Abstract

ADP-forming acetyl-CoA synthetase (ACD) catalyzes the interconversion of acetyl-CoA and acetate. The related succinyl-CoA synthetase follows a three-step mechanism involving a single phosphoenzyme, but a novel four-step mechanism with two phosphoenzyme intermediates was proposed for Pyrococcus ACD. Characterization of enzyme variants of Entamoeba ACD in which the two proposed phosphorylated His residues were individually altered revealed that only His252 is essential for enzymatic activity. Analysis of variants altered at two residues proposed to interact with the phosphohistidine loop that swings between distinct parts of the active site are consistent with a mechanism involving a single phosphoenzyme intermediate. Our results suggest ACDs with different subunit structures may employ slightly different mechanisms to bridge the span between active sites I and II.

Keywords: acetyl-CoA synthetase, ATP, acetate, acetyl-CoA, energy metabolism, Entamoeba

INTRODUCTION

ADP-forming acetyl-CoA synthetase (ACD; E.C 6.2.1.13), a member of the NDP-forming acyl-CoA synthetase enzyme superfamily (1), catalyzes the interconversion of acetate and acetyl-CoA: acetyl-CoA + ADP + Pi ⇌ acetate + CoA + ATP (ΔG°′=−0.9 kJ/mol). ACD has been identified and characterized from a number of acetate-producing archaea that lack the traditional acetate kinase/phosphotransacetylase pathway (2–4) and in the bacterium Chloroflexus aurantiacus (5). This enzyme is also present in the amitochondriate parasitic protozoan species Entamoeba histolytica (6) and Giardia lamblia (7). In E. histolytica, ACD has been proposed to function in energy conservation by providing ATP via substrate level phosphorylation (8) and in CoA recycling (9), but may also function in the reverse direction for acetate utilization (8). Putative ACD sequences have been identified in a few other parasitic protozoan species including Plasmodium falciparum and other Plasmodium species, Cryptosporidium muris, and Blastocystis hominis (8).

ACD subunit structure shows substantial heterogeneity. ACDs from Pyrococcus furiosus (10–12) and Thermococcus kodakarensis (13,14) are heterotetramers with two alpha and two beta subunits, each of which is encoded by multiple genes. The ACDs from Haloarcula marismortui (2), Archaeoglobus fulgidus (15), and Methanococcus jannaschii (15) are homodimers in which the alpha and beta domains are fused together by a hinge region. The eukaryotic G. lamblia and E. histolytica ACDs are homodimers as well (8,16). The bacterial Chloroflexus aurantiacus ACD (5) and the archaeal Pyrobaculum aerophilum ACD (2,17) also have fused alpha/beta subunits but in a homotetrameric and homooctameric arrangement, respectively.

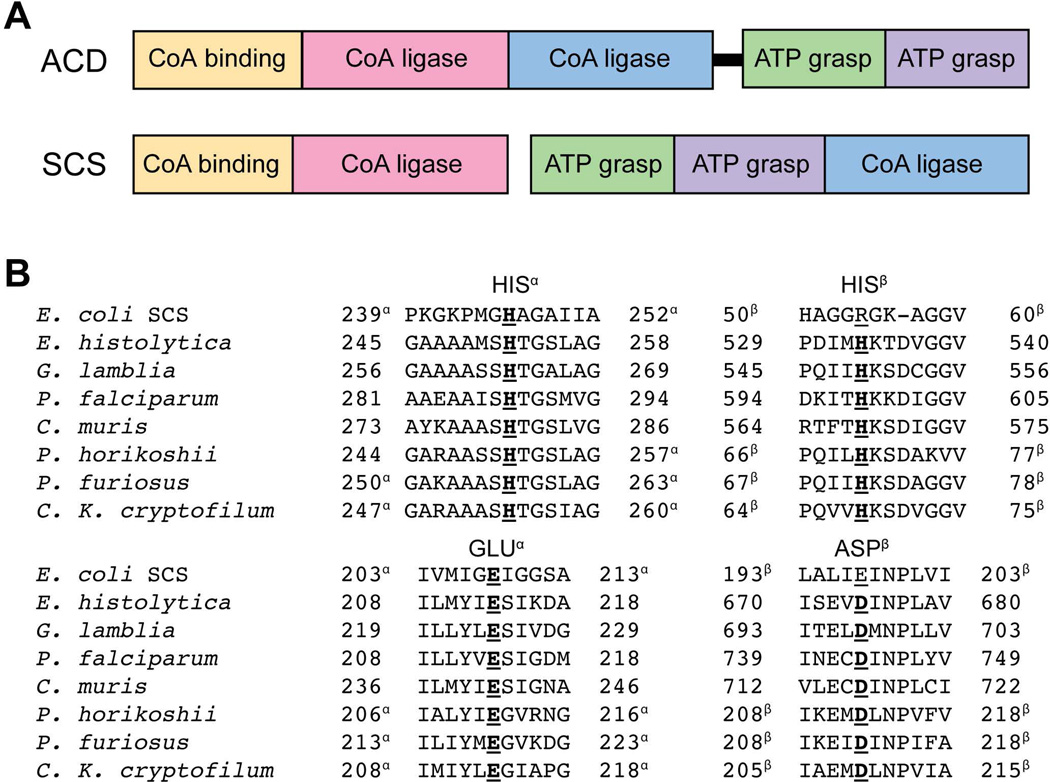

ACD belongs to the same enzyme superfamily as succinyl-CoA synthetase (SCS; EC 6.2.1.4), which catalyzes a similar conversion of succinyl-CoA to succinate as part of the citric acid cycle. SCS is a heterotetrameric enzyme with two active sites, one residing in each alpha-beta dimer (18). The five subdomains of SCS are conserved in ACD, although the arrangement between the subunits differs (Fig. 1A). A chief distinction is that the CoA ligase domain is relocated to the alpha subunit in ACD. Notably, this domain shuffling maintains the arrangements of certain domains that function together in the active site, such as the CoA binding and CoA ligase domains and the two ATP grasp domains.

FIGURE 1.

Comparison of ACD and SCS. (A) Schematic of the domain organization in ACD and SCS. Each is comprised of five domains with relative sizes as shown arranged in a unique pattern. ACD enzymes may have a hinge region (indicated by the black rectangle) that connects the alpha and beta domains into a single subunit as opposed to separate α and β subunits. SCS enzymes are encoded as two separate subunits as shown. (B) Sequence alignment of E. coli SCS and ACD from multiple organisms. α and β indicate the respective subunit for those enzymes in which the alpha and beta domains are encoded by separate genes.

