Abstract

Although uterine leiomyomata (fibroids) have been the leading indication for hysterectomy in the United States for decades, the epidemiologic data on fibroid prevalence and risk factors is limited. Given the hormonal dependence of fibroids, most earlier studies focused on reproductive or hormonal factors. Recent analyses have extended that focus to other areas. We present previously unpublished data on the association between reproductive tract infections that highlights the need for more detailed studies. Our review suggests that metabolic, dietary, stress, and environmental factors may also play a role in fibroid development.

Keywords: Uterine leiomyoma, epidemiology, reproductive tract infection, sexually transmitted disease, metabolic factors, diet, environment

Introduction

Fibroids are benign, hormonally responsive tumors of clonal origin (reviewed in Flake et al.1). They are often asymptomatic, but many women experience pelvic pain, reproductive problems, and severe bleeding that can lead to anemia.2 Uterine fibroids have been the leading indication for hysterectomy in the United States for several decades,3,4 and recent hospital costs exceeded $2 billion per year.5

Knowledge of the epidemiology of fibroids before the mid 1990s was based on a small number of studies that identified cases from pathology reports of surgical specimens. Given the wide variation in symptomatology, such a design is likely to identify risk factors for choosing surgical intervention, rather than risk factors for tumor development. More recent studies identify a wider range of cases (i.e., new clinical diagnoses or detection at ultrasound screening).

In this review we present previously unpublished data from our own studies of infection and fibroids, and we review epidemiologic literature published in English from 2004 (earlier data are in previous reviews such as Flake et al.,1 Schwartz et al.,6 and Payson et al.7). First, we briefly describe fibroid prevalence and then focus on studies that have evaluated potential risk factors.

Prevalence of Fibroids

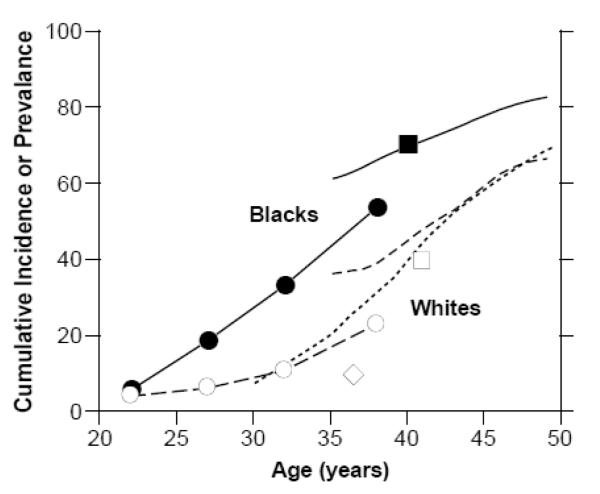

Because many fibroids go undiagnosed, a true estimate of fibroid prevalence requires ultrasound screening. Figure 1 shows the estimated age-specific prevalence or cumulative incidence of fibroids from five epidemiologic studies that used ultrasound screening, three from the United States 8-10 and two from Europe.11,12 The only data for young women come from early-pregnancy screening of pregnant women,10 and it clearly demonstrates earlier onset of fibroids in black compared to white women. Fibroids are likely to be less common among these pregnant women than among the general population because fibroids can interfere with fertility. The data from older women show that the estimated cumulative incidence by age 50, a good measure of lifetime risk, is approximately 70% for whites, and over 80% for blacks. The Italian data12 are very consistent with data on US whites. The data from women in Sweden show much lower prevalence,11 and ultrasound methods cannot account for the difference (personal communication). The only other estimates are based on small numbers or less representative participants. A prevalence of 10% for pregnant Hispanic women from the southern United States, ages 18-42 suggests that Hispanics are more similar to whites than blacks.10 The high prevalence (67%) in Finnish twins, aged 40-47 year olds is similar to U.S. whites.13 To our knowledge no screening data are available for Asian women or other ethnic groups either in or out of the United States. It would be very interesting to have screening data from Africa, the Caribbean, and other black populations to see if the early onset and high cumulative incidence in African Americans is seen in other women of African heritage.

Figure 1.

Age-specific cumulative incidence or prevalence estimates. The closed and open circles are prevalence data averaged over the age ranges shown for black and white women participating in Right From the Start,10 a community-based pregnancy study that screens for fibroids ≥5 mm in diameter at about 7-weeks gestation. The solid line and line of long dashes are cumulative incidence data from the NIEHS Uterine Fibroid Study,8 a study of 35-49 year old health plan members whose fibroid status was based on either ultrasound screening for fibroids ≥5 mm (premenopausal women) or on prior fibroid diagnosis (postmenopausal women). The line of short dashes is cumulative incidence data from the low-exposed group of potentially dioxin-exposed women (Seveso, Italy),12 30-50 year olds whose fibroid status was based on either ultrasound screening for fibroids (premenopausal women) or on prior fibroid diagnosis (postmenopausal women). The squares are average cumulative incidence data for samples of 33-46 year old black and white participants in the CARDIA study,9 a population-based study of cardiovascular disease. The diamond is the average prevalence for fibroids for a group of 33-40 year old representative Swedish women who had ultrasound screening for fibroids of approximately 5 mm or greater in diameter.

Established Risk Factors

Age

As shown in Figure 1, increased age among premenopausal women is a risk factor for fibroids. The cumulative incidence (based both on ultrasound detection of fibroids in women with intact uteri and evidence of prior fibroids among women who have had hysterectomies) increases with age, but the rate of increase slows at older ages (Figure 1). This suggests that the older premenopausal uterus is less susceptible to fibroid development or, more likely, that women who have not developed fibroids by their late 40s are a low risk group.

Reduced risk of receiving a clinical diagnosis of fibroids after menopause was demonstrated in the earlier studies, and confirmed in a more recent study.14 However, the natural history of fibroid change during peri and early post menopause when women experience significant shifts in hormone levels has rarely been studied.15

African American Heritage

Ultrasound screening data for young African Americans and whites10 suggest that age of onset is 10-15 years earlier for African Americans. Figure 1 shows approximately 10 years of steadily and rapidly increasing cumulative incidence beginning around age 25 for blacks and around age 35 for whites.

The higher risk of fibroids that is consistently seen for African Americans compared to whites is not understood. Adjustment for known risk factors did not substantially reduce the risk difference between blacks and whites in the Uterine Fibroid Study.16 Possible explanations include yet-to-be-identified risk factors (such as vitamin D deficiency, stress, or environmental exposures) or genetic susceptibility.

Early Age of Menarche

Most of the early studies reported increased risk of fibroids with earlier age of menarche (reviewed in Schwartz17), and the newer data confirm these findings. The Nurses’ Health and Black Women’s Health Studies as well as unpublished estimates from the Uterine Fibroid Study all show significant associations. Adjusted estimates show elevated risk for women with menarche before age 11 compared to women with menarche after age 13 varying from 25% to 48%).

