Abstract

The epithelium-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is an important process of cell plasticity, consisting in the loss of epithelial identity and the gain of mesenchymal characteristics through the coordinated activity of a highly regulated informational program. Although it was originally described in the embryonic development, an important body of information supports its role in pathology, mainly in cancerous and fibrotic processes. The purinergic system of inter-cellular communication, mainly based in ATP and adenosine acting throughout their specific receptors, has emerged as a potent regulator of the EMT in several pathological entities. In this context, cellular signaling associated to purines is opening the understanding of a new element in the complex regulatory network of this phenotypical differentiation process. In this review, we have summarized recent information about the role of ATP and adenosine in EMT, as a growing field with high therapeutic potential.

Keywords: P2 receptors, P1 receptors, Purinergic signaling, Cell migration, EMT

The purinergic system of intercellular communication

General aspects

The term purine (from: pure urine) was created more than 130 years ago by Emil Fischer after detailed analytical characterization of the uric acid molecule [1]. Purine molecular structure is the result of fusing pyrimidine and imidazole rings, and it exists as four N-H tautomeric forms [2]. Tautomerism of purine bases in DNA is one of the earliest reasons for mutations [3–5]. The interconversion of the different adenine or guanine tautomers produced mispairing with pyrimidines (which also show tautomeric forms) that may lead to changes in DNA sequence [6].

Purine molecules appeared very early in the history of our planet, in the period known as “organic evolution”, before the establishment of living systems. It has been postulated that purines could be formed by a eutectic (denoting a mixture of substances in fixed proportions that melts and freezes at a single temperature that is lower than the melting points of any of the separate constituents) concentration of HCN at extremely low temperature over a period of dozens of years [7]. Purine molecules, such as adenine and guanine, are components of the genetic material (DNA and RNA) of all living beings. Purine and pyrimidine tautomeric equilibria in nucleic acids was postulated to be significant in events such as DNA replication and repair as well as in the occurrence of point mutations [8].

As nucleosides and nucleotides, purines play other highly strategic roles, acting as energy intermediates, allosteric regulators of key metabolic activities, redox molecules, and chemical messengers for signal transduction events. The two most important purines serving as extracellular ligands for paracrine and autocrine signaling are ATP and its dephosphorylated form, adenosine (ADO). ATP and ADO act as intracellular intermediate metabolites, and their presence in the extracellular milieu is needed to promote physiological responses. However, clear differences exist in the manner by which they reach the extracellular space: whereas ATP is released by highly regulated events, ADO appears in the extracellular space when ATP is degraded by phosphate-removing enzymes known as ectonucleotidases [9, 10]. There are many examples of coordinated actions of ATP and adenosine, for example in the neuromuscular synapse, where the ATP released from sympathetic nerves terminal initiates the contractile response of vas deferens smooth muscle cells by a rapid action on P2X7 receptors; ATP is cleared by the action of ectonucleotidases and the formed adenosine, acting on presynaptic P1 receptors inhibits the ATP release giving as a final result the modulation of synaptic activity [11].

ATP release

ATP acting as a cellular messenger can be released by hypotonic stress-induced cell swelling, direct deformation of the surface membrane, fluid shear stress, and membrane-cytoskeletal rearrangements associated with G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) [12]. Two main pathways are responsible for this regulated release of ATP: exocytotic and conductive (for review, see [13]). The first mechanism involves 1) Golgi-derived secretory vesicles mobilized by constitutive exocytotic pathways utilized by protein secretion, and 2) specialized secretory granules that actively accumulate ATP which is released during Ca2+-dependent regulated exocytosis. In addition, intracellular ATP can also transit to the external medium via ATP-permeable channels. So far, 4 types of channels have been involved in ATP efflux: 1) hexamers of hemi-channels of various connexin-family subunits, 2) hexameric assemblies of pannexin protein subunits, 3) volume-regulated anion channels (VRAC), and 4) maxi-anion channels. Although ATP is present within cells at mM concentrations, dynamic intracellular gradients of ATP have been reported in several cellular systems [14]; however, no reports exist regarding the control of ATP released from defined subcellular domains.

ADO formation from ATP role of ecto-nucleotidases

As a chemical ligand, ATP is able to exert a set of diverse actions by acting through its G protein-coupled receptors and receptor-channels. In contrast to other cellular communication systems, ATP hydrolysis yields an alternative purine (ADO) that is recognized by a completely different set of receptors. ADO often has effects antagonistic to those of ATP, providing an elegant mechanism of homeostatic regulation [15]. The conversion of ATP to ADO is carried out by a set of extracellular hydrolytic enzymes generically called ecto-nucleotidases. These include members of the E-NTPDase (ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase) family and the E-NPP (ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase) family. Ecto-5´-nucleotidase (ecto-5´-NT) and alkaline phosphatase (AP) also catalyze the degradation of ATP to ADO (for review, see [16, 17]).

Purinoceptors

Two families of purinergic receptors known as P1 and P2 (for ADO and ATP/ADP, respectively) were postulated almost 40 years ago (in 1978); however, it has been proposed the existence of another subfamily of receptors activated by the nucleobase adenine named P0 receptors [18].

Based on pharmacological studies and later supported by molecular characterization, 2 types of P2 receptors (P2X and P2Y) were recognized. P2X receptors are trimeric, ligand-gated ion channels; whereas P2Y receptors are 7 trans-membrane spanning G-protein coupled proteins (for recent reviews, see [19–21]). So far, 7 P2X subunits (P2X1–7) and 8 P2Y receptor subtypes (P2Y1, P2Y2, P2Y4, P2Y6, P2Y11, P2Y12, P2Y13, and P2Y14) have been identified, including receptors whose ligands are pyrimidines and purines [22]. Four types of P1 ADO receptors (ADORA) (see [23]) have been cloned: ADORA1, ADORA2A, ADORA2B, and ADORA3. ADORA receptors are members of the rhodopsin-like family of G protein-coupled receptors. ADORA1 and ADORA3 negatively regulate adenylyl cyclase, reducing cAMP synthesis by acting through the Gi/o protein subunits. ADORA1 is also linked to various kinase pathways such as protein kinase C (PKC), phosphoinositide 3 (PI3) kinase and the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases. In addition, ADORA1 activation can directly activate K+ channels and inhibit Q-, P- and N-type Ca2+ channels [24]. The proposed P0 receptors are also GPCR, the first one was cloned in 2002 from rat tissue [25], recently has been cloned from, mouse and guinea pig [26, 27], P0 receptor are mainly coupled to Gi protein and in consequence to the inhibition of adenylate cyclase [18, 25, 26], and are expressed in lung, ovaries, kidneys, and nervous system [25].

Growing evidence highlights the physiological and pathological impact of purinergic system as a paracrine messenger, contributing to understanding the importance of chemical signaling in the extracellular environment. Two notable examples let us to appraise the impact of purinergic “paracrinome”, understood as the nucleotide availability, diversity receptor expression and ectonucleotidase activity in the cellular function. First, the role of ATP as damage-associated molecule patterns (DAMPs), in which the accumulation of the nucleotide in the extracellular space triggers the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, contributing with the establishment of the pathological state, for example in the genesis of chronic liver disease [28, 29]; and second, the positive feedback loop present in the tumor interstitium by accumulation of the high concentrations of ATP and adenosine, that contributes with tumor progression [30]. From both situations is clear that the fine tuning of the nucleotide species and its concentration in the extracellular space is fundamental for the homeostatic state. In the following sections of this review we will show that extracellular nucleotides also regulate cell differentiation and the implications of this regulation are decisive for the cellular function.

The epithelium to mesenchymal transition

What is EMT? EMT is an important process of cellular transdifferentiation consisting in the change from an epithelial to a migratory mesenchymal phenotype. This process is an example of the great plasticity displayed by embryonic and well-differentiated tissues, and it has been shown to be of capital relevance in morphogenesis, tissue repair, and pathological conditions such as fibrosis and cancer [31–33].

Initially, the process was described as the “epithelium to mesenchymal transformation” (EMT), a term coined in the late 60’s by Elizabeth Hay, who described the cellular events during the remodeling of embryonic tissues [34]. Importantly, the EMT is the principal mechanism of early morphogenic events. It is an important process in the formation of the mesoderm from the primitive ectoderm, named the epiblast, at the beginning of gastrulation, which is a mechanism conserved from invertebrates to mammals [35]. EMT is a reversible phenomenon since the mesenchymal to epithelium (MET) process is also observed in normal physiology. For example, it occurs during the development of the nephron epithelium during kidney morphogenesis [36].

