ABSTRACT

The cytidine deaminase APOBEC3B (A3B) underlies the genetic heterogeneity of several human cancers, including cervical cancer, which is caused by human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. We previously identified a region within the A3B promoter that is activated by the viral protein HPV16 E6 in human keratinocytes. Here, we discovered three sites recognized by the TEAD family of transcription factors within this region of the A3B promoter. Reporter assays in HEK293 cells showed that exogenously expressed TEAD4 induced A3B promoter activation through binding to these sites. Normal immortalized human keratinocytes expressing E6 (NIKS-E6) displayed increased levels of TEAD1/4 protein compared to parental NIKS. A series of E6 mutants revealed that E6-mediated degradation of p53 was important for increasing TEAD4 levels. Knockdown of TEADs in NIKS-E6 significantly reduced A3B mRNA levels, whereas ectopic expression of TEAD4 in NIKS increased A3B mRNA levels. Finally, chromatin immunoprecipitation assays demonstrated increased levels of TEAD4 binding to the A3B promoter in NIKS-E6 compared to NIKS. Collectively, these results indicate that E6 induces upregulation of A3B through increased levels of TEADs, highlighting the importance of the TEAD-A3B axis in carcinogenesis.

IMPORTANCE The expression of APOBEC3B (A3B), a cellular DNA cytidine deaminase, is upregulated in various human cancers and leaves characteristic, signature mutations in cancer genomes, suggesting that it plays a prominent role in carcinogenesis. Viral oncoproteins encoded by human papillomavirus (HPV) and polyomavirus have been reported to induce A3B expression, implying the involvement of A3B upregulation in virus-associated carcinogenesis. However, the molecular mechanisms causing A3B upregulation remain unclear. Here, we demonstrate that exogenous expression of the cellular transcription factor TEAD activates the A3B promoter. Further, the HPV oncoprotein E6 increases the levels of endogenous TEAD1/4 protein, thereby leading to A3B upregulation. Since increased levels of TEAD4 are frequently observed in many cancers, an understanding of the direct link between TEAD and A3B upregulation is of broad oncological interest.

KEYWORDS: APOBEC3B, E6, TEAD, papillomavirus

INTRODUCTION

Cervical cancer is primarily associated with oncogenic (high-risk) human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. The most prevalent high-risk genotype is HPV16, accounting for more than half of cervical cancer cases worldwide (1). The key viral proteins that drive carcinogenesis are E6 and E7, which bind to and degrade p53 and Rb, respectively, thereby inhibiting apoptosis and promoting cell cycle progression (2). Although continuous expression of E6 and E7 is sufficient to immortalize and transform cervical epithelial cells, the accumulation of somatic mutations and/or gain of chromosomal abnormalities in the host genome is also required to generate invasive cervical cancer with a malignant phenotype, generally occurring after years of persistent HPV infection (3).

Recent genomics studies in various human cancers have identified somatic mutation patterns, termed signatures, that can be attributed to specific mutagens (4–7). Among the signatures deciphered, C-to-T or C-to-G substitutions are enriched in the genomes of several cancers, such as breast, bladder, head and neck, and cervical cancers (4–9). These mutation patterns are best explained by the action of the apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme, catalytic polypeptide-like (APOBEC) family of proteins, which convert cytosine to uracil in single-stranded DNA exposed during DNA replication. Uracil bases in single-stranded DNA are often excised by uracil N-glycosidase, generating abasic sites. Adenines or cytosines are inserted opposite the abasic sites by error-prone DNA polymerases, resulting in C-to-T or C-to-G substitutions (8). Among the 11 members of the APOBEC protein family (AID and APOBEC1, -2, -3A, -3B, -3C, -3D, -3F, -3G, -3H, and -4), APOBEC3B (A3B) is the most likely candidate for the cancer-associated APOBEC (4–9) because it is localized predominantly in the nucleus and upregulated in many cancer tissues (5–7).

Recently, an intriguing connection between E6/E7 expression and A3B upregulation during HPV-associated carcinogenesis has been proposed (10–13). Warren et al. demonstrated that A3A and A3B are upregulated in low- and high-grade cervical lesions compared with normal tissue. This upregulation is also observed in human keratinocytes harboring the HPV16 genome with an intact E7 gene (10). Vieira et al. reported that high-risk type E6 has the capacity to induce A3B expression (11). Another study showed that HPV-positive head and neck cancers harbor more APOBEC-associated mutational signatures and increased levels of A3B mRNA compared to their HPV-negative counterparts (12). Further, it has been demonstrated that A3B upregulation is more frequently detected in breast cancer tissues where high-risk HPV DNA is also detected, suggesting a potential link between HPV infection and A3B induction in breast carcinogenesis (13). A3B upregulation was also reported for BK polyomavirus (BKPyV) infection, and large T antigens of BKPyV and related human polyomaviruses can induce A3B expression (14), implying that A3B upregulation may contribute to PyV-associated tumorigenesis.

The fact that A3B is upregulated in many cancers has led to an important question regarding how A3B expression is regulated in both normal and cancer cells. A recent study demonstrated that activation of the protein kinase C/NF-κB signaling pathway induces A3B expression in breast cancer cell lines (15). The mechanism of A3B upregulation in HPV-associated cancer, however, has yet to be elucidated. We recently reported that HPV16 E6 activates the A3B promoter in human keratinocytes and identified two promoter regions (distal and proximal regions) that are responsible for E6-mediated activation (16). The proximal region (+1/+45) in the A3B promoter normally exerts an inhibitory effect on A3B gene expression, and E6 seems to relieve this inhibition through the regulatory functions of the cellular zinc finger protein ZNF384. The distal region (−200/−51) also contains E6-responsive elements, although the molecular mechanisms behind A3B promoter activation through this region remain undefined.

TEAD family proteins (in mammals, TEAD1, TEAD2, TEAD3, and TEAD4) are evolutionarily conserved transcription factors that recognize the consensus DNA sequence (AGGAATG) designated the MCAT motif (17, 18). TEADs are not sufficient to activate transcription and require coactivators to induce transcription of target genes (18–20). Among the most prominent coactivators for TEADs are the Yes-associated protein (YAP) and its paralog, transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif (TAZ) (18, 19). TEADs and YAP/TAZ are the integral components of the Hippo pathway, which regulates organ size through the regulation of cell proliferation and apoptosis (21). YAP overexpression has been reported in many cancers, including cervical cancer (22–26). Recently, He et al. reported that high levels of YAP are associated with poor cancer prognosis and that HPV16 E6 stabilizes and upregulates YAP (26). This suggests that E6-mediated dysregulation of the Hippo pathway plays an important role in HPV-induced carcinogenesis.

Here, we extend our analysis of the −200/−51 region of the A3B promoter to unravel the molecular mechanisms of A3B upregulation by E6. Our results strongly support the involvement of TEAD transcription factors in E6-mediated A3B upregulation.

RESULTS

Activation of the A3B promoter by TEAD4.

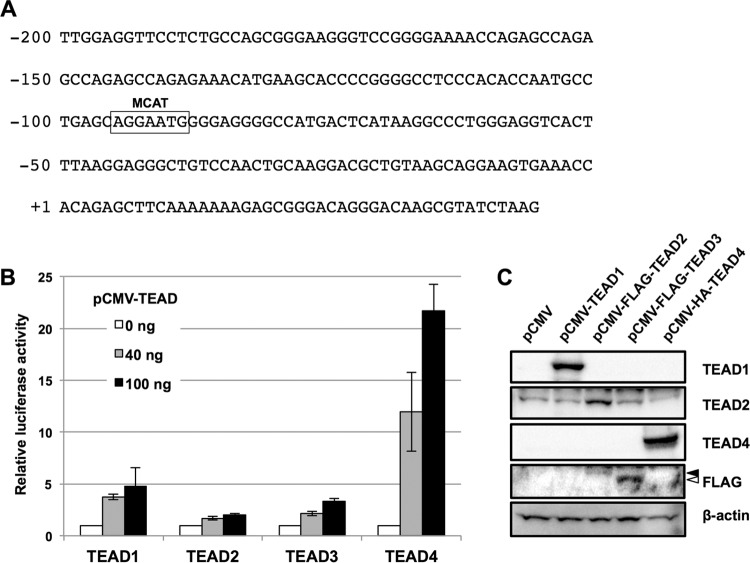

We previously showed that the A3B promoter region, from −200 to −51 (−200/−51), is responsible for E6-mediated A3B transactivation in normal immortal human keratinocytes (NIKS) expressing HPV16 E6 (NIKS-E6) (16). Bioinformatics searches for transcription factor binding motifs in the −200/−51 region highlighted a sequence from −95 to −89 that completely matched a consensus motif recognized by the TEAD family of transcription factors, the MCAT motif (Fig. 1A). We used a luciferase reporter assay to determine if TEADs activate the −200/−51 region of the A3B promoter in HEK293 cells. We found that ectopic expression of TEAD1, -2, -3, or -4 was sufficient to activate the A3B promoter (Fig. 1B and C). We further explored A3B promoter activation by TEAD4, which showed the most prominent effect in the reporter assay.

