Abstract

Objective:

To determine the rate and differential contribution of heading vs unintentional head impacts (e.g., head to head, goal post) to CNS symptoms in adult amateur soccer players.

Methods:

Amateur soccer players completed baseline and serial on-line 2-week recall questionnaires (HeadCount) and reported (1) soccer practice and games, (2) heading and unintentional soccer head trauma, and (3) frequency and severity (mild to very severe) of CNS symptoms. For analysis, CNS symptoms were affirmed if one or more moderate, severe, or very severe episodes were reported in a 2-week period. Repeated measures logistic regression was used to assess if 2-week heading exposure (i.e., 4 quartiles) or unintentional head impacts (i.e., 0, 1, 2+) were associated with CNS symptoms.

Results:

A total of 222 soccer players (79% male) completed 470 HeadCount questionnaires. Mean (median) heading/2 weeks was 44 (18) for men and 27 (9.5) for women. One or more unintentional head impacts were reported by 37% of men and 43% of women. Heading-related symptoms were reported in 20% (93 out of 470) of the HeadCounts. Heading in the highest quartile was significantly associated with CNS symptoms (odds ratio [OR] 3.17, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.57–6.37) when controlling for unintentional exposure. Those with 2+ unintentional exposures were at increased risk for CNS symptoms (OR 6.09, 95% CI 3.33–11.17) as were those with a single exposure (OR 2.98, 95% CI 1.69–5.26) when controlling for heading.

Conclusions:

Intentional (i.e., heading) and unintentional head impacts are each independently associated with moderate to very severe CNS symptoms.

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) in athletes is a recognized public health concern.1–6 Soccer, the most popular sport worldwide,7 may account for the dominant share of subconcussive exposure in sports, where excess heading (more than 1,000 per year) may be a cause of subclinical brain injury, effects that were not explained by history of recognized concussion.8 Although published studies have focused on collegiate and professional players,9–14 most soccer players are amateur recreational league players.

Most studies of head injury in other sports have focused on single or repeated concussive injury episodes, now known to cause chronic brain pathology,15 especially in susceptible individuals.16–21 Recently, it was suggested that persistent CNS effects from soccer in adolescents were explained by collision-related injuries, not heading.22 However, because heading was not assessed in this study it was not possible to parse attribution to unintentional vs intentional head impacts9,23–28 or exposures that also occur during practice.20

Using data from a 2-week recall3,4 questionnaire, we examined the short-term relation of intentional (i.e., heading) and unintentional (i.e., head to head, head to goalpost, etc.) head impacts with CNS symptoms among amateur soccer players.

METHODS

The Einstein Soccer Study is a multifaceted longitudinal study of heading and its consequences in adult amateur soccer players. We used data from one substudy, where soccer players were recruited over a 9-month period between November 2013 and July 2014 and asked to complete one or more serial 2-week recall questionnaires on soccer activity, heading, and other head impacts.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

The Albert Einstein College of Medicine institutional review board approved the study. All participants gave written informed consent at time of enrollment.

Questionnaire development.

The 2-week recall questionnaire design was guided by 2 focus groups with adult amateur soccer players intended to elucidate (1) types of heading and other head impacts that occur during soccer, (2) symptoms experienced from heading, and (3) questionnaire language that would resonate with soccer players. Participants were asked to write actions they engage in while on the field and how they would describe heading and any sensations or symptoms experienced following heading, as well as unintentional impacts. Discussion covered terms that could be used as scale anchors for the least and greatest severity of heading-related sensations/symptoms.

HeadCount, a self-administered questionnaire, was designed to assess head impacts and associated symptoms. We selected a 2-week recall period, vs 1 week or 4 weeks, as short enough for soccer players to accurately recall recent activity but long enough to capture a meaningful amount of soccer activity.3,4

Two-week recall questionnaire.

HeadCount was implemented as a web-based questionnaire, beginning with a single yes/no question on soccer activity. HeadCount, completed as a web-based questionnaire, was organized into 5 modules focused on outdoor practice, outdoor games, indoor practice, indoor games, and unintentional head impacts. Identical questions are repeated for outdoor and indoor settings and include any practice sessions, number of soccer practice days, average number of headings during practice in the past 2 weeks, and CNS symptoms. Participants were asked how often (0–5+ episodes) in the past 2 weeks they experienced heading temporally associated with symptoms, defined as very low impact (no pain = 0), mild impact (slight pain = 1), moderate impact (moderate pain, some dizziness = 2), severe impact (felt dazed, stopped play, needed medical attention = 3), and very severe impact (knocked unconscious = 4).

