Abstract

Key points

Several different voltage‐dependent K+ (KV) channel isoforms are expressed in arterial smooth muscle cells (myocytes).

Vasoconstrictors inhibit KV currents, but the isoform selectivity and mechanisms involved are unclear.

We show that angiotensin II (Ang II), a vasoconstrictor, stimulates degradation of KV1.5, but not KV2.1, channels through a protein kinase C‐ and lysosome‐dependent mechanism, reducing abundance at the surface of mesenteric artery myocytes.

The Ang II‐induced decrease in cell surface KV1.5 channels reduces whole‐cell KV1.5 currents and attenuates KV1.5 function in pressurized arteries.

We describe a mechanism by which Ang II stimulates protein kinase C‐dependent KV1.5 channel degradation, reducing the abundance of functional channels at the myocyte surface.

Abstract

Smooth muscle cells (myocytes) of resistance‐size arteries express several different voltage‐dependent K+ (KV) channels, including KV1.5 and KV2.1, which regulate contractility. Myocyte KV currents are inhibited by vasoconstrictors, including angiotensin II (Ang II), but the mechanisms involved are unclear. Here, we tested the hypothesis that Ang II inhibits KV currents by reducing the plasma membrane abundance of KV channels in myocytes. Angiotensin II (applied for 2 h) reduced surface and total KV1.5 protein in rat mesenteric arteries. In contrast, Ang II did not alter total or surface KV2.1, or KV1.5 or KV2.1 cellular distribution, measured as the percentage of total protein at the surface. Bisindolylmaleimide (BIM; a protein kinase C blocker), a protein kinase C inhibitory peptide or bafilomycin A (a lysosomal degradation inhibitor) each blocked the Ang II‐induced decrease in total and surface KV1.5. Immunofluorescence also suggested that Ang II reduced surface KV1.5 protein in isolated myocytes; an effect inhibited by BIM. Arteries were exposed to Ang II or Ang II plus BIM (for 2 h), after which these agents were removed and contractility measurements performed or myocytes isolated for patch‐clamp electrophysiology. Angiotensin II reduced both whole‐cell KV currents and currents inhibited by Psora‐4, a KV1.5 channel blocker. Angiotensin II also reduced vasoconstriction stimulated by Psora‐4 or 4‐aminopyridine, another KV channel inhibitor. These data indicate that Ang II activates protein kinase C, which stimulates KV1.5 channel degradation, leading to a decrease in surface KV1.5, a reduction in whole‐cell KV1.5 currents and a loss of functional KV1.5 channels in myocytes of pressurized arteries.

Keywords: angiotensin II, KV channel, smooth muscle, vasoconstriction

Key points

Several different voltage‐dependent K+ (KV) channel isoforms are expressed in arterial smooth muscle cells (myocytes).

Vasoconstrictors inhibit KV currents, but the isoform selectivity and mechanisms involved are unclear.

We show that angiotensin II (Ang II), a vasoconstrictor, stimulates degradation of KV1.5, but not KV2.1, channels through a protein kinase C‐ and lysosome‐dependent mechanism, reducing abundance at the surface of mesenteric artery myocytes.

The Ang II‐induced decrease in cell surface KV1.5 channels reduces whole‐cell KV1.5 currents and attenuates KV1.5 function in pressurized arteries.

We describe a mechanism by which Ang II stimulates protein kinase C‐dependent KV1.5 channel degradation, reducing the abundance of functional channels at the myocyte surface.

Abbreviations

- 4‐AP

4‐aminopyridine

- Ang II

angiotensin II

- AT1

angiotensin II type 1 receptor

- Baf

bafilomycin A

- BIM

bisindolylmaleimide

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- CaV1.2

voltage‐dependent calcium channel

- DAG

diacylglycerol

- DAPI

4′,6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole, dihydrochloride

- K+

potassium

- KV

voltage‐dependent potassium channel

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PSS

physiological saline solution

- WGA

wheat germ agglutinin

Introduction

In small, resistance‐size arteries, intravascular pressure stimulates smooth muscle cell (myocyte) membrane depolarization, which activates voltage‐dependent calcium (CaV1.2) channels, leading to an increase in [Ca2+]i and vasoconstriction (Knot & Nelson, 1998; Davis & Hill, 1999). Arterial myocyte voltage‐dependent potassium (KV) channels are also activated by membrane depolarization, stimulating a negative feedback mechanism that opposes pressure‐induced depolarization and vasoconstriction (Nelson & Quayle, 1995; Yuan, 1995; Albarwani et al. 2003; Plane et al. 2005; Amberg & Santana, 2006). This mechanism sets an equilibrium of arterial contractility that can be further modulated by vasoconstrictors and vasodilators to regulate regional organ blood flow and systemic blood pressure.

The KV channels are a family of ∼40 proteins divided into 12 subclasses (KV1–KV12; Gutman et al. 2005). Several KV family members are expressed in myocytes, including KV1.2, KV1.5, KV2.1, KV2.2, KV7.1 and KV7.4 (Xu et al. 1999; Albarwani et al. 2003; Fountain et al. 2004; Yeung et al. 2007). The whole‐cell current amplitude (I) generated by a population of KV channels is equally dependent on single‐channel current (i), open probability (P O) and the number of channels at the cell surface (N) such that I = NP O i. P O is directly controlled by membrane potential, which modifies the conformation of the voltage‐sensing, arginine‐rich S4 segment in KV channel subunits (Nelson & Quayle, 1995; Jiang et al. 2003). Membrane potential also regulates the number (N) of plasma membrane‐resident KV1.5 channels in arterial myocytes (Kidd et al. 2015). These mechanisms control functional KV channel activity (NP O) in arterial myocytes (Nelson & Quayle, 1995; Kidd et al. 2015). Whether vasoregulatory stimuli other than membrane potential, including vasoconstrictors, also modulate arterial contractility by controlling the surface abundance of KV channels is unclear.

Angiotensin II (Ang II) is a vasoconstrictor produced by the renin–angiotensin system (Chappell, 2016). Angiotensin II binds angiotensin II type 1 (AT1) receptors in arterial myocytes, stimulating Gq/11, leading to phospholipase C activation (Berk & Corson, 1997; Higuchi et al. 2007; Wynne et al. 2009). Phospholipase C cleaves phosphoinositide 4,5‐bisphosphate into inositol triphosphate and diacylglycerol (DAG; Higuchi et al. 2007; Wynne et al. 2009). Diacylglycerol stimulates protein kinase C (PKC), which modulates a wide variety of ion channels in arterial myocytes, including CaV1.2, ATP‐sensitive K+ and Ca2+‐activated K+ channels (Hughes, 1995; Nelson & Quayle, 1995; Taguchi et al. 2000; Higuchi et al. 2007; Wynne et al. 2009; Leo et al. 2015). Angiotensin II also inhibits KV currents in arterial myocytes through a PKC‐dependent mechanism, leading to vasoconstriction (Rainbow et al. 2009). Whether Ang II reduces surface KV channel protein to inhibit KV currents in arterial myocytes is unclear.

