Abstract

The Hippo pathway is a critical regulator of tissue size, and aberrations in pathway regulation lead to cancer. MST1/2 and LATS1/2 kinases comprise the core of the pathway that, in association with adaptor proteins SAV and MOB, functions in a sequential manner to phosphorylate and inhibit the transcription factors YAP and TAZ. Here we identify mammalian MARK family members as activators of YAP/TAZ. We show that depletion of MARK4 in MDA‐MB‐231 breast cancer cells results in the loss of nuclear YAP/TAZ and decreases the expression of YAP/TAZ targets. We demonstrate that MARK4 can bind to MST and SAV, leading to their phosphorylation, and that MARK4 expression attenuates the formation of a complex between MST/SAV and LATS, which depends on the kinase activity of MARK4. Abrogation of MARK4 expression using siRNAs and CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing attenuates the proliferation and migration of MDA‐MB‐231 cells. Our results show that MARK4 acts as a negative regulator of the Hippo kinase cassette to promote YAP/TAZ activity and that loss of MARK4 restrains the tumorigenic properties of breast cancer cells.

Keywords: breast cancer, Hippo pathway, MARK4, TAZ, YAP

Subject Categories: Cancer, Signal Transduction

Introduction

The size of an organ in multicellular organisms is determined by an intricate balance of cell proliferation, apoptosis, stem cell self‐renewal, and differentiation. Intrinsic and extrinsic factors tightly regulate these processes, which are essential for normal embryonic development and tissue homeostasis, and aberrations in their regulation lead to organ growth defects or tumorigenesis. The Hippo pathway has emerged as a major signaling pathway with evolutionarily conserved roles in regulating tissue growth and organ size 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. The major effectors of the pathway are the related transcriptional co‐activators, YAP and TAZ, which, in association with various transcription factors such as TEADs, induce a growth promoting gene expression program to regulate cell proliferation, apoptosis, self‐renewal, and differentiation 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. The core of the Hippo pathway in vertebrates is composed of the conserved Ser/Thr kinases, MST1/2, and LATS1/2 that associate with the adaptor proteins, SAV and MOB, to restrict YAP/TAZ transcriptional activity. Specifically, MST1/2 phosphorylates and activates LATS1/2, which in turn directly phosphorylates YAP/TAZ to promote cytoplasmic sequestration and subsequent degradation through the proteasomal pathway 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. Although this kinase cascade is considered as the core of the Hippo pathway, multiple upstream regulators can act at many levels to modulate YAP/TAZ 2, 4, 7. Initial studies on Hippo pathway regulation mainly focused on the role of intrinsic factors such as RASSFs, cell polarity, junctional complexes, and changes in cell shape and size as major determinants of Hippo‐YAP activity 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15. However, it is now clear that the Hippo pathway also responds to environmental cues such as G‐protein‐coupled receptors, nutrient availability particularly glucose, and metabolic pathways 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22.

Given the growth promoting effects of YAP/TAZ, disruptions of YAP/TAZ activity are commonly associated with pathological conditions, especially cancer 3, 8, 23, 24. Diverse genetic mouse models have shown that loss of Hippo core components such as MST1/2 or SAV that restrict YAP/TAZ activity leads to overgrowth phenotypes and ultimately cancer 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30. Furthermore, in vitro and in vivo models of tumorigenesis have shown that increased expression of YAP and TAZ is sufficient to transform normal epithelial cells, induce epithelial‐mesenchymal transition, cooperate with other proto‐oncogenes to bypass oncogene addiction, and increase cancer stem cell content of tumors 3, 8, 23, 24. Hence, a better understanding of the modulators of YAP/TAZ activity is crucial for understanding tumorigenesis.

Previously, we used a LUMIER‐based protein interaction screen 31, 32, 33, and identified βPIX, as a novel upstream regulator of the Hippo pathway 34. Here, we complemented this physical map, with a functional cDNA overexpression screen using a TEAD‐luciferase reporter to identify genes that modulate YAP/TAZ transcriptional activity. We identified MAP/microtubule affinity‐regulating kinase (MARK) family members as potent activators of YAP/TAZ activity. MARKs were originally identified based on their ability to phosphorylate microtubule regulating proteins Tau and MAPs 35. They belong to the larger AMPK family that includes AMPK, the master regulator of cellular energy balance 36, 37, 38, 39. Several AMPK family members have recently been shown to be important regulators of Hippo pathway 18, 19, 20, 40. MARK1–4 are the mammalian orthologs of the Drosophila Par‐1 kinase and have evolutionarily conserved roles in embryonic development, asymmetric cell division, and cell polarity regulation 36, 37, 41, 42.

Here we show that MARK family members activate a YAP/TAZ responsive luciferase reporter, and concordantly, that MARK4 deletion in breast cancer cells leads to loss of nuclear YAP/TAZ and inhibits activation of YAP/TAZ target genes. Furthermore, we show that abrogation of MARK4 expression either by siRNAs or CRISPR/Cas9‐mediated knockout attenuates the tumorigenic properties of breast cancer cells including cell proliferation and cell migration. Mechanistically, we show that MARK4 binds to the Hippo core components MST1/2 and SAV and subsequently phosphorylates both. Phosphorylation of MST1/2 and SAV by MARK4 leads to disruption of complex formation between MST/SAV and their downstream targets, LATS kinases, hence blocking YAP/TAZ inactivation by the Hippo kinase cassette.

Results

Identification of MARK4 as a regulator of YAP/TAZ activity

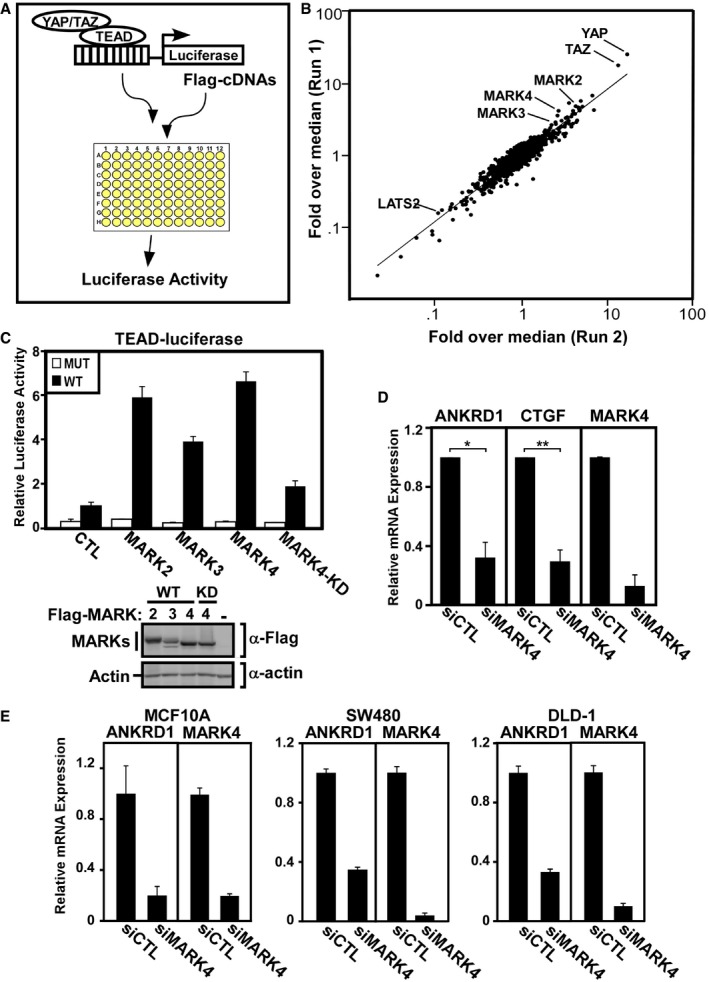

To identify novel Hippo pathway modulators, we undertook a functional screen that examined the effect of cDNA overexpression on transcriptional outcome using a YAP/TAZ‐dependent transcriptional reporter, TEAD‐luciferase, which harbors multiple TEAD binding sites located upstream of firefly luciferase 43. HEK293T cells were transfected with cDNAs from an augmented version of the previously described libraries 32, 33 that encode Flag‐tagged mouse and/or human proteins comprised of diverse signaling‐associated domains (Fig 1A). TEAD‐reporter activity in cells transfected with each cDNA was determined by measuring luciferase activity and normalized for transfection efficiency with a coexpressed β‐galactosidase reporter gene. Comparisons of duplicate runs revealed excellent correlation (Fig 1B) and identified both known positive regulators, such as YAP and TAZ as well as negative regulators, such as LATS2. Among the top hits that enhanced TEAD‐luciferase transcriptional activity were three members of the microtubule affinity‐regulating kinases (MARK) family, MARK2, MARK3, and MARK4. We confirmed that transient overexpression of MARK2, MARK3, and MARK4 potently activated YAP/TAZ transcriptional reporter activity (Fig 1C). YAP/TAZ regulate the expression of diverse target genes, and thus, as a complement to overexpression using a transcriptional reporter, we next examined the effect of the loss of expression of MARKs on endogenous target genes. For this, we used the triple‐negative breast cancer cell line, MDA‐MB‐231, which displays constitutive TAZ/YAP activity 34, 44, 45. Abrogation of expression of MARK4 using a pool of siRNAs (Fig 1D) or three out of four individual siRNAs (Fig EV1A), markedly attenuated the expression of the well‐characterized TAZ/YAP target genes, ANKRD1 and CTGF, while loss of expression of MARK2 or MARK3 had little or no effect on gene expression in these cells (Fig EV1B). A similar reduction in ANKRD1 expression by siMARK4 was also observed in MCF10A breast cancer cells and in two colorectal cancer cell lines, DLD‐1 and SW480 (Fig 1E). Of note, in MDA‐MB‐468 cells, loss of MARK3 attenuated expression of ANKRD1 and CTGF suggesting the existence of redundant, context‐dependent activities for distinct MARK family members (Fig EV1C, left panels). Here, we focused on MARK4 for further study.

Figure 1. Identification of MARK family members as activators of YAP/TAZ.

-

AA TEAD‐luciferase reporter assay was designed to identify modulators of YAP/TAZ transcriptional activity upon overexpression.

-

BLuminescence intensities from the TEAD‐luciferase reporter screen were normalized to β‐gal. Comparison of fold over median values from two runs is shown as a scatterplot.

-

CMARK family members activate the TEAD‐luciferase reporter. Flag‐tagged wild‐type MARK1, MARK2, MARK3, and MARK4 and kinase‐dead (KD) MARK4 were co‐transfected with wild‐type and mutant TEAD‐luciferase reporter constructs. Transcriptional activity was measured by luciferase assay, and data are shown as the mean ± SD of triplicate samples from a representative experiment performed four times.

-

D, EMARK4 loss of function decreases YAP/TAZ target gene expression. Cell lines, as indicated, were transfected with control siRNA or siRNA targeting MARK4. The levels of the YAP/TAZ target genes ANKRD1 or CTGF, and the knockdown efficiency for MARK4 was determined by real‐time qPCR. (D) Gene expression in MDA‐MB‐231 cells is plotted as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments each performed with three technical replicates (*P = 0.001 and **P = 0.0002 calculated using Student's two‐tailed t‐test). (E) Gene expression from a representative experiment performed twice in MCF10A, SW480, and DLD‐1 cells is plotted as the mean ± range of three technical replicates.

Source data are available online for this figure.

