Abstract

Background and Aims

Adiponectin, an adipose-secreted protein that has been linked to insulin sensitivity, plasma lipids, and inflammatory patterns, is an established biomarker for metabolic health. Despite clinical relevance and high heritability, the determinants of plasma adiponectin levels remain poorly understood.

Methods and Results

We conducted the first epigenome-wide cross-sectional study of adiponectin levels using methylation data on 368,051 cytosine-phosphate-guanine (CpG) sites in CD4+ T-cells from the Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network (GOLDN, n= 991). We fit linear mixed models, adjusting for age, sex, study site, T-cell purity, and family. We have identified a positive association (regression coefficient ± SE= 0.01 ± 0.001, P=3.4x10−13) between plasma adiponectin levels and methylation of a CpG site in CPT1A, a key player in fatty acid metabolism. The association was replicated (n=474, P=0.0009) in whole blood samples from the Amish participants of the Heredity and Phenotype Intervention (HAPI) Heart Study as well as White (n=592, P=0.0005) but not Black (n=243, P=0.18) participants of the Bogalusa Heart Study (BHS). The association remained significant upon adjusting for BMI and smoking in GOLDN and HAPI but not BHS. We also identified associations between methylation loci in RNF145 and UFM1 and plasma adiponectin in GOLDN and White BHS participants, although the association was not robust to adjustment for BMI or smoking.

Conclusion

We have identified and replicated associations between several biologically plausible loci and plasma adiponectin. These findings support the importance of epigenetic processes in metabolic traits, laying the groundwork for future translational applications.

Keywords: epigenetics, methylation, adiponectin, epidemiology

Introduction

Adiponectin is an adipocyte-derived secretory protein with generally positive, multi-pronged effects on metabolic health (1). Levels of circulating adiponectin in the plasma are heritable (h2=55.1%) (2) and widely used as a biomarker for cardiovascular and metabolic risk. Despite clinical relevance and high heritability, the genetic determinants of plasma adiponectin remain poorly understood, with the known genetic polymorphisms accounting for only a modest fraction of inter-individual variability (3). An emerging body of evidence suggests that epigenetic changes such as DNA methylation may contribute to the “missing heritability” and merit further evaluation as risk factors for metabolic disease (4). However, prior epigenetic investigations into the adiponectin pathway were largely limited in scope and/or sample size, focusing on candidate regions rather than epigenome-wide variation. The advent of high-throughput array-based methods has enabled a comprehensive approach to quantifying epigenetic variation, promising new insights into the relationship between DNA methylation and complex traits such as circulating adiponectin.

Using DNA isolated from CD4+ T-cells from 991 European American participants of the Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network (GOLDN), we have performed the first cross-sectional epigenome-wide study (EWAS) of plasma adiponectin. We subsequently replicated our top finding in two external populations, using whole blood samples from the Heredity and Phenotype Interaction (HAPI) Heart Study (n=474) and the Bogalusa Heart Study (BHS, n=835). We further conducted sensitivity analyses to account for the potential role of obesity, smoking, and alcohol in the relationship between DNA methylation and circulating adiponectin. Finally, we have examined methylation variation in regions reported to be associated with circulating adiponectin in prior genetic studies to provide a more comprehensive view of heritable determinants of cardiometabolic health.

Methods

Study Populations

Discovery

The GOLDN study population, previously described in detail (5–8), was comprised of European American families with at least two siblings, recruited from the participants of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Family Heart Study in Minneapolis and Salt Lake City. Before each study visit, participants abstained from eating for 8 hours, drinking alcohol for 24 hours, and using other lipid-lowering medications for 4 weeks. The Institutional Review Boards at the University of Minnesota, University of Utah, and Tufts University/New England Medical Center approved the study protocol, and all participants provided informed consent.

Replication

BHS is a long-term community-based study of cardiovascular risk factors in a biracial (Black/White) rural community in Louisiana (11). Participants provided informed consent, while the study design and procedures as well as consent forms were approved by Institutional Review Boards from Louisiana State University and Tulane University Medical Center.

The HAPI Heart Study (n=868) is a community-based study of cardiovascular risk carried out in the Amish community from Lancaster County, Pennsylvania (9). Virtually all participants have descended from approximately 200 founders of the Old Order Amish community (10). The study was approved by the appropriate Institutional Review Boards and monitored by an external Data Safety Monitoring Board.

DNA Methylation Measurements

GOLDN

Procedures for quantifying DNA methylation in GOLDN have been extensively described in previous publications (12, 13). Briefly, we restricted our analyses to CD4+ T-cells, isolated from peripheral blood frozen buffy coat samples, to reduce confounding by cell type. Upon isolating DNA using the DNeasy Kits (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands), we used the Infinium Human Methylation 450 Beadchip (Illumina, San Diego, CA) to measure genome-wide DNA methylation (12). Subsequently, we estimated β scores, defined as the proportion of total signal from the methylation-specific probe or color channel, and detection p-values, defined as the probability that the total intensity for a given probe falls within the background signal intensity, using the GenomeStudio software provided by the manufacturer. For reasons of quality control, we did not analyze any β scores with an associated detection p-value greater than 0.01, samples with more than 1.5% missing data points across ~470,000 autosomal CpGs, or probes where 10% of samples or more failed to yield adequate intensity (12). After filtering, we normalized the resulting β scores using the ComBat package for R software in non-parametric mode to account for batch effects (14). Normalization for probes from the Infinium I and II chemistries was done separately, with subsequent adjustment of the Infinium II scores as previously described (12). As the final quality control step, we identified and removed cross-reactive probes (12) and CpGs sites with SNPs on the probe as reported by Barfield et al (15). A total of 991 samples and 368,051 CpG sites remained in the analysis.