Here, we tested the hypothesis that Ang II controls surface levels of KV1.5 and KV2.1 channels, the predominant KV isoforms expressed in rat mesenteric artery myocytes (Kidd et al. 2015). Data suggest that Ang II decreases total and surface KV1.5 protein in arterial myocytes through a PKC‐ and lysosome‐dependent mechanism, which reduces whole‐cell KV1.5 currents and KV1.5 function in pressurized arteries. In contrast, KV2.1 total and surface protein were unaltered by Ang II. These data suggest that Ang II controls surface KV1.5 protein abundance to modulate arterial contractility.

Methods

Ethical approval

All animal protocols were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, in accordance with the standards set by the National Institutes of Health. All experiments adhere to the ethical principles of The Journal of Physiology and comply with the journal's animal ethics checklist.

Preparation of tissues and isolated cells

Adult male Sprague–Dawley rats (200–250 g body mass) were purchased from Harlan Labs (Indianapolis, IN, USA) and fed ad libitum. Rats were administered CO2 in a specially designed housing chamber until immobile, to reduce any discomfort, before being killed by i.p. injection of sodium pentobarbitone (150 mg kg−1). The mesenteric vasculature was removed into ice‐cold physiological saline solution (PSS) that contained 112 mm NaCl, 6 mm KCl, 24 mm NaHCO3, 1.8 mm CaCl2, 1.2 mm MgSO4, 1.2 mm KH2PO4 and 10 mm glucose, gassed with 21% O2, 5% CO2 and 74% N2 to pH 7.4. Third‐ and fourth‐order mesenteric arteries (∼100–200 μm in diameter) were cleaned of adventitial tissue and dissected for experiments.

Individual myocytes were dissociated from arteries in isolation solution containing 55 mm NaCl, 80 mm sodium glutamate, 5.6 mm KCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 10 mm Hepes and 10 mm glucose, with pH adjusted to 7.4 using NaOH. Arteries were placed in prewarmed isolation solution containing 0.7 mg ml−1 papain, 1 mg ml−1 dithioerythreitol and 1 mg ml−1 bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 15–20 min at 37°C. Arteries were then quickly transferred to isolation solution containing 0.66 mg ml−1 collagenase F, 0.33 mg ml−1 collagenase H, 1 mg ml−1 BSA and 100 mm CaCl2 for 5–10 min at 37°C. Arteries were then washed with ice‐cold isolation solution and triturated with a fire‐polished glass Pasteur pipette to yield single myocytes.

Surface biotinylation

Arteries were incubated with 1 mg ml−1 each of EZ‐Link Sulfo‐NHS‐LC‐LC‐Biotin and EZ‐Link Maleimide‐PEG2‐Biotin (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in ice‐cold PSS for 1 h at 4°C. Unbound biotin was quenched with ice‐cold 100 mm glycine in PBS, then arteries were washed with ice‐cold PBS. Arteries were homogenized in ice‐cold radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing (mm): 50 Tris, 150 NaCl and 5 EDTA, with 0.1% SDS and 1% Triton‐X. Avidin beads in spin columns were used to separate the biotinylated surface protein. Biotinylated proteins were freed from the avidin beads by boiling in SDS buffer containing 5% 2‐mercaptoethanol. The whole volumes of either biotinylated or non‐biotinylated protein samples from each preparation were loaded into separate lanes of the same polyacrylamide gel for electrophoresis.

Western blotting

Arteries were homogenized in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer with 1× SDS and 5% 2‐mercaptoethanol. Arterial protein lysates were separated on 7.5% SDS–polyacrylamide gels, then transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked with 5% milk in Tris‐buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 (TBS‐T), then incubated with mouse monoclonal primary antibodies for KV1.5, KV2.1 (1:1000; NeuroMab, UC Davis, CA, USA) or actin (1:10000; Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) in blocking solution overnight at 4°C. Membranes were washed with TBS‐T before being incubated with horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated secondary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature, followed by a second wash with TBS‐T. Protein bands were developed using SuperSignal enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (Thermo Scientific) with a Kodak In Vivo Pro Imaging System. Band intensity was analysed using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Immunofluorescence

Isolated myocytes were plated on poly‐l‐lysine‐coated coverslips and maintained for 2 h in 30 mm K+ PSS alone, with Ang II or with Ang II in the presence of bisindolylmaleimide (BIM) before being fixed with formalin and incubated with Alexa 488‐conjugated wheat germ agglutinin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), a plasma membrane stain. Myocytes were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton‐X 100 and then blocked in 5% BSA before incubation with a mouse monoclonal KV1.5 primary antibody (1:100 in 0.5% BSA; NeuroMab, UC Davis) overnight at 4°C. Myocytes were washed and incubated with an Alexa 546‐conjugated donkey polyclonal secondary antibody to mouse IgG (1:100; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Coverslips were washed, then secured to microscope slides using 1:1 PBS:glycerol. Images were acquired using a laser scanning confocal microscope (LSM Pascal; Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY, USA). Alexa 488 and 546 were excited at 488 and 543 nm, respectively, with emission collected at 505–530 and ≥560 nm, respectively. Zeiss Pascal system software was used to calculate weighted pixel colocalization coefficient values. The RG2B plugin for ImageJ was used to isolate colocalization pixel data, with automatic selection intensity threshold values for the red and green channels. Colocalization data were expressed as the average of the corresponding red and green channels, producing an image displaying only colocalized pixels.

Arteries were incubated with 1 mg ml−1 each of EZ‐Link Sulfo‐NHS‐LC‐LC‐Biotin and EZ‐Link Maleimide‐PEG2‐Biotin (Thermo Scientific) in PSS for 1 h at 4°C. Unbound biotin was quenched with ice‐cold 100 mm glycine in PBS, and arteries were washed with ice‐cold PBS. Arteries were then postfixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS overnight. After dehydration, vessels were embedded in paraffin and 5‐μm‐thick sections cut using a microtome and mounted on slides. Sections were deparaffinized and blocked in 5% BSA before incubation with Alexa Fluor 546 streptavidin (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) and 4′,6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole, dihydrochloride (DAPI; Thermo Scientific) for 1 h at 37°C. Slides were then washed in PBS. Images were acquired using a laser‐scanning confocal microscope and a ×63 objective (Zeiss 710; Carl Zeiss). The DAPI and Alexa 546 were excited at 405 and 561 nm, respectively, with emission collected at ≤437 and ≥552 nm, respectively.

