Abstract

Background

Patients with liver metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) often benefit from receiving 90Y-microsphere radioembolization (RE) administered via the hepatic arteries. Prior to delivery of liver-directed radiation, standard laboratory tests may assist in improving outcome by identifying correctable pre-radiation abnormalities.

Methods

A database containing retrospective review of consecutively treated patients of mCRC from July 2002 to December 2011 at 11 US institutions was used. Data collected included background characteristics, prior chemotherapy, surgery/ablation, radiotherapy, vascular procedures, 90Y treatment, subsequent adverse events and survival. Kaplan-Meier estimates compared the survival of patients across lines of chemotherapy. The following values were obtained within 10 days prior to each RE treatment: haemoglobin (HGB), albumin, alkaline phosphatase (Alk phosph), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine transaminase (ALT), total bilirubin and creatinine. Common Terminology Criteria Adverse Events (CTCAEs) 3.0 grade was assigned to each parameter and analysed for impact on survival by line of chemotherapy. Consensus Guidelines were used to categorize the parameter grades as either within or outside guidelines for treatment.

Results

A total of 606 patients (370 male; 236 female) were studied with a median follow-up was 8.5 mo. (IQR 4.3–15.6) after RE. Fewer than 11% of patients were treated outside recommended RE guidelines, with albumin being the most common, 10.5% grade 2 (<3–2.0 g/dL) at time of RE. All seven parameters showed statistically significant decreased median survivals with any grade >0 (P<0.001) across all lines of prior chemotherapy. Compared to grade 0, grade 2 albumin decreased overall survival 67%; for grade 2 total bilirubin a 63% drop occurred, and grade 1 HGB resulted in 66% lower median survival.

Conclusions

Review of pre-RE laboratory parameters may aid in improving median survivals if correctable grade >0 values are addressed prior to radiation delivery. HGB <10 g/dL is a well-known negative factor in radiation response and is easily corrected. Improving other parameters is more challenging. These efforts are important in optimizing treatment response to liver radiotherapy.

Keywords: 90Y Microspheres, selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT), metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC); radioembolization (RE); internal radiation therapy; liver-dominant metastatic colorectal cancer; radiotherapy, brachytherapy

Introduction

Colorectal cancer is the third most common can¬cer and the second most common cause of cancer death in developed countries (1). The mainstay for the management of metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) is chemotherapy ± biologic therapies (2). Drug and regimen advances in systemic therapy (3) have substantially improved median survivals over the last decades and provided a meaningful window for the localized control of liver metastases (a common presentation in mCRC patients), especially whenever the extrahepatic disease appears to have an indolent clinical course. Liver-directed approaches to therapy are used to treat: (I) discrete, visually-targeted tumors using resection, ablation, NanoKnife® (U/S), irreversible electroporation (IRE), or stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT); and (II) more, widespread, multinodular disease in the liver using selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT), also known as radioembolization (RE) (4). Encouraging evidence suggests that there might be a potential synergy between systemic therapy and the use of loco-regional approaches to improve outcomes in mCRC patients (5,6). When we combined the skills of radiation oncologists, medical oncologists, oncologic surgeons, interventional radiologists, and nuclear medicine experts, we found that a sustained clinical response (not usually observed with chemotherapy alone) can be achieved in the liver, perhaps even slowing the spread of disease beyond the liver when used earlier in the treatment paradigm (7). However, most candidates for RE have been heavily pre-treated with more or less all-available systemic agents. In a prospective randomized study of 44 such patients with liver-only disease, researchers found that patients who received RE plus 5-fluorouracil (FU) in the chemo-refractory setting significantly benefited from a longer time to progression of target liver lesions compared with FU alone (5.5 vs. 2.1 months) (5). The management of patients with mCRC is evolving from an empiric chemotherapy approach to a more individually tailored-approach, which is focused on identifying molecular biomarkers and/or disease characteristics that can predict response and/or toxicity to systemic and/or liver-directed treatments.

The mCRC liver metastases outcomes after radioembolization (MORE) study represents a unique repository comprising data of consecutive patients with unresectable, liver-dominant mCRC, who received RE between July 2002 and December 2011. In the MORE retrospective cohort analyses, our objectives were to: (I) investigate the safety and survival impacts of pretreatment, laboratory parameters on outcomes following RE in the chemotherapy refractory setting; (II) identify potentially correctable pre-radiation abnormalities, which may assist in improving treatment outcomes beyond the current recommended RE guidelines (Table 1); and (III) examine the impact of prior chemotherapy (in patients stratified by line of therapy) on standard liver function tests (LFT) and haemoglobin (HGB) prior to rescue treatment with RE.

Table 1. Patient selection criteria upon initial investigation (prior to detailed work-up) for RE with 90Y-resin microspheres from 2002 onwards.

| Inclusion criteria |

| Adult patients ria years |

| WHO/ECOG performance status: 2 |

| Life expectancy of at least 3 months* |

| Liver-dominant metastases from colorectal cancer not treatable by surgical resection or local ablation with curative intent (determined by multidisciplinary team) |

| Progressed or become intolerant to at least one line of systemic therapy |

| LFT: |

| ALT ≤200 U/L |

| AST ≤175 U/L |

| Alk phosph ≥630 U/L |

| Serum bilirubin less than 2 mg/dL (34.2 µmol/L) (in the absence of a reversible cause*) |

| Serum albumin more than 30 U/L (or 3 mg/dL) |

| Serum creatinine greater than 2.5/dL |

| Adequate hematologic function (based on complete blood count with differential platelet counts >60,000/ìL, leukocytes >2,500/ìL; neutrophil count >1,500/ìL; prothrombin time and partial thromboplastin time and INR in normal range or can be corrected to normal prior to the procedure; hemoglobin not defined) |

*, additional recommendations from REBOC) 2007. INR, international normalized ratio; RE, radioembolization; Alk phosph, alkaline phosphatase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine transaminase; LFT, liver function tests; REBOC, Radioembolization Brachytherapy Oncology Consortium.

Methods

MORE was a retrospective observational study (clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT01815879) of consecutive patients who received RE with yttrium-90 (90Y)-resin microspheres (SIR-Spheres®; Sirtex Medical, Sydney, Australia) at 11 United States (US) institutions, chosen for their experience with RE techniques. The methods used to obtain and collect the data were previously described (8). An institution review board granted exemptions prior to the collection of data at each site.

The US institutions were guided in the selection of patients, pre-treatment work-up, and dosimetry (using body surface area methodology) by the published consensus from the Radioembolization Brachytherapy Oncology Consortium (REBOC) and other earlier reviews (4,9,10). During the pre-treatment work-up, patients were excluded from RE if there was evidence of any uncorrectable blood flow to non-target sites—gastrointestinal tract or other extra-hepatic organs—observed on angiography or Technetium-99m macroaggregated albumin (99mTc-MAA) scan. Based on the clinical judgment of the multidisciplinary team, some patients, under exceptional circumstances and with informed consent, were treated outside the recommended criteria (Table 1). Study patients received a median of two RE procedures [delivering 1.46 (range, 0.11–5.51) GBq of total 90Y activity] mainly using either a whole liver (65.7%) approach or right lobar (27.7%) l approach; the design (i.e., number, sequence and time between each RE procedure was previously reported (8,11). In 98% of cases, hospitalization after each procedure was less than 24 hours.

