Abstract

Background

Previous studies have examined participation in specific leisure-time physical activities (PA) among US adults. The purpose of this study was to identify specific activities that contribute substantially to total volume of leisure-time PA in US adults.

Methods

Proportion of total volume of leisure-time PA moderate-equivalent minutes attributable to 9 specific types of activities was estimated using self-reported data from 21,685 adult participants (≥ 18 years) in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2006.

Results

Overall, walking (28%), sports (22%), and dancing (9%) contributed most to PA volume. Attributable proportion was higher among men than women for sports (30% vs. 11%) and higher among women than men for walking (36% vs. 23%), dancing (16% vs. 4%), and conditioning exercises (10% vs. 5%). The proportion was lower for walking, but higher for sports, among active adults than those insufficiently active and increased with age for walking. Compared with other racial/ethnic groups, the proportion was lower for sports among non-Hispanic white men and for dancing among non-Hispanic white women.

Conclusions

Walking, sports, and dance account for the most activity time among US adults overall, yet some demographic variations exist. Strategies for PA promotion should be tailored to differences across population subgroups.

Keywords: epidemiology, physical activity, public health, surveillance, public health

Introduction

Regular physical activity provides many health benefits.1 To obtain substantial health benefits, the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans recommend adults should do at least 150 minutes (2 hours and 30 minutes) a week of moderate-intensity, or 75 minutes (1 hour and 15 minutes) a week of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity, or an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity aerobic activity.2 Despite the health benefits, only about half of US adults meet the recommended guideline for aerobic physical activity.3

People may meet the aerobic physical activity guideline by participating in a variety of physical activities. People may engage in aerobic physical activity for different purposes (e.g., for work, transportation, or leisure) and they can also participate in a wide range of moderate and vigorous-intensity activities. Although for most people, they probably have the greatest control over which activities they choose to spend their time in during leisure.4 Several studies have examined the prevalence of participation in specific types of physical activities primarily during leisure time among US adults, overall and by demographic subgroups.5–13 These studies show walking is the most popular leisure-time physical activity among all adults. Bicycling, yard work, and dance are also popular activities. Most of these studies also found differences by demographic subgroups (e.g., sex, age, and race/ethnicity).5,6,8–10,12,13 For example, more men report participation in golf, basketball, running, and yard work than women, while more women report participation in walking, aerobics, and dance than men.8–10,13 Popular activities may be more likely to be accepted; therefore, knowing in which activities adults participate is useful for program and intervention efforts designed to increase physical activity.

Ranking activities by their relative contributions to the total volume of leisure time physical activity in the population would help identity activities in which many people not only participate but also spend more of their time. From a public health perspective, health benefits accumulate with increasing amounts of physical activity.1 Common activities identified by the percentage of total volume attributable to the activities may be more closely related to public health impact in the population than those by prevalence of participation alone.

Activity rankings and patterns by demographic characteristics based on population activity volume may differ compared with those based on prevalence of participation. To our knowledge, only one study has reported the relative contribution in terms of volume of specific activities and reported it by body weight status. The study reported that walking accounted for the largest proportion of the total duration of moderate-intensity physical activity and running accounted for the largest proportion of the vigorous-intensity activity among normal weight adults.7 This study did not examine patterns of activity by demographic characteristics and did not compare the patterns between those not active enough to meet aerobic guideline and those who are active enough to meet the guideline. This information may inform programming and planning efforts to target specific population subgroups that are most in need of physical activity promotion.

The purpose of the current analysis is to identify specific leisure-time aerobic activities that contribute substantially to the total volume of leisure-time physical activity in the general population and population subgroups. Specifically, the analysis will answer the following questions: a) What percentage of the total volume of leisure-time physical activity is attributable to each specific type of leisure-time activity (attributable proportion) among US adults? b) Does the attributable proportion differ among population subgroups? and c) Does the attributable proportion differ by level of leisure-time physical activity?

Methods

Study Sample

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) is a nationally representative sample of the civilian, non-institutionalized US population and collects data from survey participants via household interviews and physical examinations in mobile examination centers. Detailed information about NHANES procedures is available elsewhere.14 The current analysis used data from 4 NHANES survey cycles conducted from 1999–2006 in which information on specific types of leisure-time physical activities was collected. Overall interview response rates (i.e., percentage of eligible survey participants who were actually interviewed) ranged from 79% (the lowest) in 2003–2004 to 84% (the highest) in 2001–2002.15 Of the 22,624 survey participants aged 18 years and older, data for 939 participants were excluded due to missing data (n=79) or because they reported they were unable to be physically active (n=860). Therefore, data for 21,685 survey participants were included in the current analysis. The National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Research Ethics Review Board approved the survey protocols, and all adults who participated in the survey provided their informed consent.

Physical Activity

The NHANES physical activity questionnaire used from 1999 through 200616, indirectly validated through similar population-based surveys,17 included a series of questions on participation in leisure-time physical activities that queried the type, intensity, frequency, and duration of activities. Survey participants were asked to identify the specific types of vigorous- and moderate-intensity activities in which they had participated for at least 10 minutes at a time over the past 30 days and were then asked how frequently and how long they performed each identified activity. Survey participants were instructed that vigorous-intensity activities cause heavy sweating, or large increases in breathing or heart rate; moderate-intensity activities cause only light sweating or a slight to moderate increase in breathing or heart rate.

