Abstract

Discrepancies between multiple electronic versions of patient medication records contribute to adverse drug events. Regular reconciliation increases their accuracy but is often inadequately supported by EHRs. We evaluated two systems with conceptually different interface designs for their effectiveness in resolving discrepancies. Eleven clinicians reconciled a complex list of 16 medications using both EHRs in the same standardized scenario. Errors such as omissions to add or discontinue a drug or to update a dose were analyzed. Clinicians made three times as many errors working with an EHR with lists arranged in a single column than when using a system with side-by-side lists. Excessive cognitive effort and reliance on memory was likely a strong contributing factor for lower accuracy of reconciliation. As errors increase with task difficulty, evaluations of reconciliation tools need to focus on complex prescribing scenarios to accurately assess effectiveness, error rate and whether they reduce risk to patient safety.

Introduction

Adverse drug events cause 770,000 injuries or deaths and cost $1.56 to $5.6 billion each year in the United States.1,2 Discrepancies between medications documented in electronic health records (EHR) systems and the actual state of their use by patients contribute significantly to the rate of preventable iatrogenic injuries. Over 25% of inpatient medication errors are due to inaccurate medication lists while errors in prescription medication histories occur in up to 67% of cases.3 The Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT (ONC) made medication reconciliation a core objective of its Meaningful Use (MU) initiative4 in recognition of its importance in reducing the incidence of adverse drug events (ADE) and the Joint Commission declared it to be one of National Patient Safety Goals.5 There is broad consensus that drug therapy errors can be reduced by making a complete, verified account of all medications a patient is actively taking and comparing this true state to lists maintained in one or more EHR systems. These records need to be updated regularly, especially at the time of a hospital admission, discharge or transfer and periodically maintained during ambulatory care. The maintenance process usually involves comparing medication history to the history in institutional records and to current prescription orders, identifying and reconciling discrepancies and documenting changes for future encounters and for other caregivers.6 Discrepancies between multiple lists and divergence from the true state of actively used medications can have serious consequences such as prolonged periods of over- or under-treatment that can only be detected by active surveillance.7,8

Routine reconciliation is becoming more demanding with the steady increase of medication therapy, polypharmacy and the expansion of specialist care that allows more caregivers to write prescriptions for one patient. A nationally representative survey showed that 39% of adults over the age of 65 use five or more medications regularly.9 There is a corresponding rise in the difficulty of reconciling ever longer and more numerous lists from different care institutions and larger teams of providers. Reconciliation is conceptually simple and has been shown to be effective in reducing discrepancies but many clinics and hospitals found it difficult to implement a robust and reliable process with effective electronic tools.10 A recent study that evaluated the rate of inconsistencies and errors in medication lists reported that pharmacists reconciling records in ambulatory EHRs found on average 3.4 clinically important discrepancies per patient record.11

There is strong research and anecdotal evidence from practitioners that the process is not supported well by currently available EHRs and that many find their reconciliation modules difficult to work with and poorly suited for the task. For example, a recent report showed that although vendors have been increasingly adding this functionality to their products in order to achieve meaningful use certification, clinicians in more than a third of the surveyed hospitals continued to use a partially paper-based process at admission, discharge or at ambulatory encounters as they were generally dissatisfied with the provided electronic tools.12

Human factors and usability evaluation methods have recently started being applied to identify specific design constraints and workflow problems that affect the quality of reconciliation.13 Prioritizing recognition over recall, for example, is a common practice used by designers to decrease extraneous cognitive effort,14,15 make interaction less difficult and human performance less error-prone. During recognition, more cues and related information stored in memory are activated than in free recall and therefore the target item (e.g., medication name) can be more easily accessed and used in working memory.16,17 Guidelines and recommended usability principles commonly advise to use this concept in interface design.18 It is of particular significance when clinicians compare medications on two lists for differences and similarities.

