Abstract

Astrocytes integrate and process synaptic information and exhibit calcium (Ca2+) signals in response to incoming information from neighboring synapses. The generation of Ca2+ signals is mostly attributed to Ca2+ release from internal Ca2+ stores evoked by an elevated metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR) activity. Different experimental results associated the generation of Ca2+ signals to the activity of the glutamate transporter (GluT). The GluT itself does not influence the intracellular Ca2+ concentration, but it indirectly activates Ca2+ entry over the membrane. A closer look into Ca2+ signaling in different astrocytic compartments revealed a spatial separation of those two pathways. Ca2+ signals in the soma are mainly generated by Ca2+ release from internal Ca2+ stores (mGluR-dependent pathway). In astrocytic compartments close to the synapse most Ca2+ signals are evoked by Ca2+ entry over the plasma membrane (GluT-dependent pathway). This assumption is supported by the finding, that the volume ratio between the internal Ca2+ store and the intracellular space decreases from the soma towards the synapse. We extended a model for mGluR-dependent Ca2+ signals in astrocytes with the GluT-dependent pathway. Additionally, we included the volume ratio between the internal Ca2+ store and the intracellular compartment into the model in order to analyze Ca2+ signals either in the soma or close to the synapse. Our model results confirm the spatial separation of the mGluR- and GluT-dependent pathways along the astrocytic process. The model allows to study the binary Ca2+ response during a block of either of both pathways. Moreover, the model contributes to a better understanding of the impact of channel densities on the interaction of both pathways and on the Ca2+ signal.

Author summary

Astrocytes are considered as active partners in neural information processing, because they integrate and process synaptic information and control synaptic transmission. Neuronal transmitter release induces the generation of Ca2+ signals in astrocytes. The functional role of astrocytic Ca2+ signals is still under debate. However, experimental results were able to show that astrocytic Ca2+ signaling acts to control local network activity, which plays an important role in diseases like epilepsy. Thus, it is of special interest to investigate the underlying mechanisms for Ca2+ signals in astrocytes in order to understand the role of astrocytes in neural network activity. Two different mechanisms are known to be responsible for the generation of Ca2+ signals in astrocytes. These mechanisms are the release of Ca2+ from internal Ca2+ stores and the entry of Ca2+ through the plasma membrane. We studied the interaction of those two different mechanisms for the generation of Ca2+ signals and found that these mechanisms are spatially separated along the astrocytic processes.

Introduction

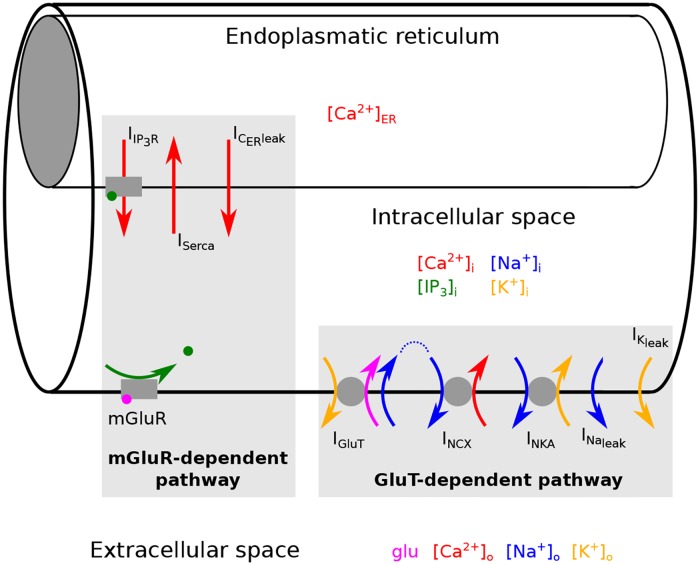

Astrocytes integrate and process synaptic information and by doing so generate calcium (Ca2+) signals in response to neurotransmitter release from neighboring synapses [1]. Ca2+ signals in astrocytes are largely attributed to an elevated metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR) activity, which stimulates the phospholipase C and the production of the second messenger inositol trisphosphate (IP3). The binding of IP3 to receptors at internal Ca2+ stores (endoplasmatic reticulum) induces IP3 and Ca2+-dependent Ca2+ release into the intracellular space [2–7] (see mGluR-dependent pathway in Fig 1).

Fig 1. Generation of Ca2+ signals in an astrocyte.

We consider astrocytic compartments which consist of three parts: the intracellular space, the internal Ca2+ store (endoplasmatic reticulum) and the extracellular space. Ca2+ signals in the intracellular space are generated by two different pathways: the metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR)-dependent pathway and the glutamate transporter (GluT)-dependent pathway. The mGluR-dependent pathway describes the glutamate dependent production of IP3, which then evokes IP3 and Ca2+ dependent exchange of Ca2+ between the intracellular space and the endoplasmatic reticulum. The GluT-dependent pathway describes the GluT driven transport of Ca2+ between the extracellular and the intracellular space.

Experimental results, however, showed not only a clear attenuation of the Ca2+ signal during an inhibition of the mGluR, but also during a block of the glutamate transporter (GluT) [7, 8]. The glutamate transporter itself does not influence the intracellular Ca2+ concentration, but it indirectly activates Ca2+ entry over the membrane mediated by the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger [9] (see GluT-dependent pathway in Fig 1). The uptake of one glutamate molecule mediated by the glutamate transporter is accompanied by the transport of three sodium (Na+) ions into the astrocyte and one potassium (K+) ion out of the astrocyte. An inwardly directed Na+ gradient and an outwardly directed K+ gradient promote the glutamate uptake by the glutamate transporter and glutamate accumulation in the astrocyte. The Na+-K+-ATPase maintains the Na+-K+ concentration gradient and favors the glutamate transport [10]. In close proximity to glutamate transporters high concentrations of Na+/Ca2+ exchangers have been observed [9]. During a rapid rise of the Na+ concentration the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger works in the reverse mode and transports Na+ out of the astrocyte while transporting Ca2+ into the astrocyte. Thereby the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger serves as an additional transient source of Ca2+ and the intracellular Ca2+ concentration increases [9].

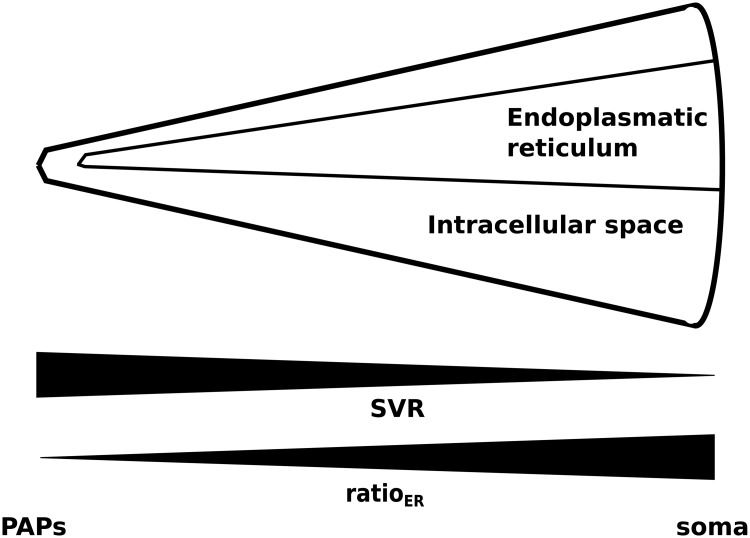

Therefore, at least two different mechanisms contribute to the generation of Ca2+ signals in astrocytes. A closer look into Ca2+ signaling in different astrocytic compartments revealed a spatial separation of those two pathways. In the soma Ca2+ signals are mainly evoked on the mGluR-dependent pathway, whereas in perisynaptic astrocytic processes (PAPs) most Ca2+ signals are evoked by Ca2+ entry over the plasma membrane [11]. These results are supported by the finding, that astrocytic compartments close to the synapse are devoid of internal Ca2+ stores and the volume ratio of internal Ca2+ stores compared to the intracellular space increases towards the soma. Moreover, the surface volume ratio decreases along the astrocytic process from the PAPs towards the soma, because processes become increasingly thinner (see Fig 2) [12].

Fig 2. Changes of the astrocytic surface to volume ratio (SVR) and the volume ratio of internal Ca2+ stores compared to the intracellular space (ratioER) for astrocytic compartments along the astrocytic process.

A small ratioER corresponds to astrocytic compartments close to the synapse (perisynaptic astrocytic processes (PAPs)) and a high ratioER corresponds to astrocytic regions at the soma.

Based on the findings cited above we hypothesized that the underlying mechanisms for Ca2+ signals differ between astrocytic compartments. The mGluR-dependent pathway is mainly present close to the astrocytic soma, while the GluT-dependent pathway dominates Ca2+ signals in PAPs. So far most mathematical models attribute astrocytic Ca2+ dynamics solely to mGluRs and neglect Ca2+ entry through the membrane. In order to test whether the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger serves as a source for Ca2+ signals in PAPs, we propose a mathematical model, which incorporates glutamate driven Ca2+ responses evoked by simultaneous binding of glutamate to mGluR’s and transport of glutamate by GluT while taking the volume ratio of internal Ca2+ stores into account. With the help of the model we investigated how the volume ratio between the internal Ca2+ store and the intracellular space affects Ca2+ signaling evoked on the mGluR- and GluT-dependent pathway in different astrocytic compartments along astrocytic processes from the synapse towards the soma.

