Abstract

Background

The addition of specialty palliative care to standard oncology care improves outcomes for patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers, but many lack access to specialty care services. Primary palliative care—meaning basic palliative care services provided by clinicians who are not palliative care specialists—is an alternative approach that has not been rigorously evaluated.

Methods

A cluster randomized, controlled trial of the CONNECT (Care management by Oncology Nurses to address supportive care needs) intervention, an oncology nurse-led care management approach to providing primary palliative care for patients with advanced cancer and their family caregivers, is currently underway at 16 oncology practices in Western Pennsylvania. Existing oncology nurses are trained to provide symptom management and emotional support, engage patients and families in advance care planning, and coordinate appropriate care using evidence-based care management strategies. The trial will assess the impact of CONNECT versus standard oncology care on patient quality of life (primary outcome), symptom burden, and mood; caregiver burden and mood; and healthcare resource use.

Discussion

This trial addresses the need for more accessible models of palliative care by evaluating an intervention led by oncology nurses that can be widely disseminated in community oncology settings. The design confronts potential biases in palliative care research by randomizing at the practice level to avoid contamination, enrolling patients prior to informing them of group allocation, and conducting blinded outcome assessments. By collecting patient, caregiver, and healthcare utilization outcomes, the trial will enable understanding of the full range of a primary palliative care intervention's impact.

Keywords: primary palliative care, cluster randomization, quality of life, oncology nursing, behavioral intervention, caregiver

Introduction

More than 600,000 patients who die annually with advanced cancer experience steep declines in quality of life at the end of life [1]. Multiple factors contribute to these declines, including unrelieved physical symptoms [2], psychological distress [3, 4], caregiver burden [5], and use of aggressive, non-beneficial end-of-life treatments [6, 7]. Palliative care is a multidisciplinary specialty that focuses on improving quality of life for seriously ill patients and their families. Addition of specialty palliative care to standard oncology care has been shown to improve quality of life for patients with advanced cancer [8-10], in addition to improving caregiver outcomes [11, 12] and decreasing use of aggressive end-of-life treatments [9, 13]. Palliative care is now recommended by the American Society of Clinical Oncology for all seriously ill cancer patients at diagnosis [14].

Although specialty palliative care may benefit patients with advanced cancer [9, 10], it is not feasible to provide specialty palliative care to all patients with advanced cancer. Availability and integration of outpatient specialty palliative care at U.S. cancer centers remains suboptimal [15], and significant workforce shortages limit opportunities for expansion of services [16]. For example, in a 2010 survey of U.S. cancer centers, inpatient palliative care consult services were far more common than outpatient palliative care clinics, and only 22% of non-NCI designated cancer centers had an outpatient palliative care clinic. As of March 2016, board-certified oncologists outnumber board-certified hospice and palliative medicine physicians by more than three to one [17]. The majority of patients with cancer are treated at community cancer centers where outpatient specialty palliative care services remain rare.

Ensuring that oncology clinicians have the skills to attend to palliative care domains is another way to improve care for patients with advanced cancer. Primary palliative care refers to basic palliative care provided by clinicians who care for seriously ill patients but are not palliative care specialists. Primary palliative care is important because the needs of patients with serious illnesses are not being met with the current cancer care delivery system, under which many clinicians lack these basic skills [18]. Strengthening primary palliative care skills—including basic symptom management, basic psychosocial support, and discussions about prognosis and goals of care—among all clinicians who see patients with serious illness may improve access to high quality serious illness care while allowing palliative care specialists to focus on more complex or difficult cases [18, 19]. The impact of primary palliative care has not been rigorously studied.

In prior work, our team developed a primary palliative care intervention called CONNECT (Care management by Oncology Nurses to address supportive care needs) [20]. The CONNECT intervention is led by oncology clinic nurses who receive specialized training and administrative support to provide symptom management and emotional support, engage patients and families in advance care planning, and coordinate appropriate care using evidence-based care management strategies. We designed CONNECT to be an approach that can be widely adopted in oncology practices. In a single-site, single-arm pilot trial, the CONNECT intervention was feasible, acceptable, and perceived as effective by patients, caregivers and oncologists [20]. We therefore designed a cluster randomized trial to test the impact of CONNECT on patient, caregiver, and healthcare utilization outcomes, currently funded by the National Cancer Institute. Here we describe the protocol and key design considerations for this trial.

Methods

A. Overview of Study

This study is a cluster randomized, controlled trial comparing the CONNECT intervention to usual care among patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers. The trial tests the effect of the CONNECT intervention on patient quality of life (primary outcome), symptom burden, and mood; caregiver burden and mood; and healthcare resource use. The research protocol was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board (PRO15120154), and the trial is registered as NCT02712229 on clinicaltrials.gov.