Early age of menarche is also a risk factor for other hormonally mediated conditions such as endometrial and breast cancer.18,19 The biological mechanisms are not understood and they may or may not be the same for the different hormonally mediated conditions. There may be direct effects from each additional year of hormonal stimulation, but the association could also arise from early life factors that cause both early menarche and adult disease. One possibility to be explored in laboratory studies is that early-life determinants of DNA methylation patterns, such as soy phytoestrogen, may affect the risk of these multiple outcomes.20

Parity

Parity was inversely associated with fibroid risk in the earlier studies (reviewed in Baird and Dunson21), and the newer studies confirm these findings.14,22 The major question regarding these findings is whether this association could be an artifact of reverse causation (i.e., fibroids cause infertility and therefore reduced parity). Although the inverse association is still significant after statistical control for infertility, and protective effects were also seen in experimental data from the Eker rat,23 the controversy has remained.24 The association differs from that seen for breast cancer in that later age at first birth and less time since last birth is protective for fibroids.22,25 Thus, unlike the relation between pregnancy and breast tissue, a single pregnancy does not appear to change the uterine tissue in ways that make it less susceptible to fibroid development. Instead, the epidemiologic protective associations seen with later age at first birth and shorter time since last birth are consistent with pregnancy related elimination of already existing fibroid lesions.21

An observational study that systematically screened for fibroids both in very early pregnancy and again after postpartum uterine remodeling was designed to test for direct protective effects due to elimination of already existing lesions.26 Among the 171 women with a single fibroid seen at the early pregnancy ultrasound screening, 36% had lost the fibroid by the time of the postpartum ultrasound screen 3-6 months after birth. The fibroids that were not eliminated tended to shrink. The degree of elimination and shrinkage was much greater than would be expected based on data from nonpregnant women.27 Furthermore, preliminary analyses from the pregnancy screening study indicate that breastfeeding, a time of low ovarian hormone production, does not mediate the pregnancy associated elimination of fibroids (Laughlin et al. unpublished data). This also is consistent with the epidemiologic data which show no protective affect for breastfeeding.22

Although a direct protective effect of pregnancy has been demonstrated, little is known of the mechanism. Baird and Dunson suggested that during postpartum uterine remodeling there would be selective apoptosis of small lesions,21 but Laughlin et al. showed elimination of large, as well as small, fibroids.26 Ischemia during parturition has also been proposed as a mechanism.28 We suggest that fibroid tissue might be highly susceptible to ischemia during both parturition and remodeling.

Recent Findings on Common Exposures

Smoking

The new studies, including unpublished data from the NIEHS Uterine Fibroid Study, find no association between smoking and fibroids.29 The protective effect that was reported in earlier studies (reviewed in Schwartz et al.6) could have resulted from biases inherent in earlier designs. For example, some used hospital or surgical controls. Because smokers are more likely than nonsmokers to have health problems, they may be over-represented in the control groups creating an artifactual protective association.

Hormonal Contraceptives

The earlier studies showed inconsistent associations between oral contraceptive use and risk of fibroids (reviewed in Flake et al.1). The newer studies show no association (Uterine Fibroid Study, unpublished) or a risk only for oral contraceptive use before age 17.22,25 Although causal mechanisms for increased or decreased risk may exist, findings from earlier studies could be artifactual. Because oral contraceptives can reduce menstrual bleeding, a positive association could arise, especially in case-control studies of surgical fibroid cases, because women with fibroids may take oral contraceptives to control their symptoms. On the other hand, an inverse association could also arise, especially in cohort studies, because women taking oral contraceptives who develop fibroids may have a longer time-to-diagnosis because symptoms are hidden by the oral contraceptive effects.

Progesterone-only pills have not been adequately studied, but injectable progestin contraceptives such as Depo Provera has been associated with reduced risk,22 consistent with an earlier study in Thailand.30 The progestin-IUD has been used to treat fibroid related bleeding,31 but whether it is inversely associated with risk of fibroid development has not been evaluated.

Alcohol and Caffeine

The two recent studies to examine alcohol intake and fibroids both report a positive association, consistent with one,32 but not another33 earlier report. In a health check up with 285 Japanese women which included gynecologic examinations and transvaginal ultrasound, women in the highest alcohol tertile were more likely to have fibroids than women in the lowest tertile (odds ratio = 2.8, 95% confidence interval 1.2,6.2; ≥~1 drink/day vs. non-drinkers).34 Recent data from the Black Women’s Health Study also support an association.29 Current drinkers had significantly higher risk than never drinkers and there appeared to be a dose response for both years of alcohol consumption and drinks per day. The strongest association was with beer, with approximately 60% increase in risk for women drinking 7+ drinks per week compared to nondrinkers. Alcohol is a risk factor for breast cancer, possibly related to elevated estrogen levels.35 However, most studies show no association with endometrial cancer,36 which raises questions about estrogenic effects being the primary mechanism.

Caffeine, which was not associated with fibroids in earlier studies, was examined in the Black Women’s Health Study.29 There was no overall association, but among women <35 years of age the highest categories of caffeinated coffee (≥3 cups/day) and caffeine intake (≥500 mg/day) were both associated with increased fibroid risk.

Body Mass Index (BMI) and Central Fat

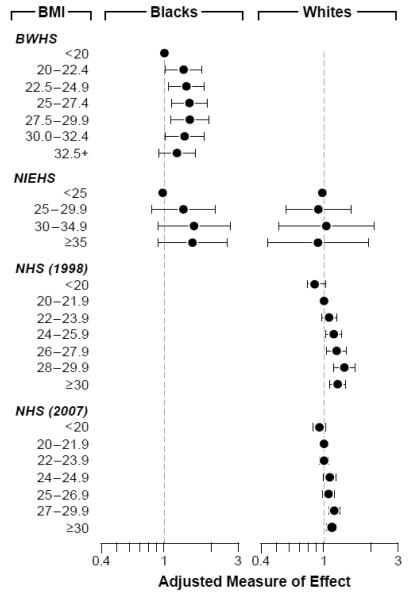

BMI was associated with increased risk in some but not all of the earlier studies. The data from the Nurses’ Health Study II, the Black Women’s Health Study, and the Uterine Fibroid Study are shown in Figure 2. The 12-year followup of nurses (mostly whites)37 showed attenuated risk estimates compared to the 4-year followup,38 and there was no association for whites in the Uterine Fibroid Study with ultrasound screening.39 The estimated effects are stronger for blacks than for whites, and when an association is observed it is nonlinear. Elevated BMI was also associated with increased fibroid development in an Italian14 and a Japanese study.40

Figure 2.

The association between body mass index and fibroid development in the Black Women’s Health Study (BWHS),41 the NIEHS Uterine Fibroid Study (NIEHS),39 and the Nurses Health Study II after a 4-year followup (1998)25 and a 12-year followup (2007)37. The Nurses Health Study II participants are shown in the right column because the cohort is mostly white.

BMI during adolescence and young adulthood has not been associated with risk of fibroids. Central fat as measured by waist circumference or the waist-to-hip ratio, was not associated with elevated fibroid risk in the Black Women’s Health Study41 nor the Uterine Fibroid Study (unpublished data), but the waist-to-hip ratio showed a small but significant trend toward increased risk among nurses in the 12-year followup.37

The peripheral conversion of androgens to estrogens that occurs in fat is unlikely to explain an association between BMI and fibroids because the vast majority of circulating estrogen in premenopausal women is from the ovaries.42 However, BMI is inversely correlated with circulating levels of sex hormone binding globulin, so circulating estrogen and androgen may be more bioavailable in heavy compared to light women.42 Obesity-related anovulation could counteract the elevated bioavailability among the highly obese, accounting for the non-linear risk pattern.

