1. Introduction

Temporal summation of pain has typically been studied by asking participants to rate the intensity of late pain sensations in response to repetitive noxious stimuli [22]. The progressive increase in pain intensity represents a behavioral correlate of “wind-up” of spinal dorsal horn wide dynamic range neurons and is often used as an indirect marker of central sensitization in humans [20]. Sensitized dorsal horn neurons also exhibit changes in their spatial properties including an enlargement of the receptor fields [30]. However, the effect of noxious repetitive stimulation on the spatial dimensions of the pain experience remains poorly characterized. To address this issue, we recently conducted a pilot study, which showed for the first time a progressive increase in the spatial perception of the painful stimuli during repetitive identical nociceptive stimuli in older but not younger adults [19]. In contrast to some studies [8,15], the older adults did not exhibit greater temporal summation of pain intensity compared to younger adults. These results could have two important implications. First, age-related changes in pain facilitatory processes may be reflected in a greater extent by central amplification of spatial rather than amplitude properties of the pain experience. Second, when participants are trained to differentiate between ratings of the intensity and spatial perception of the painful stimuli, temporal summation of spatial aspects versus intensity may be a more robust measure in older adults.

While the mechanisms underlying the experience of pain during thermal heat stimulation have been extensively studied, the experience and mechanisms of cold pain are less well understood [7]. Indeed, the most commonly used stimuli for assessment of temporal summation of pain include heat and mechanical stimuli, no studies have examined age differences in the temporal summation of cold pain. A noxious cold stimulus affects a variety of primary afferent input (e.g., slowly adapting mechanoreceptors and rapidly adapting mechanoheat and mechanocold nociceptors) and, thus, can elicit myriad painful and non-painful sensations [6,7,27]. Whether the temporal summation of cold pain follows a similar pattern to the temporal summation of heat pain in healthy older and younger adults remains unknown.

A primary aim of this study was to validate the findings of our pilot study [19] and examine changes in the spatial perception and intensity of heat pain during a temporal summation protocol in a larger sample of healthy older and younger adults. Additionally, we wanted to explore for the first time the temporal summation of cold pain in a large sample. We hypothesized that age differences in temporal summation would be evident in the heat and cold pain trials and more robust when measuring the summation of the spatial perception vs. intensity of the painful stimuli. Some research also suggests that age differences in pain may differ as a function of sex [1,16,25]; however, little work has looked at the age-sex interaction in pain facilitatory processes. Thus, a secondary aim of this study was to examine whether age differences in temporal summation of pain differed as a function of sex.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants included 104 healthy younger adults (Age: M=34.5, SD=12.8, age range: 18–59 years; 56 females and 48 males) and 40 healthy older adults 60 years of age or older (Age: M=67.5, SD=5.1, age range: 60–77 years; 22 females and 18 males). The sample was recruited as part of a larger study examining age-related changes in pain inhibitory and facilitatory function. Recruitment and study procedures were approved by the University of Florida Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Study exclusion criteria included a Mini Mental Status score below 23, current use of narcotics or chronic use of analgesics, serious systemic disease (e.g., diabetes and thyroid problems), uncontrolled hypertension, systemic disease that restricts normal daily activities, neurological problems with significant changes in somatosensory and pain perception at the intended stimulation sites, and serious psychiatric conditions (e.g., schizophrenia and bipolar disorder). Participants refrained from the use of any pain medication or coffee on the day of testing.

2.2. Apparatus

Testing was performed on a Thermo-Electric Stimulation System (Neuroanalytics, Gainesville FL). Thermal stimuli were administered by a 36×36mm thermode (Peltier thermoelectric device) housed in a freestanding stimulation module that was adjustable from 20–28 inches in height. At rest, the thermode is recessed behind a cutout in a thermally neutral plastic surface, out of contact with the skin, which rests on the plastic surface. The thermode is brought into reproducible light skin contact and retracted following each contact by a solenoid-powered mechanism with temperature and thermode positions controlled by a computer; and avoid subject-experimenter interactions and bias.

