Abstract

Objective

We sought to explore the association of religious and spiritual coping with multiple measures of well-being in Latinos caring for older relatives with long-term or permanent disability, either with or without dementia.

Methods

Using a multi-dimensional survey instrument, we conducted in-home interviews with 66 predominantly Mexican-American Catholic family caregivers near the US–Mexico border. We assessed caregivers' intrinsic, organizational and non-organizational religiosity with the Duke Religiosity Index, as well as Pargament's brief positive and negative spiritual coping scale to determine the association of religiosity with caregivers' mental and physical health, depressive symptomatology and perceived burden.

Results

Using regression analysis, we controlled for sociocultural factors (e.g. familism, acculturation), other forms of formal and informal support, care recipients' functional status and characteristics of the caregiving dyad. Intrinsic and organizational religiosity was associated with lower perceived burden, while non-organizational religiosity was associated with poorer mental health. Negative religious coping (e.g. feelings that the caregiver burden is a punishment) predicted greater depression.

Conclusion

Measures of well-being should be evaluated in relation to specific styles of religious and spiritual coping, given our range of findings. Further investigation is warranted regarding how knowledge of the positive and negative associations between religiosity and caregiving may assist healthcare providers in supporting Latino caregivers.

Keywords: family caregivers, Mexican Americans, religious coping, spirituality

Introduction

Projections indicate that the number of Latinos age 65 and older will increase sevenfold by the year 2050 to represent 18% of the total older population (Federal Interagency Forum on Aging Related Statistics, 2006). Consequently, there is growing interest in delivering culturally appropriate long-term care services to this population and corresponding support services to their family caregivers. Compared with other ethnic groups, aging Latinos consistently report lower rates of long-term care use, tending instead to remain at home and rely on relatives to care for them as they become less self-sufficient (Cox & Monk, 1990; Crist, 2002; Johnson, Schewibert, Albarado-Rosenmann, Pecka, & Shirk, 1997; Lim et al., 1996; Wallace & Lew-Ting, 1992). For their relatives, however, caring for a dependent older adult is not without its consequences. Latino caregivers are at a disproportionate risk for developing physical health problems and psychological distress, given the increased functional impairment and chronic illness experienced by their aging relatives (Markides, Eschbach, Ray, & Peek, 2007; Schulz & Beach, 1999; Tienda & Mitchell, 2006). With fewer economic resources than the general population (Administration on Aging, 2005; Cox & Monk, 1990), Latino family caregivers must frequently forgo work outside the home to care for older relatives (Guarnaccia, Parra, Deschams, Milstein, & Argiles, 1992).

This study explored the associations between religious coping and physical and mental well-being among Mexican-American family caregivers. While there is growing evidence for the benefits of religious and spiritual coping (Chang, Noonan, & Tennstedt, 1998; Musgrave, Allen, & Allen, 2002; Pearce, 2005; Powell, Shahabi, & Thoresen, 2003; Stuckey, 2001), Hebert, Weinstein, Martire, and Schulz's (2006) review found the effect on caregiver well-being unclear. Further, little is known about which styles of religious coping are most effective and which health outcomes are most affected (Pearce, 2005). There is little research on the association of religiosity with caregiver outcomes in Latino populations, despite evidence suggesting that Latinos use religion and spirituality as coping mechanisms more readily than non-Latinos (Adams, Aranda, Kemp, & Akagi, 2002; Calderon & Tennstedt, 1998; Coon, et al., 2004; Magaña & Clark, 1995).

Measurement of spiritual and religious constructs in research studies is frequently narrowly defined, and lacks both sophistication and dimension (Miller & Thoresen, 2003). This contributes to the inconsistent results of studies on caregiver outcomes and religion (Hebert et al., 2006). Measures can be broad and pertain to behaviors unrelated to religion; for example, church attendance may be related more to social activity or approval than to religion itself.

Religion is defined by a discrete set of practices, ideas, and beliefs that embody a community in search of sacred or transcendent meaning (Hebert et al., 2006). Religiosity studies commonly use the following classifications: (a) intrinsic, entailing internalization of basic faith principles on a day-to-day basis; (b) organized, entailing the public practice of both basic and significant religious rituals; and (c) non-organized, entailing the private practice of religious rituals (Pearce, 2005). Spirituality has been less clearly defined or operationalized in the literature (Miller & Thoresen, 2003), and is sometimes defined as the search for the transcendent, belief in something greater than oneself, and a faith that positively affirms life (Burkhardt, 1989).

