Abstract

Purpose

To determine whether activated CD11b+ CD15+ granulocytes increase in the blood of patients with uveal melanoma.

Methods

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated by density gradient centrifugation from the blood of patients with primary choroidal/ciliochoroidal uveal melanomas (six women, four men; age range, 46–91 years) and healthy control donors (14 women, 10 men; age range, 50 – 81 years). The expression of CD15 and CD68 on CD11b+ myeloid cells within PBMCs and primary uveal melanomas was evaluated by flow cytometry. CD3ζ chain expression by CD3ε+ T cells in PBMCs and within primary uveal melanomas was measured as an indirect indication of T-cell function.

Results

The percentage of CD11b+ cells in PBMCs of patients with uveal melanoma increased 1.8-fold in comparison to healthy donors and comprised three subsets: CD68 negative CD15+ granulocytes, which increased 4.1-fold; CD68− CD15− cells, which increased threefold; and CD68+ CD15low cells, which were unchanged. A significant (2.7-fold) reduction in CD3ζ chain expression on CD3ε+ T cells, a marker of T-cell dysfunction, was observed in PBMCs of patients with uveal melanoma in comparison with healthy control subjects and correlated significantly with the percentage of CD11b+ cells in PBMCs. CD3ζ chain expression on T cells within primary tumors was equivalent to CD3ζ expression in PBMCs of the same patient in four of five patients analyzed.

Conclusions

Activated CD11b+ CD15+ granulocytes expand in the blood of patients with uveal melanoma and may contribute to immune evasion by ocular tumors by inhibiting T-cell function via decreasing CD3ζ chain expression.

Uveal melanomas are enigmatic. First, despite advances in treating the primary tumor by radiation therapy, thermotherapy, or resection, the 20% 5-year mortality rate has not changed.1 Second, it is well documented that uveal melanomas express immunogenic proteins (antigens)2 that induce tumor-specific CD8+ cytolytic T-lymphocyte (CTL) responses,3,4 which should target tumors by recognizing antigens presented as processed peptides via HLA Class I molecules on the cell surface. Paradoxically, however, both high HLA expression by primary uveal melanomas5 and lymphocyte infiltration of primary uveal melanomas, predominantly composed of CD3+ CD8+ T cells,6,7 are poor prognostic indicators.8 The poor prognosis associated with these measures has been explained by an abrogation of tumoricidal NK cell responses due to inhibitory class I expression.9,10 However, as CD8+ T cells infiltrate progressively growing primary tumors expressing HLA class I, these data also clearly indicate that the tumoricidal activity of CD8+ CTLs is somehow inhibited. The mechanism of CTL inhibition in uveal melanoma is not understood.

An unfavorable prognosis is also associated with uveal melanomas with an inflammatory infiltrate of CD11b+ CD68+ macrophages,11 which correlates with high HLA expression,5 and CD3+ T-cell infiltration,5 as well as other poor prognostic indicators including: large tumor size,11 epithelioid cell type,11 and monosomy of chromosome 3.12 The role of tumor-associated macrophages in uveal melanoma is also not understood. However, an increased density of CD68+ macrophages in uveal melanomas did correlate with increased vascular density in one study,11 suggesting a role in angiogenesis.

An immunosuppressive role of tumor-associated CD11b+ cells has been suggested in transplantable tumor models in mice. For example, tumors developing in the anterior chamber of the eye are heavily infiltrated with CD11b+ myeloid cells that inhibit CTL activity in vitro.13 Similarly, tumors transplanted in the skin are infiltrated by immunosuppressive CD11b+ F4/80+ macrophages that inhibit T-cell proliferation and induce apoptosis via nitric oxide (NO) production alone14 or in combination with arginase activity.15 These immunosuppressive intratumoral macrophages were derived from CD11b+ GR-1+ myeloid cells that expanded in the blood and spleen15 in response to tumor-derived factors16 and have been termed, myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs).17 MDSCs in mice are analogous to the immunosuppressive CD11b+ cells that accumulate in the blood of patients with malignancies. For example, activated CD11b+ CD15+ cells increased in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of patients with renal cell carcinoma18 and pancreatic cancer.19 These cells display granulocyte morphology and inhibit T-cell responses by interfering with T-cell receptor (TCR) signaling by reducing expression of the CD3ζ chain via increased arginase activity20 and/or H2O2 production.19 These data provide one explanation for the suppression of immune responses which is observed in patients with cancer.

Herein, we demonstrate that the percentage of activated CD11b+ CD15+ granulocytes is significantly greater in the blood of patients with uveal melanoma in comparison to healthy control subjects. Moreover, increased CD11b+ cell percentages in PBMCs of patients with uveal melanoma significantly correlated with reduced CD3ζ chain expression by T cells in PBMCs and within primary uveal melanomas. These data suggest that activated granulocytes contribute to immune evasion by uveal melanomas by inhibiting melanoma-specific T-cell responses.

Methods

Specimens

Biopsies of primary uveal melanomas (~1 mm3) from surgical enucleation and/or blood were obtained from patients with uveal melanoma who were treated at the Cole Eye Institute of the Cleveland Clinic. Blood from age- and sex-matched healthy control subjects was obtained at blood drives conducted by the Central Blood Bank of Pittsburgh. All specimens were obtained with informed consent under an Institutional Review Board-approved protocol in compliance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Sample Preparation and Flow Cytometric Staining

Peripheral blood (2–10 mL) was collected in tubes (Vacutainer; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) containing sodium heparin, and the PBMCs were purified by density gradient centrifugation with lymphocyte separation medium (LSM; MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH), according to the manufacturer’s instructions, within 3 hours after venipuncture. Cells at the interphase were collected, contaminating red blood cells were lysed by incubation in a hypotonic NH4Cl solution, and the PBMCs were then stored on ice in PBS or RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS).

Primary uveal melanoma biopsies, stored on ice in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, were removed to a 60-mm sterile Petri dish with 5 mL of RPMI-1640 supplemented with 1 mg/mL collagenase IV (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and 1% FBS (Sigma-Aldrich) or 5 mL HBSS supplemented with 1 mg/mL collagenase D (Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.25 mg/mL DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich). The specimen was then minced with scissors and incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 1.5 hours. Every 15 minutes, the sample was pipetted to hasten the generation of a single-cell suspension. At the end of the incubation, the cells were pelleted by centrifugation. The enzymatic reaction was stopped by resuspension in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS when collagenase D was used. The cells were washed with PBS and resuspended in flow cytometry buffer (PBS, 1% FBS) at a concentration ≤ 2.0 × 107 cells/mL.

