Abstract

Objective

to assess how informed patients are about breast reconstruction, and how involved they are in decision making.

Summary Background Data

Breast reconstruction is an important treatment option for patients undergoing mastectomy. Wide variations in who gets reconstruction, however, have led to concerns about decision making.

Methods

We conducted a prospective cross-sectional study of patients planning mastectomy at a single site, over 20 months. Before surgery, patients completed a survey with validated scales to assess knowledge about breast reconstruction and involvement in decision making. Factors associated with knowledge were examined in a multivariable linear regression model.

Results

145 patients enrolled (77% enrollment rate), and 126 remained eligible. The overall knowledge score was 58.5% (out of 100%). Knowledge about risk of complications was especially low at 14.3%. Knowledge did not differ by treatment (reconstruction or not). On multivariable analysis, non-white race was independently associated with lower knowledge. Most patients (92.1%) reported some discussion with a provider about reconstruction, and most (90.4%) reported being asked their preference. More patients reported discussing the advantages of reconstruction (57.9%) than the disadvantages (27.8%).

Conclusions

Women undergoing mastectomy in this sample were highly involved in decision making but had major deficits in knowledge about the procedure. Knowledge about the risk of complications was particularly low. Providers appeared to have discussed the advantages of reconstruction more than its disadvantages.

INTRODUCTION

Breast reconstruction is an important treatment option for women undergoing mastectomy. Most women who have a mastectomy are candidates for breast reconstruction, and insurance coverage of the procedure is mandated by federal and state laws. Most women who have a mastectomy, however, do not undergo reconstruction,1–3 and rates of reconstruction vary substantially by race/ethnicity, age, income, and geographic location.1, 3–7 The rate of reconstruction in white women is about 40%, whereas in African American women, it is about 34%, and in low-acculturated Latina women, about 14%.7

Variations in rates of breast reconstruction have led to concerns about the quality of decision making for the procedure. One concern is that many patients may not be receiving enough information to guide their decisions. In retrospective studies, approximately 20% of women who had mastectomy reported no discussion about breast reconstruction with their provider.1, 6, 8 Minority women are less likely to report a discussion about breast reconstruction,1, 4, 6 and they have lower knowledge about reconstruction.8 Concern also exists because many women are unsatisfied with their choice to receive or not receive reconstruction. As many as 47% of women undergoing reconstruction have reported regret over the decision.9 In addition, satisfaction with decisions about reconstruction is lower among minority women.7

Currently, it is difficult to determine whether these concerns about decision making quality are justified. Prior studies of breast reconstruction decisions have primarily been retrospective, measuring knowledge and involvement in decision making months or even years after treatment.1, 6, 7 Thus, how informed patients are about reconstruction at the time of decision making remains unclear. To better understand how patients make this decision, we conducted a prospective study assessing how informed patients are about breast reconstruction, and how involved they are in the decision making process, prior to mastectomy. We were specifically interested in knowledge about the advantages and disadvantages of reconstruction and its alternatives.

METHODS

Study design

We conducted a prospective cohort study of patients planning to have mastectomy at a single site, over a 20-month period. Here we report on results from the baseline assessment. The site of the study was the Breast Clinic of the North Carolina Cancer Hospital, which is part of a National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer and treats approximately 500 Stage 0-III breast patients annually. The study was approved by the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill Institutional Review Board and registered with clinicaltrials.gov.

Study population

Adult women (21 years or older) planning to have mastectomy were enrolled prior to surgery from June 2012 to February 2014. Women undergoing mastectomy for treatment of early stage (I-III) invasive ductal or lobular breast cancer, treatment of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), or prophylaxis (eg, patients with BRCA mutation) were included. We excluded patients with stage IV disease and other histologic types (eg, sarcoma, desmoid, or metaplastic tumors), since their clinical courses and prognoses differ substantially from that of Stages 0-III lobular or ductal carcinoma. We also excluded patients with a psychiatric illness who could not make their own decisions. We excluded patients who could not read or speak English because we did not have survey measures in other languages or resources for interpretation.

Clinical flow

At the study site, patients with incident breast cancer or DCIS are discussed at the multidisciplinary conference in the morning and then seen by a surgical oncologist in multidisciplinary breast clinic the same day or in the surgeon’s individual clinic on another day. Patients who are considering post-mastectomy reconstruction see a plastic surgeon, usually within about 1 week.

