Abstract

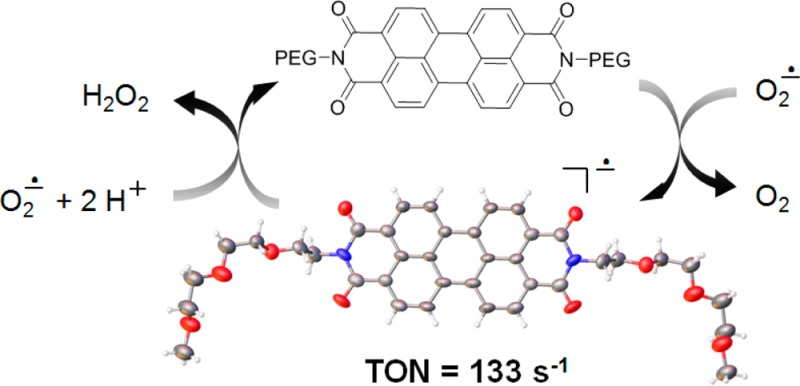

Here we show that the active portion of a graphitic nanoparticle can be mimicked by a perylene diimide (PDI) to explain the otherwise elusive biological and electrocatalytic activity of the nanoparticle construct. Development of molecular analogues that mimic the antioxidant properties of oxidized graphenes, in this case the poly(ethylene glycolated) hydrophilic carbon clusters (PEG–HCCs), will afford important insights into the highly efficient activity of PEG–HCCs and their graphitic analogues. PEGylated perylene diimides (PEGn–PDI) serve as well-defined molecular analogues of PEG–HCCs and oxidized graphenes in general, and their antioxidant and superoxide dismutase-like (SOD-like) properties were studied. PEGn–PDIs have two reversible reduction peaks, which are more positive than the oxidation peak of superoxide (O2•–). This is similar to the reduction peak of the HCCs. Thus, as with PEG–HCCs, PEGn–PDIs are also strong single-electron oxidants of O2•–. Furthermore, reduced PEGn–PDI, PEGn–PDI•–, in the presence of protons, was shown to reduce O2•– to H2O2 to complete the catalytic cycle in this SOD analogue. The kinetics of the conversion of O2•– to O2 and H2O2 by PEG8–PDI was measured using freeze-trap EPR experiments to provide a turnover number of 133 s–1; the similarity in kinetics further supports that PEG8–PDI is a true SOD mimetic. Finally, PDIs can be used as catalysts in the electrochemical oxygen reduction reaction in water, which proceeds by a two-electron process with the production of H2O2, mimicking graphene oxide nanoparticles that are otherwise difficult to study spectroscopically.

Keywords: superoxide dismutase, reactive oxygen species, radical anion, electron paramagnetic resonance, perylene diimide

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) is a metalloenzyme that controls the fluxes of the partially reduced products of molecular O2 or reactive oxygen species (ROS) during the cycle of molecular O2 in biological systems.1−3 ROS are involved in the progression of aging as well as a variety of acute and chronic diseases such as cancer and vascular diseases.4−6 Superoxide is a radical anion (O2•–) that is the primary ROS produced by direct single-electron reduction of molecular O2.7 Subsequent proton-coupled reduction of O2•– would lead to the other secondary members of ROS such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), organic peroxides (ROOH), hydroperoxyl radical (HO2•) and hydroxyl radical (HO•).8−10 In aprotic solvents, O2•– is stable and exhibits reversible outer-sphere electron-transfer (ET) behavior. However, in the presence of protons, O2•– proceeds quickly to form secondary ROS through consecutive proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) reactions. SOD possesses the combination of redox-active metal centers and ligand environments that catalytically dismutate 2 O2•– into O2 and H2O2: 2 O2•– + 2 H+ → O2 + H2O2.3

There have been many efforts to synthesize molecular organometallic complexes that can mimic the catalytic cycle of SOD.11−13 Over the past two decades, many high-valent metal complexes have been studied to gain fundamental insights into the structural, functional and mechanistic aspects of the enzymes and their counterparts.14−17 Detailed mechanistic studies have shown that ET occurs through either inner-sphere or outer-sphere mechanisms and the M–O2•– species is an important reactive intermediate formed via the inner-sphere mechanism.18 However, another class of effective inhibitors of ROS are antioxidants that are purely organic molecules.19,20 Organic molecule ET mechanisms are generally complex and in most cases they occur through a continuum of mixed inner-sphere and outer-sphere mechanisms.21,22

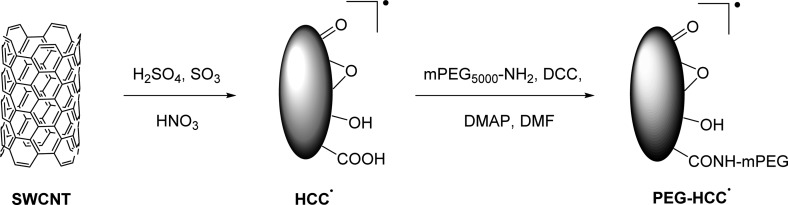

Recently, we developed metal-free carbon nanomaterials, poly(ethylene glycolated) hydrophilic carbon clusters (PEG–HCCs, Scheme 1), which show highly efficient catalytic conversion of O2•– into O2 and H2O2 (eqs 1 and 2) that rivals that of bovine Cu/Zn SOD, the most efficient native SOD enzyme.23

Scheme 1. Synthesis of PEG–HCCs from SWCNTs as the Starting Material.

Single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) are oxidatively disintegrated and split open to form graphene domains that are 3 nm × 35 nm with large amounts of oxidized functionalities that make the carbon system extremely electron deficient.24 They have been extensively characterized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), atomic force microscopy (AFM), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), dynamic light scattering, Raman spectroscopy (confirming the loss of the tubular form through complete diminution of the radial breathing modes), electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR), and further tested for in vitro and in vivo toxicity and biological activity as antioxidants.25−32 The HCCs also bear, on average, one unpaired electron per nanoparticle and the nanoparticle radical is air stable.23 As we have shown previously, HCCs can efficiently oxidize O2•– into O2, one of the two half-reactions processes (eq 1) seen in SOD, and this might also be the rate-determining step of the SOD catalytic cycle.24 This is followed by reduction of O2•– in the presence of water to form H2O2 (eq 2).

| 1 |

| 2 |

In this work, we report poly(ethylene glycolated) perylene diimide (PEGn–PDI) as an example of small molecular analogues of PEG–HCCs, and more generally well-defined highly oxidized graphene analogues. In our previous work using HCC as an electrocatalyst for the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR),24 we showed that proton transfer steps are much faster than the electron-transfer steps, and here we use the same technique to evaluate the involvement of proton transfer steps during the dismutation of O2•– using the well-defined carbon core molecule PDI in PEGn–PDI. The understanding of graphene-based catalysts can benefit from the study of molecular analogues, and we propose that PDI serves as a simplified model of oxidized graphenes.