Data collection and analysis

The following values were obtained within 10 days prior to RE: HGB, albumin, alkaline phosphatase (Alk phosph), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine transaminase (ALT), total bilirubin, and creatinine. The nature and severity of all AEs were graded using the CTC version 3.0 (CTC v3) (12). The highest grade occurring at any time between day 0 and 90 post-procedure was reported.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using statistical analysis software (SAS) (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Where applicable, the most recently published Consensus Guidelines and/or clinical trial selection criteria were used to establish the abnormal limits for RE (Table 1). Summary statistics of continuous variables included the number of non-missing observations, the mean, standard deviation, interquartile range, median, minimum, and maximum values. Statistical significance was tested at two-sided p=0.05, without adjustment for multiple comparison, or imputation of missing values. Median follow-up time was calculated using the reverse Kaplan-Meier method on the time to death. The association between LFT categorical variables and CTC grade and LFT variables and prior chemotherapy was tested by the Chi-square test.

Overall survival time was measured from the date of the first SIRT procedure until recorded date of death or loss to follow-up. Median survival was estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method. Proportional hazards models were applied to evaluate the consistency and robustness of the treatment effect over strata, and include the model estimate, standard error, hazard ratio (HR), and 95% confidence interval (CI) of the HR. AEs terminology reporting is standardized using the medical dictionary for Regulatory Authorities (MedDRA). The number and percentage of subjects reporting treatment-emergent AEs were tabulated using System Organ Class (SOC) and preferred term. For summaries by preferred term and by SOC, subjects with more than one AE were counted once.

Results

Of 606 consecutive patients in the study with a diagnosis of mCRC who received at least one RE procedure (Table 2), median follow-up was 9.6 months, 95% CI: 9.0–11.1 months. Five hundred and three deaths were reported, and 103 patients were censored.

Table 2. Baseline patient, disease and treatment characteristics (n=606).

| Parameter | Category | Number |

|---|---|---|

| ECOG performance status, n=257 (%) | 0 | 168 (65.4) |

| 1 | 72 (28.0) | |

| 2–3 | 17 (6.6) | |

| Site of primary, n=576 (%) | Colon:Rectum | 443 (76.9):133 (23.1) |

| Primary tumor in situ, n (%) | — | 78 (12.9) |

| Metastases, n=569 (%) | Metachronous:Synchronous | 173 (30.4):396 (69.6) |

| Extrahepatic metastases, n (%) | Yes:No | 213 (35.1):393 (64.9) |

| Lung | 148 (24.4) | |

| Lymph node | 67 (11.1) | |

| Peritoneum | 17 (2.8) | |

| Bone | 30 (5.0) | |

| Other | 38 (6.3) | |

| CEA, µg/L | Median (IQR) | 62.2 (283.4) |

| Ascites, n (%) | Yes | 28 (4.6) |

| Prior lines of systemic chemotherapy for mCRC, n (%) | None (90Y-RE at 1st-line) | 35 (5.8) |

| 1 line of chemotherapy | 206 (34.0) | |

| 2 lines of chemotherapy | 184 (30.4) | |

| ≥3 lines of chemotherapy | 158 (26.1) | |

| Unknown | 23 (3.8) |

ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; mCRC, metastatic colorectal cancer; RE, radioembolization; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen.

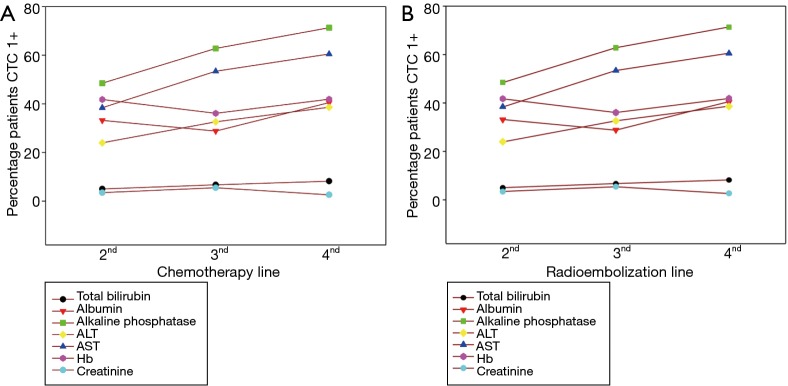

RE was administered as a second-line, third-line or fourth-plus line of therapy in 35.3%, 32.6% and 27.1% of patients in the study, respectively—mostly during a chemotherapy holiday or in patients who were either intolerant or refractory to systemic chemotherapy. Six percent of cases received RE first-line, mainly due to significant comorbidities or intolerance to prior adjuvant chemotherapy for the treatment of the primary tumor. Eighty three point two percent (501 of 606) of patients in the Study had at least one pretreatment laboratory value beyond the normal limits, CTC grade >0. Results of stratification of patients by prior chemotherapy showed the proportion of patients and the severity of abnormal pretreatment values rose significantly (P<0.01) with increasing lines of RE and chemotherapy for ALT, AST and Alk phosph but not for total bilirubin, albumin, creatinine, and HGB levels (Figure S1). Fewer than 13.6% of study patients were treated because one or more laboratory parameters were outside current recommended RE guidelines. Pretreatment CTC grade 2-plus changes in albumin (<3 g/dL) was the most common reason for non-adherence in 12% of patients (Table S1). The non-adherence guideline did not increase significantly in patients who received RE after more lines of prior chemotherapy; however, the proportion of patients with Alk phosph >300 U/L rose significantly from 13.6% to 27.4% (P=0.001) when RE was given second-line versus fourth-plus line, respectively. Additionally, there was a non-significant rise (from 1.0% to 3.8%; P=0.073) in patients with total bilirubin beyond the recommended limit for RE of 2 mg/dL in the second-line and fourth-plus line setting, respectively.

Safety results

Overall, RE was well tolerated; the most commonly reported AEs (grades 1–2 and grade 3+) within 90 days post-treatment were gastrointestinal (41.4% and 10.2%); constitutional (39.8% and 6.4%) and hepatobiliary (11.4% and 8.6%). Study patients (34%) who showed abnormal changes in albumin at baseline had an increased risk of grade 3+ AEs over the 90 days after RE (P=0.013): specifically grade 3+ constitutional symptoms (fatigue) and hepatobiliary signs and symptoms (hyperbilirubinemia) (Tables 3, S2).

Table 3. Summary of significant differences in the reporting of all grades and severe (CTCAE grade ≥3) all-causality adverse events over day 0–90 from first RE procedure in A. Patients with and without abnormal baseline laboratory parameters and B. In patients with at least grade 2 baseline laboratory parameters compared with those no or only mild changes in baseline laboratory parameters.

| System organ, class | Baseline CTCAE grade ≥1 vs. Grade 0 | Baseline CTCAE grade ≥2 vs. Grade ≤1 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilirubin (n=37) | Albumin (n=199) | Alk Phos (n=351) | ALT (n=175) | AST (n=294) | Hemoglobin (n=238) | Albumin (n=72) | Alk Phos (n=99) | Hemoglobin (n=58) | ||

| Total | Grade ≥3 | Grade ≥3 | Grade ≥3*, all grades* | Grade ≥3*, all grades | Grade ≥3* | |||||

| Gastrointestinal | All grades | |||||||||

| Abdominal pain | All grades | |||||||||

| Nausea | All grades* | All grades | ||||||||

| Abdominal distension | All grades | |||||||||

| Intestinal obstruction | All grades | |||||||||

| Flatulence | All grades | |||||||||

| Constitutional | Grade ≥3 | Grade ≥3 | Grade ≥3*, all grades | Grade ≥3*, all grades | Grade ≥3 | |||||

| Fatigue | Grade ≥3 | Grade ≥3 | Grade ≥3*, all grades | Grade ≥3* | ||||||

| Fever | All grades* | All grades | All grades* | |||||||

| Peripheral edema | Grade ≥3 | |||||||||

| Psychiatric | All grades | All grades | ||||||||

| Anorexia nervosa | All grades | |||||||||

| Hepatobiliary | Grade ≥3*, all grades* | Grade ≥3 | All grades* | All grades | All grades* | Grade ≥3*, all grades* | Grade ≥3*, all grades* | |||

| Hyperbilirubinemia | All grades* | Grade ≥3, all grades | All grades* | All grades* | All grades* | Grade ≥3*, all grades* | Grade ≥3*, all grades* | Grade ≥3 | ||

| Ascites | All grades | |||||||||

| REILD | Grade ≥3, all grades | |||||||||

| Hepatic failure | Grade ≥3*, all grades | Grade ≥3, all grades | ||||||||

| Respiratory | Grade ≥3 | |||||||||

| Influenza | All grades | |||||||||

*, P value <0.01. REILD, radioembolization-induced liver disease; CTCAEs, Common Terminology Criteria Adverse Events; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine transaminase; Alk phosph, alkaline phosphatase;.

