Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Telemedicine, the use of telecommunications to deliver health services, expertise and information, is a promising but unproven tool for improving the quality of diabetes care. We summarized the effectiveness of different methods of telemedicine for the management of diabetes compared with usual care.

METHODS:

We searched MEDLINE, Embase and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials databases (to November 2015) and reference lists of existing systematic reviews for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing telemedicine with usual care for adults with diabetes. Two independent reviewers selected the studies and assessed risk of bias in the studies. The primary outcome was glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C) reported at 3 time points (≤ 3 mo, 4–12 mo and > 12 mo). Other outcomes were quality of life, mortality and episodes of hypoglycemia. Trials were pooled using randomeffects meta-analysis, and heterogeneity was quantified using the I2 statistic.

RESULTS:

From 3688 citations, we identified 111 eligible RCTs (n = 23 648). Telemedicine achieved significant but modest reductions in HbA1C in all 3 follow-up periods (difference in mean at ≤ 3 mo: −0.57%, 95% confidence interval [CI] −0.74% to −0.40% [39 trials]; at 4–12 mo: −0.28%, 95% CI −0.37% to −0.20% [87 trials]; and at > 12 mo: −0.26%, 95% CI −0.46% to −0.06% [5 trials]). Quantified heterogeneity (I2 statistic) was 75%, 69% and 58%, respectively. In meta-regression analyses, the effect of telemedicine on HbA1C appeared greatest in trials with higher HbA1C concentrations at baseline, in trials where providers used Web portals or text messaging to communicate with patients and in trials where telemedicine facilitated medication adjustment. Telemedicine had no convincing effect on quality of life, mortality or hypoglycemia.

INTERPRETATION:

Compared with usual care, the addition of telemedicine, especially systems that allowed medication adjustments with or without text messaging or a Web portal, improved HbA1C but not other clinically relevant outcomes among patients with diabetes.

Diabetes is one of the most common chronic diseases worldwide and is associated with premature death and disability. Over the past 3 decades, the prevalence of diabetes has more than doubled globally1 and is projected to rise further from 382 million in 2013 to 592 million in 2035.2 Optimal glycemic control helps to prevent and reduce complications of diabetes, including cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, blindness, neuropathy and limb amputation.3,4 However, maintaining optimal glycemic control is challenging.5

Telemedicine is the use of telecommunications to deliver health services, including interactive, consultative and diagnostic services.6 Telemedicine interventions for diabetes can range from simple reminder systems via text messaging to complex Web interfaces through which patients can upload their glucose levels measured with a home meter and other pertinent data such as medications, dietary habits, activity level and medical history. Providers can review the data and provide feedback regarding medication adjustments and lifestyle modifications. Telemedicine has previously been shown to have clinical benefits for patients with severe asthma,7 chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,8 hypertension9 or chronic heart failure.10 It may also be helpful for providing care to people with diabetes, especially those unable to travel to health care facilities owing to large distances or disabilities. In particular, telemedicine may facilitate self-management, an important potential objective in diabetes care.11,12

Previous reviews describing the effect of telemedicine on the management of diabetes have been published.13–31 However, some focused on only specific types of telemedicine (e.g., telemonitoring20,23,26) or interventions delivered only by telephone.16,17,23,31 Given that this is a rapidly developing field, a large number of additional clinical trials have recently been published, which suggests the value of an updated review. We did a systematic review and quantitative synthesis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing the impact of different methods of telemedicine with usual care on glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C) and health-related quality of life in people with diabetes mellitus.

Methods

We performed a systematic review of RCTs that compared telemedicine with usual care for the management of diabetes (type 1 and type 2). The review was reported according to an accepted guideline. 32 We followed a written but unregistered protocol.

We included studies if they were RCTs (parallel, cluster or crossover); were published in English; enrolled adult patients with diabetes; compared telemedicine (some electronic form of provider-to-patient communication) with usual care; and reported the degree of metabolic control measured by HbA1C level. We excluded studies on gestational diabetes because of the different nature of the disease. We considered peer-reviewed full-text articles published until November 2015.

Literature search

The search strategy was designed by an expert librarian. We searched the following electronic databases through the Ovid interface: MEDLINE (1946–November 2015), Embase (1974–November 2015) and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (November 2015). We also performed manual searches of the reference lists of existing systematic reviews. Because telemedicine is a broad term that can cover different interventions, we included all electronic forms of communication in our search. The search strategies are shown in Table A1 in Appendix 1 (available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.150885/-/DC1). Results of the search were transferred to Endnote software and were checked for duplicates.

Study selection

Two reviewers (N.W. and L.F.) independently screened the titles and abstracts of all unique citations. Studies with “diabetes,” “type 1” or “type 2” in the title or abstract that studied any kind of telemedicine intervention were selected for full-text review. Two independent reviewers (L.F. and a research assistant) assessed them using an inclusion/exclusion form based on a priori selection criteria for eligibility. Disagreements between the reviewers were resolved by meeting with a third reviewer (N.W.).

Data extraction

We used a standardized method to extract and record relevant properties of each trial into a database. Data from eligible trials were extracted by 1 reviewer (L.F.) and checked by another reviewer (Y.L.) using a standardized extraction sheet. We resolved disagreements by discussion.

We extracted the following information from selected studies: trial characteristics (study name, year of publication, country, study design, duration and sample size); patient characteristics (age, sex, type of diabetes, diabetes duration, blood pressure, cholesterol, body mass index [BMI], smoking status and medications [insulin, oral hypoglycemic agents, lipid-lowering therapy]); telemedicine interventions; and outcomes.

We classified the telemedicine interventions by (a) form of communication from patient to provider, (b) form of communication from provider to patient, (c) type of provider (nurse, physician, allied health professional, clinical decision support system), (d) frequency of contact and (e) characteristics of any intervention. Forms of communication between provider and patient included telephone, smartphone application, email, text messaging (short message service [SMS]), Web portal (websites where patients upload blood glucose levels or other clinical data and share these with their health care providers, with or without provider-to-patient communication) and “smart” device or glucometer (any computerized device specifically developed to collect and transmit patients’ data to health care providers). Characteristics of any intervention included medication adjustment, exercise, general education about diabetes, blood pressure management and nutritional intervention.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was HbA1C level. Secondary outcomes were quality of life as measured by a validated instrument, mortality and incidence of hypoglycemia. Hypoglycemic events were classified as severe if they were reported as such or if they required assistance.

Risk-of-bias assessment

We assessed risk of bias using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool33 and included other items (funding, intention to treat and interim analysis) also known to be associated with bias.34–40 Two reviewers (L.F. and a research assistant) assessed the trials independently and resolved any disagreements by meeting with a third reviewer (N.W.).

Data synthesis and analysis

We used Stata 13 (StataCorp) for all statistical analyses. We used the difference in means (MD) to pool continuous outcomes, and the risk ratio or the risk difference (when the events were rare) to pool dichotomous outcomes. Because of the differences expected between trials, we combined results using a random-effects model.41 We imputed missing standard deviations by substituting the baseline value from the same intervention group whenever possible; otherwise the median value from the systematic review was substituted.42 We pooled outcomes using 3 categories of time points (≤ 3 mo, 4–12 mo and > 12 mo). Dichotomous outcomes of HbA1C were pooled by the floored threshold value (e.g., < 6%, < 7%, < 8%, < 9%). We reported results from a quality-of-life instrument when data from at least 2 trials could be pooled. Heterogeneity was identified by visual inspection of the forest plots and by quantifying I2 statistic.43 We assessed publication bias using the Egger test44 and by visual inspection of the contour-enhanced funnel plot.45

We planned a priori to examine the association between population characteristics, intervention characteristics, risk-of-bias items (as specified earlier) and the effect of telemedicine on HbA1C for characteristics reported in 5 or more trials. We did univariable weighted (with the inverse of the trial variance) linear meta-regression to evaluate for effect modification on HbA1C at 4–12 months.46 In a post hoc analysis, we examined whether adjustment for potential confounders in the trial-level results modified the effect of telemedicine on HbA1C.

Results

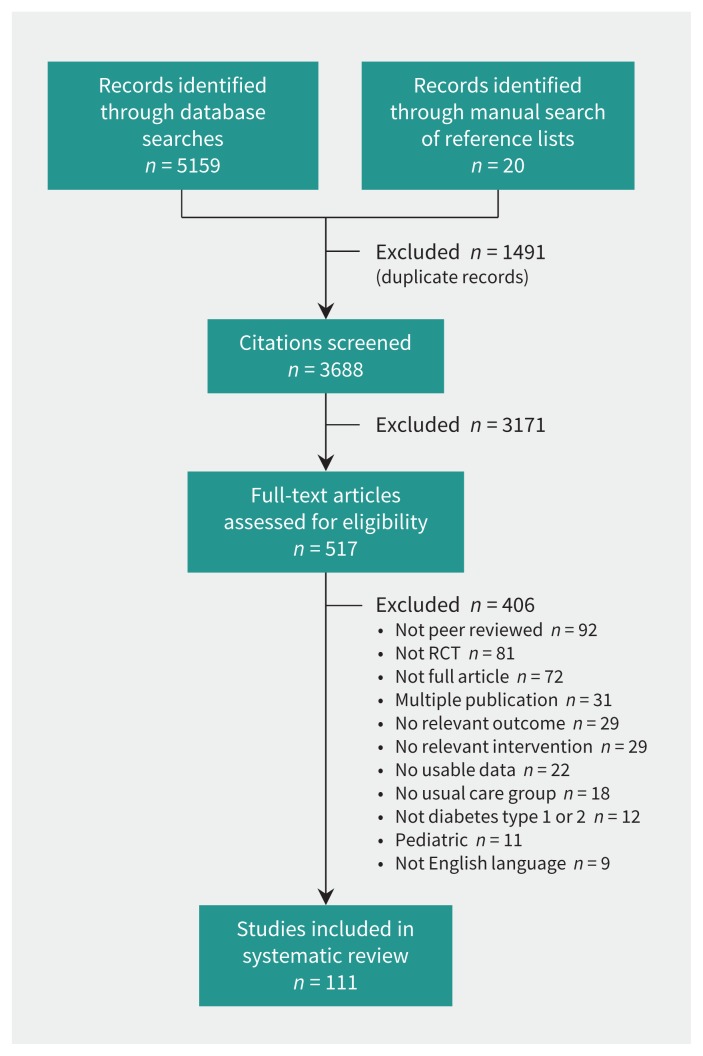

Our literature search identified 3688 unique citations. After the screening of titles and abstracts, 517 potentially eligible studies were identified, of which 111 trials21,47–156 met our inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Disagreements occurred with 7% of the articles (κ value = 0.82).

Figure 1:

Selection of trials for analysis. RCT = randomized controlled trial.

Characteristics of the trials are summarized in Table 1 (see end of article). Of the 111 included trials, 4 were published before 2000. Five were cluster RCTs, 3 were crossover trials, and the remainder were parallel RCTs. Forty-one trials (37%) were done in the United States, 14 (13%) in Korea and 7 (6%) each in Canada and Australia; 6 or fewer were done in each of the remaining countries.