Experimental pain was measured with an electronic visual analog scale (eVAS). The eVAS consisted of a low-friction sliding potentiometer of 100 mm travel. The left endpoint of the scale was identified as “no pain”, while the right endpoint was defined as “intolerable pain”. There were nine hash marks between these two anchors. The position of the slider was electronically converted into a pain rating between 0 and 100. The slider automatically returned to the left (“no pain”) position when so required by the protocol. The eVAS was mounted into the surface of a small inclined desk positioned to facilitate precise operation with minimal fatigue. The experimental set-up allows the participant to be separated from the investigator and was facing away to minimize non-verbal communication and transmission of bias.

2.3. Study procedures

2.3.1. Orientation and training session

Individuals who were interested in the study were provided information about the procedures, informed about privacy regulations and reviewed and signed an Informed Consent Form. Eligibility for the study was determined after participants completed a health history questionnaire, supplemented by interview and a blood pressure measurement. As part of this orientation participants watched a PowerPoint presentation with imbedded video and audio overlay that described using a 0–100 pain scale, the nature of second pain, and the temporal summation testing sequence including rating the pain between thermode contacts. Participants then received at least 4 practice trials with the pain testing procedures using several temperatures. During the training session, an individualized temperature was determined such that participants would experience at least moderate pain during the temporal summation series. When pain ratings failed to reach 20 or surpassed 60 during contacts 4–6 the testing temperature was adjusted up or down respectively as needed. Using an individualized temperature has been shown to increase the success rate in demonstration of temporal summation and minimizes both floor and ceiling effects [11,14]. Finally, participants also completed the Graded Chronic Pain Scale (GCPS), which is an 8-item scale that asks about pain severity and disability that results from pain. The GCPS was designed for use in general population surveys and primary practice settings [29]. The 8-items were preceded by a question that asked whether pain has occurred in a list of bodily sites and the respondent identified which pain site was the most bothersome. Following the Orientation and Training sessions, participants were scheduled for the testing sessions (described below). The overall study involved multiple visits; consequently, staging testing sessions based on the menstrual cycle phase of ovulation for females was not practical. Rather, females likely were randomly spaced across menstrual cycle phases. Past research is mixed regarding the influence of the menstrual cycle on pain perception [26]; however, several studies indicate that thermal pain sensitivity does not vary across the menstrual cycle [10,28].

2.3.2. Testing sessions

Participants were seated on a comfortable chair and relaxed for several minutes. Then, two blood pressure readings were taken separated by 5 minutes. A third blood pressure measurement was taken if there was a change of greater than 5% in the first two readings. During the session, subjects completed an ascending/descending series, trials of offset analgesia, and temporal summation using thermal stimuli.

This paper presents data from trials for ratings of thermal heat and cold stimuli, with participants rating pain intensity or the spatial perception of pain for both stimuli. Size ratings were standardized across participants with the use of a 11×14 size scale which presented 10 circles progressively increasing in size and marked in increments of 10 (See Figure 1, diameter of each circle increased in a linear manner, R2 = 0.99). Participants were instructed that the circles represented how large or small the area the “pain feels like it is coming from”. Heat trials used the volar forearm while cold trials were tested at the thenar eminence of the palm to reduce sensitization. The temperature of the thermode to be used in the temporal summation trials was verified for each participant based on their data from the orientation and training session (see above). Prior to the administration of the temporal summation trials, participants watched an additional short video describing the procedure and providing instructions on the difference between rating the spatial dimension and intensity of the painful stimuli. Then, participants were administered up to two practice trials to ensure comfort with the procedure. All temporal summation trials reported here used a series of 10 contacts with stimulus contact interval (SI) of 0.8-sec and an inter-stimulus-interval (ISI) of 2.5-sec during which the thermode was retracted. Participants completed two trials of heat pain for intensity and size and a single trial of cold pain for both intensity and size. All trials were separated by a minimum of 3 minutes. Order of administration was counterbalanced for type of rating (size – intensity) and side of stimulation (right – left) with consecutive trials administered on the opposite side. When returning to the forearm, the site stimulated was adjusted to minimize overlap.

Figure 1.

Size of pain rating scale.

