Abstract

Migraine is a debilitating neurological disorder affecting around 1 in 7 people worldwide, but its molecular mechanisms remain poorly understood. Some debate exists over whether migraine is a disease of vascular dysfunction or a result of neuronal dysfunction with secondary vascular changes. Genome-wide association (GWA) studies have thus far identified 13 independent loci associated with migraine. To identify new susceptibility loci, we performed the largest genetic study of migraine to date, comprising 59,674 cases and 316,078 controls from 22 GWA studies. We identified 44 independent single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) significantly associated with migraine risk (P < 5 × 10−8) that map to 38 distinct genomic loci, including 28 loci not previously reported and the first locus identified on chromosome X. In subsequent computational analyses, the identified loci showed enrichment for genes expressed in vascular and smooth muscle tissues, consistent with a predominant theory of migraine that highlights vascular etiologies.

Migraine is ranked as the third most common disease worldwide, with a lifetime prevalence of 15–20%, affecting up to one billion people across the globe1,2. It ranks as the 7th most disabling of all diseases worldwide (or 1st most disabling neurological disease) in terms of years of life lost to disability1 and is the 3rd most costly neurological disorder after dementia and stroke3. There is debate about whether migraine is a disease of vascular dysfunction, or a result of neuronal dysfunction with vascular changes representing downstream effects not themselves causative of migraine4,5. However, genetic evidence favoring one theory versus the other is lacking. At the phenotypic level, migraine is defined by diagnostic criteria from the International Headache Society6. There are two prevalent sub-forms: migraine without aura is characterized by recurrent attacks of moderate or severe headache associated with nausea or hypersensitivity to light and sound. Migraine with aura is characterized by transient visual, sensory, or speech symptoms usually followed by a headache phase similar to migraine without aura.

Family and twin studies estimate a heritability of 42% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 36–47%) for migraine7, pointing to a genetic component of the disease. Despite this, genetic association studies have revealed relatively little about the molecular mechanisms that contribute to pathophysiology. Understanding has been limited partly because, to date, only 13 genome-wide significant risk loci have been identified for the prevalent forms of migraine8–11. In familial hemiplegic migraine (FHM), a rare Mendelian form of the disease, three ion transport-related genes (CACNA1A, ATP1A2 and SCN1A) have been implicated12–14. These findings suggest that mechanisms that regulate neuronal ion homeostasis might also be involved in migraine more generally, however, no genes related to ion transport have yet been identified for these more prevalent forms of migraine15.

We performed a meta-analysis of 22 genome-wide association (GWA) studies, consisting of 59,674 cases and 316,078 controls collected from six tertiary headache clinics and 27 population-based cohorts through our worldwide collaboration in the International Headache Genetics Consortium (IHGC). This combined dataset contained over 35,000 new migraine cases not included in previously published GWA studies. Here we present the findings of this new meta-analysis, including 38 genomic loci, harboring 44 independent association signals identified at levels of genome-wide significance, which support current theories of migraine pathophysiology and also offer new insights into the disease.

RESULTS

Significant associations at 38 independent genomic loci

The primary meta-analysis was performed on all migraine samples available through the IHGC, regardless of ascertainment. These case samples included both individuals diagnosed by a doctor as well as individuals with self-reported migraine via questionnaires. Study design and sample ascertainment for each individual study is outlined in the Supplementary Note (and summarized in Supplementary Table 1). The final combined sample consisted of 59,674 cases and 316,078 controls in 22 non-overlapping case-control datasets (Table 1). All samples were of European ancestry. Before including the largest study from 23andMe, we confirmed that it did not contribute any additional heterogeneity compared to the other population and clinic-based studies (Supplementary Table 2).

Table 1.

Individual IHGC GWA studies listed with cases and control numbers used in the primary analysis (all migraine) and in the subtype analyses (migraine with aura and migraine without aura). Note that chromosome X genotype data was unavailable from three of the individual GWA studies (EGCUT, Rotterdam III, and TwinsUK) and also partially unavailable from some of the control samples (specifically the GSK controls) used for the ‘German MO’ study, meaning that the number of samples analyzed on chromosome X was 57,756 cases and 299,109 controls. Complete data was available on the autosomes for all samples.

| GWA Study ID | Full Name of GWA Study | All migraine | Migraine with aura | Migraine without aura | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | ||

| 23andMe | 23andMe Inc. | 30,465 | 143,147 | - | - | - | - |

| ALSPAC | Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children | 3,134 | 5,103 | - | - | - | - |

| ATM | Australian Twin Migraine | 1,683 | 2,383 | - | - | - | - |

| B58C | 1958 British Birth Cohort | 1,165 | 4,141 | - | - | - | - |

| Danish HC | Danish Headache Center | 1,771 | 1,000 | 775 | 1,000 | 996 | 1,000 |

| DeCODE | deCODE Genetics Inc. | 3,135 | 95,585 | 366 | 95,585 | 608 | 95,585 |

| Dutch MA | Dutch migraine with aura | 734 | 5,211 | 734 | 5,211 | - | - |

| Dutch MO | Dutch migraine without aura | 1,115 | 2,028 | - | - | 1,115 | 2,028 |

| EGCUT | Estonian Genome Center, University of Tartu | 813 | 9,850 | 76 | 9,850 | 94 | 9,850 |

| Finnish MA | Finnish migraine with aura | 933 | 2,715 | 933 | 2,715 | - | - |

| German MA | German migraine with aura | 1,071 | 1,010 | 1,071 | 1,010 | - | - |

| German MO | German migraine without aura | 1,160 | 1,647 | - | - | 1,160 | 1,647 |

| HUNT | Nord-Trøndelag Health Study | 1,395 | 1,011 | 290 | 1,011 | 980 | 1,011 |

| NFBC | Northern Finnish Birth Cohort | 756 | 4,393 | - | - | - | - |

| NTR/NESDA | Netherlands Twin Register and the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety |

1,636 | 3,819 | 544 | 3,819 | 615 | 3,819 |

| Rotterdam III | Rotterdam Study III | 487 | 2,175 | 106 | 2,175 | 381 | 2,175 |

| Swedish Twins | Swedish Twin Registry | 1,307 | 4,182 | - | - | - | - |

| Tromsø | The Tromsø Study | 660 | 2,407 | - | - | - | - |

| Twins UK | Twins UK | 618 | 2,334 | 202 | 2,334 | 416 | 2,334 |

| WGHS | Women’s Genome Health Study | 5,122 | 18,108 | 1,177 | 18,108 | 1,826 | 18,108 |

| Young Finns | Young Finns | 378 | 2,065 | 58 | 2,065 | 157 | 2,065 |

| Total: | 59,674 | 316,078 | 6,332 | 144,883 | 8,348 | 139,622 | |

The 22 individual GWA studies completed standard quality control protocols (Online Methods) summarized in Supplementary Table 3. Missing genotypes were then imputed into each sample using a common 1000 Genomes Project reference panel16. Association analyses were performed within each study using logistic regression on the imputed marker dosages while adjusting for sex and other covariates where necessary (Online Methods and Supplementary Table 4). The association results were combined using an inverse-variance weighted fixed-effects meta-analysis. Markers were filtered for imputation quality and other metrics (Online Methods) leaving 8,094,889 variants for consideration in our primary analysis.

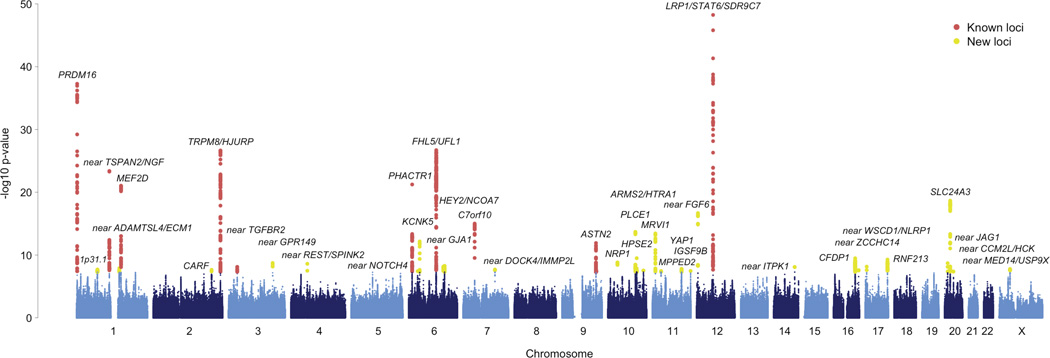

Among these variants in the primary analysis, we identified 44 genome-wide significant SNP associations (P < 5 × 10−8, Supplementary Figure 1) that are independent (r2 < 0.1) with regards to linkage disequilibrium (LD). We validated the 44 SNPs by comparing genotypes in a subset of the sample to those obtained from whole-genome sequencing (Supplementary Table 5). To help identify candidate risk genes from these, we defined an associated locus as the genomic region bounded by all markers in LD (r2 > 0.6 in 1000 Genomes, Phase I, EUR individuals) with each of the 44 index SNPs and in addition, all such regions in close proximity (< 250 kb) were merged. From these defined regions we implicate 38 genomic loci for the prevalent forms of migraine, 28 of which have not previously been reported (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Manhattan plot of the primary meta-analysis of all migraine (59,674 cases vs. 316,078 controls). Each marker was tested for association using an additive genetic model by logistic regression adjusted for sex. A fixed-effects meta-analysis was then used to combine the association statistics from all 22 clinic and population-based studies. The horizontal axis shows the chromosomal position and the vertical axis shows the significance of tested markers from logistic regression. Markers that reach genome-wide significance (P < 5 × 10−8) at previously known and newly identified loci are highlighted according to the color legend.

