Abstract

Self-reported anxiety, and potentially physiological response, to maintained inhalation of carbon dioxide (CO2) enriched air shows promise as a putative marker of panic reactivity and vulnerability. Temporal stability of response systems during low-dose, steady-state CO2 breathing challenge is lacking. Outcomes on multiple levels were measured two times, one week apart, in 93 individuals. Stability was highest during the CO2 breathing phase compared to pre-CO2 and recovery phases, with anxiety ratings, respiratory rate, skin conductance level, and heart rate demonstrating good to excellent temporal stability (ICCs ≥ 0.71). Cognitive symptoms tied to panic were somewhat less stable (ICC = 0.58) than physical symptoms (ICC = 0.74) during CO2 breathing. Escape/avoidance behaviors and DSM-5 panic attacks were not stable. Large effect sizes between task phases also were observed. Overall, results suggest good-excellent levels of temporal stability for multiple outcomes during respiratory stimulation via 7.5% CO2.

Keywords: carbon dioxide hypersensitivity, panic risk, temporal stability, reliability, subjective anxiety, respiratory rate, heart rate, skin conductance, panic attack, panic symptoms

Carbon dioxide (CO2) hypersensitivity has been studied among persons with panic disorder and other psychiatric conditions, as well as in the general population, and appears to represent a fairly well validated measure of panic reactivity and vulnerability (Battaglia, et al., 2007; Coryell, 1997; Coryell et al., 2001; Griez et al., 1990; Perna et al., 1995; Perna et al., 1999). Studies using CO2 enriched air have relied on a variety of CO2 air concentrations, generally ranging from 5% to 35% CO2. Of the concentrations used in clinical research, 35% CO2 is the most commonly used CO2 challenge intensity, likely owing to its procedural ease, wherein participants inhale one or two vital capacity breaths and their anxiety and symptomatic response pre- and post-inhalation are assessed (Amaral et al 2013). By contrast, the lower CO2 concentrations (e.g., 5%, 7.5%) allow researchers to continuously measure autonomic levels (e.g., respiratory rate, heart rate) as well as self-report of anxiety and symptomatic response, permitting the modeling of change over time.

The National Institute for Mental Health (NIMH) recently launched the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) project as part of their strategic plan to develop novel ways of classifying psychiatric disorders based on dimensions of observable behaviors and brain functions (Cuthbert & Insel, 2010, 2013; Insel & Cuthbert, 2009; Insel et al., 2010; Sanislow et al., 2010). RDoC aims to serve as a framework for new approaches to research on mental disorders using fundamental dimensions that cut across traditional disorder categories. It is hoped that these fundamental dimensions will closely align with mechanisms that underlie psychopathology at various biological and behavioral levels. The CO2 challenge fits well within the RDoC matrix as a “paradigm” under the Negative Valence Systems and provides for a number of units of analysis, including (but not limited to) physiology, behavior, neural circuits, and self-report.

Given this conceptual shift from diagnostic level phenotypes to dimensional construct measures that fall under higher order diagnoses, the need for psychometrically substantiated measures is crucial. Moreover, given that sensitivity to CO2 is hypothesized to be a biologically based trait marker of panic vulnerability (Battaglia, et al., 2007; Coryell, 1997; Coryell et al., 2001; Griez et al., 1990; Perna et al., 1995; Perna et al., 1999), it is important to determine whether this marker is consistently expressed across time. Two previous studies examined the test-retest reliability of self-reported anxiety and symptom response to inhalation of 35% CO2, but these studies relied on a small, clinical sample (Verburg et al., 1998) and a high- versus low-risk sample (Coryell & Arndt, 1999). Both studies documented reasonable reliability of symptomatic response, particularly smothering sensations, faintness, and dizziness, as well as greater reliability for anxiety rated post versus prior to 35% CO2 inhalation. Physiological and behavioral markers were not measured. Using a within-session repeated measures design, participants’ cardiac, electrodermal, and self-report of anxiety were measured in response to eight, 20 second inhalations of 20% CO2 enriched air (Forsyth, Lejuez, & Finlay, 2000). Means testing indicated no significant trial effects, reflecting stability of measures within session. Collectively these studies suggest satisfactory stability of physiology and subjective response systems to high dose CO2 enriched air. Thus, although the stability of anxiety, symptom, and physiological response to high dose CO2 has been established, a temporal stability study of low dose, steady-state CO2 breathing has not been undertaken.

The objective of the current study is to determine the test-retest reliability of self-reported anxiety and panic symptom response as well as behavioral and physiological markers during the steady-state 7.5% CO2 challenge across two time points. Study outcomes will inform future research and clinical assessments where stable markers are needed. Moderate levels of stability of subjective and symptom report is expected based on previous studies examining stability of response to higher dose CO2 concentrations (Coryell & Arndt, 1999; Forsyth, Lejuez, & Finlay, 2000; Verburg et al., 1998). Extant studies of physiological reliability suggest reasonably good temporal consistency (Forsyth, Lejuez, & Finlay, 2000; Schmidt et al., 2012). Thus, satisfactory reliability estimates also are expected for physiological outcomes.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited as part of a larger study of CO2 hypersensitivity (n=376) (Roberson-Nay et al, 2015) at two universities from either the psychology department participant pool or recruitment fliers posted on the campus. Table 1 provides demographic and panic related characteristics for the full test-retest reliability sample (n=93) as well as for each site. A power calculation conducted before the study’s start, indicated a sample size of 86 participants for reliability analysis (see Methods section for full calculation). Thus, the first, consecutive 146 participants completing Session 1 of the CO2 hypersensitivity study at Sites 1 and 2 were invited back to participate in Session 2 of the reliability study. Of the 146 participants invited back for Session 2, 93 (64%) agreed to return. We, therefore, slightly exceeded our power calculation estimation of 86 individuals for reliability analysis.

Table 1.

