Abstract

Cardiac computed tomography (CT) is most commonly performed for the evaluation of the coronary arteries; however, non-coronary cardiac pathologies are frequently detected on these scans. In cases where magnetic resonance imaging cannot be used, cardiac CT can serve as the first-line imaging modality to evaluate many non-coronary cardiac pathologies. In this article, we discuss congenital non-coronary abnormalities of the left heart and their cardiac CT imaging features.

Keywords: congenital heart diseases, abnormalities of the left heart wall, cardiac computed tomography

Introduction

Cardiac computed tomography (CT) angiography is most commonly used for coronary artery imaging. It also frequently detects non-coronary cardiac and non-cardiac abnormalities. Cardiac abnormalities include congenital or acquired left heart and right heart pathologies. Many if not most left heart pathologies are identified on echocardiography if performed as part of the patient’s work up. However, with the introduction of cross-sectional cardiac imaging methods, CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), some cardiac pathologies have become more readily detectable. This article aims to present the congenital non-coronary abnormalities of the left heart accompanied by cardiac CT images, all of which were obtained from our archive.

Congenital septal defects

In the majority of congenital septal defects, the key CT findings are chamber size, wall integrity, and presence of a contrast jet (1). The diagnosis can be definitively made in cases with disruption of wall integrity. However, because the heart is a mobile organ, it can be difficult to directly detect the disruption. In this situation, evaluation of the chamber size can be useful for determining the presence of a septal defect. In some cases, especially when diagnosing small septal defects by CT, a contrast jet can be observed depending on the scan and contrast injection protocol (Fig. 1). To detect the contrast jet, there should be low or no contrast opacification in the right heart during the scan. This is generally the case in coronary CT, although there is some variation due to center preferences. If the scan is properly timed and the degree of enhancement in the right and left heart is similar, the possibility of a shunt should be considered.

Figure 1.

If a septal defect cannot be directly visualized due to its small size, a contrast jet (arrow) from the opacified left into the unenhanced right atrium will establish the diagnosis like in this patient

Atrial septal defect

Atrial septal defect (ASD) is the most common congenital heart disorder in adults (2). There are four ASD subtypes; primum type ASD (15%), secundum type ASD (70–80%), sinus venosus type ASD (10%), and coronary sinus type ASD (<1%) (3).

The septum primum is the first septum in the fetal heart and develops from the free wall of the atria toward the ventricles. If this septum fails to reach its destination, the defect is called primum type of ASD (Fig. 2). The primum type ASD is less common. This type of ASD sometimes coexists with a ventricular septal defect (VSD), which is then called atrioventricular septal defect or endocardial cushion defect. Endocardial cushion is the area where the interatrial septum, the interventricular septum, and the mitral and the tricuspid valves merge. Endocardial cushion defects are strongly associated with Down syndrome.

Figure 2.

Primum atrial septal defect. Axial coronary CT angiography shows that the interatrial septum does not extend to the junction of the mitral and tricuspid valves, resulting in a defect (arrow) in the basal part of the septum. Note the thin septum in the fossa ovalis (arrow head) which should not be misinterpreted as a secundum ASD

The secundum type ASD is the most common type and is observed in the mid portion of interatrial septum. Septum secundum is the second septum to develop and is located between the two atria and grows in the direction opposite to that of septum primum. If the septum fails to cover ostium secundum, the defect that occurs is called secundum type ASD. Small defects are usually asymptomatic and are detected incidentally. Rarely, large defects may also be asymptomatic and are not detected until adulthood (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

A 68-year-old woman with secundum atrial septal defect. Axial coronary CT angiography image shows a large, incidentally detected defect (arrow) at the midportion of the interatrial septum

A sinus venosus type ASD is a defect in the septum near the openings of the vena cava into the right atrium. It can occur near the superior vena cava (SVC) or inferior vena cava. Superior type sinus venosus ASDs are thought to result from the lack of septation between the pulmonary veins and SVC or right atrium. Superior sinus venosus type ASDs are more common than inferior sinus venosus ASDs and are usually associated with right partial anomalous pulmonary venous return (Fig. 4).