Patch‐clamp electrophysiology

Experiments were performed on isolated myocytes that were allowed to adhere to a glass coverslip for ∼15 min before experimentation. Whole‐cell currents were recorded using an Axopatch 200B amplifier and Clampex 10.4 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The KV currents were activated from a holding potential of −70 mV by applying stepwise depolarizations to between −60 and +50 mV. Bath solution contained (mm): 120 NaCl, 3 NaHCO3, 4.2 KCl, 1.2 KH2PO4, 0.5 MgCl2, 1.8 CaCl2, 10 glucose, 1 TEA and 10 Hepes, and pH was adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. Pipette solution contained (mm): 110 potassium gluconate, 30 KCl, 0.5MgCl2, 5 Na2ATP, 1 GTP, 10 EGTA and 5 Hepes, and pH was adjusted to 7.2 with KOH. The KV currents were digitized at 5 kHz and filtered at 1 kHz. Offline analysis was performed using Clampfit 10.4 (Molecular Devices).

Pressurized artery myography

Third‐order mesenteric artery segments (0.5–1 mm in length, 150–200 μm diameter) were denuded of endothelium by introducing air into the lumen for ∼1 min. Arteries were then cannulated at each end in a temperature‐controlled perfusion chamber (Living Systems Instrumentation, St Albans City, VT, USA) and continuously perfused with PSS. Intravascular pressure was modulated using an attached reservoir and monitored with a pressure transducer. Arterial diameter was measured using a closed‐circuit camera and IonWizard edge‐detection software (IonOptix, Westwood, MA, USA). Myogenic tone was calculated as: 100 × (1 − D Active/D Passive), where D Active is active arterial diameter and D Passive is arterial diameter in Ca2+‐free PSS supplemented with 5 mm EGTA.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using ANOVA with Newman–Keuls post hoc test using GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). All data are expressed as mean values ± SEM. A value of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Angiotensin II reduces plasma membrane KV1.5 channels via protein kinase C activation in arterial myocytes

Membrane potential controls both the surface abundance and total protein of KV1.5 channels in arterial myocytes (Kidd et al. 2015). Arterial isolation (2 h) in PSS containing 6 mm K+ at 37°C led to a decrease in KV1.5 total protein to ∼31% of that in fresh isolated (0 h) control arteries (Fig. 1 A and B). KV1.5 protein loss was prevented by maintenance in a PSS containing 30 mm K+, which depolarizes arterial myocytes to ∼−40 mV, a membrane potential similar to arteries at physiological intravascular pressure (Fig. 1 A and B; Knot & Nelson, 1998). In contrast, KV2.1 total protein was unaltered by arterial isolation (2 h) in PSS containing either 6 or 30 mm K+ (Fig. 1 A and B). These data are consistent with previous findings (Kidd et al. 2015).

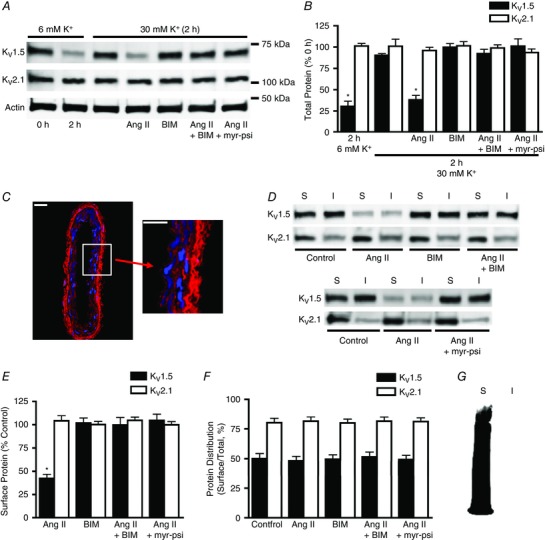

Figure 1. Angiotensin II reduces total and surface KV1.5 channel protein through protein kinase C (PKC) activation in mesenteric arteries.

A, representative Western blot images of total arterial KV1.5, KV2.1 and actin protein at 0 or 2 h in 6 mm K+ physiological saline solution (PSS), 30 mm K+ PSS, or 30 mm K+ PSS with angiotensin II (Ang II; 100 nm), bisindolylmaleimide (BIM; 10 μm), Ang II plus BIM, or a myristoylated PKC inhibitory peptide (myr‐psi; 100 μm). B, mean data. n = 6 for each. * P < 0.05 vs. 0 h. C, immunofluorescence of a section cut from a biotinylated mesenteric artery labelled with Alexa Fluor 546 streptavidin (red) and DAPI (blue), a nuclear stain. Scale bars represent 20 μm. D, representative Western blot images of arterial biotinylation samples illustrating surface (S) and intracellular (I) KV1.5 and KV2.1 following 2 h in 30 mm K+ alone (control) or in the presence of Ang II (100 nm), BIM (10 μm), Ang II plus BIM, or Ang II plus myr‐psi (100 μm). E, mean data for surface protein in conditions from experiments shown in C calculated as a percentage of control surface protein. n = 6 for each. * P < 0.05 vs. control. F, quantitative analysis of the relative cellular distribution of total KV1.5 and KV2.1 protein in conditions from C calculated as the percentage of total protein located at the cell surface. n = 6 for each. G, representative image of a Western blot probed with horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated avidin, illustrating that the avidin bead pull‐down procedure is 100% efficient and that no biotinylated proteins are present in the non‐biotinylated protein fraction.

We have previously demonstrated that biotin labels plasma membrane proteins, but not intracellular proteins, in rat resistance‐size cerebral arteries (Bannister et al. 2009). Arterial biotinylation has been used to measure the abundance and cellular distribution of surface and intracellular ion channels and auxiliary subunits in arterial myocytes (Adebiyi et al. 2010; Bannister et al. 2009, 2016; Crnich et al. 2010; Thomas‐Gatewood et al. 2011; Narayanan et al. 2013; Evanson et al. 2014; Nourian et al. 2014; Leo et al. 2015). To determine whether biotin permeates and labels proteins in the wall of rat mesenteric arteries, immunofluorescence was performed. Mesenteric arteries were exposed to biotin reagents, after which sections were cut and incubated with Alexa Fluor 546‐labelled streptavidin. Confocal imaging demonstrated that biotin labelled proteins throughout the wall of mesenteric arteries, indicating efficient labelling consistent with data in cerebral arteries (Fig. 1 C; Bannister et al. 2009).

