Abstract

Ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency (OTCD) is an X-linked disorder, with an estimated prevalence of 1 per 80000 live births. Female patients with OTCD develop metabolic crises that are easily provoked by non-predictable common disorders, such as genetic (private mutations and lyonization) and external factors; however, the outcomes of these conditions may differ. We resuscitated a female patient with OTCD from hyperammonemic crisis after she gave birth. Hyperammonemia after parturition in a female patient with OTCD can be fatal, and this type of hyperammonemia persists for an extended period of time. Here, we describe the cause and treatment of hyperammonemia in a female patient with OTCD after parturition. Once hyperammonemia crisis occurs after giving birth, it is difficult to improve the metabolic state. Therefore, it is important to perform an early intervention before hyperammonemia occurs in patients with OTCD or in carriers after parturition.

Keywords: Brain image, Delivery, Glutamine, Amino acid, Ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency, Urea cycle disorders, Uterus, Hyperammonemia

Core tip: Hyperammonemia crisis after parturition in patients with ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency (OTCD) is often fatal and difficult to predict. It is important to perform early intervention before hyperammonemia occurs in patients with OTCD or in carriers after parturition.

INTRODUCTION

Urea cycle disorders (UCDs) are one of the most common inherited metabolic diseases in Japan, with an estimated prevalence of 1 per 50000 live births. The urea cycle is the metabolic pathway that eliminates excess endogenous and exogenous nitrogen from the body by modifying ammonia into urea, thereby reducing its toxicity. This cycle comprises 6 different enzymes, including ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC; EC 2.1.3.3).

OTC deficiency (OTCD; Mc Kusick No. 311250) is an X-linked disorder, with an estimated prevalence of 1 per 80000 live births[1]. The traditional treatment for OTCD is a low-protein diet. Sodium benzoate and/or sodium phenylbutyrate are significant as an alternative pathway therapy[2,3].

In female patients with OTCD, metabolic crises can be easily provoked by non-predictable common disorders, such as genetic (private mutations and Lyonisation) and external factors, and sometimes may be fatal.

We resuscitated a female patient with OTCD, who maintained a relatively stable condition using a self-restricted protein diet, from hyperammonemic crisis after parturition. Hyperammonemia after giving birth in a female patient with OTCD can be fatal[4], and this type of hyperammonemia persists for an extended period of time. If patients with OTCD develop hepatic coma with hyperammonemia ≥ 300 μmol/L, hemodialysis as well as treatments that target alternative nitrogen metabolism pathways and arginine or/and citrulline treatments should be used to control blood ammonia levels immediately to avoid damage to the brain[5-7]. We discontinue hemodialysis and control blood ammonia levels using the alternative pathway therapy, and arginine or/and citrulline treatments when their blood ammonia levels decrease to < 180 μmol/L[8,9]. Hemodialysis is excellent for the removal of ammonia in the body; however, this treatment does not suppress the production of ammonia and removes useful medications from the body. Moreover, although a high-caloric infusion that largely consists of glucose is important, the early administration of essential amino acids and low-protein is useful for preventing protein catabolism in the body and for controlling ammonia levels[10].

Here, we discuss the cause and treatment of hyperammonemia in a female patient with OTCD after parturition.

CASE REPORT

A 37-year-old female patient who was diagnosed with late-onset OTCD was followed by her doctor, and was introduced to our institute after pregnancy. She was the first child of nonconsanguineous parents and had no family history of hyperammonemia. She presented with seizures at the age of 7 and developed hyperammonemia following the administration of valproic acid as treatment for the seizure. She was diagnosed with OTCD by liver biopsy examination (liver OTC enzyme activity that was 30% the level of healthy patients) (Table 1). She had visited the emergency room previously due to hyperammonemia and had undergone hemodialysis for impaired consciousness at the age of both 18 years and 21 years. Despite this, she followed a self-restricted protein diet and L-carnitine treatment. She naturally became pregnant at the age of 37 years and delivered an unaffected male baby by vacuum extraction at 41 wk and 1 d of gestation. Her blood ammonia value was 68 μmol/L at delivery, 59 μmol/L at 10 h after delivery, and 54 μmol/L at 24 h after delivery. She developed hyperammonemia (194 μmol/L) 4 d after delivery, but was discharged 6 d after delivery because her blood ammonia level decreased to 60 μmol/L following arginine and citrulline treatment. Upon discharge, she consumed a hamburger at a fast food restaurant and 250 g of beef at her home. She was hospitalized on an emergency basis at midnight because of hyperammonemia (180 μmol/L) with impaired consciousness (Table 2). Blood ammonia levels instantly decreased to 82 μmol/L by the continuous administration of arginine. She then underwent hemodialysis and continuous hemodiafiltration under respirator management in the intensive care unit because her blood ammonia level increased to 339 μmol/L, with a grade III hepatic coma. Moreover, she received a high-calorie infusion (2500 kcal/d), arginine (80 mg/kg per day), citrulline (150 mg/kg per day), sodium benzoate (150 mg/kg per day), and sodium phenylbutyrate (140 mg/kg per day) as an alternative pathway therapy. Following this, her hyperammonemia improved.

