer and those after the extraction step with each ABS are shown in Fig. 3. For both standard IgG and IgG after extraction with bio-based ABS, with the exception of the system with (Cho-IA) where the complete precipitation of the protein was observed, a peak corresponding to IgG at a retention time of ~15.6 min is noticed. Some peaks at lower retention times are observed, also present in the pure IgG samples, which are an indication of protein aggregates. However, no peaks at higher retention times are observed, which could be an indication of the IgG degradation.

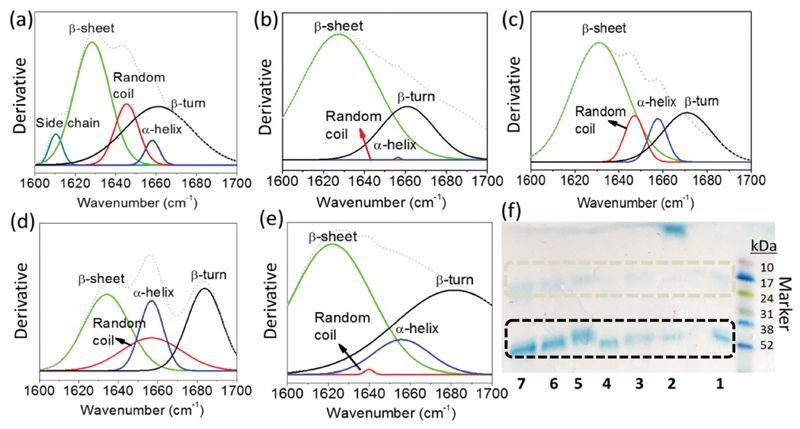

FTIR is a well established analytical technique for the analysis of the secondary structure of proteins.60 The secondary structure of proteins is frequently addressed by the fraction of α-helix, β-sheet, β-turn and random coil conformations. These fractions can be evaluated by Fourier Self-Deconvolution (FSD) in the protein amide I region.61 The structural stability of IgG was also evaluated by FTIR spectroscopy expressed in the deconvoluted form and by SDS-PAGE and the results are depicted in Fig. 5. The secondary structure of IgG in an aqueous solution of PBS (10 mM, pH 7.4) was studied for comparative analyses (Fig. 5a). At its native state, IgG contains 64% of β-sheet, 3% of α-helix, 28% of β-turn and 5% of random coil.60 As shown in Fig. 5a, the amide I region in the FTIR spectra of pure IgG in PBS buffer absorbs in the region of 1600–1690 cm−1, which corresponds to the β-sheet (~1635 cm−1), random coil (~1645 cm−1), α-helix (~1660 cm−1) and β-turn (~1670 cm−1). However, the amide I region of IgG in the presence of (Cho-IA) was found to be deviated (Fig. 5b) meaning that all the random coil and α-helix structures were transformed into β-sheet, which facilitates protein fibrillation and precipitation. These results are in full agreement with the respective SE-HPLC chromatograms and macroscopic identification of protein precipitation with this IL. On the other hand, in the presence of (Cho-Gly) and (Cho-Asc) (Fig. 5c and d) there are no major changes in the amide I region of IgG, which further corroborate the results observed by SE-HPLC. Still, in the presence of (Cho-Pyr) (Fig. 5e), a small structural deformation was recorded, although no precipitation was observed, suggesting the partial denaturation of the IgG structure.

Fig. 5.

FTIR spectra of IgG in the presence of (a) 10 mM PBS (pH 7.4), (b) 25 wt% [Cho][IA] + 30 wt% PPG 400 + H2O, (c) 25 wt% [Cho][Gly] + 30 wt% PPG 400 + H2O, (d) 25 wt% [Cho][Asc] + 30 wt% PPG 400 + H2O and (e) 25 wt% [Cho][Pyr] + 30 wt% PPG 400 + H2O. (f) SDS-PAGE of IgG at a 200 μg mL−1 concentration per lane in: PBS buffer 10 mM, pH 7.4 (1), [Cho][IA] (2), [Cho][Gly] (3), [Cho][Pyr] (4), [Cho][Asc] (5), [Cho][Qui] (6) and [Cho][d-Gal] with 25 wt% of each IL.

