Abstract

Bladder and bowel dysfunction (BBD) describes a spectrum of lower urinary symptoms (LUTS) accompanied by fecal elimination issues that manifest primarily by constipation and/or encopresis. This increasingly common entity is a potential cause of significant physical and psychosocial burden for children and families. BBD is commonly associated with vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) and recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs), which at its extreme may lead to renal scarring and kidney failure. Additionally, BBD is frequently seen in children diagnosed with behavioural and neuropsychiatric disorders such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Patients with concomitant BBD and neuropsychiatric disorders have less favourable treatment outcomes. Early diagnosis and treatment of BBD are critical to avoid secondary comorbidities that can adversely impact children’s kidney and bladder function, and psychosocial well-being. The majority of patients will improve with urotherapy, adequate fluid intake, and constipation treatment. Pharmacological treatment must only be considered if no improvement occurs after intensive adherence to at least six months of urotherapy ± biofeedback and constipation treatment. Anticholinergics remain the mainstay of medical treatment. Selective alpha-blockers appear to be effective for improving bladder emptying in children with non-neurogenic detrusor overactivity (DO), incontinence, recurrent UTIs, and increased post-void residual (PVR) urine volumes. Alpha-1 blockers can also be used in combination with anticholinergics when overactive bladder (OAB) coexists with functional bladder outlet obstruction. Minimally invasive treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA bladder injections, and recently neurostimulation, are promising alternatives for the management of BBD refractory to behavioural and pharmacological treatment.

In this review, we discuss clinical presentation, diagnostic approach, and indications for behavioural, pharmacological, and surgical treatment of BBD in children based on a thorough literature review. Expert opinion will be used when scientific evidence is unavailable.

Introduction

Bladder and bowel dysfunction (BBD) is an all too common, but likely underdiagnosed pediatric entity. BBD describes a myriad of lower urinary symptoms (LUTS), accompanied by bowel complaints, primarily constipation and/or encopresis, and represents up to 40% of pediatric urology consults.1,2

LUTS symptoms common to BBD include dysuria, urgency, urinary frequency, hesitancy, daytime incontinence, enuresis, dribbling, straining, voiding postponement, and urinary retention. Urological conditions such as overactive bladder (OAB), underactive bladder, and dysfunctional voiding can be part of BBD. Vaginal voiding and giggle incontinence are common differential diagnoses.

Embryological, anatomical, and functional interactions between bladder and bowel are well-established. In general terms, increased rectal fecal load can affect bladder emptying and/or storage by: 1) mechanical compression, resulting in decreased bladder capacity that can cause urge incontinence and frequency; and 2) changing the physiological neural stimuli of the bladder and pelvic floor muscles, leading to progressively decreased urge to evacuate, chronic bladder spasms, insufficient emptying, and significant post-void urine volumes. BBD cycle pattern is established when children who hold their bladders by choice for longer periods exhibit reduced sensation to evacuate, ultimately resulting in constipation and/or encopresis.1

BBD is a potential cause of significant physical and psychosocial burden for children and families. It is commonly associated with vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) and recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs), which ultimately may lead to renal scarring and kidney failure.1–4 BBD negatively affects children’s quality of life and self-esteeml; therefore, early diagnosis and treatment of BBD are critical to avoid secondary comorbidities that can adversely impact children’s kidney and bladder function, as well as their psychosocial well-being.

The goal of this review is to provide recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of BBD in children based on an updated, thorough discussion of relevant studies in the field and experts opinions.

Clinical presentation

Historically, the lack of standardization compromised the comparison of research studies and consequently, the development of high-quality, evidence-based clinical guidelines for diagnosis and management of pediatric BBD. To address those issues, the uniform use of new terminology provided by International Children’s Continence Society (ICCS) is highly encouraged globally.5 A variety of urological conditions recognized as part of the BBD spectrum (previously known as dysfunctional elimination syndrome or dysfunctional voiding) are listed below according to ICCS terminology.

OAB

OAB, the most common urological presentation part of BBD spectrum, is characterized by urgency and increased voiding frequency with or without incontinence. According to ICCS, the diagnosis is solely based on the aforementioned clinical findings.

Dysfunctional voiding

The term dysfunctional voiding (DV) should be applied exclusively to “children who contract the urethral sphincter during voiding.”5 DV is commonly associated with constipation and/or encopresis. Although staccato is the most common uroflow pattern seen in children with DV, an interrupted or mixed flow pattern can also be found in DV. Therefore, when trying to rule out DV, it is key to perform simultaneous pelvic floor electromyography (EMG) during an uroflow study.6 However, because most patients will likely respond to initial constipation management and bladder retraining, we recommend conservative therapy for three months before considering uroflowmetry or more invasive tests.

Voiding postponement

Particularly at toilet-training phase, children tend to delay urination while distracted playing, using electronic toys, or watching television. This behaviour often results in holding maneuvers, low voiding frequency, urgency, and daytime incontinence. Frequency of wetting significantly improves in 45% of children with daytime incontinence after a trial of timed voiding.7 Constipation is frequently associated with voiding postponement, as the mechanism to delay defecation is similar.