Table 1.

Data at diagnosis

| Serum AA (nmol/mL) | Uric AA (nmol/mg Cre) | Cerebrospinal fluid AA (nmol/mL) | |

| Amino acids | |||

| Glutamine | 1754.6 | 282.9 | 534.1 |

| Glutamic acid | 90.8 | 277.9 | TR |

| Ornithine | 60.3 | TR | 5.8 |

| Citrulline | 19.7 | ND | ND |

| Arginine | 54.4 | ND | 14.2 |

| Lysine | 162.8 | ND | 15.9 |

| Urinary orotic acid | 13.3 μg/mg Cre | ||

| Liver enzyme assay | Patient (μmol/mg protein/min) | Control | |

| CPS1 | 0.024 | 0.023-0.074 | |

| OTC | 0.17 (30% of the control) | 0.51-1.51 | |

AA: Amino acids; Cre: Creatinine; TR: Trace; ND: Not determined; CPS1: Carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase 1; OTC: Ornithine transcarbamylase.

Table 2.

Laboratory data upon admission

| AST | 28 (IU/L) |

| ALT | 34 (IU/L) |

| γGTP | 19 (IU/L) |

| LDH | 369 (IU/L) |

| ALP | 338 (IU/L) |

| CHE | 219 (IU/L) |

| T-Bil | 0.6 (mg/dL) |

| TP | 6.8 (g/dL) |

| Alb | 3.3 (g/dL) |

| BUN | 12.3 (mg/dL) |

| Cre | 0.44 (mg/dL) |

| NH3 | 180 (μmol/L) |

| Amy | 90 (IU/L) |

| CK | 111 (IU/L) |

| CRP | 0.3 (mg/dL) |

| WBC | 12000 (/μL) |

| Hb | 10.7 (g/dL) |

| Plt | 26.4 × 104 (/μL) |

| PT | 112 (%) |

| APTT | 97 (%) |

| P-FDP | 37.2 (μg/mL) |

| Fib | 347 (mg/dL) |

| AT III | 134 (%) |

AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; γGTP: γ glutamyl transpeptidase; LDH: Lactase dehydrogenase; ALP: Alkaline phosphatase; CHE: Choline esterase; T-Bil: Total bilirubin; TP: Total protein; Alb: Albumin; BUN: Blood urea nitrogen; Cre: Creatinine; Amy: Amylase; CK: Creatine kinase; CRP: C-reactive protein; WBC: White blood cell count; Hb: Hemoglobin; Plt: Platelets; PT: Prothrombin time; APTT: Activated partial thromboplastin time; P-FDP: Plasma fibrin degradation products; Fib: Fibrinogen; AT III: Antithrombin III.

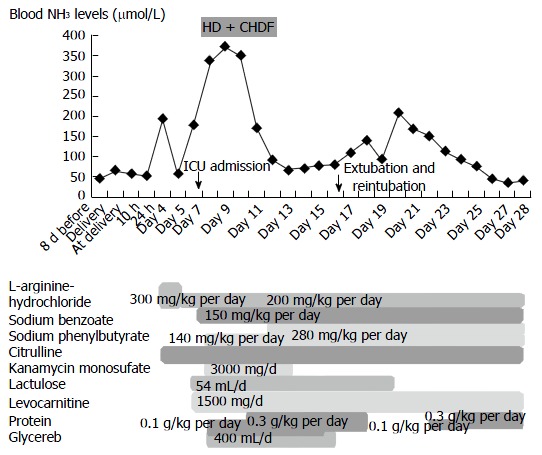

Although extubation was attempted because of stable blood ammonia levels following these treatments (Figure 1), she was reintubated because she could not maintain respiration. Her ammonia levels increased again to 210 μmol/L after experiencing physical stress during extubation, before gradually decreasing to 60 μmol/L. She developed sepsis and was managed at the intensive care unit for 43 d.

Figure 1.

Blood ammonia levels after delivery. The patient was admitted on emergency basis because of impaired consciousness 7 d after delivery (day 7) and was intubated. She then underwent HD and CHDF under ICU management (from day 8 to day 12). HD: Hemodialysis; CHDF: Continuous hemodiafiltration; ICU: Intensive care unit.

