Cervical cancer is the second most commonly diagnosed cancer in females and is a leading cause of cancer‐related mortality in Kenya; limited cervical cancer screening services may be a factor. This study's novel findings on barriers to and benefits of cervical cancer screening in Kenya can inform the development of targeted community outreach activities, communication strategies, and educational messages for patients, families, and providers.

Keywords: Cervical cancer, Perceptions, Focus groups, Screening, Kenya

Abstract

Background.

Cervical cancer is the second most commonly diagnosed cancer in females and is a leading cause of cancer‐related mortality in Kenya; limited cervical cancer screening services may be a factor. Few studies have examined men's and women's perceptions on environmental and psychosocial barriers and benefits related to screening.

Materials and Methods.

In 2014, 60 women aged 25–49 years and 40 male partners participated in 10 focus groups (6 female and 4 male), in both rural and urban settings (Nairobi and Nyanza, Kenya), to explore perceptions about barriers to and benefits of cervical cancer screening. Focus groups were segmented by sex, language, geographic location, and screening status. Data were transcribed, translated into English, and analyzed by using qualitative software.

Results.

Participants identified screening as beneficial for initiating provider discussions about cancer but did not report it as a beneficial method for detecting precancers. Perceived screening barriers included access (transportation, cost), spousal approval, stigma, embarrassment during screening, concerns about speculum use causing infertility, fear of residual effects of test results, lack of knowledge, and religious or cultural beliefs. All participants reported concerns with having a male doctor perform screening tests; however, men uniquely reported the young age of a doctor as a barrier.

Conclusion.

Identifying perceived barriers and benefits among people in low‐ and middle‐income countries is important to successfully implementing emerging screening programs. The novel findings on barriers and benefits from this study can inform the development of targeted community outreach activities, communication strategies, and educational messages for patients, families, and providers.

Implications for Practice.

This article provides important information for stakeholders in clinical practice and research when assessing knowledge, beliefs, and acceptability of cervical cancer screening and treatment services in low‐ and middle‐resourced countries. Formative research findings provide information that could be used in the development of health interventions, community education messages, and materials. Additionally, this study illuminates the importance of understanding psychosocial barriers and facilitators to cervical cancer screening, community education, and reduction of stigma as important methods of improving prevention programs and increasing rates of screening among women.

Introduction

Among cancers in Kenya, cervical cancer has the second highest incidence rate and is a leading cause of cancer‐related mortality [1], [2]. Although population‐based data on cancers are not currently available in Kenya, 2004–2008 Nairobi Cancer Registry data indicate that cervical cancer accounted for 21% of all cancers among women [1]. In 2012, GLOBOCAN estimated more than 4,800 cases of cervical cancer in Kenya and almost 2,500 deaths due to cervical cancer [2].

Although 70%–80% of cancer cases in Kenya are diagnosed in late stages, some prevention and early detection efforts for cervical cancer, including the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, the Papanicolaou (Pap) test, and visual screening (acetic acid [VIA] or Lugol's iodine [VILI]), are being used [1]. The Kenyan Ministry of Health (KMOH) reported that approximately 300 sites provide or have provided cervical cancer screening services in Kenya [3]. However, the availability of these services is low, as evidenced by a 3.2% cervical cancer screening coverage rate for women aged 18 to 69 years [3].

Low screening coverage has been attributed to several factors, including limited access to and availability of screening services, screening cost, lack of trained service providers, inadequate equipment and supplies, inadequate monitoring and evaluation of screening programs, and a health service system that is overwhelmed by health demands [1]. Although community awareness of cervical cancer may have grown because of the introduction of the HPV vaccine in select areas of Kenya, low levels of knowledge and awareness may be partially responsible for suboptimal screening rates [1]. Other community, patient, and provider barriers may exist, but these have not been explored in detail.

In response to the country's cervical cancer incidence and mortality and in an effort to improve cervical cancer prevention, the KMOH released the National Cervical Cancer Prevention Program (NCCPP) Strategic Plan (2012–2015) [3]. One objective, among several key objectives and strategies, prioritized providing high‐quality services and outlined associated strategies, including reducing the incidence and prevalence of cervical cancer and providing cervical cancer screening. To meet these objectives, the plan specified that a key program output was to “increase awareness of cervical cancer prevention so that health personnel, other relevant government staff, community leaders and eligible women and their male partners understand the need for cervical cancer prevention services and support utilization of available services” [3].

To promote behavior change consistent with these goals and ensure effective implementation and uptake of prevention strategies, routine monitoring and identification of barriers and benefits related to cervical cancer screening, as perceived by women and their male partners, are needed. Previous studies have examined these factors among general populations of Kenyan women; however, few studies have focused on perceptions among women who have previously received cervical cancer screening versus those among women who have not. Additionally, no published studies have examined barriers and benefits to screening, as perceived among male partners of women who have been tested versus among men whose partners have not. The current study on screening beliefs among women and male partners, segmented by screening status, can be used to inform the development of cervical cancer educational materials, community mobilization efforts, communication campaigns, and stakeholders and beneficiaries of the KMOH's NCCPP.