Table 1:

Trial and population characteristics by type of diabetes

| Type of diabetes; study | Country | RCT design | Sample size | Duration of follow-up, mo | Mean age, yr | Male, % | Mean duration of diabetes, yr | Mean baseline HbA1C | Mean BMI | % using insulin | % using OHA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type 1 diabetes | |||||||||||

| Esmatjes,68 2014 | Spain | Parallel | 154 | 6 | 32 | 45 | 17.2 | 9.2 | 25 | 100 | – |

| Suh,137 2014 | Korea | Parallel | 57 | 3 | 33 | 37 | 7.4 | 9.5 | 23 | 100 | 0 |

| Kirwan,99 2013 | Australia | Parallel | 72 | 9 | 35 | 39 | 18.9 | 8.8 | – | 100 | – |

| Rossi,130 2013 | Italy | Parallel | 127 | 6 | 36 | 48 | 15.6 | 8.5 | 24 | 100 | – |

| Charpentier,60 2011 | France | Parallel | 120 | 6 | 34 | 36 | 15.8 | 9.0 | 25 | 100 | – |

| Rossi,129 2010 | Italy, Spain, UK | Parallel | 130 | 6 | 36 | 43 | 16.5 | 8.3 | – | 100 | – |

| McCarrier,108 2009 | US | Parallel | 78 | 12 | 37 | 67 | – | 8.0 | – | 100 | – |

| Benhamou,53 2007 | France | Crossover | 31 | 12 | 41 | 50 | 24.0 | 8.3 | 24 | 100 | – |

| Jansa,86 2006 | Spain | Parallel | 40 | 12 | 25 | 50 | 11.0 | 8.7 | 23 | 100 | – |

| Farmer,69 2005 | UK | Parallel | 93 | 9 | 24 | 59 | 12.5 | 9.2 | 25 | 100 | – |

| Montori,21 2004 | US | Parallel | 31 | 6 | 43‡ | 32 | 17.1‡ | 8.9 | 26‡ | 100 | – |

| Gomez,78 2002 | Spain | Crossover | 10 | 6 | 32 | 20 | 13.8 | 8.3‡ | – | 100 | – |

| Ahring,47 1992 | Canada | Parallel | 42 | 3 | 41 | 48 | 11.6 | 10.9 | – | 100 | – |

| Type 2 diabetes | |||||||||||

| Nicolucci,115 2015 | Italy | Parallel | 302 | 12 | 58 | 62 | 8.5 | 8.0 | 29 | 9 | 100 |

| Rasmussen,127 2015 | Denmark | Parallel | 40 | 6 | 63 | 68 | 9.4 | 8.5 | 31 | 38 | – |

| Shahid,132 2015 | Pakistan | Parallel | 440 | 4 | 49 | 61 | – | 10.0 | 27 | – | – |

| Arora,50 2014 | US | Parallel | 128 | 6 | 38 | 23 | – | 10.0 | – | ≤ 80 | ≤ 80 |

| Chan,59 2014 | China | Parallel | 628 | 12 | 55 | 57 | 9.4 | 8.2 | 27 | 35 | 85 |

| Heisler,82 2014 | US | Parallel | 188 | 3 | 52 | 29 | 9.1 | 8.3 | – | 43 | 79 |

| Luley,104 2014 | Germany | Parallel | 68 | 6 | 58 | 49 | – | 7.6 | 35 | 31 | ≥ 68 |

| Lynch,105 2014 | US | Parallel | 61 | 6 | 54 | 33 | 8.7 | 7.6 | 36 | 43 | 82 |

| Pressman,123 2014 | US | Parallel | 225 | 6 | 56 | 62 | – | 9.3 | 35 | – | – |

| Steventon,135 2014 | UK | Cluster | 513 | 12 | 65 | 58 | – | 8.4 | 31 | 48 | ≥ 73 |

| Varney,144 2014 | Australia | Parallel | 94 | 12 | 62 | 68 | 12.9 | 8.4 | 31 | 58 | ≥ 75 |

| Waki,146 2014 | Japan | Parallel | 54 | 3 | 57 | 76 | 9.1 | 7.1 | – | 15 | 61 |

| Zhou,156 2014 | China | Parallel | 114 | 3 | – | – | – | 8.3 | 24 | – | – |

| Aliha,48 2013 | Iran | Parallel | 62 | 3 | 53 | – | 8.7 | 9.7 | 28 | – | – |

| Blackberry,55 2013 | Australia | Cluster | 473 | 18 | 63 | 57 | 10‡ | 8.1 | 12% < 25 | 24 | 90 |

| Crowley,63 2013 | US | Parallel | 359 | 12 | 56 | 28 | – | 8.0 | – | 51 | – |

| Eakin,67 2013 | Australia | Parallel | 302 | 6 | 58 | 56 | 5.0‡ | 7.1‡ | 33 | 14 | 81 |

| Gagliardino,74 2013 | Argentina | Parallel | 198 | 12 | 61 | 49 | 6.0 | 7.2 | 33 | – | 91 |

| Mons,111 2013 | Germany | Parallel | 204 | 18 | 68‡ | 61 | 9.0‡ | 8.1‡ | – | – | – |

| Nagrebetsky,113 2013 | UK | Parallel | 17 | 6 | 58 | 71 | 2.6‡ | 8.1 | 33 | 0 | 100 |

| Orsama,117 2013 | Finland | Parallel | 56 | 10 | 62 | 54 | – | 7.0 | 32 | – | – |

| Plotnikoff,122 2013 | Canada | Parallel | 190 | 18 | 62 | 51 | 9.3 | 7.1 | 30 | 18 | – |

| Tang,138 2013 | US | Parallel | 415 | 12 | 54 | 60 | – | 9.3 | – | – | – |

| Van Dyck,143 2013 | Belgium | Parallel | 92 | 12 | 62 | 69 | – | 7.3 | 30 | ≥ 44 | ≥ 44 |

| Bogner,56 2012 | US | Parallel | 182 | 3 | 58 | 32 | 11.2 | 7.1 | – | – | 100 |

| Del Prato,66 2012 | Italy | Parallel | 291 | 11 | 58 | 52 | 10.9 | 7.8 | 30 | 6 | 100 |

| Glasgow,75 2012 | US | Parallel | 463 | 12 | 58 | 50 | – | 8.1 | 35 | – | – |

| Goodarzi,79 2012 | Iran | Parallel | 100 | 3 | 54 | 22 | 8.0‡ | 7.9 | 28 | 41 | 65 |

| Jarab,87 2012 | Jordan | Parallel | 171 | 6 | 64 | 57 | 9.9 | 8.4‡ | 33‡ | 68 | – |

| Marois,107 2012 | Australia | Parallel | 39 | 6 | 63 | 53 | – | 7.7 | 33 | 17 | 77 |

| Pacaud,118 2012 | Canada | Parallel | 79 | 12 | 54 | 48 | – | 7.1 | – | – | – |

| Patja,119 2012 | Finland | Cluster | 1129† | 12 | 65 | 57 | 10.0 | 7.6 | 32 | 29 | 45 |

| Williams,151 2012 | Australia | Parallel | 120 | 6 | 57 | 63 | – | 8.8 | 34‡ | 43 | – |

| Avdal,51 2011 | Turkey | Parallel | 122 | 6 | 52 | 49 | – | 8.1 | – | 100 | – |

| Carter,58 2011 | US | Parallel | 74 | 9 | 51 | 36 | – | 8.9 | 36 | – | – |

| Cho,62 2011 | Korea | Parallel | 79 | 6 | 50 | 66 | 3.5 | 6.8 | 24 | 33 | 84 |

| Farsaei,71 2011 | Iran | Parallel | 172 | 3 | 53 | 34 | 10.6 | 9.1 | – | 43 | 88 |

| Franciosi,72 2011 | Italy | Parallel | 62 | 6 | 49 | 74 | 3.4 | 7.9 | 31 | 0 | 100 |

| Frosch,73 2011 | US | Parallel | 201 | 6 | 55 | 52 | 10.0 | 9.6 | 33 | – | – |

| Keogh,90 2011 | Ireland | Parallel | 121 | 6 | 59 | 64 | 9.4 | 9.2 | 32 | 52 | 47 |

| Kim,94 2011 | Korea | Parallel | 54 | 4 | 56 | 62 | 8.9 | 7.4 | 26 | – | 100 |

| Lim,102 2011 | Korea | Parallel | 103 | 6 | 68 | 41 | 14.8 | 7.9 | 25 | 30 | > 62 |

| Quinn,125 2011 | US | Cluster | 213 | 12 | 53 | 50 | 8.1 | 9.4 | 36 | – | – |

| Shetty,134 2011 | India | Parallel | 215 | 12 | 50 | – | – | 9.0 | 28 | – | – |

| Tildesley,140 2011 | Canada | Parallel | 50 | 12 | 60 | 63 | 19.0 | 8.7 | 33 | 100 | – |

| Wakefield,145 2011 | US | Parallel | 302 | 12 | 68 | 98 | – | 7.2 | 33 | – | – |

| Anderson,49 2010 | US | Parallel | 295 | 12 | 35 | 42 | – | 8.0 | 35 | – | – |

| Davis,65 2010 | US | Parallel | 165 | 12 | 60 | 25 | 9.4 | 9.1 | 37 | 50 | 78 |

| Farsaei,70 2010 | Iran | Parallel | 174 | 3 | 53 | 34 | 10.6 | 9.1 | – | 43 | 88 |

| Heisler,83 2010 | US | Parallel | 245 | 6 | 62 | 100 | – | 8.0 | – | 56 | 44 |

| Kim,95 2010 | Korea | Parallel | 100 | 3 | 48 | 50 | 8.5 | 9.8 | 24 | 21 | 97 |

| Lorig,103 2010 | US | Parallel | 761 | 18 | 54 | 27 | – | 6.4 | – | – | – |

| Nesari,114 2010 | Iran | Parallel | 61 | 3 | 52 | 28 | 28% > 10 yr | 9.0 | 28 | 0 | 100 |

| Stone,136 2010 | US | Parallel | 150 | 6 | 59‡ | 99 | – | 9.5 | – | 58 | 76 |

| Tildesley,141 2010 | Canada | Parallel | 50 | 6 | 59 | 62 | 18.8 | 8.7 | 33 | 100 | – |

| Dale,64 2009 | UK | Parallel | 231 | 6 | 51–69‡ | 47 | 1–15‡ | 8.6 | – | 0 | – |

| Graziano,80 2009 | US | Parallel | 120 | 3 | 62 | 55 | 12.9 | 8.7 | – | 54 | – |

| Holbrook,84 2009 | Canada | Parallel | 511 | 6 | 61 | 51 | 9.3 | 7.1 | 32 | 17 | > 53 |

| Ralston,126 2009 | US | Parallel | 83 | 12 | 57 | 51 | – | 8.1 | – | 39 | – |

| Rodriguez-Idigoras,128 2009 | Spain | Parallel | 328 | 12 | 64 | 52 | 10.7 | 7.5 | 78% > 27 | 38 | 73 |

