Abstract

Few studies have examined cancer-related risk factors in relation to SES across the lifecourse in low to middle income countries. This analysis focuses on adult women in India, China, Mexico, Russia and South Africa, and examines the association between individual, parental and lifecourse SES with smoking, alcohol, BMI, nutrition and physical activity. Data on 22,283 women aged 18 years and older were obtained from the 2007 WHO Study on Global Aging and Adult Health (SAGE). Overall, 34% of women had no formal education, 73% had mothers with no formal education and 73% of women had low lifecourse SES. Low SES women were almost 4 times more likely to exceed alcohol use guidelines (OR: 3.86, 95% CI: 1.23–12.10), and 68% more likely to smoke (OR: 1.68, 95% CI: 1.01–2.80) compared with higher SES. Women with low SES mothers and fathers were more likely to have poor nutrition (Mothers OR: 1.59, 95% CI: 1.17–2.16; Fathers OR: 1.33, 95% CI: 1.11–1.59) and more likely to smoke (Mothers OR: 1.46, 95% CI: 1.15–1.87; Fathers OR: 2.17, 95% CI: 1.80–2.63) compared with those with high SES parents. Women with stable low lifecourse SES were more likely to smoke (OR: 2.55, 95% CI: 1.47–4.43), while those with declining lifecourse SES were more likely to exceed alcohol use guidelines (OR: 3.63, 95% CI: 1.07–12.34). Cancer-related risk factors varied significantly by lifecourse SES, suggesting that cancer prevention strategies will need to be tailored to specific subgroups in order to be most effective.

Keywords: Cancer risk factors, Diet, Middle Income Countries, socio-economic status, lifecourse

INTRODUCTION

Compelling evidence suggests that socio-economic status (SES) influences adult health outcomes.[1–4] Multiple studies have reported significant associations between SES and cancer incidence and mortality [5–11], although the associations vary by cancer type. For instance, incidence of lung cancer has been observed to be higher among low SES individuals, while incidence of breast cancer is observed to be higher among higher SES women.[12–16] A proposed mechanism underlying this association includes differences in the prevalence and distribution of cancer-related risk factors, including smoking, alcohol, diet or exogenous hormone use.[17] Most studies of SES and cancer risk factors have included data from developed countries such as US and Europe, where results show a higher prevalence of several cancer risk factors, such as smoking, alcohol use, poor nutrition and low physical activity, among lower SES individuals.[18, 19] However, recent studies in developing countries have shown that the association may be reverse- with a higher prevalence of cancer related risk factors among higher SES individuals.[20, 21]

The influence of SES on cancer risk has also been shown to be important across the lifecourse; SES in childhood exerts a significant influence on cancer risk in adulthood even after adjusting for adult SES, and social mobility, i.e. change in SES from childhood to adulthood influences adult health behavior[22]. In addition to the health-behavior mediated mechanism linking lifecourse SES with adult cancer risk, lifecourse SES may also operate through other biological or environmental exposures during childhood, especially exposures that are important during a specific biological time window e.g. studies of breast cancer have found that early life exposures during puberty are important determinants of adult breast cancer risk.[23] Other potential mechanisms important for cancer risk include a chronic lack of access to healthcare that minimizes the opportunity for appropriate medical recommendation about cancer risk[24], the higher burden of psychosocial stressors, as well as exposures to environmental pollutants, including lead and infectious agents such as H. Pyori.[19, 22, 25–27] Importantly, lifecourse SES may be a more important social determinant of adult cancer risk if the influence of these factors, particularly modifiable health behaviors, accumulate over time from childhood to adulthood. Again, studies on lifecourse SES and cancer risk factors have also mostly focused on developed countries.[28–30]

Given recent estimates from the International Agency for Research on Cancer projecting that up to 70% of new cancer cases will occur in developing countries in the next two decades, research studies in this area are urgently warranted. Improved understanding of the influence of SES over the lifecourse on modifiable cancer risk factors may help identify vulnerable population sub-groups for targeted cancer prevention strategies. Here, we examined the distribution of individual, parental and lifecourse SES among women in low to middle income in the Study of Global Ageing and Adult Health (SAGE), and examined lifecourse SES gradients in the major cancer-related risk factors (smoking, alcohol, body weight, nutrition and physical activity) and country-level differences in the SES-risk factor association.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Data Source and Study Population

Data for this analysis was obtained from the WHO Study on Global Ageing and Adult Health (SAGE) conducted in China, Ghana, India, Mexico, Russia and South Africa in 2007. The SAGE study was designed as a cross-sectional, longitudinal study of adults ages 18 and older from nationally representative samples in the six countries, and aimed to evaluate disease risk factors, access to healthcare, health status and well-being. Five middle-income countries- China, India, Mexico, Russia and South Africa- were included in the present analysis to represent one country each per continent, capture countries that have experienced major economic transitions in the past few decades, and have a common threat of rising non-communicable diseases burden. In particular, this analysis focused on women ages 18 years and older due to the rising incidence of breast cancer in these countries, a cancer type shown to be influenced by these modifiable risk factors, and the potential for SES differences to more directly impact risk factors such as diet, physical activity and alcohol use among women. More information on the SAGE study can be obtained through the WHO SAGE website: (http://www.who.int/healthinfo/sage/cohorts/en/).

Cancer-Related Risk Factors

This study focused on cancer-related risk factors defined using the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research (WCRF/AICR) guidelines for cancer prevention[31]. The risk factors were defined as: 1) alcohol consumption (>7 drinks per week), smoking (current/former cigarette smoker), physical activity (recreational or non-recreational physical activity minutes < 240 minutes/week), nutrition (fruit and vegetable intake < 5 servings/day), and body mass index (overweight BMI> 25 kg/m2). Self-reported information on each risk factor was obtained by WHO SAGE trained field staff during in-person interviews, and physical measurement of height, weight, pulse rate and three readings of blood pressure were obtained. Questionnaires translated to the local dialect were administered in instances were the individuals did not speak English. We present descriptive statistics and regression models for the adverse risk factors as defined above in tables, and country level variation in adherence to the risk factors as defined by WCRF/AICR i.e. alcohol use <7 drinks/week, >=240 minutes of physical activity per week, 5 daily servings of fruits/vegetables, and BMI <25, in charts.

Individual and Parental SES

Individual and parental SES was defined based on educational attainment (categorized into: no formal education, primary school only, high school graduate, and college or higher degree) and employment status (categorized into: unemployed, public sector employment, private sector employment, self/informal employment). Individual and parental SES variables were defined based on education and employment status.