FIG 1.

Activation of the A3B promoter by TEADs. (A) Nucleotide sequence of the −200/+45 region of the A3B promoter. The consensus binding motif for TEADs (MCAT) is boxed. The numbering of nucleotide positions is based on the Transcriptional Regulatory Element Database sequence (accession number 28319) (39). (B) HEK293 cells were transfected with the indicated amounts of the expression plasmid for TEADs, together with the A3B reporter plasmid (pA3B−200/+45) and the Renilla luciferase plasmid. Two days after transfection, the firefly luciferase activity was determined, with normalization to the Renilla luciferase activity. The levels of luciferase activity are presented as fold increase compared with that obtained from cells transfected with pA3B−200/+45 without the TEAD expression plasmid. The data are the averages of three independent experiments, with the error bars representing standard deviations. (C) HEK293 cells transfected with the expression plasmid for TEADs were analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-TEAD1, anti-TEAD2, anti-TEAD4, and anti-FLAG antibodies. β-Actin was used as the loading control. The solid and open arrowheads indicate the positions of FLAG-TEAD2 and FLAG-TEAD3 detected by anti-FLAG antibody, respectively.

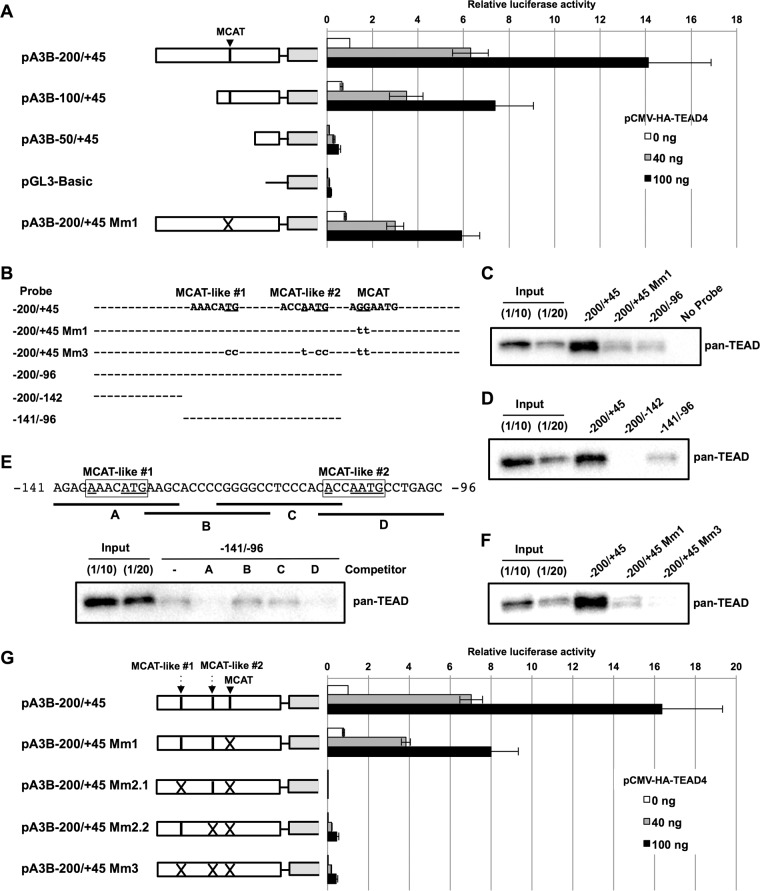

We first performed a deletion analysis of the A3B promoter to determine the TEAD-responsive region(s). Activation of the A3B promoter by TEAD4 was reduced somewhat by deletion of the −200/−101 region (pA3B−100/+45) and was completely abrogated by further deletion of the −100/−51 region containing the MCAT motif (pA3B−50/+45) (Fig. 2A). These data suggest that the MCAT motif located within the −100/−51 region is involved in TEAD4-mediated transactivation of the A3B promoter. Indeed, introducing mutations into the MCAT motif (pA3B−200/+45 Mm1) weakened promoter activation by TEAD4 by about 50% (Fig. 2A). Further, in vitro DNA pulldown assays showed that a DNA probe containing the −200/+45 region of the A3B promoter efficiently bound to TEADs in nuclear extracts from NIKS-E6 cells (Fig. 2B and C, −200/+45). In contrast, a probe containing the mutated MCAT motif exhibited reduced binding affinity for TEADs (Fig. 2B and C, −200/+45 Mm1), strongly suggesting that TEADs bind to the MCAT motif. Thus, the MCAT motif from −95 to −89 is recognized by TEADs and is required for full activation of the A3B promoter.

FIG 2.

Mutational analyses of the MCAT motif and MCAT-like sequences by reporter and in vitro DNA pulldown assays. (A) HEK293 cells were transfected with the indicated firefly luciferase reporter plasmid, together with the indicated amounts of the expression plasmid for TEAD4 (pCMV-HA-TEAD4) and the Renilla luciferase plasmid. Two days after transfection, the firefly luciferase activity was measured and normalized to the Renilla luciferase activity. The levels of luciferase activity are presented as fold increase compared with that obtained from cells transfected with pA3B−200/+45 without the TEAD4 expression plasmid. The data are the averages of three independent experiments, with the error bars representing standard deviations. (B) Schematic representation of the biotinylated DNA probes used in DNA pulldown assays. The positions and nucleotide sequences of MCAT-like 1 and 2 and MCAT are shown. The mutated nucleotides are underlined, and the nucleotide sequences in the mutated probes are denoted by lowercase letters. (C to F) The indicated biotinylated DNA probes were coupled to Dynabeads/M-280 streptavidin and incubated with the nuclear extract from NIKS-E6; 1/10 or 1/20 volume of input (Input) and entire precipitated fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-pan-TEAD antibody. (E) Unlabeled oligonucleotide competitors (lines A to D) indicated by the solid lines under the nucleotide sequence of the −141/−96 probe were added to the reaction mixtures, and inhibition of TEADs binding to the −141/−96 probe was examined. The MCAT-like sequences 1 and 2 are boxed, and nucleotides that match the typical MCAT motif are underlined. (G) HEK293 cells were transfected with the indicated firefly luciferase reporter plasmid, together with the indicated amounts of pCMV-HA-TEAD4 and the Renilla luciferase plasmid, and the luciferase activity was measured as described for panel A.

Given that deletion of the −200/−101 region reduced reporter activity (Fig. 2A) and that a small amount of TEADs still bound to the −200/+45 Mm1 probe (Fig. 2C), we hypothesized that the A3B promoter contains an additional target site(s) for TEADs. We first performed DNA pulldown assays to determine if TEADs bind to other regions within the A3B promoter. As shown in Fig. 2C, we observed similar levels of TEAD binding for the −200/+45 Mm1 and −200/−96 probes, suggesting that the −200/−96 region contains a potential TEAD-binding site(s). We divided the −200/−96 probe into two nonoverlapping regions (Fig. 2B, −200/−142 and −141/−96) and detected TEAD binding to the −141/−96 probe (Fig. 2D), indicating the presence of TEAD-binding site(s) within the region.

To further pinpoint the TEAD target sequence(s), we designed four overlapping oligonucleotides covering the entire −141/−96 region (Fig. 2E) for use as competitors for TEAD binding in the DNA pulldown assays. As shown in Fig. 2E, TEAD binding was effectively inhibited in the presence of oligonucleotide A or D, indicating that the −141/−127 (A) and −110/−96 (D) regions within the A3B promoter contain a TEAD-binding site(s). Although these two regions do not contain a canonical MCAT motif (AGGAATG), we identified two sequences within the A and D oligonucleotides that partially match the MCAT motif, which we designated MCAT-like 1 (AAACATG) and 2 (ACCAATG) (Fig. 2E). Mutating both the MCAT-like sequences, as well as the MCAT motif (Fig. 2B, −200/+45 Mm3) almost entirely abrogated TEAD binding in the pulldown assay (Fig. 2F), suggesting that these three sites represent all the TEAD-binding sites within the −200/+45 A3B promoter. Intriguingly, mutating MCAT-like 1 and/or 2 in pA3B−200/+45 Mm1 (Fig. 2G, pA3B−200/+45 Mm2.1, Mm2.2, and Mm3) completely abolished A3B promoter activation by TEAD4 in the reporter assay, indicating that at least one MCAT-like sequence, in addition to the MCAT motif, is critical for TEAD-mediated A3B promoter activation.

Effects of YAP on A3B promoter activation.