For indoor and outdoor competition, questions were asked about the number of competitive soccer games, positions played during games, and average number of headings during games.

For all soccer activities in the last 2 weeks, participants were asked how often they experienced unintentional head impacts from specific causes (e.g., ball hitting to the back of the head, head to goal post, head to head). Finally, questions were asked about lifetime head injuries.

Any head injury not related to soccer was assessed using a lifetime head injury questionnaire.

Anthropomorphic measurements.

Standardized protocols were used to measure height, weight, neck circumference, neck length, and head circumference in each participant. Cylindrical neck volume was estimated as follows:

|

Study population and data collection.

Adult amateur soccer players were recruited by print and Internet advertisement and through soccer leagues, clubs, and colleges in New York City and surrounding areas. Interested individuals were directed to an enrollment website, which, after informed consent, collected screening information. Inclusion criteria were age 18–55 years, at least 5 years of active amateur soccer play, current active amateur soccer play, 6 months of amateur soccer play per year, and English language fluency. Exclusion criteria were schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, known neurologic disorder, pregnancy, and medical contraindication to MRI (relevant to a separate arm of the study). A research team member contacted qualifying individuals, confirmed eligibility and willingness to participate in the full longitudinal study, and invited enrollment. Refusals were defined as individuals who completed a screener form but could not be contacted afterwards, refused to participate, or withdrew from the study without completing their first study visit. Potential refusals were defined as individuals who did not consent to the screener form or who consented to the screener form but did not complete the form.

Enrollment occurred during an initial study visit. At the end of the study visit, enrolled participants were told they would receive an e-mail message asking them to complete an online HeadCount survey. Compensation for the study visit ($150) was contingent on completion of the online HeadCount within a week of their visit. Participants were similarly asked to complete HeadCount questionnaires in conjunction with subsequent study visits that occurred every 3 months.

Analysis.

Data from the HeadCount surveys were analyzed to determine the relation of CNS symptoms to heading or unintentional head impacts and the direct or effect-modifying role of neck size. Total heading, the primary independent variable, was highly skewed and defined as an ordered categorical variable of approximately equal size quartiles. Unintentional head impacts were represented as a count variable (i.e., 0, 1, 2+ events). Positive CNS symptoms were defined as occurring if one or more episodes of moderate (i.e., moderate pain or some dizziness), severe (felt dazed, stopped play, or required medical attention), or very severe symptoms (i.e., knocked unconscious) were reported.

All 2-week HeadCount questionnaires were used in the analysis to assess the relation of CNS symptoms with heading and unintentional head impacts. Repeated-measures logistic regression was used to estimate the odds ratio for the relation between heading and unintentional head impacts to CNS symptoms as well as the direct and effect-modifying effects of neck-related measures. Covariates considered in the model included sex, age, season of year (i.e., 4 quarters), intercollegiate vs club or league play, field position, alcohol use, and cigarette use. Questionnaires (n = 43) were excluded if the participant did not report heading activity or unintended head impacts during the 2-week recall period. Seven questionnaires, all completed by one respondent, were excluded as the heading and other data were unique and extreme outliers. For modeling, we used the PROC MIXED procedure in SAS/STAT 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

