Abstract

Background: Published papers reported contradictory results about the correlation between bevacizumab effectiveness and primary tumor location of metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC).

Methods: 740 mCRC patients treated with chemotherapy (CT group) and 244 patients treated with bevacizumab plus chemotherapy as first-line setting (CT + B group) were included. Propensity score analyses were used for patients' stratification and matching. Kaplan-Meier curves with log-rank tests were used to detect different overall survival (OS).

Results: Patients in CT + B group had similar OS comparing with CT group only when the primary tumor located at right-side colon (20.2 for CT + B versus 19.7 months for CT group, p = 0.269). For left-side colon and rectal cancer patients, significantly longer OS were observed in CT + B than CT group.

Conclusion: Our data suggested only patients with left-side colon or rectal cancer could get survival benefit from the addition of bevacizumab to first-line chemotherapy.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, metastasis, prognosis, bevacizumab, and location.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer is a group of distinct diseases rather than a homogeneous one1. The colon can be divided into left and right sides with the splenic flexure as the boundary2. Various evidences suggest that left-side colon cancer differs significantly from right-side colon cancer in terms of risk factors, histological grade, tumor size and metastatic features3, 4. Indeed, different molecular characteristics exist between right-side colon and left-side colon, as well as rectum5. What's more, clinical evidence supports that right-side and left-side colon cancers response differently to palliative chemotherapy, as well as cetuximab4, 6-8. When it comes to anti-angiogenic therapy, Boisen et al. reported that patients with tumors originating from sigmoid colon or rectum had better survival than those from cecum to descending colon when treated with capecitabine and oxaliplatin (CAPEOX) plus bevacizumab (median OS were 23.5 versus 13.0 months), and the survival advantage disappeared when patients were treated with CAPEOX without bevacizumab9. However, Fotios et al. reported a study which failed to validate the correlation since both primary tumor location and bevacizumab use were independent factors in multivariable analyses10, 11. Venook et al. reported that bevacizumab was superior to cetuximab in right-side colon cancer patients12. Given all of these inconsistent results, in this study we evaluated the prognostic impact of primary tumor location on survival of mCRC patients, as well as the predictive value of primary tumor location on bevacizumab effectiveness. We also performed propensity score analyses to reduce the impact of clinical and pathological features which distributed differently between right-side and left-side colon.

Materials and Methods

Data source and patient selection

From January 2005 to December 2013, we retrospectively recruited consecutive patients with histologically proven mCRC at Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, and informed consent was obtained from every patient. Patients who accepted at least three cycles palliative chemotherapy were included. Exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) case history not available; 2) without follow up information; 3) with cetuximab as first-line treatment; 4) with other coexisting malignancy.

Date analyses and statistics

Right-sided colon cancers included those occurring in cecum, ascending colon or transverse colon. Left sided colon cancers included those occurring in descending or sigmoid colon. All patients were grouped into chemotherapy group (CT group) or chemotherapy + bevacizumab group (CT + B group) according to the first-line treatment. We also performed propensity score analyses to adjust for heterogeneity since several clinical and pathological features were not balanced when patients were grouped by primary tumor location. As previously reported13, we performed a 1:1 propensity score analyses by modeling logistic regression with balanceable variables, including gender, mucinous histology, stage at diagnosis and LDH levels. The matching tolerance for propensity score analyses was 0.001. The primary endpoint of this study was overall survival (OS), defined as the time from the establishment of metastatic or recurrent disease to the date of death or the last follow-up. Follow-up information was updated in 30th December 2015. We called all the patients or their family members through the phone numbers they left at our hospital. All statistical analyses were performed with the SPSS software version 22. The differences in survival were compared by Kaplan-Meier analyses and log-rank test. Multivariate analysis using a Cox proportional hazards model was used to test independent significance by backward elimination of insignificant explanatory variables. A two-tailed p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