SDS-PAGE analysis was also employed to cover the effect of bio-based ILs on the integrity of IgG (Fig. 5f). In the presence of PBS buffer (10 mM, pH 7.4), as shown in Fig. 5f, lane 1, the two bands corresponding to the light chain and heavy chain of IgG, with a molecular weight ~20 kDa and ~50 kDa, respectively, are clearly identified. These two bands are also identified in the presence of most of the bio-based ILs investigated indicating that there is no degradation of IgG except in the presence of (Cho-IA) (lane 2 of Fig. 5f). On the other hand, in the presence of (Cho-Pyr), and although 100% of extraction of IgG was observed in the IL-rich bottom phase, the structure of IgG was found to be partially deformed as shown in the figures comprising the SE-HPLC (Fig. 3, top spectra), FTIR (Fig. 5e) and SDS-PAGE (Fig. 5f, lane 4) analyses.

In summary, amongst all bio-based ILs studied, (Cho-IA) was the only one found to be unable to maintain the structural integrity of IgG, which reflects the 0% of recovery yield gathered during the extraction steps. Remarkably, all remaining bio-IL-based ABS are suitable for the extraction/purification of IgG from complex serum samples, since they allow the complete extraction of IgG for the IL-rich phase in a single-step, a recovery yield of at least 85% and an enhancement in the purity level of ca. 58%, while preserving the structural integrity of the antibody. Further investigations on the purification of IgG are ongoing, particularly on the optimization of mixture compositions and on the incorporation of these ABS in centrifugal partition chromatography to ascertain their scale-up viability.

4. Conclusions

A new set of bio-based ILs, constituted by the cholinium cation and anions derived from plant natural acids, were synthesized and characterized. All bio-based ILs display melting temperatures below 100 °C, ranging from −20.5 to 52.4 °C, and high decomposition temperatures, at least up to 220 °C. All ILs are completely miscible with water and out of nine, six are able to form ABS with PPG 400. The respective phase diagrams were determined to ascertain the mixture compositions required to form two-phase systems, and their extraction and purification performance for IgG was then evaluated. With pure IgG samples, and with the exception of the (Cho-IA)-based ABS, all remaining systems lead to a 100% extraction efficiency and 100% recovery yield of IgG in the bio-IL-rich phase. These newly developed ABS proved to be better systems for the extraction of IgG when compared to the ABS formed by more traditional cholinium-based ILs. The most promising systems were thereafter applied to the extraction and purification of IgG from real rabbit serum samples. With real samples, the extraction efficiency of 100% of IgG in a single-step was achieved, although with a small compromise on the recovery yield (85%). Even so, and taking into consideration the current high cost of IgG at a high purity level, it was found that the best ABS leads to an increase of 58% in the IgG purity (against its purity in the original serum sample). Since IgG is currently used in therapeutic, diagnostic and research applications, it is crucial to guarantee its stability after purification. IgG was found to maintain its native structure in the presence of most of the studied bio-based ILs, except for (Cho-IA). This indicates that the synthesized bio-based ILs are protein-friendly and that their incorporation in ABS, given the obtained extraction efficiencies, recovery yields and purity levels, is a promising option for the recovery and purification of IgG from real matrices, while envisaging the widespread applicability of biopharmaceuticals at a lower cost.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This work was developed in the scope of the project CICECO-Aveiro Institute of Materials (Ref. FCT UID/CTM/50011/2013), financed by national funds through the FCT/MEC and co-financed by FEDER under the PT2020 Partnership Agreement. KP thanks CSIR, New Delhi for the grant of CSIR-Young Scientist Awardees Project and overall financial support. Analytical and centralized instrument facility department of CSIR-CSMCRI is also acknowledged. MS thanks UGC for the NET fellowship. MVQ acknowledges FCT for the doctoral grant SFRH/BD/109765/2015. APMT acknowledges the financial support from the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), Brazil for the Postdoctoral Fellowship (Ref. 201834/2015-4). MG Freire acknowledges the funds received from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Frame work Programme (FP7/2007-2013)/ERC grant agreement no. 337753. This is CSIR-CSMCRI Communication No. 089/2016.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: Source of natural acids, NMR spectra of biobased ILs, experimental data on binodal curves, and SE-HPLC data of rabbit serum samples. See DOI: 10.1039/c6gc01482h