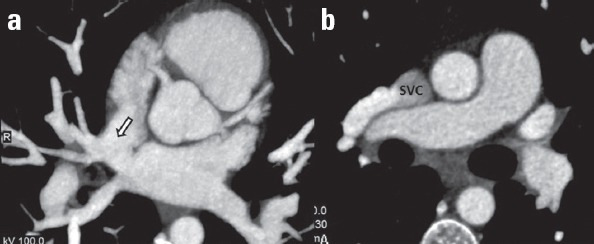

Figure 4.

(a) Axial MIP coronary CT angiography image shows a connection (arrow) between two atria at the level of the opening of the superior vena cava (SVC) to the right atrium. (b) A right pulmonary vein drains into the SVC (known as partial anomalous pulmonary venous return) in the same patient

A coronary sinus type of ASD (unroofed coronary sinus) is not a true interatrial septal defect. Nevertheless, given the right-to-left shunt, it is defined as a subtype of ASD. The coronary sinus is the major coronary vein. It returns the majority of the left ventricular blood flow to the right atrium. This vein is located along the posterior wall of the left atrium. If there is a defect between the left atrium and the coronary sinus (i.e., over the roof), blood will initially pass from the high-pressure left atrium to the coronary sinus and thereafter to the right atrium, thereby leading a left-to-right shunt (Fig. 5). This defect can be associated with atresia of the coronary sinus orifice (Fig. 6).

Figure 5.

Coronary sinus type ASD. Normally, the coronary sinus (CS) is located along the posterior wall of the left atrium and drains into the right atrium (RA). In this case, MPR coronary CT angiography image shows a defect (arrow) between the roof of CS and left atrium (LA)

Figure 6.

A variant of coronary sinus type ASD. (a) MPR coronary CT angiography image shows a defect (arrow) between the roof of coronary sinus and left atrium. (b) Axial coronary CT angiography image shows atresia of coronary sinus orifice (arrow head) in the same patient

ASDs can be associated with other cardiac or extracardiac malformations. Moreover, two different ASD types can occur in the same patient. This anomaly is called complex ASD (Fig. 7).

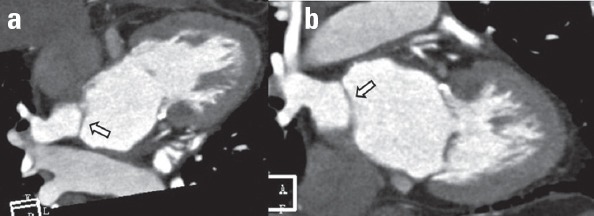

Figure 7.

(a, b) The patient with superior sinus venosus type ASD (arrow head) also has a secundum ASD (arrow). Cases with more than one type of ASD are called complex ASD

Patent foramen ovale

The foramen ovale in the interatrial septum normally develops to the fossa ovalis. This is due to the fusion of the primum septum with the secundum septum occurring at birth, when the lungs become functional; the pulmonary resistance decreases and the pressure in the left atrium exceeds that of the right atrium. A patent foramen ovale (PFO) is the result of incomplete fusion of the septa and is present in up to 25% of adults. Its frequency decreases with age (4). In one of our studies, PFO was observed in 118 (15%) of 782 patients (5). Since the advent of cardiac CT, PFO is more frequently recognized than previously reported. CT shows a channel, filled with contrast medium, between the two septa pointing towards the inferior vena cava. In addition, a contrast jet into the right atrium originating from the left atrium is often observed (Fig. 8). A PFO represents a potential risk factor for stroke due to paradoxical emboli. If the two septa are partially fused, then an interseptal tunnel will occur. This condition is referred as probe-patent PFO or interatrial septal pouch (Fig. 9).

Figure 8.

Patent foramen ovale. (a) Axial and (b) sagittal coronary CT angiography images show the lack of fusion between septum primum (black arrow) and secundum (white arrow) with a contrast-filled channel between them. The direction of the channel is towards the inferior vena cava (IVC). A contrast jet (arrow head) through the gap in the interatrial septum from the left to the right atrium is present

Figure 9.