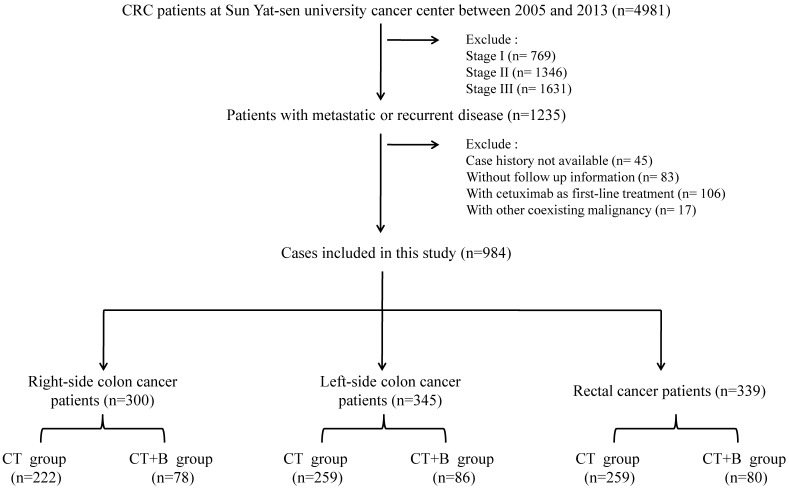

The study flowchart is shown in Figure 1. 984 patients were included in the study. The median follow-up period was 22 months; during this follow-up period, 624 deaths (63.4%) were documented. The median OS of all patients was 21.8 months. The study comprised 740 patients in CT group and 244 patients in CT + B group. The distributions of primary tumor location as well as other characteristics were shown in the Table 1. The distributions of most characteristics were similar, except gender, mucinous histology, stage at diagnosis, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels. In all patients, bevacizumab was associated with longer OS (p=0.001, Figure 2a).

Figure 1.

The flow chart of this study.

Table 1.

The characteristics of patients.

| All patients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Total | Right-side colon | Left-side colon | Rectum | P-value, chi-square |

| Number of patients | 984 | 300 | 345 | 339 | |

| Age | |||||

| ≤50 y | 387 | 120 | 138 | 129 | 0.934 |

| 51-65 y | 387 | 120 | 131 | 136 | |

| >65 y | 210 | 60 | 76 | 74 | |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 637 | 177 | 228 | 203 | 0.036 |

| Female | 347 | 123 | 117 | 107 | |

| Mucinous histology | |||||

| Yes | 158 | 69 | 49 | 40 | <0.001 |

| No | 826 | 231 | 296 | 299 | |

| Stage at diagnosis | |||||

| I | 8 | 1 | 2 | 5 | <0.001 |

| II | 70 | 20 | 20 | 30 | |

| III | 206 | 48 | 56 | 102 | |

| IV | 700 | 231 | 267 | 202 | |

| First line therapy | |||||

| Chemotherapy | 740 | 222 | 259 | 259 | 0.685 |

| Bevacizumab + chemotherapy | 244 | 78 | 86 | 80 | |

| Metastatic organ | |||||

| 1 | 714 | 221 | 251 | 242 | 0.808 |

| >1 | 270 | 79 | 94 | 97 | |

| CEA | |||||

| ≤5 ng/ml | 275 | 81 | 92 | 102 | 0.563 |

| >5 ng/ml | 702 | 217 | 250 | 235 | |

| unknown | 7 | 2 | 3 | 2 | |

| LDH | |||||

| ≤245 U/ml | 702 | 228 | 230 | 244 | 0.035 |

| >245 U/ml | 279 | 71 | 113 | 95 | |

| unknown | 3 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Backbone chemotherapy | |||||