HAPI Heart Study

For the replication study, we extracted DNA from whole blood collected in acid citrate dextrose tubes (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ) using the Gentra Puregene kit (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands). According to the manufacturer’s protocol, we treated 1μg of genomic DNA with bisulfite using the Epitect Fast 96 DNA bisulfite kit (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands). We obtained PyroMark CpG assays (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands) to quantify methylation on the top finding from GOLDN, located at CpG site cg00574958. To that end, we amplified 1 μl of bisulfite converted DNA using the PyroMark PCR kit (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands) with the supplied parameters. We determined PCR success by gel electrophoresis in 1.75% agarose gel. We performed pyrosequencing on 10μl of PCR product using sequencing primer GTTGGTTTGGGGATTATTA and the GTATTYGTAGTTGGTTTTTTGGATTGGTTTTG sequence to analyze. We successfully pyrosequenced a total of 726 samples. Of those, 543 samples had PCR reactions carried out in duplicate on two different machines, with the remaining 183 samples analyzed only on a single machine. The methylation measures utilized in the analysis correspond to samples with duplicate measures, using the average of the two methylation values. We additionally assessed the reproducibility of methylation measurements in the paired samples and removed observations for whom the coefficient of variation exceeded 20%, leaving 474 participants for the final analysis.

BHS

We extracted genomic DNA from 835 whole blood samples using the PureLink Pro 96 Genomic DNA Kit (LifeTechnology, CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Identically to GOLDN, we used the Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip to quantify DNA methylation. All the DNA samples were processed at the Microarray Core Facility, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, Texas. The image was acquired with HiScan scanner and analyzed with GenomeStudio software. The call rates for all samples across all CpG sites exceeded 99.8%. We used the latest version (1.2) of the Illumina Human Methylation 450k annotation in the current study to get the corresponding location information. Similarly to GOLDN, we converted DNA methylation levels at CpG sites into β scores (analogous to the proportion of DNA methylated), a continuous variable between 0 (unmethylated) and 1 (fully methylated). We normalized the data using the R package watermelon (16). For correction of systematic technical biases in the 450K assay, we normalized β scores using the dasen function, in which type I and type II intensities and methylated and unmethylated intensities are quantile-normalized separately after backgrounds equalization of type I and type II probes. Based on bead count and detection p-values, we set the following thresholds for removal: 1) samples having 1% of CpG sites with a detection p-value greater than 0.05; 2) probes having 5% of samples with a detection p-value greater than 0.05; 3) probes with bead count less than 3 in 5% of samples.

Adiponectin Measurements

As described in a prior GOLDN publication (17), we assayed plasma adiponectin using an ELISA kit from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). We centrifuged all samples at 2000 x g for 15 minutes at 4 degrees Celsius within 20 minutes of collection, stored them frozen at −70 degrees C, and analyzed at the same time to eliminate batch effects. The reliability coefficient was estimated at 0.95 (17). Both HAPI Heart Study and BHS measured adiponectin levels using a commercial radioimmunoassay kit (Linco Research, St Charles, MO). Adiponectin data were available on 474 HAPI Heart participants and 835 BHS participants with DNA methylation data that passed quality control exclusions as described above.

Statistical Methods

The statistical methods for discovery and replication are summarized in Supplemental Table 1. Specifically, in all three populations we used linear mixed models to evaluate the association between plasma adiponectin (exposure) and DNA methylation β scores (outcome). To limit the undue influence of the skewed the adiponectin distribution on the regression coefficient estimates, we have ln-transformed it in all three populations.

Discovery

In GOLDN, we used linear mixed models to test for associations between methylation scores at each CpG site and ln-transformed plasma adiponectin adjusting for age, sex, study site, and the first 4 principal components generated to capture T-cell purity as fixed effects, and family as a random effect. We conducted sensitivity analyses additionally adjusting for body mass index (BMI), smoking, and alcohol to account for potential confounding. We constructed Manhattan plots to visualize the results.

Replication

We sought replication of all top hits (false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.2) from GOLDN in the BHS cohort, which had extant methylation data available. Because the HAPI Heart cohort did not have array measurements of methylation and instead performed de novo pyrosequencing, we limited that replication effort to the top GOLDN CpG (FDR < 0.05). In BHS, we fit linear mixed models adjusted for age, sex, and white blood cell differential cell counts (CD8T, CD4T, NK, B cells, monocytes, and granulocytes) as fixed effects and batch as a random effect. BHS analyses were stratified by race. The replication analysis in BHS used α=0.05/number of CpGs with FDR < 0.2 in GOLDN= 0.05/34= 0.001. For the GOLDN hits that successfully replicated in at least one racial subgroup of BHS, we fit additional models including 1) BMI and 2) smoking and alcohol intake as sensitivity analyses.

In HAPI Heart, the models adjusted for age, sex, and batch as fixed effects as well as accounted for the family structure by including the relationship matrix as a random effect. We fit additional models with BMI and smoking as covariates to examine robustness of the finding. Because only one CpG locus was tested in HAPI Heart, this replication analysis used α=0.05 as the significance threshold.

Although the discovery analysis did not include batch as a covariate because its effects were removed during the normalization phase using ComBat, we did account for batch in statistical models fit to the replication cohorts. Results from all three studies were meta-analyzed using Fisher’s method (18), which makes no assumptions about individual effect sizes, as the estimates of effect were not directly comparable due to differences in cell types and modeling approaches.