Structural and kinetic analyses of SCS (19–23) indicate the enzyme follows a three-step mechanism that proceeds through a phosphoenzyme intermediate:

Step 1: succinyl-CoA + Pi + E ⇌ E~succinyl-P + CoA

Step 2: E~succinyl-P ⇌ E-Hisα-P + succinate

Step 3: E-Hisα-P + ADP ⇌ E + ATP

The succinyl-CoA and phosphate binding pockets are located in the alpha subunit of SCS in a region designated as Site I. After binding succinyl-CoA, a succinyl-phosphate intermediate is formed and CoA is released (Step 1). The phosphoryl group is then transferred to a His residue (Hisα) located within a loop in the alpha subunit (designated as the phosphohistidine loop) and succinate is released (Step 2). It was postulated that a conformational change subsequently swings this phosphohistidine loop from its Site I position to a position closer to the nucleotide binding site of the beta subunit (Site II) (19). The phosphoryl group is then transferred to a nucleotide diphosphate and the newly formed nucleotide triphosphate is released (Step 3). Two additional glutamate residues have been determined to be crucial for the phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of the active site His (23).

The mechanism of ACD was originally thought to be analogous to that of SCS. However, Brasen et al. (24) observed phosphorylation of both the alpha and beta subunits of P. furiosus ACD (PfACD) when incubated with 32P-labeled ATP or 32Pi. They proposed a four-step mechanism containing an additional phosphoryl transfer step (Step 3) to a separate His residue located in the beta subunit (Hisβ):

Step 1: acetyl-CoA + Pi + E ⇌ E~acetyl-P + CoA

Step 2: E~acetyl-P ⇌ E-Hisα-P + acetate

Step 3: E-Hisα-P ⇌ E-Hisβ-P

Step 4: E-Hisβ-P + ADP ⇌ E + ATP

Recently, the first structural characterization of an ACD from the hyperthermophilic archaea Candidatus Korarchaeum cryptofilum (CKcACD) was performed (25). This enzyme was crystallized with different ligands to reveal nine structures, including multiple structures showing the phosphorylated Hisα intermediate. The results confirm the swinging loop mechanism for ACD in which the phosphohistidine loop moves from Site I to Site II of the active site.

In this study, we investigate four active site residues of E. histolytica ACD (EhACD) and assess their roles through kinetic characterization of site-altered enzyme variants and isotopic labeling to examine phosphorylation. Our results are consistent with a three-step SCS-like mechanism involving a single phosphoenzyme intermediate and suggest that heterogeneity in structure among ACDs may dictate a requirement for an additional phosphoenzyme intermediate to bridge the gap between Site I and Site II for some enzymes.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, VWR, Gold Biotechnology, Fisher Scientific, Life Technologies, and JR Scientific. Primers were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies.

Sequence alignment

Putative ACD amino acid sequences were identified by PSI-BLAST (26) using the E. histolytica ACD sequence as the query (XP_656290). Sequences were aligned using ClustalX (27).

Site-directed mutagenesis of acd

Site-directed mutagenesis of an Escherichia coli codon-optimized E. histolytica acd gene was performed using the Quikchange Lightning Kit (Stratagene, Inc.) according to manufacturer’s specifications. Primers used are listed in Supplemental Table 1. Alterations were confirmed by sequencing at the Clemson University Genomics Institute.

Heterologous production of enzyme variants

Recombinant EhACD and its variants were produced in E. coli Rosetta2(DE3) pLysS cells (Novagen) and purified using nickel affinity chromatography as described in (8). Purity of the enzymes was examined by SDS-PAGE (Supplemental Fig. 1), and protein concentration was determined spectrophotometrically. Wild-type and variant enzymes were subjected to gel filtration chromatography as described previously (8) to confirm the alterations did not influence tertiary structure.

Determination of kinetic parameters

Enzymatic activity in the acetate-forming direction was determined by measuring release of CoA-SH from acyl-CoA using Ellman’s thiol reagent as previously described (8,28). Enzymatic activity in the acetyl-CoA forming direction was determined using the hydroxamate assay (29,30). One unit of activity is defined as 1 µmol product per minute per mg protein. Saturating substrate concentrations for each variant are summarized in Supplemental Table 2. The limit of detection was 0.01 mmol min−1 mg−1 and enzymes with activity below this level were defined as inactive.

Apparent kinetic parameters were determined by varying the concentration of a single substrate while the other substrates were held at constant saturating concentrations. Nonlinear regression analysis using KaleidaGraph (Synergy Software) was used to fit the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation for determination of the apparent steady-state kinetic parameters Km and kcat and their standard deviations.

The kinetic parameters for wild-type enzyme shown in Tables 1, 2, and 3 were originally reported in (8). The analyses of the wild-type and variant enzymes described here were performed concurrently, and thus the kinetic parameters for the wild-type enzyme were not repeated here.

TABLE 1.

Apparent kinetic parameters of the His533 variants in the acetate-forming direction.

| Varied Substrate |

Enzyme Variant |

kcat (s−1) |

Km (mM) |

kcat/Km (mM−1s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetyl-CoA | WTa | 111 ± 2 | 0.043 ± 0.005 | 2600 ± 371 |

| His533Arg | 18 ± 1 | 0.016 ± 0.003 | 1115 ± 166 | |

| His533Lys | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 0.030 ± 0.003 | 79 ± 6 | |

| His533Ala | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 0.010 ± 0.001 | 266 ± 7 | |

| His533Asn | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 0.015 ± 0.001 | 92 ± 6 | |

| His533Gln | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 0.019 ± 0.004 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | |

| His533Asp | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 0.027 ± 0.008 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | |

| His533Glu | 0.12 ± 0.001 | 0.012 ± 0.002 | 10 ± 1 | |

| ADP | WTa | 138 ± 1 | 1.56 ± 0.15 | 89 ± 8 |

| His533Arg | 20 ± 2 | 0.64 ± 0.18 | 32 ± 7 | |

| His533Lys | 3.3 ± 0.5 | 0.97 ± 0.14 | 3.4 ± 0.8 | |

| His533Ala | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 0.41 ± 0.03 | 6.9 ± 3.0 | |

| His533Asn | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 0.57 ± 0.15 | 2.5 ± 0.8 | |

| His533Gln | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 1.28 ± 0.08 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | |

| His533Asp | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 0.60 ± 0.08 | 2.9 ± 0.5 | |

| His533Glu | 0.27 ± 0.03 | 1.19 ± 0.08 | 0.2 ± 0.01 | |

| Pi | WTa | 115 ± 8 | 1.77 ± 0.18 | 65 ± 2 |

| His533Arg | 14 ± 1 | 0.15 ± 0.03 | 95 ± 17 | |

| His533Lys | 3.1 ± 0.4 | 3.25 ± 0.35 | 0.97 ± 0.20 | |

| His533Ala | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 0.75 ± 0.10 | 3.1 ± 0.3 | |

| His533Asn | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 0.94 ± 0.25 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | |

| His533Gln | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 0.86 ± 0.21 | 2.1 ± 0.5 | |

| His533Asp | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 0.25 ± 0.08 | 7.3 ± 3 | |

| His533Glu | 0.22 ± 0.01 | 0.18 ± 0.04 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | |

These values were reported in (8).

