Abstract

Few studies have investigated the impact of adolescent change language on substance use treatment outcomes and even fewer have examined how adolescents respond to normative feedback. The purpose of this study was to understand the influence normative feedback has on adolescent change language and subsequent alcohol and cannabis use 3 months later. We examined how percent change talk (PCT) was associated with subsequent alcohol and drug use outcomes. Adolescents (N = 48) were randomly assigned to receive brief motivational interviewing (MI) or MI plus normative feedback (NF). Audio recordings were coded with high interrater reliability. Adolescents with high PCT who received MI + NF had significantly fewer days of alcohol and binge drinking at follow up. There were no differences between groups on cannabis use or treatment engagement. Findings indicate that NF may be useful for adolescents with higher amount of change talk during sessions and may be detrimental for individuals with higher sustain talk.

Keywords: Alcohol treatment, Cannabis use, Adolescents, Motivational interviewing, Change talk

1. Introduction

Adolescence represents a time when alcohol and drug use begins to increase (Johnston, 2013; Shih, Miles, Tucker, Zhou, & D’Amico, 2012) with many or most high school seniors reporting they have tried alcohol (70%) and cannabis (45%) at least once (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2013). Adolescent substance use disorder (SUD) treatment admissions have remained stable over the past several years representing 7% of all admissions (SAMHSA, 2014). Nearly 90% of all adolescent treatment admissions involved cannabis as a primary or secondary substance and alcohol use disorders represent 52% of all mild SUD cases (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2011; SAMHSA, 2014).

Interventions such as motivational interviewing (MI; Miller & Rollnick, 2012) are efficacious in reducing alcohol and drug use in adult (see Magill et al., 2014), emerging adult (e.g. Apodaca et al., 2014), and adolescent (e.g. Baer et al., 2008; D’Amico et al., 2012) studies. Recently, researchers have become interested in the mechanisms through which MI works, investigating nuanced within-session factors such as client change talk (CT) and sustain talk (ST). Change talk refers to “any self-expressed language that is an argument for change” (Miller & Rollnick, 2012, p. 159) and sustain talk is a “person’s own arguments for not changing, for sustaining the status quo” (Miller & Rollnick, 2012, p. 7). Normative feedback (NF), when combined with MI, is efficacious for emerging adults and increases their change language (Neighbors et al., 2010; Vader, Walters, Prabhu, Houck, & Field, 2010; Walters & Neighbors, 2005). However, some researchers posit that NF may increase sustain talk among adolescents, resulting in poorer outcomes (Osilla et al., 2015). Therefore, the purpose of this study was to understand how NF influenced change language within an adolescent MI intervention designed to increase treatment adherence and reduce substance use. Findings will help personalize interventions for specific treatment populations such as youth presenting for alcohol use disorder treatment.

1.1. Motivational interviewing and its key components

MI is a client-centered and directive intervention designed to resolve ambivalence about change (Miller & Rollnick, 2012). MI encourages individuals to articulate the potential benefits of change, respects individuals’ autonomy (Barnett, Sussman, Smith, Rohrbach, & Spruijt-Metz, 2012; Smith & Hall, 2007; Smith, Hall, Jang, & Arndt, 2009), and emphasizes the collaborative therapeutic relationship in which therapists elicit and reinforce client change talk (Baer et al., 2008; Barnett et al., 2014a, 2014b). MI is an efficacious intervention for at-risk adolescents (Baer et al., 2008; Carcone et al., 2013; D’Amico et al., 2015; D’Amico et al., 2012; Erickson, Gerstle, & Feldstein, 2005; Feldstein & Ginsburg, 2006; Naar-King & Suarez, 2011; Smith, Davis, Ureche, & Tabb, 2015; Spirito et al., 2011; Walker, Roffman, Stephens, Wakana, & Berghuis, 2006). Few adolescent studies have investigated the active ingredients of MI or its mechanisms of change.

1.2. Change talk and sustain talk as predictors of outcomes

A nascent literature focuses on technical mechanisms within an MI session such as client and therapist behaviors, and how such behaviors predict treatment outcomes (Miller & Rose, 2009). One review found in-session client behaviors such as CT and ST, and clinician behaviors like maintaining MI spirit and MI-consistent behaviors were strong predictors of subsequent substance use outcomes (Apodaca & Longabaugh, 2009). Other research has demonstrated links between therapist skills and behaviors on client CT. For example, sequential analyses show higher probabilities of client CT immediately after therapists use MI-consistent skills (e.g. offering support, affirming, emphasizing autonomy and personal choice) and more ST immediately following use of MI-inconsistent skills (e.g. confronting, giving advice without permission, and warning; Gaume, Gmel, Faouzi, & Daeppen, 2008, 2009; Gaume, Bertholet, Faouzi, Gmel, & Daeppen, 2010; Moyers & Martin, 2006; Moyers, Martin, Houck, Christopher, & Tonigan, 2009). Early studies investigating the impact of CT found participants who reduced their substance use at post-treatment had higher proportion of CT statements (Amrhein, Miller, Yahne, Palmer, & Fulcher, 2003). Numerous replications show that within-session CT is associated with changes in alcohol use (Bertholet, Faouzi, Gmel, Gaume, & Daeppen, 2010; Magill, Apodaca, Barnett, & Monti, 2010; Martin, Christopher, Houck, & Moyers, 2011; Moyers et al., 2009; Vader et al., 2010), cannabis use (Walker, Neighbors, Rodriguez, Stephens, & Roffman, 2011a; Walker, Stephens, Rowland, & Roffman, 2011b) and illicit drug use (Aharonovich, Amrhein, Bisaga, Nunes, & Hasin, 2008). However, more recent evidence suggests that, while CT is important to elicit, it may be more important to reduce the amount of ST. Magill et al. (2014) conducted a meta-analysis and tested the causal model linking therapist behaviors to client CT and subsequent treatment outcomes. Results suggested no significant relationship between CT and outcomes. However, composite measures of CT such as percent CT (PCT) were associated with better outcomes and client ST predicted worse outcomes. Similar results were found in a study with mandated college students where client ST, but not CT, was significantly associated with poorer alcohol use outcomes (Apodaca et al., 2014).