Integration

In light of the evidence linking sequence variation to epigenetic patterns, we have attempted integrating signals from prior genome-wide linkage and association studies of adiponectin in GOLDN with the epigenetic data. Specifically, we have performed look-up of methylation variants located in or near (+/−50 bp) the genes previously identified as implicated in adiponectin homeostasis in our study population: ADIPOQ, CDH13, IL22RA1, IL28RA, PCSK5, SCUBE1, and TMEM18, as well as intergenic variants on chromosomes 12 and 20 (7, 17). We also interrogated methylation in the following adiponectin-related genes identified in two or more populations in the GWAS catalog: ARL15, CMIP, FER, GPR109A, and PEPD (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/search?query=Adiponectinlevels). To conduct the lookup, we obtained regression coefficients and P-values for each CpG located in or near (+/−50 bp) the aforementioned candidate genes in the epigenome-wide study results from the discovery cohort (GOLDN).

Results

Table 1 summarizes the general characteristics of the study populations. Mean adiponectin concentrations were the highest among Amish participants and lowest among Black BHS participants; the inverse pattern was observed for BMI. On average, study participants were overweight but not obese.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study populations.

| GOLDN (n=991) | HAPI (n=474) | BHS White (n=592) | BHS Black (n=243) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years* | 49 ± 16 | 44 ± 14 | 43 ± 5 | 43 ± 5 |

| Sex, n female (%) | 518 (52) | 221 (47) | 318 (54) | 157 (65) |

| Plasma adiponectin, μg/dL | 8.3 ± 4.7 | 11.3 ± 5.9 | 8.9 ± 4.2 | 7.5 ± 4.0 |

| Current smokers, n (%) | 73 (7) | 51 (11) | 151 (26) | 74 (30) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28.3 ± 5.7 | 26.6 ± 4.4 | 28.6 ± 6.3 | 31.6 ± 8.3 |

Values for continuous variables are shown as mean or median ± SE.

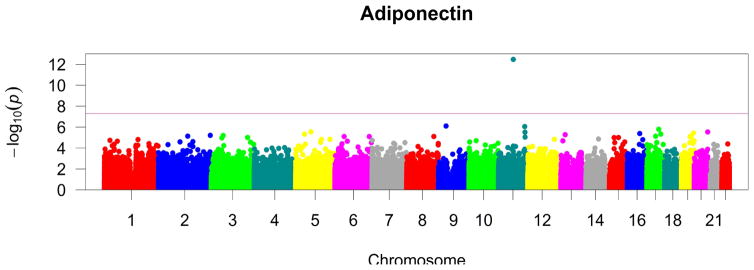

We identified one locus in the first intron of CPT1A that was methylated in a direct correlation with plasma adiponectin (i.e. individuals with higher plasma adiponectin levels had higher methylation scores at this CpG site). In addition to the CPT1A locus, there were suggestive associations (FDR < 0.20) for CpG sites in FAM166B, SORL1, RNF145, UFM1, and ASAM genes, among others. Table 2 shows the location, strength of association, and annotation for the top hits while Figure 1 summarizes epigenome-wide results. Upon adjustment for BMI (Table 3), the association with the CPT1A locus diminished but remained statistically significant; however, the association estimates for other loci weakened substantially, yielding only two CpGs with FDR < 0.20. In the models that adjusted for current smoking status or alcohol intake (Supplemental Table 2), the estimate of effect did not appreciably change compared with the baseline model.

Table 2.

Top CpG methylation sites associated* with plasma adiponectin in GOLDN (n=991) (false discovery rate <0.2) and corresponding estimates of association from the replication analysis** in BHS (White n=592, Black n=243). Associations with CpGs that successfully replicated in at least one BHS racial group (P<0.05/34= 0.001) are in bold.

| GOLDN | BHS White | BHS Black | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||

| Marker | Chromosome | Region | Gene | Regression Coefficient ± SE | P-value | Regression Coefficient ± SE | P-value | Regression Coefficient ± SE | P-value |

| cg00574958 | 11 | North shore | CPT1A | 0.01 ± 0.001 | 3.4x10−13 | 0.006 ± 0.001 | 0.0005 | 0.0006 ± 0.003 | 0.18 |

| cg21212076 | 9 | -- | FAM166B | −0.02 ± 0.003 | 7.8x10−7 | −0.002 ± 0.004 | 0.61 | 0.001 ± 0.005 | 0.85 |

| cg22964469 | 11 | -- | SORL1 | 0.007 ± 0.001 | 8.8x10−7 | 0.0009 ± 0.002 | 0.56 | 0.004 ± 0.002 | 0.01 |

| cg14266156 | 17 | -- | Intergenic | 0.007 ± 0.001 | 1.6x10−6 | −0.0004 ± 0.002 | 0.78 | −0.002 ± 0.003 | 0.56 |

| cg19828789 | 5 | -- | Intergenic | −0.008 ± 0.002 | 2.8x10−6 | 0.0003 ± 0.002 | 0.84 | −0.0008 ± 0.002 | 0.66 |

| cg05358404 | 20 | Island | RTEL1 | 0.02 ± 0.003 | 2.9x10−6 | 0.006 ± 0.004 | 0.21 | −0.0002 ± 0.005 | 0.96 |

| cg05931265 | 11 | South shore | UBASH3B | 0.006 ± 0.001 | 3.0x10−6 | −0.0004 ± 0.002 | 0.86 | −0.006 ± 0.003 | 0.05 |