Many specific activities were included in lists of both vigorous- and moderate-intensity activities. For these activities, the participant reported whether it was of moderate- or vigorous-intensity. Leisure-time gardening and yard work were only included in 1999–2002 survey cycles. Of the 48 surveyed leisure-time physical activities, 5 non-aerobic activities (i.e., push-ups, sit-ups, stretching, weight lifting, and yoga) were excluded from the analysis. To facilitate comparison across demographic subgroups and to account for small percentages in participation, the resulting 43 aerobic activities were grouped into 9 activity categories according to classifications in the 2011 Compendium of Physical Activities.18 Thus, conditioning exercises includes stair climbing, treadmill, and jumping rope; bicycling includes bicycling only; dancing includes aerobics and dance; fishing/hunting activities includes fishing and hunting; running includes running and jogging; sports includes baseball, basketball, bowling, boxing, cheerleading and gymnastics, children’s games such as dodgeball or kickball, football, frisbee, golf, hockey, horseback riding, martial arts, racquetball, rollerblading, skateboarding, skating, soccer, softball, tennis, trampoline jumping, volleyball, and wrestling; walking includes hiking and walking; water activities includes kayaking, rowing, surfing, and swimming; winter activities includes cross country skiing and downhill skiing. Unspecified activity (reported as “other” activity) was not grouped into an activity category. Because lawn/garden activities include gardening and yard work and were only queried as specific activities during 1999–2002, lawn/garden activities were also classified as other activity.

Using activity frequency and duration data, activity-specific moderate-intensity equivalent minutes/week for each individual was calculated as the sum of the moderate-intensity activity minutes/week and twice the vigorous-intensity activity minutes/week. Minutes for vigorous-intensity activity were given twice the credit of moderate-intensity minutes because energy expended through vigorous-intensity activity is roughly twice the amount expended through moderate-intensity activity.1,2 Total minutes of moderate-intensity equivalent physical activity per week was calculated as the sum of activity-specific moderate-intensity equivalent minutes/week for all activities reported. Similar to national objectives, the level of leisure-time aerobic physical activity was categorized as inactive (no reported leisure-time physical activity of at least 10 minutes at a time in past 30 days), insufficiently active (some activity, but not enough to meet the active definition), or active (≥ 150 minutes/week of total moderate-intensity equivalent physical activity – sufficient to meet aerobic guidelines)2.

Demographics

NHANES survey participants were classified by sex, age (18–29, 30–44, 45–64, or ≥ 65 years), and race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Mexican American, or other). The race/ethnicity group indicated as “other” is a heterogeneous group with a limited sample size. Although this group is included in overall estimates, estimates by race/ethnicity for this group are not reported separately.

Statistical Analysis

Data from the 4 NHANES cycles conducted from 1999 through 2006 were combined into a single cross-sectional dataset to obtain a large enough sample to report statistics related to the time spent in individual activities by subgroups. Ratio estimates for the attributable proportion of each activity to total volume of physical activity were estimated as the sum of activity-specific moderate-intensity equivalent minutes/week divided by the sum of total activity moderate-intensity equivalent minutes/ week (times 100%). Because of differences in participation between men and women,8,13 the proportion of activity attributable to each specific activity was stratified by sex. Orthogonal polynomial contrasts and pairwise t-tests were used to identify demographic differences in the attributable proportions of leisure-time activity categories. A P value of < .05 was considered statistically significant. Participants who reported no leisure time physical activity provide no minutes per week for the numerator (minutes per week of the specific activity) or denominator (minutes per week of all activities) and are, thus, inherently excluded from analyses. The sample analyzed for the attributable proportion of specific activities included 12,277 adults. Although other, non-specific activities were included in the total minutes of physical activity, we did not examine differences by demographic characteristics in this category. Because lawn and garden activities were included as additional specific activities in 1999–2002, a supplemental analysis was performed to examine the attributable proportion for lawn and garden activities based on those years only. SAS-callable SUDAAN, release 11.0.0 (RTI International, Research Triangle Park, NC) was used for the analyses. A combined interview weight for 1999–2006 was created using the method specified by NCHS,19 and used in all analyses.

Results

The sample included 21,685 participants aged 18 years or older (Table 1). When the sample was weighted, the majority were aged 30−64 years, non-Hispanic white, and had at least some college education. Nearly two-thirds (63%) reported at least some leisure-time physical activity, thus providing information to address the study questions. More participants who reported no leisure time activity were women, older adults, from minority race/ethnic groups, and less educated compared to participants who reported at least some physical activity.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics, NHANES 1999–2006