Extraordinary daytime urinary frequency

Children with daytime frequency usually present very small voided volumes more than eight times per day, typically less than 50% of expected bladder capacity (EBC: [age (years) + 2] × 30 in ml/weight [kg] × 7 [<1 year]), every five minutes to one hour.1,8,9 Other symptoms, such as dysuria, stream changes, daytime incontinence, enuresis, excessive fluid intake, and increased urinary volume are usually not present. Unlike other categories of voiding dysfunction, which are more frequent in girls by a 5:1 ratio, extraordinary daytime frequency invariably occurs in young boys and is self-limited.1,10,11

Underactive bladder

This urological condition is characterized by infrequent voiding, typically 2–4 times daily, and straining during micturition. Typically, children with underactive bladder (UB) voluntarily bend over or push the abdomen, in attempt to increase intra-abdominal pressure and start or complete voiding.5 Commonly the first void in the day occurs at home after school. Consequently, symptomatic UTI or asymptomatic bacteriuria, dribbling, enuresis, and/or constipation/encopresis are often concomitant. These children classically present an interrupted pattern on uroflow with a large post-void residual (PVR). Urotherapy is the first step in treatment, with an intensive bowel program. Occasionally alpha-blockers or more invasive modalities, such as clean intermittent catheterization (CIC), need to be instituted to assure emptying.

Hinman syndrome

Hinman Syndrome (HS) is the most severe form of nonneurogenic voiding dysfunction. It is probably caused by acquired behavioural and psychosocial disorders manifested by bladder dysfunction mimicking neurological disease. Despite its functional nature, children with HS commonly present signs suggestive of anatomical outlet obstruction, such as upper tract dilatation, bladder wall thickening and trabeculation, and impaired renal function, which may resemble posterior urethral valves or urethral stricture. Neurogenic causes must be excluded. As opposed to neurogenic bladder, HS patients will present with normal back and neurological exam and normal spinal cord on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The prevalence of HS is unknown. Onset typically occurs around toilet-training phase after a period of normality, but even infant and adult cases have been observed.12 Patients may present a constellation of symptoms, including urge incontinence, frequency, enuresis, infrequent voiding, incomplete voiding, intermittency, straining, UTI, and abdominal pain. Typically, children with HS will voluntarily contract the external sphincter and pelvic floor muscles resulting in intermittent urinary stream, increased PVR volumes and increased intravesical pressure. The possibility of sexual abuse must be considered in the context of functional disorders of the lower urinary tract, especially in severe cases like HS.13

Psychosocial burden and association with behavioural and neuropsychiatric disorders

The social stigma of persistent wetting and bowel accidents is a common problem faced by children with BBD and can lead to self-esteem issues, shame, isolation, poor school performance, aggressiveness, and other behavioural changes. In cases of intractable BBD, the involvement of a psychologist or psychiatrist must be considered. The relationship between bladder dysfunction and neuropsychiatric disorders is well-documented. Mental illness does increase the risk of both bowel and bladder incontinence. The mental condition may interfere with the child/teenager’s ability to reach the toilet on time because of disorganized thinking, confusion, or inattention. More importantly, medications used to treat anxiety or obsessive compulsive disorders (OCD) can directly affect the bladder and bowel, making the person less aware of the need to void.

A retrospective study showed that the majority of patients seen for voiding dysfunction (60%) present at least one psychosocial factor.14 There is a greater prevalence of adverse childhood experiences among patients with BBD than neuropsychiatric disorders (51% vs. 25%, respectively). Also, the presence of psychological and behavioural disorders leads to less favourable treatment outcomes. For instance, children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) tend to have more significant LUTS15,16 and are more challenging to treat. In those cases, it is essential to treat both ADHD and BBD for optimal response to treatment. A similar approach may prove beneficial for children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

