Abstract

Brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) are intended to provide independent communication for those with the most severe physical impairments. However, development and testing of BCIs is typically conducted with copy-spelling of provided text, which models only a small portion of a functional communication task. This study was designed to determine how BCI performance is affected by novel text generation. We used a within-subject single-session study design in which subjects used a BCI to perform copy-spelling of provided text and to generate self-composed text to describe a picture. Additional off-line analysis was performed to identify changes in the event-related potentials that the BCI detects and to examine the effects of training the BCI classifier on task-specific data. Accuracy was reduced during the picture description task; (t(8)=2.59 p=0.0321). Creating the classifier using self-generated text data significantly improved accuracy on these data; (t(7)=−2.68, p=0.0317), but did not bring performance up to the level achieved during copy-spelling. Thus, this study shows that the task for which the BCI is used makes a difference in BCI accuracy. Task-specific BCI classifiers are a first step to counteract this effect, but additional study is needed.

Keywords: Brain-computer Interface, Communication, BCI, Mental Workload, Novel text generation, P300, Latency jitter

1. Introduction

Brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) have long been proposed as a communication and technology control method for people with severe movement impairments resulting in a locked-in condition. BCIs offer the potential for accessing a communication application without physical movement, instead utilizing control signals taken directly from the brain to operate technology. The P300 BCI [1] has been a highly successful BCI used for generating text, and is used in subject homes as well as in laboratory experiments [2–4].

The P300 BCI presents a user with a display containing multiple options. The user focuses attention on the option that s/he wishes to select while the BCI produces stimuli which highlight the options in unpredictable patterns. By identifying which stimuli produces a P300 event-related potential in the user’s brain, the BCI can determine the option that is the user’s desired selection.

As BCIs transition into everyday use by people with physical impairments, the personal and environmental factors that affect BCI performance must be identified so that BCI methods can be optimized for realistic use. User motivation has been shown to effect P300 amplitude and BCI performance [5]. Workload measurements are increasingly being added to BCI performance metrics [6–8]. Further, Käthner et al. [9] showed that mental workload imposed by attending to environmental conditions can affect both P300 characteristics and BCI performance at a copy-spelling task. Their subjects experienced reduced BCI performance at a copy-spelling task when simultaneously attending to the content of recorded stories.

While BCI communication of user-selected text is the stated goal of many BCI studies, copy-spelling of provided text is the long-standing benchmark task for BCI testing (e.g. [1, 10, 11]), perhaps because it has minimal cognitive load and allows comparison of subtle effects of BCI design. Occasionally, studies permit subjects to use the BCI to generate their own messages [10], but message content and task-dependent performance is only starting to be analyzed [3]. However, copy-spelling models only a small portion of a functional communication task.

The P300 signal has long been known to be both smaller and delayed when a subject does simultaneous tasks or when the difficulty of stimulus identification increases [12, 13]. Further, we have found that increased variability in the P300 latency correlates with reduced BCI accuracy [14]. The only previous comparison of task-related BCI performance did not find accuracy differences when comparing copy-spelling of 10 characters of posted text and copy-spelling of remembered text [15]. However, authentic communication tasks create a greater work load than just remembering a couple of words. Authentic communication tasks require simultaneous generation of text, memory of the spelling of the desired word, switching from spelling to reading when word prediction is available, retaining location in the self-composed text, fixing errors that may occur, and also remembering conversational context. These factors could affect the P300, BCI performance, and ultimately communication effectiveness with BCIs.

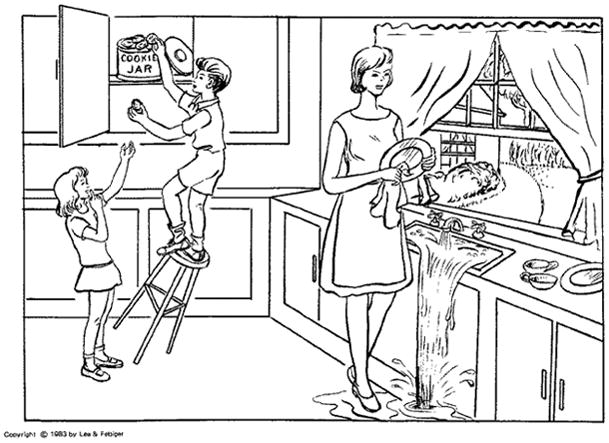

Communication effectiveness cannot be evaluated without measuring performance. Although copy-spelling tasks have often been used to assess the rate and accuracy of selecting targets using a BCI device [1, 16, 17], the gold standard for reporting language usage and overall communication competence is spontaneous production of communication content. Several language sampling procedures have been developed and standardized that allow researchers to collect, analyze, compare and contrast the spoken, written and/or augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) language samples of adults. Common, routine tasks include picture description [18], interviewing [19], story retelling [20], and natural daily conversation [3]. Use of a picture description task, e.g. the Cookie Theft Picture (Figure 1) [21] allows for the comparison of BCI user performance with the performance of other cohorts, specifically AAC speakers.