Coronary CT angiography image shows fusion of the septum primum and secundum in the inferior part (arrow head), and lack of fusion in the proximal part (arrow). In this case, a contrast-filled tunnel in the interatrial septum exists; however, a contrast jet to the right atrium does not occur. This entity is referred as probe patent foramen ovale

Interatrial septal aneurysm

Interatrial septal aneurysms are protrusions of the septum more than 10 mm beyond the plane of the atrial septum (6). They can be caused either by atrial pressure differences or represent a true congenital defect, which can be limited to the fossa ovalis or involve the whole septum (Fig. 10). The aneurysms protrude towards the low pressure side and can be observed during the any phase of the cardiac cycle. Fifty percent of patients with interatrial septal aneurysm also have an ASD or PFO; while 35% of the cases are isolated (7).

Figure 10.

Interatrial septal aneurysm. (a) Coronary CT angiography image shows protrusion (more than 10 mm) of the interatrial septum into the right atrium. (b) In the same patient, a small defect (arrow) in the interatrial septum (secundum atrial septal defect) is also observed

Left atrial diverticulum

Left atrial diverticula are solitary or multiple cystic protuberances that project outward from the atrial wall (Fig. 11). In one of our studies, left atrial diverticula were identified in 186 (41%) of 454 patients (8). They are not usually associated with other cardiac abnormalities. The etiology and pathophysiology of left atrial diverticula are not clearly understood. Congenital and acquired etiologies have been suggested by many researchers. Although previous studies have identified variable locations, the most commonly reported location of left atrial diverticula is the anterior superior part of the left atrium. The least common location is the posterior wall (8). They are generally asymptomatic; however, they can be associated with arrhythmias, thromboembolism, and mitral valve regurgitation (9). They can be sources of emboli in patients with cryptogenic stroke and they can cause potential complications such as catheter trap, wall penetration, and atrial-esophageal fistula during radiofrequency catheter ablation procedures (10).

Figure 11.

(a) Coronary CT angiography image shows a diverticulum (black arrow) with a wide neck and smooth contours projecting outward from the inferior part of the left atrium wall. (b) Multiple left atrial diverticula (white arrows) are seen in a different patient

Accessory left atrial appendage

Accessory left atrial appendages are small outpouchings of the left atrial wall (Fig. 12) that occur with an incidence of 10–27% in the general population (11). However, in one of our studies, left accessory appendages were detected in 14 (3.1%) of 454 patients (8). They are usually not associated with other congenital cardiac abnormalities. Accessory left atrial appendages are characterized by the presence of trabeculated myocardium with the same wall structure as the surrounding myocardium (12). The most common location of an accessory left atrial appendage is along the anterosuperior left atrial wall to the right aspect of the left atrium. Thrombosis can occur within accessory appendages, and they can be possible sources of cardiogenic emboli. The presence of accessory left atrial appendages should be identified prior to radiofrequency catheter ablation procedures, because their orifice may resemble the orifice of a pulmonary vein. Therefore, reporting accessory appendages and the presence or absence of thrombus is important (13). Accessory left atrial appendages may be misinterpreted as left atrial diverticula. The presence of a wide neck and a smooth interior favors the diagnosis of a left atrial diverticulum. They can also coexist in the same patient (Fig. 13).

Figure 12.

Coronary CT angiography image shows accessory left atrial appendage (arrow head) in addition to the normal left atrial appendage (arrow). Note the narrow neck and internal trabeculation of the accessory appendage

Figure 13.

Coronary CT angiography image shows the co-existence of an accessory left atrial appendage (arrow) and left atrial diverticulum (arrow head) in the same patient. Left atrial diverticula have a wider neck and smoother contours compared to accessory left atrial appendages

Cor Triatriatum

Cor triatriatum is a congenital cardiac anomaly in which the left or right atrium is divided into two compartments by a fibromuscular membrane (Fig. 14). Although it is more frequent in the left atrium (cor triatriatum sinister), they occur in the right atrium as well (cor triatriatum dexter). The severity of clinical symptoms depends on the size of the fenestration in the membrane. It could be associated with other cardiac or extracardiac anomalies (14).

Figure 14.

Coronary CT angiography images show a thin membrane (arrows), which divides the left atrium into two compartments in a patient with cor triatriatum

Ventricular septal defect

VSDs are the most common cardiac malformation. The interventricular septum is divided into two parts; the thin membranous basal portion beneath the aortic valve and the larger muscular septum. They are usually congenital, but can also be the result of myocardial infarction or trauma. Approximately 50% of congenital VSDs are small and close spontaneously (15).