The 59% of patients who had an abnormal (grade >0) Alk phosph at baseline had a significantly greater risk of any AEs (P=0.001) or grade 3+ (P=0.002) AEs, and specifically a rise in any or grade 3+ constitutional symptoms (fatigue grade 3+ and any fever), and any but not grade 3+, hepatobiliary events; this trend was mirrored for patients with raised pretreatment AST levels (grade >0). Patients with low HGB levels at baseline did not have any increased incidence of AEs overall or hepatobiliary events, but were significantly more likely to present with gastrointestinal AEs (any grade, but not grade 3 + events) and particularly abdominal pain and nausea.

The total reported incidence of grade 3+ hepatitis and radioembolization-induced liver disease (REILD) within 90 days post-treatment was 0.8% and 0.5%, respectively. Raised total bilirubin (all grades; all causality including liver progression) was recorded in 6.2% of study patients at baseline, increasing to 22.6% of study patients by day 90 following the first treatment, with a minority experiencing grade 3 (4.9%) or 4 (2.7%) events at day 90. Although REILD was a rare event, the 6.2% of patients who had raised total bilirubin (grade >0) at baseline had a significantly greater risk of REILD and hepatic failure compared to patients with normal baseline total bilirubin levels (Tables S2,S3,S4). Raised bilirubin was the only observed pretreatment laboratory value that predicted REILD in this study (Table 3).

Survival results

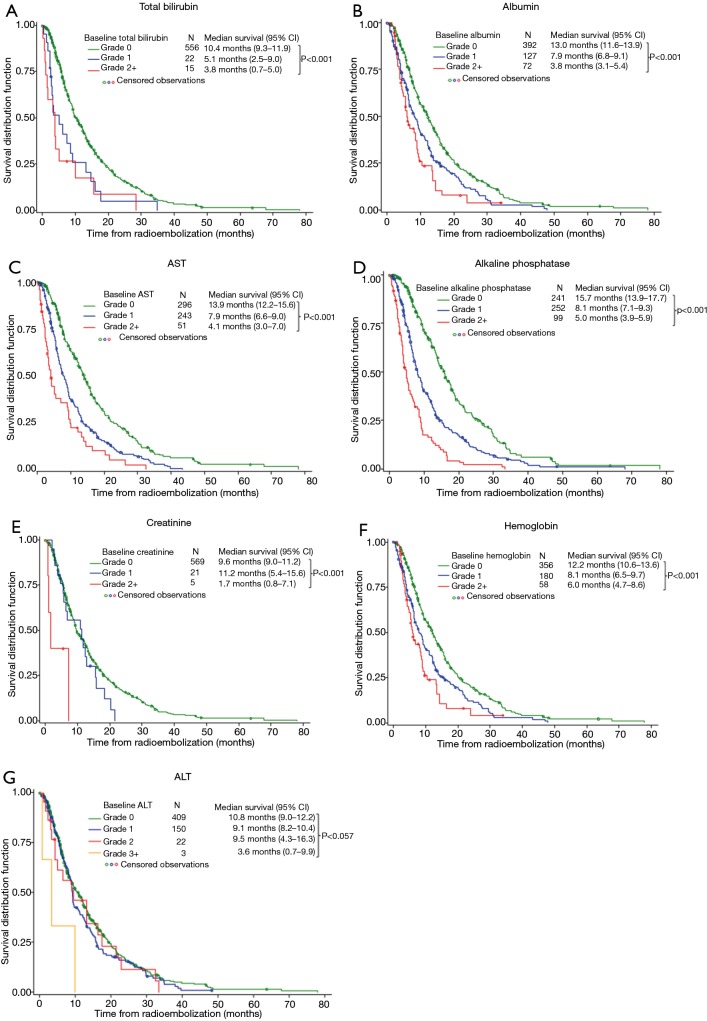

Kaplan-Meier analysis of the overall cohort found that median survivals significantly decreased with increasing severity of pretreatment laboratory parameters (beyond CTC grade 0), and this trend was consistent across all cohorts, regardless of the number of prior lines of chemotherapy (Table S5).

Univariate analysis found that for each increasing grade of dysfunction, Alk phosph (HR 1.9), total bilirubin (HR 1.8), and AST (HR 1.7) were the most predictive of diminishing overall survival (Figure 1). Compared with patients who had normal laboratory values at baseline, median overall survivals were significantly reduced in patients who were treated outside the current RE guidelines for all parameters evaluated (Table 4). Any pretreatment grade beyond the norm (CTC grade 0) for total bilirubin, albumin, Alk phosph and AST, but not ALT or creatinine, was associated with significantly shorter survivals.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of survival by baseline laboratory values.

Table 4. Impact on baseline laboratory values on survival following RE (any abnormality and beyond current guidelines).

| Parameter | Any abnormal laboratory value (CTCAE >0) | Outside current guidelines | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value* | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value* | ||

| Total bilirubin | 2.2 (1.6–3.1) | <0.001 | 3.1 (1.7–5.6) | <0.001 | |

| Albumin | 2.0 (1.6–2.4) | <0.001 | 3.2 (2.5–4.2) | <0.001 | |

| Alk Phos | 2.2 (1.8–2.6) | <0.001 | 2.8 (2.2–3.5)** 6.8 (4.2–11.06) |

<0.001 | |

| ALT | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) | 0.117 | 3.6 (1.1–11.1) | 0.029 | |

| AST C | 1.9 (1.6–2.3) | <0.001 | 5.3 (2.7–10.4) | <0.001 | |

| Creatinine | 1.5 (1.0–2.4) | 0.043 | 6.0 (1.9–18.8) | 0.002 | |

| Hemoglobin <10 g/dL | 1.8 (1.3–2.5) | <0.001 | Not applicable | — | |

*, Cox poroportional hazards model; **, Alk phosph >300 U/L; ***, Alk phosph >630 U/L. CTCAEs, Common Terminology Criteria Adverse Events; CI, ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; Alk phosph, alkaline phosphatase.

HGB levels are not defined by the RE guidelines; however, we found that a pretreatment anemia (defined as HGB <10 g/dL) significantly reduced overall survival (HR 1.8; 95% CI: 1.3–2.5]; P<0.001) compared with patients with normal baseline levels (Table 4).

Discussion

The MORE study provides important insights into the impact of standard laboratory tests on prior identification of correctable pre-radiation abnormalities before delivery of liver-directed radiation and thereby assist in improving outcome.

Pre-treatment liver dysfunction affects outcomes after RE

It was previously established that pre-treatment liver dysfunction affects outcomes and tolerability to first-line chemotherapy (13). A variety of baseline laboratory data were evaluated in prospective chemotherapy studies and found to predict treatment outcome including: elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (14,15), white blood cell (WBC) count (15,16), serum albumin (17), elevated liver transaminases (18), Alk phosph (19), and HGB (20). In a pooled analysis of source data from >3,800 patients treated with FU-based treatments (21) and a subsequent analysis of >1,600 patients from Intergroup trial N9741 of FU-, oxaliplatin-, and irinotecan-containing chemotherapy regimens (13), three prognostic groups (low, intermediate, and high risk) were identified in the first-line setting according to the following baseline factors: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS), WBC, Alk phosph, and number of sites of metastatic disease (the Kohne criteria) (21). The intergroup (N9741) study also showed that the odds of experiencing any grade 3 or greater toxicity were significantly increased in patients with raised baseline total bilirubin and Alk phosph levels (13). It is not surprising that pre-treatment laboratory values also affect overall survival and safety outcomes with RE in the refractory setting.

