Abstract

Background and Purpose

We investigated potential disparities in the use of prophylactic seizure medications in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage.

Methods

Review of multicenter electronic health record (EHR) data with simultaneous prospective data recording. EHR data were retrieved from HealthLNK, a multi-center EHR repository in Chicago, IL, from 2006–2012 ("multicenter cohort"). Additional data were prospectively coded (“single center cohort”) from 2007 through 2015.

Results

The multicenter cohort was comprised of 3,422 patients from four HealthLNK centers. Use of levetiracetam varied by race/ethnicity (P=0.0000008), with whites nearly twice as likely as blacks to be administered levetiracetam (OR 1.71, 95% CI 1.43 – 2.05, P<0.0001). In the single center cohort (N=450), hematoma location, older age, depressed consciousness, larger hematoma volume, and no alcohol abuse, and race/ethnicity were associated with levetiracetam administration (P<=0.04). Whites were nearly twice as likely as blacks to receive levetiracetam (OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.25 – 2.89, P=0.002), however, the association was confounded by history of hypertension, higher blood pressure on admission, and deep hematoma location. Only hematoma location was independently associated with levetiracetam administration (P<0.00001), rendering other variables, including race/ethnicity, non-significant.

Conclusions

While multicenter EHR data showed apparent racial/ethnic disparities in the use of prophylactic seizure medications, a more complete single center cohort found the apparent disparity to be confounded by the clinical factors of hypertension and hematoma location. Disparities in care after intracerebral hemorrhage are common, however, administrative data may lead to the discovery of disparities that are confounded by detailed clinical data not readily available in EHRs.

Keywords: intracerebral hemorrhage, disparities, outcomes, critical care

Seizures are a noted complication of intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). Although prophylactic phenytoin was previously recommended,1 revised guidelines no longer recommended prophylactic seizure medications2, 3 after phenytoin4 and seizure medications generally5 were associated with worse outcomes. Yet, levetiracetam continues to be administered to nearly 40% of patients with acute ICH nationwide,6 suggesting that clinicians often consider their use to be appropriate.

Disparities in care for patients with ischemic stroke are well described,7 however, there are few data on disparities in care for patients with ICH.8 We hypothesized that there are racial/ethnic disparities in the use of prophylactic seizure medications.

Materials and Methods

Multi-center cohort

We utilized the Chicago HealthLNK Data Repository (”HealthLNK”). The logistics, procedures and patient privacy issues have been previously described.9 Data from 2007 – 2012 were available from Loyola, Rush, and Northwestern Universities, and the University of Chicago. Patients with diagnostic code 431 (Intracerebral hemorrhage) from the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Ed were identified.