These 38 loci replicate 10 of the 13 previously reported genome-wide associations to migraine and six loci contain a secondary genome-wide significant SNP not in LD (r2 < 0.1) with the top SNP in the locus (Table 2). Five of these secondary signals were found in known loci (at LRP1/STAT6/SDR9C7, PRDM16, FHL5/UFL1, TRPM8/HJURP, and near TSPAN2/NGF), while the sixth was found within one of the 28 new loci (PLCE1). Therefore, out of the 44 independent SNPs reported here, 34 represent new associations to migraine. Three previously reported loci that were associated to subtypes of migraine (rs1835740 near MTDH for migraine with aura, rs10915437 near AJAP1 for migraine clinical-samples, and rs10504861 near MMP16 for migraine without aura)8,11 show only nominal significance in the current meta-analysis (P = 5 × 10−3 for rs1835740, P = 4.4 × 10−5 for rs10915437, and P = 4.9 × 10−5 for rs10504861, Supplementary Table 6), however, these loci have since been shown to be associated to specific phenotypic features of migraine17 and therefore may require a more phenotypically homogeneous sample to be accurately assessed for association. Four out of 44 SNPs (at TRPM8/HJURP, near ZCCHC14, MRVI1, and near CCM2L/HCK) exhibited moderate heterogeneity across the individual GWA studies (Cochran’s Q P-value < 0.05, Supplementary Table 7) therefore at these markers we applied a random effects model18.

Table 2.

Summary of the 38 genomic loci associated with the prevalent types of migraine. Ten loci were previously reported (PubMed IDs listed) and 28 are newly found in this study. Each locus is labeled with protein coding genes that overlap the region. Intergenic loci are also labeled with the prefix “near” to highlight the additional uncertainty in identifying relevant genes. Effect sizes and P-values for each SNP were calculated for each study with an additive genetic model using logistic regression adjusted for sex and then combined in a fixed-effects meta-analysis. For loci that contain a secondary LD-independent signal passing genome-wide significance, the secondary index SNP and P-value is given. For the seven loci reaching genome-wide significance in the migraine without aura sub-type analysis, the corresponding index SNP and P-value are also given. Evidence for significant heterogeneity was found at four loci (TRPM8/HJURP, MRVI1, near ZCCHC14, and near CCM2L/HCK) so for those we present the results of a random-effects model.

| Locus Rank |

Locus | Chr | Index SNP | Minor Allele |

MAF | All Migraine | Secondary signal | Migraine without aura | Previous Publication PMID |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR [95% CI] | P | Index SNP | P | Index SNP | P | |||||||

| 1 | LRP1/STAT6/SDR9C7 | 12 | rs11172113 | C | 0.42 | 0.90 [0.89–0.91] | 5.6 × 10−49 | rs11172055 | 1.3 × 10−09 | rs11172113 | 4.3 × 10−16 | 21666692 |

| 2 | PRDM16 | 1 | rs10218452 | G | 0.22 | 1.11 [1.10–1.13] | 5.3 × 10−38 | rs12135062 | 3.7 × 10−10 | - | - | 21666692 |

| 3 | FHL5/UFL1 | 6 | rs67338227 | T | 0.23 | 1.09 [1.08–1.11] | 2.0 × 10−27 | rs4839827 | 5.7 × 10−10 | rs7775721 | 1.1 × 10−12 | 23793025 |

| 4 | near TSPAN2/NGF | 1 | rs2078371 | C | 0.12 | 1.11 [1.09–1.13] | 4.1 × 10−24 | rs7544256 | 8.7 × 10−09 | rs2078371 | 7.4 × 10−09 | 23793025 |

| 5 | TRPM8/HJURP | 2 | rs10166942 | C | 0.20 | 0.94 [0.89–0.99] | 1.0 × 10−23 | rs566529 | 2.5 × 10−09 | rs6724624 | 1.1 × 10−09 | 21666692 |

| 6 | PHACTR1 | 6 | rs9349379 | G | 0.41 | 0.93 [0.92–0.95] | 5.8 × 10−22 | - | - | rs9349379 | 2.1 × 10−09 | 22683712 |

| 7 | MEF2D | 1 | rs1925950 | G | 0.35 | 1.07 [1.06–1.09] | 9.1 × 10−22 | - | - | - | - | 22683712 |

| 8 | SLC24A3 | 20 | rs4814864 | C | 0.26 | 1.07 [1.06–1.09] | 2.2 × 10−19 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 9 | near FGF6 | 12 | rs1024905 | G | 0.47 | 1.06 [1.04–1.08] | 2.1 × 10−17 | - | - | rs1024905 | 2.5 × 10−09 | - |

| 10 | C7orf10 | 7 | rs186166891 | T | 0.11 | 1.09 [1.07–1.12] | 9.7 × 10−16 | - | - | - | - | 23793025 |

| 11 | PLCE1 | 10 | rs10786156 | G | 0.45 | 0.95 [0.94–0.96] | 2.0 × 10−14 | rs75473620 | 5.8 × 10−09 | - | - | - |

| 12 | KCNK5 | 6 | rs10456100 | T | 0.28 | 1.06 [1.04–1.07] | 6.9 × 10−13 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 13 | ASTN2 | 9 | rs6478241 | A | 0.36 | 1.05 [1.04–1.07] | 1.2 × 10−12 | - | - | rs6478241 | 1.2 × 10−10 | 22683712 |

| 14 | MRVI1 | 11 | rs4910165 | C | 0.33 | 0.94 [0.91–0.98] | 2.9 × 10−11 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 15 | HPSE2 | 10 | rs12260159 | A | 0.07 | 0.92 [0.89–0.94] | 3.2 × 10−10 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 16 | CFDP1 | 16 | rs77505915 | T | 0.45 | 1.05 [1.03–1.06] | 3.3 × 10−10 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 17 | RNF213 | 17 | rs17857135 | C | 0.17 | 1.06 [1.04–1.08] | 5.2 × 10−10 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 18 | NRP1 | 10 | rs2506142 | G | 0.17 | 1.06 [1.04–1.07] | 1.5 × 10−09 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 19 | near GPR149 | 3 | rs13078967 | C | 0.03 | 0.87 [0.83–0.91] | 1.8 × 10−09 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 20 | near JAG1 | 20 | rs111404218 | G | 0.34 | 1.05 [1.03–1.07] | 2.0 × 10−09 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 21 | near REST/SPINK2 | 4 | rs7684253 | C | 0.45 | 0.96 [0.94–0.97] | 2.5 × 10−09 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 22 | near ZCCHC14 | 16 | rs4081947 | G | 0.34 | 1.03 [1.00–1.06] | 2.5 × 10−09 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 23 | HEY2/NCOA7 | 6 | rs1268083 | C | 0.48 | 0.96 [0.95–0.97] | 5.3 × 10−09 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 24 | near WSCD1/NLRP1 | 17 | rs75213074 | T | 0.03 | 0.89 [0.86–0.93] | 7.1 × 10−09 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 25 | near GJA1 | 6 | rs28455731 | T | 0.16 | 1.06 [1.04–1.08] | 7.3 × 10−09 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 26 | near TGFBR2 | 3 | rs6791480 | T | 0.31 | 1.04 [1.03–1.06] | 7.8 × 10−09 | - | - | - | - | 22683712 |

| 27 | near ITPK1 | 14 | rs11624776 | C | 0.31 | 0.96 [0.94–0.97] | 7.9 × 10−09 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 28 | near ADAMTSL4/ECM1 | 1 | rs6693567 | C | 0.27 | 1.05 [1.03–1.06] | 1.2 × 10−08 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 29 | near CCM2L/HCK | 20 | rs144017103 | T | 0.02 | 0.85 [0.76–0.96] | 1.2 × 10−08 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 30 | YAP1 | 11 | rs10895275 | A | 0.33 | 1.04 [1.03–1.06] | 1.6 × 10−08 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 31 | near MED14/USP9X | X | rs12845494 | G | 0.27 | 0.96 [0.95–0.97] | 1.7 × 10−08 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 32 | near DOCK4/IMMP2L | 7 | rs10155855 | T | 0.05 | 1.08 [1.05–1.12] | 2.1 × 10−08 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 33 | 1p31.1* | 1 | rs1572668 | G | 0.48 | 1.04 [1.02–1.05] | 2.1 × 10−08 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 34 | CARF | 2 | rs138556413 | T | 0.03 | 0.88 [0.84–0.92] | 2.3 × 10−08 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 35 | ARMS2/HTRA1 | 10 | rs2223089 | C | 0.08 | 0.93 [0.91–0.95] | 3.0 × 10−08 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 36 | IGSF9B | 11 | rs561561 | T | 0.12 | 0.94 [0.92–0.96] | 3.4 × 10−08 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 37 | MPPED2 | 11 | rs11031122 | C | 0.24 | 1.04 [1.03–1.06] | 3.5 × 10−08 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 38 | near NOTCH4 | 6 | rs140002913 | A | 0.06 | 0.91 [0.88–0.94] | 3.8 × 10−08 | - | - | - | - | - |

The nearest coding gene (LRRIQ3) to this locus is 592kb away.

Characterization of the associated loci

In total, 32 of 38 (84%) loci overlap with transcripts from protein-coding genes, and 17 (45%) of these regions contain just a single gene (see Supplementary Figure 2 for regional association plots and Supplementary Table 8 for additional locus information). Among the 38 loci, only two contain ion channel genes (KCNK519 and TRPM820). Hence, despite previous hypotheses of migraine as a potential channelopathy5,21, the loci identified to date do not support common variants in ion channel genes as strong susceptibility components in prevalent forms of migraine. However, three other loci do contain genes involved more generally in ion homeostasis (SLC24A322, ITPK123, and GJA124, Supplementary Table 9).