Conceptual framework

Research on the associations between religiosity and health has typically investigated four areas: health practices, social support, psychological resources and belief structures (Pearce, 2005). Religion and spirituality may affect overall well-being by (1) providing a framework for understanding why bad things happen and (2) offering the prospect of an afterlife for followers (Koenig, 1994). Religious coping includes positive actions such as seeking spiritual support and benevolent religious appraisal (e.g. problems are God's will, a test or for the good) as well as negative religious coping practices (e.g. blaming God) (Pargament, 1990, 1997). In this study, we examined specific dimensions of religiosity and religious coping and their association with perceived burden, physical and mental health, and depression in Mexican-American family caregivers.

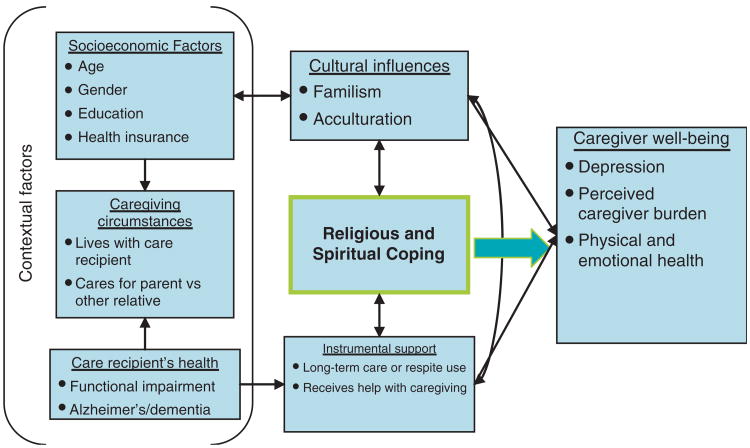

Because the factors associated with spirituality are less amenable to observation and measurement, we chose to focus on religiosity. In our conceptual framework (Figure 1), religious beliefs have a bidirectional relationship with cultural factors and instrumental support. Contextual and socioeconomic factors, such as caregiving environment and the functional status of the care recipient, have a direct impact on caregiver well-being, but may be moderated by cultural perceptions (e.g. familism and acculturation) and availability of formal and informal support. We hypothesized that some constructs of religiosity and spirituality would have a protective effect on caregivers' health and well-being, while others would impact well-being negatively.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework for religious and spiritual coping in Mexican-American family caregivers.

Research design and methods

Study design

Mexican-American family caregivers were interviewed by trained bilingual interviewers. The interviews took approximately 2 hours each and were completed in the caregivers' homes or a community site. The questionnaire was quantitative, using validated scales, and included supplementary open-ended question. Questions and scales unavailable in Spanish were translated by two bilingual experienced translators into Spanish and back-translated to English for comparison, following an adaptation of Brislin's model specifically tailored for cross-cultural research (Jones, Lee, Phillips, Zhang, & Jaceldo, 2001). A panel of translators and Mexican-American family caregivers from the community then assessed the translations in order to uncover nuanced differences in meaning and propose alternative translations.

Sample and recruitment

A convenience sample of 66 family caregivers of Mexican descent was recruited from San Diego County, California, along the US–Mexico border. We limited the target population to Mexican Americans, the largest concentration of Latinos in this region, in order to capture their unique generational and cultural norms, and migration history. Participants were recruited through word of mouth and flyers that were circulated and posted in a variety of establishments, including Catholic churches, other faith-based institutions, non-profit organizations, Adult Day Health Centers, senior nutrition centers, mobile-home parks, health fairs, public libraries and other community sites frequented by Mexican Americans. There were three eligibility criteria: respondents had to be (1) caregivers; (2) related to the care recipients (e.g. a spouse, sibling, in-law or other blood relative above the age of 50); and (3) currently providing assistance that included help with at least one activity of daily living or instrumental activity of daily living. Participants received educational materials on health and aging and caregiving in their primary language (Spanish or English), a service directory, referrals and counseling on home- and community-based resources for older adults and disabled residents of San Diego County, and a $10 gift card. The Institutional Review Board of Loma Linda University approved the study in 2006.