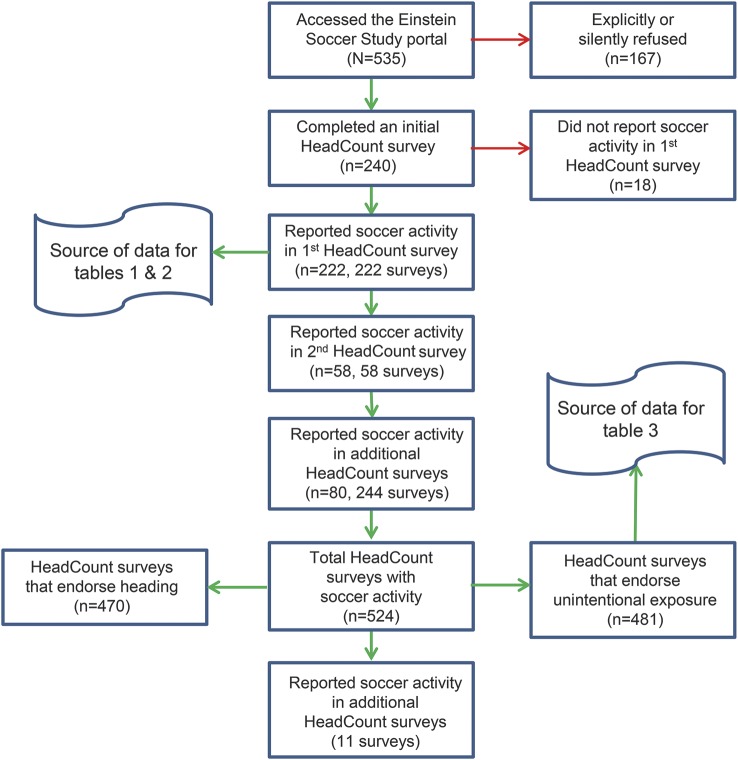

A total of 535 individuals accessed the study web portal; 22% explicitly refused and another 9.2% did not provide data and were assumed to have refused (figure). A total of 240 individuals completed an initial 2-week HeadCount questionnaire; 222 reported soccer activity. Of these, 58 completed 2 HeadCounts and 80 completed 3 or more HeadCounts for a total of 524 HeadCounts. Of these, 178 questionnaires reported heading activity and unintentional impacts, 292 reported heading but no unintentional impacts, and 11 reported unintentional impacts but no heading.

Figure. Baseline and follow-up HeadCount Questionnaires completed by 240 active amateur soccer players.

Excludes 1 soccer player's HeadCount with extreme outliers for heading data.

Heading activity.