Lifecourse SES

Social mobility or change in SES from parent to individual based on the education and employment measures was used to define lifecourse SES. For instance, Lifecourse SES based on education was categorized into: stable low (< primary and < primary), if both parent and individual did not complete primary school education; declining (>= primary and < primary) if the parent completed primary school and the individual did not; increasing (< primary and >= primary) if the parent did not complete primary school and the individual did; and stable high (>= primary and >= primary) if both completed primary school education. Lifecourse SES based on employment was categorized as: stable low (unemployed and unemployed) if individual were unemployed during the survey and parent had never been employed; increasing (unemployed and employed) if the parent has never been employed but the individual was employed; declining (employed and unemployed) if the parent had a history of being employed but the individual was unemployed; and stable high (employed and employed) if parent had a history of employment or both were employed during the time of the survey.

Covariates

Other covariates that were included in the analysis included: age, marital status, rural/urban residence, current health status and country. Covariates selected were those that were significant in bivariate analysis and contributed to the outcome in the presence of other variables. All missing values were treated as missing and excluded from analyses.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analysis was conducted using survey-weighted statistics to determine the distribution of baseline demographics, individual and lifecourse SES variables in each country and overall, and to examine the prevalence of each cancer-related risk factor by country. Survey weighted multivariable logistic regression models were created to determine the relationship between individual and lifecourse SES in relation to each risk factor. Regression models adjusted for age, marital status, rural/urban residence, health status and country to obtain adjusted estimates for each risk factor. For all analyses, p values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS 9.4 (SAS institute Inc. NC, USA) using survey weight, strata and cluster variables provided with the SAGE dataset to account for study sample design and enabling study results to be generalizable to the included countries.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

A total 22,283 women ages 18 years and older were included in this analysis; 8,002 from China, 7,489 from India, 1,689 from Mexico, 2,427 from South Africa and 2,676 from Russia; representing approximately 50% of SAGE study participants from each country (Table 1). The majority of study participants overall were married (77%); however this ranged widely from 38% in South Africa to 89% in China. Most participants reported being in moderate (43%) or good (45%) overall health. Overall, 28% of studied women were overweight/obese, ranging from 13% in India to 65% in South Africa and 68% in Mexico. Most women consumed 4.9 servings of fruits and vegetables per day on average, however wide between-country variation exists; mean daily consumption of fruit and vegetable was 0.6 in Russia, 2.6 in India, 2.9 in Mexico, 3.4 in South Africa, and 9.5 in China. In total, women participated in an average of 947 minutes of physical activity weekly, ranging from 539 in South Africa to 1233 in Russia, recreational physical activity accounted for only 44 minutes per week, ranging form 23 minutes in Mexico to 71 minutes in China.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and cancer related risk factors, 2007 SAGE‡

| Total N=22,283 |

China N=8,002 |

India N=7,489 |

Mexico N=1,689 |

South Africa N=2,427 |

Russia N=2,676 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||||

| 18 – 24 | 1049 (10.3) | 42 (3.3) | 946 (18.7) | 9 (0.9) | 33 (12.1) | 19 (4.0) |

| 25 – 39 | 2697 (31.4) | 371 (27.7) | 1961 (36.1) | 155 (50.6) | 100 (31.9) | 110 (27.6) |

| 40 – 64 | 11451 (46.9) | 4730 (58.3) | 3357 (36.6) | 704 (38.0) | 1390 (46.8) | 1270 (46.2) |

| ≥65 | 7086 (11.3) | 2859 (10.6) | 1225 (8.6) | 821 (10.4) | 904 (9.2) | 1277 (22.2) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 22283 (50.5) | 8002 (49.1) | 7489 (50.3) | 1689 (52.0) | 2427 (52.8) | 2676 (55.0) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Never married | 1341 (7.6) | 101 (3.7) | 483 (8.3) | 186 (20.2) | 453 (34.5) | 118 (8.1) |

| Married | 14621 (77.4) | 6315 (89.5) | 5375 (77.8) | 869 (65.7) | 874 (38.4) | 1188 (53.7) |

| Div/Wid | 6179 (15.0) | 1576 (6.8) | 1630 (13.9) | 634 (14.2) | 1100 (27.1) | 1370 (38.2) |

| Overall Health | ||||||

| Good | 7152 (45.1) | 2614 (49.5) | 2664 (42.9) | 626 (49.4) | 908 (54.3) | 340 (36.0) |

| Moderate | 11075 (42.8) | 3752 (38.2) | 3749 (45.7) | 856 (40.6) | 1140 (32.9) | 1578 (50.5) |

| Poor | 4056 (12.1) | 1636 (12.3) | 1076 (11.4) | 207 (9.8) | 379 (12.2) | 758 (13.5) |

| Body Mass Index | ||||||

| Underweight | 4597 (23.6) | 850 (9.4) | 3060 (42.7) | 187 (9.2) | 198 (7.3) | 302 (10.5) |

| Normal | 9150 (48.1) | 4454 (58.7) | 3308 (44.0) | 353 (23.2) | 507 (27.9) | 528 (36.8) |

| Overweight/Obese | 8638 (28.3) | 2698 (31.8) | 1121 (13.3) | 1149 (67.6) | 1722 (64.8) | 1846 (52.7) |

| Nutrition Serving (Mean, SD) | ||||||

| Fruit | 1.5 (2.5) | 2.7 (2.4) | 0.7 (1.6) | 1.4 (1.8) | 1.5 (1.6) | 0.2 (3.6) |

| Vegetable Intake | 3.4 (3.9) | 6.8 (3.9) | 1.9 (0.9) | 1.5 (1.9) | 1.9 (1.6) | 0.4 (3.7) |

| Total Intake (fruit and vegetables) | 4.9 (6.4) | 9.5 (6.3) | 2.6 (2.5) | 2.9 (3.7) | 3.4 (3.2) | 0.6 (7.3) |

| Physical Activity, Min/week (Mean, SD) | ||||||

| Recreational | 44 (225) | 71 (252) | 33 (218) | 23 (151) | 24 (200) | 27 (215) |

| All activity | 947 (1215) | 791 (1085) | 1201 (1265) | 679 (1108) | 539 (1007) | 1233 (1430) |

| Alcohol Consumption | ||||||

| Yes | 3757 (16.5) | 854 (11.7) | 167 (1.4) | 517 (38.9) | 456 (17.6) | 1763 (76.8) |

| No | 18526 (83.5) | 7148 (88.3) | 7322 (98.6) | 1172 (61.1) | 1971 (82.4) | 913 (23.2) |

| Smoking | ||||||

| Never | 17969 (82.9) | 7444 (95.9) | 5242 (71.0) | 1273 (71.6) | 1636 (73.0) | 2374 (85.3) |

| Former | 1625 (6.5) | 284 (1.4) | 695 (11.0) | 244 (8.0) | 255 (9.3) | 147 (6.4) |

| Current | 2689 (10.6) | 274 (2.7) | 1552 (18.0) | 172 (20.4) | 536 (17.7) | 155 (8.3) |

