Abstract

Objective

This field study aimed to assess the noise reduction of hearing protection for individual workers, demonstrate the effectiveness of training on the level of protection achieved, and measure the time required to implement hearing protector fit-testing in the workplace.

Design

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) conducted field studies in Louisiana and Texas to test the performance of HPD Well-Fit.

Study Sample

Fit tests were performed on 126 inspectors and engineers working in the offshore oil industry.

Results

Workers were fit tested with the goal of achieving a 25 dBA PAR. Less than half of the workers were achieving sufficient protection from their hearing protectors prior to NIOSH intervention and training; following re-fitting and re-training, over 85% of the workers achieved sufficient protection. Typical test times were 6 to 12 minutes.

Conclusions

Fit testing of the workers’ earplugs identified those workers who were and were not achieving the desired level of protection. Recommendations for other hearing protection solutions were made for workers who could not achieve the target PAR. The study demonstrates the need for individual hearing protector fit testing and addresses some of the barriers to implementation.

Introduction

Noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL) is one of the most common occupational injuries in the United States and represents a substantial health burden both nationally and globally (Masterson et al. 2015). An estimated 22 million US workers are exposed to hazardous levels of noise greater than 85 dBA (Tak and Calvert, 2008), and as many as 10 million US workers have sustained occupational NIHL (Nelson et al., 2005). Hearing loss has a substantial impact on the individual worker and on society as a whole in terms of health, economics, and quality of life (Masterson et al., 2016). While NIHL is permanent and irreversible, it is also completely preventable.

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) recommends that workers’ noise exposure levels not exceed 85 dBA time-weighted average (TWA) determined using a 3-dB exchange rate. Furthermore, NIOSH recommends that no exposure exceed peak levels of 140 dB (NIOSH, 1998). When noise exposures exceed these recommended limits and when engineering and administrative noise controls are not feasible to reduce exposures to a safe level, NIOSH recommends use of appropriate hearing protection devices (HPDs) to protect worker hearing.

The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) requires that all hearing protection sold in the United States be labeled with a Noise Reduction Rating or NRR (EPA, 1978). The NRR was designed to predict the amount of noise reduction that could be achieved by 98% of workers if they used the hearing protection as directed; however, research has shown that fewer than 5% of workers actually achieve the level of protection predicted by the NRR (Berger et al., 1998). Hearing protector attenuation varies greatly from worker to worker. Various de-rating schemes have been recommended in which the NRR is multiplied by a percentage to better reflect the performance that people typically achieve (e.g., NIOSH, 1998; OSHA, 2016). Franks et al. (2000) demonstrated that de-rating schemes fail to predict attenuations of persons with minimal experience with hearing protector use. The failure to properly fit and wear hearing protectors has been cited as a significant factor for occupational hearing loss amongst noise exposed workers (Heyer et al, 2010; Themann et al., 2013).

The NRR is calculated from attenuation measures done under laboratory conditions using real ear attenuation at threshold (REAT), the difference between the hearing thresholds for occluded and unoccluded conditions for one-third octave narrow-band noise stimuli determined in a diffuse sound field. Hearing protector fit testing attempts to recreate the diffuse sound field used in the laboratory REAT test. Some fit-testing systems create a sound field under large volume circumaural headphones and use the same REAT approach to measure the difference between the occluded and unoccluded thresholds for noise bands presented under headphones. This method can only be used to test earplugs. Other fit-test systems create a sound field is with a loudspeaker and measure the sound level using two microphones placed just outside of the protector and in the ear canal under the hearing protector to determine the noise reduction. This approach is called Microphone-In-Real-Ear (MIRE) and can be used to test any hearing protector. Each fit-test method combines the attenuation measurements at different frequencies to determine a personal attenuation rating (PAR) for the individual who was tested.

NIOSH developed the first fit-test system through a contract with The Pennsylvania State University (Michael et al., 1976). Edwards and Green developed a fit-test system that was successfully used for several field studies (Edwards et al., 1978; Edwards et al., 1983; Edwards and Green, 1987). Unfortunately neither the NIOSH system nor the Edwards system was sufficiently portable to be used on a regular basis or in an office environment. In the mid-1990s, Michael & Associates developed the FitCheck hearing protector fit-testing system (Michael and Bloyer, 1999). The REAT test was administered using third octave band noise presented under headphones and was shown to provide comparable results with the standard sound-field test mandated by the EPA for laboratory tests (Franks et al., 2003). However, this system requires special equipment and test locations need to be sufficiently quiet so as not to mask the test stimulus in the unoccluded condition when the sound isolating headphones are used.

Over time, other fit-testing systems have been developed and studied for their performance both in laboratory and field environments (Murphy, 2013; Berger et al., 2011; Schulz, 2011; Byrne et al. 2016). Microphone in real-ear (MIRE) measurement systems such as Phonak’s SafetyMeter and 3M’s EARfit Validation System require use two microphones measure noise reduction of a protector. MIRE methods are quick, requiring only a few minutes to allow foam earplugs to expand fully and several seconds to make the measurement. However, MIRE-based systems are vendor specific; they require specially-modified hearing protectors to accommodate the microphone and the acoustic measurements and REAT measurements must be correlated for each model of earplug or earmuff to establish compensation factors (Voix, 2006; Voix and Laville, 2009). The Honeywell VeriPRO fit-test system uses an alternating loudness balance paradigm where the subject is tasked to sequentially match the loudness of tones between ears. The subject starts with both ears unoccluded and progresses to the right ear occluded and then both ears occluded. The presentation levels of the matched tones between the unoccluded and occluded conditions are used to estimate the attenuation of the earplug in each ear. The VeriPRO fit-test system requires about 15 minutes to conduct a fit test for five frequencies 250 to 4000 Hz (Trompette and Kusy, 2013).

The HPD Well-Fit system was developed to address some of the barriers to routine implementation of HPD fit testing. It requires only sound-isolating headphones, a laptop computer with a high-definition sound card and a computer mouse to implement the REAT paradigm. It can be used to test any type of earplug, and uses a unique threshold search paradigm that substantially reduces the time needed to establish thresholds.