RE is a highly safe therapy

RE is a form of intra-arterial brachytherapy where high-localized doses of beta radiation are delivered to the tumoral tissue relative to non-tumoral tissue (22). The primary consideration for the application of RE is safety, which can be achieved through the correct selection of patients and use of an appropriate treatment approach (23) e.g., by decreasing the treated volume (using lobar or segmental treatment approach) or prescribed activity of yttrium-90. The low incidence of overall, as well as, grade 3+ AEs in this intention-to-treat analysis is testament to the ongoing process of patient selection and audit at most specialized centers, where risks associated with RE are continuously monitored and an adaptive approach is implemented to improve safety. A conservative approach was adopted in the majority of patients in this study, as the treatment intent was palliation (extending in overall survival where possible without impacting of quality of life). Recognizing the limitations of 90Y-RE in patients with severe liver dysfunction is key to optimizing patient outcomes. However, especially in the palliative setting, it is difficult to balance, improving the patient’s health status and their ability to tolerate treatment better, without leaving treatment until it is too late to have a significant impact on survival.

We found that although any abnormal changes in Alk phosph, ALT, AST, or albumin at baseline were associated with an increased risk of hyperbilirubinemia post-treatment, only raised pretreatment bilirubin, found in 6% of study patients, was significantly associated with an increased risk of REILD, which is a serious, but fortunately rare event, observed in 0.5% of patients in this cohort. REILD is a form of sinusoidal obstruction syndrome appearing 4 to 8 weeks after RE, described in non-cirrhotic patients as jaundice, mild ascites, and a moderate increase in gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGTP) and Alk phosph (24). Factors that impact the occurrence of REILD include: prior liver function and functional reserve and prior or concurrent use of other antineoplastic therapies (25,26).

Liver function trend and cumulative chemotherapy prior to RE

MORE study data show that with each successive line of prior chemotherapy, the frequency of reported abnormal pre-RE, AST, ALT and Alk phosph levels increased, including total bilirubin beyond the recommended guidelines for RE. Therefore, a review of liver function trends in the months prior to 90Y should be performed to optimize patient selection. These study data suggest that the use of RE earlier in the treatment course would not only improve tolerability to RE, but also increase the number of patients potentially eligible for RE. Studies of the relative safety and efficacy of chemotherapy, with or without RE, in the first-line setting for unresectable liver-dominant mCRC are now the subject of extensive analysis in three ongoing prospective phase 3 trials (27-29).

Anemia and RE

Data also suggest that if anemia (i.e., HGB <10 g/dL) was corrected with either a blood transfusion or subcutaneous erythropoietin (EPO) prior to RE, median survivals (as well as tolerability to GI events) could be potentially improved. A strategy of reducing anemia prior to radiotherapy with external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) or brachytherapy including RE (30-34), is supported by wealth of published evidence indicating that a low HGB level before or during radiation therapy is an important risk factor for poor survival and/or locoregional disease control. The more hypoxic environment of solid tumors is associated with decreased radiosensitivity thereby enabling malignant cells to remain viable, especially in patients with anemia (35). Clinically significant anemia is believed to be one cause of intratumoral hypoxia, which is a well-known negative factor in radioresistance of solid tumors (36). Oxygen is the most important agent enabling maximal tumor sensitivity to ionizing radiation, as demonstrated by numerous preclinical studies. The magnitude of enhancement of radiation effect is a factor of between 2 and 3 times over hypoxic conditions receiving the same radiation treatment. Prospective clinical trials in a variety of tumor types have associated pre-radiotherapy hypoxia (2.5–10 mm Hg partial pressure of oxygen) with statistically significant reductions in local control, disease free survival and overall survival via multivariate analyses (35,36). A recent report analyzing anemia in cervical cancer patients suggested anemia during radiotherapy (external beam and brachytherapy) with our without concurrent chemotherapy was not an independent predictor of central recurrence (37).

The fact that MORE was a retrospective analysis is the chief limitation of the study; however, all patients treated during the pre-specified period were included in all evaluations. Patients were also selected from specialist tertiary care centers and (previously shown in evaluation of the elderly versus the young), there was an inevitable selection bias at these centers towards younger and/or fitter patients; although, elderly and young patients were found to tolerate the treatment equally well (38).

Conclusions

MORE data support previous analyses, which show that low HGB (18,21) and low albumin (39), as well as, Alk phosph (≥300 U/L) (13,21) and AST (18) are recognized factors that are predictive for shorter survival in mCRC. However, if disease-related anemia and treatment-related anemia can be limited, RE can be performed more efficiently. A review of pre-treatment laboratory parameters may improve median survivals if correctable values (e.g., HGB <10 g/dL) are addressed prior to RE. Liver function trends prior to use of RE should always be considered, especially in the chemotherapy refractory setting, and the calculated activity of 90Y adapted accordingly for each patient to optimize outcome.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Mark Van Buskirk for his outstanding statistical work and advice; and Rae Hobbs for her editorial assistance.

Funding: This was an investigator-initiated study funded by Sirtex Medical Limited, Sydney, Australia through an educational grant awarded to Dr. Kennedy, Sarah Cannon Research Institute. AS Kennedy, D Ball, NK Sharma received grants for clinical trials from Sirtex Medical; E Ehrenwald, S Kanani, S Schirm have nothing to disclose.

Figure S1.

Graphs of adverse events and association with line of chemotherapy and RE. (A) Association of prior chemotherapy line with CTCAE Grade 1+; (B) association between treatment setting for RE (according prior line of chemotherapy) and proportion of patients with baseline CTCAE Grade >0. CTCAE, Common Terminology Criteria Adverse Events; RE, radioembolization.

Table S1. Baseline patient and disease characteristics (n=606).

| Parameter | Category | Number |

|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | Female:Male | 233 (38.4):373 (61.6) |

| Age, n (%) | Mean ± SD [range] | 61.5±12.7 [20.8–91.9] |

| ≥70 years | 160 (26.4) | |

| ≥75 years | 98 (16.2) | |

| Race, n=512 (%) | White or Caucasian | 398 (77.7) |

| Black or African American | 67 (13.1) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 17 (3.3) | |

| Asian/other | 12 (2.3)/18 (3.5) | |

| ECOG performance status, n=257 (%) | 0 | 168 (65.4) |

| 1 | 72 (28.0) | |

| 2–3 | 17 (6.6) | |

| Site of primary, n=604 (%) | Colon | 443 (73.3) |

| Rectum | 133 (22.0) | |

| Colorectal | 28 (4.6) | |

| Primary tumor in situ, n (%) | − | 78 (12.9) |

| Metastases, n=569 (%) | Metachronous:Synchronous | 173 (30.4):396 (69.6) |

| Extrahepatic metastases, n (%) | Yes:No | 213 (35.1):393 (64.9) |

| Lung | 148 (24.4) | |

| Lymph node | 67 (11.1) | |

| Peritoneum | 17 (2.8) | |

| Bone | 30 (5.0) | |

| Other | 38 (6.3) | |

| CEA, µg/L | Median (IQR) | 62.2 (283.4) |

| Ascites, n (%) | Yes | 28 (4.6) |

| Prior lines of systemic chemotherapy for mCRC, n (%) | None (90Y-RE at 1st-line) | 35 (5.8) |

| 1 line of chemotherapy (90Y-RE at 2nd-line) | 206 (34.0) | |

| 2 lines of chemotherapy (90Y-RE at 3rd-line) | 184 (30.4) | |

| ≥3 lines of chemotherapy (90Y-RE at ≥4th-line) | 158 (26.1) | |

| Unknown | 23 (3.8) | |

| Time since identification of mCRC to RE, months | Median (range) | 16.3 (0.4–96.3) |

| Tumor-to-target liver involvement at first 90Y-RE, % | Median (range) | 15 (0.1–100) |

CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; mCRC, metastatic colorectal cancer; RE, radioembolization.