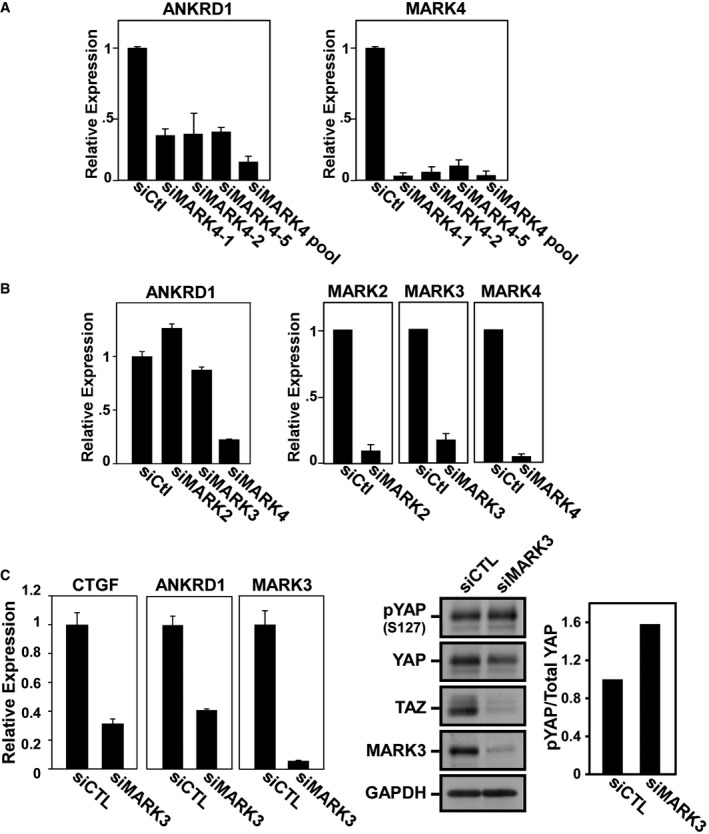

Figure EV1. Loss of MARK leads to decreased expression of YAP/TAZ target genes.

- Deconvolution of MARK4 siRNA. MDA‐MB‐231 cells were transfected with single siMARK4 oligonucleotides that comprise the pool. The expression of YAP/TAZ target gene, ANKRD1, and MARK4 knockdown efficiency was determined by real‐time qPCR and is plotted as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments each performed with three technical replicates.

- MDA‐MB‐231 cells were transfected with siRNAs targeting MARK2, MARK3, and MARK4. The expression of YAP/TAZ target gene, ANKRD1, and MARK4 knockdown efficiency was determined by real‐time qPCR and is plotted as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments each performed with three technical replicates.

- MDA‐MB‐468 cells were transfected with siControl or siMARK3. The expression of YAP/TAZ target genes, ANKRD1, CTGF, and MARK3 knockdown efficiency was determined by real‐time qPCR and plotted as the mean ± range (left panels) of a representative of two independent experiments each with three technical replicates. YAP phosphorylation and YAP/TAZ total levels were analyzed by immunoblotting using anti‐phospho‐YAP (S127), YAP, and TAZ antibodies, respectively. Knockdown efficiency was determined using MARK3 antibody, and GAPDH was used and the loading control. YAP phosphorylation in blots was quantified by measuring the ratio of phospho‐YAP (S127) to total YAP (right panels). The data are representative of two independent experiments.

MARK4 inhibits YAP/TAZ phosphorylation

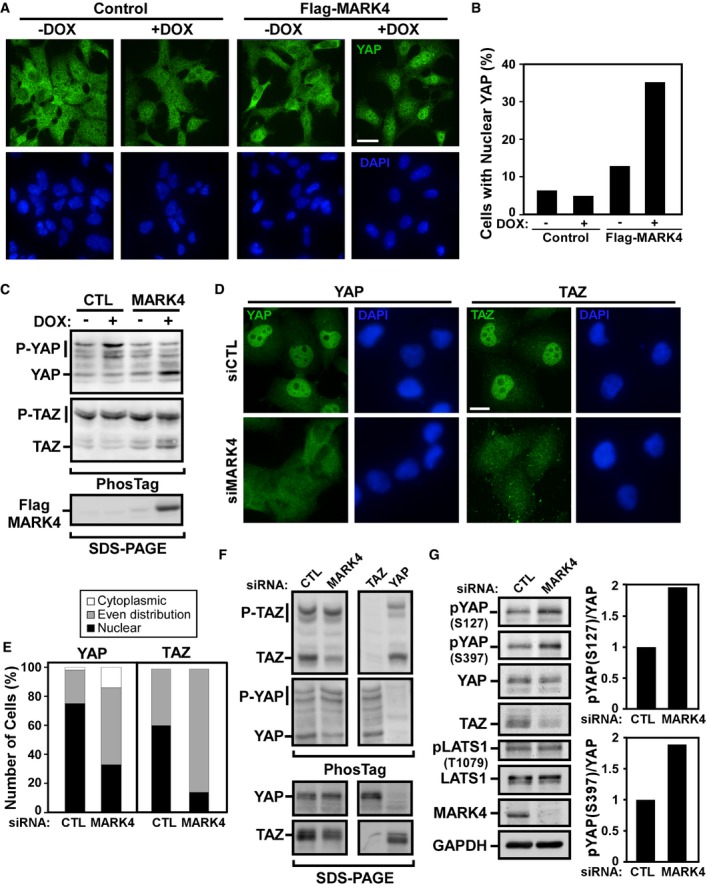

The Hippo pathway signals through a core kinase cassette comprised of MST1/2 and LATS1/2 in a complex with the adapter/scaffolding proteins, SAV and MOB that function to induce phosphorylation of YAP/TAZ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. Phosphorylated YAP/TAZ is localized to the cytoplasm where it is subsequently degraded thus preventing YAP/TAZ‐induced transcriptional activity. To explore whether MARK4 alters YAP/TAZ activity by regulating the Hippo pathway, we examined YAP/TAZ subcellular localization and phosphorylation. For this, we first investigated the effect of overexpression using HEK293 T‐REx cells stably expressing Dox‐inducible MARK4. In control HEK293T cells, YAP/TAZ display an equivalent nuclear to cytoplasmic distribution but upon induction of MARK4 expression, a marked increase in nuclear localization was evident as visualized by immunofluorescence microscopy (Fig 2A and B). A decrease in the ratio of phosphorylated to unphosphorylated YAP and TAZ was also observed as assessed using PhosTag gels, in which phosphorylated proteins display slower mobility (Fig 2C).

Figure 2. MARK4 regulates YAP/TAZ phosphorylation and localization.

-

A–CT‐REx 293 cells stably expressing an empty vector or Flag‐MARK4 were treated with doxycycline to induce MARK4 expression. (A) YAP localization was visualized by immunofluorescence confocal microscopy. Scale bar, 25 μm. (B) Nuclear accumulation in at least 30 cells for each condition was quantified and is plotted as a percentage of cells displaying the indicated distribution in one experiment. (C) YAP/TAZ phosphorylation was analyzed by immunoblotting on PhosTag SDS–PAGE gels using YAP and TAZ antibodies. The data are representative of four independent experiments.

-

D–GMDA‐MB‐231 cells were transfected with control siRNA or siRNAs targeting MARK4, YAP, or TAZ as indicated. (D) YAP and TAZ localization (green) in cells with nuclei costained with DAPI (blue) was determined by immunofluorescence confocal microscopy. Scale bar, 15 μm. (E) Subcellular localization in at least 50 cells for each condition was quantified and is plotted as a percentage of cells displaying the indicated distribution in a representative experiment of two independent experiments. (F, G) Cell lysates, separated on PhosTag or regular SDS–PAGE gels, were analyzed by immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies. (F) YAP/TAZ phosphorylation was assessed by mobility shift on PhosTag gels using YAP and TAZ antibodies. The data are representative of at least three independent experiments. (G) YAP phosphorylation on Ser127 and Ser397 and LATS phosphorylation on Thr1079 were analyzed by immunoblotting using phospho‐specific antibodies. The data are representative of three independent experiments. The ratio of phospho‐YAP at Ser127 and Ser397 to total YAP from the blots was quantified. Total levels of YAP, TAZ, LATS1, MARK4, and GAPDH as the loading control were determined as indicated.

Source data are available online for this figure.

We next examined the effect of abrogating MARK4 expression using siRNAs in MDA‐MB‐231 cells and observed a loss of the prominent YAP/TAZ nuclear localization found in controls when analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy or by subcellular fractionation (Figs 2D and E, and EV2A). A parallel increase in the relative levels of phosphorylated to unphosphorylated YAP and TAZ was also observed using either PhosTag gels or by immunoblotting regular gels with Phospho‐YAP Ser127 or Ser397 antibodies which recognize two distinct LATS‐mediated phosphorylation sites in YAP (Fig 2F and G). Degradation of YAP and TAZ that occurs subsequent to phosphorylation was also evident (Fig 2G). In MDA‐MB‐468 cells, loss of MARK3 similarly induced an increase in the relative level of phosphorylated YAP (Fig EV1C, right panels). Of note, in cells expressing a variant of TAZ harboring a mutation in a key LATS‐targeted phosphorylation site (TAZ S89A), loss of MARK4 did not promote cytoplasmic accumulation of TAZ (Fig 3A). As MST/LATS are key mediators of YAP/TAZ phosphorylation, these results are consistent with a role for MARK4 in directly modulating the Hippo pathway.

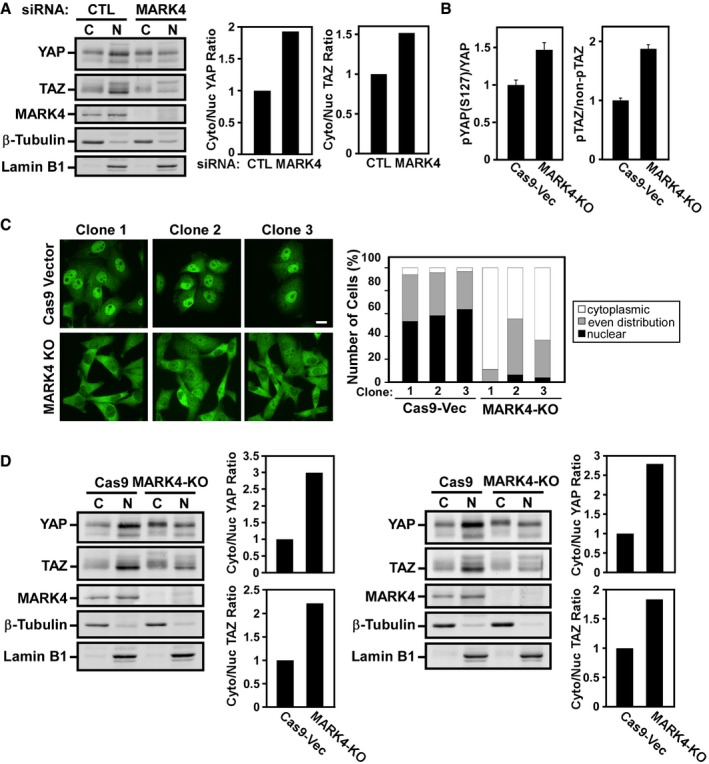

Figure EV2. MARK4 abrogation promotes nuclear to cytoplasmic translocation of YAP/TAZ .

- MDA‐MB‐231 cells were transfected with siControl or siMARK4, and subcellular localization of YAP/TAZ was analyzed by immunoblotting after biochemical fractionation. β‐tubulin and lamin B1 were used as cytoplasmic and nuclear markers, respectively. The ratio of cytoplasmic to nuclear YAP and TAZ in blots was quantified. C, cytoplasmic; N, nuclear. The data are representative of two independent experiments.

- Related to Fig 3B. The ratio of phospho‐YAP (S127) to total YAP and phosphorylated TAZ (upper band on PhosTag gel) to the un‐phosphorylated TAZ (lower band) were quantified from blots and plotted as the mean of 3 control (Cas9‐Vector) versus 3 MARK4 knockout (KO) clones ± SD.

