Abstract

Objectives

Small subcortical infarcts (SSI) frequently coexist with brain white matter hyperintensity (WMH) lesions. We sought to determine whether preexisting WMH burden relates to SSI volume, SSI etiology, and 90-day functional outcome.

Materials and Methods

We retrospectively studied 80 consecutive patients with acute SSI. Infarct volume was determined on diffusion weighted imaging and WMH burden was graded on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequences according to the Fazekas scale. SSI etiology was categorized as small vessel disease (SVD) vs. non-SVD related. Multivariable linear and logistic regression models were constructed to determine whether WMH burden was independently associated with the SSI volume and a poor 90-day outcome (modified Rankin scale [mRS] score >2), respectively.

Results

In unadjusted analyses, patients with non-SVD related SSI were older (p=0.002) and more frequently had multiple infarcts (p<0.001) than patients with SVD related SSI. In the fully adjusted model, WMH severity (Coefficient 0.07; 95%-CI 0.029–0.117; p=0.002) but not SSI etiology (p>0.1) were independently associated with the SSI volume. On multivariable logistic regression, worse WMH (OR 2.28; 95%-CI 1.04–4.99; p=0.040), SSI etiology (OR 9.20; 95%-CI 1.04–81.39; p=0.046), pre-admission mRS (OR 8.96; 95%-CI 2.65–30.27; p<0.001), and SSI volume (OR 1.98; 95%-CI 1.14–3.44; p=0.016) were associated with a poor 90-day outcome.

Conclusions

Greater WMH burden is independently associated with a larger SSI volume and a worse 90-day outcome.

Keywords: Infarction, magnetic resonance imaging, diffusion weighted imaging, white matter hyperintensity, small subcortical infarction

INTRODUCTION

It has been suggested that lacunar infarctions are more appropriately described by the term small subcortical infarction (SSI) because SSI have an uncertain fate: They have been shown to evolve into lacunar cavities, hyperintense lesions on T2-weighted sequences, or even leave little visible traces on conventional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (1). Based on consensus, SSI have been in part defined as a recent infarction within the territory of one perforating arteriole that should be <20 mm in its maximum diameter in the axial plane (1). However, there exists uncertainty regarding the definite upper size limit for SSI and factors that impact SSI size are poorly understood (1). Yet, a better knowledge of these factors is important because SSI morphology and size may provide clues regarding potential underlying mechanisms and clinical outcome (2–4).

SSI are related to small vessel disease (SVD) related pathology and patients with SSI frequently have vascular risk factors such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and tobacco smoking (5–7). White matter hyperintensity (WMH) lesions share these vascular risk factors (1,8). Accordingly, it may not be too surprising that the majority of patients with SSI have concomitant WMH (7). This may be an important observation because WMH has been associated with greater ischemic lesion size and worse outcomes after large arterial occlusion (9,10). However, there is a paucity of data regarding the potential association of pre-existing WMH lesion burden with SSI volume and functional outcome.

To better understand this issue, we sought to test the hypothesis that greater WMH lesion burden is associated with a larger SSI size as well as a worse 90-day functional outcome. In addition we sought to determine potential clinical and imaging variables that may differentiate SSI related to SVD vs. non-SVD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

This study was reviewed and approved by our Institutional Review Board. We retrospectively analyzed consecutive patients with acute supratentorial, subcortical ischemic stroke as shown on brain MRI obtained between 24 and 168 hours since symptom onset for reliable determination of DWI positive infarcts (11). All patients were prospectively included in our single academic center stroke registry between January 2013 and October 2014.

Patient demographics, laboratory data, comorbidities, preadmission medications, and stroke etiology (according to the Causative Classification System for Ischemic Stroke [CCS] (12)) were collected on all patients. NIHSS scores were assessed at the time of presentation. In all patients we determined type of lacunar syndrome based on patient description and neurological exam findings (13). The mRS was assessed at the time of presentation (pre-admission mRS), and at 90-days follow-up by a stroke-trained physician or stroke study nurse certified mRS using a simplified questionnaire algorithm (14). When the mRS was unavailable, the same observers reconstructed the score from the case description, according to the mRS criteria. We adhere to the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines (www.strobe-statement.org).

Neuroimaging protocol

Brain MRI included T1-, T2-, and fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR)-sequences as well as DWI. MRI was performed on a 1.5 Tesla scanner (GE Signa; GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI). GRE pulse sequence parameters included a repetition time of 76.6 ms, an echo time of 49.2 ms, a field of view of 22 x 22 cm, image matrix of 320 x 224, and 3-mm slice thickness with a 1.5 mm interslice gap. DWI was obtained using echo-planar imaging with a repetition time of 8000 ms, an echo time of 102 ms, a field of view of 22x22 cm, image matrix of 128x128, slice thickness 5 mm with a 1-mm interslice gap, and b-values of 0 s/mm2 and 1000 s/mm2. FLAIR was obtained with a repetition time of 9002 ms, an echo time of 143 ms, a field of view of 22x22 cm, image matrix of 256 x 224, and slice thickness 6 mm with a 1-mm interslice gap (15).

