Abstract

Objective

THRIVE (Kypri et al., 2009; 2013; 2014), a very brief, freely-available, multi-component web-based alcohol intervention originally developed and tested among students in Australia and New Zealand, was tested in the United States. We also evaluated effects of systematically varying the protective behavioral strategies (PBS) component of the intervention to include shorter, focused lists of Direct (e.g., alternating alcoholic with non-alcoholic drinks) or Indirect (e.g., looking out for friends) strategies.

Method

Undergraduates with past-month heavy drinking (N=208) were randomized to education/assessment Control or 1 of 3 US-THRIVE variants including Direct PBS only, Indirect PBS only, or Full (Direct and Indirect PBS).

Results

After 1 month, compared to the Control condition, Full condition participants reported fewer drinks per week (rate ratio [RR]=.62) and lower peak drinking (RR=.74). The Indirect-only condition reported reduced peak drinking (RR=.74) and a trend toward fewer drinks per week (RR=.78). Changes in drinking relative to Control were significant through 6 months for the Full and Indirect-only conditions. There were no significant differences between the Direct-only and Control conditions. US-THRIVE was not associated with decreased heavy drinking or alcohol-related problems relative to Control.

Conclusions

To our knowledge this was the first study to systematically vary the types of PBS provided in an intervention. Initial results suggest US-THRIVE is efficacious. Compared to Control, presenting Indirect PBS only as part of US-THRIVE was associated with lower drinks per week and peak past 30-day drinking. Targeting Indirect PBS may be more appropriate for non-treatment-seeking young adults receiving a brief intervention.

Keywords: brief intervention, computer-based, THRIVE, web-based, young adult

Almost 40% of full-time undergraduates report past-month heavy episodic drinking (≥5 drinks on an occasion for males; ≥4 for females) and rates are higher in students than non-student peers (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2015). Heavy drinking is related to consequences like auto accidents and fights (Jackson, Sher, & Park, 2005). Thus, heavy drinking by college students is a public health issue for which efficacious interventions are needed.

College students often have low motivation to change drinking behavior, making brief motivational interventions appropriate (Martens, Smith, & Murphy, 2013). Brief interventions contribute to significant decreases in college drinking up to 12 months post-intervention, though effects tend to be small (Carey, Scott-Sheldon, Elliott, Garey, & Carey, 2012).

Only about 50% of U.S. colleges provide empirically-supported alcohol interventions (Nelson, Toomey, Lenk, Erickson, & Winters, 2010). Making efficacious interventions available by computer that are free/low in cost and very brief will help to address poor dissemination (American Public Health Association, 2008). Two recent reviews comparing the efficacy of face-to-face with computer-based interventions found comparable results for short-term outcomes and small-effect advantages for face-to-face at longer-term follow-ups (Cadigan, Haeny, Martens, Weaver, Takamatsu, & Arterberry, 2015; Carey et al., 2012). Advantages for in-person interventions must, however, be considered in light of their added time and financial costs (Carey et al., 2012; Nelson et al., 2010). Web-based interventions are computer-based and require no participant/researcher contact, making them particularly convenient and private, though lack of direct contact raises concerns (e.g., participant distraction). Early evidence suggests web-based interventions are efficacious for young adults (Leeman, Perez, Nogueira, & DeMartini, 2015). A recent study found advantages for in-lab computer-based over web-based, but this comparison included only standalone personalized normative feedback interventions (Rodriguez et al., 2015).

One web-based intervention with efficacy in college drinkers is Tertiary Health Research Intervention via Email (THRIVE), developed for and tested among students in Australia and New Zealand (Kypri et al., 2009; 2013; 2014). Uniquely, the development of THRIVE incorporated literature review, focus groups and usability testing that aimed to distill brief intervention down to as few components as possible that had evidence of efficacy and rated highly for their usability by participants (Hallett, Maycock, Kypri, Howat, & McManus, 2009). These components include personalized feedback on drinking patterns; protective behavioral strategies (PBS) and non-judgmental language (Carey et al., 2012). As a result, THRIVE is very brief (9 minutes to complete, on average). THRIVE also has a strong evidence base from multiple large randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) (Kypri et al., 2009; 2013; 2014) yielding reductions in alcohol use with effect sizes comparable to longer interventions (Carey et al., 2012; Tanner-Smith & Lipsey, 2015). Notably, THRIVE is also available for free. Other web-based alcohol interventions for college students, namely eCHECKUP TO GO (e-CHUG), are empirically supported (e.g., Hustad, Barnett, Borsari, & Jackson, 2010). However, e-CHUG, for instance, requires 20-30 minutes (www.echeckuptogo.com/usa), contains a combination of empirically-supported and non-supported elements (Reid & Carey, 2015) and requires colleges to pay a fee for its use. Despite THRIVE's advantages, it has not yet been tested in U.S. students.

A recent integrated data analysis (IDA) suggested that effects of interventions for college drinking may be even smaller than previously thought (Huh et al., 2015), thus efforts to enhance efficacy are important. This IDA also showed that interventions including both standardized (delivered the same way to all students) and personalized information should make their messages brief, focused and straightforward. When these interventions included a high number of components, they were actually associated with increased drinking (Ray et al., 2014).

