Abstract

AIM

To investigate the clinical implications of infliximab trough levels (IFX-TLs) and antibodies to infliximab (ATI) levels in Crohn’s disease (CD) patients in Asian countries.

METHODS

IFX-TL and ATI level were measured using prospectively collected samples obtained with informed consent from CD patients being treated at Asan Medical Center, South Korea. We analyzed the correlations between IFX-TLs/ATI levels and the clinical activity of CD (quiescent vs active disease) based on the CD activity index, C-reactive protein level, and physician’s judgment of patients’ clinical status at enrollment. The impact of concomitant immunomodulators was also investigated.

RESULTS

This study enrolled 138 patients with CD (84 with quiescent and 54 with active disease). In patients with quiescent and active diseases, the median IFX-TLs were 1.423 μg/mL and 0.163 μg/mL, respectively (P < 0.001) and the median ATI levels were 8.064 AU/mL and 11.209 AU/mL, respectively (P < 0.001). In the ATI-negative and -positive groups, the median IFX-TLs were 1.415 μg/mL and 0.141 μg/mL, respectively (P < 0.001). In patients with and without concomitant immunomodulator use, there were no differences in IFX-TLs (0.632 μg/mL and 1.150 μg/mL, respectively; P = 0.274) or ATI levels (8.655 AU/mL and 9.017 AU/mL, respectively; P = 0.083).

CONCLUSION

IFX-TL/ATI levels were well correlated with the clinical activity in South Korean CD patients. Our findings support the usefulness of IFX-TLs/ATI levels in treating CD patients receiving IFX in clinical practice.

Keywords: Infliximab, Drug effect, Antibody, Crohn’s disease, Drug monitoring

Core tip: This study aimed to clarify the clinical implications of infliximab trough levels (IFX-TLs) and antibodies to infliximab (ATI) levels. They were measured using prospectively collected samples in 138 Crohn’s disease (CD) patients being treated at Asan Medical Center, South Korea. Correlations between IFX-TLs/ATIs and the clinical activity (P < 0.001) were verified in the study. Our findings support the usefulness of IFX-TLs/ATI levels in treating CD patients receiving IFX in clinical practices.

INTRODUCTION

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic systemic inflammatory disease that mainly affects the gastrointestinal tract[1]. It is relatively prevalent in developed countries in North America and Europe, affecting up to 0.5% of the general population[2]. However, its prevalence has doubled over the past decade in countries in East Asia[3,4].

The introduction of biologic agents blocking tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α has greatly modified the treatment strategies for CD and the effects of these agents on remission induction and maintenance has been clearly shown[5]. However, the human body can develop antibodies against infliximab (IFX), the first and most widely used biologic agent for CD treatment. Antibodies to infliximab (ATIs) are thought to be associated with an infusion reaction and reduce the effect of the drug by decreasing its serum level[6,7]. For these reasons, monitoring of the IFX trough levels (IFX-TLs) and ATI levels has been recommended by some experts[8]. However, there are few data clearly defining the relationship among IFX-TLs, ATI levels, and the clinical activity, especially in Asian countries[9]. Besides, the clinical implications and applications of the results in daily clinical practice are still a matter of debate, although the value of the measurement of IFX-TLs/ATI levels for therapy adjustment is undisputable because of practical issues such as cost, the lack of a universally valid assay, and the absence of a cutoff level clearly related to clinical outcomes[10].

In this study, therefore, we analyzed the correlation between IFX-TLs/ATI levels and the clinical activity in South Korean patients with CD using a prospectively collected samples to evaluate the usefulness of therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) in clinical practice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

Between March and May 2015, we enrolled 138 CD patients, aged 17-50 years, receiving IFX as maintenance therapy at the Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) center of Asan Medical Center, a tertiary university hospital in Seoul, South Korea. They gave informed consent prior to being enrolled in the study. All patients unwilling to provide consent were excluded from the study. Patients aged less than 17 years, diagnosed with ulcerative colitis or any other IBD, and on biologic agents other than IFX were also excluded. IFX was administered at an 8-wk interval, mostly at a dose of 5 mg/kg body weight as maintenance therapy[11]. Out of 138 patients, 27 (19.57%) were receiving a double-dose of IFX (10 mg/kg) at the time of enrollment because of a lack of response to the usual maintenance dose. Interval shortening for dose intensification is not reimbursed in South Korea.