Image review and analysis

Images were reviewed independently by experienced readers (JH, NH) blinded to both clinical data and any follow-up scans. Lesions that were hyperintense on DWI and hypointense on the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps were considered acute ischemic lesions (15).

SSI were defined as a recent subcortical infarct within the territory of penetrating arteries in the deep gray or white matter and without known focal pathology in the parent artery at the site of origin of the penetrating artery (1,16). Since SSI size can occasionally extend beyond 20 mm in greatest diameter (1), no size limit for the infarct extent was imposed a priori for the purpose of this study (though, only a single included patient had an SSI with a maximal diameter exceeding this limit). Consistent with prior definitions, we also included patients that had more than one acute infarct if infarcts otherwise fit the criteria of a SSI (1,17). The SSI etiology was classified into SVD vs. non-SVD related according to the CCS.

Ischemic lesions on DWI were manually outlined using careful windowing to achieve the maximal visual extent of the acute DWI (b1000 trace-weighted) lesion and with reference to the ADC image to avoid confounding by adjacent WMH regions and old lacunar infarcts causing T2 shine-through. SSI was defined according to previously described criteria (3,5,18). To calculate the infarct volume infarct areas were outlined on each slice and then multiplied by the slice thickness plus the interslice gap. For all patients we calculated the maximal infarct volume (i.e., the volume of the largest SSI in each patient), which was used for all analyses unless stated otherwise. However, as approximately one third of included patients had more than one SSI, we additionally calculated the total infarct volume (by summing the individual SSI volumes) as well as the mean infarct volume (total infarct volume divided by the number of SSIs).

WMH was defined on FLAIR MRI according to the STandards for ReportIng Vascular changes on nEuroimaging (STRIVE) criteria (18) and graded according to the Fazekas scale (19) on the basis of visual assessment both periventricular (0=absent, 1=caps or pencil lining, 2=smooth halo, 3=irregular periventricular hyperintensities extending into deep white matter) and subcortical areas (0=absent, 1=punctuate foci, 2=beginning confluence of foci, 3=large confluent areas). The total Fazekas score was calculated by adding the periventricular and subcortical scores (16). We have previously demonstrated a high interrater reliability of WMH ratings in a set of 50 consecutive patients with an intraclass correlation coefficient for the total Fazekas score of 0.969 (95%-CI 0.943–0.983) for the two readers (15). To determine the association of the WMH lesion burden with the infarct volume and 90-day outcome we entered the total Fazekas score (range 0 to 6) as a continuous variable in all multivariable regression models. We additionally dichotomized the degree of WMH according to the median Fazekas score to 0–3 vs. 4–6 for statistical purposes.

Lastly, we quantified the number of cortical and subcortical microhemorrhages on GRE images as previously detailed (20).

Statistics

Univariable analyses

Unless stated otherwise, continuous variables are reported as mean±s.d. or as median (interquartile range [IQR]). Categorical variables are reported as proportions. Normality of data was examined using Shapiro-Wilk test. Between-group comparisons for continuous variables were made with unpaired t-Test and Mann-Whitney U test. Within-group comparisons were made using paired t-Test or Signed Rank test. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2-test or Fisher’s Exact test. ANOVA on Ranks with post-hoc Dunn’s method was used to compare between-group differences in the NIHSS and infarct volume, respectively. Given the small infarct volumes inherent to SSI and thus risk for relatively greater bias with measurement errors, we sought to determine whether manual SSI volumetry was reproducible across investigators we computed Spearman correlation coefficients (r) as well as performed Bland–Altman analysis in 20 randomly selected patients whose infarct volumes were outlined by an inexperienced (YM) vs. experienced (JH) investigator.

Multivariable Analyses

To test our primary hypothesis that WMH burden is independently associated with the size of SSI volume after adjustment for other covariates we constructed two preplanned multivariable linear regression analyses. To avoid model overfitting we used backward elimination (likelihood ratio). First, we adjusted for variables known to be associated with infarct volume: admission glucose level, rtPA use, age, and history of hypertension and atrial fibrillation (15,21). We also considered the SSI mechanism as determined by the CCS by adjusting for SVD vs. non-SVD related etiology (model 1). In a second model we additionally adjusted for the admission NIHSS and preadmission mRS; which are known to correlate with infarct extent, deficit severity, and 90-day functional outcome (model 2).

To address our second hypothesis we constructed two separate multivariable logistic regression models with backward elimination to determine whether WMH burden was independently associated with a poor 90-day functional outcome (mRS 3–6). We first adjusted for infarct volume (non-transformed), SSI mechanisms, age, and the interaction term of WMH burden x infarct volume (model 1). We then additionally adjusted for the pre-admission mRS and admission NIHSS (model 2).