Values are the mean of three replicates ± standard deviation

TABLE 2.

Apparent kinetic parameters of the His533 variants in the acetyl-CoA forming direction.

| Varied Substrate |

Enzyme Variant |

kcat (s−1) |

Km (mM) |

kcat/Km (mM−1s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetate | WTa | 233 ± 2.7 | 14 ± 0.61 | 16 ± 1 |

| His533Arg | 5.6 ± 0.09 | 1.7 ± 0.8 | 3.3 ± 0.1 | |

| His533Lys | 3.4 ± 0.04 | 0.84 ± 0.60 | 4.1 ± 0.2 | |

| His533Ala | 3.3 ± 0.09 | 0.68 ± 0.10 | 4.8 ± 0.4 | |

| His533Asn | 1.5 ± 0.02 | 0.76 ± 0.70 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | |

| His533Gln | 1.2 ± 0.02 | 0.55 ± 0.20 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | |

| His533Asp | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 0.31 ± 0.02 | 0.59 ± 0.01 | |

| His533Glu | 0.26 ± 0.002 | 0.40 ± 0.01 | 0.67 ± 0.28 | |

| CoA | WTa | 328 ± 5.3 | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 1100 ± 57 |

| His533Arg | 7.0 ± 0.15 | 0.10 ± 0.004 | 70 ± 2 | |

| His533Lys | 4.1 ± 0.04 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 287 ± 10 | |

| His533Ala | 4.2 ± 0.08 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 60 ± 6 | |

| His533Asn | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 0.08 ± 0.004 | 26 ± 1 | |

| His533Gln | 1.3 ± 0.03 | 0.011 ± 0.001 | 0.57 ± 0.02 | |

| His533Asp | 0.25 ± 0.01 | 0.011 ± 0.001 | 23 ± 2 | |

| His533Glu | 0.27 ± 0.003 | 0.26 ± 0.02 | 1.1 ± 0.01 | |

| ATP | WTa | 320 ± 4.4 | 12 ± 0.4 | 27 ± 1 |

| His533Arg | 6.6 ± 0.06 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | |

| His533Lys | 3.7 ± 0.09 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | |

| His533Ala | 3.3 ± 0.03 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | |

| His533Asn | 2.0 ± 0.10 | 7.7 ± 0.6 | 0.26 ± 0.01 | |

| His533Gln | 1.4 ± 0.03 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 116 ± 7 | |

| His533Asp | 0.25 ± 0.01 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 0.21 ± 0.02 | |

| His533Glu | 0.28 ± 0.002 | 3.9 ± 0.1 | 0.07 ± 0.002 | |

as reported in (8)

Values are the mean of three replicates ± standard deviation

TABLE 3.

Apparent kinetic parameters of the Asp674 variants in both directions of the reaction.

| Acetyl-CoA forming direction |

kcat (s−1) |

Km (mM) |

kcat/Km (mM−1s−1) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetate | WTa | 233 ± 3 | 14 ± 0.6 | 16 ± 1 |

| Asp674Ala | 2.9 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | |

| Asp674Asn | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 0.96 ± 0.05 | 1.3 ± 0.04 | |

| Asp674Glu | 50 ± 2 | 3.9 ± 0.3 | 13 ± 0.03 | |

| CoA | WTa | 328 ± 5 | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 1100 ± 57 |

| Asp674Ala | 4.2 ± 0.1 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 36 ± 1 | |

| Asp674Asn | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 0.041 ± 0.004 | 28 ± 1 | |

| Asp674Glu | 44 ± 0.1 | 0.24 ± 0.02 | 224 ± 13 | |

| ATP | WTa | 320 ± 4 | 12 ± 0.4 | 27 ± 1 |

| Asp674Ala | 3.2 ± 0.03 | 4.0 ± 0.1 | 0.81 ± 0.03 | |

| Asp674Asn | 1.2 ± 0.02 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 0.44 ± 0.02 | |

| Asp674Glu | 53 ± 1 | 4.6 ± 0.2 | 9.8 ± 0.3 | |

| Acetate-forming direction | ||||

| Acetyl-CoA | WT# | 111 ± 2 | 0.043 ± 0.005 | 2600 ± 370 |

| Asp674Ala | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 0.008 ± 0.0001 | 207 ± 10 | |

| Asp674Asn | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 0.016 ± 0.002 | 78 ± 8 | |

| Asp674Glu | 16 ± 1 | 0.022 ± 0.002 | 704 ± 23 | |

| ADP | WTa | 138 ± 1 | 1.56 ± 0.15 | 89 ± 8 |

| Asp674Ala | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 0.39 ± 0.03 | 6.8 ± 0.5 | |

| Asp674Asn | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 0.43 ± 0.01 | 2.8 ± 0.3 | |

| Asp674Glu | 25 ± 2 | 1.44 ± 0.08 | 17 ± 2 | |

| Pi | WTa | 115 ± 8 | 1.77 ± 0.18 | 65 ± 2 |

| Asp674Ala | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 1.42 ± 0.11 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | |

| Asp674Asn | 0.9 ± 0.04 | 0.57 ± 0.05 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | |

| Asp674Glu | 25 ± 5 | 2.8 ± 0.9 | 8.9 ± 1.1 | |

as reported in (8)

Values are the mean of three replicates ± standard deviation

Radiolabeled phosphorylation assay

In order to detect phosphorylated enzyme intermediates, enzyme (17 µg) was incubated at 37°C with [γ-32P]ATP (2.5 µCi; 10 mM final concentration) or with 32Pi (1 µCi; 4 mM final concentration) and 0.3 mM acetyl-CoA in 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0 at 25°C]. An equal volume of buffer containing 5% β-mercaptoethanol (v/v), 2% SDS (w/v), 25% glycerol (v/v), 0.625 M Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 0.01% (w/v) bromophenol blue was added to stop the reaction and samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE. Results were visualized by autoradiography.