Knowledge of the most efficacious components is needed so that interventions can be focused accordingly. Information about which components are most efficacious could also be relevant to other types of interventions (e.g., campus messaging campaigns) and for guidance to clinicians regarding which topics to focus on with college drinkers. A recent review identified several promising intervention components with some supporting evidence (Reid & Carey, 2015). However, the same review yielded consistent evidence across studies for only 1 intervention component (i.e., descriptive norms comparing students with same-age peers; Reid & Carey, 2015). Thus, novel ways of delivering the more promising components are needed.

Use of PBS (cognitive-behavioral techniques to limit alcohol use and consequences; Martens et al., 2013) has been linked to less alcohol involvement in survey research (e.g., Pearson, D'Lima, & Kelley, 2013), but PBS-focused interventions have had mixed results. Multi-component interventions emphasizing PBS have led to significant reductions in alcohol use (e.g., Larimer et al., 2007; Weaver, Leffingwell, Lombardi, Claborn, Miller, & Martens, 2014), but interventions focused solely on PBS have not (LaBrie, Napper, Grimaldi, Kenney, & Lac, 2015; Martens et al., 2013; Sugarman & Carey, 2009). PBS may need to be presented among other intervention components to be efficacious, though long and varied lists of 21-32 strategies in the standalone PBS trials may have also contributed to lack of success. Short, focused PBS sets may be best suited to students’ limited retention of intervention content (Jouriles et al., 2010) and dovetail with a goal of making interventions brief and straightforward.

Further, different types of PBS may not be equally effective or easy to implement. Survey findings (DeMartini et al., 2013) support differentiating PBS directly related to drinking behaviors (e.g., alternating alcoholic and non-alcoholic drinks) from PBS focused on indirectly related, ancillary behaviors (e.g., carry protection for sexual encounters). To our knowledge, DeMartini et al. was the first to draw this distinction. Studies that have demonstrated mediation of positive intervention effects by PBS use (e.g., Larimer et al., 2007) have combined Direct with Indirect PBS. While Direct PBS have value in alcohol use reduction, young adults report using Indirect more frequently than Direct PBS (DeMartini et al., 2013), suggesting Indirect PBS may be easier to implement or more acceptable. Direct PBS may require more intensive intervention to increase their use, making them perhaps less well suited to very brief web-based interventions. If so, provision of this material may hamper efficacy given that mismatches between individuals and intervention content have been linked to negative outcomes (Karno & Longabaugh, 2007).

This initial randomized, controlled trial had 2 main goals: 1) test the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of a U.S. adaptation of THRIVE; and 2) compare with a Control condition the efficacy of variants containing a) the full set of PBS from the Australian version, including Direct and Indirect PBS; b) Direct PBS only and; c) Indirect PBS only. We predicted significant differences from Control for the Full and Indirect, but not the Direct-only variant. To our knowledge, this was the first study to systematically vary types of PBS provided to participants.

Method

Study Objectives and Design

Data collection occurred between October 2012 and May 2014. Participant recruitment occurred over 3 weeks, beginning in early October, 1 month after the start of the academic year. This process occurred over 2 consecutive academic years. Written informed consent was waived. Participants read the consent online and indicated consent by checking a box. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and a Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained.

Participants were randomized to 1 of 4 conditions, 3 of which were variants of US-THRIVE: 1) US-THRIVE with all PBS from the Australian version (including Direct + Indirect PBS) (i.e., Full condition); 2) US-THRIVE with Direct PBS only (i.e., Direct condition); 3) US-THRIVE with Indirect PBS only (i.e., Indirect condition); and 4) a Control condition consisting of the same assessments in US-THRIVE and a short electronic brochure including epidemiologic data and information about alcohol as a risk factor for injury and disease (i.e., Control condition). Participants completed online follow-up assessments 1- and 6-months after baseline/intervention.