To achieve a more suitable distribution for multivariable linear regression we transformed the NIHSS and infarct volume on the basis of a cube-root transformation (15). Collinearity diagnostics were performed (and its presence rejected) for all multivariable regression models. Two-sided p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM® SPSS® Statistics, Version 22 (IBM®-Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

Recruitment

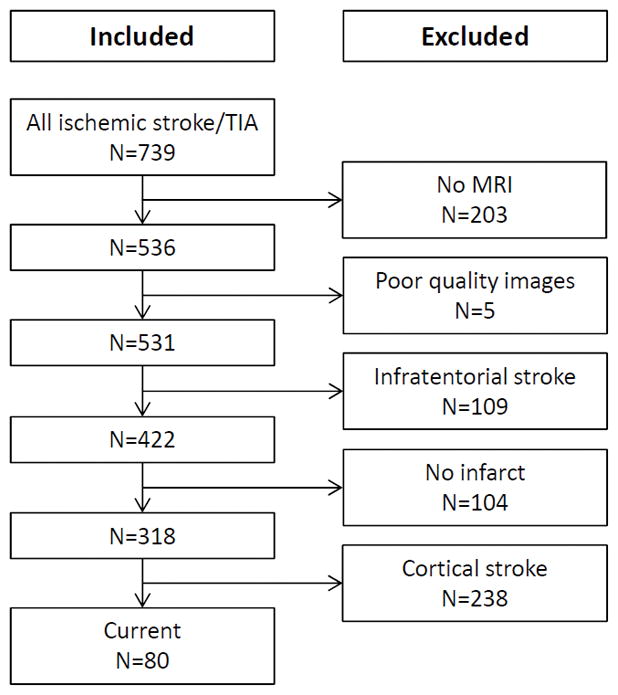

Figure 1 summarizes the flow chart of patient inclusion. Of screened patients with anterior circulation ischemic stroke, 80 (25%) patients had an SSI and were included in our analyses. Data was complete in included patients for all variables except for the 90-day mRS (n=74) as 6 patients were lost to follow up. None of the included patients had a recurrent stroke during the study period. Only one patient had an SSI with a diameter exceeding 20 mm (maximal diameter 22 mm; infarct volume 9.7 mL). Clinical presentations (all patients, n=80) were pure motor (n=39 [49%]), pure sensory (n=6 [8%]), sensorimotor (n=6 [8%]), ataxic-hemiparesis (n=3 [4%]), dysarthria-clumsy hand (n=5 [6%]), atypical lacunar (n=21 [26%]). There was no difference in the distribution of lacunar syndromes when stratified by the presumed SSI etiology (SVD related vs. non-SVD related; p=0.777), WMH lesion burden (Fazekas 0–3 vs. 4–6; p=0.934), and outcome at 90 days (mRS 0–2 vs. 3–6; Supplemental Table I; p=0.815). The baseline characteristics of the study population as stratified by WMH severity are summarized in the Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patient inclusion.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics (unadjusted) of the studied patient population as stratified by white matter hyperintensity severity

| Characteristics | All patients (n=80) | Fazekas 0–3 (n=43) | Fazekas 4–6 (n=37) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 67 (12) | 63 (17) | 78 (19) | <0.001 |

| Female sex | 37 (46%) | 18 (42%) | 19 (51%) | 0.501 |

| Admission NIHSS | 3 (4) | 3 (4) | 5 (8) | 0.064 |

| Preadmission mRS | 0 (1) | 0 (1) | 0 (3) | 0.026 |

| HbA1c, % | 6.0 (1.1) | 6.0 (1.2) | 6.0 (1.0) | 0.526 |

| Infarct volume, mL | 0.8 (0.8) | 0.6 (1.1) | 0.8 (2.3) | 0.043 |

| Admission glucose, mg/dL | 113 (37) | 116 (63) | 109 (54) | 0.509 |

| Admission creatinine, mg/dL | 0.96 (0.19) | 0.97 (0.38) | 0.96 (0.37) | 0.765 |

| LDLc | 103 (20) | 111 (47) | 81 (49) | 0.002 |

| Preadmission medications | ||||

| Statin | 42 (53%) | 21 (49%) | 21 (57%) | 0.509 |

| Antihypertensive | 52 (65%) | 23 (54%) | 29 (78%) | 0.033 |

| Antiglycemic | 23 (29%) | 11 (26%) | 12 (32%) | 0.622 |

| Antiplatelets | 48 (60%) | 24 (56%) | 24 (65%) | 0.495 |

| Oral anticoagulant | 4 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (11%) | 0.042 |