Materials and Methods

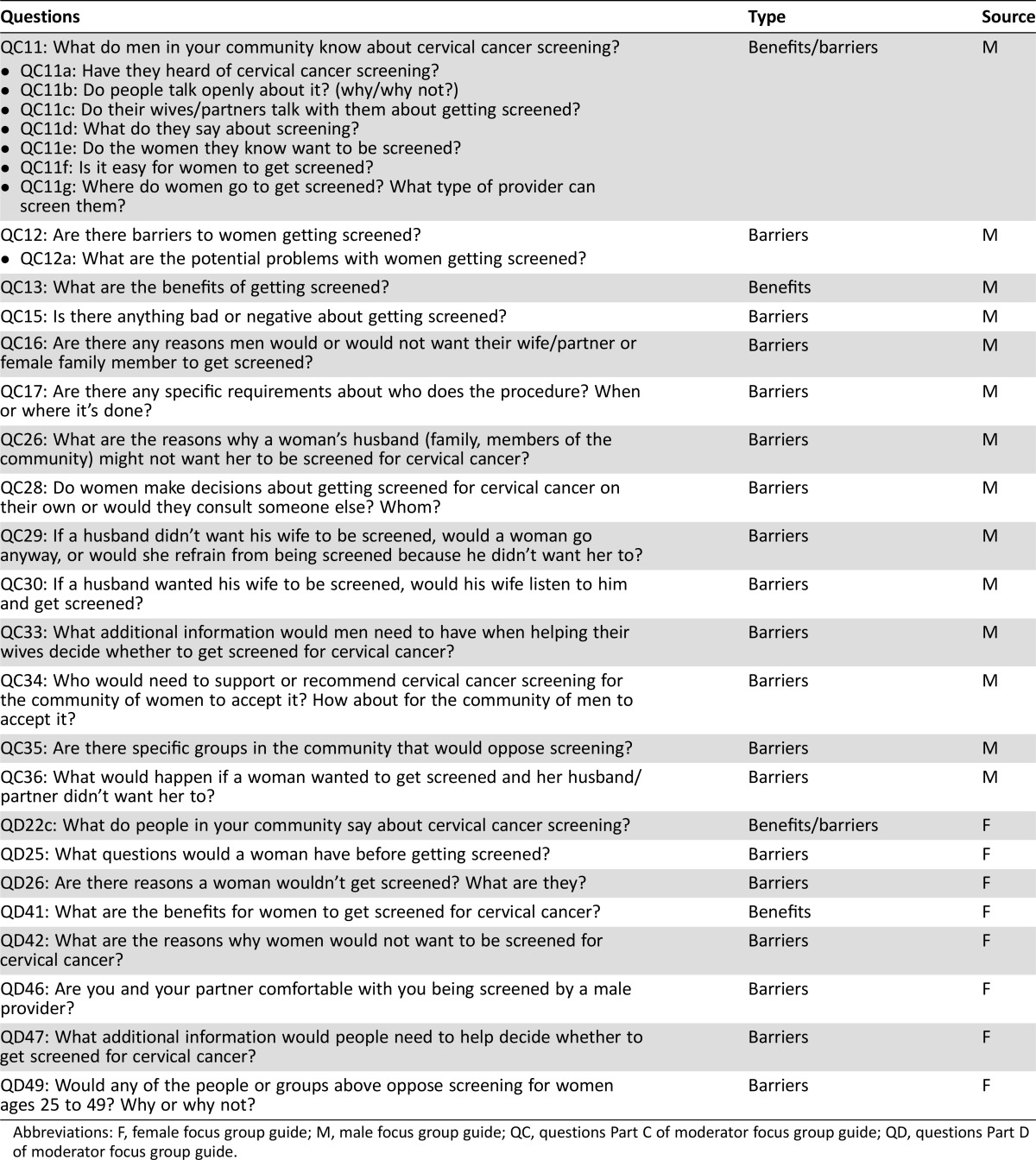

Data from female and male partners were collected through focus group discussions in urban Nairobi and rural Nyanza sites (southwestern Kenya) to evaluate knowledge and beliefs related to cancer and cervical cancer, potential barriers and benefits related to cervical cancer screening, and acceptability of health services and educational messages (Table 1). Nairobi and Nyanza sites were selected because of (a) high rates of cervical cancer; (b) KMOH NCCPP projections of increased provision of cervical cancer services; and (c) good distribution between urban versus rural, high and low socioeconomic status, and existing health facilities offering cervical cancer services.

Table 1. Focus group segmentation strategy: Number of focus groups and participants.

For male participants, receipt or nonreceipt of screening refers to the status of his wife aged 25–49 years.

Values are expressed as number of focus groups, with participant numbers in each geographic location listed in parentheses.

Obtaining Community Support and Mobilization

Before study recruitment, three district community advisory board meetings in Nyanza and Nairobi were convened with relevant stakeholders (men and women from the target communities, church leaders, district chiefs, health care providers, and community health workers). Participants engaged in a 2‐hour meeting and reviewed study objectives and plans for future cervical cancer screening and treatment efforts. Meetings were convened in centrally located, easily accessible venues. Participants were given a bar of soap (a standard remuneration for similar research studies in Kenya) and transportation reimbursement (up to 400 Kenyan shillings per round trip, based on Kenya Medical Research Institute [KEMRI]/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] guidelines).