Measures

Religiosity

Religiosity was measured using the Duke University Religion Index (Koenig, Parkerson, & Meador, 1997; Sherman et al., 2000; Storch et al., 2004). Religious coping was measured using the short form of the Brief Religious Coping (RCOPE) Scale (Pargament, 1999). The DUREL contains five items that examine three dimensions of religiosity: organizational religiosity (OR) (i.e. public practice of religious rituals); non-organizational religiosity (NOR) (i.e. private practice of religious rites); and intrinsic religiosity (IR) (i.e. internalized religion).

Religious coping mechanisms

The six-item short form of the Brief RCOPE scale (Pargament, 1999) measures both the negative and positive aspects of spiritual and religious coping. It includes two subscales of three items each: (1) positive coping (e.g. thinking of oneself as part of a larger spiritual force; working with God as a partner; looking to God for strength, support, and guidance); and (2) negative coping (e.g. feeling that God is punishing and/or abandoning one; trying to work through the situation without God). Positive and negative religious coping patterns have different implications for health and adjustment.

Caregiver well-being

Caregiver well-being was assessed using three instruments: (a) perceived burden; (b) depressive symptomatology; and (c) mental and physical well-being. The nine-item short form of Zarit's Burden Inventory (Bedard et al., 2001) measures perceptions of caregiving as burdensome and stressful, with higher scores indicating greater burden. The shortened 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies - Depression Scale (CES-D) (Andresen, Malgrem, Carter, & Patrick 1994) was used to measure the current level of depressive symptomatology, with an emphasis on depression in the past week. Higher scores indicate greater depression. The SF-8® Health Survey (Ware, Kosinski, Dewey, & Gandek, 2001), assesses general health over the four weeks preceding the study. The SF-8® has two composite subscales: mental and physical health.

Functional status

Caregivers described the functional status of their care recipient with two scales: (a) the six-item Katz Index of Activities of Daily Living (Katz, Downs, Cash, & Grotz, 1970) and (b) the eight-item Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale (Lawton & Brody, 1969). The ADL scale assesses care recipients' independence in bathing, dressing, toileting, transferring, continence and feeding. The IADL measures skills for completing more complex tasks, such as managing finances, taking medication or driving. For both scales, higher scores indicate better functioning.

Familism and acculturation

The familism scale has 18 items, each with a 10-point rating scale. There are four subscales: familial support; familial interconnectedness; familial honor; and subjugation of self for family. Acculturation was measured with the 10-item abbreviated Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans (Dawson, Crano, & Burgoon, 1996). The questions address caregivers' language familiarity and usage, ethnic interaction, ethnic pride and identity, cultural heritage, and generational proximity.

Caregiver and care recipients' socioeconomic demographics

Care recipient questions addressed income level, residency status, insurance status and whether they had Alzheimer's or dementia and lived in a nursing home or assisted living facility. Questions about the caregivers addressed their education level, employment status, gender, age, relationship to the care recipient, current living arrangements and instrumental support from family or friends with caregiving duties. Instrumental support from friends or relatives was dichotomized as receiving or not receiving help with caregiving. Long-term care was scored according to the frequency in use of various home, community, and institutional long-term care services.

Analysis

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS version 14) was used for all analyses. After frequencies for all variables were run, missing data were coded. Descriptive statistics (frequencies, percentages, means, and ranges) were produced along with histograms, Q-Q and box plots. After normality, skewing, and broad pattern overviews were assessed, the variables were recoded and scored.

Bivariate analysis of the key religious measures (DUREL, Brief RCOPE) and their subset scales were conducted across each of the summary measures of caregiver well-being (depression, perceived burden, and health and well-being), as well as all other contextual factors. Bivariate statistics, including Pearson's correlations and Cramer's phi coefficients, were used to examine the relationships among covariates, the religiosity measures and caregiver well-being outcomes.