| Preexisting risk factors | ||||

| Hypertension | 57 (71%) | 25 (58%) | 32 (87%) | 0.006 |

| Dyslipidemia | 49 (61%) | 27 (63%) | 22 (60%) | 0.820 |

| Diabetes | 27 (34%) | 14 (33%) | 13 (35%) | 0.817 |

| Prior stroke or TIA | 20 (25%) | 8 (19%) | 12 (32%) | 0.198 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 5 (6%) | 1 (2%) | 4 (11%) | 0.176 |

| Coronary artery disease | 18 (23%) | 6 (14%) | 12 (32%) | 0.062 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 8 (10%) | 3 (7%) | 5 (14%) | 0.461 |

| Current tobacco use | 19 (24%) | 15 (35%) | 4 (11%) | 0.017 |

| Alcohol abuse | 9 (11%) | 6 (14%) | 3 (8%) | 0.494 |

| Final CCS stroke mechanism | ||||

| Large artery atherosclerosis | 6 (8%) | 3 (7%) | 3 (8%) | 1.000 |

| Cardio-aortic embolism | 15 (19%) | 6 (14%) | 9 (24%) | 0.264 |

| Small artery occlusion | 35 (44%) | 21 (49%) | 14 (38%) | 0.371 |

| Other determined cause | 6 (8%) | 3 (7%) | 3 (8%) | 1.000 |

| Undetermined cause | 18 (23%) | 10 (23%) | 8 (22%) | 1.000 |

| Thrombolysis with rtPA | 9 (11%) | 4 (9%) | 5 (14%) | 0.726 |

| Discharge mRS | 1 (2) | 1(2) | 3 (3) | 0.004 |

| Good 90-day outcome (n=74) | 55 (74%) | 37 (88%) | 18 (56%) | 0.003 |

CCS=Causative Classification System; HbA1c=glycated hemoglobin A1c; LDLc=low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; mRS=modified Rankin Scale; NIHSS=National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; rtPA=recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator. Data are n (%) or median (interquartile range).

The WMH lesion burden is independently associated with the SSI volume

Overall, there was a high correlation between the infarct volumes obtained by the two raters (r=0.944, p<0.001). Bland–Altman analyses indicated only minimal bias toward smaller infarct volumes of rater 1 (inexperienced) vs. rater 2 (experienced): bias −0.055 mL; 95 %-CI −0.138 to 0.027 mL; limits of agreement −0.400, 0.290 (not shown); demonstrating high inter-rater agreement.

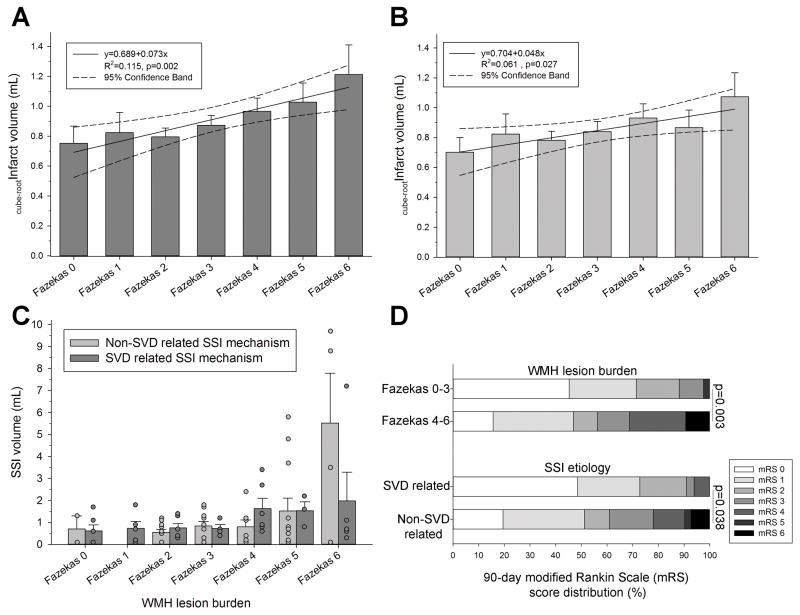

In unadjusted analyses, the infarct volume was not associated with age, patient sex, preadmission medications, preexisting risk factors, treatment with rtPA, CCS stroke mechanism, admission laboratory values (glucose, creatinine, HbA1c, LDLc), or preadmission mRS (p>0.05 each, not shown). Table 2 summarizes the correlation between the SSI volume and imaging markers as well as the NIHSS and mRS. Overall, worse WMH burden was associated with both greater maximal (p=0.002) as well as mean (p=0.027) cube-root transformed SSI volume (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Correlation of imaging markers, NIHSS, and mRS with the small subcortical infarct (SSI) volume

| Covariate | Spearman’s rho | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Total Fazekas score | r=.253 | 0.023 |

| Periventricular Fazekas score | r=.262 | 0.019 |

| Subcortical Fazekas score | r=.198 | 0.078 |

| Admission NIHSS | r=.340 | 0.002 |

| Discharge NIHSS | r=.407 | 0.001 |

| Admission mRS | r=−.076 | 0.503 |

| Discharge mRS | r=.427 | <0.001 |

| 90-day mRS (n=74) | r=.411 | <0.001 |

mRS=modified Rankin Scale; NIHSS=National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale.