Distance Calculations

The CKcACDI-c structure (PDB:4XZ3) (25) was used for distance measurements. The distance between two atoms was determined using the Monitor Distance function in Discovery Studio software v3.5 (Biovia).

RESULTS

Roles of His252 and His533

The two proposed phosphorylation sites in the four-step ACD mechanism, His257α and His71β in PfACD (corresponding to His252 and His533, respectively, in EhACD), are conserved but only the alpha His is conserved across the NDP-forming acyl-CoA synthetase superfamily (Fig. 1B). His252 and His533 were individually changed to other residues. The purified enzyme variants were subjected to size exclusion chromatography and the elution profiles versus molecular weight standards and the wild-type enzyme were consistent with a dimeric structure (data not shown), and activity was assayed in both directions of the reaction.

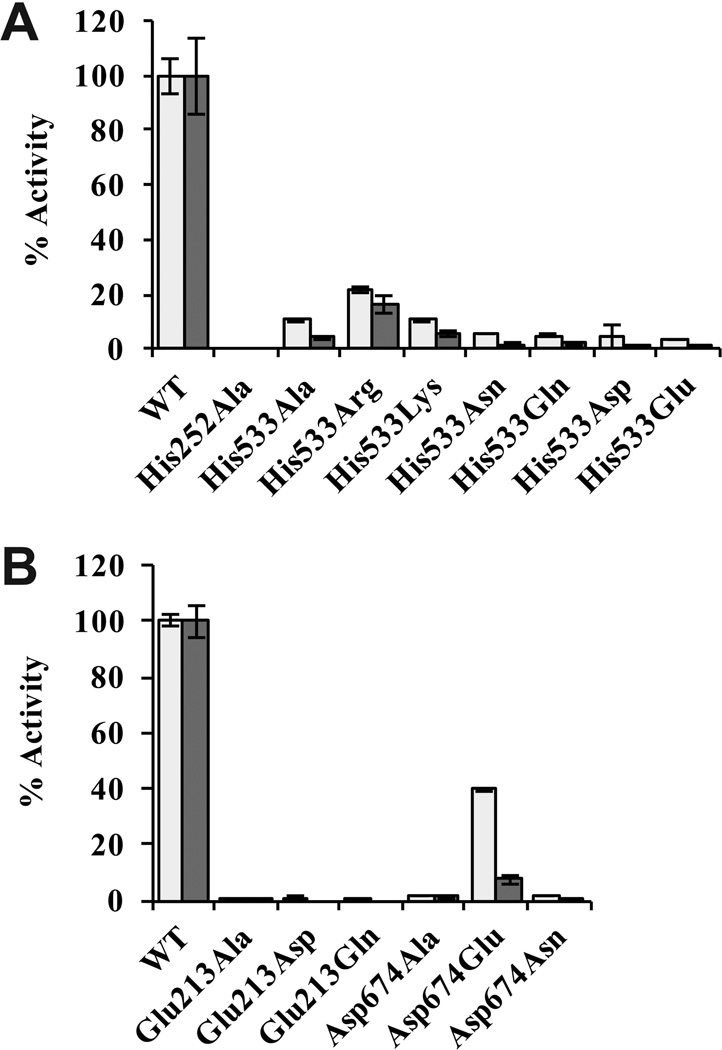

The His252Ala variant had no detectable activity in either direction of the reaction, even at higher substrate concentrations, longer reaction times, and higher enzyme concentrations. This confirmed that His252 is essential for activity, consistent with its proposed role as the site for the required phosphorylation step (Fig. 2A). The His533Ala variant retained weak activity in both directions, raising the possibility that phosphorylation of this residue is not a required step in the reaction mechanism as for the Pyrococcus ACD. Additional variants were created in which His533 was altered to the positively charged residues Arg and Lys, the neutral Asn and Gln, and negatively charged Asp and Glu. Although each of the His533 variants had less than 25% activity compared to wild-type enzyme, the level of activity corresponded to the charge of the replacement residue with positively charged residues having the most favorable effect (Fig. 2A).

FIGURE 2.

Activity of EhACD variants. Activity was determined in the acetyl-CoA forming direction (light gray) and in the acetate-forming direction (dark gray). Activities are represented as a percentage of the activity observed for the wild-type enzyme (100%). Assays were performed in triplicate and error bars represents standard deviation. (A) Activity of the His252 and His533 variants. (B) Activity of the Glu213 and Asp674 variants.

Apparent kinetic parameters were determined for the His533 variants in both directions of the reaction. In the acetate-forming direction, replacement of this residue with Arg was least deleterious, resulting in less than 10-fold reduction in kcat whereas replacement with Glu resulted in over 500-fold reduction (Table 1). Other replacements showed intermediate effects ranging from ~40- to ~80-fold reduced kcat. For the majority of the variants, the Km values for substrates showed only minor changes in this direction of the reaction (Table 1). The His533Ala variant showed the greatest reduction in the Km values for acetyl-CoA and ADP (4.3- and 3.8-fold, respectively); however, the magnitude of changes in Km may not large enough to be physiologically relevant. Replacement of His533 with a negatively charged residue had the strongest effect on the Km for Pi, with a 7.1-fold reduction in Km observed for the His533Asp variant and a 9.8-fold reduction for the His533Glu variant. Interestingly, replacement with Arg resulted in a nearly 12-fold reduced Km for Pi but replacement with Lys resulted in an approximately 2-fold increase in Km.

In the acetyl-CoA forming direction of the reaction, alterations at His533 had more severe effects on kinetic parameters (Table 2). The reductions in kcat ranged from approximately 40-fold to over 1300-fold and followed a pattern depending on the size and charge of the side chain. Replacement with the positively charged side chain of Arg or Lys or removal of the side chain by replacement with Ala to leave only a methyl group in place reduced kcat by less than 100-fold. Introduction of the uncharged residues Asn or Gln at this position resulted in ~160- to 230-fold reduced kcat. Although these were quite substantial effects, substitution with negatively charged Asp or Glu nearly eliminated catalytic activity by reducing kcat ~1000-fold or more. These results indicated that a negative charge at this position was very deleterious to catalysis, but that even a positive charge was not sufficient for proper activity and that His was strongly preferred.