Enrollment

The research assistant initially identified eligible patients by screening clinic schedules. She then confirmed eligibility at the multidisciplinary breast conference or through discussion with the surgical oncologist. Most eligible patients were approached in clinic, immediately after the surgical oncology visit, although some patients were approached by mail. Permission to approach the patient was confirmed with the surgical oncologist. For patients who were undecided about surgery (mastectomy versus partial mastectomy) at the end of the surgical oncology visit, the research assistant tracked them until a surgery decision was made, and then approached those having mastectomy about enrollment. We attempted to approach every eligible patient during the study period.

After patients provided informed consent, they were given a paper questionnaire, to be completed in clinic or at home prior to surgery. Among patients who saw a plastic surgeon after the surgical oncology visit, some completed the survey before the plastic surgery visit, and some completed it after that visit. Patients noted the date of survey completion, and we recorded dates of clinic visits. Patients who did not return the survey by 2 weeks after enrollment were reminded with a phone call. Those who did not return the survey by 4 weeks, and who had not yet had surgery, were mailed a reminder packet with the survey. Patients who completed the survey after surgery were considered ineligible and removed from the study. Participants were mailed a $50 gift card.

Measures

The survey contained questions about demographics, knowledge about breast reconstruction, and involvement in decision making. It also included questions about preferences related to breast reconstruction, quality of life, and emotional well-being, about which we are not reporting here. Demographic, medical, and treatment data were abstracted from the medical record.

Demographics

These questions asked about education, marital status, race, ethnicity, employment status, and income.

Decision Quality Instrument

The Breast Reconstruction Decision Quality Instrument© (DQI) was used to measure knowledge about reconstruction and involvement in decision making. The DQI was designed to evaluate condition-specific (rather than generic) knowledge, so it asks questions about specific aspects of the breast reconstruction process and its outcomes. Each of these aspects had been deemed by breast cancer survivors and providers a “key fact” about reconstruction, in the instrument development process.10 Further details of the DQI development and validation process have been described before.10–12 The DQI covers three broad domains.

Knowledge about specifics of breast reconstruction: Nine multiple-choice items on the evidence about satisfaction with and without reconstruction, recovery time, number of surgeries, types of reconstruction, complication risk, radiation effects, breast cancer surveillance after reconstruction, and risk of recurrence after reconstruction.

Involvement in decision making. Four multiple choice items on whether or not the provider discussed the option of reconstruction, how much the advantages of reconstruction were discussed, how much the disadvantages of reconstruction were discussed, and whether or not the provider ask the patient her treatment preference. Additional items asked whether or not the provider discussed use of a prosthesis as an option, how much the provider addressed the patients’ concerns about how she would look after mastectomy, and how much the patient felt involved in decision making.

Goals and concerns. Seven items assess goals and concerns related to reconstruction. These items will be reported separately, along with other data on preferences.

Statistical analysis

We calculated descriptive summary statistics, including means and standard deviations for continuous variables, and frequencies and standard deviations for categorical variables. Demographic characteristics of patients having mastectomy only were compared to those of patients having mastectomy with reconstruction, using t-tests for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables.

Knowledge

We created knowledge scores for each patient who completed at least 50% of the knowledge questions, by dividing the number of correct responses by 9, with missing responses counted as incorrect. For individual items, responses were compared between treatment groups (reconstruction or not) using Fisher’s exact tests. Factors associated with knowledge (socio-demographic and clinical characteristics, provider, and involvement in decision making) were examined using linear regression models. We compared overall knowledge among participants who completed the survey after seeing a plastic surgeon to overall knowledge among others (those who completed the survey before seeing a plastic surgeon or who did not see a plastic surgeon) using t-tests.

Involvement in decision making

An involvement score was computed by assigning 1 possible point for each of the four primary involvement questions (a “yes” response to whether or not reconstruction was described as an option, a response of “a lot/some” to discussion of advantages, a response of “a lot/some” to discussion of disadvantages, a “yes” response to whether the provider asked for the patient’s treatment preference). Descriptive statistics were computed for the additional involvement questions and compared using Fisher’s exact tests.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