Data collection

During the study period, serum samples were obtained from every patient a few hours before IFX administration. The samples were then stored at -20 °C until analysis. IFX-TLs and ATI levels were measured with commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (IDKmonitor® - K9655, K9650; Immundiagnostik AG, Bensheim, Germany).

Measurement of IFX-TLs

Standards, controls, and samples were diluted 200 times and pipetted into wells in duplicate. They were incubated with shaking for 1 h and then for an additional 1 h with conjugate solution at room temperature. After washes, they were mixed with TMB (tetramethylbenzidine) substrate solution and incubated in the dark. Finally, STOP solution was added and the results were checked with an ELISA reader at 450 nm.

Measurement of ATI levels

Controls (negative, positive, and cutoff controls) and samples were mixed with buffers and pretreated with gentle shaking at room temperature for 30 min to dissociate ATIs from IFX. After being washed and pipetted into wells in duplicate, they were incubated overnight at 4 °C. Then, the samples were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with diluted conjugate solution and for an additional 10-20 min with TMB substrate solution in the dark. Finally, STOP solution was added and the results were checked with an ELISA reader at 450 nm. The result was considered negative if the optical density (OD) of the sample was lower than that of the cutoff control. If the OD was higher than that of the cutoff control, the result was considered positive. The ATI level of the cutoff control was set to 10 AU/mL[9] and the ATI level of the sample was calculated with the formula: ATI level of the sample = mean of the sample ODs/mean of the cutoff control ODs × 10 AU/mL.

Assessment of clinical activity was based on the CD activity index (CDAI), serum C-reactive protein (CRP) level, and physician’s judgment of the patients’ clinical status at the time of enrollment[12]. If a patient’s CDAI score was below 150, the serum CRP was within the normal range (< 0.6 mg/dL), and the physician considered that the effect of IFX had lasted for 8 wk at the time of enrollment, the patient was categorized into the quiescent group. However, if a patient’s CDAI score was above 150, the serum CRP was above the upper normal limit (≥ 0.6 mg/dL), or the physician considered that the effect of IFX lasted less than 8 wk, the patient was categorized into the active group. In addition, we also investigated if concomitant immunomodulators, such as azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine or methotrexate, were administered at the time of enrollment.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center (IRB No. 2015-0173).

Statistical analysis

Demographics and baseline characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics. Patients were categorized into groups by their ATI status and the clinical activity. Differences between the groups were compared using the Student t test. Correlations among IFX-TLs/ATI levels and the clinical activity were analyzed with logistic regression analysis. The diagnostic power of IFX-TLs was investigated using area under the receiver-operator characteristic (ROC) curve analysis to obtain the area under the curve (AUC) and 95%CI. The cutoff value for the IFX-TLs that identified disease activity was determined by identifying the point closest to the 1.0 angle. Data were evaluated with SPSS® statistics version 23.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1. Of the 138 patients with CD, 90 (65.2%) were male; the median age at diagnosis and first infusion of IFX were 21 years [interquartile range (IQR) 19-27 years] and 27 years (IQR 22-33 years), respectively. The average duration from diagnosis to first IFX administration was 52 mo (IQR 13-91 mo) and the median follow-up duration with IFX was 47 mo (IQR 30-73 mo) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline characteristics of the 138 South Korean patients in this study with Crohn’s disease who received infliximab treatment n (%)

| Variables | Value |

| Male/female | 90/48 (65.2/34.8) |

| Median age at diagnosis (IQR) (yr) | 21 (19-27) |

| Median age at first infusion (IQR) (yr) | 27 (22-33) |

| Median duration of disease prior to first IFX (IQR) (mo) | 52 (13-91) |

| Indication for IFX treatment | |

| Luminal | 122 (88.4) |

| Perianal fistulizing | 16 (11.6) |

| Median follow-up of IFX treatment (IQR) (mo) | 47 (30-73) |

| Disease location at diagnosis | |

| L1 (ileum) | 19 (13.8) |

| L2 (colon) | 9 (6.5) |

| L3 (ileocolon) | 108 (78.3) |

| Not documented | 2 (1.4) |

| Disease behavior at diagnosis | |

| B1 (non-stricturing non-penetrating) | 115 (83.3) |

| B2 (stricturing) | 7 (5.1) |

| B3 (penetrating) | 16 (11.6) |

| Perianal fistula at diagnosis | |

| Active | 36 (26.1) |

| Previous | 26 (18.8) |

| Smoking status at diagnosis | |

| Current smoker | 26 (18.8) |

| Ex-smoker | 9 (6.6) |

| Never smoker | 103 (74.6) |

| Previous major abdominal surgery prior to first IFX | 44 (31.9) |

| Concomitant immunomodulators | |

| None | 73 (52.9) |

| Azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine | 64 (46.4) |

| Methotrexate | 1 (0.7) |

IQR: Interquartile range; IFX: Infliximab.