Greenburg and Hay observed EMT in well-differentiated epithelia in 1982 [37]. They described how epithelial tissues cultured in collagen gels lost polarity, became dissociated and acquired migratory abilities, becoming phenotypically indistinguishable from mesenchymal cells. This groundbreaking observation opened a new paradigm in the study of cellular plasticity with important implications for our understanding of tissue dynamics in physiological and pathological conditions.

Epithelia are highly organized structures where specialized cells located over a basal membrane (BM) display a baso-apical polarity, and under normal conditions they are kept in situ since they are unable to cross the BM. Because epithelia form the boundaries delimiting tissues and organs, they have a key role in regulating tissue permeability; thus, epithelial cells are strongly, but at the same time, finely coupled with their neighbors through specialized protein complexes such as adherens junctions, desmosomes, and tight junctions [38, 39].

On the other hand, cells with the mesenchymal phenotype do not show direct coupling between neighboring cells, and they acquire the ability to migrate by means of specialized structures such as the intermediate filaments formed by vimentin. Mesenchymal cells change the type of adhesion molecules and express high levels of N-cadherin. It is well known that when cancerous cells undergo EMT, they become metastatic by acquiring the ability to cross the BM and transit throughout the extracellular matrix (ECM). Cancerous cells that show motility usually express high levels of metalloproteinases [31].

It has been proposed that EMT occurs in 3 different modalities: 1) the one associated with morphogenesis, which is an EMT without invasive properties; 2) the EMT that occurs in fibrogenesis as well as in the wound-healing process; 3) the EMT that occurs in cancer cells and gives these cells a metastatic phenotype [32, 40].

Regulation of EMT

An important molecule whose expression is down-regulated in the EMT process is E-cadherin. Loss of E-cadherin is implicated in the disappearance of α- and β-catenins from the cellular junctions, concomitant with the loss of the epithelial phenotype [41]. Thus, they are not only structural proteins, but they are also signaling elements supporting the epithelial identity.

EMT is triggered by a variety of signaling molecules. The most important inducer of EMT is the cytokine transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), acting through its transducers, the SMAD proteins [42]. Most of the factors that promote EMT (i.e., epidermal growth factor (EGF), fibroblast growth factor (FGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), hepatic growth factor (HGF), vascular and endothelial growth factor VEGF) act through specific receptors that show intrinsic tyrosine-kinase activity (RTK) [43–47].

The Wnt/β-catenin pathway is another important inducer of EMT. Upon activation by specific ligands, β-catenin is released from the membrane and promotes transcription of genes involved in mesenchymal phenotype induction [48]. Notch and Hedgehog, acting as morphogens, are also able to activate EMT by regulating the expression of Snail [49, 50].

Another group of molecules with the ability to induce EMT in physiological and pathological conditions are the metalloproteinases (MMP) (reviewed in [51]). The role of MMPs as EMT inducers has been described in kidney, lung, ovary, oral, and mammary epithelium [52–57]. Their mechanism of action involves the processing and activation of pro-TGF-β in the ECM, as well as the direct proteolysis of E-cadherin [53, 55, 57].

Although these molecules activate diverse signaling pathways, they converge to regulate the activity of specific transcription factors. It is well recognized that transcriptional control of cdh-1, the gene coding for E-cadherin, is exerted by the following zinc-finger transcriptional repressors: SNAI1 (Snail) and SNAI2 [46, 58], ZEB1 and ZEB2 [59, 60], TCF3 and TCF4 [61], and TWIST proteins [62]. The best known factor regulating EMT is Snail; hence, great effort has been focused on describing the signaling and transduction pathways that regulate its activity. It has been reported that Snail regulates the cdh-1 locus when it is associated with SIN3A, HDAC1, and HDAC2 [63].

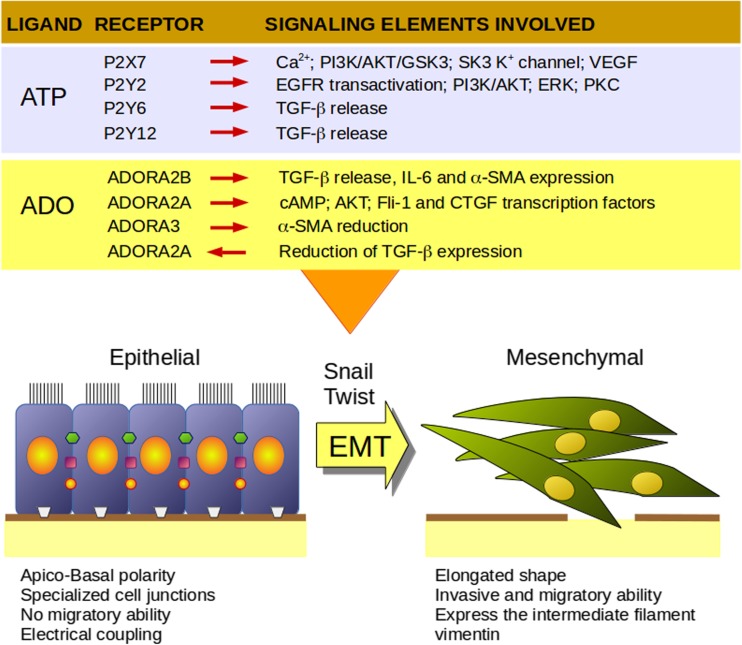

It is clear that induction of EMT is a highly regulated cellular program, whose execution results from a balance of multiple signals; although abundant information is known about the mechanisms involved, many aspects are remain unknown. Recent studies show a role for purines in the mechanisms of EMT regulation (Fig. 1); thus, the machinery of the purinergic system represents an emerging finely tuned modulator to be considered in the intricate web of signals modulating EMT.

Fig. 1.

Main characteristics of epithelial and mesenchymal phenotypes and their modulation by purinergic receptors. PI3K, Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; AKT, protein kinase B; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; EGFR, epithelial growth factor receptor; ERK, p42/p44 mitogen-activated protein kinases; PKC, protein kinase C; TGF-β, transforming growth factor beta; IL-6, interleukin 6; α-SMA, alpha smooth muscle actin; cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate; Fli-1, ETS transcription factor; CTGF, connective tissue growth factor. Based in the references 64–71 for P2X7, 78–83 for P2Y2, 93–95 for P2Y6, 92 for P2Y12, 128 for ADORA2B, 129–131 and 135 for ADORA 2A and 132 for ADORA3

Purinergic signaling, EMT and invasiveness

In cancer, EMT is mainly related to metastasis of tumoral cells and generation of stem-like cancerous cells and, consequently, to promoting resistance to chemotherapy. Metastasis is the process of cancer cell dissemination from a primary tumor to a different organ to form a secondary tumor. This event occurs mainly through intravasation of lymphatic and blood vessels, although some cancer cells are also able to spread through interstitial tissues under the basal lamina or directly into the peritoneal cavity (e.g., ovarian carcinoma). The metastatic process involves a succession of cellular events comprising tumor angiogenesis, acquisition of an invasive phenotype by primary tumor cells, intravasation of cancer cells into blood and lymphatic vessels, attachment to a target organ, and establishment of a secondary tumor [72–75]. In this complex succession of events, the phenotypical change of tumor cells to acquire invasive abilities is absolutely necessary. It is in this context that EMT takes on great importance, since it is the principal cellular mechanism of metastatic transformation.

Early observations have shown that maintenance of the epithelial phenotype is highly dependent on the presence of cell adhesion proteins, mainly E-cadherin, and that altering these junction proteins is enough to switch an epithelial phenotype to a mesenchymal phenotype [76–79]. Furthermore, an analysis of E-cadherin expression in various carcinoma cell lines from bladder, breast, lung, and pancreas showed an inverse correlation with invasiveness, and this correlation was associated with a mesenchymal phenotype [80]. Concomitantly with the loss of adherens molecules, other proteins that are also markers of the mesenchymal phenotype have been reported in cells engaged in EMT; for example, the presence of vimentin, a type III intermediate filament protein, is related to the increased invasive capacity of breast carcinoma cells [81].