PBMC or single-cell suspensions of primary uveal melanomas (≤106 cells in flow cytometry buffer) were transferred to individual wells of a 96-well plate and incubated on ice with combinations of the following fluorescently labeled antibodies: Pacific Blue anti-CD3ε (eBioscience, San Diego, CA), Alexa Fluor 488 anti-CD11b (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), APC anti-CD15 (BD Pharmingen) or their respective fluorescently conjugated isotype controls. PBMCs were washed and then fixed in PBS containing 0.25% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with a digitonin solution (100 μg/mL digitonin, 2.5% FBS, 0.01% NaN3), and then stained intracellularly with PE conjugated anti-CD3ζ antibody (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL) or an isotype control antibody. Alternatively, the cells were washed after primary antibody staining, fixed in solution (Cytofix/Cytoperm; BD Pharmingen), and then stained intracellularly with PE-conjugated anti-CD68 antibody (BD Pharmingen) or an isotype control antibody. Samples were run on a flow cytometer (FACSAria; BD Biosciences) and analyzed (FlowJo software; Tree Star; Ashland, OR).

Immunohistology

Sections (4 μm) of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded eyes with primary tumors were placed on slides and then baked at 65°C until dry. The slides were deparaffinized with xylene and then hydrated through graded alcohols. To quench endogenous peroxidase, the slides were placed in 3% hydrogen peroxide for 15 minutes at room temperature. To enhance immunoreactivity of the target antigen, the slides were microwaved in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 10 minutes at 80% power and then cooled 20 minutes at room temperature. They were incubated in a serum-free protein blocker (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) for 20 minutes at room temperature and then incubated with 0.2 mg/mL anti-CD15, (Biogenex, San Ramon, CA) or 0.4 ng/mL IgM isotype control (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) for 1 hour at room temperature. Secondary biotinylated goat anti-Mouse IgM (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) was applied to slides at a dilution of 1:200 for 30 minutes at room temperature. Avidin-biotin complex (Vector Laboratories) was added for 30 minutes at room temperature, followed by a red substrate (Vector Nova Red; Vector Laboratories). The slides were incubated 5 to 10 minutes until the desired color developed, and then they were counterstained in hematoxylin (Shandon; Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) for 2 minutes, coverslipped, and viewed by bright-field microscopy.

Five high-power fields (400×) were scored for CD15+ cells by acquiring 12-bit images with a digital camera mounted on a microscope (BX60; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with background correction and saved into 16-bit space. Segmentation in RGB space with these color distributions is very difficult, but inverting the image allowed the color difference between the red substrate and melanin pigment to be clearly distinguished in the green channel by automated thresholding. Inverted images were adjusted (Adjust/Hue/Green channel saturation = 100%; Photoshop; Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA), and adjustments were automated with programmed actions to maintain consistency. Inverted images were then further analyzed (MetaMorph ver. 7.5.6; Universal Imaging, Downingtown, PA), color separated, and thresholded on the green channel, to define and score the CD15+ cells.

Statistical Analysis

CD11b+ cells, CD11b+ cell subsets, and CD3ζ chain expression were compared between patients with uveal melanoma and healthy control subjects by unpaired two-tailed Student t-tests or unpaired two-tailed Mann-Whitney U tests depending on the normality of the data (Prism, ver. 4; GraphPad, San Diego, CA). The R language and environment for statistical computing version 2.8.0 (www.R-project.org) was used for statistical modeling and graphics. CD3ζ chain expression was modeled as a nonlinear function of the percentage of CD11b+ cells. CD3ζ counts and independent variables (percentages of CD11b+ cells and CD11b+ cell subsets) were log transformed. A generalized additive model was used to fit a cubic spline with 3 degrees of freedom. Davies’ test was used to check for a change in slope. A broken-stick segmented regression model21 was used as an alternative way to account for the different slopes that were observed in the control and uveal melanoma groups. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

CD11b+ Myeloid Cell Subsets in PBMCs of Patients with Uveal Melanoma

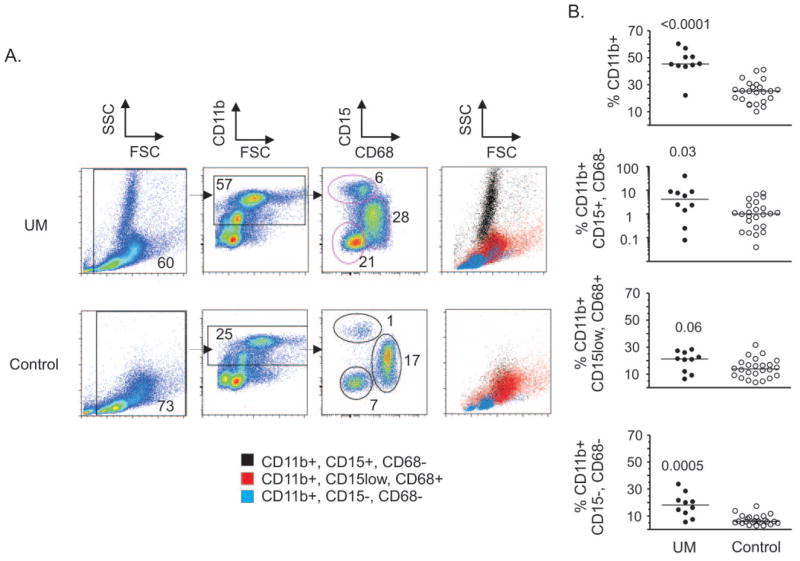

Blood was collected from patients with uveal melanoma (6 women, 4 men, aged 46–91 years) immediately before treatment involving surgical enucleation or radioactive plaque therapy (Table 1) and from healthy control donors (14 women, 10 men) of similar age (50 – 81 years) and sex (60% women, 40% men) (Table 2). PBMCs were isolated by density gradient centrifugation, and flow cytometric analysis was performed to determine whether activated CD11b+ CD15+ granulocytes expanded in the blood of patients with uveal melanoma (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Uveal Melanoma Cohort

| Patient | Sex | Age | Tumor Size (L, W, H mm) | Tumor Location | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 50 | 16, 14, 10.6 | Ciliochoroid | Enucleation |

| 2 | M | 65 | 16, 12, 3.6 | Choroid | Plaque |

| 3 | F | 86 | 18, 16, 11 | Choroid | Enucleation |

| 4 | F | 76 | 18, 18, 10 | Choroid | Enucleation |

| 5 | F | 78 | 20, 18, 3.5 | Choroid | Enucleation |

| 6 | F | 88 | 11, 10, 3 | Choroid | Plaque |

| 7 | M | 46 | 13, 12, 2 | Choroid | Enucleation |

| 8 | F | 64 | 9, 7, 1.5 | Choroid | Plaque |

| 9 | M | 91 | 20, 20, 7.6 | Ciliochoroid | Enucleation |

| 10 | F | 67 | 15, 12, 7.6 | Choroid | Enucleation |

| 11 | M | 75 | 12, 15, 8.5 | Ciliochoroid | Enucleation |

A blood sample was not taken from patient 11. A primary uveal melanoma biopsy was not taken from patient 7. L, length; W, width; H, height.