Several of the genes have previous associations to vascular disease (PHACTR1,25,26 TGFBR2,27 LRP1,28 PRDM16,29 RNF213,30 JAG1,31 HEY2,32 GJA133, ARMS234), or are involved in smooth muscle contractility and regulation of vascular tone (MRVI1,35 GJA1,36 SLC24A3,37 NRP138). Three of the 44 migraine index SNPs have previously reported associations in the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) GWAS catalog at exactly the same SNP (rs9349379 at PHACTR1 with coronary heart disease39–41, coronary artery calcification42, and cervical artery dissection26; rs11624776 near ITPK1 with thyroid hormone levels43; and rs11172113 at LRP1/STAT6/SDR9C7 with pulmonary function44; Supplementary Table 10). Six of the loci harbor genes that are involved in nitric oxide signaling and oxidative stress (REST45, GJA146, YAP147, PRDM1648, LRP149, and MRVI150).

From each locus we chose the nearest gene to the index SNP to assess gene expression activity in tissues from the GTEx consortium (Supplementary Figure 3). While we found that most of the putative migraine loci genes were expressed in many different tissue types, we could detect tissue specificity in certain instances whereby some genes showed significantly higher expression in a particular tissue group relative to the others. For instance four genes were more actively expressed in brain (GPR149, CFDP1, DOCK4, and MPPED2) compared to other tissues, whereas eight genes were specifically active in vascular tissues (PRDM16, MEF2D, FHL5, C7orf10, YAP1, LRP1, ZCCHC14, and JAG1). Many other putative migraine loci genes were actively expressed in more than one tissue group.

Genomic inflation and LD-score regression analysis

To assess whether the 38 loci harbor true associations with migraine rather than reflecting systematic differences between cases and controls (such as population stratification) we analyzed the genome-wide inflation of test statistics in our primary meta-analysis. As expected for a complex polygenic trait, the distribution of test statistics deviates from the null (genomic inflation factor λGC = 1.24, Supplementary Figure 4) which is in line with other large GWA study meta-analyses51–54. Since much of the inflation in a polygenic trait arises from LD between the causal SNPs and many other neighboring SNPs in the local region, we LD-pruned the data to create a set of LD-independent markers (i.e. in PLINK55 with a 250-kb sliding window and r2 > 0.2). The resulting genomic inflation was reduced (λGC = 1.15, Supplementary Figure 5) and likely reflects the inflation remaining due to the polygenic signal at many independent loci, including those not yet significantly associated.

To confirm that the observed inflation is primarily coming from true polygenic signal, we analyzed the data from all imputed markers using LD-score regression56. This method tests for a linear relationship between marker test statistics and LD score, defined as the sum of r2 values between a marker and all other markers within a 1-Mb window. The primary analysis results show a linear relationship between association test statistics and LD-score (Supplementary Figure 6) and estimate that the majority (88.2%) of the inflation in test statistics can be ascribed to true polygenic signal rather than population stratification or other confounders. These results are consistent with the theory of polygenic disease architecture shown previously by both simulation and real data for GWAS samples of similar size57.

Migraine subtype analyses

To elucidate pathophysiological mechanisms underpinning the migraine aura, we performed a secondary analysis by creating two subsets that included only samples with the subtypes; migraine with aura and migraine without aura. These subsets only included those studies where sufficient information was available to assign a diagnosis of either subtype according to classification criteria standardized by the International Headache Society (IHS)6. For the population-based studies this involved questionnaires, whereas for the clinic-based studies the diagnosis was assigned on the basis of a structured interview by telephone or in person. A stricter diagnosis is required for the subtypes as migraine aura is often challenging to distinguish from other neurological features that can present as symptoms from unrelated conditions.

As a result, the migraine subtype analyses consisted of considerably smaller sample sizes compared to the main analysis (6,332 cases vs. 144,883 controls for migraine with aura and 8,348 cases vs. 139,622 controls for migraine without aura, Table 1). As with the primary analysis, the test statistics for migraine with aura or migraine without aura were consistent with underlying polygenic architecture rather than other potential sources of inflation (Supplementary Figure 7–Supplementary Figure 8). For the migraine without aura subset analysis we found seven significantly associated genomic loci (near TSPAN2, TRPM8, PHACTR1, FHL5, ASTN2, near FGF6, and LRP1, Supplementary Table 11 and Supplementary Figure 9). All seven of these loci were already identified in the primary analysis, possibly reflecting the fact that migraine without aura is the most common form of migraine (around 2 in 3 cases) and likely drives these association signals in the primary analysis. Notably, no loci were associated to migraine with aura in the other subset analysis (Supplementary Figure 10).

To investigate whether excess heterogeneity could be contributing to the lack of associations in migraine with aura, we performed a heterogeneity analysis between the two subgroups (Online Methods and Supplementary Table 12). We selected the 44 LD-independent SNPs associated from the primary analysis and used a random-effects model to combine the migraine with aura and migraine without aura samples in a meta-analysis that allows for heterogeneity between the two migraine groups58. We found little heterogeneity with only seven of the 44 loci (at MEF2D, PHACTR1, near REST/SPINK2, ASTN2, PLCE1, MPPED2, and near MED14/USP9X) exhibiting signs of heterogeneity across subtype groups (Supplementary Table 13).

Credible sets of markers within each locus

For each of the 38 migraine-associated loci, we defined a credible set of markers that could plausibly be considered as causal using a Bayesian-likelihood based approach59. This method incorporates evidence from association test statistics and the LD structure between SNPs in a locus (Online Methods). A list of the credible set SNPs obtained for each locus is provided in Supplementary Table 14. We found three instances (in RNF213, PLCE1, and MRVI1) where the association signal could be credibly attributed to exonic missense polymorphisms (Supplementary Table 15). However, most of the credible markers at each locus were either intronic or intergenic, which is consistent with the theory that most variants detected by GWA studies involve regulatory effects on gene expression rather than disrupting protein structure60,61.

Overlap with eQTLs in specific tissues

To identify migraine loci that might influence gene expression, we used previously published datasets that catalog expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) in either of two microarray-based studies from peripheral venous blood (N1 = 3,754) or from human brain cortex (N2 = 550). Additionally, we used a third study based on RNAseq data from a collection of 42 tissues and three cell lines (N3 = 1,641) from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) consortium62. While this data has the advantage of a diverse tissue catalog, the number of samples per tissue is relatively small (Supplementary Table 16) compared to the two microarray datasets, possibly resulting in reduced power to detect significant eQTLs in some tissues. Using these datasets we applied a method based on the overlap of migraine and eQTL credible sets to identify eQTLs that could explain associations at the 38 migraine loci (Online Methods). This approach merged the migraine credible sets defined above with credible sets from cis-eQTL signals within a 1-Mb window and tested if the association signals between the migraine and eQTL credible sets were correlated. After adjusting for multiple testing we found no plausible eQTL associations in the peripheral blood or brain cortex data (Supplementary Tables 17–18 and Supplementary Figure 11). In GTEx, however, we found evidence for overlap from eQTLs in three tissues (Lung, Tibial Artery, and Aorta) at the HPSE2 locus and in one tissue (Thyroid) at the HEY2/NCOA7 locus (Supplementary Table 19 and Supplementary Figure 12).

In summary, from three datasets we implicate eQTL signals at only two loci (HPSE2 and HEY2). This low number (two out of 38) is consistent with previous studies which have observed that available eQTL catalogues currently lack sufficient tissue specificity and developmental diversity to provide enough power to provide meaningful biological insight53. No plausibly causal eQTLs were observed in expression data from brain.