Table S2. Proportion of patients who received RE within and beyond recommended guidelines.

| Parameter | CTCAE grade† | Values | N (%) patients |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0 | ≤1.3 | 556 (94.0) |

| 1 | >1.3–1.95 | 22 (4.0) | |

| 2 | >1.95–3.9 | 13 (2.0) | |

| 3 | >3.9–13.0 | 1 (0.2) | |

| 4 | >13.0 | 1 (0.2) | |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 0 | ≥3.5 | 392 (66.0) |

| 1 | <3.5–3.0 | 127 (21.0) | |

| 2 | <3.0–2.0 | 64 (11.0) | |

| 3 | <2.0 | 8 (1.0) | |

| ALT (U/L) | 0 | ≤40 | 409 (70.0) |

| 1 | >40–100 | 150 (26.0) | |

| 2 | >100–200 | 22 (4.0) | |

| 3 | >200–800 | 2 (0.3) | |

| 4 | >800 | 1 (0.2) | |

| AST (U/L) | 0 | ≤35 | 296 (50.0) |

| 1 | >35–87.5 | 243 (41.0) | |

| 2 | >87.5–175 | 42 (7.0) | |

| 3 | >175–700 | 9 (1.0) | |

| Alk phosph (U/L) | 0 | ≤126 | 241 (41.0) |

| 1 | >126–315 | 252 (43.0) | |

| 2 | >315–630 | 81 (14.0) | |

| 3 | >630–2,520 | 18 (3.0) | |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0 | ≤1.4 | 569 (96.0) |

| 1 | >1.4–2.1 | 21 (3.0) | |

| 2 | >2.1–4.2 | 3 (0.5.) | |

| 3 | >4.2–8.4 | 2 (0.3) | |

| 4 | >8.4 | 0 | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 0 | ≥12.0 | 356 (60.0) |

| 1 | <12.0–10.0 | 180 (30.0) | |

| 2 | <10.0–8.0 | 54 (9.0) | |

| 3 | <8.0–6.5 | 4 (1.0) |

†, CTCAE version 3.0. CTCAE, Common Toxicity Criteria Adverse Events; ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; Alk phosph, alkaline phosphatase.

Table S3. Summary of significant differences in the reporting of all grades and severe (CTCAE: grade ≥3) all-causality adverse events between days 0–90 from first 90Y-RE procedure in patients with and without abnormal laboratory parameters.

| Parameter | System organ, class | Baseline grade 0, n (%) | Baseline grade ≥1, n (%) | P value for all grades† | P value for grade ≥3‡ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTCAE grade | All grades | Grade ≥3 | All grades | Grade ≥3 | ||||

| Baseline bilirubin, grade 0 (n=556), grade ≥1 (n=37) | Total patients | 375 (67.4) | 96 (17.3) | 26 (70.3) | 13 (35.1) | 0.856 | 0.014 | |

| Constitutional | 252 (45.3) | 27 (4.9) | 15 (40.5) | 6 (16.2) | 0.612 | 0.012 | ||

| Fatigue | 234 (42.1) | 23 (4.1) | 14 (37.8) | 6 (16.2) | 0.731 | 0.006 | ||

| Psychiatric | 40 (7.2) | 4 (0.7) | 7 (18.9) | 1 (2.7) | 0.020 | 0.276 | ||

| Anorexia nervosa | 39 (7.0) | 4 (0.7) | 7 (18.9) | 1 (2.7) | 0.018 | 0.276 | ||

| Hepatobiliary | 65 (11.7) | 27 (4.9) | 14 (37.8) | 7 (18.9) | <0.001 | 0.003 | ||

| Hyperbilirubinemia | 43 (7.7) | 14 (2.5) | 11 (29.7) | 3 (8.1) | <0.001 | 0.083 | ||

| Ascites | 16 (2.9) | 9 (1.6) | 4 (10.8) | 2 (5.4) | 0.030 | 0.146 | ||

| REILD | 7 (1.3) | 1 (0.2) | 3 (8.1) | 2 (5.4) | 0.020 | 0.011 | ||

| Hepatic failure | 2 (0.4) | 0 | 2 (5.4) | 2 (5.4) | 0.021 | 0.004 | ||

| Baseline albumin, grade 0 (n=392), grade ≥1 (n=199) | Total patients | 261 (66.6) | 61 (15.6) | 138 (69.3) | 48 (24.1) | 0.517 | 0.013 | |

| Intestinal obstruction | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 4 (2.0) | 3 (1.5) | 0.046 | 0.113 | ||

| Constitutional | 176 (44.9) | 16 (4.1) | 90 (45.2) | 17 (8.5) | 1.000 | 0.036 | ||

| Fatigue | 164 (41.8) | 14 (3.6) | 83 (41.7) | 15 (7.5) | 1.000 | 0.043 | ||

| Hepatobiliary | 45 (11.5) | 16 (4.1) | 33 (16.6) | 18 (9.0) | 0.095 | 0.023 | ||

| Hyperbilirubinemia | 26 (6.6) | 6 (1.5) | 27 (13.6) | 11 (5.5) | 0.009 | 0.009 | ||

| Influenza | 11 (2.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.019 | Na | ||

| Baseline ALP, grade 0 (n=241), grade ≥1 (n=351) | Total patients | 144 (59.8) | 30 (12.4) | 255 (72.6) | 78 (22.2) | 0.001 | 0.002 | |

| Constitutional | 86 (35.7) | 7 (2.9) | 179 (51.0) | 26 (7.4) | <0.001 | 0.018 | ||

| Fatigue | 83 (34.4) | 6 (2.5) | 163 (46.4) | 23 (6.6) | 0.004 | 0.032 | ||

| Fever | 7 (2.9) | 0 | 36 (10.3) | 2 (0.6) | <0.001 | 0.516 | ||

| Psychiatric | 12 (5.0) | 3 (1.2) | 34 (9.7) | 2 (0.6) | 0.042 | 0.402 | ||

| Hepatobiliary | 17 (7.1) | 9 (3.7) | 61 (17.4) | 24 (6.8) | <0.001 | 0.144 | ||

| Hyperbilirubinemia | 8 (3.3) | 5 (2.1) | 45 (12.8) | 12 (3.4) | <0.001 | 0.455 | ||

| Baseline ALT, grade 0 (n=409), grade ≥1 (n=175) | Total patients | 270 (66.0) | 70 (17.1) | 124 (70.9) | 36 (20.6) | 0.289 | 0.349 | |

| Fever | 24 (5.9) | 2 (0.5) | 19 (10.9) | 0 | 0.039 | 1.000 | ||

| Hepatobiliary | 45 (11.0) | 20 (4.9) | 33 (18.9) | 13 (7.4) | 0.016 | 0.242 | ||

| Hyperbilirubinemia | 28 (6.8) | 11 (2.7) | 25 (14.3) | 6 (3.4) | 0.007 | 0.600 | ||

| Baseline AST, grade 0 (n=296), grade ≥1 (n=294) | Total patients | 186 (62.8) | 41 (13.9) | 212 (72.1) | 67 (22.8) | 0.018 | 0.006 | |

| Constitutional | 119 (40.2) | 8 (2.7) | 146 (49.7) | 25 (8.5) | 0.025 | 0.002 | ||