2.4 Data reduction and analysis

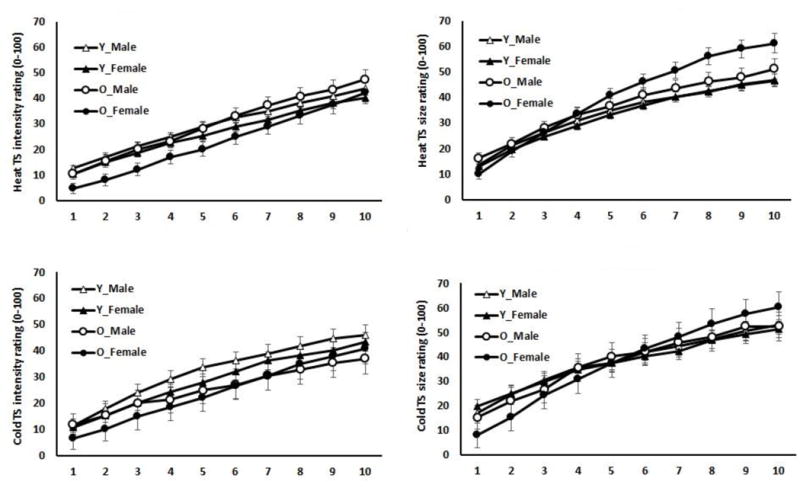

Descriptive statistics were calculated for age, the severity and disability subscales of the Graded Chronic Pain Scale, and thermode temperature for the heat and cold TS trials. The pulse analysis (described below) showed that for each TS trial, regardless of rating type or thermal condition, ratings significantly and sequentially increased across all pulses (e.g., 1 < 2 < 3 < 4, etc.) (See Figure 2). Therefore, the magnitude of temporal summation was calculated by subtracting the pain intensity/size rating following the first pulse from the pain intensity/size rating following the 10th pulse. In addition, the slope of the pain ratings from the first pulse that was painful (Pain1) to the maximum pain rating for each TS trial was also calculated with the following formula: (max pain rating – Pain1 pain rating)/number of pulses to max pain rating.

Figure 2.

Means (Standard Errors) of size and intensity of pain ratings following each pulse for cold and heat temporal summation (TS) trials as a function of age and sex. Y=Younger; O=Older.

To determine whether participants could differentiate between ratings of size versus intensity of pain, test-retest reliability of the heat TS scores (i.e., Heat TS – intensity trial 1 vs. Heat TS – intensity trial 2; Heat TS – size trial 1 vs. Heat TS – size trial 2) were calculated with Interclass correlation coefficients (ICCs). Additionally, ICCs were calculated between the intensity and size ratings for Heat TS trials 1 and trials 2 (i.e., Heat TS – intensity trial 1 vs. Heat TS – size trial 1; Heat TS – intensity trial 2 vs. Heat TS – size trial 2). Theoretically, ICCs should be higher for size/size trial comparisons compared to size/intensity trial comparisons.

Between-subjects ANOVAs were conducted to determine whether the heat and cold thermode test temperatures and scores on the GCPS severity and disability subscales differed by age and sex. To determine whether the spatial dimension and intensity of perceived pain significantly summated in the heat and cold trials, repeated measures ANOVAs were conducted on the eVAS pain ratings (pulses 1 through 10) during the size and intensity cold and heat temporal summation trials, separately (i.e., 4 different analyses). Sex and age were added as covariate.

To determine whether the magnitude of temporal summation differed as a function of age, sex, and rating type (size vs. intensity), Age × Sex × Rating Type mixed model ANOVAs with repeated measures on Rating Type were conducted on the magnitude of Heat TS and Cold TS scores (i.e., 10th pulse pain – 1st pulse pain). Thermode temperature was added as a covariate. Post hoc tests were conducted using Tukey’s honestly significant difference procedures. Similar analyses were conducted on the slope of pain intensity and size ratings (max pain rating – Pain1 pain rating)/number of pulses to max pain rating.