B. Setting / Participants

Setting

The study is conducted at 16 oncology practices within the UPMC Cancer Center network in Western Pennsylvania. Annually, this network serves more than 30,000 patients, with approximately 8% from racial/ethnic minorities. We exclude oncology practices that have adjacent specialty palliative care practices because our goal is to evaluate a primary palliative care intervention for patients who lack easy access to specialty palliative care. We also exclude the practice where our pilot study was conducted. Study sites are an average distance of 38 miles (range 1.5 to 98 miles) from an outpatient palliative care clinic.

Participants

Patient participants are adults with metastatic solid tumors receiving ongoing care at a participating clinic for whom the oncologist “would not be surprised” if the patient died in the next year [21]. The “surprise” question allows us to easily identify cancer patients with a limited prognosis who are likely to have palliative care needs [21, 22]. In order to participate, patients must have an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) of 0, 1, or 2. ECOG PS is a simple prognostic tool which enables clinicians to estimate median survival time for outpatients with advanced cancer based on a patient's level of function, from normal activity (0) to death (5) [23]. For this efficacy trial, we exclude patients with an ECOG PS > 2 because they are less likely to receive care in an ambulatory setting, and their short median life expectancy (55 days) [23] limits their ability to participate in the full intervention. We also exclude patients with hematologic malignancies because the palliative care needs of this group are different [24, 25].

When available, we enroll a caregiver for each patient participant. Patients are asked to select as their caregiver the person most likely to accompany them to visits or to help with their care should they need it. Enrolling caregivers allows measurement of caregiver outcomes and also facilitates follow-up contact with patients who have high morbidity. Based on our pilot work, we expect that the majority of patient participants will be able to identify a caregiver [20]. However, we do not exclude patients unable to identify a caregiver because we expect that this group also has significant palliative care needs. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria for patients and caregivers are presented in Table 1. Finally, we enroll all clinicians at participating sites in order to monitor satisfaction, burden, intervention fidelity, and any changes in usual care.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for patient and caregiver participants.

| Patient Inclusion Criteria | Patient Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Adults (≥21 years old) | Unable to read and respond to questions in English |

| Metastatic solid tumors | Cognitive impairment or inability to consent to treatment, as determined by patient's oncologist |

| Oncologist “would not be surprised if patient died in the next year” | |

| Unable to complete baseline interview | |

| ECOG PS of ≤ 2 (ambulatory and capable of all self-care but unable to carry out any work activities; up and about > 50% of waking hours) | ECOG PS of 3 (capable of limited self-care; confined to bed or chair > 50% of waking hours) or 4 (cannot carry on any self-care; totally confined to bed or chair) |

| Planning to receive ongoing care from a participating oncologist and willing to be seen at least monthly | Hematologic malignancy |

| Caregiver Inclusion Criteria | Caregiver Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Adults (≥21 years old) | Unable to read and respond to questions in English |

| Family member or friend of an eligible patient | Unable to complete baseline interview |

C. Randomization

The unit of randomization is the oncology practice, defined as a unique location and provider group for outpatient oncology care. The unit of analysis is the patient and caregiver. Using a cluster-randomized design rather than randomizing by patient avoids the risk of contamination for an intervention that involves training clinic staff and implementing new care management strategies. Our statistician conducted randomization using R version 3.2.3 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) in a 1:1 ratio, stratified by practice size, which was measured by the number of patients with metastatic solid tumors seen in 2015.

D. Recruitment / Informed Consent

In order to avoid recruitment bias, we employ a non-Zelen design in which patient and caregiver participants complete the informed consent process prior to learning of their site's randomization group [26]. Designated staff at each practice review upcoming appointments lists to identify potentially eligible patients who have metastatic solid tumors and meet the “surprise” criteria. At their next scheduled appointment, potentially eligible patients receive a 1-page study introduction sheet and are asked by a clinician whether they would be willing to learn more about the study. If the patient is willing to learn more, the consent process in conducted in-person by a trained research staff member. Each patient is asked to identify a caregiver, who also provides written informed consent. Once written informed consent is obtained, study staff and participating oncologists verify patient and caregiver eligibility, and participants are informed of their site's randomization group.

E. CONNECT Intervention

CONNECT Nurses

The decision to train existing oncology nurses to deliver primary palliative care via CONNECT, rather than research or palliative care nurses, is innovative and allows for the integration of this intervention into clinical practice. CONNECT leverages existing nurse-oncologist relationships and oncology nurses’ familiarity with oncology patients and clinic culture. Additionally, oncology nurses are available in all oncology practices, maximizing the potential for future widespread implementation.