Table 2.

Healthy Control Cohort

| Donor | Sex | Age | Donor | Sex | Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 60 | 13 | F | 52 |

| 2 | F | 56 | 14 | F | 53 |

| 3 | M | 67 | 15 | F | 54 |

| 4 | M | 55 | 16 | F | 59 |

| 5 | M | 56 | 17 | F | 54 |

| 6 | F | 57 | 18 | M | 63 |

| 7 | M | 58 | 19 | M | 50 |

| 8 | M | 57 | 20 | F | 50 |

| 9 | F | 55 | 21 | M | 51 |

| 10 | F | 58 | 22 | F | 52 |

| 11 | F | 50 | 23 | F | 53 |

| 12 | M | 56 | 24 | M | 81 |

Figure 1.

Myeloid cell subset characterization within PBMCs. (A) The expression of CD15 and CD68 by CD11b+ cells within PBMCs isolated by density gradient centrifugation of blood from patients with uveal melanoma (UM) and healthy control donors (Control) was evaluated by flow cytometric analysis. Events were gated from debris and electronic noise in the first panel; the numbers indicate the percentage of total cells contained within the marked gate. The second panel displays gating of CD11b+ cells that were evaluated for expression of CD15 and CD68, which are displayed in the third panel. The numbers indicate the percentage of cells of total live cells gated in the first panel. The forward- and side-scatter properties of CD11b+ cell subsets displayed in the third panel are shown in the fourth panel. (B) The percentage of CD11b+ cells and CD11b+ cell subsets of total live cells in patients with uveal melanoma and healthy control donors are shown and were compared by two-tailed Mann-Whitney U tests. P-values are shown. Symbols: data from individual blood samples; bars: the median.

CD11b+ CD15+ granulocytes are normally excluded from PBMC isolates of healthy donor blood after density gradient centrifugation because granulocytes pellet with red blood cells. However, granulocyte activation induces changes in buoyancy resulting in granulocytes localizing with PBMCs at the interphase of density gradients.19 Storage of blood at room temperature can also induce granulocyte activation,22 which occurs within 6 to 8 hours.23 Therefore, PBMCs were isolated within 3 hours after venipuncture to avoid artifactual increases in the percentage of granulocytes due to storage conditions.

The percentage of CD11b+ myeloid cells significantly increased (1.8-fold) in patients with uveal melanoma. The overall increase in myeloid cells was due to significant increases in CD11b+ cell subsets composed of CD15+ cells that did not express CD68 (4.1-fold) and cells that were negative for both CD15 and CD68 (3-fold). CD11b+ cells that expressed CD68 and low levels of CD15 did not increase significantly. CD15+ CD68− cells exhibited high side-scatter properties characteristic of granulocytes, CD11b+ cells that were negative for both CD15 and CD68 expression exhibited a lymphocyte profile, and CD11b+ cells that expressed CD68 and low levels of CD15 exhibited a monocyte profile in forward and side-scatter analysis (Fig. 1A). The expansion of CD11b+ cells did not correlate significantly with tumor size (largest basal diameter) or tumor height. These data indicate that activated CD15+ granulocytes increase in the blood of patients with uveal melanoma.

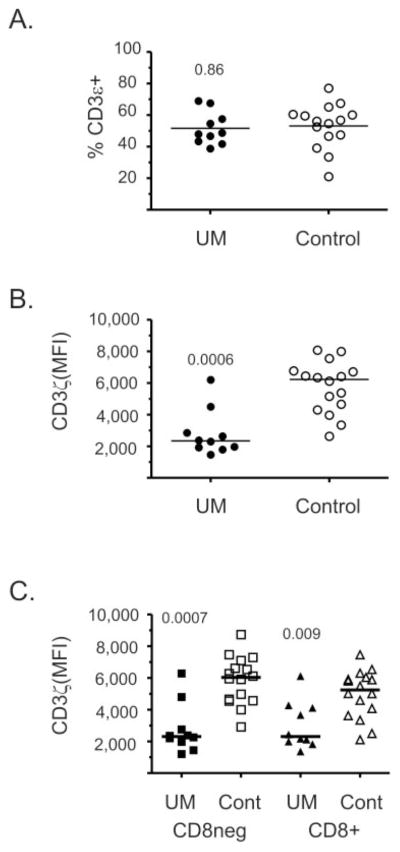

CD3ζ Chain Expression on T Cells in PBMCs of Patients with Uveal Melanoma

Activated CD11b+ CD15+ granulocytes have been shown to inhibit T-cell function by interfering with TCR signal transduction by inhibiting translation of the CD3ζ chain.19,18 Therefore, we measured CD3ζ chain expression by flow cytometric analysis of CD3ε+ T cells from patients with uveal melanoma and from healthy control subjects (Fig. 2). The percentage of CD3ε+ T cells within PBMCs was equivalent in patients with uveal melanoma and healthy control donors (Fig. 2A). However, CD3ζ chain expression was significantly reduced (2.7-fold) in CD3ε+ T cells of patients with uveal melanoma (Fig. 2B). CD3ε+ T-cells, which did not express the CD8 molecule, and CD8+ CD3ε+ T cells both demonstrated significant reductions in CD3ζ chain expression (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

CD3ζ expression on T cells was reduced in patients with uveal melanoma. (A) CD3ε expression was determined by flow cytometric analysis of PBMCs of patients with uveal melanoma (UM) and healthy control subjects (Control). The percentage of total live cells is shown, and groups were compared by a two-tailed Student’s t-test, with the P-values shown. Symbols: results from individual patients; bar, the mean. CD3ζ chain expression on gated CD3ε+T cells, (B) and CD3ε+T cells that expressed or did not express CD8, (C) was evaluated. Data are presented as the MFI which was corrected by subtracting the MFI of an isotype control. Symbols: values from individual blood samples; bar, the median.