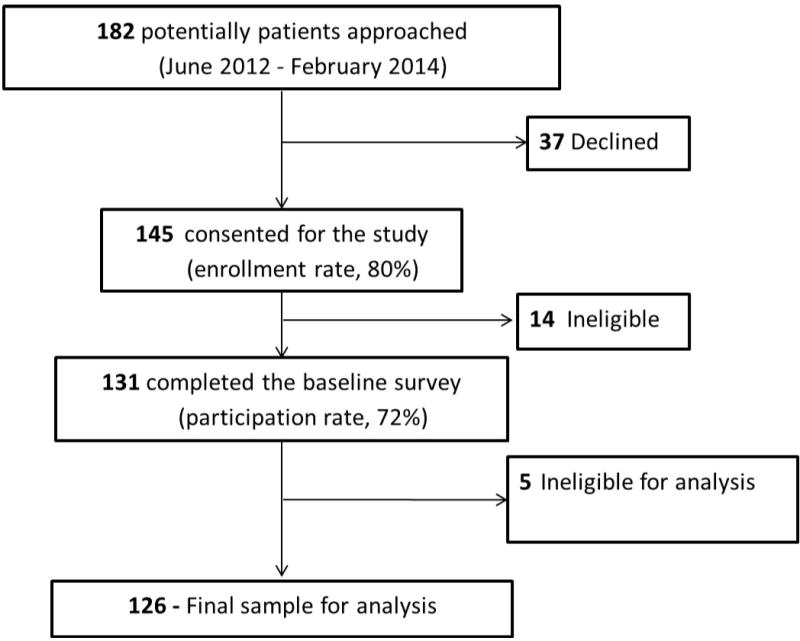

During the study period July 2012 to February 2014, 214 patients were eligible. Of those 214 eligible patients, we approached 182 and missed 32 (5 at the surgeon’s request, 27 who left clinic before we could approach). Of the 182 we approached, 145 enrolled (80% enrollment rate), and 131 completed the survey (72% participation rate) (Figure 1). Five participants became ineligible for various reasons (e.g., had surgery elsewhere, completed the survey after surgery), leaving a final study population of 126 patients (Table 1). The mean age was 53.2 years (SD 12.1), and 24.6% of participants were non-white. About half of the participants were college graduates, most were partnered, nearly half were not working, and half were privately insured. Most had stage 0-II disease, and one third received adjuvant radiation therapy. The immediate reconstruction rate was 40%, consistent with national norms.1, 3, 7 The 37 eligible patients who declined enrollment were similar to participants in mean age (53.1 years) and insured status (91.9%), but more of them were non-white (45.9%, p=0.01), and fewer of them had reconstruction (22%, p=0.05). Survey completion date was available for 116 participants. The median time between the first surgical oncology visit and survey completion was 15 days (81 days for patients who completed the survey after neoadjuvant chemotherapy). Forty of the 116 participants saw a plastic surgeon, and 31 out of 40 (78%) completed the survey after seeing the plastic surgeon.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram

Table 1.

Demographic and treatment characteristics of study sample.

| % of patients

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Mastectomy Only | Mastectomy w/Reconstruction | ||