Results and Discussion

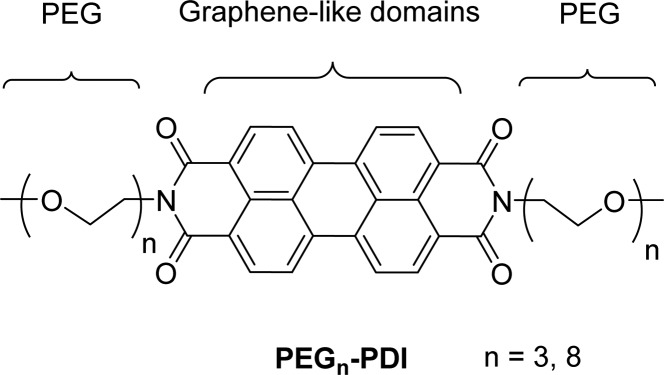

PEGn-PDI and Its Reactions with Superoxide

PDI was identified as an electron deficient molecular analogue of HCCs, and was further linked with two polyethylene glycol (PEG) substituents for increased solubility in solvents such as water, DMF and DMSO. Two different PEG units were used in this study, with the shorter being three and the longer being eight ethylene glycol units, PEG3–PDI and PEG8–PDI, respectively (Figure 1). PEG3–PDI is less soluble in aqueous and organic solvents; however, it is more suitable for crystallization and characterization in the solid state, while PEG8–PDI has better solubility therefore better suitability for characterization in the solution state. Note that with PEG–HCCs, 5000 MW PEG was used in order to make the nanoparticles soluble in phosphate buffered saline.33 Details of the synthetic procedure for preparation of PEGn–PDIs and structural characterization by NMR and X-ray crystallography can be found in the Supporting Information.

Figure 1.

Structural formula of PEGn–PDI.

The electrochemical behavior of PDI is well-known and the cyclic voltammetry (CV) shows two reversible redox peaks in both neutral organic and aqueous media.34 In DMSO, PEG8–PDI gave two redox values (E1 and E2) at −0.88 V and −1.12 V versus Fc/Fc+ (Figure S1). Both redox potentials of PEG8–PDI are more positive than the redox peak of O2•– (E = −1.25 V versus Fc/Fc+ in DMSO)24 by 0.37 and 0.13 V, respectively. This indicates that single-electron oxidation of O2•– to O2 by both PEG8–PDI and PEG8–PDI•– are thermodynamically favorable and exothermic processes, which is also the first half-reaction of the SOD catalytic cycle. The HCC carbon core of the PEG–HCC is the electron deficient redox center of the carbon nanoparticles, and it has a broad reduction potential with the initial onset being more positive by 0.60 V than the reduction peak of O2•– in aqueous media.24 This indicates that PEG8–PDI has comparable thermodynamic ability to oxidize O2•– to the oxidized graphene analogue PEG–HCC.

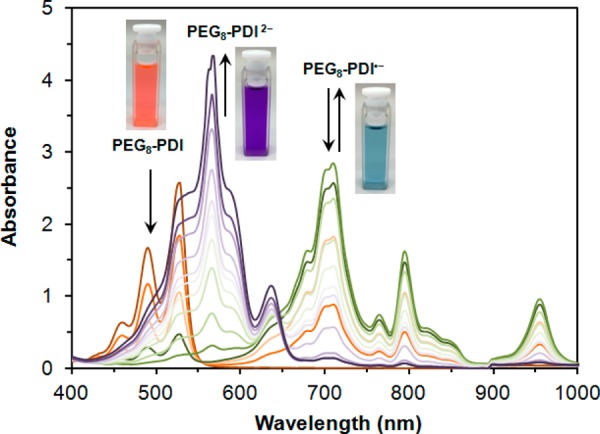

To further assess the reactivity of PEG8–PDI with O2•–, we monitored the optical spectral changes upon the addition of O2•– to the solution of PEG8–PDI under inert atmosphere. Figure 2 (in red) shows the optical spectrum of 0.04 mM PEG8–PDI (Figure S2) in DMSO with the major band at λ = 525 nm (ε = 6.38 × 104 M–1 cm–1), typical for PDI derivatives in various solvents.35 Upon addition of KO2 in small increments (0.0114 mM), the solution of PEG8–PDI shows a gradual change in color from red to greenish-blue, which corresponds to the formation of an equimolar amount of the one-electron reduced PEG8–PDI•–, with the major band at λ = 710 nm (ε = 7.20 × 104 M–1 cm–1). Optical spectra of PDI radical anions are known and well-documented.34,36 The gradual addition of another equivalent of KO2 results in the further change in absorbance of PEG8–PDI•– to a purple color, with the major band at λ = 568 nm (ε = 1.08 × 105 M–1 cm–1), which corresponds to the two-electron reduced PEG8–PDI2– (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Spectral changes upon treatment of a 0.04 mM DMSO solution of PEG8–PDI after the addition of a DMSO solution of KO2 in small increments (0.0114 mM). Red: PEG8–PDI, greenish-blue: PEG8–PDI•–, purple: PEG8–PDI2–.

Interestingly, addition of extra amounts of KO2 to the resultant dark-purple colored solution of PEG8–PDI2– does not result in any further changes. This is the evidence that PEG8–PDI2– is persistent in the presence of KO2 and does not exhibit additional reduction steps. The two isosbestic points at λ = 559 nm and then λ = 648 nm indicate the two successive single-step chemical processes. Therefore, these optical observations provide evidence that oxidation of O2•– to O2 in DMSO can be achieved by both PEG8–PDI and PEG8–PDI•– through the consecutive single electron-transfer mechanisms, according to eq 3.

| 3a |

| 3b |

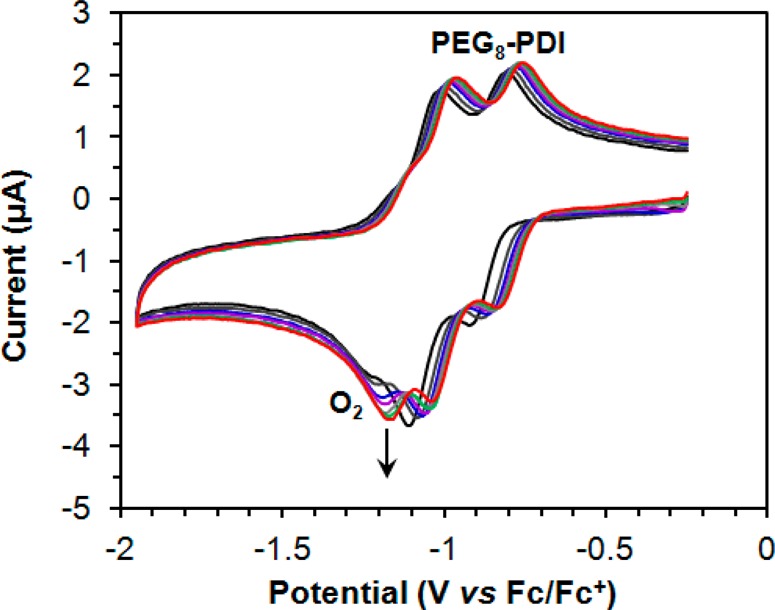

The other evidence for eq 3 is provided by electrochemical measurements. CV of PEG8–PDI exhibits two successive redox peaks (Figure 3), which corresponds to two consecutive PEG8–PDI/PEG8–PDI•– and PEG8–PDI•–/PEG8–PDI2– couples.