| cg19393762 | 19 | -- | TNNT1 | −0.009 ± 0.002 | 3.6x10−6 | −0.002 ± 0.002 | 0.34 | −0.0002 ± 0.003 | 0.95 |

| cg07895124 | 16 | -- | GPR114 | −0.008 ± 0.002 | 4.1x10−6 | −0.0004 ± 0.002 | 0.81 | −0.0003 ± 0.003 | 0.89 |

| cg25649039 | 17 | -- | PRKCA | −0.01 ± 0.002 | 4.6x10−6 | −0.002 ± 0.002 | 0.47 | −0.004 ± 0.003 | 0.24 |

| cg24787076 | 5 | North shore | RPL37 | 0.004 ± 0.0009 | 4.7x10−6 | 0.002 ± 0.001 | 0.09 | 0.003 ± 0.002 | 0.09 |

| cg19750657 | 13 | -- | UFM1 | −0.008 ± 0.002 | 5.2x10−6 | −0.01 ± 0.003 | 0.0002 | 0.003 ± 0.006 | 0.66 |

| cg05879734 | 2 | -- | Intergenic | 0.003 ± 0.0007 | 6.1x10−6 | 0.002 ± 0.001 | 0.12 | 0.005 ± 0.002 | 0.02 |

| cg26797723 | 3 | Island | WNT5A | −0.004 ± 0.001 | 6.3x10−6 | 0.0005 ± 0.0006 | 0.46 | −0.003 ± 0.001 | 0.008 |

| cg18810022 | 2 | -- | Intergenic | 0.008 ± 0.002 | 5.4x10−6 | 0.0008 ± 0.002 | 0.60 | −0.0002 ± 0.002 | 0.93 |

| cg26985149 | 17 | Island | Intergenic | 0.005 ± 0.001 | 7.4x10−6 | −0.002 ± 0.002 | 0.34 | 0.0002 ± 0.003 | 0.94 |

| cg06710295 | 8 | Island | MTSS1 | 0.002 ± 0.0005 | 7.8x10−6 | 0.0001 ± 0.001 | 0.89 | 0.0004 ± 0.001 | 0.74 |

| cg16597079 | 6 | -- | TRERF1 | 0.006 ± 0.001 | 7.9x10−6 | −0.0001 ± 0.001 | 0.92 | 0.002 ± 0.002 | 0.23 |

| cg11552078 | 19 | South shore | TIMM50 | 0.005 ± 0.001 | 7.9x10−6 | 0.001 ± 0.002 | 0.62 | −0.006 ± 0.003 | 0.03 |

| cg18758976 | 6 | -- | SYNJ2 | 0.007 ± 0.002 | 7.9x10−6 | −0.001 ± 0.001 | 0.36 | −0.0003 ± 0.002 | 0.88 |

| cg18244544 | 19 | North shore | ZNF224 | 0.002 ± 0.0004 | 8.9x10−6 | 0.0003 ± 0.001 | 0.70 | 0.0009 ± 0.001 | 0.36 |

| cg26894079 | 11 | -- | ASAM | 0.01 ± 0.002 | 9.0x10−6 | 0.006 ± 0.003 | 0.02 | 0.006 ± 0.004 | 0.14 |

| cg18098839 | 3 | -- | GOLIM4 | 0.004 ± 0.001 | 9.7x10−6 | 0.005 ± 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.002 ± 0.003 | 0.44 |

| cg00325866 | 15 | North shore | C2CD4A | 0.001 ± 0.0002 | 9.9x10−6 | −0.0004 ± 0.0005 | 0.45 | −0.0006 ± 0.0007 | 0.37 |

| cg15183258 | 15 | -- | MGA | −0.02 ± 0.004 | 1.0x10−5 | −0.001 ± 0.003 | 0.62 | 0.001 ± 0.004 | 0.77 |

| cg14652230 | 3 | North shore | NICN1 | 0.002 ± 0.0005 | 1.1x10−5 | −0.0006 ± 0.0008 | 0.46 | 0.001 ± 0.001 | 0.41 |

| cg09251317 | 14 | -- | Intergenic | 0.008 ± 0.002 | 1.4x10−5 | −0.0004 ± 0.002 | 0.80 | 0.007 ± 0.003 | 0.01 |

| cg26403843 | 5 | North shelf | RNF145 | −0.008 ± 0.002 | 1.5x10−5 | −0.02 ± 0.004 | 0.0004 | −0.01 ± 0.006 | 0.04 |

| cg08775774 | 12 | -- | CCDC62 | 0.002 ± 0.0004 | 1.5x10−5 | −0.0005 ± 0.0006 | 0.47 | −0.0002 ± 0.0008 | 0.83 |

| cg17593721 | 5 | South shore | HSD17B4 | 0.003 ± 0.0007 | 1.5x10−5 | 0.0004 ± 0.001 | 0.73 | −0.003 ± 0.002 | 0.09 |

| cg23923820 | 1 | South shore | PKLR | −0.01 ± 0.002 | 1.5x10−5 | −0.0004 ± 0.002 | 0.85 | −0.003 ± 0.004 | 0.41 |

| cg05466767 | 16 | North shelf | FTSJD1 | 0.005 ± 0.001 | 1.6x10−5 | −0.0009 ± 0.0007 | 0.18 | −0.002 ± 0.001 | 0.58 |

| cg19595760 | 1 | South shelf | MAN1C1 | 0.009 ± 0.002 | 1.8x10−5 | 0.001 ± 0.002 | 0.63 | −0.0008 ± 0.003 | 0.82 |

| cg14584616 | 7 | North shelf | HEATR2 | −0.008 ± 0.002 | 1.8x10−5 | 0.0001 ± 0.001 | 0.91 | −0.001 ± 0.002 | 0.58 |

Association estimates in GOLDN were obtained from linear mixed models with ln-transformed adiponectin as a predictor and methylation β score as the outcome, adjusted for age, sex, study site, T-cell purity principal components (fixed effects) and family relatedness (random effect).