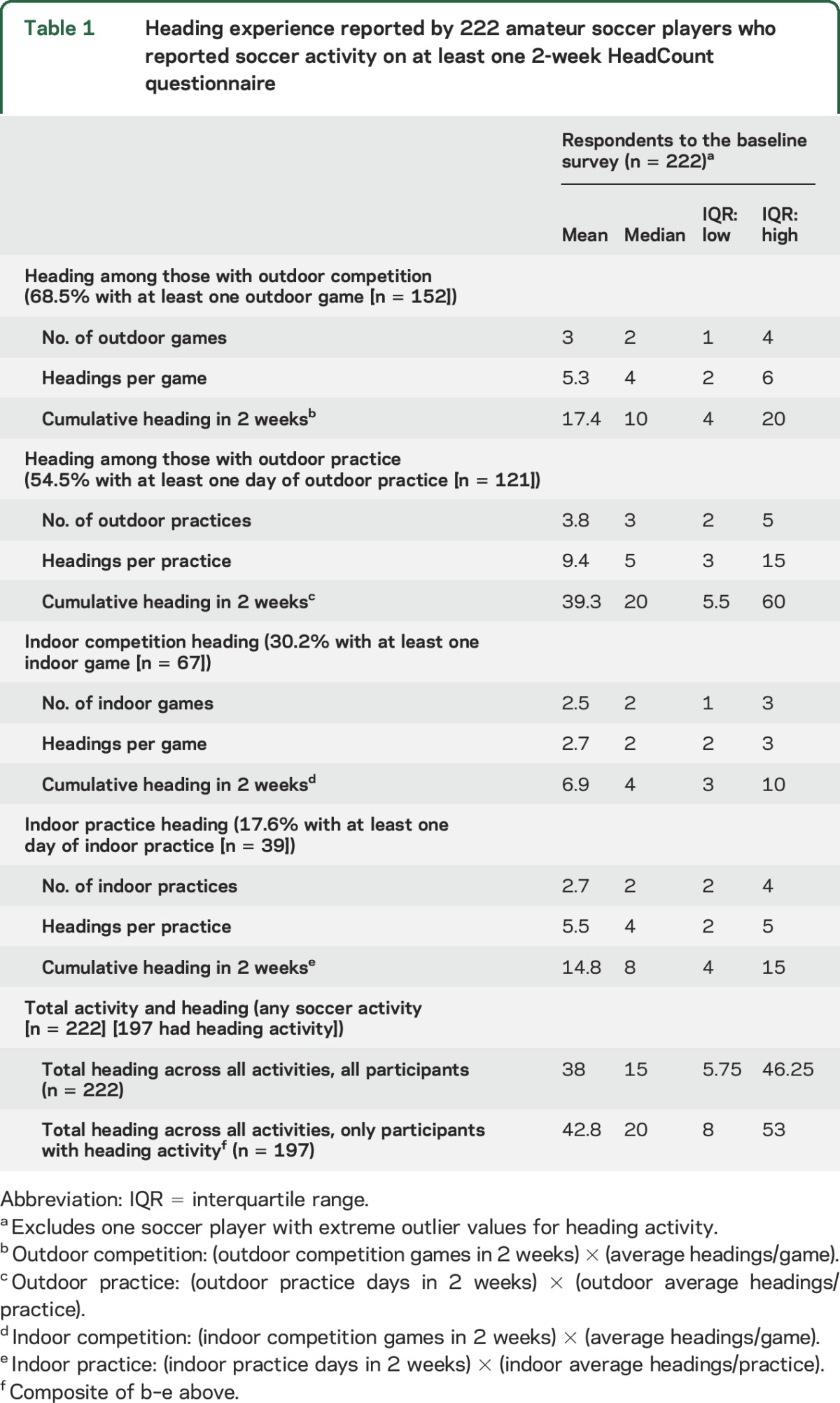

Of the 222 respondents who reported soccer activity in the baseline HeadCount, 68% were involved in outdoor competition, followed by 54% for outdoor practice, 30% for indoor competition, and 18% for indoor practice (table 1). Among those with soccer activity, the number of days of activity and the heading per day of activity was greater for practice than it was for competition (table 2). The mean (median) cumulative heading across all activities among those who reported heading (n = 197) was 42.8 (20), where 48% of all heading occurred during outdoor practice and where 80% of soccer heading occurred during outdoor activities.

Table 1.

Heading experience reported by 222 amateur soccer players who reported soccer activity on at least one 2-week HeadCount questionnaire

Table 2.

Unintentional head impacts reported by 222 amateur soccer players who reported soccer activity on at least one 2-week HeadCount questionnaire

The mean (median) cumulative heading from the initial HeadCount (table 2) was higher for the 84 respondents who only completed the baseline HeadCount (i.e., mean 38.1; 95% confidence interval [CI] 24.5–51.7) compared to the 138 respondents who completed one or more follow-up HeadCounts (i.e., mean 35.9, 95% CI 29.9–42.0), but these means were not significantly different.

Unintentional head impacts.

Exposure to unintentional head impacts was reported in 35% of the 222 baseline HeadCounts; 16% reported 2 or more episodes (table 2). “Head hit elbow or knee” and “ball hit the back of the head” were the 2 most common unintentional exposures.

Heading, unintentional impact, and symptoms by covariates.