| Characteristic | Total1 | Insufficiently Active and Active2 |

Inactive2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Weighted % (SE)3 |

n | Weighted % (SE)3 |

n | Weighted % (SE)3 |

|

| Total | 21685 | 100% (−) | 12277 | 100% (−) | 9408 | 100% (−) |

| Sex* | ||||||

| Men | 10395 | 48.3 (0.3) | 6169 | 49.9 (0.5) | 4226 | 45.6 (0.6) |

| Women | 11290 | 51.7 (0.3) | 6108 | 50.1 (0.5) | 5182 | 54.4 (0.6) |

| Age (years)* | ||||||

| 18–29 | 6139 | 22.4 (0.6) | 4091 | 25.4 (0.8) | 2048 | 17.2 (0.5) |

| 30–44 | 5115 | 30.7 (0.7) | 3050 | 31.8 (0.9) | 2065 | 29.0 (0.7) |

| 45–64 | 5533 | 31.7 (0.6) | 2958 | 30.8 (0.8) | 2575 | 33.3 (0.8) |

| 65+ | 4898 | 15.1 (0.5) | 2178 | 12.0 (0.5) | 2720 | 20.5 (0.7) |

| Race/ethnicity* | ||||||

| Mexican American | 5052 | 7.7 (0.7) | 2375 | 5.9 (0.5) | 2677 | 10.8 (1.0) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 10328 | 70.8 (1.4) | 6550 | 75.5 (1.3) | 3778 | 62.9 (1.8) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 4559 | 11.1 (0.9) | 2370 | 9.1 (0.8) | 2189 | 14.5 (1.3) |

| Other | 1746 | 10.3 (1.0) | 982 | 9.5 (0.9) | 764 | 11.8 (1.3) |

| Education* | ||||||

| < High school graduate | 7069 | 20.1 (0.6) | 2829 | 13.5 (0.6) | 4240 | 31.4 (0.8) |

| High school graduate | 5371 | 26.1 (0.6) | 2966 | 23.7 (0.7) | 2405 | 30.0 (0.8) |

| Some college | 5558 | 29.8 (0.5) | 3635 | 32.0 (0.7) | 1923 | 26.2 (0.7) |

| College graduate | 3687 | 24.0 (0.9) | 2847 | 30.8 (1.1) | 840 | 12.4 (0.6) |

| Physical Activity Level2 | ||||||

| Inactive | 9408 | 37.0 (0.8) | n/a | n/a | 9408 | 100 (−) |

| Insufficiently active | 4574 | 23.1 (0.4) | 4574 | 36.6 (0.7) | n/a | n/a |

| Active | 7703 | 39.9 (0.8) | 7703 | 63.4 (0.7) | n/a | n/a |

Of the 22,624 survey participants aged 18 years and older, data from 939 participants were excluded due to missing data (n=79) or because they were unable to be physically active (n=860)

Physical activity level measured in moderate-intensity equivalent minutes/week of leisure-time physical activity; inactive indicates no reported leisure-time physical activity of at least 10 minutes in past 30 days ; insufficiently active indicates some activity, but <150 minutes/week; and active indicates activity ≥ 150 minutes/week.

Standard error (SE)

Significant (p < 0.05) association between participant characteristic and physical activity level (insufficiently active and active compared to inactive)

Walking accounted for the largest proportion (28%) of the total volume of activity. Sports (22%) and dancing (9%) followed walking in attributable proportion of total activity volume (Table 2). Results from the supplemental analysis found, when calculated based on 1999 – 2002 data, the attributable proportion for lawn/garden activities was 14%. However, walking (29%) and sports (21%) remained the top activities. Although the ranking for dance changed, the attributable proportion remained at 9%)

Table 2.

Proportion of Population Leisure-Time Physical Activity Volume Attributable1 to Specific Types of Activities, Overall and by Sex, NHANES 1999 – 2006.

| Activity Category | Total (n=12277) |

Men (n=6169) |

Women (n=6108) |

|---|---|---|---|

| % (SE)2 | % (SE)2 | % (SE)2 | |

| Bicycling3 | 7.7 (0.4) | 8.6 (0.5) | 6.4 (0.5) |

| Conditioning exercises3 | 7.3 (0.5) | 5.4 (0.6) | 10.2 (0.7) |

| Dancing3 | 8.9 (0.4) | 4.4 (0.3) | 15.5 (0.8) |

| Fishing/hunting3 | 3.9 (0.4) | 5.6 (0.6) | 1.3 (0.3) |

| Running3 | 7.8 (0.4) | 8.5 (0.5) | 6.6 (0.5) |

| Sports3 | 22.4 (0.7) | 30.0 (1.0) | 11.4 (0.7) |

| Walking3 | 28.1 (0.8) | 23.0 (0.8) | 35.5 (1.4) |

| Water activities3 | 4.4 (0.4) | 4.0 (0.5) | 5.1 (0.5) |

| Winter activities | 0.9 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.3) | 0.8 (0.2) |

| Other activities4 | 8.6 (0.8) | 9.5 (0.8) | 7.2 (1.0 |

The proportion of total volume (moderate-equivalent minutes) attributable to specific activities is defined as the population ratio of time spent in the specific activity divided by the time spent in all activities; inactive group (n=9408) is excluded from the table as it has no activities to report and contributes no minutes to the numerator or denominator; Inactive indicates no reported leisure-time physical activity of at least 10 minutes in past 30 days

Standard error.

Significantly different (p<0.05) between men and women.

Other activities is not a defined activity category; estimates are only shown as is included because it contributes to the total leisure-time physical activity volume; differences between men and women were not examined

The attributable proportion differed significantly by sex (P < .05) for all but winter activities and other activities not specified (Table 2). Among men, sports (30%) accounted for the largest proportion of the total volume of activity, followed by walking (23%) and bicycling (9%). Among women, walking (36%) contributed most to the total volume followed by dancing (16%), sports (11%), and conditioning exercises (10%).

