The Mid-South Transdisciplinary Collaborative Center (TCC) for Health Disparities Research (U54MD008176) was funded in 2012 by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities to conduct research on the social determinants that produce disparate health outcomes in vulnerable populations. The goal of this work is to identify pathways and mechanisms through which social, economic, cultural, and environmental factors drive and sustain health disparities in obesity and related chronic diseases across the lifespan.

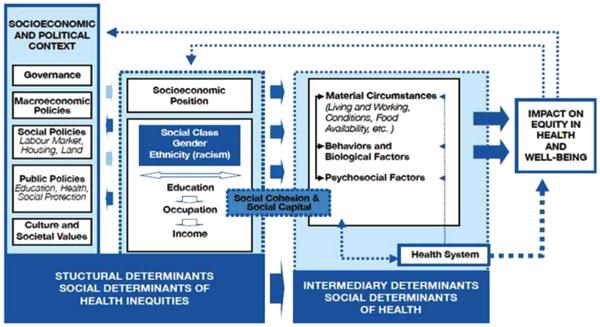

Traditionally, biomedical research has focused on physiologic processes that impact health, with occasional emphasis on behavioral and demographic factors. The Mid-South TCC has adopted a conceptual framework that considers the social context in which people are born and live, as this context impacts both the physiologic processes and behaviors of individuals (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Conceptual framework adopted by the Mid-South Transdisciplinary Collaborative Center (TCC).

Source: Solar O, Irwin A. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Social Determinants of Health Discussion Paper 2 (Policy and Practice). Geneva: WHO, 2010.1

Moreover, the Center promotes an integrative approach that accounts for multiple simultaneous contributors to disease etiology, including fundamental social factors as well as biological and behavioral factors. Mid-South TCC investigators work across domains (biological, behavioral, environmental, sociocultural, and health system) and levels of influence (individual, interpersonal, community, systems, societal) and collaborate with stakeholders from multiple sectors. The Center bridges biomedical and psychosocial research in a translational effort to place biological and behavioral mechanisms in a social context, with the ultimate goal of identifying key intervention points effective in specific populations.

This integrative approach is evident in the multidisciplinary nature of the investigative team, which represents 18 disciplines (e.g., genetics, exercise physiology, nutrition, bioinformatics, epidemiology, psychology, medical sociology, and urban planning) across five branches of science: natural, physical, formal, social, and applied. Such diversity in scientific perspectives and methodologies is critical for successful integration of biomedical, social, and behavioral sciences to generate high-impact health disparities research.

In addressing the social determinants that drive and sustain the disparities in obesity and chronic disease, the Mid-South TCC has adopted a life-course approach, focusing on critical periods in a person’s life trajectory, such as the prenatal period, infancy, adolescence, and advanced age, when the social context may be most salient in impacting physiology or shaping health behavior.

Two research projects, funded for the full 5-year duration of the consortium, involve collection of original data and participation of investigators from multiple academic institutions. Consistent with the life-course perspective, these studies address obesity, a risk factor for chronic diseases, during two critical time points—in utero/pregnancy and during adolescence:

“Examining the Influence of Social Determinants of Health on Gestational Weight Gain and Maternal and Child Outcomes among Black and White Women in the Deep South”; and

“Molecular and Social Determinants in Obesity and Metabolic Disorders Among Developing Youth.”