- YAP localization (green) was assessed in control and MARK4‐KO cells by immunofluorescence confocal microscopy, and subcellular localization of YAP in at least 30 cells per clone was quantified and plotted as percentage of cells displaying the indicated distribution in a representative of two independent experiments. Scale bar 15 μm.

- Subcellular localization of YAP/TAZ was evaluated in two control (Cas9) and two MARK4 knockout (KO) clones by immunoblotting after biochemical fractionation, and the cytoplasmic to nuclear YAP/TAZ ratio in the blots was quantified (right panels) for each independent experiment.

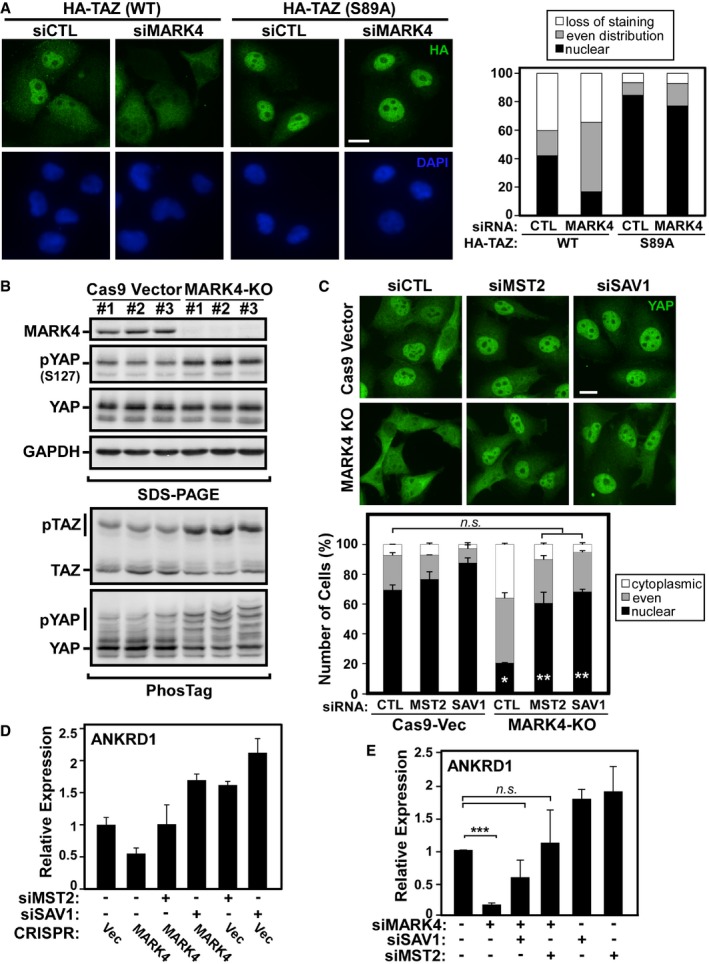

Figure 3. MARK4 regulation of YAP/TAZ is Hippo pathway dependent.

-

AMDA‐MB‐231 cells stably expressing HA‐tagged TAZ(WT) or TAZ(S89A) were transfected with control siRNA or siRNA targeting MARK4, and TAZ localization (green) was determined by immunofluorescence confocal microscopy using anti‐HA antibodies. The subcellular localization of TAZ in at least 50 cells for each condition was quantified and is plotted as a percentage of cells displaying the indicated distribution in a representative experiment of two independent experiments. Scale bar, 15 μm.

-

BMultiple independent MARK4‐knockout (KO) clones were generated in MDA‐MB‐231 cells using CRISPR/Cas9‐mediated gene editing. MARK4 knockout (KO) efficiency and YAP phosphorylation on Ser127 were determined by immunoblotting on regular SDS–PAGE gel using the indicated antibodies (top panels). YAP/TAZ phosphorylation was also assessed by immunoblotting using PhosTag gels (bottom panels). The data are representative of four independent experiments.

-

C, DControl (Cas9‐Vector) and MARK4 knockout (KO) cells were transfected with control siRNA or siRNAs targeting MST2 or SAV1. (C) YAP localization was determined by immunofluorescence confocal microscopy. The subcellular localization of YAP in at least 50 cells for each condition was quantified and is plotted as a percentage of the mean ± SD of at least two independent clones (*P = 0.001 as compared to Cas9‐Vec siCTL, **P = 0.003 as compared to MARK4‐KO siCTL; n.s., not significant, calculated using Student's two‐tailed t‐test). Scale bar, 20 μm. (D) The expression of the YAP/TAZ target gene, ANKRD1, in two control and two MARK4‐KO clones was assessed by qPCR and is plotted as the mean ± SEM for two independent experiments each performed with three technical replicates.

-

EMDA‐MB‐231 cells were transfected with control siRNA or siRNAs targeting MARK4, MST2, or SAV1, and the expression of ANKRD1 was assessed by qPCR and is plotted as the mean ± SEM of six independent experiments each performed with three technical replicates (***P < 10−4, n.s., not significant, calculated using Student's two‐tailed t‐test).

Source data are available online for this figure.

MARK4 knockout promotes cytoplasmic localization of YAP/TAZ in MDA‐MB‐231 cells

To further investigate the role of MARK4 in regulating the Hippo pathway, we used CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing technology 46 to knockout MARK4 in MDA‐MB‐231 breast cancer cells. We designed several guide RNAs targeting human MARK4 and obtained multiple clones that showed complete knockout as assessed by immunoblotting (Fig 3B). MARK4 knockout resulted in an increase in YAP and TAZ phosphorylation levels as assessed by immunoblotting of regular gels using anti‐phospho‐YAP (Ser127) antibody or by examining migration on PhosTag gels (Figs 3B and EV2B). Consistent with the increased phosphorylation, MARK4 knockout clones showed a marked loss of nuclear YAP/TAZ and an increase in cytoplasmic localization compared to control clones as assessed by immunofluorescence microscopy (Fig EV2C) and by subcellular fractionation (Fig EV2D) that correlated with the expression of the YAP/TAZ target gene, ANKRD1 (Fig EV3A). Importantly, simultaneous abrogation of expression of the core kinase cassette components, MST2 or SAV1, prevented the MARK4‐induced cytoplasmic accumulation of YAP/TAZ and restored ANKRD1 expression in MARK4 KO cell lines (Fig 3C and D, and EV3B). A similar restoration of ANKRD1 expression by siSAV1 or siMST2 was also observed when MARK4 expression was abrogated using siRNAs (Figs 3E and EV3C).

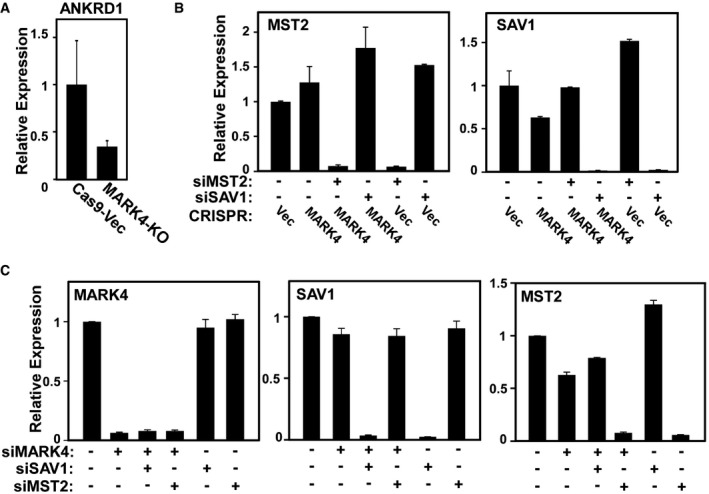

Figure EV3. MARK4 knockout results in a decrease in YAP/TAZ target gene expression.

- The expression of the YAP/TAZ target, ANKRD1, was assessed in two control and two MARK4‐KO clones by real‐time qPCR and is plotted as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments performed with three technical replicates.

- Related to Fig 3D. MST2 and SAV1 knockdown efficiencies were determined by real‐time qPCR and plotted as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments each performed with three technical replicates.

- Related to Fig 3E. MARK4, SAV1, and MST2 knockdown efficiencies were determined by real‐time qPCR and plotted as mean ± SEM of six independent experiments each performed with three technical replicates.

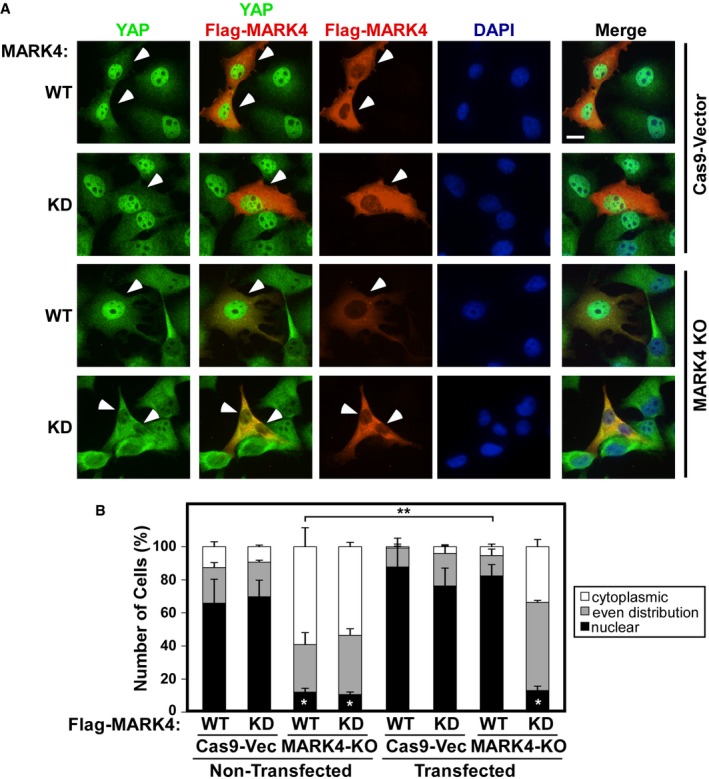

We next transfected control and MARK4 knockout cells with either wild‐type (WT) or kinase‐dead (KD) versions of MARK4 and examined YAP/TAZ localization by immunofluorescence microscopy. Reintroduction of wild‐type but not kinase‐dead Flag‐tagged MARK4 rescued the loss of nuclear YAP/TAZ in MARK4 knockout cells (Fig 4A and B). Consistent with this, our TEAD‐reporter assay showed that wild‐type but not the kinase‐dead Flag‐MARK4 activates luciferase activity (Fig 1C). Collectively, these data provide compelling evidence that MARK4 depletion promotes cytoplasmic localization of YAP/TAZ by regulating the Hippo pathway and MARK4 kinase activity is required for Hippo pathway regulation.

Figure 4. Expression of MARK4 rescues nuclear YAP/TAZ localization in MARK4 knockout cells.

- Control (Cas9‐vector) and MARK4‐KO cells were transfected with wild‐type (WT) or kinase‐dead (KD) Flag‐MARK4 and YAP/TAZ (green) and MARK4 (red) localization was determined by immunofluorescence confocal microscopy using anti‐YAP or anti‐Flag antibodies, respectively. Arrowheads indicate the transfected cells. Scale bar, 15 μm.

- The subcellular localization of YAP in at least 30 transfected and adjacent non‐transfected cells for each condition was quantitated and plotted as a percentage of the mean ± SD from three independent experiments (*P = 0.006–0.008, as compared to Cas9‐Vec non‐transfected, **P = 0.001 as compared to MARK4‐KO non‐transfected, calculated using Student's two‐tailed t‐test).