Participants

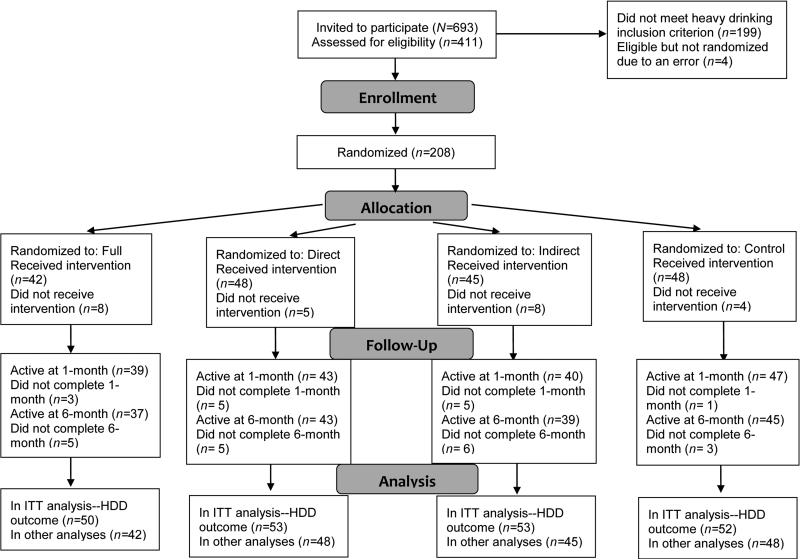

All full-time students ages 18-24 (N=693) at a small, Northeastern Catholic liberal arts college were invited to participate via an email including a link to a short web-screen, completed by 59.3% of students (Figure 1). Of these, 51.6% reported at least 1 past-month heavy drinking day and were therefore eligible. Randomization was stratified by gender and first-year or upper class standing in blocks of 4 in each strata. Twenty-five randomized students never accessed the baseline questionnaire and intervention. Their only available data for an intent-to-treat analysis was past-30-day heavy episodic drinking. Other than this analysis, the analyzable sample included 183 participants who completed the baseline questionnaire and accessed their study condition (Table 1). Of these, 92.3% were retained after 1 month and 89.6% after 6 months. Compensation was up to $100 in electronic gift cards ($10 for the web-screen, $25 for baseline questionnaire/intervention and each follow-up with a $5 bonus for completing in 3 days).

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) Diagram

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Randomized Sample (N = 208)

| Characteristics | Overall |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 19.85 (1.43) |

| Gender, No. female (%) | 130 (62.5%) |

| Race/ethnicity (available only for those who completed baseline, n = 183) | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 110 (60.1%) |

| White, Hispanic | 4 (2.2%) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 27 (14.8%) |

| Black, Hispanic | 3 (1.6%) |

| Mixed race | 8 (4.4%) |

| Other | 9 (4.9%) |

| Did not report | 22 (12%) |

| Academic class, No. (%) | |

| First-year | 51 (24.5%) |

| Sophomore | 66 (31.7%) |

| Junior | 38 (18.3%) |

| Senior | 53 (25.5%) |

| Alcohol use during the past 30 days | |

| Overall drinks per week, mean (SD) | 7.43 (7.92) |

| Drinking days per week, mean (SD) | 1.53 (1.18) |

| Heavy episodic drinking frequency past 30 days, mean (SD) | 4.78 (5.21) |

| Peak number of drinks in a day, mean (SD) | 6.36 (3.40) |

| Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index (RAPI) score, mean (SD) | 3.87 (4.16) |

| Protective Behavioral Strategy (PBS) Use | |

| Direct PBS use (0 to 6 scale: higher = greater strategy use), mean (SD) | 2.43 (1.48) |

| Indirect PBS use (0 to 6 scale: higher = greater strategy use), mean (SD) | 4.75 (1.70) |

| Motivation to Change Drinking | |

| Motivation to reduce drinking (1 to 7 scale), mean (SD) | 2.15 (1.64) |

| Motivation to stop drinking (1 to 7 scale), mean (SD) | 1.97 (1.64) |

Interventions

THRIVE contains questions that contribute to personalized feedback regarding patterns of alcohol consumption, which is generated automatically by the program. The feedback includes 4 components: alcohol dependence risk; estimated monetary cost of alcohol consumed; peak past 30-day estimated blood alcohol concentration (BAC); and 2 graphs comparing students’ self-reported drinks per drinking day and drinks per week to normative drinking levels by sex and age group (18-20 or 21-24). In addition to personalized feedback, THRIVE provides PBS, facts about alcohol, and information about local resources for reducing drinking.

Files for THRIVE were obtained from the original investigators. THRIVE was adapted for U.S. college students by changing language to be more consistent with American students’ jargon; substituting U.S. normative drinking data; changing standard drink units and relevant laws to localized alcohol information; and switching resources to those available at the college.

PBS were presented with a short title (e.g., “slow down”) and 2-4 sentence descriptions. The full set of PBS from the original THRIVE was made up of 9 strategies including all those in the focused sets of Direct and Indirect PBS. Wording was kept as close as possible to the original other than changing to American jargon to enable replication of the Australian results. Focused PBS sets were based on factor analyses of the Protective Strategies Questionnaire (PSQ; DeMartini et al., 2013; Palmer, 2004). The 4 strategies that loaded best onto a Direct factor and the 4 best-loading Indirect items became the focused strategy sets. Direct strategies were: count the number of drinks; set a drink limit and stick to it; slow down and space drinks out; and alternate alcoholic with non-alcoholic drinks. Indirect strategies were: look out for your friends and them for you; carry protection for sexual encounters; pre-plan a ride home; and secure a designated driver and ensure he/she does not drink alcohol.

Measures

Frequency/Quantity of Alcohol Use

An abbreviated Daily Drinking Questionnaire-Revised (DDQ-R; Kruse, Corbin, & Fromme, 2005) covered the prior 4 weeks. The DDQ-R asks participants to report the number of times they have consumed any alcohol on each day of the week and then to report the number of drinks they have typically had on each day of the week.

Peak drinking

Participants reported the largest number of alcoholic drinks they consumed on a single occasion in the past 4 weeks.

Alcohol-related problems

The Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (White & Labouvie, 1989) includes 23 problem items (α = 0.87). Each problem participants endorsed experiencing at least once in the past month was scored “1” with individual items added to yield a total score.