Methods

We used a system of ordinary differential equations to describe the changes of the ion concentrations, the membrane voltage and the concentration of IP3 in a single astrocytic compartment (see Fig 1) of an astrocytic process. Glutamate dependent Ca2+ signals are evoked through two different pathways (see Fig 1). One pathway is driven by the activity of the metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR-dependent pathway). The other depends on the activity of the glutamate transporter (GluT-dependent pathway). In the mGluR-dependent pathway glutamate binds to the metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR) leading to an enhanced production of the second messenger IP3 and the subsequent IP3 dependent Ca2+ release from the internal Ca2+ store (endoplasmatic reticulum). The exchange of Ca2+ between the endoplasmatic reticulum (ER) and the intracellular space is mediated by three currents: the IP3 receptor current (IIP3R), which describes the IP3 dependent Ca2+ release from the ER, the Ca2+ current of the SERCA pump (ISerca), which transports Ca2+ back into the ER, and a Ca2+ leak current (ICERleak). The IP3 receptor channel current is influenced by the concentration of the second messenger IP3, by the fraction h of active IP3 receptor channels, and by the Ca2+ concentration itself. The GluT-dependent pathway describes the transport of Ca2+ through the membrane driven by the activity of the glutamate transporter (GluT). This pathway includes the glutamate transporter, the Na+/K+-ATPase (NKA), the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX), and the Na+ and K+ leak currents. The Ca2+ transport through the membrane is influenced by the intra- and extracellular Ca2+, Na+ and K+ concentrations, and the membrane voltage V.

Geometry of the astrocytic model compartment

We consider small astrocytic compartments, which have a cylindrical shape. Each astrocytic compartment consists of three parts: the internal Ca2+ store (endoplasmatic reticulum), the intracellular space, and the extracellular space (see Fig 1). The internal Ca2+ store and the intracellular space are considered as two cylinders with different diameter, which lie within each other. The volume of the intracellular space includes the volume of the internal Ca2+ store. The intracellular space is surrounded by the extracellular space. The volume of the extracellular space is set equal to the volume of the intracellular space. Flow of ions to neighboring compartments is not considered. Thus, only the curved surface area of the cylinder is considered.

For the change of the ion concentration within the intracellular space or the internal Ca2+ store (see Eq 2), we consider the sum of all ionic currents carrying the respective ion (∑Iion) multiplied with the area A, the ionic current is flowing through, and divided by the volume Vol of the space the ions are located in. Both A and Vol are scaled by the length l of the compartment. Therefore, the fraction does not depend on l and lateral diffusion of ions was neglected.

For each astrocytic compartment the surface area and the volume of both the internal Ca2+ store and the intracellular space change along the astrocytic process. The diameter of the intracellular space increases from astrocytic compartments close to the synapse towards astrocytic compartments at the soma (see Fig 2). Thus, the surface area and the volume of the intracellular space increase from the synapse to the soma, but the surface volume ratio (SVR) decreases. The volume ratio between the internal Ca2+ store and the intracellular space increases from astrocytic compartments close to the synapse towards astrocytic compartments at the soma. Astrocytic compartments close to the synapse do not contain internal Ca2+ stores (ratioER = 0) (see Fig 2).

Within a single astrocytic compartment the diameter of the internal Ca2+ store is smaller than the diameter of the intracellular space. The volume of the internal Ca2+ store is equal to the volume of the intracellular space reduced by the factor ratioER. Consequently, the surface area of the internal Ca2+ store is reduced by the factor compared to the surface area of the intracellular space. Thus, the volume ratio between the internal Ca2+ store and the intracellular space determines the change of the surface volume ratio () of the internal Ca2+ store along the astrocytic process.

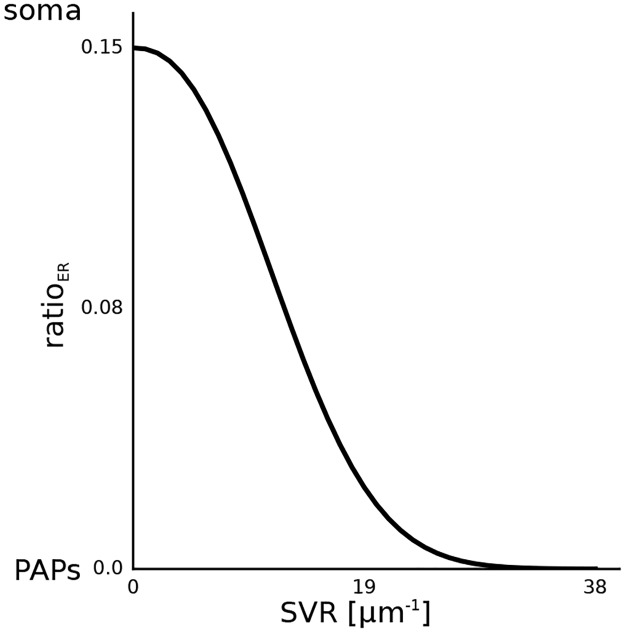

Along the astrocyte process, the surface volume ratio (SVR) and the volume ratio between the internal Ca2+ store and the intracellular space depend on each other, and the relationship (see [12] and Fig 3) is quantified by:

| (1) |

Fig 3. The volume ratio of the endoplasmatic reticulum (ER) as a function of the surface volume ratio (SVR).

The data has been adapted from [12].

Dynamics of the ion concentrations, the membrane voltage and the concentration of IP3

Dynamics of ion concentrations

The change of the ion concentration is given by:

| (2) |

and depends on the sum of all ionic currents carrying the respective ion (∑Iion) multiplied with the area (A), the ionic currents are flowing through, and divided by the volume (Vol) of the space the ions are located in and the Faraday constant (F). The change of the intracellular Ca2+ concentration is determined by currents crossing either the membrane of the internal Ca2+ store or of the outer cell membrane. For that reason the change of the intracellular Ca2+ concentration reads as follows:

| (3) |

where A denotes the area of the outer cell membrane, is the area of the internal Ca2+ store and the volume of the intracellular space is defined as Vol.

The change of the Ca2+ concentration in the ER is determined by currents crossing the membrane of the ER:

here and Vol ⋅ ratioER describe the area and the volume of the internal Ca2+ store, respectively.

The change of the intracellular Na+ and K+ concentrations are described by the following equations:

Dynamics of the membrane voltage

The change of the membrane voltage V is determined by:

The right hand side of the equation consists of the sum of all ionic membrane currents with the consideration of carried charges per ion (see Fig 1). Cm is the membrane capacitance. Note, that the transport of sodium and potassium mediated by the glutamate transporter lead to a net transfer of two positive charges per cycle across the membrane.

Extracellular ion concentrations

The changes of the extracellular Ca2+, Na+ and K+ concentrations are determined by:

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

We calculated the extracellular concentration as a function of the intracellular concentration under the assumption that the volume of the intracellular and extracellular space of an astrocytic compartment are the same and the overall concentration in the intracellular and the extracellular space of an astrocytic compartment stays constant. Values of model parameters can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Initial values of the ion concentrations, the membrane voltage, IP3 and the fraction of the activated IP3 receptor channels.

For the calculation of [Ca2+]ER, [IP3]i and h see Model section Model parameter values.

IP3 production and degradation

The concentration change of the second messenger IP3 is determined by the production and degradation of IP3. The production is mediated by the phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C β (PLCβ) and the phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C δ (PLCδ). The degradation is mediated by the IP3 3-kinase (IP3-3K) and the inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase (IP-5P) [13].

The production of IP3 by the phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C (PLC) β is linked to the level of the extracellular glutamate concentration g. The maximal rate of IP3 production by PLCβ is described by vβ and the glutamate affinity of the receptor is set by KR. Kp is the Ca2+/PLC-dependent inhibition factor and Kπ determines the Ca2+ affinity of PLC.

The maximal rate of IP3 production by PLCδ is described by vδ. The activity of PLCδ is inhibited according to the inhibition constant kδ. The Ca2+ affinity of PLCδ is set by KPLCδ.

The maximal degradation rate of IP3 by IP3-3K is determined by v3K. KD is the Ca2+ affinity of IP3-3K and K3 is the IP3 affinity of IP3-3K.

The degradation of IP3 through dephosphorylation by the inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase (IP-5P) depends on the maximal rate, r5P, of degradation by IP-5P. Values of model parameters can be found in Table 2.

Table 2. Model parameters for the production and degradation of IP3.

IP3 production is mediated by PLCβ and PLCδ and IP3 degradation is mediated by IP3—3K and IP—5P.

Currents

Intracellular dynamics

Ca2+ current through IP3 receptor channels. The Ca2+ current through the IP3 receptor channel was taken from [14]:

| (7) |

rC determines the maximal rate of transported Ca2+ ions. The dissociation of IP3 and Ca2+ by the channels’ subunits is determined by d1 and d5.

The probability of the channel to be in the open state is characterized by the term and depends on the intracellular IP3 concentration, the intracellular Ca2+ concentration and the fraction h of activated IP3 receptor channels. The channel can either be in the activated or the inactivated state. As proposed in [14] the channel is in the activated state when one Ca2+ ion and one IP3 molecule bind to two out of the three subunits of the channel. The channel is in the inactivated state when a second Ca2+ ion binds to the third subunit. The current strength is proportional to the Ca2+ gradient between the ER and the intracellular space, ([Ca2+]ER—[Ca2+]i). In order to relate the current strength to the volume of the intracellular space, the current is multiplied with the volume Vol. The current is normalized by the area A. Values of model parameters can be found in Table 3.