Recruitment and Consent of Focus Group Participants

Community mobilizers were invited by medical providers, district chiefs, and community advisory board members to recruit study participants from health care and community forums routinely attended by men and women. Participants were given the option to immediately participate in a study screening session to determine their eligibility for inclusion or elect to participate in a session at a later date. Participants who met study selection criteria included a woman aged 25–49 years or a man aged ≥18 years and married to a woman aged 25–49 years, a resident of Nairobi or Nyanza, and willingness to participate in an audio‐recorded focus group for up to 2 hours. All accepted participants were briefed on the purpose of the study by a trained study staff member and signed an informed consent form.

Pilot Testing and Focus Groups

Guide manuals for conducting the semi‐structured focus groups were developed and pilot tested by trained moderators to ensure regional sensitivity, comprehension, and consistency and to ascertain that questions could be addressed in the allotted time. After pilot testing, manuals were reviewed by investigators and revised as needed. As was information from the focus group sessions, all information collected during pilot testing was audio recorded, transcribed, translated, and back‐translated by trained study staff with proficiency in English and Dholuo and/or Kiswahili.

Investigators then convened 10 focus groups (6 female‐only and 4 male‐only) with 10 participants in each group (n = 100). In addition to sex, groups were segmented according to geographic location (Nairobi versus Nyanza) and screening status (previously screened or not) of female participants or female partners of male participants (Table 1). Investigators did not formally examine the method of screening (Pap versus VIA/VILI) or whether screening was conducted for early detection (in asymptomatic women) or after symptom presentation. However, the majority of screened respondents from Nairobi described receiving a Pap test, whereas those in Nyanza described receiving VIA/VILLI. On the basis of segmentation criteria, participants were classified into one of eight categories: (a) male partners of unscreened women in Nairobi (US‐Nai men) or (b) in Nyanza (US‐Ny men), (c) male partners of screened women in Nairobi (S‐Nai men) or (d) Nyanza (S‐Ny men), (e) unscreened women in Nairobi (US‐Nai women) or (f) Nyanza (US‐Ny women), or (g) screened women in Nairobi (S‐Nai women) or (h) Nyanza (S‐Ny women).

Focus group discussions lasted no more than 2 hours and took place in health sector offices or health care sites with private conference rooms. Questions from the guide manuals were used to generate discussion. The lead moderator for each focus group—one female and one male each for Nairobi and Nyanza, matched to sex of group participants—was a Kenyan with experience moderating focus group discussions. Each group included two additional attendees of the same sex as the participants: a staff member to ensure that participants did not disclose personal information and a note taker. The focus groups in Nyanza were conducted in the Dholuo language, and those in Nairobi were conducted in Kiswahili.