PBS use

The PSQ (DeMartini et al., 2013; Palmer, 2004) measures frequency of alcohol-related PBS use on a 7-point scale. The PSQ has been used with young adults in several studies (e.g., Palmer, McMahon, Rounsaville, & Ball, 2010). Means were calculated for the 4 items in the Direct strategy set (α = 0.80) and the 4 items in the Indirect strategy set (α = 0.90).

Interest in changing drinking behavior

On separate 7-point scales, participants reported their interest in cutting down and stopping drinking

Statistical Analyses

Primary outcomes were overall drinks per week; frequency of drinking days and PBS use. Secondary outcomes were peak number of drinks; heavy episodic drinking frequency and alcohol-related problems. Similar to Kypri et al. (2009), we first fit models including baseline and 1-month follow-up only, then a second set of models adding 6-month follow-up. PSQ scores (PBS use) were analyzed using linear mixed models. Other outcomes were treated as counts using negative binomial regression, which produces a relative difference measure called a rate ratio (RR). Analyses were planned to compare each US-THRIVE variant with the Control condition. Given this was an initial study in a line of research, there was no expectation of sufficient power for comparisons among US-THRIVE variants. All models included main effects of condition, time and condition by time interactions. Main effects and interactions involving gender and motivation to change were considered but dropped for non-significance. All available data were analyzed using maximum likelihood estimation. Intervention material was accessed by 96% of participants, but data were analyzed regardless of whether the materials were viewed.

Results

Participants

The majority of participants were female and White, non-Hispanic, with all academic classes represented. On average, the sample reported about 1 heavy drinking day per week, over 6 drinks on their peak day, about 7.5 total drinks per week and just under 4 alcohol-related problems in the past month. Drinking levels were somewhat lower among those randomized to the Control condition. The Full, Direct and Indirect conditions each reported significantly higher baseline peak number of drinks in the past 30 days compared to Control (Full: RR= 1.28, 95% CI: 1.06-1.52; Direct: RR= 1.25, 95% CI: 1.01-1.54; Indirect: RR= 1.20, 95% CI: 1.01-1.43). No other differences among study conditions at baseline were statistically significant. Note that all subsequent statistical models included baseline drinking. Motivation to change was low (Table 1). There were no significant differences between those retained and not retained at each time-point.

1-Month Follow-up Results

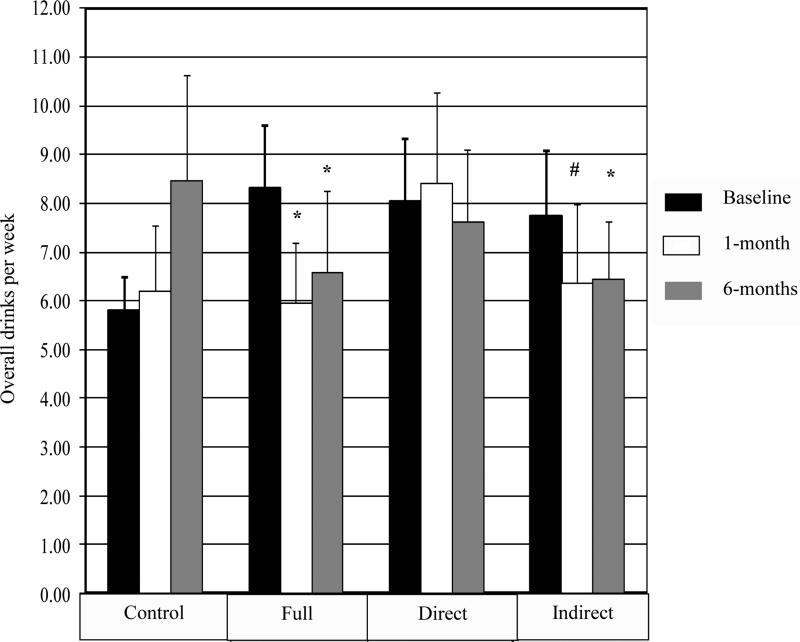

Regarding primary outcomes, there was a significant condition by time interaction for drinks per week in the Full condition compared to Control (RR= .62, 95% CI: .41-.95) with a non-significant trend in the same direction for the Indirect condition (RR=.78, 95% CI: .55-1.10). The Direct condition did not differ significantly from Control (Figure 2). There were no significant differences from Control for frequency of drinking days or PBS use (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Overall Drinks per Week in the Past 30 Days by Time and Study Condition

Table 2.

Alcohol Outcome Variables by Study Condition

| Outcome | Study Condition |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Full (including Direct + Indirect) | Direct only | Indirect only | |