Figure 1.

Cookie theft picture used to prompt novel text generation [21].

This paper reports on a study done to address the hypothesis that communication task complexity (copy-spelling versus novel text generation of a picture description) is correlated with BCI performance accuracy and P300 characteristics.

2. Methods

Subjects and Equipment

There were 12 subjects (5 females, aged 36±18 years (mean ± standard deviation)) recruited from the University of Michigan and surrounding community. Subjects were adults who were able to read text on a computer screen with or without vision correction, able to give informed consent, and to understand and follow instructions concerning participation. Subjects could not have a history of photo-sensitive epilepsy, current open sores on the scalp, or abnormal tone or uncontrolled head or neck movements that would interfere with electroencephalogram (EEG) recordings. Subjects signed a consent form approved by our institutional review board. Subjects participated in a BCI session of about 3 hours duration. The EEG for this study was from electrodes Fz, Cz, P3, Pz, P4, PO7, PO8, and Oz, recorded using an electrode cap1 with reference and ground on the right and left mastoids respectively. Data were sampled at 256 Hz and recorded by a g.USBamp2 amplifier.

Experimental Protocol

The configuration protocol was as follows. Configuration data for the BCI were obtained by having the subject watch flashes of letters in individual words. Configuration data consisted of 21 characters with 30 target flashes per character. Classifier weights were determined using the stepwise linear discriminant analysis (SWLDA) in the BCI20003 configuration program with settings of Decimation Frequency=20Hz, Max Model Features=60 and Response Window 0 to 800ms after the flash. The number of sequences was configured for each subject by averaging the number of sequences that provided maximal written symbol rate [22] for weights created from the first 13 characters tested on the last 8 characters and weights created from the last 13 characters tested on the first 8 characters. The configuration weights for the experiment were calculated using all 21 characters. Accuracy of the configuration was tested by having the subject copy a 5-character word. If accuracy was 60% or less, then configuration was repeated.

The BCI display was a 6×6 (one subject) or 7×6 keyboard presented using BCI2000 with the checkerboard flash pattern [17]. The 7×6 BCI “keyboard” contained the alphabet, space, enter, and punctuation characters (period, comma, exclamation point, question mark, apostrophe, and semicolon). The 6×6 version had less available punctuation. In addition, the keyboard contained five special selections (w1, w2, w3, w4, and w5) to interface with the word prediction software WordQ version 3.4 Two selections provided correction functions: backspace to delete a single character and undo to reverse a word prediction entry (not present on the 6×6 version). A “pause” selection changed the display to a separate menu showing the same items, but with only an “unpause” selection active. This provided the subject the opportunity to take a break if desired. Capitalization functions were not provided to avoid task differences caused by subject opinion on whether the text should contain perfect capitalization. The BCI keyboard was connected to a laptop computer placed next to the BCI display. The multi-purpose BCI output device [23] enabled the BCI to connect to this computer as a standard USB keyboard. BCI output appeared only within a Notepad5 window on the laptop. No output appeared on the BCI display.

WordQ word prediction software provided a list of the 5 most likely word completions or next words. WordQ also provided some auto capitalization features and inserted spaces after a predicted word. This space was automatically removed if punctuation was added. Subjects practiced use of the word prediction function by copying the text “over the lazy dogs.” Subjects were then asked if they had any questions about using word prediction and given the opportunity for further practice if desired. A key logging program, KeyLAM,6 on the laptop computer recorded the exact time of each character entered. These data were merged with the log files from the BCI to identify the characters that were generated by the BCI and WordQ.

Experimental Tasks

Two tasks were done with the BCI. For copy-spelling with correction, subjects copied printed text posted above the BCI display. Subjects corrected errors to produce an exact copy of the text. Subjects continued to copy individual sentences until a minimum of 10 minutes had been spent at the copy-spelling task. A minimum of 10 minutes of copy-spelling was done before and after the alternate task to mitigate any fatigue effects on analysis.