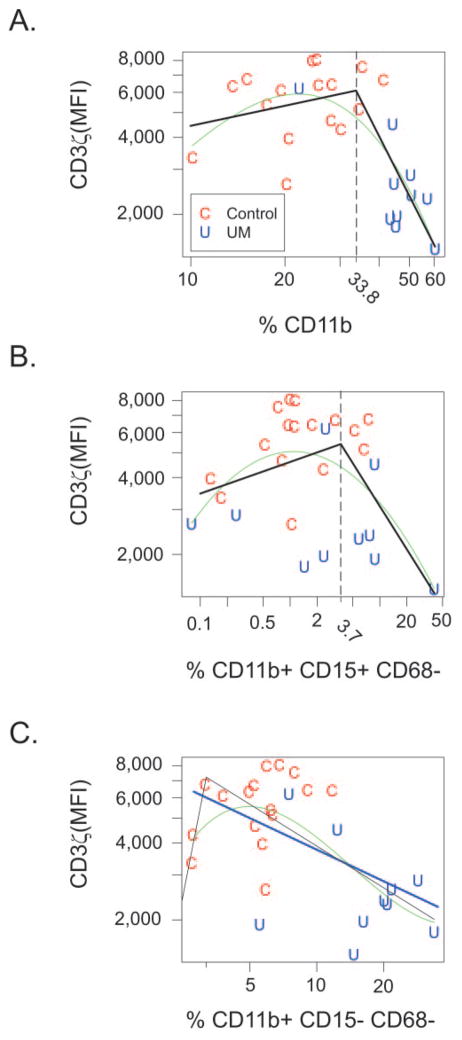

Two statistical models were used to evaluate the relationship between CD3ζ chain expression and the percentage of CD11b+ cells (Fig. 3A) and CD11b+ cell subsets that expressed CD15 but not CD68 (Fig. 3B), or did not express CD15 or CD68 (Fig. 3C). A generalized additive model was used to fit a cubic spline (green line) that demonstrated a statistically significant relationship (P = 0.00025) in which CD3ζ chain expression was relatively constant for total CD11b+ cell percentages less than 30% but decreased when CD11b+ cell percentages were greater than 30% (Fig. 3A). Davies’ test indicated a change in slope at 33.9% (P = 0.0004), and so a broken-stick model (Fig. 3A, black lines) was also fitted, which indicated that the slope was essentially 0 when CD11b+ cell percentages were less than 33.8% (slope, 0.26; 95% confidence interval [CI]: −0.36 to 0.88, P = 0.4190), whereas the slope was negative when percentages were greater than 33.8% (slope, −2.41; 95% CI: −3.67 to −1.16). In addition, there was a statistically significant difference of −2.67 between the two slopes (P = 0.0006, 95% CI: −4.10 to −1.24).

Figure 3.

Increased percentages of activated CD11b+ cells correlated with reduced CD3ζ chain expression. CD3ζ chain expression was modeled as a function of the percentage of CD11b+ cells (A), CD11b+ CD15+ CD68− cells (B), and CD11b+ CD15− CD68− cells (C) within control subjects (C) and patients with uveal melanoma (U). A generalized additive model was used to generate a cubic spline (green). A broken-stick model was used to generate lines shown in black. Linear regression (blue line) was also used in (C).

The relationship between CD3ζ chain expression and the percentage of the CD11b+ subset which expressed CD15+ but not CD68, approached statistical significance (P = 0.0645) when modeled as a spline function (Fig. 3B, green line), and a significant difference (P = 0.0184) in slopes of −0.68 was detected at 3.7% (Fig. 3B). The relationship between CD3ζ chain expression and CD11b+, CD15−, CD68− cells was significant (P = 0.006) when modeled as a spline function (Fig. 3C, green line) as well as simple linear regression (Fig. 3C, blue line, slope, −0.41; P = 0.0035). Correspondingly, the relationship was not adequately fit by a broken-stick model (Fig. 3C, black lines).

These data indicate that reduced CD3ζ chain expression, a marker of T-cell dysfunction, is associated with: percentages of total CD11b+ myeloid cells above 33.8%, which occurred in 9 (90%) of 10 patients with uveal melanoma but in only 4 (17%) of 24 healthy control donors and percentages of CD11b+ CD15+ CD68− cells above 3.7% which occurred in 5 (50%) of 10 patients with uveal melanoma but only 4 (17%) of 24 healthy control donors. Reduced CD3ζ chain expression also correlated with increased percentages of CD11b+ cells that did not express CD15 or CD68.

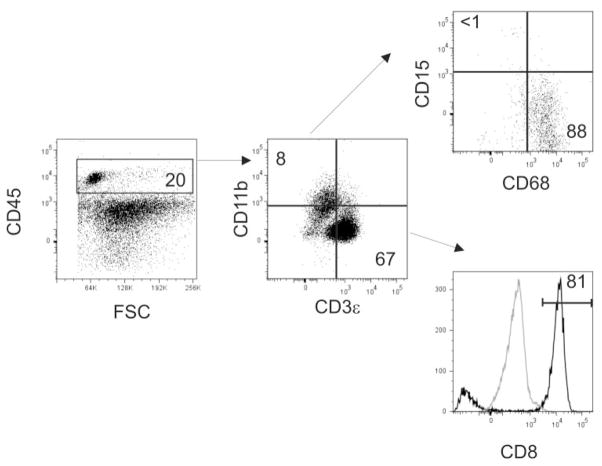

Characterization of Infiltrating Leukocytes of Primary Uveal Melanomas

Flow cytometric analysis was also performed on collagenase-digested biopsies of seven primary uveal melanomas to determine the composition of tumor-infiltrating leukocytes, which were identified by expression of CD45 (Fig. 4). A sufficient number of CD45+ events were collected from all biopsies allowing for analysis of the expression of CD11b, CD15, CD68, CD3ε, and CD8 (Table 3). Analysis of CD3ε+ T cells within the primary uveal melanoma of patient 11 was not performed. Both CD11b+ and CD3ε+ leukocytes infiltrated primary uveal melanomas in four of six tumors. The percentage of CD3ε+ cells, which were primarily CD8+ T cells, was greater than the percentage of CD11b+ cells in five of six tumors. These data reproduce previously reported observations indicating that CD8+ T cells are the primary leukocyte infiltrate of uveal melanoma.6,7

Figure 4.