Diagnostic approach

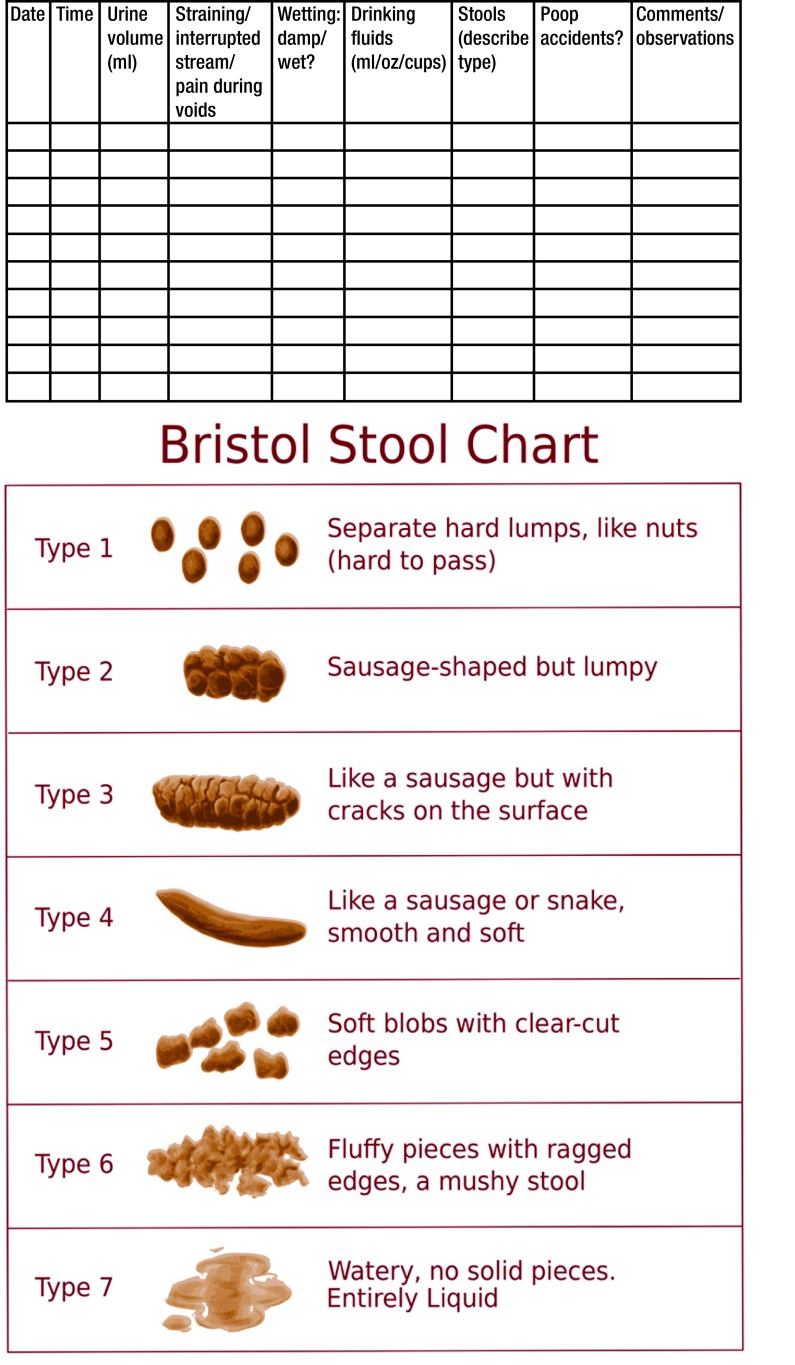

In addition to a clinical history and physical examination, voiding and bowel diaries are essential for the initial evaluation of BBD (Fig. 1). Although seven- to 14-day diaries are recommended in the literature,5 long diaries can be daunting for parents or caregivers while balancing work and busy schedules. Therefore, we recommend 48–72-hour diaries to provide more reliable information. The record of urine volumes helps estimate the maximum voided volume (MVV) that correlates with the EBC. The Bristol stool chart is a valuable tool for diagnosis and monitoring constipation treatment response. Roma III classification is the most acceptable criteria for the definition of functional constipation in the pediatric population (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Example of bladder and bowel diary. A complete 48–72-hour diary, including a copy of the Bristol stool (BS) chart, may provide helpful information for the diagnosis and to evaluate treatment response of bladder bowel dysfunction in children. Daily frequency and type of stools must be described by the child and caregivers, using the BS chart as a reference.11

Table 1.

The Rome III pediatric criteria for functional constipation and functional non-retentive fecal incontinence (FNRFI) (Adapted from Dos Santos et al1)

| Functional constipation | ≥2 of the following in a child ≥4 years old not fitting IBS criteria:

|

| FNRFI (non-retentive fecal incontinence) | All of the following in a child ≥4 years:

|

Currently, a large number of voiding diary applicationss are available for mobile recording. Some of these allow the patient to share information with the healthcare provider. Voiding scores are useful instruments that provide both qualitative and quantitative evaluation of bladder and bowel symptoms at baseline and longitudinally and are therefore, valuable for diagnosis and to assess treatment response. The Dysfunctional Voiding Score System (DVSS), proposed and validated by Farhat et al,17 is the most commonly used voiding score worldwide (Table 2). The Vancouver Symptom Score for Dysfunctional Elimination Syndrome (VSSDES) has also been validated in a large cohort in the U.S. and has proven effective for diagnosis and evaluation of treatment of BBD.18,19

Table 2.

An example of validated voiding score system: The Dysfunctional Voiding Scoring System (Adapted from Farhat et al17)

| Over the last month | Almost never (0) | Less than half the time (1) | About half the time (2) | Almost every time (3) | Not applicable (NA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I have had wet clothes or wet underwear during the day | Ipsum | ||||

| When I wet myself, underwear is soaked | |||||

| I miss having a bowel movement every day | |||||

| I have to push for my bowel movements to come out | |||||

| I only go to the bathroom one or two times each day | |||||

| I can hold onto my pee by crossing my legs, squatting or doing the “pee dance” | |||||

| When I have to pee, I cannot wait | |||||

| I have to push to pee | |||||

| When I pee it hurts | |||||

| Parents to answer. Has your child experienced something stressful like to example below? Please circle if ALL that apply | No (0) | Yes (3) | |||

| • New baby | |||||

| • New home | |||||

| • New school | |||||

| • School problems | |||||

| • Abuse (sexual/physical) | |||||

| • Home problems (divorce/death) | |||||

| • Special events (birthday) | |||||

| • Accident/injury | |||||

| • Others | |||||

School difficulties, sexual or physical abuse, family problems (divorce/death), new baby at home, new school, new home.