| Schillinger,131 2009 | US | Parallel | 226 | 12 | 56 | 43 | 9.8 | 9.6 | 31 | 37 | 88 |

| Yoo,153 2009 | Korea | Parallel | 123 | 3 | 58 | 59 | 6.6 | 7.5 | 26 | – | – |

| Kim,98 2008 | Korea | Parallel | 40 | 12 | 47 | 47 | 6.2 | 7.9 | 25 | 32 | 68 |

| Quinn,124 2008 | US | Parallel | 30 | 3 | 51 | 35 | 9.3 | 9.3 | 34 | 31 | 38 |

| Yoon,154 2008 | Korea | Parallel | 60 | 12 | 47 | 43 | 6.6 | 7.8 | 24 | 31 | 69 |

| Kim,92 2007 | Korea | Parallel | 80 | 3 | 48 | 65 | 7.8 | – | – | – | – |

| Kim,96 2007 | Korea | Parallel | 60 | 6 | 47 | 43 | 6.6 | 7.8 | 24 | 8 | 69 |

| Cho,61 2006 | Korea | Parallel | 80 | 30 | 53 | 61 | 6.8 | 7.6 | 23 | 23 | 79 |

| Kim,93 2006 | Korea | Parallel | 51 | 3 | 55 | 53 | 7.3 | 7.9 | – | 0 | 65 |

| Glasgow,77 2005 | US | Cluster | 886 | 12 | 63 | 49 | – | 7.3 | – | – | – |

| Young,155 2005 | UK | Parallel | 591 | 12 | 67 | 58 | 6.0 | 7.9 | 30 | 21 | 55 |

| Kwon,100 2004 | Korea | Parallel | 110 | 3 | 54 | 61 | 6.8 | 7.4 | 24 | – | – |

| Wolf,152 2004 | US | Parallel | 147 | 12 | 53 | 40 | – | 7.7 | 38 | 24 | > 64 |

| Kim,97 2003 | Korea | Parallel | 50 | 3 | 60 | 30 | 13.7 | 8.5 | 25 | 41 | 68 |

| Whitlock,149 2000 | US | Parallel | 28 | 3 | 60 | 57 | – | 9.5 | – | – | – |

| Weinberger,148 1995 | US | Parallel | 275 | 12 | 64 | 99 | 11.2 | 10.7 | – | 47 | – |

| Mixed type | |||||||||||

| Kaur,89 2015 | India | Parallel | 80 | 3 | 50 | 54 | 5.5 | 7.9 | 29 | 8 | 89 |

| Leichter,101 2013 | US | Parallel | 98 | 12 | 48 | 56 | – | 7.5 | 33 | 65 | 58 |

| Munshi,112 2013 | US | Parallel | 100 | 12 | 75 | 46 | 21.0 | 9.2 | 32 | 89 | 52 |

| Bell,52 2012 | US | Parallel | 65 | 12 | 58 | 55 | 13.0 | 9.3 | 34 | > 44 | > 53 |

| Williams,150 2012 | Australia | Parallel | 80 | 12 | 67 | 56 | – | 7.5‡ | 32 | – | – |

| Istepanian,85 2009 | UK | Parallel | 137 | 9 | 59 | – | 12.5 | 8.0 | – | 42 | 68 |

| Bond,57 2007 | US | Parallel | 62 | 6 | 67 | 55 | 17.0 | 7.1 | – | 94 | 45 |

| Harno,81 2006 | Finland | Parallel | 175 | 12 | – | – | – | 8.0 | 28 | – | – |

| Maljanian,106 2005 | US | Parallel | 507 | 12 | 58 | 47 | – | 7.9 | 32 | – | – |

| Glasgow,76 1997 | US | Parallel | 98 | 12 | 62 | 38 | 13.3 | 7.9 | 30 | 67 | – |

| Type unknown | |||||||||||

| Katalenich,88 2015 | US | Parallel | 98 | 6 | – | 40 | – | 8.3 | – | 100 | 79 |

| Khanna,91 2014 | US | Parallel | 75 | 3 | 52 | 59 | – | 9.1 | 34 | 33 | 90 |

| O’Connor,116 2014 | US | Parallel | 2378 | 12 | 40–64‡ | 48 | – | 9.8 | – | – | – |

| Moattari,110 2013 | Iran | Parallel | 52 | 3 | 23 | 43 | – | 9.3 | – | 100 | – |

| Walker,147 2011 | US | Parallel | 527 | 12 | 56 | 33 | 9.2 | 8.6‡ | 31 | 23 | 100 |

| Shea,133 2009 | US | Parallel | 1665 | 60 | 71 | 37 | 11.1 | 7.4 | 32 | 30 | 80 |

| McMahon,109 2005 | US | Parallel | 104 | 12 | 64 | 100 | 12.3 | 10.0 | 33 | 49 | 51 |

| Biermann,54 2002 | Germany | Parallel | 48 | 8 | 30 | – | 9.9 | 8.2 | – | 100 | – |

| Piette,120 2001 | US | Parallel | 292 | 12 | 61 | 97 | – | 8.2 | 31 | 35 | 100 |

| Tsang,142 2001 | Hong Kong | Crossover | 20 | 6 | 33 | 64 | 8.6 | 8.7 | 24 | – | – |

| Piette,121 2000 | US | Parallel | 280 | 12 | 55 | 42 | – | 8.7 | 34 | 38 | 100 |

| Thompson,139 1999 | Canada | Parallel | 46 | 6 | 49 | 48 | 17.0 | 9.5 | – | 100 | – |

Note: BMI = body mass index, HbA1C = glycated hemoglobin, OHA = oral hypoglycemic agents, RCT = randomized controlled trial, “–” = not reported.

The trials are ordered by type of diabetes, year and author.

Only the diabetes subgroup is reported for Patja 2012.119

Median.

The median number of study participants was 114 (range 10–2378) (Table 1). The median mean age at baseline was 56 years, and the median mean BMI at baseline was 31. The range of metabolic control at baseline varied substantially between trials (mean HbA1C 6.4%–10.9%); however, the mean HbA1C level in 71 (64%) of the trials was 8% or greater at baseline.

The telemedicine interventions varied in a number of ways between the trials (Table 2 [see end of article]). Patients initiated communication with their health care providers in 3 ways: voice, text messaging and transmission of data. The trials used a large variety of platforms: Web portal (24%), customized “smart” device (14%), telephone for communication to provider (13%), smartphone application (8%), SMS (5%), email (3%), personal digital assistant (2%), automated voice reminder system (1%), computer software (1%), fax (1%), listserv (electronic mailing list to send group emails; 1%), customized patient-specific Web page (1%) or a call-me button (1%).

Table 2:

Telemedicine interventions

| Study* (subgroup) | Provider | Form of communication | Frequency of feedback | Interactive follow-up | Medication adjustment | Nutrition counselling | Exercise | Blood pressure management | General education | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provider to patient | Patient to provider | |||||||||

| Zhou,156 2014 | Diabetes team | Web portal SMS Telephone |

Web portal | – | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | – | – |

| Kirwan,99 2013 | Diabetes educator | Web portal | SMS Smartphone application |

Weekly | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | – | Yes |

| Moattari,110 2013 | Nurse Physician Nutritionist |

Web portal SMS |

Web portal SMS Telephone |

Weekly | Yes | – | Yes | – | – | Yes |

| Orsama,117 2013 | CDSS | Web portal (CDSS) | Web portal Smartphone application Telephone |

– | Yes | – | – | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Pacaud,118 2012 (Web static) | Diabetes educator Physician |

Web portal (email) | Web portal (email) | – | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | Yes |

| Pacaud,118 2012 (Web Interactive) | Diabetes educator Physician |

Web portal (email, chat, bulletin board) | Web portal (email, chat, bulletin board) | – | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | Yes |

| Avdal,51 2011 | Nurse | Web portal | Web portal | – | Yes | – | – | – | – | Yes |

| Carter,58 2011 | Nurse Physician |

Web portal Videoconference |

Web portal Smart device |

Every 2 wk | Yes | – | – | – | – | Yes |

| Cho,62 2011 | CDSS Nurse Physician |

Web portal | Web portal | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Quinn,125 2011 (coach only) | CDSS Diabetes educator |

Web portal | Web portal Smartphone application Telephone |

– | Yes | – | – | – | – | Yes |

| Quinn,125 2011 (coach PCP portal) | CDSS Diabetes educator Physician |

Web portal | Web portal Smartphone application Telephone |

– | Yes | – | – | – | – | Yes |

| Quinn,125 2011 (coach PCP portal with decision support) | CDSS Diabetes educator Physician |

Web portal | Web portal (with decision support) Smartphone application Telephone |

– | Yes | – | – | – | – | Yes |

| Tildesley,140 2011 | Physician | Web portal | Web portal Telephone |

– | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | – |

| Lorig,103 2010 (Web program) | Trained peer Moderator/Program administrator | Web portal | Web portal | Weekly | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Lorig,103 2010 (Web program plus email reinforcement) | Trained peer Moderator/Program administrator | Web portal Listserv |

Web portal Listserv |

Weekly | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| McCarrier,108 2009 | CDSS Care manager |

Web portal |

Web portal |

Weekly | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Ralston,126 2009 | CDSS Care manager |

Web portal | Web portal | Weekly | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Shea,133 2009 | Care manager | Web portal Videoconference |

Web portal Smart device |

– | Yes | Yes | – | – | Yes | Yes |

| Yoo,153 2009 | CDSS Physician |

Web portal | SMS Smart device |

Twice daily | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Kim,98 2008 | Nurse | Web portal SMS |

Web portal | Weekly | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Yoon,154 2008 | Nurse Physician |

Web portal SMS |

Web portal | Weekly | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Bond,57 2007 | Nurse Research team |

Web portal | Web portal | – | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Kim,96 2007 | Nurse Diabetes educator |

Web portal SMS |

Web portal | Weekly | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | – |

| Cho,61 2006 | Nurse Physician Dietitian |

Web portal | Web portal | Every 2 wk | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| McMahon,109 2005 | Nurse | Web portal Telephone |

Web portal Smart devices |

– | Yes | Yes | – | – | Yes | Yes |

| Kwon,100 2004 | Nurse Physician Dietitian |

Web portal |

Web portal | – | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | – |

| Gomez,78 2002 | CDSS Physician |

Web portal | Web portal (PDA) Telephone |

Every 2 wk | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | – | – |

| Arora,50 2014 | CDSS | SMS | – | Twice daily | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Nagrebetsky,113 2013 | Nurse | SMS Telephone |