Alterations at His533 also affected the Km for substrates (Table 2). In particular, all of the variants exhibited a reduced Km for acetate ranging from ~8-fold to ~45-fold. Only the His533Gln and His533Asp variants had strong reductions (18-fold) in Km for CoA. The effect on the Km for ATP ranged from ~5-fold to ~10-fold reduction. There was no discernable pattern to these effects based on size or charge of the replacement residue. Overall, His533 appeared to play a more significant role in catalysis than in substrate binding in both direction of the reaction. The necessity of this residue in providing sufficient ACD activity in vivo for survival and growth under different conditions is not known though.

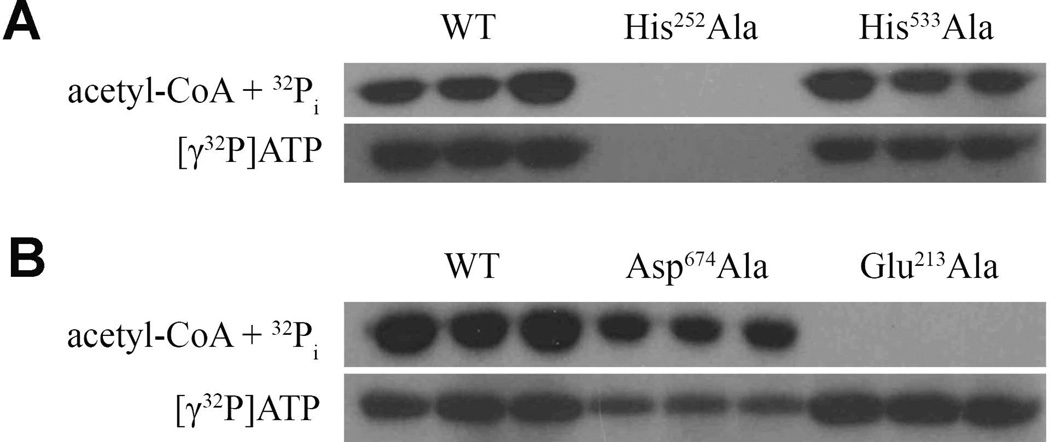

Our kinetic results suggested that His252 was essential for catalysis but His533 was not. As both of these residues were proposed to be sites of required phosphorylation events in the four-step mechanism of Brasen et al. (24), we examined phosphorylation of the wild-type enzyme and the His252Ala and His533Ala variants. To examine phosphorylation of EhACD in the acetyl-CoA forming and acetate-forming directions of the reaction, enzymes were incubated with [γ-32P]ATP or 32Pi + acetyl-CoA, respectively, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and the results were visualized by autoradiography.

Phosphorylation of wild-type EhACD was observed with [γ-32P]ATP or 32Pi + acetyl-CoA (Fig. 3), as expected. The His252Ala variant was not labeled by [γ-32P]ATP or by 32Pi + acetyl-CoA (Fig. 3A), consistent with a three-step mechanism involving a single phosphorylation event at this residue. In contrast, the His533Ala variant was labeled from both directions (Fig. 3A), suggesting this residue was not a site of phosphorylation as for the four-step mechanism proposed for PfACD.

FIGURE 3.

Isotopic labeling of EhACD. Enzymes were labeled with 32Pi + acetyl-CoA (top panels) or with [γ-32P]ATP (bottom panels). Assays were performed in triplicate. (A) Analysis of the His252Ala and His533Ala variants versus wild-type enzyme. (B) Analysis of the Glu213Ala and Asp674Ala variants versus wild-type enzyme.

Roles of Glu213 and Asp674

In SCS, Glu208α and Glu197β play a role in phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of the catalytic Hisα residue (20). Glu208α interacts with Hisα during phosphorylation and dephosphorylation in site I, and Glu197β stabilizes the position of this His residue during phosphorylation and dephosphorylation in site II (23). Glu208α is conserved among SCS and ACD, but Glu197β is replaced by Asp in ACD (Fig. 1). We altered the equivalent residues of EhACD to investigate whether they play a similar role. Replacement of Glu213 with Ala, Asp, or Gln reduced activity to ~1% or less than that of the wild-type enzyme (Fig. 2B), indicating the importance of this residue. The Asp674Ala and Asp674Asn variants had slightly higher activity than the other Asp674 variants and the Asp674Glu variant showed substantial activity, especially in the acetyl-CoA forming direction of the reaction (Fig. 2B). These results were consistent with the effects of corresponding changes in PfACD (24) and E. coli SCS (23).

Kinetic parameters determined for the Asp674 variants are shown in Table 3. Activity of the Glu213 EhACD variants was too low for reliable determination of kinetic parameters. The kcat values were reduced nearly two orders of magnitude in the acetyl-CoA forming direction for the Asp674Ala variant and even more for the Asp674Asn variant. Likewise, the Asp674Ala variant displayed a greater than 40-fold reduction in kcat in the acetate-forming direction and an even stronger reduction for the Asn variant. However, Glu substitution at Asp674 resulted in only ~5-fold decreased kcat in either direction of the reaction, suggesting that retention of the negative charge at this position was important for optimal in vitro enzymatic activity. The effects of these substitutions on Km values for substrates were reduced by ~5-fold or less for ATP and CoA in the direction of acetyl-CoA production and for acetyl-CoA, ADP, and Pi in the acetate-forming direction. The only major changes in Km were observed for the Asp674Ala and Asp674Asn variants, which showed greater than 10-fold reduction (Table 3).

We used isotopic labeling as described above to analyze the influence of Glu213 and Asp674 on phosphorylation of EhACD. The Glu213Ala variant was phosphorylated by [γ-32P]ATP in the acetyl-CoA forming direction to a similar level as observed for the wild-type enzyme, but no phosphorylation of this variant was observed with acetyl-CoA + 32Pi (Fig. 3B). These results were consistent with Glu213 playing a role in stabilization of Hisα in Site I as for Glu208α in SCS. The Asp674Ala variant was phosphorylated in both directions (Fig. 3B), although labeling was reduced, suggesting Asp674 may play a role in stabilization of Hisα in Site I but was not critical.

DISCUSSION

The catalytic Hisα is a defining feature of ACD enzymes

NDP-forming acyl-CoA synthetases participate in phosphoryl transfer through a catalytic His residue. This phosphorylation was first observed in the structure of E. coli SCS (31) and mutagenesis of this His residue in ATP citrate lyase abolished enzymatic activity (32,33). This catalytic His (designated here as Hisα) is conserved among SCS and ACD (Fig. 1). Alteration of His252 in EhACD effectively eliminated overall enzymatic activity as well as phosphorylation in either direction of the reaction (Figs. 2A and 3A), confirming its critical role in catalysis and consistent with its proposed role as the site of phosphorylation. Similar results were observed for the corresponding His in PfACD (24).