The most complementary test indicated for the investigation of LUTS is urinalysis. In the presence of leukocyturia, pyuria, bacteriuria, and/or nitrates, a urine culture should be obtained from a reliable source to rule out UTI (as previously discussed). If no pyuria or bacteriuria is identified, BBD is likely the diagnosis. Importantly, urine cultures should not be obtained for surveillance when the child is asymptomatic. Positive cultures in this context are in keeping with asymptomatic bacteriuria (AB) that should not be misdiagnosed as UTI and do not require treatment with antibiotics or further imaging of the urinary tract. This discussion is particularly important with worldwide escalating antibiotic resistance rates. Specific gravity (SG) is an indicator of urine concentration and can provide valuable information. Hematuria, proteinuria, and glycosuria may suggest underlying medical conditions, such as glomerular diseases and type 1 diabetes.

Renal and bladder ultrasound (RBUS) is usually not required for the initial evaluation of LUTS except in more severe cases. However, it not only can be of assistance in delineating the urinary tract, but transverse rectal diameter ≥ 3 cm correlate with evidence of rectal fecal impaction on digital rectal examination (DRE).20 Therefore, the transabdominal ultrasound may corroborate the diagnosis of constipation. Also, the measurement of the PVR volume can be obtained on ultrasonography, so this study, if ordered properly, can suggest constipation and give an idea of bladder functionality.

Uroflowmetry with EMG followed by PVR measurement is reserved for more recalcitrant cases, but is a relatively non-invasive method to assess the coordination of the bladder contraction with voluntary relaxation of the external striated sphincter. A single abnormal uroflowmetry at base-line would not alter initial management, but would clearly mandate long-term attention.

Urodynamics and videourodynamics provide in-depth information about capacity, compliance, and contractility of the bladder. However, these are more invasive studies and are not routinely indicated for the diagnosis of BBD because not much is added beyond a detailed history, careful physical examination, urine volume, and voiding/bladder diary.

Voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) is recommended in the presence of documented recurrent febrile UTIs to rule out VUR, especially if the upper tracts are abnormal and/ or bladder wall thickening and trabeculations are present. Those signs are associated with obstructive urinary symptoms and, in boys, are suggestive of posterior urethral valve (PUV). Children with BBD and any degree of VUR have the highest risk of recurrent febrile UTI (56%).21 Additionally, VUR may take longer to resolve on its own in the presence of BBD.2,21,22 If VUR is diagnosed in a toilet-trained child, BBD must be ruled out and treated before considering surgical repair.

MRI of the spine (or spine ultrasound before six months of age) must be considered to rule out tethered cord and other neurogenic causes of BBD in the presence of any neurological deficits, particularly of the lower limbs, significant cutaneous lesions in the lumbosacral region, bony abnormalities of the spine, or after an incidental finding of occult spine dysraphism in abdominal X-ray in children with BBD.1

Treatment

Behavioural

Urotherapy and constipation management are the mainstay of treatment of BBD. Urotherapy is the non-pharmacological and non-surgical treatment of LUTs that involves education of child and caregivers, adequate hydration, timed voiding, and pelvic floor muscle awareness, aiming to optimize relaxation and contraction of muscles when appropriate. At least 50% of children with BBD will improve with behavioural changes and constipation treatment only.1 Recently unpublished data from our group including 19 children with BBD seen by a network of pediatricians in the greater Toronto area demonstrated significant improvement of DVSS after three months of timed voiding, adequate fluid intake, and management of constipation with polyethylene glycol 3350 (11 ± 4.3 vs. 5.2 ± 1.6, unpaired t test p=0.009).

Educational resources

Whenever possible, educational resources must be shared with families prior to first visit. Usually in the presence of child’s persistent wetting or recurrent UTIs, parents are understandably concerned, anxious, or frustrated. The access to educational materials, such as videos, brochures, or handouts before the first visit gives families the opportunity to start urotherapy while waiting for the appointment and will likely improve compliance to treatment. Materials should use simple language and avoid medical jargon. They should include general information about urinary tract anatomy and bladder dynamics, natural history and causes of BBD, and tips on appropriate toilet position and posture for voiding and passing stools.

Adequate hydration

More frequent urination and emptying will occur when appropriate hydration is achieved. Recommended daily fluid intake will vary according to child’s age and weight, but an overall recommendation of drinking one cup of water after every void (6–8 cups per day) is a good strategy for improving hydration and bladder cycling.