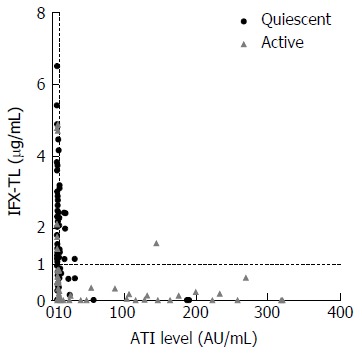

Categorization of the patients into groups

Out of the 138 patients, 84 (60.9%) were categorized into the quiescent group and 54 (39.1%) were categorized into the active group based on our assessment of clinical activity (Figure 1). The median IFX-TL of all patients was 0.941 μg/mL (IQR 0.189-2.143 μg/mL). The cutoff value for identifying quiescent disease by ROC analysis was 0.68 μg/mL (AUC 0.90, 95%CI: 0.84-0.95, sensitivity 83%, specificity 84%). The median ATI level of all patients was 8.846 AU/mL (IQR 7.719-16.727 AU/mL). Finally, 91 patients (65.9%; median 7.619 AU/mL; IQR 6.857-8.834) were categorized as ATI negative and 47 patients (34.1%; median 47.381; IQR 15.381-146.630) were categorized as ATI positive (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Scatter diagram of the study patients. Of these 138 subjects, 84 (60.9%) had quiescent disease and 54 (39.1%) had active disease. The overall median infliximab trough level (IFX-TL) value was 0.941 μg/mL. In total, 91 patients were antibodies to infliximab (ATI) negative (65.9%) and 47 patients were ATI positive (34.1%), with an overall median ATI value of 8.846 (IQR 7.719-16.727) AU/mL.

Among all patients, 65 (47.1%) were taking concomitant immunomodulators (64 patients with azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine and 1 patient with methotrexate) at the time of the study. By clinical activity, 31 out of 84 patients in the quiescent group (36.9%) and 34 out of 54 patients in the active group (63.0%) were taking concomitant immunomodulators. In addition, 44 out of 91 patients in the ATI-negative group (48.4%) and 21 out of 47 patients in the ATI-positive group (44.7%) were taking concomitant immunomodulators.