As the result of care by many clinicians at different locations, multiple versions of medication lists may be stored on several information systems. What makes reconciliation more difficult is not only the number of medications that need to be reviewed but also the complexity of therapeutic regimens and the extent of detailed dosing instructions that need to be correctly interpreted and updated. While the list length increases the time and effort needed to account for the presence and absence of specific medications, more subtle differences between the same drugs or their generic equivalents present on both lists, such as changes in dose, frequency, route or use instructions, require sustained and focused attention to identify and enter them correctly.19,20 Substitutions of drugs in the same therapeutic class also need to be carefully reviewed by a trained clinician to avoid duplicate therapy.

This intrinsic difficulty is compounded by the need to make multiple comparisons to one or more lists and to the true state often confirmed by the patient or a caregiver. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) estimate that a patient with one chronic disease sees up to four different doctors while those with five or more see an average of 14 different physicians,21 requiring more frequent and complex reconciliation of clinical information between all providers. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that 37% of Americans over the age of 60 take five or more medications and that the average number rises from five to seven at the age of 85.22 Patients with more comorbid conditions then have a higher probability that their medication lists contain errors and are at increased risk for adverse drug events.23

There is a paucity of rigorously designed studies comparing different medication reconciliation practices.24 While some studies have shown the benefits of medication reconciliation technology almost all were done with systems developed in academic institutions, not by major vendors.24 The MARQUIS study reported, for example, that implementing a vendor EHR more than doubled the rate of medication discrepancies in one hospital.25,26 While there are well-designed, commercially available stand-alone systems for reconciliation available they are sparsely used due to the additional expense and difficulties with integration into EHRs that place extra burden on providers.

The majority (60%) of medication histories are shorter than five entries and the effect of list complexity may therefore be obscured in studies that do not stratify observations and results by the difficulty of reconciliation as errors tend to cluster within the subset of long and complex lists.9 Poor performance of suboptimally designed tools and their effect on patient safety may therefore be under-reported and under-studied.

The objective of our study was to investigate the effect of two different design concepts of a reconciliation module on human performance and error during a cognitively complex task. We asked clinicians to reconcile identical, standardized sets of medication lists with two different systems and analyzed the rate and character of observed errors. Our findings may inform the design of interventions and electronic tools that effectively alleviate cognitive burden on clinicians during complex reconciliations and reduce the number of errors leading to adverse events.

Methods

This study was designed as a standardized task scenario in which 11 clinicians performed reconciliation of two electronic lists containing 16 medications each using two different EHR systems in an alternating counterbalanced order to control for a possible learning effect. There were ten identical (including dose and frequency) medication records common to both lists, six were recorded only in EHR 1 and another 6 only in EHR 2 (Table 1). Reconciliation therefore required participants to make 22 drug comparisons: verify the ten identical entries and make a decision about correct updates to the local EHR system (e.g., add, don’t add, discontinue) on the remaining twelve. The test administrator simulated a patient and answered questions about the veracity of each medication. The scenario contained four discrepancies that required participants to make a clinical decision rather than simply verifying that a particular medication was being actively taken by the patient. For example, Lasix, present on both lists (Table 1), required visual verification that the entries were identical in all aspects. When working with EHR 1, there was no action required for Ambien that the patient confirmed to be actively taking; however, on EHR 2, the drug would need to be added. Clonidine PO had to be discontinued when reconciling from EHR 1 since the patient was no longer taking it but no action was required when reconciling from EHR 2.

Table 1.