1.3. Adolescent substance use and change talk

The studies above were completed with adult and emerging adult samples, prompting the question – how well does client change language predict outcomes with adolescents? To date only five adolescent studies investigated the impact of client CT on subsequent treatment outcomes (Baer et al., 2008; Barnett et al., 2014a, 2014b; D’Amico et al., 2015; Engle, Macgowan, Wagner, & Amrhein, 2010; Osilla et al., 2015). Baer et al. (2008) recruited homeless adolescents (n = 54), finding adolescents expressing more CT (i.e., reasons subtype) were more likely to be abstinent at 1 and 3 month follow up. Barnett et al. (2014a, 2014b) found that PCT mediated the relationship between therapist behaviors and cannabis outcomes at 1 year post-treatment (n = 107). While understanding how individual therapy impacts client CT is important, many studies utilize a group format (Kaminer, 2005). Engle et al. (2010) investigated the impact of group MI (n = 108, k = 19 groups) on cannabis use at 1, 4, and 12-month follow up. Though only correlational, results supported a mediational model where group commitment language (i.e. group change language) mediated the relationship between therapist behaviors and cannabis use outcomes at post-test, 1-month, 4-month, and 12-month follow up. D’Amico et al. (2015) investigated group-level adolescent CT and ST as mechanisms of change (n = 129). Using sequential analysis, group CT was associated with individual reductions in alcohol use, heavy drinking, and alcohol intentions at 3-month follow up. Group CT was not associated with any cannabis variables. Further, group ST was not associated with alcohol or cannabis use but was associated with increased intentions to use cannabis and positive expectancies for alcohol and cannabis use. Finally, Osilla et al. (2015) explored how various types of CT (e.g. ability, reason, commitment, other) and ST (e.g. reason) were associated with subsequent alcohol and drug use at 3-month follow up using multilevel modeling. Results indicated commitment (e.g. “I’m not hanging out with them anymore so I won’t drink”) and reason (e.g. “I don’t want to fail out of school”) CT subtypes were associated with decreased alcohol, fewer alcohol consequences, lower alcohol use intentions, and lower cannabis intentions. ST was not associated with outcomes.

1.4. Normative feedback and adolescent substance use

Normative feedback (NF) interventions strive to alter an individual’s perception of their drinking or drug use by contrasting, or comparing, their current substance use against a representative sample of their peers. That is, NF interventions target an individual’s misperception of the frequency and quantity of their peers’ substance use (Pedersen et al., 2013; Walker et al., 2011a). Extant studies document the efficacy of NF interventions for reducing college drinking (Baer et al., 1992; Borsari & Carey, 2000; Collins, Carey, & Sliwinski, 2002; Dimeff & McNeely, 2001; Larimer et al., 2001; Marlatt et al., 1998; Murphy et al., 2004; Neal & Carey, 2004; Neighbors, Lee, Lewis, Fossos, & Larimer, 2007; Walters & Bennett, 2000; Walters & Neighbors, 2005; Walters & Woodall, 2003; Walters, Vader, & Harris, 2007). Only one study, however, has investigated whether a normative feedback component is an active ingredient in brief MI treatment with adolescents and (Smith, Ureche, Davis, & Walters, 2015) randomly assigned youth (n = 48) to receive MI or MI plus NF. Adolescents receiving NF had lower post-session readiness to change (Smith et al., 2015), lower self-reported treatment engagement (d = −.31, ns; Smith et al., 2015), and fewer days of abstinence (−7.9%, ns) at 3-months, however these effects showed no differences between groups. These findings, while not significant, echo anecdotal concerns about the appropriateness of NF for adolescents (Winters, Fahnhorst, Botzet, Lee, & Lalone, 2012). That is, for some adolescents NF may elicit a surprise or ambivalence to the information as they may view their use as “normal” (Osilla et al., 2015). Further, Barnett et al. (2012) noted that, compared to college students, adolescents may not be as receptive to NF given the varying levels of psychological reactance (Hong, Giannakopoulos, Laing, & Williams, 1994). Other studies found adult substance users’ CT decreased when receiving feedback (Amrhein et al., 2003) and among adolescents the percent of ST increased during sessions including NF (Osilla et al., 2015).

1.5. The current study

Using data from a randomized controlled trial examining the impact of MI and MI plus NF among adolescents presenting for a substance use assessment (Smith et al., 2015), we investigated whether the percentage of change talk (PCT) was 1) predictive of 3-month alcohol and cannabis use outcomes and 2) predictive of treatment engagement (attending 3 or more sessions post assessment). Based on prior concerns in the literature, we tested whether receipt of NF interacted with PCT to predict worse alcohol and cannabis use outcomes at 3-month follow up. Finally, we used sequential analyses to explore the communication patterns present in these sessions. This will be the first study to investigate the associations between NF, PCT and subsequent drug and alcohol use.

2. Methods

2.1. Procedure and sample

Session tapes (n = 43) were recorded as part of a larger study designed to isolate the effects of NF within a brief post-assessment MI intervention designed to increase treatment engagement (Smith, 2012; Smith et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2015). In the original study, consecutively referred adolescents from two not-for profit treatment agencies were invited to participate if they were referred for substance use disorder intake assessments, used substances on a weekly basis, or had CRAFFT (Knight, Sherritt, Harris, Gates, & Chang, 2003) screener scores over two. Those who volunteered were randomized to receive either MI (n =22) or MI + NF (n = 26). Therapist training procedures were rigorous, with 15 tapes (34.8%) coded for MI adherence. Therapists received 12 hours of MI didactic training, feedback from coded mock tapes prior to participant enrollment, and received coaching on session tapes during the study period. Training and feedback were provided by the fifth author, a member of the Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers (MINT). Tapes were coded using the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity Scales (MITI, 3.1.1; T. Moyers, Martin, Manuel, Miller, & Ernst, 2010) with a mean MI spirit rating of 4.11 (SD = .45), a reflection to question ratio mean of 1.74 (SD = 1.15), a percent of MI adherent responses of 99% (SD = 3.0), a percent of complex reflections at 52% (SD = 12.0), and a mean percent of open questions of 62%, (SD = 23.0). Follow up attrition was low, and efforts were made to collect data from participants that did not complete MI sessions (i.e., intent to treat). For full details on the original study, see Smith et al. (2015) and Smith et al. (2015). Recordings were available for 43 study participants (89.5%), with missing recordings occurring due to youth not attending the MI session after randomization (n = 3), interviewers forgetting to record (n = 1), or the participant refusing to be recorded (n = 1).

Participants were mostly male (77.1%) and racially-diverse adolescents (mean age = 16.3, 76.6% ethnic minority). Most participants (85.4%) met the DSM-5 SUD criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). On average participants reported binge drinking on 5.7 (SD = 12.1) days, using alcohol on 8.8 (SD = 15.8) days, and cannabis on 44.2 (SD = 33.6) days in the 90 days prior to the baseline assessment. In short, participants were heavily-using adolescents referred for initial SUD assessments.