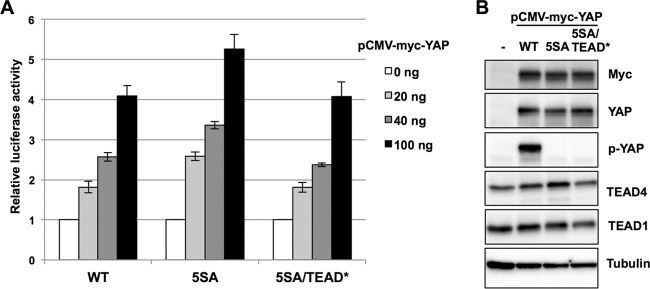

Next, we determined if the Yes-associated protein (YAP), a major transcriptional coactivator for TEADs, could activate the A3B promoter in reporter assays. In contrast to the strong activation observed with TEAD4, overexpression of Myc-tagged YAP (Myc-YAP) in HEK293 cells induced only modest activation of the reporter (about 4-fold after transfection of 100 ng pCMV-Myc-YAP) (Fig. 3A and B). A constitutively active YAP mutant, whose phosphorylatable serine residues were all replaced with alanine (5SA) to enforce its nuclear localization, induced slightly higher activation (about 5-fold after transfection of 100 ng pCMV-Myc-YAP-5SA), but this effect was abrogated with a TEAD interaction-defective mutant (5SA/TEAD*). Cells overexpressing Myc-YAP-WT (wild type) and -5SA, but not -5SA/TEAD*, displayed increased TEAD4 protein levels by Western blotting analyses (Fig. 3B); less apparent effects were found for TEAD1 protein levels (Fig. 3B). These observations suggest that the moderate YAP-mediated activation of the A3B promoter is caused by increased TEAD4 levels, although a coactivator function of YAP for TEAD4 was not totally excluded. The correlation between TEAD4 levels and reporter activation in cells overexpressing TEAD4 or YAP suggests that the TEAD4 level is a critical limiting factor for A3B promoter activation.

FIG 3.

Activation of the A3B promoter by YAP. (A) HEK293 cells transfected with the indicated amounts of the expression plasmid for Myc-tagged YAP and its mutants, together with the A3B reporter plasmid (pA3B−200/+45) and the Renilla luciferase plasmid, were analyzed as described in the legend to Fig. 1. The levels of luciferase activity are presented as the fold increase compared with that obtained from cells without the YAP expression plasmid. The data are the averages of three independent experiments, with the error bars representing standard deviations. WT, wild type YAP; 5SA, constitutively active mutant of YAP; 5SA/TEAD*, 5SA with a mutated TEAD-binding domain. (B) HEK293 cells transfected with the expression plasmid for Myc-tagged YAP and its mutants were analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-Myc, anti-YAP, anti-phospho-YAP, anti-TEAD1, and anti-TEAD4 antibodies. Tubulin was used as the loading control.

TEADs are upregulated in human keratinocytes expressing E6.

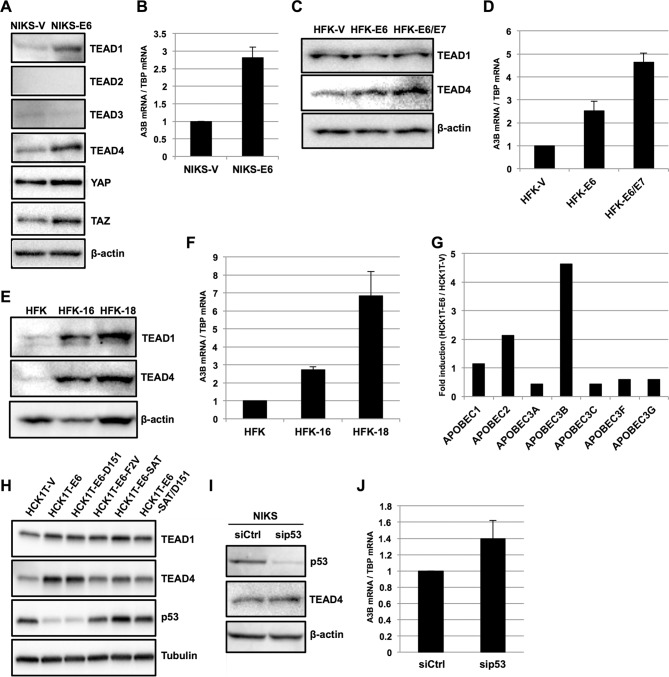

The TEAD-mediated activation of the −200/−51 region of the A3B promoter prompted us to explore whether E6 expression increases the levels of TEAD proteins in NIKS, leading to A3B upregulation. We detected TEAD1, TEAD3, and TEAD4 in NIKS transduced with an empty retroviral vector (NIKS-V) by Western blotting, although the levels of TEAD3 were faint compared to those of TEAD1 and TEAD4 (Fig. 4A). Compared to NIKS-V, NIKS transduced with an E6 retroviral vector (NIKS-E6) displayed upregulation of A3B mRNA by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) (Fig. 4B), as well as increased protein levels of TEAD1, TEAD4, YAP, and the coactivator TAZ by Western blotting (Fig. 4A). In contrast, no increase in TEAD3 levels was observed in NIKS-E6 cells compared to NIKS-V cells by Western blotting. Thus, overexpression of E6 in NIKS leads to upregulation of TEAD1 and TEAD4 proteins.

FIG 4.

Expression of A3B mRNA and TEAD proteins in human keratinocytes expressing E6. (A) NIKS-V and NIKS-E6 were analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-TEAD1, anti-TEAD2, anti-TEAD3, anti-TEAD4, anti-YAP, and anti-TAZ antibodies. β-Actin was used as the loading control. (B) The levels of A3B mRNA in NIKS-V or NIKS-E6 were determined by RT-qPCR and normalized to the level of TBP mRNA. The data are the averages of three independent experiments, with the error bars representing standard deviations. (C) HFK expressing E6 (HFK-E6), E6/E7 (HFK-E6/E7), or a selection marker alone (HFK-V) were analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-TEAD1 and anti-TEAD4 antibodies. β-Actin was used as the loading control. (D) The levels of A3B mRNA in HFK-V, HFK-E6, or HFK-E6/E7 were determined by RT-qPCR and normalized to the level of TBP mRNA. The levels of A3B mRNA are presented as relative levels compared to those in HFK-V. The data are the averages of three independent experiments, with the error bars representing standard deviations. (E) HFK with an episomal HPV16 (HFK-16) or HPV18 (HFK-18) genome were analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-TEAD1 and anti-TEAD4 antibodies. β-Actin was used as the loading control. (F) The levels of A3B mRNA in HFK, HFK-16, and HFK-18 were determined by RT-qPCR and normalized to the level of TBP mRNA. The levels of A3B mRNA are presented as relative levels compared to those in HFK. The data are the averages of three independent experiments, with the error bars representing standard deviations. (G) Expression of APOBEC mRNAs was examined by microarray analysis with HCK1T stably expressing HPV16 E6 (HCK1T-E6). The levels of APOBEC mRNAs are presented as the fold increase compared with those in HCK1T expressing a selection marker alone (HCK1T-V). (H) Expression of TEAD1/4 and p53 in HCK1T stably expressing HPV16 E6 (HCK1T-E6) or a series of E6 mutants was examined by immunoblotting using anti-TEAD1, anti-TEAD4, and anti-p53 antibodies. Tubulin was used as the loading control. 16E6-D151, C terminus deletion mutant; 16E6-F2V and 16E6-SAT, p53 binding-deficient mutants; SAT/D151, double mutant of SAT and D151. (I) NIKS were transfected with p53 siRNA (sip53) or control siRNA (siCtrl), and 2 days after transfection, the cells were analyzed for expression of p53 and TEAD4 by immunoblotting. β-Actin was used as the loading control. (J) The levels of A3B mRNA in NIKS transfected with p53 siRNA (sip53) or control siRNA (siCtrl) were determined by RT-qPCR and normalized to the level of TBP mRNA. The data are the averages of three independent experiments, with the error bars representing standard deviations.

Similarly, we observed increased levels of TEAD4 protein and A3B mRNA in primary human foreskin keratinocytes (HFK) transduced with an E6 (HFK-E6) versus an empty (HFK-V) retroviral vector (Fig. 4C and D). No change was observed for TEAD1 levels in HFK-E6 compared to HFK-V. Interestingly, coexpression of E7 with E6 in HFK (HFK-E6/E7) further augmented TEAD4 protein and A3B mRNA levels (Fig. 4C and D), suggesting that the two oncoproteins cooperatively upregulate A3B by increasing TEAD4 levels. Moreover, HFK harboring an episomal HPV16 (HFK-16) or HPV18 (HFK-18) genome exhibited greatly increased levels of both TEAD1 and TEAD4 compared to parental HFK (Fig. 4E), accompanied by an increase in A3B mRNA levels (Fig. 4F). These data suggest that the upregulation of TEAD1, TEAD4, and A3B reflects natural HPV infection and may be shared among high-risk HPV infections.