Timed voiding

Children must be encouraged to void on a schedule every 2–3 hours with the help of a vibrating watch or timer (older children can use their phone’s or tablet’s timer). Timed voiding is recommended only while the child is awake to develop a regular voiding pattern. A physician’s or nurse’s note to school may be helpful to maintain timed voiding schedule during weekdays. A general practical recommendation is: “Every two hours try to pee, wash your hands, and have a cup of water”. Voiding diaries and voiding scores must be regularly completed to monitor response to treatment.

Pelvic floor awareness and retraining

Adequate position and toilet posturing must be discussed with children and caregivers. Kegel exercises can be taught to older children and adolescents to improve contraction and relaxation of pelvic muscles in the presence of OAB or DV. Biofeedback may be particularly beneficial for younger children22,23 for whom Kegel exercises are difficult to communicate. A review of the literature, including studies published over the past 10 years reporting the effect of BBD treatment with behavioural therapy, pelvic floor muscles retraining (PFMR), and biofeedback on the rate of UTIs is summarized in Table 3. Neurostimulation will be further discussed in the surgical treatment section.

Table 3.

Summary of studies over the past 10 years reporting the effect of bladder and bowel dysfunction treatment with behavioural therapy, PFMR, and biofeedback on the rate of UTIs38

| Study (year) | Study design | Subjects | Treatment groups | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amira et al (2013)39 | Non-randomized, prospective study | 72 girls with LUTS and/or constipation | Standard therapy plus animated biofeedback PFMR for all | 78% free of UTI compared to baseline (p<0.001) |

| Zivkovic et al (2012)40 | Non-randomized, prospective study 68% free of UTI compared to baseline (p< 0.0001) | 43 children with DV | Standard therapy plus diaphragmatic breathing exercises and PFMR for all | 68% free of UTI compared to baseline (p<0.0001) |

| Kajbafzadeh et al (2011)41 | Randomized, controlled trial | 80 children with DV and/or bowel dysfunction | Behavioural therapy plus animated biofeedback PFMR vs. behavioural therapy only | Overall, 71% free of UTI compared to baseline (p=0.02) |

| Vesna et al (2010)42 | Randomized, controlled trial | 86 children with DV | Standard therapy plus diaphragmatic breathing exercises and PFMR vs. standard therapy | 86% and 72% free of UTI compared to baseline (p<0.001 and p<0.05) |

| Vasconcelos et al (2006)43 | Randomized, clinical trial | 59 children with LUTS and/or bowel dysfunction | 24 PFM exercise sessions over 3 months vs. biofeedback PFMR sessions over 2 months | 96 and 93% free of UTI compared to baseline (p=0.023 and p=0.004) |

DV: dysfunctional voiding; LUTD: lower urinary tract dysfunction; PFMR: pelvic floor muscle retraining;UTI: urinary tract infection; VCUG: voiding cystourethrography; VUR: vesicoureteral reflux.

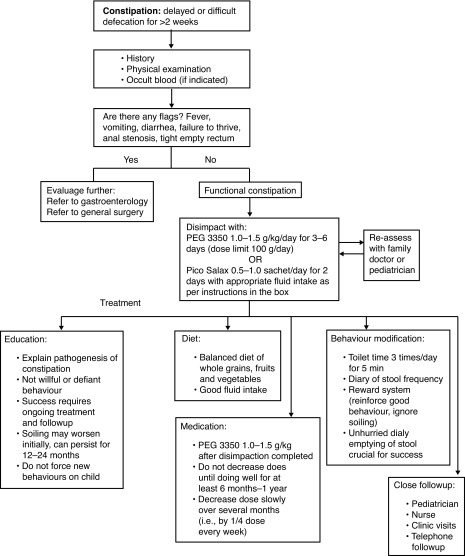

Bowel regimen

Constipation must be treated with increased dietary fiber intake, optimal hydration, and stool softeners. The treatment of chronic constipation includes four phases: 1) education; 2) disimpaction; 3) prevention of re-accumulation of feces; and 4) followup. Virtually all patients with LUTS are presumed constipated and initially started on stool softeners. Polyethylene glycol (PEG 3350) is the most commonly used stool softener in children.1,2 It can be safely used in six month-old children and older (Fig. 2). We also suggest establishing a schedule for the child to sit on the toilet twice daily 15–20 minutes after meals. More aggressive regimens may include admission for disimpaction with PEG 3350 via nasogastric tube, depending on severity of constipation.

Fig. 2.

Constipation treatment algorithm. Adapted from The Hospital for Sick Children constipation fluxogram 2013.

Pharmacological

Pharmacological treatment must only be considered if no improvement occurs after six months of urotherapy ± biofeedback and adequate constipation treatment has been assured (Fig. 3). At this point, anticholinergics are the mainstay of treatment of OAB. The goal of treating OAB is to alleviate the discomfort related with persistent urgency and frequency with or without incontinence. This chronic condition may require long-term treatment. Seven different anticholinergics are currently available for the treatment of both detrusor overactivity (DO) in adults — oxybutynin, tolterodine, solifenacin, trospium, darifenacin, propiverine, and fesoterodine — but none of them has been shown superior to others. 24 To date, oxybutynin, a M1, M2, and M3 receptors antagonist, is the only anticholinergic approved by both the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Health Canada for pediatric use with the benefit of having a liquid formulation available. Presently, it is the most commonly anticholinergic drug prescribed in Canada (87.2%).25 The initial recommended dose is 0.1–0.2 mg/kg/dose, 2–3 times daily (maximum 5 mg/dose).