VSDs are divided into four types (16). In type 1 (outlet or supracristal type) VSD, the defect is located between the right ventricular outflow tract and the aorta. It represents 5–7% of VSDs. This type is often associated with aortic regurgitation due to prolapse of the anterior aortic valve leaflet.

Type 2 is the most common type and represents 70% of all VSDs. It involves the membranous septum. It is also called perimembranous type VSD, because the adjacent septum surrounding the membranous defect also contains defects to varying degrees (Fig. 15). In some cases, this type of VSD closes spontaneously and a sac called a ventricular septal aneurysm or a spontaneous closure VSD occurs (Fig. 16). It is defined as a bowing of the septum greater than 10–15 mm to either side (17). It can be associated with conduction arrhythmias. Association with other cardiac defects has also been reported (18, 19).

Figure 15.

Type 2 ventricular septal defect (VSD). Coronary CT angiography image shows a defect (arrow) in the membranous septum. This condition is referred as partially closed membranous VSD

Figure 16.

Axial and sagittal coronary CT angiography images show protuberance of the interventricular septum into the right ventricle (arrows) in the location of the membranous septum. This condition is termed a ventricular septal aneurysm and is related to the spontaneous closure of a perimembranous ventricular septal defect

Type 3 (inlet type) VSDs are located in the inlet of the ventricular septum immediately inferior to the AV valve apparatus (Fig. 17). This is the rarest type of VSD with a frequency of 5% or less. Defects in the inlet septum can include abnormalities of the tricuspid and mitral valves that are called common atrioventricular canal defect (20).

Figure 17.

Type 3 (inlet type) ventricular septal defect (VSD). Coronary CT angiography image shows a VSD (arrow) at the inlet septum beneath the septal leaflet of the tricuspid valve (TV) (MV-mitral valve)

Type 4 (muscular) VSDs occur in 20% of the cases and involve the muscular part of the interventricular septum (Fig. 18). About 75% of type 4 VSDs close spontaneously before age 2. Type 4 VSDs that fail to close are generally benign. In some cases, multiple defects may be present and produce a “Swiss cheese” appearance of the septum.

Figure 18.

Type 4 ventricular septal defect. Coronary CT angiography image shows a defect (arrow) in the apical segment of the muscular interventricular septum

Ventricular cleft

Ventricular clefts are also known as myocardial crypts or myocardial fissures; they are defined as V-shaped, single or multiple gaps penetrating more than 50% of the thickness of the adjoining compact myocardium in long-axis views (21). They are fissure-like protrusions confined to compacted myocardium, which do not exceed beyond the myocardial margin (Fig. 19). In one study, we detected left ventricular clefts in 24 (3.05%) of 786 patients (22). They are commonly seen in the basal inferior wall of the left ventricle and the mid to apical segments of the interventricular septum. Multiple clefts may be present in some cases (Fig. 20). It was previously believed that they have no clinical significance; however they have been recently found to be associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) mutation carriership (23, 24). Clefts should be differentiated from diverticula, which can be associated with cardiac complications (23).

Figure 19.

Coronary CT angiography image shows a ventricular cleft (arrow) in the interventricular septum of the left ventricle

Figure 20.

Coronary CT angiography image shows multiple ventricular clefts (arrow) in the interventricular septum, which are connected to the left ventricle

Left ventricular diverticulum

Left ventricular diverticula are congenital abnormalities of the myocardium that are characterized by an outpouching of the myocardium in its entire thickness, and extension beyond the confines of the anatomic left ventricular cavity and myocardial margin (25). This appearance can be used to differentiate diverticula from clefts, which are fissure-like protrusions that are confined to the myocardium and left ventricular wall. Left ventricular diverticula are most commonly found in the apical portion of the left ventricle and can be associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (26) (Fig. 21). In one of our studies, a total of 786 consecutive MDCT coronary angiography examinations were reviewed retrospectively and apical diverticula were observed in 9 patients (1.14% prevalence) (22). They are usually asymptomatic and found incidentally during diagnostic procedures. However, they have been reported to be associated with heart failure, systemic embolization, ventricular wall rupture, or arrhythmias (23).