Fit testing with the U.S. Department of Interior

The Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE) within the Department of the Interior contacted NIOSH about fit testing offshore oil-rig inspectors and engineers. The primary noise exposure for these workers is helicopter noise during transit to and from the oil rigs. Other noise sources on the oil-rig platforms include the drilling operation and generator rooms (Radtke, 2007). This field study reports on the results of fit testing workers using HPD Well-Fit™ – a REAT under headphones fit-test system developed by NIOSH. Workers were fit tested during site visits to Louisiana and Texas during 2012 and 2013. The attenuations, personal attenuation ratings (PARs) and testing times for the workers will be reported.

Methods

Study Design

Two site visits were made to BSEE locations in Louisiana and Texas. Workers were tested as a part of their annual hearing conservation training at the field office sites either prior to or following their travel to the off-shore location. Because HPD Well-Fit evaluates threshold differences rather than actual hearing thresholds, potential over-exposure due to noise from the helicopter for workers tested at the end of their day should not have significantly impacted their results. Fit-testing was conducted as a part of the employer’s hearing conservation program.

The first site visit was conducted in February 2012 and surveyed workers in New Orleans, Lake Charles, Lafayette and Houma, Louisiana. The second site visit was conducted in July 2013 and surveyed workers in the same locations as well as additional workers in Lake Jackson, Texas.

Worker Demographics

BSEE offshore oil-rig inspectors and engineers were tested and had a wide range of occupational backgrounds (i.e. engineering, industrial hygiene, oil-rig inspectors, production supervisors, and management). Workers were primarily men with ages between the early twenties to the mid-sixties. A total of seventy-five workers were tested during the 2012 field study and eighty-six were tested in 2013. Thirty-five workers were fit tested in both 2012 and 2013. Worker demographics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics of BSEE workers fit tested during the 2012 and 2013 field studies. (In 2012, one worker did not provide an age and in 2013, three workers did not provide their age.)

| 2012 | 2013 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Number | Percent | Age | Number | Percent |

| 20–29 | 13 | 17 | 20–29 | 21 | 24 |

| 30–39 | 18 | 24 | 30–39 | 19 | 22 |

| 40–49 | 15 | 20 | 40–49 | 16 | 19 |

| 50–59 | 21 | 28 | 50–59 | 20 | 23 |

| 60–69 | 7 | 9 | 60–69 | 7 | 8 |

| Gender | Gender | ||||

| Men | 73 | 97 | men | 82 | 95 |

| women | 2 | 3 | women | 4 | 5 |

| Total | 75 | 100 | Total | 86 | 100 |

Fit Testing Protocol and Hardware

In both field studies, Dell Latitude E6510 laptops with Windows 7 operating system were used to run HPD Well-Fit. The pulsed audio stimuli were generated by a high-definition audio card with 24-bit resolution and 44,100 Hz sampling rate. In 2012, stimuli were delivered through FitCheck circumaural headphones developed by Michael & Associates. In 2013, signals were delivered through Sennheiser HDA-200 circumaural audiometric headphones modified with extensions to increase the volume of the ear cup. The extension was a plastic ring that clips into the shell of the headphone and accommodates the foam cushion (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Headphones used with HPD Well-Fit. On the left are the modified Sennheiser HDA-200 headphones with spacers shown below. On the right are the Fit-Check headphones.

The modified Sennheiser HDA-200 headphones had a higher output level (better than 85 dB SPL at the octave band frequencies 125 to 8000 Hz) than the FitCheck headphones and had not been developed at the time of the 2012 survey. The FitCheck headphones were capable of producing at least 75 dB at all test frequencies between 125 and 8000 Hz. The larger volume of the ear cup and the less efficient TDH-39 headphone driver limited the output. The FitCheck headphone delivered 80 dB SPL noise bands at 500, 1000, and 2000 Hz, the frequencies used for testing single hearing protection devices in this study. The FitCheck headphones provided at least 25 dB attenuation at 500 1000 and 2000 Hz and the Sennheiser HDA200 headphones provided at least 15 dB attenuation (Schmitt et al., 2015). The combination of high-definition audio and the sound-isolating headphones yielded a dynamic range of about 85 dB.

The Dell computer provided a maximum 1.2 Volt RMS output signal. Five-second white noise samples were generated at 44,100 Hz and digitally filtered to create the one-third octave noise bands that were stored in memory while the application ran. The 250 ms duration noise bursts for the right and left channels were randomly sampled from within the longer five-second samples. In this manner, the noise band stimuli were not repeated and provide the ability to generate dichotic signals in real time for the subject being tested.

HPD Well-Fit provides a fit test of both ears simultaneously rather than each ear separately. The reported personal attenuation rating, or PAR, is analogous to an individual NRR, with the following distinctions:

The NRR is an average value based on results from several test subjects, whereas the PAR is an individual result.

The NRR is determined for hearing protectors fit by a trained experimenter, whereas the PAR is determined for hearing protectors fit by the user.

The NRR is determined in controlled laboratory conditions, whereas the PAR is generally determined in less-controlled field environments.

HPD Well-Fit calculates the PAR as an A-weighted attenuation, or the difference between an assumed A-weighted noise exposure and the estimated protected A-weighted noise exposure based on the noise reduction (difference between occluded and unoccluded thresholds), which the user received. The PAR is calculated as follows:

| (1) |

where LAf is the assumed A-weighted noise exposure level for each octave band where f is any of the standard octave band frequencies: 125, 250, 500, 1000, 2000, 4000, or 8000 Hz, Af is the individual’s attenuation measured at particular frequencies, and N is the number of frequencies used in the estimate. In this study, f = 500, 1000, and 2000 Hz. The PAR is intended to be subtracted from a worker’s noise exposure in order to estimate the protected noise exposure,

| (2) |

Testing Methodology

HPD Well-Fit software uses a method of adjustment paradigm to test 500, 1000, and 2000 Hz, in that order. Method of adjustment was chosen because this particular implementation allows a quick assessment of threshold and has built in reliability checks to control consistency and accuracy of the subject’s response. If the worker selected foam earplugs, they were shown how to roll an earplug and reach over the head to pull the pinna to straighten the ear canal. For premolded earplugs, the workers were instructed to pull the pinna when inserting the earplug. Between 2012 and 2013, the instructions for identifying hearing threshold were different.