Figure 3.

CVs of 10 mM of PEG8–PDI in DMSO under N2 after adding incremental amounts of KO2 (20 μL of KO2 in DMSO, 0.0114 mM stock) containing of 0.1 M [(n-Bu)4N]ClO4 as a supporting electrolyte at 298 K with a glassy carbon working electrode and platinum wire as quasi-reference electrode. Scan rate: 50 mV/s. The arrow indicates the newly formed redox peak of the molecular O2. Color code: KO2 concentration increased from black to red.

In addition to the color changes of the solution, subsequent addition of incremental amounts of KO2 to the solution of PEG8–PDI gives rise to the new CV curve centered at E = −1.23 V versus Fc/Fc+, as shown in Figure 3. The new peak at E = −1.23 V corresponds to the CV of dissolved molecular O2, as supported by the disappearance of the peak upon bubbling the solution with N2 for 5 min. Conversely, the peak of dissolved KO2 in electrolyte without PEG8–PDI present is persistent for 6 h while bubbling with N2 (Figure S3).24 These electrochemical tests show that both PEG8–PDI and PEG8–PDI•– can oxidize O2•– to O2 through a single electron-transfer reaction (eq 3) and the product, molecular O2, can be observed electrochemically. Furthermore, the reversible two consecutive 1e– redox peaks of PEG8–PDI upon addition of KO2 nicely reveal the underlying mechanism of outer-sphere ET from O2•– to PEG8–PDI and PEG8–PDI•–, where O2•– is a reductant. Also, the symmetric size of the current on the reductive and oxidative transition of PEG8–PDI in the presence of O2•– confirms the simple interpretation of the outer-sphere ET mechanism.37

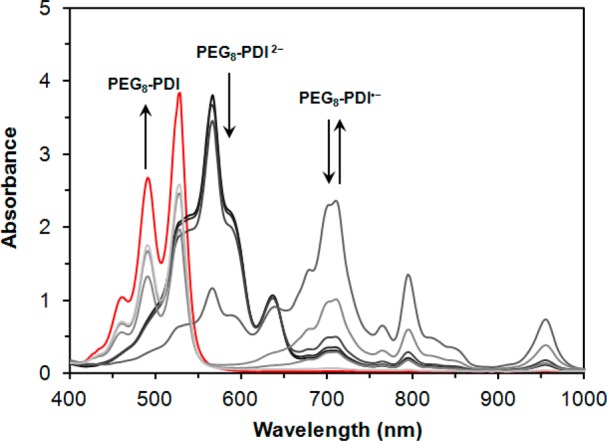

To examine the SOD-like activity of PEG8–PDI, and to investigate whether the second-half reaction of SOD proceeds analogous to eq 2, we performed additional experiments to determine the reactivity of PEG8–PDI•– and PEG8–PDI2– with O2•– in the presence of protons (HClO4) in the aprotic environment of DMSO. Both PEG8–PDI•– and PEG8–PDI2– served as reductants of O2•– to H2O2 in the presence of 2 equiv of H+. But upon incremental addition of substoichiometric amounts of HClO4 in DMSO, the purple solution of PEG8–PDI2– in the presence of KO2 gradually changed color to red (Figure 4). Through analysis of UV/vis spectra taken immediately after the addition of HClO4, the recovery of the initial PEG8–PDI was achieved in 70% yield (Figure 4). The loss of the remaining 30% suggests that the PEG8–PDI, PEG8–PDI•– or PEG8–PDI2– could be thermodynamically unstable in the presence of H2O2, which is the product of the second-half of the dismutase according to eqs 2, 4 and 5.

Figure 4.

Absorption spectra of PEG8–PDI2– in DMSO (black curve) upon treatment with KO2 and HClO4 indicating the formation of H2O2 and regeneration of original neutral PEG8–PDI (red curve) proceeding via the PEG8–PDI•– (gray curve).

A separate experiment where PEG8–PDI is treated with H2O2 and HClO4 does not exhibit any changes in the optical spectra (Figure S4), suggesting the persistent nature of PEG8–PDI under these conditions, thus precluding reaction of PEG8–PDI with H2O2 as a reason for the depressed yield. The fact that PEG8–PDI2– rapidly reacts according to eq 4 and immediately reforms stoichiometric amounts of PEG8–PDI•– as the product (Figure 4), also excludes PEG8–PDI2– from being the source for the decreased yields. However, PEG8–PDI•– reacts irreversibly with H2O2 and gradually forms a product with an optical spectrum uncharacteristic of PEG8–PDI (Figure S5). This explains the loss of the 30% of the original PEG8–PDI during the second half of the SOD-mimetic step, where PEG8–PDI•– reacts with produced H2O2 via efficient PCET reaction mechanism as shown in eq 6.38,39

| 4 |

| 5 |

| 6 |

Thus, these optical data provide evidence that PEG8–PDI mimics the catalytic cycle of SOD.

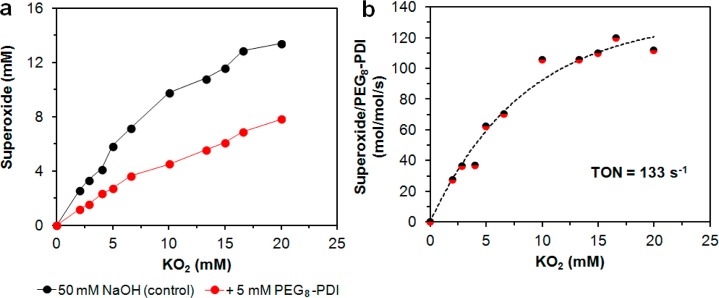

The kinetics of the reaction between O2•– and PEG8–PDI was measured using KO2 and a direct freeze-trap EPR steady-state kinetics assay rather than the less efficient spin-trapping EPR which also loses kinetic information. 18-Crown-6 was used to increase the solubility of KO2 in DMSO. In this case excess O2•– was used to estimate the intrinsic turnover number for O2•– conversion to O2 by PEG8–PDI. In order to slow down the self-dismutation of superoxide in aqueous media to achieve reasonable initial concentrations of O2•– in solution, we carried out the kinetic experiments at pH 13 in 50 mM NaOH. PEG8–PDI is stable at pH 13 as there is no change of optical spectral shape observed by 30 min preincubation. A control EPR sample was prepared using this preincubated PEG8–PDI to react with 20 mM KO2 and freeze trapped. The amount of radical determined is basically the same as that of fresh PEG8–PDI.