| Overall drinks per week | ||||

| Baseline | 5.79 (4.84) | 8.30 (8.26) | 8.03 (9.04) | 7.75 (8.91) |

| 1-month | 6.19 (9.10) | 5.95 (7.64) | 8.42 (12.3) | 6.36 (10.22) |

| 6-month | 8.47 (14.49) | 6.59 (10) | 7.61 (9.68) | 6.43 (7.41) |

| Frequency of drinking days per week | ||||

| Baseline | 1.54 (1.13) | 1.52 (1.04) | 1.67 (1.42) | 1.38 (1.08) |

| 1-month | 1.21 (1.16) | 1.24 (0.92) | 1.56 (1.48) | 1.26 (1.19) |

| 6-month | 1.61 (1.49) | 1.29 (1.00) | 1.60 (1.38) | 1.37 (1.34) |

| Heavy episodic drinking frequency, past 30 days | ||||

| Baseline | 5.83 (6.74) | 4.32 (4.75) | 4.98 (5.26) | 3.98 (3.53) |

| 1-month | 3.40 (4.51) | 3.05 (3.38) | 3.93 (5.03) | 2.60 (3.16) |

| 6-month | 4.50 (6.21) | 3.14 (2.92) | 3.71 (3.92) | 3.97 (3.94) |

| Peak number of drinks in a day, past 30 days | ||||

| Baseline | 5.40 (2.16) | 6.93 (3.68) | 6.73 (4.32) | 6.49 (2.97) |

| 1-month | 5.45 (4.15) | 5.26 (4.38) | 5.95 (4.74) | 4.83 (4.42) |

| 6-month | 6.07 (5.48) | 5.73 (4.85) | 6.33 (6.12) | 5.31 (4.03) |

| RAPI score | ||||

| Baseline | 3.81 (3.18) | 4.05 (4.51) | 4.06 (4.76) | 3.58 (4.23) |

| 1-month | 4.08 (4.26) | 4.15 (5) | 3.37 (4.42) | 2.79 (3.88) |

| 6-month | 3.53 (4.58) | 2.97 (4.12) | 3.63 (4.65) | 3.93 (4.92) |

| Direct PBS use | ||||

| Baseline | 2.32 (1.46) | 2.54 (1.37) | 2.67 (1.64) | 2.23 (1.44) |

| 1-month | 2.69 (1.55) | 2.95 (1.54) | 2.62 (1.83) | 2.34 (1.71) |

| 6-month | 2.99 (1.79) | 2.61 (1.73) | 2.44 (1.70) | 2.26 (1.73) |

| Indirect PBS use | ||||

| Baseline | 4.53 (1.95) | 5.12 (1.20) | 4.71 (1.72) | 4.69 (1.79) |

| 1-month | 4.85 (1.66) | 4.8 (1.47) | 4.67 (1.96) | 4.47 (2.12) |

| 6-month | 4.73 (1.6) | 4.48 (1.88) | 4.57 (1.9) | 4.31 (2.09) |

Note. RAPI = Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index, PBS = protective behavioral strategies. All available data analyzed using maximum likelihood estimation. Sample sizes for model predicting heavy episodic drinking frequency: Control condition (n=50), Full condition (n=53), Direct condition (n=53), Indirect condition (n=52). Sample sizes for all other models: Control condition (n=42), Full condition (n=48), Direct condition (n=45), Indirect condition (n=48).

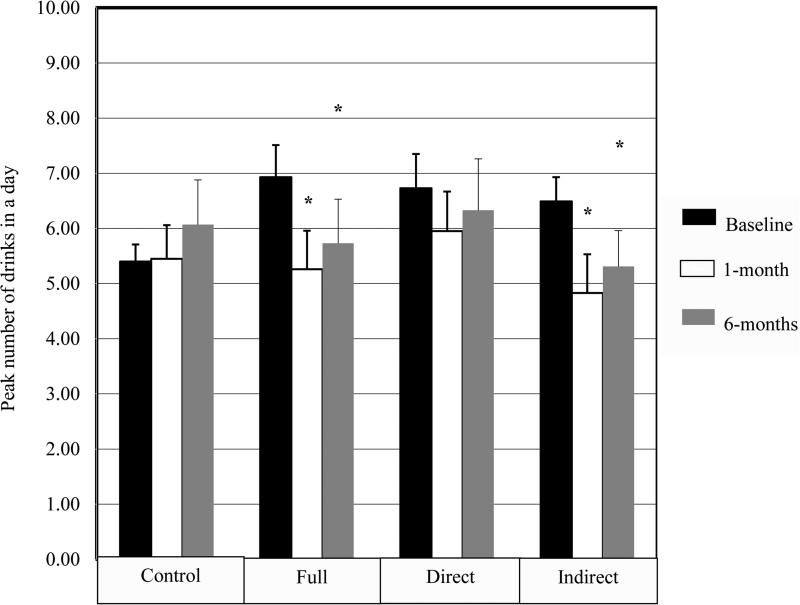

Regarding secondary outcomes, there was a significant condition by time interaction for peak number of drinks in the past 30-days in the Full (RR=.74, 95% CI: .55-.98) and Indirect Conditions (RR=.74, 95% CI: .56-.97), relative to the Control condition. The Direct condition did not differ from Control (Figure 3). There were no significant differences between Control and Intervention conditions for heavy episodic drinking or alcohol-related problems (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Peak Number of Drinks in a Day in Past 30 Days by Time and Study Condition

6-Month Follow-up Results

Though drinks per week increased somewhat from 1- to 6-month follow-up in the Full condition, a significant condition by time interaction remained such that Control condition participants increased to a greater extent (RR= 0.49, 95% CI: 0.28-0.83). The condition by time interaction from baseline to 6 months was also significant for the Indirect condition relative to Control (RR= 0.59, 95% CI: 0.37-0.93), with drinks per week remaining relatively consistent from 1- to 6-month follow-up in the Indirect condition. Direct did not differ significantly from the Control condition from baseline to 6 months (Figure 2). Frequency of drinking days and PBS use (Table 2) did not differ significantly between any Intervention condition and Controls.