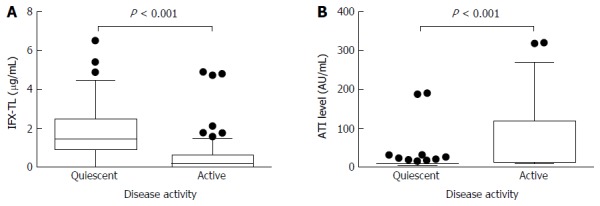

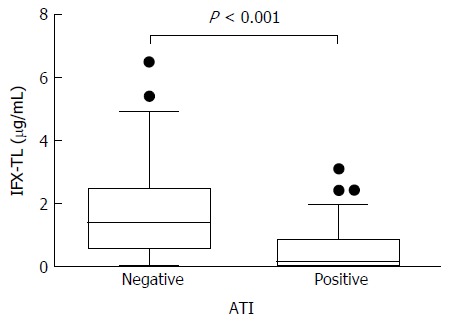

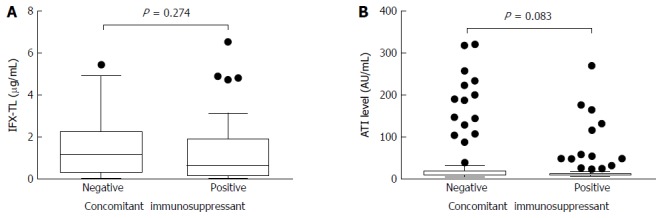

Comparison of differences by group

In patients with quiescent and active disease, the median IFX-TLs were 1.423 μg/mL (IQR 0.877-2.483) and 0.163 μg/mL (IQR 0.002-0.636), respectively (P < 0.001), and the difference between the median values was 1.260 μg/mL. The median ATI levels were 8.064 AU/mL (IQR 6.929-9.908) and 11.209 AU/mL (IQR 8.008-118.835) in patients with quiescent and active disease, respectively (P < 0.001), and the difference between the median values was 3.145 AU/mL (Figure 2). In the ATI-negative and -positive groups, the median IFX-TLs were 1.415 μg/mL (IQR 0.570-2.495) and 0.141 μg/mL (IQR 0.002-0.869), respectively (P < 0.001), and the difference between the median values was 1.274 μg/mL (Figure 3). In patients with and without concomitant immunomodulator use, there were no differences in IFX-TLs (0.632 μg/mL and 1.150 μg/mL, respectively; P = 0.274) or ATI levels (8.655 AU/mL and 9.017 AU/mL, respectively; P = 0.083) (Figure 4).

Figure 2.

Comparisons of the infliximab trough levels and antibody to infliximab levels between patients with quiescent or active disease. The median infliximab trough levels (IFX-TLs) were 1.423 μg/mL (IQR 0.877-2.483) and 0.163 μg/mL (IQR 0.002-0.636), respectively (P < 0.001) (A) and the median antibodies to infliximab (ATIs) levels were 8.064 AU/mL (IQR 6.929-9.908) and 11.209 AU/mL (IQR 8.008-118.835), respectively (P < 0.001) (B) in patients with quiescent and active disease.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the infliximab trough levels between patients with/without antibody to infliximab. In the ATI-negative and -positive groups, the median infliximab trough levels (IFX-TLs) were 1.415 μg/mL (IQR 0.570-2.495) and 0.141 μg/mL (IQR 0.002-0.869), respectively (P < 0.001). ATI: Antibodies to infliximab.

Figure 4.

Comparisons of infliximab trough levels and antibody to infliximab levels in patients with/without immunomodulators. There were no differences in the median infliximab trough level (IFX-TL) (0.632 μg/mL and 1.150 μg/mL, respectively; P = 0.274) (A) and median antibodies to infliximab (ATIs) (8.655 AU/mL and 9.017 AU/mL, respectively; P = 0.083) (B) levels between the 2 groups according to the use of concomitant immunomodulators.

Correlation analysis of variables

After excluding 5 patients without the tendencies of the other patients (3 active patients with high IFX-TLs and low ATI levels and 2 quiescent patients with low IFX-TLs and high ATI levels), we used logistic regression analysis to analyze IFX-TLs and ATI levels as independent factors affecting the clinical activity of CD. The analysis found an explanation power of 54% and 37.4% and overall predictability of 82% and 75.9% for IFX-TL and ATI, respectively (Table 2). By analyzing these 2 factors (IFX-TLs and ATI levels) together, 69 out of 82 patients in the quiescent group (84.1%) and 38 out of 51 patients in the active group (74.5%) were correctly predicted, with an overall predictability of 80.5%. The odds ratios of IFX-TLs and ATI levels were 0.150 (95%CI: 0.065-0.349, P < 0.001) and 1.028 (95%CI: 1.003-1.053, P = 0.014), respectively (Table 3). Therefore, these factors were verified to be significantly associated with the clinical activity of CD.

Table 2.

Factors affecting the clinical activity of Crohn’s disease: Results of logistic regression analysis of each factor

| IFX-TL (μg/mL) | ATI levels (AU/mL) | |

| Overall predictability (%) | 82.0 | 75.9 |

| Quiescent group (%) | 82.9 | 96.3 |

| Active group (%) | 80.4 | 43.1 |

| P value | < 0.001 | 0.003 |

| Odds ratio (95%CI) | 0.103 (0.045-0.236) | 1.055 (1.018-1.093) |

IFX-TL: Infliximab trough level; ATI: Antibody to infliximab.

Table 3.

Factors affecting the clinical activity of Crohn’s disease: Results of logistic regression analysis of the 2 factors together

| IFX-TL (μg/mL) | ATI levels (AU/mL) | |

| Overall predictability (%) | 80.5 | |

| Quiescent group (%) | 84.1 | |

| Active group (%) | 74.5 | |

| P value | < 0.001 | 0.027 |

| Odds ratio (95%CI) | 0.150 (0.065-0.349) | 1.028 (1.003-1.053) |

IFX-TL: Infliximab trough level; ATI: Antibody to infliximab.