CONNECT nurses are selected from oncology nurses currently practicing at the study sites by a Nurse Advisory board led by a nurse Project Manager with expertise in palliative oncology care. Participating clinics nominate candidates who have a minimum 5 years’ oncology and/or palliative care nursing experience, strong relationships with clinic providers and staff, an interest in learning new skills, excellent communication and interpersonal skills, excellent time management and organizational skills, flexibility, and a commitment to palliative oncology care. Oncology Clinical Nurse (OCN) certification is preferred but not required. Nurse advisory board members interview and select two nurses from each participating intervention practice to be trained to conduct the CONNECT intervention.

CONNECT Training

CONNECT nurses participate in a three-day training led by experts in communication and oncology nursing education. The majority of training time is interactive, using case studies with simulated patients to allow nurses to practice new skills and receive feedback. Nurses are provided with a protocolized intervention manual which outlines (1) the key content and goals for each CONNECT visit, (2) communication pearls, (3) common pitfalls, and (4) sample scripts, as well as evidence-based approaches to key competencies. The training focuses on four primary palliative care competencies: (1) addressing symptom needs, (2) engaging patients and caregivers in advance care planning, (3) providing emotional support to patients and caregivers, and (4) communicating and coordinating appropriate care. Upon completion of the 3-day training, nurses complete a self-evaluation and participate in observed visits with a simulated patient. Nurses are certified as CONNECT nurses once they report feeling fully prepared and demonstrate competency in key skills during observed visits. Certification is required prior to conducting intervention visits with study patients.

CONNECT Timing, Delivery, and Materials

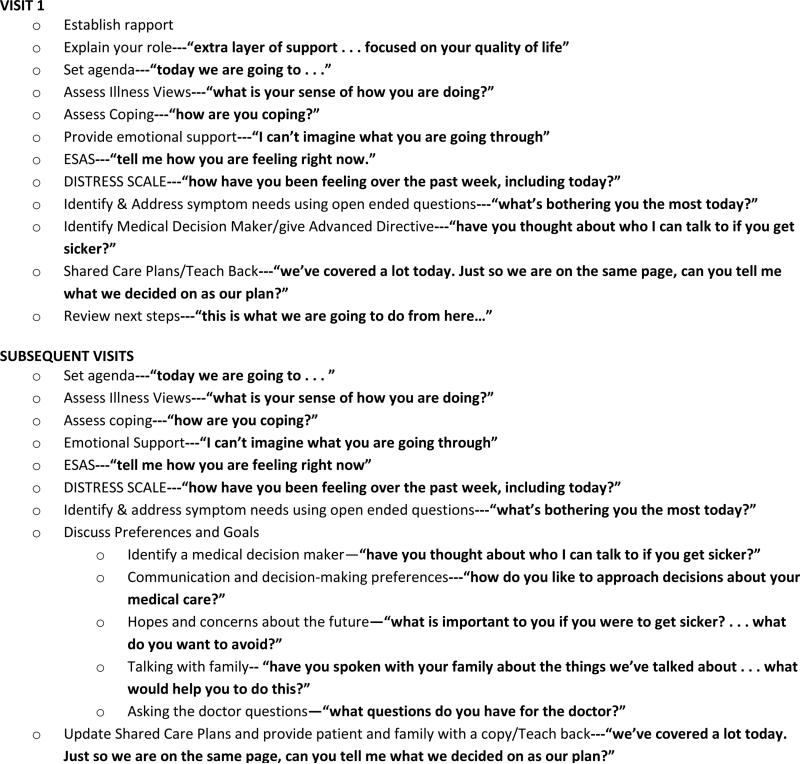

CONNECT visits occur at least monthly for three months, before and/or after regularly scheduled oncology clinic visits. The first visit focuses on establishing rapport, addressing symptom needs, and choosing a surrogate decision maker. Later visits additionally focus on discussing future treatment preferences and goals, and completing an advance directive. CONNECT nurses receive cue cards that outline the key components of each visit with associated communication pearls (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Key components of CONNECT intervention visits and communication pearls.