An significant body of literature supports a role for purinergic signaling in cancer (for reviews, see [82, 83]); some of the most important findings are as follows: 1) the P2X7 receptor is overexpressed in several carcinomas [83], 2) the tumoral microenvironment shows high levels of extracellular ATP [84], and 3) a variety of ectonucleotidases are present and their activity forms ADO from ATP and other adenine nucleotides; indeed, ADO has been shown to be important in cancer [85]. Recently, the role of purinergic signaling was analyzed at the onset and during regulation of EMT in transformed cells, with an emphasis on its invasive properties (Table 1).

Table 1.

Modulation of EMT by purinergic signaling elements

| Receptor, enzyme or transporter | Model | Effect | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| P2Y | Prostate cancer cells PC-3 | ATP increased invasive properties suggesting a role for one purinergic receptor. | [86] |

| P2Y2 | Prostate cancer PC-3 | ATP through P2RY2 receptor increased Snail and IL-8 transcription followed by a decreased E-cadherin and claudin expression. | [87] |

| P2Y2 | Prostate cancer cells, 1E8 and 2B4 | P2RY2 transactivated EGFR and induced ERK 1/2 activity and IL-8 upregulation. Also increased migration and induced EMT. | [88] |

| P2Y2 | Ovarian cancer cells, SKOV-3 | Incubation with UTP increased EMT and migration; P2RY2 knockdown reduced the effect. EGFR transactivation and ERK1/2 activity are needed for EMT and migration. | [89] |

| P2Y2 | Breast cancer cells, MDA-MB-231 | P2RY2 increases invasiveness and downregulation of epithelial markers, the mechanism involves PKC signaling. | [90] |

| P2X7 | Prostate cancer cells, 1E8 and 2B4 | Agonists for P2RX7 increase EMT inducers such as Snail and mesenchymal markers. Genetic and pharmacological tools that inhibit P2RX7 block the effect; participation of ERK and AKT signaling. | [64] |

| P2X7 | Breast cancer cells, T47D | Increment in invasiveness and effect on EMT markers expression (E-cadherin and MMP-13) through AKT pathway. | [66] |

| P2Y12 | B16 melanoma cells and Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) cells in a murine metastasis model | P2RY12 −/− mice showed less cancer cell invasivity, and their platelets secreted less TGF-β than those from wild-type mice, suggesting a role for the P2RY12 receptor in inducing TGF-β-mediated EMT in cancer cells, favoring metastasis. | [91] |

| P2Y6 | Breast cancer cells, MDA-MB-468 | P2RY6 was over-expressed after hypoxia and EGF-induced EMT, P2RY6 knockdown and pharmacological treatment reduced mesenchymal markers and migration. | [92] |

| NT5E | Gallbladder cancer cells, GBC-SD | TGF-β favored a mesenchymal phenotype and increased expression of the NT5E enzyme. | [93] |

| NT5E | Ovarian tumors | Expression of NT5E in stromal tumor cells with markers of EMT, suggested role of ectonucleotidases in the invasion process. | [94] |

| Human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 (hENT1), | Renal fibrosis | Protective role against TGF-β- induced fibrosis and EMT. Lack of hENT1 increased fibrosis and EMT as well as CD73 expression. | [95] |

| ADORA2B | Renal fibrosis, NRK49F | Adenosine upon ADORA2B receptor mediates an increment on SMA-α, IL-6, TGF-β. | [96] |

| ADORA2A | Dermal fibrosis | ADORA2A antagonism promotes reduction on collagen content and expression of pro-fibrotic factors in ADA-deficient mice. | [97] |

| ADORA3 | Renal fibrosis | Antagonism of ADORA3 receptor protected against in vivo- or in vitro-induced fibrosis, increased E-cadherin expression, and reduced α-SMA. | [98] |

| ADORA2A | Renal fibrosis | Agonist of ADORA2A receptor protects against EMT induction and renal fibrosis development. | [99] |

Purinergic signaling it has been related with the induction of EMT. For instance, in two prostate cancer (PC) cell lines derived from PC-3 cells, stimulation of one type of P2Y receptor with ATP induced an increase in their migratory and invasive abilities, an action mediated by the activation of kinases ERK and p38 [86]. Eventually, P2Y2 was identified as one of the receptors responsible for the ATP-induced invasive response of the PC cells; the process involved the activation of the EMT program, since expression of the transcripts coding for Snail and IL-8 increased whereas those for E-cadherin and claudin decreased [87]. Further analysis of the molecular mechanism showed that P2Y2 receptor activation during EMT was associated with EGFR activity. Both signaling systems converge to activate ERK with the concomitant induction of IL-8 [88], a hallmark of prostate carcinoma invasiveness [100].

Consistent with these data, a regulatory action of the P2Y2 receptor on EMT and cell migration was also described in the ovarian carcinoma-derived cell line SKOV-3. In this system, stimulation of the P2Y2 receptor with UTP favored the expression of Snail and Twist transcripts, and it induced an increase in the vimentin level. In addition, an increase in cell migration was shown to be associated with EGFR transactivation and the subsequent phosphorylation of ERK1/2. Interestingly, treatment with apyrase, an ectonucleotidase that cleaves ATP to ADP and AMP, reduced basal migration and favored the epithelial phenotype. This action promoted a relocation of E-cadherin to cellular junctions, strongly suggesting that dephosphorylated metabolites of ATP participate in the control of EMT induction [89]. The increment in invasiveness, together with the downregulation of epithelial markers and the expression of mesenchymal markers mediated by the P2Y2 receptor, was also demonstrated in a highly metastatic breast cancer cellular line named MDA-MB-231, through a pathway mediated by PKC activity [90].

In PC, besides P2Y2 receptor, the P2X7 receptor also plays a synergistic role in the induction of EMT and cell invasivity by activating the ERK1/2 and PI3K/AKT pathways [64]. It was demonstrated that P2X7 receptor activation enhances invasiveness through a mechanism involving Ca2+-activated SK3 K+-channel activity in the mammary carcinoma cell line MDA-MB-435 s [65]. In addition, P2X7 receptor activation in T47D breast cancer cells induces an increase in cell invasiveness associated with the expression of EMT markers, such as E-cadherin and MMP-13, via the AKT pathway [66].

In agreement with that, some important studies have demonstrated that P2X7 receptor activation is able to regulate pathways directly involved in EMT program switching. Tumors induced by the implant of HEK-293 cells heterologously expressing P2X7 receptors in immunodeficient mice showed elevated growth rate, an anaplastic phenotype, and high production of VEGF a well-known EMT inductor [67]. In cell lines derived from neuroblastoma or ovarian carcinoma, P2X7 receptor activity is correlated with high tumoral growth and metastatic induction, effects that involve PI3K/AKT pathway activity [67–70]. Moreover, in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cell lines, P2X7 receptor activity regulates migration and invasion, responses associated with EMT induction [71].

A recent study used knockout mice to examine the role of P2Y12 receptor expressed in platelets during pulmonary metastasis. It demonstrated that a finely tuned coordination between platelets and cancerous cells eventually modulates tumor cell invasiveness through EMT induction. The paracrine loop involved AMP released from cancerous cells, which was the agonist for the platelet P2Y12 receptor to promote TGF-β release; this cytokine, in turn, induced EMT in lung cancer cells, thus allowing metastasis [91].

ATP elicited a reduced Ca2+ response during EMT in MDA-MB-468 breast carcinoma cells under hypoxic conditions; this response correlated with a lower expression of P2X4, P2X5, P2X7, P2Y1, and P2Y11 purinergic receptors, and an elevated expression of P2Y6 [92]. P2Y6 receptor overexpression has been associated with EMT induced by growth factors and hypoxia; accordingly, the pharmacological inhibition or genetic silencing of this receptor prevented the induction of EMT and the increase in cellular migration [92, 101]. The role of UDP in the tumor microenvironment activating the P2Y6 receptor and the concomitant metastatic transformation were also shown in breast cancer cell lines MDA-MB-231, Hs578t, BT-549, and MCF-7; these responses were characterized by the expression of MMP-9 and the activation of MAPK and Nf-κB [101]. These observations supported the idea that high expression of the P2Y6 receptor mediated EMT induction and correlated with the high invasivity of breast cancer tumors. In agreement with the in vitro evidence, patients with tumors showing high P2Y6 receptor expression have a poor prognosis [92, 101]. Importantly, it was shown that UDP is released in response to chemotherapy, highlighting a putative mechanism for drug resistance [101]. This observation is relevant from a translational perspective and it suggests that the P2Y6 receptor is a potential pharmacological target in breast cancer; moreover, it emphasizes the role played by released nucleotides (ATP and UTP) during radiochemotherapy as strong pro-metastatic factors [102].