Variables significantly correlated with each outcome of caregiver well-being at the p≤0.15 criterion were selected for entry into a multiple linear regression model. We also included measures of religiosity in all of the predictive models, regardless of their statistical significance. The short-form brief RCOPE subscales were regressed in the same equation, given that they measure the opposite constructs of religious coping. However, each of the DUREL's three subscales (OR, NOR and IR) was regressed separately to reduce potential bias introduced from an overlap in these subscale constructs. Multicollinearity diagnostics were reviewed and, given the small sample size, variables with a variance inflation factor (VIF) >2.5 were further examined. Given the high correlation and overlap in the intended construct measures of mental health, a subscale of the SF-8® scale, and depressive symptomatology, as measured by the CES-D 10, we excluded these variables from each other's regression analysis.

Results

There were equal numbers of employed and unemployed caregivers. Half of the caregivers completed high school or a general educational development (GED) equivalent. Most caregivers were married (65.2%), female (89.4%) and ranged in age from 21 to 76 years, with a median age of 48.5. The majority of participants identified as Roman Catholic (69.7%), followed by ‘other’ Christian (22.7%) and unaffiliated (7.6%). Most care recipients self-identified as permanent legal residents or US citizens (90.9%). Insurance coverage of the care recipient varied, with most insured dually by Medicare and Medicaid (48.5%), followed by Medicare HMO or supplement (19.7%), Medicare/Veteran's benefits (9.1%) and Medi-Cal/Medicaid only (4.5%). Table 1 describes the caregiving circumstances of respondents. Caregivers were most likely to live with the care recipient and to care for relatives other than a parent. The majority of caregivers (77.3%) reported that they carry out their caregiving duties with little or no help from other relatives or friends.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the caregiving situation (n = 66).

| Variable | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Care recipient lives in a facility | |

| No | 59 (89.4) |

| Yes | 7 (10.6) |

| Care recipient has Alzheimer's or dementia | |

| No | 47 (71.2) |

| Yes | 19 (28.8) |

| Care recipient relationship to caregiver | |

| Other | 36 (54.5) |

| Parent | 30 (45.5) |

| Caregiving help from friends or family | |

| Provides most caregiving alone | 51 (77.3) |

| Receives some assistance with caregiving | 15 (22.7) |

| Caregiver lives with care recipient | |

| Yes | 49 (74.2) |

| No | 17 (25.8) |

Correlations between religiosity measures and those of caregiver well-being are shown in Table 2. The positive coping subscale of the short-form Brief RCOPE was moderately associated with all three subscales of the DUREL (i.e. organizational, non-organizational and intrinsic religiosity) with a shared variance (r2) from 17 to 26%. The DUREL scales were regressed separately from the Brief RCOPE scales in the eight predictive models to test their influence on depression, burden, physical health and mental health. Negative coping was significantly associated with higher levels of perceived caregiver burden and worse mental health. Intrinsic religiosity was significantly associated with higher levels of burden. Also noteworthy is the moderate to strong correlation (r = −0.70) between the SF-8 mental health subscale and depression, as measured by the CES-D 10. These two measures assess similar constructs. Therefore, mental health was omitted from the subsequent regression analysis predicting depression, and vice versa.

Table 2.

Bivariate analysis of religiosity measures and caregiver well-being.

| Burden | Health status | Depression | DUREL | Religious coping | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Physical | Mental | OR | NOR | IR | Positive | Negative | |||

| Perceived Burden | 1.00 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Health Status | |||||||||

| Physical | −0.35** | 1.00 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Mental | −0.45*** | 0.10 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Depression | 0.60*** | —0.35** | —0.70*** | 1.00 | – | – | – | – | – |

| DUREL | |||||||||

| Organizational (OR) | −0.22 | −0.10 | −0.06 | −0.17 | 1.00 | – | – | – | – |

| Non-organizational (NOR) | −0.06 | 0.01 | −0.09 | −0.07 | 0.47*** | 1.00 | – | – | – |

| Intrinsic (IR) | 0.28* | —0.07 | 0.08 | −0.14 | 0.41** | 0.51*** | 1.00 | – | – |

| Religious Coping | |||||||||

| Positive Coping | −0.07 | −0.13 | −0.12 | 0.00 | 0.54*** | 0.58*** | 0.77*** | 1.00 | – |

| Negative Coping | 0.38** | −0.09 | −0.21** | 0.38 | —0.18 | —0.34** | —0.32** | —0.24 | 1.00 |

Notes:

p < 0.001;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.05.