3. Results

The data are presented in the text and tables as means ± standard deviation unless otherwise noted. The results indicated that scores on the severity and disability subscales of the GCPS did not differ as a function of sex or age (p’s >.05). Table 1 shows the mean scores for the GCPS for both age groups by sex. Overall, the means confirmed that participants in this study reported very low levels of clinical pain. The analyses on thermode temperature for the heat trials revealed significant differences for age group (p=.006), with older adults having a higher thermode temperature compared to younger adults (See Table 1). However, no significant differences existed between groups on thermode temperature for the cold TS trials, p’s >.05.

Table 1.

Mean (±SD) thermode temperature and GCPS scores as a factor of age and sex

| Younger Adults

|

Older Adults

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| Heat TS Thermode Temperature (C°) | 48.7±1.6 | 48.4±1.6 | 49.8±1.7 | 48.9±1.6 |

| Cold TS Thermode Temperature (C°) | 1.5±5.5 | 1.8±5.5 | 1.3±4.0 | 1.7±5.5 |

| GCPS Severity score | 3.7±8.2 | 2.9±8.2 | 4.0±6.6 | 3.0±8.6 |

| GCPS Disability score | 2.4±8.3 | 3.2±8.3 | 2.4±8.3 | 1.2±8.7 |

3.1. Test-Retest Reliability of the Heat TS Scores

Table 2 presents the ICCs for the heat TS trials for each age group by sex. For the heat intensity TS trials, the ICC’s ranged from 0.63 to 0.84. For the heat size TS trials, the ICC’s ranged from 0.69 to 0.92. These coefficients indicate moderate to substantial test-retest reliability for the heat intensity TS trials and the heat size TS trials. To help determine whether participants could differentiate between rating the size and intensity of pain, we also calculated ICC’s between the individual size and intensity trials. These ICC’s ranged from 0.17 to 0.56, with the majority of coefficients falling below 0.50. Collectively, the data suggest that participants were rating different aspects of pain perception in the size and intensity trials.

Table 2.

Interclass Correlation Coefficients for temporal summation of heat trials

| Younger Adults

|

Older Adults

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| Intensity T1 vs. Intensity T2 | 0.66 | 0.71 | 0.63 | 0.84 |

| Size T1 vs. Size T2 | 0.69 | 0.76 | 0.82 | 0.92 |

| Intensity T1 vs. Size T1 | 0.17 | 0.41 | 0.40 | 0.56 |

| Intensity T2 vs. Size T2 | 0.56 | 0.48 | 0.43 | 0.46 |

3.2. Summation of heat pain intensity ratings and size estimates

Figure 2 presents the size and intensity of pain ratings following each pulse for cold and heat temporal summation (TS) trials as a function of age and sex. The repeated measures ANOVA conducted on pain ratings showed that each pulse sequentially summated (i.e., pulse 1 < pulse 2 < pulse 3 < pulse 4, etc.) in pain intensity (p<.001) and size (p=.005) for the heat trials.

3.3. Summation of cold pain intensity ratings and spatial estimates

Similar to the heat trials, the repeated measures ANOVA conducted on pain ratings showed that each pulse sequentially summated (i.e., pulse 1 < pulse 2 < pulse 3 < pulse 4, etc.) in pain intensity (p<.001) and size (p=.005) for the cold trials.

3.4. Sex and age differences in the magnitude and slope of heat TS

The three-way ANOVA conducted on the heat TS scores revealed a significant effect of age (p=.011) and a trial type × sex interaction (p=.016). However, these effects were superseded by a trial type × sex × age interaction, p=.049. Older females exhibited greater temporal summation of spatial ratings compared to temporal summation of intensity ratings and compared to all other groups (i.e., older males, younger males, younger females) on TS of spatial and intensity ratings. Table 3 provides the heat TS scores for each age group by sex.

Table 3.