Figure 5a shows that the total spin concentration of O2•– gradually increased with the amount of added KO2. As expected, the concentration of O2•– decreased in the presence of PEG8–PDI. Therefore, the consumption of O2•– by PEG8–PDI can be estimated from the difference between the control, which does not contain any PEG8–PDI, and subsequently recalculated as turnover numbers (defined as number of moles of consumed O2•– per moles of PEG8–PDI per second) with an average reaction time of 10 s (Figure 5b). At the saturation behavior of [O2•–] the highest O2•– turnover rate was estimated as 133 s–1, which is almost 1000× lower than that of PEG–HCCs.23 This is not surprising, as it is possible that the redox potential of the two half reactions for PEG8–PDI are not as optimal as PEG–HCCs24 or the electron transfer kinetic barrier is higher than that of the PEG–HCCs. Overall, the kinetics experiments indicate that PEG8–PDI behaves similarly to SOD and PEG–HCCs as a “hit-and-run” type reaction, where O2•– substrate only momentarily stays in the active center, so the rate-limiting step is not the binding but the oxidation/reduction of the O2•–.

Figure 5.

KO2 experiments in 50 mM NaOH. (a) O2•– total spin concentration based on double integration of obtained EPR spectra. For details, see Experimental Methods. (b) The turnover number (TON) was calculated by subtracting the amount of remaining O2•– from the amount of O2•– in the control, dividing by the amount of PEG8–PDI and then by 10 s for the reaction time (the average time required for manually freeze-trapping each EPR sample). Two similar experiments performed using 1.5 μM PEG8–PDI concentration yielded similar kinetic pattern.

Isolation and Characterization of PEGn–PDI Radical Anions

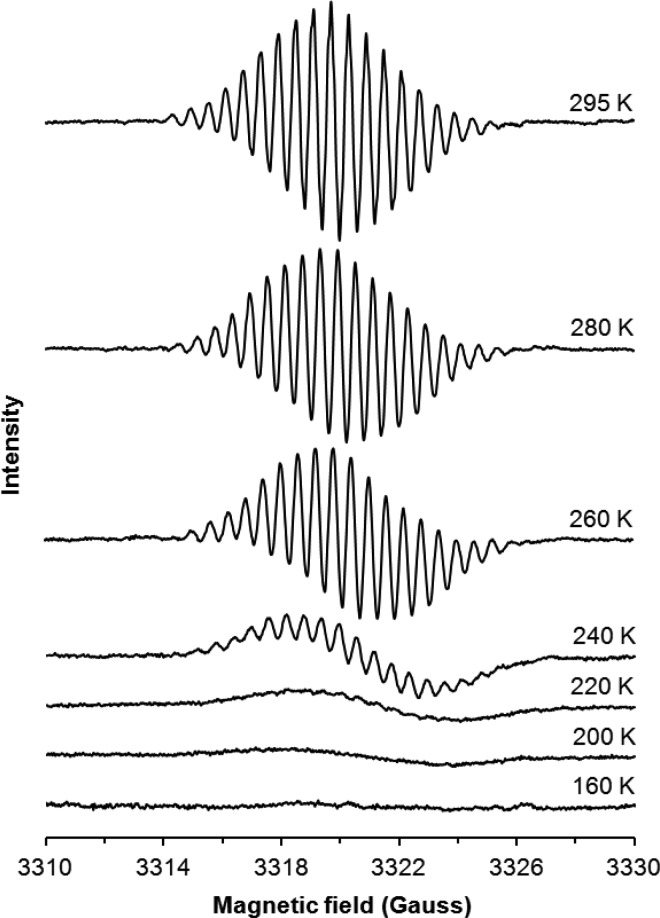

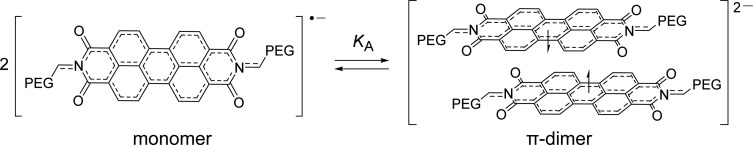

PEG8–PDI•– as a reaction intermediate was additionally characterized by EPR spectroscopy. As with the optical measurements, PEG8–PDI•– was generated using stoichiometric (1:1) amounts of KO2 as a reductant under inert atmosphere and it shows an EPR spectrum (g = 2.0019) with apparent 18 line hyperfine splitting caused by nitrogens and protons (Figure 6). Simulation of the EPR spectrum reveals the delocalization of unpaired spin over the entire π-conjugated unit of PDI with the following hyperfine splitting: ring protons (n = 8): 1.2 G; side chain protons (n = 4): 0.6 G; nitrogens (n = 2): 0.04 G, line width 0.23 G (Figures S6). The shape of the EPR spectra does not change substantially with temperature, except slight broadening of the lines when the temperature is lowered from 295 to 260 K. This is due to increased viscosity of the solvent which could lead to changes in the electron spin distribution and variation in coupling constants (Figure S7). However, further decrease in temperature of the sample results in decrease of intensity and eventually loss of the EPR signal at 160 K as can be seen from Figure 6. π-Dimerization of the stable radical ions to form weakly bonded dimeric species has been frequently considered over the past decade.40−44

Figure 6.

Variable-temperature EPR spectra of PEG8–PDI•– obtained by reduction of PEG8–PDI with equimolar amounts of KO2 in DMF.

Similarly, for PEG8–PDI•– the signal intensity decreases upon cooling the sample with the gradual replacement of the paramagnetic monomer by the diamagnetic π-dimer (Scheme 2). Intensity of signal (IEPR) and concentrations were determined by double integration of the spectra. According to the Curie law, IEPR = a × [M]/T, where a is a proportionality factor, IEPR is proportional to the concentration of the radical (PEG8–PDI•–) in the sample. Assuming that at room temperature the equilibrium (Scheme 2) shifts to the left and only monomeric radical anions exist in solution, and using the proportionality ratio IEPR/IEPR298 = [M]/[M]298 = α where α is a mole fraction of the monomeric radical anion at a particular temperature, the equilibrium concentration of the monomeric radical anion can be estimated at each temperature. By using KA = (1 – α)/2[M]298α2 with an estimated α, it permits calculation of the equilibrium constants for π-dimerization at each temperature. Thermodynamic parameters for π-dimerization of the monomeric radical anions were calculated by the least-squares procedure from the linear relationship of ln(KA) and 1/T, resulting in the analysis pictured in Figures S8.

Scheme 2. Reversible π-Dimerization of PEGn–PDI•–

The thermodynamic parameters ΔHD and ΔSD can be estimated as −7.7 kcal/mol and −17.1 e.u. respectively, which are close to the values of thermodymanic parameters for π-dimerization in most of the extended π-radicals.41 The strong attraction of two unpaired electrons prevails over electrostatic repulsion of two oppositely charged anions.