Notes and references

- 1.Martinez-Aragón M, Goetheer ELV, de Haan AB. Sep Purif Technol. 2009;65:73–78. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lipman NS, Jackson LR, Trudel LJ, Weis-Garcia F. ILAR J. 2005;46:258–268. doi: 10.1093/ilar.46.3.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Leenaars M, Hendriksen CFM. ILAR J. 2005;46:269–279. doi: 10.1093/ilar.46.3.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Malpiedi LP, Diaz CA, Nerli BB, Pessoa A. Process Biochem. 2013;48:1242–1251. [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Buchacher A, Iberer G. Biotechnol J. 2006;1:148–163. doi: 10.1002/biot.200500037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:513–533. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Zhiqiang A. Trends in Bio/Pharmaceutical Industry. 2008;2:24–29. [Google Scholar]; (b) Carter P. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1:118–129. doi: 10.1038/35101072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andrew SM, Titus JA. Current Protocols in Cell Biology. John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azevedo AM, Rosa PA, Ferreira IF, Aires-Barros MR. J Biotechnol. 2007;132:209–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Low D, O'Leary R, Pujar NS. J Chromatogr, B: Biomed Appl. 2007;848:48–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosa P, Azevedo A, Sommerfeld S, Mutter M, Aires-Barros M, Bäcker W. J Biotechnol. 2009;139:306–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weiner C, SáRa M, Dasgupta G, Sleytr UB. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1994;44:55–65. doi: 10.1002/bit.260440109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corthier G, Boschetti E, Charley-Poulain J. J Immunol Methods. 1984;66:75–79. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(84)90249-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahluwalia VK. Green chemistry: Environmentally benign reaction. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunn PJ. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:1452–1461. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15041c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soares RRG, Azevedo AM, Van Alstine JM, Aires-Barros MR. Biotechnol J. 2015;10:1158–1169. doi: 10.1002/biot.201400532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asenjo JA, Andrews BA. J Chromatogr, A. 2011;1218:8826–8835. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2011.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quental MV, Caban M, Pereira MM, Stepnowski P, Coutinho JAP, Freire MG. Biotechnol J. 2015;10:1457–1466. doi: 10.1002/biot.201500003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Albertsson P-Å. Nature. 1958;182:709–711. doi: 10.1038/182709a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freire MG, Claudio AF, Araujo JM, Coutinho JA, Marrucho IM, Canongia Lopes JN, Rebelo LP. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:4966–4995. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35151j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gutowski KE, Broker GA, Willauer HD, Huddleston JG, Swatloski RP, Holbrey JD, Rogers RD. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:6632–6633. doi: 10.1021/ja0351802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pereira JFB, Rebelo LPN, Rogers RD, Coutinho JAP, Freire MG. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2013;15:19580–19583. doi: 10.1039/c3cp53701c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.(a) Azevedo AM, Rosa PAJ, Ferreira IF, Pisco AMMO, de Vries J, Korporaal R, Visser TJ, Aires-Barros MR. Sep Purif Technol. 2009;65:31–39. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kammoun R, Chouayekh H, Abid H, Naili B, Bejar S. Biochem Eng J. 2009;46:306–312. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hallett JP, Welton T. Chem Rev. 2011;111:3508–3576. doi: 10.1021/cr1003248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meine N, Benedito F, Rinaldi R. Green Chem. 2010;12:1711–1714. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahrens S, Peritz A, Strassner T. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2009;48:7908–7910. doi: 10.1002/anie.200903399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang B, Feng Z, Liu C, Xu Y, Li D, Ji G. J Food Sci Technol. 2015;52:2878–2885. doi: 10.1007/s13197-014-1319-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erickson B, Nelson JE, Winters P. Biotechnol J. 2012;7:176–185. doi: 10.1002/biot.201100069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohno H, Fukumoto K. Acc Chem Res. 2007;40:1122–1129. doi: 10.1021/ar700053z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumara V, Peib C, Olsenc CE, Schäfferd SJC, Parmarb VS, Malhotra SV. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2008;19:664–671. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sintra TE, Luís A, Rocha SN, Ferreira AIMCL, Goncalves F, Santos LMNBF, Neves BM, Freire MG, Ventura SPM, Coutinho JAP. ACS Sustainable Chem Eng. 2015;3:2558–2565. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.5b00751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kundu K, Paul BK, Bardhan S, Saha SK. In: Ionic Liquid-Based Surfactant Science: Formulation, Characterization, and Applications. Paul BK, Moulik SP, editors. John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2015. pp. 397–445. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hajipour AR, Rafiee F. Org Prep Proced Int. 2015;47:249–308. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song CP, Ramanan RN, Vijayaraghavan R, MacFarlane DR, Chan E-S, Ooi C-W. ACS Sustainable Chem Eng. 2015;3:3291–3298. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xie Y, Xing H, Yang Q, Bao Z, Su B, Ren Q. ACS Sustainable Chem Eng. 2015;3:3365–3372. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu X, Yang Q, Bao Z, Su B, Zhang Z, Ren Q, Yang Y, Xing H. Chem – Eur J. 2015;21:9150–9156. doi: 10.1002/chem.201500306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fukaya Y, Iizuka Y, Sekikawa K, Ohno H. Green Chem. 2007;9:1155–1157. [Google Scholar]