Figure 2.

There was a significant linear association between increasing WMH lesion burden and SSI volumes both when considering the (A) maximal SSI volume as well as (B) mean SSI volume (linear regression with 95% confidence intervals; infarct volumes cube-root transformed). (C) There was no difference in the association between the maximal SSI volume and WMH burden in patients with small vessel disease (SVD) vs. non-SVD related small subcortical infarct (SSI) etiology as determined according the Causative Classification System (p=0.299; ANCOVA conducted on cube-root transformed SSI volumes but for better comparison with clinical observations the non-transformed infarct volumes are shown in this panel). Number of subjects (n) per Fazekas category (SVD/non-SVD mechanism): 0 (n=6/2), 1 (n=5/0), 2 (n=6/10), 3 (n=4/10), 4 (n=6/7), 5 (n=3/12), 6 (n=5/4). (D) Between group differences in the 90-day outcome when stratified according to WMH lesion burden (top) and SSI etiology (bottom), respectively (χ2-test). Bars are mean±S.E.M.

On multivariable linear regression WMH burden but not SSI etiology were significantly associated with the maximal (cube-root transformed) SSI volume after adjustment for pertinent variables (p<0.01; Table 3). Repeating all analyses entering the mean (cube-root transformed) SSI volume as independent variable did not meaningfully change the independent association of WMH with the SSI extent (model 1: Coefficient 0.27; 95% CI 0.01 to 0.09; p=0.011; model 2: Coefficient 0.29; 95% CI 0.02 to 0.10; p=0.006; not shown).

Table 3.

Multivariable linear regression analyses of factors independently associated with the cube-root transformed infarct volume

| Independent variable | Coefficient (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | ||

| WMH lesion burden | 0.072 (0.027 to 0.118) | 0.002 |

|

| ||

| Model 1* | ||

| WMH lesion burden | 0.076 (0.031 to 0.120) | 0.001 |

| Random glucosea | 0.121 (0.014 to 0227) | 0.027 |

|

| ||

| Model 2* | ||

| WMH lesion burden | 0.073 (0.029 to 0.117) | 0.002 |

| Random glucosea | 0.124 (0.024 to 0.224) | 0.016 |

| Admission NIHSSa | 0.146 (0.047 to 0.244) | 0.004 |

| Preadmission mRS | −0.080 (−0.152 to −0.009) | 0.029 |

rtPA use, age, small subcortical infarct subtype as well as history of hypertension and atrial fibrillation were not retained in the model.

:cube-root transformed.(15) Note: R2=.115 for the unadjusted analysis, R2=.170 for Model 1, R2=.285 for Model 2.

Clinical and imaging characteristics associated with SSI etiology and multiple SSI

Using the CCS system we categorized the SSI etiology as SVD vs. non-SVD related. In univariable analyses there was no difference in the clinical characteristics of patients with SVD related SSI vs. patients with non-SVD related SSI (p>0.05 each) except that patients with non-SVD related SSI were older (72±12 vs. 64±12 years; p=0.002). Although there was a trend towards a greater WMH lesion burden in patients with non-SVD related SSI this did not reach statistically significance (3.6±1.5 vs. 2.8±2.0; Mann-Whitney U p=0.064). Similarly, the difference between the prevalence of atrial fibrillation in non-SVD vs. SVD only approached significance (11% vs. 0%, p=0.064). Interestingly, more than one SSI was observed in 26 (33%) patients (all of which were located in the anterior circulation), yet the presence of multiple SSI was not associated with the final outcome (Table 4). Details regarding factors associated with multiple SSI are provided as supplemental information.

Table 4.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis with backward elimination of factors independently associated with a poor 90-day (3–6)

| Independent variable | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Model 1*,† | ||

| WMH lesion burden | 1.80 (1.18–2.76) | 0.007 |

| Non-SVD SSI mechanism | 6.51 (1.52–27.94) | 0.012 |

|

| ||

| Model 2*,†,‡ | ||

| WMH lesion burden | 2.28 (1.04–4.99) | 0.040 |

| Pre-admission mRS score, per point | 8.96 (2.65–30.27) | <0.001 |

| Infarct volume, per mL | 1.98 (1.14–3.44) | 0.016 |

| Age, per year | 0.91 (0.82–1.01) | 0.063 |

| Non-SVD SSI mechanism | 9.20 (1.04–81.39) | 0.046 |

Hosmer-Lemeshow for model 1: χ2=7.758, p=0.457. Hosmer-Lemeshow for model 2: χ2=3.059, p=0.931.