Peak number of drinks increased by about 1/2 drink in all conditions from 1 to 6-month follow-up. In the Full and Indirect conditions, peak number of drinks still differed significantly from Control (Full: RR=.72, 95% CI: .52-.98; Indirect: RR=.74, 95% CI: .55-.98). The Direct condition did not differ significantly from Control (Figure 3). Heavy drinking and related problems (Table 2) did not differ between Intervention and Control at 6-month follow-up.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this was the first study to systematically vary the types of PBS presented as part of an alcohol intervention. The Full version, designed to replicate the original THRIVE results, including both Direct and Indirect PBS, was associated with significant decreases in overall weekly and peak drinking after 1 month. Notably, significant results were maintained after 6 months. Compared to the Control condition, the version of US-THRIVE presenting only Indirect PBS had stronger results than the version presenting only Direct. At 1 month, the Indirect condition had a significantly greater decrease in peak drinking and a trend-level decrease in drinks per week compared to Control. At the 6 month follow-up, the change in drinking for both outcomes differed significantly between the Indirect PBS and Control conditions. In contrast, the condition providing Direct PBS only was not associated with significantly greater decreases in any outcome compared to Control. The findings in the Indirect condition support the benefits of a shorter, focused approach to presenting PBS among other intervention components as opposed to prior studies that presented longer lists of PBS as a standalone intervention (LaBrie et al., 2015; Martens et al., 2013; Sugarman & Carey, 2009).

Baseline drinks per week and peak drinking were lower in the Control compared to the intervention conditions, which raises concerns about the possibility that observed changes were due to factors other than intervention effects. However, even in the Control condition, baseline drinking was high enough to enable observation of decreased drinking at follow-up and regression to the mean should affect all treatment conditions in a similar fashion. The three active conditions had similar baseline levels but, in accordance with our predictions, drinking in the Direct condition did not decrease compared to Control; whereas the Full and Indirect conditions did. These patterns suggest changes in the Full and Indirect conditions compared to the Control condition were due to intervention effects, not floor effects or regression to the mean.

Changes in outcomes with US-THRIVE were at least comparable to prior THRIVE findings and the literature broadly (Leeman et al., 2015). Kypri et al. (2009)—the only THRIVE trial that included short-term outcomes—reported significant decreases in drinking compared to control for 3 of 7 outcomes with a RR of .83 for drinks per week after 1 month. We found significant decreases compared to control for 2 of 7 outcomes and RRs of .62 and .78 for drinks per week in the Full and Indirect conditions, respectively (the closer a RR is to 1, the smaller the effect). The small-to-medium effect short-term reductions in drinking in this study compare favorably to face-to-face and computer-based brief interventions, which had small short-term effects (d=.19 and .14, respectively) on drinks per week in a recent meta-analysis (Carey et al., 2012). Notably, most of these interventions require considerably more time than US-THRIVE.

Peak and heavy drinking increased between the 1- and 6-month follow-ups. Though peak drinking increased somewhat between the 1- and 6-month follow-ups in the Full and Indirect conditions, there was a net increase from baseline in the Control condition. Thus, the Full and Indirect conditions may have helped to mitigate a pattern of increased peak drinking over time. This pattern of increased drinking may have been due to the time of year when the 6-month follow-up occurred. In future larger studies, half the sample could begin in the fall semester with the other half beginning in the spring. This staggered approach was not possible in this initial study. Booster interventions may help to sustain reductions in peak drinking in a future study.

Decrement in effects is common in brief intervention studies as the effects for drinks per week in the aforementioned meta-analysis declined to where they no longer differed significantly from zero at longer-term follow-up (Carey et al., 2012). Furthermore, effects of in-person brief interventions tend to last longer than web-based (Cadigan et al., 2014; Carey et al., 2012). Thus, we would not necessarily expect this very brief web-based intervention to have effects lasting for an extended period (e.g., over 1 year). However, the added duration of effects for in-person interventions must be considered in the context of the costs of administration (e.g., trained, qualified intervention providers; dedicated space; coordination of scheduling and rescheduling). In the long run, it may turn out to be more cost-effective to administer more than one web-based brief intervention spaced several months apart, rather than a single in-person intervention.

In light of the specific content of this research, results suggest that while Direct PBS are valuable, Indirect PBS may be better suited to very brief, web-based intervention. Though Indirect PBS such as securing a designated driver require planning, they may be easier to implement without additional counseling. In contrast, Direct PBS, such as slowing the pace of drinking, may be difficult for a heavy drinker who is compelled to drink for reasons such as positive expectancies and craving (Jackson et al., 2005). Future, larger studies could test moderator variables to ascertain which factors adversely affect drinkers’ ability to use Direct PBS. Heavy drinking young adults may require intensive intervention to slow their pace of drinking. Given present results and prior findings, a primary focus on Indirect PBS may be appropriate for other forms of very brief/brief intervention as well (e.g., campus-wide messaging campaigns) though this would need to be established in future studies.