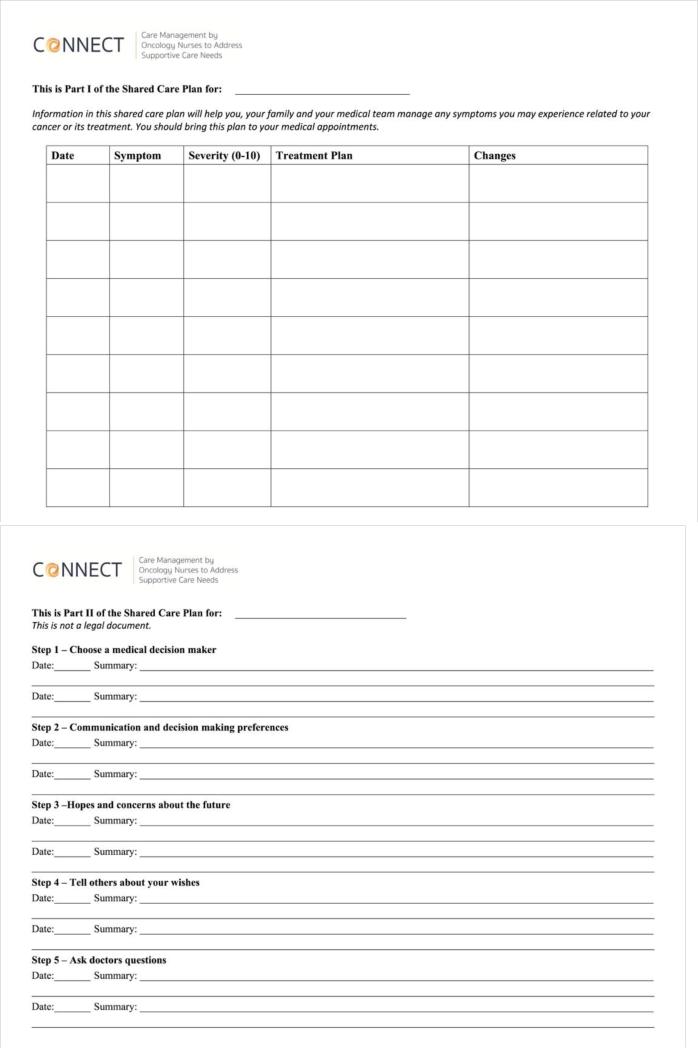

Patients complete the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS) [27, 28] and Distress Thermometer [29] at the start of each visit, with these assessments used to guide visit content. Shared care plans, completed during every visit, facilitate patient and caregiver involvement in addressing symptom needs and the process of advance care planning (see Figure 2). After each visit, the nurse checks in with the oncologist regarding the patient's symptoms, preferences, and goals. These check-ins range from simple updates to more complex requests for medication changes or discussions about goals of care. Within 1 week, the nurse calls the patient to follow up and identify any problems with visit plan.

Figure 2.

The shared care plan is completed at every visit.

Monitoring and Maintaining Intervention Fidelity

The Intervention Fidelity Monitoring and Maintenance plan is designed to ensure high quality and consistent delivery of the CONNECT intervention, reduce drift in adherence to the study protocol, and ensure the ability to draw accurate conclusions about treatment efficacy from our results. Weekly feedback sessions with the nurse project manager and biannual group booster trainings are designed for skills maintenance and support. In addition, CONNECT intervention visits are audio-recorded and a randomly-selected twenty percent are reviewed by study investigators for fidelity and quality. If protocol adherence drops below 80%, the Nurse Advisory Board will develop a remediation plan. If remediation is not successful, a new CONNECT nurse may be trained. If a CONNECT nurses’ intervention quality scores drop below 66%, the nurse project manager and principal investigator will provide supplemental training targeted at specific skill deficits, and the nurse will be re-evaluated.

F. Usual Care Control

We selected usual care as the control condition because our primary goal is to assess the impact of CONNECT as compared to existing practices in oncology clinics. Alternative control conditions that we considered but rejected were specialty palliative care co-management and an attention control condition. Specialty palliative care co-management was rejected because many patients lack access to it. Attention control was rejected because we felt that nonspecific attention may affect the outcomes we are measuring.

Usual care at participating clinics involves oncology nurses administering chemotherapy for 8-10 patients per day. Patient-reported symptom assessment measures are not routinely reviewed by nurses. Advance directives are available but not routinely discussed.

Participating clinics will be monitored throughout the study to assess any systems-level changes in usual care practices. Provision of specialty palliative care in the usual care group will be monitored via monthly telephone-based questionnaires.