The cause of hyperammonemia for this case was considered to be: (1) physical stress experienced during vaginal parturition and fasting while withstanding pain for a prolonged period of time; (2) excessive protein intake after discharge; and (3) metabolic changes during puperium following anabolism for the repair of the parturient canal, including the uterus, after delivery and catabolism for producing maternal milk.

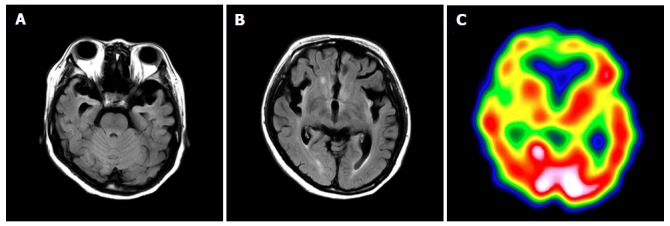

Presently, she uses medication and has been able to raise her child following hospital discharge despite her brain magnetic resonance imaging and single-photon emission computed tomography indicating atrophy of the bilateral frontal and temporal lobes with decreased bold flow (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Brain magnetic resonance imaging and single-photon emission computed tomography 7 mo after delivery. A and B: FLAIR demonstrates atrophy of the bilateral frontal and temporal lobes, and a high signal for the cortex and subcortex on both sides of insula, the ventral tamporal lobe and the frontal lobe bottom. The signal is elevated bilaterally in the putamen, caudate nucleus, and front globus pallidus; C: Single-photon emission computed tomography shows bilaterally decreased blood flow in the frontal lobe, ventral temporal lobe, basal ganglia, and thalamus.

DISCUSSION

We resuscitated a female patient with late-onset OTCD who developed hyperammonemia crisis after giving birth. We previously reported the long-term outcome for patients with OTCD in Japan[8,9,11]. The expected survival rate at 35 years of age in late-onset OTCD patients was less than 30% for both male and female patients according to data obtained from 1978-1995[8], and 89% for male patients and 84% for female patients according to data obtained from 1999-2009[9]. The more recent long-term outcome improved compared to previous outcomes due to improved medication, hemodialysis, and liver transplantation; however, the long-term survival of patients is not guaranteed. These patients always have the potential to develop hyperammonemia due to metabolic stress during infection, surgery or delivery, even if the hyperammonemia is resolved at the time of onset and their medical state is well controlled thereafter.

It has been reported that female patients with OTCD are likely to develop hyperammonemia that persists for 6 to 8 wk at 3 to 14 d after delivery[12,13]. Although the cause of hyperammonemia after delivery in female patients with OTCD is not clear, it is considered to be related to increased protein load for collagen catabolism following involution of the uterus[14]. We also consider that hyperammonemia is related to metabolic changes in their bodies during puerperium.

She developed hepatic coma that required respiratory management, which required 40 d to resume breathing without assistance and to regain improved level of consciousness. She continued to produce maternal milk a month after the onset of hyperammonemia, and hyperammonemia persisted even after maternal milk production stopped. The cause of long-term hyperammonemia is not only puperium. Mitochondrial abnormalities within the liver of patients with OTCD has been previously demonstrated[15], and hyperammonemia itself disrupts the function of mitochondria[16]. Therefore, it has been considered that the impaired mitochondria in cases of hyperammonemia aggravates OTCD and results in long-term hyperammonemia.

In this case, her blood ammonia levels remained at 60 μmol/L from during pregnancy to 3 d after delivery and elevated at 4 d after delivery. She did not receive sodium benzoate or sodium phenylbutyrate, which are utilized as alternative pathway therapies, because her blood ammonia levels soon decreased after arginine and citrulline treatment. We consider that even female patients with OTCD who do not receive sodium benzoate or sodium phenylbutyrate therapy are recommended to start receiving sodium benzoate or sodium phenylbutyrate treatment from the start of labor to immediately after delivery, if they have developed severe hyperammonemia[17]. Benzoate is conjugated with glycine to form hippurate, which is rapidly excreted in the urine. For each mole of benzoate administered, 1 mole of nitrogen is removed. Phenylbutyrate is activated to the CoA ester, which is metabolized by β-oxidation in the liver to form phenylacetyl-CoA, which is then conjugated with glutamine. The resulting phenylacetylglutamine is excreted into the urine, and 2 moles of nitrogen are excreted for each mole of phenylbutyrate[5].

