Abstract

Despite acting as a barrier for the organs they encase, epithelial cells turnover at some of the fastest rates in the body. Yet, epithelial cell division must be tightly linked to cell death to preserve barrier function and prevent tumour formation. How do the number of dying cells match those dividing to maintain constant numbers? We previously found that when epithelial cells become too crowded, they activate the stretch-activated channel Piezo1 to trigger extrusion of cells that later die1. Conversely, what controls epithelial cell division to balance cell death at steady state? Here, we find that cell division occurs in regions of low cell density, where epithelial cells are stretched. By experimentally stretching epithelia, we find that mechanical stretch itself rapidly stimulates cell division through activation of the same Piezo1 channel. To do so, stretch triggers cells paused in early G2 to activate calcium-dependent ERK1/2 phosphorylation that activates cyclin B transcription necessary to drive cells into mitosis. Although both epithelial cell division and cell extrusion require Piezo1 at steady state, the type of mechanical force controls the outcome: stretch induces cell division whereas crowding induces extrusion. How Piezo1-dependent calcium transients activate two opposing processes may depend on where and how Piezo1 is activated since it accumulates in different subcellular sites with increasing cell density. In sparse epithelial regions where cells divide, Piezo1 localizes to the plasma membrane and cytoplasm whereas in dense regions where cells extrude, it forms large cytoplasmic aggregates. Because Piezo1 senses both mechanical crowding and stretch, it may act as a homeostatic sensor to control epithelial cell numbers, triggering extrusion/apoptosis in crowded regions and cell division in sparse regions.

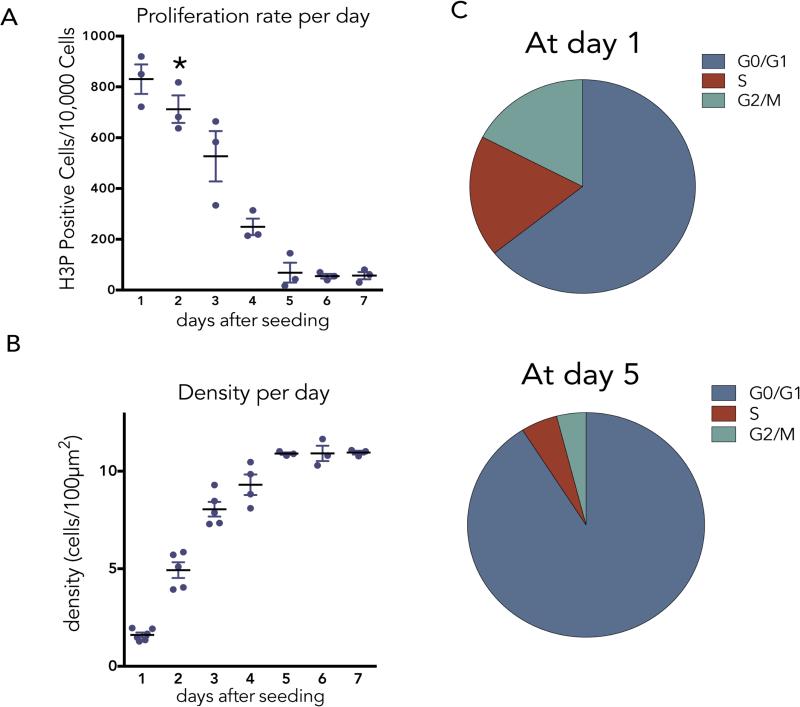

To investigate what controls epithelial cell division at steady state, we seeded Madin Darby Canine Kidney (MDCK) epithelial cells and measured the percentage of mitotic cells daily by immunostaining cells for phospho-histone H3 (H3P) (ED Fig. 1A&B). While epithelial cells never stop dividing, the rates of cell division reach a slow steady state by ~day 5, at an average density of 11 cells/1000 μm2, three days after reaching confluence (asterisk). The ~7% mitotic rate at seeding slows to ~0.7% at steady state when most cells are in the G0/G1 stage of the cell cycle (ED Fig. 1A-C and Supplementary Videos 1&2).