The 12 regression models for religious coping are shown in Table 3. As measured by the Brief RCOPE, religious coping had little influence on the caregiver well-being outcomes. The only exception was negative religious coping, which significantly predicted depression (β = 0.21). Table 4 illustrates the final regression models for the DUREL subscales. Higher intrinsic religiosity was significantly predictive of lesser perceived burden (p < 0.05; β=−0.23). Other factors, such as familism, mental and physical health, and living with the care recipient, were also prominent predictors. Organizational religiosity, similarly, was predictive of lower perceived burden (p < 0.05; β =−0.23). Other significant predictors of burden in this equation were caregivers' mental and physical health. Non-organizational religiosity was associated with poorer mental health (p < 0.10; β=−0.20), and was accompanied by other significant predictors, such as acculturation and perceived caregiver burden.

Table 3.

Standardized regression coefficients of religious coping (short-form Brief RCOPE) predictors of caregiver well-being.

| Burden | Depression | Health status | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Physical | Mental | |||

| β | β | β | β | |

| Burden | – | 0.49*** | -0.29 | -0.44** |

| Depression | 0.41*** | – | -0.19 | – |

| Health status | ||||

| Physical | -0.19* | -0.16 | – | – |

| Mental | – | – | – | – |

| Religious coping (RCOPE) | ||||

| Positive | -0.10 | 0.10 | 0.00 | -0.19 |

| Negative | 0.13 | 0.21* | 0.07 | -0.10 |

| Covariates | ||||

| Older age | – | – | -0.24 | – |

| Higher education | – | 0.13 | 0.21 | – |

| Lives with care recipient | 0.22* | – | – | – |

| Cares for parent vs other relative | 0.22* | – | – | – |

| Caring for person with Alzheimer's or dementia | – | -0.24* | – | 0.22 |

| Higher functioning/IADL | – | – | – | 0.19 |

| Higher familism | -0.25** | 0.12 | – | – |

| Acculturation | – | – | – | 0.12 |

| Provides most caregiving alone | – | – | —0.22 | – |

| Long-term care use | – | – | 0.20 | |

| R2 | 0.59 | 0.47 | 0.34 | 0.32 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.54 | 0.41 | 0.26 | 0.24 |

Notes:

p < 0.001;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.05.

β = standardized coefficient; IADL = Instrumental Activities of Daily Living.

Table 4.

Standardized regression coefficients of religiosity (DUREL) caregiver well-being regressed on three different indicators of religiosity.

| Model using intrinsic religiosity (IR) | Model using non-organizational religiosity (NOR) | Model using organizational religiosity (OR) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Burden | Depression | Health status | Burden | Depression | Health status | Burden | Depression | Health status | ||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Physical | Mental | Physical | Mental | Physical | Mental | |||||||

| β | β | β | β | β | β | β | β | β | β | β | β | |

| Burden | – | 0.67*** | −0.21 | −0.48** | – | 0.66*** | −0.22 | −0.48*** | – | 0.67*** | −0.22 | −0.48*** |

| Depression | – | – | −0.15 | – | – | – | −0.14 | – | – | −0.15 | – | |

| Health status | ||||||||||||

| Physical | −0.32** | – | – | – | −0.30** | – | – | – | −0.34*** | – | – | |

| Mental | −0.33** | – | – | – | −0.38*** | – | – | – | −0.36*** | – | – | – |

| Religiosity (DUREL) | ||||||||||||

| Non-organizational | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | −0.06 | −0.04 | 0.11 | −0.20† | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Organizational | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | −0.23* | 0.00 | −0.06 | −0.12 |

| Intrinsic | −0.23* | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.07 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Covariates | ||||||||||||

| Older age | – | 0.10 | −0.36* | 0.10 | – | 0.10 | −0.34** | – | – | 0.10 | −0.35** | – |

| Higher education | – | 0.15 | 0.38** | −0.15 | – | 0.13 | 0.38** | −0.21 | – | 0.15 | 0.36* | −0.20 |

| Income | – | – | −0.29* | – | −0.25 | – | – | −0.00 | −0.30* | – | ||

| Lives with care recipient | 0.19* | −0.14 | 0.14 | 0.16 | −0.13 | 0.15 | – | 0.18 | −0.14 | 0.15 | – | |

| Cares for parent vs other relative | 0.17 | −0.08 | −0.13 | 0.20 | −0.08 | – | – | 0.13 | −0.09 | −0.13 | – | |