Demographic and panic related characteristics measured before 7.5% CO2 challenge for the full reliability sample and by study site.

| Full Sample n=93 | Site 1 n=52 | Site 2 n=41 | t/χ2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 19.9 (4.2) | 20.3 (5.2) | 19.3 (2.3) | 1.1 | 0.29 |

| Sex, % female | 52.7 | 62.7 | 48.6 | 1.7 | 0.19 |

| Self-reported Race, % | |||||

| African American | 22.0 | 30.0 | 9.1 | 5.5 | 0.14 |

| Asian | 14.6 | 12.2 | 18.2 | ||

| Caucasian | 57.3 | 51.0 | 66.7 | ||

| Other/More than one Race | 6.1 | 6.1 | 6.1 | ||

| Self-reported Ethnicity, % Hispanic | 12.8 | 9.8 | 17.1 | 1.0 | 0.32 |

| PDSS, % above screening cut-off score ≥ 8 | 14.0 | 17.6 | 8.6 | 0.94 | 0.23 |

| ASI Total Score | 18.8 (10.2) | 18.7 (9.1) | 18.9 | −0.05 | 0.96 |

PDSS=Panic Disorder Severity Scale; ASI=Anxiety Sensitivity Index.

Study participants at both sites were compensated financially or with course credit; the majority (89%) received course credit. Site 2 recruited participants based on a participant’s Anxiety Sensitivity Index (ASI; Reiss et al., 1986) score, which was completed during a pre-screening session. Participants were recruited based on ASI scores to ensure variance on this important panic and CO2 response risk factor (Blechert, Wilhelm, Meuret, Wilhelm, & Roth, 2013; Korte & Schmidt, 2012; Schmidt, Lerew, & Jackson, 1997, 1999; Schmidt, Zvolensky & Maner, 2006). Thus, Site 2 sent recruitment e-mails to approximately equivalent numbers of students scoring within each quartile of the distribution of ASI scores (Peterson & Reiss, 1992). No pre-screen ASI selection criteria was used for participants who participated for financial compensation or who participated at Site 1; Site 1 was unable to include a pre-screening ASI screen given differences in the participant pool infrastructure. Nonetheless, ASI score distributions and means/variance did not differ between sites (see Table 1). ASI scores also did not differ between participants participating for course credit versus financial compensation (t(1,89)=0.95, p =0.34, Cohen’s d=.33).

Of the 146 participants invited to return for session 2, there were no differences between participants who did and did not return to participate in Session 2 on the following measures, which were assessed at Session 1: repeated measurements of anxiety ratings, Diagnostic Symptom Questionnaire scores, and all physiological measures assessed during the three phases of the CO2 challenge, as well as the Anxiety Sensitivity Index (all p’s>0.05). The one exception was a non-significant trend (t(1,142)=0.85, p=.40, Cohen’s d=.15) for the anxiety rating measured during the attachment of the facemask while breathing room air; participants who returned to partake in Session 2 had a slightly higher mean SUDS rating (M=23.6) compared to participants who did not return (M=19.5). There also was no difference in the number of females/males (χ2=0.012, p=0.91) who did and did not return for the Session 2 assessment. Finally, rate of early termination of the CO2 challenge at Session 1 was nearly identical for those participants who agreed to return (21.5%) versus did not agree to return (21.6%) to participate in Session 2 (χ2=0.00 p=0.99). These results suggest that there were not significant differences between participants who did versus did not return to participate in the Session 2 CO2 challenge on primary study outcomes.

To maintain consistency across the test and retest sessions, all Session 2 visits were conducted in the same room as Session 1. Although efforts were made to have the same study team member complete Session 1 and Session 2 with the same test-retest reliability participant, this was not always possible. In total, however, the majority of Session 1 and Session 2 visits were completed with the same study team member (Site 1=76% and Site 2=73%). The mean time between Session 1 and Session 2 for Site 1 was 7.6 days (SD=0.83) and 7.2 days (SD=1.1) for Site 2.

Participants were excluded from study participation if they reported having currently treated asthma, a serious, unstable medical condition, or if they initiated a new antidepressant or other psychotropic medication within the past four weeks. Participants taking benzodiazepines were eligible to participate if they had not taken benzodiazepine medication for at least 48 hours prior to the day of the study. These medication exclusion criteria were included to reduce the potentially diminishing effects on physiology associated with anxiolytic medications (c.f. Biber & Alkin, 1999). All exclusionary criteria were provided in the initial recruitment materials and reassessed on the day of study participation.

CO2 Challenge Task

All participants were informed that they would begin the CO2 challenge task by breathing ambient room air through a facemask and, at some point, begin breathing 7.5% CO2 enriched air. Thus, participants were unaware of the timing of the CO2 versus ambient air exposure. Participants also were told that the task would take approximately 18 minutes to complete and that they could terminate the task at any time without penalty if they felt too anxious or uncomfortable; they were reminded of this on several occasions.

The CO2 challenge was conducted in a quiet room. During the task, participants sat in a supine position and were asked to remain as motionless as possible to reduce movement artifacts in physiological data recordings. Participants breathed through a fitted silicone facemask that covered their nose and mouth and was connected via gas-impermeable tubing to a large multi-liter bag that served as a reservoir for the 7.5% CO2 enriched air. A study team member remained in the room during the entire CO2 procedure although they sat out of the participant’s sight behind a room divider. Participants first breathed ambient air for five minutes (i.e., pre-CO2 phase). Then, the experimenter manually turned a three-way stopcock valve to switch from room-air to the CO2 enriched air, which caused the participant to breathe only the CO2 enriched air mixture. The participant breathed the 7.5% CO2 enriched air for eight minutes. This portion of the task was followed by a five-minute recovery period in which participants again breathed ambient air. At the end of the five-minute recovery, the mask was removed. To ensure that no one left the study distressed, participants were offered a diaphragmatic breathing relaxation exercise if their final anxiety rating was greater than 20 points above their pre-CO2 breathing anxiety rating.

Measures

Panic Related Self-Report Measures

Anxiety Sensitivity Index (ASI)

The ASI (Reiss et al., 1986) is a 16-item measure that assesses an individual’s tendency to fear sensations or symptoms associated with anxiety (e.g., ‘‘It scares me when I become short of breath’’) on a 5-point rating scale (0 = ‘‘Very little’’ to 4 = ‘‘Very much’’). This tendency is thought to reflect beliefs about the consequences linked to anxiety symptoms. The ASI has high internal consistency and good test–retest reliability (Peterson & Reiss, 1992).