| Oxaliplatin-based | 682 | 213 | 244 | 225 | 0.685 |

| Irinotecan-based | 257 | 73 | 87 | 97 | |

| 5-fluorouracil only | 45 | 14 | 14 | 17 | |

| Bevacizumab beyond first line | |||||

| Yes | 83 | 26 | 31 | 26 | 0.813 |

| No | 901 | 274 | 314 | 313 | |

| Cetuximab treated | |||||

| Yes | 104 | 29 | 40 | 35 | 0.637 |

| No | 880 | 271 | 304 | 304 | |

| Primary tumor resection | |||||

| Yes | 606 | 186 | 220 | 200 | 0.432 |

| No | 378 | 114 | 125 | 139 | |

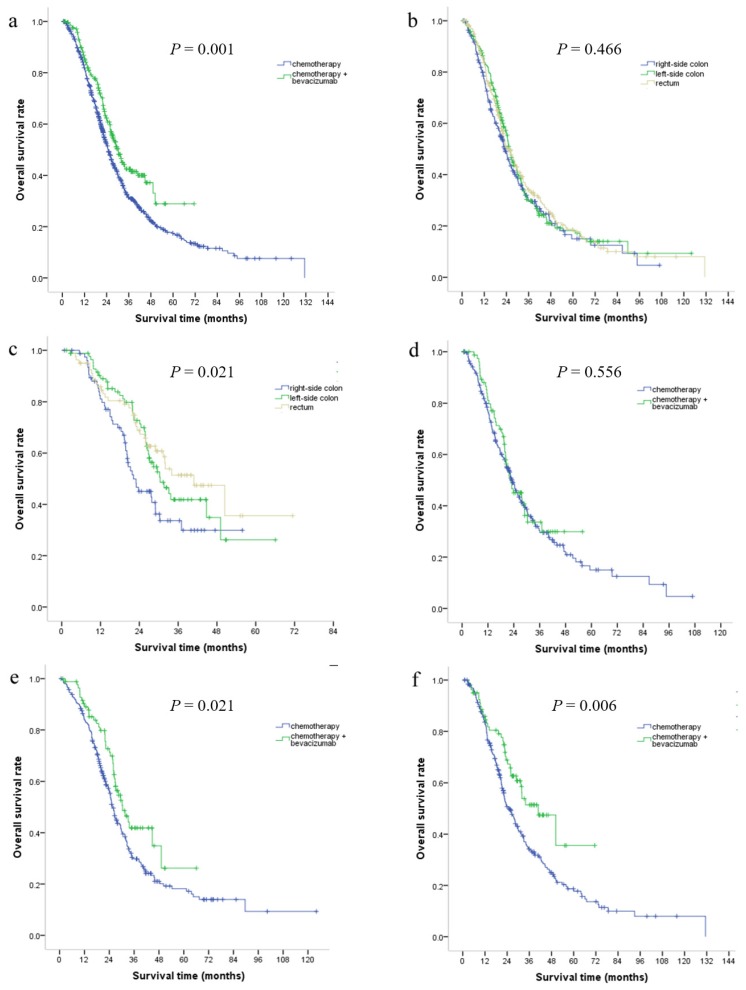

Figure 2.

Overall survival (OS) of all patients treated with and without bevacizumab (a); OS of patients grouped by primary tumor location in chemotherapy (CT) group (b); OS of patients grouped by primary tumor location in chemotherapy plus bevacizumab (CT + B) group (c); OS of patients in CT group and CT + B in patients with right-side colon cancer (d), left-side colon cancer (e) and rectal cancer (f).

No evidence of difference was found in survival outcome for different primary tumor location in CT group. Median OS for right-side colon, left-side colon and rectal cancer patients were 19.7, 22.3 and 21.1 months, respectively (p=0.466, Figure 2b). However, significant differences were detected in OS according to primary tumor location in CT + B group. Median OS for patients with right-side colon, left-side colon and rectal cancer patients were 20.2, 26.3 and 26.4 months, respectively (p=0.021, Figure 2c). The detailed differences of CT + B group in left and right side colon were shown in Table 2. Multivariate analysis including primary tumor location, primary tumor resection, number of metastatic organ, LDH and CEA levels confirmed that primary tumor location was an independent factor (hazard ratio 0.765, 95 % confidence interval 0.607-0.966, p =0.024) in CT + B group.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics in the chemotherapy + bevacizumab group.