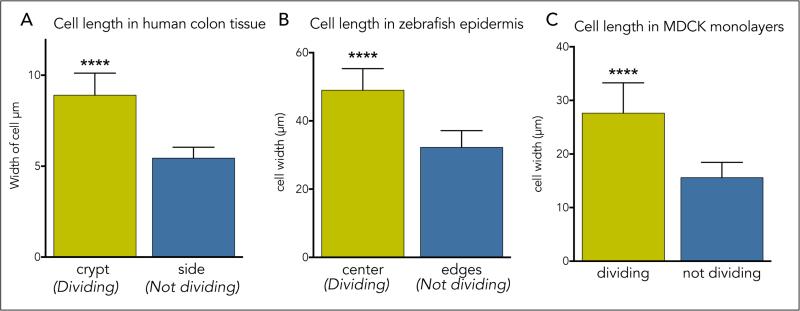

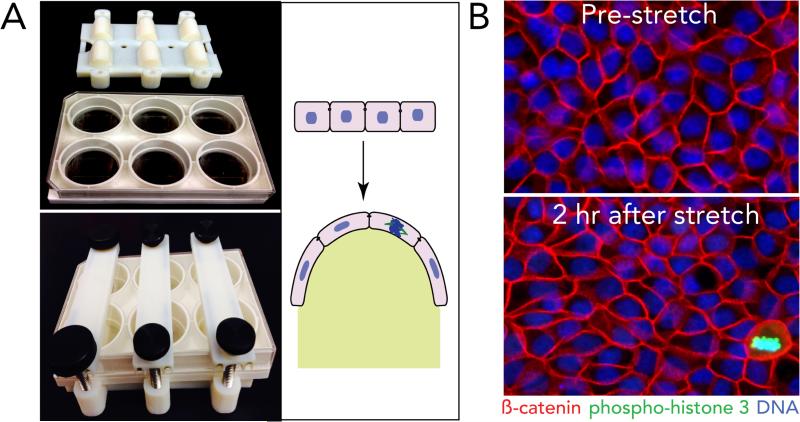

How do epithelial cells regulate cell division once they reach an optimal density? While the overall cell division rates decrease as the monolayer reaches steady state, videos reveal that cells divide in sparse sub-regions of the epithelium (Supplementary Video 2). Additionally, cell division occurs in zones that are consistently ~1.6-fold less dense than zones where no division occurs, as quantified by cell lengths in dividing versus non-dividing regions in human colon crypts (1.6), zebrafish epidermis (1.5), and MDCK monolayers (1.7) (Supplementary Videos 2&3 and ED Fig. 2). These observations made us wonder if cell stretch due to low cell density could activate epithelial cell division. To test this hypothesis, we experimentally stretched MDCK cells at steady state by either wounding or directly uni-axially stretching cells and analysed mitotic rates at different times following stretch. Experimentally stretching cells ~1.4-fold using a previously published device1 or a newly designed stretch device (ED Fig. 3A), was sufficient to induce a ~5-fold increase in cell division within only one hour (ED Fig. 3B and Fig. 1A). While the increased proliferation rate was low (1.3%), it returned cells to homeostatic densities, as measured by averaged cell lengths, within four hours (Fig. 1B). Additionally, scratching an MDCK monolayer stretched cells ~2.5-fold their original length once cell migration ceased and triggered a wave of cell division (Fig. 1C&D and Supplementary Video 4; n=6) and seen previously2. Cell division typically occurred within one-two hours of wound closure, similar to the kinetics following stretch.

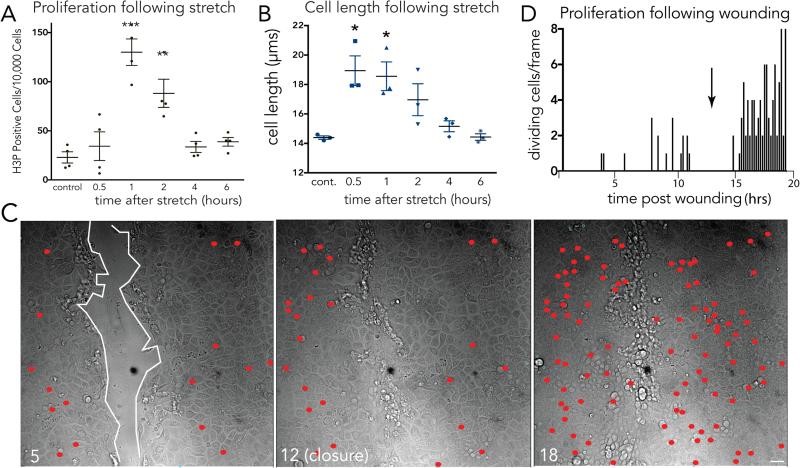

Figure 1. Mechanical stretch induces epithelial monolayers to rapidly divide.

(A) Proliferation rates (A) and cell lengths (B) at various times following stretch show that stretch-induced cell divisions return cell densities to control levels, where values are the averages of 3 experiments measuring the mean of 6 areas, error bars = s.e.m. P-values from unpaired T-tests compared to control are ***<0.0005, **<0.005, *<0.01. (C) Stills showing cumulatively where and when cells divide (red dots) during wound healing of an MDCK monolayer, where wound edge (highlighted with white line) with time in hours. (D) Graph (one of 14 similar) of cell divisions after monolayer wounding, with arrow indicating wound closure.