Fig. 3.

Proposed algorithm for the diagnosis and management of bladder and bowel dysfunction in children. LUT: lower urinary tract; OAB: overactive bladder; Pos Hx UTI: positive history of documented febrile urinary tract infection; RBUS: renal and bladder ultrasound; UA: urinalysis; UDS: urodynamics study; uroflow with EMG & PVR: uroflowmetry with electromyography and post-void residual; VCUG: voiding cystourethrogram.

A prospective, open-label study published by Bolduc et al showed that solifenacin is an effective alternative to improve OAB symptoms in cases refractory to oxybutynin or tolterodine.26 Common adverse events reported in children — constipation, dry mouth, nausea, visual disturbance, and headaches — are typical of the antimuscarinic class. Up to 40% of children with OAB do not respond the anticholinergics.27

With a different mechanism of action, mirabegron, a β3-adrenoceptor agonist, appears to be a safe and effective alternative for treating refractory OAB in children.28 This new medication has also been proposed as an adjuvant drug in combination with solifenacin for pediatric cases refractory to anticholinergics alone. Very few side effects have been reported with mirabegron. Although hypertension has been a concern in adults, this has not been seen in a recent prospective pilot study of mirabegron in children with OAB.28

Selective alpha blockers, such as tamsulosin (0.2–0.4 mg oral daily), silodosin, and doxazosin, can help relax the external sphincter in children with DV. These drugs appear to be effective for improving bladder emptying in children with OAB, incontinence, recurrent UTIs, and increased PVR.29 They can be used in combination with anticholinergics (and/or biofeedback) when OAB coexists with functional bladder outlet obstruction.

The use of prophylactic antibiotics should be considered in the management of children with BBD and VUR, specifically in the context of recurrent febrile UTIs and renal parenchymal abnormalities.22 In those cases, prophylaxis is recommended for a few months (4–6 months) while BBD is being addressed, especially if VUR is present. If febrile UTIs recur after optimized bladder and bowel management, surgical repair of VUR should be considered. Whether prophylaxis should be a routine adjunct in the BBD patient with UTI but without VUR is controversial. Sometimes, in these instances, it can be helpful to break the vicious cycle of continued UTI, painful voiding, and resultant holding with delayed voiding. Thus, tailoring pharmacotherapy, including judicious use of antibiotics, is essential in addition to ongoing urotherapy.

Surgical treatment

Refractory detrusor overactivity

Minimally invasive treatment is indicated for pediatric BBD cases refractory to behavioural and pharmacological therapy. OnabotulinumtoxinA has been used as an alternative for the treatment of refractory OAB. It causes a long-lasting (up to nine months), reversible, chemical denervation.30 Repeated injections can be given without loss of efficacy. Histological studies have not found ultrastructural changes in bladder muscle after injection.31 Neurostimulation (neuromodulation) is the most promising therapy in the management of OAB. It can be performed after implantation of stimulators usually in the sacral area (SNS). More recently, it has been performed transcutaneously either by sacral transcutaneous stimulation (TENS) or paratibial stimulation (PTENS). It has shown a positive effect on overall quality of life, constipation, and urinary dysfunction, as well as decreased need for anticholinergics.32–34 Constipation improved in 100% of TENS patients, but in only 55% of patients treated with oxybutynin (p=0.03 vs. p=0.07). TENS showed no side effects, whereas side effects were present in more than half of patients treated with anticholinergic therapy, resulting in discontinuation of treatment in 13.3% of patients in the latter group. TENS was, therefore, as effective as oxybutynin to treat OAB in children, but more effective against constipation with no detectable side effects.34 Additionally, TENS significantly improves quality of life and symptom severity in children with refractory bowel bladder dysfunction.

Intractable constipation

The antegrade continence enema procedure (ACE) should be offered only when maximal medical therapies (diet, medications, enema therapy) have failed. A temporary ACE procedure is an effective treatment in children with intractable defecation disorders. At our institution, the ACE procedure has been performed laparoscopically in the last few years. Common postoperative complications of the ACE procedure are fecal leakage (43%), wound infection (52%), and stomal stenosis (39%). A total of 86% of the patients are satisfied with the Malone stoma.35 Other variations to attain antegrade colonic irrigation included the use of a cecostomy button or Chait tube.36,37 Although these procedures dictate an obvious external appliance as opposed to a hidden stoma accessed by catheter, they are oftentimes placed minimally invasively by intervention radiologists and are reversed by simply removing the device, allowing the mature stoma to heal when patient bowel control has improved. Hence, in a neurologically normal patient, where one would hope that the problem is self-limited, such a temporary alternative might be preferred. Fecal continence rates of up to 85% for ACE and 90% for cecostomy tubes have been reported. Complications include stomal pain (23% of patients) and difficulty with catheterizing (19%) following ACE, and difficulty flushing (26%) following cecostomy. Each approach poses unique risks and benefits, supporting the concept that physicians, patients, and families need to understand the differences to make an informed, individualized decision.