| Variable | Right-side colon | Left-side colon | P-value, chi-square |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 78 | 86 | |

| Age | |||

| ≤50 y | 41 | 41 | 0.598 |

| 51-65 y | 25 | 34 | |

| >65 y | 12 | 11 | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 44 | 56 | 0.266 |

| Female | 34 | 30 | |

| Mucinous histology | |||

| Yes | 15 | 14 | 0.684 |

| No | 63 | 72 | |

| Stage at diagnosis | |||

| I | 1 | 9 | 0.207 |

| II | 6 | 24 | |

| III | 26 | 53 | |

| IV | 45 | 86 | |

| Metastatic organ | |||

| 1 | 59 | 61 | 0.597 |

| >1 | 19 | 25 | |

| CEA | |||

| ≤5 ng/ml | 15 | 28 | 0.051 |

| >5 ng/ml | 63 | 56 | |

| unknown | 0 | 2 | |

| LDH | |||

| ≤245 U/ml | 57 | 57 | 0.494 |

| >245 U/ml | 21 | 28 | |

| unknown | 0 | 1 | |

| Backbone chemotherapy | |||

| Oxaliplatin-based | 41 | 49 | 0.304 |

| Irinotecan-based | 37 | 35 | |

| 5-fluorouracil only | 0 | 2 | |

| Bevacizumab beyond first line | |||

| Yes | 16 | 15 | 0.691 |

| No | 62 | 71 | |

| Cetuximab treated | |||

| Yes | 7 | 13 | 0.245 |

| No | 71 | 73 | |

| Primary tumor resection | |||

| Yes | 57 | 67 | 0.585 |

| No | 21 | 19 | |

To further evaluate the predictive value of primary tumor location in regards to bevacizumab effectiveness, we studied whether the treatment benefit of bevacizumab differed among three primary tumor locations. Patients with right-side colon cancer had similar OS (19.7 months vs 20.2 months, p=0.556, Figure 2d) comparing CT group with CT + B group. However, patients with left-side colon cancer could derive benefit from bevacizumab (median OS was 26.3 months for CT+B group and 22.3 months for CT group, p=0.021, Figure 2e). Significant longer OS were also detected in rectal cancer patients when bevacizumab were added (median OS was 26.4 months for CT+B group and 21.1 months for CT group, p=0.006, Figure 2f). The routinely clinical-pathological factors were comparable in those comparisons.

Since gender, mucinous histology, stage at diagnosis and LDH levels were not balanceable, we performed propensity score analyses to adjust for those heterogeneities, as shown in the Table 3. Similar results were observed after matching. 58 right-side colon, 86 left-side colon and 99 rectal cancer patients were included in CT group (total: 243) while 78 right-side colon, 86 left-side colon and 80 rectal cancer patients were included in CT + B group (total: 244). For patients in CT group, median OS for right-side colon, left-side colon and rectal cancer patients were 20.4, 23.1 and 21.2 months, respectively (p=0.800). Patients in CT + B group had a similar OS in comparison with CT group only when the primary tumor located at right-side colon (median OS were 20.2 months for CT + B group versus 20.5 for CT group, p = 0.851). For left-side colon cancer patients, those in CT + B group had longer OS than CT group (26.3 versus 23.1 months, P = 0.021). For rectal cancer patients, significantly longer OS were also observed in CT + B than CT group (26.3 versus 21.1 months, p = 0.014).

Table 3.

The characteristics of patients after propensity score analyses.

| Propensity score-matched patients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Total | Right-side colon | Left-side colon | Rectum | P-value, chi-square |

| Number of patients | 487 | 136 | 172 | 179 | |

| Age | |||||

| ≤50 y | 230 | 67 | 85 | 78 | 0.787 |

| 51-65 y | 176 | 46 | 61 | 69 | |

| >65 y | 81 | 23 | 26 | 32 | |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 302 | 78 | 107 | 117 | 0.348 |