On the other hand, the observed associations are modest in magnitude and could be due to detection bias or uncontrolled confounding. In the large cohort studies that rely on clinical diagnosis, possible BMI-associated increases in menstrual bleeding43 and urinary incontinence44 could increase the probability of a woman’s fibroids being detected.

Importantly, the effect of weight loss on fibroid development has never been prospectively evaluated. For example, a study of fibroid change in women undergoing bariatric surgery might be informative.

New Directions

Infection and Uterine Injury

The idea that injury or reproductive tract infections might trigger fibroid development was introduced decades ago,45 but has never been adequately tested. Two different biological mechanisms of infection-related oncogenesis have been proposed by Cohen.46 The first involves transformation of host-cell gene regulation due to pathogen gene integration. The strongest evidence for Cohen’s first mechanism is the increased risk of leiomyoma in children with AIDs, all cases of which are linked to infection by the Epstein-Barr virus.47 Though these smooth muscle tumors do not occur in the uterus, it does show that smooth muscle may be responsive to viral-initiated tumor development.

Herpes virus infections were evaluated as a potential cause of fibroids using PCR assays to search for viral DNA in fibroid tissue collected from 20 NIEHS Uterine Fibroid Study participants. Participants were selected who had reported sexually transmitted disease history or multiple sexual partners. We examined viral-specific markers for cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus I and II, human herpes virus 6,7,8, and Epstein-Barr virus (probes listed in Table 1). None of these pathogens were detected in any of the tumor samples, but they were successfully identified in positive controls. Though this finding suggests that these pathogens do not remain latent in fibroid tissue, they could still have an acute ‘hit and run’ effect on tumor initiation or tumor growth. No serological studies have been undertaken to evaluate this possibility.

Table 1.

Primer and probe sequences and amplification product length (bp) for real-time quantitative PCR assays for herpesvirus genes in uterine fibroid samples and positive controls.

| HSV1: Glycoprotein G, 81 bp | |

| Primer (forward) | CTG TTC TCG TTC CTC ACT GCC T |

| (reverse) | CAA AAA CGA TAA GGT GTG GAT GAC |

| Probe | TET-CCC TGG ACA CCC TCT TCG TCG TCA G-TAMRA |

| HSV2: Glycoprotein G, 108 bp | |

| Primer (forward) | CAA GCT CCC GCT AAG GAC AT |

| (reverse) | GGT GCT GAT GAT AAA GAG GAT ATC TAG A |

| Probe | FAM-ACA CAT CCC CCT GTT CTG GTT CCT AAC G-TAMRA |

| HHV6: U67, 150 bp | |

| Primer (forward) | GTT AGG ATA TAC CGA TGT GCG TGA T |

| (reverse) | TAC AGA TAC GGA GGC AAT AGA TTT G |

| Probe | FAM-TCC GAA ACA ACT GTC TGA CTG GCA AAA-TAMRA |

| HHV7: Glycoprotein B, 83 bp | |

| Primer (forward) | TTT CCT GTG ACA AAA GAA GCA GTT A |

| (reverse) | ATC CCA CAC GCT TTA CGG G |

| Probe | FAM-TTC CTG CGC AAT AAA GTG AAA ACT GTT AGC ATT-TAMRA |

| HHV8: ORF 73, 142 bp | |

| Primer (forward) | CCG AGG ACG AAA TGG AAG TG |

| (reverse) | GGT GAT GTT CTG AGT ACA TAG CGG |

| Probe | FAM-ACA AAT TGC CAG TAG CCC ACC AGG AGA-TAMRA |

| EBV: Tegument protein, 89 bp | |

| Primer (forward) | TGC GAA AAC GAA AGT GCT TG |

| (reverse) | TAA GTT ACC CGC CAT CCG G |

| Probe | TET-CGC ACG CTA TCC CGC GCC T-TAMRA |

| CMV: Immediate Early protein, 65 bp | |

| Primer (forward) | GCT CTC CCA GAT GAA CCA CC |

| (reverse) | AGG AAC TAT CTT CAT CGG GCC |

| Probe | TET-TCC TCT TCC CGA TCC CTT GGG C-TAMRA |

References for primers and probes: HSV1 and HSV2 modified from Pevenstein et al.,85 HHV6 from Zerr et al.,86 HHV7 from Zerr et al.,87, HHV8 from Lallemand et al.88. Others were designed using Primer Express (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and validated by BioServe Biotechnologies (CMV and EBV). bp = predicted base pair length of amplification product.

The second of Cohen’s mechanisms starts with an injury that may be caused by infection or inflammation and proceeds through several possible pathways leading to increased extracellular matrix, cell proliferation, and decreased apoptosis, apropos of abnormal tissue repair.48-51 The up-regulation of extracellular matrix proteins that is consistently seen in gene profiling studies of fibroids compared with normal myometrium52 is consistent with such a mechanism. Cramer et al. proposed that the process may involve myometrial hyperplasia as a precursor.50,53 The myometrium may be particularly vulnerable to hyperplasia and fibroid development because of normal functional adaptations for pregnancy; specifically the uterus is capable of rapid growth and can be maintained in a state of relative immune suppression, thus precluding the aggressive immune surveillance characteristic of many other tissues.54

There are limited epidemiologic data regarding the second of Cohen’s mechanisms. Chagas’ disease, a parasitic infection common in South America, has been linked to fibroids.55 This parasite can infect uterine smooth muscle cells, so a direct influence is possible. Data from a clinic-based case-control study of fibroids provide more data.56 Cases were 318 premenopausal women with first diagnoses of fibroids based on ultrasound or surgery. Controls were premenopausal women having gynecologic checkups showing no evidence of fibroids. An association with fibroids was seen for history of pelvic inflammatory disease with a dose-response for number of episodes. There was a non-significant increased odds ratio associated with self-reported Chlamydia infection, but not for genital herpes or genital warts. History of an abnormal pap smear was inversely related to fibroid risk.

Factors other than infection could also be important initiators of an injury repair process. Faerstein et al.56 looked at history of IUD use and talc use. IUD was not associated with fibroids, but talc use was related in a dose-dependent manner when frequency of use and number of years of use were examined.

We analyzed the associations of reproductive tract infections and local irritants with fibroids in the NIEHS Uterine Fibroid Study. This analysis was limited to premenopausal women (n=1241) with complete fibroid data (n=1116). Sexually transmitted infection history was ascertained by a mail-in questionnaire from the participant with 91% completing the questionnaire (n=1016). The analyses were done separately for blacks and whites, and we excluded infections in which less than 15 cases were present. This eliminated gonorrhea, trichomonas and syphilis among white women. The talc use history was asked in the follow-up study conducted in 2004 by telephone questionnaire in which 73% of women were retained; talc use was described as genital talc use that was reported as predominantly non-cornstarch type. Logistic regression models were used to assess the association of fibroids and reproductive infections and local irritants that occurred before age 30 adjusted for age, age of menarche, full term pregnancies after age 24, and BMI.