Smaller projects of 1 or 2 years duration are funded as well, through a competitive peer-review process similar to the one used by NIH. These pilot studies examine the interplay between social determinants of health (SDH) and biological processes that results in disparate health outcomes (e.g., “Metabolic and Social Determinants of Racial Disparity in Hemoglobin Glycation”) or the complex interaction among SDH, physiology, and behavior (e.g., “Adverse Effects of Life Stress on Obesity and Disease Risk, Mediated by Diet and Oxidative Stress” and “Behavioral and Social Factors Impact Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Obesity in HIV-Infected Women”). Other studies are focused on assessing SDH in specific populations, which also generates data resources to be used in future research (e.g., “Assessing the Social Determinants of Obesity for Latino Immigrants” and “Monitoring Social Determinants of Obesity Outcomes in a Community Clinic”). A group of projects explore the use of technology to reduce obesity or disparities in chronic diseases (e.g., “Kid Koders for Health: Promoting Physical Activity among Underserved Youth,” “Bikeshare for Low-Income Urban Communities: A Mixed Methods Feasibility Study,” and “Mobile Mindfulness Training to Reduce Chronic Health Disparities in Louisiana Women”). Finally, some projects test community-based interventions in the thematic area of the Center (e.g., “A Family-Based Intervention to Reduce Obesity in the Black Belt” and “Healthy Roots for You: A Social Marketing Campaign to Increase Fruit and Vegetable Purchases”). Studies using data from existing national cohorts and cohorts established by the participating institutions also are supported. Examples of funded concepts are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Concepts for Secondary Data Analysis Funded by the Mid-South TCC

| Concept title | Data source |

|---|---|

| Investigating the Relationship between Perceived Discrimination and Obesity Among African Americans in Mississippi |

Jackson Heart Study |

| The Role of Behavioral, Family, and Community Effects on Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Comorbidity in Obesity, Chronic Kidney Disease, Diabetes, Hypertension, and All-cause Mortality |

NHIS, NHANES |

| Exploring Social and Lifestyle Factors in Minority Aging: Obesity, Perceived Discrimination, and Chronic Systemic Inflammation |

MIDUS |

| A Comparison of Black and White Racial Differences in Health Lifestyles and Cardiovascular Disease | CARDIA |

| Association of Food Environment and Mediterranean Diet Adherence and Obesity in the U.S.: A Geographic Information System Analysis |

REGARDS |

| Segregation and the Disparities in the Built Environment | SDH Core Database |

| Social Determinants of Long-term Maintenance of Physical Activity and its Relationship to Weight Change | Jackson Heart Study |

| Social-ecological Stressors, Obesity-risk and Racial Disparities in Obesity: A Longitudinal Study | NLSY97 |

| Examining Associations between Social Determinants of Health, Obesity and Comorbid Conditions, and Longitudinal Outcomes Among Older African American and Caucasian Medicare Beneficiaries |

Jackson Heart Study |

| The Association Between Job-related Factors and Ideal Cardiovascular Health among African Americans with and without Diabetes |

Jackson Heart Study |

CARDIA, Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study; MIDUS, Midlife in the United States: A National Longitudinal Study of Health and Well-Being; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; NHIS, National Health Interview Survey; NLSY97, National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997; REGARDS, Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke Study; SDH, social determinants of health; TCC, Collaborative Center.

Although the Mid-South TCC includes programs and cores that are traditional for large research enterprises, such as Administrative Core, Research and Pilot Projects Program, Biostatistics and Study Design Core, Academic–Community Engagement Core, and Dissemination Core, one of its most unique features is the SDH Measurement Core (SDH Core), which provides theoretical and methodological expertise, measurement tools, and data products related to SDH. Measuring SDH constitutes a methodological challenge. Additionally, understanding the etiology of multifactorial conditions, such as obesity and chronic disease, calls for the use of multidisciplinary scientific methods and instruments. To help investigators overcome these challenges, the SDH Core has established a resource bank with relevant publications; a toolkit with validated scales, indices, instruments, and supporting documentation related to specific SDH; a list of secondary data sources for SDH research; a database with region-specific SDH and health outcomes data; and a GIS mapping resource. Examples of measures in the toolkit include indicators of SES (income, education, occupation), income inequality, work opportunities, material well-being, deprivation, food security, food habits and nutrition, exercise, stress, depression, hostility, environmental exposures (toxins, pollution), built environment, neighborhood living conditions (concentrated disadvantage, residential segregation, physical safety, walkability, housing conditions, infrastructural decay, recreational environment, nutritional environment), segregation, discrimination, social capital, social cohesion, social exclusion, social support, civic engagement, and collective efficacy. Additionally, the SDH Core has developed standardized sociodemographic questions and measures that are used across all TCC projects to collect uniform data on race/ethnicity, sex, age, education, employment status, household income, health insurance status, marital status, and household size. The SDH Core thus provides one-stop access to a wealth of tools and expertise to support research on the SDH. Its resources are also available to investigators interested in including measures of SDH in their future research, which increases the SDH Core’s long-term impact on advancing knowledge.