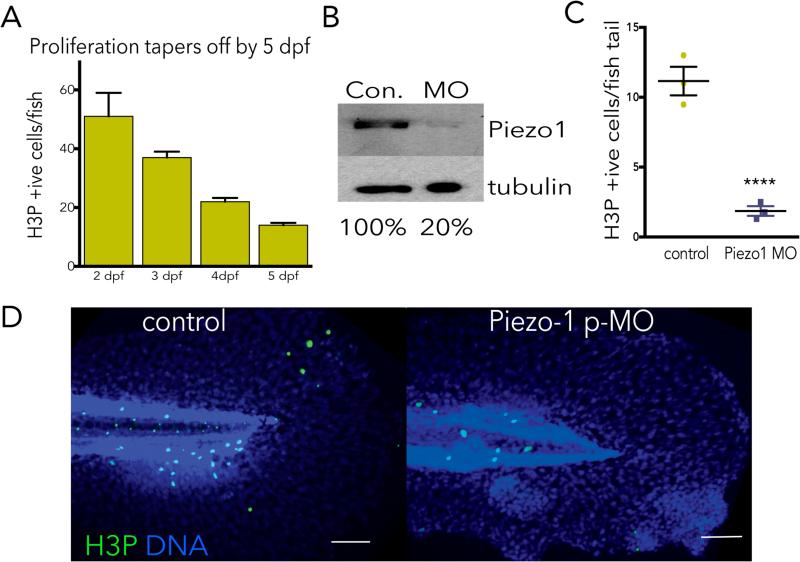

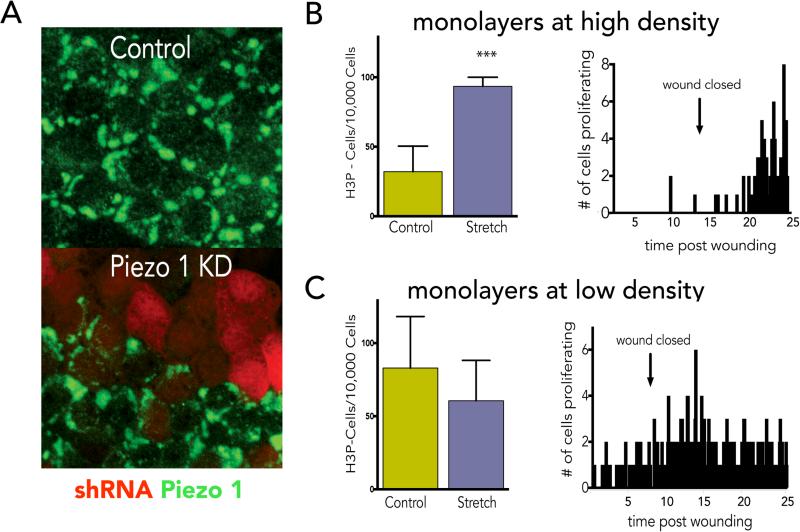

To determine what regulates stretch-induced mitosis, we inhibited a variety of candidate proteins implicated in cellular stress or stretch responses. Gadolinium, a generic stretch-activated channel inhibitor, consistently blocked stretch-induced proliferation, where the CDK1 inhibitor roscovitine served as a generic inhibitor of mitosis (Fig. 2A). Because Piezo1 is a stretch-activated channel required for crowding-induced, extrusion-dependent epithelial cell death1,3, we tested if it might also control stretch-dependent proliferation. Knockdown of Piezo1 by siRNA (or an shRNA Piezo1 construct, not shown) reduced Piezo1 to 7% of wild type levels and prevented stretch-induced mitosis (Fig. 2A&B). Notably, long-term knockdown of Piezo1 also reduced steady state rates of proliferation (Fig. 2A, unstretched). Transfection of a GFP-Piezo1 construct not targeted by the siRNA rescued stretch-induced proliferation, indicating that proliferation following stretch requires Piezo1 (Fig. 2A&B). Piezo1 knockdown also blocked cell division following wound closure, compared to control monolayers (Fig. 2C). To test whether Piezo1 controlled epithelial cell division in vivo, we examined its role in zebrafish epidermis, a model for the simple epithelia that coat our organs. We assayed for H3P-positive cells in four-day old larvae zebrafish epidermis, a stage where cell division reaches a steady state rate (ED Fig. 4A and1). Using a CRISPR-based technique to knockout Piezo1 mosaically in the F0 generation4,5, we found that reducing Piezo1 levels to ~50% decreased the number of H3P-positive epidermal cells ~5-fold (Fig. 2D-F). Additionally, a photo-activated morpholino to Piezo1 also reduced epidermal cell proliferation by ~5-fold (ED Fig. 4B-D). Together, our data show that epithelial cells at steady state become stretched before they divide, that stretch is sufficient to rapidly activate cell division, and that cell division either at steady state or following experimental stretch requires the stretch-activated channel Piezo1.

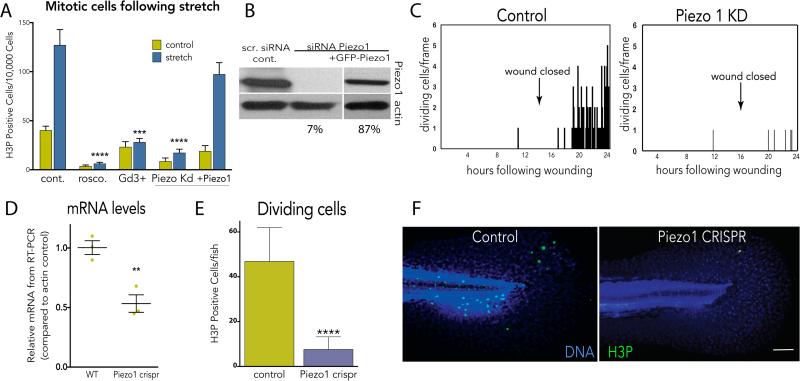

Figure 2. Stretch-induced mitosis requires the stretch-activated channel Piezo1.

(A) Inhibition or siRNA-mediated knockdown of Piezo1 blocks stretch-induced mitosis, and is rescued with Piezo1-GFP, where values are means of 6 measurements averaged from 5 experiments. (B) Immunoblot confirming knockdown and rescue (SI Fig.1 for full blots). (C) Piezo1 knockdown blocks cell division following wound closure, where graphs are representative of 20 similar videos. (D) CRISPR-mediated Piezo1 knockout reduces Piezo1 mRNA by 50% (n=3) and dramatically decreases mitosis rates, measured in 26 wild type and 53 knockout 4-day old larvae (E, F). Bar = 100μm (images represent 12 total for each). For all graphs, except (C), error bars = s.e.m. P values from an unpaired t-test are **<0.005, ***<0.0005, ****<0.0001.

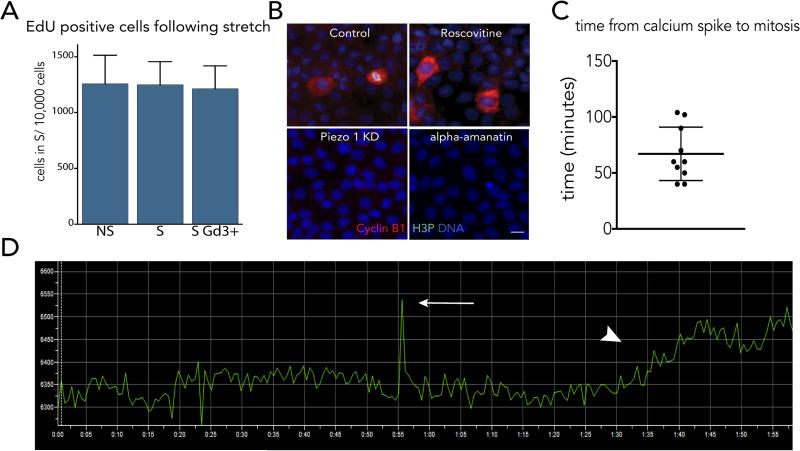

We next tested where in the cell cycle stretch activates Piezo1 to induce mitosis. Because the mitotic response to stretch is so rapid, it seemed unlikely that stretch-activation of Piezo1 triggers cells to transit through an entire cell cycle from G0 (~12-24 hours). Indeed, two hours of stretch did not increase the number of cells entering S phase, as measured by EdU incorporation (ED Fig 5A). Moreover, other reports find that stretch induces epithelial cells to enter the cell cycle but reach G1 only after six hours6-8. To determine if stretch activates mitosis at G2 or M, we tested whether stretch stimulates cyclin B, which accumulates in the cytoplasm at G2. To prevent cyclin B degradation as cells shift into mitosis, we measured cytoplasmic cyclin B accumulation in the presence of the Cdk1 inhibitor, roscovitine. We found that stretch induces cytoplasmic cyclin B accumulation over time (Fig. 3A & ED Fig. 5B). Inhibiting Piezo1 with gadolinium or transcription with alpha-amanitin blocks stretch-induced cyclin B synthesis (Fig. 3 A), suggesting that stretch-induced cyclin B induction requires both Piezo1 and transcription. However, because Piezo1 is a transmembrane protein that relays calcium in response to mechanical stress3,9-11, it likely activates transcription indirectly. Indeed, inhibiting calcium with either Ruthenium Red or BAPTA-AM blocked stretch-induced mitosis and cyclin B production, respectively, confirming that Piezo1 acts through calcium to activate mitosis (Fig. 3 C&D). Videos of MDCK monolayers expressing CMV-R-GECO112, reveal that a single spark of calcium precedes mitosis entry (noted by physiologic cell rounding) by ~65 minutes (ED Fig. 5B&C). Because both cyclin B and mitosis require Piezo1 and calcium influx (Fig. 3 C&D), we next investigated what induces proliferation in response to calcium influx. A top candidate is the Extracellular Signal Regulated Kinase (ERK1), a calcium-activated target of MEK1/213-15 with roles in controlling G2/M16-18. We found that stretch-induced calcium activates ERK1/2 (measured by phospho-ERK1/2 immunoblot) within only five minutes, but is blocked by gadolinium addition (Fig. 3E). Using the MEK1/2 inhibitor AZD6244 (and U0126, not shown), we found that both stretch-induced mitosis and cyclin B synthesis require the ERK1/2-MEK1/2 pathway (Fig 3C&D). Thus, we propose that stretch causes Piezo1 to trigger calcium currents that activate ERK1/2 via MEK1/2 to trigger cyclin B transcription and initiate mitosis (Fig. 3F).