In 2012, workers were instructed as follows:

“You will hear a series of pulsing sounds through the headphones. They will start at a comfortably loud level. Your task is to adjust the volume of the sounds until you can just barely hear them. Use the scroll wheel of the mouse to make the sounds louder or softer. When you have adjusted the level to the point where you can just barely hear it, click the scroll wheel to move onto the next sound. Do you have any questions?”

In 2013, the instructions were modified as shown below (changes in italics):

“You will hear a series of pulsing sounds through the headphones. They will start at a comfortably loud level. Use the scroll wheel of the mouse to make the sounds louder or softer. Scroll down until you can no longer hear the sounds, then slowly scroll up until you can just barely hear them. When you have adjusted the level to the point where you can just barely hear it, click the scroll wheel to move onto the next sound. Do you have any questions?”

The change in the instruction set was due to the different operators. In 2012, the first author, a physicist, operated the equipment and used the descending threshold technique. In 2013, the second author, an audiologist, used an ascending threshold technique. The instructions were changed to ascending to encourage the workers to listen more carefully to the stimulus before they identified a threshold. That is, in a descending method, the test subject may carelessly identify a threshold response.

HPD Well-Fit requires three consecutive threshold identifications with a range of less than 6 dB. Initially, the stimulus is set to 60 dB. The stimulus decreases in 2-dB and increases in 1-dB increments as the mouse wheel is scrolled. A dichotic signal with the one-third octave band noises isas presented to the subject at the same presentation level in each ear. After threshold was indicated by clicking any of the mouse buttons, the stimulus level is increased a random amount between 10 and 20 dB to start the next threshold identification at the same frequency. Once the consecutive threshold range requirement is met, the test advances to the next frequency and the stimulus level is increased to 60 dB.

Unoccluded testing (without earplugs) was accomplished first, followed by the occluded condition. When formable (e.g., foam) earplugs were tested, a two-minute waiting period preceded the occluded test in order to make certain the earplugs had fully expanded. In order to expedite the testing, the unoccluded condition was not repeated during retesting with a refit or new earplugs.

Test Environment

Fit testing was conducted in quiet, small offices or conference rooms. During 2012, background noise levels in the test room were continuously monitored using a Larson Davis Model 831 Type I sound level meter (ANSI S1.4–1983 (R2007)). One-third octave-band noise levels from 20 Hz to 16,000 Hz levels were averaged over one-second intervals and exported to an Excel data file. Noise monitoring was not conducted during the 2013 field studies.

Hearing Protectors Tested

Workers were initially evaluated with the protectors they usually wore: custom-molded protectors, pre-molded plugs, and formable plugs from several manufacturers. Field offices were asked to provide samples of the types of hearing protectors available at the site. The NIOSH and BSEE team also provided a variety of sample earplugs. If the worker failed to achieve a 25-dB PAR, then the fit-test process was repeated. The worker was reinstructed regarding how to properly prepare and fit the earplugs. If the second fitting failed to achieve a 25-dB PAR, then another earplug was selected and the fit testing was completed again. Workers were first tested with earplugs that were available at the field offices first and then with earplugs from the NIOSH and BSEE team. No particular brand was preferred or offered to the workers.

Results

Estimation of Worker Exposure Levels

The commute between the shore and the oil rigs via helicopter was between one and three hours. The Department of Interior had previously conducted a noise survey to document the daily time-weighted average (TWA) exposures and the maximum sound levels that were experienced aboard three commonly used helicopters (Radtke, 2007).