| Female | 185 | 58 | 65 | 62 | |

| Mucinous histology | |||||

| Yes | 81 | 27 | 30 | 24 | 0.295 |

| No | 406 | 109 | 142 | 155 | |

| Stage at diagnosis | |||||

| I | 6 | 1 | 1 | 4 | <0.001 |

| II | 48 | 13 | 11 | 24 | |

| III | 163 | 39 | 47 | 77 | |

| IV | 270 | 83 | 113 | 74 | |

| First line therapy | |||||

| Chemotherapy | 243 | 58 | 86 | 99 | 0.084 |

| Bevacizumab + chemotherapy | 244 | 78 | 86 | 80 | |

| Metastatic organ | |||||

| 1 | 345 | 100 | 115 | 130 | 0.662 |

| >1 | 142 | 36 | 57 | 49 | |

| CEA | |||||

| ≤5 ng/ml | 138 | 31 | 53 | 54 | 0.216 |

| >5 ng/ml | 346 | 105 | 117 | 124 | |

| unknown | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | |

| LDH | |||||

| ≤245 U/ml | 346 | 101 | 114 | 131 | 0.262 |

| >245 U/ml | 140 | 35 | 57 | 48 | |

| unknown | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Backbone chemotherapy | |||||

| Oxaliplatin-based | 190 | 52 | 72 | 66 | 0.903 |

| Irinotecan-based | 257 | 73 | 87 | 97 | |

| 5-fluorouracil only | 40 | 11 | 13 | 16 | |

| Bevacizumab beyond first line | |||||

| Yes | 57 | 18 | 152 | 160 | 0.773 |

| No | 430 | 118 | 20 | 19 | |

| Cetuximab treated | |||||

| Yes | 55 | 13 | 21 | 21 | 0.655 |

| No | 432 | 123 | 151 | 158 | |

| Primary tumor resection | |||||

| Yes | 166 | 43 | 54 | 69 | 0.285 |

| No | 321 | 93 | 118 | 110 | |

Discussion

In this study, we observed that survival was inferior for right-side as compare to left-side colon or rectal cancer patients when they were treated with chemotherapy plus bevacizumab. Since right-side colon cancer has prevalence toward being mucinous type and more advanced disease, we also performed propensity score analyses to reduce the impact of its nature. What's more, in patients treated with chemotherapy plus bevacizumab, we conducted multivariate analysis to confirm that primary tumor location was an independent factor. At last, we compared the survival between patients who accepted chemotherapy alone and chemotherapy plus bevacizumab in patients with right-side colon cancer, as well as left-side colon and rectal cancer.

Several other studies were in line with the present study. Boisen reported the prognostic value of primary tumor location when mCRC patients were treated with CAPEOX plus bevacizumab, and the prognostic value of primary tumor location disappeared when patients were treated with CAPEOX only9. Brule et al. reported that tumor location within the colon is not prognostic in NCIC CO.17 trial, in which patients were treated with cetuximab versus best supportive care, 14. In Brule's study, the the primary tumor location was not with prognostic values for OS (HR 0.96 [0.70-1.31], p = 0.78) or progression-free survival (HR 1.07 [0.79-1.44], p = 0.67). Together, these reports and our study make the interaction between bevacizumab effectiveness and primary tumor location less likely to be a coincidence.

One possible reason underlying the interaction between primary tumor location and bevacizumab effectiveness is that VEGF-A, the target of bevacizumab, is higher expressed in left-side colon and rectum than right-side colon15. Volz et al. also reported that germline polymorphisms related to pericyte maturation, which could predict treatment benefit of bevacizumab, was dependent on primary tumor location16. However, the exact mechanism underlying this interaction remains exclusive.

Our study has several implications. We suggest that investigators should consider the primary tumor location as a stratification factor in designing or reviewing clinical studies involving bevacizumab. In addition, primary tumor location of mCRC should be considered when cetuximab and bevacizumab are compared, since right-side and left-side mCRC patients also respond differently to cetuximab. Indeed, Venook et al. reported that bevacizumab might be superior to cetuximab for right-sided mCRC12. We think their results were not contradicted with our study since we compared chemotherapy plus bevacizumab with chemotherapy only, with first-line cetuximab excluded.