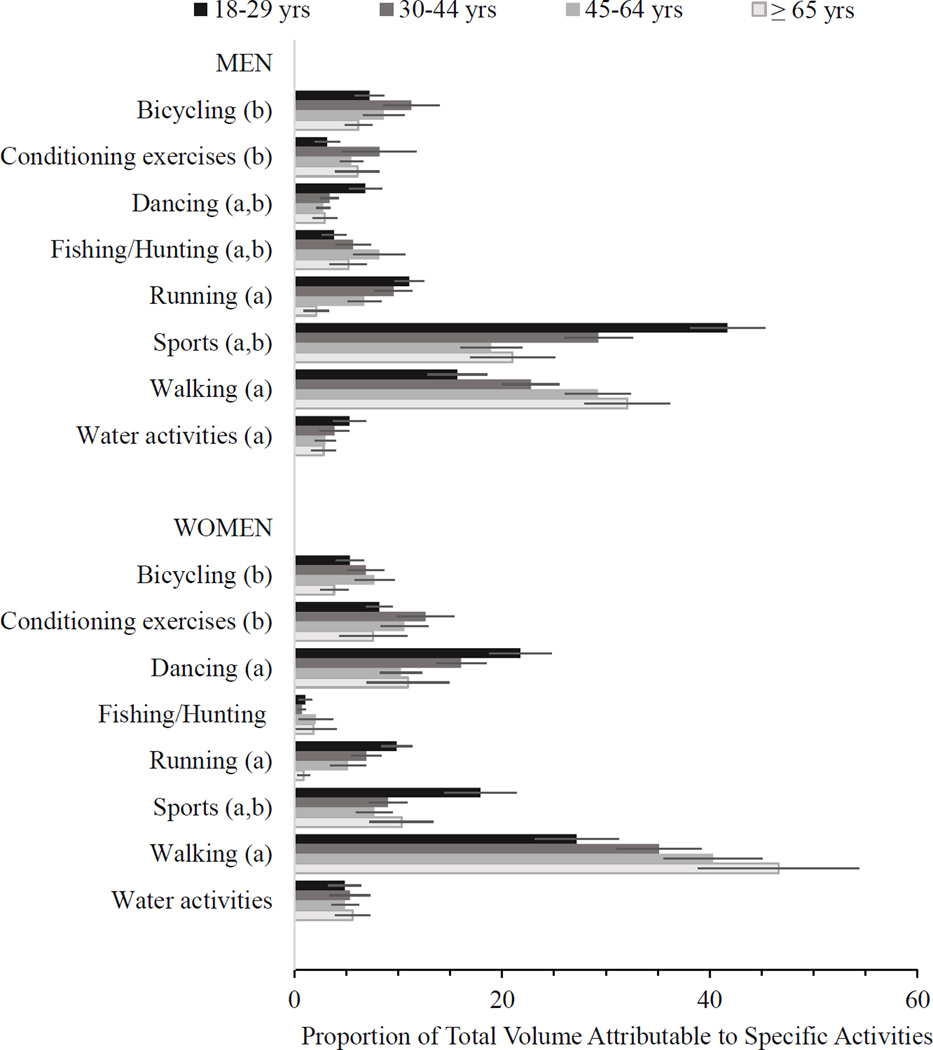

Trends in the attributable proportion by age differed for specific activities (Figure 1). Among men, sports and walking accounted for the largest proportion of the total volume of activity for the 18–44 year age groups and ≥ 45 years age groups, respectively. Among women, walking accounted for the largest proportion of the total volume of leisure-time physical activity in all age groups. A significant increasing linear trend by age group was observed among men and women for walking. A decreasing linear trend by age group was observed among men and women for running. The attributable proportion for sports and dancing decreased from the 18–29 year age group to the 45–64 year age group among both men and women. The attributable proportion for bicycling and conditioning exercises initially increased and then decreased with age.

Figure 1.

Proportion of Total Volume of Leisure-Time Physical Activity Attributable to Specific Types of Activities, by Sex and Age, NHANES 1999 – 2006

Note: Error bars represent lower and upper bounds of the 95% confidence interval; activities with total proportion < 1% (winter activities and other activities not specified) are not presented.

a. Linear trend of attributable proportion by age significant (P < .05).

b. Quadratic trend of attributable proportion by age significant (P < .05).