The second task was a picture description task based on the Cookie Theft picture [21] that is typically used with adults to measure language performance. Subjects described a picture (Figure 1) following the instructions “Tell everything you see going on in this picture.” The picture was posted next to the BCI screen. The experimenter prompted the subject by pointing to neglected elements to see if the subject had anything further to generate. The task ended when the subject had nothing else to add.

The NASA task load index (NASA-TLX) [24] , was given for each task (after the picture description and after the final copy-spelling). The NASA-TLX has six subscales, which assess perceived performance and five aspects of perceived load (mental demand, physical demand, temporal demand, effort, and frustration). Subjects rate each element on a visual-analog scale with 20 divisions. The divisions are converted to a scale of 0–100 in 5 unit steps for analysis. Subjects were also asked to rate (on a scale of 1=Strongly Disagree to 4= Strong Agree) whether they were satisfied with using the BCI to “copy sentences” and “type my own sentences.”

Data Analysis

Careful attention to detail was needed to create an accurate record of selections intended by the subject (Figure 2). While the target text was known for the copy-spelling task, in the novel text generation task, the target text was determined by the subject. Further, the required correction of errors resulted in dynamic modification of intended text based on BCI performance, and the use of word prediction produced multiple correct options for next character selections. For example, a subject could select the next letter in a word or select the word from the word prediction list. The intended target list was created by examining the target sentence (or resulting self-generated text), the actual selections, and the word prediction list resulting from that character sequence. Errors of intent reported by a subject, such as accidentally skipping a letter, were recorded as part of the intended text. When multiple paths to correct text were available, the one executed by the subject was assumed to be intended. If multiple correct options were available, but neither was executed, and no report from the user was available, the intended selection was marked as unknown and excluded from accuracy analysis. Once the intended selections were determined, BCI accuracy was calculated as the percentage of attempted selections that matched the intended selection.

Figure 2.

Accuracy calculations for example sentence from subject P213. Intended text for each selection is based on examination of the target text, the results of the previous selections, and the word prediction list. The correctness of each selection (1 indicates correct, 0 indicates incorrect) is determined by comparing intended text and actual selections. Word Prediction Result column shows characters added if a word prediction number was selected. Text So Far shows the text as it appears after that selection. Note that if no incorrect selections were made, Intended Text and Actual Selections would be a perfect match. The appearance of the backspace (<BS>) does not necessarily indicate an error, since in this example, the subject backspaced to remove an unwanted space so the word change on the word prediction list could be used to build the word “changed,” which had not yet appeared in the word prediction list. In this example, 16 of 17 selections were correct, producing an accuracy of 94%.

Although each copy-spelling sentence was recorded in a separate data file, accuracy was calculated as the total number of correct selections for all sentences in each group (before copy-spelling, picture description, or after copy-spelling) divided by the number of attempted selections in the group. For comparison between copy-spelling and picture description, accuracy was calculated from the total of attempted and correct copy-spelling selections, combining the before and after groups. The effect of task was tested through paired t-tests of the accuracy for the tasks (done on the same day by the same subject in a within-subject design). For each of the six subscales of the NASA-TLX and the user satisfaction ratings considered together, a mulitivariate repeated measures ANOVA was used to compare perceived load for copy spelling and picture description. Individual paired t-tests were used to assess effects at the level of each of the six subscales and the user satisfaction rating. Statistics were calculated with SPSS v227 and SAS v 9.48.

P300 characteristics were calculated for the CZ and PZ electrodes for each subject. These electrodes are the primary electrodes for the P300 brain signal. The characteristics were P300 amplitude (mean and standard deviation), and latency of the mean P300 [25]. The peak of the P300 was identified in the average of all data for a particular task (copy or picture description) for each subject. The amplitude of the average and standard deviation at the peak was used for the P300 amplitude (mean and standard deviation) and the latency of the point after stimulus onset as the P300 latency. Additionally, we calculated the variance of the classifier based latency estimation (vCBLE) as a measure of event-related potential latency jitter using information from all electrodes [14]. Characteristics were calculated separately for the copy and picture description tasks. For the analysis of P300 characteristics, subject-specific grand averages were created for the copy and picture description tasks for both target and non-target stimuli. Multivariate repeated measures ANOVA was used to compare the P300 characteristics for the copy and picture description tasks. Paired t-tests were used to compare the separate P300 components.