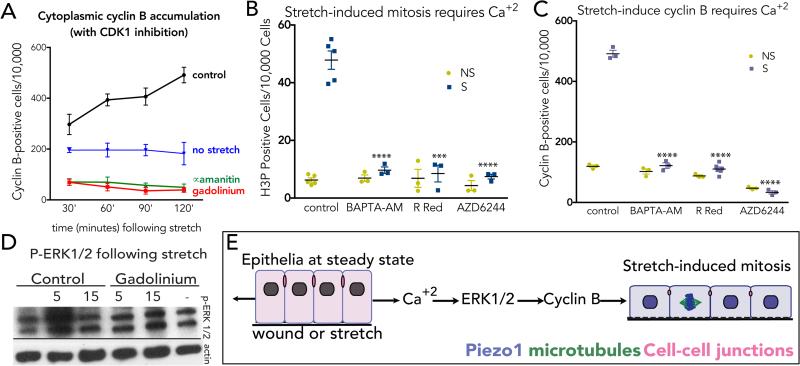

Figure 3. Stretch-activation of Piezo1 triggers calcium and ERK1/2-dependent cyclin B transcription.

(A) Stretch induces cyclin B accumulation (with CDK1 inhibition), which is blocked with Gd3+ or alpha-amanitin, where values are the means from 6 experiments, with error bars = s.e.m. P-values <0.0001 from two-way Anova. Inhibiting intracellular calcium (BAPTA-AM, Ruthenium Red) or MEK1/2 (AZD6244) blocks stretch-induced mitosis (B) and cytoplasmic cyclin B (with CDK1 inhibition) (C). Data points represent averaged means of 6 areas from 3 experiments. Error bars = s.e.m. P-values from an unpaired T-test are ****<0.0001 and ***<0.002. (D) Stretch rapidly activates ERK1/2 phosphorylation in a Piezo1-dependent manner (see SI Fig. 1 for full scans). (E) Model: stretch triggers cells in early G2 to activate Piezo1-dependent calcium influx, which stimulates ERK1/2-dependent transcription of cyclin B and cell division.

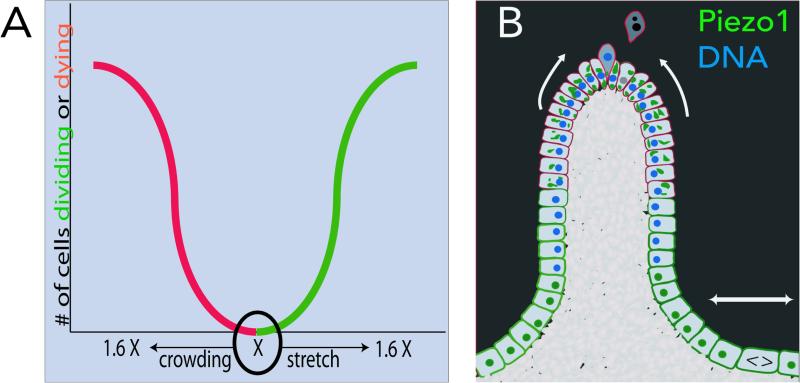

It is curious that one protein, Piezo1, can control two opposing processes—cell division and cell death—to regulate cell numbers. This seems especially surprising, given that Piezo1 triggers opposing outcomes through the same second messenger—calcium. Yet, the type of mechanical tension is critical for the type of response: we find that stretch induces cell division but not cell extrusion whereas crowding induces cell extrusion but not cell division (Fig. 4A&B). Interestingly, the magnitude of mechanical strain for each response is similar: 1.5-1.7-fold stretch induces cell division whereas 1.7-1.8-fold crowding induces cell extrusion (ED Fig. 6A)1. Similar paradoxical signalling controls opposing outcomes in other systems, but typically through secreted molecules19-21. For instance, IL-2 maintains homeostatic T cell numbers by controlling both cell division and cell death depending on the levels secreted 21. Thus, Piezo1 signalling through calcium may represent a new mechanism for regulating a paradoxical feedback loop. While the benefit of having a single regulator control two opposing processes is that its loss should downregulate both processes, Piezo1 mutations and misexpression frequently found in colorectal, gastric, and thyroid cancers suggest that Piezo1 may act as a tumor suppressor22-25. Future work will need to determine if Piezo1 misregulation is sufficient to drive tumorigenesis and if the relevant mutations affect both epithelial cell death and division.