Smart device | Monthly | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | – |

| Rossi,130 2013 | Physician | SMS | SMS | – | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | Yes |

| Tang,138 2013 | CDSS Care manager Dietitian |

SMS | Web portal Smart device |

– | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Goodarzi,79 2012 | Research team | SMS | – | NA | Yes | – | – | – | – | Yes |

| Lim,102 2011 | CDSS Nurse Physician Dietitian Exercise trainer |

SMS | Smart device | ~ daily† | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | Yes |

| Shetty,134 2011 | Health care provider | SMS | – | NA | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Kim,95 2010 | CDSS | SMS | Smart device | Daily | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | Yes |

| Rossi,129 2010 | Physician Dietitian |

SMS | SMS | – | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | – | Yes |

| Tildesley,141 2010 | Physician | SMS | SMS Smart device | – | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | – |

| Benhamou,53 2007 | Physician | SMS | PDA | Weekly | Yes | – | – | – | – | – |

| Kim,92 2007 | CDSS | SMS | Web portal Smart device |

– | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Harno,81 2006 | Diabetes team | SMS | Smart device | – | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | – | – |

| Katalenich,88 2015 | CDSS | Automated text and voice reminder (CDSS) | – | Daily | – | Yes | – | – | – | – |

| Nicolucci,115 2015 | CDSS Nurse | Automated text, email and voice reminder (CDSS) Telephone |

Smart devices Call-me button |

Monthly | Yes | – | – | – | – | Yes |

| Khanna,91 2014 | CDSS | Automated interactive voice (CDSS to telephone) | – | – | Yes | – | Yes | – | – | – |

| Glasgow,75 2012 (CASM) | CDSS Research team |

Automated interactive voice (CDSS to telephone) |

Web portal | – | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Glasgow,75 2012 (CASM plus) | CDSS Physician Nutritionist Research team |

Automated interactive voice (CDSS to telephone) Telephone |

Web portal Telephone |

Twice | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Graziano,80 2009 | CDSS Research team | Automated interactive voice (CDSS to telephone) Telephone |

– | – | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Holbrook,84 2009 | CDSS Research team |

Automated voice reminder (Telephone) Letter |

– | – | – | – | – | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Schillinger,131 2009 | CDSS Care manager |

Automated interactive voice (CDSS to telephone) Telephone |

– | Weekly | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Piette,120 2001 | CDSS Nurse |

Automated interactive voice (CDSS to telephone) Telephone |

– | Weekly | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | Yes |

| Piette,121 2000 | CDSS Nurse |

Automated interactive voice (CDSS to telephone) Telephone |

Telephone | Weekly | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | Yes |

| Pressman,123 2014 | Care manager | Smart device Telephone |

Smart device | Weekly | Yes | – | – | – | – | Yes |

| Wakefield,145 2011 | CDSS Nurse Diabetes educator Physician |

Smart device Telephone |

Smart device | – | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Stone,136 2010 | Nurse | Smart device Telephone |

Smart device | Monthly | Yes | Yes | – | – | Yes | Yes |

| Jansa,86 2006 | Diabetes team | Smart device | Smart device Telephone Fax |

1.5 times per mo | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Steventon,135 2014 | CDSS Nurse Support worker |

Computer software | Smart device Telephone |

~ daily† | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | Yes |

| Charpentier,60 2011 | Physician | Computer software Telephone |

Smartphone application | Every 2 wk | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | – |

| Tsang,142 2001 | CDSS | Computer software | PDA | Every 2 d | – | – | Yes | – | – | Yes |

| Rasmussen,127 2015 | Nurse Physician |

Videoconference | – | – | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | – |

| Davis,65 2010 | Nurse Dietitian |

Videoconference Telephone |

– | Monthly | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Whitlock,149 2000 | Care manager Physician |

Videoconference | – | Weekly | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | – | – |

| Waki,146 2014 | CDSS Physician Dietitian |

Email Telephone |

Smart devices Smartphone |

Daily | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Leichter,101 2013 | Physician | Email Telephone |

Computer software | Twice | Yes | – | – | – | Yes | – |

| Quinn,124 2008 | CDSS Diabetes educator Physician Nutritionist Research team |

Smartphone application | – | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | – | Yes | |

| Kim,93 2006 | Nurse | Patient Web page Telephone |

Patient Web page | Weekly | Yes | – | – | Yes | – | Yes |

| Farmer,69 2005 | CDSS Nurse |

Patient Web page Telephone |

Smartphone application | Every 2 wk | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | – |

| Bell,52 2012 | Nurse | Smartphone video message |

– | NA | – | – | – | – | – | Yes |

| Glasgow,76 1997 | CDSS Research team |

Video message Telephone |

– | 5 times | Yes | – | Yes | – | – | Yes |

| Heisler,82 2014 | CDSS Community health care worker |

Smartphone application Telephone |

– | Every 3 wk | Yes | – | – | – | – | Yes |

| Kaur,89 2015 | Physician | Telephone | Telephone | Weekly | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | – | – |

| Shahid,132 2015 | Research team | Telephone | – | ~ every 2 wk† | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Chan,59 2014 | Trained peer | Telephone | Telephone | Every 2 wk then monthly then every 2 mo | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Esmatjes,68 2014 | Diabetes team | Telephone | Smart device | Monthly | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | – |

| Lynch,105 2014 | Trained peer | Telephone | – | Weekly | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| O’Conner,116 2014 | Care manager Diabetes educator Pharmacist |

Telephone | – | Once | Yes | – | – | – | – | – |

| Suh,137 2014 | CDSS Trained peer |

Telephone | Smart device | Twice monthly | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Varney,144 2014 | Dietitian | Telephone | – | Monthly | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Aliha,48 2013 | Nurse | Telephone | – | Twice weekly then weekly | Yes | – | – | – | – | Yes |

| Blackberry,55 2013 | Nurse | Telephone | – | ~ monthly† | Yes | Yes | – | – | Yes | Yes |

| then 3 sessions | ||||||||||

| Crowley,63 2013 | Nurse | Telephone | – | Monthly | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Eakin,67 2013 | Counsellor | Telephone | – | ~ every 2 wk† | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Gagliardino,74 2013 | Trained peer | Telephone | – | Weekly then every 2 wk then monthly | Yes | – | – | – | – | Yes |

| Mons,111 2013 | Nurse | Telephone | – | Monthly | Yes | – | – | – | – | – |

| Munshi,112 2013 | Care manager Diabetes educator |

Telephone | – | ~ every 2 wk† | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Plotnikoff,122 2013 | Telephone counsellor | Telephone | – | – | Yes | – | – | Yes | – | Yes |

| Van Dyck,143 2013 | Psychologist | Telephone | – | Every 2 wk then monthly | Yes | – | – | Yes | – | Yes |

| Bogner,56 2012 | Research team | Telephone | – | Twice | Yes | – | – | – | – | Yes |

| Del Prato,66 2012 | Physician | Telephone | Smart device | – | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | – |

| Jarab,87 2012 | Pharmacist | Telephone | – | Weekly | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Marois,107 2012 | Exercise physiologist | Telephone | – | Weekly | Yes | – | – | Yes | – | – |

| Patja,119 2012 | Nurse | Telephone | – | Monthly | Yes | – | – | – | – | Yes |

| Williams,150 2012 | Nurse | Telephone | – | Every 2 wk | Yes | – | – | – | – | Yes |

| Williams,151 2012 | CDSS Research team |

Telephone | Automated interactive voice (Telephone to CDSS) | Weekly | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Farsaei,71 2011 | Pharmacist | Telephone | – | – | Yes | – | – | – | – | Yes |

| Franciosi,72 2011 | Nurse Physician |

Telephone | – | Monthly | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Frosch,73 2011 | Nurse | Telephone | – | ~ monthly† | Yes | – | – | – | – | Yes |

| Keogh,90 2011 | Psychologist | Telephone | – | Once | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Kim,94 2011 | Research team | Telephone | Telephone | Weekly | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Walker,147 2011 | Diabetes educator | Telephone | – | ~ monthly† | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Anderson,49 2010 | Nurse | Telephone | – | Weekly | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Farsaei,70 2010 | Pharmacist | Telephone | – | Weekly | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Heisler,83 2010 | Care manager Trained peer Research team |

Telephone | – | – | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | Yes |

| Nesari,114 2010 | Nurse | Telephone | – | Twice weekly then weekly | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Dale,64 2009 | Trained peer | Telephone | – | 6 times (frequency decreased over follow-up) | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | – |

| Istepanian,85 2009 | Physician | Telephone | Smart device | – | Yes | – | – | – | – | Yes |

| Rodriguez-Idigoras,128 2009 | CDSS Nurse Physician |

Telephone | Smart device Telephone |

– | Yes | – | – | – | – | – |

| Glasgow,77 2005 | Care manager | Telephone | Telephone | Twice yearly | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Maljanian,106 2005 | Nurse Nutritionist |

Telephone | – | Weekly | Yes | – | Yes | – | – | Yes |

| Young,155 2005 | Nurse Telecarer |

Telephone | – | 3 groups: Every 3 mo Every 2 mo Monthly |

Yes | Yes | – | – | – | Yes |

| Montori,21 2004 | Nurse | Telephone | Smart device | Every 2 wk | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | – |

| Wolf,152 2004 | Care manager | Telephone | – | Monthly | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Kim,97 2003 | Nurse Dietitian |

Telephone | – | Twice weekly then weekly | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Biermann,54 2002 | Physician | Telephone | Smart device | – | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | – |

| Thompson,139 1999 | Nurse | Telephone | Telephone | 3 times weekly | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | – |

| Weinberger,148 1995 | Nurse | Telephone | – | Monthly | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Ahring,47 1992 | Research team | Telephone | Smart device | Weekly | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | – | Yes |

| Luley,104 2014 | CDSS Research team |

Letter | Smart device | Weekly | – | – | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

Note: CDSS = clinical decision support system, NA = not applicable, PCP = primary care provider, PDA = personal digital assistant, SMS = short message service (text messaging), “–” = not reported.

Studies are ordered by provider-to-patient communication; they are ordered by any use of Web portals, SMS text messaging, automated communication, smart device, computer software, videoconference, email, customized patient Web pages, video messaging, smartphone application, telephone and letter. A smart device is any computerized device specifically developed to collect and transmit patient data to health care providers. Web portals are websites where patients upload blood glucose or other clinical data and share these with their health care providers; many times providers also use Web portals to provide feedback to patients. CDSS systems receive data from patients and automatically respond using computer algorithms in a variety of ways, such as precomposed messages sent as SMS text messages to patients (Kim 201095), alarms sent to the providers when abnormal data are received (Gomez78), analyzed data reports sent to providers (Quinn125) and voice feedback over the telephone to patients (Schillinger131). Other components not mentioned in this table include psychological support, such as support for depression, smoking cessation and behavioural therapy.

Indicates an approximate frequency of feedback. For example, we used “~ daily” rather than 3 times per week for Lim102; “~ every 2 wk” replaced 14 times per 6 months for Eakin,67 and 11 times per 6 months for Munshi;112 “~ monthly” replaced 5 times per 6 months for Blackberry55 and Frosch,73 and 10 times per year for Walker;147 and “~ every 2 mo” replaced every 7 weeks for Young.155

Health care providers initiated communication with patients in at least 4 ways: voice, text messaging, images and through clinical decision support systems. The platforms used were telephone (59%), clinical decision support system (32%; e.g., automated interactive voice [9%]), Web portal (22%), SMS (16%), email (7%), videoconference (4%), computer software (3%), customized “smart” device (3%), customized patient-specific Web page (2%), video message (2%), letter (2%), smartphone application (1%) or listserv (1%). Providers were nurses (37%), care managers (10%), diabetes educators (11%), physicians (29%), allied health professionals (17%; including dietitians, nutritionists, physiologists, exercise trainers, psychologists and pharmacists), clinical decision support systems (32%) and nonspecialized support (23%; including trained peers, members of research teams, counsellors and community health care workers).