2.2. Coding and parsing

Intervention audio recordings (n = 43) were coded independently by two raters using an objective sequential coding system: the Motivational Interviewing Skill Code (MISC 2.5; Houck, Moyers, Miller, Glynn, & Hallgren, 2010) and the CACTI coding application (Glynn, Hallgren, Houck, & Moyers, 2012). Sequential coding was performed using CACTI to preserve the temporal order of behaviors across the sessions with 12% of the sample (5 sessions) randomly selected for double-coding to assess inter-rater reliability.

Coders were previously trained on the MISC 2.5 and attended weekly coder meetings to prevent coder drift. Discrepancies during coder meetings were discussed and resolved using the coder manual and expert supervision. Inter-rater reliability was good to excellent based on well accepted guidelines (Cicchetti & Sparrow, 1981). Interclass correlations were .584 for change talk, .882 for sustain talk, .839 for percent change talk, .973 for open questions, and .845 for reflections of change talk. The utterance-to-utterance reliability of our coders was k = .58, indicating approximately 63% agreement on the exact sequence of behaviors (Bakeman, McArthur, Quera, & Robinson, 1997). This utterance-to-utterance reliability estimate is less biased than count approaches (Lord et al., 2015), and is commonly assessed in sequential coding studies (e.g., D’Amico et al., 2015; Moyers et al., 2009). Coders’ behavior count and utterance-to-utterance reliabilities were high.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. GAIN Q3

The GAIN-Q3 (Titus et al., 2012a, 2012b) is a semi-structured assessment that covers a wide range of life domains including substance use, mental health, school and work problems, physical health, stress, and risk behaviors. The GAIN-Q3 was derived from the larger instrument, the GAIN-I (Dennis, Titus, White, Unsicker, & Hodgkins, 2003), and has a validated training and supervision process (Titus et al., 2012a, 2012b). The GAIN-Q3 uses time line follow back (TLFB; Sobell & Sobell, 1992) procedures, where participants are asked to recall, for example, days of alcohol use in the past 90 days. All variables described below came from the GAIN-Q3 baseline and follow-up assessment.

2.3.2. Outcomes

Counts of the number of days participants reported using alcohol and cannabis in the past 90 days were assessed at baseline and 3-month follow up. Binge drinking was also assessed by asking participants how many days, in the past 90, they got drunk or drank 5 or more drinks. To measure treatment engagement at 3-month follow up, we asked participants how many days they received any substance use treatment in the past 90 days. In accordance with previous literature (Garnick, Lee, Horgan, & Acevedo, 2009) we defined treatment engagement as attending three or more post-assessment treatment sessions (1 = engaged, 0 = not engaged).

2.3.3. Statistical analyses

Behavior codes produced by the MISC are count variables that can be confounded by session length; that is, longer sessions necessarily have more instances (i.e., higher counts) of many behaviors than do shorter sessions. To adjust for this, counts for each session were scaled by the length of that session. Session length was selected rather than the number of utterances because session length is unbiased by the rater’s parsing of the session. All speech measures used in outcome analysis were analyzed in the form of these rate variables, rather than as raw counts. Client change language was evaluated as the percentage change talk (i.e., CT/(CT + ST)), using the CT and ST rate variables. All count outcomes were evaluated using negative binomial regression with a log link (see Atkins, Baldwin, Zheng, Gallop, & Neighbors, 2013 for a tutorial). Dichotomous outcomes were evaluated using logistic regression. All outcome analyses were conducted using Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012). Missing data were handled using full information maximum likelihood (FIML) which estimates a case-wise likelihood function based on the variables that are present so that all the available data are used for each subject (Allison, 2002; Graham, 2009; Schafer & Graham, 2002). Interaction effects were probed using simple slopes analysis, using procedures described by Preacher and colleagues (Preacher, Curran, & Bauer, 2006). Finally, to examine the effects of feedback on therapist MI skill, within the NF group we split each CACTI file at the time of the first NF utterance using procedures developed by the second author (Houck, Hunter, Benson, Cochrum, & Rowell, 2015) and computed behavior counts and summary scores separately for each segment. MI skill was evaluated using standard summary measures including the number of MI-consistent (MICO) and MI-inconsistent behaviors (MIIN), each scaled as described above, as well as the percentage of MI-consistent utterances (%MIC; i.e., MICO/(MICO + MIIN)). Due to non-normality of the summary measures, the influence of NF on MI skill was evaluated using Wilcoxson matched-pair signed rank tests. Because NF utterances were rare, occurring less than five times in each NF session, it was not possible to examine NF in our sequential analysis.

In sequential coding, the term “lag” is used to indicate the relative position of utterances. Lag 0 indicates the first utterance in the series of interest, lag 1 indicates the second, lag 2 indicates the third, and so on. For example, in the exchange “(A) [Tell me about your drinking] (B) [I don’t really drink that much] (C) [but I guess I have been smoking a lot]”, if utterance A is designated as the lag 0 (given) behavior, utterance B is the lag 1 behavior, and utterance C is the lag 2 behavior. We assessed sequential patterns only at lag 1; that is, the temporally-adjacent behaviors. For any given behavior, this allows us to estimate the probability that the very next behavior to occur will come from any other behavior assessed by the coding system. Estimation of sequential patterns was performed using the General Sequential Querier (GSEQ 5.1; Bakeman & Quera, 2012).

3. Results

3.1. Intervention integrity

Independent samples t-tests indicated significantly more clinician normative feedback in the MI + NF condition than in the MI condition (t (26.011) = 6.135, p < .001). No significant between-group differences were detected for session length (t (26.986) = 1.470, p > .15), client change talk (t (29.921) = .274, p > .75), sustain talk (t (29.098) = 1.159, p > .25), or neutral speech (t (36.678) = 1.252, p > .20).

3.2. Treatment Integrity

Independent samples t-tests indicated no significant between-group differences on common measures of MI competence including MI-consistent behaviors (i.e., MICO; t(38) = 0.588, p > .55), MI-inconsistent behaviors (i.e., MIIN; t(39) = 0.04, p > .95), percent MI consistent (i.e., MICO/(MICO + MIIN); t(38) = 0.011, p > .99), ratio of reflections to questions (t(38) = 1.058, p > .30), percent open questions (i.e., OQ/(OQ + CQ); t(38) = 0.339, p > .70), or percent complex reflections (i.e., CR/(SR + CR); t(38) = 0.20, p > .80).