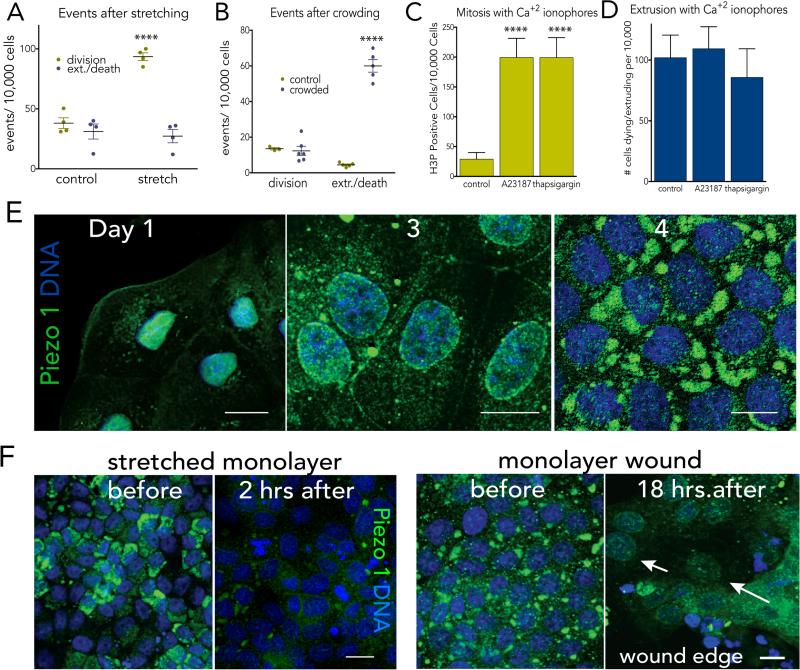

Figure 4. Piezo1 controls proliferation in response to stretch and extrusion and death in response to crowding.

Stretch triggers only mitosis (A) whereas crowding induces only cell extrusion/death (B), where values are averages of the means of 4 experiments from 6 fields each. Experimental induction of calcium influx induces proliferation, n=8 (C) but not extrusion/death, n=9 (D) within two hours. For all graphs, error bars = s.e.m. and P-values from an unpaired T-test are ****<0.0001 and ***<0.002. (E) Piezo1 (green) shifts from the nuclear envelope in cells at low density to the cytoplasm/plasma membrane to large cytoplasmic formations in cells at high density. (F) Piezo1 disappears after stretch or wounding, eventually localizing to nuclear envelope (arrows, wound). All images representative of 10 others, with scale bars=10μm.

How does Piezo1 differentially interpret crowding versus stretching? Cellular responses could depend on how the cell is primed, the levels and localization of Piezo1, as well as the type of tension. Our findings show that stretch-activation of Piezo1 target cells primed in early G2 to rapidly divide. It is not clear if Piezo1 also collaborates with Yap/Taz and ß-catenin upon stretch to promote cell cycle entry at G16,8 yet it is a tempting prospect, since tension-dependent Yap nuclear translocation requires Piezo1 in neuronal stem cells26. Older, crowded cells prone to extrusion may be post-mitotic, as typically seen in villus tips, and less likely to divide in response to calcium. The type of mechanical tension may also play a role in how Piezo1 signals. We find that while chemical activation of calcium currents is sufficient to activate cell division, it is not sufficient to promote cell extrusion and death (Figs. 4C&D). Thus, either thapsigargin and A23187 activate calcium at sites required for mitosis or crowding-induced extrusion requires mechanical crowding in addition to calcium currents. Finally, the ability of Piezo1 to sense different types of tension may depend on its subcellular localization and levels. At subconfluence, Piezo1 levels are low, localizing mainly to the nuclear envelope, but accumulate over time. In confluent but sparser epithelial regions prone to divide Piezo1 localizes to the plasma membrane and ER, whereas in crowded regions prone to extrude, it develops into large cytoplasmic aggregates (Fig. 4E). Interestingly, while Piezo1 accumulates over time, stretching dense MDCK monolayers either mechanically or by wounding causes it to dramatically drop and eventually relocalise to the nucleus (Fig. 4E). At lower densities, when Piezo1 is predominantly at the nucleus, stretch does not appear to play a significant role in regulating mitosis (ED Fig. 7B&C), potentially because the division rate is already very high. In this way, Piezo1 levels and localization could adjust to regulate cell numbers once cells reach a steady state: in sites where cells are sparse, Piezo1 localizes to sites where it may sense stretch, whereas sites where cells are older and crowded, Piezo1 accumulates into structures where it may sense crowding (EDFig. 6B). Excessive cell death or wounding may reset the cell clock by degrading Piezo1 so that it would start measuring cell numbers only once cells reach steady state again. Future studies will need to test if Piezo1 abundance and localization control its response to different mechanical forces.

Our work has defined a new role for mechanical tensions regulating constant epithelial cell numbers, essential to maintaining a tight barrier and preventing cancers from forming. We have found that Piezo1 acts to tightly link the number of cells dying with those dividing by measuring tensions. If epithelial cells become too dense, crowding induces some cells to extrude and die, yet if they become too sparse, stretch triggers some cells to rapidly divide to equilibrate epithelia to optimal densities.

Methods

Cell culture and stretching assays

MDCK II cells (tested for mycoplasma but not authenticated) (gift from K. Matlin, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL) were cultured in Dulbecco's minimum essential medium (DMEM) high glucose with 5% FBS (Atlas, Biologicals) and 100 μg/ml penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen) at 5% CO2, 37°C. Cell stretching was done either using: 1) A custom-designed Teflon chamber fabricated to culture cells on flexible a silicone membrane (2 × 2.4 cm, 0.5 mm thickness)1. Prior to cell seeding, 2 × 2.4 cm silicone membranes were stretched and coated with 5 μg ml−1 fibronectin (Sigma) at 37 °C for 1 h. To stretch membranes with our device, one edge of the silicone membrane was clamped in place, while the other side was clamped to a movable shaft, which moves through a Teflon chamber with a sealing gasket. The movable shaft was pulled out between 2-6 mm, resulting in stretch of 10-33%. 2.5 × 106 cells were plated onto the 2 × 2.4 cm silicone matrices in a neutral taut state in the device and grown to confluence, then stretched to desired lengths with control chambers being left in a neutral state. Epithelial monolayers were fixed in stretched or neutral state and stained. 2) Alternatively, 2 × 106 cells were grown to confluence in pronectin-coated flexcell plates designed for uniaxial stretch (Flexcell International Corporation) and stretched by clamping onto a custom-designed base plate (publicly available at Shapeways.com as ‘Narrow Bump Base in white strong flexible nylon plastic’) using two ‘Clamp Bars in Stainless Steel’ (also at Shapeways.com). The clamp bars and base must be tapped with a ¼-20 tap to match steel ¼-20 fully threaded studs and rods and capped with knurled style thumbscrews (both Essentra Components).