Most (94%) of the interventions were interactive, whereby the patient could communicate with the provider, and the provider could communicate with the patient. Interactive telecommunication initiated by providers occurred in the following frequencies: at least daily (8%), weekly (26%), every 2 weeks (10%), monthly (16%) or less often (7%). Frequency of interaction was not reported in 33% of trials. Many of the interventions (45%) adjusted medication based on the data received. Other frequent components of the interventions included general diabetes education (76%), nutritional interventions (53%), exercise (49%) and blood pressure management (9%).

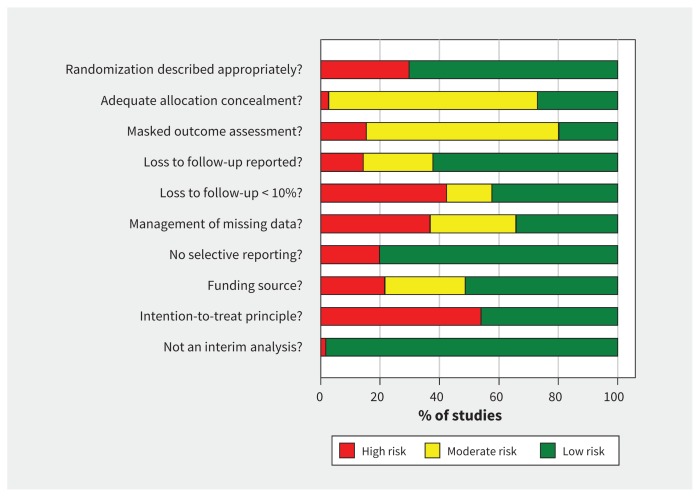

The risk-of-bias assessment of the trials is shown in Figure 2 and Table A2 in Appendix 1. Because blinding of participants is not feasible for telemedicine interventions, all trials were open label to the participants; thus, every trial included at least 1 element of risk of bias. However, we assessed for blinding of outcome assessors (present in 20% of trials). Seventy-eight trials (70%) reported and described an appropriate method of randomization, but only 30 (27%) reported an adequate allocation concealment process. The intention-to-treat principle was applied in 51 (46%) of the trials. Public funding was exclusively used in 57 trials (51%).

Figure 2:

Summary of risk-of-bias assessment. See Table A2 in Appendix 1 for a detailed account of risk for each trial (available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.150885/-/DC1).

Effect on HbA1C

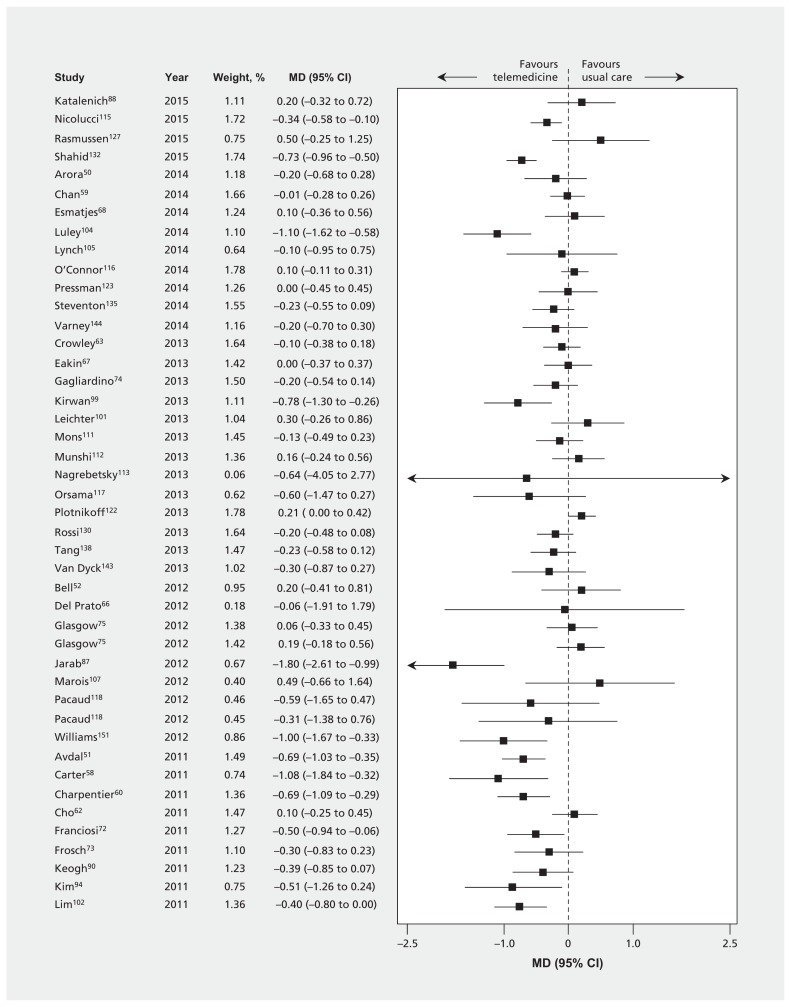

Thirty-nine trials (n = 3165) reported the effect of telemedicine on HbA1C at 3 months or less (Table 3 and Table A3 in Appendix 1). Eighty-seven trials (n = 15 524) reported HbA1C at 4–12 months, and 5 trials (n = 1896) reported HbA1C beyond 12 months. The MDs were all significant and favoured telemedicine, although there was large heterogeneity (≤ 3 mo: −0.57%, 95% confidence interval [CI] −0.74% to −0.40%, I2 = 75%; 4–12 mo: −0.28%, 95% CI −0.37% to −0.20%, I2 = 69% [Figure 3]; and > 12 mo: −0.26%, 95% CI −0.46% to −0.06%, I2 = 58%). Inspection of the effect sizes identified 3 outlier trials87,98,154 for which effects were larger than in the other trials. Exclusion of these 3 trials did not materially affect our results for the primary outcome (HbA1C at 4–12 mo), but it did reduce heterogeneity (−0.24%, 95% CI −0.31% to −0.16%, I2 = 58%). Findings were similar when control of HbA1C was dichotomized at various thresholds (6.4%–6.5%, 7%–7.5%, 8% or 9%) and when we pooled results from the last time points from every available trial (Table A3 in Appendix 1, and Appendix 2 [available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.150885/-/DC1]).

Table 3:

Pooled estimates of the effect of telemedicine on outcomes

| Outcome | Time point, mo | No. of trials and within-trial subgroups (no. of participants*) | I2 statistic, % | Pooled estimate (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality | ≤ 3 | 11 (1361) | 0 | RD,%: 0.2 (−0.6 to 0.9) |

| 4–12 | 42 (7197) | 0 | RD,%: −0.2 (−0.6 to 0.2) | |

| > 12 | 4 (2376) | 0 | RD,%: −0.3 (−1.6 to 1.0) | |

| HbA1C | ||||

| HbA1C level, % | ≤ 3 | 39 (3165) | 75 | MD, %: −0.57 (−0.74 to −0.40) |

| 4–12 | 87 (15 524) | 69 | MD, %: −0.28 (−0.37 to −0.20) | |

| > 12 | 5 (1896) | 58 | MD, %: −0.26 (−0.46 to −0.06) | |

| HbA1C < 6.4% or < 6.5% | 4–12 | 1 (248) | – | RR: 1.79 (0.98 to 3.27) |

| > 12 | 1 (80) | – | RR: 2.33 (0.997 to 5.46) | |

| HbA1C < 7%, ≤ 7% or ≤ 7.5% | ≤ 3 | 7 (1016) | 91 | RR: 2.30 (1.21 to 4.38) |

| 4–12 | 11 (1615) | 73 | RR: 1.46 (1.03 to 2.08) | |

| HbA1C < 8% or ≤ 8% | ≤ 3 | 1 (137) | – | RR: 2.28 (1.42 to 3.67) |

| 4–12 | 3 (602) | 72 | RR: 1.20 (0.90 to 1.61) | |

| HbA1C < 9% | ≤ 3 | 1 (137) | – | RR: 1.31 (1.07 to 1.60) |

| 4–12 | 1 (137) | – | RR: 1.26 (1.04 to 1.52) | |

| SF-36 (0–100)† | ||||

| Mental component summary | ≤ 3 | 2 (295) | 0 | MD: −1.06 (−3.19 to 1.07) |

| 4–12 | 4 (784) | 63 | MD: 0.47 (−1.89 to 2.84) | |

| Physical component summary | ≤ 3 | 2 (295) | 42 | MD: 0.92 (−1.97 to 3.81) |

| 4–12 | 4 (784) | 0 | MD: 0.08 (−1.16 to 1.32) | |

| Bodily pain | ≤ 3 | 2 (309) | 86 | MD: 5.46 (−8.64 to 19.56) |

| 4–12 | 6 (1166) | 19 | MD: 0.44 (−2.19 to 3.07) | |

| General health | ≤ 3 | 2 (306) | 0 | MD: 0.97 (−1.42 to 3.37) |

| 4–12 | 6 (1163) | 58 | MD: 1.12 (−2.07 to 4.32) | |

| Health transition | 4–12 | 1 (117) | – | MD: 3.00 (−6.00 to 12.00) |

| Mental health | ≤ 3 | 2 (308) | 0 | MD: −1.09 (−3.19 to 1.01) |

| 4–12 | 7 (1285) | 62 | MD: 2.31 (−0.24 to 4.86) | |

| Physical functioning | ≤ 3 | 2 (311) | 30 | MD: −3.98 (−7.34 to −0.62) |

| 4–12 | 7 (1288) | 58 | MD: 1.06 (−1.52 to 3.64) | |

| Role emotional | ≤ 3 | 2 (304) | 0 | MD: −1.00 (−3.50 to 1.51) |

| 4–12 | 6 (1161) | 80 | MD: 2.89 (−4.96 to 10.74) | |

| Role physical | ≤ 3 | 2 (307) | 0 | MD: 0.30 (−2.38 to 2.97) |

| 4–12 | 6 (1164) | 62 | MD: 2.20 (−3.62 to 8.02) | |

| Social functioning | ≤ 3 | 2 (311) | 0 | MD: −2.22 (−4.34 to −0.10) |

| 4–12 | 6 (1168) | 59 | MD: −0.27 (−3.78 to 3.24) | |

| Vitality | ≤ 3 | 2 (310) | 0 | MD: 0.50 (−1.98 to 2.98) |

| 4–12 | 6 (1167) | 69 | MD: 1.57 (−2.26 to 5.40) | |

| SF-12 (0–100)† | 4–12 | 1 (35) | – | MD: −1.00 (−2.33 to 0.33) |

| Mental component summary | 4–12 | 3 (549) | 0 | MD: 0.51 (−1.26 to 2.29) |

| > 12 | 1 (204) | – | MD: 2.37 (−2.15 to 6.89) | |

| Physical component summary | 4–12 | 3 (549) | 7 | MD: −0.05 (−2.46 to 2.35) |

| > 12 | 1 (204) | – | MD: 0.35 (−5.66 to 6.36) | |

| Diabetes Quality of Life (1–5)† | ≤ 3 | 1 (98) | – | MD: −0.19 (−0.52 to 0.14) |