Panic Disorder Severity Scale (PDSS)

The PDSS (Houck et al., 2002) consists of seven items rated on a 5-point scale, ranging 0 to 4, with a total score range from 0 to 28. The items assess panic frequency, distress during panic, panic related anticipatory anxiety, avoidance of situations, avoidance of physical sensations, impairment in work functioning, and impairment in social functioning. A cut-score of eight has been proposed as a useful screen of individuals with diagnosis-level panic symptoms (Shear et al., 2001). Fourteen percent of the reliability sample achieved a score of 8 or greater (see Table 1).

CO2 Reliability Outcome Measures

Anxiety Response

Anxiety ratings were measured using a visual analogue scale to index self-reported anxiety on a scale ranging from 0 (no anxiety) to 100 (extreme anxiety) (SUDS; Wolpe, 1969). This measure was administered during a resting baseline (i.e., before attachment of the facemask) and every two minutes during the three CO2 challenge phases to assess changes in anxiety.

Symptomatic Response

The Diagnostic Symptom Questionnaire (DSQ; Sanderson et al., 1989) is a 26-item self-report measure of current symptoms that assesses the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV; American Psychological Association, 1994) symptoms of panic. The first 16 items assess the presence and severity of panic-related symptoms (e.g., “trembling or shaking,” “pounding or racing heart”) using a 0–8 rating scale, and the next 10 items assess the presence and intensity of panic-related cognitions (e.g., “I feel like I might be dying,” “I need help”) using a 0–4 rating scale. Only the 13 symptoms that map onto DSM-5 panic attack criteria were used in the Physical and Cognitive symptom subscales. The DSQ was administered at four time points to assess change in symptom response from resting baseline and during each phase of the CO2 challenge. The four time points were: 1) resting baseline (i.e., before attachment of facemask and delivery of CO2), 2) attachment of facemask but before CO2 administration (i.e., pre-CO2), 3) after seven minutes of CO2 breathing, and 4) at the end of the recovery phase.

Consistent with previous research, the DSQ was used to generate a measure of DSM–5 panic attacks (e.g., Forsyth, Eifert, & Canna, 2000; Schmidt et al., 2002; Barlow, Brown, & Craske, 1994). Participants who reported four or more panic symptoms (at least one of which was cognitive) at a severity rating of 4 (moderate) or greater, as well as a self-reported sensation of panic at a severity rating of 4 or greater, were coded as having had a panic attack or panic like response during the CO2 breathing challenge (Sanderson et al., 1989). On the basis of these criteria, a categorical variable was created wherein participants were dummy coded as either 0 (negative for panic attack) or 1 (positive for panic attack).

Behavioral Escape/Avoidance

Participants were informed on several occasions that they could stop the CO2 challenge procedure at any time if they felt too anxious or distressed. Discontinuing the task early served as a measure of escape/avoidance. This outcome measure was not normally distributed, with most participants completing the full 18-minute challenge procedure at Session 1 and Session 2. For this reason, escape/avoidance was coded as a dichotomous variable (Stopped Challenge Early/Did Not Stop Challenge Early). Participants who remained in the task until the end of the recovery phase were considered task completers.

Physiological Measures

The Biopac data acquisition and analysis system was used to collect, process, and analyze all physiological data (Biopac System, Inc, Goleta, CA). This system included the AcqKnowledge software, which was used to measure and calculate all physiological indices. Mean scores for all physiological measures were aggregated across each of the three CO2 breathing challenge task phases, including pre-CO2, CO2 breathing, and recovery. This generated a mean score per phase for use in stability analyses. Each physiological measure is described below. Physiological measures were not recorded during the resting baseline phase.

Respiratory Frequency

Given the respiratory stimulating effects of CO2 enriched air, respiratory frequency (fR) was continuously measured by recording each breath using a respiratory transducer (TSD101B) and amplifier (RSP100C). The transducer is connected to a belt that is fitted around the thoracic/abdomen of the participant to measure movement in thoracic/abdominal circumference as the participant breaths in and out. After data acquisition, a band pass filter was used to remove potential artifacts before aggregating and computing CO2 challenge phase means. The frequencies for the band pass included a low frequency cutoff of 0.05 HZ and a high frequency cutoff of 1.0 Hz.

Skin Conductance Level

Skin conductance is a measure of sweat (eccrine) gland activity and skin conductance level (SCL) and changes in the SCL are thought to reflect general changes in autonomic arousal (Critchley, 2002). SCL data were collected using the EDA100C amplifier in conjunction with two disposable electrodes (EL509) with adhesive backing positioned on the medial phalanx of the index and middle fingers of the participant’s non-dominant hand. An electrode paste (GEL101) formulated with 0.5% saline added to a neutral base to create an isotonic, 0.05 molar NaCl, electrode paste was stippled onto electrodes to measure skin conductance. A low pass filter was applied using a frequency cutoff of 1Hz.

Heart Rate

Cardiac response was acquired using the ECG100C amplifier along with disposable adhesive electrodes (EL503) stippled with a small application of Signa gel (GEL100). Electrodes were attached to the participant’s right collarbone and left wrist. Heart rate was calculated as beats per minute using the raw EKG signal.

Statistical Methods

We conducted a power analysis before recruitment of reliability participants to determine the approximate number of participants (k) needed for the reliability analyses. The following statistical parameters were used to calculate power: α=.05, β=.02, n=2, ρ0 = 0.6 and ρ1 = 0.8, testing H0: ρ0 = ρ0 versus H1: ρ =ρ 1 > p0 (Shoukri, Asyali, & Donner, 2004). These parameters required a sample of 86 people with n=2 measurements.