All percentages are weighted percentages

Mean and SD (standard deviation)

Distribution of SES

Overall, 35% of women in this study had no formal education; 24.5% from China, 57.9% from India, 27.8% from Mexico, 22.8% from South Africa and 1.3% from Russia (Table 2). About 24% of all participants were unemployed at the time of the survey, 28% in China, 15% in India, 16% in Mexico, 38% in South Africa and 37% in Russia. Over 73% of participants had mothers with no formal education, ranging from 19% in Russia to 80% in China and 81% in Mexico, only 2.4% of women had mothers with a college education, and about 38% of women had mothers who were unemployed. About 58% of participants had fathers with no formal education, ranging from 16% in Russia to 71% in Mexico, and only 8.9% had fathers who were unemployed. Based on mother’s education, 6% of participants had high stable lifecourse SES, and 73% had stable low lifecourse SES; based on mother’s employment, 13% of participants had table high lifecourse SES, and 68% had stable low lifecourse SES. Based on father’s education, 7% of participants had stable high lifecourse SES, while 60% had stable low lifecourse SES; based on father’s employment, 15% had stable high lifecourse SES and 59% had stable low lifecourse SES. The highest proportion of women with stable high lifecourse SES was observed in Russia, with 57% and 56% of women based on father’s employment and mother’s employment respectively; conversely, the lowest proportion was observed in India, with 1.6% and 2.3% of women with stable high lifecourse SES based on mother’s employment and father’s employment respectively.

Table 2.

Distribution of individual, parental and lifecourse SES by Country, 2007 SAGE‡

| SES | Total | China | India | Mexico | South Africa | Russia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual SES | |||||||

| Individual Education | |||||||

| No formal education | 10341 (34.5) | 3911 (24.5) | 4402 (57.9) | 879 (27.8) | 1053 (22.8) | 96 (1.3) | |

| Primary school or less | 3311 (14.1) | 1301 (16.2) | 954 (16.0) | 356 (30.8) | 492 (15.6) | 208 (2.6) | |

| High school | 6311 (42.9) | 2493 (50.5) | 1265 (22.0) | 218 (31.0) | 473 (52.1) | 1862 (76.8) | |

| College or more | 1321 (8.4) | 297 (8.8) | 260 (4.1) | 169 (10.4) | 86 (9.4) | 509 (19.2) | |

| Individual Employment | |||||||

| Public | 1438 (14.3) | 489 (16.0) | 116 (1.5) | 41 (3.3) | 103 (14.3) | 689 (49.4) | |

| Private | 962 (6.9) | 268 (9.3) | 273 (3.5) | 70 (7.8) | 221 (11.0) | 130 (9.1) | |

| Self-employed | 11197 (54.7) | 3499 (46.8) | 5718 (80.1) | 1210 (73.0) | 665 (36.4) | 105 (4.5) | |

| Unemployed | 8686 (24.1) | 3746 (27.9) | 1382 (14.9) | 368 (15.9) | 1438 (38.3) | 1752 (37.0) | |

|

| |||||||

| Parental SES | |||||||

| Mother’s Education | |||||||

| No formal education | 17341 (73.3) | 7040 (80.0) | 6145 (87.2) | 1442 (81.2) | 1719 (58.0) | 995 (19.1) | |

| Primary school or less | 1546 (9.4) | 342 (10.6) | 382 (6.4) | 107 (10.3) | 162 (22.9) | 553 (10.3) | |

| High school | 1809 (14.9) | 325 (8.4) | 323 (5.8) | 38 (6.0) | 142 (13.5) | 981 (59.4) | |

| College or more | 289 (2.4) | 42 (0.9) | 31 (0.6) | 35 (2.5) | 43 (5.6) | 138 (11.2) | |

| Mother’s Employment | |||||||

| Public | 3272 (20.0) | 895 (17.5) | 67 (1.0) | 38 (3.9) | 87 (9.4) | 2185 (89.3) | |

| Private | 993 (3.4) | 162 (2.4) | 266 (3.3) | 72 (5.8) | 466 (18.3) | 27 (1.9) | |

| Self-employed | 7954 (38.9) | 3563 (49.6) | 2962 (41.5) | 558 (41.3) | 767 (33.4) | 104 (2.1) | |

| Unemployed | 10064 (37.7) | 3382 (30.6) | 4194 (54.2) | 1021 (48.9) | 1107 (38.9) | 360 (6.8) | |

| Father’s Education | |||||||

| No formal education | 14815 (58.4) | 6095 (65.2) | 4886 (67.0) | 1407 (71.1) | 1575 (52.8) | 852 (16.4) | |

| Primary school or less | 2437 (13.1) | 772 (14.7) | 777 (12.5) | 138 (19.3) | 217 (10.3) | 533 (12.7) | |

| High school | 3106 (23.9) | 766 (17.2) | 1012 (17.2) | 48 (7.5) | 190 (27.8) | 1090 (60.4) | |

| College or more | 592 (4.6) | 130 (2.8) | 204 (3.2) | 29 (2.2) | 42 (6.6) | 187 (12.9) | |

| Father’s Employment | |||||||

| Public | 5223 (28.0) | 1761 (27.8) | 705 (9.3) | 133 (8.1) | 244 (9.5) | 2380 (92.0) | |

| Private | 2049 (7.2) | 261 (4.3) | 640 (7.9) | 207 (20.9) | 897 (41.2) | 44 (2.5) | |

| Self-employed | 11883 (55.9) | 3750 (48.6) | 6010 (81.4) | 992 (58.3) | 972 (39.4) | 159 (3.5) | |

| Unemployed | 3128 (8.9) | 2230 (19.3) | 134 (1.3) | 357 (12.7) | 314 (9.9) | 93 (2.0) | |

|

| |||||||

| Lifecourse SES | |||||||

| Mother’s Education | Own Education | ||||||

| ≥primary | ≥primary* | 897 (6.1) | 151 (6.1) | 192 (2.7) | 63 (5.1) | 61 (5.2) | 430 (17.7) |