Table 3. Model parameters for the Ca2+ currents through the membrane of the endoplasmatic reticulum: The IP3 receptor channel, the SERCA pump and the Ca2+ leak current.

Activation of IP3 receptor channels. The fraction h of activated IP3 receptor channels was taken from [14],

| (8) |

a2 determines the IP3R binding rate for Ca2+ inhibition. The inactivation dissociation constants of Ca2+ and IP3 are d2 and d3, respectively. Values of model parameters can be found in Table 4.

Table 4. Model parameters for the dynamics of the fraction h of activated IP3 receptor channels.

SERCA pump. The transport of Ca2+ ions into the endoplasmatic reticulum mediated by the SERCA pump was taken from [14],

| (9) |

The maximal rate of Ca2+ uptake by the SERCA pump is determined by vER. KER determines the Ca2+ affinity of the SERCA pump. In order to relate the current strength to the volume of the intracellular space, the current is multiplied with the volume Vol. The current is normalized by the area A.

The SERCA current depends on the intracellular Ca2+ concentration [Ca2+]i and is modeled by a Hill rate expression with an exponent 2. Values of model parameters can be found in Table 3.

Ca2+ leak from the ER. The Ca2+ leak from the endoplasmatic reticulum was taken from [14]:

| (10) |

where rL is the leak rate.

The leak of Ca2+ ions from the endoplasmatic reticulum into the cytosol depends on the difference of the Ca2+ concentration in the ER, [Ca2+]ER, and in the intracellular space [Ca2+]i. In order to relate the current strength to the volume of the intracellular space, the current is multiplied with the volume Vol. The current is normalized by the area A. Values of model parameters can be found in Table 3.

Transmembrane transporters

Glutamate transporter. The transport of glutamate mediated by the glutamate transporter (GluT) is determined by:

| (11) |

where IGluTmax is the maximal transport current of the glutamate transporter. The half saturation constants of Na+, K+ and glutamate are given by KGluTmN, KGluTmK and KGluTmg, respectively. The half saturation constant of K+ is not known from experiments. Since the half saturation constant of Na+ is close to its intracellular resting concentration, we set the half saturation constant of K+ close to its extracellular resting concentration.

The transport of glutamate is coupled to the co-transport of three Na+, one Glu- and one H+, and the counter-transport of one K+ [15, 16]. It results in a net flux of two positive charges per cycle, which is included in the calculation of the membrane potential. The concentrations of H+ and Glu- in the different compartments, however, are excluded from the model, because they do not influence any of the other model variables under consideration. Values for the model parameters are listed in Table 5. Additionally, there is a non-stochiometric anion (Cl-) current coupled to the glutamate transporter [17]. Inclusion of this current into the equation for the membrane voltage, however, led to minor changes in the simulation results, as long as its maximum conductance was chosen with a physiologically reasonable range (10-7 ). It was, therefore, not considered further.

Table 5. Model parameters for the currents through the plasma membrane: The glutamate transporter, the Na+/K+ ATPase, the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger and the leak currents for Na+ and K+.

The determination of the model parameters IGluTmax and INKAmax can be found in the Results section Na+ transport by the glutamate transporter. The definition of the model parameter KGluTmK can be found in the Model section Glutamate Transporter. For the calculation of gNaleak and gKleak see Model section Model parameter values.

| Parameter | Value | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Glutamate Transporter | ||

| IGluTmax | 0.68 | see text |

| KGluTmN | 15 mM | [27] |

| KGluTmK | 5 mM | see text |

| KGluTmg | 34 μM | [27] |

| Na+/K+ ATPase | ||

| INKAmax | 1.52 | see text |

| KNKAmN | 10 mM | [18] |

| KNKAmK | 1.5 mM | [18] |

| Na+/Ca2+ exchanger | ||

| INCXmax | 0.1 | see text |

| KNCXmN | 87500 μM | [18] |

| KNCXmC | 1380 μM | [18] |

| ksat | 0.1 | [18] |

| η | 0.35 | [18] |

| Leak Currents | ||

| gNaleak | 0.0065 | see text |

| gKleak | 0.0791 | see text |

Na+/K+-ATPase. The transport of Na+ and K+ against its concentration gradient is performed by the Na+/K+-ATPase (NKA). We applied the mathematical expression of [18] in a simplified form:

| (12) |

Here, INKAmax defines the maximal pumping activity of the NKA. KNKAmN and KNKAmK determine the half saturation constants of Na+ and K+, respectively.

The Na+/K+-ATPase (NKA) transports three Na+ ions out of the cell and two K+ ions into the cell. Its pumping activity depends on the intracellular Na+ concentration [Na+]i and the extracellular K+ concentration [K+]o [19]. Values of model parameters can be found in Table 5.

Na+/Ca2+ exchanger. The Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) mediates the exchange of three Na+ ions with one Ca2+ ion. We applied the mathematical description of the NCX of [18]:

| (13) |

INCXmax is the maximal pump current of the exchanger. The half saturation constants for Na+ and Ca2+ are given by KNCXmN and KNCXmC. The position of the energy barrier η controls the voltage dependence. ksat is a saturation factor ensuring saturation at large negative potentials.

The exchanger works either in the forward or in the reverse mode. In the forward mode Ca2+ is transported out of the astrocyte and Na+ is transported into the astrocyte. The reverse mode works the other way round. A switch into the reverse mode is induced by an increased intracellular Na+ concentration [20]. The current strength of the NCX depends on the intra- and extracellular Na+ and Ca2+ concentrations [Na+]i, [Na+]o, [Ca2+]i and [Ca2+]o. Values of model parameters can be found in Table 5.

Leak currents. The leak currents of Na+ and K+ are given by:

| (14) |

| (15) |

where gNaleak and gKleak are the corresponding conductances of the Na+ and K+ currents. The Nernst potentials of Na+ and K+ are ENa and EK. Values of model parameters can be found in Table 5.

Neuronal stimulation of the astrocyte compartment

The release of glutamate from an activated nearby synapse is calculated using the Tsodykis and Makram model [21, 22] in its adapted form published by Wallach and colleagues [7].

where x and y represent the fraction of resources in the recovered and active states, respectively. During each spike a fraction of active synaptic resources is released into the synaptic cleft, and the time constant τrec determines the recovery of these resources. The fraction of active synaptic resources y increases with each spike and the step increase of y is determined by U0. In the absence of a spike y decays back to a baseline level with time constant τfacil. The product r(t) corresponds to the ratio of glutamate (g) which is released during a spike of the sequence s. The change of the glutamate concentration in the synaptic cleft is determined by the total glutamate content of readily releasable vesicles (GT) and the volume ratio between the synaptic vesicles and the synaptic cleft (ρC). Glutamate is removed from the synaptic cleft with the time constant τclear. Values of model parameters can be found in Table 6.

Table 6. Parameters for the Tsodyks and Markram model.

Model parameter values

The initial values of [IP3]i, the fraction h of active IP3 receptor channels, and [Ca2+]ER and the model parameters gNaleak and gKleak were determined as follows. Since the model parameters for the production and degradation of IP3 and the intracellular resting concentration of Ca2+ were known from literature, the zero of d[IP3]i/dt revealed the initial concentration of IP3. In the same way the initial ratio of activated IP3 receptor channels, h, and the initial concentration of the Ca2+ concentration in the endoplasmatic reticulum was calculated. In this way a stable resting state was ensured. The model parameter gNaleak was calculated by setting d[Na+]i/dt equal to zero and solving the equation for gNaleak. The model parameter gKleak was calculated the same way by setting d[K+]i/dt equal to zero.

Computational methods

All simulations were performed with Python 2.7 using the packages Brian [28], NumPy and Matplotlib. The Brian Simulator used the Euler integration as numerical integration method for the non-linear differential equations with time step dt = 1ms.

Results

Influence of ratioER on the mGluR-driven Ca2+ oscillations

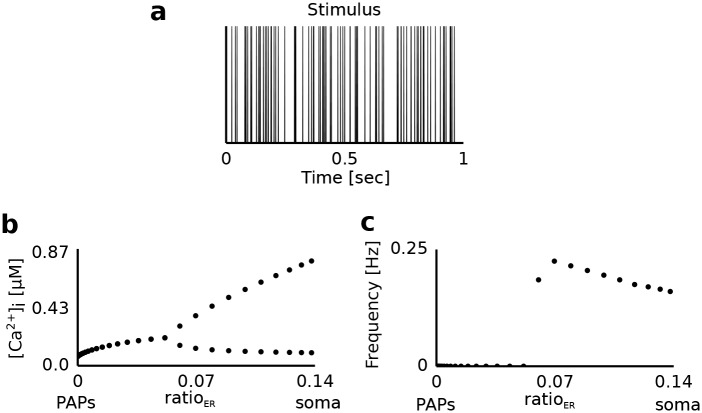

First, we analyzed the generation of mGluR-dependent Ca2+ signals along the astrocytic process. For this reason we varied the volume fraction of the internal Ca2+ store (ratioER), which changes along the astrocytic process (Fig 3), and studied the amplitude and the frequency of the Ca2+ signals (Fig 4). All currents related to the GluT-dependent pathway (IGluT, INKA, INCX) were set to zero.