Wounding assays and live cell imaging

Control MDCK II cells or those expressing a pTRIPZ piezo1 shRNA construct were grown to confluence in 24-well glass bottom dishes (MatTek) or 8-chamber slides (Labtek, Fisher Scientific). Cells were treated with 1.5 μg ml−1 doxycycline (Sigma) for 48 hours to knockdown Piezo1. For wounding experiments, monolayers were scratched with a 10μl pipet tip. Cells were imaged in complete DMEM supplemented with 10 mM HEPES (Invitrogen) on a Nikon TE200 inverted microscope at 37°C or an EVOS FL Auto with a Stable Z controller heated stage (Bioptechs) at 37°C. Time lapse videos were analyzed using ImageJ.

For calcium imaging, MDCK cells were transfected with CMV-R-GECO1, a gift from Robert Campbell (Addgene plasmid # 32444)12 and imaged continuously (3 second intervals) for four hours. For cell cycle imaging, MDCK cells were transfected with pEGFP-PCNA-IRES-puro2b, a gift from Daniel Gerlich (Addgene plasmid # 26461)1. Cells were imaged with a Nikon wide-field microscope at 37°C coupled to an Andor Clara interline CCD camera.

Drug treatments

The following drugs were used in experiments: 10 μM gadolinium III chloride (Gd3+) (for both zebrafish and cell culture) to block Piezo1, and 30μM Ruthenium Red or 10μM BAPTA-AM were used to inhibit calcium (all from Sigma). 10 μM Roscovitine was used to block CDK1. 5μM alpha-amanitin (Sigma) was used to inhibit RNA polymerase II and III. 1μM AZD6244 (Cayman Chemical) or 1μM U0126 (Sigma) were used to inhibit MEK1 and 2. 1μM A23187 or 5μM Thapsigargin (both from Sigma) were used to induce calcium influx.

Cell immunostaining

Cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PBS at room temperature for 20 min. Fixed cells were rinsed three times in PBS, permeabilised for 10 min with PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100, and blocked in AbDil (PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100 and 2% BSA), then incubated in primary antibody (in AbDil) for 1 h, washed three times with PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100, and incubated in secondary antibodies. Antibody concentrations used for immunostaining were: 1:1000 mouse phospho-Histone H3 (S10) (Cell Signalling Technology); 1:1000 rabbit Histone H3 (phospho S10) (Abcam); 1:200 mouse ß-Catenin (Cell Signalling Technology); 1:200 rabbit Cyclin B1 XP (Cell Signalling Technology); 1:200 rabbit Piezo1 (Novus, NBP1-78446). Only this Piezo1 antibody reliably worked for Piezo1 immunostaining, as it vanishes in cells mosaically expressing a Piezo1-shRNA-mCherry construct (EDFig. 5A). Actin was detected using 0.1 μg/ml Alexa Fluor 647–phalloidin (Invitrogen). Replicating DNA was detected using a Click-it EdU labeling kit, according to the manufacturer's protocol (Life Technologies) Alexa Fluor 488, 568 and 647 goat anti–mouse and anti–rabbit IgG were used as secondary antibodies (Invitrogen). DNA was detected with 1 μg/ml DAPI in all fixed cell experiments.

Fluorescent Microscopy

Images were captured on a Nikon Eclipse 90i using a x40 plan fluor 0.75 lens with a Retiga 2000R cooled mono 12-bit camera (Q Imaging) driven by NIS Elements (Nikon) or on a Nikon Eclipse TE300 inverted microscope converted for spinning disc confocal microscopy (Andor Technologies) using a 20X or 60X plan fluor 0.95 oil lens with an electron-multiplied cooled CCD camera 1,000 × 1,000, 8 × 8 mm2 driven by the IQ software (Andor Technologies). NIS Elements was used to quantify cell densities and measure cell length. Cell staining with cytoplasmic Cyclin B1 or H3P were quantified per 10,000 cells using Nikon Elements Software.

FACScan

106 MDCK II cells were collected by trypsinising and rinsing twice with 2 ml PBS. The cell pellet was resuspended in 250 μl cold PBS and fixed for 2 hours with 800 μl ice-cold 100% ethanol at −20°C. The tubes were warmed to 37 °C for 10 min and the cells were washed twice with 1 and 2 ml PBS. The cell pellet was resuspended in 500 μl PI staining solution (50 μg/ml PI, 0.1% Triton-X, 0.2 mg/ml RNase A in PBS), vortexed and incubated for 20 min at 37°C. The samples were filtered and then analysed for propidium iodide fluorescence with a BD FACScan Analyzer.

Piezo1 knockdown and Western Blot analysis

Zebrafish (Danio Rerio): For CRISPR Mediated Knock-down of Piezo1, Exon 2 of the zebrafish piezo1 gene was targeted for CRISPR knockdown and the target sequence was GTAGCGAAATATGCAGGctgagg (exonic sequence is uppercase while intronic sequence is lowercase). The 20 nucleotides minus the NGG motif was cloned into a plasmid containing the RNA loop structure required for recognition by the Cas9 enzyme and a T7 binding site, which allowed for the synthesis of single guide RNA (sgRNA). To induce knockdown of Piezo1, 75pg of sgRNA and 1200pg of Cas9-NLS encoding RNA were injected at the one cell stage wild type (AB) embryos and mitosis rates measured in mosaic F0 larvae at day 4 post-fertilization. For Cas9-NLS mRNA synthesis, pT3Ts-nCas9n was obtained from the Chen lab via Addgene (46757).

Piezo1 morphants were made by mixing 4ng translation blocking morpholino 1:1 with a 25bp antisense containing a photolinker and a 4bp mismatch and injecting into 1 cell stage wild-type (AB) embryos. At 28-32 hpf, embryos were exposed to 350nm light for 20 seconds to activate the morpholino, then fixed and immunostained at 4 dpf. All experiments on zebrafish were done with accordance to our zebrafish IACUC protocol, approved by the University of Utah IACUC board.