Most infections showed no association with fibroids, although there were positive nonsignificant associations of self-reported Chlamydia infections in white women and trichomonas, syphilis and “other” infections (mainly bacterial vaginosis) in black women, and herpes in both ethnic groups (Table 2). Immunostaining of fixed tissue from 20 surgically removed fibroids (tissues that had also been used to identify herpes viruses described above) showed no evidence of latent Chlamydia infection. Self-reported history of an abnormal pap smear was inversely associated with fibroids among black women and white women, though associations were statistically significant for black women only. Among the non-infectious inflammatory factors, only IUD showed positive associations in both black and white women, but were not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Odds ratios associated with sexually transmitted infections.

| Black | White | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | OR (CI) | p | N (%) | OR (CI) | p | |

| Chlamydia | 42 (8) | 1.14 (0.55, 2.39) | 0.7 | 17 (5) | 1.73 (0.61, 4.93) | 0.3 |

| Gonorrhea | 92 (17) | 1.26 (0.73, 2.16) | 0.4 | 11 (3) | N/A | N/A |

| Pelvic inflammatory disease | 45 (8) | 0.92 (0.45, 1.87) | 0.8 | 15 (4) | 1.23 (0.42, 3.60) | 0.7 |

| Trichomonas | 29 (5) | 3.14 (0.92, 10.69) | 0.07 | 6 (1) | N/A | N/A |

| Genital warts | 41 (7) | 1.05 (0.50, 2.18) | 0.9 | 42 (11) | 1.00 (0.51, 1.96) | 1.0 |

| Genital herpes | 39 (7) | 1.59 (0.70, 3.63) | 0.3 | 38 (10) | 1.40 (0.69, 2.82) | 0.4 |

| Other infection | 35 (6) | 2.09 (0.78, 5.61) | 0.1 | 15 (4) | 1.07 (0.36, 3.21) | 0.9 |

| Abnormal pap smear | 93 (17) | 0.58 (0.36, 0.95) | 0.03 | 61 (16) | 0.78 (0.43, 1.42) | 0.4 |

| Syphilis | 22 (4) | 2.21 (0.63, 7.80) | 0.2 | 1 (0.3) | N/A | N/A |

| Intrauterine device | 165 (27) | 1.40 (0.88, 2.21) | 0.2 | 82 (20) | 1.48 (0.88, 2.50) | 0.1 |

| Douching | 404 (66) | 1.00 (0.68, 1.48) | 1.0 | 59 (14) | 1.14 (0.62, 2.07) | 0.7 |

| Genital talc use | 78 (20) | 0.82 (0.47, 1.43) | 0.5 | 63 (18) | 0.87 (0.49, 1.53) | 0.6 |

| Induced abortion | 421 (67) | 1.26 (0.80, 2.00) | 0.1 | 140 (51) |

1.90 (0.94, 3.82) | 0.8 |

The inverse association of abnormal pap with fibroids is of interest. We do not have details on the severity of the abnormal pap smears or whether HPV was diagnosed. However, HPV is known to be the most common cause of cervical dysplasia and abnormal pap smears.57 We have not tested for HPV in tumor tissue from the study, so we do not know whether there might be latent uterine infection. In a study of cervical and vulvar cancer, HPV was found to insert at chromosome 12q14-15.58 This region is in the region of a translocation that is seen in fibroid tumors that have been reported to reach larger size than chromosomally normal tumors.59 The HPV insertion site is 50-100 kbp from the HMGA-2 gene which can be overexpressed in fibroids.60 HPV insertion may stabilize the region and reduce translocations,58 thus limiting growth. Biological studies of fibroid tissue to assess possible insertion sites and HPV effects are warranted.

In summary, despite biological plausibility, our data provide little additional support for reproductive tract infection and injury as an important cause of uterine fibroids. However, many infections are not clinically diagnosed, and the cross-sectional nature of our study cannot adequately test for causality. A prospective study with enrollment prior to fibroid development and careful ascertainment of infection history with serology data is required. Such a prospective study would also be able to examine another intriguing aspect of the injury hypothesis, that menses is a source of injury. Heavy bleeding may be a cause, as well as a consequence, of fibroids (reviewed in Cramer et al.50), but prospective data on both bleeding and fibroid onset are required to examine this idea.

Hormonal, Metabolic, Dietary, Stress, and Environmental Factors

Table 3 summarizes the recent literature on newly-explored risk factors from epidemiologic studies. The new data come mostly from four studies, The Nurses’ Health Study II, the Black Women’s Health Study, TULEP (The Uterine Leiomyomata Epidemiology Project) done through Group Health in Washington, and the NIEHS Uterine Fibroid Study. The Nurses’ Health Study II and the Black Women’s Health Study are large cohort studies that prospectively follow women with biannual questionnaire updates of exposures and outcomes. The Nurses’ Health Study II enrolled over 116,686 nurses, aged 25 to 42 in 1989. The Black Women’s Health Study began in 1995 and enrolled 59,000 U.S. black women aged 21 to 69. The NIEHS Uterine Fibroid Study enrolled approximately 1500 randomly-selected 35-49 year old members of a prepaid health plan in Washington, DC. They screened premenopausal participants with ultrasound to detect and measure all fibroids ≥ 0.5 cm. Fibroid status for postmenopausal women was determined by medical records and self-report of fibroids. Women who self-reported “no fibroids,” who had no ultrasound or medical record data were excluded from analyses. TULEP enrolled 647 newly-identified clinical cases of fibroids identified by ultrasound in women aged 25-59 and 637 controls who were randomly selected plan members with no documentation of a diagnosis of fibroids, age-stratified to cover the same age range as cases. A subset of TULEP controls was screened with ultrasound for undiagnosed fibroids.

Table 3.

Recent epidemiologic literature on the association between metabolic, diet, stress, and environmental factors and uterine fibroids.

| Study | Exposure Assessment | Fibroid Assessment | Sample | Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hormonal factors | |||||

| LH | UFS61 | Urinary LH, 1st morning during 1st or last 5 d of menstrual cycle |

Ultrasound screening | Premenopausal 35-49 year olds 309 blacks, 214 whites |

LH tertiles, mid, high vs. lowest mid: OR=1.7(1.0,2.7) high: OR=2.0(1.2,3.4) Effect stronger for larger fibroids Bayesian survivorship analysis suggests effect is on tumor onset, not growth LH did not change age association with fibroids |

| Metabolic and vascular factors | |||||

| Physical activity | UFS39 | Self-report time walking, moderate and vigorous recreation, chores low=bottom tertile medium=mid tertile high=67-83rd percentile very high=84+ percentile |

Ultrasound screening | Pre and postmenopausal 35-49 year olds 730 blacks, 454 whites |