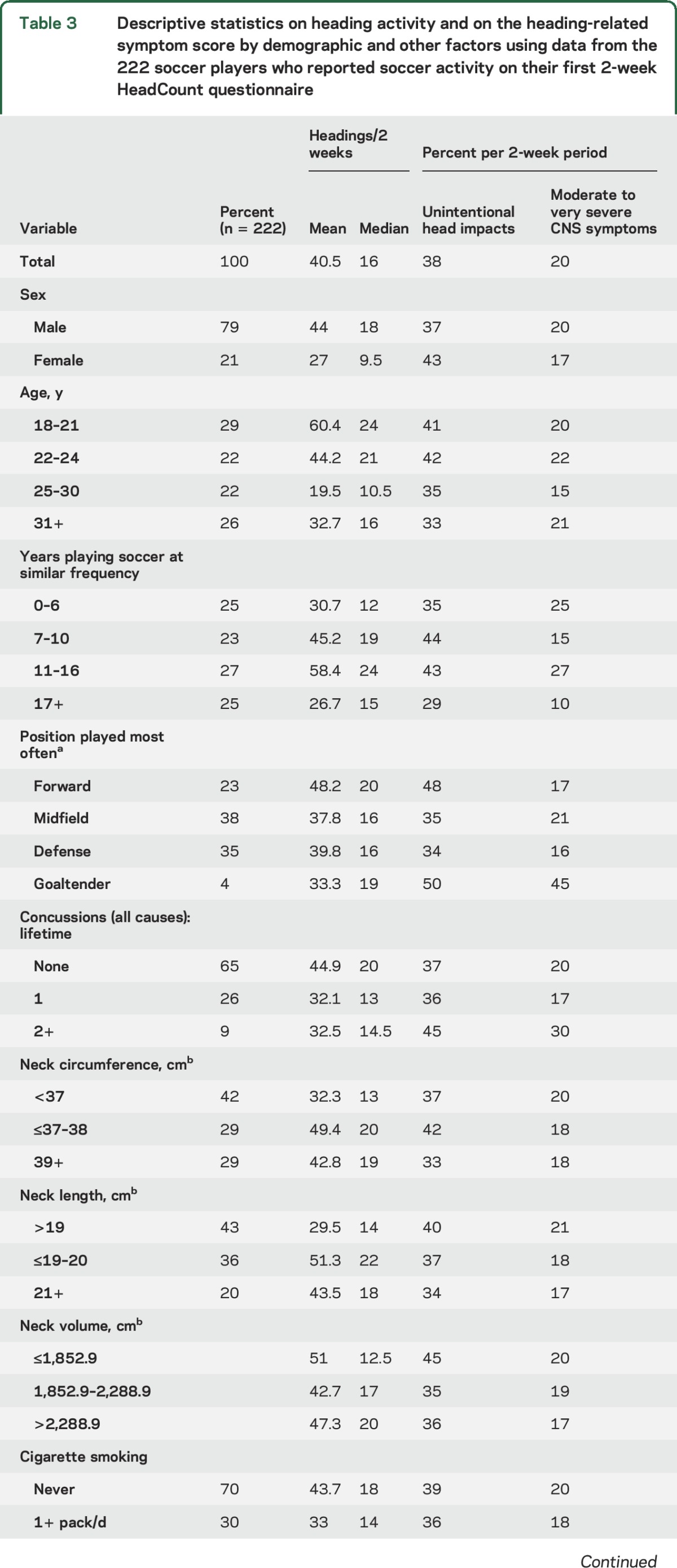

The mean (median) headings/2 weeks across all reported activities on the initial HeadCount (table 3) was 40.5 (16). Statistically significant higher levels of heading were observed for people who do not drink alcohol (p = 0.02). At least one unintentional head impact was reported in 38% of the initial 222 HeadCounts. No significant association was found for any of the covariates with risk of unintentional impacts.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics on heading activity and on the heading-related symptom score by demographic and other factors using data from the 222 soccer players who reported soccer activity on their first 2-week HeadCount questionnaire

Twenty percent of the 222 baseline HeadCounts reported moderate to very severe symptoms, with 18 reporting severe symptoms and 7 reporting very severe symptoms, of which 6 had 2 or more unintentional head impacts in a 2-week period and 1 had no unintentional impacts. Among the 7 with very severe symptoms, 4 were in the 4th quartile and 3 were in the 3rd quartile for heading in a 2-week period. Elevated proportions of HeadCounts with symptoms were observed for participants whose positions were forward (p = 0.05) and defense (p = 0.05), as well as participants with similar frequency of soccer play for 6 years or less (p = 0.002) and those who had played 11–16 years at a similar frequency (p = 0.004).

CNS symptoms and head impacts.

The relation of CNS symptoms with either heading or unintentional impacts did not vary after adjusting for sex, age, prior concussion, or other covariates described in table 3. These covariates were not retained in the logistic models. Moderate to very severe CNS symptoms were related to heading activity (table 4, model 1A) and unintentional head impacts (table 4, model 1B). When both exposure variables were included in the logistic model (table 4, model 1C), only heading activity in the highest quartile was significantly related to CNS symptoms (odds ratio [OR] 3.17, 95% CI 1.57–6.37) when compared to the lowest heading quartile. Both 1 unintentional impact (OR 2.98, 95% CI 1.69–5.26) and 2+ unintentional impacts (OR 6.09, 95% CI 3.33–11.17) from head exposures in a 2-week period were independently related to CNS symptoms.

Table 4.

Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) estimated from repeated-measures logistic regression for the relation of heading and unanticipated impacts to heading-related symptom score (i.e., moderate to very severe symptoms) based on data from 481 HeadCount questionnaires

Logistic models were completed that built on model 1C (table 4) by adding the trichotomous variables for neck length and neck circumference or separately adding neck volume. None of the neck-related variables in these models was significantly related to CNS symptoms and no meaningful interactions were observed between neck measures and head impact variables.

DISCUSSION

Relatively little is known about the short-term CNS effects from exposure to repeated head impact in soccer that may have longer-term consequences.9,29–32 Heading is associated with lower cognitive performance in high school,33 adult amateur,29 and professional31 soccer players as well as microstructural brain injury, independent of recognized concussion.5 Notably, head impacts that result in overt concussive events may not represent the full span of risks. In this study, we assessed the independent contribution of heading and unintentional exposures that occur in soccer to the risk of CNS symptoms.

Heading is very common in both practice and competition. Among those with heading activity in our study, the overall mean heading level (i.e., 42.8 headings/2 weeks) was more than twice the median (i.e., 20). This finding is consistent with our previous study, where 30% of soccer players had more than 1,000 headings per year and had a higher risk of microstructural white matter changes, typical of TBI pathology, and worse cognitive performance.8 In this study, the 10% of 2-week questionnaires with the most heading activity accounted for 42% of all heading activity.

In 114 of 517 2-week questionnaire intervals, amateur soccer players reported moderately severe and possibly concussive CNS symptoms. This is equivalent to a rate of 114 events/20 person-years or almost 6 events per year of soccer play. These events are more strongly related to unintentional head impacts, although heading was also shown to be an independent risk factor. These findings suggest that soccer players experience repeated concussive and not simply subconcussive impacts. The relation of unintentional head impacts with moderate to severe CNS symptoms is consistent with prior studies that suggest soccer-related CNS symptoms are largely explained by unintentional head exposures. The risk is substantially higher (i.e., OR of 8.36) for the 17.6% of 2-week episodes with 2 or more such exposures vs the 20.2% of the 2-week episodes with a single exposure (i.e., OR of 3.6). More specifically, if a soccer player has one unintentional head impact, there was a 47% probability (17.6%/[17.6% + 20.2%]) of having another such event in the same 2-week interval. It may thus be sensible to intervene with timely coaching when such events occur as a step to reduce the risk of a subsequent event.

This study did not address the broader question of whether heading or unintentional head impacts are related to more subtle transient changes represented by variation in performance on neuropsychological tests. It will be important to determine if these more subtle changes occur in the absence of severe CNS symptoms. Since the aggregate effect of repeated impacts may itself be important, independent of the force of individual events, characterizing the number and frequency as well as type of exposure is an important first step toward understanding the impact of heading and unintentional head impacts.

Previous studies have generally conflated the role of heading with the role of unintentional impacts that specifically result in recognized concussion.20,34–37 Prior work suggests that person-to-person collisions are the dominant cause of concussion in high school players.22 The latter conclusion, however, was based on sideline observer detection, definition, and reporting of concussion, where overt events will stand out. Our data suggest that concussive events due to heading are less likely to be detected. Importantly, this prior study did not measure heading exposure per se or test its association with concussive symptoms. Rather, the authors' specific focus was on recognized concussion, not the association of collision-related impacts with concussive symptoms. Concussive symptoms in the absence of gross impairment or unconsciousness may go unreported and undetected if players are not directly questioned.

While our report contributes the largest body of knowledge to date regarding the nature of heading and unintentional head impacts in amateur soccer, several limitations to this study must be considered. Most notably, we studied relatively young adult amateur players in the northeastern United States. We cannot generalize from the level of soccer activity among study participants to all soccer players, including adolescents and younger children, who may experience different patterns of exposure and also may only engage in soccer during specific seasons of the year. Moreover, we did not find evidence that neck-related measures were a risk factor for or an effect modifier of head impacts and CNS symptoms. A prior study suggested evidence to the contrary for female players. It is possible that neck measures are meaningful in more vulnerable groups (e.g., younger or less experienced players).

Our sample overall is diverse with respect to season of activity. Participants typically report playing soccer throughout the year. We cannot generalize to college or professional competition or to the full year of soccer experience to estimate the proportion of players who are at risk of CNS symptoms from different sources of exposure.