To examine temporal stability, a two-way mixed, consistency intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) was computed where participants were treated as a random effect and time was treated as a fixed effect. An ICC was estimated for the mean of each response variable during the resting baseline (if available), pre-CO2, CO2 breathing, and recovery phase. The ICC computation calculates reliability of repeated measurements by relying on both the intra-participant (within) and inter-participant (between) variability. The ICC will be high when the intra-participant variability is low relative to the total of inter-participant and intra-participant variability. The ICC will be low when intra-participant variability is high relative to this total variability (Rouse et al., 2004). Standards for assessing the degree of temporal stability via ICC were adopted in accordance with Fleiss (1986). That is, a temporal stability coefficient less than 0.39 was considered poor, 0.4–0.59 fair, 0.6–0.75 good, and greater than 0.75 was considered excellent. To compare ICC values across phases of the CO2 challenge, overlap between the confidence intervals (CIs) of a given ICC and the point estimate of another ICC were examined. If there is overlap, the hypothesis that the two ICCs are not different cannot be rejected.

Effect size estimates also were computed to assist clinical researchers (e.g., sample size estimation). Presented effect size estimates are based on Morris and DeShon’s (2002) recommended calculations (i.e., equation 8), which is a modified version of Cohen’s d that adjusts for the correlation between the two sets of measurements. Information in Table 2 and Supplemental Table 1 also may be used to compute other effect size measures (e.g., daverage; Cumming, 2012).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and reliability estimates for physiological, subjective, panic symptom and behavioral measures.

| M (or %) | SD | 95% CI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sess1 | Sess2 | Sess1 | Sess2 | ICC | Lower | Upper | |

| Physiology | |||||||

| Respiratory Rate (breaths per minute) | |||||||

| Pre-CO2 Breathing | 15.42 | 15.00 | 3.36 | 3.03 | 0.60 | 0.38 | 0.75 |

| 7.5% CO2 Breathing | 19.00 | 18.66 | 4.10 | 4.08 | 0.71 | 0.56 | 0.82 |

| Recovery | 17.32 | 17.87 | 3.44 | 3.67 | 0.68 | 0.46 | 0.81 |

| Skin Conductance Level (μSiemens) | |||||||

| Pre-CO2 Breathing | 7.59 | 7.77 | 7.31 | 6.39 | 0.65 | 0.45 | 0.78 |

| 7.5% CO2 Breathing | 12.51 | 11.53 | 9.16 | 8.47 | 0.76 | 0.62 | 0.85 |

| Recovery | 12.38 | 12.53 | 9.38 | 9.55 | 0.72 | 0.52 | 0.83 |

| Heart Rate (beats per minute) | |||||||

| Pre-CO2 Breathing | 74.71 | 76.94 | 11.55 | 10.97 | 0.66a | 0.46 | 0.78 |

| 7.5% CO2 Breathing | 81.52 | 81.77 | 11.50 | 11.43 | 0.71a | 0.55 | 0.81 |

| Recovery | 79.64 | 80.75 | 12.13 | 14.40 | 0.40b | −0.02 | 0.65 |

| Self-reported Anxiety/Symptom Ratings | |||||||

| Subjective Units of Distress (SUDS) | |||||||

| Resting Baseline | 13.55 | 13.52 | 13.88 | 17.71 | 0.75 | 0.63 | 0.84 |

| Pre-CO2 Breathing | 24.16 | 17.53 | 18.68 | 16.80 | 0.74 | 0.57 | 0.84 |

| 7.5% CO2 Breathing | 42.74 | 33.95 | 23.70 | 21.10 | 0.77 | 0.59 | 0.87 |

| Recovery | 21.28 | 14.11 | 14.37 | 13.52 | 0.74 | 0.44 | 0.87 |

| Diagnostic Symptom Questionnaire | |||||||

| Resting Baseline | |||||||

| Cognitive Symptoms | 14.92 | 14.99 | 3.05 | 3.19 | 0.62a | 0.43 | 0.75 |

| Physical Symptoms | 3.36 | 2.43 | 6.69 | 3.71 | 0.37b | 0.05 | 0.58 |

| Total Score | 18.49 | 20.00 | 8.43 | 7.86 | 0.40b | 0.09 | 0.60 |

| Pre-CO2 phase | |||||||

| Cognitive Symptoms | 16.56 | 16.88 | 3.02 | 3.33 | 0.68 | 0.51 | 0.79 |

| Physical Symptoms | 6.48 | 4.80 | 8.23 | 6.35 | 0.61 | 0.41 | 0.74 |

| Total Score | 23.04 | 21.68 | 10.37 | 8.40 | 0.63 | 0.44 | 0.76 |

| 7.5% CO2 Breathing | |||||||

| Cognitive Symptoms | 20.90 | 19.54 | 4.71 | 3.70 | 0.58 | 0.33 | 0.74 |

| Physical Symptoms | 27.56 | 23.28 | 19.71 | 17.46 | 0.74 | 0.59 | 0.84 |

| Total Score | 48.46 | 42.82 | 23.17 | 19.99 | 0.74 | 0.58 | 0.84 |

| Recovery | |||||||

| Cognitive Symptoms | 15.51 | 15.66 | 3.96 | 3.75 | 0.64 | 0.42 | 0.77 |

| Physical Symptoms | 8.58 | 6.86 | 9.77 | 9.54 | 0.49 | 0.20 | 0.68 |

| Total Score | 24.09 | 22.53 | 12.78 | 12.25 | 0.54 | 0.26 | 0.71 |

| Panic Attack, % | 14.50 | 5.80 | 0.22§* | ||||

| Behavior | |||||||

| Escape/Avoidance from CO2, % Escape/Avoid | 21.5 | 19.4 | 0.21§* | ||||

Sess1=Session 1, Sess2=Session 2, M=mean, SD=standard deviation;

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001;

ICC value is significantly different from

ICC;

Kappa.