Analysis

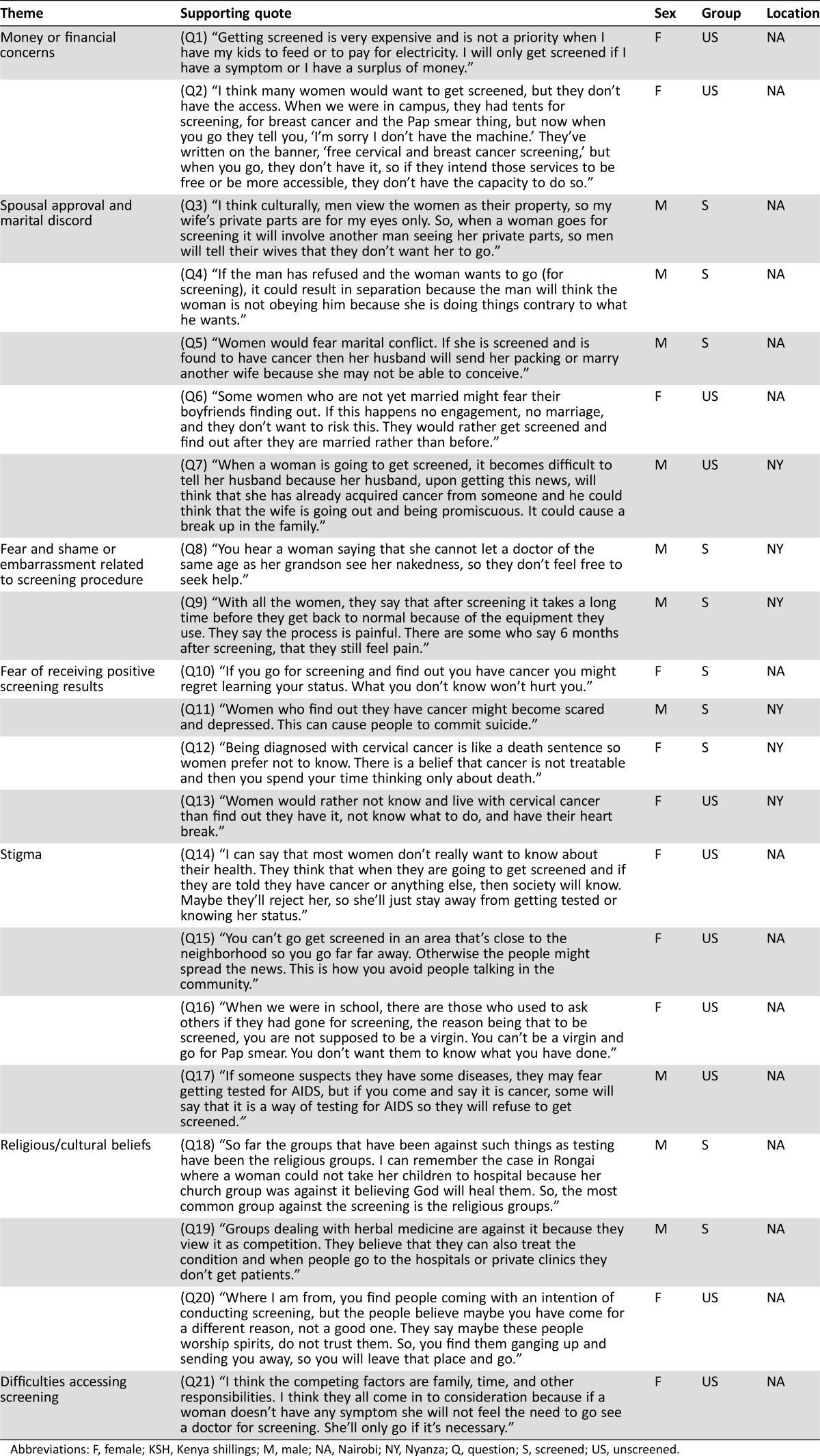

Focus group responses were reported separately for female and male participants and segmented by screening status and geographic region. Four team members reviewed transcripts to ensure accuracy and completeness of translation against focus group notes. All final transcripts were uploaded to NVivo 10 software (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia, http://www.qsrinternational.com/) for analysis, and data were analyzed by using grounded theory [4]. Reviewers trained in qualitative thematic analysis reviewed the data and developed codes (themes) based on questions from the manuals. All themes were coded by two reviewers and tested for quality assurance and accuracy (reliability rate ≥85%). Two themes emerged during analysis: screening barriers and screening benefits. The questions used to assess screening barriers and benefits are listed in Table 2.

Table 2. Kenya Qualitative Assessment Study analytic questions.

Abbreviations: F, female focus group guide; M, male focus group guide; QC, questions Part C of moderator focus group guide; QD, questions Part D of moderator focus group guide.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Of the 100 participants, half lived in Nairobi and half in Nyanza. Half of participants were primary Dholuo speakers, and 100% spoke Kiswahili as a primary or secondary language. Among female participants, two thirds (66%) had never been screened; half of male participants stated that their female partners had never been screened. The mean age of female and male participants was 32.5 years and 37.1 years, respectively.

Perceived Benefits to Receiving a Cervical Cancer Screening

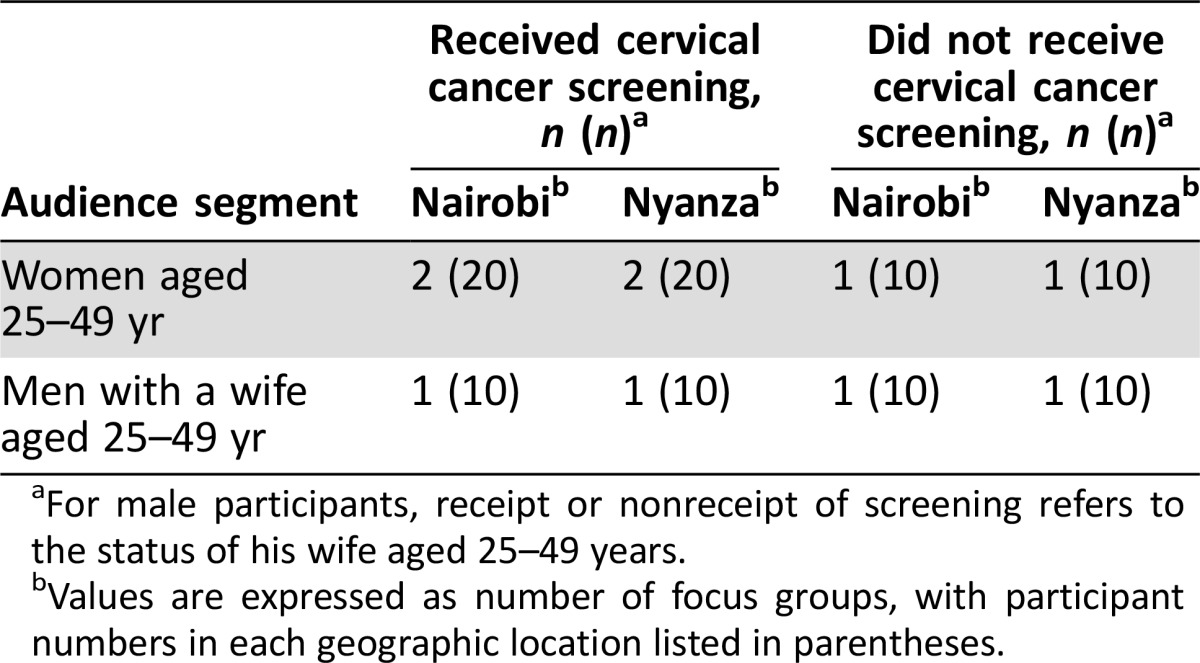

Responses are outlined below. Some specific responses (translated quotations) are available in Table 3. Alphanumeric designations in the text refer to relevant quotation numbers.