Entering the infarct volume as mean or total infarct volume did not meaningfully change the results, respectively.

The interaction term of white matter hyperintensity (WMH) lesion burden x infarct volume and presence of multiple SSI were not retained. Finally, entering large artery atherosclerosis, cardioaortic embolism, and small arterial occlusion in lieu of the non-small vessel disease (SVD) small subcortical infarct (SSI) mechanism did not meaningfully change the models whereby presence of SVD-related SSI etiology was associated with a favorable outcome (p<0.05 in each model).

The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score was not retained in model 2. Further, restricting the analysis to patients with a modified Rankin Scale (mRS) of <6, did not meaningfully change the results.

WMH lesion burden is independently associated with the 90-day outcome after a SSI

Patients with severe WMH (p=0.003) and those with non-SVD related stroke etiology (p=0.038) had significantly worse 90-day outcomes (Figure 2D). After adjustment, WMH severity (p=0.007) and SSI etiology (p=0.012) remained independently associated with a poor 90-day outcome in model 1 (Table 4). After additional adjustment for the admission NIHSS, preadmission mRS, volume, and age, the WMH severity (p=0.04), preadmission mRS (p<0.001), SSI volume (p=0.016), and non-SVD SSI mechanism (p=0.046) were independently associated with the outcome (model 2). When we conducted sensitivity analyses restricted to the patients with available 90-day mRS (n=74) the results did not meaningfully change (Supplemental Table II).

DISCUSSION

The main findings of our study are that greater WMH burden is independently associated with larger SSI infarct volumes as well as a poor 90-day outcome after an SSI. In addition, we found that non-SVD etiology is associated with a worse prognosis in SSI patients.

The observation that a non-SVD stroke etiology was associated with a poor 90-day outcome in our cohort highlights the importance of carefully determining the underlying cause of an SSI. Yet, while our finding is intuitively expected and possibly related to their underlying worse large artery and cardiac health (as indicated by the frequent presence of a stroke mechanism related to cardioaortic embolism and large artery atherosclerosis); the overall association of these factors with the outcome in our cohort was weak, none of these patients suffered a recurrent stroke (a frequent concern) (22), and restricting the analyses to patients that were alive by day 90 did not meaningfully change our results. Hence, probably more important outcome predicting variables in SSI may be the pre-existing functional reserve. In this respect the WMH lesion burden, which is thought to represent a marker of general brain health that has been associated with cognitive decline and dementia (1,8,23,24) is of particular interest. Accordingly, future studies investigating the association between WMH and outcome among patients with SSI may benefit from including detailed neuropsychological evaluations. This may help understand the possible contribution of pre-existing cognitive sequelae, which are not readily detected by standard stroke scales such as the mRS and NIHSS (15) on functional outcome and disability.

It has previously been shown that distinct lacunar syndromes such as dysarthria-clumsy-hand and pure sensory syndrome are associated with better outcomes (25,26). Although, we also found that these syndromes were more frequently represented in the group of patients with a good 90 day outcome there was no overall difference in the distribution of lacunar syndromes and outcome or outcome-prediction variables such as the WMH and SSI-etiology. Nevertheless, given our modest sample size results should be interpreted cautiously and future studies including larger sample sizes will be required to draw firm conclusions.

One mechanism by which WMH may contribute to a worse outcome relates to its association with larger infarct volumes. Indeed, a key finding of our study was that the WMH is a strong, independent predictor of the infarct volume consistent with prior investigations in large hemispheric strokes (9,10). Potential mechanisms by which WMH may increase SSI volume could be related to systemic phenomena such as increased hypercoagulability (27), platelet activation (28), inflammatory processes (29), as well as differences in the genetic background of affected patients (30) that contribute to overall worse ischemia. Rarefaction of the subcortical small arteriolar and capillary bed may result in chronic subcortical hypoperfusion causing more severe ischemia in the event of an SSI (31). Furthermore, vascular rarefaction likely results in dependence of a larger area of tissue on blood supply from the remaining end-arteries and arterioles. Thus, whether these hypothesized phenomena contribute to greater SSI volumes in patients with severe WMH lesion burden (and if so to what degree) remains to be clarified in future studies.

Irrespective of the underlying cause, the association between WMH burden and greater infarct volume is noteworthy because SSI-size has been associated with a poor outcome such as in the Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Strokes (SPS3) trial (4). Hence, our results not only underscore the importance of SSI size as an independent predictor of the outcome but extend on these prior findings by identifying the WMH as an important factor that negatively impacts the 90-day outcome in the SSI population. Although our results should be interpreted cautiously given the retrospective study design and modest sample size they are, nevertheless, further supported by a recent analysis of the SPS3 cohort showing that the functional outcome was predicted by several clinical variables that have been associated advancing age, depression, and cognitive impairment—factors that are strongly associated with WMH severity (1,8,32). Accordingly, our results adds to the notion that WMH may represent an easily accessible imaging marker of overall brain health (1) that should be considered as a covariate in future analyses investigating functional outcome after SSI.