Data on heading, unintentional head impacts, and outcomes are self-reported and subject to recall error, raising a question as to whether the significant associations in this study are explained by reporting bias. For example, reverse causation (i.e., reporting more symptoms could motivate reporting of more heading and unintentional head impacts) could explain the study results. For heading, however, this explanation is unlikely as participants answered the symptom questions after answering the heading questions and responses could not be changed. In addition, the estimate of 2-week heading exposure was the product of a formula that included soccer practice and competition activity and separate data about heading during these activities. Participants would have to implicitly combine such information in a way that results in systematic CNS reporting errors. In contrast, questions about unintentional head impacts followed responses to questions about CNS symptoms. While reverse causation is a possible explanation, we note that our finding is consistent with prior evidence.

We also considered a more general bias hypothesis where errors in reporting (i.e., either overreporting or underreporting) CNS symptoms are assumed to be directly correlated with frequency of exposure (i.e., underreporting occurs among those who report fewer head impacts or overreporting occurs among those who report more head impacts, or both). This assumption lacks face validity when considering the likelihood of a reporting error for severe to very severe symptoms. Specifically, one would have to believe that the act of reporting heading or unintentional head impacts directly influences errors (i.e., forgetting or overreporting) in reporting CNS symptoms (i.e., a soccer player felt dazed or had to stop play or sought medical attention, or was simply knocked unconscious).

Finally, the finding of a relation from head impacts in soccer to CNS symptoms is necessary but not sufficient evidence to support a longer-term impact. If evidence of short-term effects was lacking then it would raise questions about whether head impacts in soccer have meaningful long-term consequences. On the other hand, these findings raise concerns about the likelihood of longer-term effects and thus provide a strong motivation for continued study.

Supplementary Material

GLOSSARY

- CI

confidence interval

- OR

odds ratio

- TBI

traumatic brain injury

Footnotes

Editorial, page 822

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Stewart Walter: study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content. Namhee Kim: analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content. Chloe S. Ifrah: acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data. Richard Lipton: analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content. Tamar A. Bachrach: acquisition of data. Mimi Kim: analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content. Molly Zimmerman: analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content. Michael Lipton: study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content, study supervision.

STUDY FUNDING

Study funded by NIH (R01 NS082432) and Dana Foundation.