Table 3. Barriers to cervical cancer screening, select quotes by theme, Kenya Qualitative Assessment Study, 2012–2015.

Abbreviations: F, female; KSH, Kenya shillings; M, male; NA, Nairobi; NY, Nyanza; Q, question; S, screened; US, unscreened.

Most male and female participants reported that screening was beneficial as a method to (a) help women know more about their health status and (b) detect cervical cancer in earlier stages in order to allow those affected to benefit from available treatment. Neither women nor men mentioned screening as a beneficial method of detecting precancerous lesions before they develop into cancer.

Knowing Your Health Status.

Screening helped women to engage with medical providers and learn about their general health, as well as about cervical cancer. Most S‐Nai women noted feeling happy and proud for “making their health a priority” by going for screening, while some S‐Ny women perceived eliminating the stress of not knowing whether they had cervical cancer as a benefit.

Most US‐Nai men and US‐Ny men reported that screening was beneficial when women brought back health information to their residential communities. Unlike other groups, US‐Ny men reported a benefit for women who had experienced severe pain (potentially due to cervical cancer symptoms) before the examination, learning whether they had cervical cancer, and sharing this information with their husbands. Participants felt that sharing this information could prompt men, who might insist on intercourse, to consider the pain that this might cause their wives if left unaddressed.

Early Detection and Treatment.

Most women agreed that screening is helpful in detecting cervical cancer at earlier stages and can lead to lifesaving treatment when indicated. S‐Ny women also commented that, when discovered early, cervical cancer is easier to treat, and US‐Nai women mentioned that early screening could lead to getting a doctor's advice about reducing cancer risk.

Most men agreed that women could die of cancer if it was not detected early and that screening could save lives and prolong life when cancer was detected early. Some US‐Ny men stated that screening needs to be “compulsory, like visiting the antenatal clinic for mothers.”

Barriers to Screening

Perceived screening barriers included (a) money or financial concerns, (b) spousal approval and marital discord, (c) fear and shame or embarrassment related to the screening procedure, (d) fear of receiving positive screening results, (e) stigma, (f) lack of knowledge, (g) religious or cultural beliefs, and (h) difficulties accessing screening.

Money or Financial Concerns.

All participants noted the cost of screening as a barrier. Most screened women mentioned that women would not go for screening if it was not free, unscreened women and male partners reported that screening was “too expensive,” and some would not get screened without incentives (Table 3; Q1). Some unscreened women also stated that some sites offer free screening, but on arriving they have found services no longer available or not really free (Q2).

Citing a lack of finances, most S‐Nai, US‐Nai, and US‐Ny men perceived screening as a “burden” to partners who pay for it and possibly for treatment, if cervical cancer is discovered. Most S‐Nai men did agree that women can receive financial support from “women's groups” for screening, if offered at a low cost. However, most men in this group reported that “people don't know how much screening costs.”

Spousal Approval and Marital Discord.

Male and female respondents reported that men are not always accepting of women going for a screening. Spousal disapproval was often related to feeling uncomfortable about another man seeing his wife's body (Table 3; Q3). Although some US‐Nai men reported that some doctors refuse to test women without a husband's consent, most male and female Nairobi participants agreed that it is not uncommon for women to go for screening without a husband's knowledge and to “sneak when he is not around.” Women and men in Nyanza did not report that women routinely go for screening without their husband's knowledge. While women may still choose to go for screening, both men and women in Nairobi reported that concerns about marital discord and separation exist for women who are screened without their husband's knowledge. Some men in Nairobi reported that wives who don't inform their husbands of their decision to get tested could be perceived as being deceptive and “disobedient” (Q4).

Most Nyanza participants noted concerns about marital discord, separation, and spousal abandonment as barriers to screening. All men and US‐Ny women reported that marital discord largely occurs when a woman informs her husband of her need to abstain from intercourse after screening. Men and women did not clearly understand the rationale for abstinence and its relationship to cryotherapy (not the actual screening procedure). Most US‐Ny men reported that marital issues, including separation and infidelity, are concerns for women tested and found to have cervical cancer because some believe that women diagnosed with cervical cancer cannot conceive (Q5). Some US‐Nai women reported that unmarried women fear that their partner would suspect them of having cervical cancer if they got tested and subsequently refuse to marry them (Q6).

Most US‐Nai and US‐Ny men reported that women liken cervical cancer to infectious diseases that can be acquired through sexual intercourse, like HIV infection. (The link between HPV and cervical cancer is not well understood.) For this reason, men reported that a woman who goes for screening might be suspected of being promiscuous (Q7).

Fear and Shame or Embarrassment Related to the Screening Procedure.