Single-center cohort

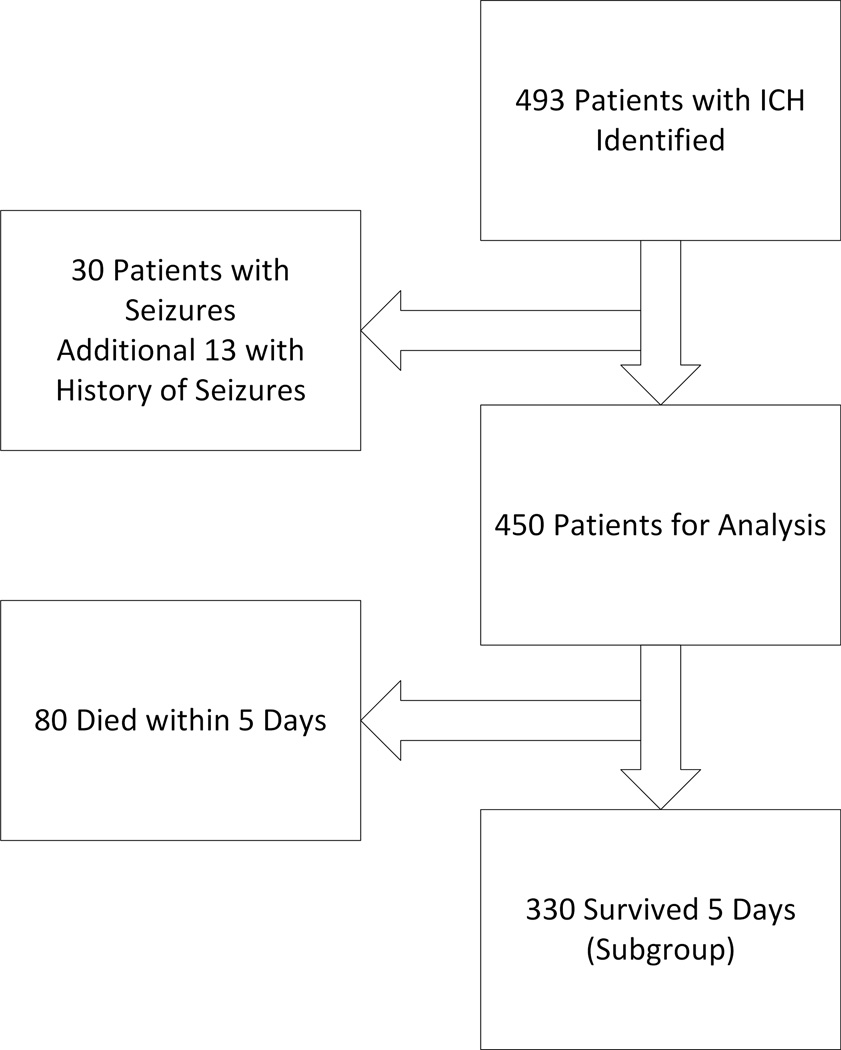

The Northwestern University Brain Attack Registry (NUBAR) has enrolled patients with ICH since 2007 (Figure).4

Figure.

Organizational chart of the prospective cohort.

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

The study was approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board. Patients or a legally authorized representative were asked for written consent.; Patients who died or were not consentable were enrolled under a waiver.

Statistical Analysis

Normally distributed data were compared with analysis of variance, categorical data were analyzed with chi-squared and non-parametric data were analyzed with the Mann-Whitney U or Kruskal-Wallis H. Logistic regression set prophylactic levetiracetam as the dependent variable using forward selection. The analysis was repeated in patients who survived at least five days after ICH.10

Results

Multi-center Cohort

The multicenter cohort was composed of 3,422 patients, of whom 1,777 (51.9%) were male with a mean age of 57.7 +/− 15.9 years. Race/ethnicity and levetiracetam were associated (Table 1). Whites were almost twice as likely as blacks to be administered levetiracetam (OR 1.71, 95% CI 1.43 – 2.05, P<0.0001). Age and sex were not associated with levetiracetam administration.

Table 1.

Race/ethnicity and levetiracetam use were associated (P=0.0000008) in the multi-center cohort.

| Race | No Levetiracetam (N=2386) | Levetiracetam (N=748) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Native American | 12 (1) | 4 (1) |

| 2 Asian | 81 (3) | 23(3) |

| 3 Black | 1041 (44) | 239 (32) |

| 4 Hispanic or Latino | 78 (3) | 16 (2) |

| 5 Pacific Islander | 5 (0) | 6 (0) |

| 6 White | 1051 (44) | 413 (56) |

| 7 Declined | 51 (2) | 23 (3) |

| 8 Other | 67 (3) | 24(3) |

Data are N(%). Data do not sum to 3,422 due to missing data in some patients on race/ethnicity.

Single Center Cohort

Among 450 patients with spontaneous ICH (Table 2), compared to blacks, whites had lower systolic (185 +/− 43 versus 176 +/− 38 mm Hg, P=0.03) and diastolic blood pressures (102 +/− 29 versus 90 +/− 25 mm Hg, P=0.00001) on admission. Compared to blacks (N=163, 51%), whites (N=138, 43%) and Hispanics (N=19, 6%) were less likely to have a prior history of hypertension (P=0.00007).

Table 2.