The Hisα residue is a defining feature of the NDP-forming acyl-CoA synthetase family and is especially important for distinguishing between ACD and protein acetyltransferases such as Pat from Salmonella (34). These acetyltransferases utilize acetyl-CoA for lysine acetylation of other proteins as part of the bacterial protein acetylation/deacetylation system, but cannot catalyze the full acyl-CoA synthetase reaction (34). Although they share strong homology with ACD and have the same domain arrangement (1), they lack the critical Hisα residue thus allowing them to be easily distinguished from acyl-CoA synthetases.

The necessity of Hisβ phosphorylation remains undetermined

A His residue in the β subunit (designated as Hisβ) is conserved among ACD sequences but is replaced by Arg in SCS, and other members of the superfamily (1). Brasen et al. (24) based their proposed four-step mechanism for PfACD on results in which they noted that the β subunit was phosphorylated and that alteration of Hisβ abolished enzymatic activity. Hisβ, conserved as His533 in EhACD, was found to be important but not essential as variants altered at this position displayed reduced activity (Fig. 2A and Tables 1 and 2) and the His533Ala variant was phosphorylated from both directions of the reaction (Fig. 3A). Thus, our results with EhACD contradict the proposed four-step mechanism but are consistent with a three-step mechanism similar to that for SCS.

Phosphorylation experiments with wild-type PfACD revealed that the α subunit was strongly labeled by both acetyl-CoA + 32Pi and [γ-32P]ATP but labeling of the β subunit was weaker and not immediate (24). In the absence of the β subunit, the α subunit was phosphorylated by acetyl-CoA + 32Pi as expected but was also phosphorylated by [γ-32P]ATP. In addition, the His71βAla variant showed good phosphorylation of the α subunit by [γ-32P]ATP. These results suggest that phosphorylation of Hisα from either direction may not require Hisβ under some conditions.

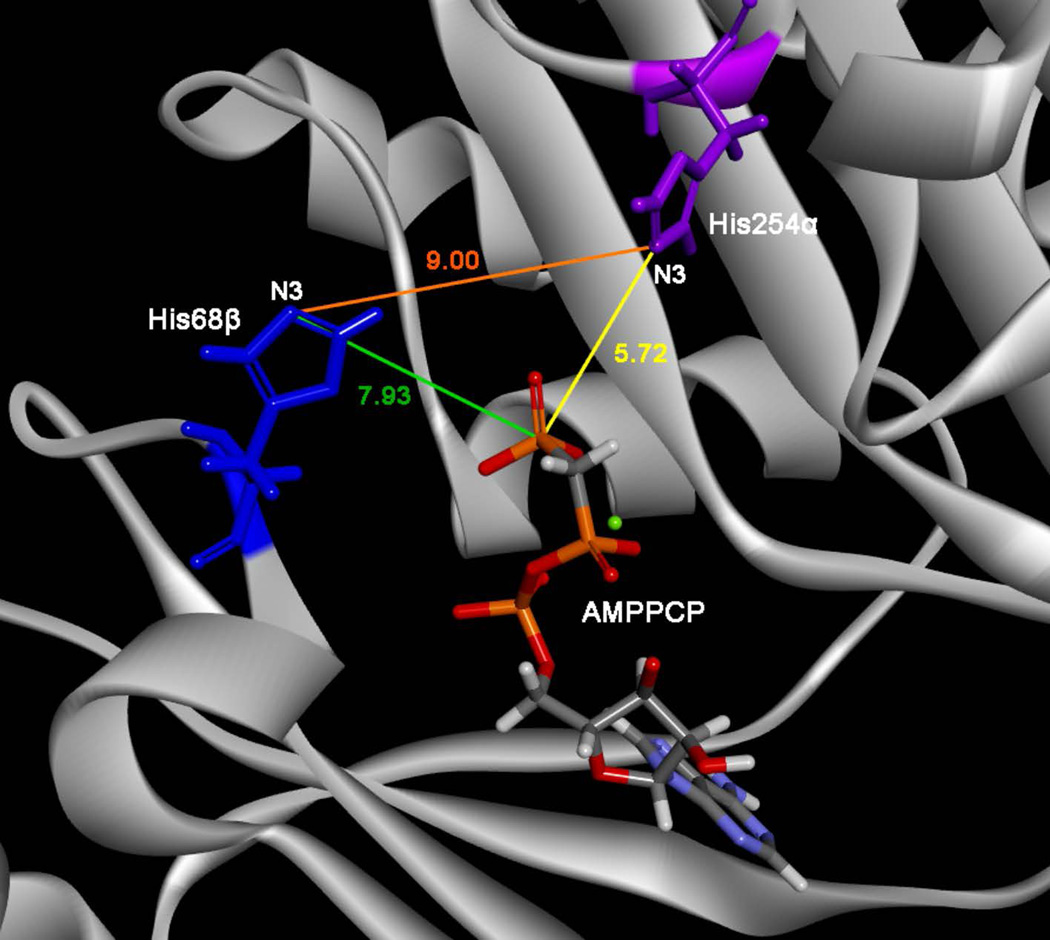

The recent structure of CKcACDI co-crystallized with the non-hydrolyzable ATP analog AMPPCP shows the catalytic Hisα residue oriented toward the β subunit (25). Distances of 8.7 Å, 6.7 Å, and 7.1 Å between the ADP analog AMPCP and His254α, AMPCP and His68β, and His254α and His68β, respectively, were reported. According to Weisse et al. (25) this supports the proposed four-step reaction mechanism for ACD (24) because the distance is too great for direct transfer of the phosphoryl group between Hisα and ATP and Hisβ must therefore be required for an intermediate phosphotransfer. However, these measurements may not accurately reflect the true distance to be spanned, as there is no accounting for the phosphate group that is transferred.

We have re-examined these structures and determined the distance between Hisα and AMPPCP rather than AMPCP, thus accounting for the transferred phosphate group. The distance between this terminal phosphate of AMPPCP and the Nε2 position of the imidazole ring of His254α is just 5.7 Å, shorter than the distances for phosphoryl transfer from ATP to Hisβ (7.9 Å) and then to His254α (9.0 Å) (Fig. 4). Distances calculated for the alternative Nδ1 position of His68β were also greater than the direct distance between AMPPCP and His254α (8.5 Å to His254α and 6.2 Å to the terminal phosphate group of AMPPCP). This suggests that direct rather than indirect phosphorylation of His254α by ATP may occur. Thus, these structures do not definitively distinguish between the three-step and four-step mechanisms but raise the possibility that both occur in ACD.

FIGURE 4.