- 36.(a) Sharma M, Mondal D, Singh N, Trivedi N, Bhatt J, Prasad K. RSC Adv. 2015;5:40546–40551. [Google Scholar]; (b) Mukesh C, Mondal D, Sharma M, Prasad K. Chem Commun. 2013;49:6849–6851. doi: 10.1039/c3cc42829j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mazid RR, Divisekera U, Yang W, Ranganathan V, MacFarlane DR, Cortez-Jugo C, Cheng W. Chem Commun. 2014;50:13457–13460. doi: 10.1039/c4cc05086j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patel R, Kumari M, Khan AB. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2014;172:3701–3720. doi: 10.1007/s12010-014-0813-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharma M, Chaudhary JP, Mondal D, Meena R, Prasad K. Green Chem. 2015;17:2867–2873. [Google Scholar]

- 40.West RJ, Davis JW, Pottenger LH, Banton MI, Graham C. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2007;26:862–871. doi: 10.1897/06-327r.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Almeida MR, Passos H, Pereira MM, Lima ÁS, Coutinho JAP, Freire MG. Sep Purif Technol. 2014;128:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Merchuk JC, Andrews BA, Asenjo JA. J Chromatogr, B: Biomed Appl. 1998;711:285–293. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(97)00594-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pereira MM, Cruz RAP, Almeida MR, Lima AS, Coutinho JAP, Freire MG. Process Biochem. 2016;51:781–791. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Quental MV, Caban M, Pereira MM, Stepnowski P, Coutinho JAP, Freire MG. Biotechnol J. 2015;10:1457–1466. doi: 10.1002/biot.201500003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Plechkova NV, Seddon KR. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;37:123–150. doi: 10.1039/b006677j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.ChemSpider. The free chemical database. http://www.chemspider.com.

- 47.Freire MG, Pereira JFB, Francisco M, Rodriguez H, Rebelo LPN, Rogers RD, Coutinho JAP. Chem – Eur J. 2012;18:1831–1839. doi: 10.1002/chem.201101780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Neves CMSS, Shahriari S, Lemus J, Pereira JFB, Freire MG, Coutinho João AP. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2016;18:20571–20582. doi: 10.1039/c6cp04023c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu H, Yao S, Qian G, Yao T, Song H. J Chromatogr, A. 2015;1418:150–157. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2015.09.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Azevedo AM, Rosa PAJ, Ferreira IF, Aires-Barros MR. J Biotechnol. 2007;132:209–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu Q, Lin DQ, Yao SJ. J Chromatogr, B: Biomed Appl. 2013;928:106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2013.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Silva MF, Fernandes-Platzgummer A, Aires-Barros MR, Azevedo AM. Sep Purif Technol. 2014;132:330–335. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dhadge VL, Rosa SA, Azevedo A, Aires-Barros R, Roque AC. J Chromatogr, A. 2014;1339:59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2014.02.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Levison PR, Koscielny ML, Butts ET. Bioseparation. 1990;1:59–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kohno Y, Saita S, Murata K, Nakamura N, Ohno H. Polym Chem. 2011;2:862–867. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wei W, Danielson ND. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12:290–297. doi: 10.1021/bm1008052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jha I, Venkatesu P. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2015;17:20466–20484. doi: 10.1039/c5cp01735a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dreyer S, Kragl U. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2008;99:1416–1424. doi: 10.1002/bit.21720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hong P, Koza S, Bouvier ESP. J Liq Chromatogr Relat Technol. 2012;35:2923–2950. doi: 10.1080/10826076.2012.743724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kong J, Yu S. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin. 2007;39:549–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7270.2007.00320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wi S, Pancoska P, Keiderling TA. Biospectroscopy. 1998;4:93–106. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6343(1998)4:2<93::aid-bspy2>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.