Results

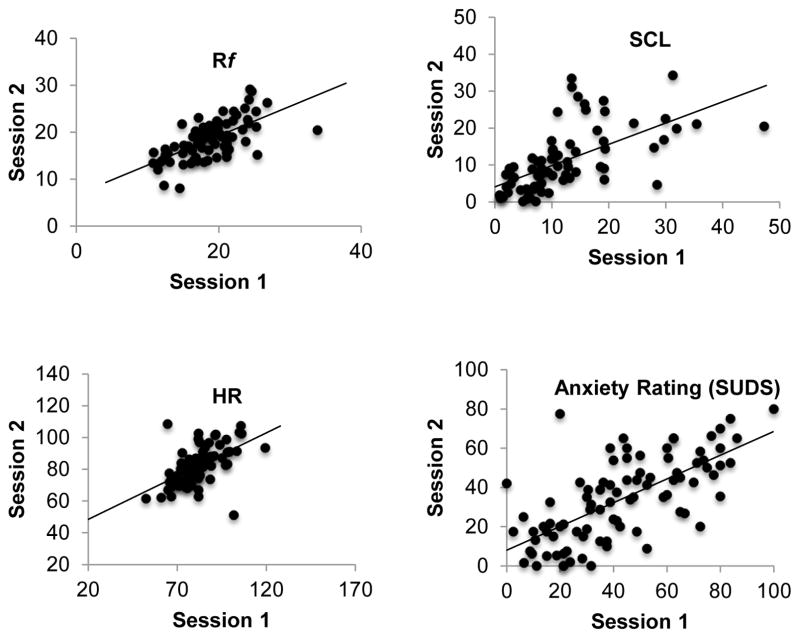

Table 1 contains means/percents, standard deviations, and ICC/kappa results for all outcomes across task phases. Table 1 results indicate that reliability was generally highest during the 7.5% CO2 breathing phase compared to all other phases (i.e., pre-CO2 and recovery). Figures 1 depicts scatterplots of physiological and anxiety ratings assessed during the 7.5% CO2 breathing phase at Session 1 and Session 2, with all measures demonstrating good to excellent reliability.

Figure 1.

Scatterplots Depicting Associations between Session 1 and Session 2 Physiological Measures and Session 1 and Session 2 Anxiety Ratings Assessed during the 7.5% CO2 Breathing Phase of the CO2 challenge. Rf=Respiratory Frequnecy; HR=Heart Rate; SCL=Skin Conductance Level.

Respiratory frequency

Rf demonstrated good stability across all phases of the CO2 breathing challenge (ICCs range 0.60–0.71), suggesting that much of the variability was caused by inter-participant variability versus intra-participant variability.

Skin Conductance Level

SC levels demonstrated good stability during the pre-CO2 phase (ICC=0.65), with stability increasing once participants were inhaling 7.5% CO2 enriched air and into the recovery phase (ICCs=0.76 and 0.72, respectively).

Heart Rate

Heart rate exhibited good stability across Session 1 and Session 2 during the baseline and into the CO2 breathing phase (ICCs=0.66 and 0.71), with significantly reduced stability observed during the recovery period (ICC=0.40).

Anxiety Response

Temporal stability of anxiety ratings ranged from good to excellent, with the highest stability observed for the CO2 breathing phase (ICC=0.77).

Symptomatic Response

Cognitive symptoms demonstrated good stability during the resting baseline, pre-CO2 breathing phase, and recovery phases (ICCs=0.62, 0.68, and 0.64 respectively), but only fair stability during CO2 breathing (ICCs=0.58). ICCs for the physical symptom subscale of the DSQ revealed a different pattern, with values fluctuating from poor to good. Good stability of physical symptoms was noted during the pre-CO2 phase (ICC=0.61), with a robust increase in stability during 7.5% CO2 breathing (ICC=0.74). Poor temporal stability was noted for the resting baseline and fair stability was observed for the recovery phase of the CO2 challenge.

DSQ symptoms also were used to define DSM-5 panic attacks. At Session 1, 14.5% of the sample met criteria for a panic attack with a sharp decline in the rate of panic attacks at Session 2 (i.e., 5.8%). Reliability of panic attacks was poor (κ =.22).

Behavioral Escape/Avoidance

Table 3 indicates the phase of the CO2 breathing challenge when escape/avoidance occurred at Session 1 and Session 2 while Table 4 provides the timing of escape/avoidance. The majority of the sample (66.7%) completed the entire breathing challenge task at Session 1 and Session 2. Of the 93 participants at Session 1, 73 (78.5%) completed the CO2 breathing challenge, with the remaining 20 (21.5%) participants terminating the task early. At Session 2, 75 (80.6%) participants completed the challenge. Stability was poor for escape/avoidance behaviors (κ=0.21).

Table 3.

Phase of 7.5% CO2 Breathing Challenge when Escape/Avoidance Occurred at Session 1 Cross-tabulated with Session 2.

| Session 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Baseline | Pre-CO2 | CO2 | Recovery | Completed | ||

|

|

||||||

| Session 1 | Baseline | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Pre-CO2 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| CO2 | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.1) | 5 (5.4) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (10.8) | |

| Recovery | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.2) | |

| Completed | 3 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (7.5) | 1 (1.1) | 62 (66.7) | |

Baseline=resting baseline before attachment of facemask, Pre-CO2=facemask with ambient air breathing, CO2=facemask with 7.5% CO2 enriched air breathing, Recovery=facemask with ambient air breathing; Completed=did not stop 7.5% CO2 breathing challenge early.

Table 4.

Minute of escape/avoidance from CO2 challenge by session.

| Session 1 | Session 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| Frequency | Percent | Cumulative Percent | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative Percent | |||

| Minute of CO2 Breathing Challenge | Baseline | ------ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4.3 | 4.3 |

| Pre-CO2 | Minute 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.3 | |

| Pre-CO2 | Minute 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.3 | |

| Pre-CO2 | Minute 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.1 | 5.4 | |

| 7.5% CO2 | Minute 6 | 8 | 8.6 | 8.6 | 5 | 5.4 | 10.8 | |

| 7.5% CO2 | Minute 8 | 2 | 2.2 | 10.8 | 5 | 5.4 | 16.1 | |

| 7.5% CO2 | Minute 10 | 4 | 4.3 | 15.1 | 1 | 1.1 | 17.2 | |

| 7.5% CO2 | Minute 12 | 3 | 3.2 | 18.3 | 1 | 1.1 | 18.3 | |

| Recovery | Minute 14 | 1 | 1.1 | 19.4 | 0 | 0 | 18.3 | |

| Recovery | Minute 16 | 2 | 2.2 | 21.5 | 1 | 1.1 | 19.4 | |

| Recovery | Minute 18 | 73 | 78.5 | 100 | 75 | 80.6 | 100 | |

Baseline=before attachment of facemask, Pre-CO2=facemask with ambient air breathing, CO2=facemask with 7.5% CO2 enriched air breathing, Recovery=facemask with ambient air breathing; Completed=did not stop 7.5% CO2 breathing challenge early.