Figure 21.

Coronary CT angiography image shows a diverticulum (arrow) in the apical segment of the left ventricle in a patient with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. A very thin left ventricular myocardium confining the diverticular sac is observable

Left ventricular non-compaction

Left ventricular non-compaction (LVNC) is a rare congenital myocardial disorder that is characterized by a thin, compacted epicardial layer and an extensive non-compacted endocardial layer, with prominent myocardial trabeculations and deep intertrabecular recesses that communicate with the left ventricular cavity (27). It is caused by the intrauterine arrest of the myocardial compaction process (Fig. 22). Patients may be asymptomatic or present with dyspnea, systolic dysfunction, arrhythmias, and embolic events secondary to atrial fibrillation. Non-compaction typically involves the left ventricle, although involvement of the right ventricle has also been reported (28). The non-compacted areas are most commonly found in the apical and lateral portions of the left ventricle. CT can show the typical two-layered myocardium of the left ventricle with prominent myocardial trabeculations. In a previous study, Melendez-Ramirez et al. (29) have proposed CT diagnostic criteria for LVNC, and that a noncompaction-to-compaction ratio greater than 2.2 in at least two segments can be considered to be diagnostic of LVNC.

Figure 22.

Coronary CT angiography image shows that the ratio of non-compacted myocardium (NCM) to compacted myocardium (CM) is approximately 2.5 in the left ventricle in a patient with left ventricular non-compaction

Conclusion

Cardiac CT is a powerful imaging modality for the evaluation of congenital non-coronary left heart abnormalities. Due to their clinical implications, their consideration is important not only for every physician interpreting coronary and cardiac CT scans but also for every general radiologist, as many of these entities can also be seen on high quality chest CT angiography and chest CT studies.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Authorship contributions: Concept – E.Ö.; Design – C.K.; Supervision – K.D.H.; Data collection &/or processing – E.Ö., U.B.; Analysis and/or interpretation – S.T.; Literature search – C.K., S.T.; Writing – E.Ö.; Critical review – U.B.