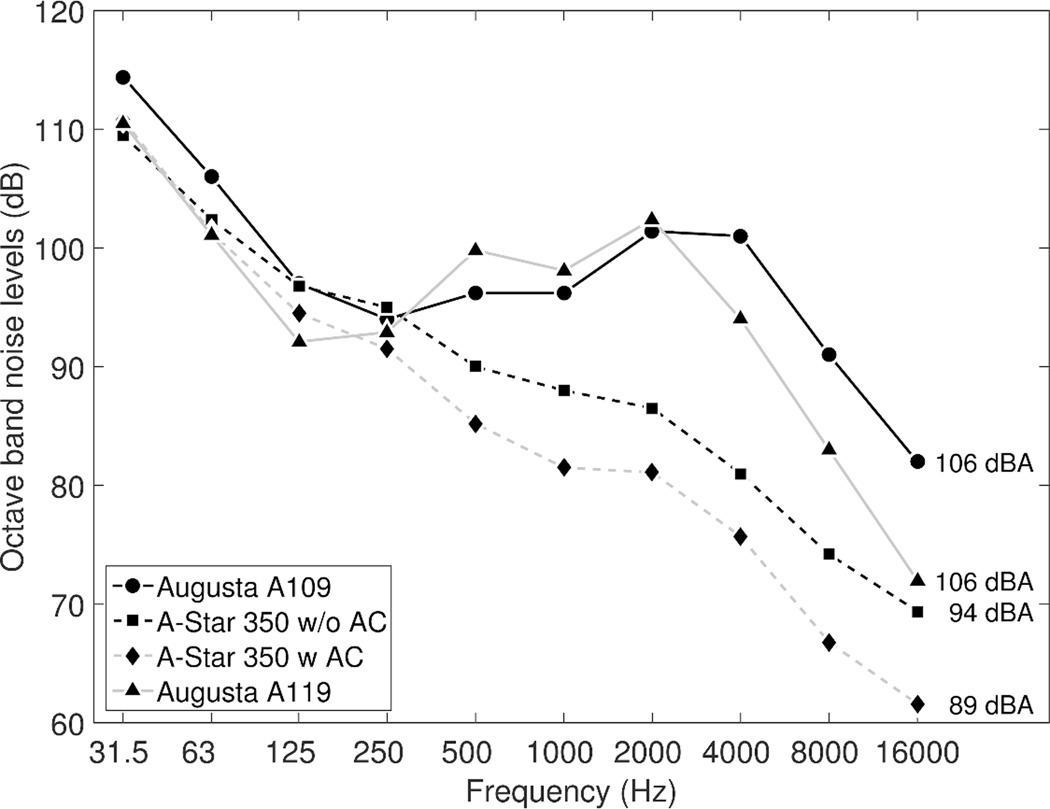

The noise levels in the cockpit position were between 87 and 98 dBA. Noise levels in the cabin were higher than those in the cockpit and ranged from 95 to 107 dBA. The motor was directly above the cabin and increased the workers’ exposure levels (Murphy et al., 2015b, Radtke, 2007). Figure 2 provides the octave band noise measures for three of the helicopters (one model measured with and without air conditioning on). The Augusta A109 helicopter had the highest noise levels across most frequency bands. Both the Augusta A109 and A119 helicopters exhibited substantially higher levels in the mid- and high frequencies (500 Hz and above) than the A-Star 350 – sometimes more than 20 dB higher. Using the air conditioning reduced the sound levels of the A-Star 350 helicopter at frequency bands above 63 Hz because the closed windows in this condition blocked some of the rotor and wind noise.

Figure 2.

Octave band noise levels in dB SPL for helicopters commonly used to transport BSEE inspectors to off-shore oil rigs.

All workers were assumed to have the worst-case noise exposure level of 110 dBA. In order to reduce the exposure level under the hearing protector to less than the NIOSH-recommended exposure level of 85 dBA, the target PAR was set at 25 dB. Although the A-weighted helicopter noise levels were below 110 dBA, a 25-dB PAR provides an additional safety factor when levels are high.

Fit-Test Results

Worker PARs

Figure 3 presents the PARs for each worker fit tested during the 2012 and 2013 field studies. In 2012, 127 fit tests were conducted on the seventy-five BSEE employees in Louisiana. Thirty workers (39%) did not achieve a 25-dB PAR on their initial fit test; these workers were retrained or refit with different hearing protectors and then retested, unless time did not permit. Among the workers who were initially tested with custom earplugs, six out of twenty-one workers achieved 25-dB PAR. The fifteen workers who were retested with a different earplug all were able to achieve the 25-dB PAR. Some workers were tested multiple times in order to identify a hearing protector that provided sufficient noise reduction. For most workers who were retrained or provided other earplugs, noticeable improvements in the PAR were observed. The filled circles symbols in Figure 3 represent a worker’s initial PAR and the open circle symbols indicate the final PAR. If only a filled symbol is shown for a worker, that individual was tested once – either because the initial PAR was adequate or because there was insufficient time to refit and retest.

Figure 3.

Initial and final personal attenuation ratings for BSEE workers in Louisiana and Texas fit tested in 2012 (upper graph) and 2013 (lower graph). Results are sorted by ascending initial PARs. If only one result is shown, the worker was not re-tested. See text for details on workers labeled a-d.

Sixty-eight of the seventy-five workers (89%) eventually achieved the target 25-dB PAR. Three workers with PARs below 25 dB were not retested because they needed to make their departure to the worksite or complete their shift. Four workers could not achieve the target 25-dB PAR in spite of retraining and refitting. Two workers achieved better results on their initial test compared to their final fit test; these were generally workers who wanted to try another earplug even though their current earplug was providing sufficient noise reduction. In these cases, the workers were advised to continue using their original earplugs.

In 2013, eighty-six workers were fit tested. Thirty-eight workers (44%) did not initially achieve a 25-dB PAR. Five of these workers could not be retested due to time constraints or because they did not want to try a different earplug. Twenty-five of the workers with low PARs eventually achieved the target PAR through retraining and/or refitting with different protectors. The remaining eight workers could not achieve the target attenuation even after retraining/refitting.

Ultimately, seventy-three of the eighty-six workers (85%) were able to achieve at least a 25-dB PAR. Several workers in 2013 wore custom-molded protectors that needed to be replaced; these workers did not achieve the target attenuation but wanted to have their custom plugs remade rather than switch to a disposable earplug. These workers were therefore not retested. Several other workers who could not achieve a 25-dB PAR with their disposable hearing protectors were referred for custom-molded protectors.

In 2013, four workers labeled A, B, C, and D had final PARs that were lower than their initial PARs (see lower panel of Figure 3). Workers A and B could not achieve 25 dB of noise reduction with any disposable earplug either provided by BSEE or NIOSH; custom plugs were recommended for these two workers. Worker C was initially tested with the foam earplugs he usually wore, but wanted to try flanged earplugs for comfort. He was unable to obtain sufficient attenuation with the flanged plug and was advised to continue using the foam protectors. Worker D was tested twice because he used one type of earplug when riding in the helicopter (displayed as initial PAR) and another type when working on the rig (displayed as final PAR). The 23-dB PAR for the second earplug was less than the target PAR for helicopter noise exposure but was sufficient for the noise levels on the oil rig.

Mean frequency-specific attenuations from 2012 and 2013 achieved by the workers are presented in Table 2 and medians and percentiles are summarized in Figure 4. These statistics include all of the fit-testing data – including multiple tests for some workers and regardless of whether or not the worker achieved the target PAR. Attenuations for the 500 Hz test bands were about 23 and 22 dB for 2012 and 2013, respectively. Attenuations for the 1000 and 2000 Hz test bands were similar between the two years at about 26 and 31 dB respectively.

Table 2.

Means and standard deviations in dB for the attenuations measured at 500, 1000, and 2000 Hz. The number of subject tests used to determine the mean and standard deviations were N = 127 from 2012 and N = 155 from 2013.

| Test Frequency (Hz) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 500 | 1000 | 2000 | |

| 2012 | |||

| Mean Attenuation (dB) | 23.4 | 25.9 | 31.3 |

| Standard Deviation (dB) | 12.1 | 10.6 | 10.0 |

| 2013 | |||

| Mean Attenuation (dB) | 21.9 | 25.3 | 31.6 |

| Standard Deviation (dB) | 10.8 | 10.2 | 10.0 |

Figure 4.

Fit-test results from the two field studies by frequency. The median, 25th and 75th quartiles are depicted with the box. The error bars indicate 5th and 95th percentiles. The data points outside the error bars have been shifted right and left with a random amount of jitter to facilitate visualization. The 2012 Louisiana attenuation data are displayed in the left panel and the 2013 Louisiana and Texas data are displayed in the right panel.