Correct decisions and actions for reconciliation

| Medication | List | EHR 1 | EHR 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abacavir 300 mg tab 2 oral daily | Both | Verify | Verify |

| Adefovir 10 mg tab 1 oral every other day | Both | Verify | Verify |

| Klonopin (clonazepam) 0.5 mg tab 1 oral bid, prn | Both | Verify | Verify |

| Lamivudine 150 mg 1 oral daily | Both | Verify | Verify |

| Lasix (furosemide) 20 mg 1 po every other day | Both | Verify | Verify |

| MiraLax (polyethylene glycol) 142 mg/ml 17g oral daily, PRN | Both | Verify | Verify |

| Novolog R (insulin regular) 100 unit/ml sc sliding scale. | Both | Verify | Verify |

| Prilosec (omeprazole) 40 mg 1 oral bid | Both | Verify | Verify |

| Raltegravir 400 mg tab 1 oral bid | Both | Verify | Verify |

| Zofran (ondansetron) 4 mg/5ml 5ml oral q8h | Both | Verify | Verify |

| Ambien (zolpidem) 5mg po at bedtime PRN | 1 only | Keep | Add |

| Aspirin 81 mg tab 1 oral daily | 1 only | Keep | Add |

| Clonidine 0.1 mg PO BID | 1 only | D/C | Don’t add |

| Crestor (rosuvastatin) 40mg po daily | 1 only | D/C | Don’t add |

| Lisinopril 40 mg 1 po daily | 1 only | Keep | Add |

| Zoloft (sertraline) 100 mg 1 oral daily | 1 only | Keep | Add |

| Amlodipine 10 mg 1 PO daily | 2 only | Add | Keep |

| Clonidine TTS 0.1 mg 1 patch qweek | 2 only | Add | Keep |

| Humulin 70-30 unit/ml as directed, 34 units qam, 24 units qpm | 2 only | Add | Keep |

| Lipitor (atorvastatin) 40 mg 1 oral daily | 2 only | Add | Keep |

| Tramadol 50 mg 1 oral bid PRN pain | 2 only | Don’t add | D/C |

| Zestril (Lisinopril) 20 MG By Mouth every day | 2 only | Don’t add | D/C |

Both -Medications identical in all aspects were entered on lists in EHR 1 and EHR 2.

1 only or 2 only -Medication entered in one EHR only.

Verify -Compare entries on both lists; no action required if identical.

Add -Enter medication into the local EHR (present only on the remote list, confirmed as taken).

Keep -No action required (medication present only on the local list, confirmed as taken).

D/C -Discontinue in the local EHR (medication present only on the local list, not being taken).

Don’t add -No action required (medication present only on the remote list, not being taken).

Discordant information presented in the scenario is listed in Table 2. The correct state specifies information confirmed by the patient (test administrator) in response to a direct question by the participant. The actions required to bring the medication list to a true state is shown from the perspective of EHR 2 being the local system. Conversely, the actions would be mirrored when EHR 1 was the local system.

Table 2.

Decisions and actions for medication list reconciliation between two EHR systems

| Type | Discrepancy | Correct state | Reconciliation actions on EHR 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Brand vs. generic, dose change | Dose increased from 20 to 40 mg. | Zestril 20 mg (discontinue) Lisinopril 40 mg (add) |

| B | Same medication, change of route | Clonidine 0.1 mg PO bid (not taking), Clonidine 0.1 mg qweek 1 TD patch. |

Clonidine 0.1 mg patch (keep) Clonidine 0.1 mg PO (don’t add) |

| C | Duplicate therapy, same-class statins | Rosuvastatin 40 mg PO qday (not taking) Atorvastatin 40 mg PO qday |

Lipitor 40 mg PO qday (keep), Crestor 40 mg PO qday (don’t add) |

| D | Patient not taking | Tramadol 50 mg PO bid PRN | Tramadol 50 mg PO (discontinue) |