| Fatigue | 112 (37.8) | 7 (2.4) | 134 (45.6) | 22 (7.5) | 0.066 | 0.004 | ||

| Hepatobiliary | 23 (7.8) | 11 (3.7) | 54 (18.4) | 22 (7.5) | <0.001 | 0.050 | ||

| Hyperbilirubinemia | 12 (4.1) | 6 (2.0) | 40 (13.6) | 11 (3.7) | <0.001 | 0.230 | ||

| Baseline hemoglobin, grade 0 (n=356), grade ≥1 (n=238) | Total patients | 239 (67.1) | 62 (17.4) | 159 (66.8) | 47 (19.7) | 0.929 | 0.517 | |

| Gastrointestinal | 191 (53.7) | 31 (8.7) | 106 (44.5) | 20 (8.4) | 0.036 | 1.000 | ||

| Abdominal pain | 146 (41.0) | 19 (5.3) | 73 (30.7) | 11 (4.6) | 0.012 | 0.849 | ||

| Nausea | 111 (31.2) | 4 (1.1) | 50 (21.0) | 2 (0.8) | 0.006 | 1.000 | ||

†, P value across all grades, Fisher’s Exact Test; ‡, P value for grades ≥3, Fisher’s Exact Test. ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CTCAEs, Common Terminology Criteria Adverse Events; RE, radioembolization.

Table S4. Summary of significant differences in the reporting of all grades and severe (CTCAE: grade≥3) all-causality adverse events between days 0–90 from first 90Y-RE procedure in patients with at least grade 2 baseline laboratory parameters compared with those with none or only mild changes in baseline laboratory parameters.

| Parameter | System organ, class CTCAE grade | Baseline grade ≥2, n (%) | Baseline grade ≤1, n (%) | P value for all grades† | P value for grade ≥3‡ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All grades | Grade ≥3 | all grades | Grade ≥3 | |||||

| Baseline albumin, grade ≤1 (n=519)grade ≥2 (n=72) | Total patients | 351 (67.6) | 85 (16.4) | 48 (66.7) | 24 (33.3) | 0.894 | 0.001 | |

| Nausea | 148 (28.5) | 6 (1.2) | 11 (15.3) | 0 | 0.016 | 1.000 | ||

| Constitutional | 236 (45.5) | 25 (4.8) | 30 (41.7) | 8 (11.1) | 0.614 | 0.048 | ||

| Hepatobiliary | 56 (10.8) | 24 (4.6) | 22 (30.6) | 10 (13.9) | <0.001 | 0.005 | ||

| Hyperbilirubinemia | 34 (6.6) | 10 (1.9) | 19 (26.4) | 7 (9.7) | <0.001 | 0.002 | ||

| Respiratory | 18 (3.5) | 0 | 3 (4.2) | 2 (2.8) | 0.733 | 0.015 | ||

| Baseline ALP, grade ≤1 (n=493), grade ≥2 (n=99) | Total patients | 329 (66.7) | 84 (17.0) | 70 (70.7) | 24 (24.2) | 0.482 | 0.116 | |

| Peripheral edema | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 2 (2.0) | 2 (2.0) | 0.074 | 0.028 | ||

| Hepatobiliary | 49 (9.9) | 21 (4.3) | 29 (29.3) | 12 (12.1) | <0.001 | 0.006 | ||

| Hyperbilirubinemia | 27 (5.5) | 8 (1.6) | 26 (26.3) | 9 (9.1) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Hepatic failure | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 3 (3.0) | 2 (2.0) | 0.016 | 0.028 | ||

| Baseline hemoglobin, grade ≤1 (n=536), grade ≥2 (n=58) | Total patients | 360 (67.2) | 96 (17.9) | 38 (65.5) | 13 (22.4) | 0.883 | 0.377 | |

| Abdominal distension | 11 (2.1) | 1 (0.2) | 5 (8.6) | 1 (1.7) | 0.014 | 0.186 | ||

| Flatulence | 3 (0.6) | 0 | 3 (5.2) | 0 | 0.014 | NA | ||

| Hyperbilirubinemia | 45 (8.4) | 13 (2.4) | 9 (15.5) | 5 (8.6) | 0.089 | 0.024 | ||

This table reports the highest grade of adverse event reported by each patient within each time interval. †, P value across all grades; ‡, P value for grades ≥3; NA, not applicable; REILD, radioembolization-induced liver disease; ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CTCAEs, Common Terminology Criteria Adverse Events; RE, radioembolization.

Table S5. Median survival after 90Y-RE according to baseline LFT (assessed by CTCAE v3 grade) and extent of prior therapy.

| Parameter | CTCAE grade† | Values | Overall cohort (n=606) | SIRT at 2nd-line (n=206) | SIRT at 3rd-line (n=184) | SIRT at ≥4th-line (n=158) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | Median survival (95% CI) | P value | N (%) | Median survival (95% CI) | P value | N (%) | Median Survival (95% CI) | P value | N (%) | Median Survival (95% CI) | P value | ||||||

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0 | ≤1.3 | 556 (94.0) | 10.4 (9.3–11.9) | <0.001 | 189 (95.0) | 13.2 (10.9–17.2) | <0.001 | 167 (93.0) | 9.1 (7.8–11.2) | 0.937 | 145 (92.0) | 8.7 (6.8–9.5) | <0.001 | |||

| 1 | >1.3–1.95 | 22 (4.0) | 5.1 (2.5–9.0) | 7 (3.0) | 8.5 (0.5–13.1) | 7 (4.0) | 7.4 (1.7–34.8) | 6 (4.0) | 2.7 (1.3–5.1) | ||||||||

| 2 | >1.95–3.9 | 13 (2.0) | 3.8 (1.4–9.9) | 3 (1.5) | 3.2 (1.7–3.8) | 5 (3.0) | 9.9 (1.1–28.4) | 5 (3.0) | 4.1 (0.7–nr) | ||||||||

| 3 | >3.9–13.0 | 1 (0.2) | 0.2 (nr–nr) | 0 | — | 0 | — | 1 (0.6) | 0.2 (nr–nr) | ||||||||

| 4 | >13.0 | 1 (0.2) | 0.7 (nr–nr) | 0 | — | 0 | — | 1 (0.6) | 0.7 (nr–nr) | ||||||||

| Albumin (g/dL) | 0 | ≥3.5 | 392 (66.0) | 13.0 (11.6–13.9) | <0.001 | 133 (67.0) | 16.3 (13.1–18.7) | <0.001 | 126 (71.0) | 10.1 (8.6–12.1) | <0.001 | 94 (59.0) | 9.7 (8.3–13.3) | <0.001 | |||

| 1 | <3.5–3.0 | 127 (21.0) | 7.9 (6.8–9.1) | 45 (23.0) | 9.6 (7.6–16.1) | 35 (20.0) | 7.9 (5.2–11.3) | 41 (26.0) | 6.5 (4.4–8.1) | ||||||||

| 2 | <3.0 – 2.0 | 64 (11.0) | 4.2 (3.6–5.6) | 20 (10.0) | 4.0 (3.0–6.2) | 12 (7.0) | 6.2 (1.4–15.5) | 22 (14.0) | 3.6 (2.3–5.5) | ||||||||

| 3 | <2.0 | 8 (1.0) | 1.5 (0.5–3.0) | 1 (0.5) | 0.5 (nr–nr) | 4 (2.0) | 1.9 (1.1–3.0) | 1 (0.6) | 0.7 (nr–nr) | ||||||||

| ALT (U/L) | 0 | ≤40 | 409 (70.0) | 10.8 (9.0–12.2) | 0.037 | 149 (76) | 13.6 (10.8–17.4) | 0.559 | 120 (67.0) | 9.1 (7.4–11.9) | 0.078 | 94 (61.0) | 7.1 (5.9–9.4) | <0.001 | |||