In Figure 4, several of the outlier attenuations indicate that workers achieved attenuation less than about 4 dB. In some cases, the worker did not understand the instructions for finding threshold and the occluded thresholds were less than the unoccluded thresholds. In other cases, test-retest variability of about 2 to 4 dB coupled with poorly-fit hearing protectors could explain the negative attenuations. Poorly-fit earplugs can enhance the stimulus signal and result in negative attenuations as well. From an inter-laboratory study that NIOSH conducted assessing the performance of HPD Well-Fit, a range of ±2 dB can be expected for the repeatability of a threshold assessment (Byrne et al. 2016). Regardless of the cause, workers with obviously low attenuations were reinstructed and retested.

Thirty-five workers were tested during both the 2012 and 2013 surveys in Louisiana. Three of the workers did not achieve the 25 dB PAR in 2012 and thirty-two workers did. In 2013, seventeen workers achieved a PAR above 25 dB and the remaining eighteen workers did not. One of the three workers who failed to achieve a 25 dB PAR in 2012 achieved an adequate PAR in 2013 while the other two workers’ PARs were less than the target protection level in both 2012 and 2013. The majority of workers were able to fit their hearing protection correctly when NIOSH first tested them in 2012; however, four workers who had not obtained the target PAR at their initial 2012 test and had been retrained and achieved the 25-dB PAR were shown to have maintained that target at the initial 2013 test. This illustrates the potential power of individual fit testing. If the workers maintain the target PAR level, they have demonstrated that they have been adequately trained. Perhaps longer intervals between subsequent fit tests could be accepted. However, workers who do not maintain the target PAR level over time need repeated fit-testing to ensure that they remain adequately protected. Periodic fit testing should become a routine part of every hearing loss prevention program. Workers’ attenuations may change with time due to changes in an individual’s ear, how the worker fits the device, or deterioration of custom and premolded earplugs.

Test Times

The time required to conduct fit testing is an important factor for implementation in workplaces (Murphy et al., 2007; Berger et al., 2011). Since HPD Well-Fit tracked the start and stop times for each threshold identification, the testing and training times can be examined in detail..

The total test time includes both the time for the worker to determine hearing threshold levels at each frequency and the training time. Table 3 summarizes the threshold timing data for the 2012 and 2013 field studies. As workers progressed from the unoccluded to the occluded testing, the threshold test times generally decreased for each successive frequency. This finding is consistent with well-documented learning effects associated with clinical audiometric threshold testing (Roche et al., 1983; Royster and Royster, 1986). The same trend was observed in both years, but test times in 2013 were somewhat longer than in 2012. The increased threshold testing time may be attributed to a change in the subject instructions from the one-step process of just “scrolling down” until the signal was barely audible to the two-step process of “scrolling down” until the signal disappeared and then “scrolling back up” until the signal was just barely audible. The ascending part of the test required the workers to listen for the reappearance of the pulsed noise band. A descending test can lead to a bit of carelessness by adjusting the sound to the point where it can’t be heard.

Table 3.

Minimum, median, maximum, and mean (with 95% confidence interval) threshold test times (in minutes) for each segment of the HPD Well-Fit procedure during the 2012 and 2013 field studies. The statistics for each frequency were determined from 127 tests of 75 persons in 2012 and 155 tests of 86 persons in 2013.

| Year | Frequency (Hz) |

Condition | Times (in minutes:seconds) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Median | Max | Mean [95% CI] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2012 | 500 | Unoccluded | 0:14 | 0:37 | 1:46 | 0:43 [0:40, 0:47] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1000 | Unoccluded | 0:15 | 0:30 | 1:23 | 0:33 [0:31, 0:35] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2000 | Unoccluded | 0:10 | 0:26 | 1:21 | 0:29 [0:26, 0:31] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 500 | Occluded | 0:04 | 0:23 | 1:19 | 0:25 [0:23, 0:27] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1000 | Occluded | 0:05 | 0:21 | 0:50 | 0:22 [0:20, 0:23] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2000 | Occluded | 0:06 | 0:21 | 1:26 | 0:23 [0:22, 0:25] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2013 | 500 | Unoccluded | 0:24 | 0:56 | 3:06 | 1:02 [0:58, 1:07] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1000 | Unoccluded | 0:19 | 0:43 | 2:07 | 0:52 [0:47, 0:55] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2000 | Unoccluded | 0:14 | 0:41 | 1:41 | 0:45 [0:43, 0:47] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 500 | Occluded | 0:13 | 0:38 | 1:59 | 0:41 [0:38, 0:44] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1000 | Occluded | 0:09 | 0:37 | 2:18 | 0:41 [0:38, 0:44] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2000 | Occluded | 0:12 | 0:36 | 2:19 | 0:40 [0:37, 0:43] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 4 summarizes the amount the mean training and the total times for each year’s survey. The training time was calculated as the interval between the end of the unoccluded test and the start of the last sequence of occluded tests. Thus, if a worker required more than one earplug fitting, the threshold testing time for those fits are lumped into the estimates of training time. This approach reflects the time required to instruct, test occluded fit, reinstruct the worker. The total test time was determined from the start of the first unoccluded test and the end of the last occluded test.

Table 4.

HPD Well-Fit Training and Total Times 2012 and 2013. The minimum, median, maximum, average, upper and lower limits of the two-sided 95% confidence intervals (CI) are indicated in minutes.

| Year | Condition | Time (in minutes:seconds) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | Median | Maximum | Mean | 95% C.I of Mean | ||

| 2012 | Training | 0:24 | 2:48 | 30:42 | 4:36 | [3:42, 5:30] |

| 2012 | Total Time | 2:00 | 6:06 | 33:18 | 7:36 | [6:42, 8:30] |

| 2013 | Training | 0:12 | 3:06 | 27:06 | 6:06 | [5:12, 7:00] |

| 2013 | Total Time | 3:30 | 8:42 | 32:48 | 10:42 | [9:48, 11:36] |

The amount of time ranged from 3 to approximately 7 minutes for the training time and the total time ranged from 6 to almost 12 minutes for the 95% confidence interval. At the outside the longest time was about 33 minutes that included four attempts to fit a protector. Both the training and total testing times increased between 2012 and 2013. This difference has been attributed to the instructions that were being provided by the personnel conducting the testing.