Strengths of the present study include a well-characterized, homogenous patient population and the collection of extensive clinical information. Furthermore, we adjusted our analyses for key factors that have been associated with a poor post-stroke outcome including the use of blinded planimetrically determined infarct volumes.

Limitations of our study relate to restriction of analyses to anterior circulation infarcts and it remains to be shown whether the noted associations also extend to posterior circulation ischemic strokes. The overall number of included patients was modest but consistent with the sample size of prior investigations of SSI (3,33,34); and to our knowledge the only study utilizing CCS-based stroke classification which has the major advantage that it minimizes rater bias by integrating multiple aspects of ischemic stroke evaluation in a probabilistic and objective manner and it is increasingly used in scientific investigations, which allows for more reliable comparison of our findings with other investigations using the same classification system. Nevertheless, a possible limitation of the CCS relates to the fact that it may incorrectly classify some patients with multiple SSI to have a non-SVD related stroke mechanism, which may not be uniformly the case (12,35). We did not conduct a detailed assessment of the SSI location and lesion pattern, which may provide additional insight into SSI pathophysiology (36,37). Further, consistent with the definition of SSI, infarct volumes were overall small, which may result in overproportional impact of measurement errors as compared to large arterial infarctions. However, we demonstrate that inter-rater reliability was high with a bias of <1% of the average lesion size. Lastly, given our retrospective research question and the relatively small sample size the power of our analyses is limited and observations should only be considered hypothesis generating. Accordingly, further prospective study is required to corroborate our findings.

In conclusion, our results indicate that a greater WMH burden is independently associated with a larger infarct volume as well as a worse 90-day outcome after an SSI. In addition, we found that a non-SVD etiology is associated with a worse prognosis in SSI patients. Studies aimed at investigating SSI pathophysiology and related outcomes may benefit from considering the pre-existing WMH lesion burden.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

| Johanna Helenius | Data acquisition, interpretation of data, drafting the article, and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content |

| Yunis Mayasi | Data acquisition, interpretation of data, and critical revision of the manuscript |

| Nils Henninger | Study concept and design, data acquisition, statistical analysis, interpretation of data, and critical revision of the manuscript |