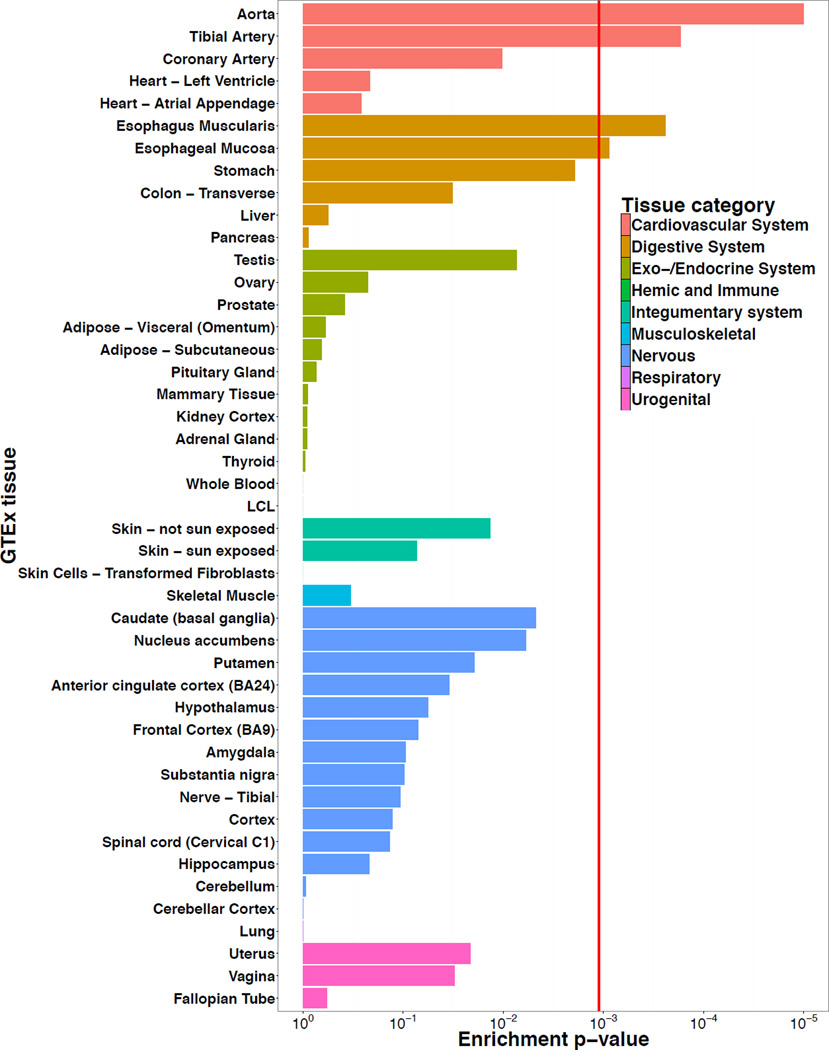

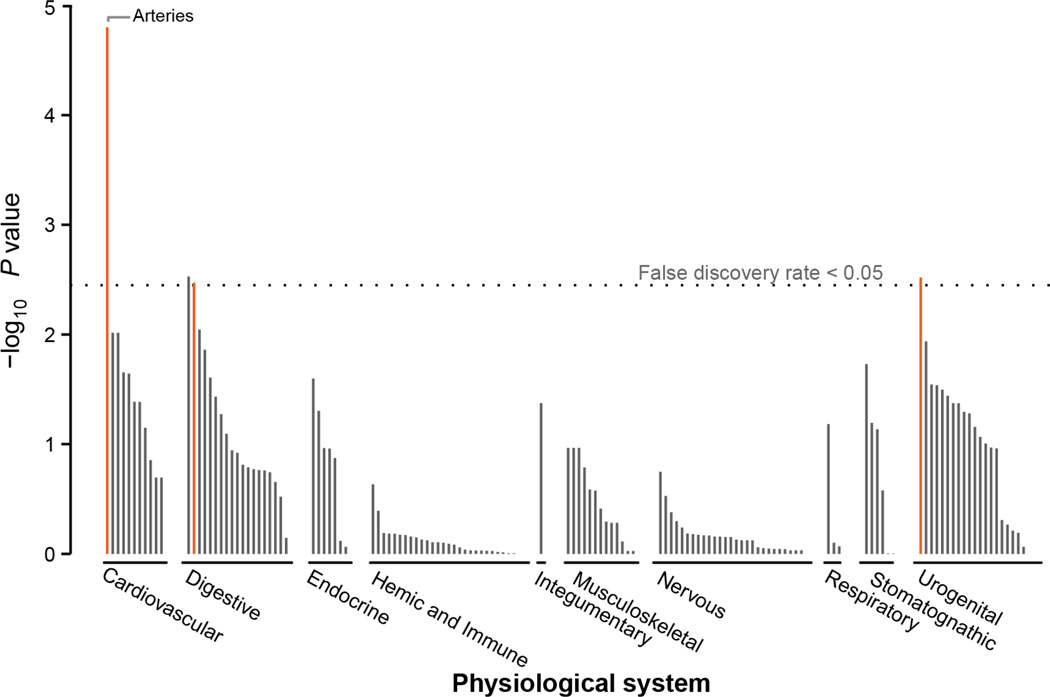

Gene expression enrichment in specific tissues

To understand if the 38 migraine loci as a group are enriched for expression in certain tissue types, we again used the GTEx pilot data62 (see Online Methods). We found four tissues that were significantly enriched (after Bonferroni correction) for expression of the migraine genes (Figure 2). The two most strongly enriched tissues were part of the cardiovascular system; the aorta and tibial artery. Two other significant tissues were from the digestive system; esophagus muscularis and esophageal mucosa. We replicated these enrichment results using the DEPICT63 tool and an independent microarray-based gene expression dataset (Online Methods). DEPICT highlighted four tissues (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 20) with significant enrichment of genes within the migraine loci; arteries (P = 1.58 × 10−5), the upper gastrointestinal tract (P = 2.97 × 10−3), myometrium (P = 3.03 × 10−3), and stomach (P = 3.38 × 10−3).

Figure 2.

Gene expression enrichment of genes from the migraine loci in GTEx tissues. Expression data from 1,641 samples was obtained using RNAseq for 42 tissues and three cell lines from the GTEx consortium. Enrichment P-values were assessed empirically for each tissue using a permutation procedure (100,000 replicates) and the red vertical line shows the significance threshold after adjusting for multiple testing by Bonferroni correction (see Online Methods).

Figure 3.

Gene expression enrichment of genes from the migraine loci in 209 tissue/cell type annotations by DEPICT. Expression data was obtained from 37,427 human microarray samples and then genes in the migraine loci were assessed for high expression in each of the annotation categories. Enrichment P-values were determined by comparing the expression pattern from the migraine loci to 500 randomly generated loci and the false discovery rate (horizontal dashed line) was estimated to control for multiple testing (see Online Methods). A full list of these enrichment results are provided in Supplementary Table 20.

Taken together, the expression analyses implicate arterial and gastrointestinal (GI) tissues. To discover if this enrichment signature could be attributed to a more specific type of smooth muscle, we examined the expression of the nearest genes at migraine loci in a panel of 60 types of human smooth muscle tissue64. Overall, migraine loci genes were not significantly enriched in a particular class of smooth muscle (Supplementary Figures 13–15). This suggests that the enrichment of migraine risk variants in genes expressed in tissues with a smooth muscle component is not specific to blood vessels, the stomach or GI tract, but rather appears to be generalizable across vascular and visceral smooth muscle types.

Combined, these enrichment results suggest that some of the genes affected by migraine-associated variants are highly expressed in vascular tissues and their dysfunction could play a role in migraine. Furthermore, the results suggest that other tissue types (e.g. smooth muscle) could also play a role and this may become evident once more migraine loci are discovered.

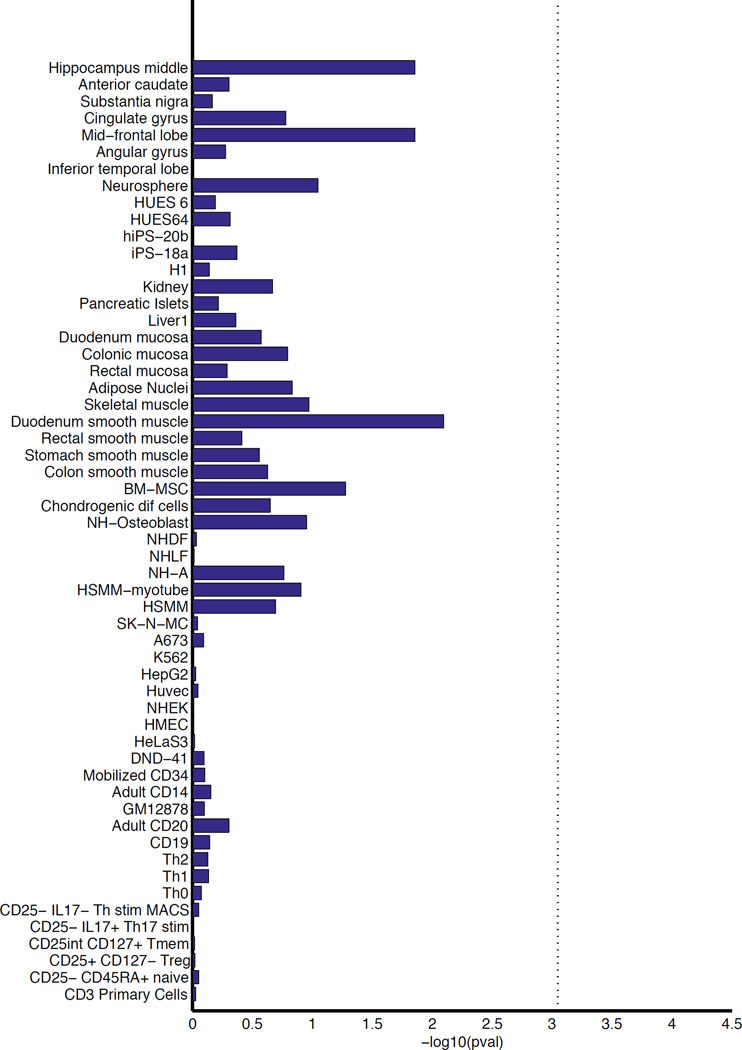

Enrichment in tissue-specific enhancers

To further assess the hypothesis that migraine variants might operate via effects on gene-regulation, we investigated the degree of overlap with histone modifications. Using candidate causal variants from the migraine loci, we examined their enrichment within cell-type specific enhancers from 56 primary human tissues and cell types from the Roadmap Epigenomics65 and ENCODE projects66 (Online Methods and Supplementary Table 21). These variants showed highest enrichment in tissues from the mid-frontal lobe and duodenum smooth muscle but were not significant after adjusting for multiple testing (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Enrichment of the migraine loci in sets of tissue-specific enhancers. We mapped credible sets from the migraine loci to sets of enhancers under active expression in 56 tissues and cell lines (identified by H3K27ac histone marks from the Roadmap Epigenomics65 and ENCODE66 projects). Enrichment P-values were assessed empirically by randomly generating a background set of matched loci for comparison (10,000 replicates) and the vertical dotted line is the significance threshold after adjusting for 56 separate tests by Bonferroni correction (see Online Methods).

Gene set enrichment analyses

To implicate underlying biological pathways involved in migraine, we applied a Gene Ontology (GO) over-representation analysis of the 38 migraine loci (Online Methods). We found nine vascular-related biological function categories that were significantly enriched after correction for multiple testing (Supplementary Table 22). Interestingly, we found little statistical support from the identified loci for some molecular processes that have been previously linked to migraine, e.g. ion homeostasis, glutamate signaling, serotonin signaling, nitric oxide signaling, and oxidative stress. However, it is possible that the lack of enrichment for these functions may be explained by recognizing that current annotations for many genes and pathways are far from comprehensive, or that larger numbers of migraine loci need to be identified before we have sensitivity to detect enrichment in these mechanisms.