| 1 | >40–100 | 150 (26.0) | 9.1 (8.2–10.4) | 39 (20.0) | 9.4 (8.1–20.2) | 53 (30.0) | 8.9 (6.1–12.4) | 50 (33.0) | 8.9 (6.5–10.4) | ||||||||

| 2 | >100–200 | 22 (4.0) | 9.5 (4.3–16.3) | 8 (4.0) | 14.7 (2.3–21.4) | 3 (2.0) | 6.5 (1.1–32.4) | 8 (5.0) | 5.0 (1.7–9.5) | ||||||||

| 3 | >200–800 | 2 (0.3) | 5.3 (0.7–9.9) | 0 | — | 1 (0.6) | 9.9 (nr–nr) | 1 (0.7) | 0.7 (nr–nr) | ||||||||

| 4 | >800 | 1 (0.2) | 3.4 (nr–nr) | 0 | — | 1 (0.6) | 3.4 (nr–nr) | 0 | — | ||||||||

| AST (U/L) | 0 | ≤35 | 296 (50.0) | 13.9 (12.2–15.6) | <0.001 | 122 (62.0) | 15.1 (12.2–19.0) | <0.001 | 83 (47) | 11.9 (8.2–15.7) | <0.001 | 62 (40.0) | 13.0 (7.7–15.2) | <0.001 | |||

| 1 | >35–87.5 | 243 (41.0) | 7.9 (6.6–9.0) | 65 (33.0) | 8.5 (6.1–11.1) | 81 (45) | 8.5 (6.5–11.0) | 73 (46.0) | 6.5 (5.1–8.7) | ||||||||

| 2 | >87.5–175 | 42 (7.0) | 4.3 (3.0–9.3) | 8 (4.0) | 15.1 (2.2–21.4) | 10 (6.0) | 3.2 (0.6–5.5) | 20 (13.0) | 4.3 (2.4–7.0) | ||||||||

| 3 | >175–700 | 9 (1.0) | 3.0 (0.2–9.0) | 3 (1.0) | 3.3 (0.9–9.0) | 4 (2.0) | 3.2 (1.1–9.9) | 2 (1.0) | 0.5 (0.2–0.7) | ||||||||

| Alkaline Phospha-tase (U/L) | 0 | ≤126 | 241 (41.0) | 15.7 (13.9–17.7) | <0.001 | 102 (52.0) | 17.4 (13.9–20.0) | <0.001 | 67 (37.0) | 13.9 (9.6–18.6) | <0.001 | 45 (29.0) | 14.0 (9.5–17.7) | <0.001 | |||

| 1 | >126–315 | 252 (43.0) | 8.1 (7.1–9.3) | 71 (36.0) | 9.4 (7.5–12.8) | 86 (48.0) | 7.8 (6.2–9.4) | 73 (46.0) | 7.1 (5.8–9.1) | ||||||||

| 2 | >315–630 | 81 (14.0) | 5.6 (4.5–7.2) | 23 (12.0) | 8.5 (3.3–9.1) | 22 (12.0) | 6.0 (3.0–9.1) | 29 (18.0) | 5.0 (3.9–7.1) | ||||||||

| 3 | >630–2520 | 18 (3.0) | 2.6 (2.0–3.1) | 2 (1.0) | 2.6 (0.9–4.3) | 5 (3.0) | 2.3 (2.0–3.4) | 10 (6.0) | 2.8 (0.7–4.1) | ||||||||

| Creat-inine (mg/dL) | 0 | ≤1.4 | 569 (96.0) | 9.6 (9.0–11.2) | <0.001 | 193 (96.0) | 13.2 (10.6–16.1) | <0.001 | 171 (94.0) | 9.0 (7.8–11.0) | <0.001 | 152 (97.0) | 7.7 (6.4–9.3) | 0.271 | |||

| 1 | >1.4–2.1 | 21 (3.0) | 11.2 (5.4–15.6) | 6 (3.0) | 11.2 (5.7–20.2) | 8 (4.0) | 9.0 (2.9–15.8) | 3 (2.0) | 4.7 (2.0–4.7) | ||||||||

| 2 | >2.1–4.2 | 3 (0.5) | 1.1 (0.8-nr) | 0 | — | 2 (1.0) | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | 1 (58.0) | nr (nr-nr) | ||||||||

| 3 | >4.2–8.4 | 2 (0.3) | 4.4 (1.7–7.1) | 1 (0.5) | 1.7 (nr-nr) | 0 | — | 0 | — | ||||||||

| 4 | >8.4 | 0 | — | 0 | — | 0 | — | 0 | — | ||||||||

| Hemo-globin (g/dL) | 0 | ≥12.0 | 356 (60.0) | 12.2 (10.6–13.6) | <0.001 | 117 (58.0) | 13.9 (10.9–17.4) | 0.117 | 115 (64.0) | 11.0 (8.5–12.3) | <0.001 | 90 (58.0) | 9.5 (8.2–13.1) | <0.001 | |||

| 1 | <12.0–10.0 | 180 (30.0) | 8.1 (6.5–9.7) | 62 (31.0) | 12.2 (8.5–20.2) | 54 (30.0) | 7.9 (6.2–10.4) | 50 (32.0) | 5.3 (3.9–6.5) | ||||||||

| 2 | <10.0–8.0 | 54 (9%) | 6.0 (4.7–8.6) | 20 (10.0) | 8.9 (3.2–13.6) | 10 (6.0) | 4.4 (1.4–6.0) | 15 (10.0) | 4.7 (3.0–6.3) | ||||||||

| 3 | <8.0–6.5 | 4 (1.0) | 6.9 (4.2–13.6) | 2 (1.0) | 6.9 (4.2–9.6) | 1 (0.6) | 13.6 (nr–nr) | 0 | — | ||||||||

RE, radioembolization; ALT, alanine transaminase; CTCAEs, Common Terminology Criteria Adverse Events; LFT, liver function tests.

Ethical Statement: MORE was a retrospective observational study (clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT01815879) of consecutive patients who received RE with yttrium-90 (90Y)-resin microspheres (SIR-Spheres®; Sirtex Medical, Sydney, Australia) at 11 United States (US) institutions, chosen for their experience with RE techniques. An institution review board granted exemptions prior to the collection of data at each site.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: DM Coldwell is a consultant to Sirtex Medical; M Cohn, A Drooz, FM Moeslein, CW Nutting, SG Putnam III, SC Rose, EA Wang are proctors for Sirtex Medical; MA Savin is a speaker for BSD Medical. Prior presentations: AS Kennedy et al. ACRO Annual Meeting 2014.

References

- 1.IARC IAfRoC. GLOBOCAN: estimated incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide in 2012 (population fact sheet in more developed countries). Copyright: IARC, Lyon, France, 2014. Available online: http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/fact_sheets_population.aspx, accessed January 2014.

- 2.NCCN NCCN. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Colon cancer. 2013; Version 2.2014 updates. Available online: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/colon.pdf

- 3.Kopetz S, Chang GJ, Overman MJ, et al. Improved survival in metastatic colorectal cancer is associated with adoption of hepatic resection and improved chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:3677-83. 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.5278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kennedy A, Nag S, Salem R, et al. Recommendations for radioembolization of hepatic malignancies using yttrium-90 microsphere brachytherapy: a consensus panel report from the radioembolization brachytherapy oncology consortium. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2007;68:13-23. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.11.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hendlisz A, Van den Eynde M, Peeters M, et al. Phase III trial comparing protracted intravenous fluorouracil infusion alone or with yttrium-90 resin microspheres radioembolization for liver-limited metastatic colorectal cancer refractory to standard chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:3687-94. 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.5643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Hazel G, Blackwell A, Anderson J, et al. Randomised phase 2 trial of SIR-Spheres plus fluorouracil/leucovorin chemotherapy versus fluorouracil/leucovorin chemotherapy alone in advanced colorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol 2004;88:78-85. 10.1002/jso.20141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruers T, Punt C, Van Coevorden F, et al. Radiofrequency ablation combined with systemic treatment versus systemic treatment alone in patients with non-resectable colorectal liver metastases: a randomized EORTC Intergroup phase II study (EORTC 40004). Ann Oncol 2012;23:2619-26. 10.1093/annonc/mds053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kennedy AS, Ball D, Cohen SJ, et al. Safety and efficacy of resin 90Y-microspheres in 548 patients with colorectal liver metastases progressing on systemic chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:abstr 264.