As a secondary analysis, time of the participant’s last anxiety rating was used as a proxy of time to escape/avoid CO2 enriched air breathing. The ICC for this measure suggested fair reliability (ICC=.41).

Effect Size Estimations

Effect sizes for repeated measures designs are presented in Table 5. Effect sizes represent a contrast between the 7.5% CO2 breathing phase and all other phases; effects were generally in the large range (i.e., >0.80; Cohen, 1988). For SUDS ratings, the largest magnitude difference occurred between the 7.5% CO2 breathing phase and resting baseline (d=1.44) followed by the recovery phase (d=1.31). Self-reported panic symptoms (physical, cognitive, and total symptom scores) followed a similar pattern, with the 7.5% CO2 breathing phase versus resting baseline effect size yielding the largest effects (d=1.50–5.56). By contrast, physiological measures yielded the largest effects between the pre-CO2 and 7.5% CO2 breathing phase, with small to medium effect sizes emerging for the 7.5% CO2 breathing phase versus the recovery phase contrast (d= 0.06–0.51).

Table 5.

Effect size estimates reflecting the magnitude of effect of the 7.5% CO2 breathing phase versus the resting baseline (where measured), pre-CO2, and recovery phases.

| Effect Size (d) | ||

|---|---|---|

| SUDS | Baseline | 1.44 |

| Pre-CO2 | 0.96 | |

| Rec | 1.31 | |

|

| ||

| SCL | Pre-CO2 | 1.41 |

| Rec | 0.06 | |

|

| ||

| HR | Pre-CO2 | 0.96 |

| Rec | 0.25 | |

|

| ||

| RR | Pre-CO2 | 0.89 |

| Rec | 0.51 | |

|

| ||

| DSQ Phy | Baseline | 5.56 |

| Pre-CO2 | 2.81 | |

| Rec | 1.15 | |

|

| ||

| DSQ Cog | Baseline | 1.5 |

| Pre-CO2 | 0.99 | |

| Rec | 1.11 | |

|

| ||

| DSQ Tot | Baseline | 1.79 |

| Pre-CO2 | 1.32 | |

| Rec | 1.20 | |

SUDS=Subjective Units of Distress, SCL=Skin Conductance Level, HR=Heart Rate, RR=Respiratory Rate, DSQ=Diagnostic Symptom Questionnaire

Discussion

The present study examined the stability of self-reported anxiety and panic symptoms, physiological responses, panic attacks, and escape/avoidance behaviors to maintained inhalation of 7.5% CO2 enriched air, administered twice over an approximate one week time period. Although there currently is no clear consensus regarding which outcome measure is the gold standard for response to CO2, marked anxiety post-CO2 inhalation has the most support as a putative trait marker (Coryell et al., 2001; Vickers et al., 2011). When examining the temporal stability of repeated anxiety ratings assessed every two minutes before, during, and after CO2 inhalation, ICCs indicated good to excellent reliability, with high stability occurring during CO2 breathing. Although SCL is not considered a traditional marker of sensitivity to breathing CO2 enriched air, a few studies have examined this measure during CO2 challenge (Forsyth, Lejuez, & Finaly, 2000; Blechert et al 2010). In the current study, stability of SCL approached excellence during the CO2 breathing and recovery phases. Moreover, SCL was nearly as stable as anxiety ratings. The significant reliability observed for SCL is consistent with twin studies, which indicate considerable evidence for genetic influences (Lykken, lacono, Haroian, McGue, & Bouchard, 1988). Overall, anxiety ratings and physiological reactivity demonstrated robust stability to provocation via 7.5% CO2 enriched air, suggesting that much of the variance over time was due to inter-participant variability versus intra-participant variability.

Stability measures of self-reported symptomatic response suggested an interesting pattern in which cognitive symptoms exhibited their lowest stability during CO2 breathing, while physical symptoms exhibited their highest stability during CO2 breathing. This pattern suggests that perceived change in autonomic-related, versus cognitive, response is more reliably expressed during exposure to a panicogenic stimulus. Panic symptoms also were used to determine presence of panic attacks, where poor reliability was found for this dichotomous outcome. The escape/avoidance measure also proved to be unstable. As a secondary analysis of escape/avoidance behaviors, we used the time of the participant’s last reported anxiety rating as a proxy for time spent in the CO2 breathing task. Although a higher reliability estimate was observed with the quasi-continuous (versus dichotomous) measure, the estimate fell in the lower bounds of the “fair” reliability range, again suggesting that behavior was a weak marker of response to CO2 challenge. In all, our results of anxiety, panic symptoms, and physiological reactivity measured in a non-clinical sample are consistent with past studies investigating stability of subjective and symptomatic response to high dose CO2 in an at-risk sample (Coryell & Arndt, 1999) and a clinical sample (Verburg et al., 1998) as well as subjective and physiological reaction in a non-clinical sample (Forsyth, Lejuez, & Finlay, 2000).