| 4–12 | 6 (184) | 0 | MD: −0.003 (−0.10 to 0.09) | |

| Diabetes-related worry | ≤ 3 | 2 (166) | 36 | MD: 0.03 (−0.25 to 0.32) |

| 4–12 | 4 (302) | 67 | MD: 0.08 (−0.17 to 0.34) | |

| Impact of diabetes | ≤ 3 | 2 (166) | 59 | MD: −0.01 (−0.31 to 0.28) |

| 4–12 | 4 (302) | 60 | MD: 0.02 (−0.17 to 0.21) | |

| Satisfaction with life | ≤ 3 | 1 (68) | – | MD: 0.24 (−0.05 to 0.53) |

| 4–12 | 4 (222) | 47 | MD: 0.16 (−0.02 to 0.33) | |

| Social/vocational worry | ≤ 3 | 1 (98) | – | MD: −0.12 (−0.33 to 0.09) |

| 4–12 | 3 (249) | 54 | MD: −0.05 (−0.29 to 0.20) | |

| Diabetes Distress Scale (1–6)‡ | 4–12 | 6 (777) | 0 | MD: −0.01 (−0.17 to 0.15) |

| EQ-5D (0–1)† | 4–12 | 2 (743) | 0 | MD: −0.01 (−0.01 to −0.01) |

| PAID (0–100)† | 4–12 | 2 (363) | 0 | MD: 2.86 (1.74 to 3.97) |

| Hypoglycemia (patient-years) | ≤ 3 | 3 (46) | 0 | RR: 0.94 (0.80 to 1.12) |

| 4–12 | 5 (848) | 93 | RR: 0.86 (0.66 to 1.12) | |

| Severe hypoglycemia (patient-years) | 4–12§ | 4 (427) | 92 | RR: 0.59 (0.17 to 2.05) |

| Hypoglycemia (% of patients affected) | ≤ 3 | 5 (462) | 63 | RD, %: 0.0 (−5.5 to 5.5) |

| 4–12 | 4 (282) | 47 | RD, %: 3.1 (−7.9 to 14.2) | |

| Severe hypoglycemia | ≤ 3 | 1 (92) | – | RD, %: 0.0 (−4.2 to 4.2) |

| 4–12 | 10 (1259) | 0 | RD, %: −0.1 (−1.0 to 0.8) | |

Note: CI = confidence interval, EQ-5D = European Quality of Life survey with 5 dimensions, HbA1C = glycated hemoglobin, MD = difference in means, PAID = Problem Areas in Diabetes, RD = difference in risk, RR = risk ratio or rate ratio, SF-12 = 12-item Short Form Health Survey, SF-36 = 36-item Short Form Health Survey, – = not applicable.

We used effective sample sizes in cluster trials and patient-years for rate ratios.

Large values indicate a better quality of life.

Small values indicate a better quality of life.

No data available for time point ≤ 3 mo.

Figure 3:

Differences in mean glycated hemoglobin levels at 4–12 months between telemedicine intervention groups and usual care groups. Values less than zero favour telemedicine. CI = confidence interval, MD = difference in means.

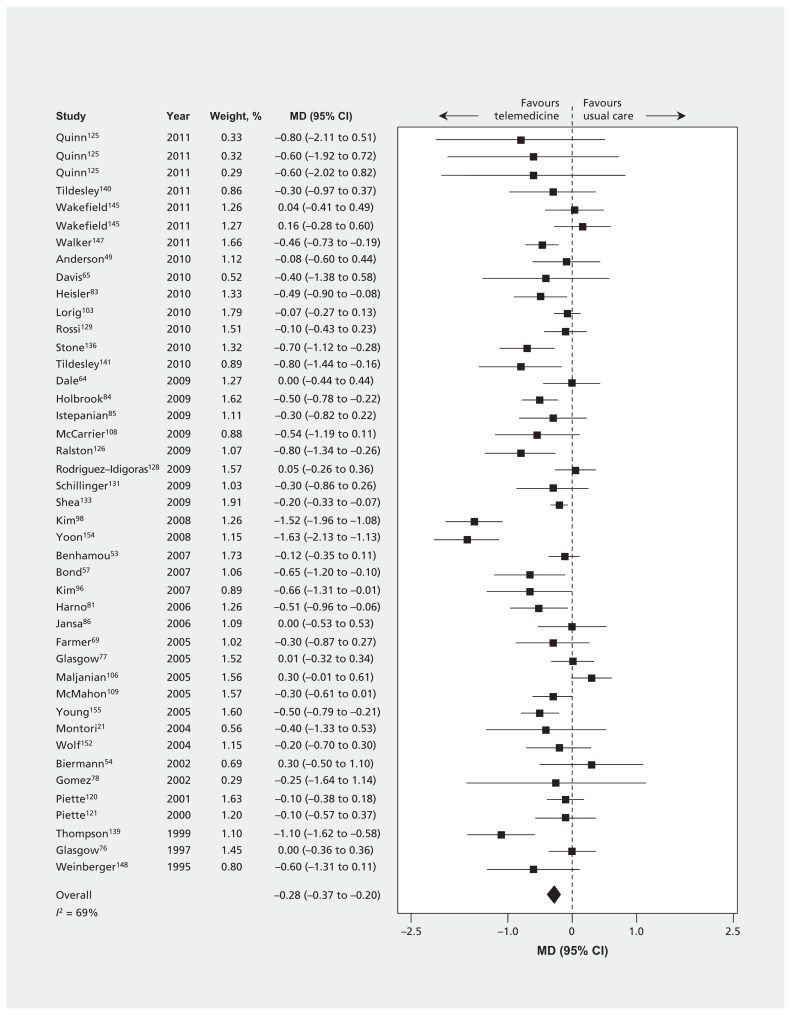

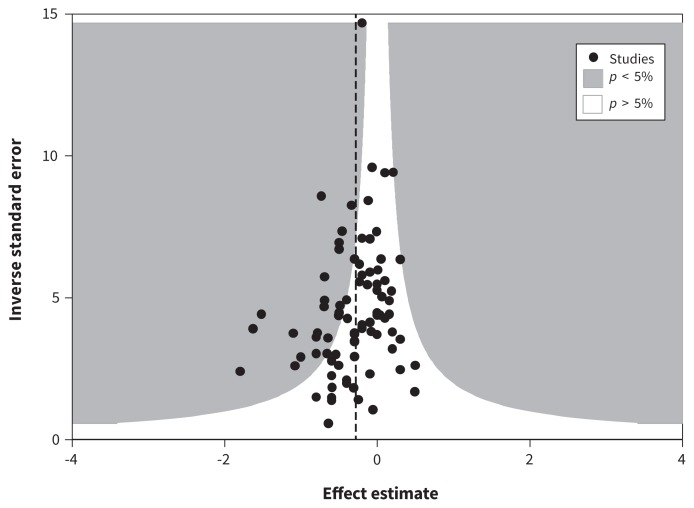

The contour funnel plot of HbA1C was asymmetrical, consistent with publication bias (more small studies favouring telemedicine) (Figure 4). The bias estimate from the regression analysis was significant (Egger test: bias −0.95, p = 0.02). When the 3 outlier trials were removed, the bias estimate was not significant (bias −0.68, p = 0.07).

Figure 4:

Contour funnel plot using glycated hemoglobin levels at 4–12 months. Each trial’s precision (the inverse of the standard error of each study’s effect estimate) is plotted against each trials’s effect estimate. This funnel plot appears mildly asymmetric about the vertical dashed line (the fixed-effects pooled estimate). There are 3 statistical outliers that appear in the far right of the plot. The emptier left side of the inverted funnel may indicate small missing studies. Because most of these missing studies would be within the white region, they would be nonsignificant, which would indicate publication bias rather than some form of heterogeneity.

Meta-regression analysis

We explored a number of population and intervention characteristics using univariable meta-regression (Table 4). Both trial region and baseline HbA1C modified the effect of telemedicine on final HbA1C, but mean age, percent male, diabetes duration, BMI, insulin use, use of oral hypoglycemic therapy and diabetes type did not. European (n = 26) and North American trials (reference group, n = 47) reported similar MDs (difference in MD −0.08%, 95% CI −0.27% to 0.11%); however, trials from Asia (n = 9) reported significantly larger differences favouring telemedicine relative to North American trials (difference in MD −0.49%, 95% CI −0.77% to −0.22%).

Table 4:

Association between population characteristics, intervention characteristics, risk-of-bias items and the effect of telemedicine on HbA1C at 4–12 mo

| Variable | No. of trials and within-trial subgroups | Difference in MD (95% CI) | p value | I2 statistic, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population characteristics | ||||

| Continent | ||||

| North or South America | 47 | 0 (ref) | 65 | |

| Europe | 26 | −0.08 (−0.27 to 0.11) | 0.4 | |

| Asia | 9 | −0.49 (−0.77 to −0.22) | 0.001 | |

| Oceania | 5 | −0.16 (−0.55 to 0.23) | 0.4 | |

| Age (range 24–75 yr) | 83 | 0.003 per 1 yr (−0.005 to 0.01) | 0.4 | 68 |

| Sex, male (range 20%–100%) | 84 | 0.0002 per 1% (−0.005 to 0.005) | 0.9 | 70 |

| Duration of follow-up (range 2.6–24 yr) | 52 | 0.008 per 1 yr (−0.02 to 0.03) | 0.5 | 69 |

| Baseline HbA1C (range 6.4%–10.7%) | 87 | −0.06 per 1% (−0.16 to 0.04) | 0.3 | 68 |

| BMI score (range 23–38) | 62 | 0.02 per 1 score (−0.01 to 0.05) | 0.2 | 71 |

| % using insulin (0%–100%) | 59 | −0.00008 per 1% (−0.004 to 0.003) | 1.0 | 71 |