Fig 4. Dynamics of the Ca2+ concentration in the intracellular compartment during synaptic activation.

a Sample stimulus (spikes). The astrocytic compartment was stimulated for 200 seconds with a Poisson spike train of 100 Hz. The corresponding glutamate concentration in the extracellular compartment as a function of time was calculated using the Tsodyks-Markram model. b [Ca2+]i for different values of the volume ratio (ratioER) between the internal Ca2+ store and the intracellular compartments. The upper and lower symbols for ratioER>0.06 denote the average height of peaks and troughs of the emerging Ca2+ oscillations (in [μM]). For ratioER≤0.06 no Ca2+ oscillations were present and symbols denote the average concentration of Ca2+ over the stimulation period. c Frequency of Ca2+ oscillations as a function of ratioER.

Astrocytic compartments with a high volume fraction of the internal Ca2+ store (ratioER>0.06) showed Ca2+ oscillations (Fig 4b). These compartments corresponded to astrocytic regions close to the soma. A reduction of ratioER decreased the amplitude of the Ca2+ oscillations. This was caused by the weaker Ca2+ influx into the cytoplasm through the smaller surface area of the internal Ca2+ store. Astrocytic compartments closer to the synapse (0<ratioER<0.06) did not show Ca2+ oscillations, but an increase of the intracellular Ca2+ concentration. However, when the astrocytic compartment was devoid of the internal Ca2+ store (ratioER = 0), we observed an unchanged intracellular Ca2+ concentration. Different stimulation frequencies led to qualitatively similar behavior (data not shown). In particular, the critical value of ratioER = 0.06 for the onset of oscillations remained the same.

Na+ transport by the glutamate transporter of the GluT-dependent pathway

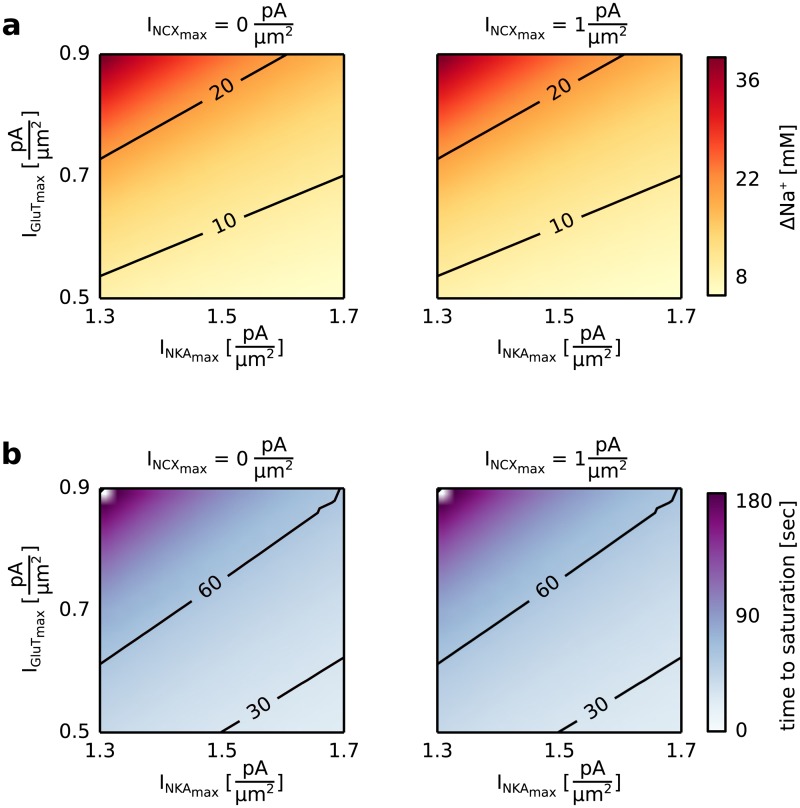

The Ca2+ entry through the plasma membrane mediated by the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger is driven by a Na+ accumulation in the intracellular space. The glutamate transporter (GluT), the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) and the Na+-K+-ATPase (NKA) determine the intracellular Na+ concentration. For this reason we analyzed the increase of the intracellular Na+ concentration as a function of the maximal pump currents of the glutamate transporter (IGluTmax), the Na+-K+-ATPase (INKAmax), and the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (INCXmax).

The maximal pump current of the GluT (IGluTmax) and the NKA (INKAmax) had a strong effect on the accumulation of Na+ in the astrocyte, while changes of the maximal pump current of the NCX (INCXmax) showed no effect (see Fig 5). The accumulation of Na+ in the intracellular space was highest for a high maximal pump current of GluT and a low maximal pump current of NKA (see Fig 5a). While the GluT transported Na+ into the astrocyte, the NKA counteracted this effect by pumping Na+ out of the astrocyte and led to a saturation of [Na+]i at lower concentration levels. The time until saturation was lowest for a low maximal pump current of the GluT and a high maximal pump current of the NKA (see Fig 5b). A low maximal pump current of the GluT resulted in a small Na+ accumulation in the intracellular space, which saturated faster for a high Na+ transport out of the astrocyte mediated by the NKA.

Fig 5. Increase of the Na+ concentration in the intracellular compartment, [Na+]i, during a constant extracellular glutamate concentration for different values of the maximal pump currents of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (INCXmax), the glutamate transporter (IGluTmax), the Na+/K+-ATPase (INKAmax).

The astrocytic compartment was stimulated for 200 seconds with a constant extracellular glutamate concentration of 100 μM. The surface volume ratio (SVR) was set equal to 1 μm-1, which corresponds to astrocytic compartments close to the soma. a [Na+]i after 200 seconds with respect to its resting concentration ([Na+]rest = 15 mM, Δ Na+ = [Na+]End—[Na+]rest) for a maximal pump current of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (INCXmax) equal to 0 (left) or equal to 1 (right) and different values of the maximal pump current of the glutamate transporter (IGluTmax) and the Na+/K+-ATPase (INKAmax). b Time to reach saturation for a maximal pump current of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (INCXmax) equal to 0 (left) or equal to 1 (right) and different values of the maximal pump current of the glutamate transporter (IGluTmax) and the Na+/K+-ATPase (INKAmax). The time to saturation was defined as the time required for the intracellular Na+ concentration to remain on a constant concentration.

In experiments the increase of the intracellular Na+ concentration in response to external stimulation with glutamate ranges from 10 mM to 20 mM saturating with increasing glutamate concentrations [29] and is performed in under 60 seconds [30]. For the following simulations we chose a parameter combination of the maximal pump currents of the GluT and the NKA which revealed the desired results for the increase of the intracellular Na+ concentration and the time to saturation (IGluTmax = 0.68 and INKAmax = 1.52 .).

Ca2+ transport through the plasma membrane

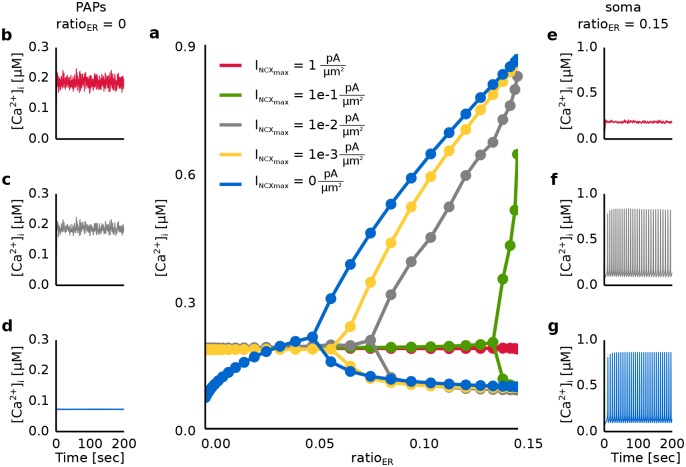

As a next step, we analyzed how the Ca2+ transport through the membrane mediated on the GluT-dependent pathway affects mGluR-dependent Ca2+ signals along the astrocytic process. Different regions of the astrocytic process were simulated by changing the volume fraction of the internal Ca2+ store (ratioER). We analyzed the influence of the GluT-dependent pathway on the Ca2+ signal by changing the maximal pump currents of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (INCXmax) and the glutamate transporter (IGluTmax).

First, we analyzed the impact of Ca2+ transport through the membrane mediated by the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger on the intracellular Ca2+ signal along the astrocytic process (see Fig 6). During a block of the Ca2+ transport through the membrane (INCXmax = 0 ) Ca2+ oscillations were only observed for a high volume fraction of the internal Ca2+ store (ratioER>0.06) (see Fig 6a and 6g). An increase of the maximal pump current of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (INCXmax > 0 ) shifted the critical value of ratioER for the onset of Ca2+ oscillations to higher values (see Fig 6a), culminating in a total suppression of the Ca2+ oscillations (see Fig 6e). In astrocytic compartments, which were devoid of the internal Ca2+ store (ratioER = 0), Ca2+ was transported into the astrocyte and the intracellular Ca2+ concentration increased (see Fig 6b and 6c).

Fig 6. Dynamics of the Ca2+ concentration in the intracellular compartment during synaptic activation for different values of the maximal pump current of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (INCXmax).