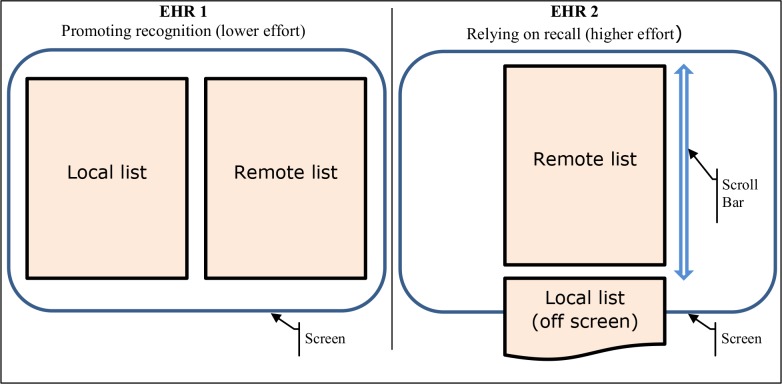

The reconciliation module of EHR 1 had the two lists visible on a single screen, side-by-side in two columns. The lists were also subdivided into therapeutic class sections that were horizontally lined up for direct visual comparison of individual entries within each section. In contrast, EHR 2 was designed with both lists in the same column - the remote list above the local list. Due to their lengths, however, clinicians could only see one at a time as the other was off the screen and required manual scrolling to display. A green highlight would appear over a pair of identical drugs (brand and generic versions) in the two lists on a mouse-over. However, the highlighted drugs could have different doses. A schematic of the basic layout concepts is in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the two layout concepts

Participants were ten physicians and one physician assistant who have worked with EHR 2 daily for at least 6 months, except for two clinicians who had 4 months of similar experience. Most performed reconciliations routinely at least several times a week. None had previously reconciled medications using EHR 1 as the module had only recently been developed and implemented. They were shown its function in a short (1 minute) demonstration before the task started. The selected sample of 11 participants reflects a commonly recommended size for formative usability evaluation studies.27,28

Interactions of participants with the modules were recorded and analyzed with Morae 3.3 suite.29 The number and type of errors in the reconciled list as well as the time to complete tasks were determined. Statistical significance on the difference in the number of errors was evaluated using a non-parametric t-test.

Results

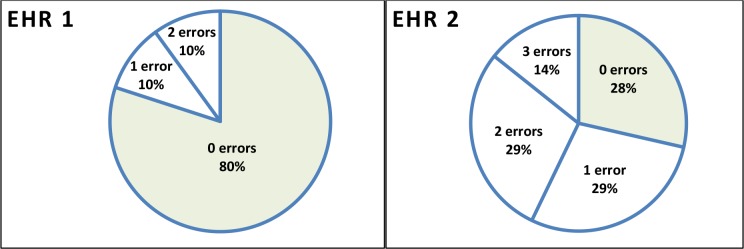

Ten clinicians completed reconciliation using EHR 1 with an average of 0.37 errors per participant (range 0 to 2; group total 3). The mean completion time was 5.5 minutes (range 1.96 to 8.95 minutes). Seven clinicians completed the same task (22 comparisons and decisions) using EHR 2 with an average of 1.29 errors per participant (range 0 to 3 errors; group total 9). The mean completion time was 7.8 minutes (range 3.7 to 9.6 minutes). Difference for the mean number of errors between systems approached significance at p≤ 0.057. Participants made between zero and three errors individually in each task (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Distribution of the number of errors per participant

Seven of the 12 errors observed during both variants of the task had similar characteristics and were aligned with discrepancy types A and B (from Table 2) and two with type C. Descriptions of the errors are in Table 3.

Table 3.

Type and frequency of observed errors

| Type | Discrepancy | EHR 1 | EHR 2 | Comments (number of instances) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Brand vs. generic, dose change | 0 | 4 | Both entries were discontinued (2). Entries were not verified for currently active dose (2). |

| B | Same medication, change of route | 1 | 2 | PO drug not discontinued – duplicate therapy (2). Wrong route (1) |

| C | Duplicate therapy, same-class statins | 0 | 2 | Crestor not discontinued – duplicate therapy (2). |

| Other | Ambien Humulin (insulin) Zoloft | 2 | 1 | Failed to add missing drugs to local list (3). |