3.3. Drinking outcomes

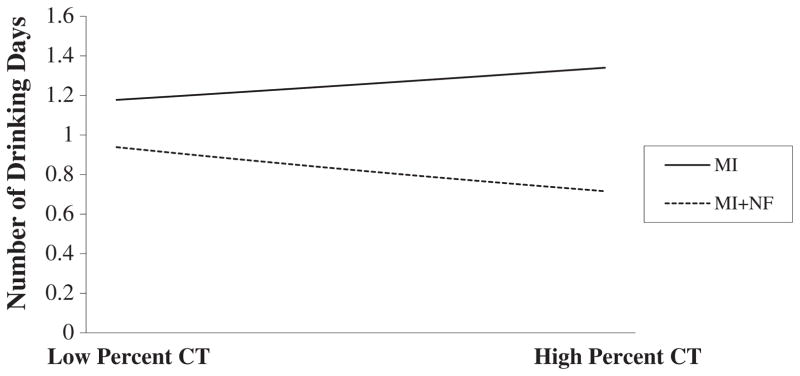

We examined drinking days at 3 months, baseline drinking days, PCT, condition, and the condition × PCT interaction. Results supported use of the negative binomial distribution (dispersion parameter α = 1.817, p < .001) and indicated significant effects of baseline drinking days (coefficient = 0.146, p < .001) and for the condition × PCT interaction (coefficient = −14.340, p < .01). Higher baseline drinking was related to more drinking at follow-up. Analysis of the interaction effect indicated that participants with high PCT had significantly fewer drinking days in the MI + NF group at follow-up than did those in the MI group (see Fig. 1). Complete results are presented in Table 1a.

Fig. 1.

Interaction of percent CT and condition for drinking days at 3 months. Note: MI = motivational interviewing; NF = normative feedback; CT = change talk.

Table 1.

Effects on drinking outcomes.

| Variable | Estimate | SE | t ratio | p | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| A. Number of drinking days | ||||||

| Intercept | 0.228 | 0.468 | 0.487 | 0.626 | −0.689 | 1.144 |

| Condition | −0.427 | 0.531 | −0.803 | 0.422 | −1.468 | 0.615 |

| Baseline drinking days | 0.146 | 0.035 | 4.181 | 0.000 | 0.077 | 0.214 |

| Percent CT | 4.634 | 2.440 | 1.899 | 0.058 | −0.149 | 9.417 |

| Percent CT × condition | −14.340 | 4.330 | −3.312 | 0.001 | −22.82 | −5.853 |

| B. Number of binge drinking days | ||||||

| Intercept | −0.055 | 0.530 | −0.104 | 0.917 | −1.094 | 0.983 |

| Condition | −0.230 | 0.711 | −0.323 | 0.747 | −1.624 | 1.165 |

| Baseline binge drinking days | 0.147 | 0.048 | 3.073 | 0.002 | 0.053 | 0.241 |

| Percent CT | 4.990 | 3.322 | 1.502 | 0.133 | −1.521 | 11.502 |

| Percent CT × condition | −11.334 | 5.702 | −1.988 | 0.047 | −22.509 | −0.158 |

Note. CT = change talk.

The significant interaction term indicates that the slopes for the MI and MI + NF groups for drinking days differed from each other. Simple slopes analysis for values of PCT ±1 SD from the mean indicated that for the MI group, the gradient differed significantly from zero (gradient = 5.248, t = 31.3235, p < .001); for the MI + NF group, the gradient also differed significantly from zero (gradient = −2.813, t = −20.099, p < .001).

We also examined binge drinking days at 3 months, baseline binge drinking days, PCT, condition, and the condition × PCT interaction. Results supported use of the negative binomial distribution (dispersion parameter α = 3.256, p < .01) and indicated significant effects of baseline drinking days (coefficient = 0.147, p < .01) and for the condition × PCT interaction (coefficient = −11.334, p < .05). Higher baseline binge drinking was related to more binge drinking at follow-up. Analysis of the interaction effect indicated that participants with high PCT had significantly fewer binge drinking days in the MI + NF group at follow-up than did those in the MI group (see Fig. 2). Complete results are presented in Table 1b.

Fig. 2.

Interaction of percent CT and condition for binge drinking days at 3 months. Note: MI = motivational interviewing; NF = normative feedback; CT = change talk.

The significant interaction term indicates that the slopes for the MI and MI + NF groups for binge drinking days differed from each other. Simple slopes analysis for values of PCT ±1 SD from the mean indicated that for the MI group, the gradient differed significantly from zero (gradient = 0.853; t = 5.425, p < .001); for the MI + NF group, the gradient also differed significantly from zero (gradient = −0.383, t = 2.456, p < .05).

3.4. Cannabis outcomes

We examined cannabis use days at 3 months, baseline cannabis use days, percent CT, condition, and the condition × PCT interaction. Results supported use of the negative binomial distribution (dispersion parameter α = 2.256, p < .001) and indicated significant effects only for baseline cannabis use days (coefficient = 0.020, p < .05). Higher baseline cannabis use was related to more cannabis use at follow-up. Complete results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Effects on days of cannabis use.

| Variable | Estimate | SE | t ratio | p | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Intercept | 2.336 | 0.460 | 5.075 | 0.000 | 1.434 | 3.238 |

| Condition | 0.169 | 0.494 | 0.342 | 0.732 | −0.800 | 1.138 |

| Baseline cannabis days | 0.020 | 0.008 | 2.439 | 0.015 | 0.004 | 0.037 |

| Percent CT | −0.970 | 2.043 | −0.475 | 0.635 | −4.974 | 3.034 |

| Percent CT × condition | −1.582 | 3.534 | −0.448 | 0.654 | −8.508 | 5.344 |

Note. CT = change talk.

3.5. Treatment engagement

We examined treatment engagement at 3 months, PCT, condition, and the condition × PCT interaction. No significant effects were detected. Complete results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Effects on treatment engagement.

| Variable | OR | Estimate | SE | t ratio | p | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Condition | 0.511 | −0.672 | 0.712 | −0.934 | 0.346 | −2.068 | 0.725 |

| Percent CT | 0.025 | −3.678 | 3.071 | −1.198 | 0.231 | −9.697 | 2.342 |

| Percent CT × condition | 12.568 | 2.531 | 6.290 | 0.402 | 0.687 | −9.797 | 14.859 |

Note. CT = change talk. OR = odds ratio.