| Caring for person with Alzheimer's/dementia | – | −0.21 | 0.19 | 0.09 | −0.21 | – | 0.19 | 0.11 | −0.21† | 0.19 | ||

| Higher familism | −0.28** | 0.12 | −0.13 | −0.18 | 0.14 | – | – | −0.21 | 0.12 | −0.14 | – | |

| Acculturation | – | −0.04 | −0.25 | 0.23 | 0.18 | – | −0.20 | 0.26* | 0.16 | −0.04 | −0.23 | 0.24† |

| Provides most caregiving alone | – | 0.10 | −0.30* | −0.09 | – | 0.09 | −0.35** | – | – | 0.10 | −0.29* | – |

| ADL | – | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.17 | – | −0.06 | – | – | – | −0.05 | – | 0.13 |

| IADL | – | – | 0.18 | – | – | – | 0.21† | – | – | −0.22 | – | |

| Long–term care use | – | −0.03 | 0.12 | 0.18 | 0.10 | – | 0.17 | 0.17 | – | −0.03 | 0.11 | 0.17 |

| R2 | 0.53 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.31 | 0.52 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.31 | 0.55 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.30 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.48 | 0.32 | 0.30 | 0.20 | 0.44 | 0.34 | 0.33 | 0.24 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.22 |

Notes:

p < 0.001;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.10;

β = standardized coefficient; ADL = Activities of Daily Living; IADL = Instrumental Activities of Daily Living.

Discussion

The authors sought to examine the association of religiosity and religious coping on family caregiver's well-being, as measured by specific constructs of mental and physical health. Although the methods utilized do not establish causality, we were able to identify important associations and assess their consistency with the conceptual framework described in Figure 1.

Broadly, we found religiosity and religious coping to be both positively and negatively related to the mental health and burden of caregivers, but found no association with caregiver's subjective physical health. Caregivers reporting higher levels of intrinsic and organizational religiosity were less likely to perceive their caregiving role as burdensome, while those exhibiting greater levels of non-organizational religiosity reported worse mental health.

Non-organizational religiosity pertains to the private practice of religious rites, such as private prayer, Bible study and meditation. Without the benefits of social support possibly gained from organizational religiosity and the camaraderie and emotional and instrumental support derived from church attendance, it is plausible that mental health suffers. Poorer mental health is also associated with greater caregiver burden. Thus, poorer mental health may be more prominent among individuals unable to exercise their religious practices in a congregation due to their increased caregiver burden and responsibilities. This relationship may be bidirectional, where depressed caregivers may find it more difficult to participate in religious activities. Alternatively poor mental health may lead one to seek relief through prayer, bible study and meditation, and hence explains the association with non-organizational religiosity. The positive relationship between intrinsic religiosity, which refers to feeling the presence of the divine in one's life, and lesser burden is intuitive. Intrinsic religiosity represents caregivers' strongly held beliefs and faith, which may alter their perception of burden. We also assessed whether caregivers considered their caregiving responsibilities to be a punishment from God, whether they felt that God had abandoned them, and if they relied less on God in their decision-making. Not surprisingly, those with higher levels of negative religious coping also reported higher levels of depressive symptoms.

This study supports previous research findings demonstrating that caregivers may use their religiosity and spirituality as a way of coping with stress and coming to terms with their circumstances (Chang, et al., 1998; Pearce, 2005; Stolley, Buckwalter, & Koenig, 1999). More so, it distinguishes between the forms of religious coping that have been traditionally linked with good health, and their relationship with physical and emotional aspects of well-being. This study demonstrates that more longitudinal studies are needed to ferret out the direction of causation that is operating.

The study demonstrates that, although some forms of coping may be beneficial, other forms, such as negative religious coping, may be harmful. This study is notable for its focus on Latinos, a largely understudied segment of the population of caregivers, and also for its use of specific constructs of religiosity, such as positive and negative religious coping, as suggested by current research in this area (Hebert et al., 2006; Pearce, 2005).

