Abstract

One of the most fundamental and challenging questions in the cancer field is how immunity in cancer patients is transformed from tumor immunosurveillance to tumor-promoting inflammation. Here, we identify the transcription factor STAT3 as the culprit responsible for this pathogenic event in lung cancer development. We found that antitumor type 1 CD4+ T helper (Th1) cells and CD8+ T cells were directly counter-balanced in lung cancer development with tumor-promoting myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and suppressive macrophages, and that activation of STAT3 in MDSCs and macrophages promoted tumorigenesis through pulmonary recruitment and increased resistance of suppressive cells to CD8+ T cells, enhancement of cytotoxicity towards CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, induction of regulatory T cell (Treg), inhibition of dendritic cells (DCs), and polarization of macrophages toward the M2 phenotype. The deletion of myeloid STAT3 boosted antitumor immunity and suppressed lung tumorigenesis. These findings increase our understanding of immune programming in lung tumorigenesis and provide a mechanistic basis for developing STAT3-based immunotherapy against this and other solid tumors.

Keywords: myeloid cell, MDSC, STAT3, lung cancer

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in the United States and worldwide, with only 16% of patients surviving 5 years (1, 2). The most predominant risk factor for lung cancer is tobacco smoking, which accounts for about 87% of all lung cancer cases (3). Tobacco smoke induces genetic mutations and pulmonary inflammation (4, 5). Although the role of genetic mutations in lung cancer has been extensively investigated, the importance of pulmonary inflammation in lung cancer development has come to be appreciated more recently (4–6). Epidemiologic studies indicate that chronic lung inflammation is an independent risk factor for lung cancer (7). Mouse studies also suggest the importance of pulmonary inflammation in the onset and development of lung cancer (8–16).

The normal role of immunity is to clear pathogens and damaged or transformed cells. Although it remains largely unknown how tumor-suppressive immunity becomes tumor-promoting inflammation during tumorigenesis, evidence suggests that myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and macrophages could be the main perpetrators (17, 18). Whereas macrophages are mature myeloid cells, MDSCs are a heterogeneous group of myeloid cells comprising myeloid progenitors and immature myeloid cells, which are broadly defined as CD11b+GR1+ cells in mice and CD11b+CD33+HLA-DR– cells in humans. As seen in several types of cancer, MDSCs are significantly increased in human patients and mice with lung cancers (19–21). In fact, increased MDSCs in blood significantly correlate with the risk, progression, and poor prognosis of lung cancer in humans (22–24). Depletion of MDSCs restores antitumor immunity, decreases the growth and migration of injected lung cancer cells, and increases the sensitivity to antitumor therapies of the injected lung cancer cells in mouse xenograft models (25–27). Similarly, high macrophage counts in lung cancer tissues are associated with tumor metastasis and poor patient survival, whereas depletion of alveolar macrophages reduces lung tumor formation and growth in a mouse model of lung cancer (13, 28, 29). Different from MDSCs, which are mainly pro-tumorigenic, macrophages can be both antitumorigenic (M1) and pro-tumorigenic (M2), depending on microenvironment (17, 18). Indeed, macrophages show an overall M1 phenotype at the early stages and a general M2 phenotype at the late stages of lung tumorigenesis (13).

However, it remains to be investigated how MDSCs and macrophage M1/M2 polarization are regulated and how MDSCs and macrophages exert their pro-tumorigenic role in lung cancer. In this study, we identified the transcription factor signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), a master regulator of cell proliferation, survival, and inflammatory responses (30), as a major driver of MDSC and macrophage pro-tumorigenic states. STAT3 promotes pulmonary recruitment and resistance to CD8+ T cells of MDSCs and macrophages, arms MDSCs and macrophages to kill CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and to induce Treg development and suppress dendritic cells (DCs), and skews polarization of macrophages from M1 toward M2 phenotype in lung tumorigenesis. Moreover, deletion of myeloid STAT3 reverses these pathogenic processes, leading to lung cancer suppression. These preclinical studies increase our understanding of lung cancer immunology and suggest a novel, feasible, and effective STAT3-based immunotherapy for lung cancer prevention and treatment. Given the important roles of tumor-associated myeloid cells in many other solid tumors, these studies are relevant to the cancer field at large.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Lysozyme M-Cre mice, CD8 knockout mice and perforin knockout mice were purchased from Jackson laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA), and STAT3flx/flx mice have been described (15). These mice were backcrossed to the FVB/N background more than 10 times. All animals were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions at the Hillman Cancer Center of the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute. Animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Pittsburgh.

Lung carcinogenesis

Mice were intraperitoneally (i.p.) injected with urethane (1 mg/g body weight, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) once per week for six weeks. Six weeks post urethane treatment, all mice were sacrificed for lung tumor examinations. Some mice were also injected i.p. with neutralizing antibody to IFNγ (25 μg/g body weight) or a control purified rat IgG (BioXCell, West Lebanon, NH, USA) twice-weekly starting from 1 day before the first injection of urethane. Surface tumors in mouse lungs were counted by three blinded readers under a dissecting microscope. Tumor diameters were determined by microcalipers.

Bronchioalveolar lavage (BAL)

Upon sacrifice, mice lungs were lavaged with phosphate buffered saline as described (31). The recovered BAL fluids (BALF) were centrifuged. Cells from BALF were visualized and counted on Hema 3-stained cytocentrifuge slides.

Histology and immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Mouse and human lung tissue histology and IHC were performed as described (32, 33). Antibodies used are listed in Supplementary Table S1. The human lung tumor tissue arrays were provided by University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute Lung Cancer Specialized Program of Research Excellence (SPORE), and the patient demographics and clinicopathological characteristics are summarized in Supplementary Table S2. The lung inflammation in cancer patients was assessed on the resection specimens. It was based on the intensity of the infiltrate around and between the tumor cells. Barely any lymphocytes was considered “mild”, a very thick rim of lymphocytes and easily identifiable lymphocytes within the tumor was “severe”; everything in between was “moderate”. Myeloid cells with nuclear immunoreactive STAT3 were counted in randomly selected microscopic fields in each sample. Scores were averaged and 50 per microscopic field were used for the cutoff of high and low STAT3 activation. The human studies were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

BrdU labeling

Mice were i.p. injected with BrdU (100 mg/kg, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) 24 h prior to sacrifice. Mouse lung sections were stained with anti-BrdU (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA).

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis

Mouse lung tissues and cells were subjected to RNA extraction, RNA reverse transcription and real-time PCR as described (33–35). PCR primers used are listed in Supplementary Table S3.

Flow cytometry analysis

Flow cytometry analyses were performed as described (36). Antibodies used are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

In vitro transwell migration and invasion assays

Peritoneal macrophages were obtained from urethane-treated STAT3ΔMye mice and STAT3WT mice 3 days after i.p. injection of thioglycolate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and plated in the upper chamber of transwell coated with Matrigel (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA, USA). The lower chambers were seeded with murine lung cancer cells or only contained culture medium. Cells were incubated for 24 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. Nonmigrated cells were scraped from the upper surface of the membrane (8 μm pore size) with a cotton swab, and migrated cells remaining on the bottom surface were stained with crystal violet.