Offline analysis of the data was performed to determine whether the task performed during collection of the training data affected the performance on the testing data. A 5-fold cross-validation analysis was performed in which weights were trained on 80% of the data for a particular task and then tested on the remaining 20% of the data for that task and all the data for the other task. The mean performance across the folds for a classifier created using copy-data was then compared to the mean performance for a classifier created using picture description data using a paired t-test.

3. Results

Of the 12 subjects recruited for this study, one had prior BCI experience. One subject did not attempt the picture description task while 2 others did not complete a minimum of 10 minutes of copy-spelling after the picture description task and were therefore excluded from analysis. The remaining 9 subjects (4 females, aged 40±20 years, one with prior BCI experience) spent an average of 31:14 (minutes:seconds) ± 2:48 copying text (15:49±1:42 before and 15:25±2:12 after picture description) and 36:53±13:35 generating picture description text. This resulted in an average of 93±22 selections for copying text and 101±37 selections for picture description per subject. With the word prediction, this produced 123±46 and 119±82 characters of text (no spaces) respectively (153±56 and 146±100 with spaces). Subject-optimized typing rates varied from 2 to 4 characters per minute (3.0±0.7) with sequences ranging from 2 to 5 (mean 3.2±1.0).

On-line results

Average BCI accuracy for copy-spelling before and after picture description showed no significant difference due to fatigue or other factors with averages of 91.8%±0.03 for both conditions (t(8)=0.01 p=0.9956) (Figure 3, left). Analysis with a paired t-test showed that average BCI accuracy for picture description was significantly less at 87.8%±5.8 than average accuracy for the copy-spelling at 91.6%±7.0 (t(8)=2.59 p = 0.0321) (Figure 3, right).

Figure 3.

Accuracy by subject for copy-spelling before and after (left) and copy-spelling versus generation of novel picture description text (right).

Off-line Results

Data from 8 subjects were available for EEG analysis due to loss of the picture description EEG file for one subject. A multivariate repeated measures ANOVA indicated that together the multivariate copy/picture description difference for the six P300 characteristics and vCBLE was statistically significant at the 0.1 level (F(1,7) = 3.877, p-value =0.09). Results from the individual paired t-tests are shown in Table 1. Only the vCBLE difference is significant, although the amplitude of electrode PZ trends toward significance. Note that vCBLE shows a strong subject effect (Figure 4). Example grand averages are shown in Figure 5.

Table 1.

P300 characteristics for attended targets: copy-spelling and picture description tasks.

| Copy-spelling (mean ± standard dev) | Picture Description (mean ± standard dev) | Paired t-test results | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Amplitude CZ (microVolts) | 7.711 ±3.285 | 7.325 ± 2.806 | t(7)= 0.44, p=0.6700 |

| Mean Amplitude PZ (microVolts) | 6.365 ±2.484 | 5.104 ± 1.391 | t(7)= 2.00, p=0.0854 |

| Stdev Amplitude CZ (microVolts) | 16.427 ± 4.652 | 20.901± 6.763 | t(7)= −1.50, p=0.1784 |

| Stdev Amplitude PZ (microVolts) | 15.256 ± 4.520 | 17.681±7.946 | t(7)= −0.79, p=0.4547 |

| Mean Latency CZ (milliseconds) | 218.8 ± 22.1 | 278.3 ± 127.9 | t(7)= −1.34, p=0.2209 |

| Mean Latency PZ (milliseconds) | 256.8 ± 45.3 | 264.2 ± 71.6 | t(7)= −0.38, p=0.7185 |

| vCBLE (milliseconds2) | 1,595.8 ±987.8 | 1,961.3 ±876.6 | t(7)= −2.53, p=0.0392 * |

Figure 4.

vCBLE values for copy-spelling and novel text generation by subject.

Figure 5.

Example grand averages at electrode Pz for copy-spelling (blue solid line) and picture description (red dotted line).

Off-line 5-fold cross-validation analysis was used to determine the effect of classifier training data (copy-spelling or picture description) on BCI accuracy. A two-way multivariate repeated measures ANOVA was used to assess the effect of classifier training and data type (copy-spelling or picture description) on BCI accuracy. The multivariate repeated measures ANOVA examined the main effects of type of classifier and type of data as well as the classifier/data interaction. There were no statistically significant main effects of classifier or data (Figure 6), but there was a statistically significant classifier x data interaction (F(1,7) = 8.057, p-value = 0.025). The classifier trained on copy-spelling data performed significantly worse when used on picture description data than on copy-spelling data (t(7)=2.43, p=0.0454) while the classifier trained on picture description data performed significantly better than the copy-spelling classifier on picture description data (t(7)= −2.68, p=0.0317). No other post-hoc comparisons showed significant differences.