3.6. Sequential results

A state transition diagram of the behaviors most related to client change language is given in Fig. 3. The transition matrix deviated significantly from random transitions (χ2 (100) = 6786.05, p < .001), indicating that the transitions that we observed between behaviors in the present study did not occur at random. The sequential dependencies in Fig. 3 are reported as odd ratios, with the odds of the transition of interest occurring in the numerator and the odds of all other transitions occurring in the denominator. For example, in a case where the transition of interest is RCT to CT, and the transition from RCT to CT occurred 10 times, the transition from RCT to all other behaviors occurred 15 times, the transition from all other behaviors to CT occurred 4 times, and the transition from all other behaviors to all other behaviors occurred 31 times, the odds ratio would be computed as , for an odds ratio of 5.167. Odds ratios greater than 1 indicate that the transition is more likely than expected by chance, while odds ratios less than one indicate that the transition is less likely than expected by chance. In these sessions, open-ended questions (OQ) and reflections of change talk (RCT) by the therapist were more likely to be followed by client change talk (OQ OR = 2.80; 95% CI [2.35, 3.34]; RCT OR = 3.74, 95% CI [3.29, 4.25]). When the interventionist reflected sustain talk, change talk was suppressed (OR = 0.15, 95% CI [0.07, 0.30]); instead, these reflections of sustain talk were more likely to be followed by sustain talk (OR = 13.89; 95% CI [10.38, 18.59]). When youth produced change talk, they were significantly more likely to continue with additional change talk (OR = 2.40; 95% CI [2.17, 2.67]). After sustain talk, youth were significantly more likely to continue with additional sustain talk (OR = 12.02, 95% CI [10.13, 14.27]). Youth were also less likely to transition to neutral speech after change talk (CT) or sustain talk (ST) (CT OR = 0.36, 95% CI [0.31, 0.42]; ST OR = 0.71, 95% CI [0.58, 0.87]). Table 4 displays lag-one conditional probabilities.

Fig. 3.

State transition diagram for behaviors related to client change language. Note: Dotted line = related to sustain talk, solid line = related to change talk. Positive valence (+) = significantly more likely than chance; negative valence (−) = significantly less likely than chance.

Table 4.

Lag-one conditional probabilities for within-session speech.

| Initial behavior | Subsequent behavior | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Change | Sustain | Neutral | sMICO | MIIN | Open | Closed | RefChan | RefSust | RefOth | TherOth | |

| Change | .35+ | .07 | .10− | .05− | .01− | .05 | .03− | .20+ | .01− | .02− | .10− |

| Sustain | .17− | .39+ | .15− | .03− | .01 | .02− | .02− | .05− | .07+ | .03− | .06− |

| Neutral | .12− | .06− | .11− | .10+ | .02+ | .05 | .06 | .07− | .02 | .16+ | .25+ |

| sMICO | .07− | .01− | .32+ | .15+ | .01 | .08+ | .08+ | .06− | .00 | .03− | .18+ |

| MIIN | .18 | .08 | .17 | .10 | .10+ | .04 | .12+ | .03− | .00 | .02 | .17 |

| Open | .43+ | .04− | .43+ | .01− | .00 | .03− | .02− | .01− | .00 | .01− | .03− |

| Closed | .21 | .03− | .63+ | .02− | .00 | .01− | .03− | .00 | .00 | .00 | .07− |

| RefChan | .47+ | .01− | .04− | .04− | .00 | .04− | .04 | .25+ | .02 | .03− | .05− |

| RefSust | .04− | .50+ | .08− | .03− | .01 | .01− | .00 | .13 | .13+ | .03 | .05− |

| RefOth | .04− | .02− | .57+ | .04− | .00 | .05 | .04 | .09 | .02 | .08+ | .07− |

| TherOth | .10− | .02− | .18 | .14+ | .02+ | .11+ | .13+ | .06− | .01− | .04− | .19+ |

Note: sMICO = sequential MI-consistent behaviors, including advice with permission, affirm, emphasize control, and support, but excluding reflections and open questions, which are categorized separately. MIIN = MI-inconsistent behaviors, including advice without permission, confront, direct, raise concern without permission, and warn; RefChange = reflections of change talk; RefSustain = reflections of sustain talk; RefOther = all other reflections; TherOth = all therapist behaviors not otherwise captured, including facilitate, filler, give information, structure, raise concern with permission, and inaudible/uncodeable utterances.(+) = significantly more likely than expected by chance; (−) = significantly less likely than expected by chance.

3.7. Effects of feedback on MI skill

We found no support for the hypothesis that therapist MI skill would be reduced by normative feedback. No significant differences were detected in the pre-NF and post-NF segments for MICO (Z = −1.529, p = .126), MIIN (Z = −0.722, p = .470), or %MIC (Z = −0.594, p = .552).

4. Discussion

This is the first investigation finding an interaction between NF and client change talk in predicting adolescent substance use outcomes. This study sets out to answer three key questions: 1) Does PCT predict alcohol and cannabis use 3 months following a post-intakeMI based assessment?, 2) Does client change language predict treatment engagement?, and 3) Does NF interact with PCT to produce worse alcohol and cannabis outcomes? A secondary aim of the paper was to report transitional probabilities, documenting typical adolescent responses to clinician behaviors.

For question 1 and 2, we found that overall PCT was trending toward significance for days of alcohol use (p = 0.05), however PCT did not predict binge drinking (p = 0.13), cannabis use (p = 0.64) or treatment engagement (p = 0.23); instead the effect of PCT varied depending upon treatment condition.

For question 3, we found the opposite of what was hypothesized. Adolescents assigned to MI + NF who had high PCT had significantly lower number of alcohol use days and binge drinking days compared to individuals receiving only MI. Contrary to anecdotal concerns about using NF with adolescents (Barnett et al., 2012; Winters et al., 2012) our study finds lower binge drinking days and any alcohol use days among those with high change talk only in the MI + NF condition. Those with high CT in the MI condition actually increased their overall and binge drinking days. This peculiar finding contradicts prior research showing that CT predicts MI outcomes on alcohol use for both adults and adolescents (Moyers et al., 2009). It may be that for younger adolescent drinkers with episodic binge drinking patterns, the combination of high CT and NF is necessary. This could be because NF may be raising adolescents’ awareness of non-normative behavior (i.e., developing discrepancy), which could account for the different way CT influences drinking across the MI and MI + NF conditions. This significant interaction suggests an important relationship between NF, PCT, and alcohol use among adolescents. For example, in sessions when adolescents are expressing relatively less CT (or more ST), substance use seems to be maintained at follow up periods indicating that NF may be counterproductive for individuals with less in-session CT. This is in line with prior research which posits that a discussion around NF may elicit more ST if it is the first time an adolescent has been presented with new information that contradicts their prior perceptions of their substance use (Osilla et al., 2015).