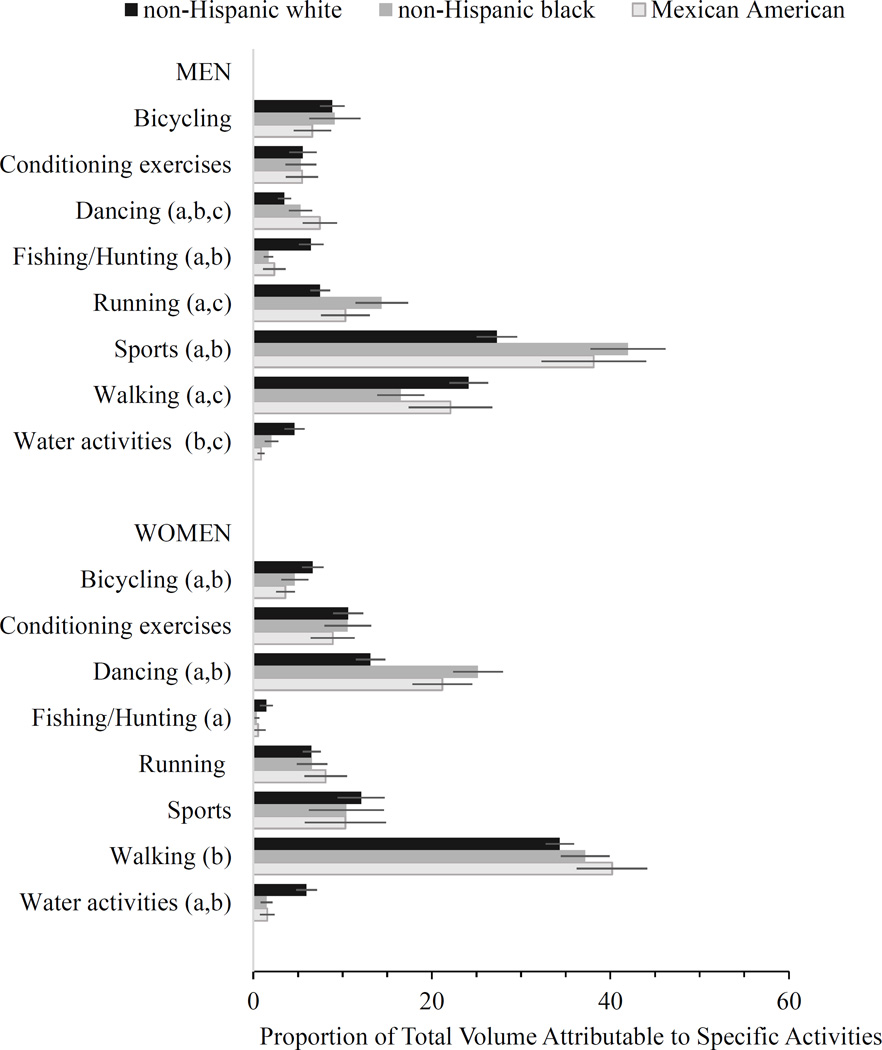

The attributable proportion for certain activities varied significantly by race/ethnicity (Figure 2). Among men in all 3 racial/ethnic groups, sports accounted for the largest proportion of the total volume of activity, while walking ranked 2nd, after sports. Among women, walking accounted for the largest proportion of the total volume of activity in all three racial/ethnic groups, followed by dancing. For the top two activities among men, the attributable proportion for sports was lower among non-Hispanic whites than non-Hispanic blacks and Mexican Americans and the attributable proportion for walking was higher among non-Hispanic whites than non-Hispanic blacks. Among women, the attributable proportion for walking was lower among non-Hispanic whites compared with Mexican Americans and the attributable proportion for dancing was lower among non-Hispanic whites compared with non-Hispanic blacks and Mexican Americans.

Figure 2.

Proportion of Total Volume of Leisure-Time Physical Activity Attributable to Specific Types of Activities, by Sex and Race/Ethnicity, NHANES 1999 – 2006.

Note: Error bars represent lower and upper bounds of the 95% confidence interval; activities with total proportion < 1% (winter activities and other activities not specified) are not presented; heterogeneous groups (other race or multi-racial) are not presented.

Estimates significantly different (P < .05) between: a) non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic blacks; b) non-Hispanic whites and Mexican Americans; and c) non-Hispanic blacks and Mexican Americans.