The regulation of surface KV1.5 and KV2.1 protein by Ang II, a vasoconstrictor, was studied using arterial biotinylation in depolarized (30 mm K+) arteries. Angiotensin II (applied for 2 h) reduced both total and surface KV1.5 to ∼38 and ∼42% of control values, respectively (Fig. 1 A, B, D and E). In contrast, Ang II did not alter KV1.5 cellular distribution, which was calculated as the percentage of total KV1.5 protein present at the cell surface (Fig. 1 D and F). Angiotensin II also did not alter total or surface KV2.1 protein or KV2.1 cellular distribution (Fig. 1 A, B, D, E and F). To ensure that the avidin beads used to pull down biotinylated proteins were 100% efficient, Western blots were probed with horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated avidin. Horseradish peroxidase labelling was observed only in the surface lane and not in the intracellular lane, indicating that biotinylated proteins did not escape pull‐down and contaminate the non‐biotinylated protein fraction (Fig. 1 G). These data indicate that Ang II reduces both total and surface KV1.5 to a similar extent, but does not alter KV2.1 protein, in mesenteric arteries.

The binding of many vasoconstrictors, including Ang II, to their plasma membrane receptors stimulates Gq/11 in arterial myocytes (Berk & Corson, 1997). Gq/11 activates phospholipase C, leading to an elevation in DAG, which stimulates PKC (Berk & Corson, 1997). We tested the hypothesis that Ang II controls KV1.5 protein through a PKC‐mediated mechanism. Bisindolylmaleimide, a PKC‐specific inhibitor, blocked the Ang II‐induced decrease in both total and surface KV1.5 protein (Fig. 1 B–F). In contrast, BIM, when applied alone, did not alter total or surface KV1.5 protein or KV1.5 cellular distribution (Fig. 1 B–F). Bisindolylmaleimide also did not change total or surface KV2.1 when applied either alone or together with Ang II (Fig. 1 B–F). A membrane‐permeant, myristoylated PKC inhibitory peptide (Myr‐RFARKGALRQKNV) also blocked the Ang II‐induced reduction in both total and surface KV1.5 protein, but did not alter KV2.1 protein (Fig. 1 B–F). These data indicate that Ang II reduces total and surface KV1.5 protein through a PKC‐dependent mechanism in mesenteric arteries.

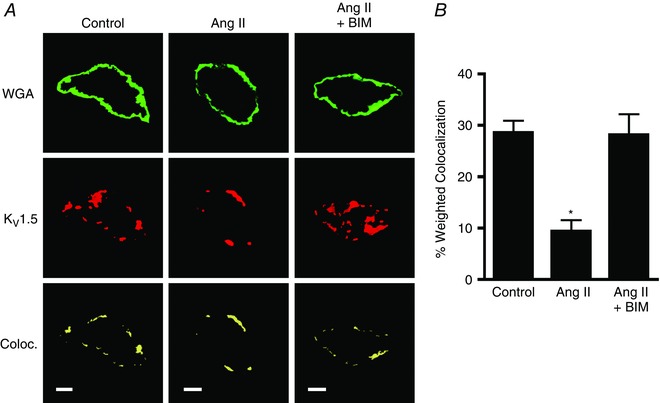

Immunofluorescence was performed to measure the regulation of KV1.5 localization by Ang II in isolated mesenteric artery myocytes. Angiotensin II reduced KV1.5 channel immunofluorescence colocalization with wheat germ agglutinin, a plasma membrane stain, from ∼29 to ∼9%, and this effect was prevented by BIM (Fig. 2 A and B). Taken together, these data suggest that Ang II‐induced PKC activation reduces surface and total KV1.5 channel protein in arterial myocytes.

Figure 2. Angiotensin II reduces surface KV1.5 channels in isolated arterial myocytes.

A, immunofluorescence images illustrating colocalization of KV1.5 (red) and wheat germ agglutinin (WGA, green) in isolated myocytes maintained for 2 h in 30 mm K+ alone (control), with Ang II (100 nm) or with Ang II plus BIM (10 μm). Scale bars represent 5 μm. B, quantitative analysis for the percentage of WGA pixels that colocalize with KV1.5. n = 8 for each. * P < 0.05 vs. control.

Angiotensin II stimulates KV1.5 channel degradation in arterial myocytes

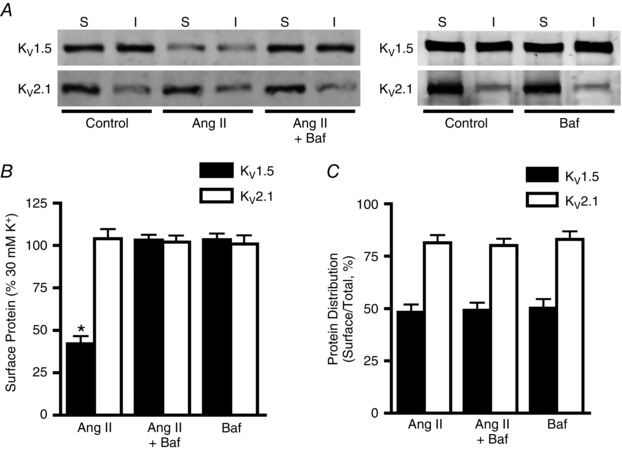

KV1.5 continuously recycles between the plasma membrane and the intracellular compartment in mesenteric artery myocytes (Kidd et al. 2015). Conceivably, Ang II might stimulate KV1.5 channel internalization, degradation or both in arterial myocytes. To test these possibilities, we studied regulation by bafilomycin A, a lysosomal v‐ATPase and, thus, lysosomal degradation inhibitor. Bafilomycin A prevented the Ang II‐mediated decrease in surface KV1.5 protein (Fig 3 A and B). In contrast, bafilomycin alone did not alter surface KV1.5 protein (Fig. 3 A and B). To determine whether Ang II altered channel internalization, effects on KV1.5 cellular distribution were calculated. Angiotensin II, bafilomycin, or Ang II applied in the presence of bafilomycin did not alter the relative cellular distribution of KV1.5 (Fig. 3 A and C). Total and surface KV2.1 were unaltered by Ang II, bafilomycin, or Ang II applied with bafilomycin (Fig. 3 A–C). These data suggest that Ang II stimulates lysosomal degradation of internalized KV1.5 protein, but indicate that Ang II does not stimulate KV1.5 internalization in arterial myocytes.

Figure 3. Angiotensin II stimulates KV1.5 lysosomal degradation in mesenteric arteries.

A, representative Western blot images illustrating surface and intracellular KV1.5 and KV2.1 protein after 2 h in 30 mm K+ (control), 30 mm K+ plus Ang II (100 nm) or 30 mm K+ plus Ang II and bafilomycin (Baf, 50 nm). B, mean data illustrating surface KV1.5 and KV2.1 protein normalized to control. n = 6 for each. * P < 0.05 vs. control. C, quantitative data showing relative cellular distribution of total KV1.5 and KV2.1 protein. n = 6 for each.