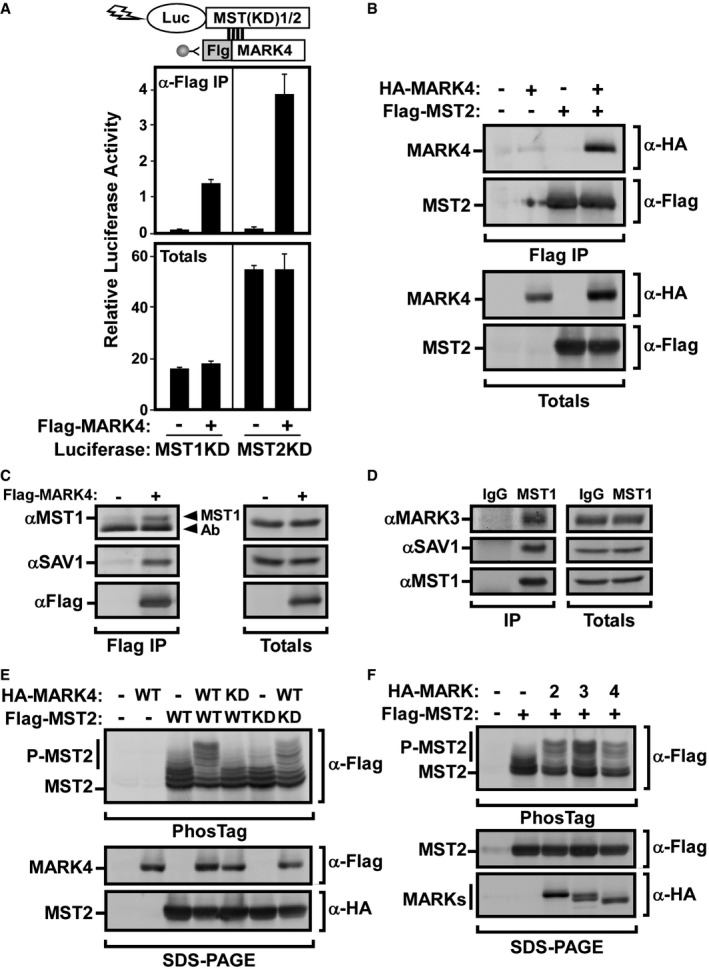

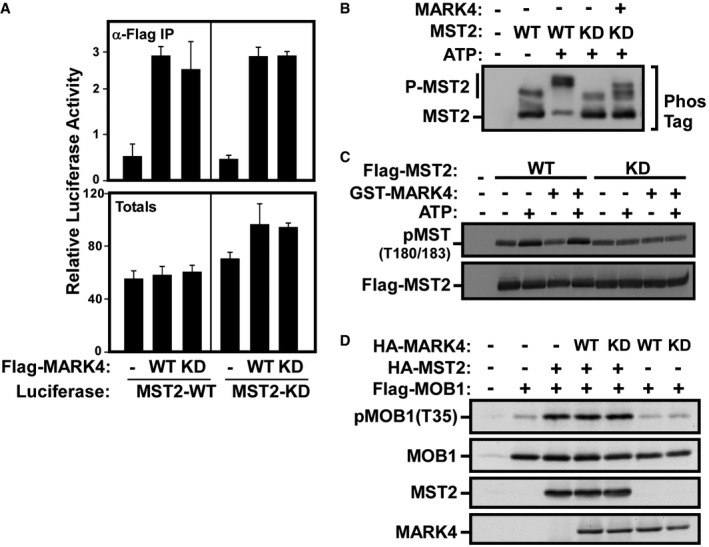

MARK4 interacts with and phosphorylates MST kinases

To determine the molecular mechanism of MARK4 function in Hippo signaling, we first tested for physical interactions between MARK4 and the Hippo pathway MST core kinase using LUMIER 31. For this, MST variants fused to firefly luciferase were coexpressed with wild‐type (WT) or kinase‐dead (KD) Flag‐tagged MARK4 and interactions examined by anti‐Flag immunoprecipitation followed by measurement of luciferase activity. This analysis revealed that WT and KD MARK4 interacted with both WT and KD versions of MST1 and MST2 (Figs 5A and EV4A). Corroborating the associations detected by LUMIER, an interaction was also observed by immunoprecipitation of Flag‐MST2 and immunoblotting for HA‐MARK4 (Fig 5B), and by immunoprecipitating Flag‐MARK4 and immunoblotting for endogenous MST1 (Fig 5C). Similarly, an interaction between endogenous MST1 and MARK3 in HEK293T cells was also detected (Fig 5D).

Figure 5. MARK4 interacts with and phosphorylates MST kinases.

-

AHEK293T cells were transfected with firefly luciferase‐tagged kinase‐dead variants of either MST1 or MST2 and Flag‐MARK4. Cell lysates were subject to anti‐Flag immunoprecipitation, and the presence of MST1/2 was assessed by luciferase assay. Cells transfected with luciferase‐tagged MST1/2 alone were used as negative controls, and total expression was confirmed by luciferase assay and plotted as the mean ± SD of triplicate samples from a representative of two independent experiments.

-

BLysates from HEK293T cells transfected with Flag‐MST2 and HA‐MARK4 were subject to anti‐Flag immunoprecipitation, and the presence of MARK4 was determined by anti‐HA immunoblotting. Equivalent protein expression levels were confirmed (Totals). The data are representative of three independent experiments.

-

C, DMARK3 and MARK4 interact with endogenous MST1 and SAV1. (C) HEK293T cells were transfected with either empty vector or Flag‐MARK4. Cell lysates were subject to anti‐Flag immunoprecipitation, and binding to endogenous MST1 and SAV1 was determined by immunoblotting using specific antibodies. Total cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting. (D) Cell lysates from HEK293T cells were subjected to anti‐IgG or anti‐MST1 immunoprecipitation, and the presence of endogenous MARK3 and SAV1 was determined by immunoblotting using specific antibodies. Total cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting. The data are representative of two independent experiments.

-

E, FMARK4 phosphorylates MST2. HEK293T cells were co‐transfected with wild‐type or kinase‐dead HA‐tagged MARK2, MARK3 (E), or MARK4 (E, F) along with wild‐type or kinase‐dead Flag‐tagged MST2 constructs, as indicated. MST2 phosphorylation was assessed by analyzing mobility shifts by anti‐Flag immunoblotting using PhosTag SDS–PAGE gels. Total cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting by regular SDS–PAGE. The data are representative of three independent experiments.

Source data are available online for this figure.

Figure EV4. MARK4 interacts with and phosphorylates MST2 kinase.

-

AHEK293T cells were transfected with either wild‐type (WT) or kinase‐dead (KD) Flag‐MARK4 and firefly luciferase‐tagged wild‐type (WT) or kinase‐dead (KD) variants of MST2. Cell lysates were subject to anti‐Flag immunoprecipitation, and the presence of MST2 was assessed by luciferase assay and plotted as the mean of triplicate samples ± SD of a representative of two independent experiments. Cells transfected with luciferase‐tagged MST2 alone were used as negative controls, and total expression was confirmed by luciferase assay.

-

B–DMST2 phosphorylation and kinase activity in the presence of MARK4 were assessed by an in vitro kinase assay using purified GST‐MARK4. HEK293T cells were transfected with wild‐type (WT) and kinase‐dead (KD) Flag‐MST2, and cell lysates were subjected to anti‐Flag immunoprecipitation. Immunoprecipitated Flag‐MST2 was incubated with GST‐MARK4 in the presence or absence of ATP, as indicated. MST2 phosphorylation was analyzed by immunoblotting using PhosTag SDS–PAGE gels (B), and MST2 kinase activity was assessed by immunoblotting for autophosphorylation using phospho‐MST1/2 (T180/183) antibody (C). The data are representative of three independent experiments. (D) The effect of MARK4 expression on MST2 kinase activity was further analyzed by evaluating MOB1 phosphorylation as the MST1/2 direct substrate. HEK293T cells were transfected with Flag‐MOB1 and HA‐MST2 along with wild‐type (WT) or kinase‐dead (KD) versions of HA‐MARK4. MOB1 phosphorylation at the MST1/2 phospho‐site Thr35 was assessed by immunoblotting using the specific antibody. The data are representative of two independent experiments.

Given that MARK4 is a kinase, we speculated that MARK4 might inactivate the Hippo pathway by phosphorylating and thereby inhibiting MST activity. To test whether MARK4 could phosphorylate MST, HA‐tagged MARK4 was coexpressed with Flag‐MST2 in HEK293T cells, and MST2 mobility on a PhosTag SDS–PAGE gel was examined. Flag‐MST2 expressed alone showed multiple bands indicative of the existence of multiple phosphorylation site variants when expressed in mammalian cells (Fig 5E). Coexpression of wild‐type but not kinase‐dead MARK4 caused additional upshifts in MST2, demonstrating that the MARK4 kinase activity was required for the appearance of the additional phosphorylated variants of MST2 (Fig 5E). The MARK4‐induced upshifts were also observed in the presence of kinase‐dead MST2, indicating that MST2 autophosphorylation was not involved. Analysis of two other members of the MARK family showed that similar to MARK4, overexpression of MARK2 and MARK3 caused the appearance of MST2 bands of slower mobility (Fig 5F). Thus, the ability to phosphorylate MST2 is conserved among MARK family members. To further confirm phosphorylation of MST2 by MARK4, we performed an in vitro kinase assay using Flag‐MST2 immunoprecipitates and purified MARK4 protein produced in Sf9 cells. When expressed alone, addition of ATP to wild‐type but not kinase‐dead MST2 resulted in a prominent upshift on PhosTag gels, indicating robust autophosphorylating activity (Fig EV4B). Thus, to avoid ambiguities due to MST kinase activity in our analysis of MARK4‐mediated phosphorylation, we focused on using the kinase‐dead variant of MST2. Addition of purified GST‐MARK4 to kinase‐dead MST2, in the presence of ATP, resulted in the appearance of an upshifted MST2 band, consistent with our results in HEK293T cells (Fig EV4B). Thus, MARK can directly phosphorylate MST2.