We further examined the upregulation of TEAD1 and TEAD4 by E6 using a series of E6 mutants expressed in human cervical keratinocytes immortalized with telomerase reverse transcriptase (HCK1T) (27). We performed microarray analyses to evaluate the expression of several APOBEC genes in HCK1T cells stably transduced with an empty vector (HCK1T-V) or a retroviral vector encoding HPV16 E6 (HCK1T-E6). A3B showed the largest increase in expression in HCK1T-E6 compared to HCK1T-V (Fig. 4G). HCK1T were then similarly transduced with a series of E6 mutants: F2V and SAT (p53 binding- and degradation-deficient mutants), D151 (p53 degradation proficient but lacking the C-terminal PDZ-binding motif), and SAT/D151 (p53 degradation deficient and lacking the C-terminal PDZ-binding motif). TEAD1 levels increased somewhat in HCK1T-E6, -D151, -F2V, -SAT, and -SAT/D151 relative to that in HCK1T-V (Fig. 4H). In contrast, TEAD4 levels were specifically upregulated in HCK1T-E6 and -D151 relative to that in HCK1T-V; this effect was partially abrogated in HCK1T-E6-F2V, -SAT, and -SAT/D151 (Fig. 4H). p53 levels were downregulated in HCK1T-E6 and -D151 compared to that in HCK1T-V, and this effect was abrogated in HCK1T-E6-F2V, -SAT, and -SAT/D151, as expected (Fig. 4H). Together, these data suggest that E6-mediated upregulation of TEAD4 requires degradation of p53, but not interactions between E6- and PDZ-containing proteins. Nevertheless, small interfering RNA (siRNA) knockdown of p53 in NIKS did not affect TEAD4 levels (Fig. 4I) and only slightly increased A3B mRNA levels (Fig. 4J). Although not conclusively proven, our findings suggest that degradation of p53 is necessary but not sufficient to upregulate TEAD4 and A3B.

TEADs are required for E6-mediated upregulation of A3B.

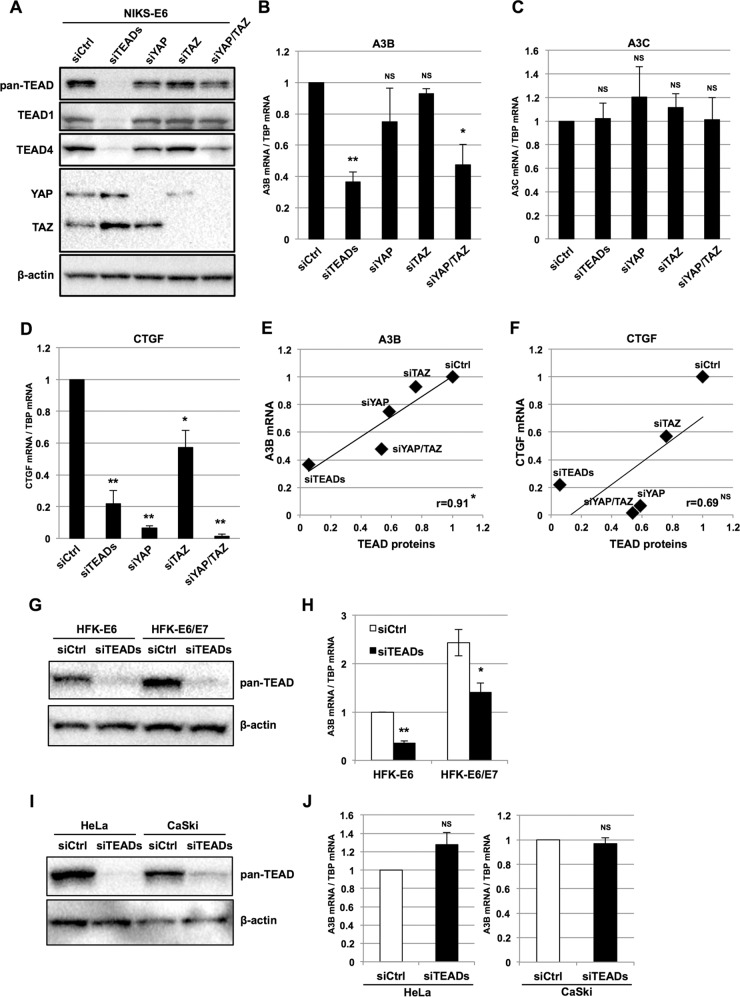

Next, we performed knockdown experiments to examine if TEADs are required for E6-mediated upregulation of A3B. To knock down the expression of all TEADs, we transfected NIKS-E6 with a mixture of siRNAs targeting TEAD1/2/3/4 (siTEADs). NIKS-E6-siTEADs displayed a nearly complete depletion of TEADs compared to NIKS-E6-siCtrl (control), as revealed by Western blotting with anti-pan-TEAD antibody (Fig. 5A). Consistent with the pan-TEAD blotting result, both TEAD1 and TEAD4 were efficiently depleted in NIKS-E6-siTEADs compared to NIKS-E6-siCtrl (Fig. 5A). Concomitantly, the depletion of TEADs from NIKS-E6 cells caused a significant reduction in the levels of A3B mRNA (Fig. 5B), but not of another APOBEC3 member expressed in NIKS-E6, APOBEC3C (A3C) mRNA (Fig. 5C). The mRNA level of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), a well-defined target gene of YAP/TAZ/TEADs involved in cell adhesion, proliferation, and migration (20), was decreased about 5-fold in NIKS-E6-siTEADs compared to NIKS-E6-siCtrl (Fig. 5D), verifying that TEADs-mediated transcription is inhibited upon knockdown of TEADs. Thus, TEADs are required for A3B upregulation in NIKS-E6.

FIG 5.

Effects of TEADs or YAP/TAZ knockdown on A3B expression in human keratinocytes expressing E6. (A) NIKS-E6 were transfected with a mixture of TEAD1/2/3/4 (TEADs) siRNAs, YAP and/or TAZ siRNAs, or control (Ctrl) siRNA, and 2 days after transfection, the cells were analyzed for expression of TEADs and YAP/TAZ by immunoblotting using anti-pan-TEAD, anti-TEAD1, anti-TEAD4, and anti-YAP/TAZ antibodies. β-Actin was used as the loading control. (B to D) The levels of A3B (B), A3C (C), and CTGF (D) mRNAs in NIKS-E6 transfected with the siRNAs described for panel A were determined by RT-qPCR with normalization to the level of TBP mRNA. The data are the averages of three independent experiments, with the error bars representing standard deviations. NS, P > 0.05; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005 (Student's t test). (E and F) The levels of TEAD proteins detected by anti-pan-TEAD antibody in panel A were quantified with Image Lab software (Bio-Rad) and normalized against those of β-actin. The normalized TEAD levels and A3B or CTGF mRNA levels in panels B and D are plotted on the x axis and y axis, respectively. The correlation coefficients (r) between TEAD proteins and A3B or CTGF mRNA levels are indicated. NS, P > 0.05; *, P < 0.05 (Pearson's test for correlation). (G) HFK-E6 or HFK-E6/E7 were transfected with a mixture of TEAD1/2/3/4 siRNAs and analyzed for expression of TEADs as described for panel A. (H) The levels of A3B mRNAs in HFK-E6 or HFK-E6/E7 transfected with a mixture of TEAD1/2/3/4 siRNAs were determined by RT-qPCR with normalization to the level of TBP mRNA. The levels of A3B mRNA are presented as relative levels compared to that in HFK-E6 transfected with control siRNA. The data are the averages of three independent experiments, with the error bars representing standard deviations. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005 (Student's t test). (I) HeLa or CaSki cells were transfected with a mixture of TEAD1/2/3/4 siRNAs and analyzed for expression of TEADs as described for panel A. (J) The levels of A3B mRNAs in HeLa or CaSki cells transfected with a mixture of TEAD1/2/3/4 siRNAs were determined by RT-qPCR with normalization to the level of TBP mRNA. The levels of A3B mRNA are presented as relative levels compared to that in cells transfected with control siRNA. The data are the averages of three independent experiments, with the error bars representing standard deviations. NS, P > 0.05 (Student's t test).

To determine if YAP and/or TAZ is required for upregulation of A3B, we performed similar knockdown experiments. We achieved efficient depletion of YAP and TAZ with siRNAs targeting YAP and/or TAZ (Fig. 5A). In contrast to NIKS-E6-siTEADs, the levels of A3B mRNA were not significantly different in NIKS-E6-siYAP and -siTAZ compared to NIKS-E6-siCtrl (Fig. 5B). In contrast, NIKS-E6-siYAP and -siTAZ displayed significantly decreased CTGF mRNA levels compared to NIKS-E6-siCtrl (Fig. 5D). Simultaneous knockdown of YAP and TAZ in NIKS-E6-siYAP/TAZ, however, caused a significant reduction in A3B mRNA levels (Fig. 5B). As with TEADs knockdown, YAP and/or TAZ knockdown in NIKS-E6 did not affect A3C expression (Fig. 5C).

Notably, knockdown of YAP and/or TAZ in NIKS-E6 decreased the total levels of TEADs by various degrees (Fig. 5A). We thus sought to evaluate the relationship between the levels of A3B mRNA and total TEADs protein in the various NIKS-E6 knockdown lines. We quantified the upper and lower bands from the pan-TEAD blot, which represent TEAD1/4 and TEAD3, respectively. We found that the A3B mRNA levels positively correlated with TEAD protein levels (Fig. 5E) (P = 0.03; Pearson's test for correlation). These data suggest that the reduced A3B mRNA levels in NIKS-E6-siYAP/TAZ compared to NIKS-E6-siCtrl are mainly caused by decreased levels of TEADs and do not directly depend on YAP and/or TAZ coactivator functions. In contrast, YAP or YAP/TAZ knockdown caused a more drastic reduction in CTGF mRNA levels than in A3B mRNA levels, and no significant correlation was observed between the levels of CTGF mRNA and TEADs protein in the NIKS-E6 knockdown lines (Fig. 5F) (P = 0.2; Pearson's test for correlation). This suggests that YAP/TAZ play important and direct roles as coactivators in CTGF transactivation.