As previously mentioned, TGF-β is one of the most powerful inducers of EMT; for example, in a gallbladder carcinoma cell line it promotes a mesenchymal phenotype with a notorious increase in the expression of ectonucleotidase CD73, the enzyme that dephosphorylates AMP to adenosine, suggesting that the nucleoside could be fundamental in the EMT induction program activated by TGF-β in this cell line [93]. However, CD73 has been part of a polemic argument regarding its involvement in the cancerous process. CD73 expression in ovarian carcinoma or medulloblastoma some studies was associated with a good prognosis [103, 104], while in others it was associated with a poor prognosis [94]. Interestingly, Turcotte et al. observed CD73 expression mainly in stromal cells with an EMT gene signature, and they proposed that ectonucleotidase is involved in tumor invasion [94]. In recent studies, it was described that tumor-derived exosomes containing ectonucleotidases CD39 and CD73 are able to transfer an EMT program with a pro-metastatic message; the ADO produced by these enzymes exerts a negative modulation of the antitumor immune response facilitating the metastasis process [105] and reviewed in [106].

On the other hand, a tumor is a heterogeneous entity in which not all cells have the ability to start new cancerous growth because only a small, specific cellular population, known as cancer stem cells (CSC), has that capability [107]. It has been shown that CSC and cells undergoing EMT belong to a common population (reviewed in [33]), and CSC isolated from mammary cancer are able to form spheroids and display EMT markers. In this context, expression of transcription factors, such as Slug and Sox9, was demonstrated both in CSC and during EMT [108, 109]. Purines, through P2X7 receptors, contribute to the maintenance of stemness in embryonic stem cells [110], and they regulate the proliferation rate of cancer stem cells and endothelial progenitors [111]. Further studies are needed to confirm and extend purinergic regulation in CSC biology.

Numerous genomic studies have recently characterized EMT induction in detail. The molecular signature of EMT is a good predictor of chemo-resistance and neoplastic disease lethality [112–116]; thus, EMT gene expression signature predicts chemo-resistance to EGFR and PI3K inhibitors in non-small cell lung-carcinoma (NSCLC) cells [113]. It has also been proposed that the ongoing EMT signature predicts the systemic recurrence of tumoral development in breast cancer [117]. It will be interesting to explore, in the context of this experimental approach, a possible participation of purinergic signaling elements in the molecular characteristics of cancerous processes.

Purinergic signaling, EMT and fibrosis

Fibrosis is a pathological state similar to an aberrant scarring process; it is characterized by the abnormal accumulation of extracellular matrix (ECM) components as a consequence of a chronic inflammatory response [118, 119]. It is well known that myofibroblast (MFB) is the main cell type with the capacity to synthesize collagen in the fibrotic state [119, 120]. The origin of these collagen-forming cells is not always clear, but it has classically been accepted that they derive from tissue-resident fibroblasts; recent evidence suggests that other cell populations (i.e., organ epithelial cells) are also able to generate MFB during EMT induction. Moreover, it is clear that type 2 EMT of epithelial cells from organs undergoing fibrosis results in the ability to produce ECM components [121, 122]. For example, MFB in the liver mainly originates from the activation of hepatic stellate cells (HSC) [119]; however, adult hepatocytes that undergo EMT induced by TGF-β can also contribute to the MFB population [123–125]. It has been demonstrated that the hepatocyte-derived myofibroblast subpopulation is positive for fibroblast-specific protein 1 (FSP-1), whereas MFB derived from HSC are positive for α-smooth muscle actin [123]. Likewise, bile-duct epithelial cells can contribute to the MFB population, since these cells express EMT markers associated with bile duct ligation and bile duct atresia in humans [123, 126].

Similarly, it has been shown that resident renal epithelial cells undergo partial EMT that contributes to the interstitial fibrosis phenotype in kidney fibrosis [127, 128]. This phenomenon has also been described in cardiac fibrosis [129]. A variety of observations highlight the importance of EMT as an underlying cellular mechanism of fibrosis, which generates new opportunities to gain a mechanistic understanding of this pathological condition.

There are several reports that show a regulatory role for purinergic receptors in the fibrotic process of different organs (reviewed in [130]), but less has been said about the EMT mechanism in this pathological process. ADO signaling has a role in renal fibrosis; particularly the human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 (hENT1) was reported to play a protective role in maintaining the epithelial phenotype; since blocking hENT1 with dipyridamole induced EMT in proximal tubular cells (PTC) generating myofibroblasts and favoring a fibrotic process. hENT1 knockdown in the HK-2 renal cell line induced the expression of markers of the mesenchymal phenotypic markers. These observations imply that extracellular accumulation of ADO, triggered by a blocking or silencing of the hENT1 expression, acts as an inducer of EMT and, eventually, of fibrosis [95].

Interestingly, the expression of CD73, the ectonucleotidase that catalyzes ADO formation, increased with TGF-β, the most potent inductor of EMT thus indicating ADO participation in EMT induction [95]. In this context, it was shown that there is a reduced expression of hENT1 during the TGF-β-induced EMT of the human umbilical vein endothelium; this reduction supports the notion that hENT1 is an essential target of TGF-β in activation of the EMT program [131].

The described observations are consistent with previous evidence demonstrating a pro-fibrotic role for ADO; for example, ADO induces the increment of transcripts for pro-fibrotic, inflammatory and EMT mediators, including TGF-β, IL-6 and α-SMA, through the activation of ADORA2B in renal cell line NRK49F [96]. Furthermore, ADORA2A stimulation in dermal fibroblasts induces an augment in the abundance of collagen 1 and 3 proteins, and its blockade prevents pharmacologically-induced dermal fibrosis [97]; it has been described that this effect is mediated by the cAMP accumulation elicited by ADORA2A activity and by a subsequent AKT activation, but it is independent of the TGF-β/SMAD pathway [132]. Downstream, ADORA2A stimulation regulates the activity of Fli-1 and CTGF transcription factors to modulate the expression level of collagen I gene [133].

Certainly the balance between extracellular and intracellular ADO is a key evidence in EMT and fibrotic process regulation. It has been reported that some receptor-mediated mechanisms could explain the pro-fibrotic role of ADO; for instance, LJ-1888, an antagonist of the ADORA3 receptor, prevented the induction of fibrosis by either unilateral urethral obstruction (UUO) or TGF-β administration (in vivo and in vitro, respectively). Treatment with LJ-1888 reduced the accumulation of α-SMA (mRNA and protein) and increased the transcription of E-cadherin, again emphasizing the role of ADO in the induction of EMT and in the onset of fibrosis. LJ-1888 was also effective in reducing and reversing tubule-interstitial fibrosis in an obstructed kidney model in mice [98].

On the other hand, there are observations which show that ADO has a protective role in liver fibrosis, since the systemic administration of the nucleoside protects against the CCl4-induced fibrosis [134, 135]. In this context, renal fibrosis (RF) induced by UUO exacerbated the expression of EMT induction markers and fibrosis indicators in knockout mice; accordingly, ADORA2A activation with the agonist CGS21680 reduced EMT and the onset of renal fibrosis in wild-type littermates with the UUO model. ADORA2A activity increased its own expression and E-cadherin levels, and it conversely reduced α-SMA expression, collagen deposition, and TGF-β expression, which demonstrates the role of this receptor in protection against tissue failure [99].

Overall, ADO signaling should be considered a potential therapeutic target in fibrotic conditions through the modulation of either the ADORA2A or ADORA3 receptors, or by the activities of the hENT1 transporter and the CD73 ectonucleotidase.