| <primary | ≥primary | 424 (1.8) | 146 (2.6) | 68 (1.0) | 106 (5.2) | 25 (2.3) | 79 (2.0) |

| ≥primary | <primary** | 2747 (19.1) | 558 (13.6) | 544 (9.0) | 117 (13.4) | 286 (27.3) | 1242 (63.6) |

| <primary | <primary | 18215 (72.9) | 7147 (77.6) | 6685 (87.5) | 1403 (76.3) | 2055 (65.2) | 925 (17.2) |

| Mother’s Employment | Own Employment | ||||||

| Employed+ | Employed | 1250 (13.0) | 246 (10.3) | 127 (1.6) | 19 (3.0) | 118 (10.4) | 740 (56.4) |

| Employed | Unemployed++ | 3015 (10.4) | 811 (9.5) | 206 (2.8) | 91 (6.7) | 435 (17.3) | 1472 (34.7) |

| Unemployed | Employed | 1150 (8.2) | 511 (14.9) | 262 (3.4) | 92 (8.1) | 206 (14.9) | 79 (2.0) |

| Unemployed | Unemployed | 16868 (68.4) | 6434 (65.3) | 6894 (92.3) | 1487 (82.2) | 1668 (57.4) | 385 (6.9) |

| Father’s Education | Own Education | ||||||

| ≥primary | ≥primary | 1007 (7.0) | 215 (7.5) | 238 (3.3) | 60 (3.4) | 61 (4.9) | 433 (17.5) |

| <primary | ≥primary | 314 (1.0) | 82 (1.2) | 238 (0.3) | 109 (7.0) | 25 (2.6) | 76 (1.7) |

| ≥primary | <primary | 5128 (32.1) | 1453 (26.8) | 1755 (26.3) | 155 (25.3) | 388 (30.7) | 1377 (65.8) |

| <primary | <primary | 15834 (59.9) | 6252 (64.4) | 5474 (70.0) | 1365 (64.4) | 1953 (61.8) | 790 (15.1) |

| Father’s Employment | Own Employment | ||||||

| Employed | Employed | 1587 (15.0) | 381 (14.2) | 188 (2.3) | 45 (6.5) | 201 (13.4) | 772 (56.9) |

| Employed | Unemployed | 5685 (20.2) | 1641 (17.9) | 1157 (14.9) | 295 (22.4) | 940 (37.4) | 1652 (37.5) |

| Unemployed | Employed | 8139 (6.2) | 376 (11.0) | 201 (2.7) | 66 (4.5) | 123 (11.9) | 47 (1.5) |

| Unemployed | Unemployed | 14198 (58.6) | 5604 (58.9) | 5943 (80.0) | 1283 (66.5) | 1163 (37.3) | 205 (4.0) |

Defined as completing either primary school, high school, college or more;

Defined as not completing primary school

Defined as being employed in either public, private, or self/informal employment;

Defined as not being employed

All percentages are weighted percentages

SES and Cancer-Related Risk Factors

The prevalence of overweight/obesity (46% vs. 52%), poor nutrition (50% vs. 57%), smoking (0.4% vs. 1.5%) and alcohol use (7.3% vs. 18%) was lower among women with higher SES based on education status compared with women with lower SES (Table 3). However, physical inactivity was higher among those with higher SES compared with those with lower SES (39% vs. 29%). Similar patterns were observed based on employment measures of SES, although a similar proportion of employed and unemployed women were smokers (1.6% and 1.4% respectively). Overweight/obesity (53% vs. 52%), poor nutrition (53% vs. 57%) and smoking (1.6% vs. 1.4%) was similar between women based on mother’s education, however women with low SES mothers had higher physically inactivity (31% vs. 25%) and alcohol use (19% vs. 11%) rates. Similar patterns were observed based on father’s education, with higher alcohol use among women with low SES fathers compared with those with high SES (22% vs. 10%). Overweight/obesity, poor nutrition, physical inactivity, and smoking were mostly similar based on parental employment status, although alcohol use remained higher among those with parental unemployment.

Table 3.

Distribution of cancer related risk factors by individual, parental and lifecourse SES, 2007 SAGE‡

| SES | Overweight /Obese* | Poor Nutrition* | Physical Inactivity* | Smoking* | Alcohol Use* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual SES | ||||||

| Own Education | ||||||

| ≥primary | 833 (46.0) | 797 (49.7) | 442 (39.1) | 13 (0.4) | 142 (7.3) | |

| <primary | 12300 (52.4) | 13078 (57.3) | 7960 (28.6) | 340 (1.5) | 4172 (17.9) | |

| Own Employment | ||||||

| Employed | 1434 (45.6) | 1367 (41.5) | 736 (30.4) | 60 (1.6) | 405 (10.8) | |

| Unemployed | 11699 (53.6) | 12508 (60.8) | 7666 (29.1) | 293 (1.4) | 3909 (18.8) | |

|

| ||||||

| Parental SES | ||||||

| Mother’s Education | ||||||

| ≥primary | 2409 (53.0) | 2364 (53.0) | 1054 (25.3) | 59 (1.6) | 444 (11.0) | |

| <primary | 10724 (51.5) | 11511 (57.9) | 7348 (30.8) | 294 (1.4) | 3870 (19.1) | |

| Mother’s Employment | ||||||

| Employed | 2878 (54.1) | 2681 (52.3) | 1317 (26.8) | 84 (2.1) | 654 (13.1) | |

| Unemployed | 10255 (51.2) | 11194 (58.1) | 7085 (30.2) | 269 (1.2) | 3660 (18.3) | |

| Father’s Education | ||||||

| ≥primary | 3683 (50.65) | 3820 (54.8) | 1768 (25.9) | 88 (1.5) | 719 (10.3) | |

| <primary | 9450 (52.7) | 10055 (57.9) | 6634 (31.6) | 265 (1.4) | 3595 (21.5) | |

| Father’s Employment | ||||||

| Employed | 4653 (51.8) | 4504 (52.9) | 2496 (28.3) | 121 (1.7) | 1084 (11.3) | |

| Unemployed | 8480 (51.9) | 9371 (58.8) | 5906 (30.0) | 232 (1.3) | 3230 (20.2) | |

|

| ||||||

| Lifecourse SES | ||||||

| Mother’s Education | Own Education | |||||

| ≥primary | ≥primary | 566 (48.3) | 573 (52.4) | 254 (36.7) | 10 (0.5) | 94 (8.5) |

| <primary | ≥primary | 267 (38.3) | 224 (41.0) | 188 (47.1) | 3 (0.2) | 48 (3.3) |