It is also possible that change talk marked initial treatment motivation rather than a mechanism activated by NF. That is, more highly motivated adolescents may not view feedback as negative, whereas more resistant adolescents may not believe NF or may view it as confrontational. We did not find strong associations between provision of NF and subsequent change talk in preliminary analyses, nor could we test transitional probabilities due to low base rates of NF across sessions. Thus, change talk in this study did not meet Nock, Janis, and Wedig’s, (2007) temporal order criterion in that we cannot be certain that it was prompted by NF. Additionally, it may be that there is a synergistic effect of providing NF within the context of an MI intervention.

This study’s results, however, mimic the positive findings of combining MI and NF for college students. Students that receive MI plus NF changed their normative perceptions of drinking (Walters & Neighbors, 2005; Walters, Vader, Harris, Field, & Jouriles, 2009), had higher CT (Vader et al., 2010) and had more positive drinking outcomes at follow up (Walters & Neighbors, 2005).

We did not find a significant effect for PCT on cannabis use outcomes or treatment engagement at 3 months. While our results are in line with other studies utilizing NF with college student cannabis users (Lee, Neighbors, Kilmer, & Larimer, 2010) it is unclear why client change language for adolescents receiving NF did not predict lower cannabis use. It may be that hearing feedback regarding cannabis use does not have a strong effect because the proportion of adolescents who view cannabis use as problematic has fallen over the past 10 years. For example, in 2014 only 16% of 12th graders believed occasional cannabis use to be harmful and 13% believed experimenting with cannabis to be dangerous (Miech, Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2015). In terms of treatment engagement, one explanation may lie in our inability to isolate client change language associated specifically with entering treatment after the assessment. That is, all CT statements, whether about alcohol use, cannabis use, or treatment engagement, were captured using a single code. Future studies may attempt to isolate CT or ST directly associated with treatment entry.

Overall, we found that when therapists used MI consistent behaviors (e.g. open questions, reflections) adolescent change talk increased. This finding is in concert with numerous studies showing that MI-consistent behaviors result in eliciting change talk from clients (D’Amico et al., 2015; Gaume et al., 2010; Magill et al., 2014; Moyers et al., 2007, 2009) and thus result in behavior change. We also found that when adolescents expressed CT it was more likely to be followed by more CT and, similarly, when adolescents expressed ST they were more likely to continue with ST. These data add to the growing literature on the importance of eliciting change talk from clients during MI sessions such that when a therapist or facilitator encounters ST it is important to avoid reflecting the ST and use other MI techniques such as a double sided reflection that ends in support for change side.

5. Conclusion and Limitations

Despite the study’s novelty and methodological vigor, some limitations remain. All participants in our sample were referred for a substance use treatment assessment. Therefore, the generalizability of our results may be limited to heavy-using adolescents. Further, therapists in this study were trained in MI, received ongoing supervision, and had high competency and therapist ratings. It may be useful for future research to examine the impact of NF on adolescent change language and subsequent substance use outcomes within a setting that has varying levels of MI competency. Further, our study was limited by a small sample size and a low frequency of NF statements by the therapists (approximately 1 per session). We were still limited in our models due to potential power issues (small sample size and use of secondary data analysis) to detect group effects on outcomes. Although this low frequency limited our ability to investigate transition probabilities following NF, this would be an important aspect to consider as it would give practitioners a more nuanced understanding of what happens immediately following NF for adolescents. Future research should investigate the impact of NF on client change language in other formats such as group treatment. Some adolescent group MI studies have found that when an individual produces ST the group is more likely to continue with ST (D’Amico et al., 2015). It may be that NF, when given to a group, may not resonate given that they are surrounded by individuals their own age. Experimenting with various types of NF such as group NF, gender specific norms (Neighbors et al., 2007), or grade specific norms may elicit different responses from adolescents regarding alcohol and cannabis use. Finally, our data were limited to the 3 month follow up; it may be useful to investigate longer term outcomes for adolescents.

Despite limitations, this study adds to the small literature on adolescent change talk and, further, is the first adolescent study to investigate the impact of NF on substance use outcomes. Findings support the use of NF for adolescents who have high PCT (or low proportion of ST) and support suppression of using NF for individuals with low PCT (or high proportion of ST) during a brief MI session. Practitioners familiar with MI can easily incorporate a short NF segment into an initial meeting with an adolescent or during a treatment assessment in attempts to improve alcohol use outcomes (Barnett et al., 2014a, 2014b).

Acknowledgments

This paper was supported by grants from the National Institute of Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse (K01AA021431 – PI: J.M. Houck) and (K23AA017702-PI: D.C. Smith).

Abbreviations

- CT

change talk

- ST

sustain talk

- MI

motivational interviewing

- NF

normative feedback

- PCT

percent change talk

References

- Aharonovich E, Amrhein PC, Bisaga A, Nunes EV, Hasin DS. Cognition, commitment language, and behavioral change among cocaine-dependent patients. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22(4):557–562. doi: 10.1037/a0012971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Missing data: Quantitative applications in the social sciences. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology. 2002;55(1):193–196. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Amrhein PC, Miller WR, Yahne CE, Palmer M, Fulcher L. Client commitment language during motivational interviewing predicts drug use outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(5):862–878. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apodaca TR, Borsari B, Jackson KM, Magill M, Longabaugh R, Mastroleo NR, Barnett NP. Sustain talk predicts poorer outcomes among mandated college student drinkers receiving a brief motivational intervention. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28(3):631–638. doi: 10.1037/a0037296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apodaca TR, Longabaugh R. Mechanisms of change in motivational interviewing: A review and preliminary evaluation of the evidence. Addiction. 2009;104(5):705–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02527.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins DC, Baldwin SA, Zheng C, Gallop RJ, Neighbors C. A tutorial on count regression and zero-altered count models for longitudinal substance use data. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27(1):166–177. doi: 10.1037/a0029508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Beadnell B, Garrett SB, Hartzler B, Wells EA, Peterson PL. Adolescent change language within a brief motivational intervention and substance use outcomes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22(4):570–575. doi: 10.1037/a0013022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Marlatt GA, Kivlahan DR, Fromme K, Larimer ME, Williams E. An experimental test of three methods of alcohol risk reduction with young adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60(6):974–979. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.6.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakeman R, McArthur D, Quera V, Robinson BF. Detecting sequential patterns and determining their reliability with fallible observers. Psychological Methods. 1997;2(4):357–370. [Google Scholar]

- Bakeman R, Quera V. General sequential querier (version 5.1) 2012 Retrieved from: http://www2.gsu.edu/~psyrab/gseq/Download.html.