- 9.Coldwell DM, Sewell PE. The expanding role of interventional radiology in the supportive care of the oncology patient: from diagnosis to therapy. Semin Oncol. 2005;32:169-73. 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2004.11.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salem R, Thurston KG, Carr BI, et al. Yttrium-90 microspheres: radiation therapy for unresectable liver cancer. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2002;13:S223-9. 10.1016/S1051-0443(07)61790-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kennedy AS, Ball D, Cohen SJ, et al. Multicenter evaluation of the safety and efficacy of radioembolization in patients with unresectable colorectal liver metastases selected as candidates for (90)Y resin microspheres. J Gastrointest Oncol 2015;6:134-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Institute NC. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v3.0. Available online: http://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm

- 13.Sanoff HK, Sargent DJ, Campbell ME, et al. Five-year data and prognostic factor analysis of oxaliplatin and irinotecan combinations for advanced colorectal cancer: N9741. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:5721-7. 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.7147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chibaudel B, Bonnetain F, Tournigand C, et al. Simplified prognostic model in patients with oxaliplatin-based or irinotecan-based first-line chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer: a GERCOR study. Oncologist 2011;16:1228-38. 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kemeny N, Braun DW. Prognostic factors in advanced colorectal carcinoma. Importance of lactic dehydrogenase level, performance status, and white blood cell count. Am J Med 1983;74:786-94. 10.1016/0002-9343(83)91066-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chlebowski RT, Silverberg I, Pajak T, et al. Treatment of advanced colon cancer with 5-fluorouracil (NSC19893) versus cyclophosphamide (NSC26271) plus 5-fluorouracil: prognostic aspects of the differential white blood cell count. Cancer 1980;45:2240-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dixon MR, Haukoos JS, Udani SM, et al. Carcinoembryonic antigen and albumin predict survival in patients with advanced colon and rectal cancer. Arch Surg 2003;138:962-6. 10.1001/archsurg.138.9.962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graf W, Bergstrom R, Pahlman L, et al. Appraisal of a model for prediction of prognosis in advanced colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer 1994;30A:453-7. 10.1016/0959-8049(94)90417-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maisano R, Azzarello D, Del Medico P, et al. Alkaline phosphatase levels as a prognostic factor in metastatic colorectal cancer treated with the FOLFOX 4 regimen: a monoinstitutional retrospective study. Tumori 2011;97:39-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graf W, Glimelius B, Pahlman L, et al. Determinants of prognosis in advanced colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer 1991;27:1119-23. 10.1016/0277-5379(91)90307-Y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Köhne CH, Cunningham D, Di Costanzo F, et al. Clinical determinants of survival in patients with 5-fluorouracil-based treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: results of a multivariate analysis of 3825 patients. Ann Oncol 2002;13:308-17. 10.1093/annonc/mdf034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kennedy AS, Nutting C, Coldwell D, et al. Pathologic response and microdosimetry of (90)Y microspheres in man: review of four explanted whole livers. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2004;60:1552-63. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gil-Alzugaray B, Chopitea A, Inarrairaegui M, et al. Prognostic factors and prevention of radioembolization-induced liver disease. Hepatology 2013;57:1078-87. 10.1002/hep.26191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sangro B, Gil-Alzugaray B, Rodriguez J, et al. Liver disease induced by radioembolization of liver tumors: description and possible risk factors. Cancer 2008;112:1538-46. 10.1002/cncr.23339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salem R, Mazzaferro V, Sangro B. Yttrium 90 radioembolization for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: biological lessons, current challenges, and clinical perspectives. Hepatology 2013;58:2188-97. 10.1002/hep.26382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kennedy AS, McNeillie P, Dezarn WA, et al. Treatment parameters and outcome in 680 treatments of internal radiation with resin 90Y-microspheres for unresectable hepatic tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2009;74:1494-500. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oncology Clinical Trials Office, OCTO. Available online: http://wwwocto-oxfordorguk/alltrials/trials/FOXFIRE.ISRCTN83867919, accessed February 2014.

- 28.FOLFOX Plus SIR-SPHERES MICROSPHERES Versus FOLFOX Alone in Patients With Liver Mets From Primary Colorectal Cancer (SIRFLOX). Available online: http://wwwsirfloxcom/home.ClinicalTrials.Gov, accessed February 2014.

- 29.Roswell Park Cancer Institute. (FOXFIRE Global STX0112) Assessment of Overall Survival of FOLFOX6m Plus SIR-Spheres Microspheres Versus FOLFOX6m Alone as First-Line Treatment in Patients with Non-Resectable Liver Metastases from Primary Colorectal Carcinoma in a Randomized Clinical Study. Available online: http://www.sirtex.com/eu/clinicians/mcrc-clinical-studies/foxfirefoxfire-global/, accessed February 2014.

- 30.Walrand S, Lhommel R, Goffette P, et al. Hemoglobin level significantly impacts the tumor cell survival fraction in humans after internal radiotherapy. EJNMMI Res 2012;2:20. 10.1186/2191-219X-2-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee WR, Berkey B, Marcial V, et al. Anemia is associated with decreased survival and increased locoregional failure in patients with locally advanced head and neck carcinoma: a secondary analysis of RTOG 85-27. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1998;42:1069-75. 10.1016/S0360-3016(98)00348-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hong JH, Tsai CS, Chang JT, et al. The prognostic significance of pre- and posttreatment SCC levels in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix treated by radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1998;41:823-30. 10.1016/S0360-3016(98)00147-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kagei K, Shirato H, Nishioka T, et al. High-dose-rate intracavitary irradiation using linear source arrangement for stage II and III squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Radiother Oncol 1998;47:207-13. 10.1016/S0167-8140(97)00229-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fein DA, Lee WR, Hanlon AL, et al. Pretreatment hemoglobin level influences local control and survival of T1-T2 squamous cell carcinomas of the glottic larynx. J Clin Oncol 1995;13:2077-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harrison LB, Chadha M, Hill RJ, et al. Impact of tumor hypoxia and anemia on radiation therapy outcomes. Oncologist 2002;7:492-508. 10.1634/theoncologist.7-6-492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Horsman MR, Overgaard J. The impact of hypoxia and its modification of the outcome of radiotherapy. J Radiat Res 2016;57 Suppl 1:i90-i98. 10.1093/jrr/rrw007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bishop AJ, Allen PK, Klopp AH, et al. Relationship between low hemoglobin levels and outcomes after treatment with radiation or chemoradiation in patients with cervical cancer: has the impact of anemia been overstated? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2015;91:196-205. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.09.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kennedy AS, Ball DS, Cohen SJ, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Radioembolization in Elderly (≥ 70 Years) and Younger Patients With Unresectable Liver-Dominant Colorectal Cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2016;15:141-151.e6. 10.1016/j.clcc.2015.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Read JA, Choy ST, Beale PJ, et al. Evaluation of nutritional and inflammatory status of advanced colorectal cancer patients and its correlation with survival. Nutr Cancer 2006;55:78-85. 10.1207/s15327914nc5501_10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]