Conclusion

BBD is an increasingly common pediatric problem. It is commonly associated with VUR and recurrent UTIs. BBD is also associated with significant psychosocial burden and can negatively affect children’s quality of life and self-esteem. In cases of intractable BBD, the involvement of a psychologist or psychiatrist must be considered. The majority of patients will improve with urotherapy. Pharmacological treatment must only be considered if no improvement occurs after six months of urotherapy At this point in time, we recommend a consistent, intensive, family- and child-focused approach to this endemic and often frustrating spectrum of patients, with pharmacotherapy and invasive treatments selected for patients who have complied with but still fail urotherapy and/or whose renal status is at risk.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Dr. Dos Santos has been an advisor and received honoraria from Duchesnay. Dr. Koyle has been an advisor for Duchesnay. Dr. Lopes reports no competing personal or financial interests.

This paper has been peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Dos Santos J, Varghese A, Koyle M. Recommendations for the management of bladder bowel dysfunction in children. Pediatr Therapeut. 2014;4:1. https://doi.org/10.4172/2161-0665.1000191. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halachmi S, Farhat W. Interactions of constipation, dysfunctional elimination syndrome, and vesicoureteral reflux. Adv Urol. 2008:828275. doi: 10.1155/2008/828275. https://doi.org/10.1155/2008/828275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaplan S, Dmochowski R, Cash B. Systematic review of the relationship between bladder and bowel function: Implications for patient management. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67:205216. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12028. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.12028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jackson E. Urinary tract infections in children: Knowledge updates and a salute to the future. Pediatr Rev. 2015;36:153–64. doi: 10.1542/pir.36-4-153. https://doi.org/10.1542/pir.36-4-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Austin P, Bauer S, Neveus T. The standardization of terminology of lower urinary tract function in children and adolescents: Update report from the Standardization Committee of the International Children’s Continence Society. J Urol. 2014;191:1863–5. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.01.110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2014.01.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wenske S, Van Batavia J, Glassberg K. Analysis of uroflow patterns in children with dysfunctional voiding. J Pediatr Urol. 2014;10:250–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2013.10.010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpurol.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allen H, Austin J, Cooper C. Initial trial of timed voiding is warranted for all children with daytime incontinence. Urology. 2007;69:962–5. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.01.049. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2007.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen H, Nussinovitch M, Frydman M. Extraordinary daytime urinary frequency in children. J Fam Pract. 1993;37:28–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bergmann M, Corigliano T, von Vigier R. Childhood extraordinary daytime urinary frequency — a case series and a systematic literature review. Pediatr Nephrol. 2009;24:789–95. doi: 10.1007/s00467-008-1082-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-008-1082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feldman AS, Bauer SB. Diagnosis and management of dysfunctional voiding. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006;18:139–47. doi: 10.1097/01.mop.0000193289.64151.49. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mop.0000193289.64151.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swithinbank L, Carr J, Abrams P. Longitudinal study of urinary symptoms and incontinence in local school children. Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl. 1994;163:67–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Claudon P, Fotso-Kamdem A, Aubert D. The non-neurogenic neurogenic bladder (Hinman’s syndrome) in children: What are prognostic criteria based on a 31-case multicentric study. Prog Urol. 2010;20:292–300. doi: 10.1016/j.purol.2009.09.034. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.purol.2009.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krajewski W, Wojciechowska J, Kołodziej A. Urogenital tract disorders in children suspected of being sexually abused. Cent European J Urol. 2016;69:112–7. doi: 10.5173/ceju.2016.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Logan B, Correia K, Slattery M. Voiding dysfunction related to adverse childhood experiences and neuropsychiatric disorders. J Pediatr Urol. 2014;10:634–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2014.06.012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpurol.2014.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schast A, Zderic S, Carr M. Quantifying demographic, urological, and behavioural characteristics of children with lower urinary tract symptoms. J Pediatric Urol. 2008;4:127–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2007.10.007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpurol.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duel B, Steinberg-Epstein R, Lerner M. A survey of voiding dysfunction in children with attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder. J Urol. 2003;170:1521–3. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000091219.46560.7b. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ju.0000091219.46560.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farhat W, Bagli D, McLorie G. The dysfunctional voiding scoring system: Quantitative standardization of dysfunctional voiding systems in children. J Urol. 2000;164:1011–5. doi: 10.1097/00005392-200009020-00023. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5347(05)67239-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Afshar K, Mirbagheri A, Scott H. Development of a symptom score for dysfunctional elimination syndrome. J Urol. 2009;182:1939–43. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.03.009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drzewiecki B, Thomas J, Pope J. Use of validated bladder/bowel dysfunction questionnaire in the clinical pediatric urology setting. J Urol. 2012;188:1578–83. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.02.036. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2012.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klijn A, Asselman M, de Jong T. The diameter of the rectum on ultrasonography as a diagnostic tool for constipation in children with dysfunctional voiding. J Urol. 2004;172:1986–8. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000142686.09532.46. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ju.0000142686.09532.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keren R, Shaikh N, Hoberman A. Risk factors for recurrent urinary tract infection and renal scarring. Pediatrics. 