Angiotensin II‐induced PKC activation reduces KV1.5 current density in arterial myocytes

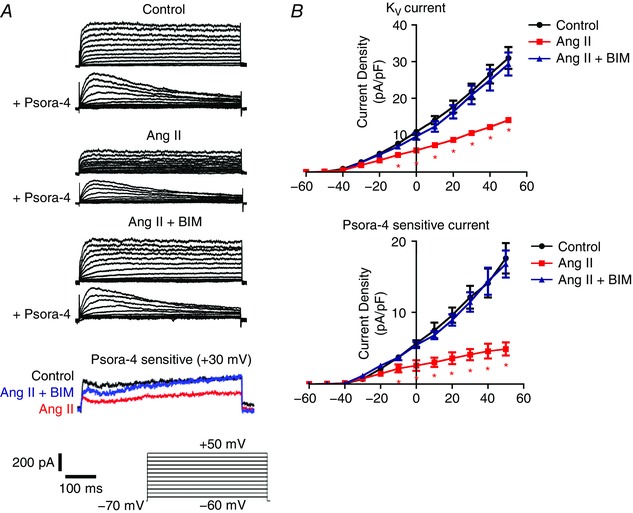

To determine the functional effect of an Ang II‐mediated reduction in surface KV1.5 channels, patch‐clamp electrophysiology was performed to measure KV1.5 current density in isolated arterial myocytes. Arteries were exposed to 30 mm K+ PSS alone (control), together with Ang II, or with both Ang II and BIM for 2 h, after which these agents were removed and myocytes isolated and used for electrophysiology. Patch‐clamp solutions were designed to isolate whole‐cell KV currents and reduce contamination from other current types, including large‐conductance Ca2+‐activated K+ channels. Angiotensin II treatment reduced mean KV current density from ∼31 to ∼14 pA pF−1, or to ∼45% (at +50 mV) of that in control myocytes (Fig. 4 A and B). Involvement of KV1.5 channels was investigated using Psora‐4, a KV1.5 open channel blocker that inhibits currents activated during voltage pulses (Fig. 4 A; Marzian et al. 2013). Psora‐4 reduced mean KV current density (measured at the end of voltage pulses) in control myocytes by ∼18 pA pF−1 (at +50 mV; Fig. 4 A and B). In contrast, in Ang II‐treated myocytes, Psora‐4 reduced mean KV current density by ∼5 pA pF−1 (at +50 mV; Fig. 4 A and B). The Psora‐4‐induced reduction in KV current in Ang II‐treated myocytes was ∼28% of that in control myocytes (at +50 mV; Fig. 4 A and B). Bisindolylmaleimide prevented the Ang II‐induced reduction in both whole‐cell KV and Psora‐4‐sensitive KV currents (Fig. 4 A and B). These data illustrate that Ang II‐induced PKC activation reduces surface KV1.5 channel protein, which decreases both whole‐cell and KV1.5 current density in arterial myocytes.

Figure 4. Angiotensin II reduces whole‐cell KV and KV1.5 currents in arterial myocytes.

A, representative whole‐cell KV current recordings in myocytes isolated from arteries that had been maintained for 2 h in 30 mm K+ (control), 30 mm K+ plus Ang II (100 nm) or 30 mm K+ plus Ang II and BIM (10 μm). Currents were measured in myocytes immediately following isolation. B, mean current–voltage relationships for whole‐cell (top, n = 7 for each) and Psora‐4‐sensitive currents (bottom, n = 7 for each). * P < 0.05 vs. control.

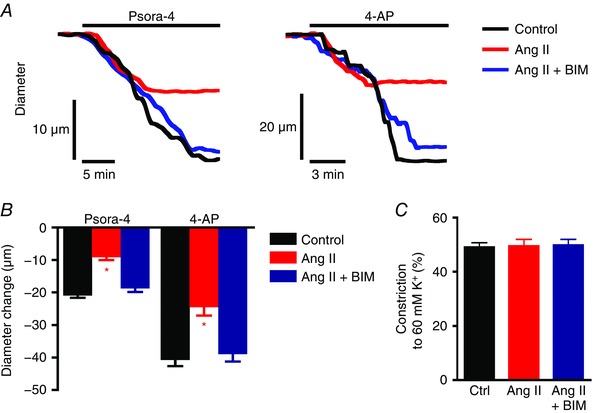

Angiotensin II inhibits functional KV1.5 channel activity in pressurized arteries

To investigate the significance of an Ang II‐induced reduction in surface KV1.5 channels in arterial myocytes, myography was performed on pressurized, endothelium‐denuded myogenic third‐order mesenteric arteries. Arteries were exposed to 30 mm K+ PSS alone, with Ang II, or with both Ang II and BIM for 2 h. These conditions were then removed, arteries were pressurized to 80 mmHg in PSS containing 6 mm K+, and myogenic tone and acute vasoconstriction in response to Psora‐4 or 4‐aminopyridine (4‐AP), a broad KV channel inhibitor, were measured.

In myogenic arteries that were maintained in 30 mm K+ PSS (control), Psora‐4 or 4‐AP stimulated acute mean vasoconstrictions of ∼20.6 and ∼40.4 μm, respectively (Fig. 5 A and B). In contrast, Psora‐4 or 4‐AP contracted arteries that had been exposed to Ang II by ∼8.8 and ∼24.2 μm, respectively, or ∼42.7 and ∼59.9% of that in control arteries (Fig. 5 A and B). Bisindolylmaleimide blocked the Ang II‐induced reduction in Psora‐4‐ and 4‐AP‐mediated vasoconstriction (Fig. 5 A and B). In contrast, vasoconstriction in response to 60 mm K+ was not altered by Ang II (Fig. 5 C). Myogenic tone was also similar in all three conditions: control, 16.2 ± 0.86% (n = 6); Ang II, 15.0 ± 0.83% (n = 6); and Ang II plus BIM, 15.8 ± 0.73% (n = 6). These data suggest that Ang II‐induced PKC activation reduces the abundance of functional surface KV1.5 channels in arterial myocytes.

Figure 5. Angiotensin II reduces functional KV1.5 channel activity in pressurized arteries.

A, representative diameter traces for vasoconstriction stimulated by Psora‐4 (100 nm) or 4‐aminopyridine (4‐AP, 1 mm) at an intravascular pressure of 80 mmHg for arteries maintained for 2 h in 30 mm K+ alone (control) or plus Ang II (100 nm) or plus Ang II with BIM (10 μm). Initial arterial diameters before application of Psora‐4 or 4‐AP were normalized. B, mean data illustrating vasoconstriction stimulated by Psora‐4 or 4‐AP. n = 6 for each. Mean passive diameters were similar for arteries used in each data set (P > 0.05 for each, e.g. mean passive diameter for control arteries was 231.6 ± 4.7 μm, for Ang II‐treated arteries 228.0 ± 4.1 μm, and for arteries treated with Ang II and BIM 232.8 ± 4.8 μm). * P < 0.05 vs. control. C, mean data for vasoconstrictive response to 60 mm K+ PSS at 80 mmHg intravascular pressure. n = 6 for each.