Very high vs low OR=0.6 (0.4,09) Similar for blacks and whites but adding data on household chores important only for blacks Reverse causation evaluated by dropping women with major symptoms |

| IGF-1, BP3, insulin, diabetes |

UFS63 | Fasting plasma IGF-1, BP3, insulin, self-reported diabetes |

Ultrasound screening | Premenopausal 35-49 year olds 585 blacks, 403 whites |

IGF-1: blacks, no association, whites mid and upper tertiles vs lowest OR 0.6 (0.3,1.0), 0.6 (0.4,1.1), respectively; BP3: no associations Insulin (association with large fibroids only) high vs. lowest tertile blacks 0.4 (0.2,0.9), whites 0.6 (0.2,2.1) Diabetes: blacks 0.5 (0.2,1.0), whites 0.8 (0.2,3.4) |

| PCOS, diabetes | BWHS64 | Self-report of PCOS, diabetes | Self-report of fibroid on ultrasound or surgery |

~25,000 premenopausal 21-50+ years old, African Americans, no prior diagnosis of fibroids or cancer 6-year follow-up |

PCOS: RR=1.65 (1.21,2.24), effect nonsignificantly stronger for BMI<30 Diabetes without medicine: RR=0.91 (0.64,1.28) Diabetes with medicine: RR=0.77 (0.60,0.98) |

| Blood pressure | NHS66 | Self-reported diastolic (~10mmHg categories) hypertensive medication baseline and follow-up |

Self-report of fibroid on ultrasound or surgery |

~100,000 premenopausal 25-42 year olds, most were white women, no prior diagnosis of fibroids or cancer 10 yr follow-up |

Nonhypertensives: 8% (5%-11%) increased risk for each higher category Hypertensives: 10% (7%-13%) increased risk for each higher category Hypertension: RR=1.24 (1.13,1.40) Effect tended to be stronger for women with higher BMI |

| Diet | |||||

| Isoflavones, lignans |

TULEP71 | Urinary isoflavones and lignans corrected for CR (control means: 2.6 and 4.6 nmol/mg CR, respectively) |

Cases: first clinical diagnosis by ultrasound or surgery records Controls: age-stratified random sample with no record of fibroids (subset had ultrasound screening) |

170 cases; 173 controls most white, black, Asian 58 of controls had ultrasound verification of fibroid status |

Isoflavones: no association Lignans (upper three quartiles vs. lowest) OR=0.60 (0.32,1.15), 0.71 (0.37,1.37) 0.47 (0.23,0.98) Inverse association also seen when data limited to controls with ultrasound verified fibroid status |

| Soy, fiber, fat | Japanese Women’s Health34 |

Food frequency | Ultrasound screening | 285 premenopausal women | No association for soy, fiber, or fat |

| Carotenoids | NHS72 | Food frequency estimates adjusted for bioavailaility for alpha carotene, beta carotene, beta cryptoxanthin, lutein, zeaxanthin, lycopene |

Self-report of fibroid on ultrasound or surgery |

85,512 premenopausal 26-46 year olds, most were white women, no prior diagnosis of fibroids or cancer, 10-yr follow-up |

No association for any carotenoid except beta-carotene in smokers RR=1.36 (1.05,1.76) |

| Stress | |||||

| Perceived racism | BWHS77 | Everyday racism (frequency of poor service, viewed as being unintelligent, dishonest, people are afraid of you, people think they are better than you) Lifetime racism (yes/no to discrimination in job, housing, police) Coping – 9 item scale |

Self-report of fibroid on ultrasound or surgery |

22,002 premenopausal 23-50+ year olds, no prior diagnosis of fibroids or cancer followed for 6 years |

Everyday racism, upper quartiles vs. lowest 1.16(1.04,1,29) 1.19(1.06,1.32) 1.27(1.14,1.43) Lifetime racism upper quartiles vs. lowest 1.04(0.96,1.13) 1.17(1.07,1.28) 1.24(1.10,1.39) Some effects weaker in foreign born, those with vigorous exercise, and those with high coping scores |

| Environmental exposure | |||||

| DES, prenatal | UFS82 | Self-report of prenatal exposure (no, maybe, yes) |

Ultrasound screening | pre and postmenopausal 35-49 year olds 733 blacks, 455 whites |

Exposed (yes vs. no) whites: OR=2.4(1.1,5.4) blacks: n=5 exposed and all had fibroids, so could not analyze Exposed tended to have larger Fibroids |

| DES, prenatal | DES cohorts83 | DES exposure status verified by medical record |

Self-reported surgery for fibroids, verified by medical records |

1731 exposed. 848 unexposed Most were ages 30-50 (age range not given) |

Survivorship analysis from birth to 1994:0.9 (0.6,1.5) No association |

| Dioxin (TCDD) | Seveso Womens Health12 |

Parts per trillion serum TCDD per lipid (triglycerides + cholesterol) collected soon after accident (low ≤20.0, med 20-75.0, high >75.0) |

Self-reported diagnosis (if consistent with medical record) + ultrasound screening (n = 634) |

956 women studied >20 yr after dioxin accident in Seveso, Italy, without diagnosis before accident |

Time to diagnosis analysis upper groups vs low medium: 0.58 (0.41,0.81) high: 0.62(0.44,0.89) |

UFS=NIEHS Uterine Fibroid Study, BWHS=Black Women’s Health Study, NHS=Nurses’ Health Study II

A major limitation of the Nurses’ Health Study II and the Black Women’s Health Study is misclassification in age-specific incident cases and noncases. Self-report of new clinical diagnoses will identify fibroids whose onset was at unknown and variable times prior to diagnosis, while those who have no doctor-diagnosed fibroids (the noncases) may have undiagnosed fibroids. Undiagnosed fibroids are likely to be common considering that half of the 35-49 year old women with ultrasound evidence of fibroids at screening for the NIEHS Uterine Fibroid Study had not had a prior doctor-diagnosis. TULEP shares these limitations, but a subset of controls were screened for fibroids to identify undiagnosed cases. The NIEHS Uterine Fibroid Study with ultrasound screening for fibroids has less misclassification of fibroid status, but as with the other studies, the time of onset for cases could not be determined. In both the Uterine Fibroid Study and TULEP, exposure data were collected essentially simultaneously with fibroid status determination. Though questionnaire data included exposure history data for many exposures (e.g., self-reported body weight at various ages, reproductive history), there was no prospective exposure assessment. Analysis of the data from all of these studies often involved special efforts to evaluate the impact of these design problems, so despite the limitations, major new insights have been gained.

Hormonal factors

One of the recent papers focuses on an endogenous hormone, luteinizing hormone. Baird et al.61 examined the association between LH levels and fibroid development with data from the Uterine Fibroid Study. Given that LH shares a receptor with human chorionic gonadotropin, the hormone that stimulates uterine growth during early pregnancy, they hypothesized that perimenopausal increases in LH would stimulate fibroid growth. As hypothesized, there was significantly increased fibroid development with increasing LH levels. However, the effect was more strongly associated with tumor onset than tumor growth (based on Bayesian survivorship analyses), and the association did not explain any of the age-related increase in tumor development. Further work will be needed to assess whether LH is directly important or serves as a marker of a hormonal milieu that is favorable to fibroid development.