Immunofluorescence (IF) analysis

Immunofluorescence analyses were performed and the staining intensities of the indicated proteins were measured by ImageJ as described (37, 38). Antibodies used are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

In vitro macrophage polarization assays

Peritoneal macrophages obtained from STAT3ΔMye mice or STAT3WT mice were cultured in normal culture medium or lung cancer conditional medium for up to 6 days, followed by immunofluorescence (IF) analysis to visualize the expression levels of iNOS and arginase.

In vitro coculture of MDSCs and T cells

MDSCs were isolated from the bone marrows of urethane-treated STAT3ΔMye mice and STAT3WT mice using MDSC purification kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. CD11b+ cells, CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ T cells were isolated from the spleens of WT mice using magnetic microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, USA) per manufacturer’s instructions. The purified MDSCs and T cells were cocultured in 2:1 or 4:1 in normal plates or in different chambers of transwell plates with 0.4 μm pore membrane insert for up to 6 days, followed by different analyses described above.

Statistical Analysis

Student’s t test (two tailed) was used to assess significance of differences between two groups, and p values < 0.05 and 0.01 were considered statistically significant and highly statistically significant, respectively (39). Logistic regression analysis was used to compare the pulmonary inflammation in lung cancer patients between high and low myeloid STAT3 activation groups. Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test and log-rank test were used to compare overall patient survival between high and low myeloid STAT3 activation groups (32). In addition to conventional P values (P), we also provided sex- and tumor stage–adjusted P values (Padj) for those human studies.

Results

Myeloid STAT3 activation associated with lung inflammation and poor patient survival

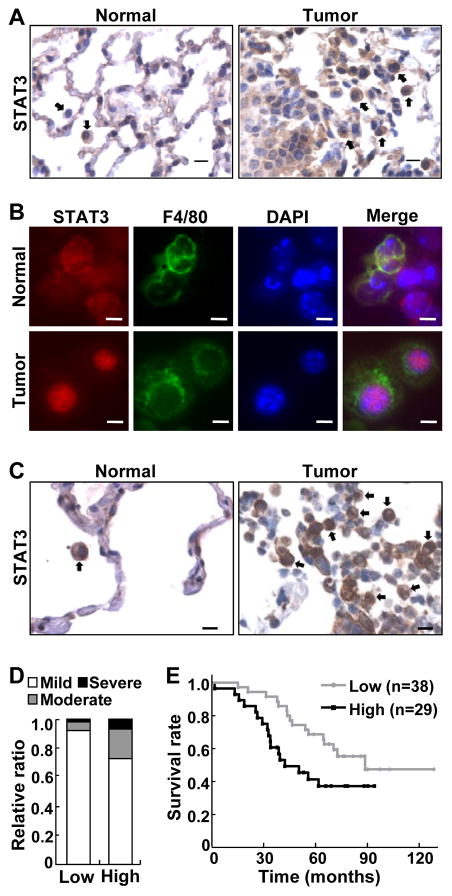

To investigate the role of STAT3 in lung cancer–associated inflammation, we initially examined whether STAT3 was activated in myeloid cells within or surrounding lung tumors. Myeloid cells play a central role in immune responses and are the most predominant immune cells associated with lung and other solid tumors (40), with infiltrations of myeloid cells associated with tumor metastasis and poor patient survival (41). In agreement with those previous findings, myeloid cells were readily detected surrounding endogenously arising mouse lung tumors induced by the tobacco carcinogen urethane, whereas very few myeloid cells were found in the normal lung tissues (Fig. 1A). Notably, these tumor-associated myeloid cells exhibited a strong nuclear expression of STAT3 (Fig. 1A and B), indicating high STAT3 activation in these immune cells.

Figure 1. Activation of pulmonary myeloid STAT3 was associated with lung inflammation and poor survival of lung cancer patients.

(A) IHC analysis showing increased myeloid cells with high STAT3 activation in murine lung tumors. Normal lung tissues were used as controls. Representative myeloid cells are indicated by arrows. Scale bar: 10 μm. (B) IF staining showing increased STAT3 activation in lung F4/80+ myeloid cells of urethane-treated mice. Scale bar: 5 μm. (C) IHC analysis showing increased STAT3 activation in myeloid cells associated with lung tumors from human patients. Matched normal human lung tissues were used as controls. Representative myeloid cells are indicated by arrows. Scale bar: 10 μm. (D) Association of myeloid STAT3 activation with increased lung inflammation in lung cancer patients (P = 0.0413; Padj = 0.0418). (E) Association of myeloid STAT3 activation with poor survival of lung cancer patients (P = 0.0140; Padj = 0.0223).

The findings from the mouse model were relevant to human lung cancer, because the same phenotypes were also detected in human lung cancer (Fig. 1C). High myeloid STAT3 activation was associated with increased pulmonary inflammation in lung cancer patients (Fig. 1D). Statistical analyses indicated that high myeloid STAT3 activation increased pulmonary inflammation risk 5.419 fold in lung cancer patients. Moreover, high myeloid STAT3 activation was associated with poor survival of lung cancer patients (Fig. 1E). This association was more significant in lung cancer patients at the age of 65 or older (Supplementary Fig. S1). These data suggest that myeloid STAT3 activation may be an important mechanism underlying pro-tumorigenic inflammation and lung cancer development. These data also support that murine lung cancer induced by urethane closely resembles its human counterpart.

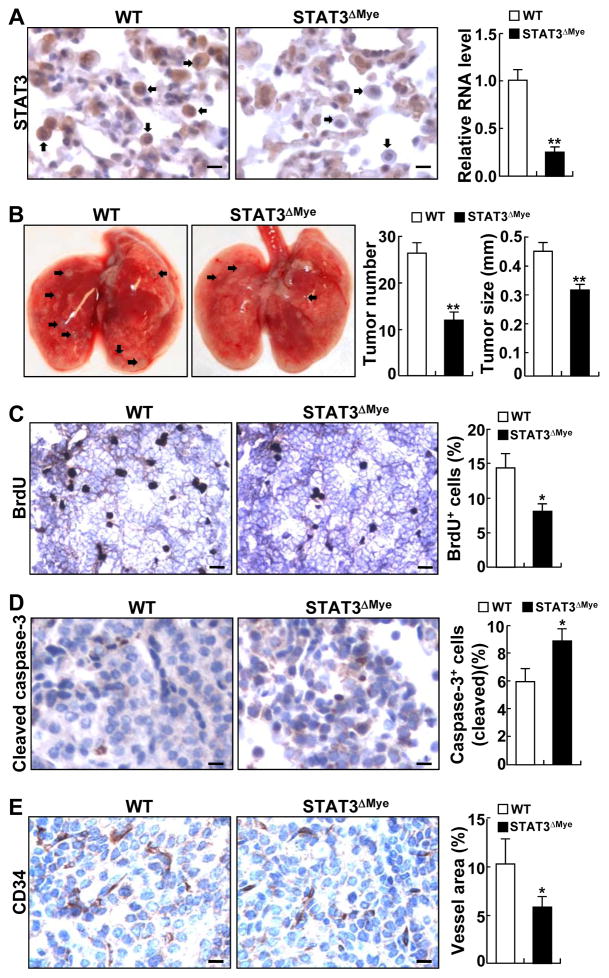

Deletion of myeloid STAT3 prevents urethane-induced lung carcinogenesis in mice

To examine the functional significance of myeloid STAT3 in lung tumorigenesis, we bred STAT3flx/flx (referred to as wild-type, WT or STAT3WT) mice with lysozyme M-Cre mice and generated STAT3flx/flx/lysozyme M-Cre (referred to as STAT3ΔMye) mice, in which STAT3 was selectively and efficiently deleted in myeloid cells, particularly in macrophages, MDSCs, and neutrophils (Fig. 2A, also see Supplementary Figs. S2 and S3). It should be pointed out that STAT3 is only partially deleted in DCs in the mice. These data are highly consistent with previous studies using the same strategy for gene deletions (42, 43).