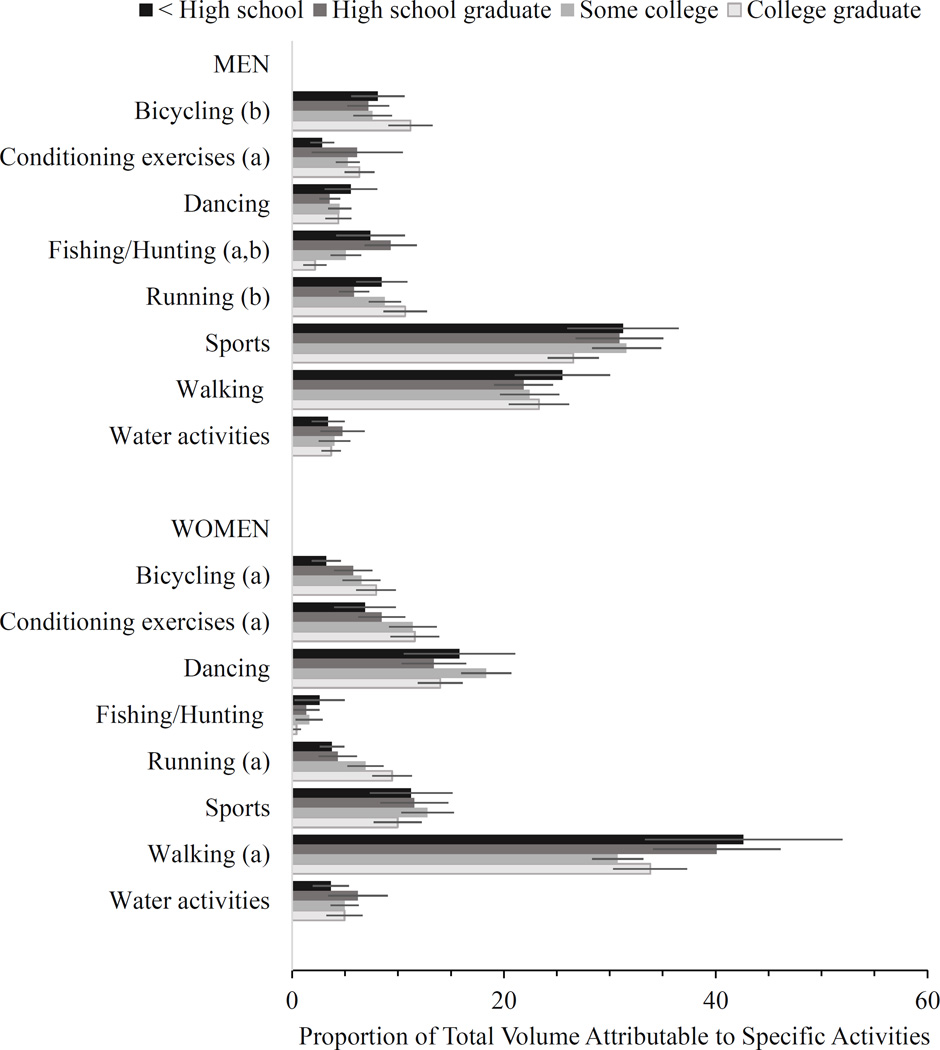

Trends in the attributable proportion by education differed for specific activities (Figure 3). Among men, sports and walking accounted for the largest proportion of the total volume of activity for all education groups, respectively. Among women, walking and dancing accounted for the largest proportion of the total volume of leisure-time physical activity in all education groups. Although a significant increasing linear trend by education group was observed among men and women for condition exercises, the trends in other activities were different between men and women. For women, a significant increasing linear trend was also observed for bicycling and running, whereas for men, the quadratic trend decreased before increasing by education. For women, a significant decreasing linear trend was observed for walking. Among men, and not women, there was a significant linear and quadratic trend for fishing and hunting with men who were a high school graduate having the highest attributable proportion.

Figure 3.

Proportion of Total Volume of Leisure-Time Physical Activity Attributable to Specific Types of Activities, by Sex and Education, NHANES 1999 – 2006.

Note: Error bars represent lower and upper bounds of the 95% confidence interval; activities with total proportion < 1% (winter activities and other activities not specified) not presented.

a. Linear trend of attributable proportion by age significant (P < .05).

b. Quadratic trend of attributable proportion by age significant (P < .05).

The attributable proportion for many activities differed significantly by leisure-time physical activity level (Table 3). Compared with men who were active, men who were insufficiently active reported higher attributable proportions for walking and dancing, and lower attributable proportions for sports. Similar patterns were observed among women for walking and sports. However, women who were insufficiently active reported similar attributable proportion for dancing, but lower attributable proportions for running, conditioning exercises, fishing and hunting, and water activities, compared with women who were active.

Table 3.

Proportion of Population Leisure-Time Physical Activity Volume Attributable to Specific Types of Activities, by Sex and Leisure-Time Physical Activity Level, NHANES 1999 – 2006.

| Sex | Insufficiently Active1 | Active1 |

|---|---|---|

| Activity Category | % (SE)2 | % (SE)2 |

| Men (n=6169) | ||

| Bicycling | 9.7 (0.9) | 8.5 (0.6) |

| Conditioning exercises | 6.9 (0.9) | 5.4 (0.6) |

| Dancing* | 6.3 (0.7) | 4.3 (0.4) |

| Fishing/hunting | 4.6 (0.6) | 5.7 (0.6) |

| Running | 8.1 (0.9) | 8.6 (0.5) |

| Sports* | 19.7 (1.3) | 30.5 (1.0) |

| Walking* | 34.5 (1.6) | 22.4 (0.8) |

| Water activities | 3.9 (0.6) | 4.0 (0.5) |

| Winter activities | 0.4 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.3) |

| Other activities3 | 5.9 (0.9) | 9.7 (0.9) |

| Women (n=6108) | ||

| Bicycling | 5.5 (0.5) | 6.4 (0.6) |

| Conditioning exercises* | 6.7 (0.8) | 10.5 (0.7) |

| Dancing | 14.2 (1.0) | 15.6 (0.8) |

| Fishing/hunting* | 0.5 (0.1) | 1.4 (0.3) |

| Running* | 2.8 (0.4) | 7.0 (0.5) |

| Sports* | 6.7 (0.6) | 11.8 (0.8) |

| Walking* | 54.2 (1.4) | 33.9 (1.6) |

| Water activities* | 3.5 (0.5) | 5.2 (0.5) |

| Winter activities | 0.9 (0.3) | 0.8 (0.2) |

| Other activities3 | 5.0 (0.7) | 7.4 (1.1) |

Inactive group (n=9408) is excluded from the table as it has no activities to report and contributes no minutes to the numerator or denominator; inactive indicates no reported leisure-time physical activity of at least 10 minutes in past 30 days ; insufficiently active indicates some activity, but <150 minutes/week; and active indicates activity ≥ 150 minutes/week

Standard error.