DISCUSSION

The most important finding of our current study was that the IFX-TL/ATI levels were well correlated with the clinical activity of CD in South Korean patients. Definite inverse correlations between IFX-TLs and the clinical activity (P < 0.001) and between IFX-TLs and ATI levels (P < 0.001) were verified in this analysis. Additionally, we found a correlation between ATI levels and the clinical activity (P < 0.001). To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate and define the correlations between IFX-TLs/ATI levels and the clinical activity in South Korean CD patients. In addition, the number of study subjects (138 patients) was larger than that of previous Asian studies (less than 100 patients). Thus far, only a few Asian studies have evaluated the usefulness of IFX drug monitoring in IBD patients[9,13,14]. In 2012, a study from Japan evaluated the clinical utility of a novel methodology to measure serum ATI levels in 58 patients with CD. This study found that patients positive for ATIs had significantly lower serum trough levels of infliximab (P < 0.01) and significantly higher clinical activity scores (P < 0.001) than patients negative for ATI[9]. Another Japanese study revealed a correlation between the clinical efficacy of IFX and serum IFX-TLs in 57 patients with CD (P < 0.01)[14].

In recent decades, anti-TNF-α agents have been introduced and become widely used in the management of CD. This change in the treatment paradigm for CD may alter the natural history of CD. Several studies have reported that the prognosis of CD, such as the hospitalization or surgery rate, improved after the introduction of anti-TNF-α therapy[15]. In Asian countries, the incidence of CD has rapidly increased and anti-TNF-α agents have been used increasingly earlier and more frequently in recent decades[4,16]. However, despite the clinical efficacy of this treatment, up to 40% of patients do not respond to induction therapy with anti-TNF-α agents[17-19]. Additionally, about 20% of initial responders may lose responsiveness to anti-TNF-α therapy each year[5]. Because of this phenomenon, the importance of TDM, such as that of drug and anti-drug antibody levels, has been highlighted recently for the establishment of appropriate strategies in clinical practice. This TDM-based approach has been especially emphasized in maintenance therapy, in cases of a loss of response, persistent elevation of CRP, and persistent mucosal lesions[20-25]. In addition, this kind of strategy provides significant cost savings compared with conventional IFX dose intensification in CD patients with a loss of response[26]. However, in the TAXIT trial, which has taken a more proactive approach than before, with TDM applied to patients still responding to maintenance therapy, a TDM-based dose adjustment was not superior to dose adjustment based on symptoms alone[27]. In other words, we should selectively adjust TDM-based personalized treatment strategies to improve the outcomes of IBD patients in daily clinical practice. Additionally, the major limitation of previous studies regarding ATI was an inability to identify whether or not ATIs were neutralizing the drug, because the presence of ATI in serum does not necessarily correlate with a loss of response[28].

Our optimal cutoff value for IFX-TLs for identifying disease activity was 0.68 μg/mL, which is consistent with previous studies. A study from Denmark found an optimal cutoff value of IFX ≥ 0.5 μg/mL for the prevention of a loss of response to IFX[29]. A Japanese study reported that more potent effects were achieved at higher serum IFX trough levels and that the threshold of the clinical responses was an IFX trough level of 1.0 μg/mL[14]. Another study from Japan suggested an optimal cutoff value of IFX-TLs of 0.6 μg/mL for CRP[13]. However, previous studies suggested various cutoff values of IFX for predicting the efficacy of IFX treatment from below 1 μg/mL to over 7 μg/mL[10]. This heterogeneity could be due to different methodologies, different study designs and subject characteristics, and different endpoints.

In our current analysis, IFX-TLs/ATI levels were not significantly different between the groups treated with and without concomitant immunomodulators. The addition of immunomodulators to anti-TNF-α treatment can improve the efficacy of anti-TNF-α treatment in IBD[30,31], especially in patients who are naïve to both immunomodulators and IFX, and can decrease ATI formation, even at suboptimal doses[32]. However, we did not observe any ability for immunomodulators such as azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine or methotrexate to increase IFX-TLs or decrease ATI formation, possibly because of the heterogeneity of the study subjects and the limitation of a study design. In general, patients in the active group seemed more frequently to be in a combination regimen to maximize the efficacy of IFX than patients in the quiescent group. In our study, 34 out of the 54 patients in the active group received concomitant immunomodulators and 31 out of the 84 patients in the quiescent group received concomitant immunomodulators at the time of enrollment (63.0% vs 36.9%, P = 0.003).