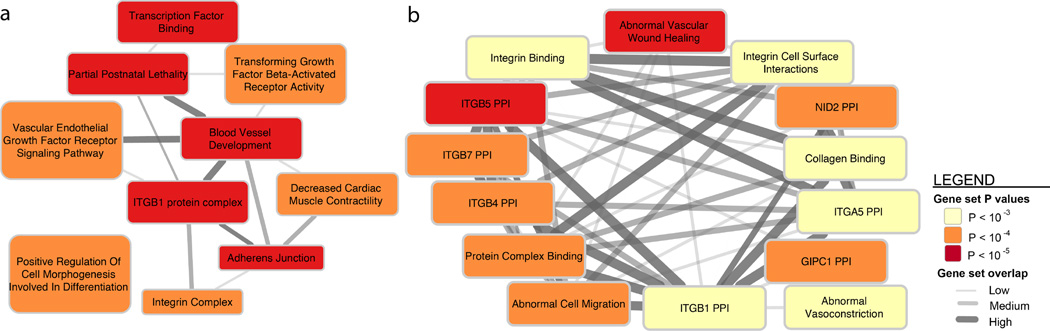

For a more comprehensive pathway analysis we used DEPICT, which incorporates gene co-expression information from microarray data to implicate additional, functionally less well-characterized genes in known biological pathways, protein-protein complexes and mouse phenotypes63 (by forming so-called ‘reconstituted gene sets’). From DEPICT we identified 67 reconstituted gene sets that are significantly enriched (FDR < 5%) for genes found among the migraine associated loci (Supplementary Table 23). Because the reconstituted gene sets had genes in common, we clustered them into 10 distinct groups (Figure 5 and Online Methods). Several gene sets, including the most significantly enriched reconstituted gene set (Abnormal Vascular Wound Healing; P = 1.86 × 10−6), were grouped into clusters related to cell-cell interactions (ITGB1 PPI, Adherens Junction, and Integrin Complex). Several of the other gene set clusters were also related to vascular-biology (Figure 5 and Supplementary Table 23). We still did not observe any support for molecular processes with hypothesized links to migraine (Supplementary Table 24), however, this could again be due to the reasons outlined above.

Figure 5.

DEPICT network of the reconstituted gene sets that were significantly enriched (false discovery rate < 0.05) for genes at the migraine loci (Online Methods). Enriched gene sets are represented as nodes with pairwise overlap denoted by the width of the connecting lines and empirical enrichment P-value is indicated by color intensity (darker is more significant). The 67 significantly enriched gene sets were clustered by similarity into 10 group nodes as shown in (a) where each group node is named after the most representative gene set in the group. (b) Shows one example of gene sets that were clustered within the now expanded ITGB1 PPI group. A full list of the 67 significantly enriched reconstituted gene sets can be found in Supplementary Table 23.

DISCUSSION

In what is the largest genetic study of migraine to date, we identified 38 distinct genomic loci harboring 44 independent susceptibility markers for the prevalent forms of migraine. We provide evidence that migraine-associated genes are involved both in arterial and smooth muscle function. Two separate analyses, the DEPICT and the GTEx gene expression enrichment analyses, point to vascular and smooth muscle tissues being involved in common variant susceptibility to migraine. The vascular finding is consistent with known co-morbidities and previously reported shared polygenic risk between migraine, stroke and cardiovascular diseases67,68. Furthermore, a recent GWA study of Cervical Artery Dissection (CeAD) identified a genome-wide significant association at the same index SNP (rs9349379 in the PHACTR1 locus) as is associated to migraine, suggesting the possibility of partially shared genetic components between migraine and CeAD26. These results suggest that vascular dysfunction and possibly also other smooth muscle dysfunction likely play roles in migraine pathogenesis.

The support for vascular and smooth muscle enrichment of the loci is strong, with multiple lines of evidence from independent methods and independent datasets. However, it remains likely that neurogenic mechanisms are also involved in migraine. For example, several lines of evidence from previous studies have pointed to such mechanisms5,69–72. We found some support for this when looking at gene expression of individual genes at the 38 loci (Supplementary Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 25), where several genes were specifically active in brain tissues. While we did not observe statistically significant enrichment in brain across all loci, it may be that more associated loci are needed to detect this. Alternatively, it could be due to difficulties in collecting appropriate brain tissue samples with enough specificity, or other technical challenges. Additionally, there is less clarity of the biological mechanisms for a neurological disease like migraine compared to some other common diseases, e.g. autoimmune or cardio-metabolic diseases where intermediate risk factors and underlying mechanisms are better understood.

Interestingly, some of the analyses highlight gastrointestinal tissues. Although migraine attacks may include gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g. nausea, vomiting, diarrhea)6 it is likely that the signals observed here broadly represent smooth muscle signals rather than gastrointestinal specificity. Smooth muscle is a predominant tissue of the intestine, yet specific smooth muscle subtypes were not available to test this hypothesis in our primary enrichment analyses. We showed instead in a range of 60 smooth muscle subtypes, that the migraine loci are expressed in many types of smooth muscle, including vascular (Supplementary Figures 14–15). These results, while not conclusive, suggest that the enrichment of the migraine loci in smooth muscle is not specific to the stomach and GI tract.

Our results implicate cellular pathways and provide an opportunity to determine whether the genomic data supports previously presented hypotheses of mechanisms linked to migraine. One prevailing hypothesis, stimulated by findings in familial hemiplegic migraine (FHM), has been that migraine is a channelopathy5,21. Among the 38 migraine loci, only two harbor known ion channels (KCNK519 and TRPM820), while three additional loci (SLC24A322, near ITPK123, and near GJA124) can be linked to ion homeostasis. This further supports the findings of previous studies that in common forms of migraine, ion channel dysfunction is not the major pathophysiological mechanism15. However, more generally, genes involved in ion homeostasis could be a component of the genetic susceptibility. Moreover, we cannot exclude that ion channels could still be important contributors in migraine with aura, the form most closely resembling FHM, as our ability to identify loci in this subgroup is more challenging. Another suggested hypothesis relates to oxidative stress and nitric oxide (NO) signaling73–75. Six genes with known links to oxidative stress and NO were identified within these 38 loci (REST45, GJA146, YAP147, PRDM1648, LRP149, and MRVI150). This is in line with previous findings11, however, the DEPICT pathway analysis observed no association between NO-related reconstituted gene sets and migraine (FDR > 0.54, Supplementary Table 24).

Notably, in the migraine subtype analyses, it was possible to identify specific loci for migraine without aura but not for migraine with aura. However, the heterogeneity analysis (Supplementary Tables 12–13) demonstrated that most of the identified loci are implicated in both migraine subtypes. This suggests that the absence of significant loci in the migraine with aura analysis is mainly due to lack of power from the reduced sample size. Additionally, as shown by the LD score analysis (Supplementary Figures 6–8), the amount of heritability captured by the migraine with aura dataset is considerably lower than migraine without aura, such that in order to reach comparable power, a sample size of two- to three-times larger would be required. This may reflect a higher degree of heterogeneity in the clinical capture, more complex underlying biology, or even a larger contribution to risk from low-frequency and rare variation for this form of the disease.

In conclusion, the 38 genomic loci identified in this study support the notion that factors in vascular and smooth muscle tissues contribute to migraine pathophysiology and that the two major subtypes of migraine, migraine with aura and migraine without aura, have a partially shared underlying genetic susceptibility profile.

ONLINE METHODS

Study design and phenotyping

A description of the study design, ascertainment and phenotyping for each GWA study is provided in the Supplementary Note.

Quality Control

The 22 individual GWA studies were subjected to pre-established quality control (QC) protocols as recommended elsewhere76,77. Differences in genotyping chips, DNA quality and calling pipelines necessitated that QC parameters were tuned separately for each study. At a minimum, we excluded markers with high missingness rates (>5%), low minor allele frequency (<1%), and failing a test of Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. We also excluded individuals with a high proportion of missing genotypes (>5%) and used identity-by-descent (IBD) estimates to remove related individuals (IBD > 0.185). A summary of the genotyping platforms, QC, and software used in each study is provided in Supplementary Table 3. To control for population stratification within each study, we merged the genotypes passing QC filters with HapMap III data from three populations; European (CEU), Asian (CHB+JPT) and African (YRI). We then performed a principal components analysis on the merged dataset and excluded any (non-European) population outliers. To control for any sub-European population structure, we performed a second principal components analysis within each study to ensure that cases and controls were clustering together. Any principal components that were significantly associated with the phenotype were included as covariates in the model when calculating test statistics for the meta-analysis (Supplementary Table 4).

Imputation

Following study-level QC, estimated haplotypes were phased for each individual using (in most instances) the program SHAPEIT78. Missing genotypes were then imputed into these haplotypes using the program IMPUTE279 and a mixed-population 1000 Genomes Project16 reference panel (March 2012, phase I, v3 release or later). A minority of contributing studies used alternative programs for phasing and imputation; BEAGLE80, MACH81, MINIMAC82, or in-house custom software. A summary of software and procedures used is provided in Supplementary Table 3.

Statistical analysis

Individual study association analyses were implemented using logistic regression with an additive model on the imputed dosage of the effect allele. All models were adjusted for sex and other relevant covariates when appropriate (Supplementary Table 4). As age information was not available for individuals from all studies we were not able to adjust for it in our models. However, we note that all of the GWA studies were comprised of adults past the typical age of onset, hence, age is at most a non-confounding factor and false positive rates would not be affected by its inclusion/exclusion. The programs used for performing the within-study association analyses were either SNPTEST, PLINK or R (URLs). The program GWAMA was then used to perform a fixed-effects meta-analysis weighted by the inverse variances to obtain a combined effect size, standard error and P-value at each marker. We excluded markers in any study that had low imputation quality scores (IMPUTE2 INFO < 0.6 or MACH r2 < 0.6) or low minor allele frequency (MAF < 0.01). Additionally, we filtered out markers that were missing from more than half of all studies (12 or more) or exhibited high heterogeneity (heterogeneity index i2 > 0.75). After filtering, 8,045,569 total markers were tested in the meta-analysis.