Concluding remarks

This review highlights the role that purinergic signaling plays in the onset and development of EMT. ATP and ADO are now well-recognized modulators in cancerous processes involved in metastatic spreading and fibrosis induction. This information opens a window of opportunity to gain a better understanding of the EMT phenomenon and to design potential therapeutic approaches to control diseases.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Dorothy Pless and LCC. Jessica González Norris for editing the manuscript. This work was funded by Programa de Apoyo a Proyectos de Investigación e Innovación Tecnológica (PAPIIT-UNAM-México), number IN205114 and IN200815 to FGV-C and MD-M. ASM-R is student of Programa de Doctorado en Ciencias Biomédicas-UNAM, México and received a fellowship (number 369701) from CONACyT-México.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest

Angélica S. Martínez-Ramírez declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Mauricio Díaz Muñoz declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Armando Butanda-Ochoa declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Francisco G. Vázquez-Cuevas declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Oestreich-Janzen S (2016) Caffeine: characterization and properties, in Encyclopedia of Food and Health. In: Caballero, B, Finglas, PM and Toldrá F (Eds). Elsevier – Academic Press, pp 556–572.

- 2.Stasyuk O, Szatylowicz H, Krygowski TM. Effect of the H-bonding on aromaticity of purine of tautomers. J Org Chem. 2012;77:4035–4045. doi: 10.1021/jo300406r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sugar D, Kierdaszuk B. Proc Int Symp Biomol Struct interactions, Suppl. J Biosci. 1985;8:657. doi: 10.1007/BF02702764. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morgan AR. Base mismatches and mutagenesis: how important is tautomerism? Trends Biochem Sci. 1993;18:160–163. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(93)90104-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brovarets OO, Hovorun DM. Does the G·G*syn syn DNA mismatch containing canonical and rare tautomers of the guanine tautomerise through the DPT? A QM/QTAIM microstructural study. Mol Phys. 2014;112:3033–3046. doi: 10.1080/00268976.2014.927079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kushwaha PS, Kumar A, Mishra PC. Electronic transitions of guanine tautomers, their stacked dimers, trimers and sodium complexes. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2004;60:719–728. doi: 10.1016/S1386-1425(03)00283-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miyakawa S, Cleaves HJ, Miller SL. The cold origen of life: B. Implications based on pyrimidines and purines produced from frozen ammonium cyanide solutions. Origins of life and evolution of the biosphere. Kluwer academic publishers. The Netherlands. 2002;32:209–218. doi: 10.1023/a:1019514022822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brovarets O, Zhurakivsky R, Hovorun DM. ¿is the DPT tautomerization of the long A-G Watson-crick DNA base mispair a source of the adenine and guanine mutagenic tautomers?. A QM and QTAMIR response to the biologically important question. J Comput Chem. 2014;35:451–466. doi: 10.1002/jcc.23515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hardie DG. Sensing of energy and nutrients by AMP-activated protein kinase. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:891–896. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.001925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Volonté C, D’Ambrosi N. Membrane compartments and purinergic signaling: the purinome, a complex interplay among ligands, degrading enzymes, receptors and transporters. FEBS J. 2009;276:318–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Westfall DP, Todorov LD, Mihaylova-Todorova ST. ATP as a cotransmitter in sympathethic nerves and its inactivation by releasable enzymes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;303:439–444. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.035113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dubyak GR. Maxi-anion channel and pannexin 1 hemichannel constitute separate pathways for swelling-induced ATP release in murine L929 fibrosarcoma cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;303:C913–C915. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00285.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lazarowski ER. Vesicular and conductive mechanisms of nucleotide release. Purinergic Signal. 2012;8:359–373. doi: 10.1007/s11302-012-9304-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Imamura H, Nhat KP, Togawa H, Saito K, Lino R, Kato-Yamada Y, Nagai T, Noji H. Vizualization of ATP levels inside single living cells with fluorescence resonance energy transfer-based genetically encoded indicators. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:15651–15656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904764106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fields RD, Burnstock G. Purinergic signaling in neuron-glia interactions. Nature Rev Neurosc. 2006;7:423–436. doi: 10.1038/nrn1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zimmermann H, Zebisch M, Sträter N. Cellular function and molecular structure of ecto-nucleotidases. Purinergic Sig. 2012;8:437–502. doi: 10.1007/s11302-012-9309-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Massé K, Bhamra S, Allsop G, Dale N, Jones EA. Ectophosphodiesterase/nucleotide phosphohydrolase (Enpp) nucleotidases: cloning, conservation and developmental restriction. Int J Dev Biol. 2010;54:181–193. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.092879km. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brunschweiger A, Muller CE. P2 receptors activated by uracil nucleotides an update. Curr Med Chem. 2006;13:289–312. doi: 10.2174/092986706775476052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.North RA (2016) P2X receptors. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Ser B Biol Sci 371(1700) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Habermacher C, Dunning K, Chataigneau T, Grutter T. Molecular structure and function of P2X receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2016;104:18–30. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.von Kügelgen I, Hoffmann K. Pharmacology and structure of P2Y receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2016;104:50–61. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burnstock G. Purine and pyrimidine receptors. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:1471–1483. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-6497-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacobson KA, Müller CE. Medicinal chemistry of adenosine, P2Y and P2X receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2016;104:31–49. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Della Latta V, Cabiati M, Rocchiccioli S, Del Ry S, Morales MA. The role of adenosinergic system in lung fibrosis. Pharmacol Res. 2013;76:182–189. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bender E, Buist A, Jurzak M, Langlois X, Baggerman G, Verhasselt P, Ercken M, Guo HQ, Wintmolders C, Van den Wyngaert I, Van Oers I, Schoofs L, Luyten W. Characterization of an orphan G protein-coupled receptor localized in the dorsal root ganglia reveals adenine as a signaling molecule. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:8573–8578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122016499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.von Kügelgen I, Schiedel AC, Hoffmann K, Alsdorf BB, Abdelrahman A, Müller CE. Cloning and functional expression of a novel Gi protein-coupled receptor for adenine from mouse brain. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73:469–477. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.037069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thimm D, Knospe M, Abdelrahman A, Moutinho M, Alsdorf BB, von Kügelgen I, Schiedel AC, Müller CE. Characterization of new G protein-coupled adenine receptors in mouse and hamster. Purinergic Signal. 2013;9:415–426. doi: 10.1007/s11302-013-9360-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Szabo G, Petrasek J. Inflammasome activation and function in liver disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12:387–400. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petrasek J, Iracheta-Vellve A, Saha B, Satishchandran A, Kodys K, Fitzgerald KA, Kurt-Jones EA, Szabo G. Metabolic danger signals, uric acid and ATP, mediate inflammatory cross-talk between hepatocytes and immune cells in alcoholic liver disease. J Leukoc Biol. 2015;98:249–256. doi: 10.1189/jlb.3AB1214-590R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Di Virgilio F, Adinolfi E (2016) Extracellular purines, purinergic receptors and tumor growth. Oncogene doi:10.1038/onc.2016.206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Thiery JP. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:442–454. doi: 10.1038/nrc822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zeisberg M, Neilson EG. Biomarkers for epithelial-mesenchymal transitions. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1429–1437. doi: 10.1172/JCI36183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ye X, Weinberg RA. Epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity: a central regulator of cancer progression. Trends Cell Biol. 2015;25:675–686. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hay ED. The mesenchymal cell, its role in the embryo, and the remarkable signaling mechanisms that create it. Dev Dyn. 2005;233:706–720. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Viebahn C. Epithelio-mesenchymal transformation during formation of the mesoderm in the mammalian embryo. Acta Anat (Basel) 1995;154:79–97. doi: 10.1159/000147753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davies JA. Mesenchyme to epithelium transition during development of the mammalian kidney tubule. Acta Anat (Basel) 1996;156:187–201. doi: 10.1159/000147846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Greenburg G, Hay ED. Epithelia suspended in collagen gels can lose polarity and express characteristics of migrating mesenchymal cells. J Cell Biol. 1982;95:333–339. doi: 10.1083/jcb.95.1.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hirohashi S. Inactivation of the E-cadherin-mediated cell adhesion system in human cancers. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:333–339. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65575-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Macara IG, Guyer R, Richardson G, Huo Y, Ahmed SM. Epithelial homeostasis. Curr Biol. 2014;24:R815–R825. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.06.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kalluri R, Weinberg RA. The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1420–1428. doi: 10.1172/JCI39104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cano A, Pérez-Moreno MA, Rodrigo I, Locascio A, Blanco MJ, del Barrio MG, Portillo F, Nieto MA. The transcription factor snail controls epithelial-mesenchymal transitions by repressing E-cadherin expression. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:76–83. doi: 10.1038/35000025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miettinen PJ, Ebner R, Lopez AR, Derynck R. TGF-beta induced transdifferentiation of mammary epithelial cells to mesenchymal cells: involvement of type I receptors. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:2021–2036. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.6.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pagan R, Martín I, Llobera M, Vilaró S. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition of cultured rat neonatal hepatocytes is differentially regulated in response to epidermal growth factor and dimethyl sulfoxide. Hepatology. 1997;25:598–606. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Savagner P, Vallés AM, Jouanneau J, Yamada KM, Thiery JP. Alternative splicing in fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 is associated with induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in rat bladder carcinoma cells. Mol Biol Cell. 1994;5:851–862. doi: 10.1091/mbc.5.8.851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kong D, Wang Z, Sarkar SH, Li Y, Banerjee S, Saliganan A, Kim HR, Cher ML, Sarkar FH. Platelet-derived growth factor-D overexpression contributes to epithelial-mesenchymal transition of PC3 prostate cancer cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26:1425–1435. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Savagner P, Yamada KM, Thiery JP. The zinc-finger protein slug causes desmosome dissociation, an initial and necessary step for growth factor-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:1403–1419. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.6.1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang AD, Camp ER, Fan F, Shen L, Gray MJ, Liu W, Somcio R, Bauer TW, Wu Y, Hicklin DJ, Ellis LM. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 activation mediates epithelial to mesenchymal transition in human pancreatic carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:46–51. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim K, Lu Z, Hay ED. Direct evidence for a role of beta-catenin/LEF-1 signaling pathway in induction of EMT. Cell Biol Int. 2002;26:463–476. doi: 10.1006/cbir.2002.0901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Timmerman LA, Grego-Bessa J, Raya A, Bertrán E, Pérez-Pomares JM, Díez J, Aranda S, Palomo S, McCormick F, Izpisúa-Belmonte JC, de la Pompa JL. Notch promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition during cardiac development and oncogenic transformation. Genes Dev. 2004;18:99–115. doi: 10.1101/gad.276304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Omenetti A, Porrello A, Jung Y, Yang L, Popov Y, Choi SS, Witek RP, Alpini G, Venter J, Vandongen HM, Syn WK, Baroni GS, Benedetti A, Schuppan D, Diehl AM. Hedgehog signaling regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition during biliary fibrosis in rodents and humans. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3331–3342. doi: 10.1172/JCI35875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Radisky ES, Radisky DC. Matrix metalloproteinase-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in breast cancer. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2010;15:201–212. doi: 10.1007/s10911-010-9177-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cheng S, Lovett DH. Gelatinase a (MMP-2) is necessary and sufficient for renal tubular cell epithelial-mesenchymal transformation. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:1937–1949. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64327-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zheng G, Lyons JG, Tan TK. Disruption of E-cadherin by matrix metalloproteinase directly mediates epithelial-mesenchymal transition downstream of transforming growth factor-beta1 in renal tubular epithelial cells. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:580–591. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Illman SA, Lehti K, Keski-Oja J. Epilysin (MMP-28) induces TGF-beta mediated epithelial to mesenchymal transition in lung carcinoma cells. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:3856–3866. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cowden Dahl KD, Symowicz J, Ning Y. Matrix metalloproteinase 9 is a mediator of epidermal growth factor dependent E-cadherin loss in ovarian carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4606–4613. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang SH, Law CH, Kuo PH, Hu RY, Yang CC, Chung TW, Li JM, Lin LH, Liu YC, Liao EC, Tsai YT, Wei YS, Lin CC, Chang CW, Chou HC, Wang WC, Chang MD, Wang LH, Kung HJ, Chan HL, Lyu PC. MMP-13 is involved in oral cancer cell metastasis. Oncotarget. 2016 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 57.Lochter A, Galosy S, Muschler J, Freedman N, Werb Z, Bissell MJ. Matrixmetalloproteinase stromelysin-1 triggers a cascade of molecular alterations that leads to stable epithelial-to-mesenchymal conversion and a premalignant phenotype in mammary epithelial cells. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:1861–1872. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.7.1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Batlle E, Sancho E, Francí C, Domínguez D, Monfar M, Baulida J, García De Herreros A. The transcription factor snail is a repressor of E-cadherin gene expression in epithelial tumour cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:84–89. doi: 10.1038/35000034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Comijn J, Berx G, Vermassen P, Verschueren K, van Grunsven L, Bruyneel E, Mareel M, Huylebroeck D, van Roy F. The two-handed E box binding zinc finger protein SIP1 downregulates E-cadherin and induces invasion. Mol Cell. 2001;7:1267–1278. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00260-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Eger A, Aigner K, Sonderegger S, Dampier B, Oehler S, Schreiber M, Berx G, Cano A, Beug H, Foisner R. DeltaEF1 is a transcriptional repressor of E-cadherin and regulates epithelial plasticity in breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2005;24:2375–2385. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Perez-Moreno MA, Locascio A, Rodrigo I, Dhondt G, Portillo F, Nieto MA, Cano A. A new role for E12/E47 in the repression of E-cadherin expression and epithelial-mesenchymal transitions. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:27424–27431. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100827200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang J, Mani SA, Donaher JL, Ramaswamy S, Itzykson RA, Come C, Savagner P, Gitelman I, Richardson A, Weinberg RA. Twist, a master regulator of morphogenesis, plays an essential role in tumor metastasis. Cell. 2004;117:927–939. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Peinado H, Ballestar E, Esteller M, Cano A. Snail mediates E-cadherin repression by the recruitment of the Sin3A/histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1)/HDAC2 complex. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:306–319. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.1.306-319.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Qiu Y, Li WH, Zhang HQ, Liu Y, Tian XX, Fang WG. P2X7 mediates ATP-driven invasiveness in prostate cancer cells. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jelassi B, Chantome A, Alcaraz-Pérez F, Baroja-Mazo A, Cayuela ML, Pelegrin P, Surprenant A, Roger S. P2X(7) receptor activation enhances SK3 channels- and cystein cathepsin-dependent cancer cells invasiveness. Oncogene. 2011;30:2108–2122. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xia J, Yu X, Tang L, Li G, He T. P2X7 receptor stimulates breast cancer cell invasion and migration via the AKT pathway. Oncol Rep. 2015;34:103–110. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.3979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Adinolfi E, Raffaghello L, Giuliani AL, Cavazzini L, Capece M, Chiozzi P, Bianchi G, Kroemer G, Pistoia V, Di Virgilio F. Expression of P2X7 receptor increases in vivo tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2012;72(12):2957–2969. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Amoroso F, Capece M, Rotondo A, Cangelosi D, Ferracin M, Franceschini A, Raffaghello L, Pistoia V, Varesio L, Adinolfi E. The P2X7 receptor is a key modulator of the PI3K/GSK3β/VEGF signaling network: evidence in experimental neuroblastoma. Oncogene. 2015;34(41):5240–5251. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gómez-Villafuertes R, García-Huerta P, Díaz-Hernández JI, Miras-Portugal MT. PI3K/Akt signaling pathway triggers P2X7 receptor expression as a pro-survival factor of neuroblastoma cells under limiting growth conditions. Sci Rep. 2015;5:18417. doi: 10.1038/srep18417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vázquez-Cuevas FG, Martínez-Ramírez AS, Robles-Martínez L, Garay E, García-Carrancá A, Pérez-Montiel D, Castañeda-García C, Arellano RO. Paracrine stimulation of P2X7 receptor by ATP activates a proliferative pathway in ovarian carcinoma cells. J Cell Biochem. 2014;115:1955–1966. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Giannuzzo A, Pedersen SF, Novak I. The P2X7 receptor regulates cell survival, migration and invasion of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells. Mol Cancer. 2015;14:203. doi: 10.1186/s12943-015-0472-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liotta LA, Stetler-Stevenson WG. Tumor invasion and metastasis: an imbalance of positive and negative regulation. Cancer Res. 1991;51:5054s–5059s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang W, Wyckoff JB, Frohlich VC, Oleynikov Y, Hüttelmaier S, Zavadil J, Cermak L, Bottinger EP, Singer RH, White JG, Segall JE, Condeelis JS. Single cell behavior in metastatic primary mammary tumors correlated with gene expression patterns revealed by molecular profiling. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6278–6288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Eccles SA, Welch DR. Metastasis: recent discoveries and novel treatment strategies. Lancet. 2007;369:1742–1757. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60781-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Guan X. Cancer metastases: challenges and opportunities. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2015;5:402–418. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Imhof BA, Vollmers HP, Goodman SL, Birchmeier W. Cell-cell interaction and polarity of epithelial cells: specific perturbation using a monoclonal antibody. Cell. 1983;35:667–675. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vestweber D, Kemler R, Ekblom P. Cell-adhesion molecule uvomorulin during kidney development. Dev Biol. 1985;112:213–221. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(85)90135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Behrens J, Mareel MM, Van Roy FM, Birchmeier W. Dissecting tumor cell invasion: epithelial cells acquire invasive properties after the loss of uvomorulin-mediated cell-cell adhesion. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:2435–2447. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.6.2435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gooding JM, Yap KL, Ikura M. The cadherin-catenin complex as a focal point of cell adhesion and signalling: new insights from three-dimensional structures. BioEssays. 2004;26:497–511. doi: 10.1002/bies.20033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Frixen UH, Behrens J, Sachs M, Eberle G, Voss B, Warda A, Löchner D, Birchmeier W. E-cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion prevents invasiveness of human carcinoma cells. J Cell Biol. 1991;113:173–185. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.1.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Thompson EW, Paik S, Brünner N, Sommers CL, Zugmaier G, Clarke R, Shima TB, Torri J, Donahue S, Lippman ME, Martin GR, Dickson RB. Association of increased basement membrane invasiveness with absence of estrogen receptor and expression of vimentin in human breast cancer cell lines. J Cell Physiol. 1992;150:534–544. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041500314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Burnstock G, Di Virgilio F. Purinergic signaling and cancer. Purinergic Signal. 2013;9:491–540. doi: 10.1007/s11302-013-9372-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Di Virgilio F. Purines, purinergic receptors and cancer. Cancer Res. 2012;72:5441–5447. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pellegatti P, Raffaghello L, Bianchi G, Piccardi F, Pistoia V, Di Virgilio F. Increased level of extracellular ATP at tumor sites: in vivo imaging with plasma membrane luciferase. PLoS One. 2008;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gao ZW, Dong K, Zhang HZ. The roles of CD73 in cancer. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:460654. doi: 10.1155/2014/460654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chen L, He HY, Li HM, Zheng J, Heng WJ, You JF, Fang WG. ERK1/2 and p38 pathways are required for P2Y receptor-mediated prostate cancer invasion. Cancer Lett. 2004;215:239–247. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Li WH, Qiu Y, Zhang HQ, Liu Y, You JF, Tian XX, Fang WG. P2Y2 receptor promotes cell invasion and metastasis in prostate cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:1666–1675. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Li WH, Qiu Y, Zhang HQ, Tian XX, Fang WG. P2Y2 receptor and EGFR cooperate to promote prostate cancer cell invasion via ERK1/2 pathway. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Martínez-Ramírez AS, Garay E, García-Carrancá A, Vázquez-Cuevas FG. The P2RY2 receptor induces carcinoma cell migration and EMT through cross-talk with epidermal growth factor receptor. J Cell Biochem. 2016;117:1016–1026. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Eun SY, Ko YS, Park SW, Chang KC, Kim HJ. P2Y2 nucleotide receptor-mediated extracellular signal-regulated kinases and protein kinase C activation induces the invasion of highly metastatic breast cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2015;34(1):195–202. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.3972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wang Y, Sun Y, Li D, Zhang L, Wang K, Zuo Y, Gartner TK, Liu J. Platelet P2Y12 is involved in murine pulmonary metastasis. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Azimi I, Beilby H, Davis FM, Marcial DL, Kenny PA, Thompson EW, Roberts-Thompson S, Monteith G. Altered purinergic receptor-Ca2+ signaling associated with hypoxia-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in breast cancer cells. Mol Oncol. 2016;10:166–178. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Xiong L, Wen Y, Miao X, Yang Z. NT5E and FcGBP as key regulators of TGF-1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) are associated with tumor progression and survival of patients with gallbladder cancer. Cell Tissue Res. 2014;355:365–374. doi: 10.1007/s00441-013-1752-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Turcotte M, Spring K, Pommey S, Chouinard G, Cousineau I, George J, Chen GM, Gendoo DM, Haibe-Kains B, Karn T, Rahimi K, Le Page C, Provencher D, Mes-Masson AM, Stagg J. CD73 is associated with poor prognosis in high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2015;75:4494–4503. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Guillén-Gómez E, Pinilla-Macua I, Pérez-Torras S, Choi DS, Arce Y, Ballarin JA, Pastor-Anglada M, Díaz-Encarnación M. New role of the human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 (hENT1) in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in renal tubular cells. J Cell Physiol. 2012;227:1521–1528. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wilkinson PF, Farrell FX, Morel D, Law W, Murphy S. Adenosine signaling increases proinflammatory and profibrotic mediators through activation of a functional adenosine 2B receptor in renal fibroblasts. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2016;46(4):339–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Fernández P, Trzaska S, Wilder T, Chiriboga L, Blackburn MR, Cronstein BN, Chan ES. Pharmacological blockade of A2A receptors prevents dermal fibrosis in a model of elevated tissue adenosine. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:1675–1682. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lee J, Hwang I, Lee JH, Lee HW, Jeong LS, Ha H. The selective A3AR antagonist LJ-1888 ameliorates UUO-induced tubulointerstitial fibrosis. Am J Phatol. 2013;183:1488–1497. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Xiao H, Shen HY, Liu W, Xiong RP, Li P, Meng G, Yang N, Chen X, Si LY, Zhou YG. Adenosine A2A receptor: a target for regulating renal interstitial fibrosis in obstructive nephropathy. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Inoue K, Slaton JW, Eve BY, Kim SJ, Perotte P, Balbay MD, Yano S, Bar-Eli M, Radinsky R, Pettaway CA, Dinney CP. Interleukin 8 expression regulates tumorigenicity and metastases in androgen-independent prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:2104–2119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ma X, Pan X, Wei Y, Tan B, Yang L, Ren H, Qian M, Du B. Chemotherapy-induced uridine diphosphate release promotes breast cancer metastasis through P2Y6 activation. Oncotarget. 2016 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Schneider G, Glaser T, Lameu C, Abdelbaset-Ismail A, Sellers ZP, Moniuszko M, Ulrich H, Ratajczak MZ. Extracellular nucleotides as novel, underappreciated pro-metastatic factors that stimulate purinergic signaling in human lung cancer cells. Mol Cancer. 2015;14:201. doi: 10.1186/s12943-015-0469-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Oh HK, Sin JI, Choi J, Park SH, Lee TS, Choi YS. Overexpression of CD73 in epithelial ovarian carcinoma is associated with better prognosis, lower stage, better differentiation and lower regulatory T cell infiltration. J Gynecol Oncol. 2012;23:274–281. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2012.23.4.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cappellari AR, Pillat MM, Souza HD, Dietrich F, Oliveira FH, Figueiró F, Abujamra AL, Roesler R, Lecka J, Sévigny J, Battastini AM, Ulrich H. Ecto-5′ nucleotidase overexpression reduces tumor growth in a Xenograph medulloblastoma model. PLoS One. 2015;10(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Clayton A, Al-Taei S, Webber J, Mason MD, Tabi Z. Cancer exosomes express CD39 and CD73, which suppress T cells through adenosine production. J Immunol. 