Mean (±SD) maximum temporal summation of heat and cold as a factor of age, sex, and trial type

| Younger Adults

|

Older Adults

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | All | Male | Female | All | |

| Heat TS | ||||||

| Intensity | 30.5±15.9 | 29.6±16.5 | 30.0±16.2 | 34.8±16.3 | 36.5±17.0 | 35.7±16.8 |

| Size | 32.1±18.1 | 33.0±18.7 | 32.5±18.5 | 32.6±18.6 | 50.5±19.5 | 41.4±19.1 |

| Cold TS | ||||||

| Intensity | 34.7±22.1 | 33.2±23.1 | 34.0±22.6 | 26.3±22.0 | 33.4±24.3 | 29.4±23.1 |

| Size | 36.0±24.6 | 31.8±25.7 | 33.9±25.2 | 40.3±24.5 | 52.4±27.0 | 46.3±25.8 |

Analysis of the slope of heat pain ratings mirrored the findings of the heat TS scores, with a significant trial type × sex × age interaction, p=.030. The slope of the spatial ratings during the TS trials for older females was significantly greater than the slope of spatial ratings for all other groups and compared to the slopes of the intensity ratings. See Table 4 for the heat pain rating slopes for each age group and sex.

Table 4.

Mean (±SD) slope of pain ratings of cold and heat TS trials as a factor of age, sex, and trial type

| Younger Adults

|

Older Adults

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | All | Male | Female | All | |

| Heat TS | ||||||

| Intensity | 3.7±1.5 | 3.6±1.5 | 3.7±1.5 | 4.3±1.6 | 4.0±1.6 | 4.1±1.6 |

| Size | 4.6±2.2 | 4.4±2.3 | 4.5±2.2 | 4.1±2.3 | 5.9±2.4 | 5.1±2.4 |

| Cold TS | ||||||

| Intensity | 4.2±2.4 | 3.8±2.5 | 4.0±2.5 | 3.0±2.3 | 3.7±2.6 | 3.3±2.4 |

| Size | 4.3±2.9 | 4.2±3.0 | 4.2±2.9 | 4.5±2.7 | 5.5±3.0 | 5.0±2.9 |

3.5. Sex and age differences in the magnitude and slope of cold TS

The ANOVA conducted on the cold TS scores demonstrated a significant effect of trial type (p=.022) and trial type × age interaction (p=.001). Older adults exhibited greater temporal summation of size ratings (M=46.3±25.8) compared to younger adults (M=33.9±25.2) and compared to the temporal summation of intensity ratings for older (M=29.8±23.4) and younger adults (M=34.0±22.4). Table 3 provides the cold TS scores for each age group by sex.

Analysis of the slope of cold pain ratings mirrored the findings of the cold TS scores, with a significant trial type × age interaction, p=.010. The slope of the spatial ratings during the TS trials for older adults was significantly greater than the slope of spatial ratings for the younger adults and compared to the slope of the intensity ratings for the younger and older adults. See Table 4 for the cold pain rating slopes for each age group and sex.

4. Discussion

This study examined age and sex differences in the temporal summation of the spatial perception and intensity of pain during the delivery of noxious heat and cold stimuli. Several key and novel findings emerged from this study. First, we showed for the first time that cold pain sensations significantly summate during a traditional temporal summation protocol in healthy older and younger adults. Secondly, older adults experienced greater temporal summation of the percept of size of cold pain compared to younger adults. Third, older females experienced greater temporal summation of the percept of size of heat pain compared to older males and all younger participants. Fourth, no sex or age differences were found in the temporal summation of pain intensity for cold or heat trials.

4.1. Age and sex differenced in the TS of heat pain

Studies on age-related differences in the temporal summation of heat pain have provided mixed results with some studies finding enhanced summation of pain intensity in older adults [9,15] and others finding no age differences [1,19,12]. Additionally, even though sex differences in the temporal summation of pain have been commonly found in younger adults [9], only one study to date has examined the age by sex interaction in pain facilitatory processes [1]. Bartley and colleagues recently showed that women with knee osteoarthritis demonstrated greater temporal summation of pain compared to men with knee osteoarthritis, regardless of age. This study, however, examined a population with chronic pain and did not include a younger age group (i.e., middle-aged v. older adults). In a fairly large sample, we found no age or sex differences in the temporal summation of heat pain intensity. This is the second study in which when participants were trained to differentiate and rate the perceived size and intensity of heat pain, no age differences were observed in the intensity trials [19]. However, it should be noted that the age differences in the summation of pain intensity trended in the hypothesized direction (i.e., younger adults=30.0 vs. older adults=35.7). Additionally, the current study used an intermittent contact methodology to administer noxious heat and cold pulses, whereas most other studies have used constant contact, temperature ramping methods [1,8,15]. These methodological differences could also contribute to any contrasting results between the current study and past aging and sex-related temporal summation studies.