Figure 6.

Average accuracy for off-line 5-fold cross-validation analysis for classifiers trained on copy data or on picture description data tested on copy data or picture description data. Error bars show standard deviations. P-values from a paired t-test are given for significant differences.

Workload Results

Eight of the 9 subjects completed the NASA-TLX ratings. The combined multivariate repeated measures ANOVA showed that the combined effect of copy/spelling and picture description across the 7 dependent variables was not statistically significant (p-value = 0.133, F = 2.891) Considered separately, only the Temporal Demand subscale showed a significant difference between copy-spelling and picture description (Table 2). Subjects reported lower mean temporal demand and slightly higher effort for the picture description task. The difference in user satisfaction between copy-spelling (3.1±0.3) and picture description (2.7±1.0) was not significant (t(8)= 1.51, p=0.169).

Table 2.

Top, NASA-TLX subscale scores (scale 0–100) for each task and p-values from a paired t-test. Bottom, user satisfaction with BCI.

| NASA-TLX Subscale | Scale interpretation | Copy (mean ± standard dev) | Picture Description (mean ± standard dev) | Paired t-test results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental Demand | 0 = Very Low | 55.0 ± 29.9 | 61.3±25.3 | t(7)= −1.02, p=0.3401 |

| Physical Demand | 0 = Very Low | 25.6 ± 20.9 | 26.3±21.7 | t(7)= −0.14, p=0.8904 |

| Temporal Demand | 0 = Very Low | 35.0 ± 17.3 | 11.9±4.6 | t(7)= 3.57, p=0.0091 * |

| Effort | 0 = Very Low | 51.9 ± 28.7 | 61.9±28.9 | t(7)= −1.54, p=0.1666 |

| Frustration | 0 = Very Low | 35.6 ± 27.3 | 36.9±30.9 | t(7)= 0.35, p=0.7347 |

| Performance | 0 = Perfect | 39.4 ± 20.9 | 41.3±24.9 | t(7)= −0.25, p=0.8111 |

| Custom measure | ||||

| User Satisfaction | 1 = Strongly Disagree | 3.1±0.3 | 2.7±1.0 | t(8)= 1.51, p=0.1690 |

significant difference

4. Discussion

These results show a significant reduction in accuracy for self-generation of text over copy-spelling. This difference was too small to have been detected in the short character strings used by McCane, et al. [15]. While the magnitude of the accuracy reduction was small, the consistency across subjects makes it a relevant issue. Further, the fact of such a difference engenders concern that using copy-spelling to evaluate BCI designs could lead to incorrect BCI design choices. Since copy-spelling is an unrealistic task, to ensure generalization of test results to actual communication use, BCIs should be tested with the type of text generation tasks that form the gold standard for evaluating communication performance and competence.

The reason for the reduction in accuracy is not fully understood, but is likely attributable to the significant vCBLE measure of latency variation during the picture description task. Increased vCBLE has been shown to be significantly correlated with decreased BCI accuracy [14]. The increased latency jitter and reduced accuracy during novel text generation may be attributable to the dual attention task of operating the BCI and composing text. This effect may also parallel the effect seen in keyboarding, in which generating novel text has been shown to be slower and less accurate task than copying text. However, reduced accuracy in BCI use may be a factor that can be accommodated by improved BCI designs that are robust to latency jitter.

Our off-line analysis evaluates the simplest approach to improving BCI performance for a novel text generation task by training a classifier on the same task for which it will actually be used. This analysis using 5-fold cross-validation confirmed the reduced accuracy seen on-line from using a copy-spelling trained classifier on picture description data. Interestingly, the classifier trained off-line, which was trained on the copy-spelling data with correction, showed better accuracy (94.3±5.7) when tested on the copy-spelling data with correction than the original on-line classifier (91.6%±7.0), which had been trained with copy-spelling data without correction, although the difference only trends toward significance (t(7)=2.01, p=0.0845). On the picture description data, the classifier trained on picture description data showed a small, but significant improvement in BCI accuracy. Note that although the average differences here are small, they are highly consistent across subjects, giving them significance. For example, the classifier trained on picture description data gave equal or better accuracy for all subjects than the classifier trained on copy-spelling data. This analysis shows that creating the classifier from data collected during realistic use does improve performance, although it does not bring performance to the level seen with the simple copy-spelling task.