Figure 2. Deletion of myeloid STAT3 prevented urethane-induced lung carcinogenesis in mice.

(A) IHC and qPCR analysis showing selective deletion of STAT3 from myeloid cells in lung tissue and BALF of STAT3ΔMye mice. Representative myeloid cells are indicated by arrows. Scale bar: 10 μm. (B) Decreased lung tumor multiplicities and sizes in STAT3ΔMye mice treated with urethane. Representative lung tumors are indicated by arrows. (C) BrdU labeling showing decreased proliferation rate of lung tumor cells in STAT3ΔMye mice. Scale bar: 40 μm. BrdU-positive tumor cells were counted and represented as the percentage of total tumor cells. (D) IHC analysis of cleaved caspase-3 showing increased apoptosis of lung tumor cells in STAT3ΔMye mice. Scale bar: 20 μm. Cleaved caspase-3-positive tumor cells were counted and represented as the percentage of total tumor cells. (E) IHC analysis of CD34 showing decreased lung tumor angiogenesis in STAT3ΔMye mice. Scale bar: 20 μm. The intensities of CD34 staining were measured by ImageJ and used as the indicator of blood vessel density. In A–E, data shown are means ± SD (n ≥ 4; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01).

STAT3ΔMye mice did not show apparent abnormalities in lung size or morphology (data not shown). After exposure to urethane, both STAT3ΔMye and STAT3WT mice developed lung tumors (Fig. 2B). However, lung tumors in STAT3ΔMye mice were significantly fewer and smaller. Histopathological analysis indicated that STAT3ΔMye mice had significantly fewer atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (AAH), adenomas (AD) and adenocarcinomas (AC) in their lungs (Supplementary Fig. S4). These findings suggest that myeloid STAT3 contributes to both the initiation and progression of lung cancer. In further support of this, lung tumors in STAT3ΔMye mice had less proliferation and a significantly higher cell death rate (Fig. 2C and D). Moreover, lung tumors in STAT3ΔMye mice exhibited significantly less angiogenesis (Fig. 2E). Lung tumors in STAT3ΔMye mice and STAT3WT mice were pathogenically the same. They shared similar morphologies and were surfactant protein C (SP-C)-positive and clara cell secretory protein (CCSP)-negative (Supplementary Fig. S5). This is also in line with the general belief that the SP-C positive alveolar type II epithelial cells and bronchioalveolar stem cells (BASCs) are the cells-of-origin of lung cancer (15). Collectively, these data indicate that myeloid STAT3 stimulates proliferation and survival of malignant cells as well as tumor angiogenesis, promoting both the initiation and progression of lung cancer.

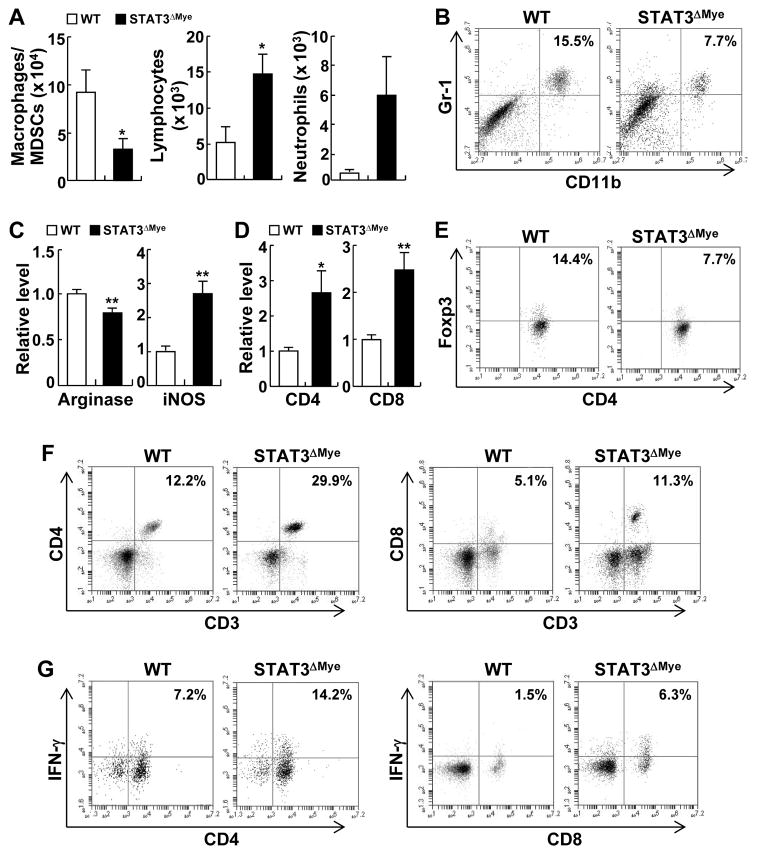

STAT3ΔMye mice had less tumorigenesis, lower inflammation, and increased antitumor immunity

To investigate the molecular and cellular mechanisms by which myeloid STAT3 promotes lung tumorigenesis, we initially compared the immune cells in the lungs of STAT3ΔMye mice and STAT3WT mice following exposure to urethane. We found that the number of macrophages and MDSCs was significantly decreased in BALF from STAT3ΔMye mice treated with urethane, in comparison to urethane-treated STAT3WT controls (Fig. 3A and Supplementary Fig. S6). In contrast, lymphocytes were significantly increased in the BALF of urethane-treated STAT3ΔMye mice. Neutrophils were also increased in the BALF of urethane-treated STAT3ΔMye mice, although the increase was not statistically significant.

Figure 3. Decreased lung tumorigenesis in STAT3ΔMye mice was associated with increased antitumor immunity and decreased pro-tumorigenic inflammation.

(A) Hema 3 staining showing the numbers of macrophages, lymphocytes and neutrophils in BALF from urethane-treated WT and STAT3ΔMye mice. Data shown are means ± SD (n ≥ 5; *, P < 0.05). (B) Flow cytometry analysis showing decreased MDSCs (CD11b+/Gr1+) in the lungs of urethane-treated STAT3ΔMye mice. (C) Quantification of IF staining (Supplementary Fig. S7) that shows an increase in the number of M1 (iNOS+) macrophages, but a decrease in M2 (arginase+) macrophages in the lungs of urethane-treated STAT3ΔMye mice. Data shown are means ± SD (n > 5; **, P < 0.01). (D) qPCR assay showing increased CD4+ and CD8+ expression in the lungs of urethane-treated STAT3ΔMye mice. Data shown are means ± SD (n > 5; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01). (E) Flow cytometry assay showing decreased Treg cells in the lungs of urethane-treated STAT3ΔMye mice. Only CD4+CD25+ cells were gated for further CD4 and Foxp3 analysis. (F) Flow cytometry assay showing more CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the lungs of urethane-treated STAT3ΔMye mice. (G) Flow cytometry assay showing more IFNγ+ CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the lungs of urethane-treated STAT3ΔMye mice.