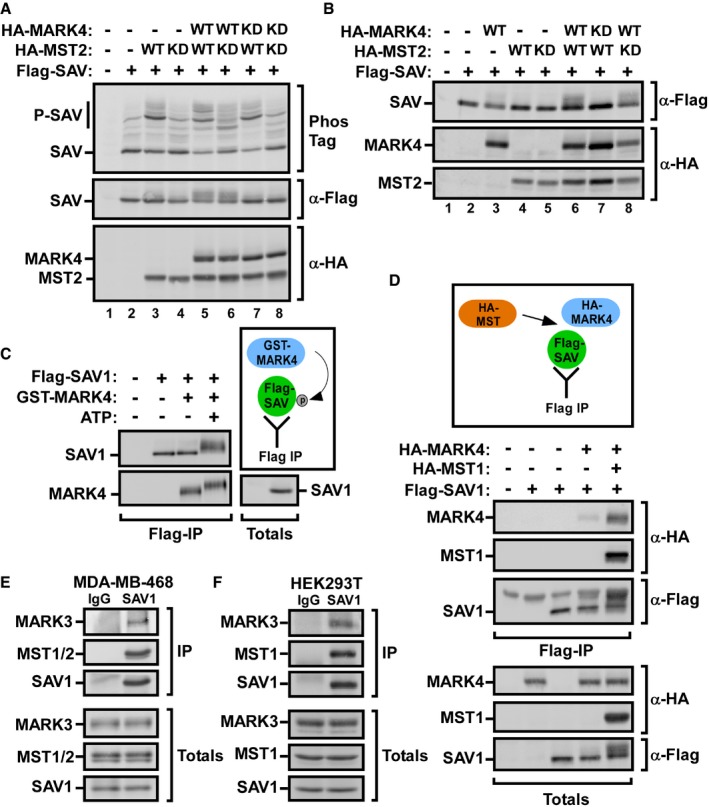

MARK4 phosphorylates SAV and this is enhanced by MST2

MST directly binds to and phosphorylates the adaptor protein Salvador (SAV), and this promotes the interaction of MST with the downstream kinase LATS 1, 2, 3, 47. Thus, we sought to determine whether MARK4‐mediated phosphorylation of MST alters the ability of MST to phosphorylate SAV. When expressed alone, Flag‐SAV1 is predominately unphosphorylated and consistent with published results 48, 49, coexpression of WT but not kinase‐dead MST2 induces an upshift of SAV on a PhosTag gel, indicative of SAV phosphorylation (Fig 6A). Co‐expression of MARK4 did not cause a marked change in MST‐induced phosphorylation of SAV, suggesting that although MARK4 can phosphorylate MST, this did not alter MST kinase activity toward SAV. Consistent with this, MARK4 phosphorylation of MST2 did not alter intrinsic MST2 kinase activity as assessed in an in vitro MST2 autophosphorylation assay using an activation loop phospho‐MST1/2 (T180/183) antibody (Fig EV4C) or by evaluating the MOB1 phosphorylation using antibodies that recognize the MST‐targeted site, Thr35 (Fig EV4D). However, when wild‐type MARK4 was co‐expressed with MST2 and SAV in mammalian cells, we noticed the appearance of a new Flag‐SAV1 upshifted band in both PhosTag and regular SDS–PAGE gels that was not detected in the presence of kinase‐dead MARK4 (Fig 6A, lanes 5–8). This suggested that MARK4 can phosphorylate SAV. To investigate this further, we co‐expressed Flag‐SAV1 with HA‐MARK4 alone or in the presence or absence of HA‐MST2 and assessed SAV upshifts using regular SDS–PAGE gels (Fig 6B). Expression of wild‐type MARK4 alone resulted in the appearance of a more slowly migrating variant of Flag‐SAV1 even in the absence of MST2 (Fig 6B, lane 3), while expression of MST2 alone did not alter the migration of SAV on these gels (Fig 6B, lane 4). Of note, when MARK4 was co‐expressed with either wild‐type or kinase‐dead MST2, there was an increase in the levels of upshifted Flag‐SAV1 (Fig 6B, lanes 6 and 8). This suggested that MST2 might increase MARK4‐mediated phosphorylation of SAV by enhancing the interaction of SAV with MARK4 and that this effect was independent of MST kinase activity. We confirmed that MARK4 can directly phosphorylate SAV, by performing an in vitro kinase assay using Flag‐SAV1 immunoprecipitates and purified GST‐MARK4. Addition of MARK4 in the presence of ATP induced SAV phosphorylation as determined by immunoblotting of lysates separated on PhosTag gels (Fig 6C). Of note, GST‐MARK4 showed a slower migration in the presence of ATP, suggesting that MARK4 autophosphorylation also occurs.

Figure 6. MARK4 binds to and phosphorylates the adaptor protein SAV.

-

A, BAnalysis of SAV phosphorylation by MST2 in the presence or absence of MARK4. Flag‐SAV1 was transfected alone or in various combinations with wild‐type (WT) or kinase‐dead (KD) MST2 in the presence or absence of wild‐type (WT) or kinase‐dead (KD) HA‐MARK4, as indicated. Immunoblotting was used to analyze SAV phosphorylation by assessing mobility shift on PhosTag (A) or using regular SDS–PAGE gels (B).

-

CAnalysis of SAV phosphorylation by MARK4 using an in vitro kinase assay. HEK293T cells were transfected with Flag‐tagged SAV1, and cell lysates were subject to anti‐Flag immunoprecipitation. Immunoprecipitated Flag‐SAV1 was incubated with GST‐MARK4 in the presence or absence of ATP, as indicated, and phosphorylated SAV1 was analyzed by immunoblotting.

-

D–FSAV binds to MARK4, and the presence of MST1/2 kinases enhances SAV interaction with MARK4. (D) HEK293T cell was transfected with Flag‐SAV1, HA‐MARK4, and HA‐MST1. Cell lysates were subject to anti‐Flag immunoprecipitation, and the presence of HA‐MARK4 and HA‐MST1/2 was determined by anti‐HA immunoblotting. Equal protein expression levels were confirmed (Totals). Cell lysates from MDA‐MB‐468 (E) and HEK293T (F) cells were subject to anti‐SAV1 immunoprecipitation, and binding to MARK3 and MST1 was determined by immunoblotting using specific antibodies. Equal protein expression levels were confirmed (Totals).

The MARK4‐induced upshift of SAV was increased in the presence of MST; thus, we sought to investigate whether the presence of MST enhances binding of MARK4 to SAV. We observed a weak interaction between SAV and MARK4 as determined by Flag‐SAV1 immunoprecipitation followed by immunoblotting for HA‐MARK4 (Figs 6D and EV5A). Of note, the presence of either MST1 or MST2 enhanced the interaction between SAV and MARK4 (Figs 6D and EV5A). The ability of endogenous SAV1 to interact with both MARK3 and MST1 in MDA‐MB231 and in HEK293T cells was also confirmed (Fig 6E and F, and see also Fig 5D). Altogether, these results show that MARK4 can bind to and phosphorylate SAV and that MST enhances the interaction between MARK4 and SAV.

Figure EV5. MARK4 forms a multiprotein complex with MST/SAV .

- SAV1 binds to MARK4, and the presence of MST2 kinase enhances SAV1 interaction with MARK4. HEK293T cell was transfected with Flag‐SAV1, HA‐MARK4, and HA‐MST2. Cell lysates were subject to anti‐Flag immunoprecipitation, and the presence of HA‐MARK4 and HA‐MST1/2 was determined by anti‐HA immunoblotting. Equal protein expression levels were confirmed (Totals). The data are representative of three independent experiments.

- MARK4 expression has no effect on MST/SAV binding. HEK293T cells were transfected with Flag‐SAV1, firefly luciferase‐tagged MST2, and wild‐type (WT) or kinase‐dead (KD) versions of HA‐MARK4. Cell lysates were subjected to anti‐Flag immunoprecipitation, and the MST2 binding to SAV was assessed by luciferase assay and plotted as the mean of three biological samples ± SD from one experiment. Cells transfected with luciferase‐tagged MST2 alone were used as negative controls, and total expression was confirmed by luciferase assay.

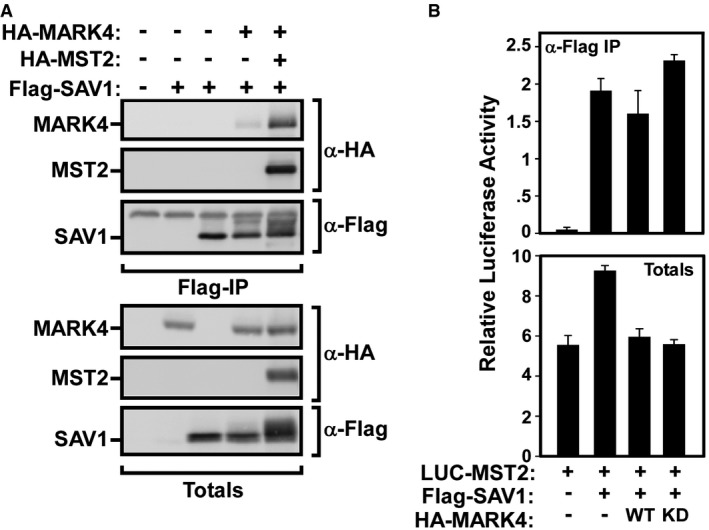

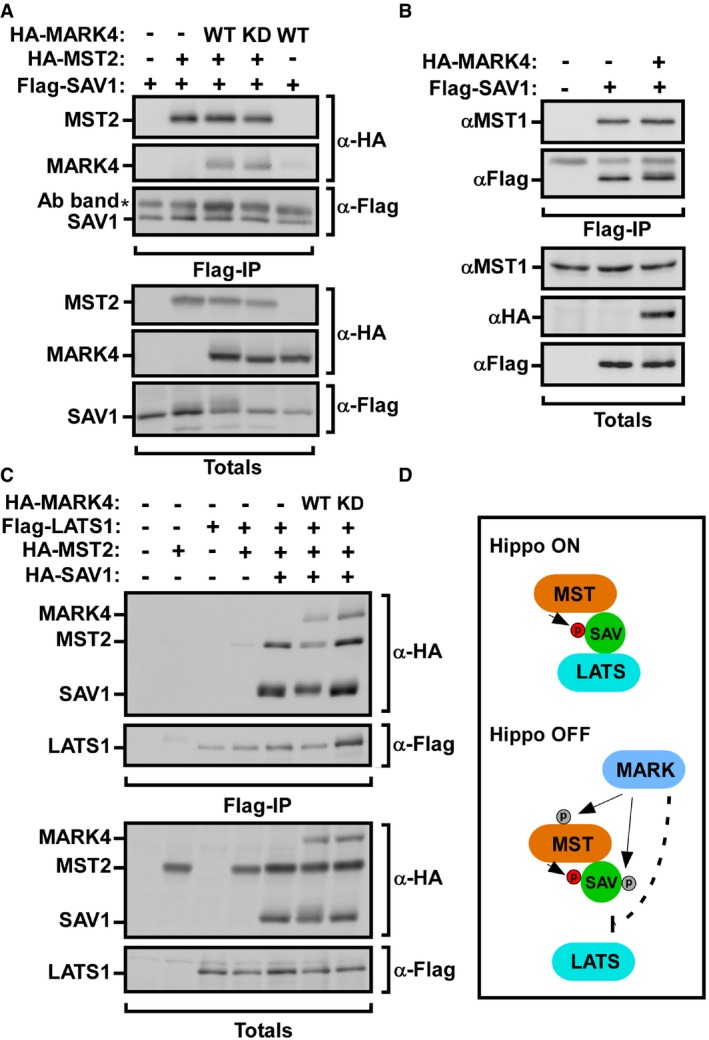

MARK4 disrupts complex formation between Hippo components MST/SAV and LATS

We speculated that phosphorylation of MST and SAV by MARK4 might inhibit MST and SAV interaction. To test this possibility, we analyzed the interaction between Flag‐SAV1 with either transfected or endogenous MSTs in the presence or absence of MARK4. Flag‐SAV1 efficiently interacted with both HA‐MST2 and with endogenous MST1, and this was not altered in the presence of HA‐MARK4 (Figs 7A and B, and EV5B). SAV acts as an adaptor that binds to MST and promotes complex formation between MST and LATS 1, 2, 3, 47. Thus, we next examined whether MARK4 might attenuate the interaction of the MST/SAV complex with the downstream kinase LATS by immunoprecipitation followed by immunoblotting. Consistent with the proposed function of SAV as an adaptor protein, the interaction between LATS and MST was markedly enhanced in the presence of SAV (Fig 7C). Notably, co‐expression of wild‐type MARK4 but not the kinase‐dead version significantly decreased the association of MST with LATS in the presence of SAV (Fig 7C). Altogether, our data suggest that MARK4 can phosphorylate MST and SAV, and that expression of MARK4 in a kinase‐dependent manner attenuates complex formation between Hippo core components MST/SAV with LATS (Fig 7D). We did not detect any changes MST‐mediated phosphorylation of endogenous LATS upon loss of MARK4 expression (Fig 2G), suggesting that activation of a small pool of LATS is sufficient to induce cytoplasmic YAP/TAZ.