Association estimates in BHS were obtained from linear mixed models with ln-transformed adiponectin as a predictor and methylation β score as the outcome, adjusted for age, sex, white blood cell counts (fixed effects) and batch (random effect).

Figure 1. Epigenome-wide associations of CpG methylation with plasma adiponectin in GOLDN (n=991).

Manhattan plot of epigenome-wide results of testing for association between methylation at 368,051 CpG sites and plasma adiponectin. The X-axis displays the chromosome on which the site is located, the Y-axes display −log10(P-value). The red horizontal line indicates the threshold for epigenome-wide statistical significance after a Bonferroni correction (P-value < 0.05/368,051= 1.4x10−7).

Table 3.

Top CpG methylation sites associated* with plasma adiponectin (false discovery rate <0.2) in the discovery population (n=991), adjusted for body mass index.

| Marker | Chromosome | Region | Gene | Regression Coefficient ± SE | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cg00574958 | 11 | North shore | CPT1A | 0.008 ± 0.001 | 1.9x10−8 |

| cg24787076 | 5 | North shore | RPL37 | 0.005 ± 0.0009 | 2.3x10−7 |

Association estimates were obtained from linear mixed models with ln-transformed adiponectin as a predictor and methylation β score as the outcome, adjusted for age, sex, BMI, study site, T-cell purity principal components (fixed effects) and family relatedness (random effect).

Out of the 34 CpGs that were tested for replication in BHS, only 3 reached statistical significance in the White subset upon adjusting for multiple testing: cg00574958 in CPT1A, cg19750657 in UFM1, and cg26403843 in RNF145 (Table 2), whereas none were significant in the smaller Black subsample. Adjustment for either BMI or smoking attenuated the observed association with both loci in the BHS White participants, rendering them no longer statistically significant (cg00574958: P= 0.14 and 0.15, cg19750657: P= 0.01 and 0.02, cg26403843: P=0.005 and 0.006 when adjusted for BMI and smoking plus alcohol, respectively).

Subsequently, the association with CPT1A locus was confirmed in the HAPI Heart study (Table 4). In the 474 participants of the HAPI Heart study, ln-transformed adiponectin levels were significantly and positively associated with cg00574958 methylation, similarly to GOLDN and BHS. The difference in the magnitude of the regression coefficients between HAPI Heart analyses and the other two cohorts could potentially be explained by different methylation measuring techniques (array vs. pyrosequencing). In HAPI Heart participants, the association diminished but remained significant upon adjustment for BMI (Table 4). Adjusting for smoking had a similar effect in HAPI Heart (Table 4). The association between methylation at the CPT1A locus and circulating adiponectin in the meta-analysis of all 2300 participants was highly significant: P=4.4x10−16.

Table 4.

Associations between the methylation of the cg00574958 locus in CPT1A in the discovery and replication cohorts.

| Basic model* | Basic model* + BMI | Basic model* + smoking + alcohol** | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| Cohort | N | Regression Coefficient ± SE | P-value | Regression Coefficient ± SE | P-value | Regression Coefficient ± SE | P-value |

| GOLDN | 991 | 0.01 ± 0.001 | 3.4x10−13 | 0.008 ± 0.001 | 1.9x10−8 | 0.01 ± 0.001 | 7.4x10−14 |

| HAPI Heart | 474 | 0.88 ± 0.26 | 0.0009 | 0.61 ± 0.28 | 0.03 | 0.60 ± 0.27 | 0.03 |

| BHS (White) | 592 | 0.006 ± 0.002 | 0.0005 | 0.002 ± 0.002 | 0.14 | 0.002 ± 0.002 | 0.15 |

| BHS (Black) | 243 | 0.003 ± 0.002 | 0.18 | 0.0006 ± 0.003 | 0.79 | 0.0008 ± 0.003 | 0.74 |

Basic model refers to a linear mixed model with ln-transformed adiponectin as a predictor and methylation β score as the outcome, adjusted for age, sex, technical covariates (in GOLDN: study site and T-cell purity principal components; in HAPI Heart: batch; in BHS: white blood cell counts and batch), and family relatedness (only in GOLDN and HAPI Heart).

Alcohol intake data was not available in HAPI Heart but is likely to be minimal due to religious restrictions; therefore, the association estimates for HAPI Heart in this column are derived from basic model + smoking.

Among genes harboring known sequence variants associated with circulating adiponectin, none contained epigenome-wide significant (FDR < 0.20) methylation hits. The top locus among such candidate genes (regression coefficient (SE)= −0.003 (0.0008), P=0.003) maps to CDH13 on chromosome 16.

Discussion

The evidence in support of epigenetic regulation of complex traits such as plasma adiponectin is growing at a fast pace. However, prior to our study, investigations of epigenetic determinants of adipocytokines were limited to candidate gene analyses, usually involving the adiponectin gene itself (ADIPOQ) or its receptor (ADIPOR1), or other candidate genes such as CDH13 (19–21). The advent of high-resolution arrays enabled epigenome-wide profiling and discovery of novel loci such as the one we identified and successfully replicated in CPT1A, UFM1, and RNF145. It is highly likely that the observed association between all three loci and adiponectin levels are related to obesity, as evidenced by the results of our sensitivity analyses.