Demographics of the 450 patients in the prospective cohort stratified by prophylactic levetiracetam use. Lobar hematoma, depressed Glasgow Coma Scale, older age, and known alcohol abuse were associated with levetiracetam administration. In multivariate analysis, only lobar hematoma was associated with levetiracetam administration.

| Variable | Levetiracetam | No Prophylactic Levetiracetam |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 138 | 312 | |

| Age | 67.7 +/− 15.23 | 64.5 +/− 14.11 | 0.03 |

| Women | 77 (57) | 159 (51) | 0.2 |

| Race/Ethnicity Missing | 2 (1) | 3 (1) | 0.3 |

| American Indian | 0 | 2 (1) | |

| Asian | 3 (2) | 5 (2) | |

| Black | 45 (33) | 148 (47) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 11 (8) | 24 (8) | |

| Native Pacific Islander | 2 (1) | 9 (3) | |

| White | 75 (55) | 121 (39) | |

| Hematoma location, lobar | 77 (59) | 73 (25) | <0.00001 |

| Deep | 46 (46) | 156 (54) | |

| Infratentorial | 6 (5) | 47 (16) | |

| Other | 9 (6) | 36 (11) | |

| GCS, 13–15 | 71 (52) | 196 (63) | 0.007 |

| 5–12 | 54 (39) | 77 (25) | |

| 3–4 | 11 (9) | 39 (12) | |

| Hematoma >= 30 mL | 54 (38) | 77 (25) | 0.08 |

| Intraventricular hemorrhage | 68 (50) | 151 (48) | 0.9 |

| Supratentorial hematoma | 128 (94) | 258 (83) | 0.02 |

| Age >= 80 years | 36 (26) | 48 (15) | 0.01 |

| ICH Score | 2 [1 – 3] | 1 [0 – 2.5] | 0.01 |

| Previous ICH | 8 (6) | 8 (3) | 0.2 |

| Previous ischemic stroke | 17 (13) | 35 (11) | 0.8 |

| History of coronary disease | 23 (17) | 48 (15) | 0.3 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 16 (12) | 27 (9) | 0.5 |

| Historical hypertension | 93 (68) | 242 (78) | 0.08 |

| Alcohol abuse | 4 (3) | 31 (10) | 0.04 |

| Historical dementia | 4 (3) | 7 (2) | 0.9 |

| Warfarin use | 12 (8) | 39 (13) | 0.5 |

Data are N(%), median [Q1 – Q3] or mean +/− SD

Factors associated with levetiracetam administration are shown in Table 2. Whites were nearly twice as likely as blacks to be administered levetiracetam (OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.25 – 2.89, P=0.002). In multivariate analysis, hematoma location entered first and rendered other variables non-significant. Similar results were found for patients who survived at least 5 days and patients with seizures.

Discussion

Whites were approximately twice as likely as blacks to receive levetiracetam. This apparent disparity was confounded by hematoma location, with whites more likely to have lobar hematomas, the clinical factor most closely linked to a higher risk of seizures.11

Although prophylactic seizure medications are no longer recommended after ICH,2, 3 their use remains common.6 The use of levetiracetam in patients with a lobar hematoma is rational, if not strictly compliant with the guidelines, one of many scenarios where clinical practice deviates from evidence-based recommendations.12 Disparities in prophylactic phenytoin were not examined because we discontinued its use in 2009.

Associations between seizure medications and outcomes were not evaluated. Adverse events associated with phenytoin are relatively easy to detect.4 Levetiracetam has fewer side effects than phenytoin, and any adverse effects on cognition or behavior are likely to be detected only in patients already considered to have a “good outcome.”13 Other validated scores of health-related quality of life and cognition could be a useful adjunct.14, 15

In sum, we found that an apparent disparity in the use of seizure medications was confounded by hematoma location. There are likely to be other disparities found in the care of patients with ICH, some of which are confounded.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

This project was supported by grant number K18HS023437 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality to Dr. Naidech. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Dr. Toledo: None

Dr Prabhakaran: Research Support from NIH/NINDS: NS084288-01A1 (3/2014–present; PI); 1U10NS086608- 01 (10/2013–present, PI) and the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute: AD-1310-07237 (10/2014–present, PI).