| N=126 | N=75 | N=51 | p | |

| Age – mean (SD) | 53.2 (12.1) | 54.8 (13.8) | 50.9 (8.5) | 0.08 |

| Education | 0.10 | |||

| High school or less | 16.7 | 22.7 | 7.8 | |

| Some college | 34.9 | 32.0 | 39.2 | |

| College graduate or more | 47.6 | 44.0 | 52.9 | |

| Marital status | 0.01 | |||

| Married/committed | 65.1 | 54.7 | 80.4 | |

| Single/divorced/separated/widowed | 34.1 | 44.0 | 19.6 | |

| Race | 0.55 | |||

| White | 75.4 | 72.0 | 80.4 | |

| Black | 18.3 | 21.3 | 13.7 | |

| Other/multiracial | 6.3 | 6.7 | 5.9 | |

| Ethnicity | 0.23 | |||

| Hispanic | 4.8 | 4.0 | 5.9 | |

| Not Hispanic | 92.1 | 90.7 | 94.1 | |

| Employment status | 0.26 | |||

| Working full time | 39.7 | 33.3 | 49.0 | |

| Working part time/temporary leave | 15.1 | 17.3 | 11.8 | |

| Not working | 43.7 | 46.7 | 39.2 | |

| Annual household income | 0.01 | |||

| < $30,000 | 29.4 | 38.7 | 15.7 | |

| $30,000 – $59,999 | 17.5 | 20.0 | 13.7 | |

| $60,000 – $100,000 | 19.0 | 18.7 | 19.6 | |

| over $100,000 | 30.2 | 20.0 | 45.1 | |

| Primary insurance | 0.01 | |||

| No insurance | 6.3 | 6.7 | 5.9 | |

| Medicaid only | 7.1 | 12.0 | 0.0 | |

| Medicare or Tricare | 31.0 | 34.7 | 25.5 | |

| Private insurance | 55.6 | 46.7 | 68.6 | |

| Diagnosis and stage | <0.0001 | |||

| No malignancy | 13.5 | 1.3 | 31.4 | |

| Ductal carcinoma in situ | 16.7 | 9.3 | 27.5 | |

| Invasive ductal carcinoma | ||||

| Stage I | 35.7 | 37.3 | 33.3 | |

| Stage II | 20.6 | 29.3 | 7.8 | |

| Stage III | 13.5 | 22.7 | 0.0 | |

| Surgical treatment | <0.0001 | |||

| Unilateral mastectomy | 55.6 | 72.0 | 31.4 | |

| Bilateral mastectomy | 44.4 | 28.0 | 68.6 | |

| Adjuvant radiation | <0.0001 | |||

| Yes | 31.7 | 49.3 | 5.9 | |

| No | 68.3 | 50.7 | 94.1 | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 0.01 | |||

| Yes | 25.4 | 33.3 | 13.7 | |

| No | 74.6 | 66.7 | 86.3 | |

Knowledge

All but five patients (4%) completed at least half of the knowledge questions and had a knowledge score computed. The mean knowledge score was 58.5% (SD 16.2) (Table 2), and 70.2% of participants had a knowledge score of at least 50%. Knowledge was especially low for the question on risk of complications, with only 14.3% of participants answering correctly that the risk of a major complication in the first two years was 16–40%. Nearly all those who answered incorrectly underestimated the risk. Knowledge was also low for the two questions on satisfaction, with only 40.0% of participants answering correctly that women who have reconstruction and women who have mastectomy only are equally satisfied. Knowledge was higher about recovery, number of procedures, recovery after flaps versus implants, and future cancer risk. Overall knowledge and knowledge of specific questions did not differ by whether or not participants had reconstruction. Overall knowledge among participants who completed the survey after a seeing a plastic surgeon (mean 62.0) was higher than overall knowledge among participants who completed the survey before seeing a plastic surgeon (mean 56.8, p = 0.12), but the difference was not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Knowledge of specific topics about breast reconstruction after mastectomy, by treatment

| % of patients

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question and responses* (correct response in bold italics) | Total | Mastectomy Only | Mastectomy w/Reconstruction | |

| n=126 | n=75 | n=51 | p** | |

| Which women are more satisfied after mastectomy? | 0.46 | |||

| Women who have reconstruction | 55.6 | 50.7 | 62.7 | |

| Women who do not have reconstruction | 1.6 | 2.7 | 0.0 | |

| They are equally satisfied | 38.1 | 41.3 | 33.3 | |

| Which has a longer recovery time? | 0.21 | |||

| Mastectomy without reconstruction | 8.7 | 10.7 | 5.9 | |

| Mastectomy with reconstruction | 76.2 | 72.0 | 82.4 | |

| They have the same recovery time | 11.9 | 12.0 | 11.8 | |

| Which is more likely to require more than one surgery or procedure? | 0.03 | |||

| Mastectomy without reconstruction | 15.1 | 21.3 | 5.9 | |

| Mastectomy with reconstruction | 77.8 | 70.7 | 88.2 | |

| They require the same number | 3.2 | 4.0 | 2.0 | |

| After which reconstruction are women more satisfied with the look and feel? | 0.57 | |||

| Implants | 26.2 | 28.0 | 23.5 | |

| Flap procedures | 34.1 | 32.0 | 37.3 | |

| Both are about the same | 33.3 | 30.7 | 37.3 | |

| Which surgery is easier on the body, heals faster? | 0.34 | |||

| Implants are easier | 65.1 | 61.3 | 70.6 | |

| Flaps are easier | 8.7 | 9.3 | 7.8 | |

| Implants and flaps are equally easy | 19.8 | 20.0 | 19.6 | |

| Out of 100 women who have reconstruction, how many will have a major complication, within 2 years? | 0.12 | |||

| Fewer than 5 | 36.5 | 34.7 | 39.2 | |

| 5–15 | 43.7 | 38.7 | 51.0 | |

| 16–40 | 14.3 | 18.7 | 7.8 | |

| More than 40 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 0.0 | |

| How does radiation affect the number of complications? | 0.18 | |||

| Radiation increases the # of complications | 67.5 | 62.7 | 74.5 | |

| Radiation decreases the # of complications | 7.9 | 9.3 | 5.9 | |

| Radiation does not affect the # of complications | 20.6 | 21.3 | 19.6 | |

| How does reconstruction affect future screening? | 0.46 | |||

| Makes it harder to find cancer | 24.6 | 25.3 | 23.5 | |

| Makes it easier to find cancer | 5.6 | 6.7 | 3.9 | |

| Has little or no effect on finding cancer | 61.9 | 58.7 | 66.7 | |

| How does reconstruction affect chance of cancer coming back? | 0.67 | |||

| Increases the chance of cancer coming back | 3.2 | 5.3 | 0.0 | |

| Decreases the chance of cancer coming back | 15.1 | 8.0 | 25.5 | |

| Has little or no effect on cancer coming back | 75.4 | 77.3 | 72.5 | |

| Overall knowledge (out of 100) – mean (SD) | 58.5 (16.2) | 57.9 (16.6) | 59.3 (15.8) | 0.66 |