| % using OHA (range 44%–100%) | 31 | 0.003 per 1% (−0.006 to 0.01) | 0.5 | 72 |

| Type of diabetes mellitus | ||||

| Type 2 | 58 | 0 (ref) | 69 | |

| Type 1 | 11 | 0.05 (−0.22 to 0.33) | 0.7 | |

| Mixed | 9 | 0.20 (−0.09 to 0.50) | 0.2 | |

| Unknown | 9 | 0.13 (−0.14 to 0.41) | 0.3 | |

| Intervention characteristics | ||||

| Patient-to-provider communication | ||||

| Telephone | 14 | 0 (ref) | 69 | |

| Smartphone application | 7 | −0.25 (−0.71 to 0.21) | 0.3 | |

| Web portal | 23 | −0.16 (−0.44 to 0.12) | 0.3 | |

| Smart device | 23 | 0.06 (−0.23 to 0.36) | 0.7 | |

| Provider-to-patient communication | ||||

| Telephone | 51 | 0 (ref) | 67 | |

| SMS text messaging | 12 | −0.28 (−0.52 to −0.05) | 0.02 | |

| Web portal | 20 | −0.35 (−0.56 to −0.14) | 0.001 | |

| CDSS | 27 | 0.10 (−0.08 to 0.28) | 0.3 | |

| Type of provider | ||||

| Nurse | 33 | 0 (ref) | 69 | |

| CDSS | 27 | 0.07 (−0.12 to 0.27) | 0.5 | |

| Diabetes educator | 11 | 0.10 (−0.21 to 0.40) | 0.5 | |

| Physician | 25 | 0.13 (−0.10 to 0.35) | 0.3 | |

| Allied health | 12 | 0.15 (−0.11 to 0.41) | 0.3 | |

| Care manager | 11 | 0.16 (−0.11 to 0.43) | 0.2 | |

| Nonspecialized support | 19 | 0.17 (−0.05 to 0.40) | 0.1 | |

| Frequency of contact | ||||

| Daily | 5 | 0 (ref) | 68 | |

| Weekly | 19 | −0.09 (−0.49 to 0.30) | 0.6 | |

| Every 2 wk | 11 | −0.05 (−0.48 to 0.38) | 0.8 | |

| Monthly | 15 | 0.05 (−0.36 to 0.45) | 0.8 | |

| Less frequently than monthly | 6 | 0.37 (−0.09 to 0.83) | 0.1 | |

| Not reported | 29 | 0.11 (−0.27 to 0.49) | 0.6 | |

| Additional components | ||||

| Interactive | 82 | 0.03 (−0.34 to 0.40) | 0.9 | 68 |

| Medication adjustment | 40 | −0.23 (−0.42 to −0.05) | 0.01 | |

| Exercise | 41 | −0.11 (−0.39 to 0.18) | 0.5 | |

| General education | 65 | −0.21 (−0.44 to 0.02) | 0.1 | |

| Blood pressure management | 8 | −0.002 (−0.31 to 0.30) | 1.0 | |

| Nutrition | 41 | 0.08 (−0.21 to 0.37) | 0.6 | |

| Risk of bias | ||||

| Randomization not described appropriately | 24 | −0.03 (−0.23 to 0.17) | 0.8 | 69 |

| Inadequate or unclear allocation concealment | 60 | −0.07 (−0.25 to 0.11) | 0.5 | 69 |

| Blinding | ||||

| Yes | 18 | 0 (ref) | 69 | |

| No | 12 | 0.12 (−0.19 to 0.43) | 0.4 | |

| Unclear | 57 | 0.15 (−0.08 to 0.38) | 0.2 | |

| Loss to follow-up | ||||

| Reported | 55 | 0 (ref) | 65 | |

| Not reported | 10 | −0.11 (−0.37 to 0.16) | 0.4 | |

| Partially reported | 22 | 0.30 (0.11 to 0.48) | 0.003 | |

| % loss to follow-up (range 0%–39%) | 76 | 0.005 per 1% (−0.006 to 0.02) | 0.4 | 67 |

| No selective reporting | 71 | −0.06 (−0.30 to 0.17) | 0.6 | 69 |

| Funding | ||||

| Public | 45 | 0 (ref) | 69 | |

| Private | 17 | −0.004 (−0.24 to 0.23) | 1.0 | |

| Neither | 13 | 0.01 (−0.24 to 0.26) | 0.9 | |

| Both | 12 | 0.14 (−0.17 to 0.45) | 0.4 | |

| Not intention-to-treat analysis | 40 | −0.14 (−0.31 to 0.04) | 0.1 | 68 |

| Adjustment for potential confounders | 17 | 0.08 (−0.14 to 0.29) | 0.5 | 69 |

Note: BMI = body mass index, CDSS = computer decision support system, CI = confidence interval, HbA1C = glycated hemoglobin, MD = difference in means, OHA = oral hypoglycemic agents, ref = reference category, SMS = short message service.

Categories with < 5 studies were not included in the meta-regression analyses; heterogeneity in the primary analysis was 69%.

Because most telemedicine platforms were used in fewer than 5 trials, it was not possible to use meta-regression to evaluate the relative merits of all platforms. Choice of patient-to-provider platform (smartphone application, Web portal, smart device, telephone) did not significantly modify the effect of telemedicine on HbA1C. However, choice of provider-to-patient platform (SMS text messaging, Web portal, clinical decision support system, telephone) significantly influenced the association between telemedicine and HbA1C, with both SMS text messaging and Web portal associated with greater benefit than telephone-based systems (difference in MD: SMS v. telephone −0.28%, 95% CI −0.52% to −0.05%; Web portal v. telephone −0.35%, 95% CI −0.56% to −0.14%). Interventions in which providers adjusted medication in response to data from patients were also associated with larger improvements in HbA1C (−0.23%, 95% CI −0.42% to −0.05%). Inclusion of interactive communication, exercise, general diabetes education, blood pressure management or nutritional interventions did not modify the benefit of telemedicine on HbA1C. Frequency of contact and type of provider did not significantly modify the association.

None of the items from the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool were significant effect modifiers, except for reporting loss to follow-up. Trials that partially reported loss to follow-up (i.e., no stated reasons for loss to follow-up, or loss was reported for the whole trial and not by group) showed a smaller difference in HbA1C than trials with fully reported loss to follow-up or trials that did not report loss to follow-up (difference in MD 0.30%, 95% CI 0.11% to 0.48%). Because there was no gradient of effect, there was no evidence that reporting versus not reporting loss to follow-up was a significant effect modifier.

Effect on quality of life and mortality

Few trials (27 trials) reported on quality of life. Among the 23 trials that reported an instrument used by at least one other trial, a total of 6 instruments were validated (Table 3). Telemedicine led to significant improvement in the Problem Areas in Diabetes score (MD at 4–12 mo: 2.86, 95% CI 1.74 to 3.97, I2 = 0%, 2 trials, n = 363). Three scores or subscores showed significant worsening (SF-36 physical functioning ≤ 3 mo: MD −3.98, 95% CI −0.62 to −7.34, I2 = 30%, 2 trials, n = 311; SF-36 social functioning ≤ 3 mo: MD −2.22, 95% CI −0.10 to −4.34, I2 = 0%, 2 trials, n = 311; and EQ-5D at 4–12 mo: MD −0.01, 95% CI −0.01 to −0.01, 2 trials, n = 743). There was no evidence of selective reporting of subscores for quality of life. However, the effect of telemedicine was not significant for most subscores, and the few statistically significant differences were likely not clinically relevant.157

We pooled the mental health and physical health component summaries of the SF-36 and SF-12 instruments from 7 trials (n = 1333): MD 0.55 (95% CI −0.83 to 1.92; I2 = 29%) and 0.06 (95% CI −1.01 to 1.13; I2 = 0%), respectively. We also pooled the global scores (after transformation to a 1–100 range, where 100 was optimal) from all 3 diabetes-specific instruments from 8 trials (14 within-trial subgroups, n = 1324): MD 0.86 (95% CI −0.73 to 2.45; I2 = 23%). Because all of these findings were nonsignificant,157 there was no evidence to suggest that telemedicine enhanced quality of life.

Eleven trials (n = 1361) reported all-cause mortality within 3 months, 42 trials (n = 7197) reported mortality at 4–12 months, and 4 trials (n = 2376) reported mortality beyond 12 months. The risk differences were all nonsignificant, without evidence of heterogeneity (≤ 3 mo: 0.2%, 95% CI −0.6% to 0.9%, I2 = 0%, 6 deaths; 4–12 mo: −0.2%, 95% CI −0.6% to 0.2%, I2 = 0%, 68 deaths; and > 12 mo: −0.3%, 95% CI −1.6% to 1.0%, I2 = 0%, 351 deaths).

Effect on hypoglycemia

Five trials (n = 462) reported participants with hypoglycemic episodes within 3 months, and 4 trials (n = 282) reported participants with hypoglycemia at 4–12 months (Table 3). One trial (n = 92) reported participants with severe hypoglycemia within 3 months, and 10 trials (n = 1259) reported participants with severe hypoglycemia at 4–12 months. There was no evidence that telemedicine reduced the risk of hypoglycemic episodes (risk difference for hypoglycemic episodes ≤ 3 mo: 0.0%, 95% CI −5.5% to 5.5%, I2 = 63%; and at 4–12 mo: 3.1%, 95% CI −7.9% to 14.2%, I2 = 47%). Risk differences for severe hypoglycemia were also not significant (≤ 3 mo: 0.0%, 95% CI −4.2% to 4.2%; and at 4–12 mo: −0.1%, 95% CI −1.0% to 0.8%, I2 = 0%).

Interpretation

Compared with usual care, the addition of telemedicine appeared to improve HbA1C significantly in people with either type 1 or 2 diabetes. Although there was substantial heterogeneity, the pooled analyses showed that telemedicine lowered HbA1C by 0.57% within 3 months and by 0.28% beyond 4 months. The lower apparent magnitude of benefit with longer follow-up may reflect reduced adherence to the intervention. Nonetheless, the effect on HbA1C appears clinically relevant and is comparable to improvements associated with some oral antidiabetic agents (0.5%–1.25%),158 psychosocial interventions (0.6%, 95% CI −1.2% to −0.1%)159 or quality improvement strategies (0.42%, 95% CI 0.29% to 0.54%)160 among patients with diabetes. However, we did not find good evidence that telemedicine reduced the risk of hypoglycemia, quality of life or mortality, although it is unlikely that benefits for the latter would have been observed given the short duration of the included trials. Although telemedicine may also improve patient satisfaction with care, we did not collect data to test this hypothesis, and thus this suggested benefit is speculative.

The meta-regression analyses suggested that telemedicine interventions that facilitated medication adjustments were more effective in improving glycemic control than interventions that did not allow such adjustements. This finding is consistent with medication adjustment by nurse or pharmacist (0.23%, 95% CI 0.05% to 0.42%) reported in a previous meta-regression analysis of quality improvement strategies, including case management. 160 Our findings suggest that text messaging and Web portals may be especially effective mechanisms for linking providers to patients with diabetes. The use of SMS text messaging may be feasible to communicate and motivate patients, which could result in positive outcomes.134 Although the trials we studied required providers to generate the text messages, it may prove feasible and less expensive to generate such messages by means of automated algorithms.92

There are various types of telemedicine interventions, including telehealth (clinical services provided at a distance6), telecare (often applied to non-clinical aspects of care such as mobility and safety27) and telemonitoring (remote collection and transmission of clinical data from patients to providers161). We primarily included trials in which patients received clinical feedback or communication from providers using some technology or devices. Therefore, we cannot differentiate trials that focused on telemonitoring or telecare in our review. Among the included trials, telemedicine interventions ranged from simple messages providing generic management suggestions for patients52,134 to more comprehensive interventions permitting videoconferencing with a nurse case manager, and remote monitoring of glucose and blood pressure with electronic data captured in the electronic medical record.133 This wide variation in interventions likely contributed to some of the observed heterogeneity, which was only partly explained by meta-regression.