Therefore, it is effective for OTCD patients who have never received sodium phenylbutyrate or sodium benzoate to preliminarily receive such a medication when the blood ammonia level is expected to increase during excessive stress, such as during delivery. Because ammonia is a final product in amino acid metabolism, it is believed that there is a time lag from stress load to the increased blood ammonia levels. It may be effective to measure blood glutamine levels to predict whether the blood ammonia levels will increase or to estimate the change in body condition in patients with OTCD because glutamine is a supplier of ammonia and one of the markers of the medical condition[18,19]. Furthermore, the blood value is high, even in OTCD carriers[20]. Moreover, it may be useful to adjust the amount of sodium phenylbutyrate or sodium benzoate based upon blood glutamine levels.

The patient should have been monitored without discharge from our hospital because hyperammonia crisis was likely to develop anytime within 2 wk after parturition and she could not consume protein-rich food in our hospital. Moreover, we consider that hyperammonemia crisis could have been avoided if she had received sodium benzoate or sodium phenylbutyrate therapy immediately after delivery. Caesarean section and the halting maternal milk production might contribute to preventing a hyperammonemia crisis.

Moreover, this patient was a candidate for liver transplantation (LT) since she was susceptible to developing hyperammonemia crisis for non-predictable common disorders. If female patients with OTCD who have had hyperammonemia crisis are going to be married and give birth, LT before pregnancy may be a treatment option because LT prevents recurrent hyperammonemia attacks and contributes to improved quality of life in patients with UCD[21-24].

In conclusion, we treated a female patient with late-onset OTCD, who developed hyperammonemia crisis after delivery. Hyperammonemia crisis after delivery in patients with OTCD is often fatal and difficult to predict. It is important to perform early intervention before hyperammonemia occurs in patients with OTCD or carriers after delivery. Once hyperammonemia crisis occurs following parturition, it is difficult to improve the metabolic state of the patient.

COMMENTS

Case characteristics

Hyperammonemia crisis with hepatic coma after delivery.

Clinical diagnosis

Hyperammonemia crisis with hepatic coma.

Differential diagnosis

Carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase 1 deficiency, arginosuccinate synthetase deficiency, arginosuccinate lyase deficiency and arginase 1 deficiency were considered to be a differential diagnosis.

Laboratory diagnosis

Increased blood glutamine and urinary orotic acid levels as well as impaired liver ornithine transcarbamylase enzyme activity.

Imaging diagnosis

Atrophy of the bilateral frontal and temporal lobe, as indicated by brain magnetic resonance imaging.

Treatment

Arginine, citrulline, sodium benzoate, sodium phenylbutyrate, and hemodialysis.

Related reports

A peak ammonia concentration less than 180 μmol/L was shown to be a marker of a good neurodevelopmental prognosis, and a peak ammonia concentration of more than 360 μmol/L was a marker of a bad prognosis.

Term explanation

UCDs: Urea cycle disorders; OTCD: Ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency; LT: Liver transplantation.

Experiences and lessons

It is important to perform early intervention before hyperammonemia occurs in patients with OTCD or carriers following parturition.

Peer-review

Hyperammonemia after delivery in a female patient with OTCD can be fatal. In this case report, authors have discussed the cause and treatment of hyperammonemia in a female patient with OTCD after delivery. This case indicates that it is important to perform early intervention before hyperammonemia occurs in patients with OTCD or carriers after delivery.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Institutional review board statement: This study was approved by the ethical committee of the Faculty of Life Science, Kumamoto University.

Informed consent statement: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient and her husband.

Conflict-of-interest statement: None.

Peer-review started: November 9, 2016

First decision: December 15, 2016

Article in press: January 14, 2017

P- Reviewer: Cao WK, Han ZG, Morioka D S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