Chromosome X meta-analysis

Due to the different ploidy of males and females on chromosome X, we implemented a model of X-chromosome inactivation (XCI) that assumes an equal effect of alleles in both males and females. This was achieved by scaling male dosages to the range 0–2 to match that of females. In total, 57,756 cases and 299,109 controls were available for the X-chromosome analysis (Supplementary Table 1). The reduced sample size compared to the autosomal data occurred because some of the individual GWA studies (EGCUT, Rotterdam III, Twins UK, and 846 controls from GSK for the ‘German MO’ study) did not contribute chromosome X data.

LD score regression analysis

We conducted a univariate heritability analysis based on summary statistics using LD score regression (LDSC) v1.0.056. For this analysis, high-quality common SNPs were extracted from the summary statistics by filtering the data on the following criteria: presence among the HapMap Project Phase 3 SNPs83, allele matching to 1000 Genomes data, no strand ambiguity, INFO score > 0.9, MAF >= 1%, and missingness less than two thirds of the 90th percentile of the total sample size. The HLA region (chromosome 6, 25–35 Mb) was excluded from the analysis. From this data, we used LDSC to quantify the proportion of the total inflation in chi-square statistics that can be ascribed to polygenic heritability by calculating the ratio of the LDSC intercept estimate and the chi-square mean using the formula described in the original publication56.

Heterogeneity analysis of migraine subtypes

To determine if heterogeneity between the migraine subtypes might have affected our ability to identify new loci, we performed an additional meta-analysis using a subtype-differentiated approach that allows for different allelic effects between two groups58. Since a large proportion of the controls were shared in the original migraine with aura and migraine without aura datasets (Table 1), for this analysis we created two additional subsets of the migraine subtype data that contained no overlapping controls between the two new subsets (Supplementary Table 12). The new migraine with aura subset consisted of 4,837 cases and 49,174 controls and the new migraine without aura subset consisted of 4,833 cases and 106,834 controls. To assess the heterogeneity observed, we chose the 44 index SNPs from the primary meta-analysis and applied the subtype-differentiated meta-analysis method to these. We observed that only seven out of the 44 SNPs exhibited heterogeneity in the subtype-differentiated test (Heterogeneity P-value < 0.05, Supplementary Table 13) suggesting that most loci likely affect risk for both subtypes.

Defining credible sets

Within each migraine-associated locus, we defined a credible set of variants that could be considered 99% likely to contain a causal variant. The method has been introduced in detail elsewhere53,59 and is outlined again briefly here. Assume D is the data including the genotype matrix X for all of the P variants (genotype for variant j is denoted as xj) and disease status Y (for N individuals), and β is the model parameters. We define the ‘model’, denoted A, as the causal status for all of the P variants in the locus: A = {aj}, in which aj is the causal status for variant j. aj = 1 if the variant j is causal, whereas aj = 0 if it is not. We assume that there is one and only one genuine signal for each locus, therefore, one and only one of the P variants is causal: Σj aj = 1. For convenience, we define Aj as the model that only variant j is causal, and A0 as the model that no variant is causal (null model). The probability for model Aj(where variant j is the only causal variant in this locus) given the data can be calculated using Bayes’ rule:

| (1) |

We estimate Equation (1) using the steepest descent approach84. Making the assumption of a flat prior on the model parameters, we approximate the integral over the model parameters using their maximum likelihood estimator (β̂j):

| (2) |

where the sample size is denoted by N and the number of fitted parameters for model Aj is denoted by |βj|· |βj| is a constant because model Aj has the same number of parameters across all variants. In the framework of a generalized linear model, the deviance for two nested models follows an approximate chi-square distribution. We therefore define χj2 as the deviance comparing the null model and the model in which variant j is causal

| (3) |

We further show that χj2 can be calculated as the chi-square statistic of fitting a binomial model with the disease status (Y) as the dependent variable and the genotype of variant j as the explanatory variable:

| (4) |

Pr(Aj|D) in Equation (2) is then a function of the χj2:

| (5) |

where l0 = Pr (D|A0, β̂0). We make the assumption that the prior causal probability for all variants is equal, i.e., Pr(Aj) is the same across all variants j. Equation (5) can then be simplified with a constant for the term and the probability that variant j is causal can be calculated using

| (6) |

which can be normalized across all variants as

| (7) |

Finally, the 99% credible set of variants is defined as the smallest set of models, with each model designating one causal variant, S = {Aj}, such that

| (8) |

This credible set of variants has 99% probability of containing the causal variant, given the assumption that there is a true association and that all possible causal variants have been genotyped (both assumptions are likely to be valid in genome-wide significant regions of data that have been imputed to 1000 Genomes). We have made the R-script for implementing the method freely available online (URLs).

eQTL credible set overlap analysis

To assess if the association statistics in the 38 migraine loci could be explained by credible overlapping eQTL signals, we used two eQTL microarray datasets. The first consisted of 3,754 samples from peripheral venous blood85 and the second was from a meta-analysis of human brain cortex studies of 550 samples86. From both studies we obtained summary statistics from an association test of putative cis-eQTLs between all SNP-transcript pairs within a 1-Mb window of each other. Then for the most significant eQTLs (P < 1 × 10−4) found for genes within a 1Mb window of migraine credible set variants (see Defining credible sets), we created an additional credible set of markers for each eQTL. We then tested (using Spearman’s rank correlation) whether there was a significant correlation between the association test-statistics in each migraine credible set compared to the expression test-statistics in each overlapping eQTL credible set. Significant correlation between a migraine credible set and an eQTL credible set was taken as evidence of the migraine locus tagging a real eQTL. An appropriate significance threshold for multiple testing was determined by Bonferroni correction.

GTEx tissue enrichment analysis

Gene sets for each locus were obtained by taking all genes within 50kb of credible set SNPs. Identified genes were then analyzed for tissue enrichment using publicly available expression data from the pilot phase of the Genotype-Tissue Expression project (GTEx)62, version 3. In this dataset, postmortem samples from 42 human tissues and three cell lines across 1,641 samples (Supplementary Table 16) were used for bulk RNA sequencing according to a unified protocol. All samples were sequenced using Illumina 76 base-pair paired-end reads. Collapsed reads per kilobase per million mapped reads (RPKM) values for 52,577 transcripts were filtered for those with unique HGNC IDs (n = 20,932). We also excluded transcripts from any non-coding RNAs. All transcripts were ranked by mean RPKM across all samples and 100,000 permutations of each credible set gene list were generated by selecting a random transcript for each entry in the credible set within +/−100 ranks of the transcript for that gene. For each sample, the RPKM values were converted into ranks for that transcript, and sums of ranks within each tissue were computed for each gene. Enrichment P-values for each tissue were calculated by taking the total number of instances where the gene list of interest had a lower sum of ranks than the permuted sum of ranks (divided by the total number of permutations). We estimated the number of independent tissues via the matSpD tool87 and then used Bonferroni correction to adjust for 27 independent tests (P < 1.90 × 10−3).

Specificity of individual genes in GTEx tissues

We selected the nearest gene to the index SNP at each migraine locus and then investigated the individual expression activity of each of these genes. As the number of samples for some tissues was small, we grouped individual tissues into four categories; brain, vascular, gastrointestinal, and other tissues (Supplementary Table 16). For each selected gene, we then tested whether the average expression (mean RPKM) was significantly higher in a particular tissue group compared to the ‘other tissues’ category. We assessed significance using a one-tailed t-test and used Bonferroni correction to adjust for 114 tests (38 genes × 3 tissue groups). While some genes were observed to be significantly expressed in multiple tissue groups, we determined that a gene was tissue-specific if it was only expressed highly in one tissue group (i.e. brain, vascular, or gastrointestinal, Supplementary Table 25).

eQTL credible set analysis in GTEx tissues

For all tissues and transcripts (filtered as above), we identified genome-wide significant (P < 2 × 10−13) cis-eQTLs within a 1Mb window of each transcript and created credible sets (see Defining credible sets) for each eQTL locus identified in each tissue. We found a total of 35 of these significant eQTL credible sets within a 1Mb window of the migraine loci, however, only seven out of 35 contained variants that overlapped with a migraine credible set. For these seven eQTL credible sets, we then tested (Spearman’s rank correlation) if the test statistics between the two overlapping credible sets were significantly correlated. Significant correlation between a migraine credible set and an eQTL credible set was taken as evidence of the migraine locus tagging a real eQTL. Multiple testing was controlled for using Bonferroni correction (i.e. for seven tests at P < 7.1 × 10−3).