Self-reported Indirect PBS use has been related to fewer alcohol-related consequences (e.g., DeMartini et al., 2013), but a predicted decrease in alcohol-related problems was not observed for any intervention condition relative to control. Other very brief, web interventions have also yielded null findings for consequences (Leeman et al., 2015). The 1-month window for self-reported problems in this study may have been too short to observe intervention effects. It is also possible that the measure of alcohol-related problems was not sensitive to decreases in specific consequences related to use of Indirect PBS. In addition, the alcohol-related problems measure in the present study does not include subscales assessing specific types of problems, like drinking and driving or risky sexual behavior, which were specific targets of Indirect PBS. Thus, future studies should assess specific consequences that relate to the PBS that are targeted. In sum, a short, focused set of Indirect PBS was associated with reduced alcohol use. However, in addition to more sensitive measurement, further enhancement of the presentation of PBS in very brief, web interventions may be needed to yield evidence of decreased negative consequences.

This study also provided no evidence of increased frequency of PBS use. This may have been due to the limited number of PBS addressed in the Direct and Indirect PBS conditions or measurement limitations. More sensitive, multi-faceted assessment of PBS may be needed to detect intervention effects, including more frequent assessment of PBS use to enhance accuracy; scales more sensitive than 7-point Likert scales (Braitman, 2012); and measurement of related constructs along with frequency of PBS use. Self-efficacy to use PBS has been linked to less alcohol use in survey research (Bonar et al., 2011). Presentation of Indirect PBS, which are likely easier to implement than Direct, may lead to enhanced self-efficacy to use PBS and, in turn, reductions in drinking, but this possibility will need to be addressed in future studies.

While the present results were promising, this study had limitations. The sample size was small, particularly considering that participants were randomized to 1 of 4 conditions. Also, the sample came entirely from a small liberal arts college with lower baseline drinking than most college alcohol brief intervention studies including the original THRIVE trials (Kypri et al., 2009; 2013; 2014). The sample had a high proportion of women, though this is typical of college brief intervention studies (Carey et al., 2012; Leeman et al., 2015) and evidence suggests that computer-based interventions may actually be less efficacious for women (Carey et al., 2012);

In conclusion, results of this study demonstrate that US-THRIVE can lead to reductions in drinking and suggest potential value of emphasizing Indirect over Direct strategies. Moreover, the availability of THRIVE at no cost to colleges could increase access to web-based preventive interventions. While promising, a larger trial is indicated to replicate and extend these results.

Public Health Significance Statement.

THRIVE (Kypri et al., 2009; 2013; 2014) has the potential to make a public health impact as an alcohol reduction intervention due to its brevity, web-based administration, evidence base, inclusion of multiple efficacious components, and free availability. Results from this initial study demonstrate evidence of efficacy for a version tailored to US college students (US-THRIVE) and suggest the potential value of emphasizing in brief interventions indirect protective behavioral strategies ancillary to drinking itself (e.g., watching out for your friends and them for you) rather than Direct strategies concerning manner of drinking.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by ABMRF/the Foundation for Alcohol Research (RFL), P50 AA012870 (KSD), K05 AA014715 (SSO), and K01 AA019694 (RFL) from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and by the Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the official views of the funding agencies.

Footnotes

Dr. O'Malley has no conflicts and has been a consultant to Alkermes, Lundbeck, Pfizer, and GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. O'Malley has had contracts as an investigator on clinical trials supported by NABI Biopharmaceuticals and Lilly and received study medication from Pfizer. She is a past partner of Applied Behavior Research and has received honorarium from the Hazelden Foundation. Dr. O'Malley has received honoraria from the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology/American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology's Alcohol Clinical Trials Initiative, which has received support from Abbott, Alkermes, Janssen, Lilly, Lundbeck, Pfizer and Schering Plough.