Although our study is, to our knowledge, more comprehensive than previous studies of telemedicine in diabetes, our results are generally consistent with prior work showing beneficial effects of telemedicine on HbA1C. Compared with other systematic reviews, the relatively large number of studies that we identified allowed more detailed exploration of factors that may influence the magnitude of benefits on HbA1C. We were also able to show that effects on HbA1C diminished but were sustained over time and that benefits were more pronounced with more interactive interventions (e.g., Web portals and text messaging).

Limitations

Weaknesses of our systematic review include limitations of the constituent trials (small sample size, lack of blinding and relatively short duration). However, evidence suggests that lack of blinding would be less likely to affect an objectively assessed outcome such as HbA1C.162

Second, there was considerable variation in the types of telemedicine technology used, the type of care the control groups received and the populations studied. The variation may have contributed to the observed heterogeneity, and it may explain why some trials found positive effects of telemedicine and others found no benefit. However, we used meta-regression to identify which types of telemedicine interventions were particularly efficacious. The potential benefits of SMS text messaging and Web portals when used in conjunction with tailored (patient-specific) suggestions for medication adjustment suggest that these forms of intervention should be the highest priority for future uptake.

Third, as with all meta-regression analyses using summary data rather than individual participant data, our findings are vulnerable to the ecological fallacy (i.e., findings at the population level do not always translate correctly to individuals) and from limited statistical power.

Fourth, we did not collect data on the effects of telemedicine on satisfaction of care or its cost-effectiveness.163

Finally, we found some evidence of publication bias, which suggests that some small negative trials might exist, but they were not identified by our literature search. If this supposition were correct, it might lead to a slight overestimation of the efficacy of telemedicine interventions, but it would likely not affect our conclusion given that elimination of the outliers removed any significant publication bias.

Conclusion

Our systematic review showed that telemedicine may be a useful supplement to usual clinical care to control HbA1C, at least in the short term. Telemedicine interventions appeared to be most effective when they use a more interactive format, such as a Web portal or text messaging, to help patients with self-management.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Ghenette Houston for administrative support, and to Nasreen Ahmad and Sophanny Tiv for screening and data extraction.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Braden Manns has received a research grant from Baxter for work outside this study. No other competing interests were declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Marcello Tonelli and Braden Manns contributed to the study conception. Labib Faruque, Arash Ehteshami-Afshar, Natasha Wiebe and Marcello Tonelli designed the study. Labib Faruque, Arash Ehteshami-Afshar, Natasha Wiebe, Neda Dianati-Maleki and Yuanchen Liu screened and extracted data. Natasha Wiebe performed the statistical analyses. All of the authors contributed to the interpretation of data. Labib Faruque, Arash Ehteshami-Afshar, Natasha Wiebe and Marcello Tonelli drafted the manuscript; all of the authors revised it critically for important intellectual content, approved the final version to be published and agreed to act as guarantors of the work.

Funding: This work was supported by a team grant to the Interdisciplinary Chronic Disease Collaboration from Alberta Innovates – Health Solutions. Marcello Tonelli and Brenda Hemmelgarn are supported by an Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research Population Health Scholar Award. Brenda Hemmelgarn is supported by the Roy and Vi Baay Chair in Kidney Research. Braden Manns, Brenda Hemmelgarn and Marcello Tonelli are supported by an alternative funding partnership supported by Alberta Health and the Universities of Alberta and Calgary. The funding agencies had no role in study conception, study analysis or manuscript writing.

References

- 1.Chen L, Magliano DJ, Zimmet PZ. The worldwide epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus–present and future perspectives. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2011;8:228–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.IDF diabetes atlas. 6th ed. Brussels (Belgium): International Diabetes Federation; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 1993;329:977–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HA, et al. Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. BMJ 2000; 321:405–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ziemer DC, Miller CD, Rhee MK, et al. Clinical inertia contributes to poor diabetes control in a primary care setting. Diabetes Educ 2005; 31:564–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.What is telemedicine? Washington (DC): American Telemedicine Association; Available: www.americantelemed.org/about-telemedicine/what-is-telemedicine#.VRxj6PmjNcZ (accessed April 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 7.McLean S, Chandler D, Nurmatov U, et al. Telehealthcare for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;(10):CD007717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McLean S, Nurmatov U, Liu JL, et al. Telehealthcare for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;(7):CD007718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.AbuDagga A, Resnick HE, Alwan M. Impact of blood pressure telemonitoring on hypertension outcomes: a literature review. Telemed J E Health 2010;16:830–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inglis SC, Clark RA, McAlister FA, et al. Structured telephone support or telemonitoring programmes for patients with chronic heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010; CD007228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the chronic care model, Part 2. JAMA 2002;288:1909–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA 2002;288:1775–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siriwardena LS, Wickramasinghe WA, Perera KL, et al. A review of telemedicine interventions in diabetes care. J Telemed Telecare 2012;18:164–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farmer A, Gibson OJ, Tarassenko L, et al. A systematic review of telemedicine interventions to support blood glucose self-monitoring in diabetes. Diabet Med 2005;22:1372–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verhoeven F, Tanja-Dijkstra K, Nijland N, et al. Asynchronous and synchronous teleconsultation for diabetes care: a systematic literature review. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2010;4:666–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holtz B, Lauckner C. Diabetes management via mobile phones: a systematic review. Telemed J E Health 2012;18:175–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liang X, Wang Q, Yang X, et al. Effect of mobile phone intervention for diabetes on glycaemic control: a meta-analysis. Diabet Med 2011;28:455–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cassimatis M, Kavanagh DJ. Effects of type 2 diabetes behavioural telehealth interventions on glycaemic control and adherence: a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare 2012;18:447–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Polisena J, Tran K, Cimon K, et al. Home telehealth for diabetes management: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab 2009;11:913–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaana M, Pare G. Home telemonitoring of patients with diabetes: a systematic assessment of observed effects. J Eval Clin Pract 2007; 13:242–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Montori VM, Helgemoe PK, Guyatt GH, et al. Telecare for patients with type 1 diabetes and inadequate glycemic control: a randomized controlled trial and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2004; 27:1088–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marcolino MS, Maia JX, Alkmim MB, et al. Telemedicine application in the care of diabetes patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2013;8:e79246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baron J, McBain H, Newman S. The impact of mobile monitoring technologies on glycosylated hemoglobin in diabetes: a systematic review. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2012;6:1185–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balas EA, Krishna S, Kretschmer RA, et al. Computerized knowledge management in diabetes care. Med Care 2004;42:610–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.García-Lizana F, Sarría-Santamera A. New technologies for chronic disease management and control: a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare 2007; 13: 62–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paré G, Jaana M, Sicotte C. Systematic review of home telemonitoring for chronic diseases: the evidence base. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2007;14:269–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barlow J, Singh D, Bayer S, et al. A systematic review of the benefits of home telecare for frail elderly people and those with long-term conditions. J Telemed Telecare 2007;13:172–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sutcliffe P, Martin S, Sturt J, et al. Systematic review of communication technologies to promote access and engagement of young people with diabetes into healthcare. BMC Endocr Disord 2011;11:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shulman RM, O’Gorman CS, Palmert MR. The impact of telemedicine interventions involving routine transmission of blood glucose data with clinician feedback on metabolic control in youth with type 1 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Pediatr Endocrinol 2010;2010:536957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tran K, Polisena J, Coyle D, et al. Home telehealth for chronic disease management. Ottawa: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu L, Forbes A, Griffiths P, et al. Telephone follow-up to improve glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials. Diabet Med 2010; 27:1217–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009;339:b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jüni P, Altman DG, Egger M. Assessing the quality of randomised controlled trials. In: Egger M, Davey Smith G, Altman DG, editors. Systematic reviews in health care. 2nd ed. London (UK): BMJ Books; 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 1996;17:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ, et al. Empirical evidence of bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA 1995;273: 408–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chalmers TC, Smith H, Jr, Blackburn B, et al. A method for assessing the quality of a randomized control trial. Control Clin Trials 1981;2:31–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health 1998;52:377–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cho MK, Bero LA. The quality of drug studies published in symposium proceedings. Ann Intern Med 1996;124:485–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bassler D, Briel M, Montori VM, et al. Stopping randomized trials early for benefit and estimation of treatment effects: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. JAMA 2010;303:1180–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7:177–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wiebe N, Vandermeer B, Platt RW, et al. A systematic review identifies a lack of standardization in methods for handling missing variance data. J Clin Epidemiol 2006;59:342–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peters JL, Sutton AJ, Jones DR, et al. Contour-enhanced meta-analysis funnel plots help distinguish publication bias from other causes of asymmetry. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:991–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thompson SG, Higgins JP. How should meta-regression analyses be undertaken and interpreted? Stat Med 2002;21:1559–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ahring KK, Ahring JP, Joyce C, et al. Telephone modem access improves diabetes control in those with insulin-requiring diabetes. Diabetes Care 1992;15:971–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aliha JM, Asgari M, Khayeri F, et al. Group education and nurse-telephone follow-up effects on blood glucose control and adherence to treatment in type 2 diabetes patients. Int J Prev Med 2013;4:797–802. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Anderson DR, Christison-Lagay J, Villagra V, et al. Managing the space between visits: a randomized trial of disease management for diabetes in a community health center. J Gen Intern Med 2010;25:1116–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arora S, Peters AL, Burner E, et al. Trial to examine text message-based mHealth in emergency department patients with diabetes (TExT-MED): a randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med 2014;63:745–54.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Avdal EU, Kizilci S, Demirel N. The effects of web-based diabetes education on diabetes care results: a randomized control study. Comput Inform Nurs 2011;29:101–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bell AM, Fonda SJ, Walker MS, et al. Mobile phone-based video messages for diabetes self-care support. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2012;6:310–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Benhamou PY, Melki V, Boizel R, et al. One-year efficacy and safety of Webbased follow-up using cellular phone in type 1 diabetic patients under insulin pump therapy: the PumpNet study. Diabetes Metab 2007;33:220–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Biermann E, Dietrich W, Rihl J, et al. Are there time and cost savings by using telemanagement for patients on intensified insulin therapy? A randomised, controlled trial. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2002;69:137–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blackberry ID, Furler JS, Best JD, et al. Effectiveness of general practice based, practice nurse led telephone coaching on glycaemic control of type 2 diabetes: the Patient Engagement and Coaching for Health (PEACH) pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2013;347:f5272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bogner HR, Morales KH, de Vries HF, et al. Integrated management of type 2 diabetes mellitus and depression treatment to improve medication adherence: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med 2012;10:15–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bond GE, Burr R, Wolf FM, et al. The effects of a web-based intervention on the physical outcomes associated with diabetes among adults age 60 and older: a randomized trial. Diabetes Technol Ther 2007;9:52–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]