Metabolic factors

Recent studies have examined exercise, insulin-related factors, polycystic ovary disease, and hypertension. Baird et al.39 reported an inverse association for exercise with similar effects in blacks and whites. Insulin and insulin-like-growth-factor 1 (IGF-1) have been hypothesized to increase fibroid risk,62,63 but plasma measurements from the Uterine Fibroid Study found no increase in risk.63 In fact, the data on blacks suggested that insulin and diabetes may have protective effects for fibroids. Diabetes was also associated with decreased fibroid risk in the Black Women’s Health Study,64 but polycystic ovary disease, despite its association with hyperinsulinemia, was associated with increased risk.64 A possible mechanism that could explain the suggested protective effects of hyperinsulinemia and diabetes is the resultant vascular dysfunction. Fibroids may have less vascularization than normal myometrium,65 so further systemic vascular dysfunction might inhibit fibroid development.

Data from the Nurses’ Health Study II on self-reported blood pressure suggest that high blood pressure may contribute to fibroid development.66 Other recent reports have also noted the link between fibroids and hypertension,40,67,68 but for the Nurses Health Study the hypertension predated the fibroid diagnoses, supporting a causal effect rather than shared etiology. Cell-proliferative effects of angiotensin II may mediate such a relationship, and the plausibility of such a mechanism was demonstrated with in vitro study of the Eker rat leiomyoma cell line.69 However, given the potentially long interval between fibroid onset and clinical detection, the possibility of a causal association needs further study.

Dietary factors

Dietary factors affect malignant tumor development,70 but dietary factors have only begun to be examined in relation to fibroids. Data from a subset of participants in TULEP were used to examine soy effects.71 Because soy tends to have anti-estrogenic effects when endogenous estrogens are high (premenopausal women), soy intake might reduce fibroid risk. Urinary isoflavones and lignans were measured as biomarkers of soy intake. The study showed no association with isoflavone. Nor was soy intake (based on food frequency data) associated with fibroids in a cross-sectional study in Japan,34 where intake tends to be higher than in United States. Lignans were inversely related to fibroid prevalence in TULEP. Lignans are found in many fruits and vegetables so the lignan association is consistent with the earlier Italian study that reported protective effects of high fruit and vegetable intake.33 However, using food frequency data on carotenoid intake, another indirect marker of fruit and vegetable intake, the Nurses’ Health Study II does not support a protective effect.72 Alpha carotene showed no association with fibroid risk, and beta carotene appeared to increase risk among smokers, similar to findings for malignant cancers.

Stress

Stress has been suggested to increase risk of disease,73-76 but there are few data regarding fibroids. A single recent paper addresses this issue by examining perceived racism as a chronic stressor among participants in the Black Women’s Health study. Wise et al.77 report increased risk associated with two separate measures of perceived racism. A possible mechanism involves the stress effects on adrenal activity that could raise progesterone levels78 and thus increase fibroid development.

Environmental exposures

Environmental exposures may affect fibroid risk by multiple mechanisms including endocrine disruption. Three recent studies provide new data. Early-life DES exposure in laboratory rodents increases fibroid development in adult animals,79-81 and long-term changes in estrogen-related gene expression have been implicated.81 The data for humans is conflicting. Baird and Newbold, with accurate assessment of fibroid status but self-reported DES exposure, found significantly increased risk,82 but Wise et al., with medically documented exposure but fibroid assessment limited to surgical cases, found no association.83 Dioxin effects on fibroid risk were assessed among women followed after the Seveso accident.12 High exposure was associated with reduced risk of fibroids. Dioxin may have anti-estrogen effects, but a recent review of dioxin receptor signaling suggests that it could also limit extracellular matrix production through effects on transforming growth factor beta.84

Future Study

Further analyses of the existing study cohorts are clearly warranted, and data from other cohorts would be very valuable. However, new epidemiologic studies are also needed, especially studies of fibroid onset and fibroid growth. Without data on time of onset it is often unclear whether exposure predates disease. New epidemiologic studies that determine fibroid onset with periodic ultrasound examinations of women who initially show no ultrasound evidence of fibroids are needed to clarify the exposure-disease relationships for such factors as reproductive tract infection or injury, exercise, BMI, blood pressure, diet, and stress. However, identifying risk factors that might help prevent fibroids is not the only strategy. Limiting fibroid growth might also be an effective public health measure. Fibroids that remain small are less likely to have adverse health effects. Imaging studies designed to identify epidemiologic factors that affect fibroid growth would be very valuable.