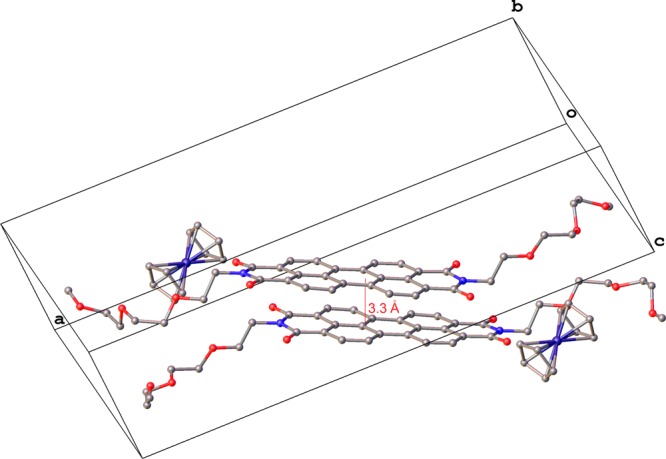

Interestingly, a single crystal of the PEG3–PDI•– was obtained using cobaltocene as a reducing agent. A green solution of the [PEG3–PDI•– CoCp+] in DMF was layered carefully with dry ethyl ether and left in a freezer at −10 °C for 1 week and small dark-green-colored crystalline needles were collected and subjected to X-ray crystallographic analysis. Crystallographic analysis resulted in infinite π-stacked PDI units of PEG3–PDI•– along the b-axis with close π–π interactions of 3.36(2) Å as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

View of the unit cell of the crystal structure of [PEG3–PDI•– CoCp+]. Solvents and hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity. Color code: C, gray; N, blue; O, red; Co, purple.

ORR Activity of PDIs

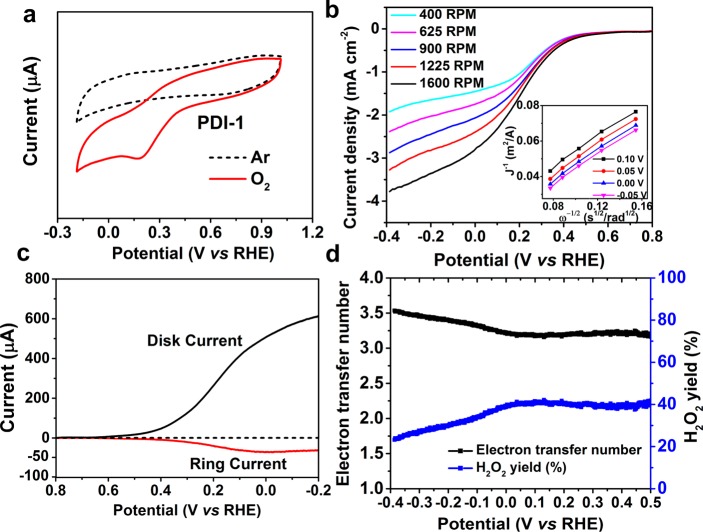

Knowing the properties of PDI within PEGn–PDIs to be efficient electron shuttle agents during the catalytic turnover of O2•–, and also that PDIs have redox potentials close to that of molecular O2, we investigated the electocatalytic properties of PDIs for their oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) activity. Despite the fact that development of molecular catalysts for electrochemical reduction of O2 has been an active research field, many of the studied catalysts are high-valent organometallic complexes while examples of pure organic molecules are scarce.45−47 A water-insoluble derivative of PDI, bis-2-ethylhexyl PDI (PDI-1, Figure S9) was immobilized on a glassy carbon (GC) working electrode which served as an O2-electrode, and it was tested in O2-saturated 0.1 M NaHPO4/NaH2PO4 buffer solution at pH 7. The comparison spectra testing under both Ar and O2 reveal that under Ar there is a very small reduction peak (Figure 8a). In contrast, PDI-1 under O2-saturated conditions results in a prominent cathodic ORR peak with an onset potential of ∼0.40 V vs RHE (Figure 8a). Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) plots were obtained by using a rotating disc electrode (RDE) with varying rotation rates to show the ORR electrocatalytic currents of PDI-1 (Figure 8b). Using the Koutecky–Levich (K–L) equation, the kinetic current density (Jk) was obtained and the electron-transfer number (n, number of electrons exchanged per O2 molecule for the ORR) was estimated as shown in inset of Figure 8b.48 The n value was determined to be 1.9 at a potential range from −0.20 to 0.20 V. This demonstrates that the complete two-electron transfer reduction process of oxygen to H2O2 proceeds according to eq 7.

| 7 |

The ORR activity of PDI-1 is also evident from the comparison in electrocatalytic reduction currents of the GC substrate with the PDI-1 immobilized electrode (Figure S10). Higher ORR currents and larger differences in the onset potential for the PDI-1-covered electrode than for the naked GC electrode reveal that interference of the GC substrate in ORR performance is negligible, in spite of the fact that O2 can be reduced onto a GC electrode.49

Figure 8.

(a) CVs of PDI-1 under 1 atm O2 or Ar. All scans were collected at 100 mV s–1 using a GC working electrode with an area of 0.196 cm2. (b) LSV curves of RDEVs of PDI-1 in O2-saturated 0.1 M NaHPO4/NaH2PO4 buffer solution at pH 7 with different rotating speeds ranging from 400 to 1600 rpm. Inset: Koutecky–Levich plots of PDI-1 showing that n = 1.9. (c) RRDEV of PDI-1 in 0.1 M NaHPO4/NaH2PO4 buffer solution at pH 7 with a rotation speed 1600 rpm. The disk was scanned from 0.8 to −0.2 V while the ring electrode was held at 1.4 V. (d) The number of electrons transferred and the H2O2 yield of PDI-1during ORR as calculated by ring currents.

These results show that there is a two-electron ORR activity of PDIs in aqueous media, as opposed to the single-electron transfer process in organic solvents. However, the stability of PDI-1 shows a small decline under ORR conditions (Figure S11), likely due to the production of aggressive radicals and H2O2 during ORR, which is likely to passivate the electrode surface over extended cycling, similar to the H2O2-mediated decomposition of PEG8–PDI•– discussed above.

The accurate determination of n, using the classic Koutecky–Levich analysis shown above, depends on many factors, including determination of the active surface area. Hence, we performed additional electrochemical tests to support the ORR activity of PDI-1. The yield of H2O2 and the potential range of ORR operation were further measured by rotating disk electrode voltammetry (RDEV) and rotating ring-disk electrode voltammetry (RRDEV) as shown in Figures 8c,d. Significant increase in cathodic disk current was observed starting at 0.4 V, while the disk potential was scanned from 0.8 to −0.2 V at a constant ring electrode potential of 1.4 V. This is consistent with the voltammograms in Figures 8a,b. Symmetric increase in ring current as in that of the disk current (Figure 8c) indicates catalytic formation of H2O2 generated at the disk.50 Using the differences in the values between disk and ring currents, the value for n and the yield of H2O2 were estimated to be 3.0 and 40%, respectively (see Experimental Methods for the details of the calculations). The value for n and the yield of H2O2 during the electrocatalytic ORR by PDI-1 indicates that there is nearly equal contribution of 2-electron and 4-electron reductions of O2 to H2O2 and H2O, respectively.