Discussion

Angiotensin II inhibits KV currents in arterial myocytes, but the mechanisms involved are unclear. Here, we show that Ang II reduces the surface abundance of KV1.5 channels in mesenteric artery myocytes. Angiotensin II‐induced PKC activation stimulates KV1.5 channel degradation, which reduces whole‐cell KV currents in myocytes and attenuates KV function in myogenic arteries. In contrast, Ang II does not modulate surface KV2.1 channel abundance in arterial myocytes. Thus, our data suggest that Ang II selectively decreases surface KV1.5 protein, thereby reducing KV current density in arterial myocytes and inhibiting vasodilatation by these channels, leading to vasoconstriction.

Our data here and a previous study show that membrane potential and Ang II both regulate the surface abundance of KV1.5 channel protein in arterial myocytes (Kidd et al. 2015). Angiotensin II binds to AT1 receptors, which are coupled to Gq/11 proteins that stimulate phospholipase C in vascular myocytes (Berk & Corson, 1997). Phospholipase C activation elevates DAG, a PKC activator (Berk & Corson, 1997). Protien kinase C directly phosphorylates myosin light chain kinase, which then phosphorylates myosin light chain, promoting an interaction between actin and myosin, resulting in vasoconstriction (Gallagher et al. 1997). Data suggest that Ang II stimulates degradation of internalized KV1.5 channels through a PKC‐dependent mechanism. Bisindolylmaleimide (a selective PKC inhibitor) or a myristoylated, cell‐permeant PKC inhibitory peptide prevented the Ang II‐mediated reduction in surface and total KV1.5 channels. Three isoforms of PKC are present in vascular myocytes; PKCα and PKCβ are DAG and Ca2+ dependent, and PKCε is stimulated by DAG (Newton, 1995). Angiotensin II‐mediated PKCε activation reduces whole‐cell KV currents in arterial myocytes, and PKCε inhibition reduces Ang II‐induced vasoconstriction in mesenteric artery rings (Rainbow et al. 2009). In contrast to Ang II, membrane depolarization inhibits KV1.5 channel degradation via CaV1.2 channel activation (Kidd et al. 2015). Here, to study Ang II regulation of KV1.5 channels in myocytes, experiments were performed in arteries depolarized with PSS containing 30 mm K+, which depolarizes myocytes to ∼−40 mV, a membrane potential similar to arteries at physiological intravascular pressure (Knot & Nelson, 1998). Although the kinases involved have not been identified, membrane potential and Ang II are likely to control KV1.5 degradation through different mechanisms, as PKC stimulates KV1.5 degradation and CaV1.2 channel activation inhibits KV1.5 degradation. Angiotensin II‐induced KV1.5 degradation described here may be attributable to PKCε, whereas depolarization‐induced KV1.5 protection may occur as a result of Ca2+‐dependent PKCs or other Ca2+‐activated kinases. Future studies should be designed to test these hypotheses.

Bafilomycin, an inhibitor of lysosomal degradation, prevented the Ang II‐induced reduction in surface and total KV1.5 protein, but did not change KV1.5 relative cellular distribution in arterial myocytes. These data suggest that Ang II stimulates KV1.5 channel degradation, but does not activate KV1.5 internalization or recycling in arterial myocytes. KV1.5 channels continuously recycle in mesenteric artery myocytes, suggesting that Ang II‐induced PKC activation shuttles internalized channels into the lysosomal degradation pathway (Kidd et al. 2015). In contrast, KV2.1 channels do not recycle over the same time course, which may be one reason why Ang II does not stimulate degradation of these proteins. KV1.5 channels recycle through Rab4‐ and Rab11‐dependent pathways in HL‐1 mouse atrial myocytes, H9c2 rat cardiomyoblasts and HEK293 cells expressing recombinant KV1.5, suggesting involvement of recycling and early endosomes (McEwen et al. 2007; Zadeh et al. 2008). Oxidative stress increased colocalization of internalized KV1.5 channels with the chaperone heat shock protein 70, which targets proteins for ubiquitylation and degradation, in HL‐1 cells (Pratt et al. 2010; Svoboda et al. 2012). Oxyhaemoglobin stimulates KV1.5 channel internalization through a tyrosine kinase‐dependent mechanism in rabbit cerebral artery myocytes (Ishiguro et al. 2006). Angiotensin II‐induced regulation of KV1.5 transcription is highly unlikely to explain the mechanism we describe here. Arteries were exposed to Ang II for 2 h, which is a period of time unlikely to alter KV1.5 protein through transcription. Supporting this conclusion are our data showing that bafilomycin blocked the Ang II‐mediated reduction in KV1.5 protein. We have also previously shown that arterial depressurization for 3 h reduces KV1.5 protein by >60% without any change in KV1.5 mRNA, indicating that protein processing and transcription can occur independently in arterial myocytes (Kidd et al. 2015).

Several studies have investigated trafficking pathways that modulate ion channel abundance at the cell surface in arterial myocytes. α2δ‐1, an auxiliary subunit of voltage‐dependent Ca2+ channels, is required for trafficking of CaV1.2 to the cell surface in cerebral artery myocytes (Bannister et al. 2009). Myocyte surface expression of both CaV1.2 and α2δ‐1 subunits is increased in rats with genetic hypertension, elevating CaV1.2 current density and producing a non‐inactivating current that stimulates vasoconstriction (Bannister et al. 2012). The surface abundance of TRPM4, a melastatin transient receptor potential channel, is increased by PKCδ in cerebral artery myocytes (Crnich et al. 2010). Nitric oxide stimulates rapid trafficking of large‐conductance Ca2+‐activated K+ (BK) channel β1 subunits to the myocyte surface to activate BK channels and produce vasodilatation in cerebral arteries (Leo et al. 2014). Serotonin, a neurotransmitter and vasoconstrictor, reduced surface KV1.5 channels, as determined using immunofluorescence, in pulmonary artery myocytes (Cogolludo et al. 2006). Physiological intravascular pressure, via depolarization‐induced voltage‐dependent Ca2+ channel activity, stimulates KV1.5 channel surface expression in mesenteric artery myocytes (Kidd et al. 2015). Here, we show that Ang II reduces surface KV1.5, the predominant KV channel subtype, in mesenteric artery myocytes (Kidd et al. 2015). Myocytes of other vascular beds may express different populations of KV channel subtypes (Kerr et al. 2001; Albarwani et al. 2003; Amberg & Santana, 2006; Zhong et al. 2010; Jepps et al. 2011). As such, the regulatory pathway described here for KV1.5 may be more relevant in some vessels than others. KV1.5 and KV1.2 form functional heteromultimeric channels in rat mesenteric artery myocytes and rabbit portal vein myocytes (Kerr et al. 2001; Plane et al. 2005). Angiotensin II‐mediated modulation of surface KV1.5 may alter KV channel heteromultimer formation and abundance in arterial myocytes. Collectively, these studies indicate that multiple, distinct trafficking pathways, with differing time courses and mechanisms, modulate the surface abundance and activity of a variety of ion channels in arterial myocytes to regulate contractility.