MDCKs: siRNA to canine Piezo1 shRNA (from Sigma to the sense sequence GUGCUAUGGUCUCUGGGAUdTdT) was transfected with RNAiMAX (Thermofisher) into MDCK cells one day after plating. For rescue, 1 μg GFP-Piezo1 construct (kind gift from Ardem Patapoutian) was transfected one day following. Alternatively, a pTRIPZ human piezo1 lentiviral plasmid (from Fisher Scientific to the sense sequence UGUCCUCCACACACAUCCA) was transduced with psPAX and p60 (given by M. VanBrocklin, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT) into MDCK cells and selected for 14 days with 2 μg ml−1 puromycin and expression induced for 3 days with 1.5 μg ml−1 doxycycline (Sigma). Cell lysate was obtained by trypsinising cells, resuspending the pellet in NP40 cell lysis buffer containing 1X PMSF and protease inhibitors (Life Technologies) and centrifuging for 10 min at 13,000 rpm at 4°C. 30 μg of protein lysate (determined by Bradford assay) was run on a 3–8% Tris-Acetate gel at 150 V for 1 h, transferred to PVDF, and probed for Piezo1 (Proteintech) or mouse-alpha-tubulin (Sigma) Ab by standard enhanced chemiluminescence.

Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis, all experiments, including those in zebrafish, were repeated on three separate days to ensure enough variation and numbers to measure significance by unpaired T-tests. To ensure randomization of measurements, we took random pictures within the middle (region of consistent stretch or crowding) of silicone membrane for quantification. For zebrafish experiments, all fish were analysed, so not randomized or blinded. After noticing a trend in low-density epithelia not responding to stretch, we excluded them in our main data, but included them in Supplementary Fig. 4. Variance between compared samples was similar and expressed as s.e.m. in graphs.

27. Held, M. et al. CellCognition: time-resolved phenotype annotation in high-throughput live cell imaging. Nat Methods 7, 747-754, doi:10.1038/nmeth.1486 (2010).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors on reasonable request, see author contributions for specific data sets. The source data for the western blots in the figures are available in Supplementary Figure 1.

Extended Data

EDFigure 1. Profile of epithelial cell proliferation and cell density over time.

(A) Daily proliferation rates of MDCK cells, as measured by phospho-Histone H3 (H3P) immunostaining, where asterisk indicates when confluence is reached (n=3). Cell division slows but does not stop at day 5. (B), Cell density plateaus by 5 days of growth when cells reach ~11/1000μm2 (n=3). All values are the mean of ten fields from 3 independent experiments with error bars as s.e.m. (C) Cell cycle profiles by FACS at day 1 and day 5 after plating at high density.

EDFigure 2. Epithelial cells divide in sparsest regions of epithelia.

Density of cells in dividing versus non-dividing regions of epithelia, as measured by cell length through longest axis in 4 videos (except fixed colon sections) in (A) human colon tissue n=8 (B) developing zebrafish epidermis, n=50, and (C) MDCK cells in culture, n=50, where p-value of unpaired t-test is 0.0001 for **** and error bars=s.e.m for all graphs.

EDFigure 3. Stretching steady state monolayers.

(A) New printable device used for stretching cells uniaxially on Flexcell plates, unassembled (top) and assembled in stretched state (bottom) and schematic of uniaxial stretch on an epithelium in the unassembled (top) and assembled (bottom) states (photo-credit, Jody Rosenblatt). (B) Immunostained MDCK monolayers before (top) and after (bottom) stretching, representative of >200 images captured each. Bar=10μm

EDFigure 4. Piezo1 morphants have reduced cell division in zebrafish epidermis at steady state.

(A) Cell division in zebrafish reaches a low steady state at day 4-5 post-fertilization, where n=50 fish each day and error bars=s.e.m. (B) Photo-activation of zebrafish injected with Piezo1 translation-blocking morpholino results in knockdown of Piezo1 protein, as shown by an immunoblot. Please see SI Figure 1 for scan of full blots. (C, D) Zebrafish Piezo1 morphants have dramatically reduced epidermal mitoses at 5 days post-fertilisation when cells homeostatic growth rate, where values are the averages of the means from 3 separate experiments, error bars are the s.e.m. of the mean, and the P-value is from an unpaired t-test is <0.005. Each micrograph is representative of ~75 samples, bar=100μm.

EDFigure 5. A single calcium spark occurs around an hour before cells divide.

(A) Blocking stretch-induced proliferation with gadolinium at two hours post-stretch does not affect the percentages of cells in S phase, as measured by EdU incorporation from the mean of six independent experiments, where error bars are s.e.m. and P values from a t-test compared to the non-stretched control show no significance. (B) Inhibition of Piezo1 with Gd3+ or transcription with alpha-amanitin blocks stretch-induced cytoplasmic cyclin B accumulation and mitosis (H3P), where each micrograph is representative of >100 samples except for alpha-amanitin (40 samples) and bar=10μm. (C) Quantification of time from calcium spark to cell rounding measured from 10 mitotic events in 8 videos. Error bars=s.e.m. (D) Sample graph measuring the time (minutes) from calcium spark (arrow) to cell rounding (arrowhead) in MDCK cells expressing the calcium indicator, CMV-R-GECO1 using Nikon Elements.

EDFigure 6. Models for how Piezo1 controls cell division in response to stretch and cell extrusion in response to crowding.

(A) Theoretical graph of density-dependent Piezo1 function for cell division and cell death: Epithelia trend to a steady-state density, X. If density is reduced, stretching causes Piezo1 to activate cell division, if it increases, crowding causes Piezo1 to activate cells to extrude and die. (B) Schematic showing how Piezo1 (green) localizes to plasma membrane in sub-regions of epithelia that are sparser and divide and accumulate into cytoplasmic aggregates in sub-regions that are crowded and extrude.

EDFigure 7. Stretch affects cells at steady state to enter mitosis.

(A) Characterization of Piezo1 antibody using an shRNA to Piezo1 tagged with mCherry indicates that cells expressing red mCherry lack Piezo1 (green). Micrographs are representative of ~50 samples and bar=10μm. (B) High-density monolayers (>500 cells/40X field) where intrinsic proliferation rate is low (<50 H3P-positive cells/10,000 cells) proliferate in response to mechanical stretch (with P value= 0.0007 from a unpaired t-test with error bars=s.e.m.) or wounding. (C) Low density MDCK monolayers just reaching confluence with a higher intrinsic rate of proliferation (>50 H3P-positive cells/10,000 cells) do not significantly proliferate in response to stretch or wounding (P value from a t-test is not significant). N=12 experiments for each case.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Daniel Wright for design consultation and printing our new stretch device prototypes, Masaaki Yoshigi for the previous stretch device, Leif Zinn-Bjorkman for video analysis, Ardem Patapoutian for a GFP-Piezo1 construct, David Morgan and Bruce Edgar for cell cycle experimental advice and Bruce Edgar for helpful comments on the manuscript. An National Institute of Health Director's New Innovator Award 1DP2OD002056-01, R01GM102169, and University of Utah Funding Incentive Seed Grant to J. R. and P30 CA042014 awarded to Huntsman Cancer Institute core facilities supported this work. We thank the Fluorescence Microscopy and Mutation Generation and Detection Cores in the Health Sciences Cores at the University of Utah. An NCRR Shared Equipment Grant # 1S10RR024761-01 paid for microscopy equipment.