All participants reported concerns about women being fully or partially nude during screening, especially with a male doctor. Women noted feeling “embarrassed” (Nyanza) or that disrobing was “shameful” (Nairobi). Some US‐Nai and US‐Ny men stated that women would be uncomfortable and not go for screening with a younger doctor (Table 3; Q8). Despite these concerns, half of unscreened females and US‐Ny men felt that women should get tested by a qualified doctor, even if male. Some US‐Ny women also compared male doctors conducting screenings to helping women to give birth, an “acceptable practice.” Some US‐Nai women reported that disrobing in front of a female doctor would be more acceptable but that they might fear being “judged” by her.

Some S‐Nai women mentioned concerns about speculum use causing infertility. Most Nairobi and Nyanza women and S‐Nai and S‐Ny men reported that women fear “pain” or “discomfort” from the speculum used during screening. These men felt that these fears would prevent women from being screened, even if free, and that any pain could persist long after the procedure (Q9). A few unscreened women also believed that screening was not for women who had never been sexually active because of concerns about a hymen breaking after speculum use.

Fear of Receiving Positive Screening Results.

Men and women reported fear of receiving positive screening results as a barrier. Most S‐Nai women agreed that some women do not get screened because they think that they will regret it if they find out that they have cervical cancer (Table 3; Q10). Most US‐Nai women felt that women fear getting positive results, as many would not know what to do next or about their ability to pay for treatment. Concerns over a woman's psychological response to finding out she has cervical cancer were mentioned by some US‐Nai women, US‐Nai men, and US‐Ny men (Q11). In Nyanza, all groups noted that positive results could provoke fear due to the pervasive belief that cancer is not treatable (Q12, Q13).

Stigma.

All groups in Nairobi and Nyanza noted stigma as a barrier, specifically being “talked about,” “judged,” “discriminated against,” or “rejected” by spouses, family members, and their community (Table 3; Q14). Most S‐Nai men mentioned that women who get tested may elect to do so privately for fear of being stigmatized. Most US‐Nai women agreed that some women would elect to be screened outside of their community to avoid scrutiny. Additionally, this group mentioned that cervical cancer screening is for sexually active women and that undergoing screening may indicate that a woman is no longer a virgin (Q15, Q16). Most US‐Nai men mentioned that being screened for cancer might be associated with screening for other, historically feared illnesses, such as HIV/AIDS (Q17).

Lack of Knowledge.

All groups thought that few women get screened because they lack information about (a) cancer and cervical cancer awareness, (b) who gets cancer, (c) signs and symptoms of cancer, and (d) the benefits of screening and what occurs during different screening procedures.

Several themes emerged regarding specific areas in which lack of information could affect the decision to be screened.

Cancer and cervical cancer awareness.

Most US‐Nai women believed that women who do not have general information about cancer or cervical cancer often refuse to get tested in clinical settings.

Who gets cancer.

Participants from Nairobi, in addition to screened women and male partners in Nyanza, reported that some believe only “rich” people get cancer and those considered to be “poor” may not get tested because of low risk perception. In contrast, some Nyanza men also reported that some people in their community believe poor persons are at greater risk for getting cancer. Most US‐Ny men reported that people may lack knowledge about the effect of sex and geographic location on cancer risk. Some US‐Ny and Nairobi men believed that older age was a factor affecting risk. Some US‐Nai women believed that those who travel abroad or are “cursed” may be at risk for getting cancer. Some US‐Nai men mentioned that perceived hereditary risk for cancer may also determine if a woman gets tested.

Signs and symptoms of cancer.

All US‐Nai men agreed that cancer lives inside the body and cannot be seen, so people may not see the importance of getting tested.

Benefits of screening and what occurs during different screening procedures.

Most US‐Nai women and male partners, along with US‐Ny women, conveyed that most people do not know what occurs during the procedure and are unaware of the benefits. Respondents agreed that screening refusal was associated with these factors.

Religious and Cultural Beliefs.

Participants, except for S‐Nai women, reported that certain faith communities, religions, and cultural practices (e.g., those of traditional healers) prohibit people from going to hospitals for care, even if they are sick. Alternatively, they are advised to pray to a higher power or seek care from a traditional healer. Most US‐Ny women and US‐Nai men also mentioned that some faith communities and cultural practices advise against screening of any kind (Table 3; Q18–Q20).

All male participants in Nairobi reported that some cultural and religious beliefs do not allow any person to see or touch a woman's nude body, accept for her husband (as in the case of a doctor during screening). Men also stated having someone see or touch a woman's body during a medical examination or test would be unacceptable for some women who are part of Muslim faith communities.

Difficulty Accessing Screening.

Most participants consistently reported that a lack of time, poor screening availability, transportation difficulties, lack of cost‐effective transportation, long travel times to get to a screening site, and cost were barriers to screening. All female participants in Nairobi and Nyanza reported that time spent away from family and life responsibilities (e.g., work, household chores) (Table 3; Q21), in addition to time spent waiting at a clinic, were barriers to going for screening. Male participants mentioned that not knowing how often women need to get tested, where to go, how long screening takes, or how long it takes women to travel to a screening location were also barriers.