Practically, careful consideration must be paid to the logistics of creating a classifier for a new BCI user based on data from novel text generation. The primary challenge of training the first classifier for a new user on user-generated training data is that the classifier methods used here require labeled intended text. The simplest approach to this issue is to follow the model used in this experiment, where an initial classifier is trained on copy-spelling data and then used to create data from user generated text. The corrections made by the user in the self-generated text can be used to label the intended text. A character followed by a backspace should be considered an error. Characters that are not deleted can be assumed to be intended. Thus, text composed freely by the user could be used to create a second, more accurate classifier that can subsequently be used for more accurate novel text generation. An adaptive method could even be used to automatically update the classifier during use, however such an approach would benefit from the use of two separate backspace options: one to indicate an error by the BCI and one to indicate a change of mind by the user.

Another approach could be used to create the initial classifier from something approaching data during subject-generation of text. While completely undirected text generation will not result in known intended text, several aspects of text generation could be simulated by removing the cues of the current location in the target text and requiring the user to hold the text in memory. Thus, the user could be instructed to use the text “My name is ______________” as the target for creating the training data. This would create known text, but with the spelling and location in the sentence kept in memory. The BCI display could be designed to display past characters (as would be the case during novel text generation), but the next target character must be drawn from memory. Either approach should produce a classifier based on data during text generation that mirrors everyday communication tasks and thus should produce more accurate BCI performance.

Interestingly, we found very little differences in the subjects’ perceptions of the task load between copy spelling and describing the picture. A significant difference was found on the temporal demand item that asked “How hurried or rushed was the pace of the task?”. Subjects indicated less of a time demand for completing the picture description; the more language based or realistic task. Also, the copy-spelling TLX was given at the end of the experiment, so the reduced temporal demand for novel text generation could not be attributed to increased familiarity with the BCI. Although slightly more effort was perceived on the picture description task, this finding was not significant despite the increased rate of inaccuracies. In addition, generation of text is considered typically a more effortful task, so our subjects were not overly sensitive to how hard generating novel text was using the BCI. Finally, no difference was found on the NASA TLX related to user satisfaction and other demands between copy spelling and picture description. Therefore, we can assume that the subjects did not feel that the overall work load differences were remarkable.

The effect of realistic communication tasks on BCI performance may be of more concern for people with ALS, a common target BCI user group. Up to 50% of people with ALS have been reported to have at least minor cognitive decline, which could exacerbate issues related to performing simultaneous tasks. In particular, people with ALS showed a greater performance decrease during a dual task condition than control subjects [26]. These declines are not seen in everyone with ALS. However, it raises a concern that novel text generation effects may be more pronounced for some individuals with ALS. Thus, it is very important that BCI design accommodate potential performance variations due to the task for which the BCI is used. Ultimately, the awareness of task-specific difference in BCI performance should lead to further development of BCI design to handle differences in brain activity during different tasks. In the short-term, however, improved performance in realistic tasks should be possible by creating the BCI classifiers using data gathered during BCI use under the proposed task conditions.

Initial results from a clinical demonstration of BCIs in the home by veterans with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis have started to report data on realistic task use [27]. Fourteen BCI users showed that they could use the BCI independently with the support of a home system operator. The BCI provided access to communication using WordPad and email programs along with access to the internet. Analysis of daily novel text generated data found a wide range for the percent of actual BCI time used for communication purposes [3]. However, use of communication tools (i.e. for WordPad or email) averaged 62 (±20SD)% (range 34–91%; median 63%) of total use for 345 daily logfile samples. These results indicate that individuals can achieve independence in using a BCI, and that the preferred home use is for communication. Consequently, every effort should be made to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the BCI for the preferred conditions of use by those who benefit from the technology.

Another critical step to provide evidence on the effectiveness and efficiency of BCI devices comes from analysis using standard linguistic measures of communication performance. Such analysis provides insight into the word choices and sentence structure used for communication. This type of language sample analysis is based on a distinct set of measures and calculation methods, therefore we plan to report separately on the linguistic performance results of the BCI-generated spontaneous, novel utterances produced for picture description.

Limitations

This study is limited by the small number of able-bodied subjects, who were all recruited from the same geographic area. Subjects participated in a single BCI session, and thus had limited experience both with BCI and word prediction. Although subjects averaged only 93 and 101 selections for copying text and picture description text respectively, this represents 30 minutes of effort on each task.