The importance of TEAD levels in the upregulation of A3B was further verified using HFK-E6 and HFK-E6/E7. As observed with NIKS-E6, siRNA knockdown of TEADs in HFK-E6 and HFK-E6/E7 (Fig. 5G) caused a significant reduction in A3B mRNA levels compared to control siRNA knockdown cells (Fig. 5H). Thus, TEADs are generally responsible for E6-mediated upregulation of A3B in human keratinocytes.

We also examined the effects of TEAD knockdown on A3B expression using cervical cancer cell lines, HeLa (HPV18 positive) and CaSki (HPV16 positive), and found that depletion of TEADs did not affect A3B mRNA levels in these cells (Fig. 5I and J), suggesting that cervical cancer cells no longer depend on TEADs for A3B upregulation.

Ectopic TEAD4 expression is sufficient to increase A3B expression.

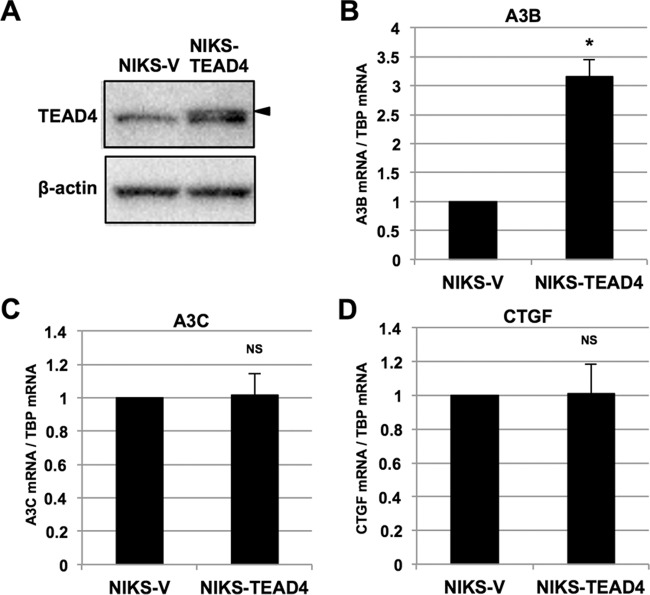

To complement the results obtained with TEAD knockdown experiments, we examined the effect of ectopic expression of TEAD4 on A3B levels. NIKS were infected with a retroviral vector encoding TEAD4 (NIKS-TEAD4), and drug-resistant cells were pooled after puromycin selection and used for subsequent analyses. As expected, NIKS-TEAD4 produced exogenous TEAD4 (Fig. 6A, top band [arrowhead]), in addition to endogenous TEAD4. Further, NIKS-TEAD4 expressed approximately 3-fold-higher levels of A3B mRNA than NIKS-V by RT-qPCR (Fig. 6B). In contrast, A3C and CTGF mRNA levels were not increased in NIKS-TEAD4 compared to NIKS-V (Fig. 6C and D). Thus, increased TEAD4 levels are sufficient to induce A3B expression.

FIG 6.

Effects of exogenous TEAD4 expression on A3B expression. (A) NIKS exogenously expressing TEAD4 (NIKS-TEAD4) or the selection marker alone (NIKS-V) were analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-TEAD4 antibody. The arrowhead indicates exogenous TEAD4. Endogenous TEAD4 is translated from a non-ATG codon, yielding a smaller protein band than exogenous TEAD4. β-Actin was used as the loading control. (B to D) The levels of A3B (B), A3C (C), and CTGF (D) mRNAs in NIKS-V or NIKS-TEAD4 were determined by RT-qPCR with normalization to the level of TBP mRNA. The data are the averages of three independent experiments, with the error bars representing standard deviations. NS, P > 0.05; *, P < 0.05 (Student's t test).

Association of TEAD4 with the A3B promoter in vivo.

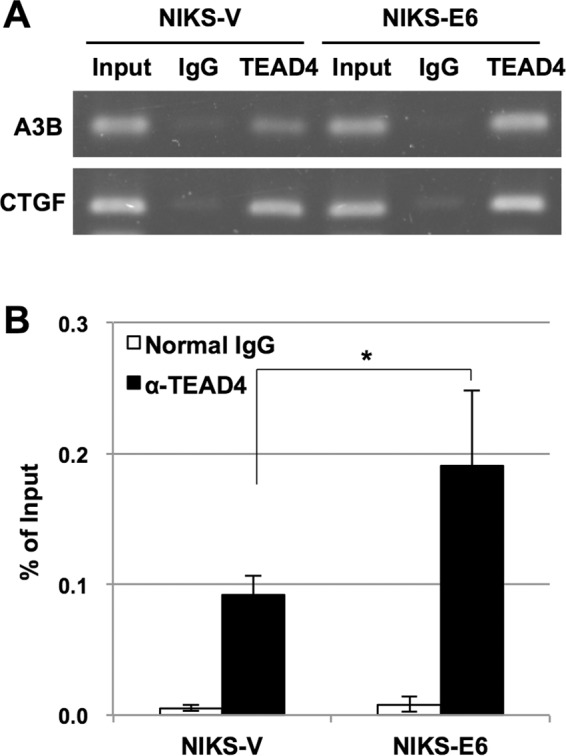

Finally, we examined the binding of TEAD4 to the A3B promoter in cells by conducting chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays. As shown in Fig. 7A, an anti-TEAD4 antibody precipitated the A3B promoter from both NIKS-V and NIKS-E6, indicating that endogenous TEAD4 binds to the A3B promoter in these cells. We also detected TEAD4 occupancy at the CTGF promoter in these cells, verifying experimental integrity. Importantly, the levels of TEAD4 binding to the A3B promoter were about 2-fold higher in NIKS-E6 than in NIKS-V (Fig. 7B), suggesting that increased binding of TEAD4 to the A3B promoter in NIKS-E6 may be the mechanism underlying E6-mediated upregulation of A3B.

FIG 7.

Association of endogenous TEAD4 with the A3B promoter in vivo. Cross-linked chromatin prepared from NIKS-V or NIKS-E6 was immunoprecipitated with anti-TEAD4 antibody or normal mouse IgG, and the recovered DNA was subjected to PCR with specific primers for the A3B and CTGF promoters, followed by agarose gel analysis (A) or real-time PCR to determine the amounts of the A3B promoter DNA containing the −149/−51 region (B). The levels of TEAD4 binding to the A3B promoter are shown as percentages of the input DNA. The data are the averages of at least three independent experiments, with the error bars representing standard deviations. *, P < 0.05 (Student's t test).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have demonstrated that the A3B promoter has three functional TEAD-binding sites that are required for strong activation of the A3B promoter. We have also revealed that E6-mediated upregulation of A3B is primarily caused by increased levels of TEAD1/4. A3B and TEAD1/4 are reported to be upregulated in various types of human cancer, and each has been proposed to play important roles in carcinogenesis (5–9, 28–32). This study thus establishes a novel transcriptional link between these oncogenic factors.

Our initial bioinformatics search identified a canonical MCAT motif in the A3B promoter, which binds to TEADs in in vitro DNA-binding assays and was partially required for A3B promoter activation by TEAD4 in reporter assays (Fig. 2). Further pulldown and reporter analyses revealed two additional binding sites for TEADs within the A3B promoter (MCAT-like 1 and 2), located just upstream of the MCAT motif. Intriguingly, mutations within the MCAT motif and within at least one MCAT-like site almost completely abolished A3B promoter activation by TEAD4. Thus, in addition to the canonical MCAT motif, the MCAT-like sequences contribute to A3B promoter activation by TEADs. Recent studies have demonstrated that regulatory and promoter regions of many TEAD target genes have more than one TEAD-binding motif oriented in the same direction (33) and that TEAD1 binds to such double motifs as a dimer (34). Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that multiple TEAD-binding sites are required to achieve maximum activation of the A3B promoter by TEADs.

Overall, our results clearly demonstrate that the levels of TEADs are a critical determinant for inducing A3B expression. In contrast, CTGF expression was not further enhanced by exogenous TEAD4 expression (Fig. 6D), and expression of E6 in NIKS did not increase the CTGF mRNA levels (data not shown), suggesting different requirements for coactivators between the two promoters. We speculate that YAP/TAZ are the limiting factors for TEAD-mediated CTGF transactivation, while coactivators other than YAP/TAZ, such as Vgll (35, 36) and SRC3 (37, 38), might be involved in A3B transactivation by TEAD. In support of this scenario, YAP and constitutively active YAP (5SA) only modestly activated the A3B promoter (Fig. 3A), and YAP/TAZ knockdown reduced the mRNA level of A3B less efficiently than that of CTGF (Fig. 5B and D). In addition, our preliminary analyses showed that siRNA knockdown of SRC3 reduced the A3B mRNA level without decreasing TEAD levels in NIKS-E6 (data not shown), suggesting involvement of SRC in A3B upregulation. However, further investigation will be required to clarify the coactivator(s) responsible for TEAD-mediated induction of A3B.