| ≥primary | <primary | 1843 (54.5) | 1791 (53.2) | 800 (21.6) | 49 (2.0) | 350 (11.8) |

| <primary | <primary | 10457 (51.8) | 11287 (58.4) | 7160 (30.4) | 291 (1.4) | 3822 (19.5) |

| Father’s Education | Own Education | |||||

| ≥primary | ≥primary | 622 (46.2) | 613 (50.1) | 303 (39.8) | 10 (0.5) | 92 (7.3) |

| <primary | ≥primary | 211 (44.6) | 184 (47.3) | 139 (34.7) | 3 (0.2) | 50 (7.4) |

| ≥primary | <primary | 3061 (51.6) | 3207 (55.8) | 1465 (22.9) | 78 (1.8) | 627 (10.9) |

| <primary | <primary | 9239 (52.8) | 9871 (58.1) | 6495 (68.4) | 262 (1.4) | 3545 (21.7) |

| Mother’s Employment | Own Employment | |||||

| Employed | Employed | 814 (49.1) | 795 (49.4) | 310 (25.7) | 39 (2.2) | 239 (14.1) |

| Employed | Unemployed | 2064 (60.2) | 1886 (55.9) | 1007 (28.1) | 45 (1.9) | 415 (11.8) |

| Unemployed | Employed | 620 (40.0) | 572 (29.1) | 426 (37.9) | 21 (0.6) | 166 (5.7) |

| Unemployed | Unemployed | 9635 (52.6) | 10622 (61.6) | 6659 (29.3) | 248 (1.3) | 3494 (19.8) |

| Father’s Employment | Own Employment | |||||

| Employed | Employed | 1010 (47.7) | 960 (46.3) | 453 (28.2) | 45 (2.1) | 280 (12.5) |

| Employed | Unemployed | 3643 (54.8) | 3544 (57.8) | 2043 (28.4) | 76 (1.4) | 804 (10.4) |

| Unemployed | Employed | 424 (40.3) | 407 (29.9) | 283 (35.7) | 15 (0.3) | 125 (7.0) |

| Unemployed | Unemployed | 8056 (53.2) | 8964 (61.8) | 5623 (29.4) | 217 (1.4) | 3105 (21.7) |

Number and proportion of women with cancer-related risk factors: BMI (>=25kg/m2) Nutrition (<5 daily servings of fruits and vegetables), physical inactivity (<240 minutes per week), Alcohol (>7 drinks per week) and smoking (current/former smoking)

Defined as both recreational and non-recreational physical activity

Lifecourse SES and cancer-related risk factors

The prevalence of overweight/obesity was lowest among those with increasing lifecourse SES based on parental education (Mothers/own: 38%; Fathers/own: 45%), and highest among those with declining (Mothers/own: 55%) and stable low (Fathers/own: 53%) lifecourse SES. Whereas, over 60% of women with declining lifecourse SES based on mother’s employment were overweight/obese. In addition, the highest prevalence of poor nutrition was among women with stable low lifecourse SES by mother’s or father’s employment (62% and 62%) or education (58% and 58%), while the highest prevalence of physical inactivity was among women with stable low lifecourse SES based on father’s education (68%). Regardless of lifecourse SES measure, smoking prevalence was highest among women with declining lifecourse SES, while alcohol use was higher among women with stable low lifecourse SES (20%–22%).

Adjusted analysis of cancer-related risk factors and SES

Women with low SES based on employment were 30% more likely to be overweight/obese (OR: 1.30, 95% CI: 1.02–1.65), 29% more likely to smoke (OR: 1.29, 95% CI: 1.07–1.55), but 40% less likely to be physically inactive (OR: 0.60, 95% CI: 0.48–0.75). Those with low SES based on education were almost 4 times more likely to exceed alcohol use guidelines (OR: 3.86, 95% CI: 1.23–12.10), and 68% more likely to smoke (OR: 1.68, 95% CI: 1.01–2.80) compared with those of higher SES (Table 4). Women with low SES mothers and fathers based on education were more likely to have poor nutrition (Mothers OR: 1.59, 95% CI: 1.17–2.16; Fathers OR: 1.33, 95% CI: 1.11–1.59) and more likely to smoke (Mothers OR: 1.46, 95% CI: 1.15–1.87; Fathers OR: 2.17, 95% CI: 1.80–2.63) compared with those with high SES parents. Women with stable low lifecourse SES based on father’s education were almost three times more likely to smoke (OR: 2.55, 95% CI: 1.47–4.43), while those with declining lifecourse SES were almost four times more likely to exceed alcohol use guidelines (OR: 3.63, 95% CI: 1.07–12.34). Women with declining and stable low lifecourse SES based on mother’s education were less likely to be physically inactive (declining OR: 0.47, 95% CI: 0.33–0.68; low OR: 0.53, 95% CI: 0.37–0.74), and. In addition, women with declining lifecourse SES based on mothers employment were almost 40% less likely to smoke (OR: 0.36, 95% CI: 0.21–0.61) and less likely to exceed alcohol use guidelines (OR: 0.26, 95% CI: 0.08–0.88).

Table 4.

Multivariable adjusted analysis of cancer-related risk factors by individual, parental and lifecourse SES, 2007 SAGE

| Lifecourse SES a | Overweight/ Obese* | Poor Nutrition* | Physical Inactivity* | Smoking* | Alcohol Use* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual SES | ||||||

| Own Education | ||||||

| ≥primary | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| <primary | 1.13 (0.81–1.57) | 0.79 (0.47–1.33) | 0.49 (0.37–0.66) | 1.68 (1.01–2.80) | 3.86 (1.23–12.10) | |

| Own Employment | ||||||

| Employed | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| Unemployed | 1.30 (1.02–1.65) | 1.15 (0.81–1.65) | 0.60 (0.48–0.75) | 1.29 (1.07–1.55) | 1.433 (0.69–2.97) | |

|

| ||||||

| Parental SES | ||||||

| Mother’s Education | ||||||

| ≥primary | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| <primary | 0.93 (0.75–1.15) | 1.59 (1.17–2.16) | 0.96 (0.76–1.21) | 1.46 (1.15–1.87) | 1.23 (0.67–1.67) | |

| Mother’s Employment | ||||||

| Employed | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| Unemployed | 1.02 (0.80–1.31) | 0.92 (0.65–1.30) | 0.80 (0.62–1.04) | 0.80 (0.60–1.05) | 0.69 (0.33–1.47) | |