Acknowledgements

Aimee D’Aloisio and Sharon Myers provided helpful comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Flake GP, Andersen J, Dixon D. Etiology and pathogenesis of uterine leiomyomas: a review. Environmental health perspectives. 2003;111(8):1037–1054. doi: 10.1289/ehp.5787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stewart EA. Uterine fibroids. Lancet. 2001;357(9252):293–298. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03622-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pokras R, Hufnagel VG. Hysterectomy in the United States, 1965-84. American journal of public health. 1988;78(7):852–853. doi: 10.2105/ajph.78.7.852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farquhar CM, Steiner CA. Hysterectomy rates in the United States 1990-1997. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2002;99(2):229–234. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01723-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flynn M, Jamison M, Datta S, Myers E. Health care resource use for uterine fibroid tumors in the United States. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2006;195(4):955–964. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwartz SM, Marshall LM, Baird DD. Epidemiologic contributions to understanding the etiology of uterine leiomyomata. Environmental health perspectives. 2000;108(Suppl 5):821–827. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108s5821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Payson M, Leppert P, Segars J. Epidemiology of myomas. Obstetrics and gynecology clinics of North America. 2006;33(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baird DD, Dunson DB, Hill MC, Cousins D, Schectman JM. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: ultrasound evidence. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2003;188(1):100–107. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bower JK, Schreiner PJ, Sternfeld B, Lewis CE. Black-White differences in hysterectomy prevalence: the CARDIA study. American journal of public health. 2009;99(2):300–307. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.133702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laughlin SK, Baird DD, Savitz DA, Herring AH, Hartmann KE. Prevalence of uterine leiomyomas in the first trimester of pregnancy: an ultrasound-screening study. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2009;113(3):630–635. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318197bbaf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borgfeldt C, Andolf E. Transvaginal ultrasonographic findings in the uterus and the endometrium: low prevalence of leiomyoma in a random sample of women age 25-40 years. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica. 2000;79(3):202–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eskenazi B, Warner M, Samuels S, et al. Serum dioxin concentrations and risk of uterine leiomyoma in the Seveso Women’s Health Study. American journal of epidemiology. 2007;166(1):79–87. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luoto R, Kaprio J, Rutanen EM, et al. Heritability and risk factors of uterine fibroids--the Finnish Twin Cohort study. Maturitas. 2000;37(1):15–26. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(00)00160-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parazzini F. Risk factors for clinically diagnosed uterine fibroids in women around menopause. Maturitas. 2006;55(2):174–179. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2006.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeWaay DJ, Syrop CH, Nygaard IE, Davis WA, Van Voorhis BJ. Natural history of uterine polyps and leiomyomata. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2002;100(1):3–7. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dixon D, Parrott EC, Segars JH, Olden K, Pinn VW. The second National Institutes of Health International Congress on advances in uterine leiomyoma research: conference summary and future recommendations. Fertility and sterility. 2006;86(4):800–806. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.02.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwartz SM. Epidemiology of uterine leiomyomata. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology. 2001;44(2):316–326. doi: 10.1097/00003081-200106000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Purdie DM, Green AC. Epidemiology of endometrial cancer. Best practice & research. 2001;15(3):341–354. doi: 10.1053/beog.2000.0180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colditz GA. Epidemiology of breast cancer. Findings from the nurses’ health study. Cancer. 1993;71(4 Suppl):1480–1489. doi: 10.1002/cncr.2820710413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guerrero-Bosagna CM, Sabat P, Valdovinos FS, Valladares LE, Clark SJ. Epigenetic and phenotypic changes result from a continuous pre and post natal dietary exposure to phytoestrogens in an experimental population of mice. BMC physiology. 2008;8:17. doi: 10.1186/1472-6793-8-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baird DD, Dunson DB. Why is parity protective for uterine fibroids? Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass. 2003;14(2):247–250. doi: 10.1097/01.EDE.0000054360.61254.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wise LA, Palmer JR, Harlow BL, et al. Reproductive factors, hormonal contraception, and risk of uterine leiomyomata in African-American women: a prospective study. American journal of epidemiology. 2004;159(2):113–123. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walker CL, Cesen-Cummings K, Houle C, et al. Protective effect of pregnancy for development of uterine leiomyoma. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22(12):2049–2052. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.12.2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huyck KL, Panhuysen CI, Cuenco KT, et al. The impact of race as a risk factor for symptom severity and age at diagnosis of uterine leiomyomata among affected sisters. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2008;198(2):168–e161. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marshall LM, Spiegelman D, Goldman MB, et al. A prospective study of reproductive factors and oral contraceptive use in relation to the risk of uterine leiomyomata. Fertility and sterility. 1998;70(3):432–439. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(98)00208-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lauchlin SK, Herring AH, Savitz DA, et al. Pregnancy-related fibroid reduction. Fertility and sterility. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.03.035. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peddada SD, Laughlin SK, Miner K, et al. Growth of uterine leiomyomata among premenopausal black and white women. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105(50):19887–19892. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808188105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burbank F. Childbirth and myoma treatment by uterine artery occlusion: do they share a common biology? The Journal of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists. 2004;11(2):138–152. doi: 10.1016/s1074-3804(05)60189-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wise LA, Palmer JR, Harlow BL, et al. Risk of uterine leiomyomata in relation to tobacco, alcohol and caffeine consumption in the Black Women’s Health Study. Human reproduction (Oxford, England) 2004;19(8):1746–1754. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lumbiganon P, Rugpao S, Phandhu-fung S, et al. Protective effect of depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate on surgically treated uterine leiomyomas: a multicentre case--control study. British journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 1996;103(9):909–914. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1996.tb09911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lethaby AE, Cooke I, Rees M. Progesterone or progestogen-releasing intrauterine systems for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) 2005;(4):CD002126. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002126.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marshall LM, Spiegelman D, Barbieri RL, et al. Variation in the incidence of uterine leiomyoma among premenopausal women by age and race. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1997;90(6):967–973. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00534-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chiaffarino F, Parazzini F, La Vecchia C, et al. Diet and uterine myomas. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1999;94(3):395–398. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00305-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nagata C, Nakamura K, Oba S, et al. Association of intakes of fat, dietary fibre, soya isoflavones and alcohol with uterine fibroids in Japanese women. The British journal of nutrition. 2009;101(10):1427–1431. doi: 10.1017/s0007114508083566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Key J, Hodgson S, Omar RZ, et al. Meta-analysis of studies of alcohol and breast cancer with consideration of the methodological issues. Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17(6):759–770. doi: 10.1007/s10552-006-0011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Friberg E, Wolk A. Long-term alcohol consumption and risk of endometrial cancer incidence: a prospective cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(1):355–358. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Terry KL, De Vivo I, Hankinson SE, et al. Anthropometric characteristics and risk of uterine leiomyoma. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass. 2007;18(6):758–763. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181567eed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marshall LM, Spiegelman D, Manson JE, et al. Risk of uterine leiomyomata among premenopausal women in relation to body size and cigarette smoking. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass. 1998;9(5):511–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baird DD, Dunson DB, Hill MC, Cousins D, Schectman JM. Association of physical activity with development of uterine leiomyoma. American journal of epidemiology. 2007;165(2):157–163. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takeda T, Sakata M, Isobe A, et al. Relationship between metabolic syndrome and uterine leiomyomas: a case-control study. Gynecologic and obstetric investigation. 2008;66(1):14–17. doi: 10.1159/000114250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wise LA, Palmer JR, Spiegelman D, et al. Influence of body size and body fat distribution on risk of uterine leiomyomata in U.S. black women. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass. 2005;16(3):346–354. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000158742.11877.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Azziz R. Reproductive endocrinologic alterations in female asymptomatic obesity. Fertility and sterility. 1989;52(5):703–725. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)61020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wegienka G, Baird DD, Hertz-Picciotto I, et al. Self-reported heavy bleeding associated with uterine leiomyomata. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2003;101(3):431–437. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)03121-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hunskaar S. A systematic review of overweight and obesity as risk factors and targets for clinical intervention for urinary incontinence in women. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2008;27(8):749–757. doi: 10.1002/nau.20635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Witherspoon JT, Butler VW. The etiology of uterine fibroids with special reference to the frequency of their occurrence in the Negro: an hypothesis. Surg Gynecol. 1934;58:57–61. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cohen S. Infection, cell proliferation, and malignancy. In: Parsonnet J, editor. Microbes and malignancy Infection as a Cause of Human Cancers. Oxford University Press; New York: 1999. pp. 89–106. [Google Scholar]