Among our study patients, we observed 5 patients not following the tendencies of the other patients (3 active patients with high IFX-TLs and low ATI levels and 2 quiescent patients with low IFX-TLs and high ATI levels). For the former 3 patients, there are 2 possible interpretations of this situation: (1) high inflammatory burden of the disease; or (2) factors other than TNF-α that play a major pathologic role in these patients[33]. In this situation, we should consider dose intensification or switching to another class of drugs such as anti-integrins. For the latter 2 patients, their clinical activity is low despite low IFX-TLs and high ATI levels. In other words, their clinical activity is controlled regardless of anti-TNF-α therapy. In this situation, we should consider stopping the anti-TNF-α therapy if long-term deep remission is achieved[33].

The major potential limitation of this study was the use of time-consuming and difficult-to-apply ELISA-based commercial kits to obtain IFX-TL/ATI values. The usual turnaround time of ELISA-based kits for IFX-TLs/ATI levels is at least 8 h, which would delay the target dosage adjustment of the subsequent infusion. However, recent efforts to replace commonly used ELISA-based kits with a rapid, user-friendly, point-of-care IFX assay would make immediate target dosage adjustment possible in the near future[34]. Another limitation of our current study was the lack of analysis of mucosal healing. In our institution, we routinely check CDAI and perform blood tests, including CRP, in CD patients on IFX maintenance therapy during follow-up. Therefore, we used the CDAI, CRP and the physician’s judgement of the duration of the IFX effect to assess the clinical activity of CD in this study. Likewise, previous studies used various outcomes to evaluate the usefulness of IFX-TLs/ATI levels, including clinician’s assessment, patient-reported outcomes such as CDAI or the Harvey-Bradshaw index, or surrogate markers such as CRP[12]. A recent study from Japan evaluating the relationship between serum IFX-TLs and disease activities in 45 patients with CD showed that endoscopic activity negatively correlated with serum IFX-TLs and that mucosal healing requires a higher IFX trough level than that required to achieve the normalization of other clinical markers such as albumin and CRP[13].

In conclusion, IFX-TL/ATI levels are well correlated with the clinical activity of South Korean CD patients. Our findings confirm the usefulness of IFX-TLs/ATI levels in treating CD patients receiving IFX in clinical practice. Therefore, we can use IFX-TLs/ATI levels in making decisions in patients with loss of response to IFX therapy. Further larger prospective studies are warranted to establish guidelines and to reveal the ability of concomitant immunomodulators to decrease the formation of ATIs.

COMMENTS

Background

The prevalence of Crohn’s disease (CD) is rapidly increasing in Asian countries and the use of infliximab (IFX) is also increasing because the drug is proved to be effective in controlling disease activity. However, about 20% of initial responders to induction therapy with IFX suffer from loss of responsiveness (LOR) to the drug and antibodies to IFX (ATI) are thought to be a cause for the problem. As limited data are available in Asian patients with CD, this study tried to verify the correlations between IFX trough levels (IFX-TLs)/ATI levels and the clinical activity of CD.

Research frontiers

LOR to IFX has become an important issue in treating CD patients and alternative treatment strategies for patients suffering LOR should be raised. Furthermore, there is no clear indication to discontinue IFX maintenance therapy after clinical remission is retained for a long time. Along with clarifying the correlations between IFX-TLs/ATI levels and the clinical activity of CD, this study suggested the ways to making decisions using IFX-TLs and ATI levels in those patients.

Innovations and breakthroughs

This was the first study analyzing relationship between IFX-TLs/ATI levels and the clinical activity of CD in South Korea. Furthermore, our findings support the usefulness of IFX-TLs/ATI levels in treating CD patients receiving IFX in clinical practice.

Applications

Measuring IFX-TLs and ATI levels could be used in making decisions in patients suffering LOR. If high IFX-TL and low ATI level were shown in the patients, we should consider dose intensification or switching to another class of drugs such as anti-integrins. On the other hand, it can be used in to decide discontinuation of IFX maintenance therapy in patients with quiescent disease. If low IFX-TL and high ATI level were shown in the patients, we should consider stopping the anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α therapy if long-term deep remission is achieved.

Terminology

Infliximab: A drug that works as monoclonal antibody blocking action of TNF-α which is known to be playing a main role in pathogenesis of CD. Trough level: The lowest level of a drug. If a drug is administered periodically, the trough level should be measured just before the administration of the next doses.