Characterization of infiltrating leukocytes of primary uveal melanoma. Biopsies of primary uveal melanomas were collagenase digested to generate single-cell suspensions that were stained with anti-CD45, anti-CD11b, anti-CD68, anti-CD15, anti CD3ε, and anti-CD8 antibodies. Leukocytes were identified by expression of CD45 (left) and the number indicates the percentage of cells contained within a gate that excluded debris and dead cells. Gated CD45+ cells were evaluated for the expression of CD11b, and CD3ε (middle). Numbers indicate the percentage of CD45+ cells. Expression of CD15 and CD68 by gated CD11b+ cells is shown in the top right. Numbers indicate the percentage of CD11b+ cells that express CD15 or CD68. The expression of CD8 by CD3ε+ T cells is shown by the black histogram in the bottom right. Gray histogram: isotype control staining; horizontal bar: the percentage of CD8+ CD3ε+ cells. Data from patient 9 are shown.

Table 3.

Leukocyte Infiltration of Primary Uveal Melanoma

| Patient | % CD11b of CD45+ | % CD68 of CD11b+ | % CD15 of CD11b+ | % CD3 of CD45+ | % CD8+ of CD3+ | % CD8− of CD3+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ND | ND | ND | 72 | 74 | 26 |

| 3 | 8 | 88 | ND | 67 | 81 | 19 |

| 4 | 15 | 52 | ND | 22 | 45 | 55 |

| 5 | 19 | 72 | 4 | 24 | 51 | 49 |

| 9 | ND | ND | ND | 85 | 94 | 6 |

| 10* | 62 | 64 | 9 | 12 | 45 | 55 |

| 11* | 32 | 82 | 4 | NA | NA | NA |

Samples 10 and 11 were digested in collagenase D. All other samples were digested in collagenase IV.

ND, not detectable, below isotype control staining; NA, not analyzed.

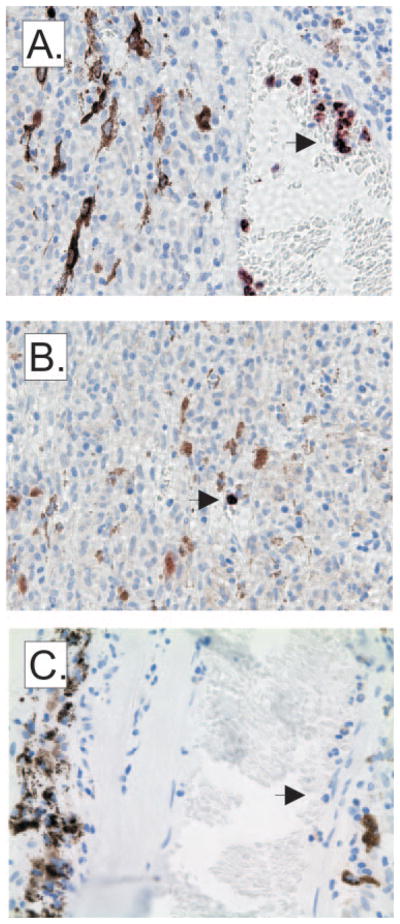

CD11b+ cells within the tumor microenvironment primarily expressed CD68, a marker of macrophages, but not CD15, which is markedly different from the myeloid cell populations that expanded in the blood of these same patients and expressed CD15 but not CD68 (Fig. 1). To determine whether collagenase digestion of primary tumors adversely affects the recovery of CD15+ granulocytes, we performed immunohistology (Fig. 5). Very few CD15+ polymorphonuclear leukocytes were observed, and those that were present were located primarily within blood vessels (Fig. 5A) and, rarely, within primary tumors (Fig. 5B). Isotype control staining was uniformly negative (Fig. 5C). These data confirm the flow cytometric analysis of collagenase-digested eyes, indicating that CD45+ CD15+ cells did not accumulate in primary uveal melanomas.

Figure 5.

CD15 expression within primary uveal melanomas. CD15 expression which is representative of the seven primary uveal melanomas obtained from enucleation shows that CD15+ cells are primarily located within vessels of the tumor (A) and rarely within the tumor. (B) Staining of sections with an isotype control was uniformly negative. (C) Arrows: polymorphonuclear cells.

Two enzyme solutions containing different collagenases (collagenase IV or D) were used to render uveal melanomas into single-cell suspensions. The percentage of CD11b+ cells was lower than CD3ε+ T cells in all uveal melanomas that were digested in collagenase IV. However, the percentage of CD11b+ cells of CD45+ cells was highest in uveal melanomas that were digested with collagenase D (patients 10 and 11) which could indicate that the different collagenase treatments affected the isolation of CD11b+ myeloid cells, or CD8+ T cells, respectively.

CD3ζ Chain Expression on T Cells Infiltrating Primary Uveal Melanomas

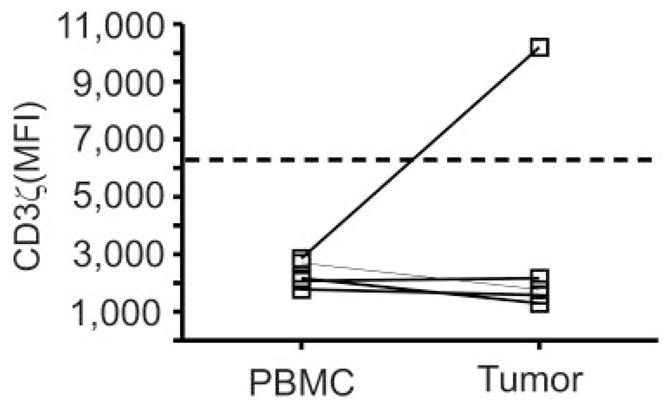

CD3ζ chain expression was also measured on CD3ε+ T cells infiltrating uveal melanomas and was compared with CD3ζ chain expression in CD3ε+ T cells of the PBMCs of the same patient (Fig. 6). In four of five primary uveal melanoma specimens (patients 3, 4, 9, and 10), CD3ζ chain expression by infiltrating T cells was equivalent in comparison to CD3ζ chain expression in PBMCs of the same patient and markedly reduced in comparison to CD3ζ chain expression in PBMCs of healthy control subjects (Fig. 6, dashed line). Staining for CD3ζ was not performed on the primary uveal melanoma from patient 1. Of note, CD3ζ chain expression in patient 5 was increased in tumor-infiltrating CD3ε+ T cells to a level higher than CD3ζ chain expression in healthy control donors. However, only 55 CD3ε+ events were collected in determining the CD3ζ mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for this specimen, whereas many more CD3ε+ events (range, 441–9437) were collected from the other specimens that did not show increased CD3ζ chain expression. Hence, the low number of events used for analysis may have affected these results. Regardless, reduced CD3ζ chain expression was common to most of the patients with uveal melanoma and may indicate that T cells are functionally compromised both systemically and within the ocular tumor microenvironment.