Unlike NIKS and HFK retrovirally transduced with E6, dependency on TEADs for A3B expression was not observed in HeLa and CaSki cells (Fig. 5I and J), which continuously express E6 and E7. We speculate that TEAD-mediated A3B upregulation occurs in the early stages of HPV-induced cervical carcinogenesis, whereas the A3B expression in advanced cancer cells is switched to being dependent on the NF-κB pathway, as recently reported for breast cancer cells (15), although this hypothesis awaits further experimental verification.

How does E6 induce TEAD expression? A genome-wide ChIP sequencing study revealed that TEAD4 binds to its own promoter and that YAP is required for TEAD4 expression (38), which suggests a positive-feedback mechanism for TEAD4 expression through TEAD4/YAP. In that study, TEAD4 binding to the TEAD1 promoter was also demonstrated (38), suggesting that TEAD1 expression can be upregulated by TEAD4/YAP. In agreement with these findings, we found that overexpression of YAP was associated with increased TEAD1/4 levels in NIKS-E6 (Fig. 4A) and that YAP knockdown in NIKS-E6 reduced TEAD1/4 expression (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, YAP overexpression led to an increase in TEAD4 levels in HEK293 cells that was dependent on its ability to interact with TEADs (Fig. 3B). Given that YAP expression is increased in high-grade precancerous lesions and cervical squamous cell carcinoma (25) and that E6 was reported to upregulate YAP in cervical cancer cells (26), these results imply that E6 increases TEAD1/4 levels through upregulation of YAP.

We also found that E6-mediated degradation of p53 seems to be required for upregulation of TEAD4. Although the mechanism is unclear, antiapoptotic and proliferative effects mediated by E6 through p53 inactivation may eventually result in YAP stabilization (26). In contrast, p53 knockdown alone was not sufficient to upregulate TEAD4 and A3B (Fig. 4I and J), which may suggest that other biological effects exerted by E6 additionally contribute to A3B upregulation or that the E6 mutants incapable of inducing TEAD4 have defects unrelated to p53 inactivation. Alternatively, this discrepancy may reflect the differences between the long-term effects of p53 degradation by retrovirally transduced E6 and the short-term effects of p53 depletion by siRNA transfection.

Since the Hippo pathway, which negatively regulates transcriptional programs mediated by TEADs, is frequently inactivated in many types of human cancer (20, 21), the TEAD-A3B axis may have more general implications for carcinogenesis. Of particular interest, TEAD4 is overexpressed in several human cancers, such as gastric, breast, and colorectal cancers, and the expression levels of TEAD4 correlate with poor survival of cancer patients (20, 29–31). Whether such TEAD4 upregulation leads to A3B upregulation in these cancers, thereby contributing to cancer evolution and malignancies, warrants further investigation using cell culture models and clinical specimens. Lastly, pharmacological interventions that inhibit TEAD action may pave the way for prevention of A3B-associated cancers, including cervical and head and neck cancers caused by high-risk HPV infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

HEK293, HeLa, and CaSki cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified minimal essential medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). NIKS (American Type Culture Collection CRL-12191), HFK (Kurabo, Osaka, Japan), and HCK1T were maintained as previously described (16, 27). All experiments using keratinocytes were performed in keratinocyte-SFM (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 30 μg/ml bovine pituitary extract and 1 ng/ml human recombinant epidermal growth factor without feeder cells.

Plasmids.

The luciferase reporter plasmids containing the human A3B promoter were constructed as previously described (16). The reporter plasmids pA3B−200/+45, pA3B−100/+45, and pA3B−50/+45 include the A3B promoter regions −200/+45, −100/+45, and −50/+45, respectively. The numbering of the nucleotide positions is based on the Transcriptional Regulatory Element Database sequence (accession number 28319) (39). The MCAT motif (AGGAATG) located at −95/−89 of the A3B promoter was changed to ATTAATG (mutated nucleotides are underlined) by PCR, and the corresponding region of pA3B−200/+45 was replaced with the mutated fragment to produce pA3B−200/+45 Mm1. The MCAT-like sequences located at −137/−131 (MCAT-like 1; AAACATG) and −109/−103 (MCAT-like 2; ACCAATG) were changed to AAACACC and ACCTACC, respectively, by PCR, and the corresponding region of pA3B−200/+45 Mm1 was replaced with the mutated fragments to produce pA3B−200/+45 Mm2.1, pA3B−200/+45 Mm2.2, and pA3B−200/+45 Mm3. To produce the expression plasmid for TEAD1 (pCMV-TEAD1), the TEAD1 cDNA was amplified from cDNA prepared from HFK using PCR with the primers forward, 5′-GCG GCC ATG GAG CCC AGC TGG AG-3′, and reverse, 5′-GCG GCC GCT CAG TCC TTT ACA AGC CTG T-3′, and cloned into pCMV, which had been created by removing the β-galactosidase gene from pCMV-β (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). The expression plasmids for TEAD2 (pCMV-FLAG-TEAD2) and TEAD3 (pCMV-FLAG-TEAD3) were purchased from OriGene Technologies (Rockville, MD). The expression plasmids for hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged TEAD4 (pCMV-HA-TEAD4), myc-tagged YAP (pCMV-myc-YAP), myc-tagged 5SA (pCMV-myc-5SA), and myc-tagged 5SA/TEAD* (pCMV-myc-5SA/TEAD*) were described previously (40).

Luciferase reporter assays.

HEK293 cells (8 × 104 cells/well) were grown in a 24-well plate for 24 h and then transfected with 200 ng of the A3B reporter plasmids and the indicated amounts of the expression plasmids for TEADs or myc-YAP, together with 5 ng of the expression plasmid pGL4.75 (Promega, Madison, WI) for Renilla luciferase, using FuGene 6 (Promega). The firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were measured 48 h posttransfection using the Dual-Glo luciferase assay system (Promega) on an Arvo MX luminescence counter (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). The firefly luciferase activities were normalized to the Renilla luciferase activities.

Immunoblotting.

Immunoblotting was performed as previously described (16). The antibodies used in this study were as follows: anti-Myc (ab1326; Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom), anti-TEAD1 (EPR3967 [2]; Abcam), anti-TEAD2 (H-50; Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-TEAD3 (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA), anti-TEAD4 (N-G2; Santa Cruz), anti-FLAG (F7425; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), anti-pan-TEAD (D3F7L; Cell Signaling), anti-YAP (D8H1X; Cell Signaling), anti-TAZ (V386; Cell Signaling), anti-phospho-YAP (D9W2I; Cell Signaling), anti-YAP/TAZ (D24E4; Cell Signaling), anti-p53 (DO-1; Santa Cruz), anti-α-tubulin (B-5-1-2; Sigma-Aldrich), and anti-β-actin (C-4; Santa Cruz) antibodies.

DNA pulldown assay.

Biotinylated DNA probes corresponding to the −200/+45, −200/−96, −200/−142, and −141/−96 regions of the A3B promoter were prepared by PCR using pA3B−200/+45 as the template with the following primers: −200F, 5′-biotin-TTG GAG GTT CCT CTG CCA GC-3′; −141F, 5′-biotin-AGA GAA ACA TGA AGC ACC CC-3′; +45R, 5′-CTT AGA TAC GCT TGT CCC TG-3′; −96R, 5′-GCT CAG GCA TTG GTG TGG GA-3′; and −142R, 5′-GGC TCT GGC TCT GGC TCT GGT T-3′. A DNA probe with mutations in the MCAT motif (−200/+45 Mm1) was prepared by PCR using pA3B−200/+45 Mm1 as the PCR template. A DNA probe with mutations in both the MCAT and two MCAT-like sequences (−200/+45 Mm3) was prepared by PCR using pA3B−200/+45 Mm3 as the PCR template. The biotinylated DNA probes (12.5 pmol) were coupled to 200 μg of Dynabeads/M-280 streptavidin (Dynal Biotech, Oslo, Norway) at room temperature for 30 min in a coupling buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 0.5 mM EDTA, 1 M NaCl). The nuclear extract (30 μg of total protein) prepared from NIKS-E6 using a nuclear extraction kit (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) was diluted in 200 μl of a binding buffer [20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 100 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.01% NP-40, 100 μg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA), 10 μg/ml poly(dI-dC), and 1× Complete (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN)] and incubated with 200 μg of the DNA-coupled magnetic beads at 4°C for 1.5 h. For binding competition assays, unlabeled double-stranded oligonucleotides (250 pmol) were added to the binding mixtures. The beads were washed three times with the binding buffer without BSA and poly(dI-dC), and the bound proteins were eluted by boiling the beads in 20 μl of the SDS sample buffer. The recovered proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-pan-TEAD antibody.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR.