The astrocytic compartment was stimulated for 200 seconds with a Poisson spike train of 100 Hz. The corresponding glutamate concentration in the extracellular compartment as a function of time was calculated using the Tsodyks and Markram model. a [Ca2+]i as a function of the volume ratio (ratioER) of internal Ca2+ stores and the maximal pump current of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (INCXmax). The upper and lower symbols denote the average height of peaks and troughs of the emerging Ca2+ oscillations (in [μM]). In case no oscillations were present symbols denote the average concentration of Ca2+ over the stimulation period. b-d Time course of the Ca2+ concentration for ratioER = 0 and INCXmax equal to 0 (blue), 0.01 (gray) and 1 (red). e-g Time course of the Ca2+ concentration for ratioER = 0.15 and INCXmax equal to 0 (blue), 0.01 (gray) and 1 (red).

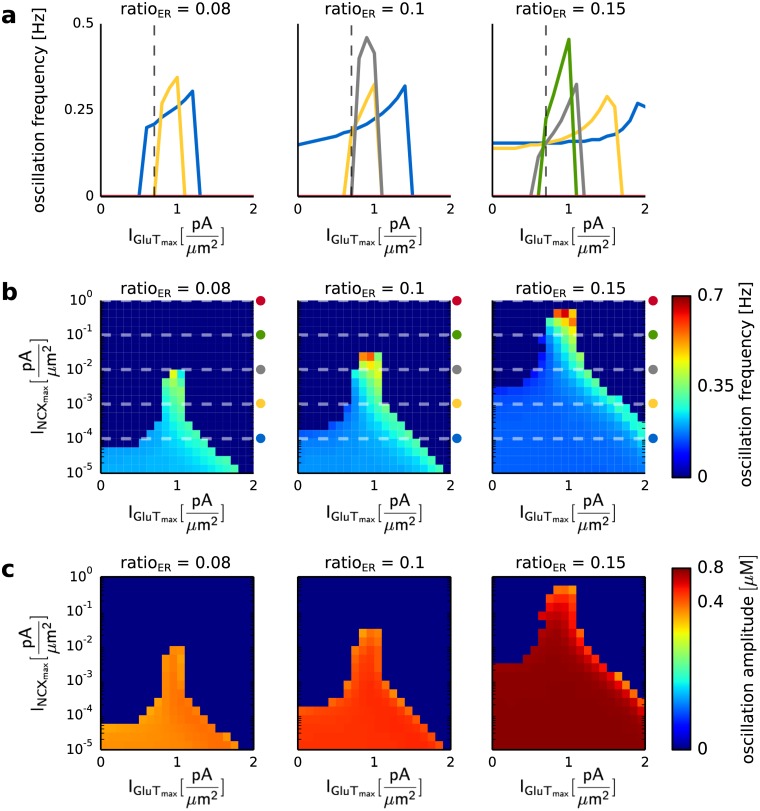

Second, we analyzed the influence of the maximal pump current of the glutamate transporter (IGluTmax) on the Ca2+ signal (see Fig 7). The impact of IGluTmax on the Ca2+ signal mainly depended on the maximal pump current of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (INCXmax) and the volume fraction of the internal Ca2+ store (ratioER). In astrocytic compartments close to the soma (ratioER≥0.1) an increase of IGluTmax increased the Ca2+ oscillation frequency until it reached a maximal value and decreased again (see Fig 7a and 7b). An increase of INCXmax shifted the maximal value of the oscillation frequency to lower values of IGluTmax (see Fig 7a). The increase of IGluTmax caused a higher increase of the intracellular Na+ concentration. The higher Na+ accumulation activated the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in the reverse mode and prevented an outflux of Ca2+ into the extracellular space. The elevated Ca2+ transport into the cell preserved the Ca2+ oscillations for high values of INCXmax and resulted in an increase of the oscillation frequency. The amplitude of the Ca2+ oscillations was mainly affected by the volume fraction of internal Ca2+ stores and increased with an increase of ratioER (see Fig 7c). The increase of the volume of both the internal Ca2+ store and the intracellular space with ratioER caused an enhanced Ca2+ release from the internal Ca2+ store.

Fig 7. Ca2+ oscillation frequency and amplitude for different values of the volume ratio between the internal Ca2+ store and the intracellular space (ratioER), as well as the maximal pump currents of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (INCXmax) and the glutamate transporter (IGluTmax).

The astrocytic compartment was stimulated for 200 seconds with a Poisson spike train of 100 Hz. a Ca2+ oscillation frequency for three different values of ratioER (0.08, 0.1 and 0.15), as a function of IGluTmax and INCXmax. The colored lines correspond to INCXmax equal to 0.0001 (blue), 0.001 (yellow), 0.01 (gray), 0.1 (green) and 1 (red). The dashed line corresponds to IGluTmax equal to 0.68. b Ca2+ oscillation frequencies for three different values of ratioER (0.08 0.1 and 0.15), as a function of IGluTmax and INCXmax. The colored symbols denote the values of INCXmax shown in a. c Ca2+ oscillation amplitudes for four different values of ratioER (0.05, 0.06, 0.1 and 0.15), and as a function of IGluTmax and INCXmax.

The interplay of the mGluR- and GluT-dependent pathways showed the experimentally observed Ca2+ fluctuations in astrocytic compartments with a low volume fraction of an internal Ca2+ store (ratioER) for a high pumping activity of the NCX (INCXmax > 0 ). However, a high maximal pump current of the NCX (INCXmax > 0.01 ) evoked a suppression of the Ca2+ oscillations in regions with a high ratioER. Thus, in comparison with experimental data the simulation data suggested a low maximal pump current of the NCX for regions with a high ratioER and a high maximal pump current of the NCX in regions with a small ratioER. Moreover, an increase of IGluTmax allowed Ca2+ oscillations for high values of INCXmax (INCXmax ≥ 1 ). Thus, the distribution of GluTs and NCXs determines Ca2+ signal along the astrocytic process. The reason for the suppression of the Ca2+ oscillations for high ratioER was investigated in a later results section.

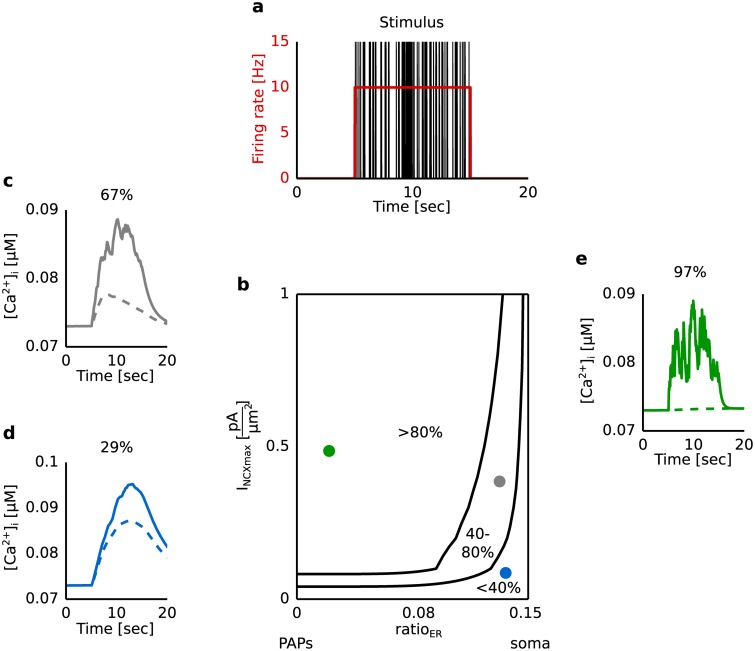

Impact of the GluT activity on the Ca2+ response under synaptic stimulation

Experiments have shown that a block of the glutamate transporter (GluT) leads to a clear attenuation of the Ca2+ signal [8]. For that reason we examined the impact of the GluT-driven Ca2+ signal on the overall Ca2+ response to synaptic stimulation. Fig 8 shows the dynamics of the Ca2+ signal as a function of the volume ratio between the internal Ca2+ store and the intracellular space (ratioER) with (’control condition’) and without (’block’) a contribution of the GluT.

Fig 8. Dynamics of the Ca2+ concentration in the intracellular compartment under synaptic stimulation for a blocked glutamate transporter (GluT) in comparison to the control condition.

a The astrocytic compartment was stimulated for 10 seconds with a Poisson spike train of 10 Hz. The corresponding glutamate concentration in the extracellular compartment as a function of time was calculated using the Tsodyks and Markram model. b Reduction of the Ca2+ response under block of the GluT as a function of the maximal pump current of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (INCXmax) and the volume ratio (ratioER) between the internal Ca2+ store and the intracellular compartment. The reduction was quantified by the difference of the average Ca2+ concentration under control condition and block normalized by the difference between the Ca2+ concentration in the control condition and the Ca2+ concentration without stimulation. Solid lines separate the parameter space concerning the reduction: larger than 80%, between 40% and 80% and under 40%. c-e Ca2+ response as a function of time for different values of INCXmax and ratioER correspond to a reduction of the Ca2+ signal of 29%, 67% and 97%. Solid and dashed lines correspond to control condition and block. The block was simulated by setting IGluTmax equal to 0 .