The Mid-South TCC has served as an enabling platform for team science that addresses a complex problem— health disparities—through a complex systems approach that involves collaboration between investigators from diverse scientific backgrounds. Some research findings have already been published2–7; the papers presented here add to this body of knowledge. For example, one article examines the relationship between street connectivity and obesity risk as evidenced by data obtained from electronic health records.8 Linking electronic health records with SDH and environmental measures could further understanding of the etiology of obesity and chronic disease and suggest feasible strategies for addressing the disparities in these conditions. Another article examines the association between perceived discrimination and obesity among African Americans, clarifying the role of perceived stress and health behaviors.9 The authors report that health behaviors lead to suppression, rather than mediation, between perceived discrimination and weight status and between stress and weight status. Yet another article clarifies the contributions of race, income, education, and perceived discrimination to systemic inflammation measured by four biomarkers.10 The findings suggest that inflammation-reducing interventions should focus on African Americans and individuals facing socioeconomic disadvantages, especially low education. These are just a few examples of the Mid-South TCC’s focus on identifying some of the root causes of disparities in obesity and chronic diseases. The results from this work should be used to inform approaches to health care, public health, and policy that affect the health and well-being of all.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Publication of this article was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (U54MD008176). The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

This article is part of a supplement issue titled Social Determinants of Health: An Approach to Health Disparities Research.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Solar O, Irwin A. Social Determinants of Health Discussion Paper 2 (Policy and Practice) WHO; Geneva: 2010. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kepper M, Tseng TS, Volaufova J, et al. Pre-school obesity is inversely associated with vegetable intake, grocery stores and outdoor play. Pediatr Obes. 2016;11(5):e6–e8. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12058. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/ijpo.12058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cherrington AL, Willig AL, Agne AA, et al. Development of a theory-based, peer support intervention to promote weight loss among Latina immigrants. BMC Obes. 2015;2:17. doi: 10.1186/s40608-015-0047-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s40608-015-0047-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coulon SJ, Velasco-Gonzalez C, Scribner R, et al. Racial differences in neighborhood disadvantage, inflammation and metabolic control in black and white pediatric type 1 diabetes patients. Pediatr Diabetes. doi: 10.1111/pedi.12361. In press. Online January 18, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/pedi.12361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Kepper M, Sothern M, Zabaleta J, et al. Prepubertal children exposed to concentrated disadvantage: an exploratory analysis of inflammation and metabolic dysfunction. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2016;24(5):1148–1153. doi: 10.1002/oby.21462. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/oby.21462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamdan MA, Hempe JM, Velasco-Gonzalez C, et al. Differences in red blood cell indices do not explain racial disparity in hemoglobin A1c in children with type 1 diabetes. J Pediatr. 2016;176:197–199. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.03.068. http://dx. doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.03.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoshida YX, Simonsen N, Chen L, et al. Sociodemographic factors, acculturation, and nutrition management among Hispanic American adults with self-reported diabetes. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2016;27(3):1592–1607. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2016.0112. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/hpu. 2016.0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leonardi C, Simonsen NR, Yu Q, Park C, Scribner RA. Street connectivity and obesity risk: evidence from electronic health records. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(1S1):S40–S47. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stepanikova I, Baker EH, Simoni ZR, et al. The role of perceived discrimination in obesity among African Americans. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(1S1):S77–S85. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stepanikova I, Bateman LB, Oates GR. Systemic inflammation in midlife: race, socioeconomic status, and perceived discrimination. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(1S1):S63–S76. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]