DISCLOSURES/CONFLICTS OF INTERESTS/SOURCES OF FUNDING

Dr. Henninger is supported by K08NS091499 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke of the National Institutes of Health. All other authors report no disclosures or conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Wardlaw JM, Smith C, Dichgans M. Mechanisms of sporadic cerebral small vessel disease: insights from neuroimaging. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:483–97. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70060-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jeong HG, Kim BJ, Yang MH, Han MK, Bae HJ. Neuroimaging markers for early neurologic deterioration in single small subcortical infarction. Stroke. 2015;46:687–91. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.007466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim BJ, Lee DH, Kang DW, Kwon SU, Kim JS. Branching patterns determine the size of single subcortical infarctions. Stroke. 2014;45:1485–7. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.004720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asdaghi N, Pearce LA, Nakajima M, et al. Clinical correlates of infarct shape and volume in lacunar strokes: the Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Strokes trial. Stroke. 2014;45:2952–8. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.005211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Del Bene A, Makin SD, Doubal FN, Inzitari D, Wardlaw JM. Variation in risk factors for recent small subcortical infarcts with infarct size, shape, and location. Stroke. 2013;44:3000–6. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.002227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nah HW, Kang DW, Kwon SU, Kim JS. Diversity of single small subcortical infarctions according to infarct location and parent artery disease: analysis of indicators for small vessel disease and atherosclerosis. Stroke. 2010;41:2822–7. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.599464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim DE, Choi MJ, Kim JT, et al. Two different clinical entities of small vessel occlusion in TOAST classification. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2013;115:1686–92. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pantoni L. Cerebral small vessel disease: from pathogenesis and clinical characteristics to therapeutic challenges. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:689–701. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henninger N, Khan M, Zhang J, Moonis M, Goddeau RJ. Leukoaraiosis predicts cortical infarct volume after distal middle cerebral artery occlusion. Stroke. 2014;45:689–95. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.002855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.HENNINGER N, Lin E, Haussen DC, et al. Leukoaraiosis and sex predict the hyperacute ischemic core volume. Stroke. 2013;44:61–7. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.679084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fazekas F, Enzinger C, Schmidt R, et al. MRI in acute cerebral ischemia of the young: the Stroke in Young Fabry Patients (sifap1) Study. Neurology. 2013;81:1914–21. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000436611.28210.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ay H, Benner T, Arsava E, et al. A computerized algorithm for etiologic classification of ischemic stroke: the Causative Classification of Stroke System. Stroke. 2007;38:2979–84. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.490896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisher CM. Lacunar strokes and infarcts: a review. Neurology. 1982;32:871–6. doi: 10.1212/wnl.32.8.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bruno A, Akinwuntan AE, Lin C, et al. Simplified modified Rankin scale questionnaire: reproducibility over the telephone and validation with quality of life. Stroke. 2011;42:2276–9. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.613273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helenius J, Henninger N. Leukoaraiosis Burden Significantly Modulates the Association Between Infarct Volume and National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale in Ischemic Stroke. Stroke. 2015;46:1857–63. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.009258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim GM, Park KY, Avery R, et al. Extensive leukoaraiosis is associated with high early risk of recurrence after ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2014;45:479–85. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.003004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolf M, Sauer T, Kern R, Szabo K, Hennerici M. Multiple subcortical acute ischemic lesions reflect small vessel disease rather than cardiogenic embolism. J Neurol. 2012;259:1951–7. doi: 10.1007/s00415-012-6451-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wardlaw JM, Smith EE, Biessels GJ, et al. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:822–38. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70124-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fazekas F, Chawluk J, Alavi A, Hurtig H, Zimmerman R. MR signal abnormalities at 1. 5 T in Alzheimer's dementia and normal aging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;149:351–6. doi: 10.2214/ajr.149.2.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haussen DC, Henninger N, Kumar S, Selim M. Statin use and microbleeds in patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2012;43:2677–81. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.657486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turetsky A, Goddeau RP, Henninger N. Low Serum Vitamin D Is Independently Associated with Larger Lesion Volumes after Ischemic Stroke. Journal of Stroke & Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2015;24:1555–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lovett JK, Coull AJ, Rothwell PM. Early risk of recurrence by subtype of ischemic stroke in population-based incidence studies. Neurology. 2004;62:569–73. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000110311.09970.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown WR, Moody DM, Thore CR, Challa VR, Anstrom JA. Vascular dementia in leukoaraiosis may be a consequence of capillary loss not only in the lesions, but in normal-appearing white matter and cortex as well. J Neurol Sci. 2007;257:62–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grau-Olivares M, Arboix A, Bartres-Faz D, Junque C. Neuropsychological abnormalities associated with lacunar infarction. J Neurol Sci. 2007;257:160–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arboix A, Bell Y, Garcia-Eroles L, et al. Clinical study of 35 patients with dysarthria-clumsy hand syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:231–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arboix A, Garcia-Plata C, Garcia-Eroles L, et al. Clinical study of 99 patients with pure sensory stroke. J Neurol. 2005;252:156–62. doi: 10.1007/s00415-005-0622-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tomimoto H, Akiguchi I, Wakita H, Osaki A, Hayashi M, Yamamoto Y. Coagulation activation in patients with Binswanger disease. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:1104–8. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.9.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iwamoto T, Kubo H, Takasaki M. Platelet activation in the cerebral circulation in different subtypes of ischemic stroke and Binswanger's disease. Stroke. 1995;26:52–6. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mitaki S, Nagai A, Oguro H, Yamaguchi S. C-reactive protein levels are associated with cerebral small vessel-related lesions. Acta Neurol Scand. 2016;133:68–74. doi: 10.1111/ane.12440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Markus H. Genes, endothelial function and cerebral small vessel disease in man. Exp Physiol. 2008;93:121–7. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.038752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown W, Moody D, Thore C, Challa V, Anstrom J. Vascular dementia in leukoaraiosis may be a consequence of capillary loss not only in the lesions, but in normal-appearing white matter and cortex as well. J Neurol Sci. 2007;257:62–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dhamoon MS, McClure LA, White CL, Lakshminarayan K, Benavente OR, Elkind MS. Long-term disability after lacunar stroke: secondary prevention of small subcortical strokes. Neurology. 2015;84:1002–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phan TG, van der Voort S, Beare R, et al. Dimensions of subcortical infarcts associated with first- to third-order branches of the basal ganglia arteries. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;35:262–7. doi: 10.1159/000348310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seifert T, Enzinger C, Storch MK, Pichler G, Niederkorn K, Fazekas F. Acute small subcortical infarctions on diffusion weighted MRI: clinical presentation and aetiology. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:1520–4. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.063594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wolf ME, Sauer T, Kern R, Szabo K, Hennerici MG. Multiple subcortical acute ischemic lesions reflect small vessel disease rather than cardiogenic embolism. J Neurol. 2012;259:1951–7. doi: 10.1007/s00415-012-6451-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang C, Wang Y, Zhao X, et al. Distal single subcortical infarction had a better clinical outcome compared with proximal single subcortical infarction. Stroke. 2014;45:2613–9. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.005634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang X, Pu Y, Liu L, et al. The infarct location predicts the outcome of single small subcortical infarction in the territory of the middle cerebral artery. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23:1676–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2014.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.