G. Outcome Measures

All patient and caregiver-reported outcomes are assessed by a blinded research assistant who telephones patients and caregivers at baseline and 3 months. If a participant cannot be reached by telephone, a paper survey is mailed. The primary outcome is quality of life, measured at baseline and three months using the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy -- Palliative Care (FACIT-Pal). We chose the three-month time point to allow enough time for intervention delivery while minimizing loss to follow-up in this seriously ill cohort. We also sought consistency with recent palliative care trials [8, 9]. Additional patient- and caregiver-reported measures were chosen to answer key research questions while minimizing participant burden (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Patient- and caregiver-reported outcome measures.

| Outcome | Participant | Measure | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of Life Primary Outcome |

Patient | FACIT-PAL Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy -- Palliative Care |

Measures physical, social, emotional, & functional well-being with a palliative care subscale developed to identify quality of life concerns for patients with advanced cancer [31-33] |

| Symptom Burden | Patient | ESAS Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale |

Patient-rated symptom scale developed & validated in cancer patients receiving palliative care [27, 28, 34] |

| Self-efficacy | Patient | Cancer Behavior Inventory-Brief version | Measures self-efficacy for coping with cancer [35] |

| Patient-oncologist Relationship | Patient | Human Connection Scale | Measures therapeutic alliance between patients with advanced cancer and their physicians [36] |

| Distress | Patient | NCCN Distress Thermometer | Measures distress in patients with cancer on a 0-10 scale [29] |

| Hope | Patient and Caregiver | Herth Hope Index | Abbreviated instrument to assess hope in adults in clinical settings [37] |

| Mood | Patient and Caregiver | HADS Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

Measures symptoms of anxiety & depression, extensively validated for screening emotional distress among advanced cancer patients and family members [38-41] |

| Caregiver Burden | Caregiver | Zarit Burden Interview – Short version | Self-report of burden experienced while providing care to a loved one, shorter version of widely used measure [42] |

| Self-efficacy | Caregiver | Caregiver Inventory | A measure of self-efficacy for caregivers; includes assessment of self-care and communication [43] |

| Satisfaction | Caregiver | FAMCARE-2 | Measures family caregiver satisfaction with care in a variety of palliative care settings [44, 45] |

Monthly telephone calls, conducted by a blinded research assistant for up to one year or until the patient's death, are used to collect healthcare utilization data and enhance retention. Healthcare utilization data collected includes days in the hospital, days in the intensive care unit, emergency department visits, timing and type of cancer treatments, specialty palliative care use, mental health care use, and hospice use. If necessary, healthcare utilization is verified through patients’ medical records. Nursing time spent on the CONNECT intervention is also tracked for each patient.

H. Statistical Analysis

We will evaluate the statistical properties of baseline and follow-up outcome measures for potential outliers, normality, and missing data. For continuous variables, we will compute measures of central tendency and dispersion. For categorical data, we will compute frequency distributions.

We will assess the effectiveness of randomization by comparing baseline characteristics for clinics, patients, and caregivers between randomized groups. Analyses for treatment group comparisons will use an intention-to-treat approach. Results will be reported using the CONSORT extension to cluster randomized trials [45]. In order to assess for dose response, we will conduct a secondary analysis that investigates the relationship between the number of intervention visits and the outcome measures.

To investigate the effect of CONNECT intervention on each patient- and caregiver-level outcome of interest, we will compare the 3-month measurement of each outcome between the intervention and usual care groups using linear mixed models. For each model, we will adjust for baseline measurement of the outcome, as well as clinical characteristics of the patient, caregiver, or clinic associated with the outcome by including them as fixed effects. Clinics will be included as random effects to allow for clustering effect within each clinic.

Healthcare utilization costs will be estimated from the third party payer perspective. Costs of procedures, hospitalizations, and provider office visits will be estimated using Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project data[46] or Medicare reimbursement data [47] as appropriate. Medication class-specific average wholesale prices will be used to estimate medication costs. The average hourly wage for U.S. nursing staff of comparable levels [48] will be used to estimate the cost of nurses’ training and patient care time spent on CONNECT.

To test the effect of the intervention on healthcare utilization, we will use generalized linear mixed models. We will use logit link (binary distribution) for dichotomous health care outcomes such as hospice use, Poisson or negative binomial distribution for outcomes resulting in count data such as number of hospitalizations, and Poisson or gamma distributions for cost outcomes. Survival time will be estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method.

Sample size

Sample size calculations accounted for the effects of cluster randomization. To detect an 11-point difference in FACIT-Pal, an effect size of 0.45, with 83% power, taking into account cluster randomization effects (using an intra-class correlation coefficient of 0.03), n=400 patients and 16 sites (clusters) are needed. Conservatively estimating 40% attrition due to death or loss to follow-up, the targeted sample size was increased to 672 patients at 16 clinics.