References

- American Public Health Association . Alcohol screening and brief intervention: A guide For public health practitioners. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation; Washington DC: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett NP, Murphy JG, Colby SM, Monti PM. Efficacy of counselor vs. computer-delivered intervention with mandated college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2529–2548. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braitman AL. The effects of personalized boosters for a computerized intervention targeting college student drinking. Old Dominion University; Norfolk, VA: 2012. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Bonar EE, Rosenberg H, Hoffmann E, Kraus SW, Kryszak E, Young KM, Bannon EE. Measuring university students’ self-efficacy to use drinking self-control strategies. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011;25:155–161. doi: 10.1037/a0022092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadigan JM, Haeny AM, Martens MP, Weaver CC, Takamatsu SK, Arterberry BJ. Personalized drinking feedback: A meta-analysis of in-person versus computer-delivered interventions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014;83:430–437. doi: 10.1037/a0038394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon LA, Elliott JC, Garey L, Carey MP. Face-to-face versus computer-delivered alcohol interventions for college drinkers: A meta-analytic review, 1998 to 2010. Clinical Psychology Review. 2012;32:690–703. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality . 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed tables. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- DeMartini KS, Palmer RS, Leeman RF, Corbin WC, Toll BA, Fucito LM, O'Malley SS. Drinking less and drinking smarter: Direct and indirect protective strategies in young adults. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27:615–626. doi: 10.1037/a0030475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallett J, Maycock B, Kypri K, Howat P, McManus A. Development of a web-based alcohol intervention for university students: Processes and challenges. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2009;28:31–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2008.00008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh D, Mun EY, Larimer ME, White HR, Ray AE, Rhew IC, Atkins DC. Brief motivational interventions for college student drinking may not be as powerful as we think: An individual participant-level data meta-analysis. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2015;39:919–931. doi: 10.1111/acer.12714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hustad JT, Barnett NP, Borsari B, Jackson KM. Web-based alcohol prevention for incoming college students: A randomized controlled trial. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, Sher KJ, Park A. Drinking among college students: Consumption and consequences. In: Galanter M, editor. Recent Developments in Alcoholism. Vol. 17. Springer; New York, NY: 2005. pp. 85–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouriles EN, Brown AS, Rosenfield D, McDonald R, Croft K, Leahy MM, Walters ST. Improving the effectiveness of computer-delivered personalized drinking feedback for college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:592–599. doi: 10.1037/a0020830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karno MP, Longabaugh R. Does matching matter? Examining matches and mismatches between patient attributes and therapy techniques in alcoholism treatment. Addiction. 2007;102:587–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse M, Corbin W, Fromme K. Improving accuracy of QF measures of alcohol use: Disaggregating quantity and frequency; Poster presented at the 28th annual meeting of the Research Society on Alcoholism; Santa Barbara, CA. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kulesza M, McVay MA, Larimer ME, Copeland AL. A randomized clinical trial comparing the efficacy of two active conditions of a brief intervention for heavy college drinkers. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38:2094–2101. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kypri K, Hallett J, Howat P, McManus A, Maycock B, Bowe S, Horton NJ. Randomized controlled trial of proactive web-based alcohol screening and brief intervention for university students. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2009;169:1508–1514. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kypri K, McCambridge J, Vater T, Bowe SJ, Saunders JB, Cunningham JA, Horton NJ. Web-based alcohol intervention for Māori University students: Double-blind, multi-site randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2013;108:331–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04067.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kypri K, Vater T, Bowe SJ, Saunders JB, Cunningham JA, Horton NJ, McCambridge J. Web-based alcohol screening and brief intervention for university students: A randomized trial. JAMA. 2014;311:1218–1224. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Napper LE, Grimaldi EM, Kenney SR, Lac A. The Efficacy of a Standalone Protective Behavioral Strategies Intervention for Students Accessing Mental Health Services. Prevention Science. 2015;16:663–673. doi: 10.1007/s11121-015-0549-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Lee CM, Kilmer JR, Fabiano P, Stark C, Geisner IM, Mallett K, Lostutter TW, Cronce JM, Freeney M, Neighbors C. Personalized mailed feedback for drinking prevention among college students: One year outcomes from a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:285–293. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman RF, Perez E, Nogueira C, DeMartini KS. Very brief, web-based interventions for reducing alcohol use and related problems among college students: A review. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2015;6:129. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00129. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Smith AE, Murphy JG. The efficacy of single-component brief motivational interventions among at-risk college drinkers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2013;81:691–701. doi: 10.1037/a0032235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills KC, Sobell MB, Schaefer HH. Training social drinking as an alternative to abstinence for alcoholics. Behavior Therapy. 1971;2:18–27. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson TF, Toomey TL, Lenk KM, Erickson DJ, Winters KC. Implementation of NIAAA college drinking task force recommendations: How are Colleges doing 6 Years Later? Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34:1687–1693. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer RS. Efficacy of the Alcohol Skills Training Program in mandated and non-mandated heavy drinking college students. University of Washington; Seattle, WA: 2004. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer RS, McMahon TJ, Rounsaville BJ, Ball SA. Coercive sexual experiences, protective behavioral strategies, alcohol expectancies and consumption among male and female college students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2010;25:1563–1578. doi: 10.1177/0886260509354581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson MR, D'Lima GM, Kelley ML. Daily use of protective behavioral strategies and alcohol-related outcomes among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27:826–831. doi: 10.1037/a0032516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray AE, Kim S-Y, White HR, Larimer ME, Mun E-Y, Clarke N, Huh D. When less is more and more is less in brief motivational interventions: Characteristics of intervention content and their associations with drinking outcomes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28:1026–1040. doi: 10.1037/a0036593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid AE, Carey KB. Interventions to reduce college student drinking: state of the evidence for mechanisms of behavior change. Clinical Psychology Review. 2015;40:213–224. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez LM, Neighbors C, Rinker DV, Lewis MA, Lazorwitz B, Gonzales RG, Larimer ME. Remote versus in-lab computer-delivered personalized normative feedback interventions for college student drinking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2015;83:455–463. doi: 10.1037/a0039030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugarman DE, Carey KB. Drink less or drink slower: the effects of instruction on alcohol consumption and drinking control strategy use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23:577–585. doi: 10.1037/a0016580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner-Smith EE, Lipsey MW. Brief alcohol interventions for adolescents and young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 51:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver CC, Leffingwell TR, Lombardi NJ, Claborn KR, Miller ME, Martens MP. A computer-based feedback only intervention with and withoutt a moderation skills componnet. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2014;46:22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1989;50:30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]