- Barnett E, Moyers TB, Sussman S, Smith C, Rohrbach LA, Sun P, Spruijt-Metz D. From counselor skill to decreased marijuana use: Does change talk matter? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2014a;46(4):498–505. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett E, Spruijt-Metz D, Moyers TB, Smith C, Rohrbach LA, Sun P, Sussman S. Bidirectional relationships between client and counselor speech: The importance of reframing. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014b;28(4):1212–1219. doi: 10.1037/a0036227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett E, Sussman S, Smith C, Rohrbach LA, Spruijt-Metz D. Motivational interviewing for adolescent substance use: A review of the literature. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37(12):1325–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertholet N, Faouzi M, Gmel G, Gaume J, Daeppen J. Change talk sequence during brief motivational intervention, towards or away from drinking. Addiction. 2010;105(12):2106–2112. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Effects of a brief motivational intervention with college student drinkers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(4):728–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carcone AI, Naar-King S, Brogan KE, Albrecht T, Barton E, Foster T, Marshall S. Provider communication behaviors that predict motivation to change in black adolescents with obesity. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics : JDBP. 2013;34(8):599–608. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3182a67daf. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0b013e3182a67daf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti DV, Sparrow SA. Developing criteria for establishing interrater reliability of specific items: Applications to assessment of adaptive behavior. American Journal of Mental Deficiency. 1981;86(2):127–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins SE, Carey KB, Sliwinski MJ. Mailed personalized normative feedback as a brief intervention for at-risk college drinkers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63(5):559–567. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico EJ, Houck JM, Hunter SB, Miles JN, Osilla KC, Ewing BA. Group motivational interviewing for adolescents: Change talk and alcohol and marijuana outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2015;83(1):68–80. doi: 10.1037/a0038155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico EJ, Osilla KC, Miles JN, Ewing B, Sullivan K, Katz K, Hunter SB. Assessing motivational interviewing integrity for group interventions with adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26(4):994–1000. doi: 10.1037/a0027987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Titus JC, White MK, Unsicker JI, Hodgkins D. Global appraisal of individual needs: Administration guide for the GAIN and related measures. Bloomington, IL: Chestnut Health Systems; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff LA, McNeely M. Computer-enhanced primary care practitioner advice for high-risk college drinkers in a student primary health-care setting. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2001;7(1):82–100. [Google Scholar]

- Engle B, Macgowan MJ, Wagner EF, Amrhein PC. Markers of marijuana use outcomes within adolescent substance abuse group treatment. Research on Social Work Practice. 2010;20(3):271–282. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson SJ, Gerstle M, Feldstein SW. Brief interventions and motivational interviewing with children, adolescents, and their parents in pediatric health care settings: A review. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2005;159(12):1173–1180. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.12.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldstein SW, Ginsburg JI. Motivational interviewing with dually diagnosed adolescents in juvenile justice settings. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention. 2006;6(3):218–233. [Google Scholar]

- Garnick DW, Lee MT, Horgan CM, Acevedo A. Adapting Washington circle performance measures for public sector substance abuse treatment systems. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;36(3):265–277. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaume J, Bertholet N, Faouzi M, Gmel G, Daeppen J. Counselor motivational interviewing skills and young adult change talk articulation during brief motivational interventions. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2010;39(3):272–281. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaume J, Gmel G, Faouzi M, Daeppen J. Counsellor behaviours and patient language during brief motivational interventions: A sequential analysis of speech. Addiction. 2008;103(11):1793–1800. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaume J, Gmel G, Faouzi M, Daeppen J. Counselor skill influences outcomes of brief motivational interventions. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;37(2):151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynn LH, Hallgren KA, Houck JM, Moyers TB. CACTI: Free, open-source software for the sequential coding of behavioral interactions. PloS One. 2012;7(7):e39740. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW. Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:549–576. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S, Giannakopoulos E, Laing D, Williams NA. Psychological reactance: Effects of age and gender. The Journal of Social Psychology. 1994;134(2):223–228. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1994.9711385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houck JM, Hunter SB, Benson JG, Cochrum LL, Rowell LN, D’Amico EJ. Temporal variation in facilitator and client behavior during group motivational interviewing sessions. 2015 doi: 10.1037/adb0000107. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/adb0000107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Houck J, Moyers T, Miller W, Glynn L, Hallgren K. Manual for the motivational interviewing skill code (MISC) version 2.5. 2010. (Unpublished Manuscript) [Google Scholar]