Figure 7. MARK4 attenuates formation of a MST/SAV/LATS complex.

-

A, BHEK293T cells were transfected with combinations of Flag‐SAV1 and HA‐MST2 in the presence or absence of HA‐MARK4. Cell lysates were subjected to anti‐Flag immunoprecipitation followed by immunoblotting using anti‐HA (A) and anti‐MST1 (B) antibodies, respectively.

-

CHEK293T cells were transfected with Flag‐LATS1 and HA‐tagged MST2, SAV1, and wild‐type (WT) or kinase‐dead (KD) MARK4 as indicated. Cell lysates were subjected to anti‐Flag immunoprecipitation, and the interaction of MST with SAV was determined by anti‐HA immunoblotting. Equal protein expression levels were confirmed (Totals).

-

DModel for MARK4 function in regulating the Hippo pathway. MARK phosphorylates the Hippo core components MST and SAV and disrupts complex formation between MST/SAV and LATS in a kinase‐dependent manner, which inhibits the Hippo kinase cascade.

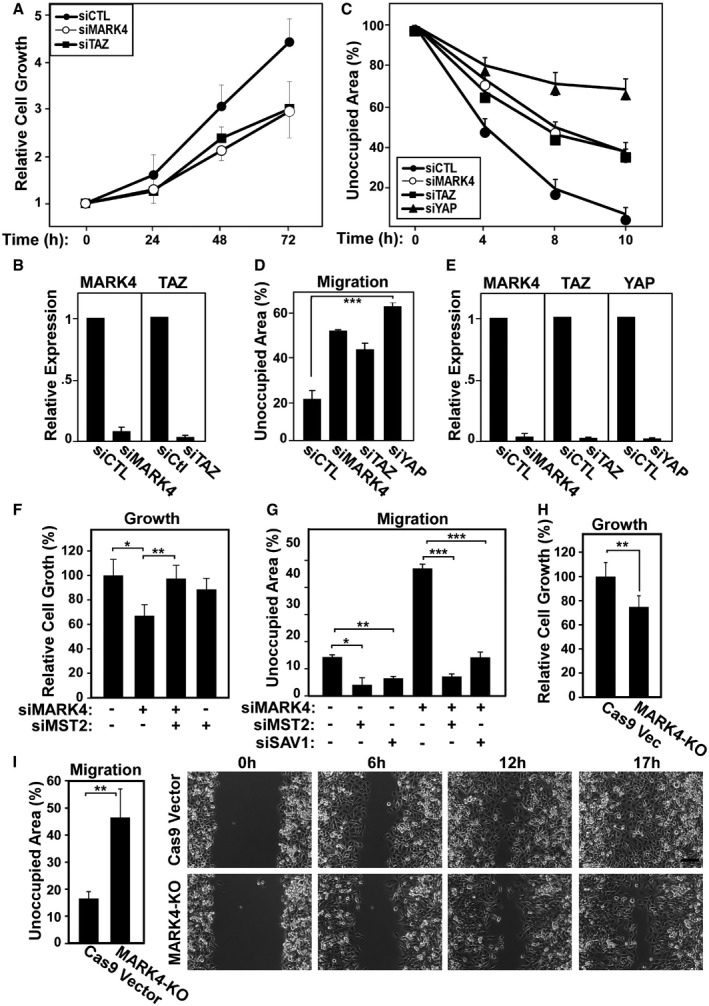

MARK4 depletion attenuates proliferation and migration in breast cancer cells

Numerous studies have established the importance of Hippo signaling in tumorigenesis and have shown that increased activity of YAP/TAZ is associated with enhanced cell proliferation and migration 3, 23, 24. MDA‐MB‐231 cells are aggressive triple‐negative breast cancer cells, which have undergone epithelial to mesenchymal transition and have bypassed cell‐cell contact inhibition. The Hippo pathway is dampened in these cells, and YAP/TAZ are predominantly nuclear, contributing to their tumorigenic properties 34, 44, 45. Our data show that MARK4 expression strongly activates YAP/TAZ and that abrogation of MARK4 expression leads to loss of nuclear localization and transcriptional activity of YAP/TAZ. Therefore, we sought to determine whether loss of MARK4 would alter tumorigenic properties of MDA‐MB‐231 cells. Thus, we first evaluated the role of MARK4 in the growth of MDA‐MB‐231 cells by abrogating expression of MARK4 with siRNAs. We observed that loss of MARK4 expression resulted in a marked decrease in cell proliferation as measured by sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay (Fig 8A and B). This reduction was comparable to the decrease observed upon loss of TAZ (Fig 8A and B) or YAP 34. Next, we examined the effect of loss of MARK4 expression on MDA‐MB‐231 cell migration using the wound healing scratch assay. MARK4 depletion resulted in a marked decrease in cell migration similar to TAZ knockdown, though less dramatic than that observed upon loss of YAP (Fig 8C–E). This is consistent with a recent study showing that MARK4 downregulation by miR‐515‐5p in breast and lung cancer cells reduces cell migration and metastasis 50. To demonstrate that the MARK4 effects on cell proliferation and migration are through the Hippo pathway, we sought to rescue the effects by blocking the expression of MST and SAV. Importantly, concomitant abrogation of SAV1 or MST2 expression overcame the inhibitory effects of siMARK4 on cell growth and migration indicating that MARK4 functions through SAV1/MST2 (Fig 8F and G). We also examined MARK4 knockout cells generated by CRISPR, and similar to siRNA‐mediated knockdown, MARK4 knockout cells showed a decrease in cell growth and migration (Fig 8H and I). Thus, loss of MARK4 in MDA‐MB‐231 breast cancer cells decreases YAP/TAZ activity and attenuates cell growth and migration. Taken together, our findings show that MARK4 disrupts complex formation between Hippo core components and thereby functions as a negative regulator of Hippo signaling to promote cell migration and proliferation of breast cancer cells.

Figure 8. Abrogation of MARK4 expression attenuates cell growth and cell migration in breast cancer cells.

-

A–EMDA‐MB‐231 cells were transfected with control siRNA or siRNAs targeting MARK4, TAZ, or YAP. (A) Cell growth was assessed and plotted as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments each performed with six replicates. (B) Knockdown efficiency was determined by qPCR and is plotted as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments each performed with three technical replicates. (C–E) Cell migration was monitored, and the cell‐free area was quantified for a representative experiment (C) or for the average of three independent experiments (D) with four independent fields per condition and is plotted as the mean ± SD or the mean ± SEM, respectively. In (D), ***P‐values for siCtl compared to siMARK, siTaz, and siYAP were 0.0004, 0.0001, and 0.0003, respectively. (E) Knockdown efficiency was determined by qPCR and plotted as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments each performed with three technical replicates.

-

F, GLoss of MST2 or SAV1 rescues the effect of MARK4 knockdown on cell growth and migration. (F) MDA‐MB‐231 cells were transfected with control siRNA or siRNA targeting MARK4, MST2, or both, and cell growth was assessed and plotted as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments, each performed with six replicates (*P = 0.05 and **P = 0.009). (G) Cell migration was assessed, and the cell‐free area was quantitated as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments, in four independent fields per condition (*P = 0.02, **P = 0.002, ***P < 10−4).

-

HCell growth in two control (Vec) and two MARK4 KO cell clones was assessed and plotted as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments, each performed with six replicates (**P = 0.002).

-

ICell migration in control (Vec) and MARK4 KO cells was assessed, and the cell‐free area was quantitated as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments in four independent fields per condition (**P = 0.009). Representative images are shown (right). Scale bar, 126 μm.

Discussion

In this study, we performed a high‐throughput TEAD‐luciferase reporter screen to uncover genes that modulate YAP/TAZ activity upon overexpression and identified multiple members of MAP/microtubule regulating kinase (MARK) family as top hits. We demonstrate that expression of MARK family members leads to robust activation of the TEAD reporter, an indicator of YAP/TAZ transcriptional activity, and that depletion of MARK4 expression in breast cancer cells results in loss of YAP/TAZ nuclear localization and a marked decrease in target gene expression. Mechanistically, we show that MARK4 binds to and phosphorylates the core components of the Hippo pathway, MST and SAV, and that MARK4, in a kinase‐dependent manner, inhibits the assembly of core the Hippo kinase cassette by disrupting the interaction of MST and SAV with LATS.

The mammalian MARK family is comprised of four kinases, MARK1–4 (also referred to Par‐1c, Par‐1b, Par‐1a, and Par‐1d, respectively) which are orthologs of the Drosophila Par‐1 protein. Thus, MARK/Par‐1 kinases are evolutionarily conserved proteins with diverse roles in embryonic development, asymmetric cell division, and cell polarity regulation 36, 37, 41, 42. MARKs belong to the larger AMPK family, which includes multiple Ser/Thr kinases with diverse cellular and physiological functions including the prototypic AMP‐activated protein kinase (AMPK) as well as Salt‐inducible kinases (SIKs) 36, 37. AMPK is a master regulator of energy balance in the cell and responds to nutrient availability and intracellular energy levels to regulate metabolic pathways 38, 39. Recent studies have shown that several members of the AMPK family have divergent roles in regulating Hippo signaling. For example, activation of AMPK in response to glucose deprivation increases LATS1/2 kinase activity to restrict YAP/TAZ function 18, 19, 20. In contrast, a study in Drosophila has shown that SIKs inhibit the Hippo kinase cascade to activate Yorki (Yki, the YAP/TAZ ortholog) and promote tissue growth by phosphorylating SAV 40. Although the SIK phosphorylation site is not conserved in mammals, overexpression of human SIK2 in HEK293T cells activated the TEAD reporter, suggesting that SIK may have retained an inhibitory function on the Hippo pathway in mammals 40. Together with our findings showing that MARKs inhibit the Hippo pathway, these studies highlight the role of AMPK family members as differential but important upstream regulators of the Hippo signaling pathway. Understanding how and whether MARKs and AMPK family members link to other Hippo regulatory pathways such as mechanotransduction would be a pertinent avenue for future studies.

Our work has shown that abrogation of MARK4 expression either transiently using siRNAs or genomically using CRISPR/Cas9 promotes the cytoplasmic localization of YAP/TAZ and inhibits target gene expression. While we did not detect any changes MST‐mediated phosphorylation of endogenous LATS upon loss of MARK4 expression (Fig 2G), it may be that activation of a small pool of LATS that is not efficiently detected by the antibodies is sufficient to induce cytoplasmic YAP/TAZ. In Drosophila, and consistent with our findings, loss of Par‐1 (the MARK ortholog) also leads to activation of the Hippo pathway and results in a marked decrease in eye and wing imaginal disk size that is dependent on Yorki 51. In mice, shRNA‐mediated loss of two other MARK family members, Mark2 and Mark3 [Par‐1a/Par‐1b], also promotes cytoplasmic localization of Yap in mouse trophoblast cells during early embryonic development 52. While we focused on MARK4 due to a prominent effect in MDA‐MB‐231 cells, overexpression of MARK2, MARK3, and MARK4 activates the TEAD‐luciferase reporter (Fig 1D) and siRNA‐mediated depletion of MARK3 [PAR‐1a] in MDA‐MB‐468 cells also promotes YAP/TAZ phosphorylation and decreases expression of target genes (Fig EV2). Thus, multiple MARK family members have a similar ability to positively regulate YAP/TAZ activity. A recent study showed that LKB1‐deficient tumors display high levels of nuclear YAP and that LKB1 promotes Hippo pathway activity by regulating the localization of the basolateral protein, Scribble 53. In contrast to findings that MARKs enhance YAP/TAZ activity (herein and 51, 52), in this study it was proposed that MARKs act downstream of LKB to inhibit YAP/TAZ. The differing roles of MARKs in regulating Hippo signaling in distinct contexts will require further investigation.