I Discussion

CONNECT is a cluster randomized controlled trial comparing oncology nurse-led primary palliative care to usual care among patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers. The trial will evaluate whether the CONNECT intervention improves patient quality of life (primary outcome), symptom burden, mood, and caregiver outcomes, as well as assess the impact of primary palliative care on healthcare resource use near the end of life.

Our trial is timely in addressing the need for new models of palliative care that can be widely disseminated. The supply of palliative care specialists has not kept pace with the demand for palliative care services, particularly outside academic cancer centers, where the majority of patients with cancer receive care. Severe physician workforce shortages limit the potential for expansion of specialty palliative care [16], while the nursing workforce in the US continues to grow [49]. While previous studies have evaluated nurse-led palliative care interventions [10, 11, 50], our study is innovative in identifying, training and supporting existing oncology nurses to deliver primary palliative care, allowing dissemination of our findings into clinical practice.

Providing primary palliative care is not currently the focus of oncology nursing practice [51], though many nurses cite palliative care skills as among the most important and fulfilling parts of their job. Our approach seeks to overcome potential barriers to oncology nursing provision of primary palliative care, including a lack of education and support for these activities [52, 53], while leveraging the strengths oncology nurses bring to this role, including familiarity with patients and clinic culture and established relationships with physicians.

If efficacious, the CONNECT intervention offers an approach to palliative care provision in oncology that is widely-available and likely cost effective. Additional effectiveness and implementation research will then be warranted to inform translation of these research findings into routine practice.

Our trial design addresses common sources of bias in palliative care trials, including selection bias, lack of blinding, and contamination. Selection bias is avoided by approaching all patients who meet initial eligibility criteria at participating clinics during recruitment periods. Importantly, we also consent patients and caregivers prior to informing them of their study site's randomization group, in order to avoid the risk that different types of patients may consent to participate in either the intervention or usual care group. While the inability to blind participating patients and nurses makes it impossible to completely avoid performance bias, outcome data is collected via telephone by blinded study personnel. Contamination of participants assigned to usual care and intervention groups is avoided by using a cluster randomized design, in which the unit of randomization is the oncology clinic practice.

Pre-specified outcomes were chosen to facilitate understanding of the impact of primary palliative care on patients, caregivers, and healthcare utilization. We enroll a caregiver for each patient if possible, include caregivers in shared care plans and advance care planning, and assess caregiver burden and mood, among other outcomes. Healthcare utilization data, collected monthly, and nursing time spent on CONNECT will be used to assess the cost effectiveness of the intervention. As health systems work to improve patient-centered outcomes such as quality of life, increasingly focus on caregiver experiences, and seek to decrease costs, accounting for the impact of palliative care interventions on this breadth of outcomes is increasingly important.

Acknowledgements

This trial is supported by R01CA197103 from the National Cancer Institute. This project used UPCI clinical facilities that are supported in part by award P30CA047904. In addition, the work was supported by NIH grant T32AG21885-13 awarded to CB.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Downey L, Engelberg RA. Quality-of-Life Trajectories at the End of Life: Assessments over Time by Patients with and without Cancer. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2010;58(3):472–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02734.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teunissen SC, Wesker W, Kruitwagen C, de Haes HC, Voest EE, de Graeff A. Symptom prevalence in patients with incurable cancer: a systematic review. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2007;34(1):94–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breitbart W, Bruera E, Chochinov H, Lynch M. Neuropsychiatric syndromes and psychological symptoms in patients with advanced cancer. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 1995;10(2):131–141. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(94)00075-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hotopf M, Chidgey J, Addington-Hall J, Ly KL. Depression in advanced disease: a systematic review Part 1. Prevalence and case finding. Palliative medicine. 2002;16(2):81–97. doi: 10.1191/02169216302pm507oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Schafenacker AM, Weiss D. The impact of caregiving on the psychological well-being of family caregivers and cancer patients. Seminars in oncology nursing. 2012;28(4):236–245. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morden NE, Chang C-H, Jacobson JO, Berke EM, Bynum JP, Murray KM, Goodman DC. Endof-life care for Medicare beneficiaries with cancer is highly intensive overall and varies widely. Health affairs. 2012;31(4):786–796. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheung MC, Earle CC, Rangrej J, Ho TH, Liu N, Barbera L, Saskin R, Porter J, Seung SJ, Mittmann N. Impact of aggressive management and palliative care on cancer costs in the final month of life. Cancer. 2015;121(18):3307–3315. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, Hannon B, Leighl N, Oza A, Moore M, Rydall A, Rodin G, Tannock I. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2014;383(9930):1721–1730. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62416-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, Dahlin CM, Blinderman CD, Jacobsen J, Pirl WF. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363(8):733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, Balan S, Brokaw FC, Seville J, Hull JG, Li Z, Tosteson TD, Byock IR. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2009;302(7):741–749. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dionne-Odom JN, Azuero A, Lyons KD, Hull JG, Tosteson T, Li Z, Li Z, Frost J, Dragnev KH, Akyar I. Benefits of early versus delayed palliative care to informal family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer: outcomes from the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. Journal of clinical oncology. 2015;13(33):1446–1452. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.7824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun V, Grant M, Koczywas M, Freeman B, Zachariah F, Fujinami R, Ferraro CD, Uman G, Ferrell B. Effectiveness of an interdisciplinary palliative care intervention for family caregivers in lung cancer. Cancer. 2015;121(20):3737–3745. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greer JA, Pirl WF, Jackson VA, Muzikansky A, Lennes IT, Heist RS, Gallagher ER, Temel JS. Effect of early palliative care on chemotherapy use and end-of-life care in patients with metastatic non– small-cell lung cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30(4):394–400. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.7996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferrell TJBR, Temin s, Alesi ER, Balboni TA, Ethan Basch E, Firn J, Paice JA, Peppercorn JM, Phillips T, Strasser F, Zimmermann C, Smith TJ. The Integration of Palliative Care into Standard Oncology Care: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. Journal of clinical oncology. 2016 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.1474. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hui D, Elsayem A, De La Cruz M, Berger A, Zhukovsky DS, Palla S, Evans A, Fadul N, Palmer JL, Bruera E. Availability and integration of palliative care at US cancer centers. Jama. 2010;303(11):1054–1061. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lupu D, Force PMWT. Estimate of current hospice and palliative medicine physician workforce shortage. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2010;40(6):899–911. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. [06.17.16];American Board of Internal Medicine Candidates Certified. 2016 http://www.abim.org/~/media/ABIM%20Public/Files/pdf/statistics-data/candidates-certified-all-candidates.pdf.