Interestingly, we revealed a significant influence of age on the temporal summation of the perceived size of heat pain, but only in females. Older females experienced significantly greater summation of the size of the painful area compared to all other participants. Our pilot study demonstrating age differences in the temporal summation of the size of pain was not powered to detect sex differences and included slightly more females than males in the older adult group [19]. Animal studies indicate that the neuronal events leading up to temporal summation produce an expansion of the receptive field area of dorsal horn neurons [4,17,23,30]. Research also suggests that neuron recruitment or activation of peripheral zones of neighboring receptor fields contribute to the spatial dimensions of pain, including the sensation that pain is spreading beyond the location of stimulation (i.e., radiation of pain) [21,24]. Receptor field expansion or neuron recruitment could contribute to the perception that the size of the area of pain is increasing during a temporal summation protocol. While we can only speculate on the exact mechanisms underlying the increased summation of painful area size, our results indicate dysfunctional modulation of the spatial dimensions of the painful experience by older females during repetitive noxious heat pulses.

4.2. Age and sex differenced in the TS of cold pain

A noxious cold stimulus can elicit a variety of painful and non-painful sensations, including cold sensations, prickling, aching, and a feeling of heat [6]. Intriguingly, pronounced prickling pain can even be evoked during the rewarming phase following a cold painful stimulus [5]. This complex cold pain experience is likely mediated by activation of cold thermoreceptors and cold-specific nociceptors, as well as modulation of warm receptors and mechanoheat nociceptor activity [6,7]. The temporal summation of cold pain sensations has received little attention [18]. Our data revealed that the intensity and size of cold pain sensations temporally summates in healthy young and old participants. Similar to the heat trials, we found no age or sex differences in the temporal summation of cold pain intensity trials. However, in contrast to the heat trials, we discovered age differences in the temporal summation of spatial perception of pain rather than a sex by age interaction. Older adults experienced greater summation of the spatial perception of painful cold compared to younger adults. It should be noted, however, that inspection of the data suggests that these age differences were primarily driven by the older females who demonstrated the greatest temporal summation of the spatial dimension of pain. Age differences in TS of cold pain could involve central (i.e., wind-up of spinal dorsal horn WDR neurons) and/or peripheral mechanisms. Mauderli et al. reported that with repetitive cold stimulation, aching cold pain intensity was related to skin temperature [18]. Aging is associated with impaired thermoregulation. Older adults exhibit decreased reflex vasoconstriction in skin during cold exposure, which could contribute to stronger temporal summation of cold pain in older adults [13]. However, it would be anticipated that this impaired thermoregulation would lead to greater TS of the intensity and spatial perception of cold pain. In addition, sex differences in the autonomic nervous system function cannot be excluded as contributing to our findings [2].

There are some limitations of the current study that should be acknowledged. First, recruitment for this study was primarily conducted through community-based advertisements and word of mouth, which could create a biased sample. Our sample was comprised of healthy adults and these results may not generalize to adults with chronic pain. Future research needs to determine whether enhanced pain facilitatory processes in older adults without chronic pain places them at risk for future pain. Using an individualized temperature to ensure participants experienced a moderate level of pain may have created a bias where highly sensitive participants received less intense stimuli. Research has shown that thermal stimulation at higher intensities induces greater rostral-caudal activation on spinal cord segments [3], which could alter both the intensity and spatial perception of pain. Thus, the higher thermode temperatures for the heat trials compared to younger adults (no temperature differences observed for the cold trials) could have influenced the heat TS results. However, we find it unlikely given that 1) only older women (who had ≤0.5°C temperature difference from younger adults) and not older men exhibited enhanced summation of size and 2) the findings for the TS slope mirrored those for TS magnitude. Finally, an important methodological issue regarding the validity of the temporal summation of spatial data involves the ability of participants to differentiate between ratings of painful size versus intensity. While we cannot completely guarantee that participants always rated the size of pain vs. intensity of pain when instructed to do so, the ICC data suggest that participants were rating different aspects of the pain experience when asked to rate pain intensity and the spatial perception of the painful stimuli. Additionally, the interclass correlation coefficients indicated good reliability between the two heat intensity TS trials and between the two heat size trials.