MARKs are Ser/Thr kinases, and our analysis of the rescue of the MARK4 knockout phenotype clearly demonstrates that MARK4 kinase activity is required to regulate YAP/TAZ localization. Concordantly, our investigation of whether MARK4 regulates YAP/TAZ by phosphorylating any of the Hippo core components revealed that it binds to and phosphorylates both MST and SAV. Moreover, we demonstrated that MARK4, in a kinase‐dependent manner, inhibits the assembly of core Hippo kinase cassette by disrupting the interaction of MST and SAV with LATS (Fig 7C). Epistasis analysis of Par‐1 in Drosophila placed Par‐1 upstream of the Hippo (Hpo) core kinase, while molecular analysis showed that Par‐1 could phosphorylate and decrease Hpo kinase activity 51. Although we observe an increase in MST upshift in PhosTag gel upon MARK4 expression, indicative of phosphorylation, we did not observe a change in MST kinase activity toward its substrate SAV. However, we also observed MARK‐dependent phosphorylation of SAV and a decrease in complex formation between the Hippo core components MST and SAV with LATS. Of note, analysis of Drosophila Salt‐inducible kinases (SIKs) describes a similar finding, namely that SIKs phosphorylate Sav and that this phosphorylation disrupts the interaction between Hpo and Sav with Wrts, the orthologs of mammalian MST, SAV, and LATS, respectively 40. Thus, the mechanism proposed for SIKs is consistent with the one we observed for MARK4 (Fig 7D). Although MARKs and SIKs are distinct kinases, they are both AMPK family members, and the similarity of mechanisms in flies and mammalian cells suggests that modulation of complex formation between Hippo pathway core components is an evolutionarily conserved mechanism for regulating Hippo signaling. Altogether, these data suggest that although there are similarities between Drosophila and mammalian Par‐1 in regulating Hippo signaling, there appears to be a divergence in the mechanism of action.

Numerous studies have firmly established the role of YAP/TAZ during tumorigenesis. YAP/TAZ activate a growth promoting gene expression program, and increased activity of YAP/TAZ has been associated with cell proliferation, migration, resistance to apoptosis, transformation of normal epithelial cells, increased cancer stem cell content, and higher resistance to chemotherapeutic agents 3, 23, 24. MDA‐MB‐231 cells are aggressive triple‐negative breast cancer cells with an inactive Hippo pathway. These cells show predominantly nuclear YAP/TAZ, which contributes to their tumorigenic characteristics, thus providing a suitable cell line model to study the biological impact of YAP/TAZ modulators 44, 45. In agreement with a role for MARK4 in promoting YAP/TAZ‐dependent transcription, we demonstrate that MARK4 loss of function either transiently by siRNA‐mediated knockdown or permanently by CRISPR/Cas9‐mediated knockout attenuates proliferation and migration in MDA‐MB‐231 breast cancer cells. Given that depletion of MARK3, in a different breast cancer line, similarly induced cytoplasmic localization of YAP/TAZ, our findings suggest that targeting MARK activity might provide therapeutic benefit in breast cancer by restricting YAP/TAZ activity. In future work, it would be interesting to investigate whether MARKs also regulate YAP/TAZ in other types of cancers.

Materials and Methods

TEAD‐luciferase reporter screen

The TEAD‐reporter construct is comprised of tandem TEAD binding sites fused to firefly luciferase as previously described 43. HEK293T cells were seeded on poly‐L‐lysine‐coated 96‐well dishes at 70% confluency. Cells were transfected with 50 ng TEAD reporter, 25 ng of β‐galactosidase, and 100 ng of Flag‐tagged cDNA constructs using Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were lysed 48 h after transfection in 100 μl of lysis buffer (25 mM Tris, 2 mM DTT, 2 mM DCTA, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X‐100). Aliquots of the cell lysates were used to read luciferase and β‐galactosidase activity using a PerkinElmer Envision Xcite multilabel reader. Luciferase activities were normalized to β‐galactosidase activity and fold over run median was determined.

Cell culture and transfection

For cell culturing, HEK293T and 293 T‐REx cells were grown in DMEM with 10% FBS and MDA‐MB‐231 cells in RPMI with 5% FBS. Cells were transfected with Dharmacon siGENOME pools of four individual siRNAs (Thermo Scientific) using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Life Technologies) or with cDNAs, using Lipofectamine 2000, Lipofectamine LTX, or Lipofectamine 3000.

Plasmids and stable cell lines

The MARK construct was generated by PCR using MARK4 isoform 2 (NM_031417) as template and tagged with Flag or HA in either pCMV5 or Gateway destination vectors as specified below. Flag‐ or HA‐tagged constructs for LATS1, MST1, MST2, SAV1, TAZ (WT), and TAZ (S89A) were previously described 33. For MDA‐MB‐231 cells stably expressing TAZ (WT or S89A), HA‐TAZ was subcloned into pCAG‐IRES‐puro vector. The Dox‐inducible Flag‐MARK4 expressing stable cell line was generated using Flp‐In 293 T‐REx cells as previously described 43. Briefly, human MARK4 was subcloned into Triple FLAG Destination vector using Gateway Technology (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and 48 h after transfection, Flp‐In 293 T‐REx cells were cultured in selection media (DMEM with 10% FBS supplemented with 200 μg/ml hygromycin) to generate stable cell lines. Expression of Flag‐MARK4 was induced by overnight doxycycline (1 μg/ml) treatment prior to analysis by immunoblotting or immunofluorescence confocal microscopy.

The CRISPR design tool 54 was used to design MARK4 targeting guide RNAs that were cloned into the px459 plasmid (Addgene #48139 46). Individual MDA‐MB‐231 cell clones were selected using media containing 1 μg/ml puromycin, and loss of MARK4 protein expression was confirmed by immunoblotting.

Immunoblotting, immunoprecipitation, and in vitro kinase assay

Cells were lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X‐100, 1 mM DTT containing phosphatase, and protease inhibitors). Lysates were separated on SDS–PAGE gels, and immunoblotting was performed using standard protocols as previously described 34. For subcellular fractionation experiments, cells were scraped prior to lysis using NE‐PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Reagents (ThermoFisher Scientific #78833). PhosTag gels, using reagents purchased from Waco Chemicals, were prepared according to manufacturer's instructions. For immunoprecipitations, cell lysates were subject to immunoprecipitation with anti‐Flag or target‐specific antibodies as indicated and proteins collected using protein G‐Sepharose prior to analyses by immunoblotting. LUMIER experiments were performed as previously described 31, 32, 33. Briefly, HEK293T cells were transfected with firefly luciferase‐tagged bait and Flag‐tagged prey constructs and were lysed and lysates subjected to anti‐Flag immunoprecipitation. Luciferase activity from the immunoprecipitates and in aliquots of total cell lysates was measured and normalized to β‐galactosidase readings. For in vitro kinase assays, immunoprecipitates were washed three times with kinase assay buffer (100 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2) and then incubated with 0.25 mM DTT, 250 μM ATP, and 200 ng GST‐tagged MARK4 protein purified from Sf9 cells (Sigma #SRP5046) for 30 min in 30°C. The antibodies used were as follows: MST1 (Cell Signaling #3682); MST1/2 (Bethyl Laboratories #A300‐468A); pMST1/2(Thr10/183) (Cell Signaling #3681); MARK4 (Cell Signaling #4834); MARK3 (Cell Signaling #9311); YAP (Cell Signaling #4912); pYAP (Ser127) (D9W2I; Cell Signaling #13008); pYAP (Ser397) (D1E7Y; Cell Signaling #13619); pMOB1 (Thr35) (D2F10; Cell Signaling #8699); TAZ (BD Pharmingen #560235); LATS1 (C66B5; Cell Signaling #3477); pLATS1 (Thr1079) (D57D3; Cell Signaling #8654); rat anti‐HA (Roche #1867423); GST (91G1, Cell Signaling #2625); and anti‐Flag M2 (Sigma‐Aldrich #F1804).

Immunofluorescence confocal microscopy

Cells were plated in 4‐well Lab‐Tek chambers (#154526), fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X‐100 in PBS, and blocked in 2% BSA‐PBS prior to addition of antibodies. Primary antibodies used were mouse anti‐YAP (Santa Cruz #sc‐101199, 1:300); mouse anti‐TAZ (BD Pharmingen #560235, 1:300); rat anti‐HA (Roche #1867423); or rabbit anti‐Flag (Sigma #F7425, 1:500), and secondary antibodies were goat anti‐rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (Life Technologies #A11035, 1:1,000); goat anti‐rat Alexa Fluor 488 (Life Technologies #A11006, 1:1,000); or goat anti‐mouse Alexa Fluor 546 (Life Technologies #A11029, 1:1,000) in 2% BSA‐PBS. Cell nuclei were visualized by DAPI staining. Images were captured using a spinning disk confocal scanner (CSU10, Yokogawa) on Leica DMI6000B microscope, and Volocity software was used for image acquisition and processing. For quantification of YAP localization, a minimum of 30 transfected cells were counted and nuclear/cytoplasmic localization of YAP was evaluated in transfected cells compared to the surrounding non‐transfected cells.

Quantitative real‐time PCR

Total RNA was purified using PureLink RNA Mini Kit (Life Technologies), and cDNA was synthesized using 1 μg of purified RNA using Oligo‐dT primers and M‐MLV Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen #28025‐013). Real‐time PCR was performed using the SYBR Green master mix (Applied Biosystems) on the ABI Prism 7900 HT system (Applied Biosystems). Relative gene expression was quantified by ∆∆C t method and normalized to HPRT. The sequences of the primers used are listed in Table EV1.

Wound healing and cell growth assays

For the wound healing migration assay, cells were seeded in a 6‐well plate and were grown overnight to confluency. The wound was introduced by scraping with a sterile 200 μl pipette tip, and the progress of wound closure was monitored by microphotographs at 10× magnification taken with Zeiss inverted microscope equipped with a CCD camera (Hamamatsu Photonic Systems). The unfilled area was quantified by Volocity at different time points. Cell growth was determined using the SRB assay. For this, cells transfected with siRNAs were plated in 96‐well dishes, fixed at varying times with 10% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid, and then stained as previously described 55.

Statistical tests

For statistical tests performed, P‐values were calculated using Student's two‐tailed t‐test. The number of replicates and independent experiments is indicated in figure legends. Sample size was not predetermined using a statistical method.

Author contributions

AS and LA conceived the project; EHA, AS, and LA designed the experiments; EHA, AS, and SS performed the experiments; EHA, AS, and LA analyzed the data; EHA and LA wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Expanded View Figures PDF

Table EV1

Review Process File

Source Data for Figure 1

Source Data for Figure 2

Source Data for Figure 3

Source Data for Figure 5

Source Data for Figure 6

Source Data for Figure 7

Acknowledgements

We thank Ki Myung Song, Marina Smiley, and Mandeep Gill for preliminary experiments. This work was supported by Grants #133532 and 148455 from Canadian Institute of Health Research and from the Terry Fox Research Institute to L.A. L.A. is Canada Research Chair.