We next examined the changes of MDSCs, macrophages, and T lymphocytes in the lungs of STAT3ΔMye mice treated with urethane, given their functional and/or composition complexity. MDSCs and macrophages cannot be distinguished in heme 3 staining assays described above. The tumor-promoting MDSCs (CD11b+GR1+) and M2 (arginase+) macrophages were decreased, whereas the tumor-suppressive M1 (iNOS+) macrophages and DCs were increased in the lungs of urethane-treated STAT3ΔMye mice (Fig. 3B and C, also see Supplementary Figs. S7 and S8). In agreement with the central roles of these myeloid cells in cancer immunology, we found that the tumor-promoting Treg cells (Foxp3+/CD25+ CD4+ T cells) were decreased, but the tumor-suppressive CD4+ Th1 (IFNγ+ CD4+ T cells) and CD8+ T cells were significantly increased in the lungs of urethane-treated STAT3ΔMye mice (Fig. 3, D–G). These data indicate that STAT3 functions as a major intrinsic driver of MDSCs and macrophages for their pro-tumorigenic activity in lung tumorigenesis, by inhibiting the antitumor activity and promoting the pro-tumor activity of T cells.

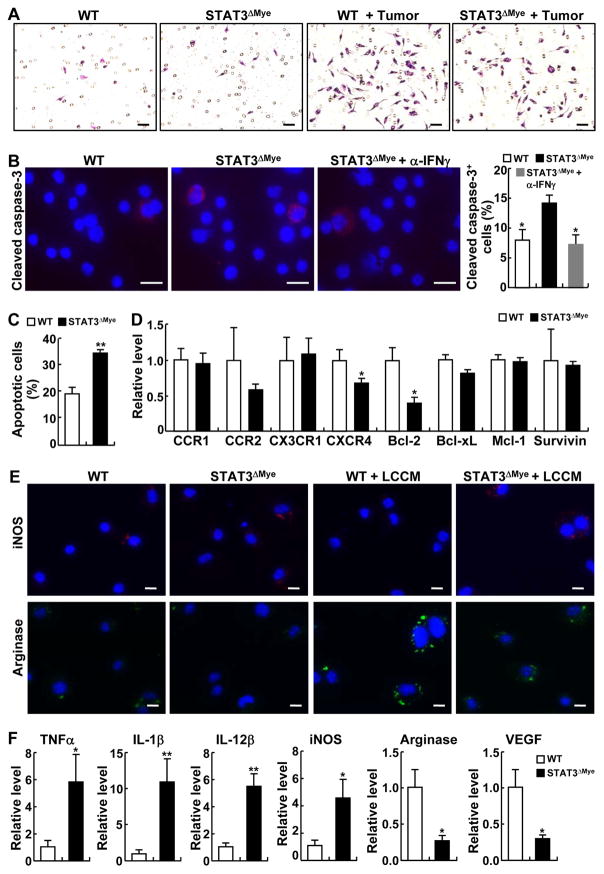

Migration and survival of MDSCs and macrophages, and M2 polarization, relies on STAT3

To investigate the mechanisms by which deletion of intrinsic STAT3 leads to an overall decrease of pulmonary macrophages and MDSCs in animals with lung tumors, we compared the migration and survival of STAT3 competent and deficient macrophages under the oncogenic stress of lung cancer. Although they showed similar migration ability in the absence of tumor cells, STAT3-deficient macrophages exhibited decreased migration toward lung tumor cells in comparison to STAT3 competent macrophages (Fig. 4A), suggesting that STAT3 is an intrinsic molecular driver for macrophages to migrate into the lungs during lung tumorigenesis.

Figure 4. STAT3 promoted pulmonary migration and survival as well as M2 polarization of macrophages in lung tumorigenesis.

(A) In vitro cell migration assays showing decreased migration of STAT3 deficient macrophages toward lung cancer cells. Scale bar: 40 μm. (B) IF staining of cleaved caspase-3 showing increased apoptosis in macrophages from urethane-treated STAT3ΔMye mice, which could be blocked by administration of IFNγ neutralizing antibodies. Representative apoptotic cells are indicated by arrows. Scale bar: 5 μm. Cleaved caspase-3-positive cells were counted and represented as the percentage of total cells. Data shown are means ± SD (n = 3; *, P < 0.05). (C) In vitro coculture and flow cytometry assays showing increased sensitivity to CD8+ T cells of STAT3 deficient CD11b+ myeloid cells. Data shown are means ± SD (n = 3; **, P < 0.01). (D) qPCR analysis showing decreased CCR2, CXCR4, Bcl-2, and Bcl-xL in pulmonary macrophages from urethane-treated STAT3ΔMye mice. Data shown are means ± SD (n = 4; *, P < 0.05). (E) In vitro assay showing the role of STAT3 in M2 polarization of macrophages induced by lung cancer condition medium (LCCM). Scale bar: 5 μm. (F) qPCR assays showing the expression changes of the indicated genes in pulmonary macrophages from urethane-treated STAT3ΔMye mice. Data shown are means ± SD (n ≥ 5; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01).

STAT3 is also required for the survival of pulmonary myeloid cells in lung cancer tumorigenesis, because pulmonary macrophages from urethane-treated STAT3ΔMye mice showed an increased apoptosis rate (Fig. 4B). The apoptosis of macrophages in urethane-treated STAT3ΔMye mice could be efficiently blocked in vivo by the administration of IFNγ-neutralizing antibodies. These data suggest that STAT3 activation renders pulmonary macrophages resistant to the apoptosis mediated by CD8+ T cells, the major producers and targets of IFNγ. To directly test this, we examined the effect of CD8+ T cell coculture on STAT3 competent and deficient myeloid cells. We found that compared to wild-type cells, STAT3-deficient myeloid cells were more sensitive to CD8+ T cells (Fig. 4C). These studies identify a novel myeloid cell-killing role for cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) in tumor suppression.

We then examined the molecular mechanisms by which STAT3 promoted pulmonary migration and survival of myeloid cells in lung tumorigenesis. We found that many chemokines attracting myeloid cells were significantly induced in the lungs of mice treated with urethane (Supplementary Fig. S9). Thus, we compared the expression of chemokine receptors CCR1, CCR2, CX3CR1, and CXCR4 in pulmonary myeloid cells from STAT3ΔMye mice and WT mice treated with urethane. We also compared the expression of the cell survival genes Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, Mcl-1 and Survivin. Among these genes, CXCR4 and Bcl-2 were significantly decreased in pulmonary myeloid cells from STAT3ΔMye mice treated with urethane (Fig. 4D). Of note, the CXCR4 ligand CXCL12 was one of the most significantly induced chemokines in lungs by urethane (Supplementary Fig. S7). The expression of CCR2 and Bcl-xL were also reduced but not the reduction was not statistically significant. These data suggest that through induction of CXCR4 and Bcl-2, and possibly also CCR2 and Bcl-xL, STAT3 enhanced migration of myeloid cells into the lungs and protected them from killing by CD8+ T cells in lung tumorigenesis.