Some wording has been shortened to fit this table

Comparison between % correct vs incorrect/missing

On bivariable analysis, non-white race, less education, lower income, and single relationship status were associated with lower knowledge about breast reconstruction (Table 3). On multivariable analysis, only non-white race was independently associated with lower knowledge (Table 3).

Table 3.

Bivariable and multivariable (linear regression) analyses of factors associated with knowledge (significant factors in bold)

| Bivariable | Multivariable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Mean knowledge score (% correct) | p | Regression coefficient | p |

| Age | 0.83 | −0.13 | 0.97 | |

| < 50 years | 58.1 | |||

| >=50 years* | 58.8 | |||

| Race | <0.0001 | 11.97 | 0.00 | |

| White | 62.0 | |||

| Non−white* | 46.8 | |||

| Education | 0.06 | −2.22 | 0.60 | |

| High school or less | 52.1 | |||

| College or more* | 59.6 | |||

| Annual income | 0.01 | −4.67 | 0.22 | |

| < $60,000 | 54.2 | |||

| >= $60,000* | 62.0 | |||

| Marital Status | 0.14 | −2.01 | 0.59 | |

| Partnered | 60.0 | |||

| Single/divorced/widowed* | 55.3 | |||

| Diagnosis | ||||

| No malignancy | 59.5 | 0.89 | −2.51 | 0.62 |

| DCIS | 56.1 | 0.48 | −3.11 | 0.44 |

| Invasive breast cancer* | 58.9 | |||

| Surgical cancer treatment | 0.18 | −2.99 | 0.37 | |

| Unilateral mastectomy | 56.7 | |||

| Bilateral mastectomy* | 60.7 | |||

| Insurance | 0.44 | −2.33 | 0.70 | |

| No | 54.2 | |||

| Yes* | 58.8 | |||

| Involvement score (0–4) | 0.99 | −0.38 | 0.90 | |

| <3 points | 58.8 | |||

| >=3 points | 58.8 | |||

referent group

Involvement in decision making

Most patients (92.1%) reported some discussion with a provider about breast reconstruction (Table 4), and most (90.4%) reported that they were asked for their preference about reconstruction. Although many patients reported discussing the advantages of reconstruction some or a lot (57.9%), far fewer reported discussing the disadvantages some or a lot (27.8%). This difference was even larger for patients who had reconstruction (76.5% advantages versus 31.4% disadvantages).

Table 4.

Involvement in decision making

| % of patients

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Mastectomy Only | Mastectomy w/Reconstruction | ||

| Question and responses | N=126 | N=75 | N=51 | p |

| Have any of your providers discussed breast reconstruction as an option for you? | 0.01 | |||

| Yes | 92.1 | 86.7 | 100.0 | |

| No | 7.9 | 13.3 | 0.0 | |

| Have any of your providers discussed using a prosthesis as an option for you? | 0.27 | |||

| Yes | 46.4 | 41.9 | 52.9 | |

| No | 53.6 | 58.1 | 47.1 | |

| How much have you and your providers discussed reasons to have breast reconstruction? | <0.001 | |||

| A lot/Some | 57.9 | 45.3 | 76.5 | |

| A little/Not at all | 42.1 | 54.7 | 23.5 | |

| How much have you and your providers discussed reasons not to have breast reconstruction? | 0.54 | |||

| A lot/Some | 27.8 | 25.3 | 31.4 | |

| A little/Not at all | 72.2 | 74.7 | 68.6 | |

| Have any of your providers asked whether or not you want to have reconstruction? | 0.03 | |||

| Yes | 90.4 | 85.3 | 98.0 | |

| No | 9.6 | 14.7 | 2.0 | |

| How much have you and your providers talked about your concerns about appearance? | <0.0001 | |||

| A lot/Some | 44.4 | 28.8 | 66.7 | |

| A little/Not at all | 55.6 | 71.2 | 33.3 | |

| How much are you involved in making the decision about breast reconstruction? | 0.36 | |||

| More than I want | 9.1 | 9.9 | 8.0 | |

| About as much as I want | 88.4 | 85.9 | 92.0 | |

| Less than I want | 2.5 | 4.2 | 0.0 | |

Some questions have been reworded to fit this table.