Background Noise Levels during Testing

In 2012, the noise levels in the testing areas were measured simultaneously with the fit testing in the four locations in Louisiana. Noise levels were not sampled in 2013. High background noise levels could mask the detection of the pulsing noise band when the subject was tested in the unoccluded condition. The cumulative distributions were determined for the overall levels and the frequency bands for each location where subjects were tested. The maximum permissible ambient noise levels for the ears uncovered (ANSI/ASA S3.1, 2013) and the attenuations of the headphones were used to estimate the permissible background noise level. The cumulative distributions and the permissible background noise levels are plotted in Figure 5. For each location, the lower levels of the cumulative distribution extend into the shaded portion of the plot indicating that the background noise levels were acceptable. In the New Orleans location, several workers were in the room while testing was being conducted. Talking and general restlessness may have skewed the noise levels at 500 Hz.

Figure 5.

Cumulative distributions of overall and third-octave band ambient noise levels at each 2012 field study sites. The shaded area indicates the maximum level at which thresholds can be measured to audiometric zero, assuming a test range of 500 to 8000 Hz and taking into account the additional attenuation provided by the HPD Well-Fit headphones.

High background noise levels can elevate the unoccluded threshold in workers with thresholds near audiometric zero, thus reducing the difference between the unoccluded and occluded conditions and the PAR. While testing in quieter environments is more accurate and preferred, PARs measured in a higher background noise level will underestimate the protection the worker receives and overestimate the exposure the worker might receive. If the worker was tested in low background noise conditions, the same earplugs would provide adequate protection. In addition, the NIOSH HPD Well-Fit™ test paradigm works around high background noise issues by allowing the subject to pause and “listen around” distractions without incurring any penalty for assessing hearing threshold.

Discussion

BSEE oil-rig inspectors are occupationally exposed to high noise levels (up to 110 dBA), particularly during helicopter transport to and from the offshore rigs. Effective hearing protection is essential to preserving auditory function in these workers. Because earplug fit is highly variable, the NRR for any device has little predictive value for estimating an individual’s attenuation and related exposure level (see Figure 2). Individual fit testing is the only way to know whether a worker can achieve the necessary attenuation level with a particular protector. Fit testing is especially critical when noise levels are high and more than just 10 or 15-dB attenuation is required to have protected levels below 85 dBA (e.g. exposures above 100 dBA). As well, the spectrum of the noise affects the performance of hearing protection. Lower protection levels are realized when worn in low-frequency noise for earmuffs in general and for earplugs that are not well fit (Murphy et al., 2004; Gauger and Berger 2004; Joseph et al., 2007).

Training

NIOSH conducted hearing protector fit tests of seventy-six workers in 2012 and eighty-six workers in 2013. More than forty percent of the workers were not achieving adequate attenuation from their hearing protectors. Through training and re-fitting, workers were able achieve the appropriate amount of noise reduction; recommendations for other hearing protection options were made for those workers who could not be properly fit with available protection during the site visit. The results of training in proper wearing and fitting techniques were not always persistent. Only about half of the workers tested in 2012 and 2013 maintained the target attenuation level of 25 dB. Other workers who had been trained and achieved the target PAR in 2012 exhibited a low attenuation on the first test in 2013. Stephenson et al. (2011) demonstrated that an important element to an effective hearing conservation program is self-efficacy. When workers possess the confidence that they can fit personal protective equipment properly, they are more likely to use it. The lack of retention of good fits between 2012 and 2013 may suggest that some workers could benefit from fit testing more often than once a year. Self-efficacy alone doesn’t ensure that workers will comply. Positive encouragement for those workers who have attained the 25 dB PAR and training in proper insertion methods for those who failed to attain the target PAR should help workers to remember the importance of wearing hearing protection consistently and correctly.

Test Times

The field studies provided valuable information on implementing hearing protector fit testing in the workplace and feedback on the utility of the HPD Well-Fit system specifically. The majority of the workers required between 7 and 12 minutes to complete the fit test and training. The time to establish thresholds was reduced as successive frequencies were tested (see Table 4). As more workplaces implement hearing protection fit testing in their hearing conservation programs and as workers learn to correctly fit protectors, the total testing times should decrease. An efficient fit-test system will minimize the disruption to productivity and improve the ability of workers to be cognizant about the hazards of noise exposure. Although an employer could estimate the time required for fit testing, the time to transit from the worker’s station to the test location is unknown. Additional delays at the testing station can reduce worker productivity.

Test instructions affect threshold test times and therefore affect training (which includes occluded retest threshold test times) and total test time. Average training and total test time differed between 2012 and 2013 due to changes in testing instructions. The total time for fit testing was between about 7 and 12 minutes and the time devoted to training ranged from approximately 4 to 7 minutes. At the outside, the longest fit-test time was about 30 minutes, which included four attempts to fit a protector. Small differences in attenuation at 500 Hz were noted between the two test years, although it is unclear if this was related to instructions, background noise levels or simply normal variability.

Other fit-test systems that use a microphone in real-ear (MIRE) method such as Phonak’s SafetyMeter and 3M’s EARfit Validation System require a few minutes to allow foam earplugs to fully expand and several seconds to make the measurement. The decreased testing time and lack of subject involvement beyond fitting the protector are major differences between these systems and threshold or loudness balance based systems. These MIRE systems are vendor specific, however. SafetyMeter tests only the Phonak Serenity custom earplugs. EARfit can only be used with 3M, Peltor, and EAR surrogate ear tips that have specially-adapted probe tubes through the body of the ear tip, which serve as surrogates for the actual earplug or earmuff.

The VeriPRO fit-test system requires about 15 minutes to conduct a fit test for five frequencies 250 to 4000 Hz (Trompette and Kusy, 2013). Repeated fit tests with VeriPRO yield no time-savings because the paradigm requires all of the steps to be conducted. HPD Well-Fit requires only an additional two minutes when repeated fittings are required to train workers. The FitCheck system, depending upon its configuration, required a minimum of 7 minutes to complete thresholds in each ear (Murphy et al., 2007). In order to complete multiple fitting, the entire test procedure also had to be repeated. In the NIOSH field study with General Motors, the FitCheck system was configured to test four subjects simultaneously and allowed 30 seconds for a threshold determination at each frequency (Murphy et al., 2007). In the single-user configuration of FitCheck, the software required a level of consistency in the subject’s response that could extend the test or even fail to produce a valid result.