2015;136:e13–21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-0409. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-0409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peters C, Skoog S, Snodgrass W. Summary of the AUA guideline on management of primary vesicoureteral reflux in children. J Urol. 2010;184:1134–44. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.05.065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2010.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yagci S, Kibar Y, Akay O, et al. The effect of biofeedback treatment on voiding and urodynamic parameters in children with voiding dysfunction. J Urol. 2005;174:1994–7. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000176487.64283.36. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ju.0000176487.64283.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blais AS, Bergeron M, Bolduc S. Anticholinergic use in children: Persistence and patterns of therapy. Can Urol Assoc J. 2016;10:137–40. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.3527. https://doi.org/10.5489/cuaj.3527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Madhuvrata P, Singh M, Abdel-Fattah M. Anticholinergic drugs for adult neurogenic detrusor overactivity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol. 2012;2:816–30. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.02.036. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2012.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bolduc S, Moore K, Hamel M. Prospective open label study of solifenacin for overactive bladder in children. J Urol. 2010;184:1668–73. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.03.124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2010.03.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park S, Pai K, Suh H. Efficacy and tolerability of anticholinergics in Korean children with overactive bladder: A multicenter, retrospective study. J Korean Med Sci. 2014;29:1550–4. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2014.29.11.1550. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2014.29.11.1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blais AS, Nadeau G, Bolduc S. Prospective pilot study of mirabegron in pediatric patients with overactive bladder. Eur Urol. 2016;70:9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.02.007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cain M, Wu S, Rink R. Alpha blocker therapy for children with dysfunctional voiding and urinary retention. J Urol. 2003;170:1514–5. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000085961.27403.4a. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ju.0000085961.27403.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DasGupta R, Murphy F. Botulinum toxin in pediatric urology: A systematic literature review. Pediatr Surg Int. 2009;25:19–23. doi: 10.1007/s00383-008-2260-3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-008-2260-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Figueroa V, Romao R, Bägli DJ. Single-centre experience with botulinum toxin endoscopic detrusor injection for the treatment of congenital neuropathic bladder in children: Effect of dose adjustment, multiple injections, and avoidance of reconstructive procedures. J Pediatr Urol. 2014;10:368–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2013.10.011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpurol.2013.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barroso U, Lordêlo P. Electrical nerve stimulation for overactive bladder in children. Nat Rev Urol. 2011;8:402–7. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2011.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Veiga M, Queiroz A, Barroso U. Parasacral transcutaneous electrical stimulation for overactive bladder in children: An assessment per session. J Pediatr Urol. 2016. [Epub ahead of print]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpurol.2016.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Veiga ML, Lordêlo P, Farias T, et al. Evaluation of constipation after parasacral transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in children with lower urinary tract dysfunction: A pilot study. J Pediatr Urol. 2013;9:622–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2012.06.006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpurol.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Griffiths D, Malone P. The Malone antegrade continence enema. J Pediatr Surg. 1995;30:68–71. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(95)90613-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3468(95)90613-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lorenzo A, Chait P, Farhat W. Minimally invasive approach for treatment of urinary and fecal incontinence in selected patients with spina bifida. Urology. 2007;70:568–71. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.04.026. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2007.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sinha C, Grewal A, Ward H. Antegrade continence enema (ACE): Current practice. Pediatr Surg Int. 2008;24:685–8. doi: 10.1007/s00383-008-2130-z. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-008-2130-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Awais M, Rehman A, Khan N. Evaluation and management of recurrent urinary tract infections in children: State of the art. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2015;13:209–31. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2015.991717. https://doi.org/10.1586/14787210.2015.991717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amira P, Dušan P, Gordana M. Bladder control training in girls with lower urinary tract dysfunction. Int Braz J Urol. 2013;39:118–27. doi: 10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2013.01.15. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2013.01.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zivkovic V, Lazovic M, Vlajkovic M. Diaphragmatic breathing exercises and pelvic floor retraining in children with dysfunctional voiding. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2012;48:413–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kajbafzadeh A, Sharifi-Rad L, Ghahestani S. Animated biofeedback: An ideal treatment for children with dysfunctional elimination syndrome. J Urol. 2011;186:2379–85. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.07.118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2011.07.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vesna Z, Milica L, Marina V. Correlation between uroflowmetry parameters and treatment outcome in children with dysfunctional voiding. J Pediatr Urol. 2010;6:396–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2009.09.013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpurol.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vasconcelos M, Lima E, Caiafa L. Voiding dysfunction in children. Pelvic-floor exercises or biofeedback therapy: A randomized study. Pediatr Nephrol. 2006;21:1858–64. doi: 10.1007/s00467-006-0277-1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-006-0277-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]