We observed a high impact of the GluT-driven Ca2+ signal for a high pumping activity of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (INCXmax > 0.1 ) and a small volume ratio between the internal Ca2+ store and the intracellular space (ratioER<0.1) (see Fig 8b and 8e). With a decrease of INCXmax and an increase of ratioER the impact of the GluT-driven Ca2+ signal decreased (see Fig 8b, 8c and 8d). In astrocytic compartments with a low volume fraction of the internal Ca2+ store the Ca2+ signal mainly arose by the Ca2+ transported through the membrane (see Fig 4). A block of the glutamate transporter prevented a Na+ accumulation in the intracellular space (see S1 Fig). The Na+/Ca2+ exchanger remained in the forward mode and transported Ca2+ out of the astrocyte. Thus, during a block of the glutamate transporter no Ca2+ was transported into the astrocyte via the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger and a clear attenuation of the Ca2+ signal was observed in regions with a small ratioER. With an increase of the volume fraction of the internal Ca2+ store more Ca2+ was released from the internal Ca2+ store and led to a lower impact of the glutamate transporter on the overall Ca2+ signal. The extracellular glutamate concentration and the Ca2+ entry through the membrane affected the IP3 production as well as the IP3- and Ca2+-dependent Ca2+ release from internal Ca2+ stores. An increase of ratioER was accompanied with an increase of the IP3- and Ca2+-dependent Ca2+ release from internal Ca2+ stores and thus with an increase of the impact of the mGluR-dependent mechanism. For that reason, Ca2+ signals mainly evoked by the GluT-dependent mechanism were observed in regions with a small ratioER.

Interaction of the mGluR-dependent and GluT-dependent pathway

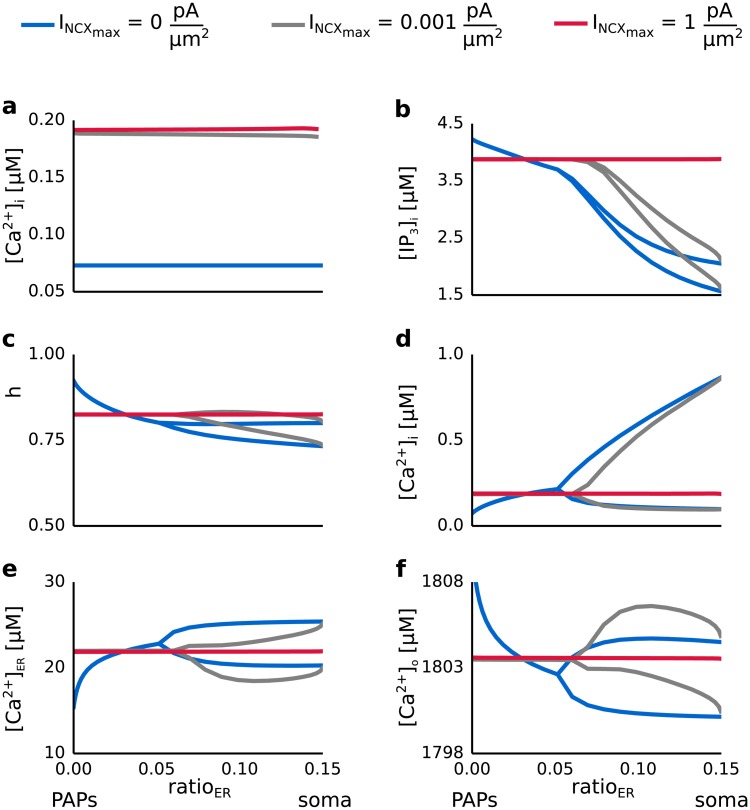

In order to study the mechanisms underlying the interaction of the mGluR- and GluT-dependent pathways we analyzed the Ca2+ concentration in the three spaces as well as the concentration of IP3 in the intracellular space and the fraction h of open IP3 channels for different values of the maximal pump current of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (INCXmax) and the volume ratio of internal Ca2+ stores (ratioER). Fig 9 summarizes the results. Oscillations of the Ca2+ concentration in the intracellular compartment (see Fig 9b) were reflected in all of the other dynamical variables (see Fig 9c–9f). When the GluT-dependent pathway was studied in isolation and Ca2+ release from internal Ca2+ stores was neglected (see Fig 9a) a finite current through the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger led to an increase of [Ca2+]i when compared with the concentration without external stimulation. The stationary value of [Ca2+]i was independent of the maximal pump currents.

Fig 9. Ca2+ concentrations in the intracellular space, the internal Ca2+ store and the extracellular space, the IP3 concentration in the intracellular space and the ratio h of active IP3 receptor channels as a function of the maximal pump current of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (INCXmax) and the volume ratio between the internal Ca2+ store and the intracellular space (ratioER).

The astrocytic compartment was stimulated for 200 seconds with a Poisson spike train of 100 Hz. The corresponding glutamate concentration in the extracellular compartment as a function of time was calculated using the Tsodyks and Markram model. Blue, gray and red lines denote the dynamics of [IP3]i, h [Ca2+]i, [Ca2+]ER, [Ca2+]o for values of INCXmax equal to 0 , 0.001 and 1 . a Analysis of the GluT-dependent pathway in isolation. [Ca2+]i is shown as a function of ratioER and for different values of INCXmax. b-f Analysis of both the mGluR- and the GluT-dependent pathway. [IP3]i, h, [Ca2+]i, [Ca2+]ER and [Ca2+]o are shown as a function of ratioER and for different values of INCXmax.

When both the GluT- and mGluR-dependent pathway were considered (see Fig 9b–9f) a high INCXmax (INCXmax > 0.001) caused an increase of the concentration of IP3 and the fraction h of open IP3 receptor channels. This caused Ca2+ flux out of the internal Ca2+ store leading to a decrease of [Ca2+]ER compared to the resting concentration. The concentration of Ca2+ in the intracellular space, however, increased by 0.1 μM while [Ca2+]o increased by 3 μM compared to its resting concentration. For high values of the maximal pump current of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger the Ca2+ transport into the endoplasmatic reticulum mediated by the SERCA pump was overcompensated by the highly strong outflux of Ca2+ via the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (see S??). Thus, Ca2+ accumulated in the extracellular space, which prevented the generation of Ca2+ oscillations.

Discussion

Our computational study addresses the generation of Ca2+ signals in different astrocytic compartments along the astrocytic process. We considered two different pathways for the generation of Ca2+ signals: the metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR)- and glutamate transporter (GluT)-dependent pathway. We analyzed both pathways in consideration of the volume ratio between the internal Ca2+ store and the intracellular space. The volume ratio between the internal Ca2+ store and the intracellular space changes from the soma towards the synapse. Whereas astrocytic compartments at the soma have a high volume ratio between the internal Ca2+ store and the intracellular space, in astrocytic compartments close to the synapse there is a low volume ratio. There are five main findings of the study.

First, while considering the mGluR-dependent pathway in isolation Ca2+ oscillations have only been observed in astrocytic compartments with a high volume ratio between the internal Ca2+ store and the intracellular space. Second, a high maximal pump current of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger suppressed Ca2+ oscillations in regions with a high volume ratio between the internal Ca2+ store and the intracellular space. Third, the suppression of Ca2+ oscillations for a high maximal pump current of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in astrocytic compartments with a high volume ratio between the internal Ca2+ store and the intracellular space was due to an overcompensation of the Ca2+ influx from the internal Ca2+ store by the outflux of Ca2+ into the extracellular space via the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger. Fourth, a high impact of the GluT-dependent mechanism on the generation of Ca2+ signals was observed for a high maximal pump current of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in regions with a low volume ratio between the internal Ca2+ store and the intracellular space. Fifth, the GluT-dependent mechanism accounted for Ca2+ fluctuations in astrocytic compartments which were devoid of internal Ca2+ stores.

In their study Srinivasan and colleagues also addressed the question which mechanism could account for Ca2+ fluctuations in astrocytic compartments close to the synapse. They discovered that a significant proportion of Ca2+ signals in astrocytic compartments close to the synapse is because of transmembrane Ca2+ fluxes. In our model we also considered Ca2+ transport from the extracellular space into the intracellular space of the astrocyte through the GluT-dependent pathway. We found that the GluT-dependent Ca2+ transport into the astrocyte could account for mGluR-independent Ca2+ fluctuations in astrocytic compartments with a low volume ratio between the internal Ca2+ store and the intracellular space.

However, while analyzing both the mGluR- and GluT-dependent pathway a high maximal pump current of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger suppressed Ca2+ oscillations in astrocytic compartments with a high volume ratio between the internal Ca2+ store and the intracellular space. Moreover, the contribution of the GluT on the generation of Ca2+ signals was highest for a large maximal pump current of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in astrocytic compartments with a low volume ratio between the internal Ca2+ store and the intracellular space. These simulation results suggested a change of the pumping activity of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger along the astrocytic process. A low maximal pump current in astrocytic compartments at the soma prevented the suppression of Ca2+ oscillations. A high maximal pump current in astrocytic compartments close to the synapse allowed a high contribution of the GluT-dependent pathway on the generation of Ca2+ signals. Based on the strength of the maximal pump current the channel density of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger can be concluded. The higher the maximal pump current is, the more ions are transported through the membrane. The same holds true for the channel density. The higher the channel density is, the more ions are transported through that channel. Experimental results confirm a concentration and colocalization of Na+/Ca2+ exchangers, Na+/K+-ATPases and GluTs in perisynaptic astrocytic processes [31, 32].