The differentially methylated locus identified and replicated in our study is located in the first intron of CPT1A, which encodes carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A, the rate-limiting enzyme for mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation. Prior studies—including several from GOLDN—have linked methylation of CPT1A to 1) reduced expression of CPT1A and 2) obesity indices, plasma triglycerides, very low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and metabolic syndrome, highlighting the biological relevance of the observed association (6, 13, 22). Specifically, the study linking CPT1A methylation to circulating lipids also provided functional annotation data, illustrating the regulatory potential of the top CpG site: in addition to several transcription factor binding sites, our top locus is also adjacent (upstream) to an active promoter region, and overlaps an H3K27Ac histone mark (6). Interestingly, prior analyses of the GOLDN data (6) do not report significant sequence variant effects (methylation quantitative trait loci) in that region. Other groups have found hepatic expression of CPT1A to be correlated with the amount of liver fat, and the correlation decreased when adjusted for BMI (23). In the GOLDN and HAPI studies, adjustment for BMI similarly, albeit incompletely, attenuated the estimate of CPT1A effect. In contrast, the association between CPT1A and plasma adiponectin was not observed at all among Black participants from BHS, and was eliminated completely upon adjustment for BMI among White participants. Considering the small size of the Black sample, this may represent limitations of statistical power rather than true effect modification by race; in fact, CPT1A methylation was confirmed to be associated with BMI in a much larger African American sample from the Artherosclerosis Risk in Communities study (13).

Previously published evidence shows that the relationship between epigenomic variation, obesity, and adiponectin is likely to be complex and multidirectional. For example, in a recent animal study, obesity has been shown to mediate insulin resistance by inducing hypermethylation of the adiponectin gene (4), while in a small-scale human trial both obesity and insulin resistance actually diminished methylation of both leptin and adiponectin promoters (24). It is noteworthy that methylation of ADIPOQ or any other known adiponectin loci was associated with neither obesity (13) nor insulin resistance (25) nor adiponectin in GOLDN, suggesting alternative pathways of epigenetic regulation.

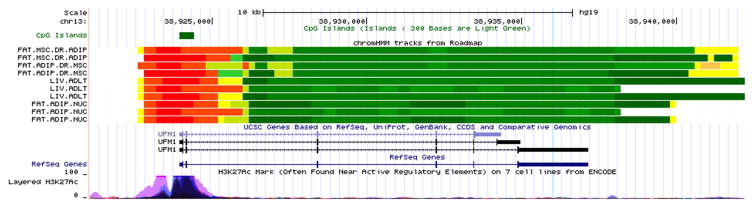

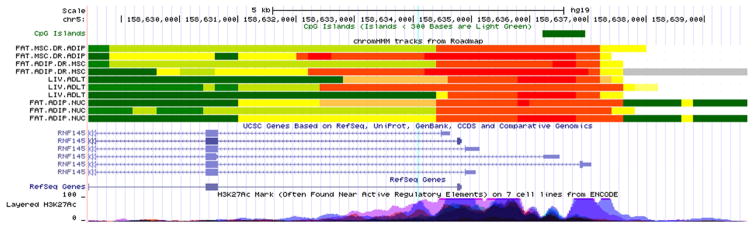

In addition to the CPT1A locus, we have identified and replicated associations with CpG sites located in UFM1 and RNF145. The cg19750657 locus is located in the 3’ UTR region of UFM1 (ubiquitin-fold modifier 1), which encodes a highly conserved posttranslational modifier involved in endoplasmic reticulum functions and other cellular processes (26). Specifically, it is highly expressed in pancreatic islets and upregulated in type 2 diabetes, representing a protective response to endoplasmic reticulum stress (27). The cg19750657 site in particular has been shown to be hypermethylated in adipose tissue in the setting of type 2 diabetes (28), consistent with our observed inverse association with plasma adiponectin. Although its location in the 3’ UTR region (Figure 2) makes it an unlikely candidate for influencing expression, prior studies show that methylation of the untranslated regions may exert other forms of epigenetic control, notably transcription elongation (29). Related to the ubiquitin pathway represented by our UFM1 finding is the ring zinger protein encoded by RNF145, which includes the other replicated methylation locus. Namely, it regulates an ubiquitin-cycling node in the oxidative burst response and is involved in endopasmic reticulum-associated degradation (30). Notably, methylation of cg26403843 in RNF145 has been previously linked to BMI and waist circumference in several diverse populations (31, 32). Additionally, the cg26403843 site colocalizes with an H3K27Ac histone mark in immune cells from the ENCODE data, suggesting an active regulatory element (Figure 3). However, despite successful replication across cohorts, these findings need to be interpreted with caution because the strength of the association was attenuated upon adjustment for either BMI or smoking + alcohol, indicating potential influence of known epigenetic confounders.

Figure 2. ENCODE/Roadmap Epigenomics Project annotation of the genomic region containing the UFM1 methylation locus.

Functional annotation of the genomic region containing the UFM1 (Figure 2) and RNF145 (Figure 3) methylation loci on chromosomes 13 and 5 respectively, generated using data from the ENCODE/Roadmap Epigenomics Project. Functional features are listed on the Y- axis, while the X-axis represents the genomic position (hg19, Human Genome Build 37). Notable features include (from top to bottom): CpG islands, chromatin state across tissues physiologically relevant to adiponectin regulation (adipose and hepatic), known genes, layered H3K27Ac marks commonly found near active regulatory elements. The location of the CpG is marked by the faint blue vertical line.