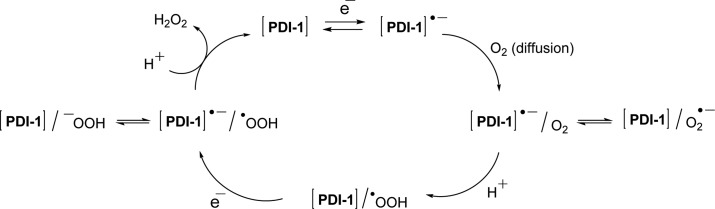

On the basis of the experimental data shown above, the general PDI-1-catalyzed two-electron-transfer oxygen reduction reaction can be described as an electrochemical-chemical-electrochemical-chemical (ECEC) type mechanism shown in Scheme 3.51 The initial electron transfer step generates [PDI-1]•–, which complexes with diffused O2 to form transient single-electron reduced complex [PDI-1]/O2•–. That is readily protonated to generate hydroperoxyl radical intermediate, [PDI-1]/•OOH. •OOH is a stronger oxidant, therefore formation of [PDI-1]/•OOH is followed by the faster second ET-step to form [PDI-1]/–OOH, where the second proton transfer step leads to H2O2 as a final product with reformation of [PDI-1].

Scheme 3. Oxygen Reduction Reaction Mechanism by PDI-1 to form H2O2.

As in most electrochemical reactions, according to the mechanistic pathway shown in Scheme 3 and the formation of H2O2 as a product during the ORR process, proton transfer steps from reaction intermediate [PDI-1]•–/O2 to [PDI-1]•–/•OOH are much faster than the heterogeneous electron transfer steps.51 Furthermore, the two single-electron transfer steps are the rate-determining steps of the ORR process. Finally, in this work we were able to show that under the electrochemical conditions, PDIs can serve as efficient electron shuttles to reduce O2 to O2•– and H2O2.

Conclusion

In summary, preparation and characterization of small well-defined conjugated molecular analogues, PEG–PDIs, as a model to elucidate the mechanisms operative in the SOD-mimetic activity of PEG–HCCs, was accomplished. Water-soluble perylene diimide derivatives serve as molecular analogues of PEG–HCCs that mimic the full catalytic cycle of SOD. PEGn-PDI was able to oxidize O2•–, and the PEGn-PDI•– intermediate of the catalytic cycle is thoroughly characterized and shown to react with O2•– in the presence of protons to form H2O2. Having the redox potential of PEGn-PDIs located between the two half reactions, O2•– → O2 + e– and O2•– + 2 H+ + 2 e– → H2O2 (−0.16 and +0.94 V, respectively, relative to NHE in water), makes them good molecular SOD-mimetics of PEG–HCCs. The freeze quench EPR study substantiated its multiple turnover of O2•– in aqueous environment. We show that study of graphene-based catalysts can benefit from the study precise molecular analogues,52,53 and PDI serves as a minimal model of HCCs and more generally oxidized graphenes. Furthermore, on the basis of the results from the RDEV and RRDEV, PDI was shown to be a metal-free molecular electrocatalyst for the O2 reduction reaction with H2O2 being produced in 40% yield. Thus, the results indicate that similar to carbon nanomaterials, PDI is an efficient electron shuttle for reactions with O2 as well as ROS. These results have important implications in the area of graphene-based materials used in electrocatalytic processes and their potential application in nanoantioxidants.

Experimental Methods

Materials and Methods

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used without further purification unless otherwise stated. Optical spectra were acquired on a Shimadzu 50 Scan UV/vis spectrometer (200–1100 nm) and Cary5000 UV–vis–NIR spectrophotometer (200–3000 nm), using capped quartz cuvettes. NMR data were recorded on Bruker 400–600 MHz spectrometers.

Single-Crystal X-ray Diffraction Analysis

Crystal data, details of data collection and structure refinement parameters for the [PEG3–PDI•– CoCp+] are presented in Table S1 and Figure S12. Diffraction data were collected on a Rigaku SCX-Mini diffractometer (Mercury2 CCD) using graphite-monochromated Mo Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å). Integration was performed with CrystalClear-SM Expert 2.0, and the data were corrected for absorption using empirical methods. The structures were solved by direct methods and refined by the full-matrix least-squares technique against F2 with the anisotropic temperature parameters for all non-hydrogen atoms. All H atoms were geometrically placed and refined in a rigid model approximation. Data reduction and structure refinement calculations were performed using the SHELXTL54 program package. The description of the disorder refinement of PEG4 groups in the PEG3–PDI•– radical anion is presented in the Supporting Information.

Electrochemistry

The CVs were obtained with a CHI1202 ElectroChemical Analyzer (CHIinstruments) for 10 mL electrolyte solutions (0.1 M [(n-Bu)4N]ClO4 solution in DMSO or PBS buffer, pH 7.4) using a 3-electrode cell. A GC electrode served as working electrode, platinum wires served as a counter electrode and Ag/AgCl as the reference electrode. A platinum wire was used as the pseudoreference electrode in DMSO and ferrocene (Fc) was used as internal potential standard and all potentials are referred to the Fc/Fc+ couple. CVs were recorded at a scan rate of 100 mV s–1.

RDE and RRDE experiments were conducted in an electrochemical cell (AUTO LAB PGSTST 302) using a Pine Instrument rotator (model: AFMSRCE) connected to a CH Instruments electrochemical analyzer (model 600D), with an Ag/AgCl reference electrode and a Pt wire counter electrode. A PDI-1 solution ink was prepared by dispersing 4 mg of the PDI-1 into 1 mL of 4:1 DCM/EtOH solvent, and 8 μL of the catalyst solution ink was loaded onto a GC electrode (5 mm in diameter). A constant bubbling by a stream of O2 in the cell solution was maintained throughout the measurement to ensure continuous O2 saturation. Measurements were carried out at pH 7 (0.1 M K2HPO4/KH2PO4 buffer). For RRDE experiments, the electrode rotation speed was 1600 rpm (scan rate, 0.05 V/s; platinum data collected from anodic sweeps), while the ring electrode potential was held at 1.1 V vs a reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE).

The O2 reduction current increases with increasing rotation rates following the K–L eq 8:

| 8 |

where JK is the potential dependent kinetic current and JL is the Levich current. JL is expressed as 0.62nF[O2](DO2)2/3ω1/2ν –1/6, where n is the number of electrons transferred to the substrate, F is the Faraday constant, [O2] is the concentration of O2 in an air-saturated buffer (0.22 mM in case of pH 7) at 25 °C, DO2 is the diffusion coefficient of O2 (1.8 × 10–5 cm2 s–1 at pH 7) at 25 °C, ω is the angular velocity of the disc and ν is the kinematic viscosity of the solution (0.009 cm2 s–1) at 25 °C. Eq 8 can be restated as eq 9; solving for JL gives eq 10:

| 9 |

| 10 |

RRDE measurements were carried out to determine the H2O2 yield (%) and n, which were calculated by eqs 11 and 12:

| 11 |

| 12 |

where id and ir are the disk and ring currents, respectively. N is the ring current collection efficiency, which was determined to be 25% by the reduction of 10 mM K3[Fe(CN)6] in 0.1 M KNO3.

Detection of Radicals by EPR Spectroscopy

The EPR spectra of PEG–PDI•– (0.05 mg/mL in DMSO) in a sealed capillary tube at ambient temperature were recorded using the following parameters: center field 3320 G, sweep width 50 G, microwave frequency 9.3 GHz, microwave power 1 mW, modulation frequency 100 kHz, and modulation amplitude 1.0G. The same sample was remeasured after adding a small amount of KO2 (1 mg in powder form).