| Father’s Education | ||||||

| ≥primary | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| <primary | 1.05 (0.90–1.22) | 1.33 (1.11–1.59) | 0.87 (0.70–1.09) | 2.17 (1.80–2.63) | 0.95 (0.53–1.68) | |

| Father’s Employment | ||||||

| Employed | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| Unemployed | 1.12 (0.95–1.33) | 1.12 (0.85–1.47) | 0.89 (0.74–1.06) | 1.74 (1.41–2.14) | 0.92 (0.52–1.65) | |

|

| ||||||

| Lifecourse SES | ||||||

| Mother’s Education | Own Education | |||||

| ≥primary | ≥primary | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| <primary | ≥primary | 0.69 (0.38–1.25) | 0.94 (0.42–2.09) | 1.13 (0.63–2.03) | 0.37 (0.09–1.57) | 0.42 (0.07–2.71) |

| ≥primary | <primary | 1.07 (0.71–1.63) | 0.60 (0.32–1.13) | 0.47 (0.33–0.68) | 1.16 (0.64–2.10) | 3.22 (0.87–11.91) |

| <primary | <primary | 1.00 (0.69–1.46) | 1.08 (0.57–2.04) | 0.53 (0.37–0.74) | 1.72 (1.00–2.97) | 3.64 (1.00–13.30) |

| Father’s Education | Own Education | |||||

| ≥primary | ≥primary | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| <primary | ≥primary | 0.84 (0.38–1.83) | 1.20 (0.46–3.12) | 0.57 (0.27–1.14) | 0.91 (0.23–3.65) | 0.33 (0.03–3.17) |

| ≥primary | <primary | 1.08 (0.75–1.55) | 0.71 (0.40–1.26) | 0.41 (0.30–0.57) | 1.17 (0.66–2.06) | 3.63 (1.07–12.34) |

| <primary | <primary | 1.13 (0.79–1.61) | 1.03 (0.57–1.83) | 0.50 (0.36–0.69) | 2.55 (1.47–4.43) | 3.23 (0.94–11.16) |

| Mother’s Employment | Own Employment | |||||

| Employed | Employed | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Employed | Unemployed | 1.41 (0.93–2.14) | 1.20 (0.71–2.04) | 0.63 (0.44–0.90) | 0.58 (0.37–0.92) | 0.99 (0.36–2.70) |

| Unemployed | Employed | 1.04 (0.68–1.61) | 0.92 (0.50–1.70) | 0.93 (0.62–1.40) | 0.36 (0.21–0.61) | 0.26 (0.08–0.88) |

| Unemployed | Unemployed | 1.29 (0.89–1.86) | 1.05 (0.61–1.80) | 0.56 (0.40–0.79) | 0.63 (0.42–0.94) | 0.83 (0.28–2.47) |

| Father’s Employment | Own Employment | |||||

| Employed | Employed | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Employed | Unemployed | 1.30 (0.93–1.82) | 1.09 (0.67–1.77) | 0.57 (0.43–0.77) | 0.53 (0.35–0.80) | 0.87 (0.35–2.21) |

| Unemployed | Employed | 1.12 (0.73–1.72) | 0.99 (0.53–1.84) | 0.86 (0.57–1.29) | 0.66 (0.39–1.13) | 0.16 (0.06–0.44) |

| Unemployed | Unemployed | 1.40 (1.02–1.92) | 1.23 (0.76–2.00) | 0.56 (0.42–0.75) | 1.13 (0.76–1.67) | 1.04 (0.37–2.87) |

ORs and 95% CI reported, adjusted for marital status, health status, country, rural/urban residence and age

Each model includes own SES variable and parental SES variable adjusted for covariates

Bold indicate significant ORs

Risk Factors by Lifecourse SES and Country

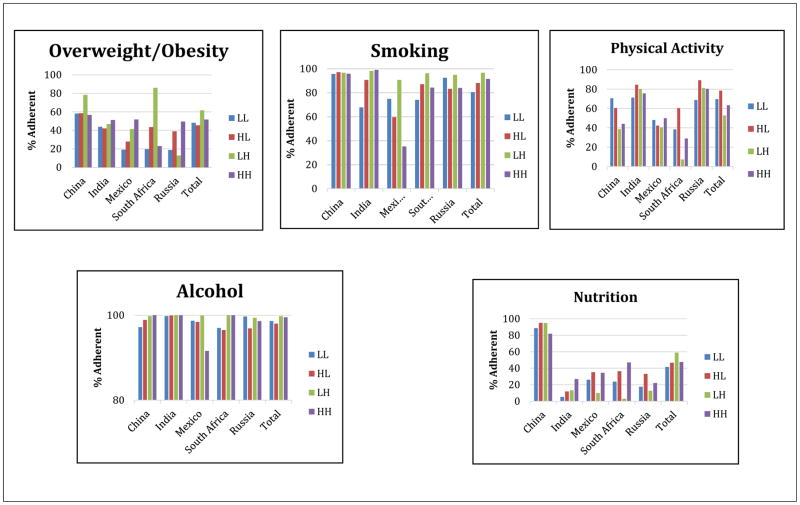

There were country-level differences in lifecourse SES and adherence to each risk factor guideline (Figure 1). There was a positive lifecourse SES gradient in Mexico, with increasing adherence to the BMI criteria with increasing SES, but no gradient observed in China or Russia. There were no gradients in adherence to smoking in China, but a positive gradient (i.e. higher adherence with higher lifecourse SES) in India and a negative gradient in Mexico. In addition, there was a negative SES gradient for physical activity in China, but no clear gradient in Mexico or South Africa. There were positive gradients for alcohol use in China and South Africa, but negative gradient in Mexico, and positive gradients for nutrition in India, but negative gradient in China even though adherence was much higher overall in China.

Figure 1. Adherence to cancer-related risk factor guidelines by life-course SES in 5 SAGE countries, 2007*§.

*Lifecourse SES defined based on maternal education

§ Represents proportion of adults who meet current AICR guidelines on the five cancer-related risk factor

DISCUSSION

Using a large cross-sectional dataset of adult women from five continents and contemporary measures of SES across the lifecourse, we examined social gradients in cancer-related risk factors in China, India, Mexico, South Africa and Russia. Although the majority of study participants had low lifecourse SES, significant country-level differences in the prevalence of cancer-related risk factors were evident as well as strong associations between lifecourse SES and risk factors. Study participants from China were adherent to more risk-factor guidelines than any other country except for physical activity, while participants in South Africa were least likely to be adherent to the physical activity and nutrition guidelines. We observed that lower SES women represented in this study were more likely to be overweight/obese, smoke, and exceed alcohol use guidelines, although they were less likely to be physically active compared with higher SES women. Parental SES measures had significant impacts on cancer risk factors in a similar manner, with poor nutrition and smoking more prevalent among those with low parental SES. Furthermore, declining and low lifecourse SES significantly increased the likelihood of smoking and alcohol use among women.