Figure 6.

CD3ζ chain expression on T cells within PBMCs and primary uveal melanoma. CD3ζ chain expression was measured on CD3ε+ T cells within PBMCs and within primary uveal melanomas of the same patient. Symbols: CD3ζ MFI values from individual patients; dashed line: the median expression of CD3ζ on CD3ε+ T cells from PBMCs of healthy control donors.

Discussion

In this study, we were the first to demonstrate that CD11b+ CD15+ granulocytes expand in the blood of patients with uveal melanoma. In other malignancies—for example, renal cell carcinoma18 and pancreatic cancer19—the expansion of CD11b+ CD15+ granulocytes has been associated with inhibited T-cell function. We were unable to directly assess T-cell function in the PBMCs of patients with uveal melanoma, because the total cell yield after PBMC isolation did not permit both flow cytometric and functional analyses. However, we observed that CD3ζ chain expression by all T cells within PBMCs was reduced in patients with uveal melanoma in comparison to healthy control subjects (Fig. 2), and reduced CD3ζ chain expression has been shown to inhibit T-cell function.24 Moreover, we have recently demonstrated that inhibited T-cell function due to prolonged storage of blood at room temperature is associated with reduced CD3ζ chain expression, which correlates significantly with increased frequencies of CD11b+ CD15+ cells in PBMCs.23 Therefore, our data strongly suggest that T-cell function in patients with uveal melanoma is compromised.

The reduction in CD3ζ chain expression in patients with uveal melanoma significantly correlated with increased percentages of CD11b+ cells (Fig. 3), suggesting a causal relationship. The mechanism by which myeloid cells, directly or indirectly through another cell population, reduce CD3ζ chain expression in patients with uveal melanoma is the focus of future experimentation. Two mechanisms of CD3ζ chain downmodulation by CD11b+ MDSCs have been described. In patients with renal cell carcinoma,18 arginase activity of CD11b+ CD15+ cells significantly correlated with reduced CD3ζ chain expression, and depletion of CD11b+ cells within the PBMCs of these patients restored CD3ζ chain expression and T-cell function to levels observed in healthy control subjects. It is important to note that L-arginine levels were reduced in plasma of the patients,18 indicating that the influence of MDSCs on L-arginine metabolism is not limited to the tumor microenvironment but rather is a systemic affect. This finding explains why CD3ζ chain downmodulation was observed in all T cells within PBMCs. In confirmation of the influence of L-arginine metabolism on T-cell function, Zea et al.20 demonstrated that CD3ζ chain expression was reduced and T-cell function was impaired when T cells were stimulated in medium without L-arginine. The inhibition of T-cell proliferation was associated with the failure to re-express the CD3ζ chain after activation and was due to an inhibition of translation not transcription. Recently, Rodriguez et al.25 showed that inhibited CD3ζ chain translation was the result of the activation of the GCN2 kinase which inactivates the elongation factor eIF2α.

Activation of GCN2 kinase may also be responsible for reduced CD3ζ chain expression in T cells in pancreatic cancer, because CD3ζ chain downmodulation is associated with increased isoprostane levels, a product of lipid peroxidation,19 and GCN2 kinase can be activated by reactive oxygen.26 The addition of H2O2 or granulocytes to PBMC cultures of healthy donors inhibited T-cell function in this study.19 Moreover, T-cell function was restored in granulocyte/PBMC co-cultures by the addition of catalase, which converts H2O2 to H2O, providing direct evidence that granulocyte-expressed reactive oxygen species (ROS) is the mediator of T-cell inhibition. The increase of isoprostanes in plasma of these patients provides further support for the systemic influence of activated granulocytes on T cells.

The CD3 complex comprises five distinct molecules that associate with the T-cell receptor (TCR). Intact CD3 complex expression is necessary for stable cell surface expression of the CD3 molecule. However, reduced CD3ζ chain expression was not associated with reduced cell surface CD3ε expression in our study (Fig. 2). Equivalent CD3 complex expression in the absence of CD3ζ-chain expression is a common observation in patients with cancer,24 and this phenomenon has been explained, not by the loss of an epitope, as polyclonal antibodies similarly failed to detect CD3ζ,27 but by replacement of the ζ-chain by other molecules—for example, the Fcε γ chain, which can stabilize the CD3 molecule on the cell surface.28 However, TCR signal transduction via these replacement molecules is not equivalent to signaling via ζ chain and leads to the suppression of T-cell proliferation and cytokine production.24 Ksander et al.4 demonstrated that tumor-specific CD8+ T cells infiltrating primary uveal melanomas proliferate very poorly in vitro. Our data suggest that hypoproliferation of T cells infiltrating uveal melanomas may have resulted from reduced CD3ζ chain expression.

We have recently demonstrated that the failure to control tumors developing in the anterior chamber of the eye of mice is associated with an accumulation of CD11b+ GR-1+ cells within the ocular tumor microenvironment that suppressed CD8+ CTL responses in vitro.13 These data suggest that intratumoral MDSCs may contribute to inhibiting CTL responses within the eye. Suppression of melanoma-specific CD8+ T-cell responses by ocular tumor–associated macrophages would provide another explanation of the poor prognosis of patients with uveal melanoma with primary uveal melanomas heavily infiltrated with CD68+ macrophages.11 However, an obvious paradox is that ROS production by macrophages is tumoricidal. Therefore, how can ROS production be immunosuppressive toward T cells without exerting tumoricidal effects? Two explanations have been described: First, certain tumors resist ROS-mediated apoptosis by increasing the expression of anti-oxidant molecules, for example catalase and glutathione.29 Second, MDSC coexpression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (NOS2) and arginase I which both metabolize L-arginine leads to L-arginine depletion, which limits NO production, thereby inhibiting NO mediated apoptosis of tumor cells.30 Moreover, in low-L-arginine conditions, superoxide is generated by the reductase domain of NOS231 which further inhibits T-cell function via decreasing CD3ζ chain expression.