Not all responses add to 100% due to missing data.

More of the patients who discussed the disadvantages of reconstruction “a lot” were able to correctly answer the question about complication risk (28.6%), compared to the rest of the study population (13.4%), but this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.26). Non-white patients were less likely to report any discussion of disadvantages (20.7%), compared to white patients (63.2, p<0.0001).

DISCUSSION

In this population of patients undergoing mastectomy for treatment or prevention of breast cancer, decisions about breast reconstruction were only moderately well-informed. Patients answered nearly half of the knowledge questions incorrectly, and knowledge about the risk of complications was particularly low. Minority women, less educated women, and lower-income women had lower knowledge.

Our findings of limited knowledge about breast reconstruction are consistent with prior research on patient knowledge about reconstruction and other breast cancer treatments. In our prior retrospective study, which also used the Decision Quality Instrument, overall knowledge about reconstruction 2.5 years after mastectomy was 37.9%.13 Knowledge about breast cancer surgery (mastectomy versus breast conserving surgery) has also been limited in prior studies, with patients correctly answering about half of questions about the pros and cons of surgery.14–16 Patients also have incomplete knowledge about systemic therapy, with frequent overestimation of the survival benefit of chemotherapy.17, 18 Our participants were more educated than the average population of women undergoing mastectomy for breast cancer, and could all read or speak English. Given the demographics of our study population, we expect that knowledge about reconstruction in the breast cancer population at large may be even lower than what we found here.

Knowledge about the risk of complications was particularly low at 15%. In our prior retrospective study, knowledge about complication risk was even lower, at 3%.13 The DQI question on complication risk was developed using the best available evidence about long-term complications of reconstruction.13, 19 That evidence has found complication rates in the range of 20–33%.20–22 Although other studies have reported complication rates in the 5–15% range, they have been limited to short-term (usually 30-day) complications21, 23, 24 or have not reported follow-up duration.25 Low knowledge about reconstruction complications is consistent with prior literature on communication about risk. Patients tend to know less about the disadvantages than the advantages of treatments,26 and providers’ estimations or communications of risk can be biased by optimism.27, 28 Some providers have limited numeracy, which affects how well they communicate to patients about risk.29, 30

Our assessment of knowledge had some limitations. Patients answered knowledge questions about two weeks after the surgical oncology visit, so they may have forgotten some information that the surgeon had discussed. The measured levels of knowledge, however, do reflect what patients knew around the time that they were undergoing surgery, which we believe is when their knowledge about the procedure is most important. Some patients who saw a plastic surgeon completed the survey before the plastic surgery visit, so they may eventually have had higher knowledge about reconstruction than what the survey measured. We did in fact find that patients who completed the survey after the plastic surgery visit had somewhat higher knowledge than those who completed it before the visit or who never saw a plastic surgeon, but the difference was not statistically significant. Just how much knowledge about reconstruction patients ought to have, if they are not considering reconstruction, is not entirely clear. Surgical oncologists may choose not to discuss the disadvantages of reconstruction with patients who are not interested in the procedure, and this is reasonable. Interestingly, patients in this sample who were having reconstruction were no more knowledgeable about complications than patients not having reconstruction.

Patients in this sample were more involved in the decision making process than has been reported before. Most patients (92.1%) reported that their provider discussed the option of reconstruction and that their provider asked for their preference about reconstruction (90.4%). In retrospective, multi-site, and population-based studies of breast cancer survivors, a smaller percentage (74–81%) of patients recalled a discussion about reconstruction with their provider.6, 8, 13, 31 One possible explanation for our finding of higher involvement is that we asked patients about their decision approximately 2 weeks after the surgical oncology visit and prior to surgery, whereas most other studies have asked about involvement months or years later. Thus, patients in our study may have had better recall of their involvement in the consultation than in other studies. Our study was limited by its setting of a single academic institution, and by a population that was more educated and wealthier than the average. Thus findings about involvement may not be generalizable to the breast cancer patient population at large. We expect that involvement in this study may have been higher than the average.