There are several limitations of this study. First, the retrospective nature limited its power. Second, several molecular features were not available, such as kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS) status. Third, we did not compare progression free survival since we could not determine the precise time of tumor progression based on medical records. Those limitations should be considered when interpreting our study.

In conclusion, our data suggest that primary tumor location is a prognostic factor for mCRC patients when treated with bevacizumab, and patients with right-side colon cancer cannot get survival benefit from the addition of bevacizumab to first-line chemotherapy. Further data from randomized trials are needed to test our hypothesis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong, China (2015A030313010), Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou, China (1563000305) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (81272641 and 81572409).

References

- 1.Network CGA. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012;487:330–7. doi: 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiss JM, Pfau PR, O'Connor ES, King J, LoConte N, Kennedy G. et al. Mortality by stage for right- versus left-sided colon cancer: analysis of surveillance, epidemiology, and end results-Medicare data. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4401–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.4414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang W, Li YF, Sun XW, Chen G, Zhan YQ, Huang CY. et al. Correlation analysis between loss of heterozygosity at chromosome 18q and prognosis in the stage-II colon cancer patients. Chin J Cancer. 2010;29:761–7. doi: 10.5732/cjc.010.10059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shen H, Yang J, Huang Q, Jiang MJ, Tan YN, Fu JF. et al. Different treatment strategies and molecular features between right-sided and left-sided colon cancers. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:6470–8. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i21.6470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamauchi M, Morikawa T, Kuchiba A, Imamura Y, Qian ZR, Nishihara R. et al. Assessment of colorectal cancer molecular features along bowel subsites challenges the conception of distinct dichotomy of proximal versus distal colorectum. Gut. 2012;61:847–54. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang F, Bai L, Liu TS, Yu YY, He MM, Liu KY, Right- and left-sided colorectal cancers respond differently to cetuximab. Chinese Journal of Cancer; 2015. p. 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.von Einem JC, Heinemann V, von Weikersthal LF, Vehling-Kaiser U, Stauch M, Hass HG. et al. Left-sided primary tumors are associated with favorable prognosis in patients with KRAS codon 12/13 wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer treated with cetuximab plus chemotherapy: an analysis of the AIO KRK-0104 trial. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2014;140:1607–14. doi: 10.1007/s00432-014-1678-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Price TJ, Beeke C, Ullah S, Padbury R, Maddern G, Roder D. et al. Does the primary site of colorectal cancer impact outcomes for patients with metastatic disease? Cancer. 2015;121:830–5. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boisen MK, Johansen JS, Dehlendorff C, Larsen JS, Osterlind K, Hansen J. et al. Primary tumor location and bevacizumab effectiveness in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:2554–9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loupakis F, Yang D, Yau L, Feng S, Cremolini C, Zhang W. et al. Primary tumor location as a prognostic factor in metastatic colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015:107. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He WZ, Xia LP. RE: Primary Tumor Location as a Prognostic Factor in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015:107. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alan P, Venook DN, Impact of primary (1º) tumor location on overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) in patients (pts) with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC): Analysis of CALGB/SWOG 80405 (Alliance) J Clin Oncol; 2016. p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park JS, Choi GS, Jun SH, Park SY, Kim HJ. Long-term outcomes after laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery for rectal cancer: a propensity score analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:2633–40. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-2981-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brule SY, Jonker DJ, Karapetis CS, O'Callaghan CJ, Moore MJ, Wong R. et al. Location of colon cancer (right-sided versus left-sided) as a prognostic factor and a predictor of benefit from cetuximab in NCIC CO.17. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:1405–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bendardaf R, Buhmeida A, Hilska M, Laato M, Syrjanen S, Syrjanen K. et al. VEGF-1 expression in colorectal cancer is associated with disease localization, stage, and long-term disease-specific survival. Anticancer Res. 2008;28:3865–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Volz NB, Stintzing S, Zhang W, Yang D, Ning Y, Wakatsuki T. et al. Genes involved in pericyte-driven tumor maturation predict treatment benefit of first-line FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Pharmacogenomics J. 2015;15:69–76. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2014.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]