| Total | 3 | 9 |

Observed strategies and workarounds

Clinicians working with EHR 2 used several strategies to compensate for the inability to see drugs on both lists at the same time for comparison. The most common approach was to scroll up and down for each drug: they asked the patient to verify a medication as being taken, located a matching entry on the local list (below) and updated or added as necessary. Alternatively, they would go through the remote list first in its entirety, added medications not identified by a green highlight as matched on the local list, reviewed the updated local list with the patient and adjusted the dose or discontinued the drug. Additional scrolling back to the remote list (above) was often necessary to compare doses, additional instructions and start dates. Clinicians recalled from memory which drugs have been already confirmed to speed up the process and to check whether there was a dose, brand-to-generic or route change.

Another strategy was to remove medications not being taken from both lists first and then review them one-by-one for differences, again scrolling for each comparison. Two clinicians explained that after a consolidation of the two lists (i.e., adding all drugs from the remote lists that did not highlight as a “match”) they left the module and completed the task using the EHR medication list screen.

Discussion

We evaluated two EHRs with differently conceptualized modules for medication reconciliation using a complex scenario and found a clear trend for higher accuracy and shorter completion time for one system. The key design difference was in the form of visual presentation of medication lists. EHR 1 showed lists side-by-side and organized all medications into subsections by therapeutic class that were horizontally lined up for direct visual comparison. EHR 2 presented the lists one above the other in a single column layout, with green highlighting of medications matched on both lists when the mouse hovered over an entry.

The effectiveness of appropriate cognitive support for the comparison task was evident in better performance of clinicians using EHR 1 and was also underscored by the fact that the participants had no prior training or experience with the module except for a short demonstration. In contrast, most participants worked daily with EHR 2 for six months or more and reconciled medications at least several times per week even at places where medical assistants and nurses performed the task routinely.

The most frequently observed error was a dosing error. The dose increase in the scenario was often not correctly interpreted and the locally recorded drug was either discontinued and the remote one not added or the dose difference was noticed and records were not compared to verify which one was active. Clinicians revealed in debriefings that those who relied on the green highlight function of EHR 2 did not realize that only the generic ingredient and route were checked automatically, not the dose. Clinicians who did not rely on the highlighting compared the entries directly and verified the right dose with the patient, as they did when using EHR 1. The ensuing medical error would probably result in therapy with an incorrect dose or no treatment of the condition for which it was prescribed. Although mandatory training for EHR 2 likely covered the meaning and function of the highlight, several participants were not aware of it and at least two assumed that a complete match included the dose was indicated. Problems and errors due to screen artifacts and visual cues that are not intuitive or may be misleading are rarely avoided by mandating more complete and thorough training, especially for very complex software where learning and skill develops over time with repeated use and under real work conditions.

Errors where there was a difference in route were observed on both systems. In EHR 2, clinicians looking at the second list had to recall correctly the entire medication instructions from the first list that was scrolled off the screen. Two participants made an error by recalling only the drug and dose and not the route and another one discovered the discrepancy only on a second review and corrected it. Several clinicians working with EHR 1 commented on the fact that the patch version of clonidine was placed in a different drug class section than the oral version, confounding the visual comparison of drugs within categories.

Duplicate therapy errors occurred only when participants worked with EHR 2. Clinicians correctly identified Lipitor as missing from the local list and added it but two failed to discontinue the existing Crestor. The duplicate therapy alert was not triggered at that point, allowing the possibility of an adverse event due to duplicate statin therapy.

All clinicians correctly revised the list after asking the patient about taking Tramadol and therefore there were no errors where the patient was not taking a medication and the medication needed to be removed from the active list. The other three errors resulted from clinicians not noticing the absence of a medication on the local list and failed to add it from the remote list.