It is important to note that a number of putative neuropsychobiological mechanisms likely impacted the current temporal stability results. For example, factors associated with fear learning processes may have influenced reliability outcomes. Indeed, the reduced stability of the escape/avoidance measure may be associated with two different learning related processes including habituation and sensitization (Forsyth, Lejuez, & Finlay, 2000; Blechert, et al., 2010). Consistent with habituation learning, a number of participants were able to endure the 7.5% CO2 breathing challenge for a longer duration at Session 2 compared to Session 1, thereby exhibiting between-session habituation. By contrast, a small subgroup of participants who participated in the CO2 breathing challenge at Session 1 either completely avoided the breathing challenge at Session 2 by terminating during the baseline (i.e., before attachment of facemask) or they escaped from the task early. For these participants, fear conditioning may have occurred at Session 1 such that the experience of aversive panic related symptoms during the CO2 challenge produced fear of the breathing task (Beckers et al., 2013, Lissek et al., 2005; Vervliet & Raes, 2013). Despite these factors, many of the measured markers demonstrated convincing temporal stability, which may be suggestive of strong genetic influences (Battaglia, et al., 2007; Bellodi, et al., 1998).

Session 1 data were used to estimate effect sizes between the 7.5% CO2 breathing phase versus the resting baseline, pre-CO2, and recovery phases. Effect size estimates for self-reported anxiety and panic symptoms indicated the largest effects occurring between the 7.5% CO2 breathing phase and resting baseline, although effect sizes also fell in the large range when comparing the 7.5% CO2 breathing phase and the pre-CO2 and recovery phases. By contrast, effect size estimates for physiological measures were large when comparing the 7.5% CO2 breathing phase to the pre-CO2 phase, with small to medium effects observed between the 7.5% CO2 breathing and recovery phase. The diminished effect sizes for post-CO2 challenge physiological measures reflects the enduring biological influence of CO2 enriched air after its discontinuation, with physiological markers not recovering as quickly as self-reported anxiety/distress and symptom report. Overall, effect size estimates show that the low-dose, steady-state 7.5% CO2 challenge protocol generates strong effects across multiple response systems. These outcomes have significant clinical utility and may be useful to researchers to determine sample size requirements for detecting change in intervention studies or for other research needs.

Limitations and Conclusion

The present findings should be evaluated in light of several limitations. First, this study relied on a sample of mostly young adults. Although our results support the use of the CO2 breathing challenge to study panic reactivity and risk, replication in a general population sample is needed. Second, temporal stability may be decreased in clinical populations due to disease progression or symptom fluctuation (Duff, 2012). Thus, future research with affected samples is needed to assess whether the current task and measures have acceptable stability in affected persons. Related, although this study measured panic symptomatology using a self-report measure (Panic Disorder Severity Scale; see Table 1), a clinician administered diagnostic assessment is preferred to verify history of panic attacks. Third, this study also included a non-traditional physiological measure of response to CO2 enriched air breathing (i.e., skin conductance level [SCL]). It should be noted that measurement of SCL might not be as informative without considering the skin conductance response (SCR; Boucsein, 2012), which is generally measured in response to a discrete stimulus. Thus, averaging across the whole signal may be somewhat inadequate as a measure of SCL. Related, this study did not examine several traditional physiological measures of panicogenic response to CO2 (e.g., tidal volumes, end-tidal CO2).

Overall, the 7.5% CO2 breathing challenge demonstrated robust temporal stability across a number of indices, which has important implications for treatment and longitudinal research. Measures with poor temporal stability have limited ability to detect reliable and true score changes; therefore, a stable and valid measure is fundamental to detect clinically meaningful changes associated with development or intervention (Leon, 2008). Moreover, effect size estimates indicate that the 7.5% CO2 breathing challenge has application as a measure of treatment response in clinical trials in which panic reactivity and pathophysiology are the targets. Thus, although additional refinement of markers is needed, the current results bolster extant data supporting the CO2 challenge as an endophenotypic marker of panic risk.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Self-rated anxiety and panic symptoms were most stable during CO2 breathing

Physiology was most stable during respiratory stimulation via 7.5% CO2

Physical versus cognitive symptoms showed higher stability during CO2 breathing

Escape/avoidance behaviors and panic attacks demonstrated poor reliability.

Strong effect size estimates were observed for 7.5% CO2 breathing.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by an NIMH K01MH080953 (RRN) and an NIMH R34MH106770 grant and Templeton Science of Prospection Award (BAT).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Roxann Roberson-Nay, Virginia Commonwealth University.

Eugenia I. Gorlin, University of Virginia

Jessica R. Beadel, University of Virginia

Therese Cash, Virginia Commonwealth University.

Scott Vrana, Virginia Commonwealth University.

Bethany A. Teachman, University of Virginia

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia M, Ogliari A, Harris J, Spatola CA, Pesenti-Gritti P, Reichborn-Kjennerud T, … Tambs K. A genetic study of the acute anxious response to carbon dioxide stimulation in man. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2007;41(11):906–917. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.12.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellodi L, Perna G, Caldirola D, Arancio C, Bertani A, Di Bella D. CO2-induced panic attacks: a twin study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155:1184–1188. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.9.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biber B, Alkln T. Panic disorder subtypes: Differential responses to CO2 challenge. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156(5):739–744. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.5.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biopac Systems, Inc. Electrodermal Response. n.d Retrieved from https://www.biopac.com/wp-content/uploads/app187.pdf.