The use of Psora‐4, a KV1.5 channel inhibitor, in patch‐clamp electrophysiology and myography experiments supports our biochemical data showing that Ang II regulates KV currents and vasocontractility by modulating KV1.5 surface expression. Psora‐4 is a psoralen compound that blocks both KV1.3 and KV1.5 channels at low nanomolar concentrations, but is a less effective blocker of other KV1 family members (Vennekamp et al. 2004). There are few to no data suggesting the expression or function of KV1.3 in contractile arterial myocytes (Cidad et al. 2010; Cheong et al. 2011). Psoralens also weakly inhibit KV2, Kir2.1, BK and CaV1.2 channels in arterial myocytes, but at concentrations 25–150 times higher than used here (Nelson & Quayle, 1995; Vennekamp et al. 2004; Schmitz et al. 2005). Arteries treated with Ang II developed the same amount of myogenic tone as control arteries despite the reduction in KV1.5 function measured with Psora‐4 or 4‐AP. The reasons for this are unclear, but one explanation is that Ang II modulates the surface abundance of other ion channels that control arterial contractility, leading to no net effect on myogenic tone. Vasoconstriction stimulated by 60 mm K+ was unaltered, indicating that Ang II does not cause non‐specific alteration of contractility and does not appear to modify voltage‐dependent Ca2+ channel protein or activity. Data indicate that the Ang II‐induced reduction in KV1.5 surface protein inhibits KV currents and arterial contractility regulation by KV1.5 channels.

In summary, we show that Ang II selectively stimulates degradation of KV1.5 channels to reduce functional KV1.5 channel surface abundance in mesenteric artery myocytes. Angiotensin II‐mediated PKC activation stimulates lysosomal degradation of internalized KV1.5 channels, reducing protein available for recycling. Through this mechanism, Ang II inhibits whole‐cell KV1.5 currents, thereby reducing their functional modulation of arterial contractility.

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

M.W.K. designed and performed the experiments, conducted the data analysis, prepared the figures and wrote the manuscript. S.B. performed the experiments, prepared the figures and wrote the manuscript. J.H.J. conceived the project, designed and directed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All persons designated as authors qualify for authorship, and all those who qualify for authorship are listed.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL67061, 094378 and HL110347 to J.H.J.

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs M. Dennis Leo and Padmapriya Muralidharan for comments on the manuscript.