Workarounds and interaction practices not originally envisioned by designers often indicate a poor fit of a tool to the task.30 In safety-critical work, unintended actions and re-purposed screen artifacts (e.g., free-text entries with content other than expected) also mean that some safeguards may be circumvented and new errors may be introduced.31,32

In debriefings and interviews at the end of each session, clinicians recalled strategies and workarounds they use to make the reconciliation easier and faster under the constraints of a typical daily workload. For example, at one clinic, medical assistants were hired to reconcile the lists for all physicians as part of that institution’s transition to a new system. Their work was checked for accuracy by pharmacists who compared a printed version of each reconciled list for all patients at the clinic to an electronic version on the screen. This practice has been reported by other places that found their electronic tools to be lacking in effectiveness and usability.12,33 However, as two participants noted, off-loading routinely reconciliation to medical assistants to save time before visits is always risky as staff without adequate medical training would “fail to see that treating with Atorvastatin and Crestor would be duplicate therapy” and that their work would have to be double-checked for errors by a physician or a pharmacist. One participant explained that “I usually take a piece of paper, write the dose and date down and check it like that, because the most recent one is probably current; I wish I could see them both and not to have to scroll.”

The extra demand on attention was apparent by repeated checking of the same drug pair and multiple scrolling, especially for medications with similar names such as Lamivudine, Clonidine or Lisinopril when the clinician also had to recall which drug has already been viewed. Duplication of effort and extra time to complete was a common result of workarounds: in the words of one physician, “I would first ask you (patient) what you take and then go back up the list again.” Participants commented that this is “too cumbersome, it would be much better if I could see them side-by-side,” or that “this is a nightmare, I can’t see both.”

The differences in layout represented higher (one column) and lower (two-column) demand on cognitive effort and attention of clinicians. The one-column design was clearly inferior to the two-column concept. It necessitated repeated memorization and recall of items that may have had only subtle differences (e.g., different dose) or similar names (e.g., clonazepam, clonidine), required more attention and produced errors of omission, substitution and other failures of memory.15,34 When the top list (remote system) had five or six entries, the bottom list of similar length was already partially off the screen and disappeared from view at 12 or 13 entries. The difficulty of comparison would therefore be a problem for a substantial portion of a typical set of patient records in an EHR.

The two-column list allowed perceptual judgments and recognition of items rather than the more difficult recall. Typically, this approach lowers cognitive complexity and produces more accurate results.35,36 Sectioning of a long list of entries into more manageable chunks by drug class also simplifies a difficult lookup task by transforming it into a series of easier comparisons within each category where there usually are no more than four or five entries that are easier to verify visually. One unintended effect of assigning several categories to one drug was that the same medication with different routes could be displayed in different sections. Clonidine oral and transdermal patch, in our scenario, were not matched into the same sections on both lists, causing at least one error and several comments on this discrepancy from clinicians who eventually corrected their mistakes.

Although the length of the lists in this scenario was not typical, complex regimens are not rare in ambulatory medicine. Patients requiring extensive medication therapy also tend to be sicker and more susceptible to adverse drug events. Usability testing requirements for EHRs (such as those required for ONC certification) should more prominently focus on more complex and longer lists to evaluate more accurately the effectiveness of a tested system in preventing reconciliation errors.

Limitations

This was small-scale pilot assessment that will be complemented with a larger study. We have identified a trend in the difference of means of reconciliation errors but the results would have a much more general validity with a larger cohort. We also experienced several technical difficulties with recording test sessions at locations in several hospitals and clinics that produced gaps in analyses and therefore only seven and nine clinicians completed tasks on each tested system. As planned, each participant would have completed the same task on both systems. However, there was no systematic exclusion and therefore the effect on validity should be minimal.

Conclusion

We tested two electronic medication reconciliation tools designed with different conceptual understandings of cognitively complex tasks. One system, currently used daily by thousands of clinicians, produced triple the rate of errors observed on a system more deliberately designed with sound usability and cognitive engineering principles. There is growing evidence that there are significant differences in the way clinicians interact with an electronic reconciliation tool and that the amount of time required and the accuracy of documentation is dependent on the quality of the design and its usability characteristics.37,38 Examining the intersection of health information technology and patient safety with practical conceptual models can advance the EHR-enabled healthcare system towards the goal of improving patient safety.39

Acknowledgments

We want to express our gratitude to all clinicians who volunteered their time and contributed their skills and insights to the study. Many thanks are also due to Dr. Elisabeth Drucker for her essential support and help.