Conclusions

The task for which the BCI is used makes a difference in BCI accuracy. Task-specific BCI classifiers are a first step to counteract this effect. However, more research is needed to make BCIs as effective for realistic tasks as for copy-spelling.

Biographies

Dr. Huggins received her B.S. in Computer Engineering with a Biomedical Engineering option from Carnegie Mellon. She received a Ph.D. in Biomedical Engineering from the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor and completed a clinical Rehabilitation Engineering Internship. She founded the University of Michigan Direct Brain Interface Laboratory with Dr. Simon Levine. Dr. Huggins has been the director of the University of Michigan Direct Brain Interface Laboratory since 2007. Her current focus is making EEG-based brain-computer interfaces practical for people who need them.

Ramses E. Alcaide-Aguirre, 2260 Fuller Court #5, Ann Arbor MI 48105, Phone: 2066964469, pharoram@umich.edu.

Ramses graduated with a degree in electrical engineering from the University of Washington, and is pursuing a Ph.D. in neuroscience at the University of Michigan. His interest is in combining the fields of neuroscience and electrical engineering in order to develop intelligent prosthetic devices. Ramses’ research spans many fields including aerospace, forestry, energy, robotics, and medical applications. In recognition of his innovative achievements, Ramses has been named a Rackham Scholar, as well as a fellow at the NASA Foundation, Ford Foundation, and the National Science Foundation. He is also highly involved with his community, frequently working with recruitment and mentorship programs that promote higher education opportunities for students of color in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM).

Katya Hill, 6071 Forbes Tower, Pittsburgh, PA 15260, Phone: 412-383-6659, khill@pitt.edu

Katya Hill, PhD, CCC-SLP is an associate professor at the Department of Communication Science and Disorders, University of Pittsburgh. She is an internationally recognized clinician in the field of augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) and evidence-based practice. She has over thirty years of clinical experience with clients across the lifespan with complex communication and medical disorders along with years of teaching experience. Dr. Hill is the Executive Director/Clinical Supervisor and a co-founder of the AAC Institute and the ICAN Talk Clinic. She has been the force behind the research and development of Language Activity Monitoring (LAM) tools. Her most recent study entitled “Reliability of brain-computer interface language sample transcription procedures” appears in the current issue of the Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development.