Tryptophan metabolism by immune suppressive dendritic cells expressing indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) has also been shown to reduce CD3ζ chain expression in CD8+ but not CD4+ T cells via GCN2 kinase activation and kyurenine production, a tryptophan catabolite.32 Of interest, CD3ζ chain sufficient CD4+ T cells proliferated after in vitro stimulation under low tryptophan conditions and were converted into FoxP3+ T regulatory (Treg) cells. CD11b+, GR-1+, CD115+ MDSCs have also been shown to induce the development of CD4+ FoxP3+ Tregs.33 However, these MDSCs promote CD4+ Treg generation while inhibiting CD4+ T-cell proliferation. Therefore, MDSC may suppress tumoricidal T-cell activity by both direct (CD3ζ chain downmodulation) and indirect (Treg induction) mechanisms. In our study, CD3ζ chain expression was reduced in both CD8+ and CD8 negative CD3ε+ cells of patients with uveal melanoma (Fig. 2C). We cannot exclude the possibility that some of these CD8− cells, presumably CD4+ T cells, are MDSC-induced Tregs that are hypoproliferative due to decreased CD3ζ chain expression.

Staibano et al.34 described increased mortality in a cohort of patients with uveal melanoma with primary uveal melanomas containing CD3+ T cells that were negative for CD3ζ. These tumor-infiltrating T cells were Fas+ and were associated with tumors that were FasL+. As T cells undergoing Fas/FasL-induced apoptosis downregulate ζ-chain expression,35 the authors suggested a causal relationship between FasL expression by uveal melanoma and CD3ζ chain downmodulation. In our study, the percentage of CD3ε+ cells within PBMCs of patients with uveal melanoma was comparable to that in healthy control subjects, despite reduced CD3ζ chain expression (Fig. 2), which suggests that induction of apoptosis is not the mechanism of ζ-chain downmodulation in CD3ε+ T cells in the blood. We favor a nonapoptotic mechanism to explain reduced ζ-chain expression by T cells within the primary melanoma, because CD8+ T cells accumulate in such high frequencies within ocular tumors, which would be inconsistent with increased apoptosis. Hence, an alternative explanation is that ocular tumor–associated CD68+ macrophages and CD11b+ CD15+ granulocytes in peripheral blood reduce CD3ζ expression by increased arginase activity and/or increased reactive oxygen production, as has been reported by others.18,19

The identification of factors that promote increases in activated CD11b+ CD15+ cells in patients with cancer is an area of active research. We have demonstrated in a murine model of ocular tumor development that intratumoral accumulation of CD11b+ GR-1+ cells correlates with tumor burden, suggesting a causal relationship.13 In other murine tumor models, resection of the primary tumors decreases the frequency of CD11b+ GR-1+ cells in peripheral tissues.36 Hence, tumor-derived factors or factors induced by tumor growth must play a role in myeloid cell activation and MDSC accumulation. Along those lines, two independent laboratories have recently shown that S100 A8/A9 proteins regulate the accumulation of CD11b+ GR-1+ cells in mice.37,38 S100 A8/A9 proteins are upregulated during inflammation39 and in some circumstances may be expressed by tumors.38 Tumor cell–conditioned medium has been shown to upregulate the S100 A9 gene in hematopoietic progenitor cells, preventing their differentiation into CD11c+ dendritic cells and promoting their differentiation into CD11b+ GR-1+ MDSCs,37 which also express S100 A8/A9 proteins.38 S100 A8/A9 proteins are chemotactic for CD11b+ GR-1+ cells.38 Hence, tumor-induced expression of S100 A8/A9 increases CD11b+ GR-1+ cells systemically by preventing the normal differentiation of myeloid progenitors and promotes their migration into the tumor microenvironment. Additional S100 A8/A9 expression by CD11b+ GR-1+ cells further amplifies the accumulation of these cells in tumor-bearing animals.

In summary, our data demonstrate that expansion of activated CD11b+ myeloid cells in the blood correlates with reduced CD3ζ chain expression by T cells in the blood and within primary uveal melanomas. CD8+ T cells which infiltrate primary uveal melanomas may be inhibited in their tumoricidal activity because of reduced CD3ζ chain expression, providing an explanation for the poor prognosis associated with primary HLA-expressing uveal melanomas that are heavily infiltrated with CD8+ T cells.5

Acknowledgments

Supported by The Eye and Ear Foundation of Pittsburgh, National Eye Institute (NEI) Grant EY08098, an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness Inc., and a grant from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) (UL1 RR024153), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. The contents of the report are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NEI, NCRR, NIH, The Eye and Ear Foundation of Pittsburgh, or Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc.

The authors thank Melissa Indino (Central Blood Bank of Pittsburgh) for assistance in collecting blood samples from healthy donors; Nancy Zurowski (Department of Ophthalmology, University of Pittsburgh) for technical assistance in flow cytometry; Kim Fuhrer (Department of Pathology, University of Pittsburgh) for immunohistology preparation; Barbara Jacobs and Wayne Aldrich (Cleveland Clinic) for processing blood samples; and Walter Storkus (Department of Dermatology and Immunology, University of Pittsburgh) for helpful discussions and critical review of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosure: K.C. McKenna, None; K.M. Beatty, None; R.A. Bilonick, None; L. Schoenfield, None; K.L. Lathrop, None; A.D. Singh, None