References

- 1.Classen DC, Pestotnik SL, Evans RS, Lloyd JF, Burke JP. Adverse drug events in hospitalized patients: Excess length of stay, extra costs, and attributable mortality. JAMA. 1997;277(4):301–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bates DW, Spell N, Cullen DJ, et al. The costs of adverse drug events in hospitalized patients. Adverse Drug Events Prevention Study Group. J Am Med Assoc. 1997 Jan 22-29;277(4):307–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tam VC, Knowles SR, Cornish PL, Fine N, Marchesano R, Etchells EE. Frequency, type and clinical importance of medication history errors at admission to hospital: a systematic review. CMAJ. 2005 Aug 30;173(5):510–515. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.045311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) Health information technology: standards, implementation specifications, and certification criteria for electronic health record technology, 2014 edition; revisions to the permanent certification program for health information technology. Final rule. In: Department of Health and Human Services. Federal Register. 2012 Sep 06;77(ed2012):54163–54292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Joint Commission. The Joint Commission National Patient Safety Goals. 2005. http://www.foip.com/Focus_2005_1.pdf.

- 6.The Joint Commission. Using medication reconciliation to prevent errors. Sentinel Event Alert. 2006. http://www.iointcommission.org/assets/1/18/SEA_35.PDF. [PubMed]