EMBO Reports (2017) 18: 420–436

References

- 1. Halder G, Johnson RL (2011) Hippo signaling: growth control and beyond. Development 138: 9–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Meng Z, Moroishi T, Guan KL (2016) Mechanisms of Hippo pathway regulation. Genes Dev 30: 1–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pan D (2010) The hippo signaling pathway in development and cancer. Dev Cell 19: 491–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Piccolo S, Dupont S, Cordenonsi M (2014) The biology of YAP/TAZ: hippo signaling and beyond. Physiol Rev 94: 1287–1312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ramos A, Camargo FD (2012) The Hippo signaling pathway and stem cell biology. Trends Cell Biol 22: 339–346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Varelas X (2014) The Hippo pathway effectors TAZ and YAP in development, homeostasis and disease. Development 141: 1614–1626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Irvine KD (2012) Integration of intercellular signaling through the Hippo pathway. Semin Cell Dev Biol 23: 812–817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Harvey K, Tapon N (2007) The Salvador–Warts–Hippo pathway—an emerging tumour‐suppressor network. Nat Rev Cancer 7: 182–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Polesello C, Huelsmann S, Brown NH, Tapon N (2006) The Drosophila RASSF homolog antagonizes the Hippo pathway. Curr Biol 16: 2459–2465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Matallanas D, Romano D, Yee K, Meissl K, Kucerova L, Piazzolla D, Baccarini M, Vass JK, Kolch W, O'Neill E (2007) RASSF1A elicits apoptosis through an MST2 pathway directing proapoptotic transcription by the p73 tumor suppressor protein. Mol Cell 27: 962–975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Genevet A, Tapon N (2011) The Hippo pathway and apico‐basal cell polarity. Biochem J 436: 213–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sopko R, McNeill H (2009) The skinny on fat: an enormous cadherin that regulates cell adhesion, tissue growth, and planar cell polarity. Curr Opin Cell Biol 21: 717–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dupont S, Morsut L, Aragona M, Enzo E, Giulitti S, Cordenonsi M, Zanconato F, Le Digabel J, Forcato M, Bicciato S (2011) Role of YAP/TAZ in mechanotransduction. Nature 474: 179–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wada K, Itoga K, Okano T, Yonemura S, Sasaki H (2011) Hippo pathway regulation by cell morphology and stress fibers. Development 138: 3907–3914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schroeder MC, Halder G (2012) Regulation of the Hippo pathway by cell architecture and mechanical signals. Semin Cell Dev Biol 23: 803–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yu F, Zhao B, Panupinthu N, Jewell JL, Lian I, Wang LH, Zhao J, Yuan H, Tumaneng K, Li H (2012) Regulation of the Hippo‐YAP pathway by G‐protein‐coupled receptor signaling. Cell 150: 780–791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sorrentino G, Ruggeri N, Specchia V, Cordenonsi M, Mano M, Dupont S, Manfrin A, Ingallina E, Sommaggio R, Piazza S (2014) Metabolic control of YAP and TAZ by the mevalonate pathway. Nat Cell Biol 16: 357–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. DeRan M, Yang J, Shen C, Peters EC, Fitamant J, Chan P, Hsieh M, Zhu S, Asara JM, Zheng B (2014) Energy stress regulates hippo‐YAP signaling involving AMPK‐mediated regulation of angiomotin‐like 1 protein. Cell Rep 9: 495–503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mo JS, Meng Z, Kim YC, Park HW, Hansen CG, Kim S, Lim DS, Guan KL (2015) Cellular energy stress induces AMPK‐mediated regulation of YAP and the Hippo pathway. Nat Cell Biol 17: 500–510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang W, Xiao ZD, Li X, Aziz KE, Gan B, Johnson RL, Chen J (2015) AMPK modulates Hippo pathway activity to regulate energy homeostasis. Nat Cell Biol 17: 490–499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Enzo E, Santinon G, Pocaterra A, Aragona M, Bresolin S, Forcato M, Grifoni D, Pession A, Zanconato F, Guzzo G et al (2015) Aerobic glycolysis tunes YAP/TAZ transcriptional activity. EMBO J 34: 1349–1370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Santinon G, Pocaterra A, Dupont S (2016) Control of YAP/TAZ activity by metabolic and nutrient‐sensing pathways. Trends Cell Biol 26: 289–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Harvey KF, Zhang X, Thomas DM (2013) The Hippo pathway and human cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 13: 246–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yu F, Zhao B, Guan K (2015) Hippo pathway in organ size control, tissue homeostasis, and cancer. Cell 163: 811–828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhou D, Conrad C, Xia F, Park J, Payer B, Yin Y, Lauwers GY, Thasler W, Lee JT, Avruch J (2009) Mst1 and Mst2 maintain hepatocyte quiescence and suppress hepatocellular carcinoma development through inactivation of the Yap1 oncogene. Cancer Cell 16: 425–438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lu L, Li Y, Kim SM, Bossuyt W, Liu P, Qiu Q, Wang Y, Halder G, Finegold MJ, Lee JS et al (2010) Hippo signaling is a potent in vivo growth and tumor suppressor pathway in the mammalian liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 1437–1442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lee KP, Lee JH, Kim TS, Kim TH, Park HD, Byun JS, Kim MC, Jeong WI, Calvisi DF, Kim JM et al (2010) The Hippo‐Salvador pathway restrains hepatic oval cell proliferation, liver size, and liver tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 8248–8253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhou D, Zhang Y, Wu H, Barry E, Yin Y, Lawrence E, Dawson D, Willis JE, Markowitz SD, Camargo FD et al (2011) Mst1 and Mst2 protein kinases restrain intestinal stem cell proliferation and colonic tumorigenesis by inhibition of Yes‐associated protein (Yap) overabundance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: E1312–E1320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhang N, Bai H, David KK, Dong J, Zheng Y, Cai J, Giovannini M, Liu P, Anders RA, Pan D (2010) The Merlin/NF2 tumor suppressor functions through the YAP oncoprotein to regulate tissue homeostasis in mammals. Dev Cell 19: 27–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cai J, Zhang N, Zheng Y, de Wilde RF, Maitra A, Pan D (2010) The Hippo signaling pathway restricts the oncogenic potential of an intestinal regeneration program. Genes Dev 24: 2383–2388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Barrios‐Rodiles M, Brown KR, Ozdamar B, Bose R, Liu Z, Donovan RS, Shinjo F, Liu Y, Dembowy J, Taylor IW et al (2005) High‐throughput mapping of a dynamic signaling network in mammalian cells. Science 307: 1621–1625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Miller BW, Lau G, Grouios C, Mollica E, Barrios‐Rodiles M, Liu Y, Datti A, Morris Q, Wrana JL, Attisano L (2009) Application of an integrated physical and functional screening approach to identify inhibitors of the Wnt pathway. Mol Syst Biol 5: 315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Varelas X, Miller BW, Sopko R, Song S, Gregorieff A, Fellouse FA, Sakuma R, Pawson T, Hunziker W, McNeill H (2010) The Hippo pathway regulates Wnt/β‐catenin signaling. Dev Cell 18: 579–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Heidary Arash E, Song KM, Song S, Shiban A, Attisano L (2014) Arhgef7 promotes activation of the Hippo pathway core kinase Lats. EMBO J 33: 2997–3011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Drewes G, Ebneth A, Preuss U, Mandelkow E, Mandelkow E (1997) MARK, a novel family of protein kinases that phosphorylate microtubule‐associated proteins and trigger microtubule disruption. Cell 89: 297–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hurov J, Piwnica‐Worms H (2007) The Par‐1/MARK family of protein kinases: from polarity to metabolism. Cell Cycle 6: 1966–1969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tassan J, Goff X (2004) An overview of the KIN1/PAR‐1/MARK kinase family. Biol Cell 96: 193–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mihaylova MM, Shaw RJ (2011) The AMPK signalling pathway coordinates cell growth, autophagy and metabolism. Nat Cell Biol 13: 1016–1023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Shackelford DB, Shaw RJ (2009) The LKB1–AMPK pathway: metabolism and growth control in tumour suppression. Nat Rev Cancer 9: 563–575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wehr MC, Holder MV, Gailite I, Saunders RE, Maile TM, Ciirdaeva E, Instrell R, Jiang M, Howell M, Rossner MJ (2013) Salt‐inducible kinases regulate growth through the Hippo signalling pathway in Drosophila. Nat Cell Biol 15: 61–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Naz F, Anjum F, Islam A, Ahmad F, Hassan MI (2013) Microtubule affinity‐regulating kinase 4: structure, function, and regulation. Cell Biochem Biophys 67: 485–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dumont NA, Wang YX, von Maltzahn J, Pasut A, Bentzinger CF, Brun CE, Rudnicki MA (2015) Dystrophin expression in muscle stem cells regulates their polarity and asymmetric division. Nat Med 21: 1455–1463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Couzens AL, Knight JD, Kean MJ, Teo G, Weiss A, Dunham WH, Lin ZY, Bagshaw RD, Sicheri F, Pawson T et al (2013) Protein interaction network of the mammalian Hippo pathway reveals mechanisms of kinase‐phosphatase interactions. Sci Signal 6: rs15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kim NG, Koh E, Chen X, Gumbiner BM (2011) E‐cadherin mediates contact inhibition of proliferation through Hippo signaling‐pathway components. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 11930–11935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cordenonsi M, Zanconato F, Azzolin L, Forcato M, Rosato A, Frasson C, Inui M, Montagner M, Parenti AR, Poletti A (2011) The Hippo transducer TAZ confers cancer stem cell‐related traits on breast cancer cells. Cell 147: 759–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ran FA, Hsu PD, Wright J, Agarwala V, Scott DA, Zhang F (2013) Genome engineering using the CRISPR‐Cas9 system. Nat Protoc 8: 2281–2308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Avruch J, Zhou D, Fitamant J, Bardeesy N, Mou F, Barrufet LR (2012) Protein kinases of the Hippo pathway: regulation and substrates. Semin Cell Dev Biol 23: 770–784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wu S, Huang J, Dong J, Pan D (2003) Hippo encodes a Ste‐20 family protein kinase that restricts cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis in conjunction with salvador and warts. Cell 114: 445–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Park B, Lee Y (2011) Phosphorylation of SAV1 by mammalian ste20‐like kinase promotes cell death. BMB Rep 44: 584–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Pardo OE, Castellano L, Munro CE, Hu Y, Mauri F, Krell J, Lara R, Pinho FG, Choudhury T, Frampton AE et al (2016) miR‐515‐5p controls cancer cell migration through MARK4 regulation. EMBO Rep 17: 570–584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Huang HL, Wang S, Yin MX, Dong L, Wang C, Wu W, Lu Y, Feng M, Dai C, Guo X et al (2013) Par‐1 regulates tissue growth by influencing hippo phosphorylation status and hippo‐salvador association. PLoS Biol 11: e1001620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hirate Y, Hirahara S, Inoue K, Suzuki A, Alarcon VB, Akimoto K, Hirai T, Hara T, Adachi M, Chida K (2013) Polarity‐dependent distribution of angiomotin localizes Hippo signaling in preimplantation embryos. Curr Biol 23: 1181–1194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mohseni M, Sun J, Lau A, Curtis S, Goldsmith J, Fox VL, Wei C, Frazier M, Samson O, Wong K (2014) A genetic screen identifies an LKB1–MARK signalling axis controlling the Hippo–YAP pathway. Nat Cell Biol 16: 108–117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hsu PD, Scott DA, Weinstein JA, Ran FA, Konermann S, Agarwala V, Li Y, Fine EJ, Wu X, Shalem O (2013) DNA targeting specificity of RNA‐guided Cas9 nucleases. Nat Biotechnol 31: 827–832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Bao R, Christova T, Song S, Angers S, Yan X, Attisano L (2012) Inhibition of tankyrases induces Axin stabilization and blocks Wnt signalling in breast cancer cells. PLoS One 7: e48670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Expanded View Figures PDF

Table EV1

Review Process File

Source Data for Figure 1

Source Data for Figure 2

Source Data for Figure 3

Source Data for Figure 5

Source Data for Figure 6

Source Data for Figure 7