References

- Adebiyi A, Zhao G, Narayanan D, Thomas‐Gatewood CM, Bannister JP & Jaggar JH (2010). Isoform‐selective physical coupling of TRPC3 channels to IP3 receptors in smooth muscle cells regulates arterial contractility. Circ Res 106, 1603–1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albarwani S, Nemetz LT, Madden JA, Tobin AA, England SK, Pratt PF & Rusch NJ (2003). Voltage‐gated K+ channels in rat small cerebral arteries: molecular identity of the functional channels. J Physiol 551, 751–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amberg GC & Santana LF (2006). KV2 channels oppose myogenic constriction of rat cerebral arteries. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 291, C348–C356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannister JP, Adebiyi A, Zhao G, Narayanan D, Thomas CM, Feng JY & Jaggar JH (2009). Smooth muscle cell α2δ‐1 subunits are essential for vasoregulation by CaV1.2 channels. Circ Res 105, 948–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannister JP, Bulley S, Leo MD, Kidd MW & Jaggar JH (2016). Rab25 influences functional CaV1.2 channel surface expression in arterial smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 310, C885–C893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannister JP, Bulley S, Narayanan D, Thomas‐Gatewood C, Luzny P, Pachuau J & Jaggar JH (2012). Transcriptional upregulation of α2δ‐1 elevates arterial smooth muscle cell voltage‐dependent Ca2+ channel surface expression and cerebrovascular constriction in genetic hypertension. Hypertension 60, 1006–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk BC & Corson MA (1997). Angiotensin II signal transduction in vascular smooth muscle: role of tyrosine kinases. Circ Res 80, 607–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell MC (2016). Biochemical evaluation of the renin‐angiotensin system: the good, bad, and absolute? Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 310, H137–H152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong A, Li J, Sukumar P, Kumar B, Zeng F, Riches K, Munsch C, Wood IC, Porter KE & Beech DJ (2011). Potent suppression of vascular smooth muscle cell migration and human neointimal hyperplasia by KV1.3 channel blockers. Cardiovasc Res 89, 282–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cidad P, Moreno‐Domínguez A, Novensá L, Roqué M, Barquín L, Heras M, Pérez‐García MT & López‐López JR (2010). Characterization of ion channels involved in the proliferative response of femoral artery smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 30, 1203–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cogolludo A, Moreno L, Lodi F, Frazziano G, Cobeño L, Tamargo J & Perez‐Vizcaino F(2006). Serotonin inhibits voltage‐gated K+ currents in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells: role of 5‐HT2A receptors, caveolin‐1, and KV1.5 channel internalization. Circ Res 98, 931–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crnich R, Amberg GC, Leo MD, Gonzales AL, Tamkun MM, Jaggar JH & Earley S (2010). Vasoconstriction resulting from dynamic membrane trafficking of TRPM4 in vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 299, C682–C694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MJ & Hill MA (1999). Signalling mechanisms underlying the vascular myogenic response. Physiol Rev 79, 387–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evanson KW, Bannister JP, Leo MD & Jaggar JH (2014). LRRC26 is a functional BK channel auxiliary γ subunit in arterial smooth muscle cells. Circ Res 115, 423–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fountain SJ, Cheong A, Flemming R, Mair L, Sivaprasadarao A & Beech DJ (2004). Functional up‐regulation of KCNA gene family expression in murine mesenteric resistance artery smooth muscle. J Physiol 556, 29–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher PJ, Herring BP & Stull JT (1997). Myosin light chain kinases. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 18, 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman GA, Chandy KG, Grissmer S, Lazdunski M, McKinnon D, Pardo LA, Robertson GA, Rudy B, Sanguinetti MC, Stuhmer W & Wang X (2005). International Union of Pharmacology. LIII. Nomenclature and molecular relationships of voltage‐gated potassium channels. Pharmacol Rev 57, 473–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi S, Ohtsu H, Suzuki H, Shirai H, Frank GD & Eguchi S (2007). Angiotensin II signal transduction through the AT1 receptor: novel insights into mechanisms and pathophysiology. Clin Sci (Lond) 112, 417–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes AD (1995). Calcium channels in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Vasc Res 32, 353–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiguro M, Morielli AD, Zvarova K, Tranmer BI, Penar PL & Wellman GC (2006). Oxyhemoglobin‐induced suppression of voltage‐dependent K+ channels in cerebral arteries by enhanced tyrosine kinase activity. Circ Res 99, 1252–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jepps TA, Chadha PS, Davis AJ, Harhun MI, Cockerill GW, Olesen SP, Hansen RS & Greenwood IA (2011). Downregulation of KV7.4 channel activity in primary and secondary hypertension. Circulation 124, 602–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Ruta V, Chen J, Lee A & MacKinnon R (2003). The principle of gating charge movement in a voltage‐dependent K+ channel. Nature 423, 42–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr PM, Clément‐Chomienne O, Thorneloe KS, Chen TT, Ishii K, Sontag DP, Walsh MP & Cole WC (2001). Heteromultimeric KV1.2‐KV1.5 channels underlie 4‐aminopyridine‐sensitive delayed rectifier K+ current of rabbit vascular myocytes. Circ Res 89, 1038–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd MW, Leo MD, Bannister JP & Jaggar JH (2015). Intravascular pressure enhances the abundance of functional KV1.5 channels at the surface of arterial smooth muscle cells. Sci Signal 8, ra83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knot HJ & Nelson MT (1998). Regulation of arterial diameter and wall [Ca2+] in cerebral arteries of rat by membrane potential and intravascular pressure. J Physiol 508, 199–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leo MD, Bannister JP, Narayanan D, Nair A, Grubbs JE, Gabrick KS, Boop FA & Jaggar JH (2014). Dynamic regulation of β1 subunit trafficking controls vascular contractility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111, 2361–2366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leo MD, Bulley S, Bannister JP, Kuruvilla KP, Narayanan D & Jaggar JH (2015). Angiotensin II stimulates internalization and degradation of arterial myocyte plasma membrane BK channels to induce vasoconstriction. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 309, C392–C402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzian S, Stansfeld PJ, Rapedius M, S Rinné, Nematian‐Ardestani E, Abbruzzese JL, Steinmeyer K, Sansom MS, Sanguinetti MC, Baukrowitz T & Decher N (2013). Side pockets provide the basis for a new mechanism of Kv channel‐specific inhibition. Nat Chem Biol 9, 507–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen DP, Schumacher SM, Li Q, Benson MD, Iñiguez‐Lluhí JA, Van Genderen KM & Martens JR (2007). Rab‐GTPase‐dependent endocytic recycling of KV1.5 in atrial myocytes. J Biol Chem 282, 29612–29620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan D, Bulley S, Leo MD, Burris SK, Gabrick KS, Boop FA & Jaggar JH (2013). Smooth muscle cell transient receptor potential polycystin‐2 (TRPP2) channels contribute to the myogenic response in cerebral arteries. J Physiol 591, 5031–5046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MT & Quayle JM (1995). Physiological roles and properties of potassium channels in arterial smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 268, C799–C822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton AC (1995). Protein kinase C: structure, function, and regulation. J Biol Chem 270, 28495–28498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nourian Z, Li M, Leo MD, Jaggar JH, Braun AP & Hill MA (2014). Large conductance Ca2+‐activated K+ channels (BKCa) α‐subunit splice variants in resistance arteries from rat cerebral and skeletal muscle vasculature. PLoS One 9, e98863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plane F, Johnson R, Kerr P, Wiehler W, Thorneloe K, Ishii K, Chen T & Cole W (2005). Heteromultimeric KV1 channels contribute to myogenic control of arterial diameter. Circ Res 96, 216–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt WB, Morishima Y, Peng HM & Osawa Y (2010). Proposal for a role of the Hsp90/Hsp70‐based chaperone machinery in making triage decisions when proteins undergo oxidative and toxic damage. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 235, 278–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainbow RD, Norman RI, Everitt DE, Brignell JL, Davies NW & Standen NB (2009). Endothelin‐I and angiotensin II inhibit arterial voltage‐gated K+ channels through different protein kinase C isoenzymes. Cardiovasc Res 83, 493–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz A, Sankaranarayanan A, Azam P, Schmidt‐Lassen K, Homerick D, Hansel W & Wulff H (2005). Design of PAP‐1, a selective small molecule KV1.3 blocker, for the suppression of effector memory T cells in autoimmune diseases. Mol Pharmacol 68, 1254–1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svoboda LK, Reddie KG, Zhang L, Vesely ED, Williams ES, Schumacher SM, O'Connell RP, Shaw R, Day SM, Anumonwo JM, Carroll KS & Martens JR (2012). Redox‐sensitive sulfenic acid modification regulates surface expression of the cardiovascular voltage‐gated potassium channel KV1.5. Circ Res 111, 842–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi K, Kaneko K & Kubo T (2000). Protein kinase C modulates Ca2+‐activated K+ channels in cultured rat mesenteric artery smooth muscle cells. Biol Pharm Bull 23, 1450–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas‐Gatewood C, Neeb ZP, Bulley S, Adebiyi A, Bannister JP, Leo MD & Jaggar JH (2011). TMEM16A channels generate Ca2+‐activated Cl− currents in cerebral artery smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 301, H1819–H1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vennekamp J, Wulff H, Beeton C, Calabresi PA, Grissmer S, Hansel W & Chandy KG (2004). KV1.3‐blocking 5‐phenylalkoxypsoralens: a new class of immunomodulators. Mol Pharmacol 65, 1364–1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynne BM, Chiao CW & Webb RC (2009). Vascular smooth muscle cell signalling mechanisms for contraction to angiotensin II and endothelin‐1. J Am Soc Hypertens 3, 84–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C, Lu Y, Tang G & Wang R (1999). Expression of voltage‐dependent K+ channel genes in mesenteric artery smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Gatrointest Liver Physiol 277, G1055–G1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung SY, Pucovsky V, Moffatt JD, Saldanha L, Schwake M, Ohya S & Greenwood IA (2007). Molecular expression and pharmacological identification of a role for KV7 channels in murine vascular reactivity. Br J Pharmacol 151, 758–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan XJ (1995). Voltage‐gated K+ currents regulate resting membrane potential and [Ca2+]i in pulmonary arterial myocytes. Circ Res 77, 370–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zadeh AD, Xu H, Loewen ME, Noble GP, Steele DF & Fedida D (2008). Internalized KV1.5 traffics via Rab‐dependent pathways. J Physiol 586, 4793–4813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong XZ, Abd‐Elrahman KS, Liao CH, El‐Yazbi AF, Walsh EJ, Walsh MP & Cole WC (2010). Stromatoxin‐sensitive, heteromultimeric KV2.1/KV9.3 channels contribute to myogenic control of cerebral arterial diameter. J Physiol 588, 4519–4537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]