Our previous studies suggested an important role of STAT3 in skewing macrophage polarization from M1 to M2 in lung tumorigenesis (Fig. 3D). To further clarify the in vivo findings, an in vitro assay was conducted to compare the polarization of STAT3-deficient and -competent macrophages. Lung cancer conditional medium (LCCM) induced a strong expression of arginase in STAT3 wild-type macrophages, along with a decrease in iNOS expression (Fig. 4E), suggesting an M2 polarization. However, the induction of arginase was largely lost in STAT3-deficient cells. These data suggest that STAT3 is key to transforming tumor-inhibiting M1 into tumor-promoting M2 macrophages in lung tumorigenesis. In further support of this, we found that in addition to their differential expressions in iNOS and arginase, pulmonary macrophages from urethane-treated STAT3ΔMye mice expressed more tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), interleukin-1 beta (IL1β) and interleukin-12 (IL12), but expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a key mediator of tumor angiogenesis, was decreased (Fig. 4F). These data together suggest that STAT3 drives pulmonary migration, survival, and M2 polarization of macrophages, promoting lung tumorigenesis.

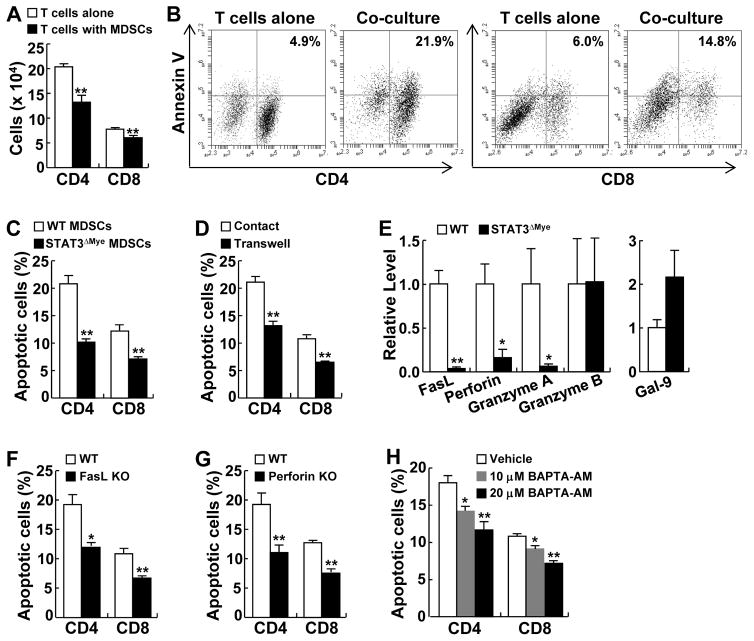

STAT3 renders MDSCs and macrophages able to directly kill CD4+ and CD8+ T cells

To investigate the molecular mechanisms by which STAT3 regulates myeloid cells to overturn CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in lung tumorigenesis induced by urethane, we examined the effect of MDSC coculture on these tumor-suppressive T cells. As expected, MDSC coculture resulted in a significant decrease in the numbers of cocultured CD4+ or CD8+ T cells (Fig. 5A). The decrease in cocultured CD4+ or CD8+ T cells was largely attributed to apoptosis caused by MDSCs, because significantly more CD4+ or CD8+ T cells could be stained by annexin V, an early marker of apoptosis, when they were cocultured with MDSCs (Fig. 5B). Moreover, the death of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells induced by MDSC coculture was dose-dependent and could be efficiently blocked by the caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK (Supplementary Fig. S10). Notably, STAT3 is the major intrinsic driver of MDSCs, because STAT3-deficient MDSCs largely lost the ability to induce apoptosis of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells (Fig. 5C). STAT3 also rendered macrophages the ability to induce CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell apoptosis, although to a lesser extent (Supplementary Fig. S11). On the other hand, both in vitro and in vivo studies indicated that myeloid STAT3 deletion had no obvious effect on T-cell proliferation and migration toward lung cancer cells (Supplementary Fig. S12). These data suggest that the increased CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the lungs of urethane-treated STAT3ΔMye mice are largely attributed to the reduced T-cell killing ability of STAT3 deficient MDSCs and macrophages.

Figure 5. STAT3 promoted MDSCs to induce cell-cell contact-dependent apoptosis of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.

(A) In vitro coculture assay showing that MDSCs significantly decreased the numbers of cocultured CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. (B) Flow cytometry analysis showing that MDSCs induced apoptosis of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in coculture. (C) In vitro coculture assay showing that STAT3-deficient MDSCs lost the ability to induce apoptosis of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. (D) In vitro coculture assay showing that MDSC-induced apoptosis of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was blocked when a transwell membrane was placed between them in coculture. (E) qPCR analysis showing decreased expression levels of FasL, perforin, and granzyme A in STAT3 deficient MDSCs. (F) In vitro coculture assay showing that FasL knockout MDSCs lost the ability to kill CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. (G) In vitro coculture assay showing that perforin knockout MDSCs lost the ability to kill CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. (H) In vitro coculture assay showing that pretreatment of MDSCs with BAPTA-AM prevented MDSC-mediated apoptosis of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in a dose-dependent manner. In A–H, data shown are means ± SD (n ≥ 3; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01).

It seems that the apoptosis of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells by myeloid cells requires a direct or close cell-cell contact, because the apoptosis of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells mediated by MDSCs was blocked when a transwell membrane was placed between them in their coculture (Fig. 5D). Based on these studies, we examined the expression of Fas ligand (FasL), perforin and galectin-9 (Gal-9), which are known to induce cell apoptosis in a cell-cell contact manner, in STAT3-competent and -deficient MDSCs. We also examined the expression of granzyme A and granzyme B, the functional partners of perforin in inducing cell death. We found that the expression of FasL, perforin, and granzyme A were significantly decreased in STAT3 deficient MDSCs in comparison to STAT3 competent MDSCs (Fig. 5E). On the other hand, granzyme B was expressed comparably and any Gal-9 increase was not statistically significant in STAT3-deficient MDSCs.

To directly test the role of FasL and perforin in MDSC-mediated apoptosis of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, we purified MDSCs from FasL or perforin knockout mice. MDSCs deficient in FasL or perforin, like those deficient in STAT3, lost the ability to kill CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Fig. 5F and G). Moreover, pretreatment of MDCSs with BAPTA-AM, an inhibitor of granular release, also prevented MDSC-mediated apoptosis of these T cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5H). These data indicate that STAT3 induced FasL, perforin and granzyme A, arming MDSCs to kill CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in a cell-cell contact manner.

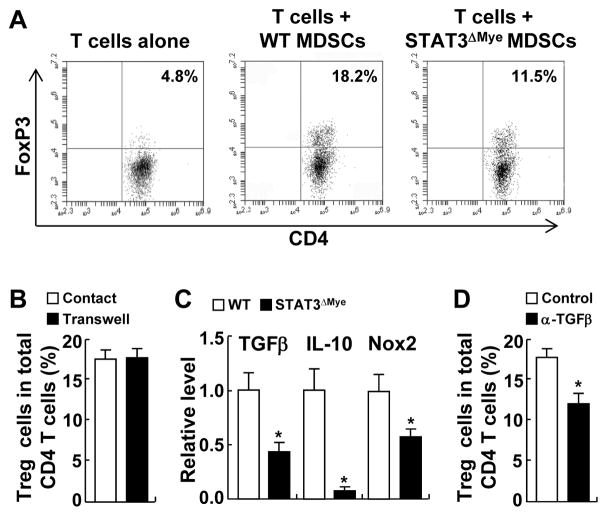

STAT3 promotes MDSC- and macrophage-induced Treg cell development

To investigate the molecular mechanisms by which tumor-promoting Treg cells were decreased in the lungs of urethane-treated STAT3ΔMye mice, we compared the abilities of STAT3-competent and -deficient MDSCs in promoting naïve T cells to differentiate into Treg cells in vitro. As expected, coculture with WT MDSCs led to increased Treg cell development (Fig. 6A). However, STAT3-deficient MDSCs lost most of this ability, suggesting that intrinsic STAT3 was required for MDSCs to promote Treg cell development. STAT3 also drove macrophages to promote Treg cell development, although to a much lesser extent (Supplementary Fig. S13).