Distance measurements in Site II of CKcACDI. The structure of CKcACDI crystallized with CoA and MgAMPPCP (PDB accession #4XZ3) showing Hisα in Site II of the active site was used for distance measurements. His254α is shown in purple and His68β is shown in blue. MgAMPPCP is colored by element: C (gray), P (orange), O (red), N (purple), H (light gray), and Mg (green). The distance between N3 of Hisα and P of AMPPCP (yellow line) is 5.7 Å. The distances between Hisα and Hisβ (orange line) and between Hisβ and P of AMPPCP (green line) are 9 Å and 7.9 Å, respectively.

Roles of Glu213 and Asp674 in phosphorylation of Hisα

E. coli SCS has two critical glutamate residues that play a role in phosphorylation of Hisα (20). When the swinging phosphohistidine loop is in the Site I position, Glu208α of SCS interacts directly with Hisα by hydrogen bonding with Nδ1 of the imidazole ring in order to leave Nε2 unprotonated and thus stabilizing the phosphohistidine (20). This same interaction between the equivalent Glu (designated here as Gluα) and Hisα was observed with CKcACDI (25). Glu197β in E. coli SCS was proposed to participate in stabilization of the phosphorylated Hisα when positioned at Site II (23). In the CKcACDI structure, the corresponding Asp209β (designated here as Aspβ) hydrogen bonds with the side chain of Thr255α and the backbone nitrogen of His254α when the phosphohistidine segment is pointing toward Site II (25).

As our results for Hisα and Hisβ suggest that EhACD and PfACD may follow slightly different mechanisms as far as the requirement for one versus two phosphoenzyme intermediates, we investigated the roles of Glu213 and Asp674, the equivalent residues to those that stabilize the swinging loop in Site I and Site II.

Alteration of Glu213 to Ala resulted in complete loss of activity and conservative replacement with Asp resulted in barely detectible activity. These results are consistent with those observed for variants altered at the corresponding Glu218α of PfACD (24) and suggest that ACD has very little flexibility at this position. The Glu213Ala EhACD variant was not phosphorylated by acetyl-CoA and 32Pi, consistent with the proposed role for Gluα in phosphorylation of Hisα in its Site I position near the acetyl-CoA and Pi binding site. Phosphorylation of this variant by [γ-32P]ATP even though the enzyme cannot catalyze the overall reaction suggests that Hisα may be phosphorylated in its Site II position but the phosphohistidine loop may be unable to “swing” back into the Site I position when Glu213 is absent. Alternatively, the Glu213Ala enzyme may be phosphorylated on a residue other than Hisα and this would be unaffected by Glu213. A similar result was observed in PfACD where replacement of Glu218α by Gln resulted in almost a complete loss of phosphorylation by 32Pi + acetyl-CoA, whereas some phosphorylation by [γ-32P]ATP was still observed (24).

Gluβ of SCS and the equivalent Aspβ of ACD are located in the ATP grasp domain. Alteration of the Aspβ residue Asp674 of EhACD to Ala or Asn resulted in drastic loss of activity. However, an Asp674Glu variant retained partial activity, suggesting the Asp carboxyl group is important for catalysis as expected based on the CKcACDI structure (25). However, if Aspβ of ACD functions similarly to Gluβ of SCS, the hydrogen bonding pattern must differ as Thr255α is conserved within all ACDs but is replaced by Ala in SCS (Fig. 1B). The Asp674Ala replacement in EhACD did not eliminate the ability of ACD to be phosphorylated from either direction, although phosphorylation by [γ-32P]ATP was reduced. This suggests that Aspβ of ACD plays a similar role as Gluβ of SCS in stabilizing Hisα in Site II but movement of the phosphohistidine loop and its positioning in Site I are unaffected.

Conclusions

Our biochemical analysis has demonstrated the importance of four residues involved in catalysis by E. histolytica ACD and their contributions to phosphorylation of the enzyme, a required step in the enzymatic mechanism. Our results with EhACD are consistent with a three-step mechanism analogous to that of SCS rather than the four-step mechanism involving two phosphoenzyme intermediates as proposed for PfACD by Brasen et al. (24). The dimeric EhACD has fused alpha and beta domains, resulting in a different subunit structure than PfACD and CKcACDI, both of which are heterotetramers with separate alpha and beta subunits. As a result, ACDs may fall into two classes based on subunit structure, one of which can directly transfer the phosphoryl group between Hisα and ATP and the other of which relies on a two-step transfer to bridge that distance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Kerry Smith (Clemson University) for beneficial discussions regarding this work. This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R15GM114759 to CIS) and a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship to CPJ.