Enhancer enrichment analysis

Markers of gene regulation were defined using ChIP-seq datasets from ENCODE66 and the NIH Roadmap Epigenome65 projects. Based on the histone H3K27ac signal, which identifies active enhancers, we processed data from 56 cell lines and tissue samples to identify cell/tissue-specific enhancers, which we define as the 10% of enhancers with the highest ratio of reads in that cell/tissue type divided by the total reads88. The raw data is publicly available (URLs) and a description of the 56 tissues/cell types is provided in Supplementary Table 21. We mapped the credible set variants at each migraine locus to these enhancer sites and compared the overlap observed with tissue-specific enhancers relative to a background of 10,000 randomly selected sets of SNPs of equal size. We restricted the background selection to 1000 Genomes project variants (MAF > 1%) that also passed QC filters in the meta-analysis (i.e. to only allow the selection of SNPs that had an a priori chance of being associated). The selection procedure then involved randomly selecting genomic regions that were of equivalent length and density of enhancers as found in the original locus. Once an appropriate region was found, a set of SNPs was randomly selected to match the number of SNPs in the credible set for that locus. If the selected SNPs mapped to an equal number of enhancer sites (of any tissue type) as credible SNPs from the original locus, then these were added to the background set of SNPs for comparison. If the selected SNPs did not map to the correct number of enhancers, the selection procedure was repeated until an appropriate set was found. This procedure was repeated 10,000 times for each locus to obtain an empirical null distribution. The enrichment significance was then estimated empirically by calculating the proportion of replicates that were greater than the observed value. Finally, we used Bonferroni correction to adjust for multiple testing of 56 tissue/cell types (P < 8.9 × 10−4).

Gene Ontology enrichment analysis

The set of 38 genes that are nearest to the index SNP in each migraine locus was chosen and tested for over-representation in Gene Ontology (GO) annotations. The PANTHER89 tool (URLs) was used to perform the analysis implementing a binomial test to determine if the number of genes from the migraine test set found in each GO Pathway is likely to have occurred by chance alone. The association P-values were adjusted for the number of pathways tested by Bonferroni correction.

DEPICT reconstituted gene set enrichment analysis

DEPICT63 (Data-driven Expression Prioritized Integration for Complex Traits) is a computational tool, which, given a set of GWA study summary statistics, allows prioritization of genes in associated loci, enrichment analysis of reconstituted gene sets, and tissue enrichment analysis. DEPICT was run using 124 independent genome-wide significant SNPs as input (PLINK clumping parameters: --clump-p1 5e-8 --clump-p2 1e-5 --clump-r2 0.6 --clump-kb 250. Note, rs12845494 and rs140002913 could not be mapped). LD distance (r2 > 0.5) was used to define locus boundaries (note that this locus definition is different than used elsewhere in the text) yielding 37 autosomal loci comprising 78 genes. DEPICT was run using default settings, that is, 500 permutations for bias adjustment, 20 replications for false discovery rate estimation, normalized expression data from 77,840 Affymetrix microarrays for gene set reconstitution (see reference90), 14,461 reconstituted gene sets for gene set enrichment analysis, and testing 209 tissue/cell types assembled from 37,427 Affymetrix U133 Plus 2.0 Array samples for enrichment in tissue/cell type expression.

Post-analysis, we omitted reconstituted gene sets in which genes in the original gene set were not nominally enriched (Wilcoxon rank-sum test) because, by design, genes in the original gene set are expected to be enriched in the reconstituted gene set. Therefore, lack of enrichment complicates interpretation because the label of the reconstituted gene set may be inaccurate. Hence, the eight reconstituted gene sets were removed from the results: MP:0002089, MP:0002190, ENSG00000151577, ENSG00000168615, ENSG00000143322, ENSG00000112531, ENSG00000161021, and ENSG00000100320. We also removed an association identified for another gene set (ENSG00000056345 PPI, P = 1.7×10−4, FDR = 0.04) because it is no longer part of the Ensembl database. The Affinity Propagation tool91 was finally used to cluster related reconstituted gene sets into 10 groups (URLs).

DEPICT tissue enrichment analysis

DEPICT used data from 37,427 human microarray samples captured on the Affymetrix HGU133a2.0 platform to test if genes in the 38 migraine loci are highly expressed in 209 tissues/cell types with Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) annotations. The annotation procedure and method for normalizing expression profiles across annotations is outlined in the original publication63. The tissue/cell type enrichment analysis algorithm was conceptually identical to the gene set enrichment analysis whereby enrichment P-values were calculated empirically using 500 permutations for bias adjustment and 20 replications for false discovery rate estimation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the numerous individuals who contributed to sample collection, storage, handling, phenotyping and genotyping within each of the individual cohorts. We also thank the important contribution to research made by the study participants. We are grateful to Huiying Zhao (QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute) for helpful correspondence on the pathway analyses. We acknowledge the support and contribution of pilot data from the GTEx consortium. A list of study-specific acknowledgements can be found in the Supplementary Note.

Footnotes

URLs

1000 Genomes Project, http://www.1000genomes.org/; BEAGLE, http://faculty.washington.edu/browning/beagle/beagle.html; DEPICT, https://github.com/perslab/DEPICT; Credible set fine-mapping script, https://github.com/hailianghuang/FM-summary; GTEx, www.gtexportal.org; GWAMA, http://www.well.ox.ac.uk/gwama/; IMPUTE2, https://mathgen.stats.ox.ac.uk/impute/impute_v2.html; International Headache Genetics Consortium, http://www.headachegenetics.org/; MACH, http://www.sph.umich.edu/csg/abecasis/MACH/tour/imputation.html; matSpD, http://neurogenetics.qimrberghofer.edu.au/matSpD; MINIMAC, http://genome.sph.umich.edu/wiki/Minimac; PANTHER Gene Ontology enrichment, http://geneontology.org/page/go-enrichment-analysis; PLINK, https://www.cog-genomics.org/plink2; ProbABEL, http://www.genabel.org/packages/ProbABEL;; R, https://www.r-project.org/; Roadmap Epigenomics data, http://www.epigenomeatlas.org; SHAPEIT, http://www.shapeit.fr; SNPTEST, https://mathgen.stats.ox.ac.uk/genetics_software/snptest/snptest.html.

DATA ACCESS

All genome-wide significant and suggestive SNP associations (P < 1 × 10−5) from the meta-analysis can be obtained directly from the IHGC website (http://www.headachegenetics.org/content/datasets-and-cohorts). For access to deeper-level data please contact the data access committee (fimm-dac@helsinki.fi).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

P.G., V.An., G.W.M., M.I.K., M.Kals., R.Mäg., K.P., E.H., E.L., A.G.U., L.C., E.M., L.M., A-L.E., A.F.C., T.F.H., A.J.A., D.I.C., and D.R.N. performed the experiments. P.G., V.An., B.S.W., P.P., T.E., T.H.P., K-H.F., M.Mu., N.A.F., A.I., G.McM., L.L., S.G.G., S.St., L.Q., H.H.H.A., D.A.H., J-J.H., R.Mal., A.E.B., E.S., C.M.v.D., E.M., D.P.S., N.E., B.M.N., D.I.C., and D.R.N. performed the statistical analyses. P.G., V.An., B.S.W., P.P., T.E., T.H.P., K-H.F., E.C-L., N.A.F., A.I., G.McM., L.L., M.Kall., T.M.F., S.G.G., S.St., M.Ko., L.Q., H.H.H.A., T.L., J.W., D.A.H., S.M.R., M.F., V.Ar., M.Kau., S.V., R.Mal., M.I.K., M.Kals., R.Mäg., K.P., H.H., A.E.B., J.H., E.S., C.S., C.W., Z.C., K.H., E.L., L.M.P, A-L.E., A.F.C., T.F.H., J.K., A.J.A., O.R., M.A.I., M-R.J., D.P.S., M.W., G.D.S., N.E., M.J.D., B.M.N., J.O., D.I.C., D.R.N., and A.P. participated in data analysis/interpretation. P.G., V.An., B.S.W., T.H.P., K-H.F., E.C-L., T.K., G.M.T, M.Kall., C.R., A.H.S., G.B., M.Ko., T.L., M.S., M.G.H., M.F., V.Ar., M.Kau., S.V., R.Mal., A.C.H., P.A.F.M., N.G.M., G.W.M., H.H., A.E.B., L.F., J.H., P.H.L., C.S., C.W., Z.C., B.M-M., S.Sc., T.M., J.G.E., V.S., A.G.U., C.M.v.D., A.S., C.S.N., H.G., A-L.E., A.F.C., T.F.H., T.W., A.J.A., O.R., M-R.J., C.K., M.D.F., A.C.B., M.D., M.W., J-A.Z., B.M.N., J.O., D.I.C., D.R.N., and A.P. contributed materials/analysis tools. T.E., T.K., T.L., H.S., B.W.J.H.P., A.C.H., P.A.F.M., N.G.M., G.W.M., L.F., A.H., A.S., C.S.N., M.Mä., T.W., J.K., O.R., M.A.I., T.S., M-R.J., A.M., C.K., D.P.S., M.D.F., A.M.J.M.v.d.M., J-A.Z., D.I.B., G.D.S., K.S., N.E., B.M.N., J.O., D.I.C., D.R.N., and A.P. supervised the research. T.K., G.M.T, G.B., T.L., J.E.B., M.S., P.M.R., H.S., B.W.J.H.P., A.C.H., P.A.F.M., N.G.M., G.W.M., L.F., V.S., A.H., L.C., A.S., C.S.N., H.G., J.K., A.J.A., O.R., M.A.I., M-R.J., A.M., C.K., D.P.S., M.D., A.M.J.M.v.d.M., D.I.B., G.D.S., N.E., M.J.D., B.M.N., D.I.C., D.R.N., and A.P. conceived and designed the study. P.G., V.An., B.S.W., P.P., T.E., T.H.P., E.C-L., H.H., B.M.N., J.O., D.I.C., D.R.N., and A.P. wrote the paper. All authors contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