The mRNA levels of A3B, A3C, and CTGF were measured by RT-qPCR with SYBR Green dye. Total RNA was prepared from cells using the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and reverse transcribed to cDNA in a 20-μl reaction mixture using the ReverTra Ace (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan). The PCR mixture (20 μl), containing 2.5 μl of the cDNA solution, 10 μl of SYBR green real-time PCR master mix (Toyobo), and 0.4 μM each primer, was subjected to real-time PCR analysis on a LightCycler 480 (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). The amounts of A3B, A3C, and CTGF products were normalized to concurrently amplified TATA-binding protein (TBP) cDNA. The nucleotide sequences of the primers for the A3B, A3C, CTGF, and TBP genes have been described previously (5, 41).

siRNA transfection.

NIKS, NIKS-E6, HFK-E6, HFK-E6/E7, and HeLa and CaSki cells (5 × 104 cells/well) were grown in a 24-well plate for 24 h and then transfected with 5 pmol of siRNA using the Lipofectamine RNAiMax transfection reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). When cells were transfected with a mixture of different siRNAs, 5 pmol of each siRNA was used. Two days after transfection, the cells were harvested and analyzed by immunoblotting or RT-qPCR as described above. The following siRNAs were purchased from GE Healthcare (Lafayette, CO): On-Targetplus nontargeting pool (D-001810-10) (control siRNA), On-Targetplus human TEAD1 siRNA Smartpool (L-012603-00), On-Targetplus human TEAD2 siRNA Smartpool (L-012611-01), On-Targetplus human TEAD3 siRNA Smartpool (L-012604-00), On-Targetplus human TEAD4 siRNA Smartpool (L-019570-00), On-Targetplus human YAP1 siRNA Smartpool (L-012200-00), and On-Targetplus human WWTR1 siRNA Smartpool (L-016083-00). The siRNA against p53 was purchased from Santa Cruz (sc-29435).

Stable transduction of keratinocytes.

NIKS or HFK expressing HPV16 E6 (NIKS-E6 or HFK-E6) or a selection marker alone (NIKS-V or HFK-V) was used in the previous study (16). HFK expressing both E6 and E7 (HFK-E6/E7) were produced by infection of HFK with a recombinant retrovirus encoding HPV16 E6/E7, as previously described (16). The E6/E7 gene was amplified by PCR with primers (forward, 5′-GAA TTC GCC ACC ATG CAC CAA AAG AGA ACT GC-3′, and reverse, 5′-GAA TTC TTA TGG TTT CTG AGA ACA GA-3′) from the HPV16 genome and cloned into a retroviral transfer plasmid, pMXs-puro (Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA). To produce NIKS exogenously expressing TEAD4, NIKS were stably infected with a recombinant retrovirus encoding TEAD4. TEAD4 cDNA was amplified by PCR with primers (forward, 5′-GAA TTC GCC ACC ATG GAG GGC ACG GCC GGC AC-3′, and reverse, 5′-GAA TTC TCA TTC TTT CAC CAG CCT GTA G-3′) from pCMV-HA-TEAD4. The culture was selected with 1 μg/ml puromycin, and the surviving cells were pooled. HCK1T were infected with a recombinant retrovirus encoding HPV16 E6 or a series of E6 mutants (D151, F2V, SAT, and SAT/D151) as described previously (27). HFK harboring the full HPV16 (HFK-16) or HPV18 (HFK-18) genome were established by cotransfection of religated HPV16 or HPV18 genome and pEGFP-C1 (Clontech) into HFK. The transfected cells were selected with 500 μg/ml G418 for 3 days, and surviving cells were pooled. The presence of episomal HPV genomes was confirmed by Southern blotting (data not shown).

Microarray analyses.

Total RNAs isolated from HCK1T retrovirally transduced with HPV16 E6 and an empty retroviral vector were subjected to CodeLink expression bioarray analysis using the Human Whole Genome 55K Array according to the manufacturer's instructions (GE Healthcare). The results are shown as ratios of the median-normalized expression values to those from the vector control line.

ChIP assay.

ChIP assays were performed using SimpleChIP Plus Enzymatic Chromatin IP kits (Cell Signaling) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, NIKS-V or NIKS-E6 were treated with paraformaldehyde to cross-link DNA with its associated proteins, and the chromatin fraction prepared from the cells was digested with micrococcal nuclease and immunoprecipitated with anti-TEAD4 antibody (N-G2; Santa Cruz) or normal mouse IgG (Santa Cruz). The DNA was recovered from the immunoprecipitates and subjected to PCR targeting the A3B promoter (−149/−51) with primers (forward, 5′-CCA GAG CCA GAG AAA CAT GA-3′, and reverse, 5′-AGT GAC CTC CCA GGG CCT TA-3′) or PCR targeting the CTGF promoter with primers as previously described (42). The PCR products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis followed by ethidium bromide staining. The precipitated A3B promoter DNA was quantified by real-time PCR using the same primers as for the above-mentioned PCR.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Tadahito Kanda for his critical reading of the manuscript and valuable comments on it.

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Cancer Research from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan and the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (grant number 16ck0106178j0102) to S.M. and for Reemerging Infectious Diseases from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan and the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (grant number 15fk0108010h0403) to I.K.