Footnotes

Contributions:

J. R. designed all of the experiments, interpreted, and analysed all data, and wrote the manuscript. J. R. and J. L. designed the new stretch device. J.L. and S. A. G. performed most stretch and wound healing experiments and FACs analysis throughout the paper. P. D. L. performed the first experiments showing stretch induces cell division. K. E. performed the immunoblots and the EdU experiments. V. K. did calcium imaging. C.F.D produced F0 CRISPR mosaic knockout zebrafish, M. J. R. injected morpholinos into zebrafish embryos and helped with live imaging. J. R. performed the experiments using zebrafish and requirement for Piezo1 at steady state and co-quantified most of the experiments. All authors edited the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

References:REFERENCES

- 1.Eisenhoffer GT, et al. Crowding induces live cell extrusion to maintain homeostatic cell numbers in epithelia. Nature. 2012;484:546–549. doi: 10.1038/nature10999. doi:10.1038/nature10999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Puliafito A, et al. Collective and single cell behavior in epithelial contact inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:739–744. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007809109. doi:10.1073/pnas.1007809109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coste B, et al. Piezo1 and Piezo2 are essential components of distinct mechanically activated cation channels. Science. 2010;330:55–60. doi: 10.1126/science.1193270. doi:10.1126/science.1193270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah AN, Davey CF, Whitebirch AC, Miller AC, Moens CB. Rapid reverse genetic screening using CRISPR in zebrafish. Nat Methods. 2015;12:535–540. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3360. doi:10.1038/nmeth.3360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah AN, Moens CB, Miller AC. Targeted candidate gene screens using CRISPR/Cas9 technology. Methods Cell Biol. 2016;135:89–106. doi: 10.1016/bs.mcb.2016.01.008. doi:10.1016/bs.mcb.2016.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benham-Pyle BW, Pruitt BL, Nelson WJ. Cell adhesion. Mechanical strain induces E-cadherin-dependent Yap1 and beta-catenin activation to drive cell cycle entry. Science. 2015;348:1024–1027. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa4559. doi:10.1126/science.aaa4559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azzolin L, et al. YAP/TAZ Incorporation in the beta-Catenin Destruction Complex Orchestrates the Wnt Response. Cell. 2014;158:157–170. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.013. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aragona M, et al. A mechanical checkpoint controls multicellular growth through YAP/TAZ regulation by actin-processing factors. Cell. 2013;154:1047–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.042. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coste B, et al. Piezo1 ion channel pore properties are dictated by C-terminal region. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7223. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8223. doi:10.1038/ncomms8223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coste B, et al. Piezo proteins are pore-forming subunits of mechanically activated channels. Nature. 2012;483:176–181. doi: 10.1038/nature10812. doi:10.1038/nature10812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ge J, et al. Architecture of the mammalian mechanosensitive Piezo1 channel. Nature. 2015 doi: 10.1038/nature15247. doi:10.1038/nature15247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao Y, et al. An expanded palette of genetically encoded Ca(2)(+) indicators. Science. 2011;333:1888–1891. doi: 10.1126/science.1208592. doi:10.1126/science.1208592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agell N, Bachs O, Rocamora N, Villalonga P. Modulation of the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway by Ca(2+), and calmodulin. Cell Signal. 2002;14:649–654. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(02)00007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chuderland D, Marmor G, Shainskaya A, Seger R. Calcium-mediated interactions regulate the subcellular localization of extracellular signal-regulated kinases. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:11176–11188. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709030200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M709030200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chuderland D, Seger R. Calcium regulates ERK signaling by modulating its protein-protein interactions. Commun Integr Biol. 2008;1:4–5. doi: 10.4161/cib.1.1.6107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shapiro PS, et al. Activation of the MKK/ERK pathway during somatic cell mitosis: direct interactions of active ERK with kinetochores and regulation of the mitotic 3F3/2 phosphoantigen. J Cell Biol. 1998;142:1533–1545. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.6.1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wright JH, et al. Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase activity is required for the G(2)/M transition of the cell cycle in mammalian fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:11335–11340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayne C, Tzivion G, Luo Z. Raf-1/MEK/MAPK pathway is necessary for the G2/M transition induced by nocodazole. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:31876–31882. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002766200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M002766200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hart Y, Alon U. The utility of paradoxical components in biological circuits. Mol Cell. 2013;49:213–221. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.01.004. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hart Y, Antebi YE, Mayo AE, Friedman N, Alon U. Design principles of cell circuits with paradoxical components. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:8346–8351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117475109. doi:10.1073/pnas.1117475109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hart Y, et al. Paradoxical signaling by a secreted molecule leads to homeostasis of cell levels. Cell. 2014;158:1022–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.033. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng Y, et al. Analysis of DNA methylation patterns associated with the gastric cancer genome. Oncol Lett. 2014;7:1021–1026. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.1838. doi:10.3892/ol.2014.1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abend M, et al. Iodine-131 dose dependent gene expression in thyroid cancers and corresponding normal tissues following the Chernobyl accident. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39103. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039103. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0039103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donnard E, et al. Mutational analysis of genes coding for cell surface proteins in colorectal cancer cell lines reveal novel altered pathways, druggable mutations and mutated epitopes for targeted therapy. Oncotarget. 2014;5:9199–9213. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2374. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.2374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spier I, et al. Exome sequencing identifies potential novel candidate genes in patients with unexplained colorectal adenomatous polyposis. Fam Cancer. 2016;15:281–288. doi: 10.1007/s10689-016-9870-z. doi:10.1007/s10689-016-9870-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pathak MM, et al. Stretch-activated ion channel Piezo1 directs lineage choice in human neural stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:16148–16153. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409802111. doi:10.1073/pnas.1409802111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors on reasonable request, see author contributions for specific data sets. The source data for the western blots in the figures are available in Supplementary Figure 1.