- 18.Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care—creating a more sustainable model. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;368(13):1173–1175. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1215620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schenker Y, Arnold R. The next era of palliative care. JAMA. 2015;314(15):1565–1566. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.11217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schenker Y, White D, Rosenzweig M, Chu E, Moore C, Ellis P, Nikolajski P, Ford C, Tiver G, McCarthy L. Care management by oncology nurses to address palliative care needs: a pilot trial to assess feasibility, acceptability, and perceived effectiveness of the CONNECT intervention. Journal of palliative medicine. 2015;18(3):232–240. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2014.0325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moss AH, Lunney JR, Culp S, Auber M, Kurian S, Rogers J, Dower J, Abraham J. Prognostic significance of the “surprise” question in cancer patients. Journal of palliative medicine. 2010;13(7):837–840. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Billings JA, Bernacki R. Strategic targeting of advance care planning interventions: the Goldilocks phenomenon. JAMA internal medicine. 2014;174(4):620–624. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.14384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jang RW, Caraiscos VB, Swami N, Banerjee S, Mak E, Kaya E, Rodin G, Bryson J, Ridley JZ, Le LW. Simple prognostic model for patients with advanced cancer based on performance status. Journal of Oncology Practice. 2014;10(5):e335–e341. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.LeBlanc TW, O'Donnell JD, Crowley-Matoka M, Rabow MW, Smith CB, White DB, Tiver GA, Arnold RM, Schenker Y. Perceptions of palliative care among hematologic malignancy specialists: a mixed-methods study. Journal of Oncology Practice. 2015;11(2):e230–e238. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.LeBlanc TW, Abernethy AP, Casarett DJ. What is different about patients with hematologic malignancies? A retrospective cohort study of cancer patients referred to a hospice research network. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2015;49(3):505–512. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weijer C, Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP, McRae AD, White A, Brehaut JC, Taljaard M. The Ottawa statement on the ethical design and conduct of cluster randomized trials. PLoS Med. 2012;9(11):e1001346. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watanabe SM, Nekolaichuk CL, Beaumont C. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System, a proposed tool for distress screening in cancer patients: development and refinement. Psycho-Oncology. 2012;21(9):977–985. doi: 10.1002/pon.1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang VT, Hwang SS, Feuerman M. Validation of the Edmonton symptom assessment scale. Cancer. 2000;88(9):2164–2171. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000501)88:9<2164::aid-cncr24>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vitek L, Rosenzweig MQ, Stollings S. Distress in patients with cancer: definition, assessment, and suggested interventions. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2007;11(3):413. doi: 10.1188/07.CJON.413-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greisinger A, Lorimor R, Aday L, Winn R, Baile W. Terminally ill cancer patients. Their most important concerns. Cancer practice. 1996;5(3):147–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, Silberman M, Yellen SB, Winicour P, Brannon J. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. Journal of clinical oncology. 1993;11(3):570–579. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lyons KD, Bakitas M, Hegel MT, Hanscom B, Hull J, Ahles TA. Reliability and validity of the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-palliative care (FACIT-Pal) scale. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2009;37(1):23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bedard G, Zeng L, Zhang L, Lauzon N, Holden L, Tsao M, Danjoux C, Barnes E, Sahgal A, Poon M. Minimal clinically important differences in the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System in patients with advanced cancer. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2013;46(2):192–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heitzmann CA, Merluzzi TV, Jean-Pierre P, Roscoe JA, Kirsh KL, Passik SD. Assessing self-efficacy for coping with cancer: development and psychometric analysis of the brief version of the Cancer Behavior Inventory (CBI-B) Psycho-Oncology. 2011;20(3):302–312. doi: 10.1002/pon.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mack JW, Block SD, Nilsson M, Wright A, Trice E, Friedlander R, Paulk E, Prigerson HG. Measuring therapeutic alliance between oncologists and patients with advanced cancer. Cancer. 2009;115(14):3302–3311. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Herth K. Abbreviated instrument to measure hope: development and psychometric evaluation. Journal of advanced nursing. 1992;17(10):1251–1259. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1992.tb01843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta psychiatrica scandinavica. 1983;67(6):361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vodermaier A, Millman RD. Accuracy of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale as a screening tool in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2011;19(12):1899–1908. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1251-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dahlin C, Kelley JM, Jackson VA, Temel JS. Early palliative care for lung cancer: improving quality of life and increasing survival. International journal of palliative nursing. 2010;16(9):420–423. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2010.16.9.78633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pochard F, Darmon M, Fassier T, Bollaert P-E, Cheval C, Coloigner M, Merouani A, Moulront S, Pigne E, Pingat J. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in family members of intensive care unit patients before discharge or death. A prospective multicenter study. Journal of critical care. 2005;20(1):90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bédard M, Molloy DW, Squire L, Dubois S, Lever JA, O'Donnell M. The Zarit Burden interview a new short version and screening version. The gerontologist. 2001;41(5):652–657. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.5.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Merluzzi TV, Philip EJ, Vachon DO, Heitzmann CA. Assessment of self-efficacy for caregiving: The critical role of self-care in caregiver stress and burden. Palliative and Supportive Care. 2011;9(01):15–24. doi: 10.1017/S1478951510000507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aoun S, Bird S, Kristjanson LJ, Currow D. Reliability testing of the FAMCARE-2 scale: measuring family carer satisfaction with palliative care. Palliative medicine. 2010;24(7):674–681. doi: 10.1177/0269216310373166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lo C, Burman D, Hales S, Swami N, Rodin G, Zimmermann C. The FAMCARE-Patient scale: Measuring satisfaction with care of outpatients with advanced cancer. European Journal of Cancer. 2009;45(18):3182–3188. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Campbell MK, Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Altman DG. Consort 2010 statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ. 2012;345:e5661. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. [09.16.16];Healthcare Cost and Utlization Project Query System. http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov.