There are limitations in generalizing the results of this study. Respondents self-selected to participate in the study, and the sample size was small. Because of the latter factor, we elected to do no correction for the bias inherent in performing numerous statistical tests. However, participant demographics reflect the general demographic makeup of the region from which the sample was drawn. For instance, consistent with national statistics, almost 70% of the study sample were Roman Catholic (Pew Hispanic Center, 2007). Although the findings may be only reflective of the Latino population along the California/Mexico border region, this study is relevant to caregiver well-being as a whole. The participants of the study were mostly low to middle income, first-generation immigrants and women. As such, caution is warranted in applying these findings to all Latino populations. The cross-sectional design employed also limits our ability to longitudinally assess the impact that the progression of care recipients' disability and illness over time may have on caregivers' well-being. Lastly, the conceptual framework and analysis in this study is restricted to caregiving related stressors, and thus did not control for contextual extraneous stressors.

Conclusion and implications for practice

In the context of healthcare research, this study supports the need for (a) improved conceptualization of religiosity and spirituality; (b) better assessment of religious coping and its role in caregiving; (c) more qualitative data and longitudinal studies of religious coping; (d) further study of negative outcomes of religious coping, such as depression or other stress-related disorders, which may act as warning signals to healthcare workers; (e) assessment of the long-term efficacy of religious coping in terms of mental and physical health; and (f) examination of other caregiver outcomes such as guilt, forgiveness and hope for future spiritual rewards (Hebert et al., 2006; Pearce, 2005).

Our research supports the notion that religious and spiritual beliefs of caregivers are pertinent to their ability to adapt to physical and mental health problems, even though some aspects of their beliefs may have an unintended negative impact.

Although initiatives to support caregivers are growing, few programs have addressed the unmet needs, and spiritual and special concerns of ethnic minorities, including Latinos. Primary care providers who work with family caregivers need not be religious as a prerequisite, nor resort to encouraging or invoking religious ideals in caregivers. Providers can nevertheless help caregivers connect with the positive aspects of their existing belief system or facilitate interactions with the appropriate religious clergy or leadership in order to extend help and necessary services to stressed caregivers.

References

- Adams B, Aranda M, Kemp B, Akagi K. Ethnic and gender differences in distress among Anglo-American, African-American, Japanese-American, and Mexican-American spousal caregivers of persons with dementia. Journal of Clinical Geropsychology. 2002;4:279–301. [Google Scholar]

- Administration on Aging. A profile of older Americans: 2005. 2005 Retrieved on September 20, 2007 from: http://www.aoa.gov/PROF/Statistics/profile/2005/2005profile.pdf.

- Andresen EM, Malgrem JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale) American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1994;10:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedard M, Molloy DW, Squire L, Dubois S, Lever JA, O'Donnell M. The Zarit burden interview: A new short version and screening version. Gerontologist. 2001;41:652–657. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.5.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt M. Spirituality, an analysis of the concept. Holistic Nurse Practice. 1989;3(3):69–77. doi: 10.1097/00004650-198905000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderon V, Tennstedt S. Ethnic differences in expression of caregiver burden. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 1998;30(1/2):159–179. [Google Scholar]

- Chang BH, Noonan AE, Tennstedt SL. The role of religion/spirituality in coping with caregiving for disabled elders. Gerontologist. 1998;38:463–470. doi: 10.1093/geront/38.4.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coon DW, Rubert M, Solano N, Mausbach B, Kraemer H, Arugelles T, et al. Well-being, appraisal, and coping in Latina and Caucasian female dementia caregivers: Findings from the REACH study. Aging & Mental Health. 2004;8:330–345. doi: 10.1080/13607860410001709683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox C, Monk A. Minority caregivers of dementia victims: A comparison of Black and Hispanic families. The Journal of Applied Gerontology. 1990;9:341–351. [Google Scholar]

- Crist JD. Mexican American elders' use of skilled home care nursing services. Public Health Nursing. 2002;19:366–376. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2002.19506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson EJ, Crano WD, Burgoon M. Refining the meaning and measurement of acculturation: Revisiting a novel methodological approach. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 1996;20:97–114. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Interagency Forum on Aging Related Statistics. Older Americans Update 2006: Key indicators of well-being. 2006 Retrieved on December 15, 2007 from: http://www.agingstats.gov/agingstatsdotnet/Main_Site/Data/2006_Documents/OA_2006.pdf.