Our observation of significant variations in cancer-related risk factors across the levels of SES is consistent with previous studies. Similar to recent US studies of SES gradients in cancer-related risk factors- i.e. higher prevalence of obesity, smoking and alcohol among lower SES individuals [32], we also observed higher prevalence of these risk factors in lower SES women, as well as lifecourse SES gradients in this analysis. This may be explained by the recent nutritional transition and trends in dietary and lifestyle patterns associated with increased globalization and westernization observed in many developing countries [33, 34]. Previous studies suggest that higher SES individuals are often the first to adopt new lifestyle related behaviors since they are more likely to afford the high cost of newer, exotic habits such as alcohol consumption and tobacco smoking. However, health related information about the risks (e.g. smoking) and benefits (e.g. physical activity) also tend to be concentrated among higher SES individuals, likely due to better access to high-quality healthcare and health recommendations [35]. Therefore, over time, higher SES individuals tend adopt healthier behaviors and avoid harmful ones, while lower SES individuals begin to adopt the previously unaffordable, exotic risk factors [33, 34]. Other studies have also shown that adverse health behavior, such as smoking, tend to be concentrated among the poor and uneducated [21, 36, 37], since they are least informed about the health risk of smoking and less likely to have access to smoking cessation services [37]. These studies are in line with our findings based on contemporary data and SES measures showing that low SES women have higher prevalence of cancer-related risk factors, except for physical inactivity. This may be because information on the benefits of being physically active has emerged more recently compared with others. It may also be due to the fact that the newly emerging middle-class, who are of higher SES status based on our study measure, are more likely to be employed in professional or service sectors which are highly sedentary in nature.

As projected by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) [38] as well as other investigators[39, 40], the greatest burden of cancer incidence will be experienced in developing countries in the next few decades. Although this trend can be partially attributed to demographic growth and population ageing, increasing prevalence of cancer-related risk factors will also play an important role[41]. For instance, in 2002, about 3.6% of all cancers and 3.5% of all cancer deaths were attributable to alcohol drinking worldwide, with breast cancer comprising 60% of alcohol-attributable cancers[42]. In 2012, 5.5% of all cancers and 5.8% of cancer deaths were attributable to alcohol use[43]. The current inadequacy of cancer screening programs in many developing countries and poor treatment facilities ensures that primary prevention through the elimination of cancer risk factors is the most efficient way of reducing the burden of cancer in these countries. Since cancer-related risk factors vary by SES, both individual and parental, this provides an opportunity to create tailored cancer prevention strategies. For instance, by providing information on the benefits of physical activity and promoting employment-based exercise facilities, higher SES individuals may be encouraged to be more physically active and reduce their cancer risk[44]. For lower SES individuals, prevention efforts may be focused on providing information on the risks associated with smoking and providing free access to smoking cessation services. Among individuals with declining lifecourse SES, efforts may be focused on reducing heavy alcohol consumption and providing educational opportunities or job-training programs. In addition, reducing within-country inequalities in SES will go a long way toward improving access to health information and cancer prevention strategies. Studies have suggested that anti-tobacco smoking policies should be aimed at improving the standard of living among smokers [21].

This study has several strengths and limitations. First, we provide one of the few studies assessing lifecourse SES in relation to cancer-related risk factors using a large dataset of participants from low to middle income countries that together make up about half of the world’s population. The SAGE survey utilized nationally representative study populations and included participants from both rural and urban areas in an effort to increase the generalizability of the results. In addition, we assessed adherence to cancer-related risk factors using established guidelines from the WCRF/AICR, validated measures and cut-points that have been shown to be highly predictive in large cohort studies of cancer[45–48]. One of the limitations of the study is that education and employment measures used in defining lifecourse SES were based on self-reported data, potentially vulnerable to social desirability or recall bias. Nevertheless, these measures have been shown to be more robust compared with income-based measures, particularly parental income[49].

In conclusion, cancer prevention strategies focused on reduction or elimination of the major cancer risk factors are critical in low to middle income countries. The study underscores the importance of tailoring these strategies to different population subgroups based on lifecourse SES.

NOVELTY and IMPACT STATEMENT.

Few data exist on cancer-related risk factors and contemporary measures of SES across the lifecourse in low to middle income countries

Adherence to BMI, physical activity, nutrition, smoking and alcohol guidelines can help reduce the projected increase in cancer incidence in these countries

Low or declining lifecourse SES was significantly associated with increased smoking and alcohol use

High SES was associated with reduced physical activity

Cancer prevention strategies in these countries may benefit from a tailored approach based on the burden of risk factors

Acknowledgments

Dr. Akinyemiju was supported by funds from the UAB Sparkman Center for Global Health.