Figure 6. STAT3 induced Treg cell development through increased MDSC expression of soluble molecules TGFβ, IL-10, and NOX2.

(A) In vitro coculture assay showing the defect of STAT3-deficient MDSCs in promoting Treg cell development. (B) Transwell coculture assay showing a cell-cell contact-independent mechanism of Treg differentiation induced by MDSCs. (C) qPCR assay showing reduced TGFβ, IL10 and NOX2 expression in STAT3 deficient MDSCs. (D) In vitro coculture assay showing blockage of MDSC-mediated Treg cell differentiation by TGFβ neutralizing antibodies. In B–D, data shown are means ± SD (n = 3; *, P < 0.05).

In contrast to inducing cell-cell contact-dependent apoptosis of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, Treg cell development by myeloid cells was largely independent of cell-cell contact, because MDSCs induced naïve T cells to differentiate into Treg cells at a comparable rate when they were seeded in separate transwell chambers (Fig. 6B). Based on this study, we examined whether the expression of TGFβ, IL10, and NOX2 were lower in STAT3 deficient MDSCs, given the roles of these secretory molecules in promoting Treg cell development. Those three genes were expressed significantly less in STAT3-deficient MDSCs compared to STAT3-competent MDSCs (Fig. 6C). To test whether STAT3 induced expression of these secretory molecules in MDSCs to promote Treg cell development, we cocultured MDSCs and naïve T cells in the presence of TGFβ neutralizing antibodies. Like deletion of STAT3 from MDSCs, addition of TGFβ neutralizing antibodies to culture medium significantly blocked MDSCs to drive Treg cell differentiation in vitro (Fig. 6D). These data suggest that STAT3 induces the key immune modulators IL10, TGFβ, and NOX2 in MDSCs to promote the development of tumor-promoting Treg cells in a cell-cell contact independent manner.

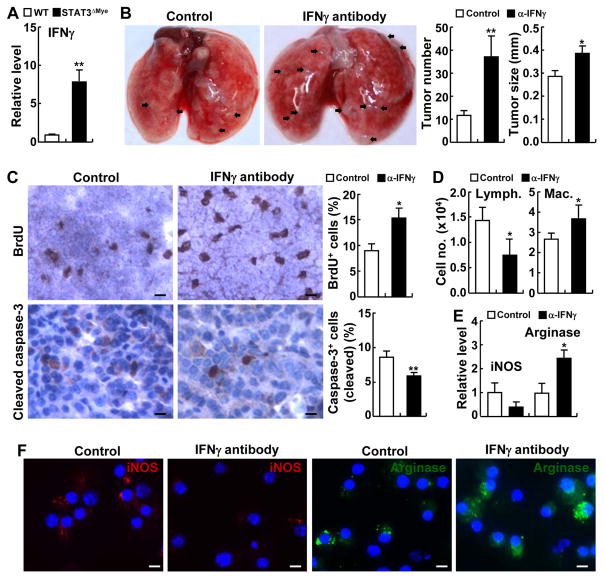

Reversal of decreased tumorigenesis in STAT3ΔMye mice by IFNγ inhibition or CD8 knockout

In line with the in vivo and in vitro studies above, we found that IFNγ, the most important antitumor Th1 cytokine that is mainly produced by CD4+ Th1 and CD8+ T cells, was significantly increased in the lungs of urethane-treated STAT3ΔMye mice (Fig. 7A). To further validate and also expand these studies, we inhibited IFNγ in STAT3ΔMye mice using a specific IFNγ-neutralizing antibody. Biological inhibition of urethane-treated STAT3ΔMye mice with anti-IFNγ induced significantly more and larger lung tumors, compared to mice treated with control antibodies (Fig. 7B). In association with increased lung tumorigenesis, suppression of IFNγ led to increased proliferation and decreased apoptosis of lung tumor cells in mice (Fig. 7C). The same phenomenon was observed when CD8 cells were selectively deleted (Supplementary Fig. S14). Thus, the indispensable and primary role of myeloid STAT3 in tumor promotion was to drive myeloid cells to suppress CTL activation.

Figure 7. Inhibition of IFNγ reversed the decreased lung tumorigenesis in STAT3ΔMye mice induced by urethane.

(A) qPCR analysis showing increased IFNγ in the lungs of urethane-treated STAT3ΔMye mice. (B) In vivo tumorigenesis assay showing increased lung tumor multiplicities and sizes in urethane-treated STAT3ΔMye mice administered with IFNγ neutralizing antibodies. (C) IHC analysis showing increased proliferation and decreased apoptosis of lung tumor cells in STAT3ΔMye mice administered with IFNγ neutralizing antibodies. BrdU-positive and cleaved caspase-3+ tumor cells were counted and represented as the percentage of total cells. Scale bar: 20 μm. (D) Hema 3 staining of BAL cells showing decreased lymphocytes and increased macrophages in urethane-treated STAT3ΔMye mice administered with IFNγ neutralizing antibody. (E) qPCR analysis showing decreased iNOS and increased arginase RNA expression in pulmonary macrophages in urethane-treated STAT3ΔMye mice administered with IFNγ neutralizing antibodies. In A–E, data shown are means ± SD (n ≥ 4; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01). (F) IF assays showing decreased iNOS and increased arginases in pulmonary macrophages in urethane-treated STAT3ΔMye mice administered with IFNγ neutralizing antibodies. Scale bar: 5 μm.

In association with the increased lung tumorigenesis, the number of pulmonary lymphocytes was decreased in STAT3ΔMye mice treated with IFNγ-neutralizing antibodies (Fig. 7D). These data were consistent with the roles of IFNγ in the expansion and activation of lymphocytes, particularly CD4+ Th1 T cells and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, for tumor killing. In contrast to the decreased lymphocytes, macrophages were significantly increased in the lungs of urethane-treated STAT3ΔMye mice administered IFNγ-neutralizing antibodies (Fig. 7D). Nevertheless, this data is consistent with our previous finding that IFNγ and its activated CD8+ T cells are important for the restriction of tumor-associated macrophages by inducing their apoptosis (Fig. 4B and C). We found that IFNγ inhibition suppressed iNOS expression and increased arginase expression of pulmonary macrophages in urethane-treated STAT3ΔMye mice at both the RNA and protein levels (Fig. 7E and F, and Supplementary Fig. S15), suggesting an important role of the Th1/CD8 immune responses in maintaining antitumor M1 phenotype and suppressing tumor-promoting M2 phenotype of macrophages for lung cancer suppression. These data further support our finding that myeloid STAT3 promoted lung tumorigenesis through turning tumor immunosurveillance to tumor-promoting inflammation.