Lower knowledge was associated with non-white race, less education, lower income, and single relationship status, on bivariable analysis. In addition, non-white race was independently associated with lower knowledge. We are uncertain why this was the case. We attempted to examine potential confounders of the relationship between race and knowledge, such as education, insurance, income, and involvement. Our sample size was somewhat limited, however, and we did not measure some potentially important variables, such as literacy or numeracy. Our sample was also limited to women who could read or speak English, so we cannot comment on the knowledge or decisional involvement of breast cancer patients who do not communicate in English. Such women would be important to future studies, since low-acculturated Latina women and minority women in general are less likely to have breast reconstruction.7 Finally, we did not directly observe patient involvement in the decision. In the future, audio recordings of the patient-provider conversation could provide some insight.

How much knowledge a patient must have in order to make an informed choice is not entirely clear. We based our approach to evaluating decisions on a theoretical framework of decision quality which requires that patients understand the advantages and disadvantages of the options and make a choice consistent with their values.32–35 Our measure of knowledge was based on that framework36 and included questions about facts that patients and providers had deemed critical to the decision about reconstruction.19 One conservative definition of being informed would require correct responses to 50% of knowledge questions.37 By this definition, 70% of our sample was minimally informed. Different opinions exist about what constitutes a minimal acceptable level of knowledge, however, and further research on this issue would be useful.

Conclusion

Women undergoing mastectomy in this sample were highly involved in the decision about breast reconstruction, but they had major deficits in knowledge about the procedure. Knowledge about the risk of complications was particularly low. Providers appeared to have discussed the advantages of reconstruction more than its disadvantages.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Ruth Huh for her assistance with statistical analyses and the patients and surgeons who participated in this study.

Funding:

National Institutes of Health 1K07CA154850-01A1 Cancer Prevention, Control, Behavioral, and Population Sciences Career Development Award (National Cancer Institute); Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center Population Sciences Cancer Research Award; North Carolina Translational and Clinical Sciences Institute Pilot Award

Contributor Information

Clara Nan-hi Lee, Department of Surgery, School of Medicine; Department of Health Policy and Management, School of Public Health; Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center; University of North Carolina Chapel Hill.

Peter Anthony Ubel, Department of Marketing, Fuqua School of Business; Duke University.

Allison M Deal, Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center Biostatistics Core Facility; University of North Carolina Chapel Hill.

Lillian Burdick Blizard, Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center; University of North Carolina Chapel Hill.

Karen R Sepucha, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital; Department of Medicine, Harvard Medical School.

David W. Ollila, Department of Surgery, School of Medicine; Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center; University of North Carolina Chapel Hill.

Michael Patrick Pignone, Department of Medicine, School of Medicine; Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center; University of North Carolina Chapel Hill.