Background Noise

Background noise issues did not present a significant problem in this study. Although noise levels exceeded the ANSI S3.1 standard for testing to audiometric zero, the fit-testing procedure is based on threshold differences rather than actual thresholds and the subjects wore noise-attenuating headphones. The dynamic range of the HPD Well-Fit system made it possible to test in standard office or conference room space. Rooms were quieter when employees waiting to be tested remained outside. Conversations among waiting employees can be distracting. Fit-testing using REAT under headphones should be conducted in a space with minimal background noise and with few auditory distractions (e.g. other persons in the room, noisy hallways, and excessive ventilation noise).

Recommendations for BSEE oil-rig inspectors

Because workers experience high noise levels during transit to and from the offshore platforms, the hearing protector fit-testing program should be maintained. Workers should be able to demonstrate a 25-dB PAR and need to be educated regarding the hazard of excessive exposure to noise levels above the 85 dBA recommended exposure limit. Helmets worn during the helicopter rides do provide a limited amount of attenuation, but without attenuation data for the actual workers, earplugs are recommended.

For persons who must maintain communication with the pilots, a communication system that is integral to the helmet is recommended. Several companies have developed helmet systems that are approved for flight operation with the US Department of Defense and Coast Guard. The advantage of the communication system is a reduced burden to transmit an intelligible signal in the presence of high levels of noise. Some of the more advanced systems can pick up speech in the ear canal or through a bone conduction or throat microphone, further improving the signal-to-noise ratio.

Active noise cancellation headsets could provide additional benefit for the oil-rig inspectors. The noise spectrum for the helicopters has significant low frequency components. Active noise cancellation systems can provide as much as 20 dB of additional attenuation (Murphy et al. 2015a). These systems typically have higher signal to noise ratios that will, in turn, improve communications between personnel on the helicopters while preventing long-term noise induced hearing loss. While several manufacturers sell active noise cancellation headsets, none of the available fit-test systems can test active noise cancellation systems.

Conclusions

This field study highlighted the most important reasons for incorporating fit testing into hearing loss prevention programs. The primary role of the hearing conservationist is to prevent noise-induced hearing loss. Knowing worker exposures and ensuring that the noise levels are reduced to safe levels are the key to mitigating occupational noise-induced hearing loss. When relying on hearing protection devices to reduce exposure, individual fit testing is the only way to confirm that workers are sufficiently protected. This is especially true for very high exposures such as those experienced by the BSEE oil-rig inspectors.

The OSHA Hearing Conservation Amendment mandates educating noise-exposed workers about the hazards of noise induced hearing loss (OSHA, 1983). The interaction between the tester and the worker during fit testing provides a natural opportunity to educate the worker in selection, proper use and fitting of hearing protection. In fact, the OSHA-NHCA-NIOSH Alliance Best Practice Bulletin identified individual fit testing as an emerging trend and best practice (OSHA, 2008).

Selection of suitable protection requires knowledge of the worker’s noise exposure. A limited selection of hearing protection devices for the workers could be a barrier to effective hearing loss prevention programs. In these cases, fit testing identifies whether the worker can correctly wear the protection that is available. If the available protectors do not provide adequate attenuation, fit testing documents PAR performance and provides justification for alternative protection solutions.

Finally, workers’ fit-testing times using the NIOSH HPD Well-Fit™ system were typically between 6 and 12 minutes. Workers learned proper insertion techniques for earplugs, but proficiency was not necessarily maintained between successive tests. Proactive hearing conservation professionals will incorporate fit testing into hearing loss prevention programs because it is the best means to educate and train workers to take an active part in protecting their hearing from noise-induced hearing loss.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Roey Holliday and Rose Capers-Webb from the Bureau of Safety & Environmental Enforcement/US Department of the Interior for their assistance on the field studies and data collection.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not represent any official policy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Mention of company names and products does not constitute endorsement by the CDC or NIOSH.