ABBREVIATIONS

- SAGE

WHO Study on Global Aging and Adult Health

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- SES

Socioeconomic Status

- MICs

Middle Income Countries

References

- 1.Guimaraes JM, et al. Early socioeconomic position and self-rated health among civil servants in Brazil: a cross-sectional analysis from the Pro-Saude cohort study. BMJ Open. 2014;4(11):e005321. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braveman PA, et al. Socioeconomic disparities in health in the United States: what the patterns tell us. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(Suppl 1):S186–96. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.166082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Auchincloss AH, Hadden W. The health effects of rural-urban residence and concentrated poverty. J Rural Health. 2002;18(2):319–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2002.tb00894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khang YH. Lifecourse approaches to socioeconomic health inequalities. J Prev Med Public Health. 2005;38(3):267–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parise CA, Caggiano V. Regional Variation in Disparities in Breast Cancer Specific Mortality Due to Race/Ethnicity, Socioeconomic Status, and Urbanization. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s40615-016-0274-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akinyemiju TF, et al. Early life growth, socioeconomic status, and mammographic breast density in an urban US birth cohort. Ann Epidemiol. 2016;26(8):540–545. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2016.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alberg AJ, et al. Socioeconomic Status in Relation to the Risk of Ovarian Cancer in African-American Women: A Population-Based Case-Control Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;184(4):274–83. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bethea TN, et al. Neighborhood Socioeconomic Status in Relation to All-Cause, Cancer, and Cardiovascular Mortality in the Black Women’s Health Study. Ethn Dis. 2016;26(2):157–64. doi: 10.18865/ed.26.2.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orsini M, et al. Individual socioeconomic status and breast cancer diagnostic stages: a French case-control study. Eur J Public Health. 2016;26(3):445–50. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckv233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akinyemiju TF, et al. Socioeconomic status and incidence of breast cancer by hormone receptor subtype. Springerplus. 2015;4:508. doi: 10.1186/s40064-015-1282-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parise CA, Caggiano V. Disparities in race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status: risk of mortality of breast cancer patients in the California Cancer Registry, 2000–2010. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:449. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ewertz M. Risk of breast cancer in relation to social factors in Denmark. Acta Oncol. 1988;27(6b):787–92. doi: 10.3109/02841868809094358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McWhorter WP, et al. Contribution of socioeconomic status to black/white differences in cancer incidence. Cancer. 1989;63(5):982–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890301)63:5<982::aid-cncr2820630533>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Torre LA, Siegel RL, Jemal A. Lung Cancer Statistics. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016;893:1–19. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-24223-1_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurkure AP, Yeole BB. Social inequalities in cancer with special reference to South Asian countries. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2006;7(1):36–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelsey JL, Bernstein L. Epidemiology and prevention of breast cancer. Annu Rev Public Health. 1996;17:47–67. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.17.050196.000403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heck KE, Pamuk ER. Explaining the relation between education and postmenopausal breast cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145(4):366–72. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tehranifar P, et al. Life course socioeconomic conditions, passive tobacco exposures and cigarette smoking in a multiethnic birth cohort of U.S. women. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20(6):867–76. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9307-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lynch JW, Kaplan GA, Salonen JT. Why do poor people behave poorly? Variation in adult health behaviours and psychosocial characteristics by stages of the socioeconomic lifecourse. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(6):809–19. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00191-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boutayeb A, Boutayeb S. The burden of non communicable diseases in developing countries. Int J Equity Health. 2005;4(1):2. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hosseinpoor AR, et al. Socioeconomic inequality in smoking in low-income and middle-income countries: results from the World Health Survey. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e42843. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kahn RS, Wilson K, Wise PH. Intergenerational health disparities: socioeconomic status, women’s health conditions, and child behavior problems. Public Health Rep. 2005;120(4):399–408. doi: 10.1177/003335490512000407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruder EH, et al. Examining breast cancer growth and lifestyle risk factors: early life, childhood, and adolescence. Clin Breast Cancer. 2008;8(4):334–42. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2008.n.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holman DM, et al. Opportunities for cancer prevention during midlife: highlights from a meeting of experts. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46(3 Suppl 1):S73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amuzu A, et al. Influence of area and individual lifecourse deprivation on health behaviours: findings from the British Women’s Heart and Health Study. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2009;16(2):169–73. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e328325d64d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Institute of Medicine Committee on, H., P. Behavior: Research, and Policy. Health and Behavior: The Interplay of Biological, Behavioral, and Societal Influences. National Academies Press (US) National Academy of Sciences; Washington (DC): 2001. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Myers HF. Ethnicity- and socio-economic status-related stresses in context: an integrative review and conceptual model. J Behav Med. 2009;32(1):9–19. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9181-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jennifer Beam Dowd AZ, Aiello Allison. Early origins of health disparities: burden of infection, health, and socioeconomic status in U.S. children. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Larsen SB, et al. Socioeconomic position and lifestyle in relation to breast cancer incidence among postmenopausal women: a prospective cohort study, Denmark, 1993–2006. Cancer Epidemiol. 2011;35(5):438–41. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yost K, et al. Socioeconomic status and breast cancer incidence in California for different race/ethnic groups. Cancer Causes Control. 2001;12(8):703–11. doi: 10.1023/a:1011240019516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liao Y, et al. Surveillance of health status in minority communities - Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health Across the U.S. (REACH U.S.) Risk Factor Survey, United States, 2009. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2011;60(6):1–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Popkin BM. The nutrition transition and obesity in the developing world. J Nutr. 2001;131(3):871s–873s. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.3.871S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caballero B. Introduction. Symposium: Obesity in developing countries: biological and ecological factors. J Nutr. 2001;131(3):866s–870s. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.3.866S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berenson J, et al. Achieving better quality of care for low-income populations: the roles of health insurance and the medical home in reducing health inequities. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund) 2012;11:1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Teo K, et al. Prevalence of a healthy lifestyle among individuals with cardiovascular disease in high-, middle- and low-income countries: The Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study. Jama. 2013;309(15):1613–21. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.3519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harwood GA, et al. Cigarette smoking, socioeconomic status, and psychosocial factors: examining a conceptual framework. Public Health Nurs. 2007;24(4):361–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2007.00645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ferlay J, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(5):E359–86. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aggarwal A, et al. The challenge of cancer in middle-income countries with an ageing population: Mexico as a case study. Ecancermedicalscience. 2015;9:536. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2015.536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Global Burden of Disease Cancer, C., et al. The Global Burden of Cancer 2013. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(4):505–27. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.0735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bray F, Soerjomataram I. The Changing Global Burden of Cancer: Transitions in Human Development and Implications for Cancer Prevention and Control. In: Gelband H, et al., editors. Cancer: Disease Control Priorities. 3. Vol. 3. Washington (DC): 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boffetta P, et al. The burden of cancer attributable to alcohol drinking. Int J Cancer. 2006;119(4):884–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Praud D, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality attributable to alcohol consumption. Int J Cancer. 2016;138(6):1380–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kyu HH, et al. Physical activity and risk of breast cancer, colon cancer, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, and ischemic stroke events: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. BMJ. 2016;354:i3857. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i3857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Makarem N, et al. Concordance with World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research (WCRF/AICR) guidelines for cancer prevention and obesity-related cancer risk in the Framingham Offspring cohort (1991–2008) Cancer Causes Control. 2015;26(2):277–86. doi: 10.1007/s10552-014-0509-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Catsburg C, Miller AB, Rohan TE. Adherence to cancer prevention guidelines and risk of breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2014;135(10):2444–52. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vergnaud AC, et al. Adherence to the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research guidelines and risk of death in Europe: results from the European Prospective Investigation into Nutrition and Cancer cohort study1,4. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97(5):1107–20. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.049569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Romaguera D, et al. Is concordance with World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research guidelines for cancer prevention related to subsequent risk of cancer? Results from the EPIC study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96(1):150–63. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.031674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Svedberg P, et al. The validity of socioeconomic status measures among adolescents based on self-reported information about parents occupations, FAS and perceived SES; implication for health related quality of life studies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16(1):48. doi: 10.1186/s12874-016-0148-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]