Peer-review

This was the first study analyzing and revealing definite correlations among IFX-TLs/ATI levels and clinical activity in CD patients in South Korea. Clinical implications and applications to practices are suggested well.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Institutional review board statement: The study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards of Asan Medical Center (Seoul, South Korea; IRB No. 2015-0173).

Informed consent statement: All study participants, or their legal guardian, provided written consent prior to study enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors have no conflict of interest related to the manuscript.

Data sharing statement: There is no additional data available.

Peer-review started: September 26, 2016

First decision: December 2, 2016

Article in press: January 17, 2017

P- Reviewer: M’Koma A, Trifan A S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang FF

References

- 1.Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ. Crohn’s disease. Lancet. 2012;380:1590–1605. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60026-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, Ghali WA, Ferris M, Chernoff G, Benchimol EI, Panaccione R, Ghosh S, Barkema HW, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:46–54.e42; quiz e30. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ng WK, Wong SH, Ng SC. Changing epidemiological trends of inflammatory bowel disease in Asia. Intest Res. 2016;14:111–119. doi: 10.5217/ir.2016.14.2.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang SK, Yun S, Kim JH, Park JY, Kim HY, Kim YH, Chang DK, Kim JS, Song IS, Park JB, et al. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in the Songpa-Kangdong district, Seoul, Korea, 1986-2005: a KASID study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:542–549. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh S, Pardi DS. Update on anti-tumor necrosis factor agents in Crohn disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2014;43:457–478. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Su CG, Lichtenstein GR. Influence of immunogenicity on the long-term efficacy of infliximab in Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1544–1546. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ding NS, Hart A, De Cruz P. Systematic review: predicting and optimising response to anti-TNF therapy in Crohn’s disease - algorithm for practical management. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43:30–51. doi: 10.1111/apt.13445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vande Casteele N, Feagan BG, Gils A, Vermeire S, Khanna R, Sandborn WJ, Levesque BG. Therapeutic drug monitoring in inflammatory bowel disease: current state and future perspectives. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2014;16:378. doi: 10.1007/s11894-014-0378-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Imaeda H, Andoh A, Fujiyama Y. Development of a new immunoassay for the accurate determination of anti-infliximab antibodies in inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:136–143. doi: 10.1007/s00535-011-0474-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silva-Ferreira F, Afonso J, Pinto-Lopes P, Magro F. A Systematic Review on Infliximab and Adalimumab Drug Monitoring: Levels, Clinical Outcomes and Assays. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:2289–2301. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park SH, Hwang SW, Kwak MS, Kim WS, Lee JM, Lee HS, Yang DH, Kim KJ, Ye BD, Byeon JS, et al. Long-Term Outcomes of Infliximab Treatment in 582 Korean Patients with Crohn’s Disease: A Hospital-Based Cohort Study. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:2060–2067. doi: 10.1007/s10620-016-4105-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nanda KS, Cheifetz AS, Moss AC. Impact of antibodies to infliximab on clinical outcomes and serum infliximab levels in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:40–47; quiz 48. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Imaeda H, Bamba S, Takahashi K, Fujimoto T, Ban H, Tsujikawa T, Sasaki M, Fujiyama Y, Andoh A. Relationship between serum infliximab trough levels and endoscopic activities in patients with Crohn’s disease under scheduled maintenance treatment. J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:674–682. doi: 10.1007/s00535-013-0829-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hibi T, Sakuraba A, Watanabe M, Motoya S, Ito H, Motegi K, Kinouchi Y, Takazoe M, Suzuki Y, Matsumoto T, et al. Retrieval of serum infliximab level by shortening the maintenance infusion interval is correlated with clinical efficacy in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1480–1487. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Costa J, Magro F, Caldeira D, Alarcão J, Sousa R, Vaz-Carneiro A. Infliximab reduces hospitalizations and surgery interventions in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:2098–2110. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e31829936c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park SH, Yang SK, Park SK, Kim JW, Yang DH, Jung KW, Kim KJ, Ye BD, Byeon JS, Myung SJ, et al. Long-term prognosis of crohn’s disease and its temporal change between 1981 and 2012: a hospital-based cohort study from Korea. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:488–494. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000441203.56196.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanauer SB, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, Mayer LF, Schreiber S, Colombel JF, Rachmilewitz D, Wolf DC, Olson A, Bao W, et al. Maintenance infliximab for Crohn’s disease: the ACCENT I randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1541–1549. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08512-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, Enns R, Hanauer SB, Panaccione R, Schreiber S, Byczkowski D, Li J, Kent JD, et al. Adalimumab for maintenance of clinical response and remission in patients with Crohn’s disease: the CHARM trial. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:52–65. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schreiber S, Khaliq-Kareemi M, Lawrance IC, Thomsen OØ, Hanauer SB, McColm J, Bloomfield R, Sandborn WJ. Maintenance therapy with certolizumab pegol for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:239–250. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adedokun OJ, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Xu Z, Marano CW, Johanns J, Zhou H, Davis HM, Cornillie F, et al. Association between serum concentration of infliximab and efficacy in adult patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:1296–1307.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roblin X, Marotte H, Rinaudo M, Del Tedesco E, Moreau A, Phelip JM, Genin C, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Paul S. Association between pharmacokinetics of adalimumab and mucosal healing in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:80–84.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cornillie F, Hanauer SB, Diamond RH, Wang J, Tang KL, Xu Z, Rutgeerts P, Vermeire S. Postinduction serum infliximab trough level and decrease of C-reactive protein level are associated with durable sustained response to infliximab: a retrospective analysis of the ACCENT I trial. Gut. 2014;63:1721–1727. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Afif W, Loftus EV, Faubion WA, Kane SV, Bruining DH, Hanson KA, Sandborn WJ. Clinical utility of measuring infliximab and human anti-chimeric antibody concentrations in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1133–1139. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roblin X, Rinaudo M, Del Tedesco E, Phelip JM, Genin C, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Paul S. Development of an algorithm incorporating pharmacokinetics of adalimumab in inflammatory bowel diseases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1250–1256. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yanai H, Lichtenstein L, Assa A, Mazor Y, Weiss B, Levine A, Ron Y, Kopylov U, Bujanover Y, Rosenbach Y, et al. Levels of drug and antidrug antibodies are associated with outcome of interventions after loss of response to infliximab or adalimumab. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:522–530.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steenholdt C, Brynskov J, Thomsen OØ, Munck LK, Fallingborg J, Christensen LA, Pedersen G, Kjeldsen J, Jacobsen BA, Oxholm AS, Kjellberg J, Bendtzen K, Ainsworth MA. Individualised therapy is more cost-effective than dose intensification in patients with Crohn’s disease who lose response to anti-TNF treatment: a randomised, controlled trial. Gut. 2014;63:919–927. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vande Casteele N, Ferrante M, Van Assche G, Ballet V, Compernolle G, Van Steen K, Simoens S, Rutgeerts P, Gils A, Vermeire S. Trough concentrations of infliximab guide dosing for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:1320–1329.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ungar B, Chowers Y, Yavzori M, Picard O, Fudim E, Har-Noy O, Kopylov U, Eliakim R, Ben-Horin S. The temporal evolution of antidrug antibodies in patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with infliximab. Gut. 2014;63:1258–1264. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steenholdt C, Bendtzen K, Brynskov J, Thomsen OØ, Ainsworth MA. Cut-off levels and diagnostic accuracy of infliximab trough levels and anti-infliximab antibodies in Crohn’s disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:310–318. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2010.536254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W, Mantzaris GJ, Kornbluth A, Rachmilewitz D, Lichtiger S, D’Haens G, Diamond RH, Broussard DL, et al. Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1383–1395. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Panaccione R, Ghosh S, Middleton S, Márquez JR, Scott BB, Flint L, van Hoogstraten HJ, Chen AC, Zheng H, Danese S, et al. Combination therapy with infliximab and azathioprine is superior to monotherapy with either agent in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:392–400.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Schaik T, Maljaars JP, Roopram RK, Verwey MH, Ipenburg N, Hardwick JC, Veenendaal RA, van der Meulen-de Jong AE. Influence of combination therapy with immune modulators on anti-TNF trough levels and antibodies in patients with IBD. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:2292–2298. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ben-Horin S. Drug Level-based Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Therapy: Ready for Prime Time? Gastroenterology. 2015;148:1268–1271. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Afonso J, Lopes S, Gonçalves R, Caldeira P, Lago P, Tavares de Sousa H, Ramos J, Gonçalves AR, Ministro P, Rosa I, et al. Proactive therapeutic drug monitoring of infliximab: a comparative study of a new point-of-care quantitative test with two established ELISA assays. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:684–692. doi: 10.1111/apt.13757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]