References

- 1.Chu LC, Johnson PT, Fishman EK. Cardiac CT angiography beyond the coronary arteries:what radiologists need to know and why they need to know it. AJR Am J Roengenol. 2014;203:583–95. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.12400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brickner ME, Hillis D, Lange RA. Congenital heart disease in adults. First of two parts. N Eng J Med. 2000;342:256–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001273420407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Navallas M, Orenes P, Sanchez Nistal MA, Jimenez Lopez Guarch C. Congenital heart disease in adults:The contribution of multidetector CT. Radiologia. 2010;52:288–300. doi: 10.1016/j.rx.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hagen PT, Scholz DG, Edwards WD. Incidence and size of patent foramen ovale during the first 10 decades of life:An autopsy study of 965 normal hearts. Mayo Clin Proc. 1984;59:17–20. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)60336-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kara K, Sivrioğlu AK, Öztürk E, İncedayı M, Sağlam M, Arıbal S, et al. The role of coronary CT angiography in diagnosis of patent foramen ovale. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2016;22:341–6. doi: 10.5152/dir.2016.15570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mügge A, Daniel WG, Angermann C, Spes C, Khandheria BK, Kronzon I, et al. Atrial septal aneurysm in adult patients:a multicenter study using transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography. Circulation. 1995;91:2785–92. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.11.2785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giannopoulos A, Gavras C, Sarıoğlou S, Agathagelou F, Kassapoglou I, Athanassiasour F. Atrial septal aneurysms in childhood:prevalence, classification and concurrent abnormalities. Cardiol Young. 2014;24:453–8. doi: 10.1017/S1047951113000607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.İncedayı M, Öztürk E, Sönmez G, Sağlam M, Sivrioğlu AK, Mutlu H, et al. The incidence of left atrial diverticula in coronary CT angiography. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2012;18:542–6. doi: 10.4261/1305-3825.DIR.5388-11.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.GençB Solak A, Kantarcı M, Bayraktutan U, Oğul H, Yüceler Z, et al. Anatomical features and clinical ımportance of left atrial diverticula:MDCT findings. Clin Anat. 2014;27:738–47. doi: 10.1002/ca.22320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goncalves A, Marcos-Alberca P, Zamorano JL. Left atrium wall diverticulum:an additional anatomical consideration in atrial fibrillation catheter ablation. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2164. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abbara S, Mundo-sagardia JA, Hoffmann U, Cury RC. Cardiac CT assessment of left atrial accessory appendages and diverticula. AJR Am J Roengenol. 2009;193:807–12. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Igawa O, Miake J, Adachi M. The small diverticulum in the right anterior wall of the left atrium. Europace. 2008;10:120. doi: 10.1093/europace/eum275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lazoura O, Reddy T, Shriharan M, Lindsay A, Nicol E, Rubens M, et al. Prevalance of left atrial anatomical abnormalities in patients with recurrent atrial fibrillation compared with patient sinus rhythm using multi-slice CT. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2012;6:268–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tutar S, Öztürk E, Kafadar C, Kara K. Cor triatriatum sinistrum with pulmonary vein atresia. Int J Cardiol. 2015;203:15–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu Y, Liu J, Wang J, Liu M, Xu H, Yang S. Factors influencing the spontaneous closure of ventricular septal defect in infants. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:5614–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soto B, Becker AE, Moulaert AJ, Lie JT, Anderson RH. Classification of ventricular septal defects. Br Heart J. 1980;43:332–43. doi: 10.1136/hrt.43.3.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dodd JD, Aquino SL, Holmvang G, Cury RC, Hoffmann U, Brady TJ, et al. Cardiac septal aneurysm mimicking pseudomass:appearance on ECG-gated cardiac MRI and MDCT. AJR Am J Roengenol. 2007;188:550–3. doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.0996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horne D, White CW, MacKenzie GS, Kirkpatrick IDC, Freed DH. Adult presentation with a bilobed membranous ventricular septal aneurysm. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29:893–3. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramaciotti C, Keren A, Silverman NH. Importance of (perimembranous) ventricular septal aneurysm in the natural history of isolated perimembranous ventricular septal defect. Am J Cardiol. 1986;57:268–72. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(86)90903-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minette MS, Sahn DJ. Ventricular septal defects. Circulation. 2006;114:2190–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.618124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johansson B, Maceira AM, Babu-Narayan SV, Moon JC, Pennell DJ, Kilner PJ. Clefts can be seen in the basal inferior wall of the left ventricle and the interventricular septum in healthy volunteers as well as patients by cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1294–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Öztürk E, Sağlam M, Sivrioğlu AK, Kara K. Left ventricular clefts and diverticula. Eur J Radiol. 2013;82:e628. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohlow MA. Congenital left ventricular aneurysms and diverticula:definition, pathophysiology, clinical relevance and treatment. Cardiology. 2006;106:63–72. doi: 10.1159/000092634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brouwer WP, Germans T, Head MC, van der Velden J, Heymans MW, Christiaans I, et al. Multiple myocardial crypts on modified long-axis view are a specific finding in pre-hypertrophic HCM mutation carriers. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;13:292–7. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jes005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Afonso L, Kottam A, Khetarpal V. Myocardial cleft, crypt, diverticulum, or aneurysm? Does it really matter? Clin Cardiol. 2009;32:48–51. doi: 10.1002/clc.20466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sivrioğlu AK, Sağlam M, Öztürk E, İncedayı M, Sönmez G, Mutlu H, et al. Association between myocardial hypertrophy and apical diverticulum:more than a coincidence? Diagn Interv Radiol. 2013;19:400–4. doi: 10.5152/dir.2013.13166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chin TK, Perloff JK, Williams RG, Jue K, Mohrmann R. Isolated noncompaction of left ventricular myocardium. A study of eight cases. Circulation. 1990;82:507–13. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.2.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee H, Kim SY, Schoepf UJ. Isolated non-compaction of the left ventricle in a patient with new-onset heart failure:morphologic and functional evaluation with cardiac multidetector computed tomography. Korean J Radiol. 2012;13:244–8. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2012.13.2.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melendez-Ramirez G, Castillo-Castellon F, Espinola-Zavaleta N, Meave A, Kimura-Hayama ET. Left ventricular noncompaction:a proposal of new diagnostic criteria by multidetector computed tomography. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2012;6:346–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]