- 7.Mueller SK, Sponsler KC, Kripalani S, Schnipper JL. Hospital-based medication reconciliation practices: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2012 Jul 23;172(14):1057–1069. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vermeire E, Hearnshaw H, Van Royen P, Denekens J. Patient adherence to treatment: three decades of research. A comprehensive review. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2001 Oct;26(5):331–342. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2001.00363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kantor ED, Rehm CD, Haas JS, Chan AT, Giovannucci EL. Trends in Prescription Drug Use Among Adults in the United States From 1999-2012. JAMA. 2015 Nov 3;314(17):1818–1830. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.13766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lesselroth BJ, Holahan PJ, Adams K, et al. Primary care provider perceptions and use of a novel medication reconciliation technology. Inform Prim Care. 2011;19(2):105–118. doi: 10.14236/jhi.v19i2.802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Milone AS, Philbrick AM, Harris IM, Fallert CJ. Medication reconciliation by clinical pharmacists in an outpatient family medicine clinic. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2014 Mar-Apr;54(2):181–187. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2014.12230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grossman JM, Gourevitch R, Cross D. Washington, DC: The National Institute for Health Care Reform (NIHCR); 2014. Jul, Hospital Experiences Using Electronic Health Records to Support Medication Reconciliation. Research Brief No. 17. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lesselroth BJ, Adams K, Tallett S, et al. Design of admission medication reconciliation technology: A human factors approach to requirements and prototyping. HERD. 2013 Spring;6(3):30–48. doi: 10.1177/193758671300600304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sweller J. Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive Science. 1988 Apr-Jun;12(2):257–285. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sweller J, Ayres PL, Kalyuga S. New York. Springer; 2011. Cognitive load theory. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haist F, Shimamura AP, Squire LR. On the relationship between recall and recognition memory. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 1992 Jul;18(4):691–702. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.18.4.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gillund G, Shiffrin RM. A retrieval model for both recognition and recall. Psychol Rev. 1984 Jan;91(1):1–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nielsen J. Iterative user interface design. IEEE Computer. 1993;26(11):32–41. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morrow D, Leirer V, Sheikh J. Adherence and medication instructions. Review and recommendations. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1988 Dec;36(12):1147–1160. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1988.tb04405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gray SL, Mahoney JE, Blough DK. Medication adherence in elderly patients receiving home health services following hospital discharge. Ann Pharmacother. 2001 May;35(5):539–545. doi: 10.1345/aph.10295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vogeli C, Shields AE, Lee TA, et al. Multiple chronic conditions: prevalence, health consequences, and implications for quality, care management, and costs. J Gen Intern Med. 2007 Dec;3(22):391–395. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0322-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gu Q, Dillon CF, Burt VL. Prescription Drug Use Continues to Increase: U.S. Prescription Drug Data for 2007-2008. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Villanyi D, Fok M, Wong RYM. Medication Reconciliation: Identifying Medication Discrepancies in Acutely Ill Hospitalized Older Adults. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 10//2011;9(5):339–344. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mueller SK, Sponsler KC, Kripalani S, Schnipper JL. Hospital-based medication reconciliation practices: A systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2012 Jul 23;172(14):1057–1069. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schnipper JL, Wetterneck TB. Paper presented at: Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting. Toronto, ON: 2015. What are the best ways to improve medication reconciliation? An on-treatment analysis of the MARQUIS study. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wetterneck TB, Kaboli PJ, Stein JM, Schnipper JL. Paper presented at: Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Meeting. National Harbor, MD: 2015. Medication reconciliation and health information technology: HIT and systems challenges in the MARQUIS study. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tullis T, Albert B. Measuring the user experience: Collecting, analyzing, and presenting usability metrics. Amsterdam ; Boston: Elsevier/Morgan Kaufmann; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schumacher RM, Lowry SZ. NIST Guide to the Processes Approach for Improving the Usability of Electronic Health Records. Washington, D.C: National Institute of Standards and Technology; 2010. NISTIR 7741. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morae [computer program]. Version 3.1. Okemos, MI: TechSmith Corporation; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carayon P, Wetterneck TB, Rivera-Rodriguez AJ, et al. Human factors systems approach to healthcare quality and patient safety. Appl Ergon. 2013 Jul 8; doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2013.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borycki E. Trends in health information technology safety: from technology-induced errors to current approaches for ensuring technology safety. Healthc Inform Res. 2013 Jun;19(2):69–78. doi: 10.4258/hir.2013.19.2.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sittig DF, Singh H. Defining health information technology-related errors: New developments since to err is human. Arch Intern Med. 2011 Jul 25;171(14):1281–1284. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saleem JJ, Russ AL, Justice CF, et al. Exploring the persistence of paper with the electronic health record. Int J Med Inf. 2009;78(9):618–628. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Horsky J, Kaufman DR, Oppenheim MI, Patel VL. A framework for analyzing the cognitive complexity of computer-assisted clinical ordering. JBiomedInform. 2003 Feb-Apr;36(1-2):4–22. doi: 10.1016/s1532-0464(03)00062-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Horsky J, Phansalkar S, Desai A, Bell D, Middleton B. Design of decision support interventions for medication prescribing. Int J Med Inf. 2013;82(6):492–503. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Horsky J, Schiff GD, Johnston D, Mercincavage L, Bell D, Middleton B. Interface design principles for usable decision support: A targeted review of best practices for clinical prescribing interventions. J Biomed Inform. 2012 Dec;45(6):1202–1216. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kushniruk AW, Santos SL, Pourakis G, Nebeker JR, Boockvar KS. Cognitive analysis of a medication reconciliation tool: applying laboratory and naturalistic approaches to system evaluation. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2011;164:203–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Plaisant C, Wu J, Hettinger AZ, Powsner S, Shneiderman B. Novel user interface design for medication reconciliation: An evaluation of Twinlist. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015 Mar;22(2):340–349. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocu021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meeks DW, Takian A, Sittig DF, Singh H, Barber N. Exploring the sociotechnical intersection of patient safety and electronic health record implementation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014 Feb 1;21(e1):e28–e34. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2013-001762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]