- 47.McClain KL, Leach CT, Jenson HB, et al. Association of Epstein-Barr virus with leiomyosarcomas in children with AIDS. The New England journal of medicine. 1995;332(1):12–18. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199501053320103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stewart EA, Nowak RA. New concepts in the treatment of uterine leiomyomas. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1998;92(4 Pt 1):624–627. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00243-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leppert PC, Catherino WH, Segars JH. A new hypothesis about the origin of uterine fibroids based on gene expression profiling with microarrays. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2006;195(2):415–420. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.12.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cramer SF, Mann L, Calianese E, Daley J, Williamson K. Association of seedling myomas with myometrial hyperplasia. Human pathology. 2009;40(2):218–225. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rogers R, Norian J, Malik M, et al. Mechanical homeostasis is altered in uterine leiomyoma. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2008;198(4):474, e471–411. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.11.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Catherino W, Salama A, Potlog-Nahari C, et al. Gene expression studies in leiomyomata: new directions for research. Seminars in reproductive medicine. 2004;22(2):83–90. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-828614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cramer SF, Padela AI, Marchetti CE, Newcomb PM, Heller DS. Myometrial hyperplasia in pediatric, adolescent, and young adult uteri. Journal of pediatric and adolescent gynecology. 2003;16(5):301–306. doi: 10.1016/s1083-3188(03)00158-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Finn OJ. Cancer immunology. The New England journal of medicine. 2008;358(25):2704–2715. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murta EF, Oliveira GP, Prado Fde O, et al. Association of uterine leiomyoma and Chagas’ disease. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 2002;66(3):321–324. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.66.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Faerstein E, Szklo M, Rosenshein NB. Risk factors for uterine leiomyoma: a practice-based case-control study. II. Atherogenic risk factors and potential sources of uterine irritation. American journal of epidemiology. 2001;153(1):11–19. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.zur Hausen H. Papillomavirus infections--a major cause of human cancers. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 1996;1288(2):F55–78. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(96)00020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lopez-Borges S, Gallego MI, Lazo PA. Recurrent integration of papillomavirus DNA within the human 12q14-15 uterine breakpoint region in genital carcinomas. Genes, chromosomes & cancer. 1998;23(1):55–60. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2264(199809)23:1<55::aid-gcc8>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wei JJ, Chiriboga L, Mittal K. Expression profile of the tumorigenic factors associated with tumor size and sex steroid hormone status in uterine leiomyomata. Fertility and sterility. 2005;84(2):474–484. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.01.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Klemke M, Meyer A, Nezhad MH, et al. Overexpression of HMGA2 in uterine leiomyomas points to its general role for the pathogenesis of the disease. Genes, chromosomes & cancer. 2009;48(2):171–178. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Baird DD, Kesner JS, Dunson DB. Luteinizing hormone in premenopausal women may stimulate uterine leiomyomata development. Journal of the Society for Gynecologic Investigation. 2006;13(2):130–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cramer SF, Robertson AL, Jr., Ziats NP, Pearson OH. Growth potential of human uterine leiomyomas: some in vitro observations and their implications. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1985;66(1):36–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Baird DD, Travlos G, Wilson R, et al. Uterine leiomyomata in relation to insulin-like growth factor-I, insulin, and diabetes. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass. 2009;20(4):604–610. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31819d8d3f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wise LA, Palmer JR, Stewart EA, Rosenberg L. Polycystic ovary syndrome and risk of uterine leiomyomata. Fertility and sterility. 2007;87(5):1108–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Walocha JA, Litwin JA, Miodonski AJ. Vascular system of intramural leiomyomata revealed by corrosion casting and scanning electron microscopy. Human reproduction (Oxford, England) 2003;18(5):1088–1093. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Boynton-Jarrett R, Rich-Edwards J, Malspeis S, Missmer SA, Wright R. A prospective study of hypertension and risk of uterine leiomyomata. American journal of epidemiology. 2005;161(7):628–638. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Silver MA, Raghuvir R, Fedirko B, Elser D. Systemic hypertension among women with uterine leiomyomata: potential final common pathways of target end-organ remodeling. Journal of clinical hypertension (Greenwich, Conn. 2005;7(11):664–668. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2005.04384.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Settnes A, Andreasen AH, Jorgensen T. Hypertension is associated with an increased risk for hysterectomy: a Danish cohort study. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology. 2005;122(2):218–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Isobe A, Takeda T, Sakata M, et al. Dual repressive effect of angiotensin II-type 1 receptor blocker telmisartan on angiotensin II-induced and estradiol-induced uterine leiomyoma cell proliferation. Human reproduction (Oxford, England) 2008;23(2):440–446. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Divisi D, Di Tommaso S, Salvemini S, Garramone M, Crisci R. Diet and cancer. Acta Biomed. 2006;77(2):118–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Atkinson C, Lampe JW, Scholes D, et al. Lignan and isoflavone excretion in relation to uterine fibroids: a case-control study of young to middle-aged women in the United States. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2006;84(3):587–593. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.3.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Terry KL, Missmer SA, Hankinson SE, Willett WC, De Vivo I. Lycopene and other carotenoid intake in relation to risk of uterine leiomyomata. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2008;198(1):37, e31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Antoni MH, Lutgendorf SK, Cole SW, et al. The influence of bio-behavioural factors on tumour biology: pathways and mechanisms. Nature reviews. 2006;6(3):240–248. doi: 10.1038/nrc1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Godbout JP, Glaser R. Stress-induced immune dysregulation: implications for wound healing, infectious disease and cancer. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2006;1(4):421–427. doi: 10.1007/s11481-006-9036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lupien SJ, McEwen BS, Gunnar MR, Heim C. Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10(6):434–445. doi: 10.1038/nrn2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Figueredo VM. The time has come for physicians to take notice: the impact of psychosocial stressors on the heart. The American journal of medicine. 2009;122(8):704–712. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wise LA, Palmer JR, Cozier YC, et al. Perceived racial discrimination and risk of uterine leiomyomata. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass. 2007;18(6):747–757. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181567e92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wirth MM, Meier EA, Fredrickson BL, Schultheiss OC. Relationship between salivary cortisol and progesterone levels in humans. Biological psychology. 2007;74(1):104–107. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Newbold R. Cellular and molecular effects of developmental exposure to diethylstilbestrol: implications for other environmental estrogens. Environmental health perspectives. 1995;103(Suppl 7):83–87. doi: 10.1289/ehp.95103s783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Newbold RR, Moore AB, Dixon D. Characterization of uterine leiomyomas in CD-1 mice following developmental exposure to diethylstilbestrol (DES) Toxicologic pathology. 2002;30(5):611–616. doi: 10.1080/01926230290105839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Greathouse KL, Cook JD, Lin K, et al. Identification of uterine leiomyoma genes developmentally reprogrammed by neonatal exposure to diethylstilbestrol. Reproductive sciences (Thousand Oaks, Calif. 2008;15(8):765–778. doi: 10.1177/1933719108322440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Baird DD, Newbold R. Prenatal diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure is associated with uterine leiomyoma development. Reproductive toxicology (Elmsford, NY. 2005;20(1):81–84. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wise LA, Palmer JR, Rowlings K, et al. Risk of benign gynecologic tumors in relation to prenatal diethylstilbestrol exposure. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2005;105(1):167–173. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000147839.74848.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gomez-Duran A, Carvajal-Gonzalez JM, Mulero-Navarro S, et al. Fitting a xenobiotic receptor into cell homeostasis: how the dioxin receptor interacts with TGFbeta signaling. Biochemical pharmacology. 2009;77(4):700–712. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pevenstein SR, Williams RK, McChesney D, et al. Quantitation of latent varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex virus genomes in human trigeminal ganglia. Journal of virology. 1999;73(12):10514–10518. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.10514-10518.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zerr DM, Gooley TA, Yeung L, et al. Human herpesvirus 6 reactivation and encephalitis in allogeneic bone marrow transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(6):763–771. doi: 10.1086/322642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zerr DM, Huang ML, Corey L, et al. Sensitive method for detection of human herpesviruses 6 and 7 in saliva collected in field studies. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2000;38(5):1981–1983. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.5.1981-1983.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lallemand F, Desire N, Rozenbaum W, Nicolas JC, Marechal V. Quantitative analysis of human herpesvirus 8 viral load using a real-time PCR assay. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2000;38(4):1404–1408. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.4.1404-1408.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]