REFERENCES

- 1.de Sanjose S, Quint WG, Alemany L, Geraets DT, Klaustermeier JE, Lloveras B, Tous S, Felix A, Bravo LE, Shin HR, Vallejos CS, de Ruiz PA, Lima MA, Guimera N, Clavero O, Alejo M, Llombart-Bosch A, Cheng-Yang C, Tatti SA, Kasamatsu E, Iljazovic E, Odida M, Prado R, Seoud M, Grce M, Usubutun A, Jain A, Suarez GA, Lombardi LE, Banjo A, Menéndez C, Domingo EJ, Velasco J, Nessa A, Chichareon SC, Qiao YL, Lerma E, Garland SM, Sasagawa T, Ferrera A, Hammouda D, Mariani L, Pelayo A, Steiner I, Oliva E, Meijer CJ, Al-Jassar WF, Cruz E, Wright TC, Puras A, Llave CL, Tzardi M, Agorastos T, Garcia-Barriola V, Clavel C, Ordi J, Andújar M, Castellsagué X, Sánchez GI, Nowakowski AM, Bornstein J, Muñoz N, Bosch FX, Retrospective International Survey and HPV Time Trends Study Group. 2010. Human papillomavirus genotype attribution in invasive cervical cancer: a retrospective cross-sectional worldwide study. Lancet Oncol 11:1048–1056. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70230-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.zur Hausen H. 2002. Papillomaviruses and cancer: from basic studies to clinical application. Nat Rev Cancer 2:342–350. doi: 10.1038/nrc798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Narisawa-Saito M, Kiyono T. 2007. Basic mechanisms of high-risk human papillomavirus-induced carcinogenesis: roles of E6 and E7 proteins. Cancer Sci 98:1505–1511. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00546.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC, Aparicio SA, Behjati S, Biankin AV, Bignell GR, Bolli N, Borg A, Børresen-Dale AL, Boyault S, Burkhardt B, Butler AP, Caldas C, Davies HR, Desmedt C, Eils R, Eyfjörd JE, Foekens JA, Greaves M, Hosoda F, Hutter B, Ilicic T, Imbeaud S, Imielinski M, Jäger N, Jones DT, Jones D, Knappskog S, Kool M, Lakhani SR, López-Otín C, Martin S, Munshi NC, Nakamura H, Northcott PA, Pajic M, Papaemmanuil E, Paradiso A, Pearson JV, Puente XS, Raine K, Ramakrishna M, Richardson AL, Richter J, Rosenstiel P, Schlesner M, Schumacher TN, Span PN, Teague JW, Totoki Y, Tutt AN, Valdés-Mas R, van Buuren MM, van 't Veer L, Vincent-Salomon A, Waddell N, Yates LR, Australian Pancreatic Cancer Genome Initiative, ICGC Breast Cancer Consortium, ICGC MMML-Seq Consortium, ICGC PedBrain, Zucman-Rossi J, Futreal PA, McDermott U, Lichter P, Meyerson M, Grimmond SM, Siebert R, Campo E, Shibata T, Pfister SM, Campbell PJ, Stratton MR. 2013. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature 500:415–421. doi: 10.1038/nature12477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burns MB, Lackey L, Carpenter MA, Rathore A, Land AM, Leonard B, Refsland EW, Kotandeniya D, Tretyakova N, Nikas JB, Yee D, Temiz NA, Donohue DE, McDougle RM, Brown WL, Law EK, Harris RS. 2013. APOBEC3B is an enzymatic source of mutation in breast cancer. Nature 494:366–370. doi: 10.1038/nature11881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts SA, Lawrence MS, Klimczak LJ, Grimm SA, Fargo D, Stojanov P, Kiezun A, Kryukov GV, Carter SL, Saksena G, Harris S, Shah RR, Resnick MA, Getz G, Gordenin DA. 2013. An APOBEC cytidine deaminase mutagenesis pattern is widespread in human cancers. Nat Genet 45:970–976. doi: 10.1038/ng.2702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burns MB, Temiz NA, Harris RS. 2013. Evidence for APOBEC3B mutagenesis in multiple human cancers. Nat Genet 45:977–983. doi: 10.1038/ng.2701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberts SA, Gordenin DA. 2014. Hypermutation in human cancer genomes: footprints and mechanisms. Nat Rev Cancer 14:786–800. doi: 10.1038/nrc3816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swanton C, McGranahan N, Starrett GJ, Harris RS. 2015. APOBEC enzymes: mutagenic fuel for cancer evolution and heterogeneity. Cancer Discov 5:704–712. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Warren CJ, Xu T, Guo K, Griffin LM, Westrich JA, Lee D, Lambert PF, Santiago ML, Pyeon D. 2015. APOBEC3A functions as a restriction factor of human papillomavirus. J Virol 89:688–702. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02383-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vieira VC, Leonard B, White EA, Starrett GJ, Temiz NA, Lorenz LD, Lee D, Soares MA, Lambert PF, Howley PM, Harris RS. 2014. Human papillomavirus E6 triggers upregulation of the antiviral and cancer genomic DNA deaminase APOBEC3B. mBio 5:e02234-14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02234-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henderson S, Chakravarthy A, Su X, Boshoff C, Fenton TR. 2014. APOBEC-mediated cytosine deamination links PIK3CA helical domain mutations to human papillomavirus-driven tumor development. Cell Rep 7:1833–1841. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohba K, Ichiyama K, Yajima M, Gemma N, Nikaido M, Wu Q, Chong P, Mori S, Yamamoto R, Wong JE, Yamamoto N. 2014. In vivo and in vitro studies suggest a possible involvement of HPV infection in the early stage of breast carcinogenesis via APOBEC3B induction. PLoS One 9:e97787. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verhalen B, Starrett GJ, Harris RS, Jiang M. 2016. Functional upregulation of the DNA cytosine deaminase APOBEC3B by polyomaviruses. J Virol 90:6379–6386. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00771-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leonard B, McCann JL, Starrett GJ, Kosyakovsky L, Luengas EM, Molan AM, Burns MB, McDougle RM, Parker PJ, Brown WL, Harris RS. 2015. The PKC/NF-κB signaling pathway induces APOBEC3B expression in multiple human cancers. Cancer Res 75:4538–4547. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2171-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mori S, Takeuchi T, Ishii Y, Kukimoto I. 2015. Identification of APOBEC3B promoter elements responsible for activation by human papillomavirus type 16 E6. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 460:555–560. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.03.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacquemin P, Hwang JJ, Martial JA, Dolle P, Davidson I. 1996. A novel family of developmentally regulated mammalian transcription factors containing the TEA/ATTS DNA binding domain. J Biol Chem 271:21775–21785. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.36.21775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao B, Ye X, Yu J, Li L, Li W, Li S, Yu J, Lin JD, Wang CY, Chinnaiyan AM, Lai ZC, Guan KL. 2008. TEAD mediates YAP-dependent gene induction and growth control. Genes Dev 22:1962–1971. doi: 10.1101/gad.1664408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan SW, Lim CJ, Loo LS, Chong YF, Huang C, Hong W. 2009. TEADs mediate nuclear retention of TAZ to promote oncogenic transformation. J Biol Chem 284:14347–14358. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M901568200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou Y, Huang T, Cheng AS, Yu J, Kang W, To KF. 2016. The TEAD family and its oncogenic role in promoting tumorigenesis. Int J Mol Sci 17:E138. doi: 10.3390/ijms17010138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu FX, Zhao B, Guan KL. 2015. Hippo pathway in organ size control, tissue homeostasis, and cancer. Cell 163:811–828. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y, Dong Q, Zhang Q, Li Z, Wang E, Qiu X. 2010. Overexpression of Yes-associated protein contributes to progression and poor prognosis of non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Sci 101:1279–1285. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01511.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall CA, Wang R, Miao J, Oliva E, Shen X, Wheeler T, Hilsenbeck SG, Orsulic S, Goode S. 2010. Hippo pathway effector Yap is an ovarian cancer oncogene. Cancer Res 70:8517–8525. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muramatsu T, Imoto I, Matsui T, Kozaki K, Haruki S, Sudol M, Shimada Y, Tsuda H, Kawano T, Inazawa J. 2011. YAP is a candidate oncogene for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Carcinogenesis 32:389–398. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xiao H, Wu L, Zheng H, Li N, Wan H, Liang G, Zhao Y, Liang J. 2014. Expression of Yes-associated protein in cervical squamous epithelium lesions. Int J Gynecol Cancer 24:1575–1582. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He C, Mao D, Hua G, Lv X, Chen X, Angeletti PC, Dong J, Remmenga SW, Rodabaugh KJ, Zhou J, Lambert PF, Yang P, Davis JS, Wang C. 2015. The Hippo/YAP pathway interacts with EGFR signaling and HPV oncoproteins to regulate cervical cancer progression. EMBO Mol Med 7:1426–1449. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201404976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Narisawa-Saito M, Handa K, Yugawa T, Ohno S, Fujita M, Kiyono T. 2007. HPV16 E6-mediated stabilization of ErbB2 in neoplastic transformation of human cervical keratinocytes. Oncogene 26:2988–2996. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knight JF, Shepherd CJ, Rizzo S, Brewer D, Jhavar S, Dodson AR, Cooper CS, Eeles R, Falconer A, Kovacs G, Garrett MD, Norman AR, Shipley J, Hudson DL. 2008. TEAD1 and C-CBL are novel prostate basal cell markers that correlate with poor clinical outcome in prostate cancer. Br J Cancer 99:1849–1858. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lim B, Park JL, Kim HJ, Park YK, Kim JH, Sohn HA, Noh SM, Song KS, Kim WH, Kim YS, Kim SY. 2014. Integrative genomics analysis reveals the multilevel dysregulation and oncogenic characteristics of TEAD4 in gastric cancer. Carcinogenesis 35:1020–1027. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang C, Nie Z, Zhou Z, Zhang H, Liu R, Wu J, Qin J, Ma Y, Chen L, Li S, Chen W, Li F, Shi P, Wu Y, Shen J, Chen C. 2015. The interplay between TEAD4 and KLF5 promotes breast cancer partially through inhibiting the transcription of p27Kip1. Oncotarget 6:17685–17697. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu Y, Wang G, Yang Y, Mei Z, Liang Z, Cui A, Wu T, Liu CY, Cui L. 2016. Increased TEAD4 expression and nuclear localization in colorectal cancer promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis in a YAP-independent manner. Oncogene 35:2789–2800. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Teng K, Deng C, Xu J, Men Q, Lei T, Di D, Liu T, Li W, Liu X. 2016. Nuclear localization of TEF3-1 promotes cell cycle progression and angiogenesis in cancer. Oncotarget 7:13827–13841. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stein C, Bardet AF, Roma G, Bergling S, Clay I, Ruchti A, Agarinis C, Schmelzle T, Bouwmeester T, Schübeler D, Bauer A. 2015. YAP1 exerts its transcriptional control via TEAD-mediated activation of enhancers. PLoS Genet 11:e1005465. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang SW, Desai D, Khan S, Eberhardt NL. 2000. Cooperative binding of TEF-1 to repeated GGAATG-related consensus elements with restricted spatial separation and orientation. DNA Cell Biol 19:507–514. doi: 10.1089/10445490050128430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vaudin P, Delanoue R, Davidson I, Silber J, Zider A. 1999. TONDU (TDU), a novel human protein related to the product of vestigial (vg) gene of Drosophila melanogaster interacts with vertebrate TEF factors and substitutes for Vg function in wing formation. Development 126:4807–4816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pobbati AV, Chan SW, Lee I, Song H, Hong W. 2012. Structural and functional similarity between the Vgll1-TEAD and the YAP-TEAD complexes. Structure 20:1135–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Belandia B, Parker MG. 2000. Functional interaction between the p160 coactivator proteins and the transcriptional enhancer factor family of transcription factors. J Biol Chem 275:30801–30805. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000484200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu X, Li H, Rajurkar M, Li Q, Cotton JL, Ou J, Zhu LJ, Goel HL, Mercurio AM, Park JS, Davis RJ, Mao J. 2016. Tead and AP1 coordinate transcription and motility. Cell Rep 14:1169–1180. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.12.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang C, Xuan Z, Zhao F, Zhang MQ. 2007. TRED: a transcriptional regulatory element database, new entries and other development. Nucleic Acids Res 35:D137–D140. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shimomura T, Miyamura N, Hata S, Miura R, Hirayama J, Nishina H. 2014. The PDZ-binding motif of Yes-associated protein is required for its co-activation of TEAD-mediated CTGF transcription and oncogenic cell transforming activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 443:917–923. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.12.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mo JS, Yu FX, Gong R, Brown JH, Guan KL. 2012. Regulation of the Hippo-YAP pathway by protease-activated receptors (PARs). Genes Dev 26:2138–2143. doi: 10.1101/gad.197582.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xie Q, Chen J, Feng H, Peng S, Adams U, Bai Y, Huang L, Li J, Huang J, Meng S, Yuan Z. 2013. YAP/TEAD-mediated transcription controls cellular senescence. Cancer Res 73:3615–3624. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]