Footnotes

Electro-Cap International, Inc, Eaton, OH, USA

Guger Technologies OEG, Graz, Austria

BCI2000 v2.0 build 2104, www.bci2000.org, Albany, NY, USA

Mayer-Johnson, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA

AAC Institute, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

IBM, Armonk, NY, USA

SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA

References

- 1.Farwell LA, Donchin E. Talking off the top of your head: Toward a mental prosthesis utilizing event-related brain potentials. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1988 Dec;70(6):510–23. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(88)90149-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holz EM, Botrel L, Kaufmann T, Kübler A. Independent BCI home-use improves quality of life of a patient in the locked-in state (ALS): A long-term study. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.03.035. Special Issue on the 5th International BCI Meeting (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hill K, Kovacs T, Shin S. Reliability of brain computer interface language sample transcription procedures. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development. 2014;51(4):579–90. doi: 10.1682/JRRD.2013.05.0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sellers EW, Vaughan TM, Wolpaw JR. A brain-computer interface for long-term independent home use. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2010 Oct;11(5):449–55. doi: 10.3109/17482961003777470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kleih SC, Nijboer F, Halder S, Kubler A. Motivation modulates the P300 amplitude during brain-computer interface use. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2010;2010 doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2010.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riccio A, Leotta F, Bianchi L, Aloise F, Zickler C, Hoogerwerf EJ, Kubler A, Mattia D, Cincotti F. Workload measurement in a communication application operated through a P300-based brain-computer interface. J Neural Eng. 2011 Apr;8(2):025028. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/8/2/025028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aloise F, Arico P, Schettini F, Riccio A, Salinari S, Mattia D, Babiloni F, Cincotti F. A covert attention P300-based brain-computer interface: Geospell. Ergonomics. 2012;55(5):538–51. doi: 10.1080/00140139.2012.661084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zickler C, Riccio A, Leotta F, Hillian-Tress S, Halder S, Holz E, Staiger-Salzer P, Hoogerwerf EJ, Desideri L, Mattia D, Kubler A. A brain-computer interface as input channel for a standard assistive technology software. Clin EEG Neurosci. 2011 Oct;42(4):236–44. doi: 10.1177/155005941104200409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kathner I, Wriessnegger SC, Muller-Putz GR, Kubler A, Halder S. Effects of mental workload and fatigue on the P300, alpha and theta band power during operation of an ERP (P300) brain-computer interface. Biol Psychol. 2014 Oct;102:118–29. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2014.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nijboer F, Sellers EW, Mellinger J, Jordan MA, Matuz T, Furdea A, Halder S, Mochty U, Krusienski DJ, Vaughan TM, Wolpaw JR, Birbaumer N, Kübler A. A P300-based brain–computer interface for people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2008;119(8):1909–16. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2008.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pires G, Nunes U, Castelo-Branco M. Comparison of a row-column speller vs. a novel lateral single-character speller: Assessment of BCI for severe motor disabled patients. Clin Neurophysiol. 2012 Jun;123(6):1168–81. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2011.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Isreal JB, Wickens CD, Donchin E. The dynamics of P300 during dual-task performance. Prog Brain Res. 1980;54:416–21. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)61653-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Picton TW. The P300 wave of the human event-related potential. J Clin Neurophysiol. 1992 Oct;9(4):456–79. doi: 10.1097/00004691-199210000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thompson DE, Warschausky S, Huggins JE. Classifier-based latency estimation: A novel way to estimate and predict BCI accuracy. J Neural Eng. 2013 Feb;10(1) doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/10/1/016006. 016006,2560/10/1/016006. Epub 2012 Dec 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCane L, Heckman SM, Vaughan TM, McFarland DJ, Carmack CS, Winden S, Sellers EW, Bedlack RS, Ringer RJ, Reda DJ, Shi H, Ruff RJ, Wolpaw JR. Use of a P300 BCI speller by people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS): Does the increased workload of a BCI application affect performance?. Proceedings of the Society of Neuroscience; 2014; Washington, DC. 2014. p. 165.01/II10. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson DE, Gruis KL, Huggins JE. A plug-and-play brain-computer interface to operate commercial assistive technology. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2013 Apr 16; doi: 10.3109/17483107.2013.785036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Townsend G, LaPallo BK, Boulay CB, Krusienski DJ, Frye GE, Hauser CK, Schwartz NE, Vaughan TM, Wolpaw JR, Sellers EW. A novel P300-based brain-computer interface stimulus presentation paradigm: Moving beyond rows and columns. Clin Neurophysiol. 2010 Jul;121(7):1109–20. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2010.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hux K, Wallace SE, Evans K, Snell J. Performing cookie theft picture content analyses to delineate cognitive-communication impairments. Journal of Medical Speech Language Pathology. 2008;16(2):83. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hill KJ. The development of a model for automated performance measurement and the establishment of performance indices for augmented communicators under two sampling conditions. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 20.McNeil MR, Sung JE, Yang D, Pratt SR, Fossett TR, Doyle PJ, Pavelko S. Comparing connected language elicitation procedures in persons with aphasia: Concurrent validation of the story retell Procedure. Aphasiology. 2007;21(6–8):775–90. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goodglass H, Kaplan E. The assessment of aphasia and related disorders. 2. Vol. 102. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1983. p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin J, Allison BZ, Sellers EW, Brunner C, Horki P, Wang X, Neuper C. An adaptive P300-based control system. J Neural Eng. 2011 Jun;8(3):036006. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/8/3/036006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson DE, Huggins JE. A multi-purpose brain-computer interface output device. Clinical EEG and Neuroscience. 2011;(October):230–5. doi: 10.1177/155005941104200408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hart SG, Staveland LE. Development of NASA-TLX (task load index): Results of empirical and theoretical research. Advances in Psychology. 1988;52:139–83. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kleih SC, Kaufmann T, Zickler C, Halder S, Leotta F, Cincotti F, Aloise F, Riccio A, Herbert C, Mattia D, Kubler A. Out of the frying pan into the fire--the P300-based BCI faces real-world challenges. Prog Brain Res. 2011;194:27–46. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53815-4.00019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pettit LD, Bastin ME, Smith C, Bak TH, Gillingwater TH, Abrahams S. Executive deficits, not processing speed relates to abnormalities in distinct prefrontal tracts in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain. 2013 Nov;136(Pt 11):3290–304. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruff RL, Wolpaw JR, Bedlack R. A Clinical Demonstration of an EEG Brain- Computer Interface for ALS Patients. 2011. [Google Scholar]