DISCLOSURE

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gilchrist J, Thomas KE, Xu L, McGuire LC, Coronado VG. Nonfatal sports and recreation related traumatic brain injuries among children and adolescents treated in emergency departments in the United States, 2001–2009. Morb Mort Wkly Rep 2011;60:1337–1342. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Faul M, Xu L, Coronado VG. Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States: Emergency Department Visits, Hospitalizations and Deaths 2002–2006. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention NCfIPaC; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robinson MD, Clore GL. Episodic and semantic knowledge in emotional self-report: evidence for two judgment processes. J Pers Soc Psychol 2002;83:198–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kahneman D, Fredrickson BL, Schreiber CA, Redelmeier DA. When more pain is preferred to less: adding a better end. Psychol Sci 1993;4:401–405. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lipton ML, Gulko E, Zimmerman ME, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging implicates prefrontal axonal injury in executive function impairment following mild traumatic brain injury. Radiology 2009;252:816–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kraus MF, Susmaras T, Caughlin BP, Walker CJ, Sweeney JA, Little DM. White matter integrity and cognition in chronic traumatic brain injury: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Brain 2007;130:2508–2519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodrigues AC, Lasmar RP, Caramelli P. Effects of soccer heading on brain structure and function. Front Neurol 2016;7:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lipton ML, Kim N, Zimmerman ME, et al. Soccer heading is associated with white matter microstructural and cognitive abnormalities. Radiology 2013;268:850–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matser JT, Kessels AG, Jordan BD, Lezak MD, Troost J. Chronic traumatic brain injury in professional soccer players. Neurology 1998;51:791–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rutherford A, Stephens R, Potter D, Fernie G. Neuropsychological impairment as a consequence of football (soccer) play and football heading: preliminary analyses and report on university footballers. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2005;27:299–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Straume-Naesheim TM, Andersen TE, Dvorak J, Bahr R. Effects of heading exposure and previous concussions on neuropsychological performance among Norwegian elite footballers. Br J Sports Med 2005;39(suppl 1):i70–i77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mangus BC, Wallmann HW, Ledford M. Analysis of postural stability in collegiate soccer players before and after an acute bout of heading multiple soccer balls. Sports Biomech 2004;3:209–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rutherford A, Stephens R, Potter D. The neuropsychology of heading and head trauma in Association Football (soccer): a review. Neuropsychol Rev 2003;13:153–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jordan SE, Green GA, Galanty HL, Mandelbaum BR, Jabour BA. Acute and chronic brain injury in United States National Team soccer players. Am J Sports Med 1996;24:205–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stern RA, Riley DO, Daneshvar DH, Nowinski CJ, Cantu RC, McKee AC. Long-term consequences of repetitive brain trauma: chronic traumatic encephalopathy. PM R 2011;3:S460–S467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ariza M, Pueyo R, Matarin MM, et al. Influence of APOE polymorphism on cognitive and behavioural outcome in moderate and severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2006;77:1191–1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teasdale GM, Nicoll JA, Murray G, Fiddes M. Association of apolipoprotein E polymorphism with outcome after head injury. Lancet 1997;350:1069–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Millar K, Nicoll JA, Thornhill S, Murray GD, Teasdale GM. Long term neuropsychological outcome after head injury: relation to APOE genotype. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003;74:1047–1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKee AC, Cantu RC, Nowinski CJ, et al. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in athletes: progressive tauopathy after repetitive head injury. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2009;68:709–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spiotta AM, Bartsch AJ, Benzel EC. Heading in soccer: dangerous play? Neurosurgery 2012;70:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldstein LE, Fisher AM, Tagge CA, et al. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in blast-exposed military veterans and a blast neurotrauma mouse model. Sci Transl Med 2012;4:134ra60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Comstock RD, Currie DW, Pierpoint LA, Grubenhoff JA, Fields SK. An evidence-based discussion of heading the ball and concussions in high school soccer. JAMA Pediatr 2015;169:830–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McAllister TW, Flashman LA, Maerlender A, et al. Cognitive effects of one season of head impacts in a cohort of collegiate contact sport athletes. Neurology 2012;78:1777–1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guskiewicz KM, Mihalik JP, Shankar V, et al. Measurement of head impacts in collegiate football players: relationship between head impact biomechanics and acute clinical outcome after concussion. Neurosurgery 2007;61:1244–1252; discussion 52–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spiotta AM, Shin JH, Bartsch AJ, Benzel EC. Subconcussive impact in sports: a new era of awareness. World Neurosurg 2011;75:175–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gysland SM, Mihalik JP, Register-Mihalik JK, Trulock SC, Shields EW, Guskiewicz KM. The relationship between subconcussive impacts and concussion history on clinical measures of neurologic function in collegiate football players. Ann Biomed Eng 2012;40:14–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dart J, Bandini P. The hardest recorded shot in football—ever. The Guardian Epub 2007 Feb 14.

- 28.Kirkendall DT, Jordan SE, Garrett WE. Heading and head injuries in soccer. Sports Med 2001;31:369–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matser EJT, Kessels AG, Lezak MD, Jordan BD, Troost J. Neuropsychological impairment in amateur soccer players. JAMA 1999;282:971–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Downs DS, Abwender D. Neuropsychological impairment in soccer athletes. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2002;42:103–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matser JT, Kessels AG, Lezak MD, Troost J. A dose-response relation of headers and concussions with cognitive impairment in professional soccer players. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2001;23:770–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Witol AD, Webbe FM. Soccer heading frequency predicts neuropsychological deficits. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 2003;18:397–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Powell JW, Barber-Foss KD. Traumatic brain injury in high school athletes. JAMA 1999;282:958–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kontos AP, Dolese A, Elbin RJ, Covassin T, Warren BL. Relationship of soccer heading to computerized neurocognitive performance and symptoms among female and male youth soccer players. Brain Inj 2011;25:1234–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koutures CG, Gregory AJ. Injuries in youth soccer. Pediatrics 2010;125:410–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCrory PR. Brain injury and heading in soccer. BMJ 2003;327:351–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kirkendall DT, Garrett WE Jr. Heading in soccer: integral skill or grounds for cognitive dysfunction? J Athl Train 2001;36:328–333. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Niogi SN, Mukherjee P. Diffusion tensor imaging of mild traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2010;25:241–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.