Steady-State Consumption of Superoxide

PEG8–PDI (5 μM) in 50 mM NaOH were mixed in ratio 1:5 with increasing amounts of KO2 (dissolved in DMSO/18-crown-6) for 10 s and then frozen in ethanol/dry Ice (−72 °C) to stop the reaction. The samples were then transfer to LN2 to preserve the remaining O2•–. EPR spectra were then recorded. To account for background dismutation of O2•–, a sample lacking PEG8–PDI was measured and its EPR spectra subtracted from sample spectra to obtain the amount of KO2 decay catalyzed by the PEG8–PDI.

Acknowledgments

We thank the NIH (R01-NS094535) and the Dunn Foundation for financial support.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsnano.6b08211.

Additional graphs and data, single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis details of [PEG3–PDI•– CoCp+] (PDF)

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): Rice University owns intellectual property on the use of small molecule graphene analogs for use as antioxidants in medicine. The intellectual property has been licensed to Acelerox LLC. J. M. T. and T. A. K. are stockholders in Acelerox, though not an officer or director. Conflicts are managed through disclosures to the Rice University Office of Sponsored Programs and Research Compliance (SPARC) and the Baylor College of Medicine.

Supplementary Material

References

- Miller A. F. Superoxide Dismutases: Active Sites that Save, but a Protein that Kills. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2004, 8, 162–168. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridovich I. Superoxide Radical and Superoxide Dismutases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1995, 64, 97–112. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.64.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng Y.; Abreu I. A.; Cabelli D. E.; Maroney M. J.; Miller A.-F.; Teixeira M.; Valentine J. S. Superoxide Dismutases and Superoxide Reductases. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 3854–3918. 10.1021/cr4005296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valko M.; Leibfritz D.; Moncol J.; Cronin M. T. D.; Mazur M.; Telser J. Free Radicals and Antioxidants in Normal Physiological Functions and Human Disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2007, 39, 44–84. 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnham K. J.; Masters C. L.; Bush A. I. Neurodegenerative Diseases and Oxidative Stress. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2004, 3, 205–214. 10.1038/nrd1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel E. L. G.; Duong M. T.; Bitner B. R.; Kent T. A.; Tour J. M. Hydrophilic Carbon Clusters as Therapeutic, High Capacity Antioxidants. Trends Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 501–505. 10.1016/j.tibtech.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayyan M.; Hashim M. A.; Al-Nashef I. M. Superoxide Ion: Generation and Chemical Implications. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 3029–3085. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B. Reactive Oxygen Species in Living Systems: Source, Biochemistry, and Role in Human Disease. Am. J. Med. 1991, 91, 14S–22S. 10.1016/0002-9343(91)90279-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhyay U.; Das D.; Banerjee R. K. Reactive Oxygen Species: Oxidative Damage and Pathogenesis. Curr. Sci. India 1999, 77, 658–666. [Google Scholar]

- Valentine J. S.; Wertz D. L.; Lyons T. J.; Liou L. L.; Goto J. J.; Gralla E. B. The Dark Side of Dioxygen Biochemistry. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 1998, 2, 253–262. 10.1016/S1367-5931(98)80067-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley D. P. Functional Mimics of Superoxide Dismutase Enzymes as Therapeutic Agents. Chem. Rev. 1999, 99, 2573–2588. 10.1021/cr980432g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalvemini D.; Wang Z.-Q.; Zweier J. L.; Samouilov A.; Macarthur H.; Misko T. P.; Currie M. G.; Cuzzocrea S.; Sikorski J. A.; Riley D. P. A Nonpeptidyl Mimic of Superoxide Dismutase with Therapeutic Activity in Rats. Science 1999, 286, 304–306. 10.1126/science.286.5438.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner K. M.; Fridovich I. Mimics of Superoxide Dismutase. Antiox. Health Dis. 1997, 4, 375–407. [Google Scholar]

- Cabelli D. E.; Riley D.; Rodriguez J. A.; Valentine J. S.; Zhu H. In Biomimetic Oxidations Catalyzed by Transition Metal Complexes; Meunier B., Ed.; Imperial College Press: London, UK, 2000; p 461. [Google Scholar]

- Miller A.-F. In Comprehensive Coordination Chemistry II: From Biology to Nanotechnology; McCleverty J. A., Meyer T. J., Eds.; Elsevier Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 2004; Vol. 8, p 479. [Google Scholar]