References

- 1.Nagata N, Matsuda I, Oyanagi K. Estimated frequency of urea cycle enzymopathies in Japan. Am J Med Genet. 1991;39:228–229. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320390226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brusilow SW, Valle DL, Batshaw M. New pathways of nitrogen excretion in inborn errors of urea synthesis. Lancet. 1979;2:452–454. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)91503-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brusilow SW. Phenylacetylglutamine may replace urea as a vehicle for waste nitrogen excretion. Pediatr Res. 1991;29:147–150. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199102000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Açıkalın A, Dişel NR, Direk EÇ, Ilgınel MT, Sebe A, Bıçakçı Ş. A rare cause of postpartum coma: isolated hyperammonemia due to urea cycle disorder. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34:1324.e3–1324.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feillet F, Leonard JV. Alternative pathway therapy for urea cycle disorders. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1998;21 Suppl 1:101–111. doi: 10.1023/a:1005365825875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nagasaka H, Yorifuji T, Murayama K, Kubota M, Kurokawa K, Murakami T, Kanazawa M, Takatani T, Ogawa A, Ogawa E, et al. Effects of arginine treatment on nutrition, growth and urea cycle function in seven Japanese boys with late-onset ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. Eur J Pediatr. 2006;165:618–624. doi: 10.1007/s00431-006-0143-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schaefer F, Straube E, Oh J, Mehls O, Mayatepek E. Dialysis in neonates with inborn errors of metabolism. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14:910–918. doi: 10.1093/ndt/14.4.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uchino T, Endo F, Matsuda I. Neurodevelopmental outcome of long-term therapy of urea cycle disorders in Japan. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1998;21 Suppl 1:151–159. doi: 10.1023/a:1005374027693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kido J, Nakamura K, Mitsubuchi H, Ohura T, Takayanagi M, Matsuo M, Yoshino M, Shigematsu Y, Yorifuji T, Kasahara M, et al. Long-term outcome and intervention of urea cycle disorders in Japan. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2012;35:777–785. doi: 10.1007/s10545-011-9427-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leonard JV. The nutritional management of urea cycle disorders. J Pediatr. 2001;138:S40–44; discussion S44-45. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.111835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakamura K, Kido J, Mitsubuchi H, Endo F. Diagnosis and treatment of urea cycle disorder in Japan. Pediatr Int. 2014;56:506–509. doi: 10.1111/ped.12439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Langendonk JG, Roos JC, Angus L, Williams M, Karstens FP, de Klerk JB, Maritz C, Ben-Omran T, Williamson C, Lachmann RH, et al. A series of pregnancies in women with inherited metabolic disease. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2012;35:419–424. doi: 10.1007/s10545-011-9389-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lamb S, Aye CY, Murphy E, Mackillop L. Multidisciplinary management of ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC) deficiency in pregnancy: essential to prevent hyperammonemic complications. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:pii: bcr2012007416. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2012-007416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shum JK, Melendez JA, Jeffrey JJ. Serotonin-induced MMP-13 production is mediated via phospholipase C, protein kinase C, and ERK1/2 in rat uterine smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:42830–42840. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205094200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shapiro JM, Schaffner F, Tallan HH, Gaull GE. Mitochondrial abnormalities of liver in primary ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. Pediatr Res. 1980;14:735–739. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198005000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rama Rao KV, Norenberg MD. Brain energy metabolism and mitochondrial dysfunction in acute and chronic hepatic encephalopathy. Neurochem Int. 2012;60:697–706. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mendez-Figueroa H, Lamance K, Sutton VR, Aagaard-Tillery K, Van den Veyver I. Management of ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency in pregnancy. Am J Perinatol. 2010;27:775–784. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1254240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maestri NE, McGowan KD, Brusilow SW. Plasma glutamine concentration: a guide in the management of urea cycle disorders. J Pediatr. 1992;121:259–261. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)81200-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berry GT, Steiner RD. Long-term management of patients with urea cycle disorders. J Pediatr. 2001;138:S56–60; discussion S60-61. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.111837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arn PH, Hauser ER, Thomas GH, Herman G, Hess D, Brusilow SW. Hyperammonemia in women with a mutation at the ornithine carbamoyltransferase locus. A cause of postpartum coma. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1652–1655. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199006073222307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whitington PF, Alonso EM, Boyle JT, Molleston JP, Rosenthal P, Emond JC, Millis JM. Liver transplantation for the treatment of urea cycle disorders. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1998;21 Suppl 1:112–118. doi: 10.1023/a:1005317909946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morioka D, Kasahara M, Takada Y, Shirouzu Y, Taira K, Sakamoto S, Uryuhara K, Egawa H, Shimada H, Tanaka K. Current role of liver transplantation for the treatment of urea cycle disorders: a review of the worldwide English literature and 13 cases at Kyoto University. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:1332–1342. doi: 10.1002/lt.20587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kasahara M, Sakamoto S, Shigeta T, Fukuda A, Kosaki R, Nakazawa A, Uemoto S, Noda M, Naiki Y, Horikawa R. Living-donor liver transplantation for carbamoyl phosphate synthetase 1 deficiency. Pediatr Transplant. 2010;14:1036–1040. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2010.01402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wakiya T, Sanada Y, Mizuta K, Umehara M, Urahasi T, Egami S, Hishikawa S, Fujiwara T, Sakuma Y, Hyodo M, et al. Living donor liver transplantation for ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. Pediatr Transplant. 2011;15:390–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2011.01494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]