References

- 1.Singh AD, Topham A. Survival rates with uveal melanoma in the United States: 1973–1997. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:962–965. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00077-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Dinten LC, Pul N, van Nieuwpoort AF, Out CJ, Jager MJ, van den Elsen PJ. Uveal and cutaneous melanoma: shared expression characteristics of melanoma-associated antigens. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:24–30. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kan-Mitchell J, Liggett PE, Harel W, et al. Lymphocytes cytotoxic to uveal and skin melanoma cells from peripheral blood of ocular melanoma patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1991;33:333–340. doi: 10.1007/BF01756599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ksander BR, Geer DC, Chen PW, Salgaller ML, Rubsamen P, Murray TG. Uveal melanomas contain antigenically specific and non-specific infiltrating lymphocytes. Curr Eye Res. 1998;17:165–173. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.17.2.165.5607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Waard-Siebinga I, Hilders CG, Hansen BE, van Delft JL, Jager MJ. HLA expression and tumor-infiltrating immune cells in uveal melanoma. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1996;234:34– 42. doi: 10.1007/BF00186516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Durie FH, Campbell AM, Lee WR, Damato BE. Analysis of lymphocytic infiltration in uveal melanoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1990;31:2106–2110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meecham WJ, Char DH, Kaleta-Michaels S. Infiltrating lymphocytes and antigen expression in uveal melanoma. Ophthalmic Res. 1992;24:20–26. doi: 10.1159/000267140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de la Cruz PO, Jr, Specht CS, McLean IW. Lymphocytic infiltration in uveal malignant melanoma. Cancer. 1990;65:112–115. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900101)65:1<112::aid-cncr2820650123>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma D, Luyten GP, Luider TM, Niederkorn JY. Relationship between natural killer cell susceptibility and metastasis of human uveal melanoma cells in a murine model. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36:435–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang H, Dithmar S, Grossniklaus HE. Interferon alpha 2b decreases hepatic micrometastasis in a murine model of ocular melanoma by activation of intrinsic hepatic natural killer cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:2056–2064. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Makitie T, Summanen P, Tarkkanen A, Kivela T. Tumor-infiltrating macrophages (CD68+ cells) and prognosis in malignant uveal melanoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:1414–1421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maat W, Ly LV, Jordanova ES, de Wolff-Rouendaal D, Schalij-Delfos NE, Jager MJ. Monosomy of chromosome 3 and an inflammatory phenotype occur together in uveal melanoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:505–510. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKenna KC, Kapp JA. Accumulation of immunosuppressive CD11b+ myeloid cells correlates with the failure to prevent tumor growth in the anterior chamber of the eye. J Immunol. 2006;177:1599–1608. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saio M, Radoja S, Marino M, Frey AB. Tumor-infiltrating macrophages induce apoptosis in activated CD8(+) T cells by a mechanism requiring cell contact and mediated by both the cell-associated form of TNF and nitric oxide. J Immunol. 2001;167:5583–5593. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.10.5583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kusmartsev S, Gabrilovich DI. STAT1 signaling regulates tumor-associated macrophage-mediated T cell deletion. J Immunol. 2005;174:4880– 4891. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.4880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melani C, Chiodoni C, Forni G, Colombo MP. Myeloid cell expansion elicited by the progression of spontaneous mammary carcinomas in c-erbB-2 transgenic BALB/c mice suppresses immune reactivity. Blood. 2003;102:2138–2145. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marigo I, Dolcetti L, Serafini P, Zanovello P, Bronte V. Tumor-induced tolerance and immune suppression by myeloid derived suppressor cells. Immunol Rev. 2008;222:162–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zea AH, Rodriguez PC, Atkins MB, et al. Arginase-producing myeloid suppressor cells in renal cell carcinoma patients: a mechanism of tumor evasion. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3044–3048. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmielau J, Finn OJ. Activated granulocytes and granulocyte-derived hydrogen peroxide are the underlying mechanism of suppression of t-cell function in advanced cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4756– 4760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zea AH, Rodriguez PC, Culotta KS, et al. L-Arginine modulates CD3zeta expression and T cell function in activated human T lymphocytes. Cell Immunol. 2004;232:21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berman NG, Wong WK, Bhasin S, Ipp E. Applications of segmented regression models for biomedical studies. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:E723–E732. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1996.270.4.E723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nicholson JK, Jones BM, Cross GD, McDougal JS. Comparison of T and B cell analyses on fresh and aged blood. J Immunol Methods. 1984;73:29– 40. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(84)90028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McKenna KC, Beatty KM, Vicetti MR, Bilonick RA. Delayed processing of blood increases the frequency of activated CD11b+ CD15+ granulocytes which inhibit T cell function. J Immunol Methods. 2009;341(1–2):68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2008.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baniyash M. TCR zeta-chain downregulation: curtailing an excessive inflammatory immune response. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:675–687. doi: 10.1038/nri1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodriguez PC, Quiceno DG, Ochoa AC. L-arginine availability regulates T-lymphocyte cell-cycle progression. Blood. 2007;109:1568–1573. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-031856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shenton D, Smirnova JB, Selley JN, et al. Global translational responses to oxidative stress impact upon multiple levels of protein synthesis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:29011–29021. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601545200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Otsuji M, Kimura Y, Aoe T, Okamoto Y, Saito T. Oxidative stress by tumor-derived macrophages suppresses the expression of CD3 zeta chain of T-cell receptor complex and antigen-specific T-cell responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:13119–13124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mizoguchi H, O’Shea JJ, Longo DL, Loeffler CM, McVicar DW, Ochoa AC. Alterations in signal transduction molecules in T lymphocytes from tumor-bearing mice. Science. 1992;258:1795–1798. doi: 10.1126/science.1465616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Recktenwald CV, Kellner R, Lichtenfels R, Seliger B. Altered detoxification status and increased resistance to oxidative stress by K-ras transformation. Cancer Res. 2008;68:10086–10093. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang CI, Liao JC, Kuo L. Macrophage arginase promotes tumor cell growth and suppresses nitric oxide-mediated tumor cytotoxicity. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1100–1106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xia Y, Roman LJ, Masters BS, Zweier JL. Inducible nitric-oxide synthase generates superoxide from the reductase domain. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:22635–22639. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.35.22635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fallarino F, Grohmann U, You S, et al. The combined effects of tryptophan starvation and tryptophan catabolites down-regulate T cell receptor zeta-chain and induce a regulatory phenotype in naive T cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:6752–6761. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.11.6752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang B, Pan PY, Li Q, et al. Gr-1+CD115+ immature myeloid suppressor cells mediate the development of tumor-induced T regulatory cells and T-cell anergy in tumor-bearing host. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1123–1131. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Staibano S, Mascolo M, Tranfa F, et al. Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in uveal melanoma: a link with clinical behavior? Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2006;19:171–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dworacki G, Meidenbauer N, Kuss I, et al. Decreased zeta chain expression and apoptosis in CD3+ peripheral blood T lymphocytes of patients with melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:947S–957S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sinha P, Clements VK, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Reduction of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and induction of M1 macrophages facilitate the rejection of established metastatic disease. J Immunol. 2005;174:636– 645. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng P, Corzo CA, Luetteke N, et al. Inhibition of dendritic cell differentiation and accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer is regulated by S100A9 protein. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2235–2249. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sinha P, Okoro C, Foell D, Freeze HH, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Srikrishna G. Proinflammatory s100 proteins regulate the accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J Immunol. 2008;181:4666– 4675. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Foell D, Frosch M, Sorg C, Roth J. Phagocyte-specific calcium-binding S100 proteins as clinical laboratory markers of inflammation. Clin Chim Acta. 2004;344:37–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2004.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]