Dr. Holl reports research support from Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality HS000078-18, and past support from NICHD Project Number 275201200007I-2-27500010-1.

Disclosures:

Dr. Prabhakaran reports he is on the editorial board for Current Atherosclerosis Reports, Publishing Royalties from UpToDate on Cryptogenic Stroke

Dr. Naidech: publishing royalties from Thieme (Hemorrhage and Ischemic Stroke)

We acknowledge the centers who contributed medication data to HealthLNK, Loyola University Medical Center, Northwestern Medicine, Bill Galanter, MD at University of Illinois Medical Center, Bala Hota, MD at Rush University Medical Center, and David Meltzer MD, PhD at the University of Chicago Medical Center.

Footnotes

The statistical analysis was performed by AN

References

- 1.Broderick J, Connolly S, Feldmann E, D H, Kase C, Kreiger D, et al. Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage in adults. 2007 update. Stroke. 2007;38:2001–2023. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.183689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hemphill JC, 3rd, Greenberg SM, Anderson CS, Becker K, Bendok BR, Cushman M, et al. Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: A guideline for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke. 2015;46:2032–2060. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morgenstern LB, Hemphill JC, 3rd, Anderson C, Becker K, Broderick JP, Connolly ES, Jr, et al. Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. A guideline for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke. 2010;41:2108–2129. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3181ec611b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naidech AM, Garg RK, Liebling S, Levasseur K, Macken MP, Schuele SU, et al. Anticonvulsant use and outcomes after intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2009;40:3810–3815. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.559948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Messe SR, Sansing LH, Cucchiara BL, Herman ST, Lyden PD, Kasner SE. Prophylactic antiepileptic drug use is associated with poor outcome following ich. Neurocrit Care. 2009;11:38–44. doi: 10.1007/s12028-009-9207-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sheth KN, Martini SR, Moomaw CJ, Koch S, Elkind MS, Sung G, et al. Prophylactic antiepileptic drug use and outcome in the ethnic/racial variations of intracerebral hemorrhage study. Stroke. 2015;46:3532–3535. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cruz-Flores S, Rabinstein A, Biller J, Elkind MS, Griffith P, Gorelick PB, et al. Racial-ethnic disparities in stroke care: The american experience: A statement for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke. 2011;42:2091–2116. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3182213e24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faigle R, Bahouth MN, Urrutia VC, Gottesman RF. Racial and socioeconomic disparities in gastrostomy tube placement after intracerebral hemorrhage in the united states. Stroke. 2016;47:964–970. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.011712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kho AN, Cashy JP, Jackson KL, Pah AR, Goel S, Boehnke J, et al. Design and implementation of a privacy preserving electronic health record linkage tool in chicago. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015;22:1072–1080. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocv038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Battey TW, Falcone GJ, Ayres AM, Schwab K, Viswanathan A, McNamara KA, et al. Confounding by indication in retrospective studies of intracerebral hemorrhage: Antiepileptic treatment and mortality. Neurocrit Care. 2012;17:361–366. doi: 10.1007/s12028-012-9776-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vespa PM, O'Phelan K, Shah M, Mirabelli J, Starkman S, Kidwell C, et al. Acute seizures after intracerebral hemorrhage: A factor in progressive midline shift and outcome. Neurology. 2003;60:1441–1446. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000063316.47591.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, Wu AW, Wilson MH, Abboud PA, et al. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282:1458–1465. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naidech AM, Beaumont JL, Berman M, Francis B, Liotta E, Maas MB, et al. Dichotomous "Good outcome" Indicates mobility more than cognitive or social quality of life. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:1654–1659. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sangha RS, Caprio FZ, Askew R, Corado C, Bernstein R, Curran Y, et al. Quality of life in patients with tia and minor ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2015;85:1957–1963. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naidech AM, Beaumont JL, Rosenberg NF, Maas MB, Kosteva AR, Ault ML, et al. Intracerebral hemorrhage and delirium symptoms: Length of stay, function and quality of life in a 114-patient cohort. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:1331–1337. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201307-1256OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]