Discussion

Breakthroughs in cancer immunotherapy are inspiring expectations for widespread successes in cancer treatment (44). However, the clinical benefit of cancer immunotherapy is still very limited. Successful development of effective cancer immunotherapy requires a much better understanding of tumor immunology. Although studies suggest myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and macrophages as major culprits transforming tumor immunosurveillance to tumor-promoting inflammation in cancer, most studies have used tumor implants and mainly focus on how MDSCs and macrophages suppress T-cell responses through paracrine mechanisms (17, 18, 25–27). Although informative, these studies require validation in endogenously arising tumors. The models used cannot represent the natural coevolution of cancer and stromal cells, and in particular immune cells. They also cannot address the role of MDSCs and macrophages in the early stages of tumor formation, nor have the intrinsic molecule(s) driving MDSCs and macrophages for their pro-tumorigenic activity been defined.

Using endogenously arising lung tumors as a model system, we have identified STAT3 as an intrinsic driver of MDSCs and macrophages for their pro-tumorigenic activity, and reveal distinct mechanisms by which STAT3 drives MDSCs and macrophages to transform tumor immunosurveillance to tumor-promoting inflammation in lung cancer. STAT3 induced expression of the key pro-apoptotic mediators FasL, perforin and granzyme A in MDSCs and macrophages, thereby arming them to kill CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in a cell-cell contact manner. STAT3 also induced expressions of IL10, TGFβ and NOX2 in MDSCs and macrophages, promoting Treg cell development and suppressing DCs in a cell-cell contact-independent manner to indirectly suppress CD4+ Th1 and CD8+ T cells.

In addition to their well-known tumoricidal activity, CD8+ T cells also kill tumor-promoting MDSCs and macrophages to indirectly suppress lung tumorigenesis, but myeloid-expressed STAT3 mediates transcription of the anti-apoptotic genes Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL, rendering MDSCs and macrophages resistant to CD8+ T cell cytotoxicity. STAT3 expression upregulated CCR2 and CXCR4, which recruited MDSCs and macrophages into the lung. STAT3 also induced arginase and VEGF, and repressed iNOS, switching the polarization of macrophages from antitumor M1 to tumor-promoting M2, enhancing lung cancer growth and angiogenesis. Deletion of STAT3 from myeloid cells in mice boosted antitumor immunity and suppressed the lung tumorigenesis induced by the tobacco carcinogen urethane. Our data also suggest a counterbalance between STAT1 and STAT3 in myeloid cells during lung tumorigenesis, given the role of IFNγ in STAT1 activation. Deletion of myeloid STAT3 led to an increase of IFNγ by T cells, which in turn activated STAT1 in myeloid cells to increase antitumor immunity through increasing expression of the tumor-suppressive cytokines TNFα, IL1β, and IL12. In line with these data, it is known that STAT1 and STAT3 generally play opposite roles in tumorigenesis (30, 45). These findings are relevant to human lung cancer, because we also found that STAT3 was activated in pulmonary myeloid cells in lung cancer patients, and that myeloid STAT3 activation correlated with pulmonary inflammation and poor survival of lung cancer patients.

Although STAT3 is oncogenically activated in lung and many other cancers, preclinical and clinical studies including those from us indicate that it is unfeasible to systemically target STAT3, or its upstream activator IL6, for lung cancer prevention and treatment, given the physiological importance as well as the complex roles of IL6/STAT3 signaling in lung cancer (15, 16, 30, 45–48, also see Supplementary Fig. S16). Since deletion of STAT3 from myeloid cells suppresses both the initiation and progression of lung cancer, targeting STAT3 specifically in myeloid cells may provide a feasible and effective approach to the use of STAT3 as a target for the prevention and treatment of lung cancer. This STAT3-based immunotherapy can also be combined with conventional chemoradiotherapies and immunotherapies, such as adoptive T-cell transfer, to treat lung cancer. Given that lung tumors are known to be highly resistant to classical chemo-, radio-, and immune-therapies, our finding showing the central role of STAT3 in the tumor-promoting functions of myeloid cells has the potential to initiate development of more efficacious approaches.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mark Jay Shlomchik for providing tissues from FasL knockout mice.