- Johnston L. Monitoring the future: National results on adolescent drug use: 2012 overview of key findings on adolescent drug use. University of Michigan, Institute for Social Research; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston L, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2011. University of Michigan: Institute for Social Research; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2010. Volume I, secondary school students. University of Michigan: Institute for Social Research; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kaminer Y. Challenges and opportunities of group therapy for adolescent substance abuse: A critical review. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30(9):1765–1774. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight JR, Sherritt L, Harris SK, Gates EC, Chang G. Validity of brief alcohol screening tests among adolescents: A comparison of the AUDIT, POSIT, CAGE, and CRAFFT. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27(1):67–73. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000046598.59317.3A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Turner AP, Anderson BK, Fader JS, Kilmer JR, Palmer RS, Cronce JM. Evaluating a brief alcohol intervention with fraternities. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62(3):370–380. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CM, Neighbors C, Kilmer JR, Larimer ME. A brief, web-based personalized feedback selective intervention for college student marijuana use: A randomized clinical trial. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24(2):265–273. doi: 10.1037/a0018859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord SP, Can D, Yi M, Marin R, Dunn CW, Imel ZE, … Atkins DC. Advancing methods for reliably assessing motivational interviewing fidelity using the motivational interviewing skills code. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2015;49:50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magill M, Apodaca TR, Barnett NP, Monti PM. The route to change: Within-session predictors of change plan completion in a motivational interview. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2010;38(3):299–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magill M, Gaume J, Apodaca TR, Walthers J, Mastroleo NR, Borsari B, Longabaugh R. The technical hypothesis of motivational interviewing: A meta-analysis of MI’s key causal model. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014;82(6):973–983. doi: 10.1037/a0036833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Dimeff LA, Larimer ME, Quigley LA, … Williams E. Screening and brief intervention for high-risk college student drinkers: Results from a 2-year follow-up assessment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66(4):604–615. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.4.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin T, Christopher PJ, Houck JM, Moyers TB. The structure of client language and drinking outcomes in project match. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011;25(3):439–445. doi: 10.1037/a0023129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miech RA, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2014: Volume I, secondary school students. The University of Michigan: Institute for Social Research; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Helping people change. 3. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rose GS. Toward a theory of motivational interviewing. American Psychologist. 2009;64(6):527–537. doi: 10.1037/a0016830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T. Therapist influence on client language during motivational interviewing sessions. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;30(3):245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T, Christopher PJ, Houck JM, Tonigan JS, Amrhein PC. Client language as a mediator of motivational interviewing efficacy: Where is the evidence? Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31(s3):40s–47s. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T, Houck JM, Christopher PJ, Tonigan JS. From in-session behaviors to drinking outcomes: A causal chain for motivational interviewing. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(6):1113–1124. doi: 10.1037/a0017189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers T, Martin T, Manuel J, Miller W, Ernst D. Revised global scales: Motivational interviewing treatment integrity 3.1. 1 (MITI 3.1. 1) Albuquerque: Center on Alcoholism, Substance Abuse and Addictions, University of New Mexico; 2010. Unpublished Manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Benson TA, Vuchinich RE, Deskins MM, Eakin D, Flood AM, … Torrealday O. A comparison of personalized feedback for college student drinkers delivered with and without a motivational interview. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65(2):200–203. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide: Seventh edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Naar-King S, Suarez M. Motivational interviewing with adolescents and young adults. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Neal DJ, Carey KB. Developing discrepancy within self-regulation theory: Use of personalized normative feedback and personal strivings with heavy-drinking college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29(2):281–297. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lee CM, Lewis MA, Fossos N, Larimer ME. Are social norms the best predictor of outcomes among heavy-drinking college students? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68(4):556–565. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lewis MA, Atkins DC, Jensen MM, Walter T, Fossos N, Larimer ME. Efficacy of web-based personalized normative feedback: A two-year randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78(6):898–911. doi: 10.1037/a0020766. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0020766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Janis IB, Wedig MM. In: Evidence-based outcome research: A practical guide to conducting randomized controlled trials for psychosocial interventions. Nezu AM, Nezu Cm, editors. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Osilla KC, Ortiz JA, Miles JN, Pedersen ER, Houck JM, D’Amico EJ. How group factors affect adolescent change talk and substance use outcomes: Implications for motivational interviewing training. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2015;62(1):79–86. doi: 10.1037/cou0000049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen ER, Miles JN, Ewing BA, Shih RA, Tucker JS, D’Amico EJ. A longitudinal examination of alcohol, marijuana, and cigarette perceived norms among middle school adolescents. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;133(2):647–653. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31(4):437–448. [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. Treatment episode data set (TEDS): 2002–2012. national admissions to substance abuse treatment services. (No. BHSISSeries S-71, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4850) Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(2):147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih RA, Miles JN, Tucker JS, Zhou AJ, D’Amico EJ. Racial/Ethnic differences in the influence of cultural values, alcohol resistance self-efficacy, and alcohol expectancies on risk for alcohol initiation. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26(3):460–470. doi: 10.1037/a0029254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DC. Delivering motivational feedback with motivational feedback following the GAIN-Q3 administration: The CHOICE model. In: Titus JC, Feeney T, Smith DC, Rivers TL, Kelly LL, Dennis ML, editors. GAIN-Q: Administration, clinical interpretation, and brief intervention manual. Normal, IL: Chestnut Health Systems; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Smith DC, Davis JP, Ureche DJ, Tabb KM. Normative feedback and adolescent readiness to change: A small randomized pilot trial. Research on Social Work Practice. 2015;25(7):801–814. doi: 10.1177/1049731514535851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DC, Hall JA. Strengths-oriented referrals for teens (SORT): Giving balanced feedback to teens and families. Health and Social Work. 2007;32(1):69. doi: 10.1093/hsw/32.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DC, Hall JA, Jang M, Arndt S. Therapist adherence to a motivational-interviewing intervention improves treatment entry for substance-misusing adolescents with low problem perception. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70(1):101–105. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DC, Ureche DJ, Davis JP, Walters ST. Motivational interviewing with and without normative feedback for adolescents with substance use problems: A preliminary study. Substance Abuse. 2015;36:350–358. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2014.988838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Measuring alcohol consumption. New York, NY: Springer; 1992. Timeline follow-back; pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Spirito A, Sindelar-Manning H, Colby SM, Barnett NP, Lewander W, Rohsenow DJ, Monti PM. Individual and family motivational interventions for alcohol-positive adolescents treated in an emergency department: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2011;165(3):269–274. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titus JC, Feeney T, Smith DC, Rivers TL, Kelly LL, Dennis ML, Center GC. GAIN Q3 3.1 administration, clinical interpretation, and brief intervention. Normal, IL: Chestnut Health Systems; 2012a. [Google Scholar]

- Titus JC, Smith DC, Dennis ML, Ives M, Twanow L, White MK. Impact of a training and certification program on the quality of interviewer-collected self-report assessment data. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2012b;42(2):201–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vader AM, Walters ST, Prabhu GC, Houck JM, Field CA. The language of motivational interviewing and feedback: Counselor language, client language, and client drinking outcomes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24(2):190–197. doi: 10.1037/a0018749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker DD, Neighbors C, Rodriguez LM, Stephens RS, Roffman RA. Social norms and self-efficacy among heavy using adolescent marijuana smokers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011a;25(4):727–732. doi: 10.1037/a0024958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker DD, Roffman RA, Stephens RS, Wakana K, Berghuis J. Motivational enhancement therapy for adolescent marijuana users: A preliminary randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74(3):628–632. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker D, Stephens R, Rowland J, Roffman R. The influence of client behavior during motivational interviewing on marijuana treatment outcome. Addictive Behaviors. 2011b;36(6):669–673. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters ST, Bennett ME. Addressing drinking among college students: A review of the empirical literature. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2000;18(1):61–77. [Google Scholar]

- Walters ST, Neighbors C. Feedback interventions for college alcohol misuse: What, why and for whom? Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30(6):1168–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters ST, Vader AM, Harris TR. A controlled trial of web-based feedback for heavy drinking college students. Prevention Science. 2007;8(1):83–88. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters ST, Vader AM, Harris TR, Field CA, Jouriles EN. Dismantling motivational interviewing and feedback for college drinkers: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(1):64–73. doi: 10.1037/a0014472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters ST, Woodall WG. Mailed feedback reduces consumption among moderate drinkers who are employed. Prevention Science. 2003;4(4):287–294. doi: 10.1023/a:1026024400450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters KC, Fahnhorst T, Botzet A, Lee S, Lalone B. Brief intervention for drug-abusing adolescents in a school setting: Outcomes and mediating factors. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2012;42(3):279–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]