- 47.Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services Physician Fee Schedule Look-Up Tool [09.16.16]; https://www.cms.hhs.gov/PFSLookup/

- 48. [09.16.16];Bureau of Labor Statistics Occupational Employment Statistics. http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes291141.htm.

- 49.Bodenheimer T, Bauer L. Rethinking the Primary Care Workforce — An Expanded Role for Nurses. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;375(11):1015–1017. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1606869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Connors AF, Dawson NV, Desbiens NA, Fulkerson WJ, Goldman L, Knaus WA, Lynn J, Oye RK, Bergner M, Damiano A. A controlled trial to improve care for seriously iII hospitalized patients: The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT) Jama. 1995;274(20):1591–1598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Davison J, Schenker Y, Donovan H, Rosenzweig M. A Work Sampling Assessment of the Nursing Delivery of Palliative Care in Ambulatory Cancer Centers. Clinical journal of oncology nursing. 2016;20(4):421. doi: 10.1188/16.CJON.421-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fitch MI, Fliedner MC, O'Connor M. Nursing perspectives on palliative care 2015. Annals of palliative medicine. 2015;4(3):150–155. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2224-5820.2015.07.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.White KR, Coyne PJ. Nurses' perceptions of educational gaps in delivering end-of-life care. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2011;38(6):711–717. doi: 10.1188/11.ONF.711-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]