Grant Support

This study was financially supported in part by the National Institute of Health (NIH)/National Cancer Institute (NCI) grants R01 CA172090, R21 CA175252, R21 CA189703, P30 CA047904, and P50 CA090440-Lung Cancer Developmental Research Award, as well as the American Lung Association (ALA) Lung Cancer Discovery Award LCD 259111-N and American Cancer Society (ACS) Fellowship PF-12-081-01-TBG.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hecht SS. Cigarette smoking and lung cancer: chemical mechanisms and approaches to prevention. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:461–9. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(02)00815-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith CJ, Perfetti TA, King JA. Perspectives on pulmonary inflammation and lung cancer risk in cigarette smokers. Inhal Toxicol. 2006;18:667–77. doi: 10.1080/08958370600742821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Milara J, Cortijo J. Tobacco, inflammation, and respiratory tract cancer. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18:3901–38. doi: 10.2174/138161212802083743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140:883–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shiels MS, Pfeiffer RM, Hildesheim A, Engels EA, Kemp TJ, Park JH, et al. Circulating inflammation markers and prospective risk for lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1871–80. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takahashi H, Ogata H, Nishigaki R, Broide DH, Karin M. Tobacco smoke promotes lung tumorigenesis by triggering IKKβ- and JNK1-dependent inflammation. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dougan M, Li D, Neuberg D, Mihm M, Googe P, Wong KK, et al. A dual role for the immune response in a mouse model of inflammation-associated lung cancer. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2436–46. doi: 10.1172/JCI44796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiao Z, Jiang Q, Willette-Brown J, Xi S, Zhu F, Burkett S, et al. The pivotal role of IKKα in the development of spontaneous lung squamous cell carcinomas. Cancer Cell. 2013;23:527–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Melkamu T, Qian X, Upadhyaya P, O’Sullivan MG, Kassie F. Lipopolysaccharide enhances mouse lung tumorigenesis: a model for inflammation-driven lung cancer. Vet Pathol. 2013;50:895–902. doi: 10.1177/0300985813476061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Redente EF, Orlicky DJ, Bouchard RJ, Malkinson AM. Tumor signaling to the bone marrow changes the phenotype of monocytes and pulmonary macrophages during urethane-induced primary lung tumorigenesis in A/J mice. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:693–708. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zaynagetdinov R, Sherrill TP, Polosukhin VV, Han W, Ausborn JA, McLoed AG, et al. A critical role for macrophages in promotion of urethane-induced lung carcinogenesis. J Immunol. 2011;187:5703–11. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu L, Du H, Li Y, Qu P, Yan C. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3C) promotes myeloid-derived suppressor cell expansion and immune suppression during lung tumorigenesis. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:2131–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou J, Qu Z, Yan S, Sun F, Whitsett JA, Shapiro SD, et al. Differential roles of STAT3 in the initiation and growth of lung cancer. Oncogene. 2015;34:3804–14. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qu Z, Sun F, Zhou J, Li L, Shapiro SD, Xiao G. Interleukin-6 prevents the initiation but enhances the progression of lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2015;75:3209–15. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Sinha P. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells: linking inflammation and cancer. J Immunol. 2009;182:4499–506. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sica A, Larghi P, Mancino A, Rubino L, Porta C, Totaro MG, et al. Macrophage polarization in tumour progression. Semin Cancer Biol. 2008;18:349–55. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu CY, Wang YM, Wang CL, Feng PH, Ko HW, Liu YH, et al. Population alterations of L-arginase- and inducible nitric oxide synthase-expressed CD11b+/CD14−/CD15+/CD33+ myeloid-derived suppressor cells and CD8+ T lymphocytes in patients with advanced-stage non-small cell lung cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2010;136:35–45. doi: 10.1007/s00432-009-0634-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith C, Chang MY, Parker KH, Beury DW, DuHadaway JB, Flick HE, et al. IDO is a nodal pathogenic driver of lung cancer and metastasis development. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:722–35. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ortiz ML, Lu L, Ramachandran I, Gabrilovich DI. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the development of lung cancer. Cancer Immunol Res. 2014;2:50–8. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang S, Fu Y, Ma K, Liu C, Jiao X, Du W, et al. The significant increase and dynamic changes of the myeloid-derived suppressor cells percentage with chemotherapy in advanced NSCLC patients. Clin Transl Oncol. 2014;16:616–22. doi: 10.1007/s12094-013-1125-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feng PH, Lee KY, Chang YL, Chan YF, Kuo LW, Lin TY, et al. CD14(+)S100A9(+) monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells and their clinical relevance in non-small cell lung cancer. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:1025–36. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201204-0636OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang A, Zhang B, Wang B, Zhang F, Fan KX, Guo YJ. Increased CD14(+)HLA-DR (-/low) myeloid-derived suppressor cells correlate with extrathoracic metastasis and poor response to chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2013;62:1439–51. doi: 10.1007/s00262-013-1450-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Srivastava MK, Zhu L, Harris-White M, Kar UK, Huang M, Johnson MF, et al. Myeloid suppressor cell depletion augments antitumor activity in lung cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40677. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Srivastava MK, Dubinett S, Sharma S. Targeting MDSCs enhance therapeutic vaccination responses against lung cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2012;1:1650–1. doi: 10.4161/onci.21970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sawant A, Schafer CC, Jin TH, Zmijewski J, Tse HM, Roth J, et al. Enhancement of antitumor immunity in lung cancer by targeting myeloid-derived suppressor cell pathways. Cancer Res. 2013;73:6609–20. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pei BX, Sun BS, Zhang ZF, Wang AL, Ren P. Interstitial tumor-associated macrophages combined with tumor-derived colony-stimulating factor-1 and interleukin-6, a novel prognostic biomarker in non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;148:1208–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun J, Mao Y, Zhang YQ, Guo YD, Mu CY, Fu FQ, et al. Clinical significance of the induction of macrophage differentiation by the costimulatory molecule B7-H3 in human non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Lett. 2013;6:1253–60. doi: 10.3892/ol.2013.1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 30.Yu H, Pardoll D, Jove R. STATs in cancer inflammation and immunity: a leading role for STAT3. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:798–809. doi: 10.1038/nrc2734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun F, Xiao G, Qu Z. Murine bronchoalveolar lavage. Bio-protocol. 2017 doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.2287. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun F, Qu Z, Xiao Y, Zhou J, Burns TF, Stabile LP, et al. NF-κB1 p105 suppresses lung tumorigenesis through the Tpl2 kinase but independently of its NF-κB function. Oncogene. 2016;35:2299–310. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun F, Xiao Y, Qu Z. Oncovirus Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus (KSHV) represses tumor suppressor PDLIM2 to persistently activate nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) and STAT3 transcription factors for tumorigenesis and tumor maintenance. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:7362–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C115.637918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qu Z, Yan P, Fu J, Jiang J, Grusby MJ, Smithgall TE, et al. DNA methylation-dependent repression of PDZ-LIM domain-containing protein 2 in colon cancer and its role as a potential therapeutic target. Cancer Res. 2010;70:1766–72. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fu J, Qu Z, Yan P, Ishikawa C, Aqeilan RI, Rabson AB, et al. The tumor suppressor gene WWOX links the canonical and noncanonical NF-κB pathways in HTLV-I Tax-mediated tumorigenesis. Blood. 2011;117:1652–61. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-303073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qu Z, Fu J, Ma H, Zhou J, Jin M, Mapara MY, et al. PDLIM2 restricts Th1 and Th17 differentiation and prevents autoimmune disease. Cell Biosci. 2012;2:23. doi: 10.1186/2045-3701-2-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qing G, Qu Z, Xiao G. Proteasome-mediated endoproteolytic processing of the NF-κB2 precursor at the κB promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:5324–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609914104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yan P, Fu J, Qu Z, Li S, Tanaka T, Grusby MJ, et al. PDLIM2 suppresses human T-cell leukemia virus type I Tax-mediated tumorigenesis by targeting Tax into the nuclear matrix for proteasomal degradation. Blood. 2009;113:4370–80. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-185660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qu Z, Fu J, Yan P, Hu J, Cheng SY, Xiao G. Epigenetic repression of PDZ-LIM domain-containing protein 2: implications for the biology and treatment of breast cancer. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:11786–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.086561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Young PP, Ardestani S, Li B. Myeloid cells in cancer progression: unique subtypes and their roles in tumor growth, vascularity, and host immune suppression. Cancer Microenviron. 2010;4:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s12307-010-0045-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang W, Pal SK, Liu X, Yang C, Allahabadi S, Bhanji S, et al. Myeloid clusters are associated with a pro-metastatic environment and poor prognosis in smoking-related early stage non-small cell lung cancer. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clausen BE, Burkhardt C, Reith W, Renkawitz R, Förster I. Conditional gene targeting in macrophages and granulocytes using LysMcre mice. Transgenic Research. 1999;8:265–77. doi: 10.1023/a:1008942828960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abram CL, Roberge GL, Hu Y, Lowell CA. Comparative analysis of the efficiency and specificity of myeloid-Cre deleting strains using ROSA-EYFP reporter mice. J Immunol Methods. 2014;408:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2014.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Couzin-Frankel J. Breakthrough of the year 2013. Cancer immunotherapy. Science. 2013;342:1432–3. doi: 10.1126/science.342.6165.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Avalle L, Pensa S, Regis G, Novelli F, Poli V. STAT1 and STAT3 in tumorigenesis: A matter of balance. JAKSTAT. 2012;1:65–72. doi: 10.4161/jkst.20045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen M, Sun F, Han L, Qu Z. Kaposi’s sarcoma herpesvirus (KSHV) microRNA K12-1 functions as an oncogene by activating NF-κB/IL-6/STAT3 signaling. Oncotarget. 2016;7:33363–73. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bayliss TJ, Smith JT, Schuster M, Dragnev KH, Rigas JR. A humanized antiIL-6 antibody (ALD518) in non-small cell lung cancer. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2011;11:1663–8. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2011.627850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Angevin E, Tabernero J, Elez E, Cohen SJ, Bahleda R, van Laethem JL, et al. A phase I/II, multiple-dose, dose-escalation study of siltuximab, an anti-interleukin-6 monoclonal antibody, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:2192–204. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.