Figure 3. ENCODE/Roadmap Epigenomics Project annotation of the genomic region containing the RNF145 methylation locus.

Functional annotation of the genomic region containing the UFM1 (Figure 2) and RNF145 (Figure 3) methylation loci on chromosomes 13 and 5 respectively, generated using data from the ENCODE/Roadmap Epigenomics Project. Functional features are listed on the Y- axis, while the X-axis represents the genomic position (hg19, Human Genome Build 37). Notable features include (from top to bottom): CpG islands, chromatin state across tissues physiologically relevant to adiponectin regulation (adipose and hepatic), known genes, layered H3K27Ac marks commonly found near active regulatory elements. The location of the CpG is marked by the faint blue vertical line.

Like most population-based studies of epigenetic patterns published to date, our study is cross-sectional and restricted to blood samples. We argue that the use of CD4+ T cells (discovery cohort) as well as whole blood samples (replication) represent a strength rather than a weakness of our study, as these are easily accessible tissues with high translational potential. Importantly, a previous study has reported high correlation of DNA methylation levels at biologically relevant (with regard to leptin and adiponectin regulation) CpGs between blood and adipose tissue (both visceral and subcutaneous), corroborating the validity of our strategy (33). To account for the dynamic nature of epigenetic processes, our findings would best be followed up by investigating links between gene methylation/expression and adipocytokines in a longitudinal setting to control for reverse causation. Additionally, future studies would benefit from attempting validation of our preliminary findings of other adiponectin-related methylation loci, furthering current understanding of the genetic architecture of circulating adiponectin.

In summary, we have conducted the first epigenome-wide study of circulating adiponectin levels. We have shown that methylation of a CpG site in CPT1A is associated with circulating adiponectin levels, likely in an obesity-dependent manner, in three population-based adult cohorts of European descent. Our findings enhance current understanding of genetic architecture of plasma adiponectin levels and lay the groundwork for testing CPT1A methylation as a novel pleiotropic marker of chronic disease risk.

Supplementary Material

We conducted the first epigenome-wide study of plasma adiponectin (total N=2,300)

34 methylation loci suggested association (FDR <0.2) with plasma adiponectin in the GOLDN cohort

Associations with loci in CPT1A, UFM1, and RNF145 were replicated in individuals of European but not African descent; adjustment for BMI attenuated the observed associations

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, grant U01HL072524-04. The Amish HAPI Heart Study was supported by NIH grants U01HL072515 and P30DK072488. The BHS was supported by grants 5R01ES021724 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and 2R01AG016592 from the National Institute on Aging. Shengxu Li is partly supported by grant 13SDG14650068 from American Heart Association.