Other activities is not a defined activity category and includes lawn and garden specific activities from 1999–2002; other activities are included because they contributes to the total leisure-time physical activity volume

Significantly different (p<0.05) between those who were insufficiently active and those who were active.

Discussion

The current analysis examined the attributable proportion of specific leisure-time physical activities to the volume of leisure-time physical activity in the US. We found walking (28%), sports (22%), and dance (9%) had the largest attributable proportions. Substantial variations, however, exist by demographic subgroups and among adults with different levels of physical activity. Tailoring strategies for physical activity promotion to account for these differences may help to maximize the success of these efforts.

Our findings for what activities had the largest attributable proportion to the volume of physical activity obtained by subgroup can be used to inform programs being promoted within different demographic groups. For example, walking and gardening may be activities to consider when developing programs to promote physical activity among older adults. Mall walking programs, in particular, help to reduce some of the barriers to being active among older adults by offering the following: climate controlled areas to walk, on-site security personnel, flat and well-lit paths, and social support through the presence of other walkers.20 Gardening programs provide opportunities for older adults to be active.21

Our findings of attributable proportions are generally consistent with patterns observed in studies of the prevalence of participation alone.8–11,13,22,23 Many studies have identified walking, bicycling, and dance/aerobics as the most common activities based on prevalence of participation.8–11,13,22,23 Studies have also reported differences in prevalence across demographic groups, such as an age-related decline in vigorous or contact sports,9,10,13,24 and a higher popularity of dancing/aerobics in non-Hispanic blacks and Mexican Americans compared with non-Hispanic whites.9 We identified similar top activities and demographic patterns based on attributable proportion. For example, walking ranked first overall and the attributable proportion for walking was even higher among women of all racial/ethnic groups, the elderly, and those who were insufficiently active.

It is not unexpected that our findings based on activity volume are similar to those based on the prevalence of participation. Existing reports with estimates on frequency and duration for specific activities also suggest that activities with relatively high prevalence of participation are often those in which participants engage for a substantial amount of time.7,10,11,23 This may suggest that prevalence of participation may be an acceptable proxy for determining the contribution of a specific activity to total volume of activity and for identifying which physical activities to promote.

Our findings are also generally consistent with those reported from the only study we identified that estimated the relative contribution of individual activities to the total duration of activity by intensity of activity among normal weight, overweight, and obese adults using the same data as the current analysis.7 In the study, walking accounted for about 40% of the total duration of all moderately intense physical activity, the most among all activities, and golf, weightlifting, and dance ranked among the top 5 activities for duration of moderately intense physical activity, across all levels of obesity status.7 In our study, however, golf was included in sports and weightlifting was excluded as we only looked at aerobic physical activity.

To mobilize people who are inactive to do some activity or people who are insufficiently active to do more activity, it is important to know what activities they prefer to do. Using participation as a proxy for preference, in this respect, it is interesting to note that adults who are active tend to spend a higher proportion of their time in sports activity, especially among men, while adults who are not active enough tend to focus their limited activity more on walking and dancing than their active counterparts. Although we do not have participation for adults who are inactive, findings of older adults’ preferences indicated similar findings as participation where walking/jogging was the most preferred activity, followed by outdoor maintenance (including lawn and garden) and sports.25

There are several limitations to this study. First, the current analysis used data from the 1999–2006 NHANES cycles when data on specific types of leisure-time physical activities were collected. Inferences based on the findings for contemporary physical activity patterns should be made with caution. Second, leisure-time physical activity was assessed by self-report, which may be subject to recall and social desirability biases, potentially resulting in overestimation of frequency and duration of activity.26 However, self-report continues to be the most widely used type of physical activity assessment, especially in large population-based surveys.26 One of the benefits of the self-report instrument used in this study was the ability to assess participation and duration in specific types of physical activity. In addition, validation studies of similar population-based surveys17 provide indirect support for the validity of the NHANES survey data used in the current analysis. Third, season-specific variations in physical activity may not be fully captured in the NHANES, because participants are asked about their activities in the past 30 days and it is a “fair weather” survey that avoids extreme hot/cold weather.27 For example, states with a lot of snow are not surveyed in winter and states with extreme heat are not surveyed in the summer. Thus, there may be a seasonal aspect to the findings; for example, some cold weather activities (like skiing) might be underrepresented and, therefore, underestimated. Fourth, lawn and garden activities were not queried under specific activities in all years. However, our supplemental analysis restricted to years when lawn and garden activities were included as a specific activity did not substantially change the ranking of most popular activities. Fifth, only activities done during leisure-time were included and this may have resulted in an underestimate of physical activity levels when individuals’ transportation activity and work hours are considered. Last, participants who were inactive, and maybe the most important people to reach, inherently provided no information on which activities were the most common. Future studies may want to identify which activities are most preferred in this subgroup. However, because walking had the largest attributable proportion, walking is the most common form of activity across the nation, walking is an easy way to start and maintain a physically active lifestyle, and walking can serve many purposes,28 walking may be a good activity to recommend for this subgroup.