Ca2+ transport through the plasma membrane (e.g. via the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger) [23, 33, 34] as well as by the Ca2+ diffusion within a single astrocyte [35, 36] or between astrocytes [37] changes the intracellular Ca2+ concentration. Fluctuations of the intracellular Ca2+ concentration affect both the Ca2+ entry mediated by the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger when operating in the reverse mode [23] and the Ca2+ release probability of the endoplasmatic reticulum [38]. The current model neglects Ca2+ diffusion within the astrocyte and describes the Ca2+ dynamics in a single compartment. Thus, an extension of the current point-model to a multi-compartment model will most probably reveal deviating results for parameters such as the maximal pump current of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger. Moreover, the volume determines the number of Ca2+ ions within an astrocytic compartment and consequently the concentration change. Thus, diffusion of Ca2+ in astrocytic compartments with a low volume, such as in the perisynaptic astrocytic processes, leads to a bigger concentration change as in compartments with a larger volume.

The above named findings allow to make a prediction about the functional role of astrocytes in neural networks. Astrocytic compartments, which have a high volume ratio of internal Ca2+ stores and are capable of IP3-dependent Ca2+ release, are not located directly at the synapse. Moreover, the high surface volume ratio of the perisynaptic astrocytic processes and a slow diffusion exchange in such thin processes favors a localized Na+ accumulation and promotes Ca2+ intrusion mediated by the NCX [39]. This may indicate that store-dependent Ca2+ signals in astrocytes act as integrators of local network activity, but not as detectors of individual synaptic events [12]. GluT-dependent Ca2+ signals in perisynaptic astrocytic processes are evoked in response to individual synaptic events. Depending on the synaptic activity Ca2+ is transported into the astrocyte by the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger and diffuses within the astrocyte network. Once this Ca2+ wave reaches astrocytic compartments which are capable of store dependent Ca2+ signals an integration of the local network activity, the intracellular Ca2+ signal and the glutamate-dependent IP3 production, takes place.

Our model describes the generation of Ca2+ signals in a single astrocyte compartment with respect to its morphology. However, it is of special interest how activity of single synapses and neural networks is integrated by astrocytes. It was proposed that perisynaptic astrocytic processes serve as detectors for single synaptic events, whereas astrocytic processes which contain Ca2+ stores act as integrators of neural network activity [12]. A multi-compartment model would contribute to the analysis of the integration of neural activity performed by astrocytes. This would allow the study of Ca2+ waves within a single astrocyte and in astrocyte networks as well as their impact on the surrounding extracellular space.

Supporting information

Dynamics of the Na+ concentration in the intracellular compartment under synaptic stimulation for a blocked glutamate transporter in comparison to the control condition. The astrocytic compartment was stimulated for 10 seconds with a Poisson spike train of 10 Hz (see Fig 8). a Time course of the glutamate concentration in the extracellular compartment calculated with the Tsodyks and Markram model. b-d Time course of the intracellular Na+ concentration for three different parameter combinations of the volume ratio between the internal Ca2+ store and the intracellular space (ratioER) and the maximal pump current of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (INCXmax). The intracellular Na+ concentration is shown for the same parameter combinations of INCXmax and ratioER as Ca2+ in Fig 8c, 8d and 8e (b: ratioER = 0.14 and INCXmax = 0.1 , c: ratioER = 0.12 and INCXmax = 0.4 , d: ratioER = 0.03 and INCXmax = 0.5 ). Solid and dashed lines corresponds to the control condition and block, respectively. The intracellular Na+ concentration was not affected by different values of ratioER and INCXmax. During a block of the glutamate transporter (dashed lines) the Na+ concentration remained on its resting concentration.

(EPS)

Ca2+ oscillation frequency as a function of the maximal pump current of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (INCXmax) and the stimulation frequency, as well as for different values of the volume fraction of the internal Ca2+ store (ratioER). The astrocytic compartment was stimulated for 200 seconds with a Poisson spike train of 5-100 Hz. The corresponding glutamate concentration was calculated using the Tsodyks Markram model. The parameter space for which Ca2+ oscillations were observed increased with an increase of ratioER. An onset of the Ca2+ oscillations was observed for stimulation frequencies greater than 5 Hz. The oscillation frequency, however, decreased for an increase of the volume fraction of internal Ca2+ stores. Thus, a larger volume of the internal Ca2+ store and the intracellular space favored the generation of Ca2+ oscillations and a longer Ca2+ oscillation period.

(EPS)

Current strength of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (INCX) as a function of the maximal pump current of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (INCXmax) and the stimulation frequency, as well as for different values of the volume fraction of the internal Ca2+ store (ratioER). The astrocytic compartment was stimulated for 200 seconds with a Poisson spike train of 5-100 Hz. The corresponding glutamate concentration was calculated using the Tsodyks Markram model. The white area corresponds to parameter combinations which evoked Ca2+ oscillations. An increase of the volume fraction of the internal Ca2+ store led to a decrease of INCX, which corresponded to a larger outflux of Ca2+ out of the astrocyte.

(EPS)

Time course of the intracellular Ca2+ concentration, the current strengths of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger and the IP3-receptor current for different values of the maximal pump current of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (INCXmax) and the volume fraction of the internal Ca2+ store (ratioER). a The astrocytic compartment was stimulated with a single action potential. The gray line corresponds to the time point of the action potential. The corresponding glutamate concentration was calculated using the Tsodyks Markram model. b-d Time courses of the intracellular Ca2+ concentration [Ca2+]i, the current strengths of the Na+/Ca2+ (INCX) and the IP3-receptor current (IIP3R) for different values of INCXmax and ratioER. After the application of a single action potential the Ca2+ concentration returned fastest to the resting concentration when the astrocytic compartment was devoid of the internal Ca2+ store (ratioER = 0) (see b). This process was slowed down by the Ca2+ transport mechanisms at the internal Ca2+ store (ratioER = 0.06 and 0.15). In general, the current strength of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger reached the steady state much faster than the current strength of the IP3-receptor current (see c, d). With an increase of the volume fraction of the internal Ca2+ store also the impact of the Ca2+ transport mechanisms at the endoplasmatic reticulum on the intracellular Ca2+ concentration increased. Thus, for larger values of ratioER it took longer for Ca2+ to return to its resting concentration.