2011;187:676–683. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Syn N, Wang L, Sethi G, Thiery JP, Goh BC. Exosome-mediated metastasis: from epithelial-mesenchymal transition to escape from Immunosurveillance. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2016;37:606–617. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lapidot T, Sirard C, Vormoor J, Murdoch B, Hoang T, Caceres-Cortes J, Minden M, Paterson B, Caligiuri MA, Dick JE. A cell initiating human acute myeloid leukaemia after transplantation into SCID mice. Nature. 1994;367:645–648. doi: 10.1038/367645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Guo W, Keckesova Z, Donaher JL, Shibue T, Tischler V, Reinhardt F, Itzkovitz S, Noske A, Zürrer-Härdi U, Bell G, Tam WL, Mani SA, van Oudenaarden A, Weinberg RA. Slug and Sox9 cooperatively determine the mammary stem cell state. Cell. 2012;148:1015–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Fan F, Samuel S, Evans KW, Lu J, Xia L, Zhou Y, Sceusi E, Tozzi F, Ye XC, Mani SA, Ellis LM. Overexpression of snail induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition and a cancer stem cell-like phenotype in human colorectal cancer cells. Cancer Med. 2012;1:5–16. doi: 10.1002/cam4.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Glaser T, de Oliveira SL, Cheffer A, Beco R, Martins P, Fornazari M, Lameu C, Junior HM, Coutinho-Silva R, Ulrich H. Modulation of mouse embryonic stem cell proliferation and neural differentiation by the P2X7 receptor. PLoS One. 2014;9(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.D’Alimonte I, Nargi E, Zuccarini M, Lanuti P, Di Iorio P, Giuliani P, Ricci-Vitiani L, Pallini R, Caciagli F, Ciccarelli R. Potentiation of temozolomide antitumor effect by purine receptor ligands able to restrain the in vitro growth of human glioblastoma stem cells. Purinergic Signal. 2015;11:331–346. doi: 10.1007/s11302-015-9454-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Loboda A, Nebozhyn MV, Watters JW, Buser CA, Shaw PM, Huang PS, Van’t Veer L, Tollenaar RA, Jackson DB, Agrawal D, Dai H, Yeatman TJ. EMT is the dominant program in human colon cancer. BMC Med Genet. 2011;20:9. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-4-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Byers LA, Diao L, Wang J, Saintigny P, Girard L, Peyton M, Shen L, Fan Y, Giri U, Tumula PK, Nilsson MB, Gudikote J, Tran H, Cardnell RJ, Bearss DJ, Warner SL, Foulks JM, Kanner SB, Gandhi V, Krett N, Rosen ST, Kim ES, Herbst RS, Blumenschein GR, Lee JJ, Lippman SM, Ang KK, Mills GB, Hong WK, Weinstein JN, Wistuba II, Coombes KR, Minna JD, Heymach JV. An epithelial-mesenchymal transition gene signature predicts resistance to EGFR and PI3K inhibitors and identifies Axl as a therapeutic target for overcoming EGFR inhibitor resistance. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:279–290. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Huang RY, Kuay KT, Tan TZ, Asad M, Tang HM, Ng AH, Ye J, Chung VY, Thiery JP. Functional relevance of a six mesenchymal gene signature in epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) reversal by the triple angiokinase inhibitor, nintedanib (BIBF1120) Oncotarget. 2015;6:22098–22113. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Shukla P, Vogl C, Wallner B, Rigler D, Müller M, Macho-Maschler S. High-throughput mRNA and miRNA profiling of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in MDCK cells. BMC Genomics. 2015;216:944. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-2036-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Roudi R, Madjd Z, Ebrahimi M, Najafi A, Korourian A, Shariftabrizi A, Samadikuchaksaraei A. Evidence for embryonic stem-like signature and epithelial-mesenchymal transition features in the spheroid cells derived from lung adenocarcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s13277-016-5041-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Cheng Q, Chang JT, Gwin WR, Zhu J, Ambs S, Geradts J, Lyerly HK. A signature of epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity and stromal activation in primary tumor modulates late recurrence in breast cancer independent of disease subtype. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16:407. doi: 10.1186/s13058-014-0407-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lee YA, Wallace MC, Friedman SL. Pathobiology of liver fibrosis: a translational success story. Gut. 2015;64:830–841. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-306842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Friedman SL. Hepatic stellate cells: protean, multifunctional, and enigmatic cells of the liver. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:125–172. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Stempien-Otero A, Kim DH, Davis J. Molecular networks underlying myofibroblast fate and fibrosis. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2016;97:153–161. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Nakamura M, Tokura Y. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in the skin. J Dermatol Sci. 2011;61:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Carew RM, Wang B, Kantharidis P. The role of EMT in renal fibrosis. Cell Tissue Res. 2012;347:103–116. doi: 10.1007/s00441-011-1227-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Zeisberg M, Yang C, Martino M, Duncan MB, Rieder F, Tanjore H, Kalluri R. Fibroblasts derive from hepatocytes in liver fibrosis via epithelial to mesenchymal transition. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:23337–23347. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700194200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Meindl-Beinker NM, Dooley S. Transforming growth factor-beta and hepatocyte transdifferentiation in liver fibrogenesis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol Suppl. 2008;1:S122–S127. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Kaimori A, Potter J, Kaimori JY, Wang C, Mezey E, Koteish A. Transforming growth factor-beta1 induces an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition state in mouse hepatocytes in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:22089–22101. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700998200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Xiao Y, Zhou Y, Chen Y, Zhou K, Wen J, Wang Y, Wang J, Cai W. The expression of epithelial-mesenchymal transition-related proteins in biliary epithelial cells is associated with liver fibrosis in biliary atresia. Pediatr Res. 2015;77:310–315. doi: 10.1038/pr.2014.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Lovisa S, LeBleu VS, Tampe B, Sugimoto H, Vadnagara K, Carstens JL, Wu CC, Hagos Y, Burckhardt BC, Pentcheva-Hoang T, Nischal H, Allison JP, Zeisberg M, Kalluri R. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition induces cell cycle arrest and parenchymal damage in renal fibrosis. Nat Med. 2015;21:998–1009. doi: 10.1038/nm.3902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Zhao Y, Qiao X, Wang L, Tan TK, Zhao H, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Rao P, Cao Q, Wang Y, Wang Y, Wang YM, Lee VW, Alexander SI, Harris DC, Zheng G. Matrix metalloproteinase 9 induces endothelial-mesenchymal transition via notch activation in human kidney glomerular endothelial cells. BMC Cell Biol. 2016;17:21. doi: 10.1186/s12860-016-0101-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Zeisberg EM, Tarnavski O, Zeisberg M, Dorfman AL, McMullen JR, Gustafsson E, Chandraker A, Yuan X, Pu WT, Roberts AB, Neilson EG, Sayegh MH, Izumo S, Kalluri R. Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition contributes to cardiac fibrosis. Nat Med. 2007;13:952–961. doi: 10.1038/nm1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Lu D, Insel PA. Cellular mechanisms of tissue fibrosis. 6. Purinergic signaling and response in fibroblasts and tissue fibrosis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2014;306:C779–C788. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00381.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Vega JL, Puebla C, Vásquez R, Farías M, Alarcón J, Pastor-Anglada M, Krause B, Casanello P, Sobrevia L. TGF-beta1 inhibits expression and activity of hENT1 in a nitric oxide-dependent manner in human umbilical vein endothelium. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;82:458–467. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Perez-Aso M, Fernandez P, Mediero A, Chan ES, Cronstein BN. Adenosine 2A receptor promotes collagen production by human fibroblasts via pathways involving cyclic AMP and AKT but independent of Smad2/3. FASEB J. 2014;28:802–812. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-241646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Chan ES, Liu H, Fernandez P, Luna A, Perez-Aso M, Bujor AM, Trojanowska M, Cronstein BN. Adenosine a(2A) receptors promote collagen production by a Fli1 and CTGF-mediated mechanism. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15:R58. doi: 10.1186/ar4229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Pérez-Carreón JI, Martínez-Pérez L, Loredo ML, Yañez-Maldonado L, Velasco-Loyden G, Vidrio-Gómez S, Ramírez-Salcedo J, Hernández-Luis F, Velázquez-Martínez I, Suárez-Cuenca JA, Hernández-Muñoz R, de Sánchez VC. An adenosine derivative compound, IFC305, reverses fibrosis and alters gene expression in a pre-established CCl(4)-induced rat cirrhosis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42(2):287–296. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Velasco-Loyden G, Pérez-Carreón JI, Agüero JF, Romero PC, Vidrio-Gómez S, Martínez-Pérez L, Yáñez-Maldonado L, Hernández-Muñoz R, Macías-Silva M, de Sánchez VC. Prevention of in vitro hepatic stellate cells activation by the adenosine derivative compound IFC305. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;80:1690–1699. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]