References

- 1.Morrow M, Li Y, Alderman AK, et al. Access to Breast Reconstruction After Mastectomy and Patient Perspectives on Reconstruction Decision Making. JAMA Surg. 2014 doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albornoz CR, Bach PB, Mehrara BJ, et al. A paradigm shift in U.S. Breast reconstruction: increasing implant rates. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131(1):15–23. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182729cde. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christian CK, Niland J, Edge SB, et al. A multi-institutional analysis of the socioeconomic determinants of breast reconstruction: a study of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Ann Surg. 2006;243(2):241–9. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000197738.63512.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tseng JF, Kronowitz SJ, Sun CC, et al. The effect of ethnicity on immediate reconstruction rates after mastectomy for breast cancer. Cancer. 2004;101(7):1514–23. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joslyn SA. Patterns of care for immediate and early delayed breast reconstruction following mastectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115(5):1289–96. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000156974.69184.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen JY, Malin J, Ganz PA, et al. Variation in physician-patient discussion of breast reconstruction. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(1):99–104. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0855-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alderman AK, Hawley ST, Janz NK, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in the use of postmastectomy breast reconstruction: results from a population- based study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(32):5325–30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.2455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrow M, Mujahid M, Lantz PM, et al. Correlates of breast reconstruction: results from a population-based study. Cancer. 2005;104(11):2340–6. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheehan J, Sherman KA, Lam T, et al. Association of information satisfaction, psychological distress and monitoring coping style with post-decision regret following breast reconstruction. Psychooncology. 2007;16(4):342–51. doi: 10.1002/pon.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee CN, Dominik R, Levin CA, et al. Development of instruments to measure the quality of breast cancer treatment decisions. Health Expect. 2010;13(3):258–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2010.00600.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sepucha KR, Belkora JK, Chang Y, et al. Measuring decision quality: psychometric evaluation of a new instrument for breast cancer surgery. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:51. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-12-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee CN, Wetschler MH, Chang Y, et al. Measuring decision quality: psychometric evaluation of a new instrument for breast cancer chemotherapy. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2014;14(1):73. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-14-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee CN, Belkora J, Chang Y, et al. Are patients making high-quality decisions about breast reconstruction after mastectomy? [outcomes article] Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(1):18–26. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181f958de. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hawley ST, Griggs JJ, Hamilton AS, et al. Decision involvement and receipt of mastectomy among racially and ethnically diverse breast cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(19):1337–47. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hawley ST, Fagerlin A, Janz NK, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in knowledge about risks and benefits of breast cancer treatment: does it matter where you go? Health Serv Res. 2008;43(4):1366–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00843.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee CN, Chang Y, Adimorah N, et al. Decision making about surgery for early-stage breast cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee CN, Wetschler MH, Chang Y, et al. Measuring decision quality: psychometric evaluation of a new instrument for breast cancer chemotherapy. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2014;14:73. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-14-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mandelblatt JS, Sheppard VB, Hurria A, et al. Breast cancer adjuvant chemotherapy decisions in older women: the role of patient preference and interactions with physicians. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(19):3146–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.3295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee CN, D R, Levin CA, Barry MJ, Cosenza C, O’Connor AM, Mulley AG, Sepucha K. Development of instruments to measure the quality of breast cancer treatment decisions. Health Expectations. 2010:29. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2010.00600.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alderman AK, Wilkins EG, Kim HM, et al. Complications in postmastectomy breast reconstruction: two-year results of the Michigan Breast Reconstruction Outcome Study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109(7):2265–74. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200206000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cordeiro PG, Albornoz CR, McCormick B, et al. The impact of postmastectomy radiotherapy on two-stage implant breast reconstruction: an analysis of long-term surgical outcomes, aesthetic results, and satisfaction over 13 years. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134(4):588–95. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Momoh AO, Ahmed R, Kelley BP, et al. A systematic review of complications of implant-based breast reconstruction with prereconstruction and postreconstruction radiotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(1):118–24. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3284-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fischer JP, Wes AM, Tuggle CT, et al. Risk analysis and stratification of surgical morbidity after immediate breast reconstruction. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217(5):780–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen CL, Shore AD, Johns R, et al. The impact of obesity on breast surgery complications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128(5):395e–402e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182284c05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nguyen KT, Hanwright PJ, Smetona JT, et al. Body mass index as a continuous predictor of outcomes after expander-implant breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2014;73(1):19–24. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e318276d91d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Graves KD, Peshkin BN, Halbert CH, et al. Predictors and outcomes of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy among breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;104(3):321–9. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9423-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Christakis NA, Iwashyna TJ. Attitude and self-reported practice regarding prognostication in a national sample of internists. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(21):2389–95. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.21.2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dale W, Hemmerich J, Ghini EA, et al. Can induced anxiety from a negative earlier experience influence vascular surgeons’ statistical decision-making? A randomized field experiment with an abdominal aortic aneurysm analog. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203(5):642–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garcia-Retamero R, Wicki B, Cokely ET, et al. Factors predicting surgeons’ preferred and actual roles in interactions with their patients. Health Psychol. 2014;33(8):920–8. doi: 10.1037/hea0000061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson TV, Abbasi A, Schoenberg ED, et al. Numeracy among trainees: are we preparing physicians for evidence-based medicine? J Surg Educ. 2014;71(2):211–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2013.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen JY, Diamant AL, Thind A, et al. Determinants of breast cancer knowledge among newly diagnosed, low-income, medically underserved women with breast cancer. Cancer. 2008;112(5):1153–61. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sepucha K, Mulley AG., Jr A perspective on the patient’s role in treatment decisions. Med Care Res Rev. 2009;66(1 Suppl):53S–74S. doi: 10.1177/1077558708325511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sepucha K, Ozanne E, Silvia K, et al. An approach to measuring the quality of breast cancer decisions. Patient education and counseling. 2007;65(2):261–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.08.007. Epub 2006 Oct 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elwyn G, O’Connor A, Stacey D, et al. Developing a quality criteria framework for patient decision aids: online international Delphi consensus process. BMJ. 2006;333(7565):417. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38926.629329.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mulley A, Sepucha K. Making Good Decisions about Breast Cancer Chemoprevention. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(1):52–4. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-1-200207020-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sepucha KR, Fowler FJ, Jr, Mulley AG., Jr Policy support for patient-centered care: the need for measurable improvements in decision quality. Health affairs (Project Hope) 2004 doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.var.54. Suppl Web Exclusive:VAR54-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hersch J, Barratt A, Jansen J, et al. Use of a decision aid including information on overdetection to support informed choice about breast cancer screening: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60123-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]