(EPS)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung: 01GQ 1009 (KM) https://www.bmbf.de/ and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Graduiertenkolleg 1589 http://www.dfg.de/. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Perea G, Navarrete M, Araque A. Tripartite synapses: astrocytes process and control synaptic information; 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Helen C, Kastritsis C, Salm AK, McCarthy K. Stimulation of the P2Y Purinergic Receptor on Type 1 Astroglia Results in Inositol Phosphate Formation and Calcium Mobilization. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1992;58(4):1277–1284. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb11339.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McCarthy KD, Salm AK. Pharmacologically-distinct subsets of astroglia can be identified by their calcium response to neuroligands. Neuroscience. 1991;41(2-3):325–333. 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90330-Q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pasti L, Volterra A, Pozzan T, Carmignoto G. Intracellular calcium oscillations in astrocytes: a highly plastic, bidirectional form of communication between neurons and astrocytes in situ. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1997;17(20):7817–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Araque A, Martín ED, Perea G, Arellano JI, Buño W. Synaptically released acetylcholine evokes Ca2+ elevations in astrocytes in hippocampal slices. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2002;22(7):2443–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Agulhon C, Petravicz J, McMullen AB, Sweger EJ, Minton SK, Taves SR, et al. What is the role of astrocyte calcium in neurophysiology? Neuron. 2008;59(6):932–946. 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wallach G, Lallouette J, Herzog N, De Pittà M, Jacob EB, Berry H, et al. Glutamate Mediated Astrocytic Filtering of Neuronal Activity. PLoS Computational Biology. 2014;10(12). 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schummers J, Yu H, Sur M. Tuned responses of astrocytes and their influence on hemodynamic signals in the visual cortex. Science (New York, NY). 2008;320(5883):1638–43. 10.1126/science.1156120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rojas H, Colina C, Ramos M, Benaim G, Jaffe EH, Caputo C, et al. Na+ entry via glutamate transporter activates the reverse Na+/Ca2+ exchange and triggers Cai 2+ -induced Ca2+ release in rat cerebellar Type-1 astrocytes. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2007;100(5):1188–1202. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04303.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rose EM, Koo JCP, Antflick JE, Ahmed SM, Angers S, Hampson DR. Glutamate Transporter Coupling to Na,K-ATPase. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29(25):8143–8155. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1081-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Srinivasan R, Huang BS, Venugopal S, Johnston AD, Chai H, Zeng H, et al. Ca(2+) signaling in astrocytes from Ip3r2(-/-) mice in brain slices and during startle responses in vivo. Nature neuroscience. 2015;18(5):708–17. 10.1038/nn.4001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Patrushev I, Gavrilov N, Turlapov V, Semyanov A. Subcellular location of astrocytic calcium stores favors extrasynaptic neuron-astrocyte communication. Cell Calcium. 2013;54(5):343–349. 10.1016/j.ceca.2013.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. De Pittà M, Goldberg M, Volman V, Berry H, Ben-Jacob E. Glutamate regulation of calcium and IP3 oscillating and pulsating dynamics in astrocytes. Journal of Biological Physics. 2009;35(4):383–411. 10.1007/s10867-009-9155-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Li YX, Rinzel J. Equations for InsP3 Receptor-mediated [Ca2+]i Oscillations Derived from a Detailed Kinetic Model: A Hodgkin-Huxley Like Formalism. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 1994;166(4):461–473. 10.1006/jtbi.1994.1041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tzingounis AV, Wadiche JI. Glutamate transporters: confining runaway excitation by shaping synaptic transmission. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8(12):935–947. 10.1038/nrn2274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kanner BI, Bendahan A. Binding order of substrates to the sodium and potassium ion coupled L-glutamic acid transporter from rat brain. Biochemistry. 1982;21(24):6327–6330. 10.1021/bi00267a044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wadiche JI, Arriza JL, Amara SG, Kavanaugh MP. Kinetics of a human glutamate transporter. Neuron. 1995;14(5):1019–1027. 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90340-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Luo C. A dynamic model of the cardiac ventricular action potential. I. Simulations of ionic currents and concentration changes. Circulation Research. 1994;74(6). 10.1161/01.RES.74.6.1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Østby I, Øyehaug L, Einevoll GT, Nagelhus EA, Plahte E, Zeuthen T, et al. Astrocytic mechanisms explaining neural-activity-induced shrinkage of extraneuronal space. PLoS Computational Biology. 2009;5(1):e1000272 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Blaustein MP, Santiago EM. EFFECTS OF INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL CATIONS AND OF ATP ON SODIUM-CALCIUM AND CALCIUM-CALCIUM EXCHANGE IN SQUID AXONS with the technical assistance of. Biophys J. 1977;20(1):79–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tsodyks MV, Markram H. The neural code between neocortical pyramidal neurons depends on neurotransmitter release probability. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1997;94(2):719–723. 10.1073/pnas.94.2.719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fuhrmann G, Markram H, Tsodyks M. Spike frequency adaptation and neocortical rhythms. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88(2):761–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Reyes RC, Verkhratsky A, Parpura V. Plasmalemmal Na+/Ca2+ exchanger modulates Ca2+-dependent exocytotic release of glutamate from rat cortical astrocytes. ASN neuro. 2012;4(1):33–45. 10.1042/AN20110059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McKhann GM, D’Ambrosio R, Janigro D. Heterogeneity of astrocyte resting membrane potentials and intercellular coupling revealed by whole-cell and gramicidin-perforated patch recordings from cultured neocortical and hippocampal slice astrocytes. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1997;17(18):6850–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Falcke M, Hudson JL, Camacho P, Lechleiter JD. Impact of Mitochondrial Ca2+ Cycling on Pattern Formation and Stability. Biophysical Journal. 1999;77(1):37–44. 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)76870-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ullah G, Jung P, Cornell-Bell AH. Anti-phase calcium oscillations in astrocytes via inositol (1, 4, 5)-trisphosphate regeneration. Cell Calcium. 2006;39(3):197–208. 10.1016/j.ceca.2005.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Horak FB, Nashner LM, Diener HC. Characterization of glutamate uptake into and release from astrocytes and neurons cultured from different brain regions. Experimental Brain Research. 1990;47(2):167–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Goodman D, Brette R. Brian: a simulator for spiking neural networks in python. Frontiers in neuroinformatics. 2008;2(November):5 10.3389/neuro.11.005.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kirischuk S, Kettenmann H, Verkhratsky A. Membrane currents and cytoplasmic sodium transients generated by glutamate transport in Bergmann glial cells. Pflügers Archiv—European Journal of Physiology. 2007;454(2):245–252. 10.1007/s00424-007-0207-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rose CR, Karus C. Two sides of the same coin: Sodium homeostasis and signaling in astrocytes under physiological and pathophysiological conditions. Glia. 2013;61(8):1191–1205. 10.1002/glia.22492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Minelli A, Castaldo P, Gobbi P, Salucci S, Magi S, Amoroso S. Cellular and subcellular localization of Na+-Ca2+ exchanger protein isoforms, NCX1, NCX2, and NCX3 in cerebral cortex and hippocampus of adult rat. Cell Calcium. 2007;41(3):221–234. 10.1016/j.ceca.2006.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Danbolt NC. Glutamate uptake; 2001. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11369436. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33. Goldman WF, Yarowsky PJ, Juhaszova M, Krueger BK BM. Sodium/calcium exchange in rat cortical astrocytes. J Neurosci. 1994;14(14):5834–5843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kirischuk S, Ketfenmann H. Na+/ Ca2+exchanger modulates Ca2+ signaling in Bergmann glial cells in situ. Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 1997;11(7):566–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Grosche J, Matyash V, Möller T, Verkhratsky A, Reichenbach A, Kettenmann H. Microdomains for neuron-glia interaction: parallel fiber signaling to Bergmann glial cells. Nature neuroscience. 1999;2(2):139–43. 10.1038/5692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kirischuk S, Moller T, Voitenko N, Kettenmann H, Verkhratsky A. ATP-induced cytoplasmic calcium mobilization in Bergmann glial cells. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cornell-Bell AH, Finkbeiner SM, Cooper MS, Smith SJ. Glutamate induces calcium waves in cultured astrocytes: long- range glial signalling. Science. 1990;247(4941):470–473. 10.1126/science.1967852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bezprozvanny I, Watras J, Ehrlich BE. Bell-shaped calcium-response curves of Ins(1,4,5)P3- and calcium-gated channels from endoplasmic reticulum of cerebellum.; 1991. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1648178 10.1038/351751a0. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39. Rusakov DA, Zheng K, Henneberger C. Astrocytes as Regulators of Synaptic Function A Quest for the Ca2+ Master Key. The Neuroscientist. 2011;17(5):513–523. 10.1177/1073858410387304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Dynamics of the Na+ concentration in the intracellular compartment under synaptic stimulation for a blocked glutamate transporter in comparison to the control condition. The astrocytic compartment was stimulated for 10 seconds with a Poisson spike train of 10 Hz (see Fig 8). a Time course of the glutamate concentration in the extracellular compartment calculated with the Tsodyks and Markram model. b-d Time course of the intracellular Na+ concentration for three different parameter combinations of the volume ratio between the internal Ca2+ store and the intracellular space (ratioER) and the maximal pump current of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (INCXmax). The intracellular Na+ concentration is shown for the same parameter combinations of INCXmax and ratioER as Ca2+ in Fig 8c, 8d and 8e (b: ratioER = 0.14 and INCXmax = 0.1 , c: ratioER = 0.12 and INCXmax = 0.4 , d: ratioER = 0.03 and INCXmax = 0.5 ). Solid and dashed lines corresponds to the control condition and block, respectively. The intracellular Na+ concentration was not affected by different values of ratioER and INCXmax. During a block of the glutamate transporter (dashed lines) the Na+ concentration remained on its resting concentration.

(EPS)

Ca2+ oscillation frequency as a function of the maximal pump current of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (INCXmax) and the stimulation frequency, as well as for different values of the volume fraction of the internal Ca2+ store (ratioER). The astrocytic compartment was stimulated for 200 seconds with a Poisson spike train of 5-100 Hz. The corresponding glutamate concentration was calculated using the Tsodyks Markram model. The parameter space for which Ca2+ oscillations were observed increased with an increase of ratioER. An onset of the Ca2+ oscillations was observed for stimulation frequencies greater than 5 Hz. The oscillation frequency, however, decreased for an increase of the volume fraction of internal Ca2+ stores. Thus, a larger volume of the internal Ca2+ store and the intracellular space favored the generation of Ca2+ oscillations and a longer Ca2+ oscillation period.

(EPS)

Current strength of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (INCX) as a function of the maximal pump current of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (INCXmax) and the stimulation frequency, as well as for different values of the volume fraction of the internal Ca2+ store (ratioER). The astrocytic compartment was stimulated for 200 seconds with a Poisson spike train of 5-100 Hz. The corresponding glutamate concentration was calculated using the Tsodyks Markram model. The white area corresponds to parameter combinations which evoked Ca2+ oscillations. An increase of the volume fraction of the internal Ca2+ store led to a decrease of INCX, which corresponded to a larger outflux of Ca2+ out of the astrocyte.

(EPS)

Time course of the intracellular Ca2+ concentration, the current strengths of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger and the IP3-receptor current for different values of the maximal pump current of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (INCXmax) and the volume fraction of the internal Ca2+ store (ratioER). a The astrocytic compartment was stimulated with a single action potential. The gray line corresponds to the time point of the action potential. The corresponding glutamate concentration was calculated using the Tsodyks Markram model. b-d Time courses of the intracellular Ca2+ concentration [Ca2+]i, the current strengths of the Na+/Ca2+ (INCX) and the IP3-receptor current (IIP3R) for different values of INCXmax and ratioER. After the application of a single action potential the Ca2+ concentration returned fastest to the resting concentration when the astrocytic compartment was devoid of the internal Ca2+ store (ratioER = 0) (see b). This process was slowed down by the Ca2+ transport mechanisms at the internal Ca2+ store (ratioER = 0.06 and 0.15). In general, the current strength of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger reached the steady state much faster than the current strength of the IP3-receptor current (see c, d). With an increase of the volume fraction of the internal Ca2+ store also the impact of the Ca2+ transport mechanisms at the endoplasmatic reticulum on the intracellular Ca2+ concentration increased. Thus, for larger values of ratioER it took longer for Ca2+ to return to its resting concentration.

(EPS)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.