References

- 1.ANSI. ANSI/ASA S3.1-1999 (R2013), Maximum Permissible Ambient Noise Levels for Audiometric Test Rooms. New York: American National Standards Institute; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.ANSI. ANSI/ASA S1.4-1983 (R2007), Specification for Sound Level Meters. New York: American National Standards Institute; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berger EH, Franks JR, Behar A, Casali JG, Dixon-Ernst C, Kieper RW, et al. Development of a new standard laboratory protocol for estimating the field attenuation of hearing protection devices. Part III. The validity of using subject-fit data. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1998;103(2):665–672. doi: 10.1121/1.423236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berger E, Le Cocq C, Kieper R, Voix J. Development and validation of a field microphone-in-real-ear approach for measuring hearing protector attenuation. Noise and Health. 2011;13(51):163. doi: 10.4103/1463-1741.77214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byrne DC, Murphy WJ, Krieg ER, Ghent RM, Michael KL, Stefanson EW, Ahroon WA. Inter-laboratory comparison of three fit-test systems. (accepted for publication) J. Occ. Env. Hyg. 2016 doi: 10.1080/15459624.2016.1250002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edwards RG, Hauser WP, Moiseev NA, Broderson AB, Green WW. Effectiveness of earplugs as worn in the workplace. Sound Vib. 1978;12:12–30. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edwards RG, Broderson AB, Green WW, Lempert BL. A second study of the effectiveness of earplugs as worn in the workplace. Noise Control Eng J. 1983;20:6–15. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards RG, Green WW. Effect of an improved hearing conservation program on earplug performance in the workplace. Noise Control Eng J. 1987;28:55–65. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Environmental Protection Agency. Code of Federal Regulations 40 CFR 211 Subpart B Labeling Hearing Protection Devices. Federal Register. 1978;44(190):56130–56147. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franks JR, Murphy WJ, Johnson JL, Harris DA. Four earplugs in search of a rating system. Ear Hear. 2000;21:218–226. doi: 10.1097/00003446-200006000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franks JR, Murphy WJ, Harris DA, Johnson JL, Shaw PB. Alternative Field Methods for Measuring Hearing Protector Performance. AIHA Journal. 2003;64:501–509. doi: 10.1202/309.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gauger D, Berger EH. A New Hearing Protector Rating: The Noise Reduction Statistic for Use with A Weighting (NRSA) E-A-R Technical Report. 2004:1–78. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heyer NJ, Morata TC, Pinkerton LE, Brueck SE, Stancescu D, Panaccio MP, et al. Use of historical data and a novel metric in the evaluation of the effectiveness of hearing conservation program components. Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2010:1–8. doi: 10.1136/oem.2009.053801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joseph AR, Punch J, Stephenson MR, Paneth N, Wolfe E, Murphy WJ. The effects of training format on earplug performance. International Journal of Audiology. 2007;46(10):609–618. doi: 10.1080/14992020701438805. http://doi.org/10.1080/14992020701438805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Masterson EA, Deddens JA, Themann CL, Bertke S, Calvert GM. Trends in worker hearing loss by industry sector, 1981–2010. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2015;58:392–401. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Masterson EA, Bushnell PT, Themann CL, Thais C, Morata TC. Hearing Impairment Among Noise-Exposed Workers – United States, 2003–2012. MMWR, Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:389–394. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6515a2. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6515a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Michael PL, Kerlin RL, Bienvenue GR, Prout JH, Shampan JI. A Real-Ear Field Method for the Measurement of the Noise Attenuation of Insert-type Hearing Protectors. DHEW (NIOSH) Publication No. 1976;76–181:1–168. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michael K, Bloyer C. Hearing protector attenuation measurement on the end-user; Presentation at the National Hearing Conservation Association Meeting; Atlanta GA. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murphy WJ, Franks JR, Berger EH, Behar A, Casali JG, Dixon-Ernst C, et al. Development of a new standard laboratory protocol for estimation of the field attenuation of hearing protection devices: Sample size necessary to provide acceptable reproducibility. J Acoust Soc Am. 2004;115(1):331–323. doi: 10.1121/1.1633559. http://doi.org/10.1121/1.1633559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murphy WJ, Davis RR, Byrne DC, Franks JR. Advanced hearing Protector Study, NIOSH EPHB Report No. 312–11a. Cincinnati, OH: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murphy WJ. Comparing Personal Attenuation Ratings for Hearing Protector Fit-test systems. Council for Accreditation of Occupational Hearing Conservationists. 2013;25(3):1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murphy WJ, Jerome TW, Gallagher HL, Theis MA, McKinley RL. “Comparison of Three Noise Reduction Rating Calculators for Passive and Active Hearing Protection Devices. NIOSH EPHB Report No. 360–13a. Cincinnati, OH: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. 2015a [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murphy WJ, Themann CL, Murata TK. “Field Testing NIOSH HPD Well-Fit: Off-Shore Oil Rig Inspectors in Texas and Louisiana.” NIOSH EPHB Report No. 360–11a. Cincinnati, OH: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. 2015b [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nelson DI, Nelson RY, Concha-Barrientos M, Fingerhut M. The global burden of occupational noise-induced hearing loss. Am J Ind Med. 2005;48:446–458. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.NIOSH. Criteria for a recommended standard: occupational noise exposure; revised criteria. Cincinnati, OH: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 1998:98–126. [Google Scholar]

- 26.OSHA. CPL 2–2.35A-29CFR 1910.95(b)(1) Guidelines for noise enforcement: Appendix A, US Department of Labor. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. 1983 Dec 19;:1983. [Google Scholar]

- 27.OSHA. [Accessed 12/10/2013];OSHA/NHCA/NIOSH Alliance, Best Practice Bulletin: Hearing Protection-Emerging Trends: Individual Fit Testing. 2008 www.hearingconservation.org.

- 28.OSHA. [accessed, June 2, 2016];Methods for Estimating HPD Attenuation, Noise and Hearing Conservation Appendix IV: part C. 2016 https://www.osha.gov/dts/osta/otm/noise/hcp/attenuation_estimation.html.

- 29.Radtke T. Noise Exposure Survey, US Dept. Interior, Minerals Management Service, New Orleans Region. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roche AF, Mukherjee D, Chumlea WC, Champney TF. Examination effects in audiometric testing of children. Scand Audiol. 1983;12(4):251–256. doi: 10.3109/01050398309044428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Royster JD, Royster LH. Using audiometric data base analysis. J Occup Med. 1986;28:1055–68. doi: 10.1097/00043764-198610000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schmitt L, Murphy WJ, Byrne DC. Attenuation Comparison of Headphones; Poster presentation at the 40th meeting of National Hearing Conservation Association; Feb 20, 2015; New Orleans. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schulz TY. Individual fit-testing of earplugs: A review of uses. Noise and Health. 2011;13(51):152. doi: 10.4103/1463-1741.77216. http://doi.org/10.4103/1463-1741.77216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stephenson MR, Shaw PB, Stephenson CM, Graydon PS. Hearing loss prevention for carpenters: part 2 - demonstration projects using individualized and group training. Noise and Health. 2011;13:122–131. doi: 10.4103/1463-1741.77213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tak S, Calvert GM. Hearing Difficulty Attributable to Employment by Industry and Occupation: An Analysis of the National Health Interview Survey—United States, 1997 to 2003. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2008;50(1):46–56. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181579316. http://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181579316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Themann CL, Suter AH, Stephenson MR. National Research Agenda for the Prevention of Occupational Hearing Loss - Part 2: Hearing Protection Devices. Seminars in Hearing. 2013;34(3):208–251. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trompette N, Kusy A. Suitability of Commercially Available Systems for Individual Fit Tests of Hearing Protectors; Proceedings of Inter-Noise; Innsbruck Austria. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Voix J. Development of a “Smart” Earplug. Ph.D. Dissertation. L’ecole de Technologie Superieure. 2006:1–249. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Voix J, Laville F. Prediction of the attenuation of a filtered custom earplug. Applied Acoustics. 2009;70(7):935–944. [Google Scholar]