Discussion

This study explored environmental and psychosocial benefits of and barriers to getting a cervical cancer screening from the perspective of women who were previously or never tested and their male partners. This study adds several new perspectives to the research in this area, including examining potential differences in perceptions between those dwelling in urban versus rural areas in Kenya. Investigators found that the perceived benefits and barriers of screening reported by participants in Nyanza versus Nairobi were largely homogeneous.

Although most participants agreed that knowing one's health status and detecting cervical cancer in earlier stages were screening benefits, numerous barriers were reported, some supporting findings from previous studies. These barriers include access to treatment due to cost influencing patients’ decisions to get screened and go for treatment and the lack of awareness about early detection, screening, and where to access screening [5], [6], [7], [8].

Spousal disapproval and women's emotional discomfort were other barriers, documented here, that were consistent with previous studies [8], [9]. One such study found that wives and husbands, perhaps influenced by cultural beliefs, felt uncomfortable about another man, even a doctor, seeing the wife's body. Among unscreened women in this study, 88% did not get tested because they were too “embarrassed” to be examined [8]. In another study, health care workers noted that screening was “too invasive” and viewed as “embarrassing” among women [10]. Other findings on barriers reflected in previous research include marital discord resulting from a woman finding out she has cervical cancer [9] and doctors refusing to screen women without a husband's consent. Related but novel findings include concerns about marital discord and separation for women who received screening without their husband's approval and, among some unmarried women, fear that a partner might refuse to marry them if they get screened, based on suspicion of having cervical cancer.

Age and sex of the medical provider were noted as potential barriers in our study. One previous Kenyan study examined provider characteristics that may serve as screening barriers [11] and noted only education level, ethnicity, and primary language as barriers. Fear of pain and discomfort during and after Pap testing, in addition to a belief that screening could damage a woman's genitals (especially for pregnant women or virgins), were noted by both screened and unscreened women and male partners.

Fears related to receiving positive screening results were considered potential barriers by both men and women. These include not knowing what to do next if found to have cervical cancer; not being able to pay for treatment; psychological effects; and being stigmatized by their spouse, family, and community. Some of these findings are consistent with those from a study of Kenyan leaders and parents, who reported that diseases affecting genital regions of the body can be associated with shame and stigma [9].

Additional findings related to religious and cultural beliefs are reflected in other studies. One study of breast cancer noted that women may rely on traditional healers for several years before seeking screening or medical treatment [12]. Another study examining barriers to using HPV vaccine also noted cultural beliefs as a potential barrier [9].

As research was conducted by KEMRI/CDC, a respected institution in Kenya, responses may have been influenced by social desirability. While the sample size was larger than average for similar studies, results were still based on a relatively small sample. Participants were all from Nairobi and Nyanza; therefore, findings may not be generalizable to other geographic regions of Kenya. Furthermore, because screening is relatively more accessible in these regions, participants’ knowledge about screening may be higher than in other regions of Kenya. Although men and women in our study reported the belief that women generally go for a diagnostic work‐up after symptomatic presentation, we did not formally assess the proportion of women who went for a diagnostic work‐up versus screening for early detection. Additionally, our study did not assess HIV status, which may serve as a limitation to examining the unique characteristics of this population.

Conclusion

Study findings highlight the need for increased informational, educational, and communication (IEC) outreach to residents throughout Kenya before implementing additional screening efforts. Increased IEC efforts should help to raise awareness, prompt demand, and minimize stigma, thus reducing resistance to cervical cancer screening and treatment. However, these efforts should occur only when services are available. Future evaluations examining knowledge, awareness, and acceptability of cervical cancer screening would benefit from including male partners, medical providers, and opinion leaders from other regions of Kenya in which screening and treatment services are available. Although information from these groups is helpful, directly assessing the perceptions of women rather than just requesting information from health clinics is important.

Acceptability and beliefs regarding other screening methods, such as HPV cotesting and self‐collection [14], when they become available, need to be explored. To improve IEC efforts, health systems would benefit from regularly assessing changes in capacity, usage, and perceived barriers to and benefits of screening. Findings from this study, although not directly generalizable to other regions of Kenya or other countries with Kenya‐born immigrant populations, may have implications for communicating about screening with women and their partners. For countries, such as the United States, that have continually growing East African–born immigrant populations [13], the additional understanding about perceived barriers to and benefits of screening noted in our study could be used to inform IEC efforts to increase knowledge and broaden use of cervical cancer preventive services.

Acknowledgments

We thank and acknowledge Ms. Katherine Roland, Dr. Nikki Hawkins, Dr. Eileen Dunne, Ms. Allison Friedman, Dr. Sara Forhan, Dr. Kayla Lasserson, Mr. David Baden, and Dr. Muthoni Gichu for their technical assistance and contributions in proposing the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI)/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Cervical Cancer Assessment Study. We also thank KEMRI staff and contractors who were served as administrators, moderators, note takers, transcribers, and social mobilizers during the KEMRI/CDC Cervical Cancer Assessment Study. These individuals include Mr. Juma Ouma Robert, Ms. Irene Nduku Kioko, Mr. Kennedy Anjejo, Ms. Amondi Cynthia Barbara, Ms. Diana Muushiyi, Ms. Chebchi Khoyi, Mr. Issac Ojino, Mr. Steve Wandiga, Mr. Winston Ajielo, Mr. Frank Odhiambo, Mr. Jonathan Kipchoge, Ms. Joan Lelei, Ms. Faith Maingi‐Githui, and Ms. Cynthia Osanya. We thank Mr. Nicholas Pearson‐Clarke for his editorial assistance on this manuscript.