Despite these potential limitations, there are several strengths of this study. First, limited research has examined sex and age differences in pain modulatory processes in healthy adults. Our study highlights the importance of considering sex differences in pain and aging studies. Second, this study used novel methodology to investigate the effect of a traditional temporal summation protocol on the perceived spatial dimensions of the pain experience, which has largely been ignored in prior research. Finally, the current study is the first to report that older adults experience greater facilitation of noxious cold stimuli.

4.3. Summary and implications

In conclusion, the current study demonstrated that older adults, and in particular older females, are characterized by enhanced pain facilitatory processes. Given the discrepant results between the temporal summation of intensity and size trials in the current study, it is possible that spatial summation represents a different neural correlate of central sensitization relative to the summation of pain intensity. Furthermore, our results suggest that the temporal summation of spatial dimension during thermal stimulation may be a more robust measure of age-related changes in pain facilitatory processes compared to temporal summation of pain intensity. We have also added to the literature by showing that cold pain sensations temporally summate, with older adults showing greater cold pain summation relative to younger adults. Future studies should determine the clinical consequences of enhanced summation of the perceived size of the painful area during cold and heat temporal summation trials.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH-NIA Grant R01AG039659, Study of The Effects of Aging on Experimental Models of Pain Inhibition and Facilitation (JR).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Fillingim has received consulting fees, speaking fees, and/or honoraria from WebMD and Algynomics (less than $10,000 each) and owns stock or stock options in Algynomics. Dr. Staud has received consulting fees, speaking fees, and/or honoraria from Pfizer (less than $10,000). Other authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bartley EJ, King CD, Sibille KT, Cruz-Almeida Y, Riley JL, 3rd, Glover TL, Goodin BR, Sotolongo AS, Herbert MS, Bulls HW, Staud R, Fessler BJ, Redden DT, Bradley LA, Fillingim RB. Enhanced pain sensitivity among individuals with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: Potential sex differences in central sensitization. Arthritis Care & Research. 2016;68:472–80. doi: 10.1002/acr.22712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cankar K, Finderle Z. Gender differences in cutaneous vascular and autonomic nervous response to local cooling. Clin Auton Res. 2003;13(3):214–20. doi: 10.1007/s10286-003-0095-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coghill RC, Mayer DJ, Price DD. The roles of spatial recruitment and discharge frequency in spinal cord coding of pain: a combined electrophysiological and imaging investigation. Pain. 1993;53(3):295–309. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90226-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cook AJ, Woolf CJ, Wall PD, McMahon SB. Dynamic receptive field plasticity in rat spinal dorsal horn following C-primary afferent input. Nature. 1987;325:151–153. doi: 10.1038/325151a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis KD. Cold-induced pain and prickle in the glabrous and hairy skin. Pain. 1998;75:47–57. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00203-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis KD, Pope GE. Noxious cold evokes multiple sensations with distinct time course. Pain. 2002;98:179–185. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00043-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dubin AE, Patapoutian A. Nociceptors: the sensors of the pain pathway. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2010;120:3760–3772. doi: 10.1172/JCI42843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards RR, Fillingim RB. Effects of age on temporal summation and habituation of thermal pain: clinical relevance in healthy older and younger adults. J Pain. 2001;2:307–317. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2001.25525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fillingim RB, King CD, Ribeiro-Dasilva MC, Rahim-Williams B, Riley JL., 3rd Sex, Gender, and Pain: A review of recent clinical and experimental findings. J Pain. 2009;10:447–485. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fillingim RB, Maixner W, Girdler SS, Light KC, Harris MB, Sheps DS, Mason GA. Ischemic but not thermal pain sensitivity varies across the menstrual cycle. Psychosom Med. 1997;59(5):512–20. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199709000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Granot M, Granovsky Y, Sprecher E, Nir RR, Yarnitsky D. Contact heat-evoked temporal summation: Tonic versus repetitive-phasic stimulation. Pain. 2006;122:295–305. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harkins SW, Davis MD, Bush FM, Kasberger J. Suppression of first pain and slow temporal summation of second pain in relation to age. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1996;51:M260–M265. doi: 10.1093/gerona/51a.5.m260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kenney WL, Armstrong CG. Reflex peripheral vasoconstriction is diminished in older men. J Appl Physiol. 1996;80:512–515. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.80.2.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kong JT, Johnson KA, Balise RR, Mackey S. Test-Retest Reliability of Thermal Temporal Summation Using an Individualized Protocol. The Journal of Pain. 2013;14:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lautenbacher S, Kunz M, Strate P, Nielsen J, Arendt-Nielsen L. Age effects on pain thresholds, temporal summation and spatial summation of heat and pressure pain. Pain. 2005;115:410–418. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leveille SG, Zhang Y, McMullen W, Kelly-Hayes M, Felson DT. Sex differences in musculoskeletal pain in older adults. Pain. 2005;116:332–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li J, Simone DA, Larson AA. Windup leads to characteristics of central sensitization. Pain. 1999;79:75–82. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00154-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mauderli AP, Vierck CJ, Cannon RL, Rodrigues A, Shen C. Relationships between skin temperature and temporal summation of heat and cold pain. J Neurophysiol. 2003;90:100–109. doi: 10.1152/jn.01066.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naugle KM, Cruz-Almeida Y, Fillingim RB, Staud R, Riley JL., 3rd Novel method for assessing age-related differences in the temporal summation of pain. J Pain Res. 2016;9:195–205. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S102379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Price DD, Dubner R. Neurons that subserve the sensory-discriminate aspects of pain. Pain. 1977;3(4):307–38. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(77)90063-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Price DD, Hayes RL, Ruda M, Dubner R. Spatial and temporal transformations of input to spinothalamic tract neurons and their relation to somatic sensations. J Neurophysiol. 1978;41(4):933–47. doi: 10.1152/jn.1978.41.4.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Price DD, Hu JW, Dubner R, Gracely RH. Peripheral suppression of first pain and central summation of second pain evoked by noxious heat pulses. Pain. 1977;3(1):57–68. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(77)90035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pubols LM, Fogelsong ME, Vahle-Hinz C. Electorical stimulation reveals relatively ineffective sural nerve projections to dorsal horn neurons in the cat. Brain Res. 1986;371:109–122. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90816-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quevedo AS, Coghill RC. Filling-in, spatial summation, and radiation of pain: evidence for a neural population code in the nociceptive system. J Neurophysiol. 2009;102(6):3544–53. doi: 10.1152/jn.91350.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riley JL, 3rd, Gilbert GH. Orofacial pain symptoms: an interaction between age and sex. Pain. 2001;90:245–56. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00408-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riley JL, 3rd, Robinson ME, Wise EA, Price DD. A meta-analytic review of pain perception across the menstrual cycle. Pain. 1999;81(3):225–35. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00258-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simone DA, Kajander KC. Responses of cutaneous A-fiber nociceptors to noxious cold. J Neurophysiol. 1997 Apr;77(4):2049–60. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.4.2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soderberg K, Sunstrom Poromaa I, Nyberg S, Backstrom T, Nordh E. Psychophysically determined thresholds for thermal perception and pain perception in healthy women across the menstrual cycle. Clin J Pain. 2006;22(7):610–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ajp.0000210904.75472.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Von Korff M, Ormel J, Keefe FJ, Dworkin SF. Grading the severity of chronic pain. Pain. 1992;50:133–49. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90154-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woolf CJ, King AE. Dynamic alteration in the cutaneous mechanoreceptive fields of dorsal horn neurons in the rate spinal cord. J Neurosci. 1990;10:2717–2726. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-08-02717.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]