Editorial Assistance: We thank Kate Sreenan from the University of Alabama at Birmingham for help in preparation and formatting of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Turer AT, Scherer PE. Adiponectin: mechanistic insights and clinical implications. Diabetologia. 2012;55(9):2319–26. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2598-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henneman P, Aulchenko YS, Frants RR, Zorkoltseva IV, Zillikens MC, Frolich M, et al. Genetic architecture of plasma adiponectin overlaps with the genetics of metabolic syndrome-related traits. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(4):908–13. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.An SS, Palmer ND, Hanley AJ, Ziegler JT, Brown WM, Haffner SM, et al. Estimating the contributions of rare and common genetic variations and clinical measures to a model trait: adiponectin. Genet Epidemiol. 2013;37(1):13–24. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim AY, Park YJ, Pan X, Shin KC, Kwak SH, Bassas AF, et al. Obesity-induced DNA hypermethylation of the adiponectin gene mediates insulin resistance. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7585. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corella D, Arnett DK, Tsai MY, Kabagambe EK, Peacock JM, Hixson JE, et al. The -256T>C polymorphism in the apolipoprotein A-II gene promoter is associated with body mass index and food intake in the genetics of lipid lowering drugs and diet network study. Clin Chem. 2007;53(6):1144–52. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.084863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Irvin MR, Zhi D, Joehanes R, Mendelson M, Aslibekyan S, Claas SA, et al. Epigenome-wide association study of fasting blood lipids in the Genetics of Lipid-lowering Drugs and Diet Network study. Circulation. 2014;130(7):565–72. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.009158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aslibekyan S, An P, Frazier-Wood AC, Kabagambe EK, Irvin MR, Straka RJ, et al. Preliminary evidence of genetic determinants of adiponectin response to fenofibrate in the Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;23(10):987–94. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aslibekyan S, Kabagambe EK, Irvin MR, Straka RJ, Borecki IB, Tiwari HK, et al. A genome-wide association study of inflammatory biomarker changes in response to fenofibrate treatment in the Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drug and Diet Network. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2012;22(3):191–7. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32834fdd41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitchell BD, McArdle PF, Shen H, Rampersaud E, Pollin TI, Bielak LF, et al. The genetic response to short-term interventions affecting cardiovascular function: rationale and design of the Heredity and Phenotype Intervention (HAPI) Heart Study. Am Heart J. 2008;155(5):823–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cross HE. Population studies and the Old Order Amish. Nature. 1976;262(5563):17–20. doi: 10.1038/262017a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berenson GS Bogalusa Heart Study I. Bogalusa Heart Study: a long-term community study of a rural biracial (Black/White) population. Am J Med Sci. 2001;322(5):293–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Absher DM, Li X, Waite LL, Gibson A, Roberts K, Edberg J, et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis of systemic lupus erythematosus reveals persistent hypomethylation of interferon genes and compositional changes to CD4+ T-cell populations. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(8):e1003678. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aslibekyan S, Demerath EW, Mendelson M, Zhi D, Guan W, Liang L, et al. Epigenome-wide study identifies novel methylation loci associated with body mass index and waist circumference. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2015;23(7):1493–501. doi: 10.1002/oby.21111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson WE, Li C, Rabinovic A. Adjusting batch effects in microarray expression data using empirical Bayes methods. Biostatistics. 2007;8(1):118–27. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxj037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barfield RT, Almli LM, Kilaru V, Smith AK, Mercer KB, Duncan R, et al. Accounting for population stratification in DNA methylation studies. Genet Epidemiol. 2014;38(3):231–41. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pidsley R, CC YW, Volta M, Lunnon K, Mill J, Schalkwyk LC. A data-driven approach to preprocessing Illumina 450K methylation array data. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:293. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rasmussen-Torvik LJ, Pankow JS, Peacock JM, Borecki IB, Hixson JE, Tsai MY, et al. Suggestion for linkage of chromosome 1p35.2 and 3q28 to plasma adiponectin concentrations in the GOLDN Study. BMC Med Genet. 2009;10:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-10-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evangelou E, Ioannidis JPA. Meta-analysis methods for genome-wide association studies and beyond. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14:379–89. doi: 10.1038/nrg3472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bouchard L, Hivert MF, Guay SP, St-Pierre J, Perron P, Brisson D. Placental adiponectin gene DNA methylation levels are associated with mothers' blood glucose concentration. Diabetes. 2012;61(5):1272–80. doi: 10.2337/db11-1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Houde AA, Legare C, Biron S, Lescelleur O, Biertho L, Marceau S, et al. Leptin and adiponectin DNA methylation levels in adipose tissues and blood cells are associated with BMI, waist girth and LDL-cholesterol levels in severely obese men and women. BMC Med Genet. 2015;16:29. doi: 10.1186/s12881-015-0174-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Putku M, Kals M, Inno R, Kasela S, Org E, Kozich V, et al. CDH13 promoter SNPs with pleiotropic effect on cardiometabolic parameters represent methylation QTLs. Hum Genet. 2015;134(3):291–303. doi: 10.1007/s00439-014-1521-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Das M, Sha J, Hidalgo B, Aslibekyan S, Do AN, Zhi D, et al. Association of CPT1A methylation at CPT1A locus with metabolic syndrome in the Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network (GOLDN) study. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0145789. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Westerbacka J, Kolak M, Kiviluoto T, Arkkila P, Siren J, Hamsten A, et al. Genes involved in fatty acid partitioning and binding, lipolysis, monocyte/macrophage recruitment, and inflammation are overexpressed in the human fatty liver of insulin-resistant subjects. Diabetes. 2007;56(11):2759–65. doi: 10.2337/db07-0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garcia-Cardona MC, Huang F, Garcia-Vivas JM, Lopez-Camarillo C, Del Rio Navarro BE, Navarro Olivos E, et al. DNA methylation of leptin and adiponectin promoters in children is reduced by the combined presence of obesity and insulin resistance. Int J Obes (Lond) 2014;38(11):1457–65. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2014.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hidalgo B, Irvin MR, Sha J, Zhi D, Aslibekyan S, Absher D, et al. Epigenome-wide association study of fasting measures of glucose, insulin, and HOMA-IR in the Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network study. Diabetes. 2014;63(2):801–7. doi: 10.2337/db13-1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daniel J, Liebau E. The Ufm1 cascade. Cells. 2014;3(2):627–38. doi: 10.3390/cells3020627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lemaire K, Moura RF, Granvik M, Igoillo-Esteve M, Hohmeier HE, Hendrickx N, et al. Ubiquitin fold modifier 1 (UFM1) and its targe UFBP1 protect pancreatic beta cells from ER stress-induced apoptosis. PLoS One. 2011;6(4):e18517. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nilsson E, Jansson PA, Perfilyev A, Volkov P, Pedersen M, Svensson MK, et al. Altered DNA methylation and differential expression of genes influencing metabolism and inflammation in adipose tissue from subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2014;63(9):2962–76. doi: 10.2337/db13-1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi JK, Bae JB, Lyu J, Kim TY, Kim YJ. Nucleosome deposition and DNA methylation at coding region boundaries. Genome Biol. 2009;10(9):R89. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-9-r89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Graham DB, Becker CE, Doan A, Goel G, Villablanca EJ, Knights D, et al. Functional genomics identifies negative regulatory nodes controlling phagocyte oxidative burst. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7838. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Demerath EW, Guan W, Grove ML, Aslibekyan S, Mendelson M, Zhou YH, et al. Epigenome-wide association study (EWAS) of BMI, BMI change and waist circumference in African American adults identifies multiple replicated loci. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24(15):4464–79. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Al Muftah WA, Al-Shafai M, Zaghlool SB, Visconti A, Tsai PC, Kumar P, et al. Epigenetic associations of type 2 diabetes and BMI in an Arab population. Clin Epigenetics. 2016;8:13. doi: 10.1186/s13148-016-0177-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Houde AA, Legare C, Hould FS, Lebel S, Marceau P, Tchernof A, et al. Cross-tissue comparisons of leptin and adiponectin: DNA methylation profiles. Adipocyte. 2014;3(2):132–40. doi: 10.4161/adip.28308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.