ABBREVIATIONS

- acetyl-P

acetyl phosphate

- NDP

nucleoside diphosphate

- AMPPCP

[β,γ-methylene] ATP

- AMPCP

adenosine 5’-[α,β,methylene] diphosphate

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

CIS conceived and supervised the work and co-wrote the manuscript. CPJ designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the data, interpreted the results, and co-wrote the manuscript. KK performed enzyme kinetic determinations and data analysis for some enzyme variants. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sanchez LB, Galperin MY, Muller M. Acetyl-CoA synthetase from the amitochondriate eukaryote Giardia lamblia belongs to the newly recognized superfamily of acyl-CoA synthetases (Nucleoside diphosphate-forming) J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:5794–5803. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brasen C, Schonheit P. Unusual ADP-forming acetyl-coenzyme A synthetases from the mesophilic halophilic euryarchaeon Haloarcula marismortui and from the hyperthermophilic crenarchaeon Pyrobaculum aerophilum . Archives Microbiol. 2004;182:277–287. doi: 10.1007/s00203-004-0702-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schafer T, Schonheit P. Pyruvate metabolism of the hyperthermophilic archaebacterium Pyrococcus furiosus. Acetate formation from acetyl-CoA and ATP synthesis are catalyzed by an acetyl-CoA synthetase (ADP-forming) Archives Microbiol. 1991;155:366–377. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schafer T, Selig M, Schonheit P. Acetyl-CoA synthetase (ADP-forming) in archaea, a novel enzyme involved in acetate formation and ATP synthesis. Archives Microbiol. 1993;159:72–83. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmidt M, Schonheit P. Acetate formation in the photoheterotrophic bacterium Chloroflexus aurantiacus involves an archaeal type ADP-forming acetyl-CoA synthetase isoenzyme I. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2013;349:171–179. doi: 10.1111/1574-6968.12312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reeves RE, Warren LG, Susskind B, Lo HS. An energy-conserving pyruvate-to-acetate pathway in Entamoeba histolytica. Pyruvate synthase and a new acetate thiokinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1977;252:726–731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindmark DG. Energy metabolism of the anaerobic protozoon Giardia lamblia . Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1980;1:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(80)90037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones CP, Ingram-Smith C. Biochemical and kinetic characterization of the recombinant ADP-forming acetyl-CoA synthetase from the amitochondriate protozoan Entamoeba histolytica . Eukaryot. Cell. 2014;13:1530–1537. doi: 10.1128/EC.00192-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pineda E, Vazquez C, Encalada R, Nozaki T, Sato E, Hanadate Y, Nequiz M, Olivos-Garcia A, Moreno-Sanchez R, Saavedra E. Roles of acetyl-CoA synthetase (ADP-forming) and acetate kinase (PPi-forming) in ATP and PPi supply in Entamoeba histolytica . Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1860:1163–1172. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glasemacher J, Bock AK, Schmid R, Schonheit P. Purification and properties of acetyl-CoA synthetase (ADP-forming), an archaeal enzyme of acetate formation and ATP synthesis, from the hyperthermophile Pyrococcus furiosus . Eur. J. Biochem. 1997;244:561–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mai X, Adams MW. Purification and characterization of two reversible and ADP-dependent acetyl coenzyme A synthetases from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus . J. Bacteriol. 1996;178:5897–5903. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.20.5897-5903.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Musfeldt M, Selig M, Schonheit P. Acetyl coenzyme A synthetase (ADP forming) from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus: identification, cloning, separate expression of the encoding genes, acdAI and acdBI, in Escherichia coli, and in vitro reconstitution of the active heterotetrameric enzyme from its recombinant subunits. J. Bacteriol. 1999;181:5885–5888. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.18.5885-5888.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Awano T, Wilming A, Tomita H, Yokooji Y, Fukui T, Imanaka T, Atomi H. Characterization of two members among the five ADP-forming acyl coenzyme A (Acyl-CoA) synthetases reveals the presence of a 2-(Imidazol-4-yl)acetyl-CoA synthetase in Thermococcus kodakarensis . J. Bacteriol. 2014;196:140–147. doi: 10.1128/JB.00877-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shikata K, Fukui T, Atomi H, Imanaka T. A novel ADP-forming succinyl-CoA synthetase in Thermococcus kodakarensis structurally related to the archaeal nucleoside diphosphate-forming acetyl-CoA synthetases. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:26963–26970. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702694200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Musfeldt M, Schonheit P. Novel type of ADP-forming acetyl coenzyme A synthetase in hyperthermophilic archaea: heterologous expression and characterization of isoenzymes from the sulfate reducer Archaeoglobus fulgidus and the methanogen Methanococcus jannaschii . J. Bacteriol. 2002;184:636–644. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.3.636-644.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanchez LB, Muller M. Purification and characterization of the acetate forming enzyme, acetyl-CoA synthetase (ADP-forming) from the amitochondriate protist, Giardia lamblia . FEBS Lett. 1996;378:240–244. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01463-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brasen C, Urbanke C, Schonheit P. A novel octameric AMP-forming acetyl-CoA synthetase from the hyperthermophilic crenarchaeon Pyrobaculum aerophilum . FEBS Lett. 2005;579:477–482. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bailey DL, Fraser ME, Bridger WA, James MN, Wolodko WT. A dimeric form of Escherichia coli succinyl-CoA synthetase produced by site-directed mutagenesis. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;285:1655–1666. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fraser ME, James MN, Bridger WA, Wolodko WT. A detailed structural description of Escherichia coli succinyl-CoA synthetase. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;285:1633–1653. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fraser ME, James MN, Bridger WA, Wolodko WT. Phosphorylated and dephosphorylated structures of pig heart, GTP-specific succinyl-CoA synthetase. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;299:1325–1339. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joyce MA, Hayakawa K, Wolodko WT, Fraser ME. Biochemical and structural characterization of the GTP-preferring succinyl-CoA synthetase from Thermus aquaticus . Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2012;68:751–762. doi: 10.1107/S0907444912010852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joyce MA, Brownie ER, Hayakawa K, Fraser ME. Cloning, expression, purification, crystallization and preliminary X-ray analysis of Thermus aquaticus succinyl-CoA synthetase. Acta Crystallogr Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 2007;63:399–402. doi: 10.1107/S1744309107017113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fraser ME, Joyce MA, Ryan DG, Wolodko WT. Two glutamate residues, Glu 208 alpha and Glu 197 beta, are crucial for phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of the active-site histidine residue in succinyl-CoA synthetase. Biochemistry. 2002;41:537–546. doi: 10.1021/bi011518y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brasen C, Schmidt M, Grotzinger J, Schonheit P. Reaction mechanism and structural model of ADP-forming Acetyl-CoA synthetase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus: evidence for a second active site histidine residue. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:15409–15418. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710218200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weisse RH, Faust A, Schmidt M, Schonheit P, Scheidig AJ. Structure of NDP-forming acetyl-CoA synthetase ACD1 reveals a large rearrangement for phosphoryl transfer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2016;113:E519–E528. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518614113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. Multiple sequence alignment using ClustalW and ClustalX. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics. 2002;2 doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0203s00. Chapter 2, Unit 2 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Srere PA. Citryl-CoA. A substrate for the citrate-cleavage enzyme. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1963;73:523–525. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(63)90458-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lipmann F, Tuttle LC. A specific micromethod for determination of acyl phosphates. J. Biol. Chem. 1945;159:21–28. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rose IA, Grunberg-Manago M, Korey SF, Ochoa S. Enzymatic phosphorylation of acetate. J. Biol. Chem. 1954;211:737–756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolodko WT, Fraser ME, James MN, Bridger WA. The crystal structure of succinyl-CoA synthetase from Escherichia coli at 2.5-A resolution. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:10883–10890. doi: 10.2210/pdb1scu/pdb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fan F, Williams HJ, Boyer JG, Graham TL, Zhao H, Lehr R, Qi H, Schwartz B, Raushel FM, Meek TD. On the catalytic mechanism of human ATP citrate lyase. Biochemistry. 2012;51:5198–5211. doi: 10.1021/bi300611s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kanao T, Fukui T, Atomi H, Imanaka T. Kinetic and biochemical analyses on the reaction mechanism of a bacterial ATP-citrate lyase. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002;269:3409–3416. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Starai VJ, Escalante-Semerena JC. Identification of the protein acetyltransferase (Pat) enzyme that acetylates acetyl-CoA synthetase in Salmonella enterica . J. Mol. Biol. 2004;340:1005–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.