All authors have read and approved the manuscript as well as any additional information that may affect the review process. This article has not been previously accepted for publication by any other journal or publication source. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC, KEMRI, or Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education. Collection of the data used in this original research was funded by the CDC through KEMRI/CDC/Center for Global Health (CGH)/Office of Director (OD) cooperative agreement number 1U01GH000048‐03. Ms. Ragan's role as a coauthor of this manuscript was also supported, in part, by her appointment to the Research Participation Program at the CDC administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy and the CDC.

Footnotes

For Further Reading: Renicha McCree, Mary Rose Giattas, Vikrant V. Sahasrabuddhe et al. Expanding Cervical Cancer Screening and Treatment in Tanzania: Stakeholders' Perceptions of Structural Influences on Scale‐Up. The Oncologist 2015;20:621‐626.

Implications for Practice: Tanzanian women have a high burden of cervical cancer. Understanding the perceived structural factors that may influence screening coverage for cervical cancer and availability of treatment may be beneficial for program scale‐up. This study showed that multiple factors contribute to the challenge of cervical cancer screening and treatment in Tanzania. In addition, it highlighted systematic developments aimed at expanding services. This study is important because the themes that emerged from the results may help inform programs that plan to improve screening and treatment in Tanzania and potentially in other areas with high burdens of cervical cancer.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Natasha Buchanan Lunsford, Judith Lee Smith, Mona Saraiya

Provision of study material or patients: Natasha Buchanan Lunsford, Judith Lee Smith, Mona Saraiya

Collection and/or assembly of data: Millicent Aketch

Data analysis and interpretation: Natasha Buchanan Lunsford, Kathleen Ragan, Millicent Aketch

Manuscript writing: Natasha Buchanan Lunsford, Kathleen Ragan, Judith Lee Smith, Mona Saraiya, Millicent Aketch

Final approval of manuscript: Natasha Buchanan Lunsford, Kathleen Ragan, Judith Lee Smith, Mona Saraiya, Millicent Aketch

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

References

- 1. Korir A, Okerosi N, Ronoh V et al. Incidence of cancer in Nairobi, Kenya (2004‐2008). Int J Cancer 2015;137:2053–2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M et al. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC Cancer Base No.11. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013. Available at: http://globocan.iarc.fr. Accessed January 8, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kenya Ministry of Health . National Cervical Cancer Prevention Program: Strategic Plan, 2012‐2015. Kidul NA, technical editor. Nairobi, Kenya: ACCESS Uzima Program; 2011. Available at: http://www.iedea-ea.org/joomla/attachments/article/304/National%20Cervical%20Cancer%20Prevention%20Plan%20FINALFeb%202012.pdf. Accessed January 8, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Harry B, Sturges K, Klinger J. Mapping the process: An exemplar of process and challenge in grounded theory analysis. Educ Res 2005;34:3–13. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Maranga IO, Hampson L, Oliver AW et al. Analysis of factors contributing to the low survival of cervical cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy in Kenya. PLoS One 2013;8:e78411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gichangi P, Estambale B, Bwayo J et al. Knowledge and practice about cervical cancer and Pap smear testing among patients at Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2003;13:827–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Machoki JM, Rogo KO. Knowledge and attitudinal study of Kenyan women in relation to cervical carcinoma. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1991;34:55–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gatune JW, Nyamongo IK. An ethnographic study of cervical cancer among women in rural Kenya: Is there a folk causal model? Int J Gynecol Cancer 2005;15:1049–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Friedman AL, Oruko KO, Hable MA et al. Preparing for human papillomavirus vaccine introduction in Kenya: Implications from focus‐group and interview discussions with caregivers and opinion leaders in Western Kenya. BMC Public Health 2014;14:855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kivuti‐Bitok LW, Pokhariyal GP, Abdul R et al. An exploration of opportunities and challenges facing cervical cancer managers in Kenya. BMC Res Notes 2013;6:136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Miller AN, Kinya J, Booker N et al. Kenyan patients' attitudes regarding doctor ethnicity and doctor‐patient ethnic discordance. Patient Educ Couns 2011;82:201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Muthoni A, Miller AN. An exploration of rural and urban Kenyan women's knowledge and attitudes regarding breast cancer and breast cancer early detection measures. Health Care Women Int 2010;31:801–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Immigration Council. African Immigrants in America: A Demographic Overview. 2012 . Available at: https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/sites/default/files/research/african_immigrants_in_america_a_demographic_overview.pdf.

- 14.World Health Organization . WHO guidelines for screening and treatment of precancerous lesions for cervical cancer prevention: supplemental material: GRADE evidence-torecommendation tables and evidence profiles for each recommendation. 2013. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/94830/1/9789241548694_eng.pdf. Accessed on November 28, 2016.