- Blechert J, Wilhelm FH, Meuret AE, Wilhelm EM, Roth WT. Experiential, autonomic, and respiratory correlates of CO2 reactivity in individuals with high and low anxiety sensitivity. Psychiatry Research. 2013;209(3):566–73. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucsein W. Electrodermal activity. Springer Science & Business Media; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cannon TD, Keller MC. Endophenotypes in the genetic analyses of mental disorders. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2006;2:267–290. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Coryell W. Hypersensitivity to carbon dioxide as a disease-specific trait marker. Biological Psychiatry. 1997;41(3):259–263. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(97)87457-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3223(97)87457-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coryell W, Arndt S. The 35% CO2 inhalation procedure: Test–retest reliability. Biological Psychiatry. 1999;45(7):923–927. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(98)00241-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coryell W, Fyer A, Pine D, Martinez J, Arndt S. Aberrant respiratory sensitivity to CO2 as a trait of familial panic disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;49(7):582–587. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01089-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3223(00)01089-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critchley HD. Electrodermal Responses: What Happens in the Brain. Neuroscientist. 2002;8(2):132–142. doi: 10.1177/107385840200800209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbert B, Insel T. The data of diagnosis: New approaches to psychiatric classification. Psychiatry. 2010;73(4):311–314. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2010.73.4.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbert BN, Insel TR. Toward the future of psychiatric diagnosis: The seven pillars of RDoC. BMC Medicine. 2013;11:126-7015-11-126. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleiss JL. Reliability of measurement. The Design and Analysis of Clinical Experiments. 1986:1–32. doi: 10.1002/9781118032923. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth JP, Eifert GH, Canna MA. Evoking analogue subtypes of panic attacks in a nonclinical population using carbon dioxide-enriched air. Behavior Research and Therapy. 2000;38(6):559–572. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00074-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00074-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould TD, Gottesman II. Psychiatric endophenotypes and the development of valid animal models. Genes, Brain and Behavior. 2006;5(2):113–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2005.00186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griez E, de Loof C, Pols H, Zandbergen J, Lousberg H. Specific sensitivity of patients with panic attacks to carbon dioxide inhalation. Psychiatry Research. 1990;31(2):193–199. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(90)90121-k. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(90)90121-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houck PR, Spiegel DA, Shear MK, Rucci P. Reliability of the self-report version of the panic disorder severity scale. Depression and Anxiety. 2002;15(4):183–5. doi: 10.1002/da.10049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel TR, Cuthbert BN. Endophenotypes: Bridging genomic complexity and disorder heterogeneity. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;66(11):988–989. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel T, Cuthbert B, Garvey M, Heinssen R, Pine DS, Quinn K, … Wang P. Research domain criteria (RDoC): Toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167(7):748–51. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09091379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korte KJ, Schmidt NB. Differential prediction of C0-challenge response as a function of the taxon and complement classes of anxiety sensitivity. Depression and Anxiety. 2012;29(5):444–448. doi: 10.1002/da.20922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lykken DT, lacono WG, Haroian K, McGue M, Bouchard TJ. Habituation of the skin conductance response to strong stimuli: A twin study. Psychophysiology. 1988;25:4–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1988.tb00949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Kurtz JE, Yamagata S, Terracciano A. Internal consistency, retest reliability, and their implications for personality scale validity. Personality and SocialPsychology Review : An Official Journal of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc. 2011;15(1):28–50. doi: 10.1177/1088868310366253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination as a transdiagnostic factor in depression and anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2011;49(3):186–193. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris SB, DeShon RP. Combining effect size estimates in meta-analysis with repeated measures and independent-groups designs. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(1):105–125. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.105. http://dx.doi.org.proxy.library.vcu.edu/10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öhman A, Mineka S. Fears, phobias, and preparedness: Toward an evolved module of fear and fear learning. Psychological Review. 2001;108(3):483. doi: 10.1037//0033-295X.108.3.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perna G, Cocchi S, Allevi L, Bussi R, Bellodi L. A long-term prospective evaluation of first-degree relatives of panic patients who underwent the 35% CO2 challenge. Biological Psychiatry. 1999;45(3):365–367. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00030-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3223(98)00030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perna G, Cocchi S, Bertani A, Arancio C, Bellodi L. Sensitivity to 3 5% CO2 in healthy first-degree relatives of patients with panic disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;1(52):623. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.4.623. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/ajp.152.4.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss S, Peterson RA, Gursky DM, McNally RJ. Anxiety sensitivity, anxiety frequency and the prediction of fearfulness. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1986;24(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(86)90143-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(86)90143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberson-Nay R, Beadel JR, Gorlin EI, Latendresse SJ, Teachman BA. Examining the latent class structure of CO2 hypersensitivity using time course trajectories of panic response systems. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2015;47:68–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2014.10.013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2014.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouse MW, Borsting EJ, Lynn Mitchell G, Scheiman M, Cotter SA, Cooper J, … Wensveen J. Validity and reliability of the revised convergence insufficiency symptom survey in adults. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics. 2004;24(5):384–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2004.00202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson WC, Rapee RM, Barlow DH. The influence of an illusion of control on panic attacks induced via inhalation of 5.5% carbon dioxide-enriched air. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1989;46(2):157–162. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810020059010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanislow CA, Pine DS, Quinn KJ, Kozak MJ, Garvey MA, Heinssen RK, … Cuthbert BN. Developing constructs for psychopathology research: Research domain criteria. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119(4):631. doi: 10.1037/a0020909. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0020909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt NB, Lerew DR, Jackson RJ. The role of anxiety sensitivity in the pathogenesis of panic: Prospective evaluation of spontaneous panic attacks during acute stress. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106(3):355–364. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.3.355. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.106.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt NB, Lerew DR, Jackson RJ. Prospective evaluation of anxiety sensitivity in the pathogenesis of panic: Replication and extension. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1999;108(3):532–537. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.3.532. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.108.3.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt NB, Zvolensky MJ, Maner JK. Anxiety sensitivity: Prospective prediction of panic attacks and axis I pathology. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2006;40(8):691–699. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.07.009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt NB, Miller J, Lerew D, Woolaway-Bickel K, Fitzpatrick K. Imaginal provocation of panic in patients with panic disorder. Behavior Therapy. 2002;33(1):149–162. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(02)80010-7. [Google Scholar]

- Shear MK, Rucci P, Williams J, Frank E, Grochocinski V, Vander Bilt J, Houck P, Wang T. Reliability and validity of the Panic Disorder Severity Scale: replication and extension. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2001;35(5):293–296. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(01)00028-0. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3956(01)00028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verburg K, de Leeuw M, Pols H, Griez E. No dynamic lung function abnormalities in panic disorder patients. Biological Psychiatry. 1997;41(7):834–836. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(96)00520-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickers K, Jafarpour S, Mofidi A, Rafat B, Woznica A. The 35% carbon dioxide test in stress and panic research: Overview of effects and integration of findings. Clinical Psychology Review. 2012;32(3):153–164. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.12.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolpe J. The practice of behavior therapy. 2. New York: Pergamon Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.