There are several strengths to this study. NHANES has relatively high response rates (79% to 84%)15 that may limit the likelihood of bias because of low participation. The availability of nationally representative data on specific types of leisure-time aerobic activities makes it possible for the current analysis to include most activities in which US adults participate. In addition, although results may not generalize to other countries, this study provides national comparison data for observational studies in communities.

Conclusions

Identifying leisure-time popular activities in the US population is important for developing effective interventions to promote physical activity. Our findings suggest, based on the attributable proportion, walking, sports, dancing and lawn/garden activities were most popular among US adults. Attributable proportions for specific activities varied across subgroups Walking has broad appeal to the US general population and may be especially useful for physical activity promotion in population subgroups with low physical activity levels. It is important to take the differences across population subgroups into account when designing programs and implementing strategies to promote physical activity in the US.

Footnotes

Financial assistance: none.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Report 2008. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.United States Dept. of Health and Human Services. 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blackwell DL, Lucas JW, Clarke TC. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2012. Vital and health statistics. Series 10, Data from the National Health Interview Survey. 2014;(260):1–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity and Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; 1996. p. 185. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caspersen CJ, Bloemberg BP, Saris WH, Merritt RK, Kromhout D. The prevalence of selected physical activities and their relation with coronary heart disease risk factors in elderly men: the Zutphen Study, 1985. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;133(11):1078–1092. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Littman AJ, Kristal AR, White E. Effects of physical activity intensity, frequency, and activity type on 10-y weight change in middle-aged men and women. International journal of obesity. 2005;29(5):524–533. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spees CK, Scott JM, Taylor CA. Differences in amounts and types of physical activity by obesity status in US adults. American journal of health behavior. 2012;36(1):56–65. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.36.1.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control Prevention. Prevalence of leisure-time physical activity among overweight adults--United States, 1998. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2000;49(15):326–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crespo CJ, Keteyian SJ, Heath GW, Sempos CT. Leisure-time physical activity among US adults. Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(1):93–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiPietro L, Williamson DF, Caspersen CJ, Eaker E. The descriptive epidemiology of selected physical activities and body weight among adults trying to lose weight: the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey, 1989. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1993;17(2):69–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ham SA, Kruger J, Tudor-Locke C. Participation by US adults in sports, exercise, and recreational physical activities. Journal of physical activity & health. 2009;6(1):6–14. doi: 10.1123/jpah.6.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hesser JE, Kim H. Preferred types of physical activity among Rhode Island adults. Med Health R I. 1997;80(9):307–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity and Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Center for Health Statistics. [Accessed June 2014];National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Survey Methods and Analytic Guidelines. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/survey_methods.htm.

- 15.National Center for Health Statistics. [Accessed June 2013];National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. NHANES Response Rates and CPS Totals. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/response_rates_CPS.htm.

- 16.National Center for Health Statistics. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. [Accessed June 2013];Physical Activity and Physical Fitness Questionnaire. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/spq-pa.pdf.

- 17.Nelson DE, Holtzman D, Bolen J, Stanwyck CA, Mack KA. Reliability and validity of measures from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) Sozial- und Praventivmedizin. 2001;46(Suppl 1):S3–S42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Herrmann SD, et al. 2011 Compendium of Physical Activities: a second update of codes and MET values. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2011;43(8):1575–1581. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31821ece12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson CLP-RR, Ogden CL, et al. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: Analytic Guidelines, 1999–2010. National Center for Health Statistics. 2013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Belza B, Allen P, Brown DR, et al. [Accessed April 2016];Mall walking: A program resource guide. 2015 http://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/downloads/mallwalking-guide.pdf.

- 21.Senior Community Garden Initiative. [Accesssed April 2016];Atlanta Regional Commission. http://www.atlantaregional.com/aging-resources/health--wellness/community-garden-initiative.

- 22.Blanchard CM, Cokkinides V, Courneya KS, Nehl EJ, Stein K, Baker F. A comparison of physical activity of posttreatment breast cancer survivors and noncancer controls. Behavioral medicine. 2003;28(4):140–149. doi: 10.1080/08964280309596052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Humphreys BR, Ruseski JE. Participation in physical activity and government spending on parks and recreation. Contemp Econ Policy. 2007;25(4):538–552. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carlson SA, Fulton JE, Galuska DA, Kruger J, Lobelo F, Loustalot FV. Prevalence of self-reported physically active adults --- United States, 2007. MMWR: Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report. 2008;57(48):1297–1300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szanton SL, Walker RK, Roberts L, et al. Older adults’ favorite activities are resoundingly active: findings from the NHATS study. Geriatr Nurs. 2015;36(2):131–135. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sallis JF, Saelens BE. Assessment of physical activity by self-report: status, limitations, and future directions. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2000;71(2 Suppl):S1–S14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zipf G, Chiappa M, Porter K, Ostchega Y, Lewis BG, Dostal J. National Health Nutrition Examination Survey: Plan Operations, 1999–2010. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital and Health Statistics. 2013;1(56):1–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.US Department of Health and Human Services. Step It Up! The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Promote Walking and Walkable Communities. Washington, DC: U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]