- Smirnov V. V.; Roth J. P. Evidence for Cu–O2 Intermediates in Superoxide Oxidations by Biomimetic Copper(II) Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 3683–3695. 10.1021/ja056741n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee S. K.; Maji R. C.; Barman S. K.; Olmstead M. M.; Patra A. K. Hexacoordinate Nickel(II)/(III) Complexes that Mimic the Catalytic Cycle of Nickel Superoxide Dismutase. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 10184–10189. 10.1002/anie.201404133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth J. P. Oxygen Isotope Effects as Probes of Electron Transfer Mechanisms and Structures of Activated O2. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009, 42, 399–408. 10.1021/ar800169z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z. Q. Chemical Methods to Evaluate Antioxidant Ability. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 5675–5691. 10.1021/cr900302x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingold K. U.; Pratt D. A. Advances in Radical-Trapping Antioxidant Chemistry in the 21st Century: A Kinetics and Mechanisms Perspective. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 9022–9046. 10.1021/cr500226n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosokha S. V.; Kochi J. K. Continuum of Outer- and Inner-Sphere Mechanisms for Organic Electron Transfer. Steric Modulation of the Precursor Complex in Paramagnetic (Ion-Radical) Self-Exchanges. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 3683–3697. 10.1021/ja069149m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosokha S. V.; Kochi J. K. Fresh Look at Electron-Transfer Mechanisms via the Donor/Acceptor Bindings in the Critical Encounter Complex. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 641–653. 10.1021/ar700256a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel E. L. G.; Marcano D. C.; Berka V.; Bitner B. R.; Wu G.; Pottera A.; Fabian R. H.; Pautler R. G.; Kent T. A.; Tsai A.-L.; Tour J. M. Highly Efficient Conversion of Superoxide to Oxygen Using Hydrophilic Carbon Clusters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015, 112, 2343–2348. 10.1073/pnas.1417047112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalilov A. S.; Zhang C.; Samuel E. L. G.; Sikkema W.; Wu G.; Berka V.; Kent T. A.; Tsai A.-L.; Tour J. M. Mechanistic Study for the Conversion of Superoxide to Oxygen and Hydrogen Peroxide in Carbon Nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 15086–15092. 10.1021/acsami.6b03502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z.; Kobashi K.; Rauwald U.; Booker R.; Fan H.; Hwang W.-F.; Tour J. M. Soluble Ultra-Short Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 10568–10571. 10.1021/ja063283p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson J. J.; Hudson J. L.; Leonard A. D.; Price B. K.; Tour J. M. Repetitive Functionalization of Water-Soluble Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Addition of Acid-Sensitive Addends. Chem. Mater. 2007, 19, 3491–3498. 10.1021/cm070076v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lucente-Schultz R. M.; Moore V. C.; Leonard A. D.; Price B. K.; Kosynkin D. V.; Lu M.; Partha R.; Conyers J. L.; Tour J. M. Antioxidant Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 3934–3941. 10.1021/ja805721p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price B. K.; Lomeda J. R.; Tour J. M. Aggressively Oxidized Ultra-Short Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Having Oxidized Sidewalls. Chem. Mater. 2009, 21, 3917–3923. 10.1021/cm9021613. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin J. M.; Pham T. T.; Sano D.; Mohamedali K. A.; Marcano D. C.; Myers J. N.; Tour J. M. Noncovalent Functionalization of Carbon Nanovectors with an Antibody Enables Targeted Drug Delivery. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 6643–6650. 10.1021/nn2021293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sano D.; Berlin J. M.; Pham T. T.; Marcano D. C.; Valdecanas D. R.; Zhou G.; Milas L.; Myers J. N.; Tour J. M. Noncovalent Assembly of Targeted Carbon Nanovectors Enables Synergistic Drug and Radiation Cancer Therapy in Vivo. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 2497–2505. 10.1021/nn204885f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe M. A.; Marcano D. C.; Berlin J. M.; Widmayer M. A.; Baskin D. S.; Tour J. M. Antibody-Targeted Nanovectors for the Treatment of Brain Cancers. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 3114–3120. 10.1021/nn2048679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitner B. R.; Marcano D. C.; Berlin J. M.; Fabian R. H.; Cherian L.; Culver J. C.; Dickinson M. E.; Robertson C. S.; Pautler R. G.; Kent T. A.; Tour J. M. Antioxidant Carbon Particles Improve Cerebrovascular Dysfunction Following Traumatic Brain Injury. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 8007–8014. 10.1021/nn302615f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin J. M.; Leonard A. D.; Pham T. T.; Sano D.; Marcano D. C.; Yan S.; Fiorentino S.; Milas Z. L.; Kosynkin D. V.; Price B. K.; Lucente-Schultz R. M.; Wen X. X.; Raso M. G.; Craig S. L.; Tran H. T.; Myers J. N.; Tour J. M. Effective Drug Delivery, In Vitro and In Vivo, by Carbon-Based Nanovectors Noncovalently Loaded with Unmodified Paclitaxel. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 4621–4636. 10.1021/nn100975c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirman E.; Ustinov A.; Ben-Shitrit N.; Weissman H.; Iron M. A.; Cohen R.; Pybchinski B. Stable Aromatic Dianion in Water. J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112, 8855–8858. 10.1021/jp8029743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Würthner F.; Saha-Möller C. R.; Fimmel B.; Ogi S.; Leowanawat P.; Schmidt D. Perylene Bisimide Dye Assemblies as Archetype Functional Supramolecular Materials. Chem. Rev. 2016, 11, 962–1052. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosztola D.; Niemczyk M. P.; Svec W.; Lukas A. S.; Wasielewski M. R. Excited Doublet States of Electrochemically Generated Aromatic Imide and Diimide Radical Anions. J. Phys. Chem. A 2000, 104, 6545–6551. 10.1021/jp000706f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bard A. J.; Faulkner L. R.. Electrochemical Methods: Fundamentals and Applications, 2nd ed.; Wiley: New York, 2001; pp 115–124. [Google Scholar]

- Costentin C. Electrochemical Approach to the Mechanistic Study of Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 2145–2179. 10.1021/cr068065t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg D. R.; Gagliardi C. J.; Hull J. F.; Murphy C. F.; Kent C. A.; Westlake B. C.; Paul A.; Ess D. H.; McCafferty D. G.; Meyer T. J. Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 4016–4093. 10.1021/cr200177j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks R. G., Ed. Stable Radicals: Fundamentals and Applied Aspects of Odd-Electron Compounds; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lü J.-M.; Rosokha S. V.; Kochi J. K. Stable (Long-Bonded) Dimers via the Quantitative Self-Association of Different Cationic, Anionic, and Uncharged Π-Radicals: Structures, Energetics, and Optical Transitions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 12161–12171. 10.1021/ja0364928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novoa J. J.; Miller J. S. Four-Center Carbon-Carbon Bonding. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007, 40, 189–198. 10.1021/ar068175m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Y.-H.; Kertesz M. Is There a Lower Limit to the CC Bonding Distances in Neutral Radical Pi-Dimers? The Case of Phenalenyl Derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 10648–10649. 10.1021/ja103396h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita Y.; Suzuki S.; Fukui K.; Nakazawa S.; Kitagawa H.; Kishida H.; Okamoto H.; Naito A.; Sekine A.; Ohashi Y.; Shiro M.; Sasaki K.; Shiomi D.; Sato K.; Takui T.; Nakasuji K. Thermochromism in an Organic Crystal Based on the Coexistence Of Σ- And Π-Dimers. Nat. Mater. 2008, 7, 48–51. 10.1038/nmat2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta K.; Chatterjee S.; Samanta S.; Dey A. Direct Observation of Intermediates Formed During Steady-State Electrocatalytic O2 Reduction by Iron Porphyrins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 110, 8431–8436. 10.1073/pnas.1300808110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigsby M. L.; Wasylenko D. J.; Pegis M. L.; Mayer J. M. Medium Effects are as Important as Catalyst Design for Selectivity in Electrocatalytic Oxygen Reduction by Iron-porphyrin Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 4296–4299. 10.1021/jacs.5b00359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horak K. T.; Agapie T. Dioxygen Reduction by a Pd(0)–Hydroquinone Diphosphine Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 3443–3452. 10.1021/jacs.5b12928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treimer S.; Tang A.; Johnson D. C. Consideration of the Application of Koutecky-Levich Plots in the Diagnosis of Charge-Transfer Mechanisms at Rotated Disk Electrodes. Electroanalysis 2002, 14, 165–171. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dai L.; Xue Y.; Qu L.; Choi H. J.; Baek J. B. Metal-Free Catalysts for Oxygen Reduction Reaction. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 4823–4892. 10.1021/cr5003563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costentin C.; Drigi H.; Savéant J.-M. Molecular Catalysis of O2 Reduction by Iron Porphyrins in Water: Heterogeneous versus Homogeneous Pathways. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 13535–13544. 10.1021/jacs.5b06834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savéant J.-M.Elements of Molecular and Biomolecular Electrochemistry: An Electrochemical Approach to Electron Transfer Chemistry; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, 2006; pp 96–102. [Google Scholar]

- Guo D.; Shibuya R.; Akiba C.; Saji S.; Kondo T.; Nakamura J. Active Sites of Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Materials for Oxygen Reduction Reaction Clarified Using Model Catalysts. Science 2016, 351, 361–365. 10.1126/science.aad0832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin L.; Liebscher J. Carbon-Carbon Coupling Reactions Catalyzed by Heterogeneous Palladium Catalysts. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 133–173. 10.1021/cr0505674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. M.SHELXTL 2008/4 Structure Determination Software Suite; Bruker AXS: Madison, WI, 2008.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.