- Guarnaccia PJ, Parra P, Deschams A, Milstein G, Argiles N. Si Dios quiere: Hispanic families' experiences of caring for a seriously mentally ill family member. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 1992;16:187–217. doi: 10.1007/BF00117018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert RS, Weinstein E, Martire LM, Schulz R. Religion, spirituality and the well-being of informal caregivers: A review, critique, and research prospectus. Aging and Mental Health. 2006;10:497–520. doi: 10.1080/13607860600638131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RA, Schewibert VL, Albarado-Rosenmann P, Pecka G, Shirk N. Residential preferences and eldercare views of Hispanic elders. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology. 1997;12:91–107. doi: 10.1023/a:1006503202367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PS, Lee JW, Phillips LR, Zhang XE, Jaceldo KB. An adaptation of Brislin's translation model for cross-cultural research. Nursing Research. 2001;50(5):300–304. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200109000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz S, Downs TD, Cash HR, Grotz RC. Index of Activities of Daily Living. The Gerontologist. 1970;1:20–301. doi: 10.1093/geront/10.1_part_1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG. Aging and God: Spiritual paths to mental health in midlife and later years. New York, NY: Haworth Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, Parkerson GR, Meador KG. Religion index for psychiatric research: A 5-item measure for use in health outcome studies. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154:885–886. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.6.885b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton M, Brody E. Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim YM, Luna I, Cromwell SL, Phillips LR, Russell CK, Torres De Arton E. Toward a cross-cultural understanding of family caregiving burden. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1996;18:252–266. doi: 10.1177/019394599601800303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magaña A, Clark NM. Examining a paradox: Does religiosity contribute to positive birth outcomes in Mexican-American populations? Health Education Quarterly. 1995;2:97–109. doi: 10.1177/109019819502200109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markides KS, Eschbach K, Ray L, Peek K. Census disability rates among older people by race/ ethnicity and type of Hispanic origin. In: Angel JL, Whitfield KE, editors. The health of aging Hispanics: The Mexican-origin population. New York: Springer; 2007. pp. 26–39. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Thoresen CE. Spirituality, religion, and health: An emerging research field. American Psychologist. 2003;1:24–35. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musgrave C, Allen C, Allen G. Spirituality and health for women of color. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:557–560. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI. God help me: Toward a theoretical framework of coping for the psychology of religions. In: Lynn ML, Moberg DO, editors. Research in the Social Scientific Study of Religion. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press; 1990. pp. 195–224. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI. The psychology of religion and coping. New York: Guilford Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI. Religious/spiritual coping. In: Fetzer Institute, editor. Multidimensional measurement of religiousness/spirituality for use in health research: A report of the Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging Working Group. Kalamazoo, MI: Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging; 1999. pp. 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce M. A critical review of the forms and value of religious coping among informal caregivers. Journal of Religion and Health. 2005;44:81–119. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Hispanic Center. Changing faiths: Latinos and the transformation of American religion. 2007 Retrieved on July 2, 2007 from: http://pewhispanic.org/files/reports/75.pdf.

- Powell LH, Shahabi L, Thoresen CE. Religion and spirituality: Linkages to physical health. American Psychologist. 2003;58:36–52. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282:2215–2219. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.23.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman AC, Plante TG, Simonton S, Adams DC, Harbison C, Burris SK. A multidimensional measure of religious involvement for cancer patients: The Duke Religious Index. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2000;8:102–109. doi: 10.1007/s005200050023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolley JM, Buckwalter KC, Koenig HG. Prayer and religious coping for caregivers of persons with Alzheimer's disease and related disorder. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 1999;14:181–191. [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Roberti JW, Heidgerken AD, Stroch JB, Lewin AB, Killiany EM, et al. The Duke Religion Index: A psychometric investigation. Pastoral Psychology. 2004;53:175–181. [Google Scholar]

- Stuckey JC. Blessed assurance: The role of religion and spirituality in Alzheimer's disease caregiving and other significant life events. Journal of Aging Studies. 2001;15:69–85. [Google Scholar]

- Tienda M, Mitchell F. Hispanics and the future of America. New York: National Academy Press; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace S, Lew-Ting C. Getting by at home: Community-based long-term care of the elderly. The Western Journal of Medicine. 1992;157:337–344. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Kosinski M, Dewey JE, Gandek B. A manual for users of the SF-8 Health Survey. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Incorporated; 2001. [Google Scholar]