Thomas Werge has acted as lecturer and consultant for H. Lundbeck A/S, Valby, Denmark. Markus Schürks is a full-time employee of Bayer HealthCare, Germany. All other authors declared no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vos T, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2163–2196. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vos T, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;386:743–800. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gustavsson A, et al. Cost of disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;21:718–779. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pietrobon D, Striessnig J. Neurological diseases: Neurobiology of migraine. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2003;4:386–398. doi: 10.1038/nrn1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tfelt-Hansen PC, Koehler PJ. One hundred years of migraine research: Major clinical and scientific observations from 1910 to 2010. Headache. 2011;51:752–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2011.01892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version) Cephalalgia. 2013;33:629–808. doi: 10.1177/0333102413485658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polderman TJC, et al. Meta-analysis of the heritability of human traits based on fifty years of twin studies. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:702–709. doi: 10.1038/ng.3285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anttila V, et al. Genome-wide association study of migraine implicates a common susceptibility variant on 8q22.1. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:869–873. doi: 10.1038/ng.652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chasman DI, et al. Genome-wide association study reveals three susceptibility loci for common migraine in the general population. Nat Genet. 2011;43:695–698. doi: 10.1038/ng.856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freilinger T, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies susceptibility loci for migraine without aura. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:777–782. doi: 10.1038/ng.2307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anttila V, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies new susceptibility loci for migraine. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:912–917. doi: 10.1038/ng.2676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ophoff RA, et al. Familial hemiplegic migraine and episodic ataxia type-2 are caused by mutations in the Ca2+ channel gene CACNL1A4. Cell. 1996;87:543–552. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81373-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Fusco M, et al. Haploinsufficiency of ATP1A2 encoding the Na+/K+ pump alpha2 subunit associated with familial hemiplegic migraine type 2. Nat. Genet. 2003;33:192–196. doi: 10.1038/ng1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dichgans M, et al. Mutation in the neuronal voltage-gated sodium channel SCN1A in familial hemiplegic migraine. Lancet. 2005;366:371–377. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66786-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nyholt DR, et al. A high-density association screen of 155 ion transport genes for involvement with common migraine. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2008;17:3318–3331. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Altshuler DM, et al. An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature. 2012;491:56–65. doi: 10.1038/nature11632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chasman DI, et al. Selectivity in Genetic Association with Sub-classified Migraine in Women. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004366. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han B, Eskin E. Random-effects model aimed at discovering associations in meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011;88:586–598. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morton MJ, Abohamed A, Sivaprasadarao A, Hunter M. pH sensing in the two-pore domain K+ channel, TASK2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:16102–16106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506870102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramachandran R, et al. TRPM8 activation attenuates inflammatory responses in mouse models of colitis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013;110:7476–7481. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217431110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanna MG. Genetic neurological channelopathies. Nat. Clin. Pract. Neurol. 2006;2:252–263. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kraev A, et al. Molecular cloning of a third member of the potassium-dependent sodium-calcium exchanger gene family, NCKX3. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:23161–23172. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102314200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ismailov II, et al. A biologic function for an ‘orphan’ messenger: D-myo-inositol 3,4,5,6-tetrakisphosphate selectively blocks epithelial calcium-activated chloride channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996;93:10505–10509. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Bock M, et al. Connexin channels provide a target to manipulate brain endothelial calcium dynamics and blood-brain barrier permeability. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31:1942–1957. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kathiresan S, et al. Genome-wide association of early-onset myocardial infarction with single nucleotide polymorphisms and copy number variants. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:334–341. doi: 10.1038/ng.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Debette S, et al. Common variation in PHACTR1 is associated with susceptibility to cervical artery dissection. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:78–83. doi: 10.1038/ng.3154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Law C, et al. Clinical features in a family with an R460H mutation in transforming growth factor beta receptor 2 gene. J Med Genet. 2006;43:908–916. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.042176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bown MJ, et al. Abdominal aortic aneurysm is associated with a variant in low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011;89:619–627. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arndt AK, et al. Fine mapping of the 1p36 deletion syndrome identifies mutation of PRDM16 as a cause of cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2013;93:67–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fujimura M, et al. Genetics and Biomarkers of Moyamoya Disease: Significance of RNF213 as a Susceptibility Gene. J. stroke. 2014;16:65–72. doi: 10.5853/jos.2014.16.2.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McElhinney DB, et al. Analysis of cardiovascular phenotype and genotype-phenotype correlation in individuals with a JAG1 mutation and/or Alagille syndrome. Circulation. 2002;106:2567–2574. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000037221.45902.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bezzina CR, et al. Common variants at SCN5A–SCN10A and HEY2 are associated with Brugada syndrome, a rare disease with high risk of sudden cardiac death. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:1044–1049. doi: 10.1038/ng.2712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sinner MF, et al. Integrating genetic, transcriptional, and functional analyses to identify five novel genes for atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2014;130:1225–1235. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.009892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neale BM, et al. Genome-wide association study of advanced age-related macular degeneration identifies a role of the hepatic lipase gene (LIPC) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:7395–7400. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912019107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Desch M, et al. IRAG determines nitric oxide- and atrial natriuretic peptide-mediated smooth muscle relaxation. Cardiovasc. Res. 2010;86:496–505. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lang NN, Luksha L, Newby DE, Kublickiene K. Connexin 43 mediates endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor-induced vasodilatation in subcutaneous resistance arteries from healthy pregnant women. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007;292:H1026–H1032. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00797.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dong H, Jiang Y, Triggle CR, Li X, Lytton J. Novel role for K+-dependent Na+/Ca2+ exchangers in regulation of cytoplasmic free Ca2+ and contractility in arterial smooth muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2006;291:H1226–H1235. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00196.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamaji M, Mahmoud M, Evans IM, Zachary IC. Neuropilin 1 is essential for gastrointestinal smooth muscle contractility and motility in aged mice. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0115563. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu X, et al. Genome-wide association study in Han Chinese identifies four new susceptibility loci for coronary artery disease. Nature Genetics. 2012;44:890–894. doi: 10.1038/ng.2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hager J, et al. Genome-wide association study in a Lebanese cohort confirms PHACTR1 as a major determinant of coronary artery stenosis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38663. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.The Coronary Artery Disease (C4D) Genetics Consortium. A genome-wide association study in Europeans and South Asians identifies five new loci for coronary artery disease. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:339–344. doi: 10.1038/ng.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Donnell CJ, et al. Genome-wide association study for coronary artery calcification with follow-up in myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2011;124:2855–2864. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.974899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Porcu E, et al. A meta-analysis of thyroid-related traits reveals novel loci and gender-specific differences in the regulation of thyroid function. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003266. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Soler Artigas M, et al. Genome-wide association and large-scale follow up identifies 16 new loci influencing lung function. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:1082–1090. doi: 10.1038/ng.941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lu T, et al. REST and stress resistance in ageing and Alzheimer disease. Nature. 2014;507:448–454. doi: 10.1038/nature13163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kar R, Riquelme MA, Werner S, Jiang JX. Connexin 43 channels protect osteocytes against oxidative stress-induced cell death. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2013;28:1611–1621. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dixit D, Ghildiyal R, Anto NP, Sen E. Chaetocin-induced ROS-mediated apoptosis involves ATM-YAP1 axis and JNK-dependent inhibition of glucose metabolism. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1212. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chuikov S, Levi BP, Smith ML, Morrison SJ. Prdm16 promotes stem cell maintenance in multiple tissues, partly by regulating oxidative stress. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010;12:999–1006. doi: 10.1038/ncb2101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Castellano J, et al. Hypoxia stimulates low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 expression through hypoxia-inducible factor-1α in human vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2011;31:1411–1420. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.225490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schlossmann J, et al. Regulation of intracellular calcium by a signalling complex of IRAG, IP3 receptor and cGMP kinase Ibeta. Nature. 2000;404:197–201. doi: 10.1038/35004606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nalls MA, et al. Large-scale meta-analysis of genome-wide association data identifies six new risk loci for Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Genet. 2014;46:7989–7993. doi: 10.1038/ng.3043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lambert JC, et al. Meta-analysis of 74,046 individuals identifies 11 new susceptibility loci for Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:1452–1458. doi: 10.1038/ng.2802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ripke S, et al. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature. 2014;511:421–427. doi: 10.1038/nature13595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wood AR, et al. Defining the role of common variation in the genomic and biological architecture of adult human height. Nat. Genet. 2014;46:1173–1186. doi: 10.1038/ng.3097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Purcell S, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bulik-Sullivan BK, et al. LD Score regression distinguishes confounding from polygenicity in genome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:291–295. doi: 10.1038/ng.3211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang J, et al. Genomic inflation factors under polygenic inheritance. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2011;19:807–812. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Magi R, Lindgren CM, Morris AP. Meta-analysis of sex-specific genome-wide association studies. Genet. Epidemiol. 2010;34:846–853. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Maller JB, et al. Bayesian refinement of association signals for 14 loci in 3 common diseases. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:1294–1301. doi: 10.1038/ng.2435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nicolae DL, et al. Trait-associated SNPs are more likely to be eQTLs: Annotation to enhance discovery from GWAS. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Maurano MT, et al. Systematic Localization of Common Disease-Associated Variation in Regulatory DNA. Science. 2012;337:1190–1195. doi: 10.1126/science.1222794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.The GTEx Consortium. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:580–585. doi: 10.1038/ng.2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pers TH, et al. Biological interpretation of genome-wide association studies using predicted gene functions. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:5890. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chi JT, et al. Gene expression programs of human smooth muscle cells: Tissue-specific differentiation and prognostic significance in breast cancers. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:1770–1784. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bernstein BE, et al. The NIH Roadmap Epigenomics Mapping Consortium. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:1045–1048. doi: 10.1038/nbt1010-1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.The ENCODE Project Consortium. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489:57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Winsvold BS, et al. Genetic analysis for a shared biological basis between migraine and coronary artery disease. Neurol. Genet. 2015;1:e10. doi: 10.1212/NXG.0000000000000010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Malik R, et al. Shared genetic basis for migraine and ischemic stroke: A genome-wide analysis of common variants. Neurology. 2015;84:2132–2145. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]